- 11st Propedeutic Department of Surgery, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, AHEPA University Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 2Pathology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

- 33rd Laboratory of Nuclear Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Introduction: Composite paragangliomas consist of two components, paraganglioma and ganglioneuroma, representing a rare subgroup of paragangliomas. The purpose of the study is to describe a case of composite paraganglioma of the celiac trunk and a brief review of the existing literature.

Case Presentation: A 64-year-old female patient with a history of epigastric abdominal pain and a 51 mm-diameter tumor found in a Computerized Tomography of the abdomen was admitted to our surgical department for further evaluation and treatment. After a brief preoperative surgical assessment, the patient underwent a mini-laparotomy for the excision of this tumor. After having the results of the pathology report, a comprehensive review of the international literature was carried out by applying the appropriate search terms.

Results: As it was found intraoperatively, the tumor was located at the cephalad aspect of the common hepatic artery, over the portal vein and the inferior vena cava. A negative-margin resection was achieved and the tumor was sent for pathology analysis. The final pathology report revealed a composite paraganglioma, with α paraganglioma and a ganglioneuroma component. Seventeen cases of extra-adrenal composite paraganglioma have been reported in the international literature so far. This case was the first one found in the area of the celiac trunk.

Conclusions: Composite paragangliomas comprise rare and potentially malignant tumors with variable prognosis. Establishing their diagnosis promptly is of vital significance. Due to the first-described location of the composite paraganglioma in our case, the differential diagnosis of tumors in this area should also include composite paragangliomas.

Introduction

Pheochromocytomas are rare chromaffin catecholamine-secreting tumors, usually located within the adrenal glands. However, when these tumors arise outside of the adrenal glands, they are defined as paragangliomas. Paragangliomas may occur anywhere along the path of the autonomic ganglia, from the base of the skull to the urinary bladder. Composite paragangliomas, a subtype of paragangliomas, usually consist of the paraganglioma and the ganglioneuroma component. Composite paragangliomas are estimated to be around 3% of the adrenal paragangliomas, being very rare especially outside the adrenal glands (1). They are reported to be found usually in the adrenal glands and less frequently in the mediastinum, in the Zuckerkandl organ at the abdominal aortic bifurcation, in the retroperitoneum, in the urinary bladder, and the central nervous system (2, 3). Herein, we present a case of composite paraganglioma located on the right of the celiac trunk, over the common hepatic artery.

Case Presentation

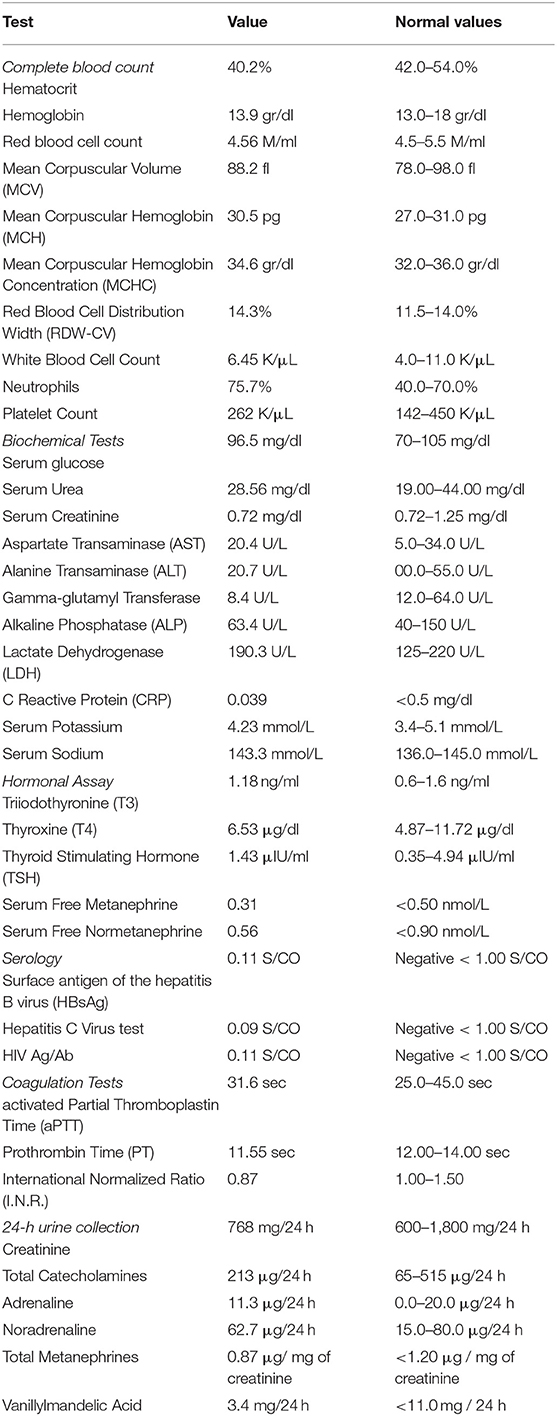

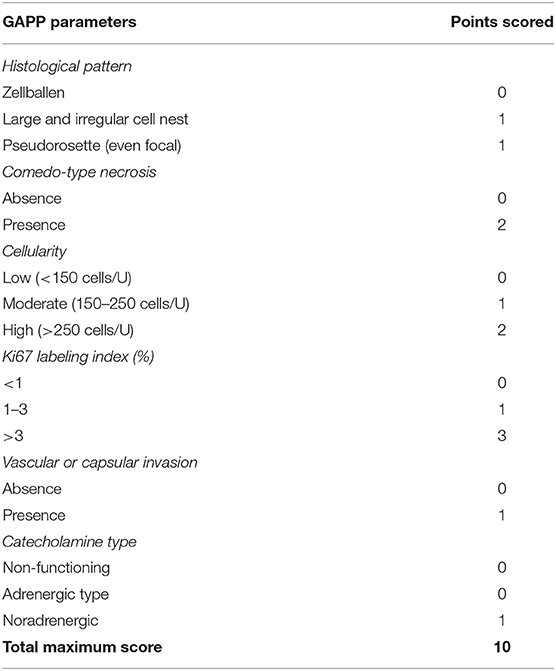

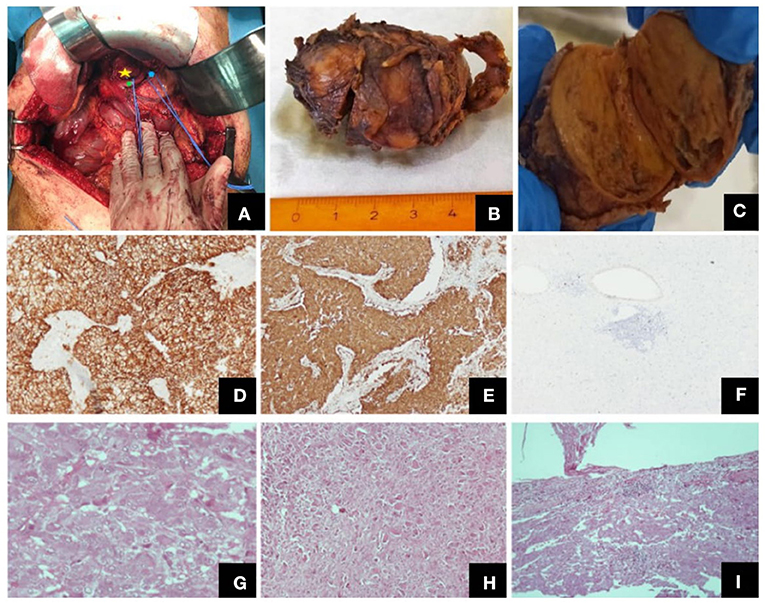

A 64-year-old female patient was referred to our outpatient department for surgical evaluation due to paroxysmal epigastric abdominal pain, with mild deterioration after movement and exercise. The patient's medical history referred that she underwent total thyroidectomy, with central and left lateral compartment dissection due to thyroid papillary cancer with nodal metastasis (pT3b(m)N1Mx based on The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging) one year before her admission to our clinic. Moreover, she had already visited a Gastroenterologist, who suggested her undergoing endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) system and a Computerized Tomography (CT) scan. The report of the upper GI endoscopy referred that mild esophagitis and gastritis were present while the CT scan revealed a 51 mm-diameter solid mass at the site of hepatogastric ligament applying pressure on the abdominal aorta. Our findings during the initial physical examination and laboratory test were normal (Table 1). Next, to identify the nature of this mass, we suggested that she should undergo an endoscopic ultrasound during which biopsies from the bulging mass would be received and sent for pathology and immunohistochemical analysis. The differential diagnosis of pathology report suggested a ganglioneuroma or a neuroendocrine neoplasm and the further immunohistochemical analysis reported that the mass included neoplasmatic cells being positive to S100 protein and also cells with positive immunostaining for neurofibers (NF), two findings which both were indicative of ganglioneuroma. Under the probable diagnosis of a ganglioneuroma, we decided to evaluate its activity regarding the secretion of catecholamines or other neurotransmitters. As a result, an analysis for creatinine, total catecholamines, metanephrines, and vanillylmandelic acid of a 24-h urine collection was performed, without revealing any abnormality (Table 1). In addition, the patient underwent screening for mutations in the ret proto-oncogene from the patient's genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) for any genetic disorders to be found, which did not detect any mutation in exons 5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 16. Moreover, it was of great importance, a more comprehensive radiological assessment to be held, due to mass' special location. Thus, the patient underwent chest CT scan and abdominal CT Angiography scan with 3D reconstruction of the celiac trunk which reported again the known tumor of about 51 mm diameter, located between the aorta and the inferior vena cava in the hepatogastric space. Based on all the before mentioned data, we decided, after consensus, to suggest the patient undergoing surgical excision of the tumor due to its potential for malignancy. The patient's decision was congruent with our suggestion and she underwent a laparotomy and surgical excision of the mass. Intraoperatively, the tumor was found at the cephalad aspect of the common hepatic artery, over the portal vein, and the inferior vena cava. A negative-margin resection was achieved and the tumor was sent for pathology analysis. In addition, all the nodal tissue around the celiac trunk was excised after skeletonizing the vessels (Figure 1). The postoperative period was uncomplicated and the patient was discharged the 2nd postoperative day. The final pathology report revealed that the tumor included two masses, a sub round one enveloped by capsule and sized 6.0 × 4.2 × 3.7 cm, and a second smaller one attached to the first's outer surface. It was presented with neoplastic features and consisted of large, irregularly shaped cells. The number of nuclei was >5/10 per visual field, while in some areas they formed “zellballen balls,” and the cytoviscosity was considered as moderate to maximum. In addition, in some areas the ganglion cell population did not mix with the upper cellular findings, but appeared to be of neurogenic origin, as evidenced by immunohistochemical staining for protein S100 and CD56. Furthermore, in some areas a capsule was identified, and it was disrupted by the neoplastic cells. In these areas, neoplasmatic embolisms were identified inside the thin-walled vessels. However, the wall of the vessels was not found to be positive for immunohistochemical staining regarding CD34 and D2-40. Moreover, the neoplasmatic cells were positive for CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin and their nuclei presented also positive for ATRX staining, while p53 protein was identified only in <5% of them. However, the cells were negative for neurofibrins, inhibin, Melan A and HMB-45. In conclusion, the superior morphological and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with a composite paraganglioma and to a small limited extent, a ganglioneuroma. In addition, the particular histological features of the paraganglioma (diffuse growth, capsular and vascular infiltration, Ki67 cell proliferation index >2%, tumor size >5 cm) classify the neoplasm as a high metastatic potential one, according to the GAPP classification system. Two months after the procedure, the subsequent imaging evaluation of the patient, with chest and abdominal CT scan and ultrasound of the upper abdomen, did not reveal any pathological findings, except for a new-described small cyst at the head of the pancreas possibly due to chronic pancreatic inflammation. The laboratory tests were normal as well.

Figure 1. Different views of the tumor (intraoperatively, macroscopically after excision) and its histological features. (A) Intraoperative view of the tumor (yellow star: the tumor, green point: common hepatic artery, blue point: left gastric artery), (B) Macroscopic view of the excised tumor, (C) Tumor on vertical cross-section, where both the paraganglioma and the ganglioneuroma components were identified, Representative images of histological features: (D) CD56, ×100, (E) synapt (×100), (F) Ki67 labeling index (×40), (G) paraganglioma, H + E, (×400), (H) ganglioneuroma, H + E, (×100), (I) tumor invasion of the capsule, H + E, (×100).

Discussion

Pheochromocytomas are tumors which in their majority originate from the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla (85–90%) and less frequently from the extra-adrenal sympathetic nerve tissue, mainly paraspinal or paraaortic, called paragangliomas (4). They can be either sporadic or familial (5). The usual location for paragangliomas is primarily in the head, the cervix, or the mediastinum (6), usually secreting catecholamines. Similar to common paragangliomas, the composite paragangliomas are primarily functional, secreting catecholamines such as adrenaline, noradrenaline, and dopamine or corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) as well (7). Based on this fact, common symptoms are severe headache, nausea, palpitations, sweating, fatigue, permanent or paroxysmal hypertension, or even orthostatic hypotension. Moreover, pallor, redness of the face, weight loss, and hyperglycemia are common signs as well (8). However, in our case, since the composite paraganglioma was not an active one, the patient did not experience any of the relating with catecholamines-secretion symptoms, but only a feeling of abdominal tenderness and pain especially right after exercise.

Ten percent of all the pheochromocytomas have a chance of malignancy, with extra-adrenal gland localization advocating a particularly high rate of malignancy and metastatic disease (9). On the other hand, ganglioneuromas are considered to be the most common form of neuroblastoma, mainly in young adults (10). They are primarily retroperitoneal and tend to be asymptomatic until they become large enough to give symptoms by pressing nearby structures (11). However, some ganglioneuromas may be also functional and secrete peptides, such as VIP and somatostatin, causing diarrhea, hypertension, and sweating.

Regarding composite paragangliomas, they are considered to be rare tumors. In about 70% of them, paraganglioma coexists with a ganglioneuroma component. They affect patients around 40 to 60 years old, with equal distribution across males and females (12). The size of composite paragangliomas ranges from 1 to 35 cm (13). In our case, the size of the tumor was considered to be an average one, about 6 × 4.2 × 3.7 cm (the volume was about 80 cc).

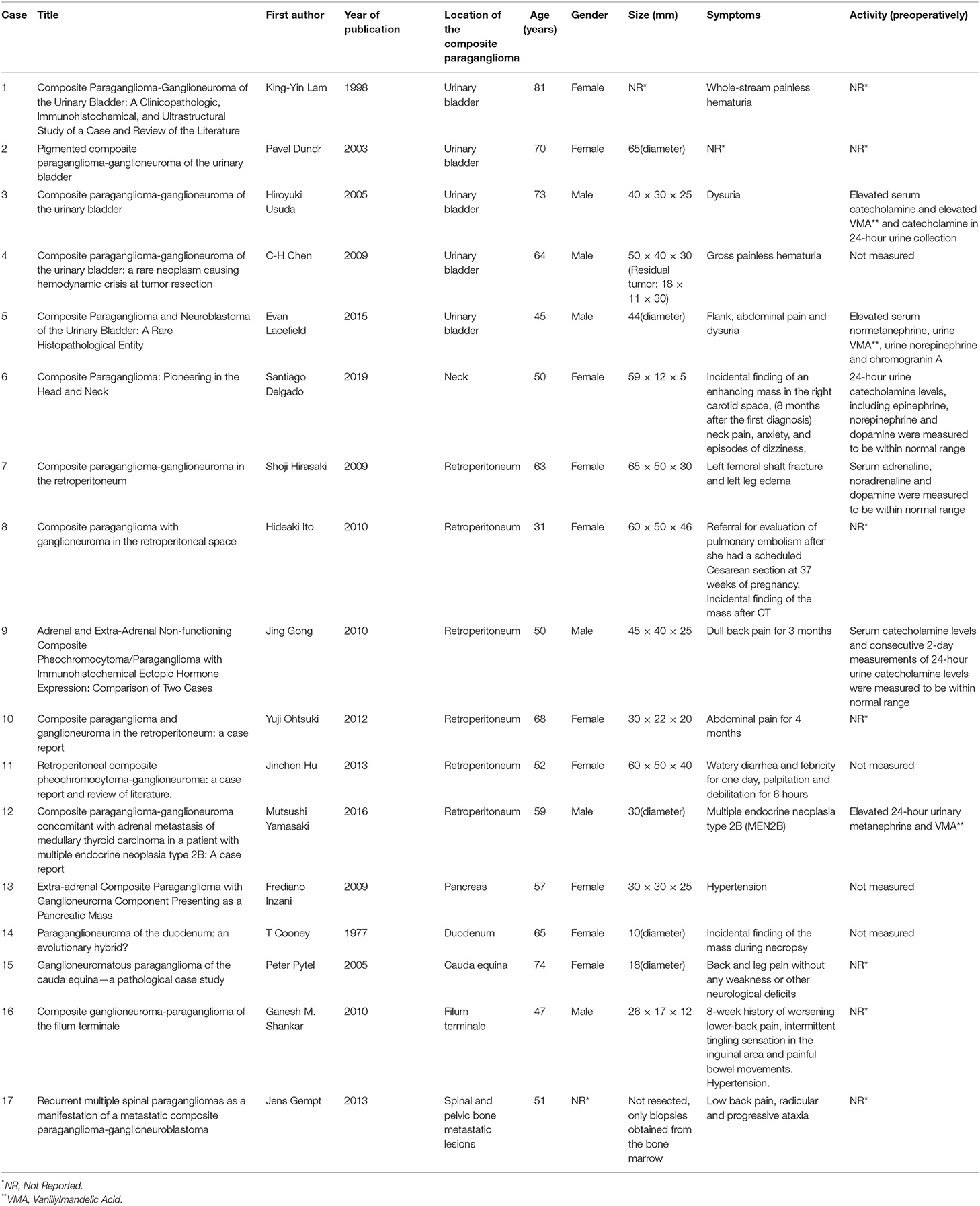

Fewer than 70 cases have been reported in the medical literature, most of which are located in the adrenal glands, while the extra-adrenal composite tumors have been reported only occasionally (14). In particular, only 17 extra-adrenal cases have been described in the literature so far (Table 2). From them 5 were found in the urinary bladder, 6 in the retroperitoneum, 1 in the neck, 1 in the duodenum, 1 in the pancreas, 1 in the filum terminale, 1 in the caude equine and 1 case of spinal and pelvic bone metastatic lesions. The mean age of all these cases was 58.8 years old, whereas 10 of them were females and 6 were males (In one case the gender was not reported). Thus, to our knowledge, in this study we describe the first case demonstrating a composite paraganglioma-ganglioneuroma located in the area near the celiac trunk, cephalad to the common hepatic artery.

Composite paragangliomas are often associated with familial neoplasm syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) (15). In multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), an autosomal-dominant cancer syndrome with major components of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), pheochromocytoma, and hyperparathyroidism, about 50% of the patients develop pheochromocytomas, located, almost always, in the adrenal medulla. Moreover, extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas (paragangliomas) are unusual (about 3% of the cases), while the co-existence of a composite paraganglioma-ganglioneuroma with any kind of MEN2-familial syndromes is quite rare (5). In our case, any association of this particular composite tumor was not confirmed, nor any kind of familial syndrome, based on the results of the genetic screening. However, it is worth mentioning that the patient has already undergone total thyroidectomy due to papillary, not medullary, metastatic cancer. In addition, in the postoperative imaging follow-up, a mass in the area of the head of the pancreas was found, constituting a point of concern, although it is currently attributed to a benign cystic lesion.

Imaging studies for the diagnosis of paragangliomas include CT or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan, while scintigraphy may be an alternative utility when these imaging tests fail to localize the tumor. Abdominal CT scan has an accuracy of about 85–95% for detecting tumors with a threshold size of 1 cm (16). Most of the pheochromocytomas reveal CT attenuation of more than 10 Hounsfield Units (HU) but sometimes it is quite difficult to differentiate a pheochromocytoma from another adenoma or adrenal metastasis (17). On the other hand, MRI is reported to have a sensitivity of about 100% in detecting adrenal pheochromocytomas, and in about 70% of T2-weighted images, the tumors appear hyperintense due to their water content or internal hemorrhage (18). Furthermore, scanning with 123iodine-labeled metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) may be helpful for cases in which CT or MRI are inconclusive, even though the pheochromocytoma has already been proven biochemically. Its specificity is reported to be between 82 and 92% and its sensitivity ranges widely, from 53 up to 94% (19).

In this case, we would like to emphasize the difficulty of establishing the diagnosis of paraganglioma preoperatively. The laboratory tests were indicative and the ultrasound imaging revealed a mass, without any special characteristic indicative of its origin. Moreover, an ultrasound-guided biopsy of this tumor suggested the diagnosis of a ganglioneuroma and not a paraganglioma. In addition, images obtained by CT scan were not characteristic of a paraganglioma, while CT-angiography just helped us identify the relations of the tumor with the celiac artery and the other structure of this area. As a result, the definite diagnosis of the composite paraganglioma was established only after the final pathology analysis of the excised tissue, and besides, it is very common to have the precise diagnosis for this kind of tumors only after the pathology examination have been completed (20).

The prognosis of composite paragangliomas varies and depends on the existence of malignancy. For non-malignant disease, the 5-year survival rate is more than 95%. However, in patients with malignancy, the 5-year survival rate is <50% (21). Dhir et al. reported that the likelihood of malignant disease is greater among younger patients, having a larger-sized tumor or being diagnosed with paraganglioma, as well as in patients with mutations in succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDHD) gene (22). Metastatic lesions are almost always derived from the neural component. Pheochromocytoma metastases, as a single entity or in conjunction with the malignant neural component, were found in some uncommon cases in which liver metastatic lesions were reported deriving from a composite paraganglioma (23). Fortunately, in our case, a locally advanced tumor according to imaging examination was not confirmed. However, based on the histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics, this composite paraganglioma of our patient is considered to have high malignancy potential, based on the GAPP score classification (Table 3). According to the detailed pathology report, the excised tumor had some foci of “zellballen and pseudorosette-forming” pattern, moderate to high cellularity, vascular and capsular invasion, Ki-67 immunoreactivity more than 1%, and also coagulation necrosis. In addition, the immunohistochemical analysis reported that the tumor was found to be positive in protein S100, which is also associated with a worse prognosis. As a result, this tumor scored 6–7 points and was classified as a tumor with moderate to low differentiation and of high metastatic risk (24). This is the reason why a very strict active surveillance of the patients is mandatory. Three months postoperatively, imaging examinations with CT scan and ultrasound were completed and no recurrent or metastatic disease has been documented so far.

In conclusion, composite paragangliomas comprise rare and potentially malignant tumors with variable prognosis. Establishing their diagnosis promptly is of vital significance. Based on our case, due to the first-described location of a composite paraganglioma near the celiac artery, the differential diagnosis of the tumors found in this area should include composite paragangliomas as well.

Author Contributions

GT and AMe were the chief investigators, wrote the manuscript, and collected the majority of the data. AC and AT conducted the histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis. IP and SA were the surgeons who conducted the excision of the tumor. II collected some additional data for the study. TP wrote and corrected the manuscript for its scientific basis. AMi was the director of the Department of Surgery and provided his permission for this study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer SM declared a shared affiliation with all the authors to the handling editor at the time of the review.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Usuda H, Emura I. Composite paraganglioma-ganglioneuroma of the urinary bladder. Pathol Int. (2005) 55:596–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01875.x

2. Linnoila RI, Keiser HR, Steinberg SM, Lack E. Histopathology of benign versus malignant sympathoadrenal paragangliomas: a clinicopathologic study of 120 cases including unusual histologic features. Hum Pathol. (1990) 21:1168–80. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90155-X

3. Inzani F, Rindi G, Tamborrino E, Rocco C, Cesare B. Extra-adrenal composite paraganglioma with ganglioneuroma component presenting as a pancreatic mass. Endocr Pathol. (2009) 20:191–5. doi: 10.1007/s12022-009-9085-z

4. Oyasu RYX, Yoshida O. What is the difference between pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma? What are the familial syndromes that have pheochromocytoma as a component? What are the pathologic features of pheochromocytoma indicating malignancy? Questions in Daily Urologic Practice: Updates for Urologists and Diagnostic Pathologists. Tokyo: Springer (2008) p. 280–4.

5. Wohllk N, Schweizer H, Erlic Z, Kurt Werner Schmid, Martin K Walz, Friedhelm Raue, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2. Best Pract Res Clinic Endocrinol Metabol. (2010) 24:371–87. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.02.001

6. Martins R, Bugalho MJ. Paragangliomas/Pheochromocytomas: clinically oriented genetic testing. Int J Endocrinol. (2014) 2014:794187. doi: 10.1155/2014/794187

7. Shahani S, Nudelman RJ, Nalini R, Kim HS, Samson S. Ectopic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) syndrome from metastatic small cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Diagnostic Pathol. (2010) 5:56. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-5-56

8. Gong J, Wang X, Chen X, Ni C, Rui H, Changli L. et al. Adrenal and extra-adrenal non-functioning composite pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma with immunohistochemical ectopic hormone expression: comparison of two cases. Urologia Internation. (2010) 85:368–72. doi: 10.1159/000317312

9. Medeiros LJ, Wolf BC, Balogh K, Federman M. Adrenal pheochromocytoma: a clinicopathologic review of 60 cases. Hum Pathol. (1985) 16:580–9. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(85)80107-6

10. Leavitt JR, Harold DL, Robinson RB. Adrenal ganglioneuroma: a familial case. Urology. (2000) 56:508. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00695-6

11. Theodossis S, Nick M, Karayannopoulou G, Isaak K, Tzioufa V, Raptou G, Spiros T. Papavramidis, Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma in an adult patient: a case report and literature review of the last decade. Southern Med J. (2009) 102:1065–7. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181b2fd37

12. Khan AN, Solomon SS, Childress RD. Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma: a rare experiment of nature. Endocr Pract Offic J Am Coll Endocrinol Am Assoc Clinic Endocrinol. (2010) 16:291–9. doi: 10.4158/EP09205.RA

13. Tischler AS. Divergent differentiation in neuroendocrine tumors of the adrenal gland. Semin Diagnostic Pathol. (2000) 17:120–6.

14. Hirasaki S, Kanzaki H, Okuda M, Suzuki S, Fukuhara T, Hanaoka T. Composite paraganglioma-ganglioneuroma in the retroperitoneum. World J Surg Oncol. (2009) 7:81. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-81

15. Gullu S, Gursoy A, Erdogan MF, Dizbaysak S, Erdogan G, Kamel N. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A/localized cutaneous lichen amyloidosis associated with malignant pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma. J Endocrinol Investigat. (2005) 28:734–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03347557

16. Szolar DH, Korobkin M, Reittner P, Berghold A, Bauernhofer T, Trummer H, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type. Radiology. (2005) 234:479–85. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342031876

17. Park BK, Kim CK, Kwon GY, Kim JH. Re-evaluation of pheochromocytomas on delayed contrast-enhanced CT: washout enhancement and other imaging features. Euro Radiol. (2007) 17:2804–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0695-x

18. Blake MA, Kalra MK, Maher MM, Sahani DV, Ann T Sweeney, Mueller PR, Hahn PF. Pheochromocytoma: an imaging chameleon. radiographics: a review publication of the Radiological Society. North America Inc. (2004) 24:S87–99. doi: 10.1148/rg.24si045506

19. Wiseman GA, Pacak K, O'Dorisio MS, Neumann DR, Waxman AD, Mankoff DA, et al. Usefulness of 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in the evaluation of patients with known or suspected primary or metastatic pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma: results from a prospective multicenter trial. J Nucl Med Offic Publicat Soc Nucl Med. (2009) 50:1448–54. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.058701

20. Disick GI, Palese MA. extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma: diagnosis and management. Current urology reports. (2007) 8:83–8. doi: 10.1007/s11934-007-0025-5

21. Hamidi O. Metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: recent advances in prognosis and management. Curr Opinion Endocrinol Diabet obesity. (2019) 26:146–54. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000476

22. Dhir M, Li W, Hogg ME, Bartlett DL, Carty SE, McCoy KL, et al. Clinical predictors of malignancy in patients with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Ann Surgic Oncol. (2017) 24:3624–30. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6074-1

23. Lam KY, Lo CY. Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland: an uncommon entity with distinctive clinicopathologic features. Endocr Pathol. (1999) 10:343–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02739777

24. Kimura N, Watanabe T, Noshiro T, Shizawa S, Miura Y. Histological grading of adrenal and extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas and relationship to prognosis: a clinicopathological analysis of 116 adrenal pheochromocytomas and 30 extra-adrenal sympathetic paragangliomas including 38 malignant tumors. Endocr Pathol. (2005) 16:23–32. doi: 10.1385/EP:16:1:023

Keywords: composite paraganglioma, ganglioneuroma, celiac trunk, case, neuroendocrine tumors

Citation: Tzikos G, Menni A, Cheva A, Pliakos I, Tsakona A, Apostolidis S, Iakovou I, Michalopoulos A and Papavramidis T (2022) Composite Paraganglioma of the Celiac Trunk: A Case Report and a Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Front. Surg. 9:824076. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.824076

Received: 28 November 2021; Accepted: 12 January 2022;

Published: 22 February 2022.

Edited by:

Alejandro Serrablo, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, SpainReviewed by:

Mariano Cesare Giglio, University of Naples Federico II, ItalySpiros Miliaras, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Copyright © 2022 Tzikos, Menni, Cheva, Pliakos, Tsakona, Apostolidis, Iakovou, Michalopoulos and Papavramidis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandra Menni, YWxleGFuZHJhLm1lbm5pQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Georgios Tzikos

Georgios Tzikos Alexandra Menni

Alexandra Menni Angeliki Cheva2

Angeliki Cheva2 Theodosios Papavramidis

Theodosios Papavramidis