94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 19 March 2025

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1477432

Objective: The capacity to interact with peers during early childhood can profoundly and enduringly influence later development and adaptation. Previous research has indicated that paternal involvement plays a vital role in shaping children’s peer competence. However, limited research has been conducted on this association within the Chinese cultural contexts or on the potential mechanisms that underlie it. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate whether there is a close link between paternal involvement and peer competence in Chinese young children, as well as whether children’s playfulness mediates this relationship.

Method: The Chinese version of the Paternal Involvement Questionnaire (FIQ) was distributed to 359 fathers with children (4–6 years old). Children’s Playfulness Scale (CPS) and Ability to Associate With Partners Scale (AAPS) were distributed to the children’s mothers.

Results: (1) There are positive correlations between paternal involvement, young children’s playfulness and peer competence after controlling for the demographic variables of age and gender. (2) Paternal involvement is positively related to young children’s peer competence. (3) Playfulness partially mediated the relationship between paternal involvement and children’s peer competence. Findings from this study emphasize the significance of paternal involvement in enhancing young children’s peer competence, while also highlighting the value of positive emotional traits such as playfulness for fostering family interaction and promoting young child development.

Early childhood is a critical period for children’s social development, during which peers play an irreplaceable role (Shaffer, 2005; Zhang, 1999). Interactions with peers offer a significant developmental context for children to acquire a diverse range of behaviors, skills, and attitudes that profoundly impact their adaptation throughout the lifespan. Previous studies consistently demonstrate that peer competence serves as a protective factor in facilitating children’s overall development (Parker et al., 2015). A high level of peer competence is characterized by reciprocal interactions, cooperative behaviors, intimate relationships, and collaborative problem-solving skills that are positively associated with children’s mental well-being and social adaptation (Eggum-Wilkens et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2020). Given the significant role of peer competence, it is critical to investigate its predictors and explore the underlying mechanisms.

With the development of family theory and positive developmental psychology, researchers have started recognizing the family processes that contribute to social competence, peer acceptance, and the ability to establish and maintain qualitatively enriching friendships (Ladd and Parke, 2021; Parker et al., 2015). Particularly noteworthy are paternal factors on family dynamics and child development (Cabrera, 2020; Flouri et al., 2016). China’s rapid socioeconomic transformation over the past two decades has precipitated significant shifts in family dynamics, with there being growing recognition of the crucial role paternal involvement plays in contemporary child-rearing practices (Li, 2020; Li and Lamb, 2016; Liu et al., 2021). Our study specifically focuses on examining the relationship between positive paternal involvement and children’s peer competence. As an extension, we further investigate the mediating role of children’s playfulness in this relationship within the Chinese context.

The family-peer system linkage theory posits that the family is the primary environment for children’s socialization, and that parenting behaviors and patterns have a significant impact on children’s social competence (Parke, 2004). Previous research has focused on the influence of mothers, while the influence of fathers has been understudied (Li, 2020; Zhang, 2013). Existing studies have consistently shown that paternal involvement during early childhood significantly contributes to offspring development in cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social adaptation domains (Choi and Song, 2014; Liu et al., 2021; Rollè et al., 2019; StGeorge and Freeman, 2017). Children residing with their fathers show better adaptive functions, fewer problem behaviors, and more harmonious interpersonal relationships (Lamb, 2010). Longitudinal studies have further revealed that early paternal participation can serve as a predictor of later peer problems among children (Craig et al., 2018; Flouri et al., 2016).

In addition, evidence suggests that maternal and paternal parenting may have distinct impacts on children’s social development. Neuroscience research indicates that maternal parenting can stimulate children’s affective regions, whereas paternal parenting can stimulate socio-cognitive regions (Abraham and Feldman, 2022; Kopala-Sibley et al., 2020). Developmental psychology research suggests that fathers and mothers influence children’s social development through different mechanisms, such as mother–child attachment relationships (Bowlby, 1969) and father-child activation relationships (Paquette, 2004). According to attachment theory, mothers usually provide a safe haven by calming and soothing children when they are distressed. In contrast, according to activation relationship theory, fathers typically engage in physical play with young children more frequently than mothers, and father-child physical play (e.g., rough and tumble play) provides a secure base for children to safely explore the outside world, learn to cope with unfamiliar situations and challenges, and develop social emotional skills (Amodia-Bidakowska et al., 2020; Paquette et al., 2021; Paquette and StGeorge, 2023).

While these findings imply the unique value of paternal parenting in child development and a robust association between paternal involvement and young children’s peer competence, there remains a dearth of research investigating the underlying mechanisms. In this study, we aim to explore the mediating role of playfulness in the relationship between paternal involvement and children’s peer competence within a Chinese cultural context, thereby elucidating one such mechanism.

Play is an innate inclination towards curiosity, imagination, and fantasy, and child-directed play is inherently developmentally appropriate and can be harnessed to facilitate academic and social learning (Wong et al., 2008). Some scholars have recognized the crucial role of play in young children’s cognitive, emotional, and social development (Barnett, 1990; Lieberman, 1977). Prior studies primarily focused on the external manifestation of play and its associations with language and cognition (Reddy, 1991). However, advancements in play theory and positive developmental psychology have prompted researchers to consider playfulness as an active tendency or a personality trait, and study it from clinical (Bögels and Phares, 2008), developmental (Hwang, 2006), and neuroscientific perspectives (Youell, 2008). In this sense, playfulness is defined as an active tendency to be engaged in play or a personality trait that is stable and spontaneously appears in play (Wu et al., 2019), composed of elements such as spontaneity, active engagement, and sense of humor.

Previous research has found that fathers’ direct interaction (e.g., playing with children and reading to children) and indirect participation (e.g., developmental support, planning for the future) are both associated with the development of children’s playfulness (Lee and Kim, 2013). In turn, children’s playfulness can influence their peer competence (Hwang, 2006; Cho and Sung, 2020; Fung and Chung, 2023; Han and Yang, 2023). Additionally, according to the father-child relationship-activation theory (Paquette, 2004) and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2019), playfulness may serve as a valuable mediating variable between paternal involvement and children’s peer competence.

The paternal role has historically been deeply rooted in Confucian cultural traditions in China, serving as a cornerstone of familial and societal order (Santos and Harrell, 2016). Traditional Chinese fatherhood emphasizes symbolic authority and emotional restraint, with fathers primarily fulfilling disciplinary and educational responsibilities (Li, 2020), while maintaining minimal involvement in daily childcare and play activities (Li and Lamb, 2016). In recent decades, however, sociocultural shifts driven by three interconnected factors have led to a rethinking of paternal responsibilities. First, theoretical advancement in positive development theory and father-child activation relationship theory, have highlighted the crucial role of paternal engagement in child development. Second, demographic policy shifts exemplified by the Three-Child Policy have intensified societal expectations for co-parenting (He and Zuo, 2023). Third, the proliferation of dual-earner households has rendered maternal monopoly over childcare both practically unsustainable and socially undesirable (Hong and Zhu, 2022). Recent empirical evidence indicates a notable shift in paternal behavior, with contemporary Chinese fathers exhibiting greater involvement in childcare and heightened emotional expressiveness relative to earlier generations (Liu et al., 2021). Nevertheless, structural barriers persist: quantitative analyses reveal persistent disparities in caregiving time allocation, while qualitative studies highlight enduring cultural resistance to redefining paternal roles beyond economic provision and discipline (Li, 2020; Wu et al., 2012). Nowadays, most countries in the world are overemphasizing academic work at the cost of providing time and space to play (Sahlberg and Doyle, 2019). Chinese traditional culture in particular, attaches great importance to children’s learning, while play is often equated with ‘wasting time’ (不务正业). Nevertheless, contemporary researchers and educators are increasingly acknowledging the developmental significance of play and playfulness in childhood. Notably, there are variations in defining playfulness based on geographical context within Chinese culture and Western culture. Western culture emphasis lies more on external characteristics such as self-expression and non-inhibition (Barnett, 2007), while Chinese culture focuses more on internal characteristics like deep engagement, self- persistence, and relaxation (Yu et al., 2003). Therefore, whether paternal involvement and children’s playfulness have different characteristics and how the variables effect young children’s peer competence within Chinese cultural background, needs to be further studied.

We aim to examine in the Chinese context: (1) The direct relationship between paternal involvement and young children’s peer competence. (2) The role of playfulness in the relationship. (3) Whether children’s playfulness can mediate the effect of paternal involvement on young children’s peer competence. We hypothesize that paternal involvement would be positively associated with young children’s peer competence and playfulness, and that young children’s playfulness would partially mediate the relationship between paternal involvement and young children’s peer competence.

This study adopted the cluster random sampling method. Before distributing questionnaires, we randomly selected four kindergartens from four district in Yantai, Shandong Province, China. After obtaining the approval of kindergarten principals, during the family-kindergarten cooperation day, we first explain to the parents about the purposes and procedures of our study. Then, we guided fathers to report the paternal involvement questionnaire, and mothers to report the children’s playfulness and peer competence questionnaires. This study received approval from the Ethic Committee of the college of Education of Shandong Women’s University. And all participants read and signed the informed consent form. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed and 41 were excluded, of which 29 fathers and 12 mothers did not fill out the questionnaire. The final analysis included 359 valid questionnaires, accounting for 89.75% of the total. The age of children ranged from 4 to 6 years old (M = 4.98, SD = 0.77), including 164 boys (45.7%) and 195 girls (54.3%), and 108 4 years old children (42.6%, 46 boys), 149 5 years old children (45.6%, 68 boys), 102 6 years old children (49.0%, 50 boys). Regarding education level, fathers were either high school graduates (26.5%) or had university/college degrees (62.4%). Households with a monthly income of more than 9,000 RMB accounted for 53.2%. The sample mainly consisted of participants from the middle class.

Paternal involvement was assessed using the Chinese version of 26-item Father Involvement Questionnaire (FIQ) (Chen, 2021). The scale’s reliability and validity were rigorously examined, comprising three dimensions: Engagement (9 items, e.g., “accompanying child to a museum, zoo, science center, or library”), Accessibility (5 items, e.g., “when we are not together, my child can connect with me if he/she wants to”), and Responsibility (12 items, e.g., “providing financial support for child’s development”). Participants rated their responses on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), and item scores are averaged. Higher scores indicate greater paternal involvement. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale in the present study was 0.964.

Children’s playfulness was assessed by the 23-item Children’s Playfulness Scale (CPS) (Barnett, 1990), which has been widely used in accessing playfulness of young children (e.g., Han and Yang, 2023; Fung and Chung, 2022). The scale consisted of five dimensions: Physical spontaneity (4 items, e.g., “the child is physically active during play”), Social Spontaneity (5 items, e.g., “the child initiates play with others”), Cognitive spontaneity (4 items, e.g., “the child uses unconventional objects in play”), manifest joy (5 items, e.g., “the child expresses enjoyment during play”), and sense of humor (4 items, e.g., “the child enjoys joking with other children”). CPS has been extensively utilized in Chinese research, and its reliability has been widely established. Participants rated their responses on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), and item scores were averaged. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale in the present study was 0.868.

Peer competence was assessed using the Chinese version of 24-item children’s Ability to Associate with Partners Scale (AAPS) (Zhang, 2002), which has been widely used in China and its reliability and validity have been repeatedly confirmed. The scale consisted of four dimensions: Social Initiative (6 items, e.g., “the child actively introduce oneself to the new partner”), verbal and nonverbal ability to associate (6 items, e.g., “the child can use smiling, waving, nodding, and other gestures”), Social Dysfunction (6 items, e.g., “the child frequently experiences peer rejection”), and prosocial behavior (6 items, e.g., “the child demonstrates willingness to help other children”). Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with item scores averaged for analysis purposes. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale in the present study was 0.851.

The children’s age and gender were assessed based on demographic information, and these variables were considered as covariates to ensure their effects were controlled.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 and Mplus 8.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017) in the present study. The data analysis comprised four steps.

Firstly, all variables were confirmed to meet normality assumptions, and Pearson correlation analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0. Secondly, confirmatory factor analysis of the scale was performed using Mplus 8.0, with x2/df < 3, TLI > 0.90, CFI > 0.90, and RMSEA <0.08 indicating a good fit (Little and Card, 2013). Thirdly, Latent variable structural equation modeling via Mplus 8.0 was employed to assess the mediating role of playfulness between paternal involvement and young children’s peer competence. Finally, the bootstrap method was utilized to obtain confidence intervals for testing both direct and indirect effects.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and results of Pearson’s correlation analysis for each variable. The results showed that paternal involvement (M = 3.83, SD = 0.83), children’s playfulness (M = 4.02, SD = 0.52) and peer competence (M = 4.06, SD = 0.52), all exceeded the theoretical average level of 3.00, which represents the expected mean in the general population. Paternal involvement was positively correlated with playfulness (r = 0.45, p < 0.01) and young children’s peer competence (r = 0.31, p < 0.01). Children’s playfulness was positively correlated with their peer competence (r = 0.71, p < 0.01).

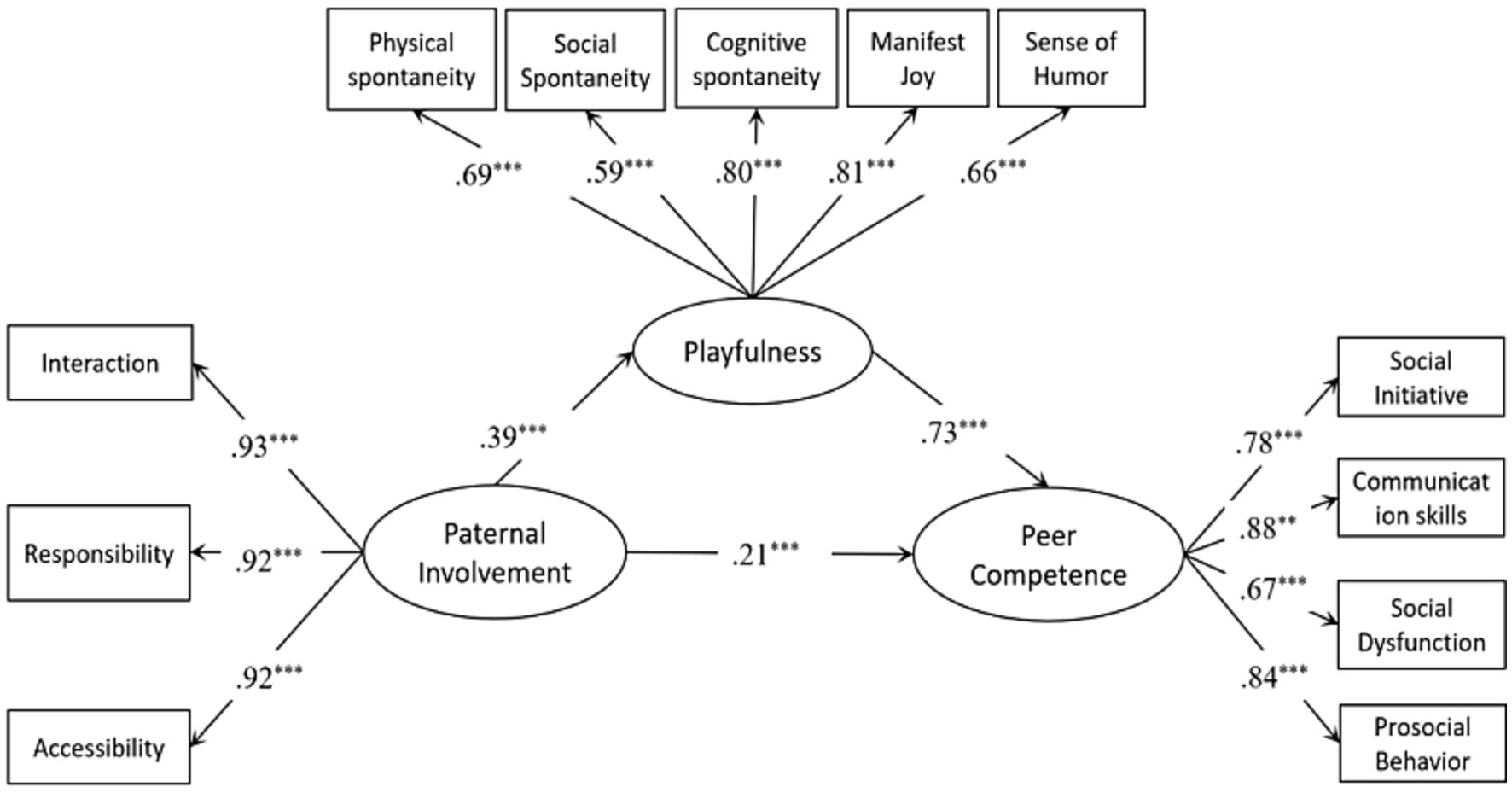

The total effect model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (x2/df = 1.11, CFI = 1; TLI = 1; RMSEA = 0.034). As shown in Table 2, paternal involvement exhibited a significant total effect on children’s peer competence (β = 0.50, 95% CI: [0.39, 0.59]). Subsequently, we tested the mediation model, the mediation model displayed an acceptable fit to the data (x2/df = 3.18, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.066; SRMR = 0.058), and all the standardized path coefficients were presented in Figure 1. Specifically, although the direct effect attenuated yet still statistically significant (β = 0.21, 95% CI: [0.12, 0.32]), the positive predictive impact of paternal involvement on peer competence persisted in our findings and was partially mediated by children’s playfulness (β = 0.29, 95% CI: [0.20, 0.39]). Notably, approximately 58% of the total effect was accounted for by the mediation effect of children’s playfulness (as shown in Table 2).

Figure 1. Mediating model of playfulness between father involvement and young children’s peer competence. RMSEA = 0.066, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93 (N = 359). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed).

The present study addressed an important issue: namely whether paternal involvement promotes young children’s peer competence in contemporary Chinese cultural contexts and what are the underlying mechanisms. We constructed a mediation model to investigate the impact of paternal involvement on young children’s peer competence and examine the mediating roles of children’s playfulness. The findings of our study hold theoretical implications and practical significance for facilitating paternal involvement, enhancing young children’s playfulness, and promoting their peer competence.

As expected, the relationship between paternal involvement and children’s peer competence is positive and significant. Which means, children whose fathers are positively involved in their lives tend to have better peer interaction skills. This finding aligns with previous studies (Amodia-Bidakowska et al., 2020; Craig et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021; StGeorge and Freeman, 2017) and provides empirical support for attachment theory, parental capital theory, and father-child activation relationship theory. According to attachment theory, positive paternal involvement (e.g., warmth, sensitivity, supportiveness) can foster strong emotional bonds between fathers and children (Brown et al., 2018; Cabrera, 2020; Newland et al., 2008). These bonds enable children to access essential psychological resources, such as resilience and self-efficacy (Ladd and Parke, 2021), and help them develop positive internal working models, which can enhance their interpersonal trust and sense of security (Caina et al., 2016; Groh et al., 2014). This, in turn, may help them approach others with positive attitudes and expectations, ultimately improving their socialization skills. Parental capital theory also suggests that fathers can create opportunities for their children to engage with peers and offer advice on peer selection and appropriate play strategies, which is crucial in fostering early childhood social competence (Li et al., 2020).

The father-child activation relationship theory posits that direct interaction between fathers and children (e.g., rough and tumble play), often leads to heightened arousal levels. This can have a stimulating effect on children’s physical, emotional, and cognitive development while promoting self-control and empathy towards others (Paquette, 2004). A defining feature of father-child play involves numerous vigorous and playful physical interactions, which foster positive emotional experiences, including enjoyment, pleasure, and playfulness, for both fathers and children (Flanders et al., 2013). These shared experiences critically contribute to establishing and sustaining father-child emotional bonds (Paquette et al., 2021). The significance of emotional bonds in facilitating children’s social adaptation and interpersonal interactions has been corroborated by attachment theory and family-peer system linkage theory. In addition, research shows that high-quality father-child physical play incorporates unique parenting behaviors such as warmth, reciprocity, assertive control, sensitivity, touch, and playfulness (StGeorge and Freeman, 2017). This can creates a structured and meaningful environment that fosters confidence, cognitive and emotional control in children, as well as the ability to exercise restraint in competitive or conflictual situations (Paquette and StGeorge, 2023; Smith and StGeorge, 2023). Notably, children demonstrating advanced emotional regulation strategies and cognitive control mechanisms exhibit two critical developmental advantages: reduced externalizing problem and enhanced Social- emotional functioning (Lindsey and Berks, 2019; StGeorge et al., 2021; Wang and Feng, 2024). These made children more popular among peer groups and likely to emerge as leaders within them (Paquette, 2015).

The present study also revealed a significant mediating role of playfulness in the relationship between paternal involvement and children’s peer competence. Specifically, in the first path of the mediator model, paternal involvement was significantly correlated with children’s playfulness. This finding aligns with previous studies (Lee and Kim, 2013) and provides empirical support for dynamic system theory and positive developmental theory. Lee and Kim (2013) revealed that paternal involvement (e.g., developmental support, child care and guidance) significantly accounted for the variance in the playfulness of young children. Some studies have reported that paternal support and positive responsiveness during early childhood are predictors of children’s cognitive and socio-emotional skills (Cabrera et al., 2007). Moreover, cognitive and emotional skills have been proven to influence children’s playfulness (Jo et al., 2016). According to dynamic system theory and positive developmental theory, development occurs in an open system of self-organization, characterized by a continuous exchange of information with the environment. Furthermore, most developmental phenomena are influenced by multiple factors and exhibit temporal changes (Fischer and Bidell, 2006). Playfulness occurs during early experiences of playful interaction with parents (Reddy, 1991; Youell, 2008), through which children develop a cognitive perception of the world as a playground and perceive the external environment as friendly and secure (Paquette, 2004). Consequently, they display increased engagement, exploratory behavior, and positive emotion during play activities with peers. This playful state recurs in parent–child and child–child interactions, gradually internalizing into individuals’ behavior patterns.

In the second path of the mediator model, children’s playfulness showed a significant association with their peer competence. Playful children typically exhibit high levels of cognitive, social and physical spontaneity (Lieberman, 1965; Singer and Rurnmo, 1973). This enables them to better plan and execute play actions, generate attractive play ideas, and effectively engage play partners (Fung and Chung, 2022). Additionally, they are proficient in using conflict resolution strategies such as compromise, cooperation, avoidance, and concession when interacting with peers (Hwang, 2006; StGeorge and Freeman, 2017). Moreover, children with playfulness have greater cognitive flexibility and are more resourceful in establishing positive peer play interactions. They can more naturally enter into peer play, negotiate roles and directions, and resolve conflicts constructively (Fung and Cheng, 2017; Fung and Chung, 2023). These playful qualities make children more popular with their peers. Conversely, children lacking in playfulness often exhibit social withdrawal, which hinders the display of prosocial behavior and increases the likelihood of peer rejection or exclusion (Han and Yang, 2023; Kim and Kim, 2019; Rubin et al., 2018).

Furthermore, in line with Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, playfulness is regarded as a psychological or emotional state in which children actively engage in play and derive pleasure. It plays a pivotal role in the expansion and constructive effect on children’s social development. On one hand, playfulness has a protective expansion effect against individual negative characteristics, such as shyness and social indifference, shielding children from peer play rejection or isolation (Han and Yang, 2023). On the other hand, it has a construction function of expanding positive individual characteristics, such as joy, interest, and a sense of humor and fulfillment (Wu et al., 2019). Children with positive emotions are more likely to evoke positive emotional expressions and adaptive coping strategies (Cho and Sung, 2020; Wang and Feng, 2024).

The findings suggest that positive and affectionate father-child interactions are crucial for the development of children’s peer competence. The study emphasizes the importance of child-centered and play-based activities in the home environment to foster children’s playfulness and social development.

There are some contributions to this study: (1) In this study, we expanded upon previous investigations into the mechanisms underlying the impact of paternal involvement on young children’s peer competence in light of the dynamic system theory, social cognitive theory, father-child relationship-activation theory and broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The findings revealed a positive correlation between higher levels of paternal involvement and enhanced peer competence among young children in contemporary Chinese society. Furthermore, our results demonstrated that children’s playfulness played a significant partial mediating role in the association between paternal involvement and young children’s peer competence, highlighting the crucial importance of positive personality traits for family interactions and child development. (2) From a practical perspective, our study underscores the significance of child-centered and play-based activities within the home environment for promoting children’s peer competence. Additionally, we emphasizes the value of fathers’ positive life guidance and affectionate behavior during interactions with their children during playtime. Our study offers targeted guidance and theoretical support for facilitating positive paternal involvement that effectively enhances children’s playfulness and peer competence. Consequently, governmental implementation of fertility support policies is warranted to ensure sufficient father-child bonding time while communities and kindergartens should enhance fathers’ awareness regarding parenting roles through family education lectures or guidance sessions to ensure high-quality paternal involvement. (3) Father and mother exhibit overlapping roles yet demonstrate distinct contributions in the socio-emotional development of children. Specifically, the emotional scaffolding provided by mothers and the social problem-solving modeling exhibited by fathers constitute complementary yet independent developmental mechanisms. Consequently, family systems should strategically encourage active paternal involvement in caregiving practices, thereby establishing a co-parenting framework that optimizes developmental outcomes through the integration of dual parental resources.

Future researches should address some limitations to this study: (1) Utilized a small sample size selected from four public kindergartens in one specific city in eastern China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider examining paternal involvement across various significant regional and ethnic differences observed in different provinces throughout China, as well as sampling from both urban and rural settings and different types of kindergartens. (2) While our study exclusively employed a questionnaire-based methodology, Subsequent investigations should consider adopting multi-method approaches such as direct observational measures of paternal-child interactions, peer play dynamics, and tests of social competence. Such methodological triangulation would enable more rigorous evaluation of whether parent-reported correlations authentically reflect children’s behavioral manifestations. (3) The present study solely focused on exploring the role of paternal factor on young children’s peer competence, however, development is influenced by multiple systems. Therefore, future research should investigate how family dynamics, school environments, and individual variables systematically influence young children’s peer competence.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the college of education of Shandong Women’s University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the General topic in Pedagogy of the National Social Science Foundation of China (BHA230154) and the Scientific Research Fund for High-Level Talents of Shandong Women’s University (2020RCYJ08).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abraham, E., and Feldman, R. (2022). The neural basis of human fatherhood: a unique biocultural perspective on plasticity of brain and behavior. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 25, 93–109. doi: 10.1007/s10567-022-00381-9

Amodia-Bidakowska, A., Laverty, C., and Ramchandani, P. G. (2020). Father-child play: a systematic review of its frequency, characteristics and potential impact on children’s development. Dev. Rev. 57:100924. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2020.100924

Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of playfulness in young adults. J. Pers. Individ. Differ. 43, 949–958. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.018

Bögels, S., and Phares, V. (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: a review and new model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 539–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011

Brown, G. L., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Shigeto, A., and Wong, M. S. (2018). Associations between father involvement and father-child attachment security: variations based on timing and type of involvement. J. Fam. Psychol. 32, 1015–1024. doi: 10.1037/fam0000472

Cabrera, N. J. (2020). Father involvement, father-child relationship, and attachment in the early years. Attach Hum. Dev. 22, 134–138. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2019.1589070

Cabrera, N. J., Shannon, J. D., and Tamis-Lemonda, C. (2007). Fathers’ influence on their children’s cognitive and emotional development: from toddlers to pre-k. J. Appl. Dev. Sci. 11, 208–213. doi: 10.1080/10888690701762100

Caina, L. I., Ying, S., Rui, T., and Jia, L.School of Psychology (2016). The effects of attachment security on interpersonal trust: the moderating role of attachment anxiety. Acta Psychol. Sin. 48:989. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.00989

Chen, Y. (2021). The influence of father involvement on children’s competence with peers-the mediating role of mothers’ parenting efficacy. J. Cent Chin. Norm. Univ. doi: 10.27159/d.cnki.ghzsu.2021.002480

Cho, D., and Sung, J. (2020). The mediating effect of children’s playfulness on the relationship between their executive function and peer competence. Korean. J. Child Stud. 41, 61–73. doi: 10.5723/kjcs.2020.41.4.61

Choi, M., and Song, S. (2014). The effects of the young children’s self-regulation and peer competence according to father’s involvement in child-rearing. J. Child. Literature. Educ. 15, 313–332.

Craig, A. G., Thompson, J. M. D., Slykerman, R., Wall, C., Murphy, R., Mitchell, E. A., et al. (2018). The long-term effects of early paternal presence on children’s behavior. J. Child Fam. Stud. 27, 3544–3553. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1206-1

Eggum-Wilkens, N. D., Fabes, R. A., Castle, S., Zhang, L. L., Hanish, L. D., and Martin, C. L. (2014). Playing with others: head start children’s peer play and relations with kindergarten school competence. Early Child Res. Q. 29, 345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.04.008

Fischer, K. W., and Bidell, T. (2006). Dynamic development of action and thought : John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Flanders, J. L., Herman, K. N., and Paquette, D. (2013). “Rough-and-tumble play and the cooperation-competition dilemma: evolutionary and developmental perspectives on the development of social competence” in Evolution, early experience and human development: From research to practice and policy. eds. D. Narvaez, J. Panksepp, A. N. Schore, and T. R. Gleason (Oxford University Press), 371–387.

Flouri, E., Midouhas, E., and Narayanan, M. K. (2016). The relationship between father involvement and child problem behaviour in intact families: a 7-year cross-lagged study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 44, 1011–1021. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0077-9

Fredrickson, B. L. (2019). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 359, 1367–1378. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Fung, W. K., and Cheng, W. Y. (2017). Effect of school pretend play on preschoolers’ social competence in peer interactions: gender as a potential moderator. Early Child Educ. J. 45, 35–42. doi: 10.1007/s10643-015-0760-z

Fung, W. K., and Chung, K. (2022). Parental play supportiveness and kindergartners’ peer problems: Children’s playfulness as a potential mediator. Soc. Dev. 31, 1126–1137. doi: 10.1111/sode.12603

Fung, W. K., and Chung, K. (2023). Playfulness as the antecedent of kindergarten children’s prosocial skills and school readiness. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 31, 797–810. doi: 10.1080/1350293x.2023.2200018

Groh, A. M., Fearon, R. P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Steele, R. D., and Roisman, G. (2014). The significance of attachment security for children’s social competence with peers: a meta-analytic study. Attach Hum. Dev. 16, 103–136. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2014.883636

Han, Y., and Yang, X. (2023). Effects of shyness and social indifference on peer play behavior of preschool children aged 3-6: mediating and moderating role of playfulness. Stud. Early Child. Educ., 36–50. doi: 10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2023.09.003

He, J., and Zuo, Z. (2023). The status quo of childcare, willingness to re-bear children and nursery needs of double-income households. J. Chengdu Norm. Univ. 39, 23–33. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5642.2023.03.004

Hong, X., and Zhu, W. (2022). Family’s willingness to have three children and its relationship with infant and toddler care support. J. Soc. Sci. Guangzhou Univ. 21, 136–148.

Hwang, Y.-S. (2006). A study on the relationship of children’s playfulness to their children’s peer competence and teacher-child relationship. J. Korean. Open Assoc. Early Child. Educ. 11, 211–228.

Jo, J., Kim, Y., and Na, J. (2016). Exploration of influential self-related variables (self-regulation, self-efficacy, self-esteem) for the playfulness of preschoolers. J. Child Edu. 25, 261–276. doi: 10.17643/KJCE.2016.25.1.15

Kim, Y. L., and Kim, S. (2019). Classification of aggression and social withdrawal in early childhood and its associations with peer competence: using latent profile analysis. Korean. J. Child Stud. 40, 151–163. doi: 10.5723/kjcs.2019.40.4.151

Kopala-Sibley, D. C., Cyr, M., Finsaas, M. C., Orawe, J., Huang, A., Tottenham, N., et al. (2020). Early childhood parenting predicts late childhood brain functional connectivity during emotion perception and reward processing. Child Dev. 91, 110–128. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13126

Ladd, G. W., and Parke, R. D. (2021). Themes and theories revisited: perspectives on processes in family-peer relationships. Children 8:507. doi: 10.3390/children8060507

Lamb, M. E. (2010). The role of the father in child development, 5th edition. China Fiber Inspect. 4, 43–55. doi: 10.2514/6.2004-1376

Lee, B., and Kim, K. S. (2013). Relationships between father’s child-rearing involvement and young children’s playfulness/self-control ability. Korean. J. Child Educ. 22, 191–206.

Li, X. (2020). Fathers’ involvement in Chinese societies: increasing presence, uneven progress. Child Dev. Pers. 14, 150–156. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12375

Li, X., and Lamb, M. E. (2016). Fathers in Chinese culture: traditions and transitions. Roopnarine, J. L. (Ed.), Fathers across cultures: The importance, roles, and diverse practices of dads. Santa Barbara, CA, US: Greenwood 273–306.

Li, X., Zhou, S., and Guo, Y. (2020). Bidirectional longitudinal relations between parent-grandparent co-parenting relationships and Chinese children’s effortful control during early childhood. Front. Psychol. 11:152. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00152

Lieberman, J. N. (1965). Playfulness and divergent thinking: an investigation of their relationship at the kindergarten level. J. Genet. Psychol. 107, 219–224. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1965.10533661

Lieberman, A. F. (1977). Preschoolers’ competence with a peer: relations with attachment and peer experience. Child Dev. 48, 1277–1287. doi: 10.2307/1128485

Lindsey, E. W., and Berks, P. S. (2019). Emotions expressed with friends and acquaintances and preschool children’s social competence with peers. Early Child. Res. Q. 47, 373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.01.005

Little, T. D., and Card, N. A. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Liu, Y., Dittman, C. K., Guo, M., Morawska, A., and Haslam, D. (2021). Influence of father involvement, fathering practices and father-child relationships on children in mainland China. J. Child Fam. Stud. 30, 1858–1870. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01986-4

Newland, L. A., Coyl, D. D., and Freeman, H. (2008). Predicting preschoolers’ attachment security from fathers’ involvement, internal working models, and use of social support. Early Child Dev. Care 178, 785–801. doi: 10.1080/03004430802352186

Paquette, D. (2004). Theorizing the father-child relationship: mechanisms and developmental outcomes. J. Human Dev. 47, 193–219. doi: 10.1159/000078723

Paquette, D. (2015). “An evolutionary perspective on antisocial behavior: evolution as a foundation for criminological theories” in The development of criminal and antisocial behavior: Theory, research and practical applications. eds. J. Morizot and L. Kazemian (New York, NY: Springer).

Paquette, D., Cyr, C., Gaumon, S., St-André, M., Émond-Nakamura, M., Boisjoly, L., et al. (2021). The activation relationship to father and the attachment relationship to mother in children with externalizing behaviors and receiving psychiatric care. Psychiatry Int. 2, 59–70. doi: 10.3390/psychiatryint2010005

Paquette, D., and StGeorge, J. M. (2023). Proximate and ultimate mechanisms of human father-child rough-and-tumble play. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 149:105151. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105151

Parke, R. D. (2004). Development in the family. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 365–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141528

Parker, J., Rubin, K. H., Price, J., and Desrosiers, M. (2015). Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: a developmental psychopathology perspective. J. Dev. Psycho., 419–493. doi: 10.1002/978047.0939383.ch12

Reddy, V. (1991). Playing with others’ expectations: Teasing and mucking about in the first year. Natural theories of mind: Evolution, development and simulation of everyday mindreading.

Rollè, L., Gullotta, G., Trombetta, T., Curti, L., and Caldarera, A. M. (2019). Father involvement and cognitive development in early and middle childhood: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 10:2405. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02405

Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., and Bowker, J. C. (2018). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60:141. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-16999-62447-1

Sahlberg, P., and Doyle, W. (2019). Let the children play: Why more play will save our schools and help children thrive : Oxford University Press.

Santos, G. D., and Harrell, S. E. (2016). Transforming patriarchy: Chinese families in the twenty-first century. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Shaffer, D. R. (2005). Social and personality development. 5th Edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Singer, D. G., and Rurnmo, J. I. (1973). Creativity and behavioral style in kindergarten - aged children. Dev. Psychol. 8, 154–161. doi: 10.1037/h0034155

Smith, P. K., and Stgeorge, J. M. (2023). Play fighting (rough-and-tumble play) in children: developmental and evolutionary perspectives. Int. J. Play. 12, 113–126. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2022.2152185

StGeorge, J., Campbell, L. E., Hadlow, T., and Freeman, E. E. (2021). Quality and quantity: a study of father-toddler rough-and-tumble play. J. Child Family Stud. 30, 1275–1289. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01927-1

StGeorge, J., and Freeman, E. (2017). Measurement of father-child rough-and-tumble play and its relations to child behavior. Infant Ment. Health J. 38, 709–725. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21676

Wang, X., and Feng, T. (2024). Does executive function affect children’s peer relationships more than emotion understanding? A longitudinal study based on latent growth model. Early Child Res. Q. 66, 211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2023.10.010

Wang, Y. J., Zhang, M. X., and Li, Y. (2020). The relationship between early peer acceptance and social adaptation in children: a cross-lagged analysis. J. Psy. Sci 43, 622–628. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200316

Wong, W., Ma, W. L., Strober, D. E., and Golinkoff, R. (2008). The power of play: how spontaneous, imaginative activities lead to happier, healthier children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 47, 1099–1100. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000313985.49029.a3

Wu, X., Guo, S., Liu, C., Chen, L., and Guo, Y. (2012). The emphasis of fatherhood in social change: analysis based on bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. J. Soc. Sci. South Chin. Norm. Univ. 2012:158.

Wu, A., Xu, S. S., and Li, D. (2019). Playfulness: a psychological character that promotes children’s positive development. Stud. Early Child. Educ. 6, 25–34. doi: 10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2019.06.003

Youell, B. (2008). The importance of play and playfulness. Eur. J. Psychother. Counsel. 10, 121–129. doi: 10.1080/13642530802076193

Yu, P., Wu, J., Lin, W., and Yang, C. (2003). The development of adult playfulness scale and organizational playfulness climate questionnaire. J. Psychol. Test. 50, 73–110. doi: 10.7108/PT.200306.0073

Zhang, Y. (2002). The table of peer competence among children aged 4-6. J. Soc. Sci. Jiangsu Educ., 42–44.

Zhang, X. (2013). Bidirectional longitudinal relations between father-child relationships and Chinese children’s social competence during early childhood. Early Child Res. Q. 28, 83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.06.005

Keywords: paternal involvement, young children, playfulness, peer competence, Chinese context

Citation: Liang C and Bi X (2025) Paternal involvement and peer competence in young children: the mediating role of playfulness. Front. Psychol. 16:1477432. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1477432

Received: 07 August 2024; Accepted: 04 March 2025;

Published: 19 March 2025.

Edited by:

Marijke Achterberg, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Sergio Marcello Pellis, University of Lethbridge, CanadaCopyright © 2025 Liang and Bi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunyan Liang, MjgwODZAc2R3dS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.