- Department of Organizational Psychology, School of Business, Economics and Informatics, Birkbeck, University of London, London, United Kingdom

In this article I explain the value of autistic perspectives in research and argue that support for autistic scholars, community leaders and professionals are required as an inclusive research consideration. I propose consolidation, innovation, and evaluation of inclusive research principles, with consideration given to epistemic agency, autistic participation, and actionable research outcomes. I then present “Eight Principles of Neuro-Inclusion,” a reflexive tool that I have designed as a way of encouraging new developments of inclusive research practices. Through flexible application of this approach, it is hoped that innovative new inclusive methods will materialize, in pursuit of epistemic justice, and in support of actionable research outcomes that benefit our autism community.

Introduction

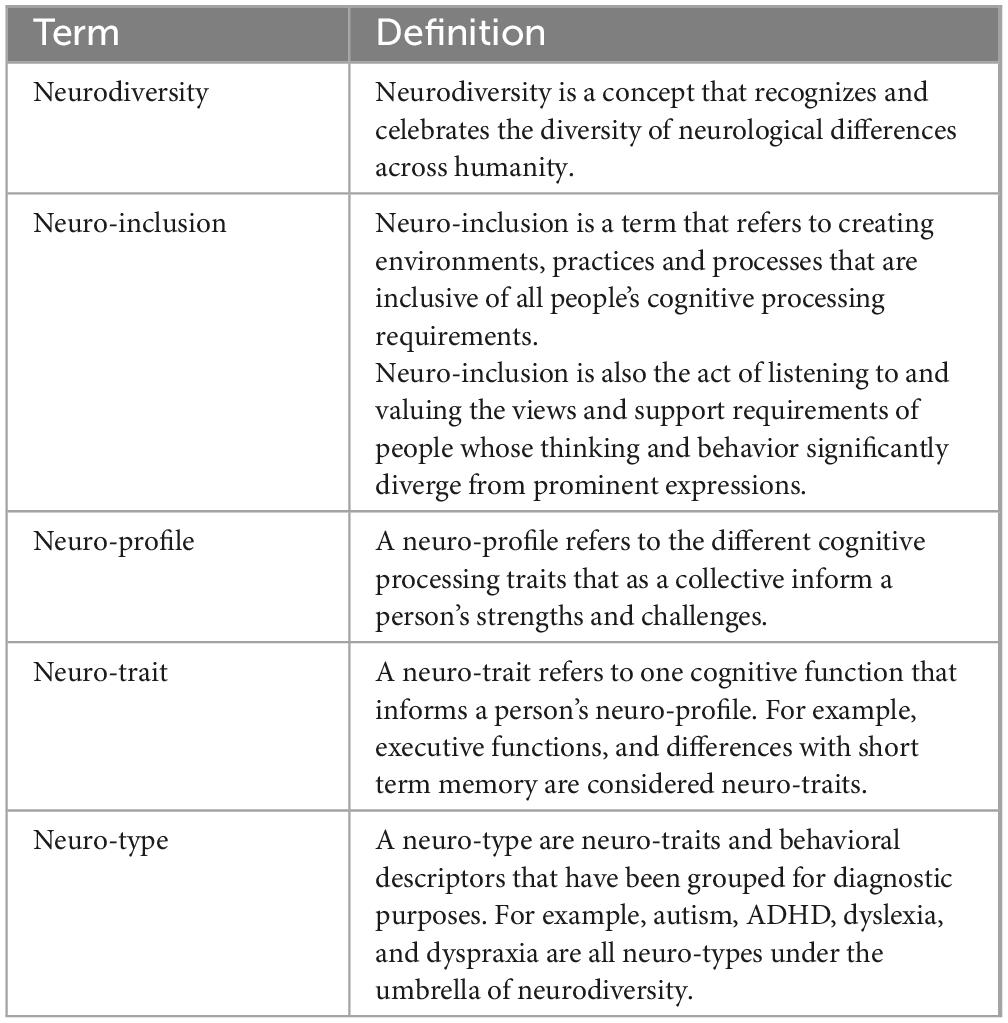

Autism is a neuro-developmental condition that is medically characterized in the DSM-5-TR as persistent challenges across all three social criteria; social communication, social interaction, and social reciprocity, in addition to meeting two of the four categories related to restrictive and repetitive behavior, including repetitive activities, restrictive interests, following routines and rituals and repetitive sensory behaviors (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013, 2022). However, from a neurodiversity perspective autism is regarded as a natural variation of the human genome (Singer, 2016), and from an embodiment stance; an integral aspect of who a person is (De Jaegher, 2013). There is current debate regarding which language should be used when discussing autism in research (Flowers et al., 2023), with no consensus currently established (Botha et al., 2023). As such, I have chosen to use identity first language; autistic person, rather than person with autism, and I do not capitalize the term “autism” within the writing of this article. I have selected these language choices to affirm my alignment with neurodiversity and embodiment perspectives, thereby recognizing autism as a neuro-type under the umbrella of neurodiversity, with unique strengths and challenges that diverge from prominent ways of thinking and behaving. Due to the continuous development of language associated with neurodiversity, in Table 1 share a glossary of terms used in this article.

The way that autism is represented in research is currently regarded as an epistemic injustice (Catala et al., 2021). The literature is awash with stereotypes (Draaisma, 2009) and derogatory language (Botha and Cage, 2022) that shape how autism is understood (Botha et al., 2023). Emancipatory research has informed different ways of working with disability groups, including the use of inclusive research methods and participatory approaches. These methods aim to include disabled participants in research either through adapting research materials and procedures (Aldridge, 2012; Ellard-Gray et al., 2015), or by actively engaging participants as co-researchers throughout the research process (Aldridge, 2012; 2016; Brown, 2021).

In this article I discuss why consolidation, evaluation, and innovation of inclusive research principles are required for improved inclusion of autistic people in research, and argue why inclusion of autistic scholars, community leaders, and professionals should be considered under the umbrella of inclusive research methods. I then present “Eight Principles of Neuro-Inclusion” a reflexive tool that I have designed as a way of encouraging uptake and development of inclusive research methods, in support of better understanding and improved life opportunities for our autism community.

Why new approaches are needed for the inclusion of autistic people in research?

Autistic people currently experience many inequalities across society. COVID-19 informed glaring inequalities for autistic people accessing healthcare (Oakley et al., 2021). Health inequalities have also been demonstrated by some autistic groups being unable to access a timely diagnosis (Leedham et al., 2019). Education is also a concern, with many autistic children unable to access appropriate schooling (Hasson et al., 2022). Furthermore, the low employment figure for autistic people at 22% (The Autism Employment Gap, 2021) demonstrates that our autism community are experiencing exclusion across the entirety of their lifespan, and experience inequality across all aspects of society. Amidst these challenging times, autistic people have raised concern that research does not reflect their personal understanding of autism (Gowen et al., 2020). If actionable research outcomes that increase the understanding of autism are to materialize, how research is conducted must be considered in relation to inclusive research methods, in order to improve the impact of the research produced.

Inclusive and participatory approaches are valuable research methods in support of marginalized communities (Aldridge, 2012). However, current approaches are not without challenges. For instance, it is recognized that when conducting participatory research there may be challenges with funding and the coordination and allocation of roles (König et al., 2022). Furthermore, the research process may require additional implementation time when compared with traditional methods (Hewitt et al., 2023). Despite an inclusive approach increasing community engagement (Aldridge, 2012), challenges with demographic recruitment, and autistic representation in research, are not frequently addressed. As such, varied and innovative approaches to inclusive methods are required for an improved understanding of autism to materialize.

The autistic researcher

It is often assumed that the researcher voice is that of non-autistic scholars, and for the large part this is true. However, it is recognized that the incorporation of autistic voices leads to higher quality research (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al., 2019) and that autistic researchers bring unique strengths to the interpretation of data (Grant and Kara, 2021). Academia is regarded a good career path for autistic people who are pursuing research topics that they are passionate about (Jones, 2023). As such, there is a growing number of autistic people studying and working in academia that conduct research with their own autism community (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al., 2023; Fletcher-Watson et al., 2021). Furthermore, there are many autistic community members and professionals, that if appropriately supported to lead practitioner research, would inform the phenomena in uniquely meaningful ways.

Encouraging autistic people to lead research surpasses diagnostic labeling alone. Autistic scholars bring specific skills to research, such as attending to topics of interest for prolonged periods and paying good attention to detail (Grant and Kara, 2021). The lived experience of the autistic researcher informs a level of shared-neuro-trait relevancy and empathy to the interpretation of data (Grant and Kara, 2021). Thus, autistic researchers are able to draw from both personal insights and extensive study in the field, or broad clinical and community involvement, rather than relying on literature alone to inform their understanding of the phenomena.

Despite the benefits of autistic led research; academia poses its own challenges. It is noted that as a profession, there is a tendency to overwork (Jones, 2023), with a “dutiful” mentality that encourages researchers to “get on with things, even when it causes them burnout or distress” (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al., 2023, p.1236). Furthermore, the environmental demands of studying and challenges associated with appropriate understanding and support at university (Gurbuz et al., 2019) likely act as a barrier or deterrent to those considering a research career. As such, I propose that for autistic scholars, community leaders and professionals to successfully undertake research with their own community, consideration of all autistic people’s support needs must be recognized under the umbrella of inclusive research methods.

Eight principles of neuro-inclusion

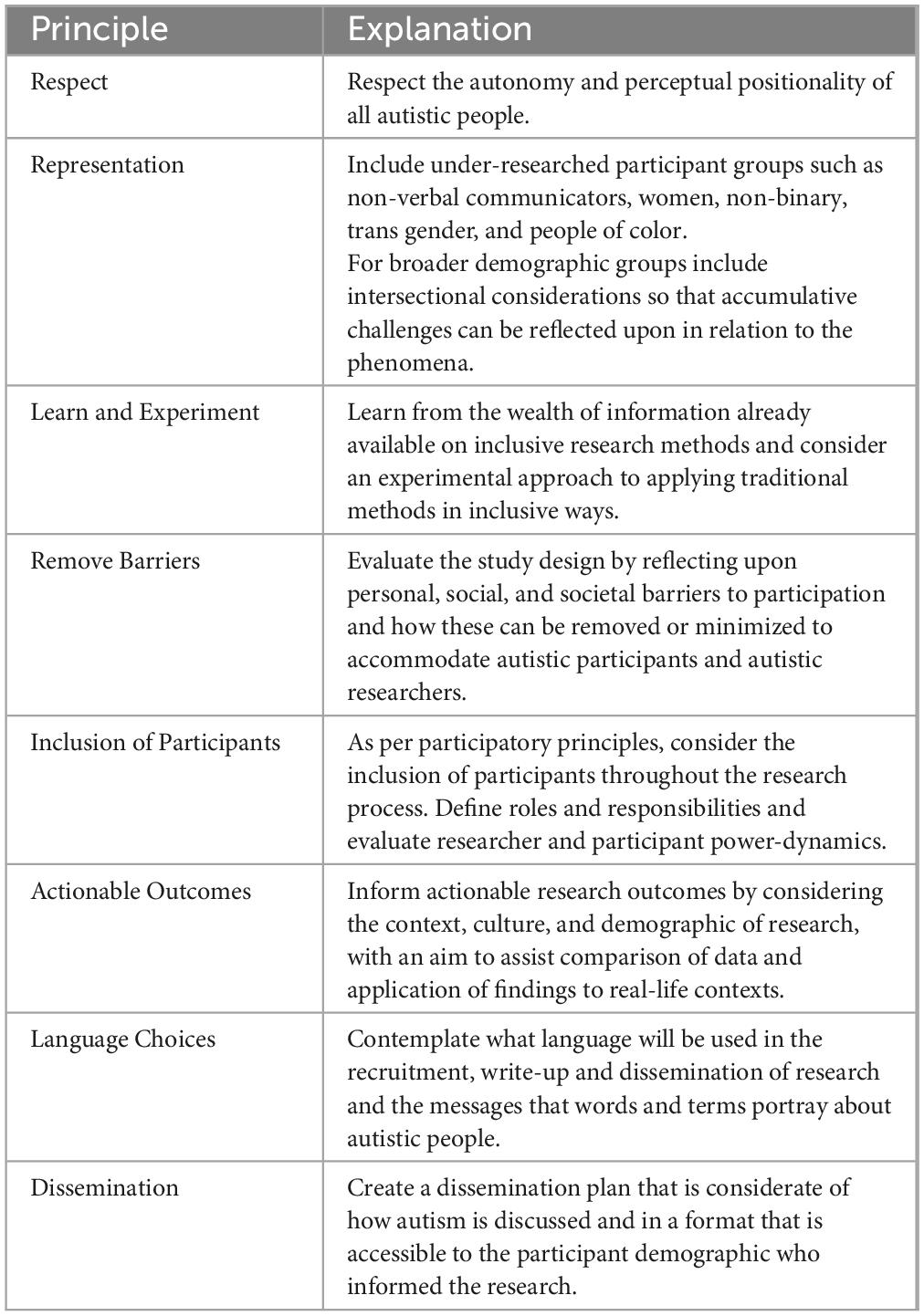

In support of improved inclusion of autistic people in research I have developed the “Eight Principles of Neuro-Inclusion” outlined in Table 2, a reflexive tool that can be used by scholars of all neuro-types when working with autistic participant groups to inform their inclusive research practice. The approach is considerate of method, procedure, and dissemination of research, whilst also being mindful of both the autistic participant and the autistic scholars support needs. I hope that as further developments in the field of inclusive research methods progress, broader autistic demographics and hard-to-reach community views will be included in research, in addition to encouraging and supporting more autistic practitioners and scholars to lead, facilitate, and disseminate research with their own autism community. The following sub-headings present each principle in turn, explaining how they inform inclusive considerations when conducting research with autistic demographic groups.

Principle 1-respect

The foundation of inclusive research practices must be “respect” – “Researchers need to actively demonstrate that they value lived experience” (Nicolaidis et al., 2019, p.2012). Respecting the unique and varied expressions of autism, as informed by autistic people, is paramount when conducting research with autistic participant groups (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). The principle for respect is borne out of the recognition that autistic people’s experiences and perception of the world is an embodiment of self (De Jaegher, 2013) with thinking, behavior and experiences of the world uniquely informed by people’s underlying autistic neurology (Sinclair, 1993; Cooper et al., 2020). Therefore, to understand autistic people’s perceptions of the world, first recognition of autistic perceptual differences (Milton, 2012) is required.

As advised by non-autistic scholar Thompson-Hodgetts (2022), researcher positionality is an important reflexive consideration for all scholars conducting research alongside autistic participants. A recent survey by Botha and Cage (2022) included the views of 195 autism researchers who were asked five open-ended questions related to autism research. Results indicated that greater inclusion of autistic people reduced ableist cues in the discussion of autism, thereby evidencing how a community informed approach, not only promotes autistic voices to be heard, but also researchers who adopt this way of working, better align their thinking with a community understanding. As such, informing research from a community perspective is beneficial to autistic people’s representation in research regardless of the neuro-type of the researcher. Therefore, I suggest that adopting an autism community informed approach is a respectful way to conduct research with autistic people that all researchers of all neuro-types can implement.

Principle 2-representation

Research often includes a WEIRD; White, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic participant sample (Henrich et al., 2010). Participant homogeneity can be beneficial when gaining consensus within a group, but it has limitations when understanding diversity across a demographic (Apfelbaum et al., 2014). Inclusive research often aims to include a range of different autistic people across the broad scope of the autism spectrum; albeit not all at once. As such, active recruitment of under-represented autistic groups, such as non-verbal communicators (Hickman, 2022), women (D’Mello et al., 2022), non-binary, transgender (Gratton et al., 2023), and people of color (Malone et al., 2022) should be considered. Furthermore, for broad demographic samples it may be beneficial to evaluate intersectional differences, such as gender, race, and socio-economic status, so that accumulative challenges can be understood across the participant sample, in relation to the phenomena (Cascio et al., 2020).

Principle 3-learn and experiment

Principle three suggests that an experimental approach to applying traditional research methods is required for the inclusion of autistic people. Traditional research methods have a wealth of reliability and validity supporting their use. However, application of traditional techniques is often underpinned by rigid and directive guidance that may not be suitable for autistic researchers to implement, nor does it support effective engagement of autistic participants in research.

Activities associated with learning from and adapting traditional methods could include, reviewing guides on inclusive research practice, and drawing from articles that use or evaluate inclusive and participatory approaches. Adapting methods involves considering alternative ways of applying traditional techniques, such as a walk and talk interview style to aide participant engagement (North, 2021), or using creative methods to support participants to express their views in alternative ways (Lewis et al., 2023). Through learning from, evaluating, and applying traditional methods in new ways, the collective understanding of inclusive research will improve, and over time new inclusive methods will become proven ways of working in their own right.

Principle 4-remove barriers

Different autistic participant groups may require different approaches to inclusion (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). For instance, an autistic participant sample with low language levels or who are in assisted employment, may require a different approach to an autistic participant group who are living and working independently. Thus, it is beneficial to reflect upon how the chosen method impacts the participant (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). For instance, it may be beneficial to provide an online interview to mitigate the cognitive demands of traveling to an in-person location (Crane et al., 2023) or provide rest breaks during an interview (North, 2021) to reduce the impact of social and sensory demands.

It is also beneficial to evaluate and remove barriers for the autistic researcher by considering what adjustments are required when leading research. For instance, it is evidenced that same neuro-type communication is more effective than across different neuro-type communication (Crompton et al., 2020; Davis and Crompton, 2021). As such, discussion of working arrangements that are considerate of autistic neuro-type requirements should be reflected upon prior to commencing research for mixed neuro-type teams (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al., 2023).

Accommodations may surpass the social aspects of research and relate to research activities. For instance, I personally experience auditory and language processing challenges and eye-tracking difficulties that makes transcribing interviews by hand challenging. Therefore, I require assistance from a transcription service to mitigate these difficulties. In recognition of the variation of support required among autistic people, each autistic researchers support needs will be personal to them and should be accommodated accordingly.

Principle 5-inclusion of participants

As per participatory principles, involving the community who are subject of research, elevates their collective voice to a position of authority on their own experiences (Aldridge, 2016), and increases the relevancy and impact of the research (Kaplan-Kahn and Caplan, 2023). The level of community participation will depend on the approach adopted and study design; however, scholars may find reference to Aldridge’s “Participatory Model,” a useful tool when considering different levels of participation (Aldridge, 2016. p. 156). However, it should also be noted that participation boundaries may not be as clearly defined in research, as they are on paper, and as such it may be helpful to consider participation as a continuum (Brown, 2021). Thus, regardless as to whether a full or partial participatory approach is adopted, it is beneficial to define and communicate responsibilities for all involved (Aldridge, 2016) including external partner roles (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). Further participatory considerations could include, reflecting on the role of data ownership and authorship (Wallis and Borgman, 2012) and evaluating power-dynamics between the researcher and participant (Aldridge, 2016; Nicolaidis et al., 2019) with consideration of how these dynamics inform the co-created research.

Principle 6-actionable outcomes

Research outcomes that inform the understanding, supports and life opportunities of autistic people should be central to an inclusive research design. In support of actionable research outcomes, I propose that the data collected with autistic participants is culturally and contextually appropriate (Barnes, 2004) and that the demographic criteria informing the research are explicitly stated (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2021). As emphasized in the introduction, autistic people face challenges across all aspects of society, thus research is required to progress understanding, inform support requirements, and improve the life opportunities for this demographic. Through consideration of specific contexts and demographic features, research outcomes can be easily compared across multiple articles and findings considered in relation to real-life contexts (Pellicano et al., 2014) thereby, improving the understanding of established literature as a means to identify research gaps and build on existing knowledge.

Principle 7-language choices

The choice of language used in research is an important consideration (Monk et al., 2022). Language has connotations that inform a specific way of thinking about autistic people (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021) and language associated with neurodiversity is very different to that of pathologizing medical terms (Walker, 2021). Thus, a reflexive approach to what language is used is beneficial. Evaluation of language could include reflecting on whether the language used, and messages portrayed, could be deemed “potentially offensive” to autistic people (Monk et al., 2022, p.791), and taking the time required to remove ableist and dated descriptors (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021). In addition to defining and consistently applying terms when adopting a neurodiversity perspective, thus assisting comprehension due to the developing nature of the associated language (Walker, 2021).

Principle 8-dissemination

The final principle to be discussed is dissemination of research. How findings are shared after the research has been published is an important reflexive consideration. It is beneficial to consider how research findings are accessible by the community who inform the study. As such, the demographic profile of the community should also inform how the findings are disseminated, with consideration given to minimizing stigma and harm (Nicolaidis et al., 2019). Dissemination of research can be achieved through varied and creative approaches. Ross-Hellauer et al. (2020) shares helpful considerations when planning dissemination of research, including but not limited to, reflecting on the aims and objectives of dissemination, promoting visibility of work, and considering creative formats, such as lay-summaries, blogs, diagrams, and talks.

Discussion

This paper recognizes that for epistemic progress to be made, the consolidation, innovation, and evaluation of current inclusive and participatory research approaches are required. Furthermore, how autistic researchers, community leaders and professionals are supported to lead research should be added to the range of inclusive considerations explored under this phenomenon. The “Eight Principles of Neuro-Inclusion” is presented in this paper as a tool to inform researcher reflexivity when conducting research with autistic communities. However, the principles are not directive and can be flexibly applied. As such, the same principles could be drawn upon to inform inclusive research with different neuro-types and more broadly across different disability groups.

In application of the reflexive approach presented in this paper, I hope that there will be a greater uptake and exploration of new inclusive ways of researching autistic communities. I conclude this commentary with a call for action. I believe that it will take a community effort for inclusive approaches to become mainstream consideration. However, if more scholars consolidate, innovate, and evaluate their approach to research, epistemic justice through appropriate representation of autistic people in research will materialize, leading to better life opportunities for our autism community across society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Writing−original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of the article. I received payment of doctoral fees through a Graduate Teaching Assistant contract (2020–2023) from the School of Business, Economics, and Informatics at Birkbeck, University of London.

Acknowledgments

This paper draws from my doctoral thesis on autism diagnosis disclosure in the workplace. A special mention goes to Penny Speller (Study Skills Tutor), and Dr. Kirsty Lauder (Peer Mentor), who provided me with grammar and structural support. Thanks also goes to Prof. Almuth McDowall, Birkbeck University of London, and Prof. Harriet Tenenbaum, University of Surrey, who provided support through supervision during doctoral study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aldridge, J. (2012). Working with vulnerable groups in social research: Dilemmas by default and design. Qual. Res. 14, 112–130. doi: 10.1177/1468794112455041

Aldridge, J. (2016). Participatory Research: Working with Vulnerable Groups in Research and Practice, 1st Edn. Bristol: Policy Press.

American Psychiatric Association [APA] (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association [APA] (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Apfelbaum, E. P., Phillips, K. W., and Richeson, J. A. (2014). Rethinking the baseline in diversity research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 235–244. doi: 10.1177/1745691614527466

Barnes, C. (2004). Emancipatory disability research: project or process? J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2002.00157.x

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Botha, M., Hens, K., O’Donoghue, S., Pearson, A., and Stenning, A. (2023). Cutting our own keys: New possibilities of neurodivergent storying in research. Autism 27, 1235–1244. doi: 10.1177/13623613221132107

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Kourti, M., Jackson-Perry, D., Brownlow, C., Fletcher, K., Bendelman, D., et al. (2019). Doing it differently: Emancipatory autism studies within a neurodiverse academic space. Disabil. Soc.? 34, 1082–1101. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2019.1603102

Botha, M., and Cage, E. (2022). Autism research is in crisis: A mixed method study of researcher’s constructions of autistic people and autism research. Front. Psychol. 13:1050897. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022f.1050897

Botha, M., Hanlon, J., and Williams, G. L. (2023). Does Language Matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to Vivanti. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 870–878. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., and Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers’. Autism Adulthood 3, 18–29. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Brown, N. (2021). Scope and continuum of participatory research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 45, 200–211. doi: 10.1080/1743727x.2021.1902980

Cascio, M. A., Weiss, J. A., and Racine, E. (2020). Making autism research inclusive by attending to intersectionality: A review of the research ethics literature. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 8, 22–36. doi: 10.1007/s40489-020-00204-z

Catala, A., Faucher, L., and Poirier, P. (2021). Autism, epistemic injustice, and epistemic disablement: A relational account of epistemic agency. Synthese 199, 9013–9039. doi: 10.1007/s11229-021-03192-7

Cooper, R., Cooper, K., Russell, A., and Smith, L. (2020). I’m Proud to be a little bit different: The effects of autistic individual’s perceptions of autism and autism social identity on their collective self-esteem. J Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 704–714. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04575-4

Crane, L., Hearst, C., Ashworth, M., and Davies, J. (2023). Evaluating the online delivery of an autistic-led programme to support newly diagnosed or identified autistic adults. Autism Dev. Lang. Impairments 8, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/23969415231189608

Crompton, C., Hallett, S., Ropar, D., Flynn, E., and Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism 24, 1438–1448. doi: 10.1177/1362361320919286

Davis, R., and Crompton, C. (2021). What do new findings about social interaction in autistic adults mean for neurodevelopmental research? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16, 649–653. doi: 10.1177/1745691620958010

De Jaegher, H. (2013). Embodiment and sense-making in autism. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 7, 1–19. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00015

D’Mello, A. M., Frosch, I. R., Li, C. E., Cardinaux, A. L., and Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2022). Exclusion of females in autism research: Empirical evidence for a “leaky” recruitment-to-Research Pipeline. Autism Res. 15, 1929–1940. doi: 10.1002/aur.2795

Draaisma, D. (2009). Stereotypes of autism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 364, 1475–1480. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0324

Ellard-Gray, A., Jeffrey, N., Choubak, M., and Crann, S. (2015). Finding the hidden participant. Int. J. Qual. Methods 14, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/1609406915621420

Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., et al. (2019). Making the Future Together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism 23, 943–953. doi: 10.1177/1362361318786721

Fletcher-Watson, S., Bölte, S., Crompton, C. J., Jones, D., Lai, M. C., Mandy, W., et al. (2021). Publishing standards for promoting excellence in autism research. Autism 25, 1501–1504. doi: 10.1177/13623613211019830

Flowers, J., Dawes, J., McCleary, D., and Marzolf, H. (2023). Words matter: Language preferences in a sample of autistic adults. Neurodiversity 1, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/27546330231216548

Gowen, E., Taylor, R., Bleazard, T., Greenstein, A., Baimbridge, P., and Poole, D. (2020). Guidelines for conducting research studies with the autism community. Autism Policy Pract. 2, 29–45.

Grant, A., and Kara, H. (2021). Considering the autistic advantage in qualitative research: The strengths of autistic researchers. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 16, 589–603. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2021.1998589

Gratton, F. V., Strang, J. F., Song, M., Cooper, K., Kallitsounaki, A., Lai, M. C., et al. (2023). The intersection of autism and transgender and nonbinary identities: Community and academic dialogue on research and advocacy. Autism Adulthood 5, 112–124. doi: 10.1089/aut.2023.0042

Gurbuz, E., Hanley, M., and Riby, D. M. (2019). University students with autism: The social and academic experiences of university in the UK. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 617–631. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3741-4

Hasson, L., Keville, S., Gallagher, J., Onagbesan, D., and Ludlow, A. K. (2022). Inclusivity in education for Autism Spectrum Disorders: Experiences of support from the perspective of parent/carers, school teaching staff and young people on the autism spectrum. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2022.2070418 [Epub ahead of print].

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., and Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? SSRN Electron. J. 139, 1–68. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1601785

Hewitt, O., Langdon, P. E., Tapp, K., and Larkin, M. (2023). A systematic review and narrative synthesis of inclusive health and social care research with people with intellectual disabilities: How are co-researchers involved and what are their experiences? J. Appl. Res. Intell. Disabil. 36, 681–701. doi: 10.1111/jar.13100

Hickman, L. (2022). Ways to make autism research more diverse and inclusive. Stamford, CO: Spectrum.

Jones, S. C. (2023). Advice for autistic people considering a career in academia. Autism 27, 2187–2192. doi: 10.1177/13623613231161882

Kaplan-Kahn, E. A., and Caplan, R. (2023). Combating stigma in autism research through centering autistic voices: A co-interview Guide for Qualitative Research. Front. Psychiatry 14:1248247. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1248247

König, A., Hatzakis, T., Andrushevich, A., Hoogerwerf, E.-J., Vasconcelos, E., Launo, C., et al. (2022). A reflection on participatory research methodologies in the light of the COVID-19 – lessons learnt from the European Research Project TRIPS. Open Res. Europe 1:153. doi: 10.12688/openreseurope.14315.2

Leedham, A., Thompson, A., Smith, R., and Freeth, M. (2019). I was exhausted trying to figure it out: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism 24, 135–146. doi: 10.1177/1362361319853442

Lewis, K., Hamilton, L. G., and Vincent, J. (2023). Exploring the experiences of autistic pupils through creative research methods: Reflections on a participatory approach. Infant Child Dev. doi: 10.1002/icd.2467 [Epub ahead of print].

Malone, K. M., Pearson, J. N., Palazzo, K. N., Manns, L. D., Rivera, A. Q., and Mason-Martin, D. L. (2022). The scholarly neglect of black autistic adults in autism research. Autism Adulthood 4, 271–280. doi: 10.1089/aut.2021.0086

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The double empathy problem. Disabil. Soc. 27, 883–887. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Monk, R., Whitehouse, A. J. O., and Waddington, H. (2022). The use of language in autism research. Trends Neurosci. 45, 791–793. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2022.08.009

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., Kapp, S. K., Baggs, A., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K., et al. (2019). The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism 23, 2007–2019. doi: 10.1177/1362361319830523

North, G. (2021). Reconceptualising reasonable adjustments for the successful employment of autistic women. Disabil. Soc. 38, 944–962. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2021.1971065

Oakley, B., Tillmann, J., Ruigrok, A., Baranger, A., Takow, C., Charman, T., et al. (2021). Covid-19 health and Social Care Access for autistic people and individuals with intellectual disability: A European Policy Review. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 45, 200–2011.

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., and Charman, T. (2014). What should autism research focus upon? community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism 18, 756–770. doi: 10.1177/1362361314529627

Ross-Hellauer, T., Tennant, J. P., Banelytė, V., Gorogh, E., Luzi, D., Kraker, P., et al. (2020). Ten simple rules for innovative dissemination of research. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007704

The Autism Employment Gap (2021). New shocking data highlights the autism employment gap. Available online at: https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/news/new-data-on-the-autism-employment-gap (Accessed January 19, 2024).

Thompson-Hodgetts, S. (2022). Reflections on my experiences as a non-autistic autism researcher. Autism 27, 259–261. doi: 10.1177/13623613221121432

Walker, N. (2021). Neuroqueer Heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Fort Worth: Autonomous Press.

Keywords: autism, autistic researcher, inclusive methods, neurodiversity, participatory research

Citation: Dark J (2024) Eight principles of neuro-inclusion; an autistic perspective on innovating inclusive research methods. Front. Psychol. 15:1326536. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1326536

Received: 23 October 2023; Accepted: 31 January 2024;

Published: 27 February 2024.

Edited by:

Louise A. Brown Nicholls, University of Strathclyde, United KingdomReviewed by:

David Giofrè, University of Genoa, ItalySarah O’Kelley, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Copyright © 2024 Dark. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessica Dark, amVzc2ljYUBqZXNzaWNhZGFyay5jby51aw==

Jessica Dark

Jessica Dark