- 1Shandong Xiehe University, Jinan, China

- 2Thamar University, Dhamar, Yemen

- 3Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

Introduction: Mindfulness has been widely recognized for its positive impact on various aspects of psychological well-being. Prior research has investigated the role of mindfulness in enhancing hope and life satisfaction as separate constructs. However, limited attention has been given to the simultaneous influence of mindfulness on both hope and life satisfaction and the underlying mechanisms that may explain these relationships. This study examines the role of dispositional mindfulness in fostering hope and life satisfaction concurrently and explores the potential mediating role of meaning in life in this relationship.

Methods: A total of 1,766 Chinese college students from Shandong Xiehe University participated in the study. Participants completed the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) to assess dispositional mindfulness, the Adult Hope Scale (AHS) to measure hope, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) to evaluate life satisfaction, and the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) to assess their perceived meaning in life. Statistical analyses, including mediation analysis, were conducted to explore the relationships among these variables.

Results: The findings indicated that meaning in life partially mediated the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and both hope and life satisfaction. Specifically, higher levels of dispositional mindfulness were associated with greater hope and life satisfaction, and this relationship was partially explained by increased perceptions of meaning in life.

Discussion: These results underscore the critical role of meaning in life as a mediator in the positive effects of mindfulness on psychological well-being. The findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing mindfulness may benefit from incorporating strategies to foster meaning in life, thereby amplifying their impact on hope and life satisfaction. This study advances our understanding of the mechanisms linking mindfulness to key indicators of psychological well-being and highlights the integrative role of meaning in life in these processes.

Introduction

Mindfulness plays a crucial role in cultivating positive psychological traits that enhance mental well-being. By promoting a balanced approach to life, mindfulness not only influences individuals positively but also has a beneficial impact on those around them. Individuals who practice mindfulness are better equipped to withstand adversity and exercise greater control over their emotions, contributing to overall psychological health. Mindfulness encompasses a variety of strategies designed to improve psychological well-being, life satisfaction, bodily awareness, empathy, and mental clarity (Dobkin and Hassed, 2016). It is often described as a state of consciousness characterized by refined attentional abilities and a nonjudgmental awareness of both internal and external experiences. Research has consistently shown that higher levels of mindfulness are associated with a range of positive outcomes, including enhanced hope and life satisfaction. Programs that integrate mindfulness with hope-based interventions have been developed to foster mindful awareness and encourage these positive psychological attributes (Abdolghaderi et al., 2018; Malinowski and Lim, 2015; Thornton et al., 2014).

Many studies have examined the relationship between mindfulness and various psychological attributes contributing to hope and life satisfaction. However, a more critical and in-depth analysis of these studies is warranted. Research has repeatedly shown that mindfulness is positively linked with several emotional and psychological outcomes, such as increased positive emotions (Du et al., 2019; Garland et al., 2015; Lindsay et al., 2018), emotional regulation (Hill and Updegraff, 2012; Koç and Uzun, 2024; Prakash et al., 2015; Tomlinson et al., 2018), and emotional intelligence (Agastya, 2023; Miao et al., 2018; Pantelides, 2024; Wang, 2023). These findings suggest that mindfulness enhances emotional stability and psychological well-being, both of which are crucial for fostering hope and life satisfaction. However, while the evidence suggests a positive relationship, the specific mechanisms through which mindfulness influences these outcomes remain underexplored. Further research is needed to clarify these underlying processes.

Moreover, mindfulness appears to support individuals in navigating challenging life circumstances by fostering present-moment awareness and self-compassion. These qualities may prevent individuals from experiencing extreme emotional states, thereby contributing to greater psychological well-being. Although the evidence suggests that mindfulness helps individuals cope with stress and emotional difficulties, its impact on life satisfaction and hope may vary depending on individual and contextual factors.

The concept of mindfulness itself deserves further consideration, particularly regarding its role in fostering a goal-oriented mindset. Mindfulness, coupled with a sense of meaning in life, may encourage individuals to take purposeful steps toward a more fulfilling future (Singh and Devender, 2015; Snyder, 2010). However, it is important to critically assess whether mindfulness alone can instill a sense of meaning in life or whether other factors, such as cultural context and personal values, also play significant roles. Existing literature suggests that hope and life satisfaction are influenced by multiple factors, including quality of life (Montgomery et al., 2016; Pais-Ribeiro and Pedro, 2022; Wang et al., 2024), psychological well-being (Siah, 2024; Warsah et al., 2023), and happiness (El Shobaky et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2018; Kardas et al., 2019; Sevari et al., 2020). These findings imply that mindfulness may be one factor among many influencing these outcomes, but its relative importance requires further investigation.

In addition, emotional intelligence (Delhom et al., 2020; Mousa et al., 2017; Rey et al., 2011; Sarıcam et al., 2015; Sharmin et al., 2019), self-efficacy (D’Souza et al., 2020; Munoz et al., 2017; Zhou and Kam, 2016), and job performance (Duggleby et al., 2009; Kudo et al., 2016; Peterson and Byron, 2008) have been identified as key factors influencing hope and life satisfaction. While mindfulness is likely to play a role in these areas, it is important to examine the interactions between these factors and their collective impact on overall well-being. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that a positive educational environment (Yotsidi et al., 2018), creativity, leadership (Anwar et al., 2019; Rego et al., 2014; Wandeler et al., 2016), and effective stress-coping strategies (Cahapay and Bangoc, 2022; Fruh et al., 2021; Hamid, 2020) are also associated with enhanced hope and life satisfaction. These findings suggest that mindfulness alone cannot fully account for well-being, and other personal and environmental factors must also be considered.

Previous research has laid a foundation for understanding the connections between mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction. However, the specific role of meaning in life as a mediator in the positive effects of mindfulness on hope and life satisfaction remains unclear. The present study seeks to explore how dispositional mindfulness contributes to enhancing both hope and life satisfaction, with a particular focus on the potential mediating role of meaning in life in this relationship.

Mindfulness and hope

Mindfulness is a positive mental quality that significantly influences an individual’s mental and psychological development. It enables individuals to lead their lives consciously and independently, fostering emotional awareness that helps them overcome negative feelings while enhancing happiness and satisfaction (Lau et al., 2013). Increased mental attentiveness, which supports better life integration, is a key focus of mindfulness programs designed to raise individuals’ awareness and productivity (Malinowski and Lim, 2015). Mindfulness improves a person’s ability to manage their environment and develop appropriate responses to unpleasant situations by promoting awareness and informed decision-making. It encourages nonjudgmental responses to emotions and feelings (Dobkin and Hassed, 2016; Bluth and Blanton, 2014). Furthermore, mindfulness strengthens a person’s ability to tolerate and regulate negative emotions, contributing to improved emotional resilience (Cho et al., 2017).

Hope is a vital factor that helps individuals accept, cope with, and overcome challenging circumstances. It encourages people to adopt a task-focused approach and take deliberate actions to achieve a better quality of life. Rather than simply improving their own lives, hope fosters constructive and positive interactions and integration within their environments (Snyder, 2002). Hope is linked to several factors crucial for an individual’s success, including professional achievement (Wood, 2022), quality of life (Pais-Ribeiro and Pedro, 2022), psychological well-being (Yalnizca-Yildirim and Cenkseven-Önder, 2023), happiness and optimism (Al-Sadi, 2018; Judeh and Abu-Jarad, 2011), and emotional intelligence (Sharmin et al., 2019). Additional factors associated with hope include self-efficacy (Zhou and Kam, 2016), job performance and satisfaction (Duggleby et al., 2009; Peterson and Byron, 2008), the work and educational environment (Yotsidi et al., 2018), creativity and leadership (Rego et al., 2014), and stress coping strategies (Cahapay and Bangoc, 2022; Fruh et al., 2021; Hamid, 2020).

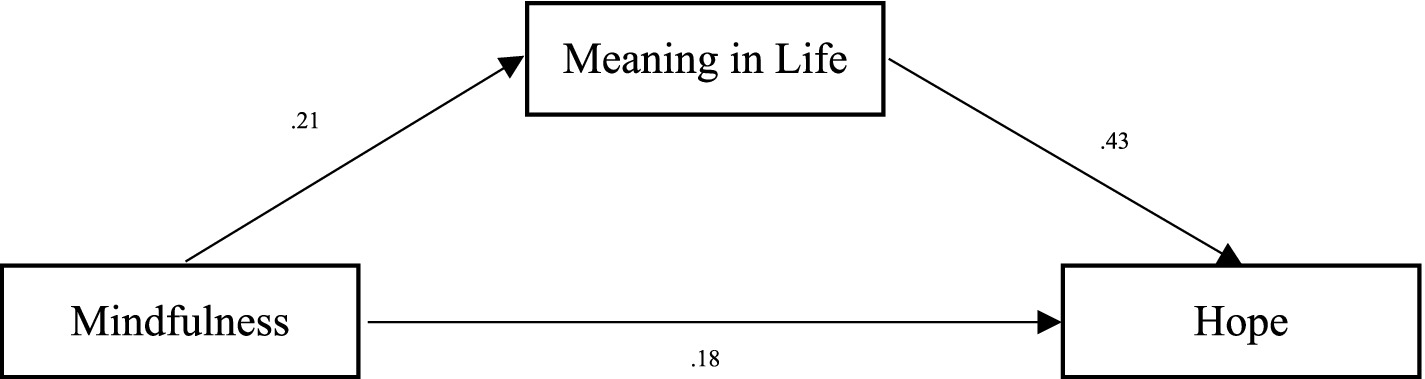

According to Snyder et al. (1991), hope is a positive motivational state defined by a sense of accomplishment, goal-directed energy, and readiness to achieve one’s aspirations. Snyder et al. (1996) expanded on this concept by emphasizing its cognitive component, suggesting that hope involves setting meaningful goals, creating actionable plans, and fostering confidence in one’s ability to achieve them. Furthermore, Snyder et al. (1998) highlighted the critical role of hope in empowering individuals to navigate and overcome obstacles and challenges (Figure 1).

Emerging research suggests a strong positive relationship between mindfulness and hope (Heshmati et al., 2024; Malinowski and Lim, 2015; Satici and Satici, 2022; Singh and Devender, 2015). For example, Munoz et al. (2018) found that individuals who practiced mindfulness regularly exhibited higher levels of hope. This connection likely arises from mindfulness’ ability to cultivate present-moment awareness, reduce negative rumination, and enhance self-compassion, all of which contribute to a more hopeful outlook. However, it is important to note that the relationship between mindfulness and hope remains under investigation, and not all studies have found a significant or strong connection (Bhardwaj and Imran, 2023). Further research is needed to fully understand the complex interplay between these two constructs. Based on these findings, our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1: Dispositional mindfulness positively correlates with hope.

Mindfulness and life satisfaction

Mindfulness is a key element that helps develop constructive mental abilities, benefiting a person’s psychological well-being. It enables individuals to lead balanced lives and positively influence others. A mindful person can overcome negativity and maintain full control over their emotions and feelings. Mindfulness encompasses a variety of techniques aimed at enhancing psychological well-being, life satisfaction, physical clarity, empathy, and mental clarity (Dobkin and Hassed, 2016). By practicing mindfulness, individuals learn to accept situations as they are, even when faced with psychological or emotional strain. Rather than avoiding these circumstances, they can confront them directly (Siegel, 2010; Stahl and Goldstein, 2019; Williams and Penman, 2012). This acceptance helps individuals defend against excessive anxiety and promotes awareness of the physiological states associated with their emotions.

The concept of life satisfaction has garnered significant attention in the fields of mental health and adaptability (Diener et al., 2000). Life satisfaction refers to how individuals evaluate their lives from their own perspective across various dimensions, making it a crucial concept for both psychological health and overall well-being (Diener et al., 2013; Pavot and Diener, 2008). This evaluation can be reflected in how individuals perceive their lives as a whole or in how they assess specific areas, such as satisfaction with work, studies, or personal achievements. It can also be influenced by the frequency of positive experiences, which contribute to psychological well-being and happiness, or negative experiences, which can lead to stress, anxiety, and depression, resulting in varying degrees of dissatisfaction (Akokuwebe et al., 2023; Castelli et al., 2023; Roberts et al., 1983).

According to Mace et al. (2024), mindfulness is a fundamental component of sound awareness. It is based on addressing life’s challenges by accepting situations without judgment, ultimately leading to greater life satisfaction. As a result, studies have found a positive relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction, including research by Chang et al. (2015), Kütük et al. (2023), LeBlanc et al. (2021), Li et al. (2022), Pidgeon and Appleby (2014), Stolarski et al. (2016), and Wang and Kong (2014). A recent study by Zadhasan (2024) examined the roles of locus of control and mindfulness as predictors of life satisfaction. The results indicated that mindfulness significantly predicted life satisfaction, with higher mindfulness scores being associated with greater life satisfaction. This may be due to the strong connection between mindfulness and life satisfaction. Based on these findings, our second hypothesis is as follows:

H2: Dispositional mindfulness positively correlates with life satisfaction.

Meaning in life as a mediator

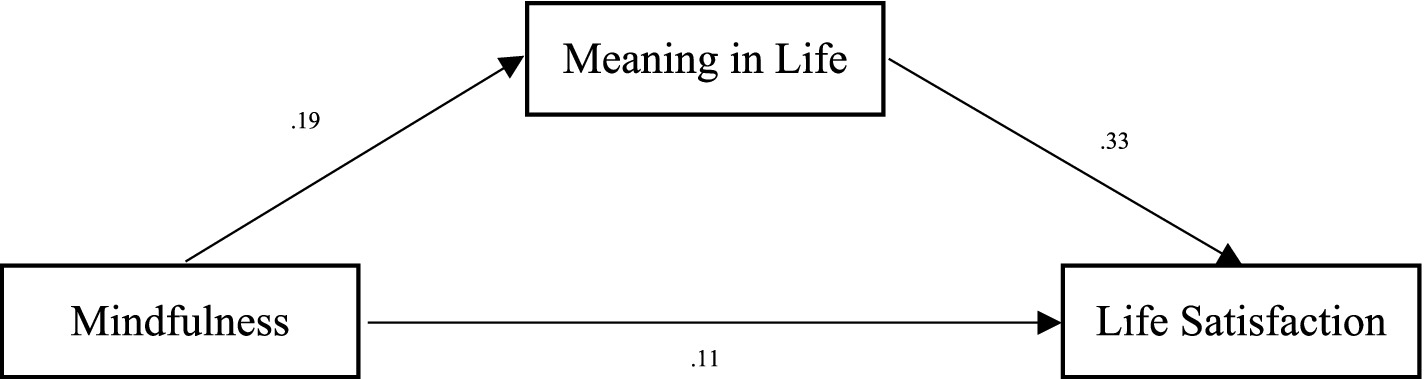

A crucial aspect of psychological well-being is finding purpose in life (Ryff, 1989). It is well-established that having a sense of purpose offers numerous benefits. A sense of purpose has been shown to reduce mortality rates over a lifetime (Hill and Turiano, 2014), improve physical health (Czekierda et al., 2017), and reduce anxiety and the desire for early death in patients with advanced cancer (Breitbart et al., 2010). Mindfulness practices can help individuals find more meaning in life through the development of present-moment awareness, the reduction of negative thoughts, the promotion of self-compassion, and the cultivation of interpersonal connections. These practices, in turn, enhance well-being and foster a more meaningful existence (Allan et al., 2015; Bloch et al., 2017; Chu and Mak, 2020; Hanner, 2024; Koç and Uzun, 2024). Psychological theories elucidate the relationship between mindfulness and meaning in life. For example, Wolf’s framework suggests that mindfulness acts as a mediating factor in the creation of meaning (Hanner, 2024). Chu and Mak (2020) argue that a sense of meaning in life is predicted by positive affect, which results from two tendencies: the inclination to reappraise experiences positively and the disposition to focus on positive experiences. Their meta-analysis revealed a correlation between mindfulness and meaning in life, with the impact of mindfulness being mediated by decentering, authentic self-awareness, and attention to positive experiences (Figure 2).

On the other hand, numerous studies have shown that individuals who find meaning in their lives tend to report higher life satisfaction and view the future more optimistically, which enhances their level of hope (Dursun, 2012; Krok, 2018; Peterson, 2000; Santos et al., 2012). A study by Karataş et al. (2021) examined the relationships between meaning in life, hope, life satisfaction, and COVID-19-related fear. The results revealed positive correlations between meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction, with meaning in life serving as a strong predictor of life satisfaction. Similarly, a study by Bhardwaj and Imran (2023) found a positive relationship between meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction.

While previous studies have laid the groundwork for understanding the relationship between meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction, the specific role of meaning in life as a mediator of the positive effects of dispositional mindfulness on hope and life satisfaction remains unclear. Our study is among the first to examine the role of meaning in life as a mediator between dispositional mindfulness, hope, and life satisfaction. This hypothesis is supported by mindfulness theory in the existing literature (Elices et al., 2019; Follette and Hazlett-Stevens, 2016; Langer and Moldoveanu, 2000; Schonert-Reichl and Roeser, 2016).

Meaning in life theory suggests that having a sense of meaning is closely related to psychological well-being, as individuals who find meaning tend to experience higher levels of hope and life satisfaction (Eagleton, 2007). According to a behavioral model, setting goals that align with personal values enhances the sense of meaning (Klein, 2017; Schippers and Ziegler, 2019). Hope, as described in hope theory, is a fundamental psychological factor that influences behavior and well-being. Research indicates a positive correlation between hope and meaning in life, with hopeful individuals viewing their futures more optimistically (Dursun, 2012; Hedayati and Khazaei, 2014; Peterson, 2000; Yalçın and Malkoç, 2015). Mindfulness enhances self-awareness, reduces negative thoughts, and fosters self-compassion (Evans et al., 2018; Neff and Tirch, 2013; Raab, 2014; Viskovich and De George-Walker, 2019). When individuals perceive their lives as meaningful, their sense of hope increases, motivating them to set and pursue goals, which in turn elevates their levels of hope and life satisfaction. Based on these findings, our third hypothesis is as follows:

H3: Meaning in life may mediate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, hope, and life satisfaction.

Method

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional design to investigate the relationships between dispositional mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction among Chinese university students. Specifically, we examined the mediating role of meaning in life in the association between dispositional mindfulness and both hope and life satisfaction. Furthuremore, the cross-sectional design was chosen for its efficiency in exploring relationships between variables at a single point in time. This approach is well-suited for examining the associations between mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction in a large sample, thereby identifying potential patterns that warrant further investigation. Although a longitudinal design would provide stronger evidence for causality, our cross-sectional approach serves as a necessary first step in elucidating the complex relationships between these factors in the specific population of Chinese university students.

Participants

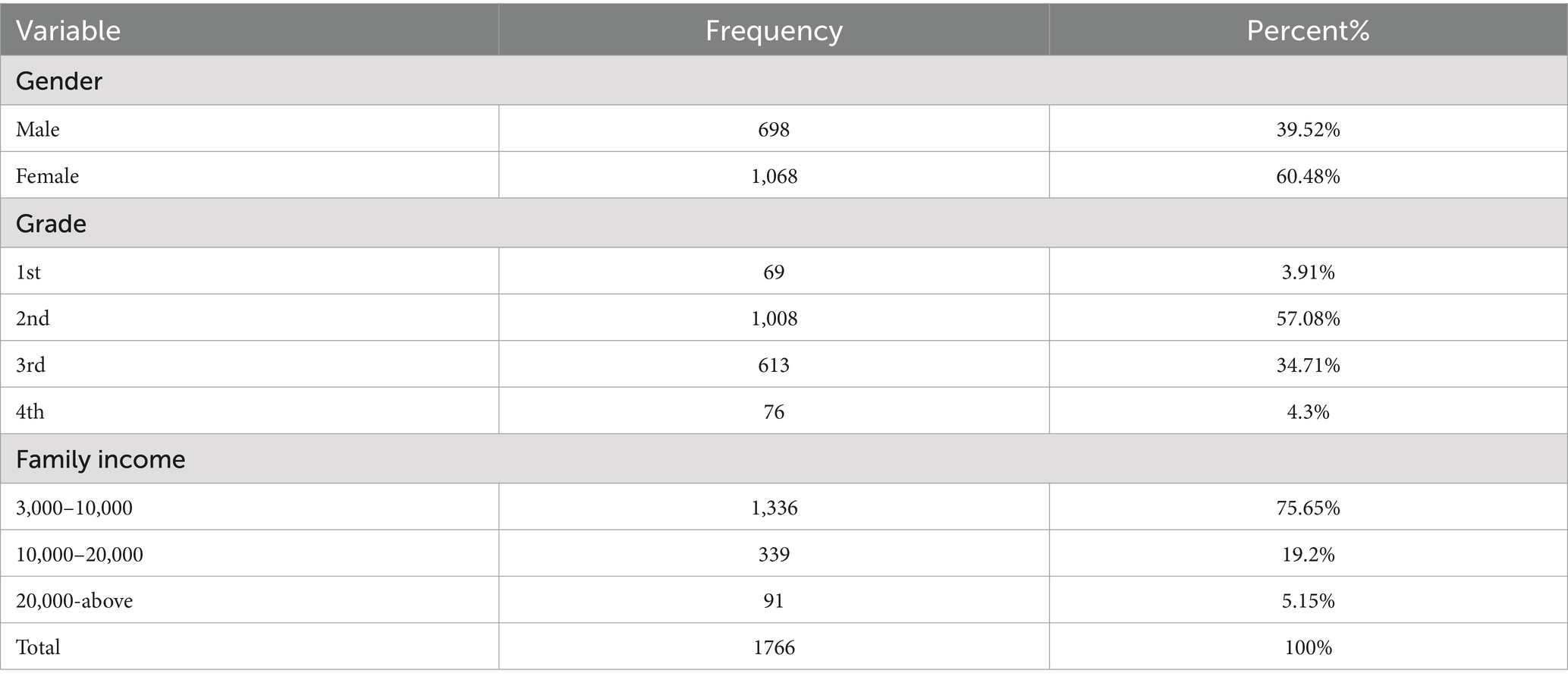

A total of 1,766 college students from Shandong Xiehe University in Jinan, China, voluntarily participated in this study. They provided informed consent, ensuring the privacy of their responses. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 22 years (M = 20.08, SD = 2.44). None of the participants had any prior experience with mindfulness training or related disciplines, such as Tai Chi, Qigong, or yoga. Table 1 presents the demographics of the study participants.

This study focused on Chinese university students for several key reasons. First, the transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a critical developmental stage, characterized by increased academic pressure, social adjustments, and the formation of personal identity and values. These factors can significantly impact mental well-being and the development of positive psychological constructs, such as hope and life satisfaction. Second, cultural values in China, which emphasize collectivism and academic success, may influence how mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction are experienced. Studying this population allows us to explore these relationships within a specific cultural and developmental context, potentially contributing valuable insights into mental health interventions and educational programs tailored to this context. Additionally, university students often face stressors that could benefit from mindfulness and related practices, making them a relevant population for exploring these connections. Finally, using a student sample provides a readily accessible group for conducting this type of study. However, the specificity of the findings from this student sample must be acknowledged, as they may not directly generalize to other populations (e.g., adults outside of university or individuals in other countries). Further research in other populations is needed to establish the generalizability of the findings.

Procedures

Data were collected between August and September 2024 using online questionnaires administered during regularly scheduled classes, after securing the necessary permissions from university officials and relevant academic departments. Participants were given approximately 45–60 min to complete all measures. Research assistants were present to answer questions and oversee the administration of the questionnaires, ensuring standardized procedures. The questionnaires were organized in a specific order.

The study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Xiehe University. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation.

Instruments

Mindfulness

The Chinese version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), which contains 15 items (Brown and Ryan, 2003), has been proven to be a reliable and valid scale in Chinese settings (e.g., Chen et al., 2012). Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale, with one indicating “Almost always” and six indicating “Almost never.” In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Hope

The Chinese version of the Adult Hope Scale (AHS), which contains 12 items (Snyder, 1995), has been proven to be a reliable and valid scale in Chinese settings (e.g., Sun et al., 2012). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from one (Definitely false) to four (Definitely true). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Life satisfaction

The Chinese version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), which contains 5 items (Diener et al., 1985), has been proven to be a reliable and valid scale in Chinese settings (e.g., Xiong and Xu, 2009). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from one (Strongly disagree) to seven (Strongly agree). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

Meaning in life

The Chinese version of the Meaning of Life Questionnaire (MLQ), which contains 10 items (Steger et al., 2006), has been proven to be a reliable and valid scale in Chinese settings (e.g., Liu and Gan, 2010). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from one (Absolutely untrue) to seven (Absolutely true). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Data analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships between the study variables. Mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro (version 3.5) in SPSS. To estimate the 95% confidence intervals for the mediated effects in the models, 5,000 bootstrap resamples were generated (Hayes, 2012).

Results

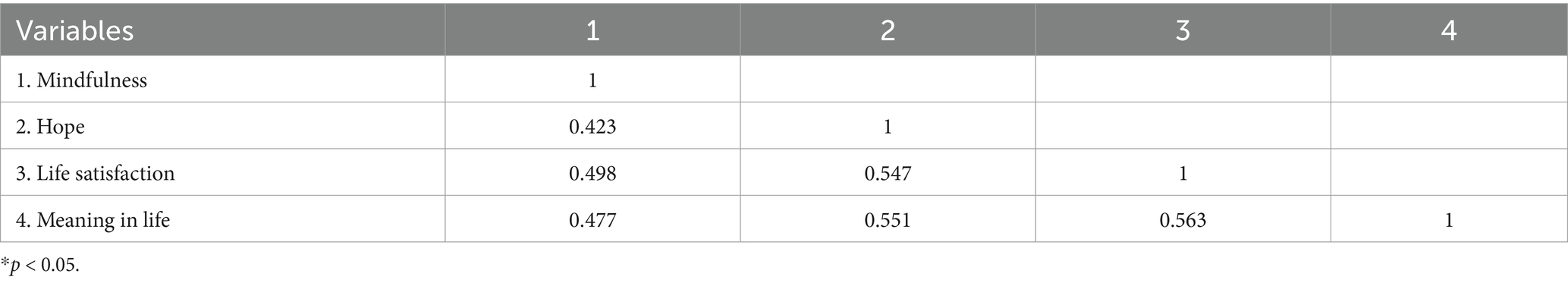

Correlation among study variables

The results (Table 2) show that all the study variables are positively correlated with each other.

Mediation effects

To investigate the influence of mindfulness on hope, the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method (Model 4 in SPSS Macro PROCESS, sample = 5,000, 95% CI) was used to test the mediating effect. When mindfulness was the independent variable, hope and life satisfaction were the dependent variables, and meaning in life was the mediating variable, the results were as follows:

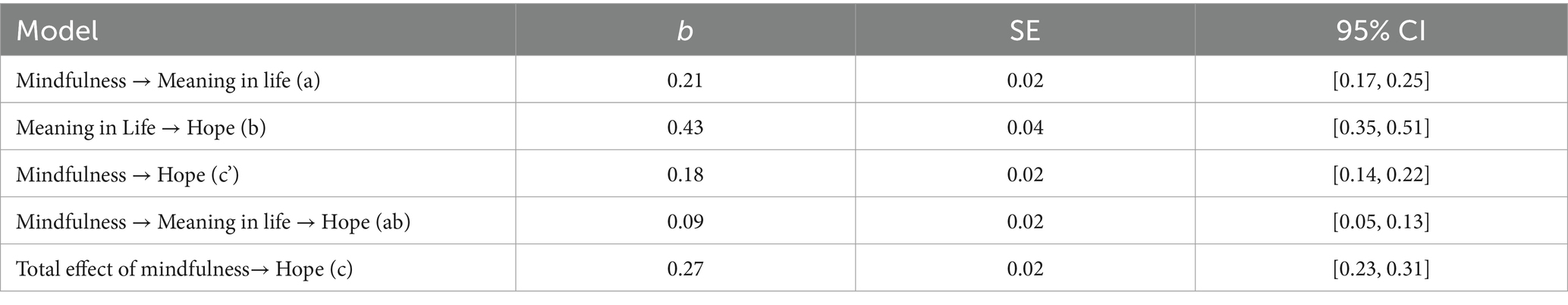

Hope

After controlling for factors that might influence both mindfulness and hope, such as gender, age, grade, experience, and monthly family income, all control variables’ effects were non-significant. The total effect of mindfulness was significant (β = 0.27, p < 0.05), and the direct effect of mindfulness on hope was also significant (β = 0.18, p < 0.05), indicating that mindfulness positively predicted hope. Additionally, meaning in life positively predicted hope. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the indirect effect of mindfulness on hope through meaning in life was significant, ab = 0.09, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.13]. These results suggest that meaning in life partially mediated the effect of mindfulness on hope. For more details, see Table 3.

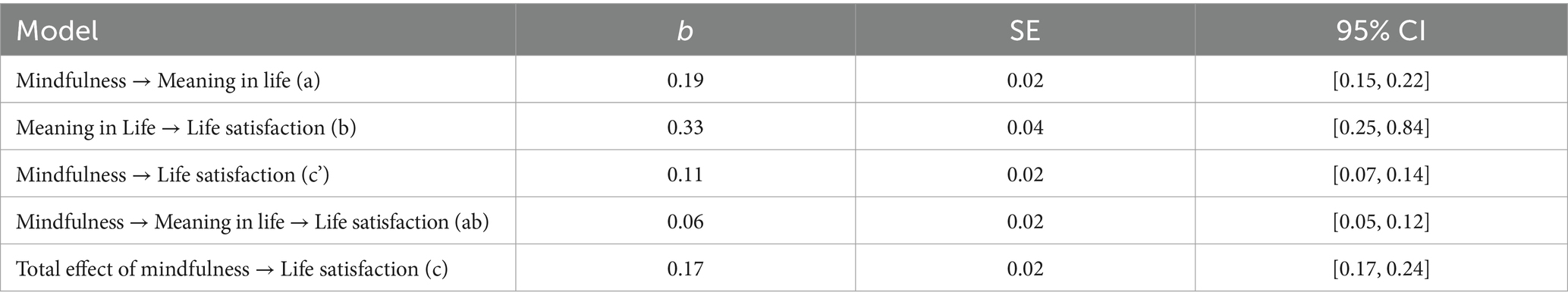

Life satisfaction

After controlling for factors that might influence both mindfulness and life satisfaction, such as gender, age, grade, experience, and monthly family income, all control variables’ effects were non-significant. The total effect of mindfulness was significant (β = 0.17, p < 0.05), and the direct effect of mindfulness on life satisfaction was significant (β = 0.11, p < 0.05), indicating that mindfulness positively predicted life satisfaction. Additionally, meaning in life positively predicted life satisfaction. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that the indirect effect of mindfulness on life satisfaction through meaning in life was significant, ab = 0.06, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.12]. These results suggest that meaning in life partially mediated the effect of mindfulness on life satisfaction. For more details, see Table 4.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction. The results of our study revealed that dispositional mindfulness is positively correlated with meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction. These findings are partially consistent with several studies that have also found positive correlations between mindfulness and meaning in life (Allan et al., 2015; Chu and Mak, 2020; Li et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2021), mindfulness and hope (Malinowski and Lim, 2015; Satici and Satici, 2022; Singh and Devender, 2015), and mindfulness and life satisfaction (Abbasi et al., 2024; Bajaj and Pande, 2016; Kan et al., 2024; Li et al., 2022; Stolarski et al., 2016). These results highlight mindfulness’s role in enhancing present-moment awareness, engaging fully in current experiences, adopting a nonjudgmental perspective, and identifying what is important, all of which foster self-compassion and interpersonal connections—key elements for deriving meaning in life. Furthermore, individuals with higher dispositional mindfulness are more likely to re-evaluate situations positively and focus on positive experiences, which in turn enhances their sense of hope and life satisfaction.

The second aim of our study was to explore the possibility that meaning in life mediates the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, hope, and life satisfaction. The results confirmed our hypothesis that meaning in life partially mediated this relationship. Although this study is the first to examine this role, previous theoretical literature supports this finding through mindfulness theory, meaning in life theory, and hope theory.

Mindfulness theory emphasizes the importance of present-moment awareness and acceptance in enhancing mental health, helping individuals better understand their thoughts and feelings (Baer and Huss, 2008; Elices et al., 2019; Follette and Hazlett-Stevens, 2016). This understanding can lead to deeper experiences of meaning in life. In parallel, meaning in life theory suggests that having a sense of meaning is closely linked to psychological well-being (Eagleton, 2007). Individuals who find meaning in their lives tend to report higher levels of hope and satisfaction (Cotton Bronk et al., 2009). According to a behavioral model, when individuals set goals that align with their personal values, their sense of meaning is enhanced (Klein, 2017; Schippers and Ziegler, 2019).

Hope theory further posits that hope is an essential psychological factor influencing behavior and well-being. Research indicates that hope is positively correlated with meaning in life, as hopeful individuals tend to view their futures more optimistically (Bailey et al., 2007; Dursun, 2012; Peterson, 2000). Mindfulness promotes self-awareness, helping individuals recognize their values and goals. By reducing negative thoughts and fostering self-compassion, mindfulness can lead to an increased sense of meaning in life. When individuals perceive their lives as meaningful, it enhances their sense of hope (Bloch et al., 2017; Scheier and Carver, 1993). Meaning in life motivates individuals to set and pursue their goals, thus increasing hope and life satisfaction, as individuals who are satisfied with their lives find value in their experiences.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. One major limitation is the use of self-report questionnaires, which may introduce bias into the data. For instance, social desirability bias may lead individuals to overreport socially favorable behaviors or underreport undesirable ones, potentially inflating the correlations observed in this study. Therefore, further research using objective measures is needed to confirm these results.

Another limitation is that our sample was drawn from undergraduate students at a single university in China, which limits the generalizability of our findings. While we provided a rationale for using this sample in the methods section, it is important to recognize that the observed associations may be specific to this group. Caution should be exercised when applying these conclusions to other populations. For example, our sample consisted of university students within a specific age range and without prior mindfulness experience, further limiting generalizability. Differences in cultural context, age, or educational background may influence the relationships between mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction.

Additionally, the cross-sectional design of this study prevents us from drawing causal inferences about the relationships between the variables. While we observed significant associations and established a mediating role, we cannot conclude whether increased mindfulness causes an increase in meaning in life, for example. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish causality.

Finally, we did not account for potential variables that might affect the results, such as academic stress, mental health conditions, and socioeconomic status. These factors may also influence the relationships examined in this study. Future research should consider these variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics between mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction.

Future research should expand sample diversity by replicating this study across diverse samples encompassing various age groups, ethnic backgrounds, socioeconomic levels, and educational institutions to evaluate the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, longitudinal designs should be used to establish the directionality of the observed relationships. This will allow us to better understand cause and effect and how mindfulness, meaning, hope, and life satisfaction change over time. Researchers should also employ multiple measurement methods, supplementing self-report measures with other methods, such as behavioral assessments and neurobiological measures, to reduce potential bias. In addition, it will be important to investigate other potential mediators and moderators influencing the connections between mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction. This includes examining factors like academic stress, mental health conditions, and cultural values. Finally, intervention studies should be conducted where mindfulness-based programs are implemented to directly examine the effects of increasing mindfulness on meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction and future studies should explore the empirical connections between other forms of mindfulness practice (e.g., meditation, movement-based practices) and how they relate to other aspects of student life, such as personality and academic performance.

Conclusion

This study highlights the positive relationships between dispositional mindfulness, meaning in life, hope, and life satisfaction. Our findings demonstrate that mindfulness not only enhances individuals’ present-moment awareness and self-compassion but also fosters a deeper sense of meaning, which, in turn, boosts their hope and overall life satisfaction. Additionally, the results confirm the mediating role of meaning in life in the relationship between mindfulness and both hope and life satisfaction, suggesting that mindfulness plays a critical role in shaping psychological well-being through its impact on meaning. However, the study’s reliance on self-report measures presents limitations, particularly concerning potential biases toward socially desirable responses. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating more diverse populations and exploring alternative methods of data collection. Expanding the scope of research will help determine whether these findings are generalizable across different educational contexts. Moreover, exploring the relationship between mindfulness and other aspects of student life, such as personality and academic performance, could provide further valuable insights. Ultimately, this study underscores the importance of mindfulness in enhancing well-being and offers a foundation for further exploration in both academic and personal contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The current study was produced following the ethical norms of the academic committee of the College of Humanities, Arts and Education, Shandong Xiehe University, the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and comparable standards of care in all procedures involving human subjects.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GW: Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Resources, Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. YQ: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. JaL: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. JeL: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors extend their appreciation to Shandong Xiehe University for funding this research work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, P. N., Aziz, Z., Gillani, A., and Nazir, R. (2024). Relationship of dispositional mindfulness with life satisfaction and psychological well-being among university students. Remit. Rev. 9, 4039–4056. doi: 10.33282/rr.vx9i2.210

Abdolghaderi, M., Kafi, S.-M., Saberi, A., and Ariaporan, S. (2018). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on hope and pain beliefs of patients with chronic low back pain. Caspian J. Neurol. Sci. 4, 18–23. doi: 10.29252/nirp.cjns.4.12.18

Agastya, K. D. (2023). How is the student emotional intelligence enhanced by developing mindfulness approach in the higher education school? Lighthouse Int. Conf. Proceed. 1, 251–258.

Akokuwebe, M. E., Osuafor, G. N., Likoko, S., and Idemudia, E. S. (2023). Health services satisfaction and medical exclusion among migrant youths in Gauteng Province of South Africa: a cross-sectional analysis of the GCRO survey (2017-2018). PLoS One 18, 1–26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293958

Allan, B. A., Bott, E. M., and Suh, H. (2015). Connecting mindfulness and meaning in life: exploring the role of authenticity. Mindfulness 6, 996–1003. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0341-z

Al-Sadi, R. (2018). The effect of feeling hopeful towards life orientation among Cancer patients at the Palestine medical compound/Ramallah. Int. J. Educ. Res. 6, 277–294.

Anwar, A., Abid, G., and Waqas, A. (2019). Authentic leadership and creativity: moderated meditation model of resilience and hope in the health sector. Eur. J. Investig. Health, Psychol. Educ. 10, 18–29. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe10010003

Baer, R. A., and Huss, D. B. (2008). Mindfulness-and acceptance-based therapy. Twenty-first century psychotherapies: Contemporary approaches to theory and practice, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2007). 123–166.

Bailey, T. C., Eng, W., Frisch, M. B., and Snyder, C. R. (2007). Hope and optimism as related to life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2, 168–175. doi: 10.1080/17439760701409546

Bajaj, B., and Pande, N. (2016). Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 93, 63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005

Bhardwaj, M., and Imran, M. (2023). The influence of mindfulness on Hope, resilience, and psychological well-being of Young adults. Int. J. Ind. Psychȯl. 11, 1–22. doi: 10.25215/1103.139

Bloch, J. H., Farrell, J. E., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Penberthy, J. K., and Davis, D. E. (2017). The effectiveness of a meditation course on mindfulness and meaning in life. Spiritual. Clin. Pract. 4, 100–112. doi: 10.1037/scp0000119

Bluth, K., and Blanton, P. W. (2014). Mindfulness and self-compassion: Exploring pathways to adolescent emotional well-being. J. Child Family Studies. 23, 1298–1309.

Breitbart, W., Rosenfeld, B., Gibson, C., Pessin, H., Poppito, S., Nelson, C., et al. (2010). Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 19, 21–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556

Brown, K. W., and Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cahapay, M. B., and Bangoc, N. F. II (2022). Hope and resilience mediate relationship between stress and satisfaction with life of teachers amid COVID-19 crisis in the Philippines. IJERI Innov. 18, 296–306. doi: 10.46661/ijeri.6262

Castelli, C., d’Hombres, B., Dominicis, L. D., Dijkstra, L., Montalto, V., and Pontarollo, N. (2023). What makes cities happy? Factors contributing to life satisfaction in European cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 30, 319–342. doi: 10.1177/09697764231155335

Chang, J.-H., Huang, C.-L., and Lin, Y.-C. (2015). Mindfulness, basic psychological needs fulfillment, and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 16, 1149–1162. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9551-2

Chen, S.-Y., Cui, H., Zhou, R.-L., and Jia, Y.-Y. (2012). Revision of mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 20, 148–151.

Cho, S., Lee, H., Oh, K. J., and Soto, J. A. (2017). Mindful attention predicts greater recovery from negative emotions, but not reduced reactivity. Cognit. Emotion. 31, 1252–1259.

Chu, S. T.-W., and Mak, W. W. (2020). How mindfulness enhances meaning in life: a meta-analysis of correlational studies and randomized controlled trials. Mindfulness 11, 177–193. doi: 10.1007/s12671-019-01258-9

Cotton Bronk, K., Hill, P. L., Lapsley, D. K., Talib, T. L., and Finch, H. (2009). Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 500–510. doi: 10.1080/17439760903271439

Czekierda, K., Banik, A., Park, C. L., and Luszczynska, A. (2017). Meaning in life and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 11, 387–418. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2017.1327325

D’Souza, J. M., Zvolensky, M. J., Smith, B. H., and Gallagher, M. W. (2020). The unique effects of hope, optimism, and self-efficacy on subjective well-being and depression in German adults. J. Well Being Assess. 4, 331–345. doi: 10.1007/s41543-021-00037-5

Delhom, I., Satorres, E., and Meléndez, J. C. (2020). Can we improve emotional skills in older adults? Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction, and resilience. Psychosoc. Interv. 29, 133–139. doi: 10.5093/pi2020a8

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., and Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 112, 497–527. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y

Diener, E., Napa-Scollon, C. K., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., and Suh, E. M. (2000). Positivity and the construction of life satisfaction judgments: global happiness is not the sum of its parts. J. Happiness Stud. 1, 159–176. doi: 10.1023/A:1010031813405

Dobkin, P. L., and Hassed, C. S. (2016). Mindful medical practitioners. A guide for clinicians and educators. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Du, J., An, Y., Ding, X., Zhang, Q., and Xu, W. (2019). State mindfulness and positive emotions in daily life: An upward spiral process. Personal. Individ. Differ. 141, 57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.037

Duggleby, W., Cooper, D., and Penz, K. (2009). Hope, self-efficacy, spiritual well-being and job satisfaction. J. Adv. Nurs. 65, 2376–2385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05094.x

Dursun, P. (2012). The role of meaning in life, optimism, hope and coping styles in subjective well-being (Open METU University, Graduate School of Social Sciences, Thesis). Available at: https://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12615217/index.pdf.

El Shobaky, A. M., Al Shobaki, M. J., El Talla, S. A., and Abu-Naser, S. S. (2020). Psychological capital and its relationship to the sense of vitality among administrative employees in universities. Int. J. Acad. Account. Fin. Manag. Res. 10, 69–86.

Elices, M., Tejedor, R., Pascual, J. C., Carmona, C., Soriano, J., and Soler, J. (2019). Acceptance and present-moment awareness in psychiatric disorders: is mindfulness mood dependent? Psychiatry Res. 273, 363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.041

Evans, S., Wyka, K., Blaha, K. T., and Allen, E. S. (2018). Self-compassion mediates improvement in well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program in a community-based sample. Mindfulness 9, 1280–1287. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0872-1

Follette, V. M., and Hazlett-Stevens, H. (2016). “Mindfulness and acceptance theories” in APA handbook of clinical psychology: Theory and research (Vol. 2). eds. J. C. Norcross, G. R. VandenBos, D. K. Freedheim, and B. O. Olatunji (Washington: American Psychological Association), 273–302.

Fruh, S. M., Taylor, S. E., Graves, R. J., Hayes, K., McDermott, R., Hauff, C., et al. (2021). Relationships among hope, body satisfaction, wellness habits, and stress in nursing students. J. Prof. Nurs. 37, 640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.01.009

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P. R., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: a process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychol. Inq. 26, 293–314. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294

Hamid, N. (2020). Study of the relationship of hardiness and hope with life satisfaction in managers. Int. J. Psychol. 14, 310–339. doi: 10.22034/IJPB.2020.214143.1143

Hanner, O. (2024). Mindfulness meditation and the meaning of life. Mindfulness 15, 2372–2385. doi: 10.1007/s12671-024-02404-8

Hassan, K., Sadaf, S., Saeed, A., and Idrees, A. (2018). Relationship between hope, optimism and life satisfaction among adolescents. Int. J. Scient. Engineering. Res. 9, 1452–1457. doi: 10.14299/ijser.2018.10.09

Hayes, A. (2012). Process: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. (University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, CANADA).

Hedayati, M. M., and Khazaei, M. M. (2014). An investigation of the relationship between depression, meaning in life and adult hope. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 114, 598–601. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.753

Heshmati, R., Beshai, S., Azmoodeh, S., and Golzar, T. (2024). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on spiritual well-being and hope in patients with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 16, 223–232. doi: 10.1037/rel0000519

Hill, P. L., and Turiano, N. A. (2014). Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1482–1486. doi: 10.1177/0956797614531799

Hill, C. L., and Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion 12, 81–90. doi: 10.1037/a0026355

Judeh, A., and Abu-Jarad, H. (2011). Predicting happiness in the light of hope and optimism among a sample of the students of Al-Quds Open University. Al-Quds Open Univ. J. Res. Stud. 24, 130–162.

Kan, W., Huang, F., Xu, M., Shi, X., Yan, Z., and Türegün, M. (2024). Exploring the mediating roles of physical literacy and mindfulness on psychological distress and life satisfaction among college students. PeerJ 12:e17741. doi: 10.7717/peerj.17741

Karataş, Z., Uzun, K., and Tagay, Ö. (2021). Relationships between the life satisfaction, meaning in life, hope and COVID-19 fear for Turkish adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 12:633384. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633384

Kardas, F., Cam, Z., Eskısu, M., and Gelıbolu, S. (2019). Gratitude, hope, optimism and life satisfaction as predictors of psychological well-being. Eurasian. J. Educ. Res. 19, 1–20. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2019.82.5

Klein, N. (2017). Prosocial behavior increases perceptions of meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 354–361. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1209541

Koç, M. S., and Uzun, R. B. (2024). Investigating the link between dispositional mindfulness, beliefs about emotions, emotion regulation and psychological health: a model testing study. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 42, 475–494. doi: 10.1007/s10942-023-00522-1

Krok, D. (2018). When is meaning in life most beneficial to young people? Styles of meaning in life and well-being among late adolescents. J. Adult Dev. 25, 96–106. doi: 10.1007/s10804-017-9280-y

Kudo, F. T., Sakuda, K. H., and Tsuru, G. K. (2016). Mediating organizational cynicism: exploring the role of hope theory on job satisfaction. Univ. J. Manag. 4, 678–684. doi: 10.13189/ujm.2016.041204

Kütük, H., Hatun, O., Ekşi, H., and Ekşi, F. (2023). Investigation of the relationships between mindfulness, wisdom, resilience and life satisfaction in Turkish adult population. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 41, 536–551. doi: 10.1007/s10942-022-00468-w

Langer, E. J., and Moldoveanu, M. (2000). Mindfulness research and the future. J. Soc. Issues 56, 129–139. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00155

Lau, H. P. B., White, M. P., and Schnall, S. (2013). Quantifying the value of emotions using a willingness to pay approach. J. Happin. Studies. 14, 1543–1561.

LeBlanc, S., Uzun, B., and Aydemir, A. (2021). Structural relationship among mindfulness, reappraisal and life satisfaction: the mediating role of positive affect. Curr. Psychol. 40, 4406–4415. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00383-x

Li, X., Ma, L., and Li, Q. (2022). How mindfulness affects life satisfaction: based on the mindfulness-to-meaning theory. Front. Psychol. 13:887940. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.887940

Lindsay, E. K., Chin, B., Greco, C. M., Young, S., Brown, K. W., Wright, A. G., et al. (2018). How mindfulness training promotes positive emotions: dismantling acceptance skills training in two randomized controlled trials. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 115, 944–973. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000134

Liu, S., and Gan, Y. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the meaning in life questionnaire. Chin. Ment. Health J. 24, 478–482.

Mace, R. A., Stauder, M. J., Hopkins, S. W., Cohen, J. E., Pietrzykowski, M. O., Philpotts, L. L., et al. (2024). Mindfulness-based interventions targeting modifiable lifestyle behaviors associated with brain health: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. doi: 10.1177/15598276241230467

Malinowski, P., and Lim, H. J. (2015). Mindfulness at work: positive affect, hope, and optimism mediate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, work engagement, and well-being. Mindfulness 6, 1250–1262. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0388-5

Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., and Qian, S. (2018). The relationship between emotional intelligence and trait mindfulness: a meta-analytic review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 135, 101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.051

Montgomery, K., Norman, P., Messenger, A., and Thompson, A. (2016). The importance of mindfulness in psychosocial distress and quality of life in dermatology patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 175, 930–936. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14719

Mousa, A., Menssey, R. F. M., and Kamel, N. M. F. (2017). Relationship between perceived stress, emotional intelligence and hope among intern nursing students. IOSR J. Nur. Health Sci. 6, 75–83. doi: 10.9790/1959-0603027583

Munoz, R. T., Hellman, C. M., and Brunk, K. L. (2017). The relationship between hope and life satisfaction among survivors of intimate partner violence: the enhancing effect of self efficacy. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 12, 981–995. doi: 10.1007/s11482-016-9501-8

Munoz, R. T., Hoppes, S., Hellman, C. M., Brunk, K. L., Bragg, J. E., and Cummins, C. (2018). The effects of mindfulness meditation on hope and stress. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 28, 696–707. doi: 10.1177/1049731516674319

Neff, K., and Tirch, D. (2013). Self-compassion and ACT. In Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being, eds. T. B. Kashdan and J. Ciarrochi New Harbinger Publications, Inc. 78–106. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-10674-004

Pais-Ribeiro, J., and Pedro, L. (2022). The importance of hope for quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Austin J. Clin. Neurol. 9:1155.

Pantelides, S. N. (2024). Integration of Mindfulness and Emotional Intelligence in School Settings. In Building Mental Resilience in Children: Positive Psychology, Emotional Intelligence, and Play. (IGI Global), 120–144.

Pavot, W., and Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 3, 137–152. doi: 10.1080/17439760701756946

Peterson, C. (2000). The future of optimism. Amer. Psychol. 55, 44–55. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.44

Peterson, S. J., and Byron, K. (2008). Exploring the role of hope in job performance: results from four studies. J. Organiz. Behav. 29, 785–803. doi: 10.1002/job.492

Pidgeon, A. M., and Appleby, L. (2014). Investigating the role of dispositional mindfulness as a protective factor for body image dissatisfaction among women. Curr. Res. Psychol. 5, 96–103. doi: 10.3844/crpsp.2014.96.103

Prakash, R. S., Hussain, M. A., and Schirda, B. (2015). The role of emotion regulation and cognitive control in the association between mindfulness disposition and stress. Psychol. Aging 30, 160–171. doi: 10.1037/a0038544

Raab, K. (2014). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and empathy among health care professionals: a review of the literature. J. Health Care Chaplain. 20, 95–108. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2014.913876

Rego, A., Sousa, F., Marques, C., and e Cunha, M. P. (2014). Hope and positive affect mediating the authentic leadership and creativity relationship. J. Bus. Res. 67, 200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.10.003

Rey, L., Extremera, N., and Pena, M. (2011). Perceived emotional intelligence, self-esteem and life satisfaction in adolescents. Psychosoc. Interv. 20, 227–234. doi: 10.5093/in2011v20n2a10

Roberts, R. E., Pascoe, G. C., and Attkisson, C. C. (1983). Relationship of service satisfaction to life satisfaction and perceived well-being. Eval. Program Plann. 6, 373–383. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90016-2

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Santos, M. C. J., Magramo, C. Jr., Oguan, F. Jr., Paat, J. J., and Barnachea, E. A. (2012). Meaning in life and subjective well-being: is a satisfying life meaningful? Res. World J Arts Sci. Comm. 3, 32–41.

Sarıcam, H., Celık, İ., and Coşkun, L. (2015). The relationship between emotional intelligence, hope and life satisfaction in preschool preserves teacher. Int. J. Res. Teach. Educ. 6, 1–9.

Satici, B., and Satici, S. A. (2022). Mindfulness and subjective happiness during the pandemic: longitudinal mediation effect of hope. Personal. Individ. Differ. 197:111781. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111781

Scheier, M. F., and Carver, C. S. (1993). On the power of positive thinking: the benefits of being optimistic. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2, 26–30. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770572

Schippers, M. C., and Ziegler, N. (2019). Life crafting as a way to find purpose and meaning in life. Front. Psychol. 10:2778. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02778

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., and Roeser, R. W. (2016). Handbook of mindfulness in education: Integrating theory and research into practice. Springer-Verlag: Springer Nature.

Sevari, K., Pilram, P., and Farzadi, F. (2020). The causal relationship between perceived social support and life satisfaction through hope, resilience and optimism. Int. J. Psychol. 14, 83–113. doi: 10.22034/ijpb.2019.166650.1081

Sharmin, N., Parvin, M., and Nahar, N. (2019). Relations of Hope and emotional intelligence. Bangl. J. Psychol. 22, 129–140.

Siah, P. C. (2024). Non-attachment, sense of coherence and happiness: an examination of their relationships through the Buddhist concept of virtue-meditation-wisdom. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 1-16, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2024.2342975

Siegel, R. D. (2010). The mindfulness solution: Everyday practices for everyday problems. New York, USA: Guilford Press.

Singh, S., and Devender, S. (2015). Hope and mindfulness as correlates of happiness. Ind. J. Positive Psychol. 6, 422–425.

Snyder, C. R. (1995). Conceptualizing, measuring, and nurturing hope. J. Couns. Dev. 73, 355–360. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01764.x

Snyder, R. A. (2010). Mindful mamas: A phenomenological study of mindfulness in early motherhood. San Francisco, USA: California Institute of Integral Studies.

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., et al. (1991). The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 570–585. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Snyder, C. R., LaPointe, A. B., Jeffrey Crowson, J., and Early, S. (1998). Preferences of high-and low-hope people for self-referential input. Cognit. Emot. 12, 807–823. doi: 10.1080/026999398379448

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., and Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the state Hope scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 321–335. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321

Stahl, B., and Goldstein, E. (2019). A mindfulness-based stress reduction workbook. California, USA: New Harbinger Publications.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., and Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 53, 80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

Stolarski, M., Vowinckel, J., Jankowski, K. S., and Zajenkowski, M. (2016). Mind the balance, be contented: balanced time perspective mediates the relationship between mindfulness and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 93, 27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.039

Sun, Q., Ng, K.-M., and Wang, C. (2012). A validation study on a new Chinese version of the dispositional Hope scale. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 45, 133–148. doi: 10.1177/0748175611429011

Tan, C.-S., Hashim, I. H. M., Pheh, K.-S., Pratt, C., Chung, M.-H., and Setyowati, A. (2021). The mediating role of openness to experience and curiosity in the relationship between mindfulness and meaning in life: evidence from four countries. Curr. Psychol. 42, 327–337. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01430-2

Thornton, L. M., Cheavens, J. S., Heitzmann, C. A., Dorfman, C. S., Wu, S. M., and Andersen, B. L. (2014). Test of mindfulness and hope components in a psychological intervention for women with cancer recurrence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 1087–1100. doi: 10.1037/a0036959

Tomlinson, E. R., Yousaf, O., Vittersø, A. D., and Jones, L. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness and psychological health: a systematic review. Mindfulness 9, 23–43. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0762-6

Viskovich, S., and De George-Walker, L. (2019). An investigation of self-care related constructs in undergraduate psychology students: self-compassion, mindfulness, self-awareness, and integrated self-knowledge. Int. J. Educ. Res. 95, 109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.02.005

Wandeler, C. A., Marques, S. C., and Lopez, S. J. (2016). Hope at work. Wiley Blackwell Handbook Psychol. Positivity Strengths Based Approach. Work 48-59. doi: 10.1002/9781118977620.ch4

Wang, X. (2023). Exploring positive teacher-student relationships: the synergy of teacher mindfulness and emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 14:1301786. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1301786

Wang, X., Dai, Z., Zhu, X., Li, Y., Ma, L., Cui, X., et al. (2024). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on quality of life of breast cancer patient: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 19:e0306643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0306643

Wang, Y., and Kong, F. (2014). The role of emotional intelligence in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and mental distress. Soc. Indic. Res. 116, 843–852. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0327-6

Warsah, I., Chamami, M. R., Prastuti, E., Morganna, R., and Iqbal, M. M. (2023). Insights on mother’s subjective well-being: the influence of emotion regulation, mindfulness, and gratitude. Psikohumaniora 8, 51–68. doi: 10.21580/pjpp.v8i1.13655

Williams, M., and Penman, D. (2012). Mindfulness: An eight-week plan for finding peace in a frantic world. Rodale.

Wood, S. E. (2022). Exploring Hope and its impact on the career success of senior military officers. Arizona, USA: Grand Canyon University.

Xiong, C., and Xu, Y. (2009). Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale in the General Population. Chinese J Health Psychol. 17, 948–949.

Yalçın, İ., and Malkoç, A. (2015). The relationship between meaning in life and subjective well-being: forgiveness and hope as mediators. J. Happiness Stud. 16, 915–929. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9540-5

Yalnizca-Yildirim, S., and Cenkseven-Önder, F. (2023). Sense of coherence and subjective well-being: the mediating role of hope for college students in Turkey. Curr. Psychol. 42, 13061–13072. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02478-w

Yotsidi, V., Pagoulatou, A., Kyriazos, T., and Stalikas, A. (2018). The role of hope in academic and work environments: An integrative literature review. Psychology 9, 385–402. doi: 10.4236/psych.2018.93024

Zadhasan, Z. (2024). Predictors of life satisfaction: the role of mindfulness and locus of control. J. Personal. Psychosomatic Res. 2, 4–9. doi: 10.61838/kman.jppr.2.1.2

Keywords: hope, life satisfaction, meaning in life, mindfulness, psychological well-being

Citation: Aldbyani A, Wang G, Chuanxia Z, Qi Y, Li J and Leng J (2025) Dispositional mindfulness and psychological well-being: investigating the mediating role of meaning in life. Front. Psychol. 15:1500193. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1500193

Edited by:

Adelinda Araujo Candeias, University of Evora, PortugalReviewed by:

Edgar Galindo, University of Evora, PortugalMaria Joao Beja, University of Madeira, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Aldbyani, Wang, Chuanxia, Qi, Li and Leng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aamer Aldbyani, YWFtZXJhbGRieWFuaUBzZHhpZWhlLmVkdS5jbg==

†ORCID: Aamer Aldbyani, orcid.org/0000-0002-8803-1754

Aamer Aldbyani

Aamer Aldbyani Guiyun Wang1

Guiyun Wang1