- 1Vascular Surgery Unit, Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy

- 2Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Rome “La Sapeinza”, Rome, Italy

Background: Mycotic carotid pseudoaneurysms represent a challenge for surgeons. They are rare and associated with high mortality and morbidity.

Methods: We reported a case of a 61-year-old man with a mycotic pseudoaneurysm of carotid bifurcation. The case was managed by a staged procedure, starting with initial endovascular control using a stent graft, followed by open arterial reconstruction using a saphenous vein graft.

Results: The patient was discharged home with a patent carotid artery and no sign of infection or bleeding. A computed tomography scan performed at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year later confirmed good patency of the graft without imaging of cerebral ischemia.

Conclusions: Mycotic pseudoaneurysms of the extracranial carotid artery are rare and should always be treated surgically. This disease, despite its rarity, requires early detection and treatment to avoid fatal outcomes. A hybrid staged approach is suggested, compared to one-staged surgery, to avoid rupture and improve clinical outcomes. This approach involves using a stent graft combined with antibiotic therapy as bridge treatment until definitive surgery can be performed to enable arterial reconstruction with an autologous graft.

Introduction

Mycotic aneurysms of the extracranial carotid artery are relatively rare, with only a small number of cases reported in the literature (1, 2); despite their rarity, they pose a significant threat to patient health and wellbeing. These aneurysms are associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity (3) and can lead to serious complications such as rupture and metastatic brain abscesses (1).

The clinical presentation of these aneurysms is characterized by a growing and pulsatile cervical lump, often accompanied by pain, tenderness, fever, hoarseness of voice (dysphonia), and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) (4, 5). The condition is characterized by unspecific symptoms making preoperative diagnosis very challenging, especially when no risk factors are reported (6). A definitive diagnosis hinges on identifying a microbial pathogen within a tissue sample, which is typically bacterial (5), despite the term “mycotic” implying a fungal origin (6). The treatment of these patients represents a challenge for surgeons. The preferred treatment option is the surgical removal of the aneurysm, followed by the reconstruction of the damaged artery, typically using an autologous conduit in a one-staged approach. The use of stent grafts can be useful to avoid the imminent risk of pseudoaneurysm rupture; however, an exclusively endovascular approach to treating infected aneurysms is a subject of ongoing debate, given limited research on their long-term efficacy (7). A hybrid endovascular and surgical staged repair initially gives an opportunity to successfully manage the acute pseudoaneurysm with endovascular covered stents. This approach also allows the clinicians to administer some days of antibiotic therapy, thereby reducing the surgical risk and improving the surgical outcome by preventing delayed complications (8, 9).

The aim of our case report is to describe the successful treatment of a mycotic pseudoaneurysm of carotid bifurcation with a staged hybrid approach and review the specific existing literature. According to our experience, a multistep hybrid procedure, using an endovascular approach for initial control followed by definitive surgery, should be considered useful and effective for this rare pathology compared to one-staged surgery, especially in an emergency setting.

Methods

Since this case report utilized anonymized data, informed consent was not necessary.

In February 2024, an online search was conducted in the Medline and Embase databases using specific MeSH terminology (Carotid Mycotic Pseudoaneurysm, Aneurysm, Adult).

Case report

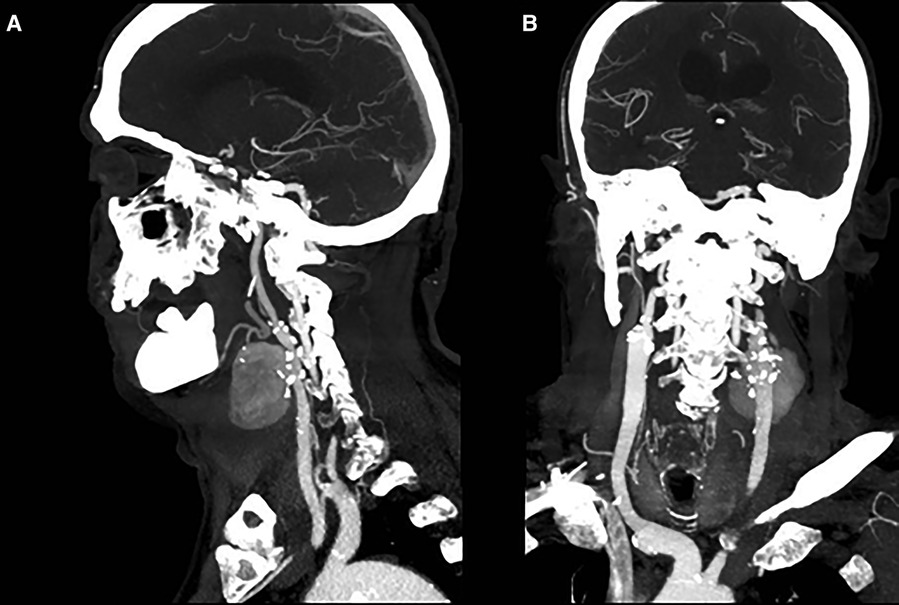

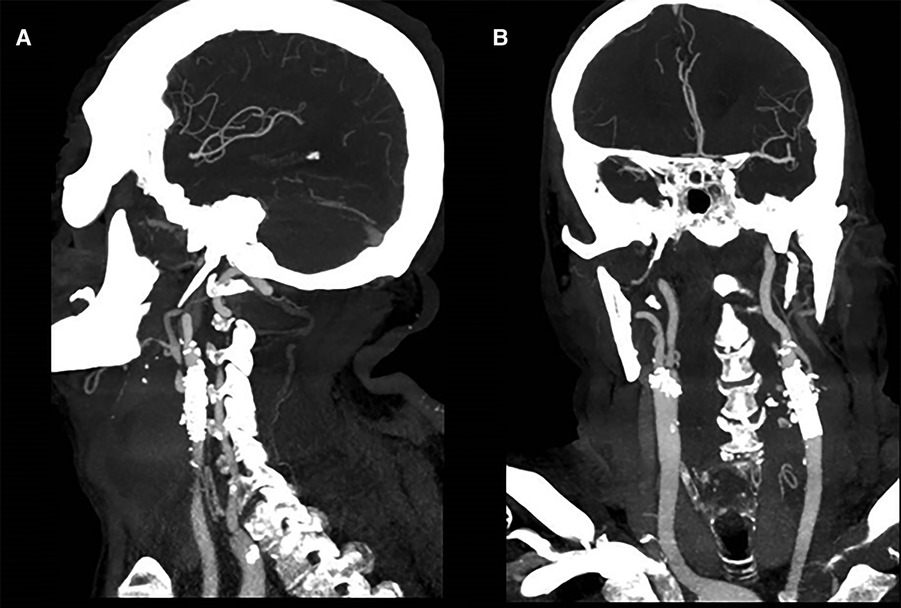

A 61-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to the Emergency Care unit of our hospital after left cervical swelling appeared for the last 10 days without dysphagia or neurological deficits. He had a history of hypertension, smoking addiction (now ceased), diabetes, and atrial fibrillation. The patient denied any prior neck or oral surgery. Vital signs were stable, with a normal body temperature of 36°C. Physical examination revealed a pulsatile, firm, and painless mass in the left anterior neck, just above the clavicle. The overlying skin appeared normal and not reddened. No neurological focal signs of central or peripheral origin were present. However, there was a huge dorsal abscess, which was immediately opened and drained (Figure 1). The abscess wall was submitted for culture and tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus. Blood tests demonstrated leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 22.53 × 103/μl. Transthoracic echocardiogram was negative for endocarditis. Based on clinical findings and imaging studies, our diagnosis was a mycotic pseudoaneurysm (Figures 2A, B). Following the recommendation of our infectious consultant, the patient was promptly initiated on antibiotic therapy with Tazocin (Pfizer, Italy) die 4.5 mg thrice; serial hemocultures were made but were negative. Surgical resection and revascularization with autologous material were mandatory. To reduce the surgical risk, the patient was first sent to radiology. He was taken to the interventional radiology suite for an endovascular exclusion using an 8 mm × 38 mm Advantia (Atrium medical corporation, Gentinge Australia Pty Ltd) balloon-expandable covered stent that was deployed across the healthy segment of the common carotid artery (CCA) proximally and the internal carotid artery (ICA) distally (Figures 3A,B), without embolization of the external carotid artery. A loading dose of aspirin and clopidogrel was administrated before the deployment of the stent graft.

Figure 1 Huge dorsal abscess opened and drained with the microbiological examination positive for Staphylococcus aureus.

Figure 2 (A,B) CT scan in LL and AP projection showing a 48-mm × 38-mm pseudoaneurysm of the left carotid bifurcation without any cerebral embolic signs. LL, laterolateral; AP, anteroposterior.

Figure 3 (A,B) CT control in AP and LL projection after endovascular exclusion of the mycotic pseudoaneurysm using a stent graft. LL, laterolateral; AP, anteroposterior.

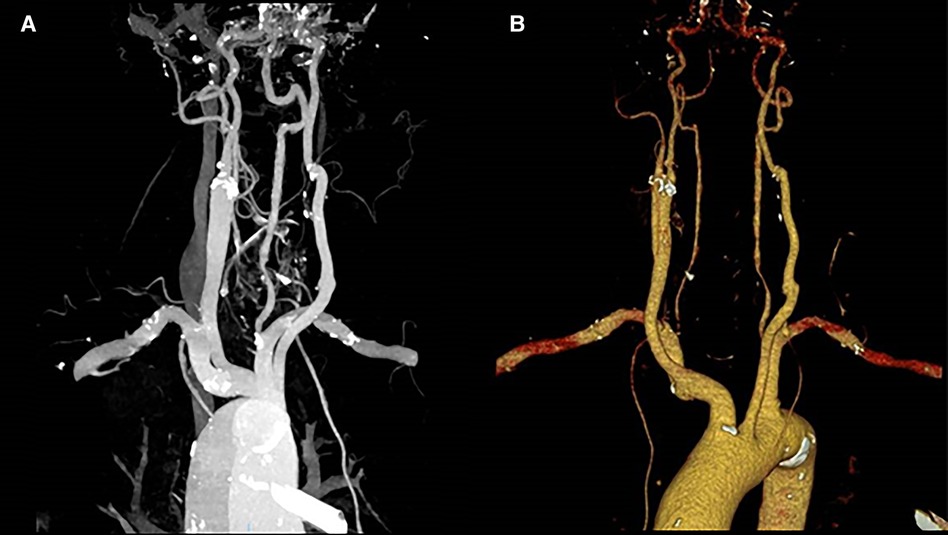

One week later, the patient received general anesthesia for the procedure. Cerebral perfusion was monitored by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and maintained using a Sundt shunt. A standard surgical approach was employed, involving an incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. We achieved control of internal, external, and common carotid arteries and dissected the pseudoaneurysm. Then, we clamped, respectively, the common, internal, and external carotid arteries. The pseudoaneurysm sac was opened, the previously placed stent graft was extracted, and the surrounding inflammatory tissue was debrided (Figure 4A). A specimen of the pseudoaneurysm wall was obtained and submitted for microbiological analysis (positive for S. aureus). The external carotid artery was ligated. After obtaining proximal and distal control, a large portion of the infected carotid artery, including the stent, was surgically removed, and cerebral perfusion was maintained using a Sundt shunt (Figures 4B,C). The shunt was initially inserted into the proximal and distal stumps of the carotid artery and then through the venous graft after the first anastomosis. The resected segment was replaced with a similarly sized section of the great saphenous vein (Figure 4D). The postoperative period was uneventful, with no neurological complications. Following antibiotic therapy with teicoplanin and doxycycline, the patient's white blood cell count and all inflammatory markers normalized; he was discharged after 12 days from surgery and continued antibiotic therapy (doxycycline 100 mg twice daily) for another 3 weeks, with daily aspirin 100 mg prescribed on a lifelong schedule. Follow-up computed tomography (CT) scans at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year demonstrated patency of the graft (Figures 5A,B) with no signs of cerebral ischemia.

Figure 4 (A) Intraoperative image showing the pseudoaneurysm sac opened. (B) Intraoperative image showing stent graft removal. (C) Intraoperative image showing the Sundt shunt for cerebral perfusion. (D) Open surgical carotid artery reconstruction using the great saphenous vein graft.

Figure 5 (A,B) 1-year CT scan showing good patency of the graft without imaging of cerebral ischemia.

Discussion

Although uncommon, mycotic extracranial carotid pseudoaneurysms can develop as a complication of local or systemic infections, including dental suppuration, bacterial sinusitis, Lemierre's syndrome, bacterial endocarditis, and bacteremia (7, 10). A primary infection can cause a carotid pseudoaneurysm and then lead to perforation and an abscess. However, some researchers propose that the abscess might be the initial lesion that subsequently breaches the arterial wall. In addition, other local inflammatory conditions affecting blood vessels, such as vasculitis or hereditary dysfunctions, could potentially weaken the arterial wall and increase susceptibility to infection (11). Although trauma is the most frequent cause of aneurysms in general (42%), the source of infection in mycotic aneurysms often remains unidentified (25%) (12). In our patient's case, despite good overall health aside from the dorsal abscess, the specific origin of the infection remained unclear. The most common bacterial pathogens associated with mycotic carotid aneurysms are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Salmonella (4).

Nowadays, the primary treatment for mycotic pseudoaneurysms involves a combination of long-term, broad-spectrum systemic antibiotics to eradicate the infection and surgical intervention to remove the infected tissue and reconstruct the affected blood vessel. Surgical management typically involves excision of the pseudoaneurysm, debridement of the infected tissues, and restoration of arterial continuity using different techniques such as primary closure, patch angioplasty, bypass, and resection with primary anastomosis, which can lead to complications such as thrombosis, embolization, and rupture. Although various graft materials such as autologous veins, synthetic options such as prostheses impregnated with silver salts, and cryopreserved allografts exist for reconstruction, the potential for long-term complications due to infection must be considered. These complications can include stenosis, a narrowing of the graft, or dilatation, an abnormal widening. Autologous tissues such as the superficial femoral artery, the hypogastric artery, and the saphenous vein are currently considered the preferred material for vascular reconstruction because of their resistance to infection and their immediate availability (13–15).

Open surgery in an acute setting is generally associated with poor outcomes, including stroke and mortality of up to 50% of patients if the carotid artery is ligated. This intervention carries a mortality risk of 25%–60% with a high incidence of stroke, so it is suggested that this procedure be performed with an intact circle of Willis. In emergencies, a synthetic prosthesis is often used to reconstruct the carotid artery because there is not enough time to evaluate and prepare a vein graft, and cryopreserved arterial allografts are not available in the institute (16). Endovascular repair using a covered stent has been described as a “bridge” solution, often in emergent settings, before early definitive surgical management (17–19), or in high-risk patients who are not candidates for open surgery (7). Endovascular repair using coils offers a valuable temporary alternative for treating patients with pseudoaneurysms presenting to emergency care with carotid blowout syndrome (20, 21). However, its usefulness is limited by the potential risks of placing prosthetic material (coils) in an already infected area. Another treatment option is the sacrifice of the carotid axis through embolization with coils, preceded by an angiographic occlusion test to verify intracranial compensation.

In our situation, to mitigate the risk of septic emboli and rupture during surgery, we opted for administering endovascular bridge therapy to the patient. This involved utilizing a covered stent graft in conjunction with antibiotic treatment prior to proceeding with the surgical intervention until a reduction in the volume of the mass in the neck was evident.

However, the major advantage of using a covered stent as bridge therapy is the administration of antibiotic therapy for a sufficient time before definitive surgery. Antimicrobial drugs strongly improve clinical outcomes, minimizing the risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic complications (i.e., septic emboli) originating from the pseudoaneurysm while waiting for surgery.

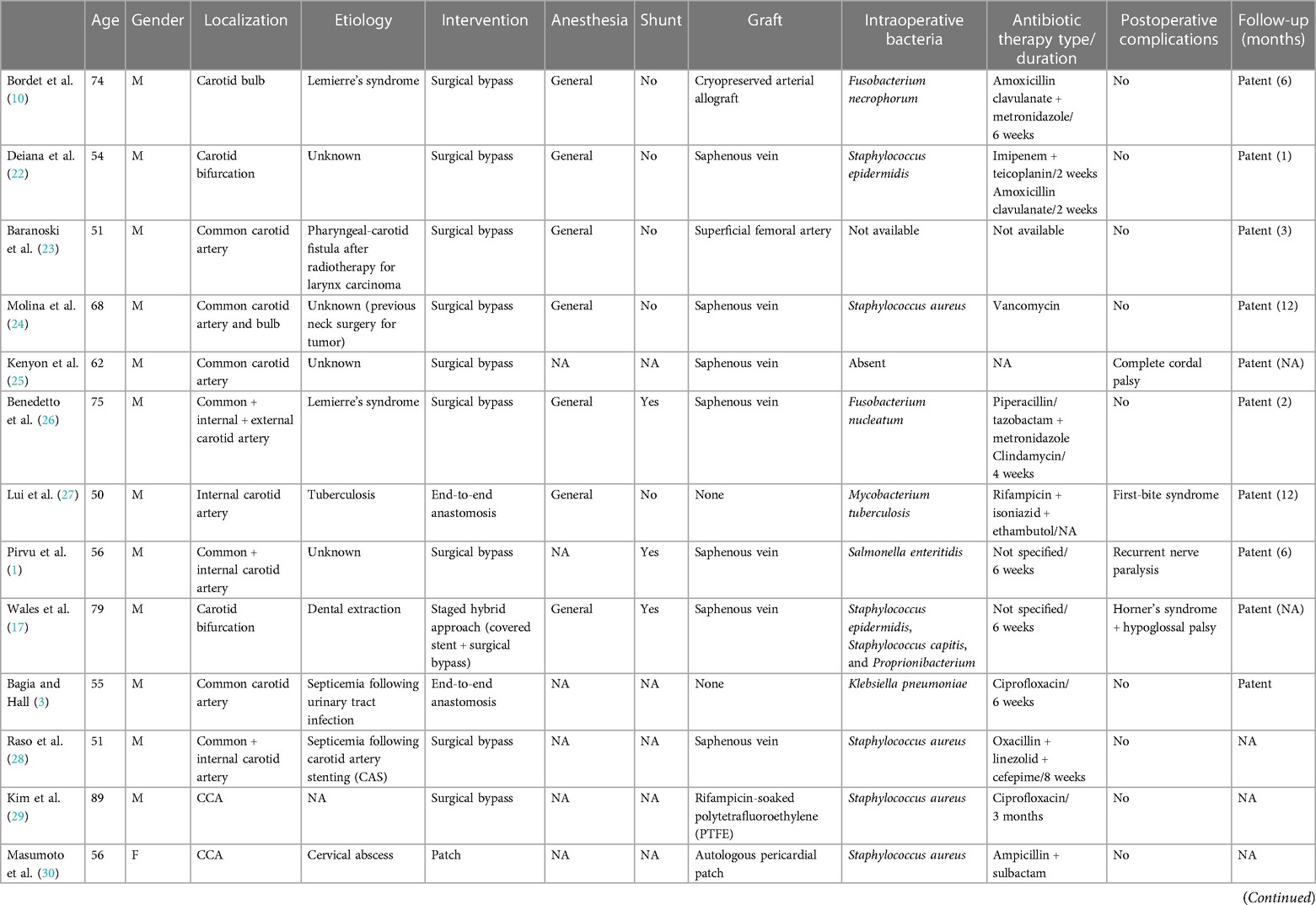

We hold the opinion that employing endovascular stent graft placement as the primary treatment approach is optimal for preventing rupture and managing hemorrhage in patients diagnosed with carotid blowout syndrome. However, in cases where patients have realistic prospects for long-term survival, reconstruction should also be deliberated upon (19). In our view, stent placement should be succeeded by definitive reconstruction to minimize both the mortality and morbidity risks associated with thrombosis, re-bleeding, infection, and the necessity for carotid ligation or embolization. The hybrid treatment of mycotic carotid pseudoaneurysms has been scarcely reported in the literature, with follow-up limited to mid-term. We performed a literature review on mycotic common and internal carotid aneurysms, which revealed 18 papers reporting successful surgical treatment in adult patients for this disease (Table 1). Eighteen patients (16 males, 2 females; mean age = 64.9 years old) were treated for mycotic carotid pseudoaneurysms—carotid bifurcation (50%), CCA (39%), and ICA (11%). The preferred approach was surgical treatment in 83% of the cases, and aneurysms were excluded by a surgical bypass in 61% of the cases using prevalently saphenous vein graft (55%), end-to-end anastomosis in 11%, and patch in the latter 11%. An endovascular approach was used in 12% of the cases (one case involving embolization and one involving endovascular repair using a covered stent). A hybrid staged approach was described only once in the literature for a 79-year-old man with a mycotic pseudoaneurysm involving carotid bifurcation that developed after a dental extraction. The reported technical success rate (TS) was 100%. The mean of postoperative follow-up, considering the time available in the literature and not reported for all the cases, was 6.7 months (range 1–12 months). This revealed vessel patency in 12 patients; for six patients, the follow-up result was not reported. Postoperative complications were fundamentally neurological (cordal palsy and recurrent, hypoglossal, and facial palsy). Our case confirms that carotid bifurcation is the most frequent site involved in pseudoaneurysm degeneration of the extracranial carotid axis, that patients usually present in stable hemodynamic condition, and that the hybrid staged approach represents a valid option for treating mycotic extracranial carotid pseudoaneurysms. At present, surgical management of a mycotic pseudoaneurysm invariably involves prolonged antibiotic treatment, initiated preoperatively and guided by culture results (5). Following surgery, antibiotic therapy is typically recommended for a minimum of 6 weeks, with certain authors advocating for continuation up to 6 months.

Table 1 Mycotic extracranial common or internal carotid pseudoaneurysm in the survived adult patient using full-text English articles.

Conclusions

Mycotic pseudoaneurysms of the extracranial carotid artery are rare but present with a wide spectrum of symptoms. This disease, despite its rarity, requires early detection and treatment to avoid fatal outcomes. Frequently, the precise origin of the infection remains elusive. Treatment involves aneurysmectomy combined with antibiotic therapy, with the preferred approach being the restoration of arterial continuity using an autologous graft.

The utilization of a stent graft as a definitive solution remains controversial but is suggested as bridge therapy before definitive surgical treatment in urgent settings to avoid rupture, giving the possibility to administer preoperative antibiotic therapy for a sufficient period, which strongly improves clinical outcomes by minimizing the risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic complications.

A hybrid staged approach is useful and effective compared to one-staged surgery to avoid rupture and improve clinical outcomes using a stent graft and antibiotic therapy before definitive surgery and then achieve arterial reconstruction with an autologous graft.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FI: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation. PT: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. PA: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. FG: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. TM: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation. RV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NP: Writing – review & editing. PP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. IG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. DV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. RC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Pirvu A, Bouchet C, Garibotti FM, Haupert S, Sessa C. Mycotic aneurysm of the internal carotid artery. Ann Vasc Surg. (2013) 27(6):826–30. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2012.10.025

2. Kasangana K, Shih M, Saunders P, Rhee R. Common carotid artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to Mycobacterium tuberculosis treated with resection and reconstruction with saphenous vein graft. J Vasc Sur Cases Innov Tech. (2017) 3(3):192–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvscit.2017.06.006

3. Bagia JS, Hall R. Extracranial mycotic carotid pseudoaneurysm. ANZ J Surg. (2003) 73(11):970–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2002.02538.x

4. Rhodes EL, Stanley JC, Hoffman GL, Cronenwett JL, Fry WJ. Aneurysms of extracranial carotid arteries. Arch Surg. (1976) 111(4):339–43. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1976.01360220035006

5. Fankhauser GT, Stone WM, Fowl RJ, O'Donnell ME, Bower TC, Meyer FB, et al. Surgical and medical management of extracranial carotid artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. (2015) 61(2):389–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.07.092

6. Garg K, Rockman CB, Lee V, Maldonado TS, Jacobowitz GR, Adelman MA, et al. Presentation and management of carotid artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. (2012) 55(6):1618–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.054

7. Riga C, Bicknell C, Jindal R, Cheshire N, Hamady M. Endovascular stenting of peripheral infected aneurysms: a temporary measure or a definitive solution in high-risk patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. (2008) 31(6):1228–35. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9372-y

8. McCready RA, Divelbiss JL, Bryant MA, Denardo AJ, Scott JA. Endoluminal repair of carotid artery pseudoaneurysms: a word of caution. J Vasc Surg. (2008) 40(5):1020–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.034

9. Simmental A, Johnson JT, Horowitz M. Delayed complications of endovascular stenting for carotid blowout. Am J Otol. (2003) 24(6):417–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00088-7

10. Bordet M, Long A, Tresson P. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of carotid artery as a rare complication of Lemierre syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. (2021) 96(12):3178–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.10.006

11. Papadoulas S, Zampakis P, Liamis A, Dimopoulos PA, Tsolakis IA. Mycotic aneurysm of the internal carotid artery presenting with multiple cerebral septic emboli. Vascular. (2007) 15:215–20. doi: 10.2310/6670.2007.00043

12. O’Connell JB, Darcy S, Reil T. Extra-cranial internal carotid artery mycotic aneurysm: case report and review. Vasc Endovascular Surg. (2009) 43:410–5. doi: 10.1177/1538574409340590

13. Sessa CN, Morasch MD, Berguer R, Kline RA, Jacobs JR, Arden RL. Carotid resection and replacement with autogenous arterial graft during operation for neck malignancy. Ann Vasc Surg. (1998) 12:229–35. doi: 10.1007/s100169900145

14. Lozano FS, Munoz A, Gomez JL, Barros MB. The autologous superficial femoral artery as a substitute for the carotid axis in oncologic surgery. Three new cases and a review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). (2008) 49:653–7.18670383

15. Jacobs JR, Arden RL, Marks SC, Kline R, Berguer R. Carotid artery reconstruction using superficial femoral arterial grafts. Laryngoscope. (1994) 104:689–93. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199406000-00008

16. Lueg EA, Awerbuck D, Forte V. Ligation of the common carotid artery for the management of a mycotic pseudoaneurysm of an extracranial internal carotid artery. A case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (1995) 33(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01185-e

17. Wales L, Kruger AJ, Jenkins JS, Mitchell K, Boyne NS, Walker PJ. Mycotic carotid pseudoaneurysm: staged endovascular and surgical repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2010) 39(1):23–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.10.012

18. Mazzaccaro D, Stegher S, Occhiuto MT, Malacrida G, Righini P, Tealdi DG, et al. Hybrid endovascular and surgical approach for mycotic pseudoaneurysms of the extracranial internal carotid artery. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. (2014) 2:2050313X1455808. doi: 10.1177/2050313X14558081

19. Sallustro M, Abualhin M, Faggioli G, Pilato A, Dall'Olio D, Simonetti L, et al. Multistep and multidisciplinary management for post-irradiated carotid blowout syndrome in a young patient with oropharyngeal carcinoma: a case report. Ann Vasc Surg. (2020) 67(565):565.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.02.023

20. Wilseck Z, Savastano L, Chaudhary N, Pandey AS, Griauzde J, Sankaran S, et al. Delayed extrusion of embolic coils into the airway after embolization of an external carotid artery pseudoaneurysm. J Neurointerv Surg. (2018) 10(7):e18. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013178.rep

21. Sánchez-Canteli M, Rodrigo JP, Quintana EM, Vega P, Llorente JL, López F. Embolization for carotid blowout in head and neck cancer: case report of five patients. Vasc Endovascular Surg. (2022) 56(1):53–7. doi: 10.1177/15385744211027030

22. Deiana G, Baule A, Georgiev GG, Moro M, Spanu F, Urru F, et al. Hybrid solution for mycotic pseudoaneurysm of carotid bifurcation. Case Rep Vasc Med. (2020) 2020:8815524. doi: 10.1155/2020/8815524

23. Baranoski JF, Wanebo JE, Heiland KE, Zabramski JM. Superficial femoral artery interposition graft for repair of a ruptured mycotic common carotid artery pseudoaneurysm: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. (2019) 129:130–2. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.215

24. Molina G, Mesías C, Calispa J, Arroyo K, Jaramillo K, Lluglla L, et al. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the extracranial carotid artery, a severe and rare disease, a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. (2020) 71:382–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.03.032

25. Kenyon O, Tanna R, Sharma V, Kullar P. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the common carotid artery: an unusual neck lump. BMJ Case Rep. (2020) 13(11):e239921. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239921

26. Benedetto F, Barillà D, Pipitò N, Derone G, Cutrupi A, Barillà C. Mycotic pseudoaneurysm of internal carotid artery secondary to Lemierre’s syndrome, how to do it. Ann Vasc Surg. (2017) 44(423):423.e13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.05.026

27. Lui DH, Patel S, Khurram R, Joffe M, Constantinou J, Baker D. Mycotic internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. (2022) 8(2):251–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvscit.2022.02.012

28. Raso J, Darwich R, Ornellas C, Cariri G. Cervical carotid pseudoaneurysm: a carotid artery stenting complication. Surg Neurol Int. (2011) 2:86. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.82328

29. Kim DI, Park BS, Kim DH, Kim DJ, Jung YJ, Lee SS, et al. Ruptured mycotic aneurysm of the common carotid artery: a case report. Vasc Specialist Int. (2018) 34(2):48–50. doi: 10.5758/vsi.2018.34.2.48

30. Masumoto H, Shimamoto M, Yamazaki F, Nakai M, Fujita S, Miura Y. Airway stenosis associated with a mycotic pseudoaneurysm of the common carotid artery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2008) 56(5):242–5. doi: 10.1007/s11748-008-0230-2

31. Kaviani A, Ouriel K, Kashyap VS. Infected carotid pseudoaneurysm and carotid-cutaneous fistula as a late complication of carotid artery stenting. J Vasc Surg. (2006) 43(2):379–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.10.058

32. Grazziotin MU, Strother CM, Turnipseed WD. Mycotic carotid artery pseudoaneurysm following stenting—a case report and lessons learned. Vasc Endovascular Surg. (2002) 36(5):397–401. doi: 10.1177/153857440203600512

Keywords: mycotic, carotid, pseudoaneurysm, graft, stentgraft, vein, extracranial, hybrid

Citation: Marianna S, Ilaria F, Teresa P, Armando P, Giuseppe F, Marisole T, Valerio R, Priscilla N, Palumbo P, Giulio I, Vito D’Andrea and Carlo R (2024) Hybrid endovascular and surgical staged approach for mycotic carotid pseudoaneurysms: a case report and literature review. Front. Surg. 11:1394441. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2024.1394441

Received: 1 March 2024; Accepted: 17 June 2024;

Published: 9 July 2024.

Edited by:

Raffaele Serra, Magna Græcia University, ItalyReviewed by:

Roberto Minici, Magna Graecia University, ItalyGeorge Galyfos, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

© 2024 Marianna, Ilaria, Teresa, Armando, Giuseppe, Marisole, Valerio, Priscilla, Palumbo, Giulio, Vito and Carlo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sallustro Marianna, bWFyaWFubmEuc2FsbHVzdHJvQHZpcmdpbGlvLml0; Nardi Priscilla, cHJpc2NpbGxhLm5hcmRpQHVuaXJvbWExLml0; Illuminati Giulio, Z2l1bGlvLmlsbHVtaW5hdGlAdW5pcm9tYTEuaXQ=

Sallustro Marianna1*

Sallustro Marianna1* Nardi Priscilla

Nardi Priscilla Piergaspare Palumbo

Piergaspare Palumbo Illuminati Giulio

Illuminati Giulio D’Andrea Vito

D’Andrea Vito