- 1Department of Social Sciences and Policy Studies, The Education University of Hong Kong, Tai Po, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2School of Nursing, Tung Wah College, Ho Man Tin, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3School of Nursing, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Happy Valley, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 4Department of Social Work, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 5Department of Information Systems, Business Statistics and Operations Management, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Clear Water Bay, Hong Kong SAR, China

The increasing prevalence of parenting stress has significant implications for the psychological well-being of both parents and children. In view of this, our study sought to examine the mediating and moderating role of family resilience in the association between child-friendly family and parenting stress. Our analysis involved a sample of 316 parents who dedicated a minimum of 14 h per week to caring for their children. The parents were invited to complete three validated instruments—the parenting stress index short form (PSI), the family resilience assessment scale (FRAS), and inventory of the child-friendly family (ICF)—to evaluate their level of parenting stress, family resilience, and child-friendly family, respectively. We tested the mediation model by applying structural equation model analysis. It was found that child-friendly family negatively correlated with parenting stress (path coefficient = −0.56, p < 0.001). This relationship is mediated by family resilience. That is “child-friendly family” leads to increased “family resilience” (path coefficient = 0.68, p < 0.01), which in turn leads to lower “parenting stress” (path coefficient = −0.30, p < 0.05). The mediation effect ratio was 26.70%. We used multiple regression analysis to test the moderation model and found that family resilience did not play a moderating role between child-friendly family and parenting stress. This study holds particular significance for two key reasons: Firstly, it elucidates the relationship between child-friendly family, family resilience, and parenting stress, highlighting the potential of creating a child-friendly family to reduce parenting stress through the enhancement of family resilience. Secondly, our findings provide valuable evidence for the development of innovative approaches that effectively and sustainably alleviate parenting stress.

Introduction

Parenting stress refers to the distress or discomfort that parents experience in fulfilling their parenting responsibilities and roles (Mohammadkhani Orouji, 2021). It is the feeling of being overwhelmed, anxious, or fatigued due to the demands and challenges of raising children (Bornstein, 2002). Recent research indicates that the prevalence of high parenting stress has increased significantly (Aviles et al., 2024). A 2023 survey found that four-in-ten parents (41%) expressed being a parent is tiring and 29% said it is stressful all or most of the time (Minkin and Horowitz, 2023). The rise in parenting stress is possibly due to the increase in single-parent households, children living in poverty, mothers in the workforce, and the living difficulties after the COVID-19 pandemic (Adams et al., 2021).

Parents experiencing high parenting stress have a poor relationship with their children and negatively affect their psychosocial well-being (Robinson and Neece, 2015). Such parents have also been reported to have lower marital quality (Wang et al., 2023). They are also more commonly associated with negative parenting behaviors, such as harsh discipline, hostility, negligence, and child abuse, leading to poorer psychological outcomes for their children and adolescents (Bauch et al., 2022; Schittek et al., 2023). Children raised in high parenting stress families have poorer cognitive skills and learning ability (Zhao et al., 2023). They also demonstrated more social issues, interpersonal difficulties, and internalizing and externalizing problems (Bernier et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2024). Managing parenting stress is therefore important for the well-being of the entire family.

Bowen family systems theory

The Bowen Family Systems Theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the dynamics between parenting stress, child-friendly family, and the role of family resilience. This theory posits that families operate as emotional units, where individual behaviors and stressors are interconnected (Bowen, 1978). In this context, parenting stress can be seen as a manifestation of relational patterns within the family system (Papero, 1990). A child-friendly family environment, characterized by open communication, emotional support, and healthy boundaries, can help mitigate parenting stress by fostering resilience among family members. Family resilience, as outlined in this theory, serves both as a mediator and moderator, influencing how families respond to stressors. When families possess strong resilience, they are better equipped to manage challenges, thereby reducing the negative impacts of parenting stress on parents (Nichols and Schwartz, 2004). Understanding these relationships is crucial for developing effective interventions that promote healthier family dynamics and enhance overall well-being.

Child-friendly family and parenting stress

Interventions for reducing parenting stress have been widely investigated. There are interventions with supporting components (e.g., provision of social support to parents by community nurses; van Grieken et al., 2019), interventions with empowerment and skill development components (e.g., mindfulness parenting and life skills training; Burgdorf et al., 2019), and interventions targeting children’s condition (e.g., behavioral intervention for children; Chavez Arana et al., 2020). However, although most of the available interventions may reduce immediate parenting stress, they cannot effectively and sustainably reduce parenting stress (Golfenshtein et al., 2016). Further investigation into new approaches for parenting stress management is necessary. Research findings have indicated that a parenting training program can increase parents’ locus of control, decrease children’s disruptive behaviors, and reduce parenting stress (Moreland et al., 2016). Improving the parent–child relationship through an appropriate method of parenting is a potentially promising approach for managing parenting stress.

The concept of “child-friendly family” has recently gained more attention in research and parenting practice (Chu et al., 2024). A child-friendly family refers to a familial environment characterized by close emotional connections, strong social support, and a focus on children’s overall well-being, allowing them to grow up in a happy, loving, and understanding atmosphere (UNICEF, 2018). Fostering a child-friendly family environment promotes a trusting parent–child relationship. In this approach, parents establish reasonable boundaries and consequences, encourage open communication and provide their children with understanding and acceptance. By adopting child-friendly parenting, parents can also develop positive character traits in themselves, such as patience, kindness, empathy, joy, and gentleness. They learn to handle meltdowns with composure, reject spanking as an effective form of discipline, resist victimhood in parenthood, and maintain safe and respectful family relationships. It has been reported that child-friendly parenting can inhibit problematic behavior in children (Pinquart, 2017) and that better child behavior is associated with lower parenting stress (Davis and Neece, 2017).

Family resilience as a mediator

Family resilience is a social protective factor that gives entire families and individual family members the ability to recover from adversity stronger and more resourceful (Sixbey, 2005). It contains family relationship-enhancing components, including effective communication, problem-solving strategies, and access to social and economic resources (Walsh, 2002). High resilience families exhibit better parent–child relationships, less vulnerability to challenges, and a greater ability to provide a secure environment to all family members (Herbell et al., 2020). Parents with higher family resilience are more likely to have a better psychological status (Aivalioti and Pezirkianidis, 2020) whereas parenting stress has been found to be negatively correlated with family resilience (Silva et al., 2021).

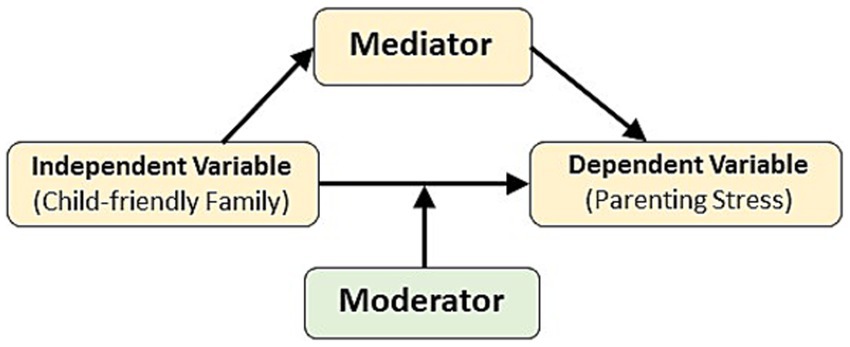

In this context, family resilience appears to act as a mediator. As shown in Figure 1, a mediator is a variable that lies on the causal pathway between an independent variable (child-friendly family) and a dependent variable (parenting stress) (Morrow et al., 2022). That is if “family resilience” is a mediator, it will correlate with both “child-friendly family” and “parenting stress,” as well as mediating the effect of “child-friendly family” on “parenting stress.” Thus, the hypothesis (H1) is that family resilience mediates the causal relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress.

Figure 1. Relationship between mediator, moderator, independent variable (child-friendly family), and dependent variable (parenting stress).

H1: Family resilience is a mediator of the effect of child-friendly family on reducing parenting stress.

Family resilience as a moderator

Instead of being a mediator, family resilience could be a moderator of the relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress. A moderator can modify the relationship between the independent variable (child-friendly family) and the dependent variable (parenting stress) (Figure 1) (Morrow et al., 2022). It does not lie on the causal pathway but interacts with the independent variable in a way that influences the outcome (Baron and Kenny, 1986). That is if “family resilience” is a moderator, it can affect the strength or direction of the effect of “child-friendly family” on “parenting stress.”

Previous studies have investigated the moderating effect of family resilience on children’s behavior. The findings indicate that family resilience has a negative moderating effect on negative parenting and adolescents’ problematic behaviors (Zhuo et al., 2022). Because family resilience has been reported to be a moderator of the relationship between negative parenting and adolescents’ problematic behaviors, and the problematic behaviors of children have been found to correlated with parenting stress, we posit the hypothesis:

H2: Family resilience is a moderator of the effect of child-friendly family on reducing parenting stress.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study was conducted with 316 parents. Inclusion criteria for this study encompassed parents who provided care for their children for a minimum of 14 h per week. Participants were required to be biological parents of children aged 0 to 18 years. Exclusion criteria included parents who were not the primary caregivers or who were unable to communicate effectively in the survey language, as well as those who had a significant mental health diagnosis that could impede their ability to provide accurate responses regarding their parenting experiences.

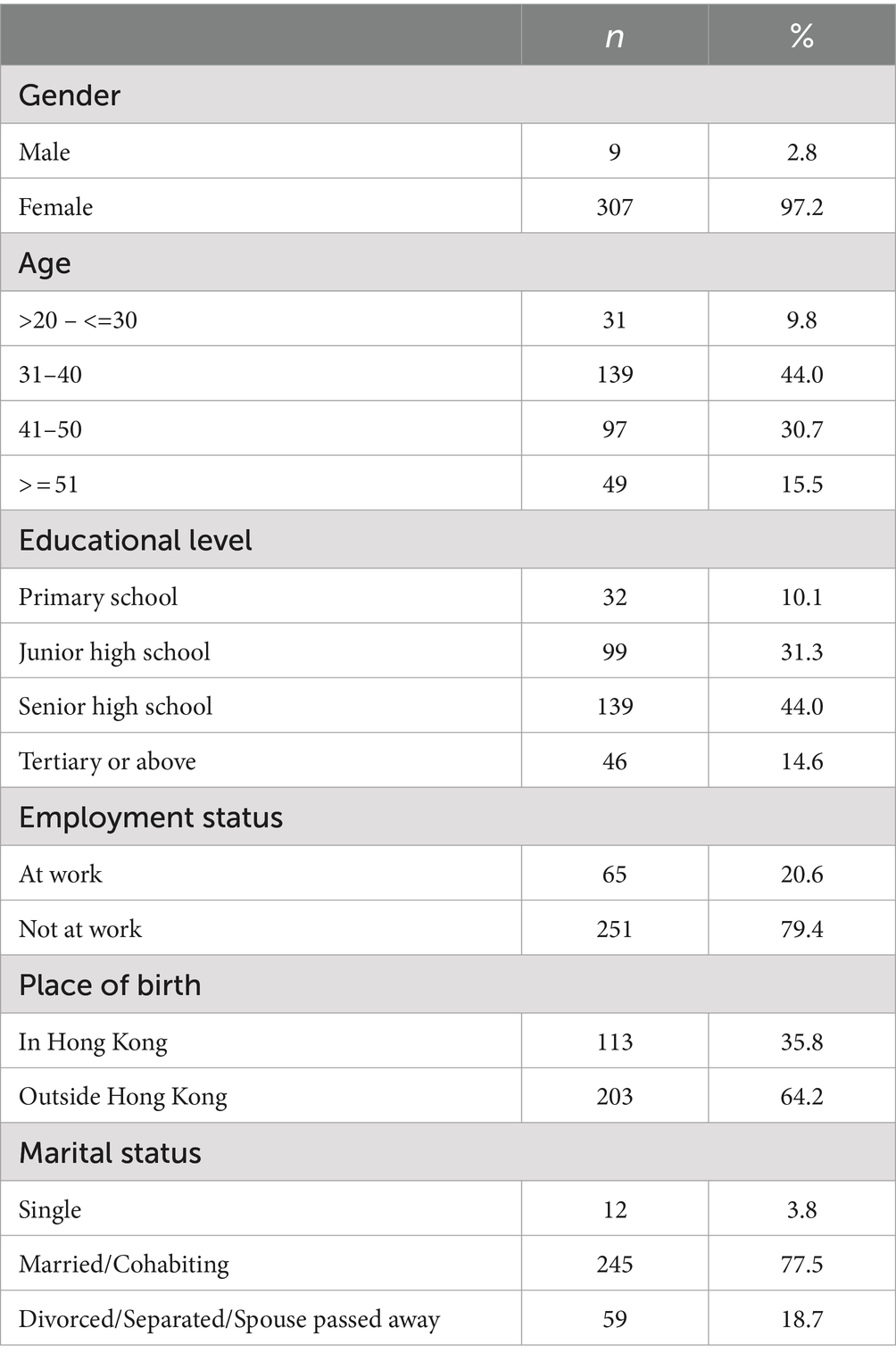

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of the participants were female (97.2%). Nearly three quarters of the participants were in either the 31–40 (44.0%) or 41–50 (30.7%) age group. Regarding educational level, most of the participants had received high school or tertiary education (89.9%). Most of the participants had no salaried job (79.4%). Slightly more than three quarters of the participants were married or cohabitating (77.5%). The highly diversified backgrounds of the participants provided a representative sample for this study and reduced potential biases due to the influence of socioeconomic background.

Procedures

The data were collected in 2019 from a nonprofit organization that has provided integrated family and community services in Hong Kong for more than 30 years. The registered social workers of the organization recruited parents who provided care to their children for at least 14 h per week to participate in the study. Before interviewing the potential participants, the social workers explained the study to them and obtained their informed consent. All the participants took part on a voluntary basis. The participants were asked to provide their demographic characteristics and complete three paper-and-pencil questionnaires: the Parenting Stress Index–Short Form (PSI; Rivas et al., 2021), the Family Resilience Assessment scale (FRAS; Chu et al., 2022), and the Inventory of the Child-Friendly Family (ICF; Chan and Chen, 2019).

Measures

Parenting stress index–short form

The PSI is a commonly used measure of parenting stress in clinical and research contexts (Rivas et al., 2021). It contains 36 items with three subscales—parental distress, parent–child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child. Each of the 36 items in the PSI is measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), with a total score ranging from 36 to 180. A higher total PSI score represents a lower level of parenting stress. Abidin (1995) reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.91 for PSI total score.

Family resilience assessment scale

The FRAS has been widely used to determine family resilience in various contexts (Gardiner et al., 2019). A validated Chinese version of the FRAS (Chu et al., 2022) was adopted in this study. The Chinese FRAS contains 42 items with five subscales: ability to make meaning of adversity, family communication and problem-solving, maintaining a positive outlook, family spirituality, and utilizing social and economic resources. Each item is measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A higher total FRAS score represents a higher level of family resilience. The Chinese FRAS demonstrated adequate concurrent validity and internal consistency (α = 0.724–0.963).

Inventory of the child-friendly family

The ICF was developed to guide parents and other stakeholders to build a child-friendly family (Chan, 2008). It was validated in a Chinese student population (Chan and Chen, 2019) and contains 18 items with two subscales: psychological support and positive discipline strategies, and care and protection. The ICF was originally designed to gain responses from children or adolescents. In the current study, we measured the child friendliness level of a family on the basis of the parents’ perspectives. Therefore, we modified the measurement items in the ICF by swapping the subject and object in the items. For example, the item “My parents satisfy my basic needs” was changed to “I satisfy my child’s basic needs.” In the ICF, each item is measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A higher total score of the ICF indicates that the family is more child friendly. The Cronbach’s alphas values of the two subscales of “psychological support and positive discipline strategies” and “care and protection” in the currency study were 0.766 and 0.824, respectively. The internal consistency level is acceptable because the values of Cronbach’s alphas are equal to or greater than 0.7 (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011).

Data analysis

Structural equation model (SEM) analysis was applied to investigate the relationship between child-friendly family, parenting stress, and family resilience, as well as the mediating role of family resilience between child-friendly family and parenting stress. The SEM analysis was conducted using the AMOS 26 software, along with fit indices calculation. The model fit was determined by various fit indices, including goodness-of-fit statistic (GFI), normed-fit index (NFI), root mean square residual (RMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The recommended cut-off for a good model fit is GFI > = 0.90, NFI > 0.90, RMR < 0.08, and RMSEA <0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Multiple regression analysis was applied to examine the moderation effect of family resilience on parenting stress regulation by child-friendly family. The analysis was conducted using the SPSS 26 software.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

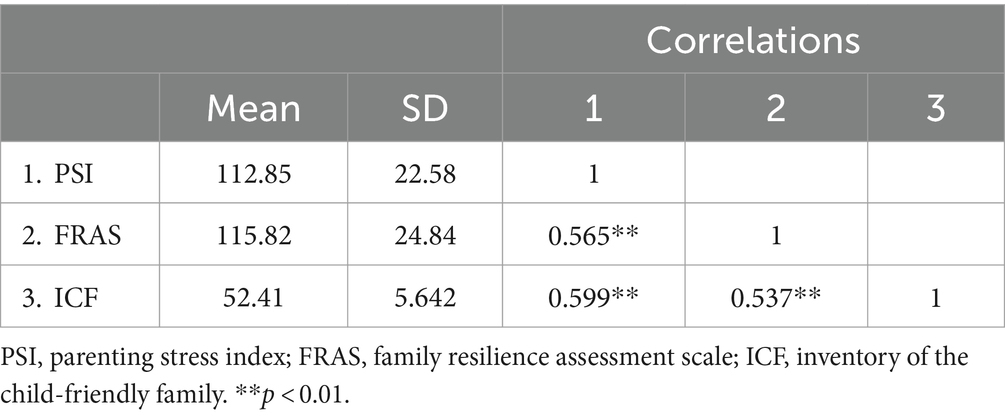

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients for PSI, FRAS, and ICF. PSI was positively correlated with FRAS (0.565, p < 0.01) and ICF (0.599, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher levels of parenting stress were associated with lower levels of family resilience and lower levels of child friendliness in a family. FRAS was positively correlated with ICF (0.537, p < 0.01), indicating that family resilience was positively associated with child-friendly family.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between the results of PSI, FRAS, and ICF.

Family resilience as a mediator between child-friendly family and parenting stress

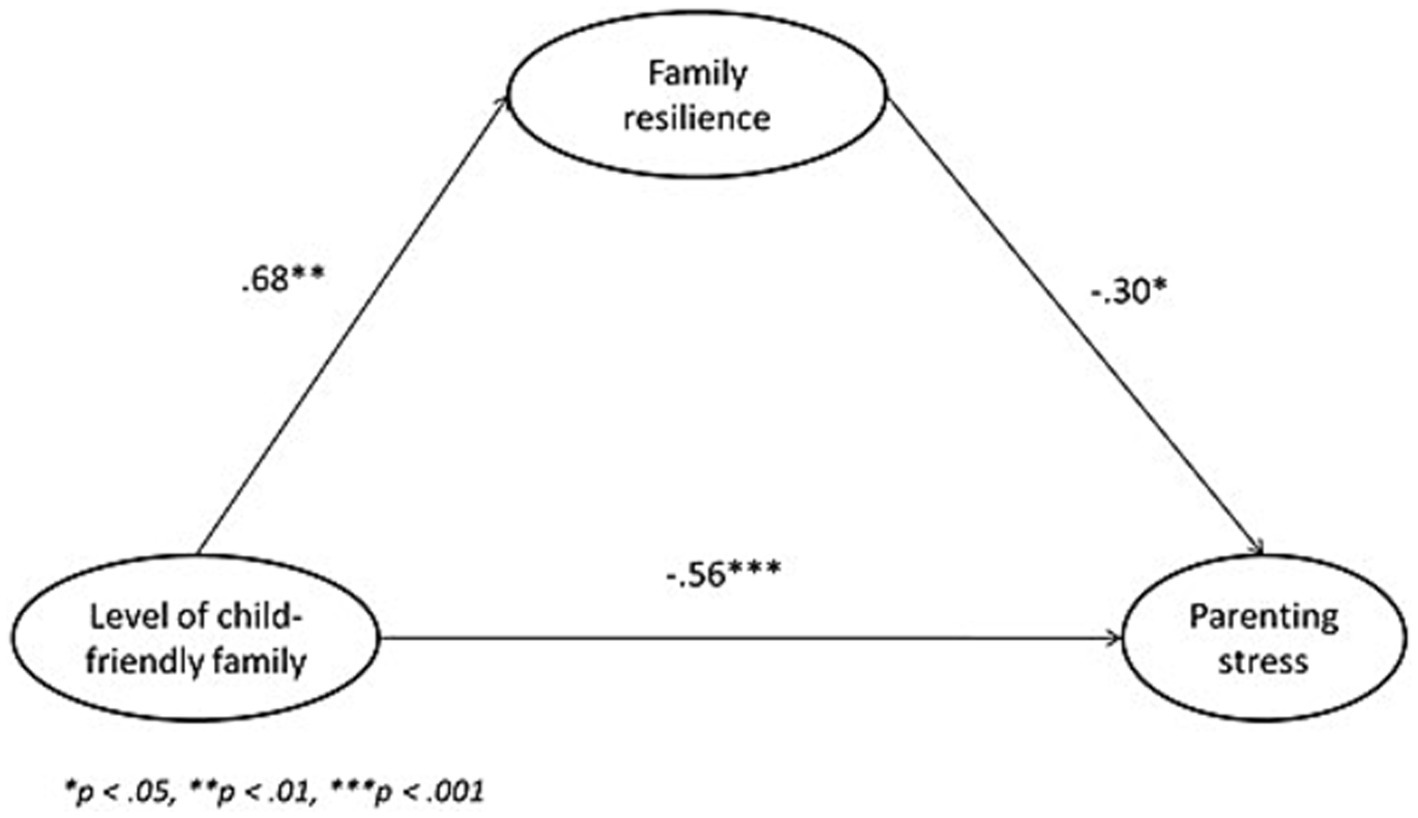

The structural equation model of the three variables—child-friendly family, family resilience, and parenting stress—is presented in Figure 2. In this model, all the path coefficients were significant, χ2 = 98.157, df = 41, and the fit indices were satisfactory (GFI = 0.949, NFI = 0.925, RMR = 0.014 and RMSEA = 0.053).

Figure 2. The mediation model of the effect of family resilience on child-friendly family and parenting stress.

Child-friendly family demonstrated a negative correlation with parenting stress (path coefficient = −0.56, p < 0.001). The negative path coefficient indicated that a higher level of child friendliness in a family leads to a lower level of parenting stress. Moreover, child-friendly family demonstrated a positive correlation with family resilience (path coefficient = 0.68, p < 0.01), while family resilience demonstrated a negative correlation with parenting stress (path coefficient = −0.30, p < 0.05). The results suggested that a higher level of child friendliness in a family brings about a higher level of family resilience, which in turn leads to a lower level of parenting stress.

The SEM model supported the existence of direct relationships between child-friendly family, family resilience, and parenting stress. It also indicated that family resilience was a mediator between child-friendly family and parenting stress, supporting hypothesis H1. The mediation effect ratio was calculated as follows:

The standardized indirect effect value of child-friendly family→family resilience→parenting stress was 0.68 x − 0.30 = −0.204. The standardized total effect value of child-friendly family on parenting stress was (−0.56) + (−0.204) = −0.764. On the basis of the two values, the mediation effect ratio was calculated as 0.204/0.764*100% = 26.70%. The mediation effect ratio showed that the mediation effect from family resilience contributed to over one quarter of the total effect of child-friendly family on parenting stress.

Moderation effect of family resilience on child-friendly family and parenting stress

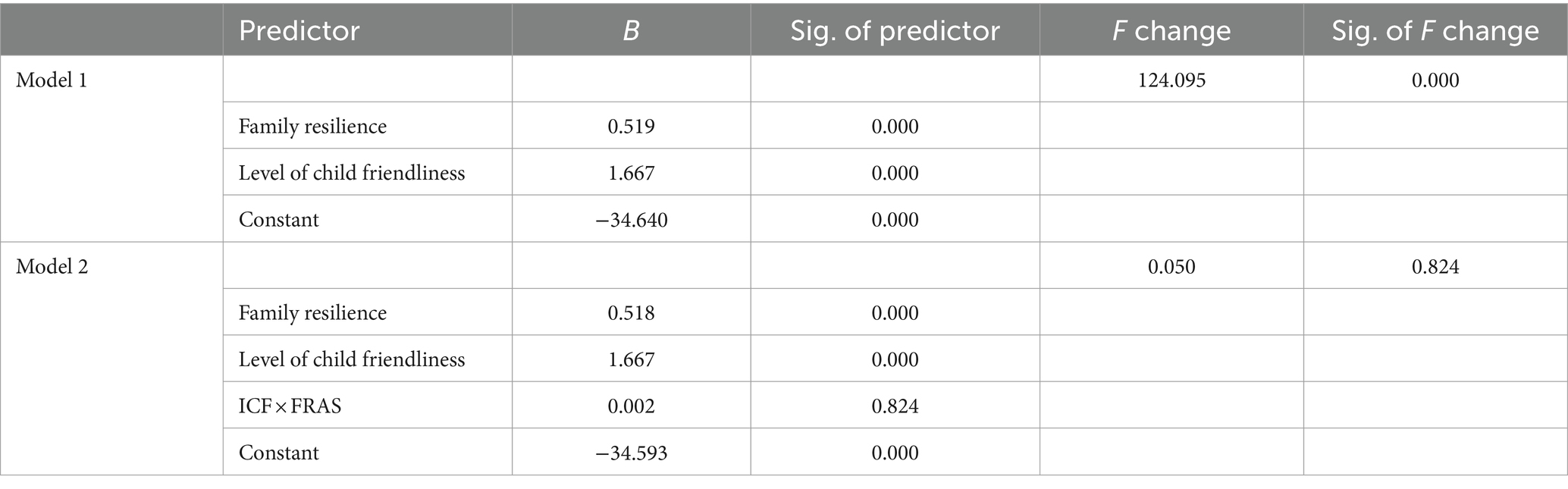

Multiple regression analysis was applied to examine the moderation effect of family resilience on child-friendly family and parenting stress. There were two models in this analysis, which are presented in Table 3. In model 1, family resilience and child-friendly family were significant predictors of parenting stress (p < 0.001), which was consistent with the findings of the SEM model. In model 2, an interaction term of child-friendly family and family resilience (ICF × FRAS) was added to the list of independent variables. After adding the interaction term (ICF × FRAS), family resilience and child-friendly family remained significant predictors of parenting stress (p < 0.001). However, the interaction term was not significant in the model. The F-change in model 2 was 0.50 (p = 0.824), which implied that the change in R-square was not significant. The results showed that there was no moderation effect of family resilience on the relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress and thus hypothesis H2 was rejected.

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis for the effect of family resilience on the relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress.

Discussion

In this study, we found out that child-friendly family is negatively correlated with parenting stress. It is also found that family resilience acts as a mediator, but not a moderator, among the relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress.

Relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress

Our findings indicated that child-friendly family demonstrated a negative correlation with parenting stress as shown in Figure 2 (path coefficient = −0.56, p < 0.001), suggesting a lower level of child friendliness in a family associates with a higher level of parenting stress. It is consistent with the other findings that indicates a poor parent–child relationship is commonly associated with negative parenting, such as the use of physical coercion, verbal hostility, and punitive action. Children from families with negative parenting are more frequently associated with problematic behaviors, such as agitation. In the face of problematic behaviors, stressful parents tend to increase their use of negative parenting. However, rather than improving children’s behavior, the entire family get trapped in a vicious circle of deteriorating parent–child relationships and intensifying parenting stress (Bauch et al., 2022; Schittek et al., 2023). The results of this study indicate the importance of promoting child-friendliness in the family to reduce maternal parenting stress.

Family resilience acts as a mediator

This study identified family resilience as a mediator between child-friendly family and parenting stress. A higher level of child friendliness in a family increases family resilience, which in turn reduces parenting stress. The mediation effect ratio was 26.70%, indicating that the mediation effect from family resilience contributed to over one quarter of the total effect of child-friendly family on parenting stress. This is consistent with Walsh’s family resilience theory (Walsh, 2002) that indicates the correlation between family resilience and parenting stress. The research findings of the current study have also confirmed the findings of the previous studies on the relationship between family resilience and parenting stress. According to the study of Kim et al., 2020, family resilience is negatively associated with maternal parenting stress that parents with high levels of family resilience had 15–18% lower probability for parenting stress. Studies on military parents revealed that improvement in key family resilience processes is predictive of an improvement in parents’ mental health, including a reduction in the distress and stress of parenting (Saltzman et al., 2016). Moreover, family resilience stabilizes the emotions of parents. Previous studies conducted among 437 parents provided evidence that emotionally distressed parents have a more negative perception of their children (Laufer and Bitton, 2023). On the contrary, parents who are free from emotional distress may have a better perception of their children and evaluate their behavior in a more positive way.

Family resilience is not a moderator

According to our results, family resilience is not a moderator in the relationship between child-friendly family and parenting stress. This implies that the direct impact of child-friendly family on parenting stress is stable, and the strength and direction of the relationship would not be affected by family resilience. However, previous studies which collected responses from teenagers found that family resilience has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between negative parenting and problematic behaviors (Sun et al., 2015). The difference in results may suggest that children and parents have different views on the same family issue.

Implications

Recognizing the role of the child-friendly family in enhancing family resilience and reducing parenting stress in the Chinese community is a particularly important finding. In traditional Chinese culture, filial piety is a virtue. Absolute obedience to and respect for parents is perceived to be mandatory. Conventionally, Chinese parents think they have “ownership” and “control” of their children (Cao and Wang, 2020). Studies have revealed that many Chinese parents do not regard using threatening or humiliating methods to control children as inappropriate and do not understand that such methods are harmful to the parent–child relationship (Li, 2019; Smith, 2016). Our findings, however, revealed that promoting the child-friendly family is beneficial to Chinese families. The adoption of child-friendly parenting among Chinese family not only does no harm to the filial piety-oriented tradition but also effectively enhances family resilience and reduces parenting stress.

Further investigation of other potential mediating and moderating factors between child-friendly family and parenting stress will provide a better understanding of how the child-friendly family enhances family resilience and reduces parenting stress. In the future, society will continue to develop at an unprecedented pace. People will need to adapt to new and unexpected changes frequently, thus increasing parenting stress. Promoting the child-friendly family is especially important in empowering individuals, as well as their families, to become more adaptable to changes through higher family resilience and lower parenting stress.

Limitations and future research

The results in the current study were based on a survey conducted in Hong Kong. To generalize the results more broadly, further research is needed. In addition, the significance of the research model in the current study depends on the reliability of self-reports. To minimize response bias, all participants had a clear understanding of the nature of the study from experienced social workers, and we used diverse participants. A pretest was also conducted before the actual survey to ensure the quality of the study. While the current study included both mothers and fathers, the sample was predominantly consisting of mothers. It is a common phenomenon of having more mothers than fathers participate in parenting studies (Davison et al., 2016). However, this unequal representation may limit the ability to make strong claims about the broader population of parents. Similarly, uneven employment status distribution among participate may also limit the generalization of the results. Further study should aim to obtain a more balanced sample with comparable proportion of mothers and fathers, and different employment status. In addition, the absence of confounding variables in our research model may limit the generalizability of our findings. Further research could benefit from incorporating relevant confounding variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interactions. In the current study, we used parents as our target respondents. However, some previous studies have used children as target respondents to learn about parenting or family issues. Further research is recommended to investigate why and how parents and children perceive the same parenting or family issue differently.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Education University of Hong Kong. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. JT: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. AT: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HY: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MS: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Dean’s Research Fund of the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences (Project No. FLASS/DRF/IRS-3) and the Department of Social Sciences and Policy Studies, The Education University of Hong Kong. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress index: Professional manual. 3rd Edn. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Adams, E. L., Smith, D., Caccavale, L. J., and Bean, M. K. (2021). Parents are stressed! Patterns of parent stress across COVID-19. Front. Psych. 12:626456. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626456

Aivalioti, I., and Pezirkianidis, C. (2020). The role of family resilience on parental well-being and resilience levels. Psychology 11, 1705–1728. doi: 10.4236/psych.2020.1111108

Aviles, A. I., Betar, S. K., Cline, S. M., Tian, Z., Jacobvitz, D. B., and Nicholson, J. S. (2024). Parenting young children during COVID-19: parenting stress trajectories, parental mental health, and child problem behaviors. J. Fam. Psychol. 38, 296–308. doi: 10.1037/fam0001181

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bauch, J., Hefti, S., Oeltjen, L., Pérez, T., Swenson, C. C., Fürstenau, U., et al. (2022). Multisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect: parental stress and parental mental health as predictors of change in child neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 126:105489. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105489

Bernier, A., Marquis-Brideau, C., Dusablon, C., Lemelin, J. P., and Sirois, M. S. (2022). From negative emotionality to aggressive behavior: maternal and paternal parenting stress as intervening factors. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 50, 477–487. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00874-1

Burgdorf, V., Szabó, M., and Abbott, M. J. (2019). The effect of mindfulness interventions for parents on parenting stress and youth psychological outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 10:1336. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01336

Cao, Y., and Wang, P. (2020). Looking at Chinese parent-teenager conflict talks from the perspective of the rapport management theory. J. Lang. Cult. 1, 7–16.

Chan, K. L. (2008). Study on child-friendly families: Immunity from domestic violence. Hong Kong: Department of Social Work & Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong.

Chan, K. L., and Chen, Q. (2019). The development of the inventory of the child-friendly family. Violence Vict. 34, 312–328. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00015

Chavez Arana, C., Catroppa, C., Yáñez-Téllez, G., Prieto-Corona, B., de León, M. A., García, A., et al. (2020). A parenting program to reduce disruptive behavior in Hispanic children with acquired brain injury: a randomized controlled trial conducted in Mexico. Dev. Neurorehabil. 23, 218–230. doi: 10.1080/17518423.2019.1645224

Chu, M., Fang, Z., Mao, L., Ma, H., Lee, C. Y., and Chiang, Y. C. (2024). Creating a child-friendly social environment for fewer conduct problems and more prosocial behaviors among children: a LASSO regression approach. Acta Psychol. 244:104200. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104200

Chu, A. M. Y., Tsang, J. T. Y., Tiwari, A., Yuk, H., and So, M. K. P. (2022). Measuring family resilience of Chinese family caregivers: psychometric evaluation of the family resilience assessment scale. Fam. Relat. 71, 130–146. doi: 10.1111/fare.12601

Davis, A. L., and Neece, C. L. (2017). An examination of specific child behavior problems as predictors of parenting stress among families of children with pervasive developmental disorders. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 10, 163–177. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2016.1276988

Davison, K. K., Gicevic, S., Aftosmes-Tobio, A., Ganter, C., Simon, C. L., Newlan, S., et al. (2016). Fathers' representation in observational studies on parenting and childhood obesity: a systematic review and content analysis. Am. J. Public Health 106, e14–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303391

Gardiner, E., Masse, L. C., and Iarocci, G. (2019). A psychometric study of the family resilience assessment scale among families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 17:45. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1117-x

Golfenshtein, N., Srulovici, E., and Deatrick, J. A. (2016). Interventions for reducing parenting stress in families with pediatric conditions: an integrative review. J. Fam. Nurs. 22, 460–492. doi: 10.1177/1074840716676083

Herbell, K., Breitenstein, S. M., Melnyk, B. M., and Guo, J. (2020). Family resilience and flourishment: well-being among children with mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders. Res. Nurs. Health 43, 465–477. doi: 10.1002/nur.22066

Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Kim, I., Dababnah, S., and Lee, J. (2020). The influence of race and ethnicity on the relationship between family resilience and parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 50, 650–658. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04269-6

Laufer, A., and Bitton, M. S. (2023). Parents' perceptions of Children's behavioral difficulties and the parent-child interaction during the COVID-19 lockdown. J. Fam. Issues 44, 725–744. doi: 10.1177/0192513X211054460

Li, X. (2019). Communication between Chinese parents and children: apology should be given from parents for invading children’s privacy. In Paper presented at the 4th international conference on humanities science and society development

Minkin, R., and Horowitz, J. M. (2023). Parenting in America today. Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/01/24/parenting-acknowledgments/ (Accessed April 26, 2024).

Mohammadkhani Orouji, F. (2021). Defining the concept of parenting stress in psychology. Int. J. Advanced Stud. Human. Soc. Sci. 10, 142–145. doi: 10.22034/ijashss.2021.278039.1046

Moreland, A. D., Felton, J. W., Hanson, R. F., Jackson, C., and Dumas, J. E. (2016). The relation between parenting stress, locus of control and child outcomes: predictors of change in a parenting intervention. J. Child Fam. Stud. 25, 2046–2054. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0370-4

Morrow, E. L., Duff, M. C., and Mayberry, L. S. (2022). Mediators, moderators, and covariates: matching analysis approach for improved precision in cognitive-communication rehabilitation research. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 65, 4159–4171. doi: 10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00551

Nichols, M. P., and Schwartz, R. C. (2004). Family therapy: Concepts and methods (6th ed.). London, UK: Pearson.

Pinquart, M. (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 53, 873–932. doi: 10.1037/dev0000295

Rivas, G. R., Arruabarrena, I., and de Paúl, J. (2021). Parenting stress index-short form: psychometric properties of the Spanish version in mothers of children aged 0 to 8 years. Psychosoc. Interv. 30, 27–34. doi: 10.5093/pi2020a14

Robinson, M., and Neece, C. L. (2015). Marital satisfaction, parental stress, and child behavior problems among parents of young children with developmental delays. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 8, 23–46. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2014.994247

Saltzman, W. R., Lester, P., Milburn, N., Woodward, K., and Stein, J. (2016). Pathways of risk and resilience: impact of a family resilience program on active-duty military parents. Fam. Process 55, 633–646. doi: 10.1111/famp.12238

Schittek, A., Roskam, I., and Mikolajczak, M. (2023). Parental burnout and borderline personality stand out to predict child maltreatment. Sci. Rep. 13:12153. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39310-3

Shi, D., Xu, Y., and Chu, L. (2024). The association between parents phubbing and prosocial behavior among Chinese preschool children: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 15:1338055. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1338055

Silva, Í. C. P., Cunha, K. C., Ramos, E. M. L. S., Pontes, F. A. R., and Silva, S. S. C. (2021). Family resilience and parenting stress in poor families. Estud. Psicol. 38:e190116. doi: 10.1590/1982-0275202138e190116

Sixbey, M. T. (2005). Development of the family resilience assessment scale to identify family resilience constructs. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Florida, Gainesville

Smith, L. S. (2016). Family-based therapy for parent-child reunification. J. Clin. Psychol. 72, 498–512. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22259

Sun, W., Li, D., Zhang, W., Bao, Z., and Wang, Y. (2015). Family material hardship and Chinese adolescents' problem behaviors: a moderated mediation analysis. PLoS One 10:e0128024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128024

UNICEF. (2018). Child-friendly parenting: Parenting schools for improving parenting skills also in Montenegro. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/montenegro/en/stories/child-friendly-parenting (Accessed April 26, 2024).

van Grieken, A., Horrevorts, E. M. B., Mieloo, C. L., Bannink, R., Bouwmeester-Landweer, M. B. R., Hafkamp-de Groen, E., et al. (2019). A controlled trial in community pediatrics to empower parents who are at risk for parenting stress: the supportive parenting intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:4508. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224508

Walsh, F. (2002). A family resilience framework: innovative practice applications. Fam. Relat. 51, 130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00130.x

Wang, D., Xie, R., Ding, W., Yuan, Z., Kayani, S., and Li, W. (2023). Bidirectional longitudinal relationships between parents' marital satisfaction, parenting stress, and self-compassion in China. Fam. Process 62, 835–850. doi: 10.1111/famp.12785

Zhao, J., Fan, Y., Liu, Z., Lin, C., and Zhang, L. (2023). Parenting stress and Chinese preschoolers' approaches to learning: a moderated mediation model of authoritative parenting and household residency. Front. Psychol. 14:1216683. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1216683

Keywords: child-friendly family, parenting stress, family resilience, mediating effect, moderating effect, parent–child relationship, structural equation modeling

Citation: Chu AMY, Tsang JTY, Tiwari A, Yuk H and So MKP (2024) Child-friendly family reduces parenting stress in Chinese families: the mediating role of family resilience. Front. Psychol. 15:1430005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1430005

Edited by:

Keerti Singh, The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, BarbadosReviewed by:

Jacqueline Benn, The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, BarbadosRita Kirton, The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados

Keo Forde-St.Hill, Ministry of Health and Wellness Barbados, Barbados

Copyright © 2024 Chu, Tsang, Tiwari, Yuk and So. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amanda Man Ying Chu, YW1hbmRhY2h1QGVkdWhrLmhr

Amanda Man Ying Chu

Amanda Man Ying Chu Jenny Tsun Yee Tsang

Jenny Tsun Yee Tsang Agnes Tiwari3

Agnes Tiwari3