Editorial on the Research Topic

Adult functional (il)literacy: a psychological perspective

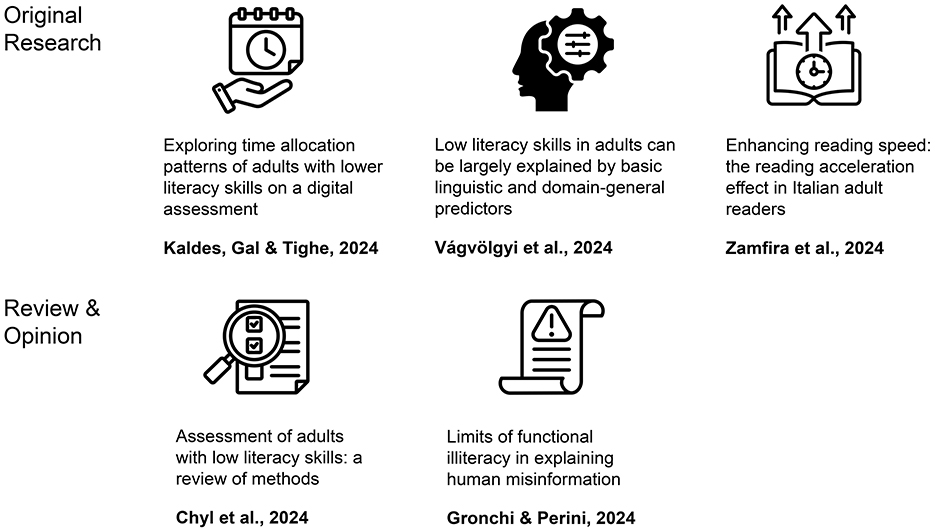

Learning to read is a crucial part of the primary education curriculum. However, reading is also indispensable outside the classroom and throughout adulthood. The inability to apply reading skills in everyday contexts is a severe obstacle to full participation in modern life. The purpose of this Research Topic was to collect the most recent articles focusing on adults with lower literacy skills. Calling for papers, we were interested in the cognitive underpinnings of reading skills, assessment ideas, and possible interventions. In total, we included five articles to the Topic, ranging from original research (Vágvölgyi et al.; Kaldes et al.; Zamfira et al.) to a review (Chyl et al.) and opinion papers (Gronchi and Perini), that will interest psychologists, educators, and other specialists. Noteworthy, our collection is not limited to studies performed in English, the language dominating the science of reading (Share, 2021). We have insights from different alphabetic scripts, varied in orthographic transparency. For the table of contents of our Topic, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Articles collected in the Research Topic “Adult functional (il)literacy: a psychological perspective”. Designed by Freepik https://www.freepik.com/.

The use of the term ‘functional illiteracy' in the title of this research topic (and subsequently this editorial) has prompted a discussion about the language employed in both research and public discourse. While “functional illiteracy” traditionally refers to the inability to read and write at a level necessary for everyday tasks, its use can be problematic. The term carries the risk of stigmatizing individuals who struggle with reading, potentially reinforcing harmful stereotypes and marginalizing those who are already vulnerable. This discussion is similar to the debate on terms “dyslexia” and “dyslexics”, but the term “illiterate” is even less neutral. Nobody wants to be considered “illiterate”, regardless of the adjective. From the practical perspective, recruitment for research using this term can be difficult or even unethical, and communicating research results can be prone to misinterpretations (e.g., confusing “functional illiteracy” with “illiteracy”). We agree that more descriptive terminology (“adults with lower literacy skills”, “low literacy skills”) should become a new standard in the discipline and replace the formerly used term “functional illiteracy”.

Another problem with the term “functional illiteracy” discussed by Vágvölgyi et al., Gronchi and Perini, and Chyl et al., potentially inherited by the better term “lower literacy skill” is its operationalization. The definitions can vary greatly (Perry et al., 2017) or are not included in the papers at all (Perry et al., 2018). In the literature, the concept of “functional literacy” has also been extended to include, e.g., professional literacy or information literacy, which can be practical for researchers but further obscures the terminological chaos (Gronchi and Perini). The term “functional illiteracy” can also be tempting for researchers studying misinformation, as it seems to offer “simple explanations”, but the actual picture is much more complex (Gronchi and Perini). Low literacy skills, on the other hand, can mean both “decoding” and “practical skill use” depending on the context and research tradition (Chyl et al.). Defining the chosen term and selecting the appropriate assessment tools for the operational definition is essential. We strongly advise always to do that.

Two of the original articles in our Topic directly explore the cognitive underpinnings of low literacy skills. Kaldes et al. used publicly available data from the U.S. PIAAC study. The researchers analyzed time allocation patterns during test-taking (PIAAC's Level 2 and below). They found differences between proficiency levels and, importantly, a lot of heterogeneity within the group of adults with lower literacy skills. Divergent demographic profiles accompanied the two clusters of the fastest and slowest responders. As often only accuracy is examined in the studies on reading comprehension, much additional information goes unnoticed. The second original research comes from Vágvölgyi et al., who examined adult German speakers from basic education courses. The study investigated which linguistic, domain-general, or numerical factors predict reading performance and found that 73% of the variance can be explained by the combination of linguistic variables (decoding, oral semantic, and grammatical comprehension), working memory, and age. These results can drive interventions planned for adults with low literacy skills. In a semi-transparent orthography such as German, it could be helpful to focus on decoding, and both written and oral comprehension (Kindl and Lenhard, 2023).

An interesting addition to our Topic is an Italian study reporting a reading acceleration effect (Zamfira et al.). The protocol was based on previous Breznitz studies (e.g., Breznitz and Share, 1992). It relied on the assumption that readers can enhance their reading speed while maintaining high comprehension levels if they are forced to read faster than their usual reading rate. Even though all participants were typically reading university students, there was some variability in their reading speed, and slower readers showed the highest gains in reading speed. In this study, the enhanced reading did not compromise accuracy; however, only simple, local comprehension was measured, reaching the ceiling effect. The authors claim that this protocol may improve reading proficiency in different populations. It is time to check that also in adults with low literacy skills. Improvement in decoding efficiency in this group could support functional reading of everyday life texts.

Despite the importance of reading skills in the everyday life of adults in the modern world, the reading research is dominated by the school context, reading acquisition in young children, and problems caused by developmental dyslexia, especially in English. We believe that the articles collected in our Topic are a valuable addition to the discipline and move our understanding of low literacy skills forward.

Author contributions

KC: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by National Science Center, Poland (grant 2022/44/C/HS6/00045).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Breznitz, Z., and Share, D. L. (1992). Effects of accelerated reading rate on memory for text. J. Educ. Psychol. 84, 193–199. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.84.2.193

Kindl, J., and Lenhard, W. (2023). A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of functional literacy interventions for adults. Educ. Res. Rev. 41:100569. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100569

Perry, K. H., Shaw, D. M., Ivanyuk, L., and Tham, Y. S. S. (2017). Adult functional literacy: prominent themes, glaring omissions, and future directions. J. Lang. Liter. Educ. 13, 1–37.

Perry, K. H., Shaw, D. M., Ivanyuk, L., and Tham, Y. S. S. (2018). The ‘ofcourseness' of functional literacy: ideologies in adult literacy. J. Literacy Res. 50, 74–96. doi: 10.1177/1086296X17753262

Keywords: low reading skills, adult literacy, adults with low literacy skills, adult readers, editorial

Citation: Chyl K (2024) Editorial: Adult functional (il)literacy: a psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 15:1483889. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1483889

Received: 20 August 2024; Accepted: 23 August 2024;

Published: 23 September 2024.

Edited and reviewed by: Eddy J. Davelaar, Birkbeck, University of London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Chyl. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katarzyna Chyl, ay5jaHlsQG5lbmNraS5lZHUucGw=

Katarzyna Chyl

Katarzyna Chyl