Standing the test of COVID-19: charting the new frontiers of medicine

Explainer

Front Sci, 23 May 2024

This explainer is part of an article hub, related to lead article https://doi.org/10.3389/fsci.2024.1236919

What does the future of medicine look like?

Among its many impacts, COVID-19 has profoundly changed medical science and practice. The pandemic dramatically showed how infectious diseases, non-infectious diseases, and numerous individual, environmental, and social risk factors are interlinked in complex, dynamic ways. The urgency of the pandemic, and the challenges it imposed, also inspired rapid innovation—shedding new light on how we can solve health challenges of the future.

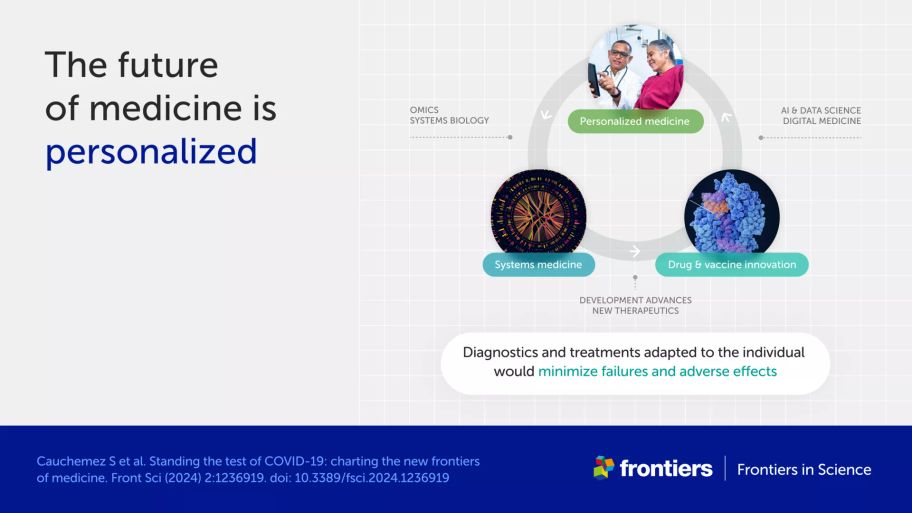

In their Frontiers in Science article, Goldman and colleagues lay out a vision for the future of medicine, supported by three intertwined pillars: personalized medicine, systems medicine, and digital medicine. The authors also lay out a framework for new interdisciplinary approaches to make this vision a reality for all.

This explainer summarizes the article’s main points.

How did COVID-19 change medical research and innovation?

COVID-19 affected patients profoundly differently, depending on their age, gender, underlying diseases, environment, and other factors; it also demanded profoundly different approaches and technologies in order to quickly control the pandemic. These challenges accelerated research and innovation across many fields—as evidenced by 9 percent more health and medical research articles being published in 2020-22 than expected.

COVID-19 drove the development and use of:

large-scale mathematical modeling for informing public health interventions

AI and big data for identifying potential treatments and vulnerable patients

digital options for treatment and care

radically faster vaccine development, through mRNA technologies, public-private funding partnerships, and novel clinical trial design

personalized therapies for communicable diseases.

The pandemic also highlighted the crucial importance of measures to ensure equitable access to medical innovation and international collaboration across multiple disciplines and sectors.

What is the future of drug and vaccine development?

The innovative changes in vaccine development unleashed by the pandemic will facilitate vaccines for other diseases. This includes emerging infectious diseases, chronic infectious diseases such as HIV, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, as well as non-communicable diseases such as cancer.

COVID-19 also revived the use of immunotherapy, where patients are treated with antibodies against a pathogen, and highlighted our ability to develop antiviral therapies. Both approaches could help patients with emerging and neglected diseases such as dengue fever, malaria, and Ebola, for which there are currently limited treatment options.

The article additionally highlights the urgent need for new antibacterial agents to tackle the ongoing threat of antimicrobial resistance. Promising approaches include pairing existing antibiotics with drugs that can inhibit resistance, and new methods for antibiotic discovery powered by genomics, synthetic biology, and other advanced biomedical and computational tools.

What is the future of personalized medicine?

Personalized (or precision) medicine takes into account that a mix of biological, social, and environmental factors affect each person’s reaction to a given disease—and also to a given treatment. Instead of treating the same disease the same way for everyone, personalized medicine aims to provide the right treatment at the right time to the right patient.

Personalized therapies are most common in cancer care but will increasingly benefit patients with other non-communicable diseases—including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and inflammatory disorders like multiple sclerosis—as well as communicable diseases. This will be driven by new ways of classifying patients: moving from clinical observations to novel biomarkers that reflect the underlying disease mechanism at the molecular level. Personalized medicine may also harness new therapies in the future, such as gene therapy and treatments targeting microbes living in our guts.

What is the future of systems medicine?

Systems medicine is an interdisciplinary approach that integrates data about the body’s various biological systems, as well as social and environmental factors, into a holistic understanding of health and disease. By using advanced computing and AI to analyze these “big data”, systems medicine helps to identify complex disease mechanisms, develop therapeutics, and inform both public health and individual treatment decisions.

Systems medicine will be driven by advances in data science and AI, and our increasing ability to collect big data from individuals—including clinical, immune, microbiome, genomic, and other “omic” data. The authors stress, however, that AI can introduce biases, which could disadvantage some patients if they aren’t controlled for. To use big data and AI safely, we need transparency about the tools we use and how they work, and robust privacy, safety, and equity standards to protect patients.

What is the future of digital medicine?

Digital medicine—using tools like video calls, smartphone apps, and wearable monitors—reduces the reliance on face-to-face contact to deliver healthcare. This can reduce costs, empower patients to take charge of their own medical care, and strengthen the resilience of healthcare systems.

While digital therapeutics such as blood glucose monitors are becoming more reliable, convenient, and inexpensive, Goldman et al. highlight several challenges in adopting their use. These include difficulties in “prescribing” digital health tools, and the need to train medical professionals not only as healthcare providers but also as healthcare facilitators. In addition, cost barriers and digital inequities mean such tools are not available to everyone. Digital medicine needs more trials to prove its worth, and access needs to be more equitable across the world.

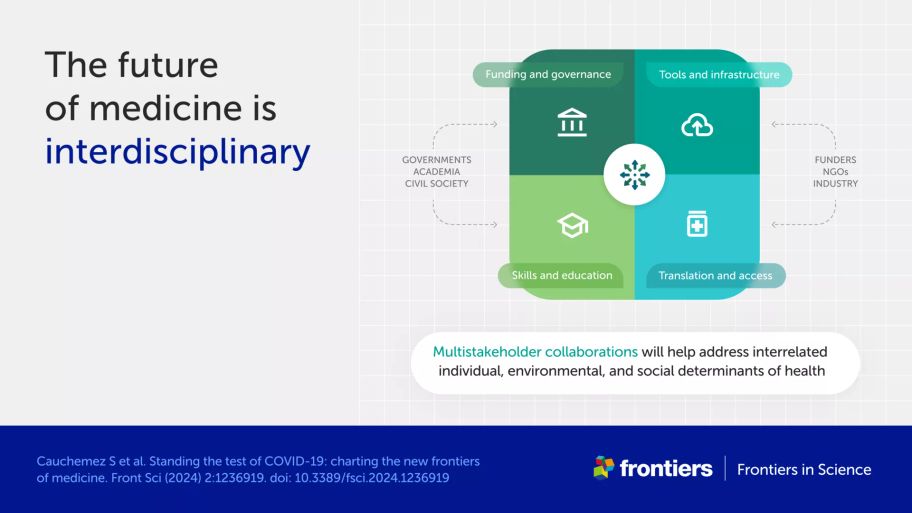

What do we need to build the medicine of the future?

To accomplish all this, knowledge, skills, and technologies must be integrated across a variety of disciplines and sectors that too-often operate in separate “silos”—including biomedical science, public health science, healthcare, data science, drug development, policy, economics, and social science. This requires researchers, government bodies, industry, and civil society organizations working in these areas to collaborate in radically new, interdisciplinary ways.

The authors outline four priority areas for fostering interdisciplinarity:

governance and funding of health research, for example, greater coordination between funding agencies and participation by all stakeholders in research program decisions

tools and infrastructures for analyzing and sharing data, based on open science approaches

interdisciplinary skills and education for biomedical and healthcare professionals, with a focus on addressing key gaps such as in data science

translation of candidate therapeutics to readily available market solutions via partnerships between academia and industry, innovative regulatory processes, and equitable access policies.

This collaborative, interdisciplinary framework will allow scientists and other stakeholders to unravel complex relationships between individual, environmental, and social factors that influence health and disease. The framework will also accelerate personalized medicine and improve public health—and ensure the future of medicine is available to everyone, all around the world.