94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 14 February 2025

Sec. Sport Psychology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1502174

This article is part of the Research Topic The Burnout Spectrum in Schools and Sports: Students, Teachers, Athletes, and Coaches at Risk View all 3 articles

Introduction: Prior research has shown that increasing training and competition loads, along with associated stressors, can negatively impact athletes’ mental health and contribute to burnout. While athlete burnout can be associated with various negative sports-related consequences, such as withdrawal from sports or injuries. Although most studies on athlete burnout employ cross-sectional designs, longitudinal approaches could provide valuable insights into athlete burnout changes over time and potential causal relationships between variables and burnout. Therefore, this study aims to systematically examine longitudinal design studies to offer a comprehensive methodological, conceptual, and practical overview of athlete burnout and its associated factors.

Methods: Following PRISMA-ScR guidelines, this review explores what factors influence changes in burnout levels among athletes throughout a sports season. Therefore, studies were selected that examined athlete burnout across both genders, all age groups, and various sport types, using repeated measurements. Published articles from 2014 to 2024 were collected. Eligible studies were identified through three databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science.

Results: A total of 32 studies were analyzed. Quantitative mapping highlights study demographics, measurement approaches, and procedures, while qualitative mapping identifies 26 factors categorized as risk, protective, and factors influenced by burnout. The review highlights the use of tools like the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire and identifies optimal data collection intervals for tracking burnout dynamics.

Conclusion: This scoping review offers insights into the multidimensional and nonlinear nature of athlete burnout, emphasizing its development through longitudinal studies and the importance of monitoring specific dimensions. The findings revealed various athlete burnout influencing personal and sport-environmental factors, including risk factors like perfectionistic concerns and negative social interaction, protective factors such as resilience-related skills and relatedness, and social support. The study emphasizes the importance of early detection and longitudinal monitoring to prevent burnout and mitigate its impact on athletes’ mental health and performance. Further research is needed to explore additional risk and protective factors to develop effective interventions aimed at reducing the risk of burnout in athletes.

Burnout is a mental health problem that appears to be increasingly common among athletes in recent years (Madigan et al., 2022). Importantly, burnout may additionally raise the risk of acquiring both mental and physical health disorders (Glandorf et al., 2023; Wilczyńska et al., 2022). A systematic review of mental and physical health outcomes of burnout in athletes showed significant results, that athlete burnout was associated with increases in negative mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety, addictive behavior, insomnia, worry, mood, psychological distress, body image dissatisfaction) and decreases in positive mental health outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, subjective wellbeing, and quality of life). Burnout negatively affects athletes in various aspects, including reducing performance, hindering interpersonal relationships, and impairing well-being (Eklund and DeFreese, 2020). However, evidence for an association between athlete burnout and physical health outcomes was mixed (Glandorf et al., 2023).

Burnout was initially observed in caregiving professions and was defined as a psychological syndrome comprised of three symptoms—reduced professional efficacy, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization (Maslach and Jackson, 1986). Raedeke (1997) adapted Maslach and Jackson (1986) burnout concept to the sports context and athletic experience. Reduced professional efficacy was associated with sports context and defined as a reduced sense of accomplishment, regarding athletic abilities and accomplishments. Physical fatigue, which is a consequence of training and competing, was incorporated into the definition of emotional and physical exhaustion. Depersonalization was the least adaptable to the sports context, therefore Raedeke proposed to use devaluation. For athletes, devaluation appears as a negative attitude towards sport and psychological detachment from sport. Therefore, Raedeke in 1997 established athlete burnout as a psychological syndrome composed of three dimensions: physical/emotional exhaustion, reduced sense of accomplishment, and sport devaluation.

The way that burnout changes over time has been examined in numerous studies (e.g., Amemiya and Sakairi, 2022; Shannon et al., 2022; Waleriańczyk and Stolarski, 2022). These studies demonstrate that burnout in general, as well as each of its dimensions individually, is variable and can develop or diminish over time. It is proven that that the reduced sense of accomplishment dimension tends to increase over time, this could be explained by the fact that athletes respond to the increased competition load with a greater negative evaluation of their performances and abilities (Madigan et al., 2022). Also, during the competitive season, this burnout dimension increases significantly (Madigan et al., 2022). Additionally, during the sporting season and generally, over time, the sport devaluation dimension increases (Pires and Ugrinowitsch, 2021). Athletes evaluate their athletic ability more negatively and feel a greater need to disassociate themselves from their sport (Madigan et al., 2022). The dimension of physical and emotional exhaustion shows less discernible changes over time, and it also varies less with the season (Madigan et al., 2022; Pires and Ugrinowitsch, 2021).

Several models have been proposed to explain the development of athlete burnout. The scenario in which athletes evaluate sports practice as a source of stress provides support for the cognitive-affective model (CAM) of burnout proposed by Smith (1986). According to this model, the imbalance between the demands of a situation and the coping resources to deal with them can lead to stress. As noted in a recent meta-analysis and longitudinal studies, stress is one of the factors most strongly related to athlete burnout (Lin et al., 2022; Madigan et al., 2022; Nixdorf et al., 2020; Pires and Ugrinowitsch, 2021). Another theory discussed in this context is self-determination theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, 1985). According to SDT, the satisfaction of the core human needs of autonomy (perceptions of control and self-endorsement of an activity), competence (perceptions of proficiency), and relatedness (connection with others) are fundamental for optimal psychological well-being and human functioning (Gustafsson et al., 2017). When needs are satisfied, athletes develop intrinsic motives for participation and experience optimal health. In sports, intrinsic motivation is associated with an athlete’s interest and enjoyment that is derived from participating in sports, however, a lack of motivation is connected to an athlete’s lack of self-determination (Kinoshita et al., 2023). An additional model that explains the burnout of athletes is the sport commitment model (Schmidt and Stein, 1991), which is an etiological paradigm of burnout, in which the variable of interest is sport commitment. Authors of the sport commitment model consider burnout syndrome in athletes according to a combination of five factors—benefits, costs, satisfaction, alternatives, and investments (De Francisco et al., 2022). In 1997, Raedeke presented a commitment-based model (CBM; Raedeke, 1997), representing the desire and resolve to continue participating in sports. Commitment is perceived as the outcome of three elements:

1. How attractive or enjoyable the activity is perceived;

2. Which alternatives to the activity are viewed as in a greater or lesser degree attractive;

3. Restrictions the athlete perceives to withdraw from sport such as personal investments and social constraints.

How athletes interpret these facets determines whether their commitment is based on attraction (“want to”) or entrapment (“have to”). According to this perspective, athletes who burn out do so because they are committed solely for entrapment reasons (Madigan et al., 2022). Raedeke (1997) characterized athlete commitment as having the “two faces” of attraction and entrapment. It was believed that athletes who considered their activity to be intrinsically rewarding and who wished to participate in it were exhibiting attraction-based commitment. On the other hand, athletes were seen to be exhibiting entrapment-related commitment if they were no longer intrinsically motivated to participate in the sport and felt obligated to continue playing while no longer having an innate desire to do so (Raedeke, 1997).

These models highlight a variety of elements that contribute to athlete burnout, both individually and environmentally (in a sports context). It can be difficult to recognize and avoid a wide range of these issues. Individual and environmental issues should be addressed together for each case as part of a multifaceted therapeutic strategy. Indeed, using an individual-organization fit paradigm may prove particularly beneficial in the prevention of burnout (DeFreese et al., 2015).

Even mild signs emphasize the importance of early burnout identification, which, if neglected, can have a considerable influence on sports performance (Hassmén et al., 2023). Reducing adolescent athlete burnout could be essential for the general growth of youth in society (Wilczyńska et al., 2022). It is possible to observe changes in athlete burnout scores by conducting longitudinal studies, in which a variable or group of variables in the same cases or participants is studied over a period of time, sometimes several years (American Psychological Association, 2018). There are longitudinal studies of athlete burnout, but no review has been done where all of these studies were gathered and examined. As such, the purpose of this paper is to systematically examine longitudinal design studies to provide an overview of athlete burnout development and its associated factors.

The scoping review was conducted following the Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review (Mak and Thomas, 2022), and PRISMA for Scoping Reviews guidelines (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). See PRISMA-ScR checklist in Supplementary material. The protocol for this review, including information related to the search strategy, data extractions, and analysis, was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) database.1

A preliminary search of the literature was helpful to determine that research questions are not too broad or too narrow. Literature research was conducted to make sure whether a scoping review on this topic has already been conducted. When such a review had not yet been done, the available literature on this topic was examined. As the topic is currently relevant, enough research is available to conduct a scoping review of the topic.

The PCC Framework, which is advised for a scoping review, was applied to formulate the research question and eligibility criteria (Pollock et al., 2023). The following eligibility criteria were defined:

Population—male and female athletes of all ages, from both team and individual sports, were included in order to provide a comprehensive review of the topic. Excluding other representatives of the sports field, such as coaches.

Concept—factors influencing changes in athlete burnout.

Context—studies with a longitudinal design, with at least two data collection waves (throughout a sports season). Since research from the last 10 years is more likely to reflect the most current theories, methods, technologies, and practices in the field, this research included studies published from 2014 to 2024. By narrowing the focus to the last 10 years, the scoping review stays focused, relevant, and aligned with the most up-to-date understanding of the field. Peer-reviewed studies, published in any language, were included in this scoping review.

The following research question was formulated: What factors influence changes in burnout levels among athletes throughout a sports season?

The search was conducted in April 2024 using three databases. PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were selected due to its broad coverage of multidisciplinary research, including sports psychology, and its ability to index articles from various disciplines. Peer-reviewed journals, citation analysis, and coverage of the field’s theoretical and applied facets are all well-represented in these databases. PubMed focuses on psychological aspects of physical performance, mental health in athletes, and interventions aimed at improving well-being in sports settings. Scopus offers multidisciplinary coverage with citation analysis, helping to identify key studies and leading authors in the field of athlete burnout. Web of Science’s citation tracking allows to identify foundational publications and trace the evolution of burnout theories. Together, these databases provide a comprehensive overview of the field.

After identifying the research question and eligibility criteria, a consultation with a principal librarian about search strategy and terms was organized. Key search terms were combined using Boolean operators: (“burnout s” OR “burnout, psychological” OR (“burnout” AND “psychological”) OR “psychological burnout” OR “burnout” OR “burnouts”) AND (“athlete s” OR “athletes” OR “athlete” for athlete burnout), (“longitudinal studies” OR (“longitudinal” AND “studies”) OR (“longitudinal” AND “study”) OR “longitudinal study”).

Studies selected by titles and keywords (n = 134) were placed in the online software tool—Covidence. Covidence identified 49 duplicates, and 11 duplicates were identified manually. The first and second authors first screened titles, then abstracts, and in the final full texts. If the system showed inconsistencies about the authors’ included or excluded studies, a third author was involved and reviewed each case. The most common reason for excluding the article was that there were no repeated measurements of athletes’ burnout or the population was the wrong one (e.g., sports coaches). See Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for an overview of information search process (Page et al., 2021) (see Figure 1).

The first author performed data extraction in the data charting form (see Table 1). The articles selected for the study (n = 32) were individually analyzed. Data items relevant to the review question and aim, such as—author(s), title, publication year, country, research aim, population description, sport type, research methods, measurements, data collection procedure, key findings, limitations, and future directions—were collected and summarized in a table developed by the authors.

The findings from the numerical analysis are presented in a table to highlight the most salient aspects of the review. Thematic analysis was conducted based on the research purpose and questions. A list of tentative codes was created to group the information into categories. For example, all studies that examined burnout during the competitive season were combined into one category, or all studies that examined the relationship between perfectionism and burnout into another. Afterward, the results were analyzed quantitatively, summarizing the entire study demographics data, measurement approach, and procedure. Qualitative analysis and division of factors affecting athlete burnout into subsections are also needed.

In total, 32 articles met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

Less than half of the articles (n = 15) were published between 2014 and 2018, and the rest of the articles (n = 18) between 2019 and 2024. The most articles (n = 7) were conducted in 2022. Studies have been published in different countries—United Kingdom (n = 8), France (n = 4), United States of America (n = 2), Japan (n = 3), Brazil (n = 3), China (n = 3), Finland (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), Czech Republic (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1). Considering demographics, the average sample size was 228 (ranging from 10 to 895). Females made up 36% of the participants, mean average age was 18.9 years. The athletes were engaged in sports for an average of 8.15 years. They were training for an average of 12.32 h per week. 70% were representatives of team sports (ice hockey, soccer, blind soccer, rugby, handball, netball, baseball, lacrosse, volleyball, basketball, American football, softball, badminton). The remaining 30% were individual athletes (running, gymnastics, running, mountain biking, cycling, short track, swimming, table tennis, skiing, track and field, tennis, taekwondo, boxing, and dance team sport). See Table 2 for study and sample characteristics.

Information on the instruments used to measure athlete burnout was collected and summarized in Table 3.

81% of studies used the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ; Raedeke and Smith, 2001). The ABQ consists of 15 questions, structured on a Likert scale of five points, five questions to measure the sub-areas “physical and emotional exhaustion,” five to measure the sub-area “sport devaluation,” and five to measure the sub-area “reduced sense of sports accomplishment” (Santos-Afonso et al., 2023).

The Burnout Scale for University Athletes (BOSA; Amemiya et al., 2013) was used in 10% of studies. This scale is composed of 20 items, with five items from each of the following four sub-scales: “interpersonal emotional exhaustion,” “lack of personal accomplishment,” “emotional exhaustion for athletic practicing,” and “devaluation of club activities” (Amemiya and Sakairi, 2022).

6% of studies used the Sport Burnout Inventory—Dual Career Form (SpBI-DC; Sorkkila et al., 2017). The SpBI-DC is a modified version of the School Burnout Inventory (SBI; Salmela-Aro et al., 2009) and it has been developed to investigate sports burnout among student-athletes. The scale consists of 10 items, out of which four measure sport-related exhaustion, three measure cynicism toward the meaning of one’s sport, and three measure feelings of inadequacy as an athlete. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (Sorkkila et al., 2019).

3% of studies or one study used the 14-item Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM; Lerman et al., 1999). The SMBM comprises three subscales—physical fatigue, cognitive weariness, and emotional exhaustion (Gerber et al., 2018).

Since only longitudinal studies were collected, an analysis of the procedure of the studies, comparing the frequency and waves of data collection was also performed. See Table 3.

The most frequently used data collection method was at three competitive season points (T1 = preparation phase, T2 = competition phase, and T3 = recovery phase), used in 9 studies (26.5%).

A comparable way of collecting data was at two competitive season points (T1 = within the first 2 to 3 weeks of the season, T2 = during the last part of the season just before playoffs), used in 4 studies (12%). The average interval between each completion was 5 months.

The second most frequently used method of data collection was to collect data separated by a three-month period, and this method was used in 9 studies (26.5%). The three-month interval between waves was considered sufficient because previous research has shown that this time interval allows researchers to capture changes in athlete burnout during periods of active training (e.g., Cresswell and Eklund, 2005; Madigan et al., 2016a; Madigan and Nicholls, 2017).

The other studies (35%) had different data collection intervals—6 months (n = 4), 1 month (n = 3), 1 year (n = 3), 4 months (n = 1), and 5 months (n = 1).

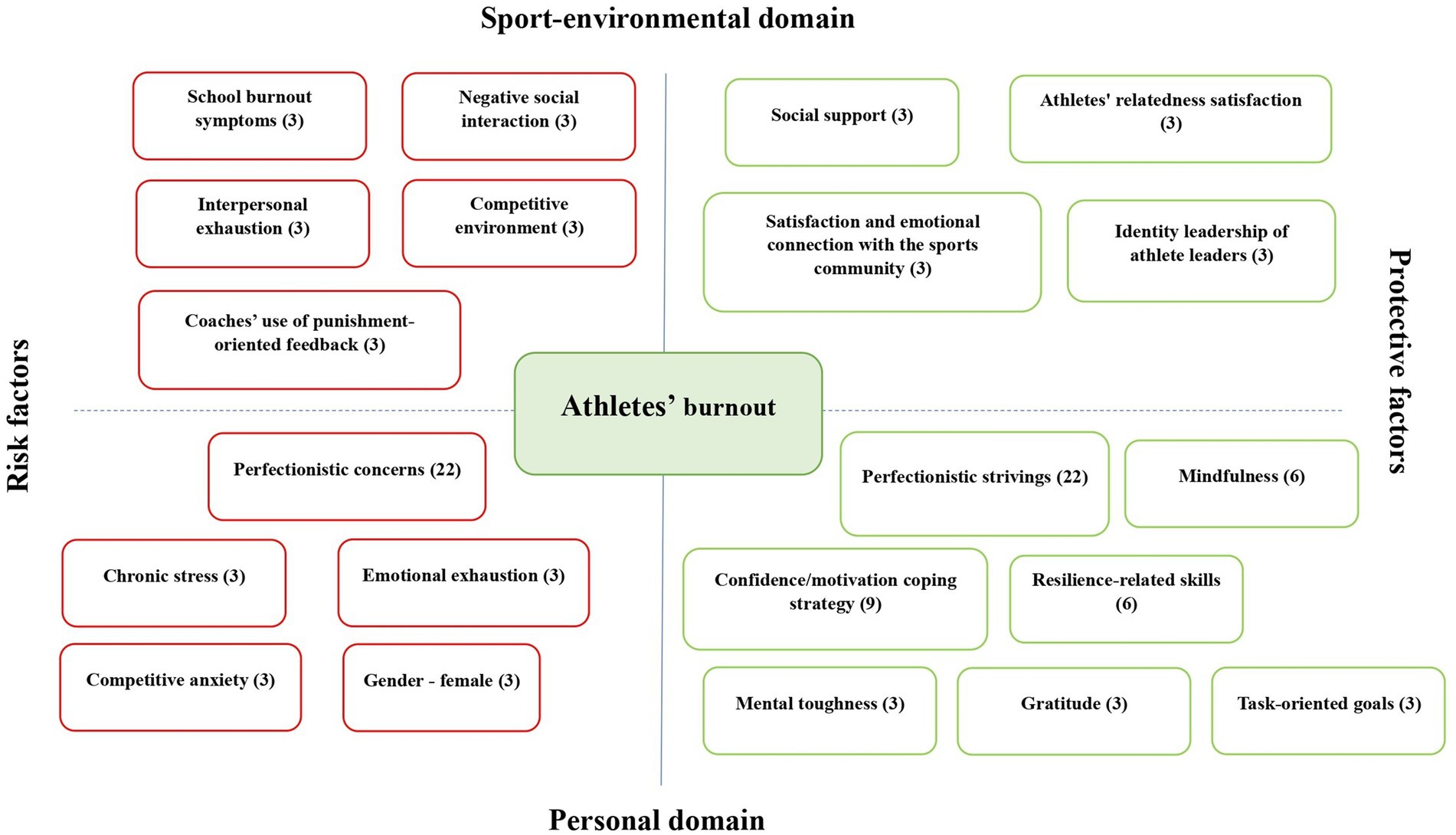

In order to answer the last research question, this chapter summarizes all the athlete burnout-related factors mentioned in the selected studies. These factors were grouped into 26 overarching themes during the analysis and were further divided into several sections—protective factors (n = 12), risk factors (n = 11) and affected by burnout factors (n = 3) (see Table 4). Protective and risk factors were further analyzed and divided into two subsections—personal and sport-environmental factors (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conceptual map of protective and risk factors. Numbers in brackets indicate percentages in relation to the total number of included empirical articles (N = 32).

This section summarizes information on eight different protective factors for athlete burnout.

The most frequently studied predictor of athlete burnout in longitudinal studies was perfectionism. Seven studies (Crowell and Madigan, 2021; Květon et al., 2021; Madigan et al., 2015, 2016a, 2016b; Smith et al., 2018; Waleriańczyk and Stolarski, 2022) aimed to examine the relationship between perfectionism and athlete burnout. Longitudinal results showed that perfectionistic strivings played a significant role in predicting change in burnout in the “long-term” (one-year) perspective, compared to the “short-term” (three-months) longitudinal results (Květon et al., 2021). Also, Madigan and colleagues studied changes over a three-month period and concluded that perfectionistic strivings predicted decreases in athlete burnout over time (Madigan et al., 2015, 2016a). At the level of burnout dimensions, it was discovered that perfectionistic striving cognitions were negatively correlated with devaluation (Crowell and Madigan, 2021; Waleriańczyk and Stolarski, 2022). Three studies investigated coping strategies through the longitudinal. Kelecek and Koruc (2022) study obtained the result that at the beginning of the season burnout negatively correlated with coping strategies, however, two other studies proved that confidence/motivation coping strategy has a negative and moderate correlation between the reduced sense of athletic accomplishment burnout dimension at all four times of the season (Pires et al., 2016; Pires and Ugrinowitsch, 2021). Two studies (Amemiya and Sakairi, 2019; Zhang et al., 2023) revealed that mindfulness has an indirect effect on athlete’s burnout scores. The relationship between resilience and burnout was investigated in two studies (Sorkkila et al., 2019; Ueno and Suzuki, 2016), where it was endorsed that resilience in sports may prevent burnout and the dropout rate of athletes, and it may maintain and improve their mental health. Further three more protective factors will be listed, and each one of them was investigated in only one study. Madigan and Nicholls (2017) longitudinally examined the relationship between mental toughness and burnout and the results showed a significant negative cross-sectional association. Guo et al. (2022) proved that athlete gratitude indirectly affects athlete burnout through athlete engagement and indirectly affects athlete engagement through athlete burnout. Ingrell et al. (2019) examined the within-person relationship between achievement goals and burnout perceptions. It was concluded that task orientation (where success is based on self-referenced criteria) was significantly and negatively related to a reduced sense of accomplishment and sport devaluation. However, no significant relationship was found between task orientation and emotional and physical exhaustion. No significant within-person relationships were found between ego orientation (where success is based on normative standards) and the three burnout variables. Glandorf et al. (2024) examined relationships between athlete burnout and several health variables. Results suggest that life satisfaction predicted decreases in total burnout, exhaustion, and a reduced sense of accomplishment at the within-person level. This means that high life satisfaction can be a significant resource for the athlete in reducing the symptoms of burnout.

Four different sport-environmental protective factors were investigated in one study each. DeFreese and Smiths’ (2014) study results provide preliminary longitudinal evidence that social perceptions are important to athletes’ psychological health and highlight the negative contribution of burnout perceptions to athletes’ life satisfaction. Scotto di Luzio et al. (2020) study results showed that athletes who were satisfied and emotionally connected in the sports community had lower scores of burnout. Fransen et al. (2022) study findings indicated that the identity leadership of athlete leaders was positively related to teammates’ well-being and negatively to their burnout, while the same relationships for coaches’ identity leadership were not significant. Shannon et al. (2022) longitudinal associations found evidence that higher levels of relatedness satisfaction at the beginning of a season related to lower levels of burnout later in the season and offered a protective effect.

Seven studies highlighted the negative effect on the athlete burnout (Crowell and Madigan, 2021; Květon et al., 2021; Madigan et al., 2015, 2016a, 2016b; Smith et al., 2018; Waleriańczyk and Stolarski, 2022). Longitudinal results showed that perfectionistic concerns predicted increases in athlete burnout over a three-month period of time (Madigan et al., 2015, 2016a). At the level of burnout dimensions, it was discovered that the perfectionistic concerns cognitions dimension predicted increases in the reduced sense of accomplishment and devaluation dimensions of burnout (Crowell and Madigan, 2021; Waleriańczyk and Stolarski, 2022). Smith et al. (2018) study concluded that socially prescribed perfectionism (which is considered an indicator of perfectionistic concerns) predicted changes in devaluation and devaluation predicted changes in socially prescribed perfectionism. However, socially prescribed perfectionism did not predict a burnout symptom for a sense of reduced accomplishment. Furthermore, Amemiya and Sakairi’s (2022) cross-lagged modeling showed that emotional exhaustion toward athletic practice predicted a future lack of personal accomplishment and devaluation among athletes, varying slightly depending on time. Frank et al. (2017) gathered information on burnout and depression, and after multiple linear regression analyses concluded that depression and burnout were both associated with chronic stress. Stress was a significantly better predictor for both burnout and depression than each was for the other. Isoard-Gautheu et al. (2015) study results of multilevel growth models revealed that during adolescence, reduced sense of accomplishment linearly decreased and was higher for girls than boys. Moreover, emotional/physical exhaustion increased then decreased, and seemed to have been attenuated at time points in which athletes also had higher levels of sport devaluation. Finally, sport devaluation increased over time with higher increases for girls than boys. Kelecek and Koruc (2022) study concluded that at the beginning of the season burnout positively correlated with competitive anxiety, but negatively correlated with coping strategies. In the middle of the season, there was only a positive correlation between burnout and competitive anxiety, and at the end of the season, there was a positive relationship between burnout and competitive anxiety. Studies on the effect of sleep on burnout in athletes have mixed results. In one of the studies, it was proven that sleep disruptions predicted increases in sports devaluation at the within-person level, so it can be added to one of the risk factors (Glandorf et al., 2024).

Five different sport-environmental risk factors were investigated in one study each. Athlete burnout can be influenced by interpersonal relationships and Mellano et al. (2022) have demonstrated a relationship between burnout and athletes’ perception of their coaches’ use of an autonomy-supportive style. The current study showed that all three dimensions of late-season burnout were significantly and negatively related to athletes’ perception of their coaches’ use of an autonomy-supportive style. Continuing on interpersonal relationships, DeFreese and Smith (2014) provided that study results provide preliminary longitudinal evidence that social perceptions are important to athletes’ psychological health and highlight the negative contribution of burnout perceptions to athletes’ life satisfaction. Negative social interactions were positively associated with global burnout and emotional/physical exhaustion but not with reduced accomplishment and devaluation across a sports season. Amemiya and Sakairi’s (2022) study proved that interpersonal exhaustion predicted a future lack of personal accomplishment and devaluation among athletes. Interpersonal exhaustion was the main burnout symptom that predicted future depressive symptoms among athletes. The competitive environment also is one of the risk factors for athlete burnout. Santos-Afonso et al. (2023) studied the experience of athletes before and after being in the National Camp for Development and Improvement of Handball Technique. The evidence shows that at the end of the camp, the athletes presented statistically higher means for all subscales of athlete burnout. Sorkkila et al. (2020) examined the development of school and sport burnout, therefore it was concluded that those elite athletes who are at risk of burnout might suffer particularly from school burnout symptoms, which then spill over into the sport context. The athletes in the Burnout risk profile showed a relatively high level of sport and school burnout symptoms at the beginning of upper secondary school, and the level of their school burnout symptoms remained relatively steady over 6 months. However, the level of sports burnout symptoms in this group decreased over time. In the developed burnout group, the athletes initially showed few sport and school burnout symptoms, although both kinds of symptoms increased significantly over a 6-month period.

Some of the included studies produced results that are reflected in this study as factors that may be influenced by athlete burnout. A total of three studies looked at the relationship between athlete burnout and sleep problems. Two of these studies investigated that athletes with clinically relevant burnout were more likely to report insomnia symptoms (Gerber et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). Moreover, baseline burnout symptoms predicted increased insomnia symptoms over time (Gerber et al., 2018). From these two studies, it can be concluded that athletes who already have some burnout symptoms are more likely to experience insomnia symptoms. Another factor that can be affected by athlete burnout is motivation. Study results suggest that athlete burnout predicts motivation over time, but motivation did not predict athlete burnout over time (Martinent et al., 2014). Glandorf et al. (2024) confirm the idea that burnout may be a developmental antecedent of depression. The results of their research showed that exhaustion predicted increases in depressive symptoms.

The current scoping review aimed to systematically examine longitudinal design studies to provide a methodological, conceptual, and applied overview of athlete burnout development and its associated factors. Specifically, the review provides an overview of 32 studies that examined athlete burnout in longitudinal design studies and contributing factors. The review gives a summary of study characteristics, measures and procedure analysis, athlete burnout change analysis, and an overview of factors related to athlete burnout. In total, 26 factors that are related to athlete burnout were identified and categorized into three categories—risk factors, protective factors, and factors that are affected by athlete burnout. There are also two subcategories for risk and protective factors—personal protective factors (e.g., perfectionistic strivings), sport-environmental protective factors (e.g., satisfaction and emotional connection with the sports community), personal risk factors (e.g., emotional exhaustion), and sport-environmental risk factors (e.g., coaches’ use of an autonomy-supportive style).

The Cognitive-Affective Model (CAM), Self-Determination Theory (SDT), and Commitment-Based Model (CBM) collectively provide a comprehensive lens through which burnout can be understood. For instance, CAM emphasizes the imbalance between a situation’s demands and the coping resources to deal with them, which can lead to stress. In this case, the athlete may experience demands from themselves and others involved in sports. Several studies proved that perfectionistic concerns (e.g., concerns over making mistakes) are significant predictors of the development of athlete burnout. Coaches and those involved in the organization must be careful when collaborating with athletes, especially when encouraging them to strive for excellence. Potential maladaptive manifestations of concerns, fears, and unrealistic expectations from the social environment must be closely observed (Květon et al., 2021). From the perspective of the sports environment, the imbalance can lead to emotional exhaustion, stress, and competitive anxiety (Amemiya and Sakairi, 2022; Frank et al., 2017; Kelecek and Koruc, 2022). All these factors are related to athlete burnout and its increase. These results support the CAM model’s claim that burnout is mostly predicted by stress and ineffective coping strategies, therefore suggesting specific stress management interventions. For example, mindfulness can significantly reduce stress (Amemiya and Sakairi, 2019; Zhang et al., 2023), additionally, confidence/motivation coping techniques can be used (Pires and Ugrinowitsch, 2021; Pires et al., 2016). Athletes engaged in task-oriented goals with a focus on self-referenced criteria might help to gain control regarding their sports involvement and mitigate the focus on normative standards (Ingrell et al., 2019). Resilience is another key factor in preventing burnout. Studies suggest that athletes equipped with resilience-related skills better cope with setbacks and are less likely to drop out of sports due to burnout (Sorkkila et al., 2019; Ueno and Suzuki, 2016). In tandem, mental toughness has emerged as a vital predictor of reduced burnout symptoms, including emotional and physical exhaustion (Madigan and Nicholls, 2017). Other techniques that may influence athlete burnout were also investigated in other studies, such as gratitude, which indirectly affects athlete burnout through athlete engagement (Crowell and Madigan, 2021).

According to SDT, the satisfaction of the core human needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fundamental for optimal psychological well-being and human functioning (Gustafsson et al., 2017). Therefore, athletes’ perception of their coaches’ use of an autonomy-supportive style is one of the risk factors. Athletes who perceive their coaches as supportive in fostering independence and emotional well-being are less likely to experience burnout. In addition, coaches’ use of punishment-oriented feedback was found to be positively related to athletes’ late-season levels of physical and emotional exhaustion (Mellano et al., 2022). Coach and his coaching behavior also play a significant role in this athlete burnout context. It was demonstrated that coaches’ behaviors can be a predictor of athletes’ burnout levels in all three of the subdimensions (Mellano et al., 2022). Coaches can also influence the competitive environment. For example, during a competitive season, coaches can establish an atmosphere that supports an athlete’s sense of independence and choice (Mellano et al., 2022). When pushing athletes to pursue excellence, others must use extreme caution to avoid creating maladaptive expressions of worries, fears, and irrational expectations from the social environment. The athlete’s need for connection and belonging is an essential element according to SDT. Negative social interactions (characterized by unwanted, intrusive, unhelpful, unsympathetic or insensitive, or rejecting or neglecting behaviors) fall under interpersonal relationships, a key factor in athlete burnout that is associated with emotional and physical exhaustion (DeFreese and Smith, 2014). Specific interpersonal exhaustion is one of the main burnout symptoms. Relatedness satisfaction is important for athletes, and higher levels of athletes’ relatedness satisfaction at the beginning of a season are related to a lower level of burnout later in the season (Shannon et al., 2022). Moreover, social support is crucial because it helps to satisfy the need for connection and is negatively associated with athlete burnout and emotional/physical exhaustion (DeFreese and Smith, 2014). Thus, athletes who receive greater social support and experience a higher level of life satisfaction are less prone to the detrimental effects of prolonged stress and competition demands, making it a crucial factor to consider in holistic athlete development (Glandorf et al., 2024).

In particular, SDT is a helpful theoretical framework for examining the possible motivational causes of athlete burnout. The included study suggests that burnout can cause a lack of motivation, however, it conflicts with other studies suggesting that amotivation can predict athlete burnout symptoms (Martinent et al., 2014). Because of the relatively short data collection period (2 months), there may not have been as much diversity in burnout in this study, which could have hidden increases in burnout among athletes who exhibit higher levels of amotivation. The interval between repeated measurements could also be the basis for the mixed results regarding the relationship between sleep problems and athlete burnout. Two of the three studies found that athlete burnout affects sleep, but sleep does not affect burnout symptoms. The main finding is that instead of being viewed as a result of symptoms of sleeplessness, burnout could be considered a cause. Athletes with clinically relevant burnout symptoms report significantly more insomnia symptoms, report more dysfunctional sleep-related cognitions, spend less time in bed during weekday nights, and report higher sleep-onset latency, both during weeknights and weekend nights (Gerber et al., 2018). One explanation could be that burnout is a symptom of stress, and stress is known to cause sleep issues. It can also be explained by the fact that athletes with high burnout levels tend to worry more about everything related to the training and competition process, which in turn can result in poor sleep quality (Li et al., 2018). The third study obtained opposite results, concluding that sleep disruptions predicted increases in sports devaluation (Glandorf et al., 2024). The difference in results is also explained by the fact that there could be other external factors that influence the results, for example, no information was collected on whether the participant uses any sleep medication or information on how the participant evaluates the quality of his sleep. Depression is another component that is discussed in the literature. The study included in this review demonstrated a unidirectional relationship between athlete burnout and depressive symptoms. Specifically, it was proven that exhaustion predicted increases in depressive symptoms (Glandorf et al., 2024). However, the results of other studies indicate that this relationship is bidirectional.

From The Commitment-based model perspective, factors that affect individuals’ perceptions of their involvement in sports would be included in this category. For instance, perfectionistic strivings appear to be a protective factor for athlete burnout, since commitment is based on attraction (“want to”) or entrapment (“have to”). Identity can influence this commitment. Identity leadership (encompassing identity prototypicality, advancement, entrepreneurship, and impresarioship) and team identification were positively related to teammates’ well-being and negatively to their burnout, however, coaches’ identity impresarioship was not significant. It was concluded that empowering athlete leaders and strengthening their identity leadership skills is an important way to unlock sports teams’ full potential (Fransen et al., 2022). Similarly, satisfaction and emotional connection are negatively associated with athlete burnout, nevertheless, a sense of belonging was positively associated with a reduced sense of accomplishment, and emotional connection with peers was positively linked to physical exhaustion (Shannon et al., 2022). The authors suggest that an overly strong sense of belonging to the community may undermine athletes’ autonomy, potentially leading to feelings of inefficacy in their sports performance and accomplishments. Another explanation relates to athletes’ sense of belonging within the intensive training center environment, which may diminish the perceived importance of accomplishments and increase motivation to train and perform out of a desire to avoid shame or guilt (Scotto di Luzio et al., 2020). In this regard, the relationship between coaches and athletes is crucial (Mellano et al., 2022). Coaches, in particular, should consider this while considering how to best deliver feedback to their athletes. They should attempt to use feedback that positively acknowledges their players’ accomplishments and minimize the frequency of punishment-based comments (Mellano et al., 2022).

The inclusion of only longitudinal studies strengthens the validity of this review by enabling insights into burnout’s progression over time. Unlike cross-sectional designs, longitudinal approaches allow for the examination of causal relationships and temporal changes, as evidenced by studies demonstrating significant increases in burnout dimensions such as sport devaluation during competitive seasons (Pires and Ugrinowitsch, 2021). The research procedure and the interval between repeated measurements also determine whether it will be possible to observe changes. The variability in measurement intervals across studies—ranging from 1 month to 1 year proposes—challenges in establishing optimal monitoring frequencies. Two research with a one-month interval found that neither the overall burnout nor any of the burnout dimensions changed significantly between waves. No athlete experienced a progressive increase in athlete burnout over time (Martinent et al., 2014, 2020). This result was explained by the fact that this interval is too short, as well as the fact that the data were collected towards the end of the season. So, not only the interval is important, but also the part of the season in which the data is collected. If the data is collected at the end of the season, it is possible that athlete burnout scores might have already attained their highest levels, leading to stabilization. Research suggests that a three-month interval, particularly when aligned with sports season phases, provides a balanced approach to capturing meaningful changes (Madigan et al., 2016a). Linking data collection to the phases of the sports season (e.g., beginning, middle, and end) ensures that the study considers season-specific factors that may influence athlete burnout. This approach helps to better understand how burnout symptoms increase or decrease depending on the stage of the season. It is most often observed that at the end of the season, the burnout of athletes becomes more pronounced compared to the beginning of the season (Kelecek and Koruc, 2022). A person-oriented approach is also an important aspect. In longitudinal studies, this appears as regular monitoring of burnout factors in order to be able to notice individual changes in the dynamics of burnout among athletes. It helps identify temporary changes and determine whether these changes are long-term or short-term.

Given the multidimensional nature of burnout, it is challenging to determine whether an athlete must exhibit high levels across all burnout dimensions or in just one dimension to be classified as experiencing burnout. Therefore, the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire provides an opportunity to analyze each of the dimensions separately and helps to draw correct conclusions. This is crucial when thinking about monitoring athlete burnout because studies have observed that each of these dimensions does not develop simultaneously, they vary over time, as well as influence each other. Since ABQ is a self-reported measurement, that can cause potential biases, including social desirability and recall inaccuracies. Future research should consider complementing self-reports with objective measures (e.g., physiological indicators of stress) to enhance reliability.

Findings from the reviewed studies underscore the importance of early detection and personalized interventions. For example, the protective role of mindfulness and resilience in mitigating burnout symptoms suggests that integrating mental skills training into athletes’ routines could be a valuable preventative strategy (Amemiya and Sakairi, 2019; Sorkkila et al., 2019). Programs focusing on mindfulness, gratitude, and mental toughness have shown promise in enhancing coping resources and reducing stress, aligning with CAM’s emphasis on resource-demand balance.

From a coaching perspective, the detrimental impact of punitive feedback and the protective influence of autonomy-supportive behaviors (Mellano et al., 2022) highlight the need for coach education programs. Such programs should aim to develop coaches’ skills in delivering constructive feedback, fostering athlete autonomy, and building emotionally supportive relationships. Moreover, organizational interventions that address systemic stressors, such as high competition demands and inadequate recovery periods, are crucial in creating a supportive environment for athletes.

This scoping review provides a summary of the psychological factors associated with athlete burnout that have been studied over the past 10 years. Despite the progress made, significant gaps remain in understanding athlete burnout. The limited examination of factors such as cultural differences, gender, and the interplay between personal and environmental influences warrants further investigation. For instance, studies have shown that female athletes may experience higher burnout rates in certain dimensions, such as emotional exhaustion and sport devaluation, compared to their male counterparts (Isoard-Gautheu et al., 2015). Exploring these variations can inform tailored interventions.

While all studies utilized repeated measurements, the intervals between these measurements varied, and different questionnaires were employed to assess athlete burnout. Due to the significant variability in longitudinal designs, it is not appropriate to draw definitive conclusions about the psychological factors that contribute most significantly to athlete burnout or its progression over time. Another limitation is that several psychological factors were examined in only one or a limited number of studies, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about their impact on athlete burnout. The limitations of the other included studies can also be added to the limitations of this study. All studies used only self-report questionnaires. That means that only a partial view of the phenomenon can be gained because there could be other factors that there was no way to control. Studies were conducted on a specific population, for example, adolescent handball players, or on the other hand were conducted on a wide range of athletes competing in various sports, which might limit the generalizability of the findings. Also, in some of the research there was a small number of participants and in others was an unbalanced number of athletes from individual and team sports.

Additionally, the high dropout rates observed in longitudinal studies highlight the need for strategies to improve participant retention. Incorporating digital tools for remote monitoring and gamification elements to enhance engagement could address this challenge. Lastly, qualitative research capturing athletes’ lived experiences of burnout would complement quantitative findings, providing a more holistic understanding of this complex phenomenon.

This scoping review of longitudinal studies on athlete burnout provides valuable insights into the complex and dynamic nature of this phenomenon. The review demonstrates that athlete burnout evolves in a nonlinear manner and can be understood either holistically through its total score or by examining its specific dimensions—emotional and physical exhaustion, reduced sense of accomplishment, and sport devaluation. These dimensions often develop independently, underscoring the multidimensional nature of burnout.

The analysis highlights the importance of consistent athlete burnout monitoring as the most effective means of capturing the dynamics of athlete burnout and the interplay between environmental and personal factors. The findings indicate that it is significant to choose a measurement tool suitable for the sample, which includes all dimensions of burnout since it is essential to analyze each of these dimensions separately to obtain the most accurate results. Additionally, determining an appropriate interval between repeated measurements is crucial. Such intervals should adopt a person-oriented approach to accurately capture the dynamics of athlete burnout. This involves considering the stage of the competitive season and how many months are between stages of the season (e.g., 3 months between the beginning and midpoint of the season). Moreover, it is also important to choose a long-term interval to be able to assess whether the existing burnout changes are only short-term or persist in the long-term. Accurate and systematic monitoring can play a pivotal role in mitigating the risk of burnout by enabling timely interventions.

From the results obtained, it was concluded that a range of factors contributes to the onset and progression of athlete burnout. Identifying risk factors (e.g., perfectionistic concerns, negative social interactions) and protective factors (e.g., social support, mental toughness) can be useful in developing interventions for athlete burnout. It is important to note that when developing interventions, it is essential to pay attention not only to the fact that they incorporate several syndromes but also to the fact that they depend on the time of year (considering the competition season). These findings hold significant practical implications for stakeholders in the sports domain, including coaches, athletes, and sports psychologists, by facilitating the adoption of proactive strategies for early recognition and effective intervention.

In conclusion, this review underscores the necessity for continued longitudinal research to deepen our understanding of athlete burnout and inform the development of targeted interventions. By fostering a supportive environment and addressing both individual and contextual risk factors, it is possible to reduce the prevalence of burnout and enhance athlete well-being and performance.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

BD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Writing – review & editing. JK: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Rīga Stradiņš University, Department of Health Psychology and Paedagogy, Faculty of Health and Sports Sciences.

I acknowledged the use of ChatGPT [https://chatgpt.com/] to identify improvements in the writing style.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. To identify improvements in the writing style of the manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1502174/full#supplementary-material

Amemiya, R., and Sakairi, Y. (2019). The role of mindfulness in performance and mental health among Japanese athletes: an examination of the relationship between alexithymic tendencies, burnout, and performance. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 14, 456–468. doi: 10.14198/jhse.2019.142.17

Amemiya, R., and Sakairi, Y. (2022). Examining the relationship between depression and the progression of burnout among Japanese athletes 1, 2. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 64, 373–384. doi: 10.1111/jpr.12332

Amemiya, R., Ueno, Y., and Shimizu, Y. (2013). The study of athletic burnout for university athletes: Development of a new university athletes’ burnout scale. Jpn. J. Sport Psychol. 10, 51–61.

American Psychological Association (2018). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Cresswell, S. L., and Eklund, R. C. (2005). Motivation and burnout in professional rugby players. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 76, 370–376. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2005.10599309

Crowell, D., and Madigan, D. J. (2021). Perfectionistic concerns cognitions predict burnout in college athletes: a three-month longitudinal study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 20, 532–550. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2020.1869802

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19, 109–134.

De Francisco, C., Gómez-Guerra, C., Vales-Vázquez, Á., and Arce, C. (2022). An analysis of Schmidt and Stein’s sport commitment model and athlete profiles. Sustain. For. 14:1740. doi: 10.3390/su14031740

DeFreese, J. D., Raedeke, T. D., and Smith, A. L. (2015). “Athlete burnout: an individual and organizational phenomenon” in Applied sport psychology: personal growth to peak performance. eds. J. M. Williams and V. Krane (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education), 444.

DeFreese, J. D., and Smith, A. L. (2014). Athlete social support, negative social interactions, and psychological health across a competitive sport season. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 36, 619–630. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2014-0040

Eklund, R. C., and DeFreese, J. D. (2020). “Athlete burnout” in Handbook of sport psychology. eds. G. Tenenbaum, R. C. Eklund, and N. Boiangin (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1220–1240.

Frank, R., Nixdorf, I., and Beckmann, J. (2017). Analyzing the relationship between burnout and depression in junior elite athletes. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 11, 287–303. doi: 10.1123/JCSP.2017-0008

Fransen, K., Boen, F., Haslam, S. A., McLaren, C. D., Mertens, N., Steffens, N. K., et al. (2022). Unlocking the power of ‘us’: longitudinal evidence that identity leadership predicts team functioning and athlete well-being. J. Sports Sci. 40, 2768–2783. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2023.2193005

Gerber, M., Best, S., Meerstetter, F., Isoard-Gautheur, S., Gustafsson, H., Bianchi, R., et al. (2018). Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between athlete burnout, insomnia, and polysomnographic indices in young elite athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 40, 312–324. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2018-0083

Glandorf, H. L., Madigan, D. J., Kavanagh, O., and Mallinson-Howard, S. H. (2023). Mental and physical health outcomes of burnout in athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol., 1–45. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2023.2225187

Glandorf, H. L., Madigan, D. J., Kavanagh, O., Mallinson-Howard, S. H., Donachie, T. C., Olsson, L. F., et al. (2024). Athlete burnout and mental and physical health: a three-wave longitudinal study of direct and reciprocal effects. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 13, 412–431. doi: 10.1037/spy0000355

Guo, Z., Yang, J., Wu, M., Xu, Y., Chen, S., and Li, S. (2022). The associations among athlete gratitude, athlete engagement, athlete burnout: a cross-lagged study in China. Front. Psychol. 13:996144. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.996144

Gustafsson, H., DeFreese, J. D., and Madigan, D. J. (2017). Athlete burnout: review and recommendations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 16, 109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.05.002

Hassmén, P., Webb, K., and Stevens, C. J. (2023). Athlete burnout and perfectionism in objectively and subjectively assessed sports. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 18, 2251–2258. doi: 10.1177/17479541221132913

Ingrell, J., Johnson, U., and Ivarsson, A. (2019). Developmental changes in burnout perceptions among student-athletes: an achievement goal perspective. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 17, 509–520. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2017.1421679

Isoard-Gautheu, S., Guillet-Descas, E., Gaudreau, P., and Chanal, J. (2015). Development of burnout perceptions during adolescence among high-level athletes: a developmental and gendered perspective. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 37, 436–448. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2014-0251

Kelecek, S., and Koruc, Z. (2022). Competitive anxiety and burnout: a longitudinal study. Acta Med. Mediterr. 38, 2333–2339. doi: 10.19193/0393-6384_2022_4_354

Kinoshita, K., Sato, S., and Sugimoto, D. (2023). Conceptualisation, measurement, and associated factors of eudaimonic well-being of athletes: a systematic review. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 22, 1877–1907. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2023.2246055

Květon, P., Jelínek, M., and Burešová, I. (2021). The role of perfectionism in predicting athlete burnout, training distress, and sports performance: a short-term and long-term longitudinal perspective. J. Sports Sci. 39, 1969–1979. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2021.1911415

Lerman, Y., Melamed, S., Shargin, Y., Kushnir, T., Rotgoltz, Y., Shirom, A., et al. (1999). The association between burnout at work and leukocyte adhesiveness/aggregation. Psychosom. Med. 61, 828–833

Li, C., Ivarsson, A., Stenling, A., and Wu, Y. (2018). The dynamic interplay between burnout and sleep among elite blind soccer players. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 37, 164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.08.008

Lin, C. H., Lu, F. J., Chen, T. W., and Hsu, Y. (2022). Relationship between athlete stress and burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 20, 1295–1315. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2021.1987503

Madigan, D. J., and Nicholls, A. R. (2017). Mental toughness and burnout in junior athletes: a longitudinal investigation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 32, 138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.07.002

Madigan, D. J., Olsson, L. F., Hill, A. P., and Curran, T. (2022). Athlete burnout symptoms are increasing: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of average levels from 1997 to 2019. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 44, 153–168. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2020-0291

Madigan, D. J., Stoeber, J., and Passfield, L. (2015). Perfectionism and burnout in junior athletes: a three-month longitudinal study. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 37, 305–315. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2014-0266

Madigan, D. J., Stoeber, J., and Passfield, L. (2016a). Motivation mediates the perfectionism–burnout relationship: a three-wave longitudinal study with junior athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 38, 341–354. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2015-0238

Madigan, D. J., Stoeber, J., and Passfield, L. (2016b). Perfectionism and changes in athlete burnout over three months: interactive effects of personal standards and evaluative concerns perfectionism. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 26, 32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.05.010

Mak, S., and Thomas, A. (2022). Steps for conducting a scoping review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 14, 565–567. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1

Martinent, G., Decret, J. C., Guillet-Descas, E., and Isoard-Gautheur, S. (2014). A reciprocal effects model of the temporal ordering of motivation and burnout among youth table tennis players in intensive training settings. J. Sports Sci. 32, 1648–1658. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.912757

Martinent, G., Louvet, B., and Decret, J. C. (2020). Longitudinal trajectories of athlete burnout among young table tennis players: a 3-wave study. J. Sport Health Sci. 9, 367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.09.003

Maslach, C., and Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory. 2nd Edition, Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Mellano, K. T., Horn, T. S., and Mann, M. (2022). Examining links between coaching behaviors and collegiate athletes’ burnout levels using a longitudinal approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 61:102189. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102189

Nixdorf, I., Beckmann, J., and Nixdorf, R. (2020). Psychological predictors for depression and burnout among German junior elite athletes. Front. Psychol. 11:601. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00601

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 18:e1003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

Pires, D. A., Debien, P. B., Coimbra, D. R., and Ugrinowitsch, H. (2016). Burnout and coping among volleyball athletes: a longitudinal analysis. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 22, 277–281. doi: 10.1590/1517-869220162204158756

Pires, D. A., and Ugrinowitsch, H. (2021). Burnout and coping perceptions of volleyball players throughout an annual sport season. J. Hum. Kinet. 79, 249–257. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2021-0078

Pollock, D., Peters, M. D., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Alexander, L., Tricco, A. C., et al. (2023). Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synthesis 21, 520–532. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-22-00123

Raedeke, T. D. (1997). Is athlete burnout more than just stress? A sport commitment perspective. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 19, 396–417. doi: 10.1123/jsep.19.4.396

Raedeke, T. D., and Smith, A. L. (2001). Development and preliminary validation of an athlete burnout measure. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 23, 281–306. doi: 10.1123/jsep.23.4.281

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., and Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School burnout inventory (SBI) reliability and validity. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 25, 48–57. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.48

Santos-Afonso, M. D., Lourenção, L. G., Afonso, M. D. S., Saes, M. D. O., Santos, F. B. D., Penha, J. G. M., et al. (2023). Burnout syndrome in selectable athletes for the Brazilian handball team—children category. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:3692. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043692

Schmidt, G. W., and Stein, G. L. (1991). Sport commitment: a model integrating enjoyment, dropout, and burnout. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 13, 254–265. doi: 10.1123/jsep.13.3.254

Scotto di Luzio, S., Martinent, G., Guillet-Descas, E., and Daigle, M. P. (2020). Exploring the role of sport sense of community in perceived athlete burnout, sport motivation, and engagement. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 32, 513–528. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2019.1575298

Shannon, S., Prentice, G., Brick, N., Leavey, G., and Breslin, G. (2022). Longitudinal associations between athletes’ psychological needs and burnout across a competitive season: a latent difference score analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 44, 240–250. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2021-0250

Smith, E. P., Hill, A. P., and Hall, H. K. (2018). Perfectionism, burnout, and depression in youth soccer players: a longitudinal study. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 12, 179–200. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2017-0015

Smith, R. E. (1986). Toward a cognitive-affective model of athletic burnout. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 8, 36–50. doi: 10.1123/jsp.8.1.36

Sorkkila, M., Aunola, K., and Ryba, T. V. (2017). A person-oriented approach to sport and school burnout in adolescent student-athletes: The role of individual and parental expectations. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 28, 58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.10.004

Sorkkila, M., Ryba, T. V., Selänne, H., and Aunola, K. (2020). Development of school and sport burnout in adolescent student-athletes: a longitudinal mixed-methods study. J. Res. Adolesc. 30, 115–133. doi: 10.1111/jora.12453

Sorkkila, M., Tolvanen, A., Aunola, K., and Ryba, T. V. (2019). The role of resilience in student-athletes' sport and school burnout and dropout: a longitudinal person-oriented study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 29, 1059–1067. doi: 10.1111/sms.13422

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Ueno, Y., and Suzuki, T. (2016). Longitudinal study on the relationship between resilience and burnout among Japanese athletes. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 16:1137. doi: 10.7752/jpes.2016.04182

Waleriańczyk, W., and Stolarski, M. (2022). Perfectionism, athlete burnout, and engagement: a five-month longitudinal test of the 2×2 model of perfectionism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 195:111698. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111698

Wilczyńska, D., Qi, W., Jaenes, J. C., Alarcón, D., Arenilla, M. J., and Lipowski, M. (2022). Burnout and mental interventions among youth athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:10662. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710662

Keywords: burnout, athlete, longitudinal, sport, psychology

Citation: Dišlere BE, Mārtinsone K and Koļesņikova J (2025) A scoping review of longitudinal studies of athlete burnout. Front. Psychol. 16:1502174. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1502174

Received: 26 September 2024; Accepted: 30 January 2025;

Published: 14 February 2025.

Edited by:

Dominika Maria Wilczyńska, University WSB Merito Gdańsk, PolandReviewed by:

Iuliia Pavlova, Lviv State University of Physical Culture, UkraineCopyright © 2025 Dišlere, Mārtinsone and Koļesņikova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beate Evelīna Dišlere, QmVhdGVFdmVsaW5hLkRpc2xlcmVAcnN1Lmx2

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.