94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 16 April 2025

Sec. Media Psychology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1520066

This article is part of the Research TopicSocial Interaction in Cyberspace: Online Gaming, Social Media, and Mental HealthView all articles

Introduction: In contemporary society, individuals are commonly exposed to multiple pressures, under which emotional disorders occur frequently. Especially the upward trend of depressive symptoms among the young population constitutes a non-negligible public health challenge. As social media is increasingly integrated into daily life, individuals’ emotional experiences strongly connect with online interactions. Thus, it is essential to investigate the relationship between the social media usage behavior of young people and their mental health conditions.

Methods: This study conducted an online survey involving 405 college students using the DDI (Distress Disclosure Index), INCOM (Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure), and CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). It employed a moderated mediation model to explore the connection between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms and the potential roles of social comparison and gender.

Results: The results indicate the following: (1) Distress disclosure on social media is associated with depressive symptoms; (2) Social comparison mediates the relationship between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms among college students; (3) Gender moderates the effect of distress disclosure on social media regarding social comparison, with a more pronounced moderation effect observed in male participants.

Discussion: The findings of this study underscores the importance of adopting appropriate strategies for disclosing distress, fostering healthy tendencies toward social comparison, and recognizing gender differences in mitigating depressive symptoms among young adults.

The rapid acceleration of life pace in contemporary society has profoundly reshaped individuals’ emotional perceptions. This phenomenon has culminated in a compounded effect of multiple stressors experienced ubiquitously by members of society, leading to the frequent emergence of emotional disorders including stress, panic, anxiety, depression, and so on. Approximately 970 million individuals worldwide suffered from mental disorders, with roughly 280 million diagnosed with depression in 2019. Notably, this figure has exhibited a marked upward trend amid the global COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization, 2022). Particularly alarming is the shifting demographic landscape of depressive symptoms; a notably younger age group is increasingly affected, posing significant public health challenges that cannot be overlooked. An insightful survey focusing on mental health status among the Chinese population revealed that adolescents are at a significantly higher risk for depression compared to adults, with college students facing particularly pronounced risks (Fu et al., 2023). The urgency and complexity surrounding youth mental health are intricately linked to social media usage (Vidal et al., 2020).

The swift advancement of mobile internet technology and the widespread adoption of smartphones have cultivated a new social landscape. Social media, encompassing both private and public dimensions within cyberspace, serves as a crucial conduit for users to maintain and establish interpersonal relationships while providing a distinctive platform for individuals to express themselves and observe others (Treem et al., 2016). Characterized by low barriers to entry, life-oriented content expression, and concise presentation formats, social media platforms align seamlessly with the fragmented and fast-paced lifestyles prevalent today, becoming deeply integrated into the daily routines of internet users. Currently, there are approximately 5.04 billion social media users worldwide (We Are Social, 2024). Numerous studies have indicated that social media use can alleviate stress, augment sensed social support, and improve subjective well-being (Craig et al., 2021; O’Reilly et al., 2022; Rosen et al., 2022; Sahoo et al., 2024). Nevertheless, contrasting research indicates that excessive or problematic social media engagement exerts adverse impacts on users’ mental health status (Jin et al., 2024; Zhao and Zhou, 2020). A comprehensive meta-analysis further highlights that among young adults, social media engagement is related to increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Shannon et al., 2022). Consequently, while the precise manner in which social media influences mental health remains a subject of persistent scholarly discourse and ongoing investigation, it is undeniable that social media usage significantly shapes an individual’s emotional experiences—both positively and negatively.

In light of this context, exploring the specific behaviors associated with social media usage and their impacts on the young group’s mental well-being is not only an inevitable requirement under the current societal context but also an inescapable and significant topic in the field of mental health research. The current research targets college students to explore the association of specific social media usage behavior, particularly distress disclosure, with their mental health status pertaining to depressive symptoms. Prior studies have established a correlation between distress disclosure and depressive symptoms. Although research on self-disclosure has shifted from offline to online environments following transformations in human interaction patterns, existing investigations remain inadequate in examining distress disclosure within the context of social media. Furthermore, current research exploring the relationship between self-disclosure and depressive symptoms rarely investigates simultaneously the mediating role of social comparison and the moderating effects of gender. Given the prevalent tendencies toward social comparison and gender disparities in online interactions, this study integrates social comparison theory with perspectives on gender differences to elucidate the complex mechanisms underlying the relationship between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms. The objectives are threefold: to promote healthier practices for engaging with social media, to provide empirical evidence for mental health intervention strategies targeting Chinese college students, and to contribute to the expanding body of research concerning social media usage and psychological well-being.

Self-disclosure, as a mechanism of information transmission, is intricately interwoven into the fabric of social interactions (Dindia et al., 1997). It encompasses the process through which individuals voluntarily share their inner thoughts, emotional experiences, and personal information with others (Derlega et al., 1993). When such disclosures pertain to personal stress, unhappiness, or distress, they can be classified as distress disclosure (Coates and Winston, 1987), representing a particularly profound form of communication that may possess therapeutic potential. Decades of academic research have continuously shown a significant relationship between self-disclosure and an individual’s physical and mental health (Martin et al., 2020; Aldahadha, 2023; Gonsalves et al., 2023; Doan et al., 2025). For instance, Kahn and Garrison’s (2009) empirical study identified a significant association between emotional self-disclosure and the symptoms connected with depressive symptoms. Similarly, Zhen et al. (2018) discovered that self-disclosure served as a moderating role in the connection between social support and depressive symptoms among flood victims. Specifically, social support primarily alleviates depressive symptoms by enhancing safe sensations and reducing negative self-perception while simultaneously facilitating self-disclosure.

Notably, the domain of self-disclosure has transcended traditional face-to-face interactions and gradually permeated the virtual landscape. With the continuous advancements in internet technology, the construction of individual identities and the formation of relationships have progressively migrated online. Self-disclosure on social media has become an inevitable behavior among contemporary youth within their social interactions. When individuals publicly express emotions, experiences, or states associated with psychological distress on social media platforms (such as Weibo, WeChat, Facebook, etc.) through text, images, or videos, this phenomenon is referred to as distress disclosure on social media. This shift in disclosure contexts has prompted renewed scholarly inquiries into the effects of self-disclosure within online environments. Research indicates that despite changes in communication settings, the impact of self-disclosure on psychological states, including depression, remains significant (Matthes et al., 2021; Sheese et al., 2004). As an example, Piko et al. (2022) signified that Hungarian college students who participated in extensive self-disclosure online were more prone to experiencing depressive symptoms. Michikyan’s (2019) mixed-methods study revealed a correlation between disclosing negative emotions or experiences online and increased depressive symptoms. In view of this evidence, we put forward the subsequent hypothesis:

H1: Distress disclosure on social media is significantly related to depressive symptoms.

The Social Comparison Theory, formulated by Festinger (1954), advances the proposition that individuals possess an inherent motivation to assess their opinions and abilities by making comparisons with those of others. Schachter (1959) expanded upon this foundational perspective by integrating emotions into the comparative framework, proposing that individuals may participate in comparison to evaluate and comprehend their emotional states when confronted with novel or ambiguous feelings, particularly in the absence of clear physiological or experiential markers for interpretation. As research on social comparison continues to evolve, various dimensions of human life—including academic performance, eating behavior, and appearance—have increasingly been incorporated into the scope of the investigation (Polivy, 2017; Ibn Auf et al., 2023; Lalot and Houston, 2025). To some extent, we can conceptualize social comparison as a psychological activity that is unconsciously triggered within individuals and persists throughout their social interactions.

Drawing upon the advancements in internet technology, the scope of human social interaction has expanded to unprecedented levels. Existing research indicates that social comparison is a prevalent psychological tendency during social media usage (Guo et al., 2022; Kavaklı and Ünal, 2021). For instance, Kirkpatrick and Lee (2024) posited that many mothers participate in social comparisons with the idealized portrayals of motherhood on social media, which can have negative effects on them. Jiotsa et al.’s (2021) research focused on adolescents and young adults determined that social comparison on social media might influence mental well-being by worsening body dissatisfaction and heightening the pursuit of thinness. Concurrently, it has been established that social comparison significantly contributes to depressive symptoms (Wang et al., 2020; Samra et al., 2022; Kagan et al., 2025). A meta-analysis encompassing 14 studies involving clinical populations demonstrates that depressive symptoms are vulnerable to the effects of social comparison (McCarthy and Morina, 2020). Recently, Ruan et al.'s (2023) cross-sectional study examining the mental health of Chinese adolescents revealed that social comparison acts as a mediator in the connection between self-acceptance and depressive symptoms.

Generally speaking, social comparison can be categorized into upward social comparison, downward social comparison, and parallel social comparison. Among these categories, downward social comparisons—where individuals compare themselves to those who perform worse—are typically associated with a positive mental state (Rai et al., 2023). In contrast, upward social comparisons—where individuals compare themselves to those who perform better—are often linked to negative mental health (Tian et al., 2024). It is important to note that individuals in negative emotional states are more prone to engage in upward social comparisons and tend to provide more critical self-evaluations (Swallow and Kuiper, 1988; Burnell et al., 2024). When users express their distress on social media platforms, the unconscious tendency for social comparison may prompt them to ruminate on their distress, thereby exacerbating negative emotions and potentially leading to depressive symptoms (Feinstein et al., 2013; Morina et al., 2024). Thus, the subsequent hypothesis is put forward:

H2: Social comparison serves as a mediator in the connection between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms.

Gender differences must be taken into account when conducting emotion-related studies (Kret and De Gelder, 2012). As a crucial element of interpersonal communication, self-disclosure presents a complex and multifaceted array of gender differences that are related to various contexts and methodological approaches (Valkenburg et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2024; Cöbek et al., 2025). The extensive meta-analysis conducted by Dindia and Allen (1992), which examined 205 studies pertinent to self-disclosure, revealed a consistent pattern indicating that females exhibit a higher frequency of self-disclosure behaviors compared to males. In observational studies, females disclosed more information than their male counterparts, regardless of whether the disclosure was directed toward a close acquaintance or a non-intimate individual. Conversely, in studies utilizing self-report methods, female disclosers reported higher levels of disclosure to intimate targets compared to males; however, the level of disclosure was comparable between genders when the target was a stranger. A recent investigation further explores significant gender disparities in patients’ self-disclosure of medical histories through social media platforms against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic in China (Wang et al., 2023), providing new insights into the gender characteristics associated with self-disclosure behaviors within specific contexts.

Additionally, gender disparities significantly influence how people participate in social comparison, thereby modeling both the psychological experiences and behavioral outcomes associated with this process (Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Samra et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022). Nesi and Prinstein (2015) demonstrate that female users are more inclined to engage in comparisons than their male counterparts when utilizing social networking sites. Research into online body image reveals that, unlike men, women exhibit a greater propensity to edit their photographs and experience heightened negative emotions following instances of upward social comparison (Fox and Vendemia, 2016). A survey examining eating disorder behaviors among junior high school students in China corroborates these findings (Xiang and Kong, 2024). Therefore, given the pervasive nature of gender differences in social interactions, we advance the subsequent hypothesis:

H3: Gender serves as a moderator in the relationship between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms.

This research aimed to achieve three primary objectives: (a) to evaluate the impact of college students’ distress disclosure on social media regarding the progression of depressive symptoms; (b) to investigate whether social comparison is a mediating factor in the link between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms among college students; (c) to assess the moderating impact of gender on the connection between distress disclosure on social media and social comparison. A research model was constructed (Figure 1), as asserted in a comprehensive review of the existing literature.

The research was conducted through a questionnaire survey, which included sections on personal information, distress disclosure on social media, tendencies for social comparison, and an evaluation of depressive symptoms experienced over the past week. We collaborated with counselors from several universities in Anhui and Hubei provinces in China from August to September 2024 to distribute the questionnaires among their student populations. The survey was conducted anonymously through the Wenjuanxing online platform, one of the most widely used questionnaire platforms in China. After excluding incomplete or invalid responses (questionnaire completion time less than 60 s), we ultimately gathered a total of 405 credible responses. Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the demographic features of the sample population.

We conducted the adaptation of the Distress Disclosure Index (DDI) for its Chinese-language version. While retaining the core construct of emotional disclosure, we transition the behavioral context from offline interpersonal interactions to a social media environment. We implement a system scenario conversion strategy that includes: (1) maintaining unchanged emotional trigger conditions (the “when” clause); (2) transforming interpersonal actions (confiding in friends) into platform-specific behaviors (confiding on social media); and (3) ensuring equivalence in mental processes (actively seeking → proactively post). The specific entries of the revised scale are presented in Table 2. The adapted scale contains six items and employs a 5-point for the assessment, with scores spanning from 1 (strong disagreement) to 5 (strong agreement). The outcomes of the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrate robust construct validity for the instrument, as evidenced by the following indices: χ2/df = 3.81, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.08. For the present research, the scale’s reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which yielded a value of 0.90.

The Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM) was utilized to assess the extent of social comparison in college students’ social media usage. The INCOM scale comprises 9 questions that evaluate both abilities (e.g., “I often compare my achievements in life with those of others”) and opinions (e.g., “I often try to figure out what others might be thinking when they face a problem similar to mine”). Responses are scored utilizing a 5-point Likert scale, wherein a rating of 1 signifies “complete disagreement” and a rating of 5 denotes “complete agreement.” Confirmatory factor analysis findings suggest that the scale possesses strong construct validity, as evidenced by the fit indices (χ2/df = 2.27, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.06). For the present investigation, the subscales’ reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which yielded values of 0.86 and 0.84, respectively.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was utilized to quantify depressive symptoms among college students over the past week. The CES-D encompasses 20 items, with each item offering four response options that scored from 1 to 4, where a larger numerical value signifies increased frequency. Notably, four of these items are scored in reverse. An increased total score signifies a greater level of depressive symptoms. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicate that the scale possesses robust construct validity, characterized by fit indices (χ2/df = 3.19, CFI = 0.88, TLI = 0.87, RMESA = 0.07). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.89, providing evidence of the scale’s reliability in the current study.

After conducting a confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency tests on the adopted scales using Amos 28.0, the collected data were subjected to reliability tests, descriptive statistics, and correlation analyses using SPSS 27.0. Additionally, the investigation of specific moderated and mediated effects was conducted using Models 4 and 7 from the SPSS PROCESS macro, as outlined by Hayes (2013).

Harman’s one-factor method was employed to evaluate the presence of common method bias. The outcomes of the unrotated exploratory factor analysis revealed six factors, each with initial eigenvalues greater than 1. Among these, the proportion that constitutes the most significant factor accounts for 21.94% of the total variance, falling beneath the 40% threshold level. Consequently, this study does not exhibit substantial common method biases.

Table 3 offers a presentation of the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis pertaining to the study variables. A statistically significant relationship was observed among the examined variables. In particular, college students’ distress disclosure on social media has a notable positive correlation with social comparison (r = 0.29, p < 0.01), as well as a noteworthy close relationship between their social comparison and levels of depressive symptoms (r = 0.12, p < 0.05).

Model 4 from the SPSS PROCESS macro was employed to examine how social comparison mediates the link between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms in college students while controlling for gender and educational level. Distress disclosure on social media in Model 1 was significantly linked to depressive symptoms (b = 0.17, t = 2.00, p < 0.05), as indicated in Table 4, providing support for Hypothesis 1. The analysis from the model incorporating social comparison as a mediating variable revealed that distress disclosure on social media in Model 2 significantly is related to social comparison (b = 0.33, t = 6.10, p < 0.01). Furthermore, social comparison in Model 3 positively linked to depressive symptoms (b = 0.15, t = 2.00, p < 0.05), whereas the direct pathway of distress disclosure on depressive symptoms became non-significant in Model 3 (b = 0.12, t = 1.33, p > 0.05). The total effects, direct effects, and indirect effects of the mediation model are presented in Table 5. It is observed that the direct effect of distress disclosure on depressive symptoms is not statistically significant [95% CI = (−0.06, 0.29)]; however, both the total effect and the indirect effects are found to be significant [95% CI = (0.00, 0.34), 95% CI = (0.00, 0.11)]. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported: social comparison function in the capacity of a mediating variable between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms (indirect effect = 0.05).

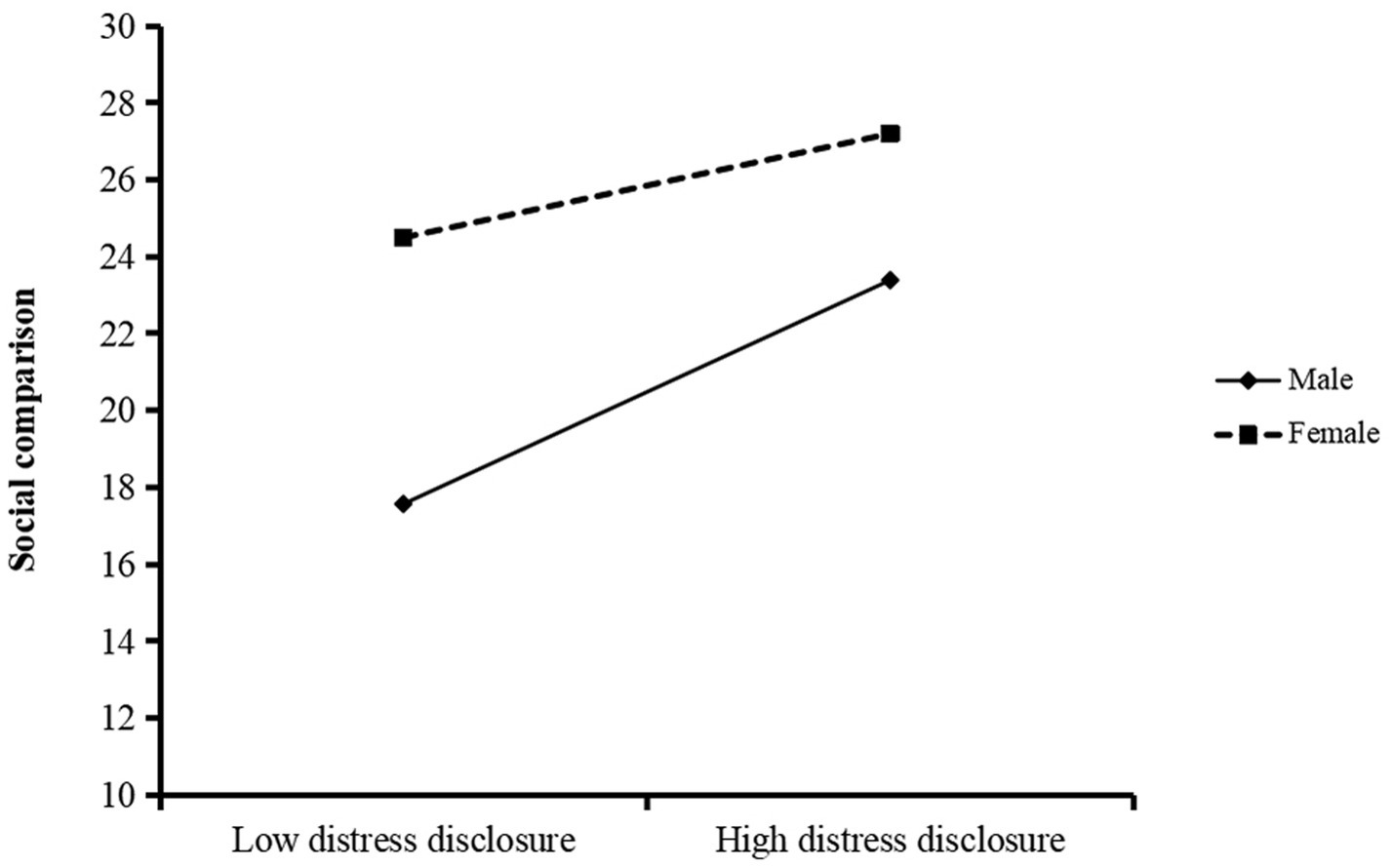

Hypothesis 3 posited that the impact of distress disclosure on social comparison is linked to gender. To evaluate this moderated mediation model, we utilized Model 7 of the SPSS PROCESS macro to evaluate this moderated mediation model, controlling for education level as a variable. The findings from the gender moderation analysis can be found in Table 6. The interaction between distress disclosure on social media and gender was identified as significant (b = −0.28, t = −2.42, p < 0.05), suggesting that gender indeed moderates the impact of distress disclosure on social comparison. Simple slope analyses revealed a significant association between distress disclosure and social comparison among both males [bsimple = 0.52, SE = 0.09, t = 5.56, p < 0.01, 95% CI (0.33, 0.70)] and females [bsimple = 0.24, SE = 0.07, t = 3.59, p < 0.01, 95% CI (0.11, 0.37)] college students; however, this correlation was notably stronger among males than females (Figure 2). Consequently, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 2. Moderating the role of gender in the relationship between distress disclosure and social comparison.

Through the development of a moderated mediation model, this study investigated how college students’ distress disclosure on social media impacts their depressive symptoms. Specifically, it elucidated the role of social comparison as a mediator and investigated how gender moderates this mediation process.

The results of our research highlight a notable correlation between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms, particularly when social comparison variables are disregarded. Specifically, students who frequently share negative emotions or experiences on social media demonstrate a markedly increased risk of developing depressive symptoms. This finding sharply contrasts with previous research that primarily examined the relationship between offline self-disclosure and depressive symptoms, which often reported negative associations. However, our conclusions align with previous studies focusing on online environments. These studies suggest that, unlike offline disclosure, self-disclosure and social interactions occurring in internet-mediated contexts may not yield the same benefits (Towner et al., 2022). They may even provoke negative emotions (Chu et al., 2022) and diminish perceived happiness (Schiffrin et al., 2010). Especially for individuals facing adversity, who may be influenced by an array of factors, including false disclosures and limited social support networks, their online distress disclosures are unlikely to enhance their mental health status and may exacerbate feelings of depressive symptoms (Luo and Hancock, 2020).

This may stem from the relatively straightforward nature of the self-disclosure environment in offline, face-to-face communication contexts, which contrasts sharply with the heightened vulnerability of sharing personal information via social media platforms to a myriad of intricate and multifaceted influencing factors. In offline settings, simplicity arises from the physical constraints and direct interpersonal dynamics that shape the disclosure environment. In contrast, social media operates within a broader, dynamic digital landscape, where self-disclosure is intricately associated with a diverse array of individual-level factors (e.g., age, gender, technical skills, emotional state, privacy concerns) and external variables (including disclosure context, anonymity, size of the online network, culture background) (Ashuri and Halperin, 2024), thereby exhibiting a more complex and nuanced interplay of factors. The result reinforces the potential impact of online environments’ characteristics on individuals’ mental health status, particularly in facilitating or exacerbating the transformation of negative emotions into depressive sentiments.

Acknowledging the intricacies of the online disclosure environment, this study delves into the underlying mechanisms of social comparison in mediating the connection between college students’ distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms. By constructing a theoretical model that incorporates social comparison as a mediating variable, we uncover that when social comparison is incorporated into the model, the existing direct positive correlation between distress disclosure and depressive symptoms is no longer evident, signifying social comparison’s role as a full mediator in this relational chain. In other words, the subsequent elicitation of depressive symptoms among college students after their distress disclosure on social media primarily occurs through an indirect pathway—the process of social comparison. This finding reinforces prior research positing that social comparison behaviors on online platforms constitute a ubiquitous phenomenon, profoundly influencing individual’s emotional experiences, manifesting in intensified jealousy, eroded self-esteem, and the precipitation of depressive sentiments, among other facets (Coyne et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020; Samra et al., 2022).

On one hand, college students in the emerging adulthood stage experience a life phase characterized by a rich tapestry of diverse choices. The ongoing process of refining and adjusting their visions for future life trajectories not only renders this period exceptionally emotionally intense but also introduces a heightened degree of instability (Arnett, 2004). On the other hand, mobile cyberspace has ushered in an unprecedented era of expressive freedom and discourse empowerment for users, significantly facilitating the circulation and dissemination of information. Nevertheless, this increased engagement and visibility have also given rise to a series of challenges. Driven by the attention economy, exaggerated narratives, the proliferation of one-sided information, and the fabrication of false content have converged to create a complex and dynamic information landscape. Within this intricate context, emotionally nuanced and volatile college students who utilize social media platforms as avenues for personal emotional catharsis or expressions of distress risk becoming ensnared in negative emotions such as depressive symptoms if they do not adequately address the spontaneously arising tendencies toward social comparison. This situation poses a substantial threat to individuals’ physical and mental well-being.

Furthermore, our study found that the interaction between gender and distress disclosure was associated with social comparison. Specifically, within the mediational pathway of “distress disclosure on social media - social comparison - depressive symptoms,” gender plays a moderate role in the initial segment of this pathway. This highlights a pronounced disparity in the relationship between distress disclosure behaviors on social media and social comparison among individuals of different genders. In particular, the correlation is more pronounced among male college students, while it appears to be relatively weaker for female students. In other words, male college students exhibit heightened sensitivity and vulnerability to social comparison when expressing distress on social media platforms compared to their female counterparts. This dynamic may potentially exacerbate their risk of developing depressive symptoms.

This phenomenon may arise from the differing coping mechanisms employed by males and females in managing distressing emotions. Compared to females, males tend to engage less frequently in emotional expression in their daily lives (Buck et al., 1974; Kisilevich et al., 2011), let alone disclose their painful experiences or negative emotions. Within the Chinese cultural context, the traditional notion that “men do not easily shed tears” serves as a microcosm of societal expectations, reinforcing norms that prescribe men to maintain an image of independence, resilience, and bravery. Consequently, this cultural norm propels males towards adopting a more conservative approach to emotional expression, often leading them to avoid disclosing their inner distress to others so that reduce the likelihood of facing harsher societal judgments. In contrast, female self-disclosure tends to elicit greater emotional empathy and networking support than male self-disclosure (Lowenstein-Barkai, 2020). The relatively supportive environment encourages females to share their distress on social media platforms (Tifferet, 2020). This cycle of emotional expression and receipt of positive feedback facilitates effective venting of negative emotions among females, thereby reducing the need for seeking validation through social comparison. In addition, compared to their male counterparts, females exhibit a preference for utilizing a broader spectrum of emotion regulation strategies (Tamres et al., 2002), which encompass but are not limited to rumination (recurring contemplation on emotional events and their implications), positive self-talk (engaging in self-motivation and positive reframing when confronting negative emotions), and cognitive reappraisal (actively adjusting one’s understanding and evaluation of emotional events to diminish their emotional impact). This gender-specific divergence in the adoption of emotion regulation strategies is likely to impact individuals’ patterns of distress disclosure within social media settings, ultimately contributing to gender differences in the extent of social comparison manifested.

This study contributes theoretically in several ways. Firstly, we affirm that individuals’ distress disclosure is related to their depressive symptoms within the increasingly ubiquitous platform of social media, despite potential inconsistencies with findings derived from offline contexts. This revelation underscores the complex and distinctive impact that social media has on the mental well-being of individuals. Furthermore, by innovatively integrating social comparison and gender variables into an analytical model, we separately dissect the mediating or moderating roles they played in the relationship between distress disclosure on social media and college students’ depressive symptoms. This not only deepens our comprehension of the dynamic mental health shifts among college students within social media environments but also offers fresh perspectives and potential explanatory pathways for the observed trend of younger age groups experiencing depressive symptoms, attributed to social media factors. Ultimately, leveraging empirical data gathered from a particular group of Chinese college students, our research enriches the cross-cultural, cross-situational research framework that explores the link between social media usage and mental well-being, contributing valuable empirical insights to the global discourse.

Practically, this research holds significant implications. Specifically, it uncovers that college students’ distress disclosure on social media exacerbates depressive symptoms by intensifying social comparison tendencies, pinpointing crucial intervention targets for mental health. Consequently, we propose several targeted recommendations: Firstly, strengthen mental health education for college students, particularly regarding healthy social media interactions, including guiding them to shift their social comparison mindset and advocating for treating others as sources of learning rather than mere objects of comparison, thereby alleviating the psychological burden stemming from misguided comparisons. Secondly, encourage more positive and constructive strategies during distress disclosure on social media, such as seeking empathy and support rather than mere validation or comparison, to optimize self-cognition and emotion regulation. Additionally, acknowledging the pronounced role of gender differences in the distress disclosure-depressive symptoms nexus, we suggest that mental health service systems should enhance gender sensitivity, offering tailored psychological support and intervention plans for students of different genders to more effectively promote their mental well-being. Lastly, advocate for diversified avenues and methods of seeking help, encouraging students to flexibly choose online or offline channels for emotional expression and problem-solving, thereby comprehensively addressing depressive sentiments and safeguarding mental health.

The study has several remaining limitations. Firstly, to mitigate the confusion expressed by participants regarding questionnaire items during the initial survey phase, the DDI and INCOM scales utilized in this research excluded reverse items from the original scale. Consequently, future endeavors should employ the full original scale, or develop a special Distress Disclosure on Social Media Scale to achieve a more comprehensive and objective assessment of participants’ distress disclosure levels. Secondly, being a cross-sectional study, the data collected solely reflects the status of participants at the time of investigation, and the findings cannot be solely interpreted as rigorous causal relationships. Therefore, future research should design more rigorous longitudinal or experimental studies to explore the correlations and underlying mechanisms between variables over an extended period. Lastly, this study focused solely on how social comparison performs a function in the connection between college students’ distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms. Given the various factors that influence depressive symptoms within the complex interaction contexts created by social media, the forthcoming investigation should probe additional potential ways in which distress disclosure influences depressive symptoms, offering insights to enhance the mental state of college students.

Our paper indicates that the distress disclosure on social media platforms among college students significantly is related to their depressive symptoms, with this mediation role played by the psychological tendency toward social comparison. Furthermore, this research confirms that gender act as a moderated role in the connection between distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms, suggesting that male students’ disclosures have a more pronounced impact on their tendencies for social comparison compared to their female counterparts. Consequently, universities and families should pay close attention to students’ use of social media, enhancing their media literacy by guiding them towards healthier practices and accurate discernment of online content. This approach is likely to foster positive effects related to social comparison, ultimately mitigating depressive symptoms and bolstering self-esteem.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements as the research does not involve any experimental intervention but rather focuses on the analysis of anonymized data. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants or participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

XY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant Number: CIA240280).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aldahadha, B. (2023). Self-disclosure, mindfulness, and their relationships with happiness and well-being. Middle East Curr. Psychiatr. 30:7. doi: 10.1186/s43045-023-00278-5

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ashuri, T., and Halperin, R. (2024). Online self-disclosure: an interdisciplinary literature review of 10 years of research. New Media Soc. doi: 10.1177/14614448241247313

Buck, R., Miller, R. E., and Caul, W. F. (1974). Sex, personality, and physiological variables in the communication of affect via facial expression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 30, 587–596. doi: 10.1037/h0037041

Burnell, K., Trekels, J., Prinstein, M. J., and Telzer, E. H. (2024). Adolescents’ social comparison on social media: links with momentary self-evaluations. Affect. Sci. 5, 295–299. doi: 10.1007/s42761-024-00240-6

Chu, T. H., Sun, M., and Crystal Jiang, L. (2022). Self-disclosure in social media and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 40, 576–599. doi: 10.1177/02654075221119429

Coates, D., and Winston, T. (1987). “The dilemma of distress disclosure” in Self-disclosure. eds. V. J. Derlega and J. H. Berg (Boston, Ma: Springer US) 229–255.

Cöbek, G., Baş, Ö., Audry, A. S., İnceoğlu, İ., Kaya, Y. B., and Özenç, A. (2025). Putting your best self or no self at all? An analysis of young Adult’s dating app profiles in Turkey. Sex. Cult. doi: 10.1007/s12119-025-10314-7

Coyne, S. M., McDaniel, B. T., and Stockdale, L. A. (2017). ‘Do you dare to compare?’ Associations between maternal social comparisons on social networking sites and parenting, mental health, and romantic relationship outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 70, 335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.081

Craig, S. L., Eaton, A. D., McInroy, L. B., Leung, V. W. Y., and Krishnan, S. (2021). Can social media participation enhance LGBTQ+ youth well-being? Development of the social media benefits scale. Social Media + Society 7, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/2056305121988931

Derlega, V. J., Metts, S., Petronio, S., and Margulis, S. T. (1993). Self-disclosure. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, Cop.

Dindia, K., and Allen, M. (1992). Sex differences in self-disclosure: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 112, 106–124. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.106

Dindia, K., Fitzpatrick, M. A., and Kenny, D. A. (1997). Self-disclosure in spouse and stranger interaction a social relations analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 23, 388–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1997.tb00402.x

Doan, U., Hong, D., and Hitchcock, C. (2025). Please, just talk to me: self-disclosure mediates the effect of autobiographical memory specificity on adolescent self-harm and depressive symptoms in a UK population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 376, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2025.01.141

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., and Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: rumination as a mechanism. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2, 161–170. doi: 10.1037/a0033111

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202

Fox, J., and Vendemia, M. A. (2016). Selective self-presentation and social comparison through photographs on social networking sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 19, 593–600. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0248

Fu, X. L., Zhang, K., Chen, X. F., and Chen, Z. Y. (2023). Report on national mental health development in China (2021–2022). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China).

Gonsalves, P. P., Nair, R., Roy, M., Pal, S., and Michelson, D. (2023). A systematic review and lived experience synthesis of self-disclosure as an active ingredient in interventions for adolescents and young adults with anxiety and depression. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 50, 488–505. doi: 10.1007/s10488-023-01253-2

Guo, S., Bi, K., Zhang, L., and Jiang, H. (2022). How does social comparison influence Chinese adolescents’ flourishing through short videos? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8093. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138093

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Ibn Auf, A. A. A., Alblowi, Y. H., Alkhaldi, R. O., Thabet, S. A., Alabdali, A. A. H., Binshalhoub, F. H., et al. (2023). Social comparison and body image in teenage users of the TikTok app. Cureus 15:e48227. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48227

Jin, T., Chen, Y., and Zhang, K. (2024). Effects of social media use on employment anxiety among Chinese youth: the roles of upward social comparison, online social support and self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 15:1398801. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1398801

Jiotsa, B., Naccache, B., Duval, M., Rocher, B., and Grall-Bronnec, M. (2021). Social media use and body image disorders: association between frequency of comparing One’s own physical appearance to that of people being followed on social media and body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2880. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062880

Kagan, M., Ben-Shalom, U., and Mahat-Shamir, M. (2025). The role of physical appearance comparison, self-esteem, and emotional control in the association between social media addiction and masculine depression. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. doi: 10.1177/08944393251315915

Kahn, J. H., and Garrison, A. M. (2009). Emotional self-disclosure and emotional avoidance: relations with symptoms of depression and anxiety. J. Couns. Psychol. 56, 573–584. doi: 10.1037/a0016574

Kavaklı, M., and Ünal, G. (2021). The effects of social comparison on the relationships among social media addiction, self-esteem, and general belongingness levels. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 9, 114–124. doi: 10.5114/cipp.2021.105349

Kirkpatrick, C. E., and Lee, S. (2024). Idealized motherhood on social media: effects of mothers’ social comparison orientation and self-esteem on motherhood social comparisons. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 68, 284–304. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2024.2324152

Kisilevich, S., Ang, C. S., and Last, M. (2011). Large-scale analysis of self-disclosure patterns among online social networks users: a Russian context. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 32, 609–628. doi: 10.1007/s10115-011-0443-z

Kret, M. E., and De Gelder, B. (2012). A review on sex differences in processing emotional signals. Neuropsychologia 50, 1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.12.022

Lalot, F., and Houston, D. M. (2025). Comparison in the classroom: motivation for academic social comparison predicts academic performance. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 28, 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s11218-024-10008-2

Liu, Q., Li, Z., and Zhu, J. (2024). Online self-disclosure and self-concept clarity among Chinese middle school students: a longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 53, 1469–1479. doi: 10.1007/s10964-024-01964-1

Lowenstein-Barkai, H. (2020). #me(n)too? Online social support toward male and female survivors of sexual victimization. J. Interpers. Violence 36, NP13541–NP13563. doi: 10.1177/0886260520905095

Luo, M., and Hancock, J. T. (2020). Self-disclosure and social media: motivations, mechanisms and psychological well-being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 31, 110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.019

Martin, A., Chilton, J., Gothelf, D., and Amsalem, D. (2020). Physician self-disclosure of lived experience improves mental health attitudes among medical students: a randomized study. J. Med. Educat. Curri. Develop. 7:238212051988935. doi: 10.1177/2382120519889352

Matthes, J., Koban, K., Neureiter, A., and Stevic, A. (2021). Longitudinal relationships among fear of COVID-19, smartphone online self-disclosure, happiness, and psychological well-being: survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e28700. doi: 10.2196/28700

McCarthy, P. A., and Morina, N. (2020). Exploring the association of social comparison with depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 27, 640–671. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2452

Michikyan, M. (2019). Depression symptoms and negative online disclosure among young adults in college: a mixed-methods approach. J. Ment. Health 29, 392–400. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2019.1581357

Morina, N., Meyer, T., McCarthy, P. A., Hoppen, T. H., and Schlechter, P. (2024). Evaluation of the scales for social comparison of appearance and social comparison of well-being. J. Pers. Assess. 106, 625–637. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2023.2298887

Nesi, J., and Prinstein, M. J. (2015). Using social Media for Social Comparison and Feedback-Seeking: gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0

O’Reilly, M., Levine, D., Donoso, V., Voice, L., Hughes, J., and Dogra, N. (2022). Exploring the potentially positive interaction between social media and mental health; the perspectives of adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 28, 668–682. doi: 10.1177/13591045221106573

Piko, B. F., Kiss, H., Rátky, D., and Fitzpatrick, K. M. (2022). Relationships among depression, online self-disclosure, social media addiction, and other psychological variables among Hungarian university students. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 210, 818–823. doi: 10.1097/nmd.0000000000001563

Polivy, J. (2017). What’s that you’re eating? Social comparison and eating behavior. Journal of. Eat. Disord. 5:18. doi: 10.1186/s40337-017-0148-0

Rai, R., Cheng, M.-I., and Scullion, H. (2023). How people use Instagram and making social comparisons are associated with psychological wellbeing. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 9, 204–210. doi: 10.1007/s41347-023-00319-0

Rosen, A. O., Holmes, A. L., Balluerka, N., Hidalgo, M. D., Gorostiaga, A., Gómez-Benito, J., et al. (2022). Is social media a new type of social support? Social media use in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:3952. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19073952

Ruan, Q. N., Shen, G. H., Yang, J. S., and Yan, W. J. (2023). The interplay of self-acceptance, social comparison and attributional style in adolescent mental health: cross-sectional study. Br. J. Psychiatry Open 9:e202. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2023.594

Sahoo, P., Mishra, M., and Das, S. C. (2024). Social media impact on psychological well-being—a cross-sectional study among the adolescents of Odisha. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 13, 859–863. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_325_23

Samra, A., Warburton, W. A., and Collins, A. M. (2022). Social comparisons: a potential mechanism linking problematic social media use with depression. J. Behav. Addict. 11, 607–614. doi: 10.1556/2006.2022.00023

Schachter, S. (1959). The psychology of affiliation: experimental studies of the sources of gregariousness. Redwood City CA: Stanford University Press.

Schiffrin, H., Edelman, A., Falkenstern, M., and Stewart, C. (2010). The associations among computer-mediated communication, relationships, and well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 13, 299–306. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0173

Shannon, H., Bush, K., Villeneuve, P., Hellemans, K., and Guimond, S. (2022). Problematic social media use in adolescents and young adults: a meta-analysis. JMIR Ment. Health 9:e33450. doi: 10.2196/33450

Sheese, B. E., Brown, E. L., and Graziano, W. G. (2004). Emotional expression in cyberspace: searching for moderators of the Pennebaker disclosure effect via E-mail. Health Psychol. 23, 457–464. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.457

Sun, M., Jiang, L. C., and Huang, G. (2022). Improving body satisfaction through fitness app use: explicating the role of social comparison, social network size, and gender. Health Commun. 38, 2087–2098. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2054099

Swallow, S. R., and Kuiper, N. A. (1988). Social comparison and negative self-evaluations: an application to depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 8, 55–76. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90049-9

Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D., and Helgeson, V. S. (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: a Meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 6, 2–30. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0601_1

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., and Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 22, 535–542. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

Tian, J., Li, B., and Zhang, R. (2024). The impact of upward social comparison on social media on appearance anxiety: a moderated mediation model. Behav. Sci. 15:8. doi: 10.3390/bs15010008

Tifferet, S. (2020). Gender differences in social support on social network sites: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 199–209. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0516

Towner, E., Grint, J., Levy, T., Blakemore, S. J., and Tomova, L. (2022). Revealing the self in a digital world: a systematic review of adolescent online and offline self-disclosure. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 45:101309. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101309

Treem, J. W., Dailey, S. L., Pierce, C. S., and Biffl, D. (2016). What we are talking about when we talk about social media: a framework for study. Sociol. Compass 10, 768–784. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12404

Valkenburg, P. M., Sumter, S. R., and Peter, J. (2010). Gender differences in online and offline self-disclosure in pre-adolescence and adolescence. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 29, 253–269. doi: 10.1348/2044-835x.002001

Vidal, C., Lhaksampa, T., Miller, L., and Platt, R. (2020). Social media use and depression in adolescents: a scoping review. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 32, 235–253. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1720623

Wang, Y., Qiao, T., and Liu, C. (2023). A study of reasons for self-disclosure on social media among Chinese COVID-19 patients: based on the theory of planned behavior model. Healthcare 11:1509. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11101509

Wang, W., Wang, M., Hu, Q., Wang, P., Lei, L., and Jiang, S. (2020). Upward social comparison on mobile social media and depression: the mediating role of envy and the moderating role of marital quality. J. Affect. Disord. 270, 143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.173

We Are Social (2024). Digital 2024 global overview report. https://wearesocial.com/cn/blog/2024/01/digital-2024-5-billion-social-media-users/ (Accessed September 10, 2024).

World Health Organization (2022). World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/356119/9789240049338-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed September 10, 2024).

Xiang, K. Q., and Kong, F. C. (2024). Passive social networking sites use and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: the roles of upward social comparison and body dissatisfaction and its sex differences. Appetite 198:107360. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2024.107360

Zhao, N., and Zhou, G. (2020). Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 12, 1019–1038. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12226

Keywords: distress disclosure, social media, social comparison, gender, depressive symptoms

Citation: Ye X and Gao H (2025) Distress disclosure on social media and depressive symptoms among college students: the roles of social comparison and gender. Front. Psychol. 16:1520066. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1520066

Received: 30 October 2024; Accepted: 01 April 2025;

Published: 16 April 2025.

Edited by:

Xuemei Gao, Southwest Jiaotong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Muhtahir Oloyede, University of Ilorin, NigeriaCopyright © 2025 Ye and Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoli Ye, eWV4aWFvbGlAYWh1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.