94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

STUDY PROTOCOL article

Front. Psychol., 31 July 2024

Sec. Health Psychology

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1400882

This article is part of the Research TopicHealth Promotion in the Universities and Other Educational SettingsView all 19 articles

Irene Messina*

Irene Messina* Tatiana Rossi

Tatiana Rossi Flavia Bonaiuto

Flavia Bonaiuto Gianluigi Granieri

Gianluigi Granieri Paola Cardinali

Paola Cardinali Irene Petruccelli

Irene Petruccelli Roberto Maniglio

Roberto Maniglio Claudio Loconsole

Claudio Loconsole Pietro Spataro

Pietro SpataroAcademic burnout is a condition characterized by exhaustion, cynicism, a distant attitude toward studying, and diminished self-efficacy in academic activities. Preliminary scientific findings indicate that interventions designed to alleviate work burnout also hold promise for mitigating academic burnout, however clear evidence based on randomized controlled trials is still missing. This research protocol describes a randomized controlled trial aimed at evaluating the efficacy of an online group psychological intervention to contrast academic burnout. Participants with high levels of burnout will be assigned to a psychological counseling group or a waiting list control group. The research comprises several phases: (T0) Screening, Recruitment, and Randomization; (T1) Baseline assessment (pre-intervention); (T2) Outcome Assessment (post-intervention); and (T3) Follow-up Assessment (3 months post-intervention). The primary outcomes include burnout symptoms, general wellbeing, and academic achievement. Additionally, secondary variables such as effort-reward imbalances, satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs, intrapersonal and interpersonal emotion regulation, coping strategies, and social support will be examined. The psychological intervention strategies will encompass psychoeducation, self-awareness enhancement, cognitive restructuring, and promotion of social support. This research protocol is an initial step toward evidence-based psychological interventions to treat academic burnout.

Burnout is a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment, traditionally attributed to chronic responses to occupational and interpersonal stress conditions at work (Freudenberger, 1974; Maslach, 1976). More recently, the concept of burnout has been extended to the educational context, where “academic burnout” is described as a condition characterized by exhaustion from studying, cynicism, distant attitude toward studying, and reduced self-efficacy in relation to academic activities (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2007). It is associated with a lower feeling of efficacy in tackling the course of studies (Rahmati, 2015), lengthening or interruption of the academic career (Madigan and Curran, 2021), as well as a higher incidence of psychological disorders (Deeb et al., 2018), substance abuse (Kadhum et al., 2022), suicidal ideation and suicide (Dyrbye et al., 2008).

The efficacy of psychological interventions to contrast work burnout has been largely demonstrated in several meta-analyses focused on general employees' categories (Maricutoiu et al., 2016; Ahola et al., 2017; Perski et al., 2017) and on more at-risk categories, such as health workers (Rahmati, 2015; Panagioti et al., 2017) and teachers (Iancu et al., 2018). Effective individual-centered interventions include awareness enhancing strategies - typically, self-monitoring of stress symptoms and psychoeducation on adaptive/maladaptive strategies to cope against stress—and arousal reductions strategies (for example, relaxation techniques and mindfulness meditation) (Le Blanc and Schaufeli, 2008). In more complex interventions, also strategies aimed at changing maladaptive cognitions have been successfully used (Le Blanc and Schaufeli, 2008; Bresó et al., 2011). Namely, negative cognitions concerning self-efficacy have been shown to play a key role, with high level of self-efficacy acting as a protective factor against burnout (Shoji et al., 2016).

To our knowledge, there is limited research on the efficacy of psychological interventions to treat academic burnout. Early scientific evidence suggests that psychological interventions to decrease work burnout are also promising for academic burnout. For instance, reduction of academic burnout scores has been documented after psychological counseling sessions to enhance self-awareness (Luo X., 2012; Luo Z. Y., 2012; Liu, 2013; Zhang et al., 2014; Guo, 2016; Shen, 2020), contrast maladaptive cognitions or “cognitive restructuring” (Ni and Wu, 2009; Xiong and Fang, 2017; Apriliya and Lianawati, 2023) or decrease stress related arousal (Ye et al., 2017; Wan, 2020).

In combination with individual-centered approaches, organizational approaches focused on enhancing social support may also be effective. Indeed, social support has both indirect (buffering) and direct effects in the relationship between stressors (e.g., academic demands) and students' burnout (Kim et al., 2018; Kusuma et al., 2022). Furthermore, strategies of interventions based on the provision of supportive relationships in the academic context could be useful to decrease students' burnout (Ezenwaji et al., 2019; Xu, 2019). Beyond specific strategies to enhance social support, the provision of psychological interventions in a group format could represent a natural source of social support (Biolcati et al., 2017; Brusadelli et al., 2020). Together with advantages in terms of social support provision, psychological interventions at the group level are the most suitable approaches for organizational settings. Indeed, group counseling is widely used in academic burnout interventions (Tang et al., 2021). More recently, early documentation of the efficacy of online group psychological counseling to treat academic burnout has been also provided (Eseadi, 2022; Apriliya and Lianawati, 2023).

In summary, early studies support the hypothesis that psychological interventions are useful to contrast academic burnout. Among others, interventions focused on self-awareness, cognitive restructuring, and social support are promising. Interestingly, there is also preliminary evidence that combining two or more strategies in integrated approaches could add value in terms of effectiveness of such interventions (Tang et al., 2021). However, the number of existing studies is still exiguous and available studies present relevant methodological limitations, above all the lack of adequate of control conditions (Tang et al., 2021). Moreover, the studies described above come almost exclusively from Asia and the adaptation to different cultural context cannot be taken for granted. Thus, more research is required in the direction of validating psychological interventions to treat academic burnout.

In the present research protocol, we propose a randomized controlled study designed to test the efficacy of an online group psychological intervention protocol to contrast academic burnout. We opted for Transactional Analysis (TA) as the theoretical background of this intervention (Berne, 1961; Vos and van Rijn, 2021). Even if TA has received limited attention by psychotherapy research, it is widely taught and practiced internationally within recognized academic and professional institutions (Vos and van Rijn, 2022), and it has a large history of application in organizational settings in Europe and United Kingdom (for organizational TA manuals see: Davidson and Mountain, 2016; Cannavale and Castagna, 2018; van Poelje and de Graaf, 2021). The main advantage of TA-based interventions for burnout lies in its intrinsic combination of individual and organizational approaches (Thunnissen and Timmermans, 2023), due to the simultaneous focus on human personality (focus on intra-personal processes) and social behavior (focus on interpersonal processes (Berne, 1961). This double focus is evident in the traditional group format of TA in its origins (Berne, 1958). Finally, TA treatments were one of the first models of psychological intervention that integrated cognitive-behavioral approaches with psychoanalytic concepts, developing a substantive new theory, as a strategy for integration (Vos and van Rijn, 2023). Thus, it is a flexible model, easily adaptable to the integration of different strategies of intervention, as in the psychological counseling program tested in the present research protocol.

The present study is a randomized clinical trial aimed at generating evidence in support of the effectiveness of an online group psychological counseling intervention in university students with high levels of academic burnout. To this aim, the study design entails the comparison between students that will be randomly assigned to two matched groups: (1) a psychological counseling group (PC, N = 65) or (2) a waiting list control group (WL, N = 65). We will test the effect of time (pre-PC vs. post-PC) in interaction with the effect of group (PC vs. WL) on the score obtained in several self-report outcome measures, including scores on burnout symptoms, general wellbeing, and academic achievement as primary outcomes. We hypothesize that PC, compared to WL, should provide evidence of the efficacy of psychological counseling to decrease burnout symptoms and improve general wellbeing and academic achievement.

Moreover, to acquire data on possible mediators or psychological change, we will also assess a large set of secondary outcome variables potentially related to academic burnout, including effort-reward imbalances, basic psychological needs of satisfaction/frustration, intrapersonal and interpersonal emotion regulation, coping strategies and social support. Such variables will be directly and/or indirectly addressed in the psychological counseling sessions (see Section “Intervention” and Table 1). We hypothesize that secondary outcomes variables may be affected by the psychological counseling intervention, mediating or moderating its effects on primary outcomes.

The research protocol was registered on ClinicalTrial.gov on January 2024 (protocol 9-FIN/RIC).

The study will be conducted at Mercatorum University, a private Italian online university. Due to the online nature of Mercatorum University, the psychological counseling interventions and the related research activities will be carried out online (in videoconference), in the context of the psychological counseling service of the university and using Google Meet links provided in the University Web Platform.

Assuming a medium effect size (Cohen's d = 0.50), we estimated with the G*Power3 software (Faul et al., 2007) that we need a sample size of 128 participants (i.e., two groups of 64 students) to achieve a power of 0.80 (α = 0.05). Thus, a total of 130 students will be recruited from bachelor's courses at Universitas Mercatorum. Participants are eligible for inclusion according with the following criteria: (a) age > 18 years; (b) clinical levels of academic burnout scores [one standard deviation above the mean MBI-SS total score reported in the validation study by Portoghese et al. (2018)]; (c) attendance of 1st or 2nd year of bachelor course at Universitas Mercatorum; and (d) sufficient knowledge of the Italian language. Additional exclusion criteria aimed at selecting a sufficiently homogeneous group of participants are: (a) previous university degree; (b) other psychiatric diagnoses; (c) other ongoing psychological or psychiatric treatments. Finally, we also excluded (d) attendance of 3rd year of bachelor course, to avoid participants drop-outs due to the course conclusion.

The MBI-SS (Schaufeli et al., 1996; Italian adaptation: Portoghese et al., 2018) is a 15-item self-report questionnaire composed of three subscales: Exhaustion (EX; item example “I feel used up at the end of a day at university”), Cynicism (CY; item example “I doubt the significance of my studies”), and Professional Efficacy (PE; item example “During class I feel confident that I am effective in getting things done”). All the items are scored by using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (=“never”) to 6 (=“always”). We will use the Italian version of MBI-SS from the study of Portoghese et al. (2018), in which reliability coefficients for each of the subscale scores were 0.86 for EX, 0.82 for CY and 0.77 for PE. The MBI-SS will be used to select students with high levels of academic burnout.

This form was developed to collect information about the demographic characteristics of the students participating in the study. The form contains a total of 10 questions regarding basic personal information (sex, age, previous experience of psychological counseling/psychotherapy, current, or previous psychological/psychiatric diagnoses), educational information (attended bachelor course, previous academic experience, previous academic degree, and parents' education), and economical status (current economic situation and economic situation in childhood).

The MBI-SS will be also used as primary outcome measure.

The PGWB is a self-report measure of intra-personal affective or emotional states, which captures a subjective perception of wellbeing referring to the last 4 weeks (original version: Dupuy, 1984; Italian short-form version: Grossi et al., 2006). It is composed by items assessing Anxiety, Depressed Mood, Positive Wellbeing, Self-Control, General Health, and Vitality (item example “How much energy, pep, or vitality did you have or feel during the past month?”). All the items are scored by using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (for example “Very full of energy–lots of pep”) to 6 (for example “No energy or pep at all–I feel drained, sapped”).

The academic achievements of the students participating to the study will be measured based on the self-reported number of passed exams and the average exam grades. Moreover, self-reported satisfaction in academic achievement will be also assessed with a 4-point Likert scale item ranging from 1 (=“not satisfied”) to 4 (=“completely satisfied”).

The BPNSFS is a self-report general measure of the satisfaction and frustration of the psychological needs in one's life (Italian adaptation: Costa et al., 2018; Cardella et al., 2020). It is composed of the following subscales: Autonomy Satisfaction (item example “I have a feeling of choice and freedom in what I do at work”), Competence Satisfaction (item example “I feel confident that I can do things well at work”), Relatedness Satisfaction (item example “I feel closely connected to other people who are important to me at work.”), Autonomy Frustration (item example “My daily activities at work feel like a continuous line of duties”), Competence Frustration (item example “I seriously doubt whether I can do things well at work ”), and Relatedness Frustration (item example “I feel that the relations I have at work are only superficial”). All 24 items are scored on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (=“completely disagree”) to 5 (=“completely agree”).

The ERI-SQ is a self-report measure to identify effort-reward imbalance in university students (Wege et al., 2017; Italian adaptation: Portoghese et al., 2019). It is composed of the following subscales: Effort (item example “I have constant time pressure due to a heavy study load”), Reward (item example “I receive the respect I deserve from my supervisors (teachers”), and Over-Commitment (item example “Student work rarely lets me go; it is still on my mind when I go to bed”). All the items are scored by using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (=“strongly disagree”) to 4 (=“strongly agree”).

The CERQ-18 is a self-report measure of cognitive emotion regulation strategies individuals may use after experiencing negative life events (Garnefski and Kraaij, 2006; Italian adaptation: Cerolini et al., 2022). It evaluates the habitual use of Self-Blame (item example “I feel that I am the one to blame for it”), Other-Blame (item example “I feel that others are to blame for it”), Rumination (item example “I often think about how I feel about what I have experienced”), Catastrophizing (item example “I often think that what I have experienced is much worse than what others have experienced”), Putting Into Perspective (item example: “think that other people go through much worse experiences”), Positive Refocusing (item example “I think of something nice instead of what has happened”), Positive Reappraisal (item example “I think I can learn something from the situation”), Acceptance (item example “I think that I have to accept that this has happened”), and Refocus on Planning (item example “I think about how I can best cope with the situation”). All 18 items are scored on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging 1 (=“almost never”) to 5 (=“almost always”).

The DIRE is a self-report measure of maladaptive interpersonal emotion regulation strategies that may relate to psychopathology (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2018; Italian adaptation: Messina et al., 2022). It is composed of the following subscales: Venting (item example “Raise your voice or criticize your friends to express how you feel”), Reassurance-Seeking [item example “Keep contacting (texting, calling, etc.) friends and loved ones”], Avoidance (item example “Avoid feeling or showing your distress”), and Acceptance (item example “Simply notice your feelings”). All 21 items are scored on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (=“very unlikely”) to 5 (=“very likely”).

The Brief-Cope is a self-report measure of different coping reactions (Carver et al., 1989; Italian adaptation Bongelli et al., 2022). It includes the following subscales: Problem-Focused Coping (item example “I've been trying to come up with a strategy about what to do”), Emotion-Focused Coping (item example “I've been getting emotional support from others”), and Avoidant Coping (item example “I've been using alcohol or other drugs to make myself feel better”). All 28 items are scored on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (=“I haven't been doing this at all”) to 4 (=“I've been doing this a lot”).

The MSPSS is a self-report measure of perceived emotional support (Zimet et al., 1988; Italian Adaptation Cipolletta et al., 2022). Perceived social emotional support is evaluated over three dimensions: Family (item example “My family really tries to help me”), Friends (item example “I can count on my friends when things go wrong”), and Significant Others (item example “I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me”), with each subscale containing four items. All the items are scored by using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (=“strongly disagree”) to 7 (=“strongly agree”).

Together with self-rated improvements, additional indicators of outcome will be considered. First, acceptance rate will be calculated by taking the total number of participants who accepted, agreed, and consented to participate in this study and dividing it by the number of participants who were invited to participate. Second, adherence rate will be calculated as the total number of participants who completed the intervention according to the study protocol divided by the number of participants who started the intervention. Third, dropout rate will be calculated as number of participants who withdrew from or did not continue the intervention divided by the number of participants who consented to participate on the study.

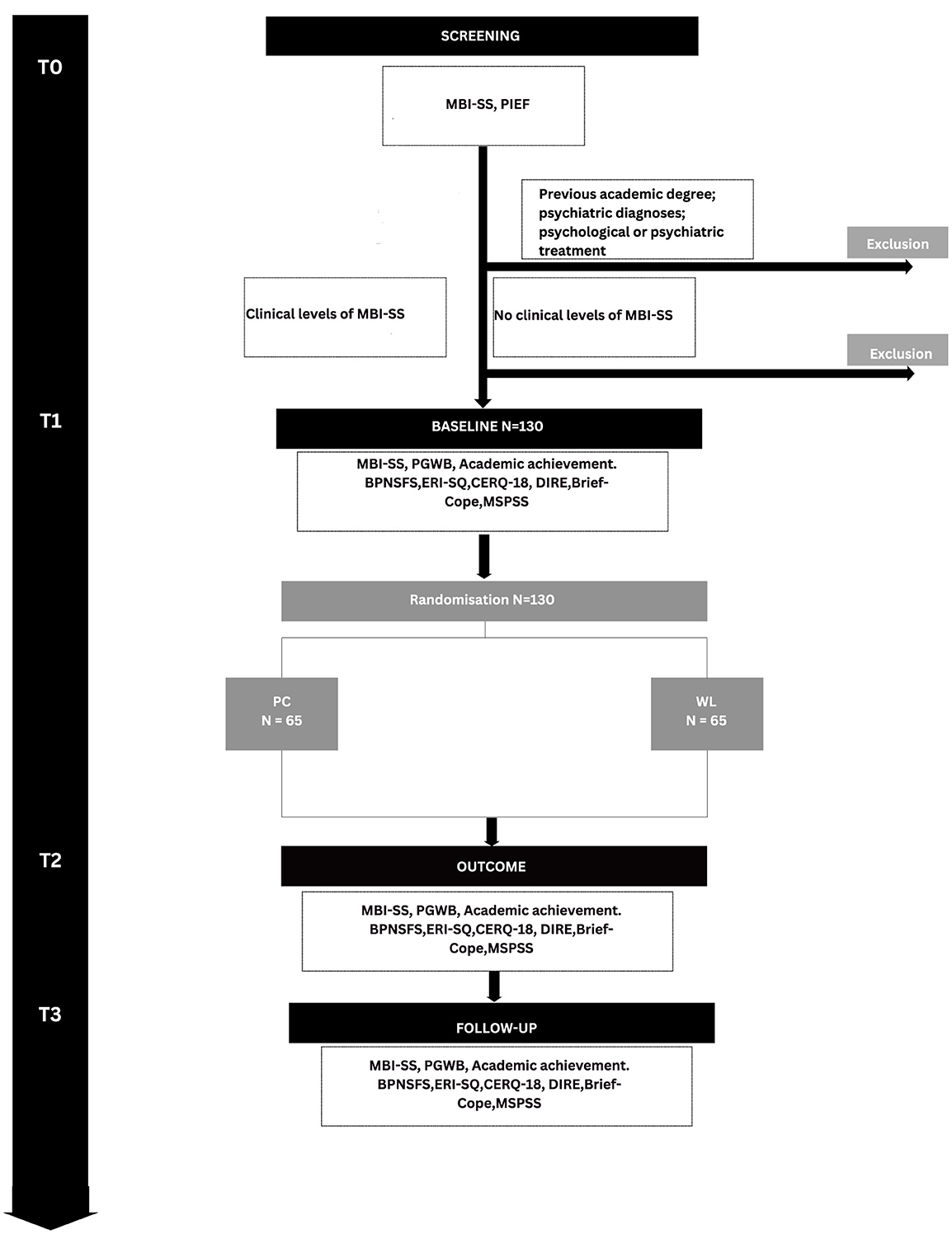

The study will entail the following phases: (T0) Screening, Recruitment and Randomization; (T1) Baseline assessment (pre-intervention); (T2) Outcome Assessment (post-intervention); and (T3) Follow-up Assessment (3 months after the intervention). A summary of study design procedures is showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study design and patient recruitment (N = projected numbers). MBI-SS, Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey; PIEF, Personal Information and Eligibility Form (PIEF); PGWB-S, Psychological General Well-Being index-short version; BPNSFS, Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale; ERI-SQ, Effort-Reward Imbalance student questionnaire; CERQ-18, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Short Version; DIRE, Difficulties in Interpersonal Emotion Regulation (DIRE); Brief-Cope, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced; MSPSS, The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

Potential participants will be invited electronically via email to students' listservs, on a weekly basis until target enrolment will be reached. In this e-mail, potential participants will receive written information on the screening aims and those who provide written consent with screening participation will fill out the PIEF and the MBI-SS. Eligible participants identified in the screening phase will be contacted by a researcher and invited to a brief assessment interview to further evaluate their eligibility based on a psychologist's rating, to give oral and written information about the clinical trial and obtain informed consent to the clinical training. Then, participants will be randomized to PC or WL groups by a colleague not involved in the study, using a computerized randomization generator. The research team will be blind to the randomized allocation.

Outcome variables will be assessed at T1, T2, and T3, using a Google Form. At each time, participants of the two groups will be required to fill in the eight self-report questionnaires described above (MBI-SS, PGWB-S, BPNSFS, ERI-SQ, CERQ-18, DIRE, Brief-Cope, and MSPSS). Baseline data (T1) will be collected after brief assessment interview (once informed written consent has been obtained by the participant). T2 data will be collected after the end of the last PC session. Finally, 3 months after the end of PC, participants will be contacted electronically via email and invited to fill in the Google Form to obtain T3 data.

The online group psychological counseling will be provided to small groups of maximum 10 participants. The intervention will consist of 6 weekly group sessions of 2 h each, based on Transactional Analysis model (Stewart and Joines, 1987; Cannavale and Castagna, 2018). Each session will be conducted by certified psychotherapists trained in Transactional Analysis and an observer co-conductor. In line with treatment goals, intervention strategies will include: (a) psychoeducation about academic-related stress, burnout, and effective strategies to contrast burnout; (b) interventions to promote self-awareness of personal reactions to academic-related stressful events, of the connection between different levels of such reactions (thoughts, emotion, bodily sensations, and behaviors), of psychological satisfaction/frustration needs, and of maladaptive habitual behaviors (e.g., learning style) which may influence academic burnout; (c) intervention to promote initial cognitive restructuring aimed at the identification of more helpful cognitive representations of academic context events (especially cognitive representations of self and others); (d) promotion of social support encouraging social sharing and adaptive social interaction in the group. See Table 1 for an overview of strategies, in-session activities, consistency with treatment goals, and the related TA concepts/techniques.

Descriptive statistics will be reported for participant recruitment, acceptance, adherence, and dropout rates. Baseline characteristics for each group will be reported to ensure group matching on these variables. To verify the reliability of the eight questionnaires, we will compute test-retest correlations between T1 and T2, and between T1 and T3 (using Pearson's r coefficients).

To assess the effects of PC on the outcome variables (MBI-SS, PGWB-S, and academic achievement), mixed model regressions will be utilized, by considering Time (T1, T2, and T3) and Group (PC vs. WL) as fixed factors and subjects as the random factor. This technique will allow us to test the interaction between Time and Group. Our expectation is that PC and WL should differ at T2 and T3, but not at T1, indicating that the PC group should achieve higher scores than the WL group after, but not before, the psychological counseling intervention.

A series of path analyses will be conducted to determine whether the measures obtained from the BPNSFS, ERI-SQ, CERQ-18, DIRE, Brief-Cope, and MSPSS questionnaires mediate the differences in the outcome variables between T1 and T2, and T1 and T3. For each analysis, the exogenous variables will be the outcome measures at T1, the mediators will be the scores in the subscales of the BPNSFS, ERI-SQ, CERQ-18, DIRE, Brief-Cope, and MSPSS questionnaires, and the endogenous variables will be the outcome measures at T1. Since each questionnaire involves multiple subscales, two separate models will be computed for each mediator. For example, for the BPNSFS questionnaire, we will test whether the Autonomy Satisfaction, Competence Satisfaction, Relatedness Satisfaction, Autonomy Frustration, Competence Frustration, and Relatedness Frustration subscales will mediate the associations between the T1 and T2 (or T1 and T3) outcome measures.

We will also calculate Reliable Change Index (RCI) and Clinically Significant Change (CSC) (Jacobson and Truax, 1991) for each patient, from pre- to post- treatment and at follow-up. The RCI is computed as a ratio in which the numerator represents the difference between each subject's pretest and post-test outcome scores, while the denominator represents the standard error of the difference between the two test scores. According to Jacobson and Truax (1991), RC indices larger than 1.96 indicate that a significant change has occurred. The CSC is represented by a patient's score moving from the “dysfunctional population” range into the “functional population.” For example, pre-treatment to post-treatment of at least 2 standard deviations from the original mean (Evans et al., 1998). Finally, we will provide grouped percentages (PC vs. WL) for those individuals who reliably improved or had a clinically significant change.

The study is based on substantial evidence that psychological interventions promoting self-awareness, cognitive restructuring, and social support are effective strategies to combat burnout. This provides a strong foundation for the research. The study applies these interventions to the specific case of academic burnout, a field that is promising but still lacks strong evidence from randomized controlled trials. In the present article, we described the research protocol of the first randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of an online group psychological intervention specifically designed for university students with high levels of burnout. Moreover, we gave attention to several methodological issues. In line with the empirically supported psychological treatments requirements (Chambless and Hollon, 1998), we propose a between-group design with adequate statistical power, and we clearly specified sample characteristics (defined by standard measures). We also identified a large range of possible primary and secondary outcomes, and we planned the implementation of statistical analyses suitable for the understanding of different levels of effects in the data that will be collected.

Beside such strengths, the research protocol has also few weaknesses. First, we planned a waiting list design without active control conditions, such as psychological placebo and/or another treatment control groups. We opted for a waiting list design because it is widely used in standard pragmatic trials (Purgato et al., 2015) and it presents relevant ethical advantages (it allows for the provision of care to all research participants). However, due to the lack of an active control condition, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying any possible effect of the intervention will be necessarily partial (Barkauskas et al., 2005; Hart et al., 2008). This could potentially limit the internal validity of the study. Second, according to empirically supported treatments movement (Chambless and Hollon, 1998), experiments must be conducted with treatment manuals. Even if we refer to existing Transactional Analysis manuals to design the psychological intervention, due to the novelty of the field of application a dedicated manual for academic burnout is still missing (but currently in progress). This could lead to inconsistencies in the delivery of the intervention, making it harder to replicate the study and understand which specific aspects of the intervention are most effective. Third, due to the sample size and the group format only an exiguous number of psychotherapists will conduct the interventions. We will control for the effect of the provider in statistical analysis, but our sample size will not allow a complete evaluation of “therapist effects” (Crits-Christoph and Mintz, 1991). The fact that only a small number of psychotherapists will conduct the interventions could introduce therapist effects, where the outcomes are influenced by the specific therapists' skills, styles, or personalities. While the study plans to control for the effect of the provider in statistical analysis, the small sample size may not allow for a complete evaluation of these effects. Finally, while the sample size of 130 participants may be sufficient for detecting large effects, it may not be large enough to detect smaller, yet still meaningful, effects. This could limit the statistical power of the study and the ability to generalize the findings to a larger population. Future studies should overcome such limitations.

In conclusion, while the study does have a few weaknesses, such as the lack of an active control condition, the absence of a dedicated manual for academic burnout, and the limited number of psychotherapists conducting the interventions, these limitations are acknowledged and provide avenues for future research to build upon this work. Overall, the strengths of this study make it a potentially significant contribution to the field. This would draw more attention to academic organizational politics and related supporting actions.

IM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. TR: Writing – original draft. FB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GG: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. PC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. IP: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CL: Writing – review & editing. PS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research received a grant from Mercatorum University (“Bandi competitivi di Ateneo”; grant number: 9-FIN/RIC).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahola, K., Toppinen-Tanner, S., and Seppänen, J. (2017). Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: systematic review and meta-analysis. Burnout Res. 4, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2017.02.001

Apriliya, P., and Lianawati, A. (2023). The effectiveness of cognitive restructuring techniques in group counseling services to reduce online learning burnout in college students. Indon. J. Educ. Counsel. 7, 111–121. doi: 10.30653/001.202371.245

Barkauskas, V. H., Lusk, S. L., and Eakin, B. L. (2005). Selecting control interventions for clinical outcome studies. West. J. Nurs. Res. 27, 346–363. doi: 10.1177/0193945904271446

Berne, E. (1958). Transactional analysis: a new and effective method of group therapy. Am. J. Psychother. 12, 735–743. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1958.12.4.735

Berne, E. (1961). Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy: A Systematic Individual and Social Psychiatry. Potomac, MD: Pickle Partners Publishing. doi: 10.1037/11495-000

Biolcati, R., Agostini, F., and Mancini, G. (2017). Analytical psychodrama with college students suffering from mental health problems: preliminary outcomes. Res. Psychother. 20:272. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2017.272

Bongelli, R., Fermani, A., Canestrari, C., Riccioni, I., Muzi, M., Bertolazzi, A., et al. (2022). Italian validation of the situational Brief Cope Scale (I-Brief Cope). PLoS ONE 17:e0278486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278486

Bresó, E., Schaufeli, W. B., and Salanova, M. (2011). Can a self-efficacy-based intervention decrease burnout, increase engagement, and enhance performance? A quasi-experimental study. Higher Educ. 61, 339–355. doi: 10.1007/s10734-010-9334-6

Brusadelli, E., Ferrari, L., Benetti, M., Bruzzese, S., Tonelli, G. M., and Gullo, S. (2020). Online Supportive Group as social intervention to face COVID lockdown. A qualitative study on psychotherapists, psychology trainees and students, and community people. Res. Psychother. 23:501. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2020.501

Cannavale, D., and Castagna, M. (2018). L'analisi transazionale organizzativa: Comprendere e migliorare le dinamiche aziendali. Milian: FrancoAngeli.

Cardella, G. M., Hernández-Sánchez, B. R., and Sánchez-García, J. C. (2020). Basic psychological needs as a motivational competence: Examining validity and measurement invariance of Spanish BPNSF scale. Sustainability 12:5422. doi: 10.3390/su12135422

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., and Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56:267. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267

Cerolini, S., Zagaria, A., Vacca, M., Spinhoven, P., Violani, C., and Lombardo, C. (2022). Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire—short: reliability, validity, and measurement invariance of the Italian Version. Behav. Sci. 12:474. doi: 10.3390/bs12120474

Chambless, D. L., and Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 66:7. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.7

Cipolletta, S., Mercurio, A., and Pezzetta, R. (2022). Perceived social support and well-being of international students at an Italian university. J. Int. Stud. 12, 613–632. doi: 10.32674/jis.v12i3.3954

Costa, S., Ingoglia, S., Inguglia, C., Liga, F., Lo Coco, A., and Larcan, R. (2018). Psychometric evaluation of the basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration scale (BPNSFS) in Italy. Measur. Eval. Counsel. Dev. 51, 193–206. doi: 10.1080/07481756.2017.1347021

Crits-Christoph, P., and Mintz, J. (1991). Implications of therapist effects for the design and analysis of comparative studies of psychotherapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 59:20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.59.1.20

Davidson, C., and Mountain, A. (2016). Working Together: Organizational Transactional Analysis and Business Performance. London: Gower. doi: 10.4324/9781315546360

Deeb, G. R., Braun, S., Carrico, C., Kinser, P., Laskin, D., and Golob Deeb, J. (2018). Burnout, depression and suicidal ideation in dental and dental hygiene students. Eur. J. Dental Educ. 22, e70–e74.6. doi: 10.1111/eje.12259

Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Haliczer, L. A., Conkey, L. C., and Whalen, D. J. (2018). Difficulties in interpersonal emotion regulation: initial development and validation of a self-report measure. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 40, 528–549. doi: 10.1007/s10862-018-9647-9

Dupuy, H. J. (1984). “The psychological general well-being (PGWB) index,” in Assessment of Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies, eds. N. K. Wenger, M.E. Mattson, C.D. Furburg, J. Elinson (New York: Le Jacq Publishing).

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., Massie, F. S., Power, D. V., Eacker, A., Harper, W., et al. (2008). Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann. Intern. Med. 149, 334–341 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

Eseadi, C. (2022). An online counseling intervention for nigerian undergraduates with academic burnout. Online Submis. 6, 35–44. doi: 10.24036/00514za0002

Evans, C., Margison, F., and Barkham, M. (1998). The contribution of reliable and clinically significant change methods to evidence-based mental health. BMJ Ment. Health 1, 70–72. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.1.3.70

Ezenwaji, I. O., Eseadi, C., Ugwoke, S. C., Vita-Agundu, U. C., and Agu, M. A. (2019). A group-focused rational emotive behavior coaching for management of academic burnout among undergraduate students: implications for school administrators. Medicine 98:e16352. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016352

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burnout. J. Soc. Issues 30, 159–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

Garnefski, N., and Kraaij, V. (2006). Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire–development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Pers. Individ. Dif. 41, 1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010

Grossi, E., Groth, N., Mosconi, P., Cerutti, R., Pace, F., Compare, A., et al. (2006). Development and validation of the short version of the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB-S). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 4:88. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-88

Guo, X. Q. (2016). The Influencing Factors of College Students' Learning Burnout and Its Intervention Study. Shanxi: Shanxi Medical University.

Hart, T., Fann, J. R., and Novack, T. A. (2008). The dilemma of the control condition in experience-based cognitive and behavioural treatment research. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 18, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/09602010601082359

Iancu, A. E., Rusu, A., Măroiu, C., Păcurar, R., and Maricuţoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 373–396. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9420-8

Jacobson, N. S., and Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 59, 12–19. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

Kadhum, M., Ayinde, O. O., Wilkes, C., Chumakov, E., Dahanayake, D., Ashrafi, A., et al. (2022). Wellbeing, burnout and substance use amongst medical students: a summary of results from nine countries. Int. J. Soc. Psychiat. 68, 1218–1222. doi: 10.1177/00207640221094955

Kim, B., Jee, S., Lee, J., An, S., and Lee, S. M. (2018). Relationships between social support and student burnout: a meta-analytic approach. Stress Health 34, 127–134. doi: 10.1002/smi.2771

Kusuma, R. D., Susanti, I. H., and Sukmaningtyas, W. (2022). The relationship between peer emotional support and burnout in students: literature review. J. Cakrawala Ilmiah 1, 3649–3656. doi: 10.53625/jcijurnalcakrawalailmiah.v1i12.3279

Le Blanc, P. M., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). “Burnout interventions: an overview and illustration,” in Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care, 201–215.

Liu, Y. J. (2013). Effect of comprehensive intervention on learning burnout of college students. China J. Health Psychol. 21, 1843–1845.

Luo, X. (2012). A Study on the Relationship Between Learning Burnout, Attributional Style and Personality Factor of Master Graduate. Liaoning: Liaoning Normal University.

Luo, Z. Y. (2012). The Effect of Time Management Training on Achievement Motivation and Learning Burnout of Middle School Students. Shanxi: Shanxi Medical University.

Madigan, D. J., and Curran, T. (2021). Does burnout affect academic achievement? A meta-analysis of over 100,000 students. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 387–405. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09533-1

Maricutoiu, L. P., Sava, F. A., and Butta, O. (2016). The effectiveness of controlled interventions on employees' burnout: a meta-analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 89, 1–27. doi: 10.1111/joop.12099

Messina, I., Spataro, P., Grecucci, A., Marogna, C., and Dixon-Gordon, K. L. (2022). Difficulties in interpersonal regulation of emotions (DIRE) questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Italian Version and Associations with psychopathological symptoms. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 44, 1126–1134. doi: 10.1007/s10862-022-09992-6

Ni, S. G., and Wu, X. C. (2009). Study on the effect of cognitive behavior interactive group counseling on college students' academic burnout. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 17, 512–514.

Panagioti, M., Panagopoulou, E., Bower, P., Lewith, G., Kontopantelis, E., Chew-Graham, C., et al. (2017). Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674

Perski, O., Grossi, G., Perski, A., and Niemi, M. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of tertiary interventions in clinical burnout. Scand. J. Psychol. 58, 551–561. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12398

Portoghese, I., Galletta, M., Porru, F., Burdorf, A., Sardo, S., D'Aloja, E., et al. (2019). Stress among university students: factorial structure and measurement invariance of the Italian version of the Effort-Reward Imbalance student questionnaire. BMC Psychol. 7, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0343-7

Portoghese, I., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., Galletta, M., Porru, F., D'Aloja, E., et al. (2018). Measuring burnout among university students: factorial validity, invariance, and latent profiles of the Italian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Student Survey (MBI-SS). Front. Psychol. 9:2105. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02105

Purgato, M., Barbui, C., Stroup, S., and Adams, C. (2015). Pragmatic design in randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 45, 225–230. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001275

Rahmati, Z. (2015). The study of academic burnout in students with high and low level of self-efficacy. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 171, 49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.087

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., Maslach, C., and Jackson, S. E. (1996). “The MBIgeneral survey,” in Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, eds. C. Maslach, S. E. Jackson, and M. P. Leiter (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press).

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, M. I., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students - a cross national study, MBI-SS. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 33, 464–481. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033005003

Shen, D. (2020). Study on the design of group counseling program and the effect of intervention on college students' learning burnout. China J. Health Psychol. 28, 453–457.

Shoji, K., Cieslak, R., Smoktunowicz, E., Rogala, A., Benight, C. C., and Luszczynska, A. (2016). Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: a meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 29, 367–386. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2015.1058369

Stewart, I., and Joines, V. (1987). TA Today: A New Introduction to Transactional Analysis. Nottingham: Lifespace Pub.

Tang, L., Zhang, F., Yin, R., and Fan, Z. (2021). Effect of interventions on learning burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:645662. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645662

Thunnissen, M., and Timmermans, M. (2023). Transactional analysis and burnout: for individuals and organizations. Trans. Anal. J. 53, 328–340. doi: 10.1080/03621537.2023.2252308

van Poelje, S., and de Graaf, A. (2021). New Theory and Practice of Transactional Analysis in Organizations: On the Edge. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003173564

Vos, J., and van Rijn, B. (2021). The evidence-based conceptual model of transactional analysis: a focused review of the research literature. Trans. Anal. J. 51, 160–201. doi: 10.1080/03621537.2021.1904364

Vos, J., and van Rijn, B. (2022). The effectiveness of transactional analysis treatments and their predictors: a systematic literature review and explorative meta-analysis. J. Human. Psychol. 2022:00221678221117111. doi: 10.1177/00221678221117111

Vos, J., and van Rijn, B. (2023). Brief transactional analysis psychotherapy for depression: the systematic development of a treatment manual. J. Psychother. Integr. 34, 1–26. doi: 10.1037/int0000304

Wan, Y. (2020). The effect of mindfulness group intervention on college students' mental health. Psychologies 15, 10–19738.

Wege, N., Li, J., Muth, T., Angerer, P., and Siegrist, J. (2017). Student ERI: psychometric properties of a new brief measure of effort-reward imbalance among university students. J. Psychosom. Res. 94, 64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.01.008

Xiong, X. M., and Fang, X. P. (2017). Research on the academic burnout of independent college students in Jiangxi province and its intervention. J. Jiangxi Sci. Technol. Normal Univ. 2, 83–91.

Xu, L. L. (2019). Intervention study of group counseling in orientation of professional quality on college students' academic burnout. J. Beijing Univ. Chem. Technol. 4, 97–102.

Ye, X., Lin, X. H., and Zhou, Y. Y. (2017). The effect of group mindfulness practice on the learning burnout of college students. J. Fujian Med. Univ. 18, 37–40.

Zhang, P., Tang, Q., Du, Y. C., Fu, L., and Zheng, T. (2014). The effect of group counseling on leaning burnout students in engineering college. J. Sichuan Normal Univ. 37, 287–292.

Zhang, Y., Gan, Y., and Cham, H. (2007). Perfectionism, academic burnout and engagement among Chinese college students: a structural equation modeling analysis. Pers. Individ. Diff. 43, 1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.010

Keywords: academic burnout, randomized controlled trial, psychological counseling, group counseling, online counseling

Citation: Messina I, Rossi T, Bonaiuto F, Granieri G, Cardinali P, Petruccelli I, Maniglio R, Loconsole C and Spataro P (2024) Group psychological counseling to contrast academic burnout: a research protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 15:1400882. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1400882

Received: 14 March 2024; Accepted: 15 July 2024;

Published: 31 July 2024.

Edited by:

Changiz Mohiyeddini, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, United StatesReviewed by:

Sílvio Manuel da Rocha Brito, Polytechnic Institute of Tomar (IPT), PortugalCopyright © 2024 Messina, Rossi, Bonaiuto, Granieri, Cardinali, Petruccelli, Maniglio, Loconsole and Spataro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Irene Messina, aXJlbmUubWVzc2luYUB1bmltZXJjYXRvcnVtLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.