- Science News

- Open science and peer review

- Article Processing Charges: Open Access could save global research

Article Processing Charges: Open Access could save global research

The total number of peer-reviewed research articles published each year increases by approximately 4% [Scopus]. In 2014, nearly 400,000 published research articles were Gold open-access papers. This results in approximately 20% of all research articles — and the number is growing at an astonishing rate of 20% per year (Lewis, 2013). If the rate continues, open-access papers will exceed subscription papers in just a few years from now.

This, and similar observations, have led some commentators to predict that traditional subscription journals will soon be a thing of the past (Lewis, 2012). But is this a credible prediction? Is open access capable of disrupting the entire scholarly publishing industry? Can it replace traditional publishing or force it to adopt new business models?

The answers depend on whether open access satisfies two fundamental criteria for disruption: an increase in efficiency and a decrease in costs.

The new generation of open-access publishers are “born digital” which is undoubtedly far more efficient, but how much will universities, institutes and scientists save by switching to open access ?

Brief history of the evolution of open access

From the 1950s to the 1990s, nearly all scientific papers were published in subscription journals that were paid for by individual readers or their libraries. The open access movement challenged this model, arguing that scientific knowledge is a public good which should be made freely available to anyone, anywhere in the world. By the early 1990s, the World Wide Web made it possible for researchers to publish scientific papers online. This eliminated printing and paper costs, and made distribution instantaneous, unlimited and virtually free. The new movement profited from the opportunities offered by the new technology.

An early pioneer was Paul Ginsparg’s ArXiv, a public repository. ArXiv was originally designed for particle physicists, and allowed scientists to make their “preprints” freely accessible to the entire scientific community. It now hosts more than a million papers from many different disciplines (Ginsparg, 1994; Ginsparg, 2011). In the early 2000s, the movement accelerated as commercial publishers began producing a rapidly increasing range of peer reviewed open-access journals primarily in the life sciences. BMC was founded in 1998 and was followed by PLOS, which published its first journal in 2003. Frontiers published its first paper in 2008.

More open-access publishers were to follow, and many traditional publishers also launched their own Gold open-access journals. These were a hybrid model that allowed authors in subscription journals to pay a fee to make their articles open access. As the movement increased in popularity, numerous funding agencies and governments created mandates obliging publicly funded researchers to make their papers publicly available. Many universities created repositories supporting these policies, and traditional journals adapted their copyright policies to the new reality.

New open-access business model shifts traditional publishing costs

The competition between open access and traditional scholarly publishing is a competition between different business models. Despite a shift towards the so-called hybrid model and the launch of Gold open-access journals, traditional publishers continue to generate most of their revenues from subscriptions. Meanwhile, the fastest growing open-access publishers rely on Article Processing Fees (APCs), which they charge authors or their universities (if the university pays the fees). Traditional publishers are being increasingly pushed by funding agencies who are mandating them to adopt Gold open access publishing models. Will they be able to compete on this basis? This depends on their costs and on the future levels of APCs.

On the cost side, there is no doubt open-access publishers have far lower costs than traditional publishers. To start off, they have no costs for printing and paper distribution. And as new, relatively small companies, they tend to have leaner management and fewer overhead costs. But this doesn’t mean that open access is free.

Open-access journals need editors and editorial support staff. Plus, managing a complex peer-review system takes time, effort and expert resources. Above all, open-access publishers rely on computing. They need complex software to manage submissions and peer reviews, and they require large, stable storage to accommodate the growing number of articles they publish. They also require reliable services to support their rapidly expanding user base.

Most importantly, innovation needs to be continuous if they are to be sustainable. The Frontiers platform, for example, offers its user base author and editor profiles, article level metrics, author impact metrics, integrated social media metrics and the tools that drive the Frontiers tiering system. None of these services could have been developed using off-the-shelf software.

It was the need to develop our own services that made Frontiers the first open-access publisher to develop its own publishing platform. This has allowed us to continuously add new capabilities as we have grown and meet the needs of researchers. Other open-access publishers such as PeerJ and PLOS are following suit.

Premium services becoming a guide for APCs

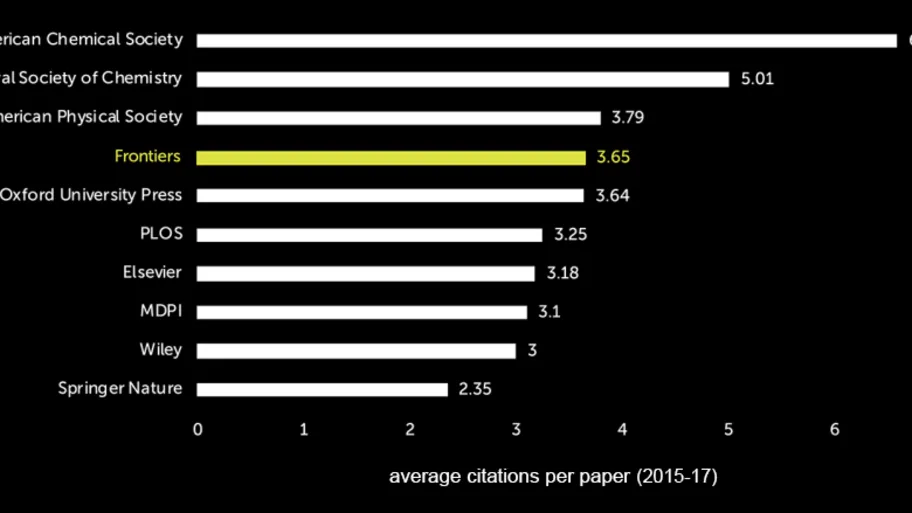

Developing, maintaining and expanding the necessary software and hardware is expensive. Open-access publishers build these costs into their APCs. But of course, the price publishers charge authors should depend on the value of the service provided. One way (not the ideal way) to measure value is by considering the average number of citations that could be obtained by publishing in a specific journal. If we look at APCs for open access and hybrid journals with different impact factors, we begin to see how APCs could link to a journal’s value.

In Figure 1, journals with impact factors of 6 or higher generally charge higher APCs than journals with lower impact factors. However, APCs for journals with impact factors above 6 mostly fall in the same range, which is somewhere between $2000 and $4000. The maximum is around $5000. The average of the sample below is around $2,7001, the plateau is reached with an APC of $3,200.

Figure 1: APC vs IF (for sources, see below and to see complete data, click here).

Traditional publishers’ high costs are reflected in the high prices they charge to subscribers. In 2014, they charged approximately $7000 for every article they published, and many of these articles were published in journals with low impact factors. The estimate is based on $14 billion2 revenue for the 2 million papers published in 2014 (Scopus).

In the coming years, APCs for high quality open-access journals may peak at around $3,200, with an average around $2,000. This is approximately half or even one third of the fees libraries are currently paying for subscription journals. Global research could therefore save $7-10 billion a year by switching to open access. Indeed, independent reports predict that a large conversion to open access will shrink the market by 57% (Outsell, 2009).

The big question for open access will be how to judge the service provided. We anticipate that developing Journal Level Metrics focused on the real value delivered to submitting authors will be an important guide for the evolution of APCs. We also believe authors will want full transparency of what they are paying for.

Basic open-access services provided by most OA publishers listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals:

Submit-review-reject/accept: Submission and peer-review

Author retention of copyright: The CC-BY license to respect author rights

On-line display: Free to read and download

Permanent storage: Redundancy systems for robustness

Archiving: Independent storage, additional storage guarantee, distributed reader access

Advanced open-access services, such as those provided by Frontiers:

Digital editorial offices: Editorial independence, efficiency

Collaborative reviews: Fairness, constructive, interactive, efficient, custom-made online IT platform

Author & editor profiles: Transparency, visibility, dissemination, impact

Editor names published: Acknowledgement, accountability, transparency

Comments/blogs: Post-publication discussion

Article level metrics: For real-time article impact assessment

Author level metrics: For real-time aggregated impact assessment

Journal level metrics: For transparent value of services provided

Press releases and social media exposure: Public visibility

Media impact metrics: For monitoring public visibility

Loop network: Dissemination and finding of articles

Discovery: Personalized dynamically computed reading lists

Tiering: Spotlighting the best articles judged democratically

eBooks: Convenient packaging and dissemination of Research Topics

Honoraria: Acknowledging the work of editors without introducing conflicts-of-interest

Awards: Acknowledge participation, performance

Waivers: Remove blocks to Open Access publishing

Subsidies: For new fields and fields that do not have the budgets for APCs

All of these services can be provided to researchers at a fraction of the cost of the subscription model, which demonstrates that open access does meet the fundamental criteria for disruptive change in scholarly publishing. Open access increases efficiency and decreases costs.

FOOTNOTES:

The real average is unknown but could be lower.

This figure is obtained by combining The STM Report(T_he STM Report: An overview of scientific and scholarly journal publishing,_ 2015) and SIMBA Report(Global Social Science and Humanities Publishing 2013 – 2014, 2013).

REFERENCES:

Archambault, E., D. Amyot, P. Deschamps, A. Nicol, F. Provencher, R. Rebout and G. Roberge (2014). Proportion of open access papers published in peer-reviewed journals at the european and world levels 1996–2013. Science-Metrix-European Commission.

Christensen, C. (2013). The innovator’s dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail, Harvard Business Review Press.

Christensen, C. M. (2006). The ongoing process of building a theory of disruption. Journal of Product innovation management 23 (1): 39-55.

Ginsparg, P. (1994). First steps Towards electronic research communication. Computers in Physics 8 (4): 390-396. doi: 10.1063/1.4823313.

Ginsparg, P. (2011). ArXiv at 20: The price for success – CornellCast. Retrieved February 13, 2015, from http://www.cornell.edu/video/arxiv-at-20-the-price-for-success.

Lewis, D. W. (2012). The inevitability of open access., Update One,, Indiana University

Lewis, D. W. (2012). The inevitability of open access. College & Research Libraries 73 (5): 493-506.

Outsell, Open Access Primer – Market Size and Trends, 2009

Sources for APC (by publisher):

Elsevier: http://cdn.elsevier.com/promis_misc/j.custom97.pdf

Hindawi: http://www.hindawi.com/apc/

NPG: http://www.nature.com/openresearch/publishing-with-npg/nature-journals/

OUP: http://www.oxfordjournals.org/en/oxford-open/index.html

Sage: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/pure-gold-open-access-journals-at-sage

Elsevier hybrid: https://www.elsevier.com/about/open-science/open-access/open-access-journals

Springer hybrid: http://www.springer.com/gp/librarians/journal-price-list