- 1South African Medical Research Council Centre for Tuberculosis Research, Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

- 2Section of Veterinary Bacteriology, Institute for Food Safety and Hygiene, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse, Zürich, Switzerland

- 3Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) including Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis), which primarily affects animal hosts; however, it is also capable of causing zoonotic infections in humans. Direct contact with infected animals or their products is the primary mode of transmission. However, recent research suggests that M. bovis can be shed into the environment, potentially playing an under-recognized role in the pathogen’ spread. Further investigation into indirect transmission of M. bovis, employing a One Health approach, is necessary to evaluate its epidemiological significance. However, current methods are not optimized for identifying M. bovis in complex environmental samples. Nevertheless, in a recent study, a combination of molecular techniques, including next-generation sequencing (NGS), was able to detect M. bovis DNA in the environment to investigate epidemiological questions. The aim of this study was, therefore, to apply a combination of culture-independent methods, such as targeted NGS (tNGS), to detect pathogenic mycobacteria, including M. bovis, in water sources located in a rural area of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa. This area was selected based on the high burden of MTBC in human and animal populations. Water samples from 63 sites were screened for MTBC DNA by extracting DNA and performing hsp65 PCR amplification, followed by Sanger amplicon sequencing (SAS). Sequences were compared to the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database for genus or species-level identification. Samples confirmed to contain mycobacterial DNA underwent multiple PCRs (hsp65, rpoB, and MAC hsp65) and sequencing with Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) tNGS. The ONT tNGS consensus sequences were compared to a curated in-house database to identify mycobacteria to genus, species, or species complex (e.g., MTBC) level for each sample site. Additional screening for MTBC DNA was performed using the GeneXpert® MTB/RIF Ultra (GXU) qPCR assay. Based on GXU, hsp65 SAS, and ONT tNGS results, MTBC DNA was present in 12 of the 63 sites. The presence of M. bovis DNA was confirmed at 4 of the 12 sites using downstream polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods. However, further studies are required to determine if environmental M. bovis is viable. These results support further investigation into the role that shared water sources may play in TB epidemiology.

1 Introduction

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) includes M. tuberculosis (MTB) and Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis), which primarily infect human and animal hosts, respectively (1). In addition, MTB can spread from humans to both domestic and wild animals, resulting in reverse zoonosis (2, 3). Similarly, M. bovis can lead to zoonotic tuberculosis (ZTB) infections, whih account for an estimated 12% of human TB cases globally (4). In African countries and among pastoralist communities where unpasteurized milk is consumed, the rate of ZTB can be higher, up to 37.7% of cases (5).

The spread of M. bovis occurs primarily by prolonged close contact with infected hosts through aerosols (6). However, shed bacilli may persist in environmental material for 1–3 months (7) and contribute to indirect transmission (8). Indirect transmission of M. bovis between animal hosts through shared food sources has been demonstrated experimentally (9). Furthermore, the presence of M. bovis in invertebrates, soil, and shared water sources near infected host populations suggests that environmental transmission may occur (8, 10–12). Evaluating epidemiological links for TB between people, animals, and their shared environment requires a One Health approach (13). However, detecting M. bovis in the environment poses a challenge due to the complexity and paucibacillary nature of the samples. In addition, the survival of M. bovis is influenced by variable environmental conditions (14, 15).

Other mycobacterial species also play a vital role in human and animal health. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTMs) are ubiquitous in the environment but can lead to opportunistic infections in humans and animals (2). Infections caused by NTMs have been increasingly reported, especially in immunocompromised individuals (16–18). Members of the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) are common NTMs that have been implicated in human and animal diseases. For example, the MAC subspecies paratuberculosis causes Johne’s disease in livestock and has been associated with Crohn’s disease in humans (19, 20). Furthermore, exposure of human and animal populations to NTMs can result in cross-reactive immune sensitization, which may impact MTBC vaccine responses and the accuracy of diagnostic tests (21, 22).

Infections caused by different mycobacterial species (e.g., MTBC or NTMs) or ecotypes (e.g., MTB or M. bovis) may differ in pathogenicity, host species immune responses, and antibiotic resistance, requiring different diagnostic and management approaches. Therefore, the correct identification of mycobacterial species and ecotype is, crucial for favorable treatment outcomes (23, 24). Antemortem detection of MTBC infection currently depends on cytokine release assays, tuberculin skin tests, thoracic radiographs, and screening with the GeneXpert® MTB/RIF Ultra (GXU Cepheid, CA, USA) quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay (25, 26). However, these techniques cannot differentiate between infections caused by different MTBC ecotypes or strains (27, 28). Additionally, co-infections caused by NTMs may result in cross-reactive immunological responses, which can confound TB diagnostic test interpretation, especially in areas with high human and animal TB, as well as environmental NTM, burdens (29, 30). Therefore, culture and characterization of mycobacterial isolates remain the gold standard for detecting MTBC despite limitations such as the paucibacillary nature of antemortem samples, lengthy incubation times, and biosafety concerns associated with handling viable mycobacteria (31, 32).

Advances in molecular techniques, such as quantitative PCRs (qPCR) and PCR amplicon-targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS), have improved the sensitivity of mycobacterial detection in complex samples (12, 33). In contrast to qPCR, amplicon tNGS is highly scalable and more suitable for characterizing multiple gene targets in a complex microbiome (34). Specific gene targets for genus-level detection of mycobacteria include DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta (rpoB) and a heat shock protein of 65-kDa (hsp65) (35, 36). The variation within these gene targets can be used for species-level identification. Moreover, sequencing additional gene targets can be used to differentiate MAC and MTBC ecotypes, including MAC hsp65 and gyrase (gyrA, gyrB1, and gyrB2) gene regions, respectively (37, 38). Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT, Oxford, UK) NGS has increased the resolution of phylogenetic comparisons of M. bovis isolates (33, 39) to elucidate epidemiological links in much the same way that spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping) have been used for cultured isolates historically (40).

Previous studies have detected NTMs and MTBC in human and animal populations at livestock-wildlife-human interfaces in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (41–44). There is a high burden of MTB in humans and M. bovis in animals in this area and spillovers into the environment could occur and play an under-recognized role in MTBC epidemiology. Therefore, this study aimed to determine if M. bovis DNA was present in shared water sources in a rural area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. This is the first step in evaluating if M. bovis or MTB are being shed into this environment, using culture-independent methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Location and sample collection

The study areas included rural communities that span two municipalities within the Umkhanyakude District, KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. Shared water sources, with observed animal and human usage, were sampled in the Mtubatuba municipality (n = 14) and Big Five Hlabisa municipality (n = 49). These included areas surrounding local schools, residences, community areas, medical facilities, and farming areas (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). The Mtubatuba municipality communities border the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park (HiP), which contains African buffalo (Syncerus caffe) populations that are endemically infected with M. bovis (45). Rural communities in these areas practice communal grazing, where M. bovis-infected cattle (Bos taurus) and goats (Capra hircus) have been identified (41, 46). One to eight environmental samples were collected from each site into 50 mL conical bottom centrifuge tubes (Abdos Life Sciences, Roorkee, Uttarakhand, India). These samples were collected from the water’s edge in a single scooping motion that included a mixture of sediment and water. Water sources were not filtered or treated with any wastewater treatment prior to sample collection. All samples were boiled at 98°C for 45 min, as required for transport of samples to Stellenbosch University, where they were stored at 4°C prior to downstream molecular testing.

2.2 Detection and characterization of mycobacterial DNA

2.2.1 DNA extraction

Prior to DNA extraction, a 10 mL aliquot from each sample was centrifuged at 3,200 rcf for 10 min in an Eppendorf 5810R (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) to concentrate any microorganisms present in the sample. The supernatant was decanted, and 0.25 g of the pellet was used for DNA extraction with the Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Cell lysis was performed for 20 min using a Vortex-Genie 2 (Scientific Industries, Bohemia, NY, USA) and a 12-tube adapter (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany). A final volume of 60 μL of genomic DNA was eluted per sample and stored at −20°C. The quantity (ng/μL) of extracted DNA was determined for 20 randomly selected samples using the Qubit DNA Broad Range Assay Kit and the Qubit™4 Fluorometer (both ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Moreover, the integrity of the extracted DNA was evaluated by electrophoresis using a 1% agarose gel. Gel imaging was conducted using the BioRad Chemi Doc Universal Hood III and Gel Documentation System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and the BioRad Image Lab 6.1 Software.

2.2.2 PCR amplification

A universal bacterial 16S PCR assay was used to assess if DNA samples could be amplified and to confirm the absence of PCR inhibitors (47). Briefly, each PCR reaction consisted of 9.5 μL of nuclease-free water, 12.5 μL OneTaq Hot start 2× master mix with standard buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 0.5 μL forward primer, 0.5 μL reverse primer, and 2 μL of DNA template, in a total volume of 25 μL. Primers were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, IO, USA) and comprise a working stock concentration of 10 μL. Cycling conditions consisted of 1 cycle at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 65°C for 30 s, elongation at 68°C for 90 s, and a final elongation step of 5 min at 72°C, using an Applied Biosystems Veriti 96-well Fast Thermal Cycler (ThermoFisher Scientific Waltham, MA, USA). Gel electrophoresis was conducted to confirm that amplicons were the expected sizes. If DNA could be amplified using the 16S PCR assay, PCR was repeated with primers targeting additional gene targets (hsp65, rpoB, MAC hsp65, and gyrase) with optimized cycling conditions (Table 1). All PCRs conducted in this study included a positive control (M. bovis DNA) and a non-template control (nuclease-free water). If DNA could not be amplified with 16S PCR, it was not used in downstream molecular testing.

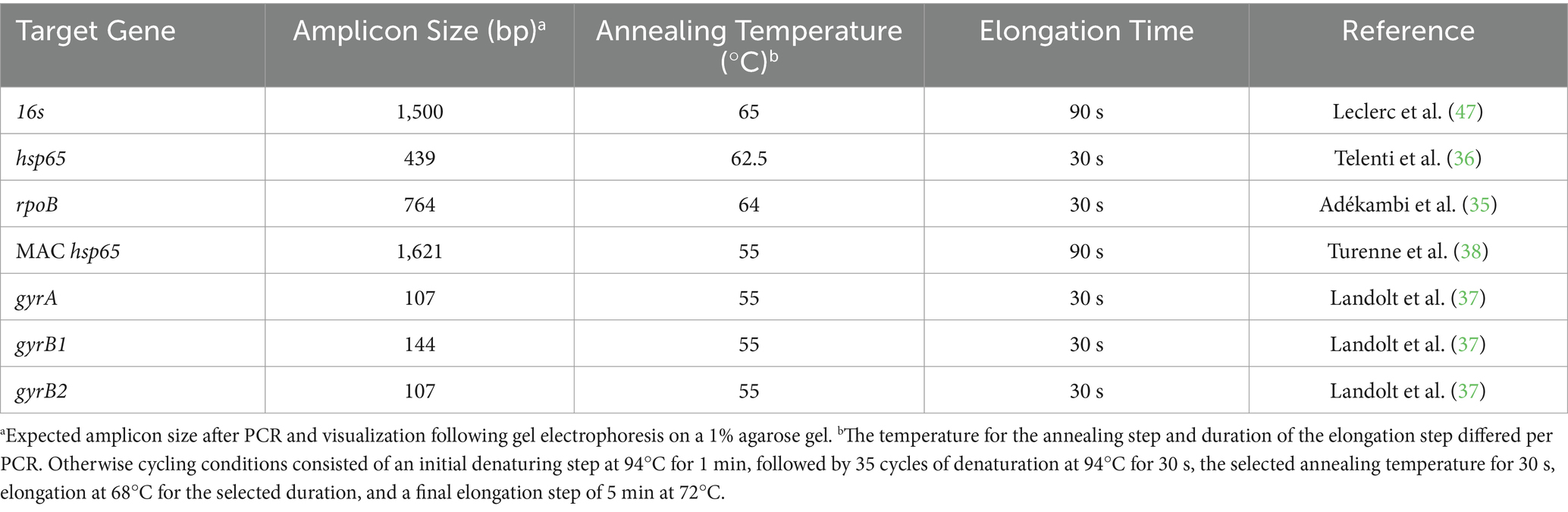

Table 1. Published polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for mycobacterial gene amplification of DNA extracted from water samples (Umkhanyakude District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) with the target gene, amplicon size, and cycling conditions indicated.

2.2.3 Sanger amplicon sequencing (SAS)

Sanger amplicon sequencing (SAS) was used to screen samples for mycobacterial DNA (36, 48) using Mycobacterium genus-specific hsp65 amplicons, according to Clarke et al. (49), to provide an affordable prescreening option (48). The hsp65 PCR was briefly performed using the optimized annealing temperature and elongation times (Table 1). Amplicons were sent for post-PCR clean-up and Sanger sequencing at the Stellenbosch University Central Analytical Facility (CAF, Stellenbosch, South Africa). Sanger sequences were aligned, and consensus sequences were produced using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (version 7.7, Tom Hall, CA, USA). Consensus sequences were compared to the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool for Nucleotides (BLASTn) program (50).1 The percentage coverage (PC) and identity match (PIM) between Sanger sequences and the NCBI database were recorded. A PC and PIM ≥ 80% with an hsp65 sequence from a known mycobacterial genome was required for genus-level identification. If no sequences met these criteria, the DNA sample was not used for downstream analysis. If the sequence also matched a known mycobacterial species, including non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTMs) or MTBC with PIM ≥ 90%, identification was reported at the species level. If sequences from a DNA sample matched MTBC at the species level, the sample was considered positive for MTBC. Since MTBC ecotypes or strains cannot be distinguished based on their hsp65 amplicon sequences, samples with MTBC DNA were further characterized as described in Section 2.3.2.

2.2.4 Oxford Nanopore Technologies targeted next-generation sequencing (ONT tNGS)

To confirm the presence of mycobacterial species detected by hsp65 SAS and further characterize the mycobacteriome, additional amplicons (hsp65, rpoB, MAC hsp65, and gyrase PCRs) from selected samples were sequenced using ONT tNGS. Amplicons were pooled for each sample in equal molar concentrations (200 fmol), then end-repaired and individually barcoded (39). Briefly, the pooled PCR amplicons (hsp65, rpoB, MAC hsp65, gyrB1, and gyrB2) from each sample received the same barcode using the Native Barcoding Kit v14 (ONT), Blunt/TA Ligase Master Mix, Next Ultra II End Repair/dA Module, and Quick Ligation Module (all from New England Biolabs). Unique barcode numbers 17–73 were used for samples, while barcode 74 was added to a no-DNA control. Due to the similar lengths of target sequences, gyrA amplicons were barcoded separately from the other amplicons (barcoded Nos. 19, 21, and 39) using independent barcodes (Nos. 75, 76, and 77). Barcoded amplicons from all samples were pooled into a single library, native adapters ligated, loaded onto a single R10.4.1 flow cell (>1,250 pores), and sequenced using the MinION mk1C device (ONT). The barcodes’ base-calling, demultiplexing, and trimming were performed using Guppy version 6.4.6, with the high-accuracy option selected (51). Quality control and filtering reads with a Q score of <12 were performed using nanoq version 0.10.0 (52), FastQC version 0.11.9, and pycoQC version 2.5.0.23 (53). Reference-free read sorting was performed using the amplicon sorter tool version 2023-06-19 (54). A total of 200,000 randomly chosen reads with lengths between 50–2000 bp were selected for each barcode. Consensus sequences were grouped based on amplicon size and similarity, and relative abundancies (PRA) ≥ 1% retrieved, based on the representative pool of reads analyzed. ABRicate2 was applied to screen consensus sequences against customized databases for each target and generate summary report files, according to Ghielmetti et al. (39). The distribution of consensus sequences generated per target gene was visualized using the R package ggplot2 (55). Consensus sequences with PC and PIM < 90% (based on comparison to sequences from the in-house database) were annotated as unclassified. Consensus sequences with PC and PIM ≥ 90%, compared to the sequences from known mycobacterial genomes, were classified to genus level. Consensus sequences with PC ≥ 90% and PIM between 97–99% compared to sequences from a known mycobacterial species were manually inspected using BLASTn (NCBI) before the mycobacterial species with the highest identity match was assigned. However, consensus sequences with PC ≥ 90% and PIM ≥ 99% were assigned as NTMs or MTBC without manual inspection. If the mycobacterial species in a sample was identified as MTBC, the sample was considered positive for MTBC, and DNA was used for downstream characterization according to Section 2.3.2. If no species could be assigned, identification remained at the genus level.

2.3 Detection and characterization of MTBC DNA

2.3.1 Detecting MTBC with the GeneXpert® MTB/RIF ultra (GXU) qPCR assay

The GeneXpert® MTB/RIF Ultra (GXU) qPCR assay was selected as an independent method to screen environmental samples for the presence of MTBC DNA, despite being optimized primarily for human sputum samples (56). As previously described, one 10 mL aliquot was used per sample for GXU (57). Each aliquot was centrifuged at 1,000 rcf for 5 min in an Eppendorf 5810R centrifuge to pellet large sediment particles. Notably, 1 mL of supernatant was collected at the interface above the sediment pellet and transferred to a 5 mL tube, after which an equal volume of GXU sample reagent (1 mL) was added. Supernatant samples were vortexed for 10 s before and after a 10 min incubation at room temperature (20–22°C), loaded into a GXU cartridge (Cepheid), placed in the GeneXpert® IV instrument (Cepheid), and analyzed according to manufacturer’s guidelines. The GXU test outputs indicated semiquantitative MTBC DNA levels. In this study, the GXU was repeated if samples returned INVALID/ERROR. The MTB NOT DETECTED output was reported as a negative result (i.e., neither IS6110 nor IS1081 amplified). The levels of MTB detected (very low/low/medium/high) were based on preprogrammed rpoB cycle threshold (CT) values: very low (Ct > 28), low (Ct 22–28), medium (Ct 16–22) or high (Ct < 16). If MTB was not detected with rpoB probes but with IS6110 and IS1081, rifampicin resistance could not be established, and the GXU output was MTB TRACE DETECTED. In this study, MTB TRACE readouts were considered an MTBC positive result since the assay cannot distinguish between MTBC ecotypes or strains. If MTBC DNA was detected, the sample was considered positive for MTBC, and DNA was extracted and used for downstream characterization according to Section 2.3.2. If no MTBC was detected, the sample was not further investigated.

2.3.2 Characterization of MTBC

If GXU, hsp65 SAS, or ONT tNGS detected MTBC DNA, the site was considered positive, and MTBC DNA was further evaluated to determine which MTBC ecotype (Mycobacterium africanum, M. bovis, M. bovis BCG, Mycobacterium canettii, Mycobacterium caprae, Mycobacterium microti, and M. tuberculosis) was present using three PCR-based methods. First, after ONT tNGS (Section 2.2.4), gyrase (gyrA, gyrB1, and gyrB2) consensus sequences were compared to the in-house database containing gyrase gene regions from known MTBC ecotypes. If the MTBC-specific SNPs, described by Landolt et al. (37), were present and there was a match (PC and PIM ≥ 99%) with the ecotype M. bovis, the sample was considered positive for M. bovis DNA. Second, the genomic regions of difference (RD) PCR were used to characterize MTBC, according to Warren et al. (58). Briefly, PCR was used to amplify RD1, RD4, RD9, and RD12 gene regions, and amplicon presence or absence was visualized using gel electrophoresis. If the presence or absence of RD amplicons was consistent with that of M. bovis, M. bovis DNA was considered detected in that sample. Finally, spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping), performed according to Kamerbeek et al. (59), was used to identify MTBC ecotypes and strains. Briefly, spacer sequences within the direct repeat (DR) gene region were amplified using biotinylated primers and hybridized to synthetic oligonucleotides of known spacer sequences on a membrane. The spacers were visualized on X-ray film and the pattern translated into an octal code. If the spoligotyping pattern/code matched that of a known MTBC ecotype, such as M. bovis, M. bovis DNA was considered detected. Multiple spoligotyping patterns/codes may be identified as M. bovis but differ slightly, they can be used to differentiate M. bovis strains if pattern resolution is sufficient. Positive control (M. bovis) DNA and a non-template control were included for all three methods. The detection of M. bovis with any of the three methods (gyrase ONT tNGS, RD-PCR, and spoligotyping) resulted in the sample being considered positive for M. bovis. Additionally, analyses of the gyrB sequences and RD1 amplicon presence facilitated the differentiation of M. bovis from M. bovis BCG (58, 60). If the MTBC ecotype could not be identified, the sample was considered to contain uncharacterized MTBC DNA.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The detection of MTBC DNA using hsp65 SAS or ONT tNGS was evaluated compared to the GXU, which is widely used for MTBC detection and is an independent PCR method (61). The percentage observed agreement (po) was calculated for all 63 sites with INVALID/ERROR GXU results considered as negative for MTBC. The chance agreement (pe) was calculated based on column and row sums with the equation (proportion of Test A that is positive for MTBC × proportion of Test B that is positive for MTBC) + (proportion of Test A that is negative for MTBC × proportion of Test B that is negative for MTBC). The equation K = (po – pe)/(1 – pe) was then used to calculate Cohen’s kappa statistic (62, 87). The 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated in GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). A scale used by Landis and Koch (63) was used for interpretation agreement as absent (values ≤0), slight (0.01–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), or near perfect (0.81–1.00). Cohen’s kappa statistics were also used to evaluate the detection of M. bovis DNA using ONT tNGS or RD-PCR compared to spoligotyping according to the above methodology.

After MTBC DNA was detected with GXU, SAS, and ONT tNGS, the PRA or CT values of samples that tested positive with all three methods were compared with samples that tested positive based on one or two methods. To this end, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Excel version 16 and the XLSTAT add-in (Microsoft Office, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used.

3 Results

3.1 DNA extraction, PCR, and sanger amplicon sequencing (SAS)

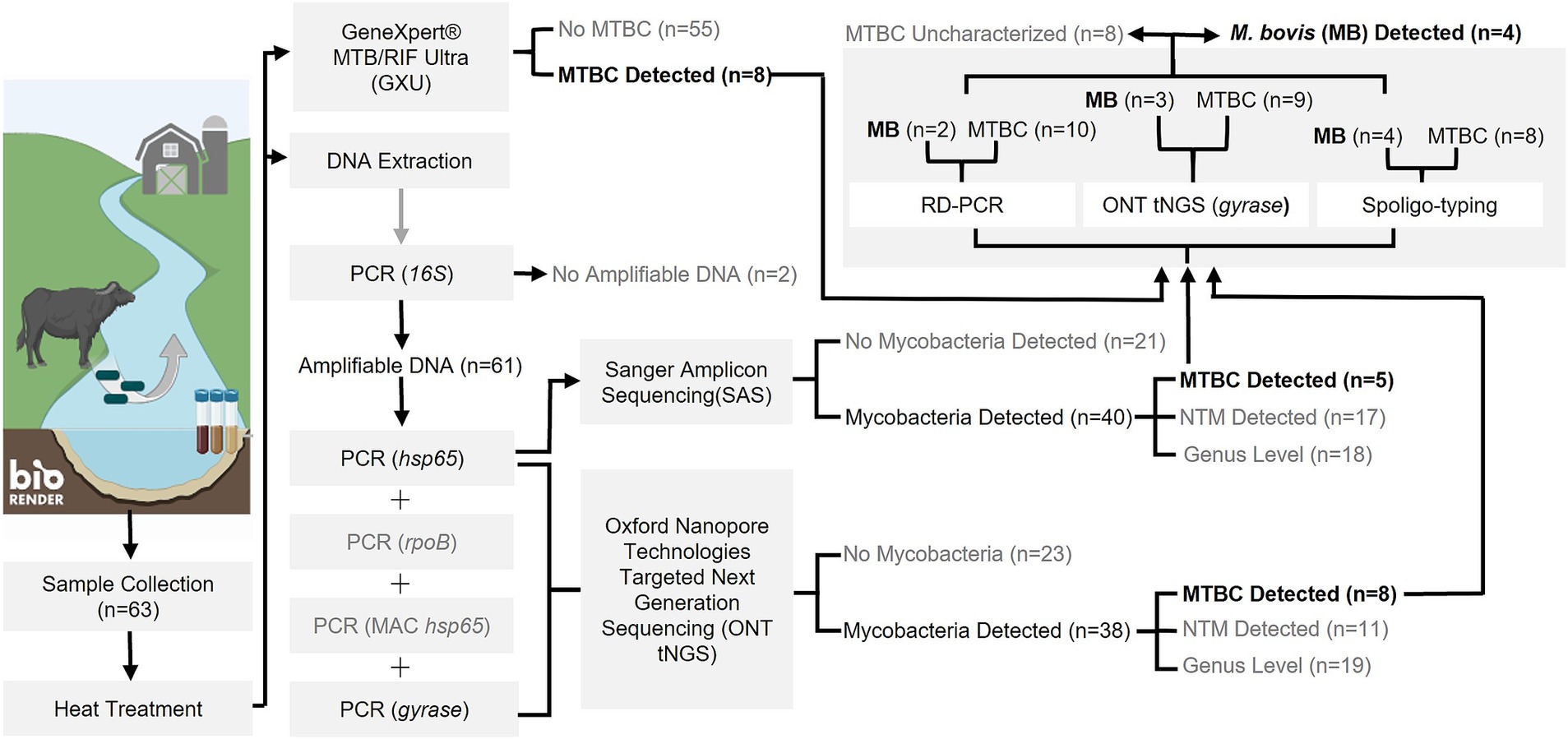

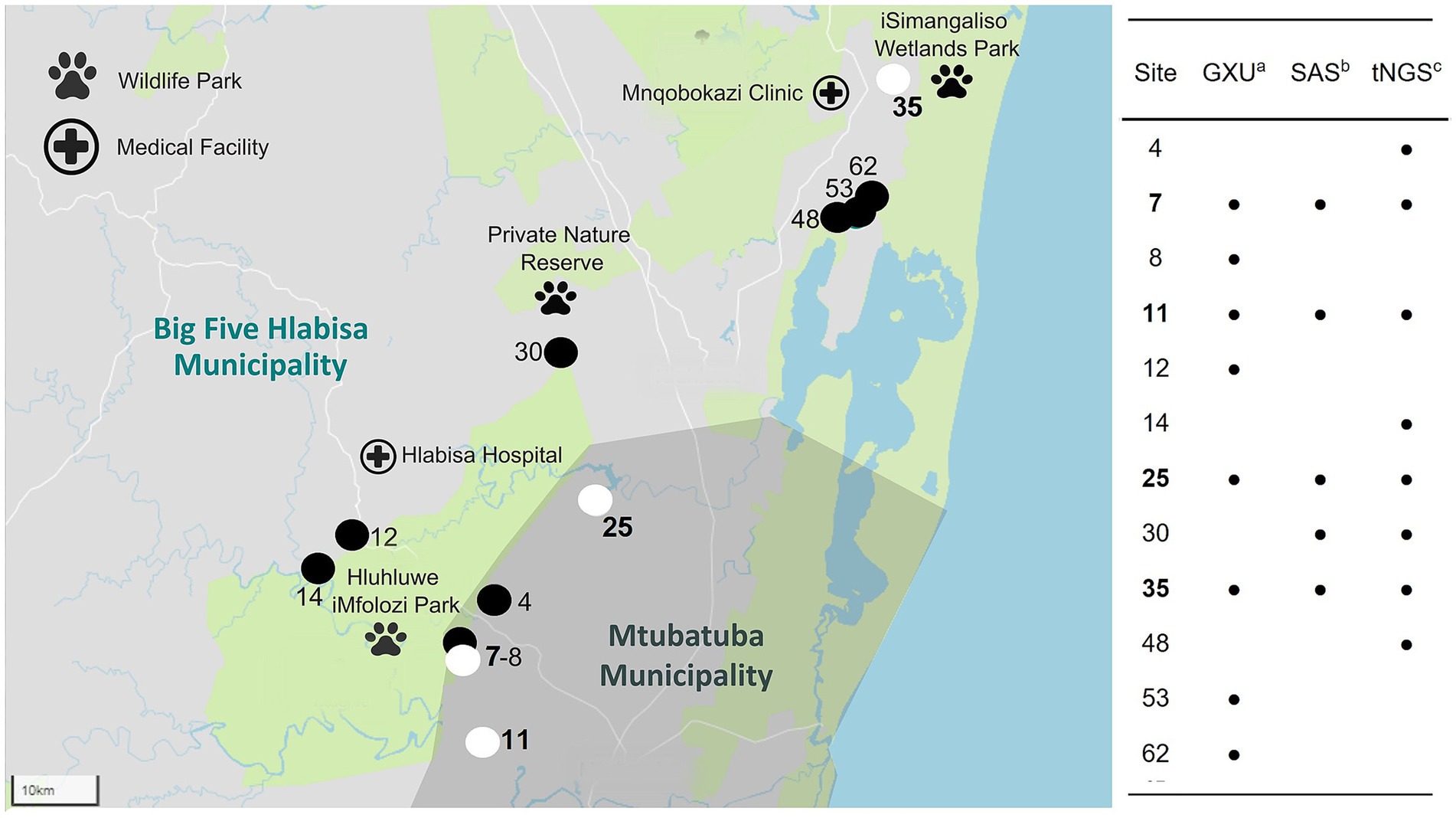

Sample DNA was extracted from 63 sites and screened for mycobacterial species, including MTBC. According to Qubit results, an average of 576 ng/μL (SD: 221 ng/μL) of DNA was extracted. Intact DNA was observed using gel electrophoresis. Although multiple samples were taken from some sites, the results were summarized per site to aid interpretation (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S1). The DNA from all 63 sites, except two (sites 2 and 53), could be amplified with 16S PCR and, therefore, did not contain PCR inhibitors. The Mycobacterium genus-specific PCR (hsp65) and SAS detected the presence of mycobacteria in samples from 40 sites. Of these, mycobacterial DNA could be identified at the mycobacterial complex or species level for 23 sites. Samples from 5 of these sites (7, 11, 25, 30, and 35) had detectable MTBC DNA (Figure 2; Table 2), while 10 sites had sequences matching MAC DNA. In addition, a variety of other NTM species were identified, including Mycobacterium canariasense/cosmeticum, Mycobacterium crocinum, Mycobacterium madagascariense, Mycobacterium novocastrense, Mycobacterium parmense, Mycobacterium saskatchewanense, Mycobacterium parafortuitum, Mycobacterium paraense, Mycobacterium vaccae, and Mycobacterium nebraskense.

Figure 1. Flowchart outlining study methods and outcomes for PCR-based detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) DNA and characterization as M. bovis from water sources in the Umkhanyakude District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of sample sites tested and results at each step. Steps which did not result in MTBC detection or warrant further downstream analysis are indicated in grey text. Created in BioRender. Matthews, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/t74p898.

Figure 2. Map of 12 water sample sites (out of 63) where Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) DNA was detected, including 4 sites identified to contain Mycobacterium bovis (site number highlighted in bold) DNA within the Umkhanyakude District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Detection was based on results from GeneXpert® MTB/RIF Ultra (GXU)a, qPCR assay, Sanger amplicon sequencing (SAS)b of hsp65 PCR amplicons, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS)c of hsp65 and gyrase PCR amplicons. Sites with MTBC DNA detected by any method are shown with the site number and a black location pin on the map. If MTBC DNA could be characterized as M. bovis, the site was marked with a white location pin on the map.

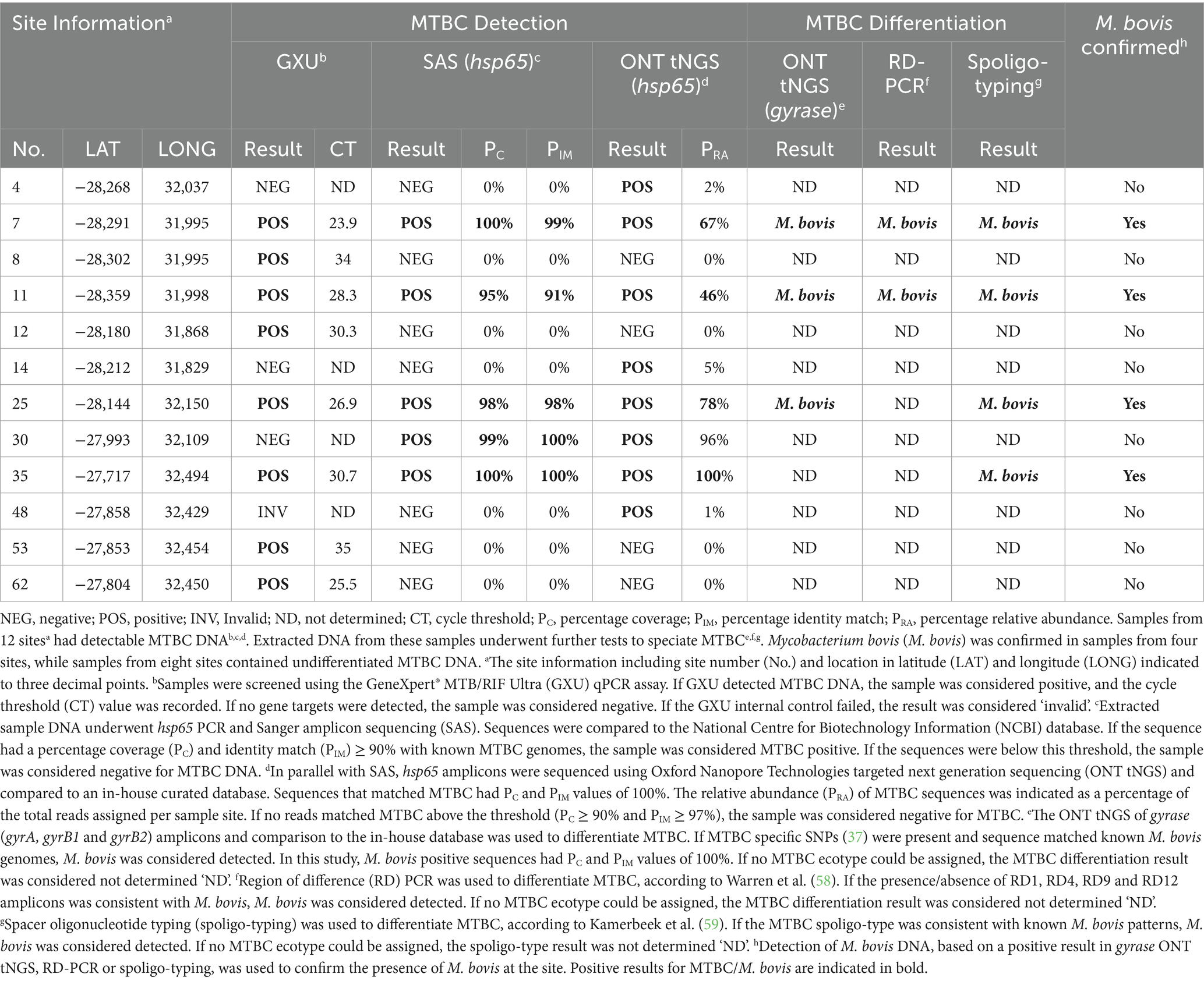

Table 2. Multiple PCR-based methods were used to detect and differentiate Mycobacterial tuberculosis complex (MTBC) DNA extracted from water sources in Umkhanyakude District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

3.2 Oxford nanopore targeted next-generation sequencing (ONT tNGS)

Since environmental samples were expected to have a complex mycobacteriome, multiple mycobacterial PCR amplicons (hsp65, rpoB, MAC hsp65, and gyrase) underwent ONT tNGS to evaluate the PRA and diversity of the mycobacterial species present. Barcoded samples had an average of 202,544 reads (SD: 85,003) and an average read quality score of 16 (SD: 0.39). The ONT tNGS of the hsp65 gene target indicated the presence of mycobacterial DNA at 38 sites, including NTMs (MAC, M. crocinum, M. canariasense/cosmeticum, M. madagascariense, M. novocastrense, M. parmense, and M. saskatchewanense) at 11 sites, and MTBC in samples from 8 sites (Nos. 4, 7, 11, 14, 25, 30, 35, and 48). The PRA of MTBC DNA ranged from 1 to 100% (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). All five MTBC-positive sites identified by screening with hsp65 PCR and SAS (Nos. 7, 11, 25, 30, and 35) were confirmed by ONT tNGS (Figure 2; Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, ONT tNGS of the rpoB gene target detected mycobacterial DNA at genus level at 30 sites, NTMs to species level at four sites (Nos. 22, 34, 48, and 52), but no MTBC DNA. After ONT tNGS, MAC hsp65 consensus sequences could not be classified to the species level using a ≥ 90% PIM threshold and were not differentiated further. Based on these results for rpoB and MAC hsp65 ONT tNGS, they were excluded from Supplementary Table S1.

3.3 Detecting MTBC DNA with the GXU, SAS, or ONT tNGS

As an independent rapid screening method for MTBC DNA detection in this pilot study, the GXU was performed on a separate sample aliquot from the 63 sites (Figure 1; Supplementary Table S1). Samples from four sites (Nos. 34, 39, 48, and 51) had INVALID/ERROR results, even after GXU was repeated. Of the remaining samples tested, the majority had no detectable MTB. However, eight sample sites (Nos. 7, 8, 11, 12, 25, 35, 53, and 62) had an MTB TRACE detected result, which was considered positive for MTBC in this study. The CT value for positive samples ranged between 23.9 to 35 (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). A comparison of MTBC DNA detection results between GXU, hsp65 SAS, and ONT tNGS is shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. There was moderate agreement between GXU and SAS (kappa statistic of 0.57) or ONT tNGS results (kappa statistic of 0.43), respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The DNA from four sites (Nos. 7, 11, 25, and 35) tested positive using all three methods and showed higher median PRA (72.5%) and lower CT values (27.6) compared to samples that were positive in only one or two tests. The differences were, however, not significant (p > 0.05).

3.4 Characterization of MTBC

To further speciate MTBC DNA detected at 12 sites (Nos. 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 25, 30, 35, 48, 53, and 62) based on GXU, hsp65 SAS or ONT tNGS, three PCR-based methods were used in parallel (Figures 1, 2; Table 2). At four sites (Nos. 7, 11, 25, and 35), M. bovis DNA was confirmed to be present based on spoligotyping. Although the spoligotyping pattern was consistent with M. bovis, the blot was too faint to assign a strain or spoligotype specific code conclusively. Using RD-PCR and gyrase ONT tNGS, M. bovis was detected at two (Nos. 7 and 11) and three (Nos. 7, 11, and 25) sites, respectively. Moreover, there was moderate (kappa statistic 0.57) and substantial (kappa statistic 0.80) agreement between spoligotyping and RD-PCR and ONT tNGS results, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). Overall, M. bovis DNA was confirmed in 4 sites (Nos. 7, 11, 25, and 35) with one or more PCR based methods, while MTBC DNA was considered detected but could not be characterized further at the remaining eight sites (Nos. 4, 8, 12, 14, 30, 48, 53, and 62).

4 Discussion

In this study, GXU, hsp65 SAS, and ONT tNGS were combined to enhance culture-independent detection of MTBC DNA from water sources in KZN. Further differentiation of MTBC was based on RD-PCR, spoligotyping, and gyrase ONT tNGS. Environmental samples from 12 sites at livestock-wildlife-human interfaces were found to contain MTBC DNA, with four sites confirmed to contain M. bovis DNA, in selected areas with high burdens of human and animal TB (43). Although eight samples with MTBC could not be identified at the ecotype level, it is possible these sites were contaminated by either M. bovis or M. tuberculosis since both animals and human rural communities used the locations. The presence of either MTBC ecotype is essential for understanding the potential role of the environment in TB epidemiology (13).

The detection of M. bovis/MTBC DNA in environmental samples is an arduous process but has been successful in the United Kingdom, France, and Portugal (11, 33, 64). Although a previous attempt to find environmental M. bovis in South Africa was unsuccessful (65), advances in molecular tools improved this study’s detection feasibility. The presence of M. bovis DNA in shared water sources in KZN suggests that the source of contamination could be infected local livestock or wildlife and, less likely, human populations. This is not surprising since epidemiological links have been shown between environmental M. bovis and infected local animal populations in a previous study (33). Moreover, the porous boundaries of HiP facilitate interactions at livestock-wildlife-human interfaces, leading to potential spillover between the park and local communities (43, 46). In addition, sharing untreated water sources by people and animals could result in MTBC contamination and increased infection risk. Increased MTBC surveillance in humans, animals, and the environment would provide a more comprehensive approach and is especially important due to the presence of other human diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (43, 66). However, managing MTBC environmental contamination would entail enforcing disease management and sanitation practices that limit risk. For example, maintaining barriers between wildlife and domestic animals, bactericidal water treatments, and timely disposal of animal excrement and carcasses (8, 67, 68, 88). Therefore, further investigations are needed to understand the complex TB epidemiology in these systems and inform health interventions (13, 42) to minimize risk.

In this study, MTBC DNA was detected more frequently with GXU or ONT tNGS than with SAS. However, the GXU and ONT tNGS results were discordant at 50% of sites. According to Verma et al. (69), GXU detected environmental MTBC at “trace” levels, which is beyond the limit of detection of the rpoB probes but not IS6110/1081 probes. This complicates interpretation and means positive GXU results confirmed by ONT tNGS are likely more reliable (70). Similarly, discordant GXU negative results could be due to platform-specific limitations when using complex samples, including PCR inhibition. For example, sample site 30 was GXU negative, although strong sequencing signals were observed with SAS and ONT tNGS. This highlights the potential for false negative GXU results and the importance of using a multi-modal approach. As with GXU, the detection of MTBC DNA varied across (hsp65, rpoB, and gyrase) gene targets when evaluating ONT tNGS results. As shown in previous research, variation in the hsp65 gene region appeared more informative than rpoB for species or complex-level detection of mycobacteria (71). Furthermore, MTBC detection based on the hsp65 sequences only correlated with detection and characterization based on gyrase sequences in 25% of sites. The differences in gene target performance could be explained by sample composition, amplicon size, and nucleotide content, which affect PCR and tNGS efficiency (72). Future assay validation should, therefore, determine sensitivity per gene target using a dilution series of target DNA within different sample matrices. Due to the variations in performance between gene targets and sequencing methods, multiple molecular assays should be used in parallel rather than as a simple screening hierarchy for reliable environmental MTBC surveillance.

As NTMs are ubiquitous in the environment (73), it was unsurprising that hsp65 SAS and ONT tNGS identified several NTMs. Unlike SAS, ONT tNGS could provide PRA estimates and detect NTM with or without MTBC. Of the NTMs detected, MAC, M. madagascariense, and M. nebraskense have previously been reported in water and soil samples from KZN (74), as well as from livestock, wildlife, and people in this province (41, 44, 74). Unfortunately, differentiation based on MAC hsp65 was impossible due to low sequence quality and poor homology with known MAC sequences in the database. Other gene targets, such as IS900 and IS901, should be investigated for differentiating MAC strains in the future studies (19, 75). Of the NTMs detected, some were not previously reported in KZN. These findings provide useful information for comparison with future human clinical or veterinary mycobacterial isolates from these communities. Although this study identified NTMs and MTBC, incorporating a mycobacterial mock community (76) in the future studies would facilitate a more standardized comparison between mycobacteriome projects across different environments.

Although M. bovis detection could be confirmed by RD-PCR, spoligotyping, or gyrase ONT tNGS, these methods could not differentiate the MTBC ecotype in 8 of the 12 positive samples. Therefore, it was impossible to determine if contamination was due to MTB or M. bovis. In addition, the M. bovis spoligotyping could not be assigned, which could have provided an epidemiological link with infected animal populations in the area (39, 43). In samples where MTBC was detected, but the ecotype could not be assigned, it was likely that DNA from M. bovis or other MTBC was present but at levels too low for differentiation (77). Therefore, different approaches, such as magnetic bead capture techniques, should be explored to enrich MTBC in samples pre- or post-DNA extraction (33, 78). Moreover, if the methods by Pereira et al. (33) were used, the diversity of M. bovis strains based on SNP diversity (33) rather than spoligotyping could be explored. The complex nature and heterogeneity of mycobacterial species present in environmental samples could also have led to challenges in attributing a single MTBC ecotype using the techniques employed in this study, due to the 99.9% genetic similarity of members in this group (79).

A limitation of this study was that although the PRA of MTBC ONT tNGS hsp65 sequences and GXU CT values provided a crude estimate of MTBC concentrations per sample, the effect of environmental conditions and animal density could not be explored due to the limited sampling time (4 days), resources and data availability. According to a study by Courtenay et al. (64), the quantity of M. bovis DNA alone in soil may provide some insights into the infection status of animal populations, as shown in a study of local badgers and proximal cattle farms. In contrast, a study by Martínez-Guijosa et al. (80) found detection of environmental M. bovis DNA was not correlated with host animal prevalence or disease. Still, it was associated with certain environmental conditions. These variables should be explored in the future studies, especially as research has predominantly focused on environmental NTMs, or MTBC in general (13, 81, 82).

A significant limitation of this study was the requirement (from the South African Department of Agriculture) to heat-inactivate samples before transport, which precluded mycobacterial culture. This would have provided additional confirmation of viable mycobacteria present and potentially increased detection of MTBC since the expected paucibacillary nature of these samples may have been below the limits of detection (15). However, despite heat treatment, high quantities of amplifiable DNA could be extracted, amplified, and sequenced. Moreover, in this study, ONT tNGS was moderately and substantially comparable to more traditional molecular assays for MTBC and M. bovis detection. The amplicon-targeted approach was chosen as it was more sensitive for culture-independent detection of specific environmental microorganisms compared to shotgun sequencing (83, 84). The disadvantage is that using PCR for target enrichment prior to tNGS, may introduce bias, producing results not reflective of the original mycobacteriome (85). Additional culture-independent techniques that should be explored in the future studies to quantify viable M. bovis preferentially could include fluorescent labeling and sorting of MTBC cells with flow cytometry (86).

Despite the limitations of this study, M. bovis and MTBC DNA were successfully detected in environmental samples collected from a high TB burden area within KZN, South Africa, suggesting possible contamination by infected animal and or human populations. Environmental sources of MTBC should be investigated further to improve our understanding of TB epidemiology in complex multihost systems.

Data availability statement

Raw ONT tNGS reads from sites where mycobacterial DNA was detected as per Supplementary Table S1 were deposited in GenBank (Bioproject ID: PRJNA1185125).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Stellenbosch University Biological and Environmental Safety Research Ethics Committee (SU-BES-2023-29171). Section 20 approval was granted by the South African Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (DALRRD 12/11/1/7/7 (2867NT)).

Author contributions

MCM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RW: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GG: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ES: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CSW: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MAM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Financial support for this research was provided primarily by the (a) Wellcome Foundation (grant No. 222941/Z/21/Z). Additionally, (b) this project (grant No.: 101103171) was supported by the Global Health EDCTP3 Joint Undertaking and its members as well as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, (c) the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) Centre for Tuberculosis Research, and (d) the National Research Foundation South African Research Chair Initiative (grant No.: 86949). MCM was funded through a Stellenbosch University Postdoctoral Fellowship and SARChI grant No.: 86949. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the funders.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alicia McCall and Warren McCall from the Hluhluwe State Veterinary Office for making sample acquisition possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2025.1483162/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Wirth, T, Hildebrand, F, Allix-Béguec, C, Wölbeling, F, Kubica, T, Kremer, K, et al. Origin, spread and demography of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. PLoS Pathog. (2008) 4:e1000160. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000160

2. Botha, L, Gey van Pittius, NC, and Van Helden, PD. Mycobacteria and disease in southern Africa. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2013) 60:147–56. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12159

3. Miller, MA, Buss, P, Roos, EO, Hausler, G, Dippenaar, A, Mitchell, E, et al. Fatal tuberculosis in a free-ranging African elephant and one health implications of human pathogens in wildlife. Front Vet Sci. (2019) 6:18. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00018

4. Taye, H, Alemu, K, Mihret, A, Wood, JL, Shkedy, Z, Berg, S, et al. Global prevalence of Mycobacterium bovis infections among human tuberculosis cases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Zoonoses Public Health. (2021) 68:704–18. doi: 10.1111/zph.12868

5. Müller, B, Dürr, S, Alonso, S, Hattendorf, J, Laisse, CJ, Parsons, SD, et al. Zoonotic Mycobacterium bovis–induced tuberculosis in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. (2013) 19:899–908. doi: 10.3201/eid1906.120543

6. Gannon, BW, Hayes, CM, and Roe, JM. Survival rate of airborne Mycobacterium bovis. Res Vet Sci. (2007) 82:169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2006.07.011

7. Fine, AE, Bolin, CA, Gardiner, JC, and Kaneene, JB. A study of the persistence of Mycobacterium bovis in the environment under natural weather conditions in Michigan, USA. Vet Med Int. (2011) 2011:765430. doi: 10.4061/2011/765430

8. Allen, AR, Ford, T, and Skuce, RA. Does Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. bovis survival in the environment confound bovine tuberculosis control and eradication? A literature review. Vet. Med. Int. (2021) 2021:8812898. doi: 10.1155/2021/8812898

9. Palmer, MV, Waters, WR, and Whipple, DL. Investigation of the transmission of Mycobacterium bovis from deer to cattle through indirect contact. Am J Vet Res. (2004) 65:1483–9. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.1483

10. Barasona, JA, Torres, MJ, Aznar, J, Gortázar, C, and Vicente, J. DNA detection reveals Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex shedding routes in its wildlife reservoir the Eurasian wild boar. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2017) 64:906–15. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12458

11. Barbier, E, Boschiroli, ML, Gueneau, E, Rochelet, M, Payne, A, de Cruz, K, et al. First molecular detection of Mycobacterium bovis in environmental samples from a French region with endemic bovine tuberculosis. J Appl Microbiol. (2016) 120:1193–207. doi: 10.1111/jam.13090

12. Barbier, E, Chantemesse, B, Rochelet, M, Fayolle, L, Bollache, L, Boschiroli, ML, et al. Rapid dissemination of Mycobacterium bovis from cattle dung to soil by the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris. Vet Microbiol. (2016) 186:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.01.025

13. Zhang, H, Liu, M, Fan, W, Sun, S, and Fan, X. The impact of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in the environment on one health approach. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:994745. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.994745

14. Barbier, E, Rochelet, M, Gal, L, Boschiroli, ML, and Hartmann, A. Impact of temperature and soil type on Mycobacterium bovis survival in the environment. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0176315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176315

15. Pereira, AC, Pinto, D, and Cunha, MV. Unlocking environmental contamination of animal tuberculosis hotspots with viable mycobacteria at the intersection of flow cytometry, PCR, and ecological modelling. Sci Total Environ. (2023) 891:164366. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164366

16. Cook, JL. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: opportunistic environmental pathogens for predisposed hosts. Br Med Bull. (2010) 96:45–59. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq035

17. Liu, Q, Du, J, An, H, Li, X, Guo, D, Li, J, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: a seven-year follow-up study conducted in a certain tertiary hospital in Beijing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2023) 13:1205225. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1205225

18. Pavlik, I, Ulmann, V, Hubelova, D, and Weston, RT. Nontuberculous mycobacteria as sapronoses: a review. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:1345. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071345

19. Conde, C, Price-Carter, M, Cochard, T, Branger, M, Stevenson, K, Whittington, R, et al. Whole-genome analysis of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis IS900 insertions reveals strain type-specific modalities. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:660002. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.660002

20. McNees, AL, Markesich, D, Zayyani, NR, and Graham, DY. Mycobacterium paratuberculosis as a cause of Crohn’s disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2015) 9:1523–34. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1093931

21. Buddle, BM, Vordermeier, HM, Chambers, MA, and de Klerk-Lorist, LM. Efficacy and safety of BCG vaccine for control of tuberculosis in domestic livestock and wildlife. Front Vet Sci. (2018) 5:259. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00259

22. Verma, D, Chan, ED, and Ordway, DJ. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria interference with BCG-current controversies and future directions. Vaccine. (2020) 8:688. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040688

23. Huh, HJ, Kim, SY, Jhun, BW, Shin, SJ, and Koh, WJ. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics and understanding mechanisms of drug resistance in nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Infect Genet Evol. (2019) 72:169–82. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.10.003

24. Quan, TP, Bawa, Z, Foster, D, Walker, T, del, C, Rathod, P, et al. Evaluation of whole-genome sequencing for mycobacterial species identification and drug susceptibility testing in a clinical setting: a large-scale prospective assessment of performance against line probe assays and phenotyping. J Clin Microbiol. (2018) 56:10–1128. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01480-17

25. Bernitz, N, Kerr, TJ, Goosen, WJ, Chileshe, J, Higgitt, RL, Roos, EO, et al. Review of diagnostic tests for detection of Mycobacterium bovis infection in south African wildlife. Front. Vet Sci. (2021) 8:588697. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.588697

26. Fehr, J, Konigorski, S, Olivier, S, Gunda, R, Surujdeen, A, Gareta, D, et al. Computer-aided interpretation of chest radiography reveals the spectrum of tuberculosis in rural South Africa. NPJ Dig Med. (2021) 4:106. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00471-y

27. Kanipe, C, and Palmer, MV. Mycobacterium bovis and you: a comprehensive look at the bacteria, its similarities to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and its relationship with human disease. Tuberculosis. (2020) 125:102006. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2020.102006

28. Osei Sekyere, J, Maphalala, N, Malinga, LA, Mbelle, NM, and Maningi, NE. A comparative evaluation of the new GeneXpert MTB/RIF ultra and other rapid diagnostic assays for detecting tuberculosis in pulmonary and extra pulmonary specimens. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53086-5

29. Naidoo, P, Theron, G, Rangaka, MX, Chihota, VN, Vaughan, L, Brey, ZO, et al. The south African tuberculosis care cascade: estimated losses and methodological challenges. J Infect Dis. (2017) 216:S702–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix335

30. World Health Organization (WHO). Food and agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and world Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), Road map for zoonotic tuberculosis. Geneva: World Health Organization (2017).

31. MacGregor-Fairlie, M, Wilkinson, S, Besra, GS, and Goldberg Oppenheimer, P. Tuberculosis diagnostics: overcoming ancient challenges with modern solutions. Emerg Topics Life Sci. (2020) 4:435–48. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20200335

32. Pfyffer, GE. Mycobacterium: general characteristics, laboratory detection, and staining procedures. Manual Clin. Microbiol. (2015):536–69. doi: 10.1128/9781555817381.ch30

33. Pereira, AC, Pinto, D, and Cunha, MV. First time whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium bovis from the environment supports transmission at the animal-environment interface. J Hazard Mater. (2024) 472:134473. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134473

34. Beviere, M, Reissier, S, Penven, M, Dejoies, L, Guerin, F, Cattoir, V, et al. The role of next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the management of tuberculosis: practical review for implementation in routine. Pathogens. (2023) 12:978. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12080978

35. Adékambi, T, Drancourt, M, and Raoult, D. The rpoB gene as a tool for clinical microbiologists. Trends Microbiol. (2009) 17:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.09.008

36. Telenti, A, Marchesi, F, Balz, M, Bally, F, Böttger, EC, and Bodmer, T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. (1993) 31:175–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993

37. Landolt, P, Stephan, R, Stevens, MJ, and Scherrer, S. Three-reaction high-resolution melting assay for rapid differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex members. Microbiol Open. (2019) 8:919. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.919

38. Turenne, CY, Semret, M, Cousins, DV, Collins, DM, and Behr, MA. Sequencing of hsp65 distinguishes among subsets of the Mycobacterium avium complex. J Clin Microbiol. (2006) 44:433–40. doi: 10.1128/jcm.44.2.433-440.2006

39. Ghielmetti, G, Loubser, J, Kerr, TJ, Stuber, T, Thacker, TC, Martin, LC, et al. Advancing animal tuberculosis surveillance using culture-independent long-read whole-genome sequencing. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1307440. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1307440

40. Chin, KL, Sarmiento, ME, Norazmi, MN, and Acosta, A. DNA markers for tuberculosis diagnosis. Tuberculosis. (2018) 113:139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2018.09.008

41. Cooke, DM, Clarke, C, Kerr, TJ, Warren, RM, Witte, C, Miller, MA, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium bovis in nasal swabs from communal goats (Capra hircus) in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Front Microbiol. (2024) 15:1349163. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1349163

42. Davey, S. Challenges to the control of Mycobacterium bovis in livestock and wildlife populations in the south African context. Ir Vet J. (2023) 76:14. doi: 10.1186/s13620-023-00246-9

43. Goosen, WJ, Moodley, S, Ghielmetti, G, Moosa, Y, Zulu, T, Smit, T, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of Mycobacterium bovis DNA in GeneXpert® MTB/RIF ultra-positive, culture-negative sputum from a rural community in South Africa. One Health. (2024) 18:100702. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2024.100702

44. Sookan, L, and Coovadia, YM. A laboratory-based study to identify and speciate nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from specimens submitted to a central tuberculosis laboratory from throughout KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. S Afr Med J. (2014) 104:766–8. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.8017

45. Hlokwe, TM, Van Helden, P, and Michel, AL. Evidence of increasing intra and inter-species transmission of Mycobacterium bovis in South Africa: are we losing the battle? Prev Vet Med. (2014) 115:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.03.011

46. Sichewo, PR, Vander Kelen, C, Thys, S, and Michel, AL. Risk practices for bovine tuberculosis transmission to cattle and livestock farming communities living at wildlife-livestock-human interface in northern KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. PLoS Neglected Ttrop Dis. (2020) 14:e0007618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007618

47. Leclerc, MC, Haddad, N, Moreau, R, and Thorel, MF. Molecular characterization of environmental Mycobacterium strains by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of hsp65 and by sequencing of hsp65, and of 16S and ITS1 rDNA. Res Microbiol. (2000) 151:629–38. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)90129-3

48. Black, PA, De Vos, M, Louw, GE, Van der Merwe, RG, Dippenaar, A, Streicher, EM, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals genomic heterogeneity and antibiotic purification in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. BMC Genomics. (2015) 16:857–14. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2067-2

49. Clarke, C, Kerr, TJ, Warren, RM, Kleynhans, L, Miller, MA, and Goosen, WJ. Identification and characterisation of nontuberculous mycobacteria in African buffaloes (Syncerus caffer), South Africa. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:1861. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10091861

50. Zhang, Z, Schwartz, S, Wagner, L, and Miller, W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. (2000) 7:203–14. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478

51. Wick, RR, Judd, LM, and Holt, KE. Performance of neural network base calling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. (2019) 20:129. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1727-y

52. Steinig, E, and Coin, L. Nanoq: ultra-fast quality control for nanopore reads. J Open Source Softw. (2022) 7:2991. doi: 10.21105/joss.02991

53. Leger, A, and Leonardi, T. pycoQC, interactive quality control for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. J Open Source Softw. (2019) 4:1236. doi: 10.21105/joss.01236

54. Vierstraete, AR, and Braeckman, BP. Amplicon_sorter: a tool for reference-free amplicon sorting based on sequence similarity and for building consensus sequences. Ecol Evol. (2022) 12:e8603. doi: 10.1002/ece3.8603

56. Walters, E, Scott, L, Nabeta, P, Demers, AM, Reubenson, G, Bosch, C, et al. Molecular detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from stools in young children by use of a novel centrifugation-free processing method. J Clin Microbiol. (2018) 56:10–1128. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00781-18

57. Goosen, WJ, Clarke, C, Kleynhans, L, Kerr, TJ, Buss, P, and Miller, MA. Culture-independent PCR detection and differentiation of mycobacteria spp. in antemortem respiratory samples from African elephants (Loxodonta africana) and rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum, Diceros bicornis) in South Africa. Pathogens. (2022) 11:709. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11060709

58. Warren, RM, Gey van Pittius, NC, Barnard, M, Hesseling, A, Engelke, E, De Kock, M, et al. Differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by PCR amplification of genomic regions of difference. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis. (2006) 10:818–22.

59. Kamerbeek, J, Schouls, LEO, Kolk, A, van, M, van, D, Kuijper, S, et al. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. (1997) 35:907–14. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997

60. Abass, NA, Suleiman, KM, and El Jalii, IM. Differentiation of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates by their gyr B polymorphisms. Indian J Med Microbiol. (2010) 28:26–9. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.58724

61. World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Use of Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra on GeneXpert 10-colour instruments: WHO policy statement. Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/350154/9789240040090-eng.pdf (Accessed January 08, 2025).

62. McHugh, ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. (2012) 22:276–82. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031

63. Landis, JR, and Koch, GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. (1977) 33:159–74. doi: 10.2307/2529310

64. Courtenay, O, Reilly, LA, Sweeney, FP, Hibberd, V, Bryan, S, Ul-Hassan, A, et al. Is Mycobacterium bovis in the environment important for the persistence of bovine tuberculosis? Biol Lett. (2006) 2:460–2. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0468

65. Michel, AL, De Klerk, LM, van Pittius, NCG, Warren, RM, and Van Helden, PD. Bovine tuberculosis in African buffaloes: observations regarding Mycobacterium bovis shedding into water and exposure to environmental mycobacteria. BMC Vet Res. (2007) 3:23–7. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-3-23

66. Kasprowicz, VO, Achkar, JM, and Wilson, D. The tuberculosis and HIV epidemic in South Africa and the KwaZulu-Natal research institute for tuberculosis and HIV. J Infect Dis. (2011) 204:S1099–101. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir414

67. Phillips, CJC, Foster, CRW, Morris, PA, and Teverson, R. The transmission of Mycobacterium bovis infection to cattle. Res Vet Sci. (2003) 74:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5288(02)00145-5

68. World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Guidelines for the control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in livestock. Beyond Test Slaughter Paris. (2024) 37:3538. doi: 10.20506/woah.3538

69. Verma, R, Moreira, FMF, do, A, Walter, K, dos, P, Kim, E, et al. Detection of M. tuberculosis in the environment as a tool for identifying high-risk locations for tuberculosis transmission. Sci Total Environ. (2022) 843:156970. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156970

70. Nasrin, R, Uddin, MKM, Kabir, SN, Rahman, T, Biswas, S, Hossain, A, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF ultra for the rapid diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in a clinical setting of high tuberculosis prevalence country and interpretation of ‘trace’results. Tuberculosis. (2024) 145:102478. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2024.102478

71. Kim, SH, and Shin, JH. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria using multilocous sequence analysis of 16S rRNA, hsp65, and rpoB. J Clin Lab Anal. (2018) 32:22184. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22184

72. Delahaye, C, and Nicolas, J. Sequencing DNA with nanopores: troubles and biases. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0257521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257521

73. Falkinham, JO III. Surrounded by mycobacteria: nontuberculous mycobacteria in the human environment. J Appl Microbiol. (2009) 107:356–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04161.x

74. Gcebe, N, Rutten, V, Gey van Pittius, NC, and Michel, A. Prevalence and distribution of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in cattle, African buffaloes (Syncerus caffer) and their environments in South Africa. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2013) 60:74–84. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12133

75. Pavlik, I, Svastova, P, Bartl, J, Dvorska, L, and Rychlik, I. Relationship between IS901 in the Mycobacterium avium complex strains isolated from birds, animals, humans, and the environment and virulence for poultry. Clin Diagnostic Lab Immunol. (2000) 7:212–7. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.212-217.2000

76. Cowman, SA, James, P, Wilson, R, Cookson, WO, Moffatt, MF, and Loebinger, MR. Profiling mycobacterial communities in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0208018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208018

77. Comas, I, Homolka, S, Niemann, S, and Gagneux, S. Genotyping of genetically monomorphic bacteria: DNA sequencing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis highlights the limitations of current methodologies. PLoS One. (2009) 4:37815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007815

78. Wilson, S, Lane, A, Rosedale, R, and Stanley, C. Concentration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from sputum using ligand-coated magnetic beads. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. (2010) 14:1164–8.

79. Kato-Maeda, M, Metcalfe, JZ, and Flores, L. Genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: application in epidemiologic studies. Future Microbiol. (2011) 6:203–16. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.165

80. Martínez-Guijosa, J, Romero, B, Infantes-Lorenzo, JA, Díez, E, Boadella, M, Balseiro, A, et al. Environmental DNA: a promising factor for tuberculosis risk assessment in multi-host settings. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0233837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233837

81. Dowdell, K, Haig, SJ, Caverly, LJ, Shen, Y, LiPuma, JJ, and Raskin, L. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in drinking water systems–the challenges of characterization and risk mitigation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. (2019) 57:127–36. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.03.010

82. Martinez, L, Verma, R, Croda, J, Horsburgh, CR, Walter, KS, Degner, N, et al. Detection, survival and infectious potential of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the environment: a review of the evidence and epidemiological implications. Eur Respir J. (2019) 53:1802302. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02302-2018

83. Saingam, P, Li, B, and Yan, T. Use of amplicon sequencing to improve sensitivity in PCR-based detection of microbial pathogen in environmental samples. J Microbiol Methods. (2018) 149:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.05.005

84. Tessler, M, Neumann, JS, Afshinnekoo, E, Pineda, M, Hersch, R, Velho, LFM, et al. Large-scale differences in microbial biodiversity discovery between 16S amplicon and shotgun sequencing. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:6589. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06665-3

85. Sanoussi, CND, Affolabi, D, Rigouts, L, Anagonou, S, and de Jong, B. Genotypic characterization directly applied to sputum improves the detection of Mycobacterium africanum west African 1, under-represented in positive cultures. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2017) 11:e0005900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005900

86. Pereira, AC, Tenreiro, A, Tenreiro, R, and Cunha, MV. Stalking Mycobacterium bovis in the total environment: FLOW-FISH & FACS to detect, quantify, and sort metabolically active and quiescent cells in complex matrices. J Hazard Mater. (2022) 432:128687. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128687

87. Falotico, R, and Quatto, P. Fleiss’ kappa statistic without paradoxes. Quality & Quantity. (2015) 49:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-0003-1

Keywords: culture-independent detection, environmental transmission, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, targeted next generation sequencing, One Health, Oxford Nanopore Technologies

Citation: Matthews MC, Cooke DM, Kerr TJ, Loxton AG, Warren RM, Ghielmetti G, Streicher EM, Witte CS, Miller MA and Goosen WJ (2025) Evidence of Mycobacterium bovis DNA in shared water sources at livestock–wildlife–human interfaces in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1483162. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1483162

Edited by:

María Jimena Marfil, Universidad de Buenos Aires, ArgentinaReviewed by:

Vivek Kapur, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesStephanie Salyer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States

Margarida Simões, University of Evora, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Matthews, Cooke, Kerr, Loxton, Warren, Ghielmetti, Streicher, Witte, Miller and Goosen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wynand J. Goosen, Z29vc2Vud2pAdWZzLmFjLnph

†These authors share senior authorship

Megan C. Matthews

Megan C. Matthews Deborah M. Cooke

Deborah M. Cooke Tanya J. Kerr

Tanya J. Kerr Andre G. Loxton

Andre G. Loxton Robin M. Warren

Robin M. Warren Giovanni Ghielmetti

Giovanni Ghielmetti Elizabeth M. Streicher1

Elizabeth M. Streicher1 Michele A. Miller

Michele A. Miller Wynand J. Goosen

Wynand J. Goosen