- Science news

- Life sciences

- A travel through Biochemistry and beyond: from textbooks to Mount Everest

A travel through Biochemistry and beyond: from textbooks to Mount Everest

An interview with Michele Samaja, Associate Professor in Biochemistry at the University of Milan and Guest Associate Editor for Frontiers in Pediatrics.

Before falling in love with Biochemistry, Professor Michele Samaja was about to leave the university after only one year. “After the classical courses in Chemistry, Physics, Organic Chemistry, Microbiology etc., I was rather discouraged by the tedious and repetitive teachings and textbooks,” he said, “I even started practicing as a TV-cameraman and as a downhill ski instructor.”

Then, he finally incurred the right course. Needless to say, it was a course of Biochemistry. “Eventually I became increasingly stimulated in getting more and more insight in what appeared to me a young discipline with high impact in every biomedical branch.”

Today Michele Samaja is an Associate Professor in Biochemistry at the University of Milan, and this discipline led him to interact with different kinds of scientists (from physiologists to hematologists, pathologists, pharmacologists and immunologists), with lots of young PhD students and even with Sherpas from Nepal.

What’s the main focus of your current research?

The “genetic” imprinting that is leading my past and current research was given by a unique opportunity I had just after graduating, when I participated to a small scientific expedition to the Himalayas to study how local dwellers can perform extraordinarily despite the severe oxygen lack.

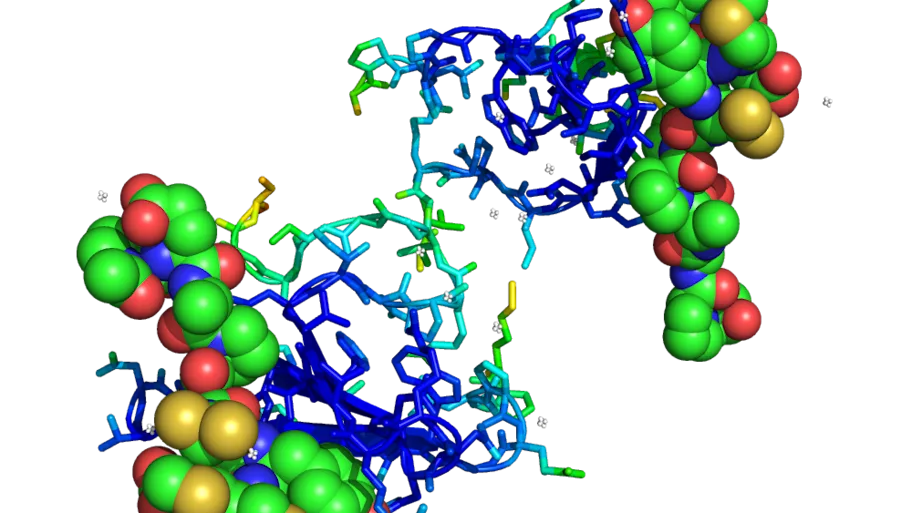

Along with a series of unforgettable experiences gathered with the rural and poor, yet extremely fierce and proud population residing in the upper valleys of Nepal, this marked my life and research activity afterwards. My current research interests include three broad groups of studies, performed within a small but fierce group of young researchers and long-lasting collaborations in Italy and abroad, that are all related in some way to that experience. First, we are investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying hypoxia in brain, heart, tumours and liver. Although easy, I refrain adopting cultured cells because they do represent the complexity of human body and its responses to stress. Second, we are studying cardiac biology with concern to various drugs and non-drug intervention as exercise, intermittent hypoxia and hyperoxia. This study is based on the role of the reoxygenation for which our editorial in Frontiers in Pediatrics has just appeared. Finally, we are developing substances able to carry oxygen in blood, a must in view of times when blood for transfusion will become an expensive resource with little availability.

Over the years you have participated to a number of Medical Research Expeditions to Mount Everest: can you tell us a little more about that and what motivated you to join this project?

That first adventure was followed by other large research and climbing expeditions, especially but not only in the Everest region. The climax was the 1994 Italian-French expedition during which we set up a laboratory camp at 6450 m above sea level along the route to Mount Everest.

With the help of top-class climbers and two young Italian doctors who were specifically trained for this task, we performed the first and so far only arterial blood gas analysis in a sizeable population accompanied by other measurements aimed at understanding the mechanisms of the blood oxygen transport at extreme altitude. That was really a remarkable goal that required a complex exceptional organization and extreme skill to perform measurements that until now have not yet been replicated even by much more expensive and larger expeditions.

But most of all the scientific expeditions to the Himalayas represented a great chance to realize how the skills gained in the laboratory to handle basic biochemical procedures could be used in wider contexts and for nobler purposes.

The enormous difficulties of any type encountered in this work, from a scientific, psychological and logistic point of view, have never been equalized in any other subsequent work, and I smile when young (and not so young) people tell me of the “great” difficulties encountered in their research activity. I remember a climb along the difficult and dangerous Everest Icefall while monitoring the progression of the heroic Sherpa porters who were carrying delicate loads with scientific equipment across incredible crevasses in precarious equilibrium on thin ladders and under the menace of big avalanches. A really unforgettable day!

You have degree in biology, you work together with medical doctors and, on the top of everything else, you are a traveler. What is your common theme?

I always do my best for being able to discuss not only biochemical issues, but also issues related to Physiology, Pharmacology, Hematology, Pathology and many others, not to mention matters related to R&D politics.

As I think that multidisciplinarity is a key for the future, I often recommend my students and post-docs not limit their interests within a specific field, but to have the humility and the force to travel beyond it.

For this reason, traveling the world is an integral part of my job: by seeing and understanding other worlds, other ways of life, other cultures one learns how to handle integrated approaches to Science and Life.

There is a big difference between active traveling and passive touring, or between discussing a Science issue and listening passively. A monk who lived high in the Nepalese mountains used to say: “Many people came here seeing, no good. Few people came here looking, good!” Well, I can’t agree more with that teaching, which encompasses traveling and Science.

Finally, since part of your job is also supervising PhD students, what do you feel to suggest to young people who have decided or are deciding to invest their lives in research?

Choose a supervisor who can teach you Science by stimulating your reasoning (Mr.Poirot would say your grey cells) rather than feeding a series of notions or rules to be memorized. Choose a supervisor who can teach you what is beyond Science using as less words as possible: words often, perhaps always, do not help. Take with you your supervisor’s teaching, thank him/her and build your career on what, and not whom, you know. And have fun!

Aida Paniccia, PhDJournal Operations SpecialistFrontiers in Pediatricspediatrics.editorial.office@frontiersin.org