94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 03 February 2025

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1530289

This article is part of the Research Topic Enhancing Learning through Cognitive and Social Inclusion Practices in Education View all 5 articles

Introduction: This study investigates the influence of parental burnout on the academic achievement of middle school students, as well as the mediating role of academic self-efficacy and the moderating role of middle school students’ gender and parental gender.

Methods: Utilizing a parent-child matched-pair design, a questionnaire survey was conducted with 738 middle school students and their parents (either fathers or mothers).

Results: The findings revealed that: (1) parental burnout significantly and negatively predicted middle school students’ academic achievement; (2) academic self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between parental burnout and middle school students’ academic achievement; and (3) the gender of middle school students moderated the initial segment of this mediating effect, while parental gender did not significantly moderate the relationship, indicating that the significant negative predictive effect of parental burnout on academic self-efficacy was evident only among female middle students.

Discussion: These results not only enhance our understanding of the mechanisms and conditions under which parental burnout impacts middle school students’ academic achievement, but also have important implications for improving middle school students’ academic self-efficacy and overall academic performance.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the country’s birth policy has evolved from “one couple, one child with exceptions” to “universal two-child” and now to “universal three-child.” While the relaxation of birth control policies has created more opportunities for reproduction, an increasing number of families remain hesitant to have additional children. Parenting issues have become a greater concern than the decision to expand family size (Zhong and Guo, 2017). It is widely acknowledged that the presence or arrival of children can bring immense joy and fulfillment to parents, but it also entails increased labor and sacrifice (Xu et al., 2018). Particularly when there is an imbalance between parenting demands and available resources, the phenomenon of parental burnout becomes highly prevalent (Mikolajczak et al., 2020). By definition, parental burnout shares similarities with occupational burnout and general burnout in that all are syndromes resulting from exposure to prolonged stress. However, it differs in that parental burnout arises specifically from the unique context of child-rearing (Isabelle et al., 2017). Parental burnout refers to a set of negative symptoms experienced by parents due to prolonged child-rearing stress. These symptoms include feelings of exhaustion in their parental role, a sense of discrepancy when comparing their current self to their former self as a parent, boredom with the parental role, and emotional distancing from their children (Roskam et al., 2018). Surveys indicate that the incidence of parental burnout in China ranges from 10 to 14% (Wang et al., 2021b). The negative consequences of general burnout are not only directed at the parents themselves but may also spill over to others. Due to the interactive nature of parenting, children are often the greater victims of general burnout (Cheng et al., 2021). Previous research has found that parental burnout is negatively correlated with children’s academic achievement (Hong et al., 2022). However, the underlying mechanisms of this relationship remain unclear. Therefore, this study aims to explore the internal mechanisms through which parental burnout affects children’s academic performance.

Ecological systems theory posits that the family functions as a microsystem that directly and profoundly influences individual development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). A positive family environment fosters individual development, whereas a detrimental environment has the opposite effect. Previous studies indicate that supportive parenting fosters emotional intelligence and adaptability in children, while also enhancing academic achievement by creating a learning environment characterized by open communication, encouragement, and shared decision-making. This, in turn, helps break the cycle of intergenerational poverty and promotes sustainable development (Ali et al., 2023; Tripon, 2024). Parental burnout, a family environmental factor that reflects negative emotions or attitudes related to parenting (Wang and Su, 2021), has been negatively correlated with children’s academic achievement (Hong et al., 2022). Parental burnout can result in a lack of parental fulfillment and self-doubt regarding parenting abilities (Mikolajczak et al., 2018), making it difficult to create an ideal family atmosphere. However, the family environment plays a more significant role than teacher-student relationships or classroom atmosphere in influencing adolescents’ academic achievement (Lei et al., 2012). Conversely, parents experiencing burnout are more likely to neglect or reject their children’s physiological and emotional needs (Roskam et al., 2017), and even increase the frequency of violent behaviors toward their children (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). Such negative and punitive parenting behaviors increase the risk of academic burnout in children (Luo et al., 2016), ultimately leading to a decline in academic performance. Moreover, parents severely affected by burnout find it difficult to provide not only basic parenting services but also additional resources for child-rearing, which may decrease their involvement in their children’s education. Negative parental involvement in education can also reduce children’s motivation to learn, thereby hindering their academic achievement (Yin et al., 2022). However, it is important to note that previous studies have primarily focused on elementary school students, while the rapid changes in the physical and psychological development of middle school students place higher demands on parental behavior (Wang et al., 2021b). Therefore, this study examines the impact of parental burnout on the academic achievement of middle school students.

Social cognitive theory posits that both environmental factors and individual characteristics (such as beliefs about one’s ability to complete specific tasks) jointly influence behavioral outcomes (Bandura, 1997). According to this theory, parental burnout, as an environmental factor, may affect middle school students’ academic achievement by influencing their academic self-efficacy. Academic self-efficacy refers to an individual’s judgment and confidence in their ability to complete academic tasks (Wang et al., 2016). As a specific manifestation of self-efficacy in the academic domain (Xiao and Liu, 2017), children’s academic self-efficacy is closely related to parental upbringing styles (Tang et al., 2014). Parenting style is a comprehensive concept that encompasses parents’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in child-rearing (Zhang and Chen, 2013). Parenting styles are generally categorized into positive parenting (e.g., emotional warmth) and negative parenting (e.g., neglect or rejection), based on their impact on children’s positive development (Liu et al., 2021). Positive parenting creates a warm, supportive family environment and offers encouraging verbal persuasion, fostering higher levels of academic self-efficacy in children (Anna et al., 2017). Conversely, negative parenting often results in increased negative emotional arousal and experiences of failure, hindering the development of academic self-efficacy in children (Zhang and Ke, 2021). Research indicates that parents experiencing burnout often lose the patience necessary for effective child-rearing, attempt to evade their parental responsibilities, and neglect or reject their children’s requests for care (Cheng et al., 2021). Such neglect and rejection lower children’s self-confidence and impair their recognition of their own abilities (Fan and Williams, 2010). Moreover, parental burnout may affect children’s academic self-efficacy. Additionally, academic self-efficacy is a sensitive predictor of students’ academic performance (Lei et al., 2015). Yi et al. (2017) conducted a qualitative review and directional analysis of previous literature using meta-integration techniques, finding that among six factors (motivation, academic self-efficacy, achievement goal orientation, parenting style, teacher-student relationships, peer relationships), academic self-efficacy showed the highest correlation with students’ academic performance. Therefore, based on the above, academic self-efficacy may serve as a bridge between parental burnout and middle school students’ academic achievement.

Resource dilution theory posits that as parenting stress increases, parents may become more cautious in allocating limited time, energy, and other resources (Blake, 1981). Consequently, parents who experience burnout due to excessive exposure to parenting stress may be able to provide only limited support and resources for their children. Additionally, patriarchal cultural norms contribute to a phenomenon known as “son preference” in China (Wu et al., 2013). Consequently, when resources are scarce, parents experiencing burnout may be more likely to favor their sons over their daughters, sacrificing the well-being of their daughters (Hannum et al., 2009). This results in less educational support, lower educational expectations, and reduced educational involvement for daughters (Liu et al., 2022), which is closely related to their academic self-efficacy (Zhou et al., 2023). On the other hand, girls exhibit higher empathy than boys (Zhang et al., 2020), making them more likely to detect their parents’ burnout early (e.g., low efficacy in parenting activities, disappointment in the parental role, emotional distance from children) and thus more affected by this imbalanced state. Research shows that individuals who grow up in environments characterized by parental neglect or indifference are less likely to recognize their own abilities (Zhang, 2022). Thus, the impact of parental burnout on middle school students’ academic self-efficacy may vary depending on the gender of the students. Furthermore, studies have shown that, compared to fathers, mothers are the primary caregivers in child-rearing activities (Cheng et al., 2021). Mothers tend to invest more energy in parenting and experience higher levels of parenting burnout (Norberg, 2010). As burnout increases, parents are more likely to exhibit negative parenting behaviors, such as neglect, rejection, or violence (Mikolajczak et al., 2018; Mikolajczak et al., 2019), which, in turn, affects their children’s academic self-efficacy (Tang et al., 2014). Therefore, the effect of parental burnout on middle school students’ academic self-efficacy may also differ based on the parent’s gender.

Building on previous research and relevant theories, the present study aims to construct a moderated mediation model (see Figure 1) to examine the impact of parental burnout on middle school students’ academic achievement, as well as the mediating role of academic self-efficacy and the moderating effects of middle school students’ gender and parental gender. The specific hypotheses of this study are as follows:

H1: Parental burnout negatively predicts middle school students’ academic achievement.

H2: Academic self-efficacy mediates the relationship between parental burnout and middle school students’ academic achievement.

H3: Both the gender of middle school students and that of their parents moderate the effect of parental burnout on middle school students’ academic self-efficacy.

Participants in this study included students and their parents (i.e., either the father or mother) from a secondary school in Hunan, China. This investigation received the approval from the authors’ University Ethics Committee. Prior to data collection, the examiners (i.e., the head teacher of class who had undergone rigorous training in advance) introduced the instructions to participants and explained the principle of confidentiality. Participants were also informed that completing the survey was optional and that they could withdraw the investigation at any time. Once informed consent was obtained, participants were invited to fill out the questionnaires. Parents completed questionnaires during the parent-teacher meeting, while students completed theirs during the self-study class on the same day.

Based on Guo and Huang (2022), the sample size was calculated using the following formula (N = sample size, Z = statistical value, E = margin of error, P = probability value). In this study, Z = 1.96 (95% confidence level), E = 5%, P = 12.20% (based on previous research indicating that the incidence of parental burnout in China ranges from 10.44 to 13.95%; Wang et al., 2021b). The minimum required sample size for this study was therefore determined to be 165. The collected data were first matched based on the names, classes, and genders of both parents’ reports on their children and the students’ self-reports. Only the matched data were retained. Subsequently, questionnaires with missing answers or those exhibiting patterned responses were further excluded. Ultimately, we obtained valid paired data for 738 parent–child dyads, indicating a sufficient sample size for the study. Among the parent data, 184 were fathers (24.9%) and 554 were mothers (75.1%), with an average age of 43.21 ± 4.37 years. The sample included 310 single-child families (42.0%), 389 two-child families (52.7%), 35 three-child families (4.7%), and 4 four-child families (0.5%). Among the children, there were 239 males (32.4%) and 499 females (67.6%), with 309 attending junior high school (41.9%) and 429 attending senior high school (58.1%), and an average age of 14.87 ± 1.47 years.

The parental burnout scale developed by Roskam et al. (2018) was utilized. This scale consists of 23 items across four dimensions: exhaustion in the parental role (e.g., “I really do not know how to raise my children anymore”), comparison with past parental roles (e.g., “To play the role of a good parent, I am exhausted”), boredom with the parental role (e.g., “I do not want to take on the role of a parent again”), and emotional distancing from the child (e.g., “I can no longer be a good parent”). Items are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from “never” to “every day,” with higher scores indicating higher levels of parental burnout. The scale has been widely used in different cultural contexts (e.g., Mikolajczak et al., 2019; Roskam et al., 2021; Sorkkila and Aunola, 2020), and the Chinese version has been validated with good reliability (Yang et al., 2021). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the parental burnout scale was 0.91.

The academic self-efficacy Scale developed by Liang (2000) was used. This scale includes 22 items across two dimensions: academic ability self-efficacy (e.g., “I believe I have the ability to achieve good grades in my studies”) and academic behavioral self-efficacy (e.g., “I often cannot accurately summarize the main points of what I read”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with higher scores indicating stronger academic self-efficacy. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous research (Ye et al., 2017). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the Academic Self-Efficacy Scale was 0.90.

To assess students’ academic achievement, we used subject grades as the evaluation indicator. Since Chinese, Math, and English are considered core subjects in China’s education system, previous studies have primarily assessed students’ academic achievement based on the grades of these core subjects (Lei et al., 2015; Qiao et al., 2013). Following this practice, the participants’ scores in Chinese, Math, and English from the monthly exams conducted during data collection were obtained through communication with the class teachers. These scores were standardized within the grade level. The overall academic achievement index was calculated as the average of the standardized scores in the three subjects (Lei et al., 2015).

We also collected relevant demographic information from both parents and children. Specifically, parents were asked to report their gender, age, number of children, as well as their children’s names, class, and gender. Students were asked to report their name, class, gender, and age. These demographic variables were collected at the beginning of the formal testing.

Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, common method bias testing, and model testing for mediation and moderation effects were performed using SPSS 26.0 and PROCESS v3.5 (Hayes, 2013).

Given that this study utilized a questionnaire method, there was a potential risk of common method bias. To mitigate the influence of this bias on the research outcomes, procedural controls were implemented, including the use of highly reliable and valid measurement tools and emphasizing confidentiality. Statistically, Harman’s single-factor test was employed to assess common method bias. The results indicated that there were 8 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 25.51%, which is below the critical value of 40%. This suggests that the issue of common method bias in this study is not severe (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients for the variables. The Pearson correlation analysis revealed that parental burnout was significantly negatively correlated with academic self-efficacy (r = −0.19, p < 0.001) and academic achievement (r = −0.15, p < 0.001). Academic self-efficacy was positively correlated with academic achievement (r = 0.26, p < 0.001). Additionally, the gender of middle school students was positively correlated with parental burnout (r = 0.09, p < 0.05) and academic self-efficacy (r = 0.12, p < 0.01), but negatively correlated with academic achievement (r = −0.08, p < 0.05). However, neither the gender of parents nor the number of children exhibited significant correlations with these variables (r = −0.04 ~ 0.05, p > 0.05).

Testing a moderated mediation model involves two steps: first, examining a simple mediation model, and second, examining a moderated mediation model (Wen and Ye, 2014). For this study, bias-corrected non-parametric percentile Bootstrap was used for testing, with 5,000 resamples to compute the 95% confidence interval. Before conducting the mediation and moderated mediation analyses, all variables were standardized.

Examining the mediating role of academic self-efficacy (Model 4). The results showed that parental burnout significantly negatively predicted both academic achievement (c = −0.12, p < 0.001) and academic self-efficacy (a = −0.19, p < 0.001). When both parental burnout and academic self-efficacy were entered into the regression equation, parental burnout continued to significantly negatively predicted academic achievement (c’ = −0.09, p < 0.01), while academic self-efficacy significantly positively predicted academic achievement (b = 0.19, p < 0.001). The indirect effect (ab) was −0.04, with Boot SE = 0.01, and the 95% confidence interval was [−0.07, −0.01], which does not include zero. This indicates that academic self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between parental burnout and academic achievement. The proportion of the indirect effect (ab) relative to the total effect (c) was −0.04/−0.12 = 33.33%.

Including the gender of middle school students and parents in the model to analyze the moderated mediation effect (model 9). The results (see Figure 2) showed that parental burnout (β = −0.34, p < 0.001) and the gender of middle school students (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) significantly predicted academic self-efficacy, and the interaction term between parental burnout and the gender of middle school students also significantly predicted academic self-efficacy (β = 0.29, p < 0.001). However, the gender of parents (β = −0.03, p > 0.05) did not significantly predict academic self-efficacy, nor did the interaction between parental burnout and the gender of parents did not significantly predict academic self-efficacy (β = −0.04, p > 0.05). Both academic self-efficacy (β = 0.19, p < 0.001) and parental burnout (β = −0.09, p < 0.01) significantly predicted academic achievement. This suggests that gender of middle school student moderates the first part of the mediation pathway (parental burnout → academic self-efficacy → academic achievement), whereas the gender of parents does not moderate this pathway.

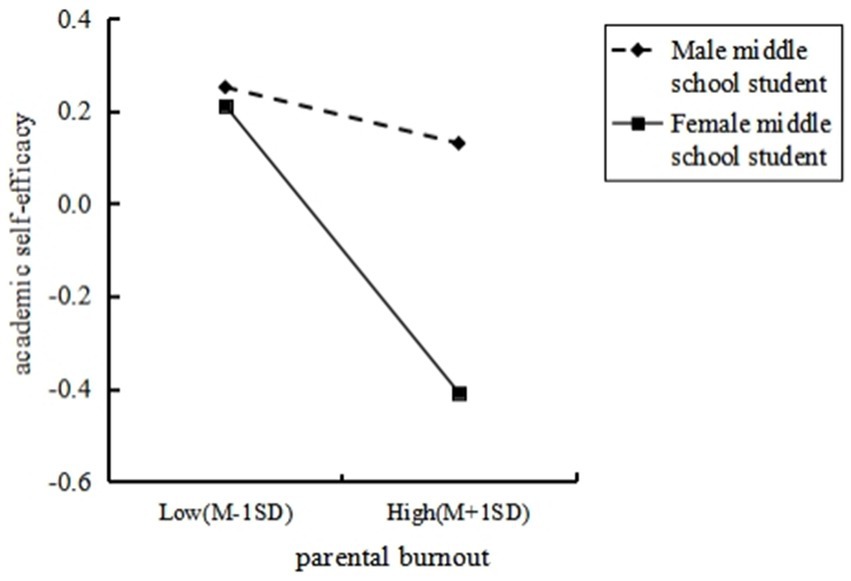

To further test the moderating effect, the interaction plot for the gender of middle school students (male middle school student = 1, female middle school student = 0) was created (see Figure 3). The slope of the lines in the plot reflects the influence of parental burnout on academic self-efficacy. Simple slopes analysis showed that for female middle school students, as parental burnout increased, their academic self-efficacy significantly decreased (bsimple = −0.34, t = −6.52, p < 0.001). For male middle school students, however, parental burnout did not significantly predict their academic self-efficacy (bsimple = −0.07, t = −1.29, p > 0.05).

Figure 3. The moderating role of middle school students’ gender on the relationship between parental burnout and academic self-efficacy.

This study elucidates the relationship between parental burnout and middle school students’ academic achievement, as well as the mechanisms through which this relationship operates. Specifically, it explains how parental burnout affects academic performance—namely, through the mediating role of academic self-efficacy—and when it affects performance, highlighting gender differences in the mediating effect that is evident only among female middle school students.

The study found that parental burnout significantly negatively predicts middle school students’ academic achievement, consistent with findings from studies involving elementary school students (Hong et al., 2022). Parents experiencing burnout often lack emotional engagement with their children and may resort to punitive parenting behaviors (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). When middle school students face academic challenges, burned-out parents may either ignore their requests for help or resort to punitive discipline. Both of these negative parenting practices can undermine students’ motivation for academic progress and adversely affect their academic performance (Wang et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2022). Therefore, parents should recognize that an imbalanced parenting state is closely linked to negative academic outcomes for middle school students. While parental stress is entirely normal, it is crucial for parents to manage and alleviate this stress, keeping it within manageable limits to create a supportive environment for their children’s development (Yu, 2021).

Furthermore, the study found that academic self-efficacy plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between parental burnout and middle school students’ academic performance. This result supports the social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997). As the level of parental burnout increases, parents’ interest and motivation in their children’s education decline (Yu, 2021), leading to reduced parental involvement. When parents cease to assist with homework or fail to communicate their educational expectations, this directly lowers children’s academic self-efficacy (Cross et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2017). Additionally, academic self-efficacy, as a specific manifestation of general self-efficacy in the academic domain (Xiao and Liu, 2017), indicates that students with low academic self-efficacy tend to view academic tasks, difficulties, and setbacks as obstacles and are less likely to adopt problem-focused coping strategies when faced with academic pressure (Denovan and Macaskill, 2017). Consequently, they are less likely to perform well on exams (Lei et al., 2015). Thus, maintaining a balanced parenting state can provide stronger support for children’s academic success. Positive educational interactions can help children recognize their learning abilities, leading to better academic outcomes.

The study also found that the gender of middle school students moderates the first half of the mediating effect of academic self-efficacy in the relationship between parental burnout and academic performance. Specifically, in female middle school students, increased parental burnout leads to a decrease in academic self-efficacy, which in turn hinders their academic performance; this indirect effect is not observed in male middle school students. Parents experiencing burnout often reduce the parenting resources available to their children (Roskam et al., 2017), particularly the educational support that children expect. Moreover, compared to boys, parents may assign lower educational expectations and involvement to girls due to the perceived lower returns on educational investment for girls in the labor market (Liu et al., 2022). Girls who perceive a reduction in parental educational involvement may experience a decrease in their recognition of their own learning behaviors and capabilities (Liu et al., 2018), which can negatively influence their academic performance. It is also important to note that the insignificant negative predictive effect of parental burnout on academic self-efficacy in male middle school students does not necessarily imply that this effect is absent in this group. There may be cumulative effects, and future research should employ longitudinal designs to further validate these findings. Additionally, the study found that parental burnout’s effect on students’ academic self-efficacy was not moderated by parental gender. This could be related to changes in family division of labor. As societal norms evolve, the traditional “male breadwinner, female homemaker” model is gradually diminishing, with more women entering the workforce and more men participating in parenting activities (Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021a). This shared parenting responsibility may have balanced parental burnout between fathers and mothers (Delvecchio et al., 2015), rendering the effect of parental burnout on students’ academic self-efficacy independent of parental gender.

This study constructed a moderated mediation model to explore the relationship between parental burnout and the academic achievement of secondary school students, along with the mediating role of academic self-efficacy and the moderating roles of student and parental gender. The findings provide theoretical guidance and empirical support for enhancing secondary school students’ academic achievement. On one hand, intervening in parental burnout is a crucial starting point. Some researchers suggest that strengthening mutual support and cooperation among family members can effectively alleviate parental burnout (Yu, 2021). This includes shared family parenting responsibilities (Lin et al., 2023), joint parenting by grandparents and parents (Yu, 2021), and fostering children’s self-management abilities to reduce dependence on their parents (Li et al., 2024). Additionally, schools and communities could offer training to improve parents’ time management skills, guide them in setting realistic parenting goals, developing scientific parenting plans, prioritizing tasks, and reflecting on their parenting behaviors (Huang and Zhang, 2001), which could enhance the quality of family parenting and reduce parental burnout. Moreover, establishing a family-school-community collaborative education mechanism, optimizing national parental welfare policies, and encouraging companies to develop family-friendly policies (Ann and Harrington, 2007) can also reduce workplace stress and parental burnout. On the other hand, for students experiencing parental burnout, schools should focus on enhancing their academic self-efficacy, particularly among female students. Strategies such as providing opportunities for students to experience success, promoting role models, offering timely positive feedback, focusing on study skills, creating a supportive learning environment, implementing rational attribution training, and encouraging extracurricular physical activities (Bandura, 1997; Mcauley et al., 2000; Olivier et al., 2019; Zhu, 2012) can all boost students’ academic confidence.

At the same time, this study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to make causal inferences. Future studies could explore this relationship through longitudinal tracking designs. Second, the data used in this study were all self-reported by the participants, which may have introduced response biases. For the variable of parental burnout, future research could benefit from incorporating both parent and child reports to mitigate response bias and improve the stability of the measurements (Song, 2023). Third, the participants selected for this study were only middle school students and their parents from a specific region, without involving other areas. Future studies should examine middle school students and their parents from a broader geographic range. Forth, this study only considered the number of children as a control variable, while factors such as family socioeconomic status and family structure are also important influences on parental burnout (Baxter et al., 2014). Finally, this study only explored a limited set of mediating and moderating variables in the relationship between parental burnout and students’ academic achievement. Future research could further examine other potential mediators and moderators, such as parental involvement, teacher support, and students’ emotions and motivation.

Academic self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between parental burnout and middle school students’ academic achievement. Furthermore, this mediating effect is moderated by the gender of the middle school students but not by the gender of the parents. Specifically, the negative influence of parental burnout on academic self-efficacy is significant only among female middle school students.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Academic Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

LP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HC: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ML: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WF: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by the Graduate Research and Innovation Project of Hunan Province (Grant No. CX20240507).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ali, N., Ullah, A., Khan, A. M., Khan, Y., Ali, S., Khan, A., et al. (2023). Academic performance of children in relation to gender, parenting styles, and socioeconomic status: what attributes are important. PLoS One 18:286823:e0286823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286823

Ann, B., and Harrington, M. (2007). Family caregivers: a shadow workforce in the geriatric health care system? J. Health Polit. Policy Law 32, 1005–1041. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2007-040

Anna, L., María, C. R., and Elisabeth, M. (2017). Parenting, peer relationships, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement: direct and mediating effects. Front. Psychol. 8, 2120–2131. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02120

Baxter, L. A., Braithwaite, D. O., and Bryant, L. (2014). Stepchildren’s perceptions of the contradictions in communication with stepparents. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 21, 447–467. doi: 10.1177/0265407504044841

Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography 18, 421–442. doi: 10.2307/2060941

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cheng, H. B., Liu, X., Li, Y. M., and Li, Y. X. (2021). Is parenting a happy experience? A review of parenting burnout. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 37, 146–152. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2021.01.18

Cross, F. L., Marchand, A. D., Medina, M., and Villafuerte, A. R. D. (2019). Academic socialization, parental educational expectations, and academic self-efficacy among Latino adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 56, 483–496. doi: 10.1002/pits.22239

Delvecchio, E., Sciandra, A., Finos, L., Mazzeschi, C., and Riso, D. D. (2015). The role of co-parenting alliance as a mediator between trait anxiety, family system maladjustment, and parenting stress in a sample of non-clinical Italian parents. Front. Psychol. 6:1177. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01177

Denovan, A., and Macaskill, A. (2017). Stress and subjective well-being among first-year UK undergraduate students. J. Happiness Stud. 18, 505–525. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9736-y

Fan, W., and Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educ. Psychol. 30, 53–74. doi: 10.1080/01443410903353302

Gao, W., Zhu, J. H., and Fang, Z. (2020). The effect of father involvement in parenting on elementary school students' aggressive behavior: the partial mediating effect of maternal parenting stress. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 36, 84–93. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2020.01.10

Guo, X. M., and Huang, J. W. (2022). The relationship between childhood trauma, school bullying experiences, social anxiety, and life satisfaction among college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 36, 810–816.

Hannum, E., Kong, P., and Zhang, Y. P. (2009). Family sources of educational gender inequality in rural China: a critical assessment. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 29, 474–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.04.007

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hong, V. T., An, N. H., Thao, T. T., Thao, L. N., and Thanh, N. M. (2022). Behavior problems reduce academic outcomes among primary students: a moderated mediation of parental burnout and parents’ self-compassion. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2022, 27–42. doi: 10.1002/cad.20482

Huang, X. T., and Zhang, Z. J. (2001). On personal time management tendencies. Psychol. Sci. 5, 516–518. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2001.05.002

Isabelle, R., Marie, E. R., and Mora, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Front. Psychol. 8, 1–12.

Lei, H., Liu, Y. L., and Tian, L. (2012). The relationship between family environment, classroom environment, and high school students' academic achievement: the mediating role of academic diligence. Shanghai Educ. Res. 4, 17–20. doi: 10.16194/j.cnki.31-1059/g4.2012.04.006

Lei, H., Xu, G. G., Shao, C. Y., and Sang, J. Y. (2015). The relationship between teacher caring behavior and students' academic achievement: the mediating role of learning self-efficacy. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 31, 188–197. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.02.08

Liang, Y. S. (2000). A study on achievement goals, attribution styles, and academic self-efficacy among college students (master). Wuhan: Central China Normal University.

Li, S., Zhang, S. X., and Yu, G. L. (2024). The impact of parental burnout on the mental health of primary and secondary school students: evidence and educational strategies. Educ. Sci. Res. 10, 12–19.

Lin, L. Y., Xiang, M. H., Wu, Y. T., and Lu, X. L. (2023). The impact of parental burnout on parent-child relationships: the chain mediation effect of marriage quality and co-parenting. Psychol. Behav. Res. 21, 807–814.

Liu, T., Chen, X. M., Lu, X. R., and Yang, Y. (2021). The impact of positive parenting on coping strategies in middle school students: the mediating roles of social support and self-efficacy. Psychol. Behav. Res. 19, 507–514.

Liu, C. L., Huo, Z. Z., and Liang, X. (2018). The impact of parental educational involvement on elementary school students' academic engagement: the chain mediation effect of perceived maternal educational involvement and academic self-efficacy. Psychol. Res. 11, 472–478.

Liu, C. H., Liu, S. J., Guo, X. L., and Luo, L. (2022). The relationship between maternal son preference and parent-child communication: the moderating effect of child's gender. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 38, 64–71. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2022.01.08

Luo, Y., Chen, A. H., and Wang, Z. H. (2016). The relationship between parenting styles and academic burnout in middle school students: the mediating role of self-concept. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 32, 65–72. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.01.09

McAuley, E., Blissmer, B., Katula, J., Duncan, T. E., and Mihalko, S. L. (2000). Physical activity, self-esteem, and self-efficacy relationships in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 22, 131–139. doi: 10.1007/BF02895777

Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., and Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse Negl. 80, 134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.025

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., and Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: what is it, and why does it matter? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 7, 1319–1329. doi: 10.1177/2167702619858430

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., Stinglhamber, F., Lindahl Norberg, A., and Roskam, I. (2020). Is parental burnout distinct from job burnout and depressive symptoms? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 8, 673–689. doi: 10.1177/2167702620917447

Norberg, A. L. (2010). Parents of children surviving a brain tumor: burnout and the perceived disease-related influence on everyday life. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 32, e285–e289. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e7dda6

Olivier, E., Archambault, I., De Clercq, M., and Galand, B. (2019). Student self-efficacy, classroom engagement, and academic achievement: comparing three theoretical frameworks. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 326–340. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0952-0

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Qiao, N., Zhang, J. H., Liu, G. R., and Lin, C. D. (2013). The impact of family socioeconomic status and parental involvement on middle school students' academic achievement: the moderating role of teacher support. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 29, 507–514. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.05.006

Roskam, I., Aguiar, J., Akgun, E., Arikan, G., Artavia, M., Avalosse, H., et al. (2021). Parental burnout around the globe: a 42-country study. Affect. Sci. 2, 58–79. doi: 10.1007/s42761-020-00028-4

Roskam, I., Raes, M. E., and Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Front. Psychol. 8, 163. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00163

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., and Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: the parental burnout assessment (PBA). Front. Psychol. 9:758. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758

Song, Y. (2023). Adolescents' perceived parental burnout and its impact on risky behaviors: The mediating role of parent-child conflict and the moderating role of teacher-student relationships (master). Dalian: Liaoning Normal University.

Sorkkila, M., and Aunola, K. (2020). Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: the role of socially prescribed perfectionism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 648–659. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01607-1

Tang, K. Q., Deng, X. Q., Fan, F., Long, K., Wang, H., and Zhang, Y. (2014). Parenting styles and academic procrastination: the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 22, 889–892. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.05.076

Tripon, C. (2024). Nurturing sustainable development: the interplay of parenting styles and SDGs in children’s development. Children 11:695. doi: 10.3390/children11060695

Wang, W., Lei, L., and Wang, X. C. (2016). The effect of college students' proactive personality on academic performance: the mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and learning adaptation. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 32, 579–586. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.05.08

Wang, Q. C., and Su, Y. J. (2021). The relationship between parental burnout and adolescents' prosocial tendencies: The role of empathy. Proceed. Natl. Psychol. Acad. Conf. 1, 66–67. doi: 10.26914/c.cnkihy.2021.041837

Wang, W., Wang, S. N., Cheng, H. B., Wang, Y. H., and Li, Y. X. (2021a). The mediating role of paternal parenting burnout between parenting stress and adolescents' mental health. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 29, 858–861. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.04.040

Wang, W., Wang, S. N., Cheng, H. B., Wang, Y. H., and Li, Y. X. (2021b). The revision of the Chinese version of the brief parenting burnout scale. Chin. J. Mental Health 35, 941–946.

Wang, M. Z., Wang, J., Wang, B. Y., Qu, X. Q., and Xin, F. K. (2020). Harsh parenting and adolescents' academic achievement: a moderated mediation analysis. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 36, 67–76. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2020.01.08

Wen, Z. L., and Ye, B. J. (2014). Mediation effect analysis: methods and model development. Psychol. Sci. Adv. 22, 731–745. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00731

Williams, K., Swift, J., Williams, H., and Van Daal, V. (2017). Raising children’s self-efficacy through parental involvement in homework. Educ. Res. 59, 316–334. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2017.1344558

Wu, B. P., Zhu, X. Q., and Zhang, L. (2013). The individual differences in grandparental investment: An evolutionary psychology perspective. Psychol. Sci. Adv. 21, 2082–2090. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2013.02082

Xiao, L. F., and Liu, J. (2017). The impact of family socioeconomic status on students' academic achievement: the mediating roles of parental involvement and academic self-efficacy. Educ. Sci. Res. 12, 61–66.

Xu, H. C., Cui, B. Y., and Zhang, W. T. (2018). Are parents happier? Psychol. Sci. Adv. 26, 538–548. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2018.00538

Yang, B., Chen, B. B., Qu, Y., and Zhu, Y. (2021). Impacts of parental burnout on Chinese youth’s mental health: the role of parents’ autonomy support and emotion regulation. J. Youth Adolesc. 50, 1679–1692. doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01450-y

Ye, B. J., Fu, H. H., Yang, Q., You, Y. Y., Lei, X., and Chen, J. W. (2017). The impact of teacher caring behavior on adolescent internet addiction: a chain mediation effect of perceived social support and academic self-efficacy. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 25, 1168–1170, 1174. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki

Yi, F., Guo, Y., Yu, Z., and Xu, S. (2017). Meta-analysis of the main factors influencing academic achievement of primary and secondary school students. Psychol. Explor. 37, 140–148.

Yin, X. Y., Liu, M., and Lin, R. Z. (2022). The impact of parental psychological distress on adolescent academic burnout: the mediating roles of parental educational involvement and parent-child closeness. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 30:605–608, 613. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2022.03.021

Yu, G. L. (2021). Parental burnout in family education: a perspective from mental health. Tsinghua J. Educ. Res. 42, 21–28. doi: 10.14138/j.1001-4519.2021.06.002108

Zhang, Y. H. (2022). The impact of parental burnout on academic achievement in upper elementary school students: The mediating roles of family environment and self-efficacy (master). Dalian: Liaoning Normal University.

Zhang, M., and Chen, Y. H. (2013). Parenting styles and procrastination: the mediating role of perfectionism. Psychol. Behav. Res. 11, 245–250.

Zhang, J., and Ke, B. (2021). The impact of parenting styles on middle school students' academic self-efficacy: the mediating role of goal orientation. J. Jimei Univ. 22, 25–30.

Zhang, Y. W., Pang, F. F., An, J. B., and Guan, R. Y. (2020). The relationship between empathy and interpersonal difficulties in middle school students and gender differences. Chin. J. Mental Health 34, 337–341.

Zhong, X. H., and Guo, W. Q. (2017). Policy change in population issues: from child-rearing to fertility—grandparental care and childrearing in middle-class families under the “two-child policy.”. Explor. Controversy 7:96.

Zhou, X. H., Liu, Y. X., Chen, X., and Wang, Y. J. (2023). The influence of parental educational involvement on middle school students' life satisfaction: a chain mediation effect of interpersonal relationships at school and academic self-efficacy. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 39, 691–701. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2023.05.10

Keywords: parental burnout, academic achievement, academic self-efficacy, gender, middle school students, parental gender

Citation: Peng L, Chen H, Peng J, Liang W, Li M and Fu W (2025) The influence of parental burnout on middle school students’ academic achievement: moderated mediation effect. Front. Psychol. 16:1530289. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1530289

Received: 18 November 2024; Accepted: 20 January 2025;

Published: 03 February 2025.

Edited by:

Pedro Jesús Ruiz-Montero, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Cristina Tripon, Polytechnic University of Bucharest, RomaniaCopyright © 2025 Peng, Chen, Peng, Liang, Li and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Liang, MzQyOTUwNTY1QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.