- Science news

- Health

- VIDEO: Scientist’s work plays leading role in redefining our understanding of the brain’s systems

VIDEO: Scientist’s work plays leading role in redefining our understanding of the brain’s systems

By Ben Stockton

With a wish to not appear immodest, Professor Pierre Magistretti tentatively indicates two moments that have shaped his career. The first came with the surprise that lactate, more typically associated with insufficient blood supply to muscle, was being produced by the support cells of the brain, known as glia or astrocytes, and used as an energy source for neurons. “Neurons can send messages to glial cells and tell them, “please get us some energy,”” and this arrives in the form of lactate, explains Magistretti.

It recently became apparent that lactate had further implications in the brain. Magistretti and his peers are now “fully engaged in understanding how this lactate is not only an energy substrate but also a signal for plasticity and memory,” which has become a cornerstone of his current work.

Magistretti, a Professor at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia and at the Brain Mind Institute at EPFL in Lausanne, could be excused for immodesty. His contribution to the field of brain energy metabolism have seen him awarded with the IPSEN Neuronal Plasticity prize and he currently presides over the International Brain Research Organization. Amongst this, he lends his expertise as Specialty Chief Editor to the Neuroenergetics, Nutrition and Brain Health section hosted in Frontiers in Neuroscience and Frontiers in Nutrition.

Redefining our understanding of the brain’s systems

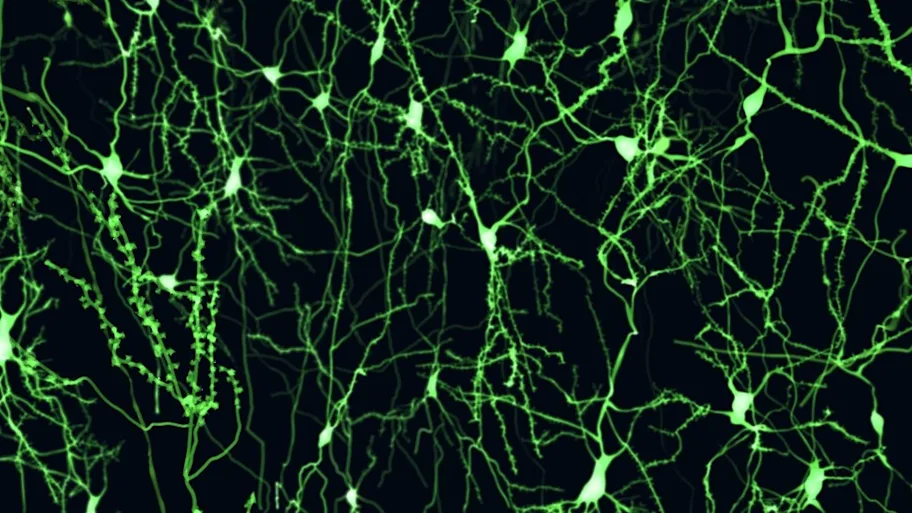

Glial cells have long been considered as a supporting cast for the neuronal cells. Beginning with Ramon y Cajal’s intricate illustrations over 100 years ago, neurons have commanded center stage. But Magristretti’s work has played a leading role in redefining our understanding of the brain’s systems. He explains that glia was called so “because it was thought to be “glue” just keeping neurons together but suddenly seemed that actually this “glue” was responding to a neuronal signal”.

These once silent cells became the focus of intense interest within a matter of years. As is always the case with studying the brain, things became even more complex than previously thought. The exact ratio of glia to neurons is disputed and varies between brain regions but, in essence, the number of cells of interest increased immeasurably. The brain was once described as “the cathedral of complexity”. Magistretti unearthed the crypt. “There is a lot to be done,” he considers, “that’s why I think it is exciting”.

By studying the full spectrum of the brain’s processes – from the molecular and the genetic to the physiological and the behavioral – his lab has begun to chip away at the mystery that first shrouded this phenomenon, coined the Astrocyte-Neuron Lactate Shuttle. The receptors modulated by lactate in the brain have been identified and a number of genes implicated. Further still, it has been “clearly demonstrated that if we interfere with the exchange of lactate from astrocytes to neurons, we can block long-term memory.” Remarkably, not allowing the exchange can also prevent addictions and dependence to cocaine. “It becomes now suddenly a tool we can use to modulate behaviors.”

Ambitious but rewarding goal for the future

Originally a medical doctor by training, Magistretti has retained the desire to ease illness. He hopes, to use this findings of a 35-year research career to “address the issues in particular of neuroprotection to prevent neurodegeneration and to maintain cognitive function by acting this neural-glia metabolic coupling.”

Effective treatments for nearly all neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, remain elusive. “We are actually exploring molecules that can somehow boost [neural-glia metabolic coupling] with the idea that possibly these molecules could be useful for neuroprotection in the context of neurodegenerative disease,” he said.

He admits it is an ambitious goal, and a lot of people are trying to do the same, but he does hope his research could help find treatments for these diseases in the future.