95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 17 February 2025

Sec. Consciousness Research

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1550108

This article is part of the Research Topic Spirituality and Religion: Implications for Mental Health View all 42 articles

Introduction: This study examined the role of loneliness and the perception of God in affecting the satisfaction with life of Muslim individuals living alone in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the study explored the regulatory role of the perception of God in the relationship between individuals’ loneliness and satisfaction with life.

Methods: The research is a cross-sectional study that evaluates individuals’ loneliness, satisfaction with life, and perception of God. The study group consists of 378 individuals living alone in Turkey. Among the participants, 196 are women (51.9%) and 182 are men (48.1%). The UCLA loneliness scale, the satisfaction with life scale, the perception of God scale, and a personal information form were used as data collection tools in the study.

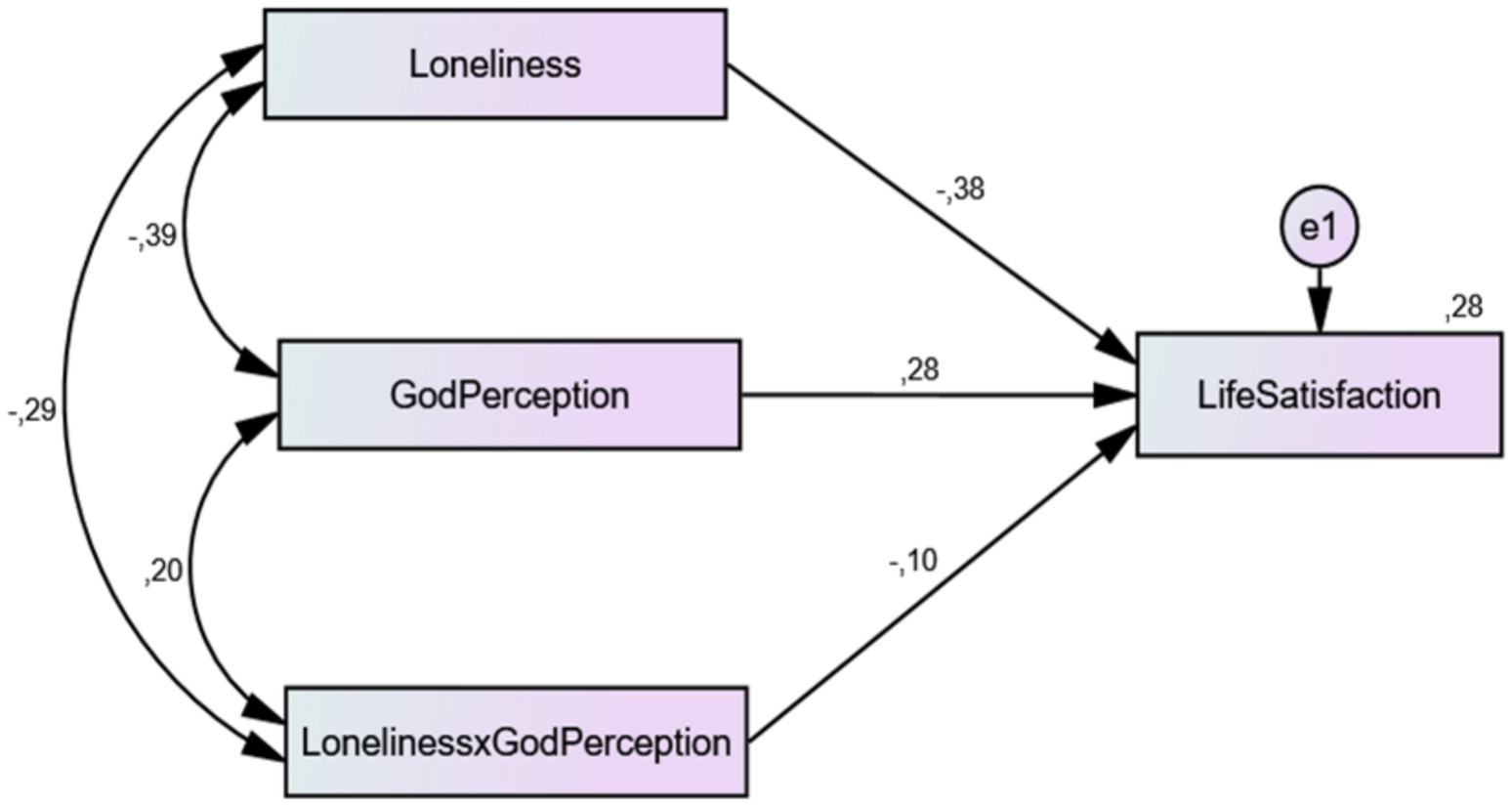

Results: The examination of research findings indicated that the variables of loneliness, perception of God, and the interaction between loneliness and the perception of God explained 28% of the variance in individuals’ satisfaction with life. We determined that satisfaction with life was affected significantly and positively by the perception of God (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) and significantly and negatively by loneliness (β = −0.38, p < 0.001). The interactional effect of the variables of loneliness and perception of God on satisfaction with life was also found to be significant (β = −0.10, p = 0.023). When we examined the details of the regulatory effect, we found that the effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life decreased even more in cases where the perception of God was high.

Discussion: The research findings suggest that loneliness decreases life satisfaction, while positive self-image mitigates this effect. It can be stated that using belief-sensitive therapeutic approaches in the therapeutic process could contribute to alleviating the negative effects of loneliness.

The world met COVID-19 in late 2019. Although first impressions were very frightening, many of us could not foresee that our habits in our daily life would change in the coming days. Many routines in our lives began to change with the appearance of the virus. This change process was mainly affected by the fact that the spread of the COVID-19 virus could not be stopped and that the virus brought many variants with it. From December 2019, when the first virus case was reported, to June 2020, more than 6.7 million people were affected by the virus and more than 390,000 people were reported to have died from the virus (World Health Organization, 2020a, 2020b).

The first news of death from COVID-19 in the country came on March 15, 2020. In this process, various pharmacological treatments were tried and vaccine studies accelerated. During this period, countries implemented various measures, such as working from home, local or general quarantine, travel restrictions, and closure of schools, to control the spread of the virus (Aydin and Kaya, 2021). Researchers emphasized that governments needed to combine multiple measures and implement them on time and over a long period to prevent the spread (Kelso et al., 2009). In other words, the wrong application of the measures by countries might worsen the pandemic. Research on the subject indicated that social distancing, in particular, could help alleviate the burden of the pandemic (Kelso et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2016). Accordingly, the World Health Organization (2020c) listed a series of recommendations on personal preventive measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Due to the COVID-19, which affected the entire world, many countries gradually closed their borders to other countries. Also, quarantines were put into practice. Partial and full closure periods were put into practice due to the increasing number of cases and deaths during this period. There is a substantial body of research evidence indicating a relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life during the COVID-19 pandemic (Deutrom et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Lorber et al., 2023; Onal et al., 2022).

Individuals’ satisfaction with life, which includes self-evaluation about their lives after changing periodic conditions, may also be affected for various reasons. The satisfaction with life examined in this study corresponds to a cognitive process that includes individuals’ evaluation of their life as a result of comparing their conditions and standards (Diener et al., 1985). On the other hand, loneliness, whose predictive effect on satisfaction with life will be examined in the study, can be considered as a concept that is formed as a result of individuals’ perception and evaluation of themselves and their social relations and whose cognitive side predominates. Peplau and Perlman (1982), who made significant contributions to the literature on loneliness, also discussed loneliness from a cognitive perspective. Young (1982), on the other hand, emphasized that loneliness was related to irrational beliefs and stated that erroneous beliefs would increase loneliness. Similarly, loneliness is seen as a result of perceived social isolation and this situation leads to excessive alertness towards (additional) social threats in the environment (Cacioppo et al., 2006). In other words, unconscious surveillance of a social threat brings with it cognitive biases. For example, lonely individuals see the social world as a more threatening place than individuals who are not lonely, expect more negative social interactions, and remember more negative social information (Cacioppo and Hawkley, 2009; Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). On the other hand, the perception of God, whose role as a moderator was examined in the study, is a concept with a cognitive dimension that includes the attributions and thoughts of the individual about God. Guthrie (2001) stated that there were many views that religion itself was generally a kind of cognition. In addition, according to researchers, holding beliefs strongly, whether referring to the existence or non-existence of God, can have a beneficial effect on its own by reducing cognitive contradiction and positively affect an individual’s well-being (Villani et al., 2019). The concepts of both satisfactions with life, loneliness, and the perception of God examined in the research are concepts that are shaped as a result of individuals’ perceptions and interpretations and have strong cognitive aspects. For this reason, this study was based on the cognitive approach. The basic idea of the ABC model, which is handled within the framework of the cognitive approach, shows that external events (A) cannot cause emotions (C), but beliefs can (B) (DiGiuseppe et al., 2014). In this context, first, we think that negative beliefs and thoughts (B) towards loneliness (A) may cause individuals to perceive their satisfaction with life (C) negatively. Secondly, we can say that the positive perceptions and thoughts of individuals (B) towards God (A) will contribute to the positive perception of their satisfaction with life (C). Finally, we think that in the case of loneliness (A), thoughts about the perception of God (B) will affect the satisfaction with life of individuals (C).

Satisfaction with life is a multidimensional concept because it includes both cognitive and emotional evaluations of life in general (Diener and Diener, 1995; Sam, 2001). These evaluations may include issues related to business life, as well as those related to private life and close relationships. This situation also diversifies the factors that can affect satisfaction with life. Some studies have shown that factors, such as having a meaningful life, enjoying life, and having a lot of engagement, are associated with satisfaction with life (Peterson et al., 2005). In addition to these, satisfaction with life is also affected by factors, such as demographic variables, personality traits, cognitive characteristics, health status (Chow, 2005), external factors, subjective evaluations, and emotional status (Diener, 1984). Research has shown that demographic variables, such as gender, age, and perceived economic status, also affect satisfaction with life (Peterson et al., 2005; Sam, 2001). Considering that personality traits can have an impact on worldview and coping, we can say that they are also related to satisfaction with life. Some studies confirm this view (Gish et al., 2022; Udayar et al., 2020; Weber and Huebner, 2015). Similarly, cognitive processes, which are the source of emotions and behaviors, have an effect on satisfaction with life, which is closely related to the individual’s evaluations of life (Ash and Huebner, 2001; Cummins and Nistico, 2002; Mehlsen et al., 2005). In addition, relationships with others are also among factors affecting satisfaction with life (Adams et al., 1996).

Man is a social being, and one of his/her basic needs is to establish meaningful and close relationships with other people. Inability to meet this need adequately results in loneliness. According to Peplau and Perlman (1982), loneliness is the difference between individuals’ existing social relationships and the social relationships they want to have. Peplau and Perlman (1982) proposed that there are three fundamental commonalities in the definition of loneliness: First, loneliness results from an individual’s limited social relationships. Second, loneliness is a subjective experience and varies based on the individual’s perception. It can emerge when one is alone or even in a crowd. Third, the experience of loneliness is unpleasant and distressing. Weiss (1973) examined loneliness under two categories: emotional and social loneliness. Social loneliness refers to the perceived inadequacy in social relationships and the individual’s failure to feel like a part of the group, event, or activity when sharing activities with others in their environment. Emotional loneliness, on the other hand, is when an individual does not perceive themselves as emotionally close to another person, feels distant, and senses a lack of acceptance (Diehl et al., 2018).

In the literature, loneliness is discussed in three categories, namely short-term, situational, and chronic loneliness (Saporta et al., 2021). Situational and short-term loneliness can be considered normal, while chronic loneliness can have negative effects on the individual, cause cognitive and emotional difficulties, and have consequences leading to pain and hopelessness. During the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine measures were implemented worldwide to prevent the spread of the disease, and during this period, people maintained a social life limited to their household. Individuals living alone, however, remained entirely on their own. It is believed that the social isolation initiated by this quarantine process could be a more challenging experience for individuals living alone. Overall, COVID-19 is reported to have had negative effects on mental health (Nilima et al., 2021; Schafer et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2020). Schluter et al. (2022), in their cross-sectional study conducted with participants from eight countries, concluded that quarantine and/or isolation measures during the pandemic were associated with significant mental health deterioration. Researchers have reported that the pandemic directly affected psychopathology regardless of gender, group, or region (Cénat et al., 2021; Demartini et al., 2020; Schafer et al., 2022).

Jaramillo and Felix (2023), using a qualitative constructivist theoretical approach to identify the psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and develop empirical insights, identified five themes in their study. These themes revolved around mental health experiences, family factors, pandemic-related communication, career/academic disruptions, and systemic/environmental factors. It is evident that the circumstances brought about by the pandemic have affected multiple areas of life. Studies reveal that social distancing and lockdowns implemented during the pandemic led to increased reports of loneliness (Chiesa et al., 2021; Hoffart et al., 2020; Ivbijaro et al., 2020) and that social isolation is associated with loneliness and satisfaction with life (Clair et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath have brought existential issues, often overlooked or avoided, to the surface. Research indicates that quarantine measures have caused psychological harm and triggered emotions such as loneliness (Brooks et al., 2020; Dagnino et al., 2020; Ganesan et al., 2021). In general, loneliness is reported to pose a risk, particularly for older adults (Donovan and Blazer, 2020; Fakoya et al., 2020). Based on the idea that loneliness may affect satisfaction with life, loneliness has been included as a variable in this research.

There are many research findings in the literature that reveal a significant relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life (Andrew and Meeks, 2018; Moore and Schultz, 1983; Sezer and Oktan, 2020; Schumaker et al., 1993; Swami et al., 2007; Tuzgöl Dost, 2007; Yıldırım-Kurtuluş et al., 2023). The majority of studies show a significant negative relationship between satisfaction with life and loneliness although they have been conducted with different age groups, in different cultures, and under different conditions (Ozben, 2013; Kearns et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016). Similar to this study, a study conducted with 466 participants in Switzerland during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that as loneliness and well-being were negatively correlated and that the level of well-being decreased as the level of loneliness increased (Gubler et al., 2021). In the literature, the concepts of satisfaction with life, happiness, and well-being are frequently used interchangeably. According to Diener (2009), satisfaction with life is the most important indicator of subjective well-being. In addition, many studies conducted before the pandemic revealed that there was a significant inverse correlation between loneliness and satisfaction with life. Some studies, including the study conducted by Cava et al. (2018) with adolescents aged between 12 and 17, Guignard et al. (2021) with gifted adolescents, Gan et al. (2020) with university students, Yukay-Yüksel et al. (2020) with young adults, Fernández-Alonso et al. (2012) with adult women, and Bai et al. (2018) with elderly individuals, showed that satisfaction with life decreased with the increase in loneliness. In addition to studies in which cross-sectional data had been used, the review of studies using longitudinal data indicated that satisfaction with life decreased with the increase in loneliness (Marttila et al., 2021; Nie et al., 2020; Tough et al., 2018). All these study results reveal that loneliness can be a significant predictor of satisfaction with life.

One of the factors that will be effective in combating adverse situations in an individual’s life is the religious beliefs and the perception of God. For example, Calvert (2010) concluded that having a close and secure relationship with God was positively related to psychological health and that this relationship contributed to the well-being of individuals. Also, Kelly (2020) concluded that devotion to God had a healing effect on loneliness. In the literature, research findings indicate significant relationships between the perception of God and loneliness (Le Roux, 1998; Scott et al., 2014). The perception of God is defined as the image of God in the mind of the individual, which includes all the emotions, thoughts, and references to God (Güler, 2007). Lawrence (1997) defined the perception of God as the chain of meanings attributed to the concept of God by the individual. Perceptions of God can be positive or negative; God can be perceived as forgiving and merciful by some and as punishing and unforgiving by others (Güler, 2007).

In the literature, many studies have investigated the effects of relationships with God, spirituality, secure attachment to God, perception of God, and similar variables on the individual (Bonhag and Upenieks, 2021; Bradshaw et al., 2010; Leman et al., 2018). In addition, findings suggest that a negative perception of God is associated with higher levels of distress and greater depression (Schaap-Jonker et al., 2017). Stulp et al. (2019), in a meta-analysis study conducted using a dataset of 29,963 individuals, concluded that a positive perception of God is associated with well-being, while a negative perception of God is associated with psychological distress. It appears that the perception of God is related to various other variables. For example, Le Roux (1998) concluded that individuals who had a strong faith experienced less loneliness and stated that loneliness mainly occurred when individuals broke their connections with God. Similarly, Kelly (2020) concluded that devotion to God would have healing effects on loneliness. Studying similar variables, Cosan (2014) concluded that there was a negative relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life. Numerous research findings indicate that the concepts of spirituality and religiosity significantly predict satisfaction with life (Esteban et al., 2021; Jafari et al., 2010; Marques et al., 2013).

Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1992) concluded that individuals who defined their relationship with God as a ‘secure attachment’ had higher levels of satisfaction with life and lower levels of loneliness. In addition, studies on the relationship between religion and spirituality and loneliness have shown that loneliness and spirituality are inversely correlated (Koenig et al., 2012). In addition, many studies have shown that there is a relationship between the perception of God and satisfaction with life (Benson and Spilka, 1973; Plouffe and Tremblay, 2017; Szcześniak et al., 2019; Zarzycka and Zietek, 2019). These results indicate significant relationships between variables. Piety, which can be defined as having strong ties with God and loyalty to the provisions of the religion to which one belongs, is evaluated as a concept associated with a positive perception of God (Kalmykova, 2021). In other words, religious individuals’ positive perception of God is significantly higher than the perception of those who are not religious. In the literature, some research results show that religiosity is positively correlated with satisfaction with life (Cohen et al., 2005; Lim and Putnam, 2010) and negatively with loneliness (Baumeister and Storch, 2004; Kirkpatrick et al., 1999). In their study on the relationship between the image of God and loneliness, Schwab and Petersen (1990) concluded that there was a positive correlation between loneliness and the image of an angry God, and a negative correlation with the image of a helpful/compassionate God. The result of the longitudinal research in which religion and loneliness were addressed revealed that the religious involvement of individuals reduced their loneliness (Upenieks, 2022). In addition to the quantitative studies, qualitative research results, which provide an in-depth examination of the research subject, have shown that religiosity protects individuals from loneliness (Ciobanu and Fokkema, 2017). This situation raises the question of whether the moderator role of the perception of God is significant in the relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life.

The perception of God, which was examined as the regulatory/moderator variable of the research, is associated with the schemas related to God in the mind of the individual (Güler, 2007). According to Seyhan (2014), the perception of God is largely related to what a person thinks and has learned about God, and from this point of view, it is a concept that is shaped at the cognitive level. From the point of view of the cognitive approach on which this research was based, schemas are shaped by the information acquired from childhood and can shape perceptions (Young et al., 2003). These schemas are influenced by the culture in which one lives, past experiences, and environmental factors (Boutyline and Soter, 2021). Perceptions of God can also be considered a type of schema. If an individual’s perception of God is forgiving, protective, and loving, this perception may serve a protective function during negative life events (McIntosh, 1995). In the context of this study, loneliness is a negative predictor of satisfaction with life. However, if the mediating variable, the perception of God, is positive, even if the individual feels lonely, they may find support in the presence of God, and the negative impact of loneliness on satisfaction with life may be mitigated. Using the ABC model as an example: A: The individual feels lonely. B: “God is everywhere, protecting and loving me.” C: When we consider satisfaction with life, the positive effect of the perception of God becomes more evident.

When God is considered a personal attachment figure, forming a positive relationship with Him can weaken the negative effects of loneliness (Minner, 2009). This relationship can function as a form of social support (Counted, 2016). Relationships with God, which are also thought to be effective in giving life meaning and helping individuals set goals, are likely to have positive effects on individuals (Jordan et al., 2021). The sample of this study consists of Muslim individuals, and it can be suggested that strong values in Islam, such as gratitude, patience, and contentment, positively influence satisfaction with life. The combination of a positive perception of God with these values is expected to alleviate the negative effects of loneliness and have a positive relationship with satisfaction with life. All religions promote solidarity, mutual assistance, and sharing among people. In this context, the relationship between loneliness and religion/faith can be exemplified.

We can say that a similar process is effective in the perception of God. From another point of view, the individual’s perception of God can also affect his/her perception and interpretation of his/her life and experiences (Koenig, 2012). We can say that an individual who perceives God as a forgiving, loving, and protective power will feel less alone and will always see God as supportive. From the point of view of the moderator effect of the perception of God, we can consider that those who have a positive perception of God, that is, those who perceive God as a forgiving, protective, and helping power, will feel God by their side in difficult times, which will reduce the feeling of loneliness and thus have positive effects on satisfaction with life (Stulp et al., 2019). We can say that those who constantly stay in contact with God through prayers or similar ways and feel God’s support will feel less lonely. This situation is thought to indirectly alleviate the detrimental effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life. In addition, studies on the subject in the literature mainly focus on Christianity and its sects, therefore, studies with individuals of different religions will contribute to the literature. Moreover, we think that examination of the role of the perception of God in reducing the effect of loneliness seen in individuals living alone during the COVID-19 process on their satisfaction with life makes this study original.

In the literature, studies have shown different kinds of relationships between loneliness, satisfaction with life, and the perception of God. We understand that the COVID-19 process has left deep traces in the lives of individuals and has an impact on their moods. In this process, research has shown that elderly individuals have difficulty overcoming COVID-19 more and that death rates of elderly individuals are higher (Antonelli et al., 2021). Considering all these, we predict that the feelings of loneliness of middle-aged and older individuals will increase during the closure period and as a result, their satisfaction with life will be affected. In addition, the negative experiences in this process, which also affect individuals’ perception of God, suggest that these individuals may experience their satisfaction with life in different ways.

In the literature, research is often conducted on the general population. However, studies focusing on samples consisting of middle-aged and older adults living alone are limited. From this perspective, it is believed that this research will contribute to the literature and fill a gap. Additionally, this study is one of the pioneering works demonstrating how the perception of God moderates the relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life in middle-aged and older individuals. This study was conducted to determine the relationship between the loneliness levels of individuals and their satisfaction with life and the regulating role of perception of God in this relationship. For this purpose, the following hypotheses were tested in the study:

1. The predictive effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life is significant.

2. The predictive effect of the perception of God on satisfaction with life is significant.

3. The predictive effect of the interaction between loneliness and perception of God on satisfaction with life is significant.

This research is a cross-sectional study that evaluates individuals’ loneliness, satisfaction with life, and perception of God. The study was conducted on individuals aged 40 and above who live alone in the provinces of Gümüşhane, Bayburt, and Erzurum. The sample was selected using simple random sampling methods (Fraenkel et al., 2012). The sample size was determined through power analysis. Using G*Power 3.1 software (Faul et al., 2009), the required sample size for multiple regression analysis was calculated as at least 107 participants, based on two predictor variables, an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and a medium effect size (Balkin and Sheperis, 2011).

The study group consisted of 378 individuals, including 196 females (51.9%) and 182 males (48.1%). The ages of the participants ranged between 40 and 65 (Mean = 52.81, SD = 6.08). Table 1 shows detailed information about the participants of the study.

First, the ethics committee approval was obtained in the study. Ethics committee approval (E-95674917-108.99-71601) was obtained from Gumushane University. An online questionnaire was created, explaining the study’s purpose, tools, and completion time, with an informed consent section for voluntary participants. Data were analyzed using SPSS 21 and IBM AMOS 23.

In this study, data collection tools included the UCLA Loneliness Scale, the Satisfaction with Life Scale, the Perception of God Scale, and a Personal Information Form. These tools are described below.

This form was prepared by the researcher. It consists of questions about the gender, age, economic status, and religious beliefs of the participants.

The UCLA loneliness scale, which was developed by Russell et al. (1978), was used to determine the loneliness levels of individuals in the study. The validity and reliability studies were conducted by Demir (1989) by adapting it to Turkish culture. It consists of 20 four-point Likert-type items. The scores that can be obtained from the scale range between 20 and 80, and high scoresshow intense feelings of loneliness. In the adaptation study of the scale to Turkish culture, the Cronbach’s alpha value calculated for reliability was found to be 0.96 (Demir, 1989). When examining studies conducted with the measurement tool, it was determined that the scale also produced highly reliable results in other studies. For example, in the study by Yıldırım et al. (2024), the Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.86, and in the study by Karaman and Haktanir (2024), the Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.83. For the reliability of the data obtained in this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value was calculated as 0.87, indicating that the results are highly reliable.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale was developed by Diener et al. (1985) to determine the level of individuals’ satisfaction with life. The validity and reliability studies were conducted by Ayten (2012) by adapting it to Turkish culture. There are five 7-point Likert-type items on the scale, and high scores indicate high levels of satisfaction with life. In the adaptation study of the scale, the reliability was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was found to be 0.85 (Ayten, 2012). A review of studies conducted with the measurement tool indicates that the scale has demonstrated high reliability in other research as well. For instance, in a study by Turan (2018), the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was reported as 0.82, while in a study by Ayten and Karagöz (2021), it was found to be 0.79. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.89, indicating a high level of reliability.

The Perception of God Scale was developed by Güler (2007). The validity and reliability studies of the 22-item, five-point Likert-type scale have been conducted. Higher scores reflect a positive perception of God, while lower scores indicate a negative perception. In the development study of the scale, the Cronbach’s alpha value calculated for reliability was found to be 0.83 (Güler, 2007). When examining studies conducted with the measurement tool, it was determined that the scale also produced highly reliable results in other studies. For example, Kiraç (2021) calculated the Cronbach’s alpha value as 0.93 in his study, and Yazıcı Çelebi and Kaya (2023) determined the Cronbach’s alpha value to be 0.92 in their study. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the data obtained in this study was calculated as 0.82, indicating that the results are highly reliable.

The researchers contacted individuals who were registered with official institutions with their contact and residence information and lived alone, using phone calls, social media, or email. Information about the study was provided, and a detailed survey form was shared with the individuals online. The survey included sections informing participants about their rights, including their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The survey was administered between January 2021 and March 2021, and participants took approximately 20 min to complete it. The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were:

a. Being an individual aged 40 or older who lives alone at home,

b. Being literate and able to provide information about loneliness, life satisfaction, and perception of God,

c. Having residence or contact information registered with official institutions.

The exclusion criteria were:

a. Lack of internet access,

b. Having a psychiatric disorder,

c. Not willing to participate in the study.

Using the contact information obtained from official institutions, the researchers attempted to reach approximately 450 individuals. As a result of these attempts, individuals without internet access (50 Participant), those who were illiterate (20 Participant), and those who did not want to participate in the study (2 Participant) were excluded.

Prior to conducting statistical analyses, several preparatory steps were taken. Data integrity and extreme value analyses revealed no missing values in the dataset. For extreme value detection, variable scores were converted to standardized z-scores, and all values were within the acceptable range of −3 to +3 (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2014). Next, skewness and kurtosis values were examined to assess normality. As shown in Table 1, all variables met the normality assumption, with values falling within the range of +2 to −2, consistent with criteria from the literature (George and Mallery, 2019). Descriptive statistics for all variables were subsequently calculated. To test the study’s hypothesis, path analysis was conducted using the IBM AMOS software with the maximum likelihood estimation method. Observed variables were used in the analysis, and predictor and moderator variables were standardized beforehand. Various fit indices were considered to assess how well the model aligned with the data. Accordingly, CFI and NFI values above 0.90, as well as RMSEA and SRMR values below 0.08, were used as benchmarks (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2016). An RMSEA value of 0.05 signifies a good fit, values between 0.05 and 0.08 represent an acceptable fit, while those exceeding 0.10 indicate a poor fit (Brown, 2015).

According to the results of the correlation analysis, there was a significant negative correlation between loneliness and satisfaction with life (r = −0.46, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.53, −0.37]) and the perception of God (r = −0.39, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.49, −0.29]) and a significant positive correlation between satisfaction with life and the perception of God (r = 0.40, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.32, 0.49]). The descriptive and correlation values of the variables used in the study are given in Table 2.

The results of the path analysis conducted with the observed variables regarding the regulatory role of the perception of God in the relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life are given in Table 3.

A path analysis was conducted to test the regulatory role of the perception of God regarding the effect of loneliness on individuals’ satisfaction with life. When examining the fit of the path analysis, it was confirmed that the model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (NFI = 1.000; CFI = 1.000; RMSEA = 0.088; SRMR = 0.000). When we examined the findings obtained within the scope of the research, we found that the variables of loneliness and the perception of God and the interaction between loneliness and perception of God explained 28% (R2 = 0.28) of the variation in individuals’ satisfaction with life. We determined that the perception of God had a significant positive effect on satisfaction with life (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) and that loneliness had a significant negative effect on it (β = −0.38, p < 0.001). The interactional effect (regulatory effect) of loneliness and perception of God variables on satisfaction with life was found to be significant (β = −0.10, p = 0.023). The results of the path analysis conducted with the observed variables regarding the regulatory role of the perception of God in the relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The regulatory role of the perception of God between loneliness and satisfaction with life.

Since the interactional effect was found significant as a result of the regulatory analysis conducted, a slope analysis was performed. The regulatory effects found as a result of the slope analysis are shown graphically in Figure 2.

When we examined the details of the regulatory effect, we found that the effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life decreased when the perception of God was high (B = −3.18, p < 0.001). Similarly, the effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life decreased in cases where the perception of God was low (B = −1.95, p < 0.001). In another result, the effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life decreased in cases where the perception of God was middle (B = −2.65, p < 0.001). According to the findings, when the perception of God was high, the effect of loneliness on satisfaction with life decreased further. This means that the relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life is regulated by the perception of God.

In this study, first, the findings regarding the differentiation of loneliness, satisfaction with life, and God perception based on gender were obtained, followed by the relationships between these variables and the moderating findings. These findings were then discussed in the discussion section. The findings obtained from the study indicate that perceptions of God do not differ based on gender. In the literature, different results have been observed in this regard. Along with studies that reached similar conclusions (Atan and Kula, 2024; Erdoğan, 2015), some studies show significant differences between women and men (Baynal and Uysal, 2023; Seyhan, 2014; Yıldız and Ünal, 2017). Another demographic finding of the study indicates that life satisfaction does not differ by gender in the older age group. There are different findings in the literature on this issue. Consistent with this research, some studies have found no gender-based differences (Altay and Avcı, 2009; Eshkoor et al., 2015; Tian and Chen, 2022). However, other studies suggest that women have higher life satisfaction (Della Giusta et al., 2011; Joshanloo and Jovanović, 2020; Kutubaeva, 2019), while some indicate that men report higher life satisfaction (Matud et al., 2014). The final analysis conducted in the study with demographic variables also indicates that loneliness levels do not differ by gender. Supporting studies (Gul et al., 2018; Maes et al., 2019) suggest that there is no gender-based difference in loneliness levels, while some studies show that women experience higher levels of loneliness (Doğan and Başer, 2019; Perlman, 2004). On the other hand, Lorber et al. (2023) report that loneliness levels are higher in men. The variation in results may stem from differences in the age groups of the samples, differences in gender perceptions, and interactions between gender and other variables. In this study, the focus on adult and elderly individuals may have led to gender-based differences being less prominent.

The results obtained from the study showed that there was a significant negative correlation between loneliness and satisfaction with life and that loneliness significantly predicted satisfaction with life. Accordingly, the first hypothesis of the study was confirmed. In the literature, many studies have shown a negative relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life (Bozorgpour and Salimi, 2012; Chow, 2005; Doman and Le Roux, 2012; Ekşi et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2016; Huebner et al., 2010; Kearns et al., 2015; Lee and Ishii-Kuntz, 1987; Lim and Kua, 2011; Yukay-Yüksel et al., 2020). Altay and Çalmaz (2023), in their study conducted with older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, found that isolation negatively impacted satisfaction with life. Social isolation disrupted or significantly limited support mechanisms that are important for individuals, leading to feelings of loneliness. This situation posed greater risks, particularly for older adults (Şahan et al., 2023). Research has shown that satisfaction with life is influenced by factors such as loneliness and social support (Cowlishaw et al., 2013; Ozmen et al., 2018; Ranta et al., 2013; Røysamb et al., 2003); higher satisfaction with life is associated with better social relationships (Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., 2001); and satisfaction with life is affected by interactions such as social support and social bonds (Segrin, 2006). Additionally, lonely individuals tend to have lower satisfaction with life (Goodwin et al., 2001; Swami et al., 2007). A study conducted by Bhutani and Greenwald (2021) revealed that loneliness had several negative consequences for older adults in the context of COVID-19. One of these consequences is the decline in satisfaction with life. Numerous studies have demonstrated that loneliness is a predictor of satisfaction with life, and these findings are consistent with the results of this study (Çivitci and Çivitci, 2009; Lorber et al., 2023; Vanhalst et al., 2013). Loneliness is associated with negative aspects of mental health (Eisses et al., 2004; Nangle et al., 2003; Stravynski and Boyer, 2001). When these findings were evaluated in terms of cognitive theory, individuals who were leading a normal life were put into quarantine in addition to the negative situation experienced and continued their lives alone for a certain period. The negative cognitions that individuals attributed to loneliness in this process might have caused them to perceive their satisfaction with life more negatively as a result. In other words, negative evaluations about situations that increased loneliness, such as the decrease in face-to-face interactions with others compared to the pre-pandemic period, problems with participating in social areas, and separation of individuals from each other due to the fear of infection, may have caused individuals to get less satisfaction with life. From this point of view, it is an expected result that loneliness is negatively related to satisfaction with life.

The results obtained from the study showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the perception of God and satisfaction with life and that the perception of God significantly predicted satisfaction with life. In this context, the second hypothesis examined in the study was confirmed. There are similar research findings showing a significant correlation between the perception of God and satisfaction with life (Hosseinsabet and Rady, 2015; Zahl and Gibson, 2012). From a broader perspective, we see that there are studies in the literature revealing that the perception of God is correlated with positive psychological elements. For example, Dilmaç and Çiftçi (2019) concluded that a positive perception of God was associated with psychological resilience. Maton (1989) and Schaefer and Gorsuch (1991) found that there was a positive relationship between positive perception of God and psychological health and a negative relationship with anxiety. Studies investigating the relationship between perception of God and mental health (Bradshaw et al., 2010), psychological well-being (Seyhan, 2014), and satisfaction with life (Zahl and Gibson, 2012) have indicated that positive perception of God is positively associated with positive psychological characteristics. In addition, some studies have shown that there is a positive relationship between negative perception of God and anxiety and trauma (Justice and Lambert, 1986; Kane et al., 1993). When we evaluated this finding in terms of cognitive theory, we concluded that the strength found in the presence of God during the lockdown process and feeling that God was always by their side by individuals who considered God as the source of love and a forgiving and protective power would also positively affect their evaluations of their lives in general. Indeed, researchers have reported that having strong beliefs about the existence of God has a positive effect on the individual’s well-being by reducing cognitive dissonance (Villani et al., 2019). We can state that the positive perception of God by individuals who are in the process of social isolation and whose life processes have changed contributes to them feeling less lonely in this process and, as a result, getting more satisfaction from life. Enea et al. (2021) found that during the COVID-19 period, people’s levels of loneliness and their engagement with matters related to God increased.

The results obtained from the study showed that the interaction between loneliness and the perception of God significantly predicted satisfaction with life. In this context, the third hypothesis examined in the study was confirmed. The results of the research have shown that there is an inverse relationship between the perception of God and loneliness. In other words, individuals with a positive perception of God have lower levels of loneliness. The belief in God in Islam is that God is always everywhere. We can say that people who have strong faith can feel that God is with them and that they think they are in constant communication with God through prayers or worship, which will reduce the feeling of loneliness. In a similar study, the relationships between loneliness, perception of God, and dysfunctional attitudes were examined, and the researchers found that there was a negative relationship between perception of God and loneliness (Mohammadpour et al., 1985). Similarly, Kirkpatrick et al. (1999) and Le Roux (1998) concluded that spirituality reduced the level of loneliness. When the result of the research regarding the moderator finding is considered in terms of cognitive theory, we can say that the individual’s positive perception of God and the idea that God is a protective power that is always with him/her will affect his/her evaluations of loneliness and reduce the feeling of loneliness. Thus, we can state that individuals’ satisfaction with life will be affected less negatively. This situation seems to be compatible with the understanding of the cognitive approach that connects the basis of emotions to thoughts. The positive perception of God can be associated with alleviating the negative effects of loneliness on satisfaction with life and the tendency of the individual’s evaluations of his/her own life to be positive. Muhammad et al. (2023), in their study conducted with older adults in India, found that elderly individuals who felt lonely reported lower satisfaction with life. They also concluded that the negative impact of loneliness on satisfaction with life was mitigated by religiosity, spirituality, and religious participation. Similarly, another study conducted with a Christian sample demonstrated that closeness to God predicts satisfaction with life (Culver, 2021). These findings are consistent with the results of this study and also highlight the importance of representations of the God figure-how individuals conceptualize God in their minds-regardless of the religion they belong to. Based on all these research findings, we can say that positive perception of God is associated with psychological health and positive emotional status and plays a protective role. Research findings have shown that the perception of God has a regulatory role between loneliness and satisfaction with life. In the literature, no research findings on this subject were found. In this context, we think that the findings of the current research will contribute to the field. Loneliness is negatively correlated with satisfaction with life. As the level of loneliness increases, satisfaction with life decreases, and the perception of God affects this relationship. We can say that individuals who have a positive perception of God, that is, who perceive God as forgiving and reassuring, who think they are in communication with God through prayers, worship, or similar ways, and who feel that God is always by their side as a supporting power, have lower levels of loneliness, and that this positively affects their satisfaction with life. In light of these findings, it can be suggested that a faith-sensitive therapeutic approach may be effective when addressing issues such as loneliness or satisfaction with life during the therapy process. Experimental studies could be recommended to test the effectiveness of incorporating the client’s belief system and spiritual practices (such as prayer, worship, meditation, etc.) into therapy. Additionally, we think that studies conducted with larger sample groups and different variables will be beneficial for ensuring the generalizability of the results. The Turkish society, which forms the sample of this study, is a collectivist society. Therefore, variables such as social isolation and loneliness need to be addressed within this context. The reflection of these variables may be different in individualistic societies. For this reason, we believe that cross-cultural comparative studies will contribute to the literature. Policies could be developed to protect middle-aged and older adults from the negative effects of loneliness, and support programs could be created to encourage socialization and integration into life. Structured group counseling programs for elderly individuals could be implemented in the field of social services.

In this study, there are a few additional limitations I would like to express. First, the sample consisted of 378 participants residing in the provinces of Gümüşhane, Bayburt, and Erzurum, predominantly Muslims. Future studies could include a larger and more diverse sample from various regions and religious backgrounds to provide broader insights into the moderating role of God perception in the relationship between loneliness and satisfaction with life. Another limitation is that the data were collected from elderly participants who were literate and had access to the internet, which may not represent the wider elderly population. We can say that literacy may cause differences compared to individuals who are not literate in many aspects, especially in terms of following the developments in the COVID-19 process. At this point, the results of the current study can be generalized by examining the relationships between loneliness, perception of God, and satisfaction with life in individuals who are not literate and do not have internet access.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Gümüşhane University Social Sciences Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

FK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., and King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 81, 411–420. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411

Altay, B., and Avcı, İ. A. (2009). Huzurevinde yasayan yaslılarda özbakım gücü ve yasam doyumu arasındaki ilişki [the relation between the self care strength and life satisfaction of the elderly living in nursing home]. Dicle Medical Journal/Dicle Tıp Dergisi 36, 275–282.

Altay, B., and Çalmaz, A. (2023). Perception of loneliness and life satisfaction in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic process. Psychogeriatrics 23, 177–186. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12911

Andrew, N., and Meeks, S. (2018). Fulfilled preferences, perceived control, life satisfaction, and loneliness in elderly long-term care residents. Aging Ment. Health 22, 183–189. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1244804

Antonelli, M., Penfold, R. S., Merino, J., Sudre, C. H., Molteni, E., Berry, S., et al. (2021). Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID symptom study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 43–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00460-6

Ash, C., and Huebner, E. S. (2001). Environmental events and life satisfaction reports of adolescents: a test of cognitive mediation. Sch. Psychol. Int. 22, 320–336. doi: 10.1177/0143034301223008

Atan, B., and Kula, N. (2024). Roman bireylerde Tanrı algısı [perception of god in gypsy individuals]. Kocatepe İslami İlimler Dergisi 7, 121–144. doi: 10.52637/kiid.1453684

Aydin, F., and Kaya, F. (2021). Does compliance with the preventive health behaviours against COVID-19 mitigate the effects of depression, anxiety and stress? Stud. Psychol. 42, 652–676. doi: 10.1080/02109395.2021.1950462

Ayten, A. (2012). Tanrıya sığınmak: Dini başa çıkma üzerine psiko-sosyal bir araştırma [Taking refuge in God: A psychosocial study on religious coping]. İstanbul: İz Yayıncılık.

Ayten, A., and Karagöz, S. (2021). Religiosity, spirituality, forgiveness, religious coping as predictors of life satisfaction and generalized anxiety: a quantitative study on Turkish Muslim university students. Spiritual Psychol. Counsel. 6, 47–58. doi: 10.37898/spc.2021.6.1.130

Bai, X., Yang, S., and Knapp, M. (2018). Sources and directions of social support and life satisfaction among solitary Chinese older adults in Hong Kong: the mediating role of sense of loneliness. Clin. Interv. Aging 13, 63–71. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S148334

Balkin, R. S., and Sheperis, C. J. (2011). Evaluating and reporting statistical power in counseling research. J. Couns. Dev. 89, 268–272. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00088.x

Baumeister, A. L., and Storch, E. A. (2004). Correlations of religious beliefs with loneliness for an undergraduate sample. Psychol. Rep. 94, 859–862. doi: 10.2466/pr0.94.3.859-862

Baynal, F., and Uysal, S. (2023). Relationship between psychological resilience, forgiveness and god perception. Darulfunun İlahiyat 34, 283–306. doi: 10.26650/di.2023.34.1.1269464

Benson, P., and Spilka, B. (1973). God image as a function of self-esteem and locus of control. J. Sci. Study Relig. 12, 297–310. doi: 10.2307/1384430

Bhutani, S., and Greenwald, B. (2021). Loneliness in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review in preparation for a future study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 29, S87–S88. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.081

Bonhag, R., and Upenieks, L. (2021). Mattering to god and to the congregation: gendered effects in mattering as a mechanism between religiosity and mental health. J. Sci. Study Relig. 60, 890–913. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12753

Boutyline, A., and Soter, L. K. (2021). Cultural schemas: what they are, how to find them, and what to do once you’ve caught one. Am. Sociol. Rev. 86, 728–758. doi: 10.1177/00031224211024525

Bozorgpour, F., and Salimi, A. (2012). State self-esteem, loneliness and life satisfaction. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 69, 2004–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.157

Bradshaw, M., Cristopher, G. E., and Marcum, J. P. (2010). Attachment to god, images of god, and psychological distress in a nationwide sample of presbyterians. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 20, 130–147. doi: 10.1080/10508611003608049

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Cacioppo, J. T., and Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., et al. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J. Res. Pers. 40, 1054–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

Calvert, S. J. (2010). Attachment to god as a source of struggle and strength: Exploring the association between christians’ relationship with god and their emotional wellbeing (doctorial thesis) Massey University, New Zealand.

Cava, M.-J., Buelga, S., and Tomás, I. (2018). Peer victimization and dating violence victimization: the mediating role of loneliness, depressed mood, and life satisfaction. J. Interpers. Violence 36, 2677–2702. doi: 10.1177/0886260518760013

Cénat, J. M., Blais-Rochette, C., Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Noorishad, P. G., Mukunzi, J. N., McIntee, S. E., et al. (2021). Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 295:113599. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599

Chiesa, V., Antony, G., Wismar, M., and Rechel, B. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic: health impact of staying at home, social distancing and ‘lockdown’measures—a systematic review of systematic reviews. J. Public Health 43, e462–e481. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab102

Chow, H. P. H. (2005). Life satisfaction among university students in a Canadian prairie city: a multivariate analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 70, 139–150. doi: 10.1007/s11205-004-7526-0

Ciobanu, R. O., and Fokkema, T. (2017). The role of religion in protecting older Romanian migrants from loneliness. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 43, 199–217. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1238905

Çivitci, N., and Çivitci, A. (2009). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction in adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 47, 954–958. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.022

Clair, R., Gordon, M., Kroon, M., and Reilly, C. (2021). The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:28. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3

Cohen, A. B., Pierce, J. D.Jr., Chambers, J., Meade, R., Gorvine, B. J., and Koenig, H. G. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity, belief in the afterlife satisfaction in young Catholics and Protestants. J. Res. Pers. 39, 307–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2004.02.005

Cosan, D. (2014). An evaluation of loneliness. Eur. Proceed. Soc. Behav. Sci. 1, 103–110. doi: 10.15405/epsbs.2014.05.13

Counted, V. (2016). God as an attachment figure: a case study of the god attachment language and god concepts of anxiously attached Christian youths in South Africa. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 18, 316–346. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2016.1176757

Cowlishaw, S., Niele, S., Teshuva, K., Browning, C., and Kendig, H. (2013). Older adults' spirituality and life satisfaction: a longitudinal test of social support and sense of coherence as mediating mechanisms. Ageing Soc. 33, 1243–1262. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12000633

Culver, J. (2021). How consistency in closeness to god predicts psychological resources and life satisfaction: findings from the national study of youth and religion. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 38, 103–123. doi: 10.1177/0265407520956710

Cummins, R. A., and Nistico, H. (2002). Maintaining life satisfaction: the role of positive cognitive bias. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 37–69. doi: 10.1023/A:1015678915305

Dagnino, P., Anguita, V., Escobar, K., and Cifuentes, S. (2020). Psychological effects of social isolation due to quarantine in Chile: an exploratory study. Front. Psych. 11:591142. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.591142

Della Giusta, M., Jewell, S. L., and Kambhampati, U. S. (2011). Gender and life satisfaction in the UK. Fem. Econ. 17, 1–34. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2011.582028

Demartini, B., Nisticò, V., D'Agostino, A., Priori, A., and Gambini, O. (2020). Early psychiatric impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population and healthcare workers in Italy: a preliminary study. Front. Psych. 11:561345. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561345

Demir, A. (1989). UCLA Yalnızlık ölçeğinin geçerlik ve güvenirliği [Validity and reliability of the UCLA loneliness scale]. Turk. J. Psychol. 7, 14–18.

Deutrom, J., Katos, V., and Ali, R. (2021). Loneliness, life satisfaction, problematic internet use and security behaviours: re-examining the relationships when working from home during COVID-19. Behav. Inform. Technol. 41, 3161–3175. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2021.1973107

Diehl, K., Jansen, C., Ishchanova, K., and Hilger-Kolb, J. (2018). Loneliness at universities: determinants of emotional and social loneliness among students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:1865. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15091865

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Diener, E., and Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 653–663. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

DiGiuseppe, R., Doyle, K. A., Dryden, W., and Bacx, W. (2014). A practioner’s guide to rational emotive behavior therapy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dilmaç, B., and Çiftçi, A. (2019). 14-18 yaş grubunda tanrı algısı ile psikolojik sağlamlık ilişkisinin incelenmesi [İnvestigation of the relationship between god perception and psychological resilience in the 14-18 age group]. Necmettin Erbakan Univ. Eregli Faculty Educ. J. 1, 14–28.

Doğan, S., and Başer, M. (2019). Yaşlılarda yalnızlık: Bir saha araştırması [Loneliness in the elderly: A field study]. J. Health Sci. Manage. 1, 1–10.

Doman, L. C., and Le Roux, A. (2012). The relationship between loneliness and psychological well-being among third-year students: a cross-cultural investigation. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 5, 153–168. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2011.579389

Donovan, N. J., and Blazer, D. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: review and commentary of a national academies report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005

Eisses, A. M. H., Kluiter, H., Jongenelis, K., Pot, A. M., Beekman, A. T. F., and Ormel, J. (2004). Risk ındicators of depression in residential homes. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 19, 634–640. doi: 10.1002/gps.1137

Ekşi, H., Çini, A., and Sevim, E. (2020). Çocuklarda okul temelli yalnızlık ve yaşam doyumu arasındaki ilişkide algılanan stresin aracı rolü [the role of perceived stress in the relationship between school-based loneliness and satisfaction with life in children]. Kastamonu Educ. J. 28, 1460–1470. doi: 10.24106/kefdergi.4128

Enea, V., Eisenbeck, N., Petrescu, T. C., and Carreno, D. F. (2021). Perceived impact of quarantine on loneliness, death obsession, and preoccupation with god: predictors of increased fear of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 12:643977. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643977

Erdoğan, E. (2015). Tanrı algısı, dinî yönelim biçimleri ve öznel dindarlığın psikolojik dayanıklılıkla ilişkisi: Üniversite örneklemi [the relationship of resilience with god perception forms, religion orientation and subjective religiousness: a sample of university students]. Mustafa Kemal University J. Soc. Sci. 1, 1–10. doi: 10.29228/JOHESAM.43

Eshkoor, S., Hamid, T., Mun, C., and Shahar, S. (2015). An investigation on predictors of life satisfaction among the elderly. Int. E-J. Adv. Soc. Sci. 1, 207–212. doi: 10.18769/ijasos.86859

Esteban, R. F. C., Turpo-Chaparro, J. E., Mamani-Benito, O., Torres, J. H., and Arenaza, F. S. (2021). Spirituality and religiousness as predictors of life satisfaction among Peruvian citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 7:e06939. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06939

Fakoya, O. A., McCorry, N. K., and Donnelly, M. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 20, 129–114. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., and Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analysesusing G*power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

Fernández-Alonso, A. M., Trabalón-Pastor, M., Vara, C., Chedraui, P., and Pérez-López, F. R.MenopAuse RIsk Assessment (MARIA) Research Group (2012). Life satisfaction, loneliness and related factors during female midlife. Maturitas 72, 88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.02.001

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., and Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to design and evaluate research in education. 8th Edn. New York: McGraw Hill Education.

Gan, S. W., Ong, L. S., Lee, C. H., and Lin, Y. S. (2020). Perceived social support and life satisfaction of Malaysian Chinese young adults: the mediating effect of loneliness. J. Genet. Psychol. 181, 458–469. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2020.1803196

Ganesan, B., Al-Jumaily, A., Fong, K. N., Prasad, P., Meena, S. K., and Tong, R. K. Y. (2021). Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak quarantine, isolation, and lockdown policies on mental health and suicide. Front. Psych. 12:565190. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.565190

George, D., and Mallery, P. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics 26 step by step: A simple guide and reference. 15th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gish, J. J., Guedes, M. J., Silva, B. G., and Patel, P. C. (2022). Latent profiles of personality, temperament, and eudaimonic well-being: comparing life satisfaction and health outcomes among entrepreneurs and employees. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 17:e00293. doi: 10.1016/j.jbvi.2021.e00293

Goodwin, R., Cook, O., and Yung, Y. (2001). Loneliness and life satisfaction among three cultural groups. Pers. Relat. 8, 225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2001.tb00037.x

Gubler, D. A., Makowski, L. M., Troche, S. J., and Schlegel, K. (2021). Loneliness and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with personality and emotion regulation. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 2323–2342. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00326-5

Guignard, J. H., Bacro, F., and Guimard, P. (2021). School life satisfaction and peer connectedness of intellectually gifted adolescents in France: is there a labeling effect? New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 59–74. doi: 10.1002/cad.20448

Gul, S. N., Chishti, R., and Bano, M. (2018). Gender differences in social support, loneliness, and isolation among old age citizens. Peshawar J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 4, 15–31. doi: 10.32879/picp.2018.4.1.15

Güler, Ö. (2007). Tanrı Algısı Ölçeği (TA): Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması [God Perception Scale: Its validity and reliabilty]. J. Faculty Divinity Ankara Univ. 48, 123–133. doi: 10.1501/Ilhfak_0000000932

Guthrie, S. (2001). “Why gods? A cognitive theory” in Religion in mind: Cognitive perspectives on religious belief, ritual, and experience. ed. J. Andresen (New York: Cambridge University Press), 94–112.

Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Hoffart, A., Johnson, S. U., and Ebrahimi, O. V. (2020). Loneliness and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: risk factors and associations with psychopathology. Front. Psych. 11:589127. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589127

Hosseinsabet, F., and Rady, M. (2015). The association between god image and life satisfaction in Shiraz University students. J. Res. Religion Health 1, 19–27.

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, J., Hu, J., Huang, G., and Zheng, X. (2016). Life satisfaction, self-esteem, and loneliness among LGB adults and heterosexual adults in China. J. Homosex. 63, 72–86. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1078651

Huebner, E. S., Antaramian, S., Hills, K., Lewis, A., and Saha, R. (2010). Stability and predictive validity of the BMSLSS. Child Indic. Res. 4, 161–168. doi: 10.1007/s12187-010-9082-2

Ivbijaro, G., Brooks, C., Kolkiewicz, L., Sunkel, C., and Long, A. (2020). Psychological impact and psychosocial consequences of the COVID 19 pandemic resilience, mental well-being, and the coronavirus pandemic. Indian J. Psychiatry 62, 395–403. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1031_20

Jafari, E., Najafi, M., Sohrabi, F., Dehshiri, G. R., Soleymani, E., and Heshmati, R. (2010). Life satisfaction, spirituality well-being and hope in cancer patients. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 5, 1362–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.288

Jaramillo, N., and Felix, E. D. (2023). Understanding the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latinx emerging adults. Front. Psychol. 14:1066513. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1066513

Jordan, K. D., Niehus, K. L., and Feinstein, A. M. (2021). Insecure attachment to god and interpersonal conflict. Religions 12:739. doi: 10.3390/rel12090739

Joshanloo, M., and Jovanović, V. (2020). The relationship between gender and life satisfaction: analysis across demographic groups and global regions. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 23, 331–338. doi: 10.1007/s00737-019-00998-w

Justice, W. G., and Lambert, W. (1986). A comparative study of the language people use to describe the personalities of god and their earthly parents. J. Pastoral Care 40, 166–172. doi: 10.1177/002234098604000210

Kalmykova, E. (2021). Faith assimilated to perception: the embodied perspective. Sophia 60, 989–1007. doi: 10.1007/s11841-020-00764-x

Kane, D., Cheston, S. E., and Greer, J. (1993). Perceptions of god by survivors of childhood sexual abuse: an exploratory study in an underresearched area. J. Psychol. Theol. 21, 228–237. doi: 10.1177/009164719302100306

Karaman, M. A., and Haktanir, A. (2024). Effects of loneliness and depression on pre-service teachers’ self-esteem: a mixed method study. Teach. Dev., 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2024.2406865

Kearns, A., Whitley, E., Tannahill, C., and Ellaway, A. (2015). Loneliness, social relations and health and well-being in deprived communities. Psychol. Health Med. 20, 332–344. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.940354

Kelly, J. M. (2020). Does Christian faith impact loneliness? Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/psyd/333 (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Kelso, J. K., Milne, G. J., and Kelly, H. (2009). Simulation suggests that rapid activation of social distancing can arrest epidemic development due to a novel strain of influenza. BioMed Central Public Health 9:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-117

Kiraç, F. (2021). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and god image among Turkish Muslims. Arch. Psychol. Relig. 43, 297–316. doi: 10.1177/00846724211047274

Kirkpatrick, L. A., and Shaver, P. R. (1992). An attachment-theoretical approach to romantic love and religious belief. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 18, 266–275. doi: 10.1177/0146167292183002

Kirkpatrick, L. A., Shillito, D. J., and Kellas, S. L. (1999). Loneliness, social support, and perceived relationships with god. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 16, 513–522. doi: 10.1177/0265407599164006

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. Int. Scholar. Res. Notices 2012:278730. doi: 10.5402/2012/278730

Koenig, H., King, D. E., and Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Honkanen, R., Viinamaki, H., Heikkila, K., Kaprio, J., and Koskenvuo, M. (2001). Life satisfaction and suicide: a 20-year follow-up study. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 433–439. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.433

Kumar, P., Kumar, N., Aggarwal, P., and Yeap, J. A. L. (2021). Working in lockdown: the relationship between COVID-19 induced work stressors, job performance, distress, and life satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 40, 6308–6323. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01567-0

Kutubaeva, R. Z. (2019). Analysis of life satisfaction of the elderly population on the example of Sweden, Austria and Germany. Popul. Econ. 3, 102–116. doi: 10.3897/popecon.3.e47192

Lawrence, R. T. (1997). Measuring the image of god: the god image inventory and the god image scales. J. Psychol. Theol. 25, 214–226. doi: 10.1177/009164719702500206

Le Roux, A. (1998). The relationship between loneliness and the Christian faith. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 28, 174–181. doi: 10.1177/008124639802800308

Lee, G. R., and Ishii-Kuntz, M. (1987). Social interaction, loneliness, and emotional well-being among the elderly. Res. Aging 9, 459–482. doi: 10.1177/0164027587094001

Leman, J., Hunter, W., Fergus, T., and Rowatt, W. (2018). Secure attachment to god uniquely linked to psychological health in a national, random sample of American adults. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 28, 162–173. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2018.1477401

Lim, L. L., and Kua, E. H. (2011). Living alone, loneliness and psychological well-being of older persons in Singapore. Current Gerontol. Geriatrics Res. 2011, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/673181

Lim, C., and Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, social networks and life saticfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 75, 914–933. doi: 10.1177/0003122410386686

Liu, M., Ou, J., Zhang, L., Shen, X., Hong, R., Ma, H., et al. (2016). Protective effect of hand-washing and good hygienic habits against seasonal influenza. Medicine 95:e3046. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003046

Lorber, M., Černe Kolarič, J., Kmetec, S., and Kegl, B. (2023). Association between loneliness, well-being, and life satisfaction before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Sustain. For. 15:2825. doi: 10.3390/su15032825

Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Van den Noortgate, W., and Goossens, L. (2019). Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: a meta–analysis. Eur. J. Personal. 33, 642–654. doi: 10.1002/per.2220

Marques, S. C., Lopez, S. J., and Mitchell, J. (2013). The role of hope, spirituality and religious practice in adolescents’ life satisfaction: longitudinal findings. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9329-3

Marttila, E., Koivula, A., and Räsänen, P. (2021). Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telematics Inform. 59:101556. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101556

Maton, K. I. (1989). The stress-buffering role of spiritual support: cross-sectional and prospective investigations. J. Sci. Study Relig. 28, 310–323. doi: 10.2307/1386742

Matud, M. P., Bethencourt, J. M., and Ibáñez, I. (2014). Relevance of gender roles in life satisfaction in adult people. Personal. Individ. Differ. 70, 206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.046

McIntosh, D. N. (1995). Religion-as-schema, with implications for the relation between religion and coping. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 5, 1–16. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr0501_1

Mehlsen, M., Kirkegaard Thomsen, D., Viidik, A., Olesen, F., and Zachariae, R. (2005). Cognitive processes involved in the evaluation of life satisfaction: implications for well-being. Aging Ment. Health 9, 281–290. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331310236a

Minner, M. (2009). The impact of child-parent attachment, attachment to god and religious orientation on psychology adjustment. J. Psychol. Theol. 37, 114–124. doi: 10.1177/009164710903700203

Mohammadpour, F., Yousefi, M. A., and Naderi, H. (1985). The relationship between perception of god and feeling of loneliness and dysfunctional attitude in the university students. İnt. J. Human. Cult. Stud. 1, 2102–2110. doi: 10.4314/JFAS.V8I2S.83

Moore, D., and Schultz, N. R. (1983). Loneliness at adolescence: correlates, attributions, and coping. J. Youth Adolesc. 12, 95–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02088307

Muhammad, T., Pai, M., Afsal, K., Saravanakumar, P., and Irshad, C. V. (2023). The association between loneliness and life satisfaction: examining spirituality, religiosity, and religious participation as moderators. BMC Geriatr. 23:301. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04017-7

Nangle, D. W., Erdley, C. A., Newman, J. E., Mason, C. A., and Carpenter, E. M. (2003). Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: interactive influences on children’s loneliness and depression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 32, 546–555. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7

Nie, Q., Tian, L., and Huebner, E. S. (2020). Relations among family dysfunction, loneliness and life satisfaction in chinese children: a longitudinal mediation model. Child Indic. Res. 13, 839–862. doi: 10.1007/s12187-019-09650-6

Nilima, N., Kaushik, S., Tiwary, B., and Pandey, P. K. (2021). Psycho-social factors associated with the nationwide lockdown in India during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health 9, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.06.010

Onal, O., Evcil, F. Y., Dogan, E., Develi, M., Uskun, E., and Kisioglu, A. N. (2022). The effect of loneliness and perceived social support among older adults on their life satisfaction and quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Gerontol. 48, 331–343. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2022.2040206

Ozben, S. (2013). Social skills, life satisfaction, and loneliness in Turkish university students. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 41, 203–213. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2013.41.2.203

Ozmen, C. B., Brelsford, G. M., and Danieu, C. R. (2018). Political affiliation, spirituality, and religiosity: links to emerging adults’ life satisfaction and optimism. J. Relig. Health 57, 622–635. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0477-y

Peplau, L. A., and Perlman, D. (1982). Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley & Sons Incorporated.

Perlman, D. (2004). European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Can. J. Aging 23, 181–188. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0025

Peterson, C., Park, N., and Seligman, M. E. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 6, 25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

Plouffe, R. A., and Tremblay, P. F. (2017). The relationship between income and life satisfaction: does religiosity play a role? Personal. Individ. Differ. 109, 67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.044

Ranta, M., Chow, A., and Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Trajectories of life satisfaction and the financial situation in the transition to adulthood. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 4, 57–77. doi: 10.14301/llcs.v4i1.216

Røysamb, E., Tambs, K., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Neale, M. C., and Harris, J. R. (2003). Happiness and health: environmental and genetic contributions to the relationship between subjective wellbeing, perceived health, and somatic illness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 1136–1146. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1136

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., and Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. J. Pers. Assess. 42, 290–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11