94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Vet. Sci., 26 July 2024

Sec. Veterinary Infectious Diseases

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2024.1394814

This article is part of the Research TopicWildlife-Domestic Animal Interface: Threat or Sentinel?View all 9 articles

Haifeng Liu1†

Haifeng Liu1† Siping Fan1†

Siping Fan1† Xiaoli Zhang2†

Xiaoli Zhang2† Yu Yuan1†

Yu Yuan1† Wenhao Zhong1

Wenhao Zhong1 Liqin Wang3

Liqin Wang3 Chengdong Wang4

Chengdong Wang4 Ziyao Zhou1

Ziyao Zhou1 Shaqiu Zhang1

Shaqiu Zhang1 Yi Geng1

Yi Geng1 Guangneng Peng1

Guangneng Peng1 Ya Wang1

Ya Wang1 Kun Zhang1

Kun Zhang1 Qigui Yan1

Qigui Yan1 Yan Luo1

Yan Luo1 Keyun Shi2*

Keyun Shi2* Zhijun Zhong1*

Zhijun Zhong1*Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-EC) is regarded as one of the most important priority pathogens within the One Health interface. However, few studies have investigated the occurrence of ESBL-EC in giant pandas, along with their antibiotic-resistant characteristics and horizontal gene transfer abilities. In this study, we successfully identified 12 ESBL-EC strains (8.33%, 12/144) out of 144 E. coli strains which isolated from giant pandas. We further detected antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), virulence-associated genes (VAGs) and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) among the 12 ESBL-EC strains, and the results showed that 13 ARGs and 11 VAGs were detected, of which blaCTX-M (100.00%, 12/12, with 5 variants observed) and papA (83.33%, 10/12) were the most prevalent, respectively. And ISEcp1 (66.67%, 8/12) and IS26 (66.67%, 8/12) were the predominant MGEs. Furthermore, horizontal gene transfer ability analysis of the 12 ESBL-EC showed that all blaCTX-M genes could be transferred by conjugative plasmids, indicating high horizontal gene transfer ability. In addition, ARGs of rmtB and sul2, VAGs of papA, fimC and ompT, MGEs of ISEcp1 and IS26 were all found to be co-transferred with blaCTX-M. Phylogenetic analysis clustered these ESBL-EC strains into group B2 (75.00%, 9/12), D (16.67%, 2/12), and B1 (8.33%, 1/12), and 10 sequence types (STs) were identified among 12 ESBL-EC (including ST48, ST127, ST206, ST354, ST648, ST1706, and four new STs). Our present study showed that ESBL-EC strains from captive giant pandas are reservoirs of ARGs, VAGs and MGEs that can co-transfer with blaCTX-M via plasmids. Transmissible ESBL-EC strains with high diversity of resistance and virulence elements are a potential threat to humans, animals and surrounding environment.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli (ESBL-EC), which is resistant to many β-lactamase antibiotics, is one of the top priority pathogens within the One Health interface, classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1, 2). In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of ESBL-EC in animals, particularly in wildlife population (1, 3–6). This has sparked concerns among researchers and experts in the field of animal health, as the emergence of ESBL-producing bacteria has limited the treatment options available for bacterial infections in animals (7). The predominant ESBL genes include blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M, of which blaCTX-M is the most prevalent type in Enterobacteriaceae, especially in E. coli (7). These ESBL genes can be transferred between different bacteria via mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence-associated genes (VAGs), accelerating the occurrence of clinical ESBL-producing pathogen (8, 9).

The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) is the national symbol of China and a popular attraction for tourists visiting zoos in China and other countries (10, 11). In addition, the wild release plan of captive giant pandas implemented by the Chinese government has raised concerns about the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) bacteria to other wildlife and the natural environment, or the potential transmission of AMR bacteria from other wildlife to giant pandas (12, 13). However, there have been few of publications on the presence of ESBL-EC in giant pandas in recent years (14). Qin et al. (9) analyzed 96 E. coli strains isolated from healthy captive giant pandas from 2012 to 2013 and found that 25 of those were ESBL-EC, and three types of ESBL genes (blaTEM, blaCTX-M, and blaOXA) were detected. Another study of diseased captive giant pandas detected four ESBL-EC one atypical enteropathogenic E. coli isolated in 2015, and three extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli isolated in 2008 and 2012, and these four ESBL-EC were resistant to more than eight antibiotics, and two variants of blaCTX-M (blaCTX-M-55 and blaCTX-M-105) were detected (14). The above studies indicate that ESBL-EC from healthy or diseased captive giant pandas carrying ESBL genes exhibit serious AMR and the occurrence of ESBL-EC poses a significant challenge to antibiotic treatment for giant pandas.

Our previous study showed the presence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in clinically healthy captive giant pandas and demonstrated that E. coli strains were a pool of ARGs, VAGs, and MGEs (15). However, the characteristics of ESBL-EC from those captive giant pandas, especially regarding AMR characteristics including ARGs, VAGs, MGEs, phylogenetic groups, MLST, and the ability for horizontal gene transfer (HGT), remain unknown and need to be clarified. This study provides a deeper understanding of the AMR profile of ESBL-EC strains from captive giant pandas, offering insights into their potential impact on public health and environmental ecosystems.

From 2020 to 2021, 117 fresh fecal samples from different individuals were collected from captive giant pandas living at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (CRBGP). From 2018 to 2021, 27 fecal samples were collected from wild giant pandas living in the Sichuan Wolong National Nature Reserve. All giant pandas involved in this study were in a healthy state and did not exhibit any abnormal symptoms, as confirmed by a professional veterinarian. Isolation and identification of E. coli were performed as previously described (16–18). Briefly, fecal samples were immediately placed in sterile disposable sampling tubes, stored in a cooler at 2°C ~ 8°C, and transported to Sichuan Agricultural University for isolation and identification within 24 h. Samples were enriched in LB broth, and all the isolates were confirmed by Gram staining, MacConkey agar (Solarbio, Beijing), eosin methylene blue agar (Chromagar, France), and biochemical identification by API 20E system (BioMerieux, France) (18). The 16 S rRNA of all strains was further amplified to confirm the isolate as E. coli (16). These strains were stored in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing 50% glycerol at −20°C for further analysis.

Phenotypic screening was measured using the double-disc diffusion test as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2023). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2023). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, M100-33Ed, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2023). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, M100-33Ed, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Briefly, antibiotic discs (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) of cefotaxime (CTX, 30 μg), cefotaxime plus clavulanic acid (CTL, 30/10 μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30 μg) and ceftazidime plus clavulanic acid (CAL, 30/10 μg) were used to screen for ESBL-EC isolates. When the diameter of the inhibition zone increased by ≥5 mm with clavulanic acid, compared with that without clavulanic acid, the isolate is considered as ESBL-EC.

All ESBL-EC isolates were tested using the standard disk diffusion method recommended by the CLSI for susceptibility to fifteen antimicrobials. We used antimicrobial disks (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) in six categories: β-lactams (aztreonam, AZM, 30 μg; ampicillin, AMP, 10 μg; amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 2:1, AMC, 20/10 μg; ampicillin/sulbactam 1:1, SAM, 10/10 μg; cefazolin, CEZ, 20 μg; cefotaxime, CTX, 30 μg; ceftriaxone, CRO, 30 μg; ceftazidime, CAZ, 30 μg), aminoglycosides (gentamicin, GM, 10 μg; amikacin, AMK, 30 μg), quinolones (ciprofloxacin, CIP, 5 μg), tetracyclines (tetracycline, TET, 30 μg; doxycycline, DOX, 30 μg), sulfonamides (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, SXT, 23.75/1.25 μg) and amide alcohols (chloramphenicol, CHL, 30 μg). Results were interpreted in according to CLSI 2023 criteria. E. coli ATCC25922 was used as a control. Fifteen antimicrobials were selected for the experiment: AZM, AMC, SAM, CEZ, CTX and CRO were used in the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, and AMP, CAZ, GM, AMK, CIP, TET, DOX, SXT and CHL were found to be resistant to E. coli in giant pandas in our previous study (18). The multidrug resistant (MDR) strain was defined as being resistant to at least three antimicrobial categories (19).

Total genomic DNA was extracted from ESBL-EC isolates using the TaKaRa Bacteria DNA Kit (Takara Biomedical Technology Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality was checked by ultraviolet-absorbance (ND1000, Nanodrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNA samples were stored at −20°C for subsequent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection.

We screened for 15 ARGs (including ESBL genes: blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M), 20 VAGs (5 categories) and 16 MGEs by PCR. Primers were synthesized by Huada Gene Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Primers and the amplification conditions are shown in Supplementary Table S1. PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis in a 1.0% agarose gel stained with GoldViewTM (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and photographed under ultraviolet light using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP omnipotent imager (Bole, United States). All positive PCR products were sequenced with Sanger sequencing in both directions by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Sequences were analyzed online using the BLAST function of NCBI.1

To determine the transfer ability of resistance genes, all ESBL-EC isolates were selected as donors for conjugation. The azide-resistant E. coli J53 was used as recipient bacteria. Donor and recipient strains were grown separately overnight in 4 mL of LΒ-Broth. Volumes of 0.2 mL of donor and 0.8 mL of recipient strains were added to 4 mL of LB broth and cultured overnight. Transconjugants were selected on Azide dextrose agar plates (150 mg/mL; Qingdao Hope Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. Qingdao, China) supplemented with cefotaxime (4 mg/L; Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). Transfer frequencies were calculated per recipient cell. HGT frequency was calculated by dividing the number of transconjugants by the number of recipient. All transconjugants were confirmed by PCR for genes encoding ESBL production and tested for susceptibility to the same antibiotic used against the donor isolates. And the same ARGs, VAGs, MGEs carried by donor isolates were detected by PCR for all transconjugants.

The plasmid replicon types of ESBL-producing bacteria (donor) and their transconjugants were determined as previously described (20). Briefly, amplification by PCR was performed with 18 pairs of primers recognizing HI1, HI2, I1, X, L/M, N, FIA, FIB, W, Y, P, FIC, A/C, T, FIIA, FrepB, K, and B/O in 5 multiplex and 3 simplex reactions. The PCR products were analyzed as described in 2.4. The primers and the amplification conditions are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Phylogenetic grouping for 12 ESBL-EC is categorized into four major phylogenetic classes (A, B1, B2 and D) using triplex PCR targeting three genes (ChuA, yjaA and TSPE4.C2) according to Clermont et al. (21). For multilocus sequence typing (MLST), PCR protocols were performed as previously described (22). All the primers and the amplification conditions are shown in Supplementary Table S1. All positive PCR products were sequenced with Sanger sequencing in direction by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Sequences of housekeeping gene for MLST were analyzed online using the pubMLST database.2

The goeBURST algorithm in phyloviz 2.0 was used for clustering analysis of STs for 12 ESBL-EC isolates, which divided the STs into several clusters consist of closely related STs with two allelic differences (23). A clonal complex is typically composed of a single predominant genotype and closely related genotype (24).

A total of 144 E. coli isolates (one isolate per fecal sample) were obtained from 117 captive and 27 wild giant pandas, respectively. Twelve ESBL-EC isolates (10.26%, 12/117) were identified from captive giant pandas, while no ESBL-EC isolate was detected from wild giant pandas.

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing results of 12 ESBL-EC to 15 antibiotics in 6 categories were shown in Table 1. Top 5 resistance rates to 15 antimicrobial agents were AMP (100.00%, 12/12), CEZ (100.00%, 12/12), CTX (100.00%, 12/12), CRO (100.00%, 12/12), and TET (50.00%, 6/12). The resistance rate to CIP (8.33%, 1/12) was the lowest, and the remaining 9 antibiotics ranged from 41.67% (AZM, DOX) to 16.67% (SAM, CAZ) (Table 1). For the 6 antibiotic categories, the resistance rate to β-lactam antibiotics was the highest (100%, 12/12), followed by tetracyclines (50%, 6/12), aminoglycosides (33.33%, 4/12), sulfonamides (33.33%, 4/12) and amide alcohols (33.33%, 4/12). The resistance rate to quinolones antibiotics was the lowest (8.33%, 1/12). Phenotypic characterization of antibiotic resistance indicated that 50% ESBL-EC isolates (GP003, GP004, GP0012, GP022, GP030 and GP065) were classified as MDR strains, of which strain GP003 was resistant to 12 antibiotics.

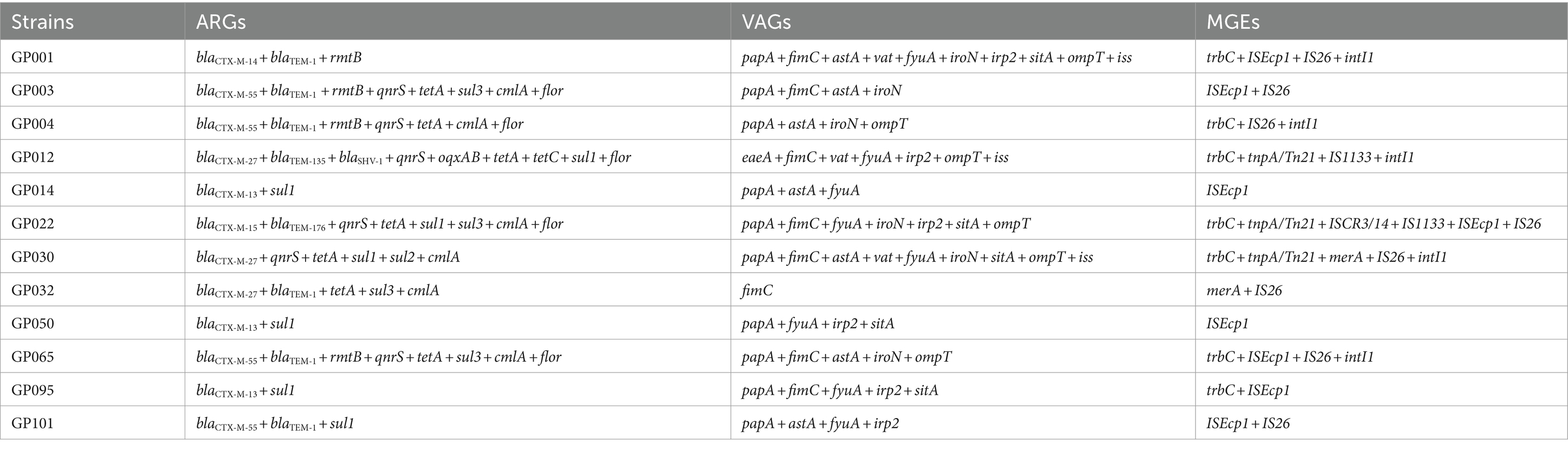

The detection rates of ARGs, VAGs and MGEs for 12 ESBL-EC isolates are shown in Table 2.We detected 13 out of 15 currently known ARGs, including β-lactamase: blaCTX-M (100.00%, 12/12), blaTEM (66.67%, 8/12), blaSHV (8.33%, 1/12), tetracyclines: tetA (58.33%, 7/12), tetC (8.33%, 1/12), sulfonamides: sul1 (58.33%, 7/12), sul3 (33.33%, 4/12), sul2 (8.33%, 1/12); quinolones: qnrS (50.00%, 6/12), oqxAB (8.33%, 1/12), amide alcohols: cmlA (50.00%, 6/12), flor (41.66%, 5/12), and aminoglycosides: rmtB (33.33%, 4/12). The armA of aminoglycoside ARGs and qnrA of quinolone ARGs were not detected. Furthermore, all ESBL-encoding genes were sequenced to identify the variants, totally 1 variant of blaSHV, 3 variants of blaTEM, and 5 variants of blaCTX-M were detected. The most prominent blaCTX-M variant observed was blaCTX-M-55 (33.33%, 4/12), followed by blaCTX-M-13 (25.00%, 3/12), blaCTX-M-27 (25.00%, 3/12), blaCTX-M-14 (8.33%, 1/12), and blaCTX-M-15 (8.33%, 1/12). For blaTEM, the most prominent variant was blaTEM-1 (50.00%, 6/12), followed by blaTEM-135 (8.33%, 1/12) and blaTEM-176 (8.33%, 1/12). For blaSHV, only blaSHV-1 (8.33%, 1/12) was detected.

Table 2. Distribution of ARGs, VAGs and MGEs in 12 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from captive giant pandas.

A total of 11 VAGs in 4 categories out of 20 currently known VAGs in 5 categories were detected among 12 ESBL-EC isolates, with a maximum of 10 VAGs detected in strain GP001. The VAGs detected included adhesion-related genes: papA (83.33%, 10/12), fimC (66.67%. 8/12), eaeA (8.33%, 1/12); iron transport-related genes: fyuA (66.67%, 8/12), iroN (50.00%, 6/12), Irp2 (50.00%, 6/12), sitA (41.67%, 5/12); invasion-and toxin-related genes: astA (58.33%, 7/12), vat (25.00%, 3/12), and antiserum survival factor: ompT (50.00%, 6/12), iss (25.00%, 3/12). The remaining 9 VAGs were not detected.

Eight out of 16 currently known MGEs were detected in 12 ESBL-EC isolates, including ISEcp1 (66.67%, 8/12), IS26 (66.67%, 8/12), trbC (58.33%, 7/12), intI1 (41.67%, 5/12), tnpA/Tn21 (25.00%, 3/12), merA (16.67%, 2/12), IS1133 (16.67%, 2/12), and ISCR3/14 (8.33%, 1/12). The other 8 MGEs were not detected. We further analyzed the integron gene cassettes of isolates that carried intI1, and no gene cassettes detected.

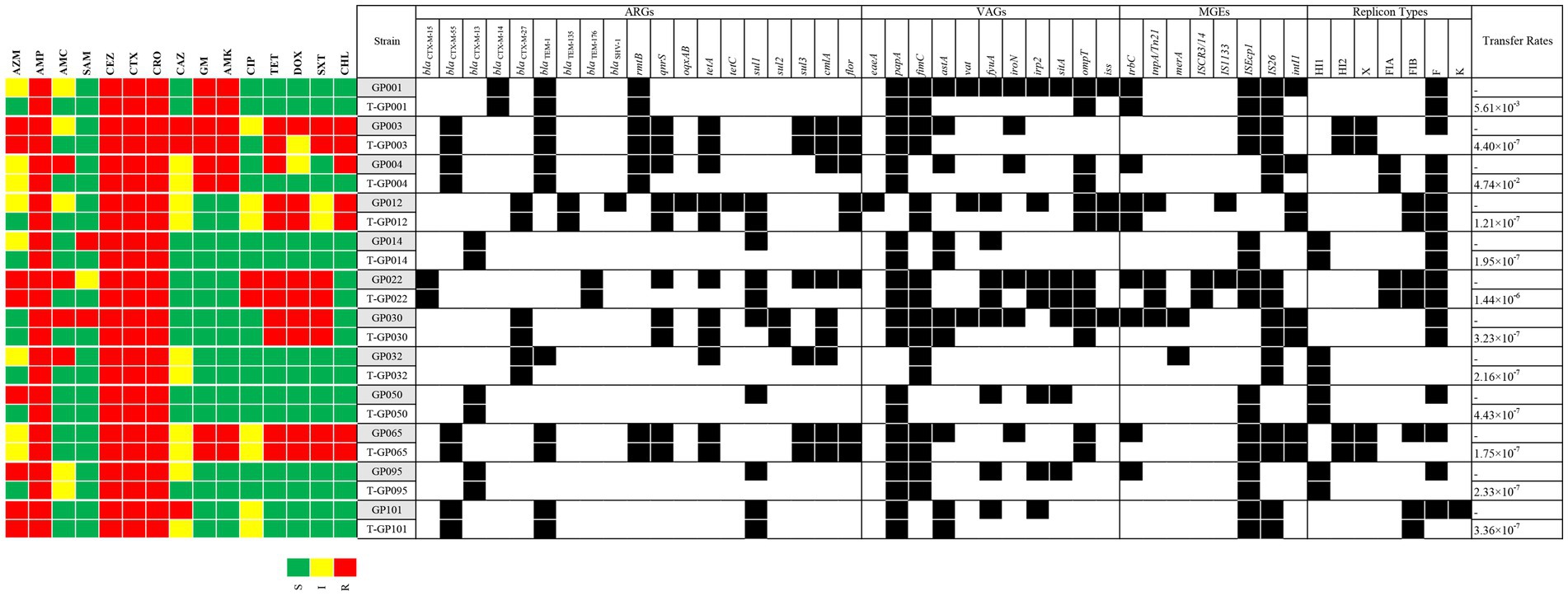

We further investigated the transfer ability of resistance genes. All the ESBL-EC isolates transferred their cefotaxime resistance determinant to the azide resistant E. coli J53 recipient, with transfer frequencies ranging from 1.21 × 10−7 (strain GP012) to 4.74 × 10−2 (strain GP004) (Figure 1). The 12 transconjugants were confirmed to possessed ESBL-producing phenotype and carried blaCTX − M gene. In addition, resistance to aminoglycosides, quinolones, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, amide alcohols and other β-lactams were also co-transferred to the recipient along with cefotaxime resistance. The detail of transfer frequencies of ARGs, VAGs and MGEs was showed in Figure 1. Among them, the conjugation transfer frequencies of ARGs of blaCTX − M, rmtB and sul2, VAGs of papA, fimC and ompT, MGEs of ISEcp1, IS26 and ISCR3/14 were 100.00%. However, ARGs of blaSHV, tetC and oqxAB, VAGs of iroN, vat and eaeA, MGEs of merA and IS1133 were not detected in the transconjugants, indicating that no horizontal transfer of these genes occurred. PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) showed that the 12 ESBL-EC isolates contained plasmids with different replicons, including IncFrepB (91.67%, 11/12), IncHI1 (33.33%, 4/12), IncFIB (33.33%, 4/12), IncHI2 (16.67%, 2/12), IncX (16.67%, 2/12), IncFIA (16.67%, 2/12) and IncK (8.33%, 1/12). Moreover, PBRT of the transconjugants confirmed that among the 7 replicons, 6 conjugative plasmid types (IncFrepB, IncHI1, IncFIB, In-cHI2, IncX and IncFIA) can transfer the ESBL genes, only IncK was not conjugated.

Figure 1. A heat-map showing the comparison of the twelve E. coli donors and the resultant transconjugants for antimicrobial resistance profile, ARGs, VAGs, MGEs, plasmid replicon types, and conjugative transfer rates. The “T” in front of the strain name represents the transconjugant. Black squares indicate the identified ARGs, VAGs, MGEs, and replicon types. S, susceptible; I, intermediate susceptible; R, resistant. Only positive ARGs, VAGs, MGEs, and replicon types are shown.

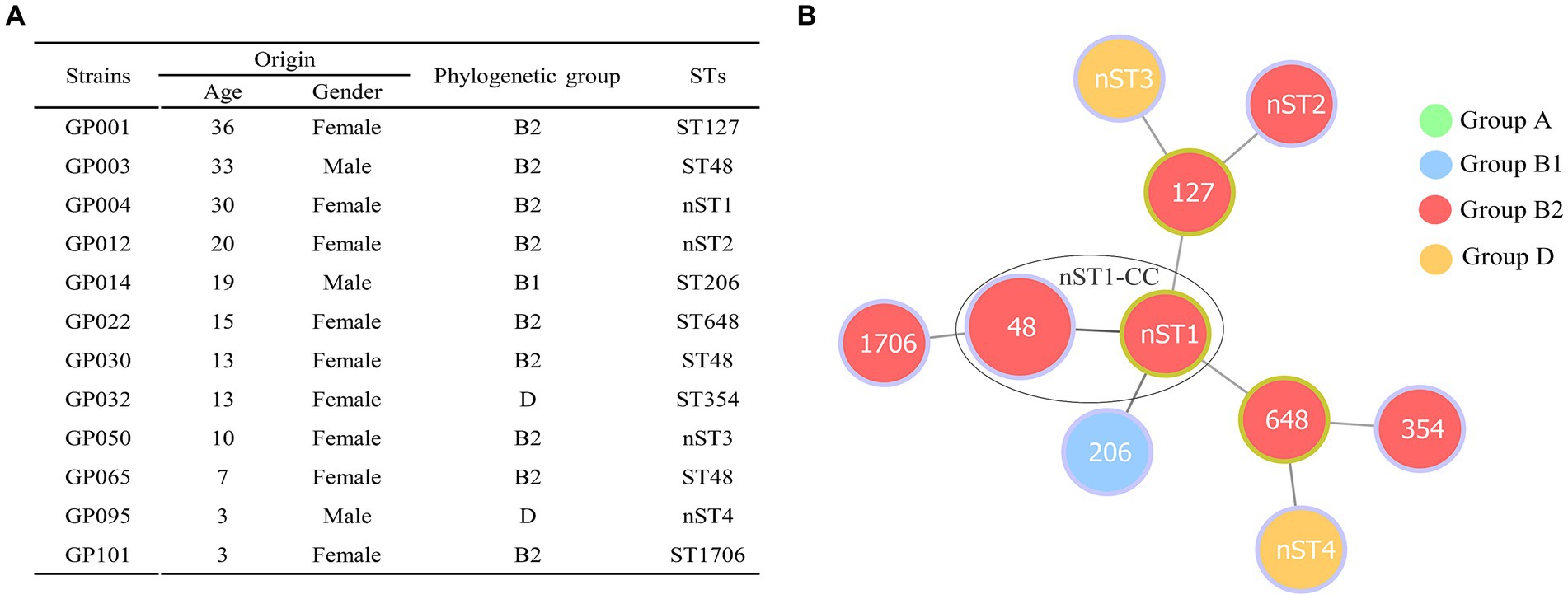

Phylogenetic screening of 12 ESBL-EC isolates confirmed that group B2 (75.00%, 9/12) was the most commonly observed phenotype, followed by group D (16.67%, 2/12) and group B1 (8.33%, 1/12) (Figure 2A). Group A was not detected in our study. MLST analysis showed that 10 different STs (containing 6 known STs and 4 new STs) were observed in 12 ESBL-EC isolates, of which ST48 was the most frequent (25%, 3/12), the other 9 STs contained only one strain. In addition, 4 new STs (containing GP004, GP012, GP050 and GP095) were observed and named as nST1, nST2, nST3, and nST4, respectively. By using goeBURST algorithm in phyloviz, only one clonal complex (nST1-CC, containing ST48 and the founder nST1) was observed among 10 STs (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Distribution of phylogenetic groups and STs in 12 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from giant pandas. (A) The detailed information of phylogenetic groups and STs in 12 ESBLs-EC isolates from giant pandas. (B) Minimum spanning tree of MLST types in 12 ESBLs-EC strains. The size of circle indicates the proportion of isolates belonging to the ST. The color within each circle represents phylogroups and indicates the proportion of isolates belonging to different phylogroups. Each link between circles indicates a mutational event and the distance is scaled as the number of allele differences between STs. The yellow-green outlines of the circles represent the founder ST of a clonal complex (CC), and the other STs (with purple outlines of the circles) are derived from the founder ST with two allelic differences. A high diversity of STs (10 STs were identified) was observed in 12 ESBLs-EC strains, ST48 being the most prevalent lineage. Only one clonal complex (nST1-CC, containing ST48 and nST1) was observed in the present study.

Our present study showed that ESBL-EC from giant pandas exhibited a diversity of ST clonal lineages and subtypes of blaCTX-M. ESBL-EC become a pool of ARGs, VAGs and MGEs that facilitate horizontal gene transfer mainly mediated by plasmids. Releasing captive giant pandas back into their natural habitat could potentially lead to the release of these bacteria into the environment, contributing to environmental pollution caused by AMR bacteria.

The production of ESBLs is one of the most common markers of AMR in Enterobacteriaceae (25). ESBL-EC has been widely reported in captive wildlife, including giant pandas (5, 6, 14, 26, 27). In this study, we detected 12 ESBL-EC strains in captive giant pandas and found that the prevalence of ESBL-EC (10.26%, 12/117) was lower than that reported in other studies (26.04 and 80.00%, respectively) (9, 14). The emergence of ESBL-EC in captive giant pandas may originate from various sources, including exposure to antibiotics in captivity during veterinary care, cross-contamination from human contact, environmental reservoirs harboring resistant bacteria, and transmission from other animals (28). In addition, ESBL-EC has been widely detected in other wildlife, such as magnificent frigatebirds, carnivorous mammals (Neovison vison and Martes foina), owls, vultures and coatis (1, 29, 30). In our present study, no ESBL-EC was detected in 27 fecal samples from wild giant pandas. The difficulty in isolating ESBL-EC from wild pandas likely results from their limited exposure to human-related factors that contribute to antibiotic resistance, logistical challenges in obtaining samples non-invasively, and the potentially low abundance or intermittent shedding of these bacteria in wild populations (31). Nevertheless, continuous epidemiological surveillance for ESBL-EC in giant pandas are still required, especially as the giant panda reintroduction project in China is ongoing.

Among the ESBL-EC strains observed in our present study, 50.00% of the strains were MDR, which was lower than that in studies from other wild animals (69.05% ~ 100.00%) (3, 29, 32). The existence of MDR phenotypes revealed that the co-occurrence of ESBLs with other resistance traits in E. coli isolates results in the development of their resistance spectrum to β-lactams and other antimicrobial agents (33–35). To better understand the types of ESBLs, we further analyzed the ESBL genes in 12 ESBL-EC strains. Our result showed that blaCTX-M (100.00%, 12/12) was the predominant ESBL gene. Sequence-based analysis showed 5 variants of blaCTX-M (blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-13, blaCTX-M-27, blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-15) exist in the 12 ESBL-EC, of which blaCTX-M-55 (33.33%, 4/12) was the most common. The prevalence of blaCTX-M-55 was also observed in other studies in ESBL-EC from diseased captive giant pandas (75.00%) (14), and other animals (swans, squirrel monkeys, black hat hanging monkeys, gibbon monkeys and phoenicopteridae, 34.80%), leading the authors to speculated that blaCTX-M-55 may become the major blaCTX-M variant in Chinese zoo animals (6). The predominance of blaCTX-M-55 detected in our study provided further evidence for this speculation.

The spread of β-lactamases is often associated with plasmid-mediated horizontal transfer of ARGs encoding β-lactamase resistance, specifically the blaCTX-M gene (33). In our study, conjugation experiments confirmed that the blaCTX-M gene carried by ESBL-EC can be horizontally transferred by conjugation plasmids, and the transconjugants also showed ESBL-producing phenotypes. PCR-based replicon typing showed that the conjugative plasmids of ESBL-EC included IncFrepB, IncHI1, IncFIB, IncHI2, IncX, and IncFIA. These incompatibility-group types have also been identified in plasmids from ESBL-EC worldwide in previous studies (36–39).

Among the 12 ESBL-EC, the ARGs of blaCTX − M, rmtB and sul2, the VAGs of papA, fimC and ompT, and the MGEs of ISEcp1, IS26 and ISCR3/14 were all horizontally transferred which mediated by plasmid conjugation. All aminoglycoside (gentamicin and amikacin) resistant strains carrying the rmtB gene were co-transferred with the blaCTX-M-55 or blaCTX-M-14 gene. The other aminoglycoside-resistant encoding gene armA, which has been previously reported to be linked with blaCTX-M and located in the same plasmid (40–42), while armA was not detected in our study. In addition, horizontal gene transfer facilitates the acquisition of virulence factors, and provides an evolutionary pathway for the development of pathogenicity (43). All of the papA, fimC, and ompT carried by ESBL-EC in this study can be horizontally transferred. In particular, the papA (encoding type P fimbriae) and fimC (encoding type I fimbriae) have been reported to be related to pathogenicity and colonization of fimbriae in extraintestinal infections caused by E. coli (44, 45). The ompT (encoding outer membrane protein T) has been reported to potentially contribute to bacterial cell attachment to host epithelial tissues (such as the urinary tract) and establishment a persistent bacterial infection (46). Therefore, co-transfer of papA, fimC and ompT with the blaCTX-M gene may increase the pathogenicity of bacterial diseases and make them more difficulty to treat in captive giant pandas. It is worth noting that six (papA, fimC, fyuA, irp2, sitA and ompT) of the seven VAGs observed in strain GP022 were all successfully co-transferred with blaCTX-M-15. The blaCTX-M-15 gene has previously been reported to be extensively associated with highly virulent E. coli (such as B2-ST131 E. coli) (47), our present finding also suggests that the co-localization of VAGs and blaCTX-M-15 may potentially increase the virulence of E. coli. Regarding MGEs, all of the ISEcp1 and IS26 carried by ESBL-EC were co-transferred with blaCTX-M gene in our study. It has been widely reported that ISEcp1 and IS26 are located upstream of blaCTX-M and play a key role in the dissemination of blaCTX-M (33, 48–50), and ISEcp1 can enhance the expression of blaCTX-M (49). Moreover, the TrbC protein is essential for the conjugative transfer of the IncF plasmid (51). In our present study, trbC was also observed to co-transfer with blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-27, leading us to deduce that trbC may be involved in the plasmid-mediated HGT of the blaCTX-M gene between different strains.

The population structure of ESBL-EC clones can be determined by phylogenetic grouping and MLST (7). Our results showed that ESBL-EC belonged predominantly to group B2 (75.00%), which was consistent with previous studies from waterfowl birds, companion animals, and broiler chickens (52–54). We also used MLST to better understand the clonal lineages of the 12 ESBL-EC. Twelve ESBL-EC belonged to 10 different STs, including six known STs and four new STs. Three isolates detected in our study belonged to ST127, ST354 and ST648, which were among the top 20 ExPEC lineages worldwide and were responsible for the majority of extraintestinal diseases, contributing significantly to the global burden of infectious disease (55). In particular, the isolate (GP022) encoding blaCTX-M-15 belongs to clone B2-ST648, and clone ST648 is mostly combined with MDR and virulence, which is one of the most common international epidemic high-risk clone lineages at the human-animal-environmental interface worldwide (1, 56, 57). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the E. coli B2-ST648 isolate encoding blaCTX-M-15 from captive giant pandas. In addition, the remaining STs (ST48, ST206, and ST1706) identified in our study have also been detected in E. coli from humans and other animals (6, 58–60). In general, ESBL-EC detected in captive giant pandas exhibited a diversity of clonal lineages, which may be due to the extensive spread of ESBL-EC mediated by the HGT of ESBL genes.

Our study revealed the diversity of ESBL-EC from captive giant pandas, along with their carriage of ARGs, VAGs and MGEs. This suggests that pandas in zoo environments could potentially serve as reservoirs for the spread of ARGs, posing risks to public health. Consequently, releasing ESBL-EC positive pandas from the zoo requires cautious consideration and thorough risk assessment to prevent the potential introduction of AMR bacteria into natural ecosystems.

All strain sequencing data has been deposited in the NCBI database, accessible using the accession numbers: PP988284-PP988307. Other data for this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

HL: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SF: Data curation, Writing – original draft. XZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. YY: Data curation, Writing – original draft. WZ: Supervision, Writing – original draft. LW: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. CW: Supervision, Writing – original draft. ZiZ: Supervision, Writing – original draft. SZ: Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. YG: Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. GP: Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. YW: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. KZ: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. QY: Writing – review & editing. YL: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. KS: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. ZhZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The animal study was approved by the Sichuan Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (No. DYY-20130306). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Science and Technology Achievements Transfer Project in Sichuan province (2022JDZH0026), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFD0500900, 2016YFD0501009) and the Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding Research Foundation (No. CPF2017-05, CPF2015-4).

We thank Dr. Wei Li from University of Munich for the English language revision.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2024.1394814/full#supplementary-material

1. Ewbank, AC, Fuentes-Castillo, D, Sacristan, C, Esposito, F, Fuga, B, Cardoso, B, et al. World Health Organization critical priority Escherichia coli clone ST648 in magnificent frigatebird (Fregata magnificens) of an uninhabited insular environment. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:940600. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.940600

2. Tacconelli, E, Carrara, E, Savoldi, A, Harbarth, S, Mendelson, M, Monnet, DL, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2018) 18:318–27. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30753-3

3. Carvalho, I, Tejedor-Junco, MT, Gonzalez-Martin, M, Corbera, JA, Suarez-Perez, A, Silva, V, et al. Molecular diversity of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from vultures in Canary Islands. Environ Microbiol Rep. (2020) 12:540–7. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12873

4. Li, X, Zhu, X, and Xue, Y. Drug resistance and genetic relatedness of Escherichia coli from mink in Northeast China. Pak Vet J. (2023) 43:824–827. doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2023.062

5. VinodhKumar, OR, Karikalan, M, Ilayaraja, S, Sha, AA, Singh, BR, Sinha, DK, et al. Multi-drug resistant (MDR), extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing and carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli in rescued sloth bears (Melursus ursinus). India Vet Res Commun. (2021) 45:163–70. doi: 10.1007/s11259-021-09794-3

6. Zeng, Z, Yang, J, Gu, J, Liu, Z, Hu, J, Li, X, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of CTX-M-type-producing Escherichia coli from a wildlife zoo in China. Vet Med Sci. (2022) 8:1294–9. doi: 10.1002/vms3.773

7. Peirano, G, and Pitout, JDD. Extended-Spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: update on molecular epidemiology and treatment options. Drugs. (2019) 79:1529–41. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01180-3

8. Andam, CP, Fournier, GP, and Gogarten, JP. Multilevel populations and the evolution of antibiotic resistance through horizontal gene transfer. FEMS Microbiol Rev. (2011) 35:756–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00274.x

9. Qin, Z, Hou, R, Lin, J, Gao, T, and Liu, S. Detection of plasomid-mediated β-lactams resistance genes in Escherchia coli isolates from feces of captive giant panda and their habitats. J China Agric Univ. (2018) 23:69–74. doi: 10.11841/j.issn.1007-4333.2018.03.09

10. Li, W, Zhou, C, Cheng, M, Tu, H, Wang, G, Mao, Y, et al. Large-scale genetic surveys for main extant population of wild giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) reveals an urgent need of human management. Evol Appl. (2023) 16:738–49. doi: 10.1111/eva.13532

11. Li, Y, Rao, T, Gai, L, Price, ML, Yuxin, L, and Jianghong, R. Giant pandas are losing their edge: population trend and distribution dynamic drivers of the giant panda. Glob Chang Biol. (2023) 29:4480–95. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16805

12. Dai, QL, Li, JW, Yang, Y, Li, M, Zhang, K, He, LY, et al. Genetic diversity and prediction analysis of small isolated Giant panda populations after release of individuals. Evol Bioinformatics Online. (2020) 16:1176934320939945. doi: 10.1177/1176934320939945

13. Kang, D, and Li, J. Role of nature reserves in giant panda protection. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2018) 25:4474–8. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0831-3

14. Ji, X, Liu, J, Liang, B, Sun, S, Zhu, L, Zhou, W, et al. Molecular characteristics of extended-Spectrum Beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from diseased captive Giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) in China. Microb Drug Resist. (2022) 28:750–7. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2021.0298

15. Fan, S, Jiang, S, Luo, L, Zhou, Z, Wang, L, Huang, X, et al. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli strains isolated from captive Giant pandas: a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence-associated genes. Vet Sci. (2022) 9:705. doi: 10.3390/vetsci9120705

16. Seghal Kiran, G, Anto Thomas, T, Selvin, J, Sabarathnam, B, and Lipton, AP. Optimization and characterization of a new lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by marine Brevibacterium aureum MSA13 in solid state culture. Bioresour Technol. (2010) 101:2389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.023

17. Zhu, Z, Jiang, S, Qi, M, Liu, H, Zhang, S, Liu, H, et al. Prevalence and characterization of antibiotic resistance genes and integrons in Escherichia coli isolates from captive non-human primates of 13 zoos in China. Sci Total Environ. (2021) 798:149268. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149268

18. Zhu, Z, Pan, S, Wei, B, Liu, H, Zhou, Z, Huang, X, et al. High prevalence of multi-drug resistances and diversity of mobile genetic elements in Escherichia coli isolates from captive giant pandas. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2020) 198:110681. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110681

19. Magiorakos, AP, Srinivasan, A, Carey, RB, Carmeli, Y, Falagas, ME, Giske, CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2012) 18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x

20. Carattoli, A, Bertini, A, Villa, L, Falbo, V, Hopkins, KL, and Threlfall, EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. (2005) 63:219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018

21. Clermont, O, Christenson, JK, Denamur, E, and Gordon, DM. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep. (2013) 5:58–65. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12019

22. Feil, EJ, Li, BC, Aanensen, DM, Hanage, WP, and Spratt, BG. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J Bacteriol. (2004) 186:1518–30. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1518-1530.2004

23. Francisco, AP, Bugalho, M, Ramirez, M, and Carriço, JA. Global optimal eBURST analysis of multilocus typing data using a graphic matroid approach. BMC Bioinformatics. (2009) 10:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-152

24. Feil, EJ, and Spratt, BG. Recombination and the population structures of bacterial pathogens. Ann Rev Microbiol. (2001) 55:561–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.561

25. Adler, A, Katz, DE, and Marchaim, D. The continuing plague of extended-Spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterbacterales infections: an update. Infect Dis Clin N Am. (2020) 34:677–708. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2020.06.003

26. Goncalves, A, Igrejas, G, Radhouani, H, Estepa, V, Alcaide, E, Zorrilla, I, et al. Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates in faecal samples of Iberian lynx. Lett Appl Microbiol. (2012) 54:73–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03173.x

27. Kumar, O, Singh, BR, Karikalan, M, Tamta, S, Jadia, JK, Sinha, DK, et al. Carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in captive blackbucks (Antilope cervicapra) and leopards (Panthera pardus) from India. Veterinarski Arhiv. (2021) 91:73–80. doi: 10.24099/VET.ARHIV.0829

28. Lerminiaux, NA, and Cameron, ADS. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in clinical environments. Can J Microbiol. (2019) 65:34–44. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2018-0275

29. de Carvalho, MPN, Fernandes, MR, Sellera, FP, Lopes, R, Monte, DF, Hippolito, AG, et al. International clones of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (CTX-M)-producing Escherichia coli in peri-urban wild animals, Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis. (2020) 67:1804–15. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13558

30. Osinska, M, Nowakiewicz, A, Zieba, P, Gnat, S, Lagowski, D, and Troscianczyk, A. Wildlife carnivorous mammals as a specific Mirror of environmental contamination with multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strains in Poland. Microb Drug Resist. (2020) 26:1120–31. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0480

31. Iwu, CD, Korsten, L, and Okoh, AI. The incidence of antibiotic resistance within and beyond the agricultural ecosystem: a concern for public health. Microbiology. (2020) 9:e1035. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1035

32. Osińska, M, Nowakiewicz, A, Zięba, P, Gnat, S, Łagowski, D, and Trościańczyk, A. A rich mosaic of resistance in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Poland as a potential effect of increasing synanthropization. Sci Total Environ. (2022) 818:151834. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151834

33. Castanheira, M, Simner, PJ, and Bradford, PA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC Antimicrob Resist. (2021) 3:dlab092. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlab092

34. Malik, F, Nawaz, M, Anjum, AA, Firyal, S, Shahid, MA, Irfan, S, et al. Molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance in poultry gut origin enterococci and horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance to Staphylococcus aureus. Pak Vet J. (2022) 42:383–9. doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2022.035

35. Telli, AE, Biçer, Y, Telli, N, Güngör, C, Türkal, G, and Ertaş Onmaz, N. Pathogenic Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. in chicken carcass rinses: isolation and genotyping by ERIC-PCR. Pak Vet J. (2022) 42:493–8. doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2022.049

36. Pungpian, C, Sinwat, N, Angkititrakul, S, Prathan, R, and Chuanchuen, R. Presence and transfer of antimicrobial resistance determinants in Escherichia coli in pigs, pork, and humans in Thailand and Lao PDR border provinces. Microb Drug Resist. (2021) 27:571–84. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0438

37. Shafiq, M, Huang, J, Shah, JM, Ali, I, Rahman, SU, and Wang, L. Characterization and resistant determinants linked to mobile elements of ESBL-producing and mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli recovered from the chicken origin. Microb Pathog. (2021) 150:104722. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104722

38. Shafiq, M, Rahman, SU, Bilal, H, Ullah, A, Noman, SM, Zeng, M, et al. Incidence and molecular characterization of ESBL-producing and colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates recovered from healthy food-producing animals in Pakistan. J Appl Microbiol. (2022) 133:1169–82. doi: 10.1111/jam.15469

39. Yang, QE, Sun, J, Li, L, Deng, H, Liu, BT, Fang, LX, et al. IncF plasmid diversity in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli strains from animals in China. Front Microbiol. (2015) 6:964. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00964

40. Ayad, A, Drissi, M, de Curraize, C, Dupont, C, Hartmann, A, Solanas, S, et al. Occurence of arm a and RmtB aminoglycoside resistance 16S rRNA Methylases in extended-Spectrum β-lactamases producing Escherichia coli in Algerian hospitals. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:1409. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01409

41. Kang, HY, Kim, J, Seol, SY, Lee, YC, Lee, JC, and Cho, DT. Characterization of conjugative plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance genes encoding 16S rRNA methylase, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, and/or plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase. J Microbiol. (2009) 47:68–75. doi: 10.1007/s12275-008-0158-3

42. Ma, L, Lin, CJ, Chen, JH, Fung, CP, Chang, FY, Lai, YK, et al. Widespread dissemination of aminoglycoside resistance genes armA and rmtB in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan producing CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2009) 53:104–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00852-08

43. Perez-Etayo, L, Gonzalez, D, and Vitas, AI. The aquatic ecosystem, a good environment for the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance and virulence-associated factors among extended Spectrum beta-lactamases Producing E. coli. Microorganisms. (2020) 8:568. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040568

44. Connell, I, Agace, W, Klemm, P, Schembri, M, Mărild, S, and Svanborg, C. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1996) 93:9827–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9827

45. Waksman, G, and Hultgren, SJ. Structural biology of the chaperone-usher pathway of pilus biogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2009) 7:765–74. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2220

46. Hritonenko, V, and Stathopoulos, C. Omptin proteins: an expanding family of outer membrane proteases in gram-negativeEnterobacteriaceae(review). Mol Membr Biol. (2009) 24:395–406. doi: 10.1080/09687680701443822

47. Nicolas-Chanoine, MH, Bertrand, X, and Madec, JY. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2014) 27:543–74. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00125-13

48. Liu, J, Du, SX, Zhang, JN, Liu, SH, Zhou, YY, and Wang, XR. Spreading of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli ST131 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 in patients with pneumonia: a molecular epidemiological study. Chin Med J. (2019) 132:1894–902. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000368

49. Seo, KW, and Lee, YJ. The occurrence of CTX-M-producing E. coli in the broiler parent stock in Korea. Poult Sci. (2021) 100:1008–15. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.09.005

50. Valizadeh, S, Yousefi, B, Abdolshahi, A, Emadi, A, and Eslami, M. Determination of genetic relationship between environmental Escherichia coli with PFGE and investigation of IS element in blaCTX-M gene of these isolates. Microb Pathog. (2021) 159:105154. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105154

51. Shala-Lawrence, A, Bragagnolo, N, Nowroozi-Dayeni, R, Kheyson, S, and Audette, GF. The interaction of TraW and TrbC is required to facilitate conjugation in F-like plasmids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2018) 503:2386–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.166

52. Dhaouadi, S, Soufi, L, Hamza, A, Fedida, D, Zied, C, Awadhi, E, et al. Co-occurrence of mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance and beta-lactamase-encoding genes in multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from broiler chickens with colibacillosis in Tunisia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. (2020) 22:538–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.03.017

53. Liu, FL, Kuan, NL, and Yeh, KS. Presence of the extended-Spectrum-beta-lactamase and plasmid-mediated AmpC-encoding genes in Escherichia coli from companion animals-a study from a university-based veterinary Hospital in Taipei. Taiwan Antibiotics (Basel). (2021) 10:1536. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10121536

54. Yang, H, Rehman, MU, Zhang, S, Yang, J, Li, Y, Gao, J, et al. High prevalence of CTX-M belonging to ST410 and ST889 among ESBL producing E. coli isolates from waterfowl birds in China's tropical island. Hainan Acta Trop. (2019) 194:30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.03.008

55. Manges, AR, Geum, HM, Guo, A, Edens, TJ, Fibke, CD, and Pitout, JDD. Global Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) lineages. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2019) 32:e00135-18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00135-18

56. Ewers, C, de Jong, A, Prenger-Berninghoff, E, El Garch, F, Leidner, U, Tiwari, SK, et al. Genomic diversity and virulence potential of ESBL-and AmpC-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli strains from healthy food animals across Europe. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:626774. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.626774

57. Schaufler, K, Semmler, T, Wieler, LH, Trott, DJ, Pitout, J, Peirano, G, et al. Genomic and functional analysis of emerging virulent and multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli lineage sequence type 648. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2019) 63:e00243-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00243-19

58. Norizuki, C, Kawamura, K, Wachino, JI, Suzuki, M, Nagano, N, Kondo, T, et al. Detection of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-1-group extended-Spectrum beta-lactamases from pigs in Aichi prefecture, Japan, between 2015 and 2016. Jpn J Infect Dis. (2018) 71:33–8. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2017.206

59. Seenama, C, Thamlikitkul, V, and Ratthawongjirakul, P. Multilocus sequence typing and Bla ESBL characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from healthy humans and swine in northern Thailand. Infect Drug Resist. (2019) 12:2201–14. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S209545

Keywords: Escherichia coli , extended-spectrum β-lactamase, antibiotic resistance gene, virulence-associated gen, horizontal gene transfer, giant panda

Citation: Liu H, Fan S, Zhang X, Yuan Y, Zhong W, Wang L, Wang C, Zhou Z, Zhang S, Geng Y, Peng G, Wang Y, Zhang K, Yan Q, Luo Y, Shi K and Zhong Z (2024) Antibiotic-resistant characteristics and horizontal gene transfer ability analysis of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolated from giant pandas. Front. Vet. Sci. 11:1394814. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1394814

Received: 02 March 2024; Accepted: 09 May 2024;

Published: 26 July 2024.

Edited by:

Gianmarco Ferrara, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyReviewed by:

Dong Chan Moon, Korea National Institute of Health, Republic of KoreaCopyright © 2024 Liu, Fan, Zhang, Yuan, Zhong, Wang, Wang, Zhou, Zhang, Geng, Peng, Wang, Zhang, Yan, Luo, Shi and Zhong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhijun Zhong, emhvbmd6aGlqdW40ODhAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Keyun Shi, c3RhZmY5NTVAeXhwaC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.