95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 23 January 2025

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1419968

Objective: The objective of this study was to explain the relationship between therapeutic alliance and the changes observed in the parents’ psychological symptomatology after participation in the Egokitzen program, analyzing the mediating role of emotion regulation.

Methods: The study involved 117 divorced parents and 40 therapists.

Results: It has been observed that the early development and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance influence the parents’ psychological symptomatology after the intervention, through emotion regulation.

Conclusion: The study reinforce the role of the therapeutic alliance as a determining factor in the success of group interventions. This effect has turned out to be indirect through emotion regulation, highlighting the importance of emotional management.

Nowadays, destructive divorce is considered a complex, stressful, and emotionally very intense process (Amato and Hohmann-Marriott, 2007; Bodenmann et al., 2007), with repercussions in the mental health of the people who face it (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2018; Sbarra, 2015; Stack and Scourfield, 2015; Zulkarnain and Korenman, 2019). Among the consequences of this process, the literature has emphasized its impact at an emotional level as well as psychological symptomatology (Braver et al., 2016; Sandler et al., 2020), especially of a depressive type (Stack and Scourfield, 2015; Zulkarnain and Korenman, 2019).

Given the significant impact of destructive divorce on mental health, over the years, many group intervention programs have emerged that address emotion regulation and the associated symptomatology to facilitate the process of adaption of the people involved in this process (Malcore et al., 2010; Vélez et al., 2012). The objectives of these preventive programs include: (a) generating an environment of support that encourages the cathartic expression of the experiences concerning divorce, (b) providing the opportunity to solve problems and develop coping skills that help them manage their emotions, (c) relieving the stress arising from separation, and (d) developing the process of breaking the emotional bond with the ex-partner (Blaisure and Geasler, 2005; Geasler and Blaisure, 1999; Grych, 2005; Pedro-Carroll and Jones, 2005; Wolchik et al., 2000).

In recent years, studies at the international level on the effectiveness of these programs have proliferated (Becher et al., 2018; Braver et al., 2016; Jewell et al., 2017; McIntosh and Tan, 2017; Philip and O’Brien, 2017) although, in Spain, they remain scarce, with the sole exception of the Egokitzen program (Martínez-Pampliega et al., 2015, 2021). This interest has not been linked exclusively to preventive programs but also to psychotherapeutic intervention in general.

Despite progress in the verification of its effectiveness, research is still far from knowing its explanatory mechanisms. One of the factors linked to the effectiveness that has generated the most interest, regardless of the modality of intervention, is the therapeutic alliance (Friedlander et al., 2011; Horvath et al., 2011). This interest is attested by recent meta-analyses that have gathered extensive evidence of the influence of the therapeutic alliance in therapeutic success (Flückiger et al., 2018; Friedlander et al., 2018; Karver et al., 2018). Specifically, it is suggested that the therapeutic alliance explains between 7 and 21% of therapeutic change (Crits-Christoph et al., 2011; Flückiger et al., 2018; Karver et al., 2018; Wampold and Imel, 2015; Welmers-Van de Poll et al., 2018).

Therapeutic alliance refers to the collaborative relationship established between client and therapist (Bordin, 1979). This conceptualization has three main components: the link between therapist and client, mutual agreement on treatment goals, and mutual agreement on the tasks necessary to achieve the established goals (Bordin, 1979).

To date, many investigations have identified the relevance of establishing a strong alliance in the first sessions of psychological treatment (Wampold and Imel, 2015; Yoo et al., 2016) and of maintaining this alliance during the therapeutic process for its good prognosis (Glebova et al., 2011; Nissen-Lie et al., 2015; Wampold and Imel, 2015). Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance allows the therapeutic context to be experienced as a safe space in which an emotional connection is established between the client and the therapist (Escudero and Friedlander, 2017; Günther-Bel et al., 2021). In addition, a strong therapeutic alliance provides a feeling of connection with the therapeutic process and unity between the client and the therapy (Escudero and Friedlander, 2017; Friedlander et al., 2006b; Friedlander et al., 2006a). By achieving a context of trust and safety, the therapist will be able to confront the client to produce greater therapeutic change (Wampold and Imel, 2015).

The specific mechanisms through which the therapeutic alliance influences the effectiveness of interventions are not yet clear. In this sense, there is emerging evidence of associations between the therapeutic alliance and emotion regulation (Owens et al., 2013; Ronningstam, 2017; Whitehead et al., 2019). Higher levels of therapeutic alliance are associated with lower levels of difficulties in regulating emotions (Burt, 2013; Knerr et al., 2011; Owens et al., 2013; Whitehead et al., 2019), understanding emotion regulation as the process through which individuals modulate their emotions and modify their behavior to achieve goals, adapt to the context or promote their well-being (Gross, 2015). Therefore, the establishment of a strong therapeutic alliance could enhance their ability to regulate emotions.

In turn, the existing literature indicates that people’s emotion regulation is related to their symptomatology (Estévez Gutiérrez et al., 2014; Garnefski and Kraaij, 2006). That is, those with greater abilities to regulate emotions suffer lower levels of symptomatology (Gross and Feldman Barrett, 2011). Recently, Fisher et al. (2016) integrated both emotion regulation and the therapeutic alliance in their study and identified the important role of both variables as determinants of the therapeutic process and the prediction of the clients’ functioning.

The review of the literature has highlighted the need to understand the effectiveness of post-divorce intervention programs has been identified, with divorce being regarded as an emotionally very intense process. Understanding the effectiveness of post-divorce group interventions could benefit from deepening the therapeutic alliance and its impact on emotion regulation. To date, we know of no studies in this regard.

This study is proposed to analyze, through a longitudinal study, the development of the alliance throughout the implementation of a post-divorce intervention program, and to deepen the relationship of the alliance with parents’ emotion regulation and symptomatology. The program implemented will be the Egokitzen program, which, as indicated, is the only one that currently has studies of efficacy and effectiveness in Spain (Martínez-Pampliega et al., 2015, 2021). The data of the therapeutic alliance will be collected from the therapist’s perception, because it is more related to the outcome of the therapy than the client’s perception (Baldwin et al., 2007; Culina et al., 2023; Del Re et al., 2012).

Does the evolution of the therapeutic alliance in the course of therapy explain the direct change in emotion regulation and the indirect change in the parents’ psychological symptomatology?

The early development of the therapeutic alliance and its maintenance throughout the intervention will be associated with a reduction of the parents’ symptomatology, through its relationship with the parents’ increased emotion regulation.

The final sample was made up of 117 parents average aged 41.88 years (SD = 6.30). Of these, 36% were fathers and 64% mothers. These parents had on average 1.57 children (SD = 0.71) with an average age of 9.00 years (SD = 4.47). Forty-six percent of the participants had been divorced for more than 3 years, 13% from 2 to 3 years, 20% from 1 to 2 years, 9% from 6 months to 1 year, 10% from 2 to 6 months, and 2% less than 2 months. With regard to the level of education, 35% reported having primary studies, 34% high school or vocational training, 11% a middle career, 17% a higher career, and 3% a master’s degree or Ph.D.

The parents participated in 34 intervention groups supervised by two therapists. This research involved 40 therapists. The average age of the pairs of therapists was 43.43 years (SD = 8.88), and their professional experience was 16.84 years (SD = 5.72). Thirty-six percent of the pairs of therapists were made up of one man and one woman, 59% of the pairs were two women, and 5% of the pairs of therapists were made up of two men.

The Egokitzen post-divorce intervention program (Martínez-Pampliega et al., 2015, 2021), developed from a systemic approach to family functioning, was implemented. It is aimed at minimizing the impact of interparental conflict and building the resilience of the participants and their children. It consists of 10 sessions of 90 min (plus a previous framing session), implemented on a weekly basis, and structured around divorce and its impact, interparental conflict, and parenting. Special emphasis is placed on the emotional impact of the breakup, helping the participants to better manage their emotions. The sessions are designed to actively engage the participants through role-playing, debates, and group activities.

Emotion regulation was measured through the Spanish adaptation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer, 2004) of Hervás and Jódar (2008). This scale examines the difficulties that can appear in the process of emotion regulation and is composed of 25 five-point Likert-type items ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), grouped into five dimensions: Non-Acceptance, Lack of Objectives, Impulsivity, Lack of Strategies, and Lack of Clarity. The internal consistency of the global scale was 0.95 at pre- and posttreatment. Cronbach’s alpha index was adequate in all the dimensions both at pre- and posttreatment (Non-acceptance: 0.87 and 0.93; Lack of clear objectives: 0.90 and 0.84; Impulsivity: 0.84 and 0.78; Lack of strategies: 0.91 and 0.89; Lack of Clarity: 0.71 and 0.67, respectively).

Psychological symptomatology was measured with the adaptation and validation in Spanish of the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90; Derogatis et al., 1973) of González de Rivera et al. (2002). The scale has 44 Likert-like items rated from 1 (nothing or not at all) to 4 (very much or extremely), with a global score contemplating Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, and Somatization. The Cronbach alpha in this study was 0.96 at the pre- and post-treatment.

Therapeutic alliance was measured through the System for Observing Family Therapy Alliances (SOFTA-s: Alvarez et al., 2020). It consists of 12 Likert-type items, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) grouped into four dimensions: Engaging in the therapeutic process, Emotional Connection with the therapist, Safety within the therapeutic system, and Sense of Sharing the purpose in the family. The questionnaire is completed via the therapists’ perception of the therapeutic alliance with the group. The reliability of the scale in the third session was 0.65, in the sixth session, it was 0.76, and in the ninth session, it was 0.84. So, the overall mean of the scale’s reliability was 0.75.

This longitudinal study was developed at 12 family visitation centers nationwide. We contacted 1,538 people to ask them if they were interested in participating in the intervention program, of whom 428 reported being interested and were summoned to a personal interview. This personal interview was attended by 360 people, who were informed about the program and who signed the informed consent. However, 107 could not meet the conditions of participation and be included in the experimental group (due to working hours, shift work, family conciliation, etc.). Finally, 117 parents completed the questionnaires on the variables of this study. They are divorced individuals users of family visitation centers.

The 40 participating therapists were formed by the members of the research team in both the evaluation and implementation of the intervention program. Each intervention group was led by two professionals, with at least one being a psychologist. The average of participants in the groups was 3.47.

Regarding data collection, to measure therapeutic change, the participants completed the DERS and SCL-90 instruments individually before the intervention group began and again at the end. The therapists, meanwhile, completed the Therapeutic Partnership Questionnaire (SOFTA-s) at the end of sessions 3, 6, and 9. The literature has shown the need to collect therapeutic alliance measurements at various times throughout the treatment in order to explain the outcome of an intervention (Crits-Christoph et al., 2011).

Participation in the investigation was voluntary and participants were ensured about the anonymity of the responses to the questionnaires. Participants were also informed of the possibility of dropping out of the investigation if they wished to do so. The investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Deusto (ETK-7/16–17).

The hypothesis was tested using growth curve analysis in a structural equation (SEM) framework with Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 2012) with the maximum likelihood estimator. Following the indications of Wang and Wang (2012), we began testing the growth model of the therapeutic alliance. In this sense, growth curve analyses allow SEM to be applied to longitudinal data analysis with repeated measures for the same subjects over time. As the therapeutic alliance was measured at three moments (i.e., in the third, sixth, and ninth sessions), two models were compared based on the possible slopes (the maximum degree of the polynomial cannot exceed the number of time points – 1 = 3–1 = 2): the linear slope model and the quadratic slope model. In both cases, to facilitate interpretation, the first measure (i.e., the third session) was set to zero as the centering point. In this way, we compared whether the therapeutic alliance had a linear or curved evolution from the beginning to the end of the intervention. At the same time, the intercept was modeled, fixing the first collected value (third session) to facilitate interpretation. Therefore, the intercept can be understood as the initial level of the therapeutic alliance.

After analyzing the growth model of the therapeutic alliance, we tested the complete model, which included the intercept and the slope of the therapeutic alliance as independent variables, changes in emotion regulation difficulties as a mediator, and changes in symptomatology as the dependent variable. For this purpose, the changes were computed as differential variables in which the pre-intervention value was subtracted from the post-intervention value to represent the changes over the course of the program. In addition, gender, age, and intervention group were included as control variables in the model.

To assess the level of fit of the model, the following goodness-of-fit indicators were considered: non-significant chi-square (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) greater than 0.90, and Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) below 0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

First, we calculated the descriptive statistics of the observed variables of the study shown in Table 1. Secondly, the models were tested according to the hypothesis, starting by analyzing the evolution of the alliance throughout the intervention sessions.

The results of the hypothesized quadratic model led to estimation warnings that indicated problems in the specification of the model. Therefore, the quadratic function was considered inappropriate for modeling the growth curve of the therapeutic alliance (Wang and Wang, 2012). Based on this, the model was tested with the linear slope, which showed a good fit to the data, (χ2[1] = 1.50, p = 0.221, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.055, SRMR = 0.132), so it was established as a growth model of therapeutic alliance. This model indicated that both the mean (M = 4.24, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001) and the variance (σ = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) of the intercept were significant, yielding significant differences in the initial levels of therapeutic alliance among participants. Also, the mean (M = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = 0.004) and variance (σ = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = 0.006) of the linear slope were significant. We therefore note that the therapeutic alliance tended to increase in a linear and non-quadratic way throughout the intervention process, and that the participants differed significantly in the increase of alliance across the program sessions.

From the growth model of therapeutic alliance, we tested the final model, including the change in the difficulties of emotion regulation as a mediator, the change in psychological symptomatology as a dependent variable, and the control variables. This final model showed a good fit to the data (χ2[45] = 58.33, p = 0.087, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.050, SRMR = 0.070). The correlations between the model variables are shown in Table 2.

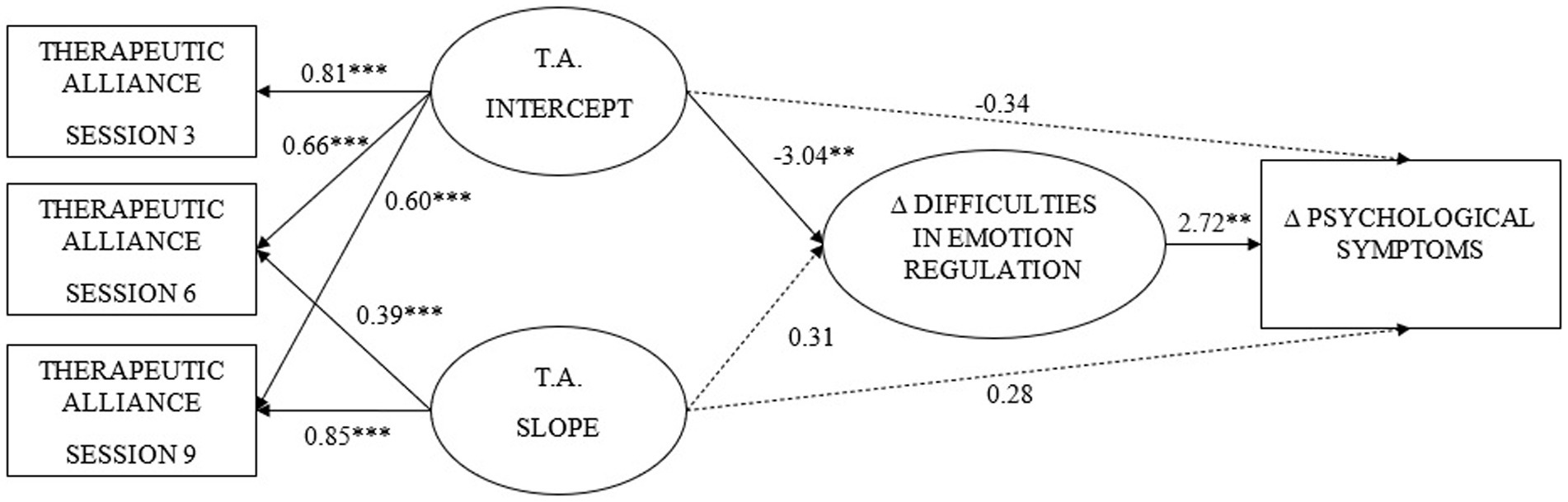

As shown in Figure 1, the results of the final model indicated that the intercept of therapeutic alliance was significantly and negatively related to the increase in emotion regulation difficulties, but the slope of the therapeutic alliance showed a nonsignificant relationship with the changes in emotion regulation difficulties. Therefore, higher levels of therapeutic alliance, and not its increase across the sessions, were related to the decrease in emotion regulation difficulties from pre- to postintervention.

Figure 1. Standardized growth model coefficients. TA, Therapeutic alliance. Dashed lines represent non-significant coefficients. **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

With regard to changes in symptomatology, we noted that the therapeutic alliance showed no significant direct relationship either with the intercept or with the slope. However, changes in the difficulty of emotion regulation showed a significant and positive relationship with changes in symptomatology. Thus, those who experienced a reduction in their emotion regulation difficulties tended to reduce their symptomatology.

Finally, the indirect effect of the intercept of the therapeutic alliance on symptomatology was analyzed, finding that it was significant (−10.07, SE = 5.14, p = 0.050), such that higher levels of therapeutic alliance as of the first sessions were related to a greater reduction of symptomatology due to the effect on emotion regulation difficulties. This model explained 18% of the variance of emotion regulation difficulties and 15% of psychological symptomatology.

The objective of this study was to explain the relationship between therapeutic alliance and the changes observed in the parents’ psychological symptomatology after participation in the Egokitzen program, analyzing the mediating role of emotion regulation. The results support the hypothesis: it has been observed that the early development and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance influence the parents’ psychological symptomatology after the intervention, through emotion regulation.

With regard to the research question focused on the role of the therapeutic alliance, we can highlight two aspects: (1) we found that a strong construction of the therapeutic alliance at the beginning of the intervention, together with its maintenance throughout the treatment, explains the change in the parents’ symptomatology; (2) this impact on symptomatology occurred through the observed change in the parents’ emotion regulation. These two points will be addressed in more detail below.

On the one hand, the findings of this study confirm the importance of building a strong therapeutic alliance in the first sessions of treatment and maintaining it during the process to achieve therapeutic change. These results are relevant because, in this area of research, there is some controversy about the best trajectory of the therapeutic alliance to achieve therapeutic success. In this regard, the study provides additional data to the evidence provided by Nissen-Lie et al. (2015) or Yoo et al. (2016), among others, compared to other studies (Chu et al., 2014; Escudero et al., 2022; Schmidt et al., 2023) that, on the contrary, found support for the increase of the therapeutic alliance throughout the intervention as a more favorable condition to obtain better therapeutic results. Although in clinical practice, it is a challenge for therapists to maintain a stable therapeutic alliance during the intervention and avoid breakdowns in it, the results obtained highlight the special care that therapists must exert. Finding strategies to achieve this may have to be the goal. In this sense, the studies of Aron (2006) and Larsson et al. (2018) directed attention toward meta-communication about disagreements and impasses in the therapeutic relationship, that is, how to take advantage of breakdowns in the therapeutic alliance and turn them into opportunities for the benefit of the therapeutic process.

On the other hand, our research has helped to clarify the mechanisms through which the therapeutic alliance can be related to the success of interventions, as measured in this study through the parents’ symptomatology. Specifically, we identified emotion regulation as a mediating variable. Although this variable had shown its relevance in other contexts (Fresco et al., 2013; Peña-Sarrionandia et al., 2015), no research had been developed till now that reflected its importance in preventive post-divorce intervention programs. These results seem to be consistent with the literature carried out in clinical context, which has emphasized the relationship between therapist and client as a corrective emotional experience (Alexander and French, 1946; Castonguay and Hill, 2012; Safran and Muran, 2000), allowing clients to acquire better management of their emotions throughout the intervention, and reducing the associated psychological symptomatology. Despite the promising results obtained, the specificity of the intervention in this study will require further research to analyze the role of emotion regulation in other therapeutic modalities.

In this sense, we emphasize the fact that this research has identified the relevance of the therapeutic alliance in a group context, a modality scarcely researched so far, identifying its role in the therapeutic success, as in other modalities (Baldwin et al., 2007; Del Re et al., 2012; Nissen-Lie et al., 2015). The results of the study allow us to affirm the importance of the therapists’ directing their efforts in the first sessions to achieve therapeutic engagement and working in collaboration with the members of the group to achieve the objectives, also in group interventions and even preventive interventions.

Finally, the study has provided support to those researchers who have emphasized the need to address the design, analyzing the therapeutic alliance process through different sessions, to better understand its relationship with the results of the therapeutic interventions (Sexton et al., 2004). In fact, it should be noted that this research, with three moments of measurement of the therapeutic alliance, has allowed us to explain a fairly acceptable percentage (15–18%) of therapeutic change (Crits-Christoph et al., 2011; Flückiger et al., 2018; Karver et al., 2018; Wampold and Imel, 2015; Welmers-Van de Poll et al., 2018).

However, this study has several limitations that suggest a cautious interpretation of the results. First, the therapist sample is small. While this is explained by the specificity of the context and the intervention model. A greater number would favor a greater generalization of the findings obtained. Another limitation of the study is the self-reported nature of the measures instead of observational measures, or, from the point of view of the design, the absence of relevant follow-up measures to understand causal relationships. In this sense, it would be important to collect data throughout more time periods, and longer periods, in order to know if the effect persists in the long term. It would also be relevant for future research, to consider additional variables such as the therapists’ characteristics (e.g., personality), aspects that have not yet been addressed in post-divorce group interventions or differences between divorced individuals (e. g., level of conflict).

In short, to our knowledge, this research is the first study that addresses the explanatory mechanisms of the therapeutic alliance in a group context with post-divorce interventions. The study has helped to reinforce the role of the therapeutic alliance as a determining factor in the success of group interventions, because of its relationship with the participants’ symptomatology. This effect has turned out to be indirect through emotion regulation, highlighting the importance of managing emotional processes for therapeutic success, also in post-divorce group interventions. The generalization of this result to other modalities and therapeutic objectives remains to be analyzed.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Deusto ETK-7/16-17. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

IA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AM-P: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad [grant RETOS 2015: PSI2015-67983-R], and by the Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [grant n ̊ exp. 492, programa 002; 9/12/ 2016] and by Gobierno Vasco [grant Programa Predoctoral de Formación de Personal Investigador no Doctor PRE_2017_1_0020]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alexander, F., and French, T. M. (1946). Psychoanalytic therapy: Principles and application. Oxford, UK: Ronald Press.

Alvarez, I., Herrero, M., Martínez-Pampliega, A., and Escudero, V. (2020). Measuring perceptions of the therapeutic alliance in individual, family, and group therapy from a systemic perspective: structural validity of the SOFTA-s. Fam. Process 60, 302–315. doi: 10.1111/famp.12565

Amato, P. R., and Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2007). A comparison of high- and low-distress marriages that end in divorce. J. Marriage Fam. 69, 621–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00396.x

Aron, L. (2006). Analytic impasse and the third: clinical implications of intersubjectivity theory. Int. J. Psychoanal. 87, 349–368. doi: 10.1516/15EL-284Y-7Y26-DHRK

Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., and Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75, 842–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842

Becher, E. H., Mcguire, J. K., McCann, E. M., Powell, S., Cronin, S. E., and Deenanath, V. (2018). Extension-based divorce education: a quasi-experimental design study of the parents forever program. J. Divorce Remarriage. 59, 633–652. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2018.1466256

Blaisure, K. R., and Geasler, M. J. (2005). Results of a survey of court-connected parent education programs in U.S. counties. Fam. Court. Rev. 34, 23–40. doi: 10.1111/j.174-1617.1996.tb00398.x

Bodenmann, G., Charvoz, L., Bradbury, T. N., Bertoni, A., Iafrate, R., Giuliani, C., et al. (2007). The role of stress in divorce: a three-nation retrospective study. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 24, 707–728. doi: 10.1177/0265407507081456

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherap. Theory Res. Prac. 16, 252–260. doi: 10.1037/h0085885

Braver, S. L., Sandler, I. N., Cohen Hita, L., and Wheeler, L. A. (2016). A randomized comparative effectiveness trial of two court-connected programs for high-conflict families. Fam. Court. Rev. 54, 349–363. doi: 10.1111/fcre.12225

Burt, S. (2013). Therapist attachment, emotion regulation and working alliance within psychotherapy for personality disorder. University of East Anglia. Available at:https://search.proquest.com/docview/1783895160?pq-origsite=primo

Castonguay, L., and Hill, C. (2012). “Corrective experiences in psychotherapy: an introduction” in Transformation in psychotherapy: Corrective experiences across cognitive behavioral, humanistic, and psychodynamic approaches. eds. L. G. Castonguay and C. E. Hill (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 3–9.

Chu, B. C., Skriner, L. C., and Zandberg, L. J. (2014). Trajectory and predictors of alliance in cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 43, 721–734. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.785358

Crits-Christoph, P., Gibbons, M. B. C., Hamilton, J., Ring-Kurtz, S., and Gallop, R. (2011). The dependability of alliance assessments: the alliance-outcome correlation is larger than you might think. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 79, 267–278. doi: 10.1037/a0023668

Culina, I., Fiscalini, E., Martin-Soelch, C., and Kramer, U. (2023). The first session matters: therapist responsiveness and the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Clinic. Psychol. Psychother. 30, 131–140. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2783

Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., and Wampold, B. E. (2012). Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance–outcome relationship: a restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07.002

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., and Covi, L. (1973). The SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 9, 13–28.

Escudero, V., and Friedlander, M. L. (2017). Therapeutic alliances with families. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Escudero, V., Friedlander, M., Kivlighan, D., Orlowski, E., and Abascal, A. (2022). Mapping the Progress of the process: Codevelopment of the therapeutic Alliance with maltreated adolescents. J. Couns. Psychol. 69, 656–666. doi: 10.1037/cou0000621

Estévez Gutiérrez, A., Herrero Fernández, D., Sarabia Gonzalvo, I., and Jáuregui Bilbao, P. (2014). El papel mediador de la regulación emocional entre el juego patológico, uso abusivo de internet y videojuegos y la sintomatología disfuncional en jóvenes y adolescentes [the mediator role of emotion regulation in pathological gambling, abusive use of internet and videogames and dysfunctional symptomatology in youth and adolescents]. Adicciones 26:282. doi: 10.20882/adicciones.26

Fisher, H., Atzil-Slonim, D., Bar-Kalifa, E., Rafaeli, E., and Peri, T. (2016). Emotional experience and alliance contribute to therapeutic change in psychodynamic therapy. Psychotherapy 53, 105–116. doi: 10.1037/pst0000041

Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., and Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy 55, 316–340. doi: 10.1037/pst0000172

Fresco, D. M., Mennin, D. S., Heimberg, R. G., and Ritter, M. (2013). Emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 20, 282–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.02.001

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., and Heatherington, L. (2006b). Therapeutic alliance with couples and families: An empirically informed guide to practice. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Heatherington, L., and Diamond, G. M. (2011). Alliance in couple and family therapy. Psychotherapy 48, 25–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022060

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Horvath, A. O., Heatherington, L., Cabero, A., and Martens, M. P. (2006a). System for observing family therapy alliances: a tool for research and practice. J. Couns. Psychol. 53, 214–225. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.214

Friedlander, M. L., Escudero, V., Welmers-van de Poll, M. J., and Heatherington, L. (2018). Meta-analysis of the alliance–outcome relation in couple and family therapy. Psychotherapy 55, 356–371. doi: 10.1037/pst0000161

Garnefski, N., and Kraaij, V. (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: a comparative study of five specific samples. Personal. Individ. Differ. 40, 1659–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009

Geasler, M. J., and Blaisure, K. R. (1999). 1998 Nationwide survey of court-connected divorce education programs. Fam. Court. Rev. 37, 36–63. doi: 10.1111/j.174-1617.1999.tb00527.x

Glebova, T., Bartle-Haring, S., Gangamma, R., Knerr, M., Delaney, R. O., Meyer, K., et al. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and progress in couple therapy: multiple perspectives. J. Fam. Ther. 33, 42–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2010.00503.x

González de Rivera, J. L., De Las Cuevas, C., Rodríguez, M., and Rodríguez, F. (2002). The symptom checklist 90 SCL-90-R. Spanish adaptation. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Gratz, K. L., and Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 26, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Gross, J. J., and Feldman Barrett, L. (2011). Emotion generation and emotion regulation: one or two depends on your point of view. Emot. Rev. 3, 8–16. doi: 10.1177/1754073910380974

Grych, J. H. (2005). Interparental conflict as a risk factor for child maladjustment: implications for the development of prevention programs. Fam. Court. Rev. 43, 97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1617.2005.00010.x

Günther-Bel, C., Vilaregut, A., and Linares, J. (2021). Towards an understanding of the within-system therapeutic Alliance with high-conflict divorced parents: a change process research. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 43, 329–342. doi: 10.1007/s10591-021-09593-7

Hervás, G., and Jódar, R. (2008). Adaptación al castellano de la Escala de Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional [Adaptation to Spanish of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale]. Clínica y Salud 19, 139–156.

Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., and Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 48, 9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jewell, J., Schmittel, M., McCobin, A., Hupp, S., and Pomerantz, A. (2017). The children first program: the effectiveness of a parent education program for divorcing parents. J. Divorce Remarriage. 58, 16–28. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2016.1257903

Karver, M. S., De Nadai, A. S., Monahan, M., and Shirk, S. R. (2018). Meta-analysis of the prospective relation between alliance and outcome in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 55, 341–355. doi: 10.1037/pst0000176

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2018). Marriage, divorce, and the immune system. Am. Psychol. 73, 1098–1108. doi: 10.1037/amp0000388

Knerr, M., Bartle-Haring, S., McDowell, T., Adkins, K., Delaney, R. O., Gangamma, R., et al. (2011). The impact of initial factors on therapeutic alliance in individual and couples therapy. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 37, 182–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00176.x

Larsson, M. H., Falkenström, F., Andersson, G., and Holmqvist, R. (2018). Alliance ruptures and repairs in psychotherapy in primary care. Psychother. Res. 28, 123–136. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1174345

Malcore, S. A., Windell, J., Seyuin, M., and Hill, E. (2010). Predictors of continued conflict after divorce or separation: evidence from a high-conflict group treatment program. J. Divorce Remarriage 51, 50–64. doi: 10.1080/10502550903423297

Martínez-Pampliega, A., Aguado, V., Corral, S., Cormenzana, S., Merino, L., and Iriarte, L. (2015). Protecting children after a divorce: efficacy of Egokitzen—an intervention program for parents on children’s adjustment. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 3782–3792. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0186-7

Martínez-Pampliega, A., Herrero, M., Sanz, M., Corral, S., Cormenzana, S., Merino, L., et al. (2021). Is the Egokitzen post-divorce intervention program effective in the community context? Child Youth Serv. Rev. 129:106220. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106220

McIntosh, J. E., and Tan, E. S. (2017). Young children in divorce and separation: pilot study of a mediation-based co-parenting intervention. Fam. Court. Rev. 55, 329–344. doi: 10.1111/fcre.12291

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide. 7th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nissen-Lie, H. A., Havik, O. E., Høglend, P. A., Rønnestad, M. H., and Monsen, J. T. (2015). Patient and therapist perspectives on alliance development: therapists’ practice experiences as predictors. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 22, 317–327. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1891

Owens, K. A., Haddock, G., and Berry, K. (2013). The role of the therapeutic alliance in the regulation of emotion in psychosis: an attachment perspective. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 20, 523–530. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1793

Pedro-Carroll, J. L., and Jones, S. H. (2005). “A preventive play intervention to foster children’s resilience in the aftermath of divorce” in Empirically based play interventions for children. eds. L. A. Reddy, T. M. Files-Hall, and C. E. Schaefer. American Psychological Association, 51–75.

Peña-Sarrionandia, A., Mikolajczak, M., and Gross, J. J. (2015). Integrating emotion regulation and emotional intelligence traditions: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00160

Philip, G., and O’Brien, M. (2017). Are interventions supporting separated parents father inclusive? Insights and challenges from a review of programme implementation and impact. Child Fam. Soc. Work 22, 1114–1127. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12299

Ronningstam, E. (2017). Intersect between self-esteem and emotion regulation in narcissistic personality disorder - implications for alliance building and treatment. Borderline Personal Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 4:3. doi: 10.1186/s40479-017-0054-8

Safran, J. D., and Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance. A relational treatment guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Sandler, I., Wolchik, S., Mazza, G., Gunn, H., Tein, J. Y., Berkel, C., et al. (2020). Randomized effectiveness trial of the new beginnings program for divorced families with children and adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 49, 60–78. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1540008

Sbarra, D. A. (2015). Divorce and health. Psychosom. Med. 77, 227–236. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000168

Schmidt, V., Treml, J., Deller, J., and Kersting, A. (2023). The relationship between working Alliance and treatment outcome in an internet-based grief therapy for people bereaved by suicide. Cogn. Ther. Res. 47, 587–597. doi: 10.1007/s10608-023-10383-8

Sexton, T. L., Ridley, C. R., and Kleiner, A. J. (2004). Beyond common factors: multilevel-process models of therapeutic change in marriage and family therapy. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 30, 131–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01229.x

Stack, S., and Scourfield, J. (2015). Recency of divorce, depression, and suicide risk. J. Fam. Issues 36, 695–715. doi: 10.1177/0192513X13494824

Vélez, C., Wolchick, S. A., and Sandler, I. N. (2012). “Interventions to help parents and children through separation and divorce” in Encyclopedia on early childhood development. eds. R. E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, and R. D. Peters (Montreal, Quebec: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development).

Wampold, B. E., and Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate. 2nd Edn. New York: Routledge.

Wang, J., and Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Welmers-Van de Poll, M. J., Roest, J. J., van der Stouwe, T., van den Akker, A. L., Stams, G. J. J. M., Escudero, V., et al. (2018). Alliance and treatment outcome in family-involved treatment for youth problems: a three-level meta-analysis. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 21, 146–170. doi: 10.1007/s10567-017-0249-y

Whitehead, M., Jones, A., Bilms, J., Lavner, J., and Suveg, C. (2019). Child social and emotion functioning as predictors of therapeutic alliance in cognitive–behavioral therapy for anxiety. J. Clin. Psychol. 75, 7–20. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22633

Wolchik, S. A., West, S. G., Sandler, I. N., Tein, J.-Y., Coatsworth, D., Lengua, L., et al. (2000). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 843–856. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.843

Yoo, H., Bartle-Haring, S., and Gangamma, R. (2016). Predicting premature termination with alliance at sessions 1 and 3: an exploratory study. J. Fam. Ther. 38, 5–17. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.12031

Keywords: therapeutic alliance, emotion regulation, symptomatology, divorce, group

Citation: Alvarez I, Herrero M and Martínez-Pampliega A (2025) Does the therapeutic alliance process explain the results of the Egokitzen post-divorce intervention program? Front. Psychol. 15:1419968. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1419968

Received: 19 April 2024; Accepted: 02 December 2024;

Published: 23 January 2025.

Edited by:

Suzanne Bartle-Haring, The Ohio State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Klara Smith-Etxeberria, University of the Basque Country, SpainCopyright © 2025 Alvarez, Herrero and Martínez-Pampliega. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Irati Alvarez, aWFsdmFyZXpAYmFtLmV1cw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.