- 1Discipline of Health Promotion and Sexology, Curtin School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

- 2Collaboration for Evidence, Research and Impact in Public Health, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

- 3Law School, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 4The Hum Academy, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 5Talk Revolution, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Purpose: To empirically examine associations between parental opposition towards comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) and religiosity.

Methods: A nationally representative survey of Australian parents (N = 2,418) examined opposition towards 40 CSE topics, by parental religiosity and secular/religious school sector.

Results: Whilst opposition to most CSE topics correlated positively with religiosity, even amongst very religious parents, disapproval was minimal (2.8–31.2%; or 9.0–20.2% netted against non-religious parents). Parents with children enrolled in a Catholic school were less likely than secular-school parents to oppose CSE. Those with children at other-faith-schools were more likely to oppose CSE, but again disapproval was minimal (1.2–21.9%; or 1.3–9.4% netted against secular-school parents).

Discussion: Only small minorities of very religious parents and parents with children in religious schools opposed the teaching of various CSE topics. Decision-makers should therefore be cautious about assuming that CSE delivery is not widely supported by particular families.

1 Introduction

The positive and protective benefits that result from comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) are well documented (UNESCO, 2018; Goldfarb and Lieberman, 2021). However, the provision of CSE within schools can be impacted by concern that parents, family members or carers (hereby referred to as parents) oppose the delivery of particular topics (Goldman, 2008; Marson, 2019). Furthermore, parental support and engagement are an integral component to the provision of CSE if an evidence-based whole-school approach is utilized (UNESCO, 2018; Goldfarb and Lieberman, 2021; WHO and UNESCO, 2021).

Within the Australian context, a recent nationwide survey reported significant parental endorsement for school-based provision of CSE (Hendriks et al., 2023). These findings align with an earlier systematic review, which also reported positive attitudes towards CSE across multiple countries (Kee-Jiar and Shih-Hui, 2020). Notwithstanding the emphatic support displayed by Australian parents, CSE provision within Australian schools is widely varied (Ezer et al., 2020). Although CSE implementation is impacted by a variety of factors, opposition is often attributed to the perceived religiosity of parents and has been stated as the reason “why they choose faith-based schools” in Australia (Parkinson, 2023). This may result in curtailment or purposive avoidance of topics in certain school programs, despite their inclusion in Australian school curricula (ACARA, 2023) and international guidelines (UNESCO, 2018).

The impact religion has on CSE provision has been explored in a variety of contexts. For example, Wareham (2022) recently presented three normative case studies from Wales to help illustrate the inherent problems that result when CSE provision is impacted by faith-based ‘carve-outs.’ In contrast, Sanjakdar (2018) draws upon interviews with secondary students in New Zealand and Australia, to argue for the value of including religion in CSE and its ability to develop critical perspectives.

Presently in Australia, vague curriculum guidance affords schools with great flexibility to avoid certain CSE issues (Ezer et al., 2018). Students report a prevailing deficit discourse and general dissatisfaction with current offerings (Ezer et al., 2019; Waling et al., 2021; Waling et al., 2020; Vrankovich et al., n.d.), and for particular sub-populations, their sexuality is often marginalized or ignored (Frawley and O’Shea, 2020; Senior et al., 2020; Mulholland et al., n.d.). Finally, the teaching workforce is often poorly prepared or supported to deliver this content, resulting in discomfort and low confidence levels (Hendriks et al., 2024; Ezer et al., 2021; Burns et al., 2023; O’Brien et al., 2020).

Therefore, to further strengthen the evidence base regarding religion and attitudes toward CSE provision in Australian schools, specific empirical investigations were conducted to examine associations between parental religiosity and opposition towards teaching CSE topics. Based on the national dataset of Australian parents, who shared their perspectives towards a wide array of CSE topics (Hendriks et al., 2023), we undertook targeted analyses to examine if levels of support were associated with either (a) the personal importance of religion to their daily life, or (b) the school sector in which they had enrolled their child(ren).

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

Australian parents with children enrolled in a primary or secondary school completed an online survey (N = 2,418), with items based on a previous Canadian study (Wood et al., 2021). Additional methodology details and preliminary findings have been published previously (Hendriks et al., 2023; Hendriks et al., 2024), and the study was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2021-0483).

2.2 Measures

Simple demographic data was obtained from all participants. Furthermore, three specific items from the broader survey were the focus of this current analysis:

i. Support for specific CSE topics: Respondents indicated the earliest grade level at which 40 different CSE topics should first be taught within a school context. Those selecting this topic should not be taught (i.e., at any grade level) were considered to oppose CSE in some form.

ii. Religiosity: Respondents indicated the importance of religion to their everyday life: not at all (hereafter “non-religious”), not very, somewhat, very.

iii. School sector: “secular” means their child(ren) attended only a government or a non-faith school; “Catholic” means any child attending a Catholic school; “other-faith” means any child attending a religious (not Catholic) school.

2.3 Statistical procedure

Crosstabulation analyses were conducted using commercial statistical software, with statistical significance determined via Chi square tests and confirmed via manual analysis in Microsoft Excel. I do not know/prefer not to answer responses ranged from 1.1 to 5.4% of responses for all topics except “abstinence,” which was 8.7%, and all were excluded from analysis.

3 Results

3.1 General

Nearly two-thirds of parents (63.0%) supported the teaching all 40 CSE topics, with fewer than one in five (18.9%) opposed to one or two topics, and a similar proportion (18.1%) opposed to three or more topics.

There was no statistical association between the gender of a parent and their objection to any (one or more) CSE topics. Parents with children only at primary school were more likely to oppose teaching one (but not more) CSE topic than parents with any child at a secondary school, but the difference was small (15.9% versus 12.1%, p < 0.01).

3.2 Parent religiosity

Among the 2,304 parents who answered the religiosity question, 42.3% were non-religious, 18.9% not very religious, 19.9% somewhat religious, and 18.9% very religious. Of parents with a child at any religious school, 28.3% were non-religious, 24.1% not very religious, 24.9% somewhat religious, and 22.8% very religious.

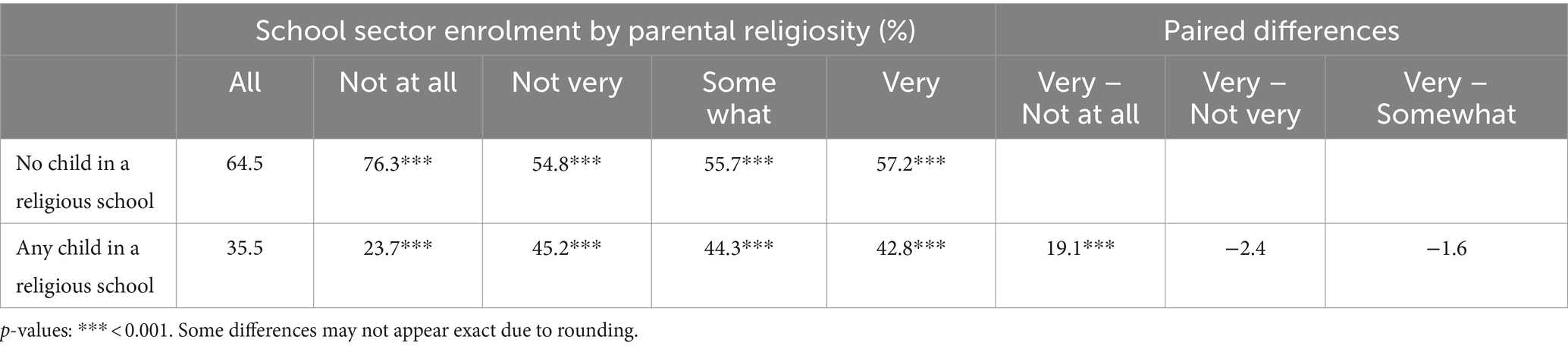

Table 1 shows the prevalence of child enrolment in government/secular versus religious schools by parental religiosity. Non-religious parents were significantly less likely (19.1% less likely than very religious parents, p < 0.001) to have enrolled their child/ren in a religious school. Amongst more religious parents there were minorities of and no significant differences in religious school enrolment (45.2% not very religious, 44.3% somewhat religious, and 42.8% very religious). That is, non-religious parents were more likely to reject religious schools, but the likelihood of selecting a religious school amongst other parents did not correlate with greater religiosity.

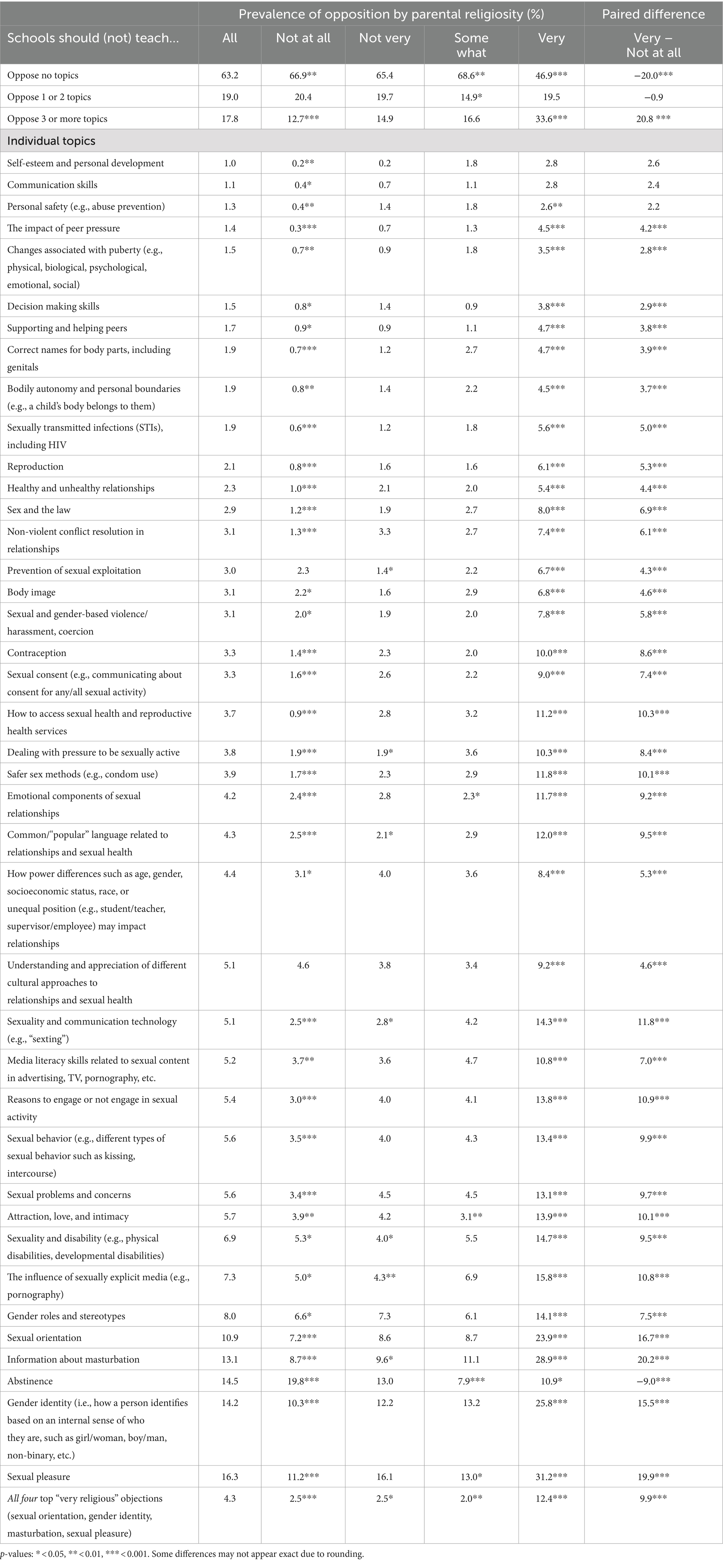

Table 2 shows the prevalence of parental opposition to the 40 CSE topics by parental religiosity. Overall, very religious parents were the most likely to oppose topics. Amongst these parents, opposition to teaching topics at school generally ranged from 2.8% (communication skills) to less than one-third (31.2%, sexual pleasure), compared with 0.2% (communication skills) to 11.2% (sexual pleasure) amongst non-religious parents.

Table 2. Prevalence of parental opposition to teaching CSE topics at school, by parental religiosity.

Opposition to the topic of abstinence was notable (19.8% amongst non-religious, 10.9% amongst very religious) and requires further exploration. We postulate that there may have been measurement error in that some respondents may have thought this item referred to abstinence-only education. Of note, 8.7% selected I do not know/prefer not to answer for this item, when for most other items the percentage was well below 5.0%.

Very religious parents were most likely to oppose topics related to sexual pleasure (31.2% sexual pleasure, 28.9% information about masturbation), gender identity (25.8%), sexual orientation (23.9%), and the influence of sexually explicit media (e.g., pornography; 15.8%). Amongst the remaining topics, opposition was less than 15% and for 9/40 topics it was less than 5%.

The prevalence of opposition amongst very religious parents netted against non-religious parents — to adjust for non-religious opposition — was statistically significant for most topics (37/40 topics, each p < 0.001). This provides additional evidence that higher levels of religiosity are associated with opposition towards CSE. However, the magnitude of these significant differences was modest, from 2.8% (changes associated with puberty) to 20.2% (information about masturbation), each p < 0.001. The only topic where very religious parents were less (not more) likely to oppose was abstinence (−10.9%, p < 0.001), again suggesting that some non-religious parents may have interpreted the question as abstinence-only education.

3.3 School sector

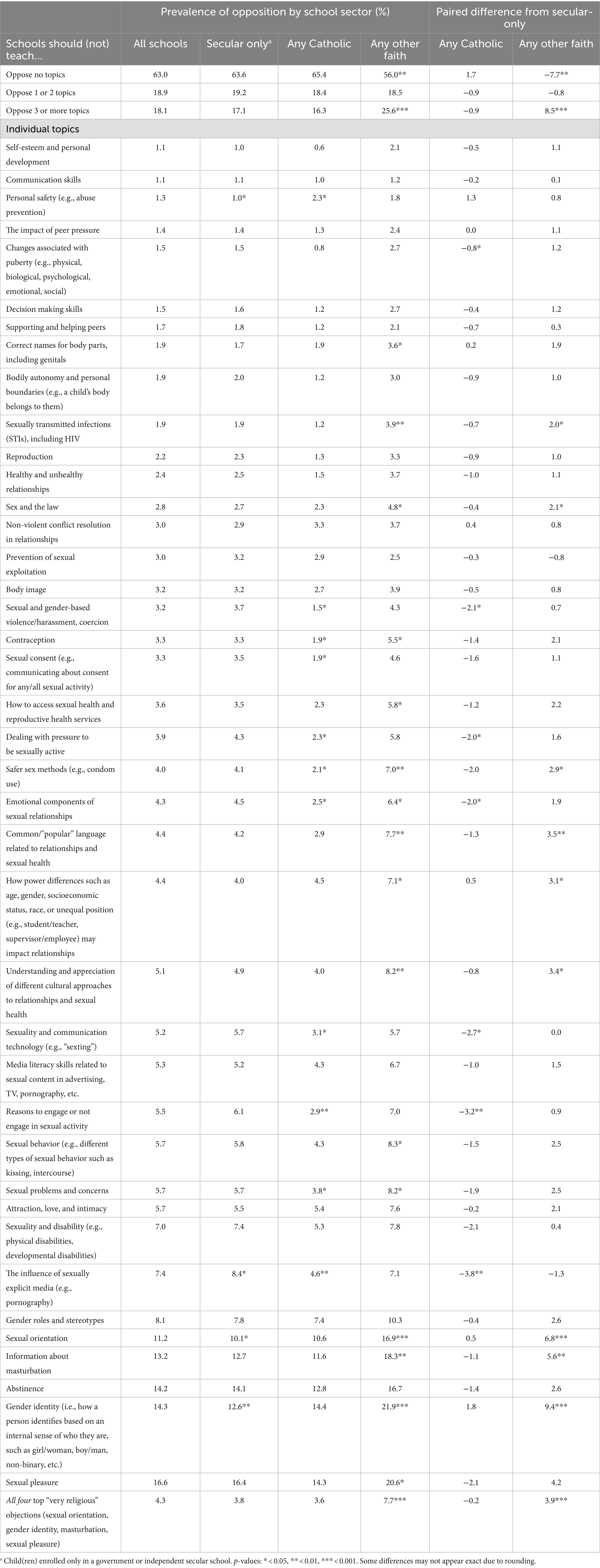

Table 3 shows the prevalence of parental opposition to the 40 CSE topics by school sector. Across all three school sectors, majorities of parents opposed none of the 40 topics (63.6% of secular-school-only parents, 65.4% of Catholic-school parents and 56.0% of other faith-school parents).

Table 3. Prevalence of parental opposition to teaching CSE topics at school, by child enrolment school sector.

In comparison to secular-school parents, Catholic-school parents were often less likely to oppose CSE topics. However, net differences were only statistically significant for 7/40 topics. In comparison to secular-school parents, other-faith-school parents were often more likely to oppose CSE topics. Similarly, net differences were only statistically significant for 9/40 topics.

Amongst Catholic-school parents, opposition was 5% or less for 32/40 CSE topics. This included low levels of opposition towards topics such as contraception (1.9%) and safer sex methods (e.g., condoms; 2.1%) that are often considered contrary to a Catholic school education.

Opposition was more prevalent amongst other-faith-school parents, however, still at 5% or less for 18/40 topics. Amongst parents with children enrolled in a non-secular school, the greatest opposition was reserved for gender identity (14.4% amongst Catholic-school parents; 21.9% amongst other-faith-school parents) and sexual pleasure (14.3% amongst Catholic -school parents; 20.6% amongst other-faith-school parents).

3.4 Religious parents and school sector choice

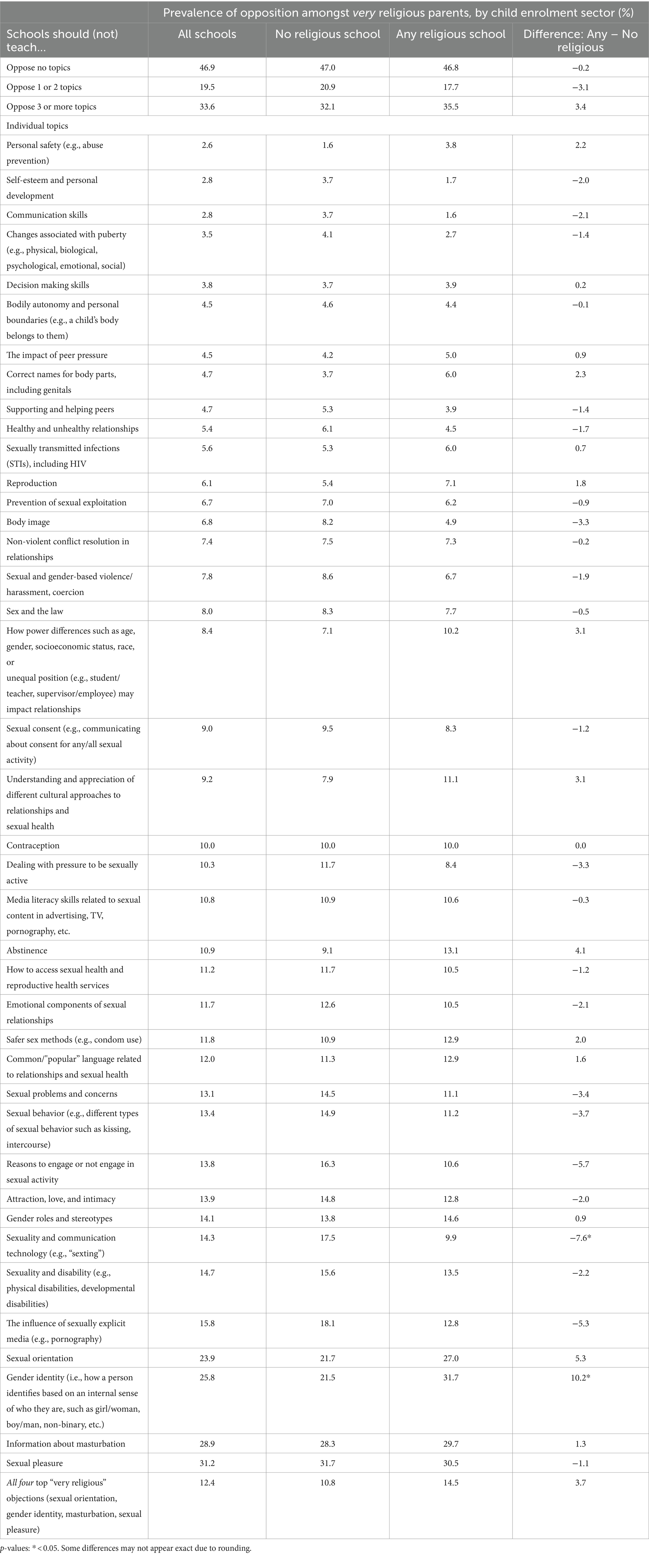

To determine whether attitudes differed amongst religious parents with children in religious schools versus non-religious schools, the prevalence of opposition to CSE topics amongst very religious parents was compared by those with children only at non-religious schools, versus those with any child at a religious school (Table 4).

Table 4. Prevalence of opposition to CSE topics amongst very religious parents by child enrolment sector.

Of the 40 topics, very religious parents with a child at a religious school appeared more likely to oppose 16 topics, but more likely to support 24 topics. However, the differences were small and only two were statistically significant. Very religious parents with a child at a religious school were 7.6 percentage points less likely (a difference of around one in 13 parents) to oppose schools teaching children about sexuality and communications technology (e.g., “sexting”) (p < 0.05), and 10.2 percentage points more likely (around one in 10 parents) to oppose teaching gender identity (p < 0.05).

Even amongst very religious parents with a child at a religious school, opposition to CSE topics was less than one third (maximum 31.7%, gender identity) and often much less.

4 Discussion

Although other studies in the previous decade have examined parental attitudes towards CSE, despite collecting data about the religious affiliations of their respondents, most have not factored this into their statistical analyses (Wood et al., 2021; Dake et al., 2014; Fisher et al., 2015; Kantor and Levitz, 2017; McKay et al., 2014). An exception has been the recent work of Hurst et al. (2024) who reported, based on a national sample of parents across the United States of America, that there was strong support for students to receive CSE focused on three content areas: factual knowledge, practical skills, and pleasure and identity. However, politically conservative parents who also expressed high levels of religiosity expressed lower levels of support (Hurst et al., 2024).

In this study, whilst parental opposition towards schools delivering various CSE topics is positively associated with religiosity, the magnitude of any dissent is modest. Even amongst Australian parents who are very religious, opposition towards CSE topics is less than one-third (maximum 31.2%) and considerably lower in most instances. Amongst all parents with children enrolled in religious schools (of which 22.8% are very religious and 28.3% are not at all religious), the level of opposition towards various CSE topics is an even smaller minority: a maximum of 14.4% amongst Catholic-school parents and 21.9% amongst other-faith-school parents. Compared with secular-school parents, Catholic-school parents are overall less likely to oppose topics, and the premium in opposition amongst other-faith-school parents is less than one-in-ten (up to 9.4%). At Australian religious schools, only minorities of all parents (maximum 21.9%) and even very religious parents (maximum 31.7%) oppose any CSE topic, and the prevalence of opposition is often much less. The contention that most or all religious-school parents, including very religious ones, oppose schools teaching CSE topics including the most contended topics of sexual orientation, gender identity and sexual pleasure, is rejected.

Given the minority prevalence of opposition to CSE topics amongst parents at Australian religious schools, the contention that most or even a majority choose religious schools significantly because of conservative or tradition-normative views regarding sexuality, is rejected.

The finding that very religious parents are not more likely than not-very-religious parents to choose a religious school is also consistent with rejecting the contention. However, we were unable to correct for possible differences in socio-economic status amongst the cohorts in regard to the ability of families to afford non-government school fees, and so this finding requires further study.

The findings complement other analyses our team has undertaken to demonstrate that most Australian parents express supportive attitudes towards diverse sexual orientations, gender diversity, and actions to address homophobia and transphobia. Such support is expressed by parents of all religious affiliations and parents who have enrolled their child(ren) in a religious school (Hendriks et al., 2024). Similarly, other Australian research has also reported low levels of opposition (5.6%) towards relationships and sexuality education amongst parents of children attending a government school (Ullman et al., 2022). However, the religiosity of the parent was not considered in any of their statistical analyses and only one school sector was considered.

4.1 Strengths, limitations and future directions

The data presented here is a sub-set of a much broader series of analyses. Additional data and details about strengths and limitations of the broader study have been reported previously (Hendriks et al., 2023; Hendriks et al., 2024). Whilst the sample closely matched population estimates it may not be truly nationally representative based on particular demographic characteristics (Hendriks et al., 2023). The survey instrument did not collect data about socio-economic status and was conducted in the English language only. However, in relation to the survey items that were the focus of this manuscript, a large and diverse sample was obtained. A significant proportion of the respondents identified themselves as religious and reported a broad array of religious affiliations that align closely with recent census results (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021). The proportion of respondents from each school sector closely approximates population estimates (Hendriks et al., 2024).

Our study does not provide evidence of attitudes at individual schools or at schools of a particular religious tradition other than Catholic. Nevertheless, given overall that minorities of parents — even very religious ones — at religious schools oppose CSE topics, an individual school with a majority of parents opposing a particular CSE topic may be possible. Schools should therefore be encouraged to engage widely and empirically with their parents to understand their viewpoints, rather than to make assumptions.

To further progress our understanding of the intersections between religiosity and CSE provision, future research should focus on qualitative data collection to provide greater insight into the perspectives of parents. Purposeful sampling frames should be used to ensure a diverse range of religious affiliations are captured, and parent perspectives should be triangulated with data from school students and teaching staff. Finally, future research and school programs should focus on trying to achieve pluralism in this space (Sanjakdar, 2018). Whilst we need to ensure particular viewpoints do not curtail evidence-based CSE provision, we similarly need to be respectful of religious perspectives.

5 Conclusion

These findings empirically dispute the contention that most parents who are very religious, or who have selected a non-secular school for their child(ren), do not endorse schools to deliver a comprehensive sexuality education program. Policymakers, educators, and other decision-makers should not assume the sexuality values held by parents. Furthermore, evidence-based guidelines direct that quality programs should embrace whole-school approaches that include strong parental engagement.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. NF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. HS: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JW: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NL: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SB: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Sexual Health and Blood-borne Virus Program of the Western Australian Department of Health’s Communicable Disease Control Directorate.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor JF declared a past collaboration RT with the author JH.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed herein are not necessarily those of the funding body or the Government of Western Australia.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021) Cultural diversity: Census: ABS. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/2021 (Accessed August 29, 2024).

ACARA. (2023) Health and physical education. F-10 curriculum. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. Available at: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/teacher-resources/understand-this-learning-area/health-and-physical-education

Burns, S., Saltis, H., Hendriks, J., Abdolmanafi, A., Davis-Mccabe, C., Tilley, P. M., et al. (2023). Australian teacher attitudes, beliefs and comfort towards sexuality and gender diverse students. Sex Educ. 23, 540–555. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2022.2087177

Dake, J. A., Price, J. H., Baksovich, C. M., and Wielinski, M. (2014). Preferences regarding school sexuality education among elementary schoolchildren's parents. Am. J. Health Educ. 45, 29–36. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2013.852998

Ezer, P., Jones, T., Fisher, C., and Power, J. (2018). A critical discourse analysis of sexuality education in the Australian curriculum. Sex Educ. 19, 551–567. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1553709

Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Fisher, C. M., Heywood, W., and Lucke, J. (2019). Australian students’ experiences of sexuality education at school. Sex Educ. 19, 597–613. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1566896

Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Fisher, C. M., Waling, A., Bellamy, R., and Lucke, J. (2020). School-based relationship and sexuality education: what has changed since the release of the Australian curriculum? Sex Educ. 20, 642–657. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1720634

Ezer, P, Power, J, Jones, T, and Fisher, C. (2021). 2nd national survey of Australian teachers of sexuality education 2018. Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

Fisher, C. M., Telljohann, S. K., Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., and Glassman, T. (2015). Perceptions of elementary school children's parents regarding sexuality education. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 10, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2015.1009595

Frawley, P., and O’Shea, A. (2020). ‘Nothing about us without us’: sex education by and for people with intellectual disability in Australia. Sex Educ. 20, 413–424. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1668759

Goldfarb, E. S., and Lieberman, L. D. (2021). Three decades of research: the case for comprehensive sex education. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.036

Goldman, J. D. G. (2008). Responding to parental objections to school sexuality education: a selection of 12 objections. Sex Educ. 8, 415–438. doi: 10.1080/14681810802433952

Hendriks, J., Francis, N., Saltis, H., Marson, K., Walsh, J., Lawton, T., et al. (2024). Parental attitudes towards sexual orientation and gender diversity: challenging LGBT discrimination in Australian schools. Cult. Health Sex., 1–16. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2024.2394223

Hendriks, J., Marson, K., Walsh, J., Lawton, T., Saltis, H., and Burns, S. (2023). Support for school-based relationships and sexual health education: a national survey of Australian parents. Sex Educ. 24, 208–224. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2023.2169825

Hendriks, J., Mayberry, L., and Burns, S. (2024). Preparation of the pre-service teacher to deliver comprehensive sexuality education: teaching content and evaluation of provision. BMC Public Health 24:1528. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18982-0

Hurst, J. L., Widman, L., Brasileiro, J., Maheux, A. J., Evans-Paulson, R., and Choukas-Bradley, S. (2024). Parents’ attitudes towards the content of sex education in the USA: associations with religiosity and political orientation. Sex Educ. 24, 108–124. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2022.2162871

Kantor, L., and Levitz, N. (2017). Parents’ views on sex education in schools: how much do democrats and republicans agree? PLoS One 12:e0180250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180250

Kee-Jiar, Y., and Shih-Hui, L. (2020). A systematic review of parental attitude and preferences towards implementation of sexuality education. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 9:971. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v9i4.20877

Marson, K. (2019). Ignorance is not innocence: Safeguarding sexual wellbeing through relationships and sex education. Brisbane: The University of Queensland: Winston Churchill Memorial Trust.

McKay, A., Byers, E. S., Voyer, S. D., Humphreys, T. P., and Markham, C. (2014). Ontario parents' opinions and attitudes towards sexual health education in the schools. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 23, 159–166. doi: 10.3138/cjhs.23.3-A1

Mulholland, M. A., Sanjakdar, F., and Opie, T. (2024). ‘Too many assumptions’: cultural diversity and the politics of inclusion in sexuality education. Sex Educ., 1–15. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2024.2324011

O’Brien, H., Hendriks, J., and Burns, S. (2020). Teacher training organisations and their preparation of the pre-service teacher to deliver comprehensive sexuality education in the school setting: a systematic literature review. Sex Educ. 21, 284–303. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1792874

Parkinson, P. (2023) Submission #95 to the ALRC consultation paper on religious schools and anti-discrimination laws Canberra, Australian Law Reform Commission. Available at: https://www.alrc.gov.au/95-Prof-P-Parkinson-AM-ADL-submission (Accessed October 19, 2023).

Sanjakdar, F. (2018). Can difference make a difference? A critical theory discussion of religion in sexuality education. Discourse 39, 393–407. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2016.1272546

Senior, K., Chenhall, R., and Helmer, J. (2020). ‘Boys mostly just want to have sex’: young indigenous people talk about relationships and sexual intimacy in remote, rural and regional Australia. Sexualities 23, 1457–1479. doi: 10.1177/1363460720902018

Ullman, J., Ferfolja, T., and Hobby, L. (2022). Parents’ perspectives on the inclusion of gender and sexuality diversity in K-12 schooling: results from an Australian national study. Sex Educ. 22, 424–446. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2021.1949975

UNESCO (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach. Revised Edn. Paris: UNESCO.

Vrankovich, S., Hamilton, G., and Powell, A. (2024). Young adult perspectives on sexuality education in Australia: implications for sexual violence primary prevention. Sex Educ., 1–16. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2024.2367216

Waling, A., Bellamy, R., Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Lucke, J., and Fisher, C. (2020). ‘It’s kinda bad, honestly’: Australian students’ experiences of relationships and sexuality education. Health Educ. Res. 35, 538–552. doi: 10.1093/her/cyaa032

Waling, A., Fisher, C., Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Bellamy, R., and Lucke, J. (2021). “Please teach students that sex is a healthy part of growing up”: Australian students’ desires for relationships and sexuality education. Sex. Res. Social Policy 18, 1113–1128. doi: 10.1007/s13178-020-00516-z

Wareham, R. J. (2022). The problem with faith-based carve-outs: RSE policy, religion and educational goods. J. Philos. Educ. 56, 707–726. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.12700

WHO and UNESCO. (2021). Making every school a health-promoting school: global standards and indicators for health-promoting schools and systems. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025059 (Accessed July 13, 2021).

Keywords: comprehensive sexuality education, parent attitudes, religion, religiosity, school sector, Australia

Citation: Hendriks J, Francis N, Saltis H, Marson K, Walsh J, Lawton N and Burns S (2024) Parental opposition to comprehensive sexuality education in Australia: associations with religiosity and school sector. Front. Psychol. 15:1391197. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1391197

Edited by:

Jessie Ford, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Filippo Maria Nimbi, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCatarina Samorinha, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2024 Hendriks, Francis, Saltis, Marson, Walsh, Lawton and Burns. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jacqueline Hendriks, amFjcXVpLmhlbmRyaWtzQGN1cnRpbi5lZHUuYXU=

Jacqueline Hendriks

Jacqueline Hendriks Neil Francis2

Neil Francis2 Hanna Saltis

Hanna Saltis Natasha Lawton

Natasha Lawton Sharyn Burns

Sharyn Burns