- 1School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 2Centre for Motor Control, Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Community and Behavioral Health Sciences, Institute of Public and Preventative Health, School of Public Health, Augusta University, Augusta, GA, United States

- 4Academic and Research Collaborative in Health and CERI, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 5Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics and Gerontology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 6Atlanta VA Center for Visual and Neurocognitive Rehabilitation, Decatur, GA, United States

- 7Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Decatur, GA, United States

Introduction

Dance provides therapeutic benefits for people with Parkinson's disease (PD) across motor and non-motor domains, including gait, mobility, mood, and cognition (McNeely et al., 2015; Shanahan, 2015; Bek et al., 2020; Carapellotti et al., 2020; Emmanouilidis et al., 2021). As a low-cost and widely accessible activity, dance can be a valuable adjunct to standard clinical treatment for PD. Digital provision of dance for PD has expanded significantly, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Bek et al., 2021a; Kelly and Leventhal, 2021; Morris et al., 2021, 2023). There is an ongoing need for accessible digital platforms for therapeutic activities like dance (Ellis and Earhart, 2021; Kelly and Leventhal, 2021) to provide for the growing PD population (Dorsey et al., 2018), including those in rural and remote communities without access to in-person programs. This article considers key challenges and potential solutions in digital dance for PD.

Current evidence on the feasibility and outcomes of digital dance programs for PD

Preliminary evidence indicates that online dance can be safe and feasible for individuals with mild to moderate PD, showing good rates of attendance and adherence and no adverse events (Morris et al., 2021, 2023; Walton et al., 2022; Pinto et al., 2023; Delabary et al., 2024a). Advantages of the digital format noted by people with PD include the convenience of not traveling and the ability to practice more frequently (Bek et al., 2021a; Ghanai et al., 2021). Participants report enjoyment of digital classes (Morris et al., 2021; Walton et al., 2022) and a desire to continue with online dance alongside in-person classes (Bek et al., 2021a; Delabary et al., 2024b), as also noted for exercise classes (Bennett et al., 2023) and singing therapy (Tamplin et al., 2024) for PD.

Live online dance participation has been associated with improvements in functional mobility, anxiety, and depression (Shanahan et al., 2017; Walton et al., 2022; Pinto et al., 2023), affect (Ghanai et al., 2021), and quality of life (Walton et al., 2022) in people with PD. Participants with PD engaging in live and/or recorded digital dance programs during the pandemic self-reported multiple motor (e.g., balance, posture) and non-motor (e.g., mood, confidence) benefits (Bek et al., 2021a).

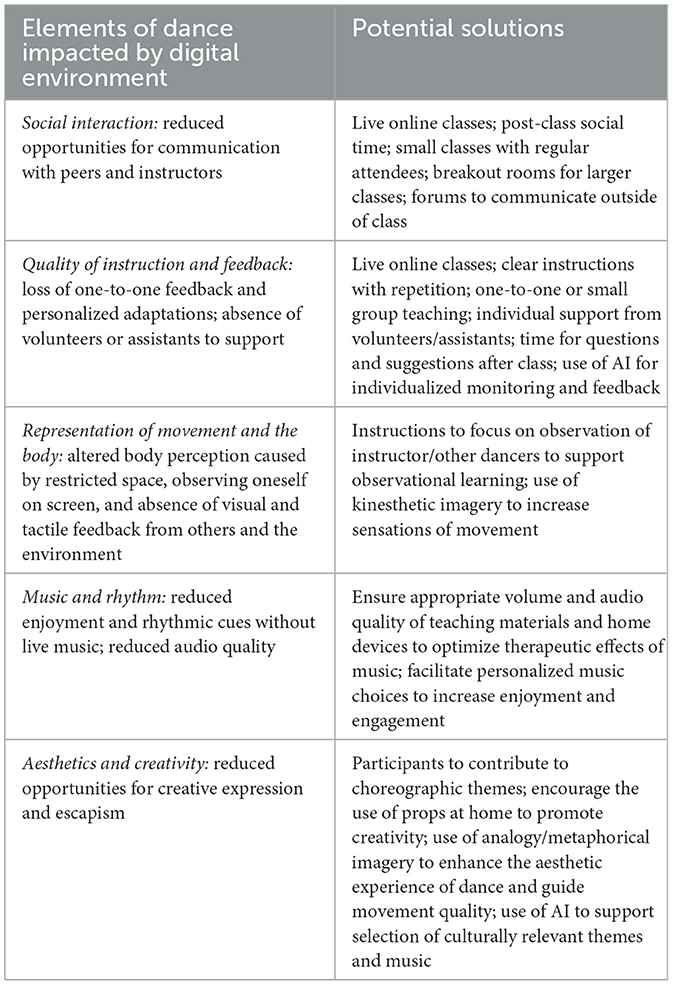

Digital formats thus show promise as a feasible and effective approach to dance for PD. However, the literature is limited, including small samples and different modes of delivery. As practice and research in this field continue expanding, it is important to consider how the digital environment might impact therapeutic benefits of dance programs. Dance is a multidimensional activity (Dhami et al., 2015; Christensen et al., 2017; Bek et al., 2022a) incorporating physical, cognitive, social, affective, and creative components that contribute to outcomes for people with PD. The following section outlines therapeutic elements of dance that differ between in-person and digital contexts, with possible solutions to address limitations and optimize the experience and outcomes of digital dance programs. Table 1 summarizes the key challenges and solutions.

Therapeutic elements of dance that may be impacted in the digital environment

Social interaction

The extent and nature of social interaction is altered by the absence of a group or partner in the digital environment (Bek et al., 2021a; Ghanai et al., 2021; Walton et al., 2022). Qualitative reports indicate that participants value the peer support, social comparison (Walton et al., 2022; Senter et al., 2024), and physical contact (Rocha et al., 2017; Delabary et al., 2024b) provided by in-person classes. Although enjoyment from social interactions can be compromised in digital programs (Emmanouilidis et al., 2021), meaningful social engagement can still be achieved. For example, virtual coffee time after class provides opportunities for discussion, questions, and feedback (Delabary et al., 2024b). Smaller live online classes with regular participants could also create a sense of community (Bek et al., 2022b). Social interaction in large classes could be supported by using “breakout” groups to facilitate discussion after class or by providing an online forum to promote interaction outside of classes.

Quality of instruction and feedback

The effectiveness of instruction in the digital environment may be limited by factors including video/audio quality, viewing perspectives, and interaction with instructors (Bek et al., 2021a, 2022b; Delabary et al., 2024b; Tamplin et al., 2024). Feedback is important to ensure that movements are performed safely, to provide necessary adaptations, and to facilitate learning. A qualitative review of in-person dance for PD highlighted the value of the instructor-participant relationship (Senter et al., 2024). In contrast, reduced interaction with the instructor and the loss of one-to-one support were cited by participants with PD as disadvantages of digital classes (Bek et al., 2021a). These limitations may impact participants' motivation and confidence to engage as well as the potential for learning.

Quality instruction may be maintained in the digital environment through optimizing aspects of class design and production, such as slowing the teaching pace and repeating instructions (Delabary et al., 2024b). Live online classes are critical to enable participants to receive feedback. To facilitate high-quality feedback in digital programs, instructors could consider one-to-one or small group classes with volunteers or assistants to support participants during class. Participants should have opportunities to ask the instructor questions or make suggestions after class, which could be combined with social/coffee time (Bek et al., 2022a; Delabary et al., 2024b).

Representation of movement and the body

Dancers frequently observe, imitate, mirror, and coordinate with others' movements (Blasing et al., 2012; Bek et al., 2020). These processes engage the brain's motor system to facilitate movement and learning (Hardwick et al., 2018; Chye et al., 2022). Interventions based on action observation and motor imagery have shown positive effects in PD (Caligiore et al., 2017; Bek et al., 2021b; Mezzarobba et al., 2024), and qualitative data suggest that observation and imagery may be effectively implemented within dance for PD (Bek et al., 2022a). Additionally, awareness of the body is an important element of dance, and in-person dance training may enhance body awareness in PD (Hadley et al., 2020). Body perception may be altered in the digital space (Delabary et al., 2024a), for example through seeing oneself on screen or having a more restricted area within which to move.

Self-report data indicates that many people with PD can engage in observational learning and use imagery to enhance the outcomes of digital dance participation (Bek et al., 2021a, 2022b). These processes could be supported in digital programs through specific instructions to increase attention to the movements of the instructor and other dancers and by encouraging participants to imagine the sensations of the demonstrated movements (i.e., kinesthetic imagery).

Music and rhythm

Music and rhythm are integral to most forms of dance and may contribute to beneficial effects for people with PD. Rhythmic cueing can support gait in people with PD (de Dreu et al., 2011; Nombela et al., 2013). Music promotes dopamine release in the basal ganglia (Salimpoor et al., 2011), and the beneficial effects of music in PD extend beyond rhythm to influence affect and motivation (Karageorghis et al., 2020; Tamplin et al., 2020, 2024). Music can also evoke motor imagery in people with PD (Poliakoff et al., 2023), and participants could potentially utilize the music from dance classes as an internalized cue to support movement in daily life (Bek et al., 2022a; Jola et al., 2022). People with PD enjoy the music accompanying dance classes and have expressed a preference for live music (Ghanai et al., 2021), which participants miss when dancing at home (Bek et al., 2021a).

In a recent study examining the feasibility of a one-on-one digital dance program for PD, participants worked with the instructor to select music for classes (Morris et al., 2021). Although it may be difficult to effectively tailor music to preferences in a group online class, different choices could be accommodated across a series of classes. Instructors should ensure appropriate music quality and volume (Delabary et al., 2024b), and participants could be supported to optimize the audio settings of their devices.

Aesthetics and creativity

The creative aspects of dance differentiate it from other forms of physical activity (Rocha et al., 2017; Fontanesi and DeSouza, 2021; Bek et al., 2022a). Dance programs for PD often feature communicative expressions and gestures, storytelling, and props. Qualitative data indicate that participants enjoy the creativity and escapism offered by dance (Bek et al., 2022a; Walton et al., 2022) and that artistic aspects of dance are diminished in the digital environment (Walton et al., 2022). Additionally, skin conductance measures have indicated that dance may increase physiological arousal compared to an exercise program of similar aerobic intensity (Fontanesi and DeSouza, 2021), suggesting an emotional response to the artistic experience of dance. To enhance the aesthetic and creative dimensions of digital dance programs, participants could be encouraged to contribute to choreographic themes and stories or use props during home practice. Instruction could also incorporate analogy and metaphorical imagery, which has been associated with positive outcomes of digital dance participation (Bek et al., 2021a).

Future directions for research and development

Further to the therapeutic elements of dance discussed above, there are important practical considerations in designing digital programs. Ensuring safety in the digital environment is critical, particularly considering gait and balance difficulties in PD, which can increase fall risk (Camicioli et al., 2023). People with PD who attend dance classes are at different stages of disease progression and can have different needs. They may also have different infrastructures at home to support online physical activity. It is important for health professionals and instructors to ensure that participants are safe to engage in home-based dance training, particularly those with greater disease severity who experience postural instability. Checklists have been devised to assist this process (see Morris et al., 2021, 2023). It is also advisable to use a checklist before each session to assess safety of the home environment and note procedures for dealing with adverse events.

Technical barriers relating to the hardware, software, or connectivity required for online classes must also be considered for both participants and instructors (Bek et al., 2021a, 2022b; Walton et al., 2022; Delabary et al., 2024b). To increase the accessibility of dance programs, alternative options could be offered to accommodate different abilities and preferences. While most participants may prefer live online classes that provide greater social interaction, others prefer recorded videos that offer flexibility and enable self-paced or repeated practice, or appreciate having both live and recorded options (Bek et al., 2021a). Pre-recorded DVDs or dance instruction by telephone1 could provide valuable resources for individuals in rural communities without reliable internet access or a suitable electronic device, and these should also incorporate appropriate safety checks. A choice of different digital platforms for accessing classes could also increase participation by providing options that participants are familiar with (Delabary et al., 2024b). Participants could also be supported with training or guidance to use the required technology before joining a program.

Involving people with PD in the co-design and development of programs increases the relevance and could enhance outcomes of therapeutic activities like dance (Quinn et al., 2010; Morris et al., 2021; Bek et al., 2022a). Participant input is particularly valuable in digital programming to understand specific preferences, needs, and challenges. High levels of attendance and enjoyment of co-designed online dance classes have been reported (Morris et al., 2021), and patient input can enhance the accessibility and usability of digital technology platforms for home-based training (Bek et al., 2021b).

Finally, future research and development should capitalize on the opportunities offered by artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance and personalize digital therapies (Amjad et al., 2023), including the possibility to provide participants, dance instructors, and healthcare professionals with performance data and feedback. For example, computer vision and machine learning techniques could be used to measure changes or improvements in movement and adjust programs to align with individuals' ability levels. Participants could also receive individualized encouragement and guidance. AI could also allow instructors to tailor classes to different languages, cultures, and geographical locations, for example through translating instructions or suggesting culturally relevant music and themes.

Conclusions

Current evidence indicates that digital dance is feasible and enjoyable for many people with PD, and preliminary findings suggest that positive outcomes can be achieved in the online environment. Digital platforms can increase the reach of dance programs, although barriers to access remain. However, the evidence so far is limited to small-scale studies and self-report data, and the outcomes of digital and in-person programs have not been directly compared. Further research is needed to understand the impact of digital dance across domains and at different disease stages, including longer-term outcomes. In the meantime, this article outlines possible solutions to help maintain therapeutic benefits of dance in the digital environment.

Author contributions

JB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DJ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. JB was supported by funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101034345.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^These options are already offered by Dance for PD® https://danceforparkinsons.org/.

References

Amjad, A., Kordel, P., and Fernandes, G. (2023). A review on innovation in healthcare sector (Telehealth) through artificial intelligence. Sustainability 15:6655. doi: 10.3390/su15086655

Bek, J., Arakaki, A. I., Derbyshire-Fox, F., Ganapathy, G., Sullivan, M., Poliakoff, E., et al. (2022a). More than movement: exploring motor simulation, creativity, and function in co-developed dance for Parkinson's. Front. Psychol. 13:731264. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.731264

Bek, J., Arakaki, A. I., Lawrence, A., Sullivan, M., Ganapathy, G., Poliakoff, E., et al. (2020). Dance and Parkinson's: a review and exploration of the role of cognitive representations of action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 109, 108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.12.023

Bek, J., Groves, M., Leventhal, D., and Poliakoff, E. (2021a). Dance at home for people with Parkinson's during COVID-19 and beyond: participation, perceptions, and prospects. Front. Neurol. 12:678124. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.678124

Bek, J., Holmes, P. S., Craig, C. E., Franklin, Z. C., Sullivan, M., Webb, J., et al. (2021b). Action imagery and observation in neurorehabilitation for Parkinson's disease (ACTION-PD): development of a user-informed home training intervention to improve functional hand movements. Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2021/4559519

Bek, J., Leventhal, D., Groves, M., Growcott, C., and Poliakoff, E. (2022b). Moving online: experiences and potential benefits of digital dance for older adults and people with Parkinson's disease. PLoS ONE 17:e0277645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277645

Bennett, H. B., Walter, C. S., Oholendt, C. K., Coleman, K. S., and Vincenzo, J. L. (2023). Views of in-person and virtual group exercise before and during the pandemic in people with Parkinson disease. PM R 15, 772–779. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12848

Blasing, B., Calvo-Merino, B., Cross, E. S., Jola, C., Honisch, J., Stevens, C. J., et al. (2012). Neurocognitive control in dance perception and performance. Acta Psychol. 139, 300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.12.005

Caligiore, D., Mustile, M., Spalletta, G., and Baldassarre, G. (2017). Action observation and motor imagery for rehabilitation in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and an integrative hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 72, 210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.11.005

Camicioli, R., Morris, M. E., Pieruccini-Faria, F., Montero-Odasso, M., Son, S., Buzaglo, D., et al. (2023). Prevention of falls in Parkinson's disease: guidelines and gaps. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 10, 1459–1469. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13860

Carapellotti, A. M., Stevenson, R., and Doumas, M. (2020). The efficacy of dance for improving motor impairments, non-motor symptoms, and quality of life in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15:e0236820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236820

Christensen, J. F., Cela-Conde, C. J., and Gomila, A. (2017). Not all about sex: neural and biobehavioral functions of human dance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1400, 8–32. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13420

Chye, S., Valappil, A. C., Wright, D. J., Frank, C., Shearer, D. A., Tyler, C. J., et al. (2022). The effects of combined action observation and motor imagery on corticospinal excitability and movement outcomes: two meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 143:104911. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104911

de Dreu M. J. Kwakkel G. van Wegen E. E. H. Poppe E. and van der Wilk A. S. D. (2011). Rehabilitation, exercise therapy and music in patients with Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis of the effects of music-based movement therapy on walking ability, balance and quality of life. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 18, S114–S119. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70036-0

Delabary, M. S., Loch Sbeghen, I., Teixeira da Silva, E. C., Guzzo Júnior, C. C. E., and Nogueira Haas, A. (2024a). Brazilian dance self-perceived impacts on quality of life of people with Parkinson's. Front. Psychol. 15:1356553. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1356553

Delabary, M. S., Loch Sbeghen, I., Wolffenbuttel, M., Pereira, D. R., and Haas, A. N. (2024b). Online dance classes during the COVID-19 pandemic: new challenges and teaching strategies for the ‘Dance and Parkinson's at home' project. Res. Dance Educ. 25, 118–136. doi: 10.1080/14647893.2022.2083595

Dhami, P., Moreno, S., and DeSouza, J. F. X. (2015). New framework for rehabilitation: fusion of cognitive and physical rehabilitation: the hope for dancing. Front. Psychol. 5:1478. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01478

Dorsey, E. R., Sherer, T., Okun, M. S., and Bloem, B. R. (2018). The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J. Parkinsons Dis. 8, S3–S8. doi: 10.3233/JPD-181474

Ellis, T. D., and Earhart, G. M. (2021). Digital therapeutics in Parkinson's disease: practical applications and future potential. J. Parkinsons Dis. 11, S95–S101. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202407

Emmanouilidis, S., Hackney, M. E., Slade, S. C., Heng, H., Jazayeri, D., Morris, M. E., et al. (2021). Dance is an accessible physical activity for people with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2021:7516504. doi: 10.1155/2021/7516504

Fontanesi, C., and DeSouza, J. F. X. (2021). Beauty that moves: dance for Parkinson's effects on affect, self-efficacy, gait symmetry, and dual task performance. Front. Psychol., 11, 3896. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600440

Ghanai, K., Barnstaple, R. E., and DeSouza, J. F. X. (2021). Virtually in sync: a pilot study on affective dimensions of dancing with Parkinson's during COVID-19. Res. Dance Educ. 25, 17–31. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.17.20249000

Hadley, R., Eastwood-Gray, O., Kiddier, M., Rose, D., and Ponzo, S. (2020). “Dance like nobody's watching”: exploring the role of dance-based interventions in perceived well-being and bodily awareness in people with Parkinson's. Front. Psychol. 11:531567. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.531567

Hardwick, R. M., Caspers, S., Eickhoff, S. B., and Swinnen, S. P. (2018). Neural correlates of action: comparing meta-analyses of imagery, observation, and execution. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 94, 31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.08.003

Jola, C., Sundström, M., and McLeod, J. (2022). Benefits of dance for Parkinson's: the music, the moves, and the company. PLoS ONE 17:e0265921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265921

Karageorghis, C., Rose, D. C., Annett, L., Bek, J., Bottoms, L., Lovatt, P., et al. (2020). BASES expert statement on the use of music for movement among people with Parkinson's. Sport Exerc. Sci. 6–7.

Kelly, M. P., and Leventhal, D. (2021). Dance as lifeline: transforming means for engagement and connection in times of social isolation. Health Promot. Pract. 22, 64S−69S. doi: 10.1177/1524839921996332

McNeely, M. E., Duncan, R. P., and Earhart, G. M. (2015). Impacts of dance on non-motor symptoms, participation, and quality of life in Parkinson disease and healthy older adults. Maturitas 82, 336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.08.002

Mezzarobba, S., Bonassi, G., Avanzino, L., and Pelosin, E. (2024). Action observation and motor imagery as a treatment in patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 14, S53–S64. doi: 10.3233/JPD-230219

Morris, M. E., McConvey, V., Wittwer, J. E., Slade, S. C., Blackberry, I., Hackney, M. E., et al. (2023). Dancing for Parkinson's disease online: clinical trial process evaluation. Healthcare 11:604. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11040604

Morris, M. E., Slade, S. C., Wittwer, J. E., Blackberry, I., Haines, S., Hackney, M. E., et al. (2021). Online dance therapy for people with parkinson's disease: feasibility and impact on consumer engagement. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 35, 1076–1087. doi: 10.1177/15459683211046254

Nombela, C., Hughes, L. E., Owen, A. M., and Grahn, J. A. (2013). Into the groove: can rhythm influence Parkinson's disease? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 2564–2570. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.08.003

Pinto, C., Figueiredo, C., Mabilia, V., Cruz, T., Jeffrey, E. R., Pagnussat, A. S., et al. (2023). A safe and feasible online dance intervention for older adults with and without Parkinson's disease. J. Dance Med. Sci. 27, 253–267. doi: 10.1177/1089313X231186201

Poliakoff, E., Bek, J., Phillips, M., Young, W. R., and Rose, D. C. (2023). Vividness and use of imagery related to music and movement in people with Parkinson's: a mixed-methods survey study. Music Sci. 6:20592043231197919. doi: 10.1177/20592043231197919

Quinn, L., Busse, M., Khalil, H., Richardson, S., Rosser, A., Morris, H., et al. (2010). Client and therapist views on exercise programmes for early-mid stage Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease. Disabil. Rehabil. 32, 917–928. doi: 10.3109/09638280903362712

Rocha, P. A., Slade, S. C., McClelland, J., and Morris, M. E. (2017). Dance is more than therapy: qualitative analysis on therapeutic dancing classes for Parkinson's. Complement. Ther. Med. 34, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.07.006

Salimpoor, V. N., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K., Dagher, A., and Zatorre, R. J. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 257–262. doi: 10.1038/nn.2726

Senter, M., Clifford, A. M., O'Callaghan, M., McCormack, M., and Ni Bhriain, O. (2024). Experiences of people living with Parkinson's disease and key stakeholders in dance-based programs: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Disabil. Rehabil. 46, 6288–6301. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2024.2327499

Shanahan, J. (2015). Dance for people with Parkinson disease: what is the evidence telling us? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 96:1931. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.017

Shanahan, J., Morris, M. E., Bhriain, O. N., Volpe, D., Lynch, T., Clifford, A. M., et al. (2017). Dancing for Parkinson disease: a randomized trial of irish set dancing compared with usual care. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 98, 1744–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.017

Tamplin, J., Haines, S. J., Baker, F. A., Sousa, T. V., Thompson, Z., Crouch, H., et al. (2024). ParkinSong online: feasibility of telehealth delivery and remote data collection for a therapeutic group singing study in Parkinson's. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 38, 122–133. doi: 10.1177/15459683231219269

Tamplin, J., Morris, M. E., Marigliani, C., Baker, F. A., Noffs, G., Vogel, A. P., et al. (2020). ParkinSong: outcomes of a 12-month controlled trial of therapeutic singing groups in Parkinson's disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 10, 1217–1230. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191838

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, digital healthcare, neurorehabilitation, telemedicine, dance

Citation: Bek J, Jehu DA, Morris ME and Hackney ME (2025) Digital dance programs for Parkinson's disease: challenges and opportunities. Front. Psychol. 16:1496146. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1496146

Received: 13 September 2024; Accepted: 07 January 2025;

Published: 23 January 2025.

Edited by:

Selenia Di Fronso, University of eCampus, ItalyReviewed by:

Kristen Alexis Pickett, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Bek, Jehu, Morris and Hackney. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Judith Bek, SnVkaXRoLmJla0B1Y2QuaWU=

Judith Bek

Judith Bek Deborah A. Jehu

Deborah A. Jehu Meg E. Morris

Meg E. Morris Madeleine E. Hackney

Madeleine E. Hackney