- 1Shanghai Changning Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China

- 2School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

- 3Zhuhai No. 2 High School, Zhuhai, China

- 4Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Introduction: There have been studies indicating that children’s unsociability was associated with poorer socio-emotional functioning in China. Although some researchers have found that parenting behavior would influence the relationship between children’s unsociability and adjustment, the role of parental psychological control has not been explored. This study aimed to investigate the moderating effect of parental psychological control on the relationship between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning in Chinese children.

Methods: A total of 1,275 students from Grades 3 to 7 (637 boys, Mage = 10.78 years, SD = 1.55 years) were selected from four public schools in Shanghai to participate in this study. Data of unsociability, peer victimization and social preference were collected from peer-nominations, and data of parental psychological control, depressive symptoms and social anxiety were collected from self-reports.

Results: There were positive associations between unsociability and peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and social anxiety, as well as a negative association between unsociability and social preference. Parental psychological control moderated these associations, specifically, the associations between unsociability and peer victimization, social preference, and depressive symptoms were stronger, and the association between unsociability and social anxiety was only significant among children with higher level of parental psychological control.

Discussion: The findings in the current study highlight the importance of parental psychological control in the socio-emotional functioning of unsociable children in the Chinese context, enlightening educators that improving parenting behavior is essential for children’s development.

Introduction

Social withdrawal refers to the process by which individuals refrain themselves from opportunities to interact with peers and frequently exhibit solitary behaviors in social contexts (Rubin and Coplan, 2004). According to the social approach-avoidance motivation model, there are two opposing motivational tendencies, social approach and social avoidance, and different combinations of them contribute to three subtypes of social withdrawal, including shyness, unsociability, and social avoidance (Asendorpf, 1990). Among these three subtypes of social withdrawal, unsociability is characterized by both low social approach and low social avoidance motivational tendencies, which differentiates it from shyness (i.e., high social approach and high social avoidance motivational tendencies) and social avoidance (i.e., low social approach and high social avoidance motivational tendencies). It has been found that the associations between different subtypes of social withdrawal and psychosocial adjustment were different (Coplan et al., 2015).

Unsociability is described as a non-fearful preference for solitary activities (Coplan and Armer, 2007). Previous studies have found that compared to in individualistic societies, children might experience higher adjustment difficulties in collectivistic societies (Rubin and Coplan, 2004; Liu et al., 2015), where group affiliation and social connectedness are highly valued (Chen, 2009). For example, there have been studies indicating that unsociability was associated with psychosocial maladjustment (e.g., depressive symptoms, loneliness and peer victimization) for children in China (Ding et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2023), where collectivism is the mainstream value (Chen, 2010). Given the possible risk of psychosocial adjustment among unsociable children in China, an important question arises as to whether certain factors may exacerbate or protect these children from developing maladjustment. Although there have been studies indicating that parents’ characteristics or behavior would influence the relationship between unsociability and children’s adjustment (Chen and Santo, 2016; Zhu et al., 2021), the role of parental psychological control, which is defined as parents’ control of their children’s inner state or behavior through love withdrawal, guilt induction or shaming (Yu et al., 2015), has not been explored. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore if parental psychological control would play a role in the relationship between children’s unsociability and socio-emotional functioning.

Unsociability and socio-emotional functioning in Chinese children

According to the social learning perspective proposed by Hartup (1983), children acquire social skills and accomplish developmental tasks through interacting with peers. Given that unsociable children have low social approach motivational tendencies, they may experience inadequate peer interaction (Youniss, 1980; Rubin and Mills, 1988), which in turn increases their risk of socio-emotional difficulties (Rubin et al., 2009). However, given unsociability may be regarded as a personal choice and freedom in western societies, where individualism is the core value (Chen, 2019), it may have less negative influence on children’s adjustment in western societies. It has been found that unsociability was positively associated with attention span, and negatively associated with indexes of emotion dysregulation in western countries (Coplan et al., 2004). In contrast, in collectivist cultures, unsociability is viewed as deviating from the social values of group affiliation and belonging (Liu et al., 2017; Zhang and Eggum-Wilkens, 2018). Indeed, there have been studies indicating that unsociability was associated with negative developmental outcomes in Chinese children (Ding et al., 2015; Bullock et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2021). A cross-national study has demonstrated that the associations between unsociability and children’s maladjustment were stronger in China than in Canada (Liu et al., 2015).

The relationship between psychological control and children’s socio-emotional functioning

Given that group affiliation is a big concern when it comes to measuring social adjustment in China, Chinese parents may experience more stress when dealing with unsociable children in China. It has been found that parents tended to adopt less authoritative and more authoritarian parenting behavior toward their own child (Zhu et al., 2021). Psychological control is a parenting style in which parents use forms of psychological pressure and manipulation to control their children’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Barber and Harmon, 2002). According to Self-determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000), individuals have three kinds of basic psychological needs, including needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Moreover, satisfaction of basic psychological needs can strengthen intrinsic motivation and internalization of extrinsic motivation in activities, contributing to people’s adjustment and development. However, parental psychological control is conflicted with children’s basic psychological needs. Previous studies have found that parents’ practice of psychological control is linked to children’s development of internalizing problems and social maladjustment (Barber and Harmon, 2002; Yu et al., 2015). Research from Western cultures has consistently shown that psychological control was associated with negative developmental outcomes, including depressive symptoms and anxiety among children and adolescents (Barber et al., 2005).

In contrast to the implied manipulative and authoritarian connotation of psychological control in Western societies, in China, parents usually consider psychological control as a necessary method to guide children to behave in ways that are consistent with the society’s value (Fung, 1999). This may be because in traditional Chinese culture, it is believed that children should show obedience and respect to their own parents (Liu et al., 2018), therefore parents’ behavior of control is regarded as a type of “training” for their children’s development (Chao, 1994). Despite this, growing evidence has indicated that psychological control was also linked to adjustment problems among children in East Asian contexts (Yu et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017). There has been a recent study of need-supportive parenting program, showing that children would be more willing to participating in physical activities when their parents gave more support for their psychological need rather than controlling them (Meerits et al., 2023). As such, it is essential to explore the negative effect of parental psychological control, and reduce it in the real life.

Theory foundation

According to the Goodness of Fit Theory (Thomas and Chess, 1977), children would have optimal developmental outcomes when their temperament is a good match for their parents’ parenting style. Given that unsociable children are characterized as preferring for solitary activities (Coplan and Armer, 2007), they may enjoy individual freedom and be reluctant to be restricted by others. As such, it can be speculated that for unsociable children, who have a higher need for autonomy, high parental psychological control is more detrimental for their adjustment than other children. It has been found that children’s unsociability would contribute to more adjustment problems, including peer exclusion, asocial behavior and anxious-fearful behavior when their parents adopted more authoritarian parenting behavior (Zhu et al., 2021). Moreover, it has been found that shy children would suffer from more internalizing problems or peer difficulties when they perceived higher parental psychological control (Bullock et al., 2018). However, as different subtypes of social withdrawal, children of unsociability have different social motivational tendencies compared to their peers of shyness. Therefore, it is essential to explore the role of parental psychological control in their adjustment and development.

The present study

The primary aim of the present study was to explore the moderating effect of parental psychological control on the relationship between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning among Chinese children. Based on existing theoretical and empirical literature, we hypothesized that unsociability would be associated with socio-emotional problems. Furthermore, we speculated that parental psychological control would moderate the links between children’s unsociability and socio-emotional difficulties. Specifically, we anticipated that unsociability would have stronger associations with indices of socio-emotional difficulties among children who perceived higher level of parental psychological control. Given that previous research has found that the negative influence of unsociability on socio-emotional functioning might be more pronounced in boys than in girls (Liu et al., 2014), and in early adolescence than in childhood (Coplan et al., 2019), gender and grade were included in the models as control variables.

Materials and methods

Participants

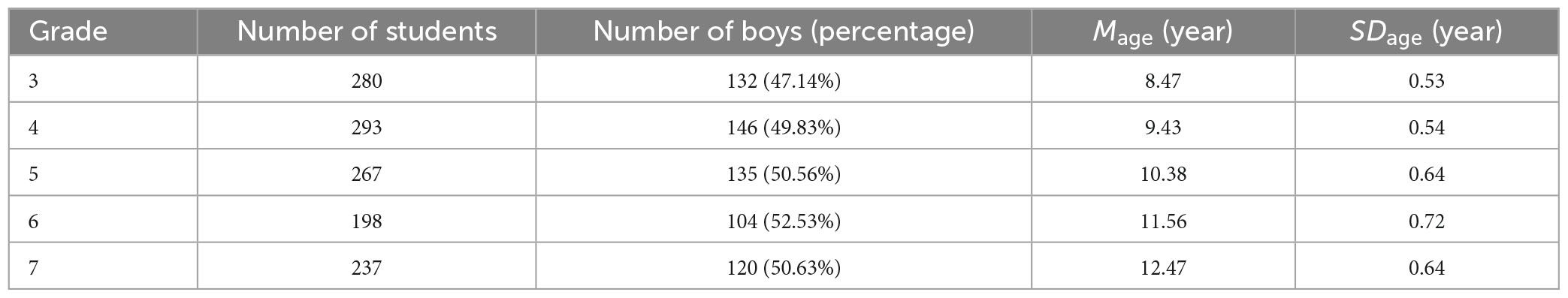

Participants in current study were recruited from two primary schools and two secondary schools in Shanghai, People’s Republic of China. The total sample is comprised of 1,275 students (637 boys, 50% of all students) with a mean age of 10.78 years (SD = 1.55 years). The students were from Grades 3 to 7, and the information of students from different grades was displayed in Table 1. Almost all participating students were of Han nationality, which is the predominant nationality (over 90% of the population) in China (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2018). Moreover, 94% of participants were from intact families, and approximately 49% of fathers and 40% of mothers had obtained a college education or higher.

Procedure

We conducted our original research by following steps. The design of the present study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of East China Normal University, and written informed consent was obtained from both participating students and their parents prior to data collection. During school hours, participating children completed self-report measures assessing their levels of depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and perceived paternal and maternal psychological control. These children also completed peer-nomination assessments, which included measures on unsociability, victimization, and social preference. The data collection process was carried out by a team of well-trained graduate research assistants, and each child was given a class list for the purpose of finishing the peer-nomination assessments more smoothly. The duration of the data collection process was approximately 30 min. To ensure the confidentiality of the participants’ responses, we assured them that their answers would be kept confidential. As a token of appreciation, each participating student received a small gift after submitting their completed questionnaire. The current study was conducted in 2013.

Measures

Unsociability

Children’s unsociability was measured by the Revised Class Play (RCP; Masten et al., 1985; Chen, 1992) via peer nominations. Four items (e.g., “Someone who prefers playing alone,” “Someone who is reluctant to talking with others”) were included in this part. Each participant could nominate up to three classmates on each item, and as suggested by Terry and Coie (1991), both same-sex and cross-sex nominations were allowed. For each child, the nominations received on each item were standardized within classroom and summed, and standardized within classroom again to obtain the score of unsociability. This RCP measure have proved to be reliable and valid among Chinese children (Liu et al., 2014). In the present study, the internal consistency of this measure was α = 0.86.

Peer victimization

Peer victimization was assessed via peer nominations (Schwartz et al., 2001). Children nominated up to three peers to fit each of the seven items, which described physical victimization (e.g., “Someone who is always beat by others”), verbal victimization (e.g., “Someone who is always called names by others”) and relational victimization (e.g., “Someone others do not talk to”). For each child, the nominations received on each item were standardized within classroom and summed, and standardized within classroom again to obtain the score of peer victimization. The reliability and validity of this measure have been established in Chinese children (Liu et al., 2018). The internal consistency of this measure was α = 0.86 in this study.

Social preference

Following the procedure of Coie et al. (1982), each child was asked to nominate up to three classmates whom they most liked, and whom they least like in their classroom, respectively. The index of social preference was calculated by subtracting the standardized score of “like least” from the standardized score of “like most,” and standardizing the total score within classroom again. This measure has been demonstrated suitable for Chinese children (Chen et al., 1995).

Depressive symptoms

The level of depressive symptoms was measured using the Chinese version of Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) via self-report. The CDI is comprised of 14 items that assess children’s depressive mood over the past 2 weeks. Participants were instructed to choose one sentence which best described their own internal state (e.g., “I like myself,” “I do not like myself,” “I hate myself”). The items were rated on a 3-point scale, with a higher average score indicating a higher level of depressive symptoms. This measure has been shown to be reliable and valid in Chinese children (Liu et al., 2019). In the current study, the internal consistency of this measure was α = 0.83.

Social anxiety

Children’s level of social anxiety was assessed using the Chinese version of Social Anxiety Scale for Children-Revised (SASC-R; La Greca and Stone, 1993) via self-report. The scale consisted of 15 items that measured fear of negative evaluation (e.g., “I worry about what other kids think of me”), social avoidance and distress to new peers or situations (e.g., “I get nervous when I talk to new kids”), and general social avoidance and distress (e.g., “I am quiet when I am with a group of kids”), respectively. Participants rated their response on a five-point Likert scale, with higher average scores indicating greater level of social anxiety. The reliability and validity of this measure have been demonstrated in Chinese children (Gao et al., 2022). In the current study, the internal consistency of this measure was α = 0.90.

Parental psychological control

Children reported on how often their mothers and fathers engage in psychologically controlling parenting on a five-point Likert scale (Yu et al., 2015). The scale consisted of 18 items that measure love withdrawal (e.g., “My father/mother would avoid looking at me when I disappointed him/her”), guilt induction (e.g., “My father/mother would make me aware of how much he/she sacrificed or did for me”) and shaming of children (e.g., “My father/mother would tell me that I should be ashamed when I misbehaves”). Given that the paternal and maternal psychological control were highly correlated (r = 0.81, p < 0.001), we averaged mother’s and father’s data of each child to form the indicator of parental psychological control. Previous studies have proved that this measure was reliable and valid for Chinese children (Bullock et al., 2018). In the current study, the internal consistency of this measure was α = 0.91.

Data analysis

We handled the missing data by the full information maximum likelihood method (Graham, 2009) with the MLR estimation in Mplus 7.4. The steps of analyzing data were as follow. To begin with, we conducted descriptive statistics using IBM SPSS for Windows (version 25). The Pearson correlation coefficients among the study variables were calculated. Additionally, we conducted a two-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and four two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) to examine the effects of gender (boys = 0, girls = 1) and grade (primary school = 0, secondary school = 1) on the study variables. Next, we used Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 2012) to conduct moderation analyses for peer victimization, social preference, depressive symptoms and social anxiety, respectively. Finally, the simple slope test would be conducted (Aiken and West, 1991) when significant moderating effect was found. Parental psychological control, gender and grade were grand-mean centered before the data analysis.

Results

Missing data

For the self-reported variables, which included depressive symptoms, social anxiety and parental psychological control, the percentage of missing data was 3.5, 3.5, and 3.2%, respectively. The Little’s MCAR test (Little, 1988) was significant [χ2(9977) = 12116.21, p < 0.001]. However, following Ulman (2013) recommendation, χ2/df = 1.21 < 2, suggesting that the missing data can be considered missing completely at random.

Descriptive statistics

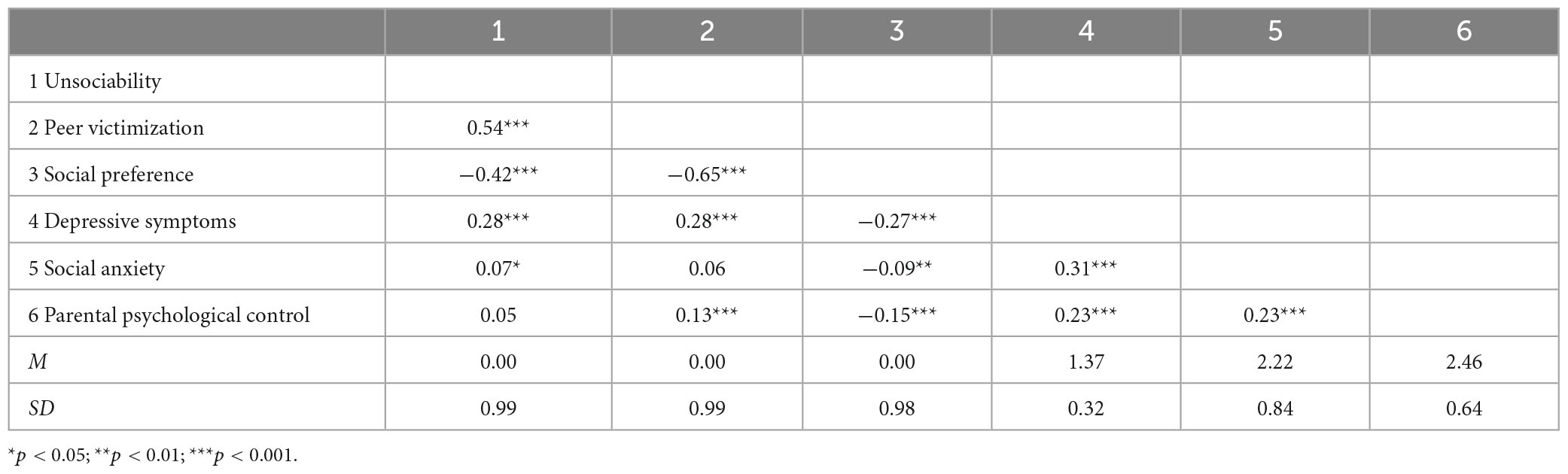

The intercorrelations, means and standard deviations of study variables are shown in Table 2. Unsociability was positively associated with peer victimization, depressive symptoms and social anxiety, and negatively associated with social preference. Parental psychological control was positively associated with peer victimization, depressive symptoms and social anxiety, and negatively associated with social preference.

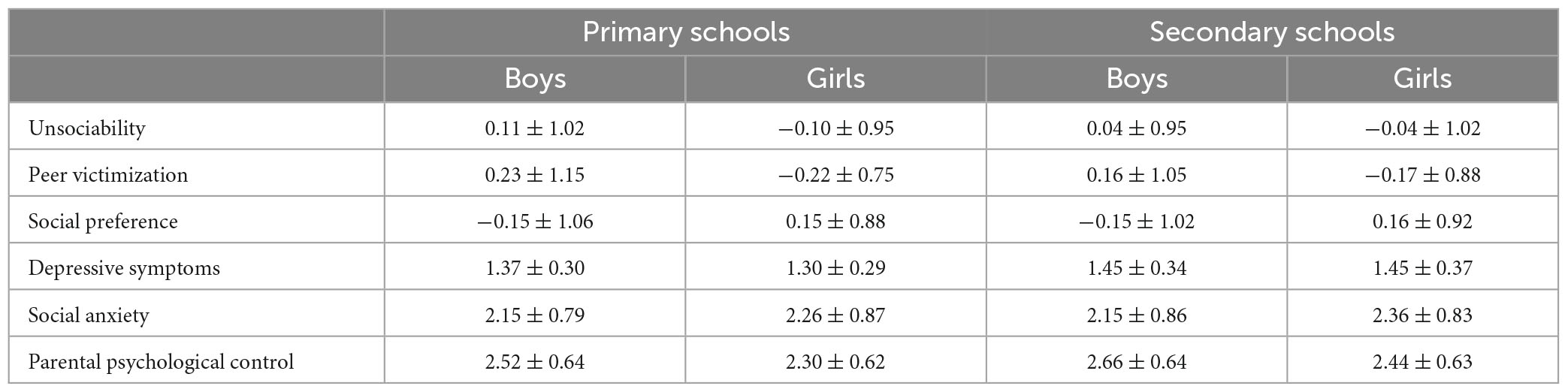

The multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed significant main effect of gender [Wilk’s λ = 0.93, F(6, 1187) = 15.00, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.07] and grade [Wilk’s λ = 0.96, F(6, 1187) = 8.17, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.04]. However, the interaction between gender and grade was not significant. Further analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that girls scored higher on social preference[F(1, 1261) = 27.18, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.02] and social anxiety [F(1, 1226) = 10.18, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.01], but scored lower on unsociability [F(1, 1261) = 6.30, p = 0.012, partial η2 = 0.01], peer victimization [F(1, 1261) = 45.01, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.03] and parental psychological control [F(1, 1230) = 33.61, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.03] than boys, and students from primary school scored lower on depressive symptoms [F(1, 1227) = 38.13, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.03] and parental psychological control [F(1, 1230) = 13.57, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.01] compared to students from secondary school. The means and standard deviations of study variables of different gender and grade are shown in Table 3.

Moderation analyses

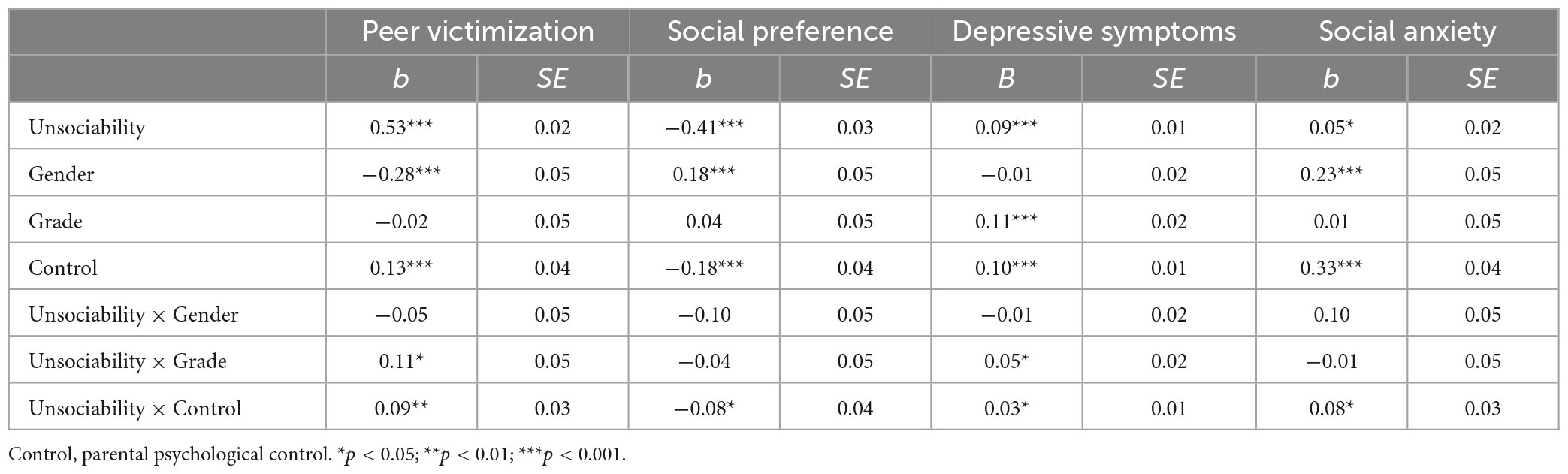

Moderating effects of parental psychological control on the relationships between unsociability and each indicator of socio-emotional adjustment were examined. The results are shown in Table 4.

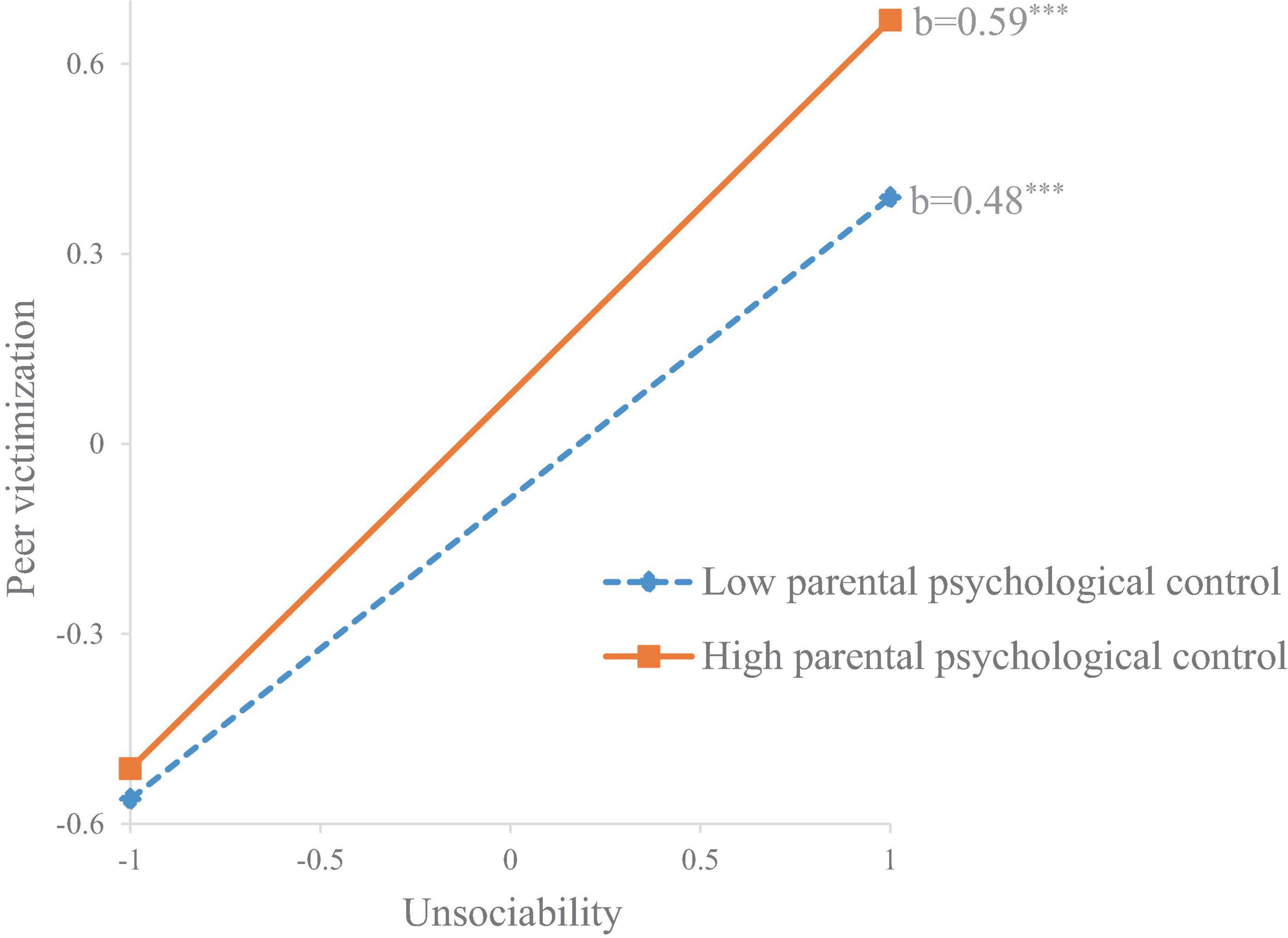

In terms of peer victimization, the finding indicated that parental psychological control had a significant moderating effect on the positive association between unsociability and peer victimization (b = 0.09, SE = 0.03, p = 0.008). Specifically, this association was stronger when children perceived higher parental psychological (M + 1 SD) (b = 0.59, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) than when they perceived lower parental psychological control (M–1 SD) (b = 0.48, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) (see Figure 1). Additionally, grade was found to significantly moderate the association between unsociability and peer victimization (b = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = 0.021). Specifically, this association was stronger in students from secondary schools (b = 0.61, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001) compared to students from primary schools (b = 0.49, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). The moderating effect of gender was insignificant.

Figure 1. The moderating effect of parental psychological control on the association between unsociability and peer victimization. ***p < 0.001.

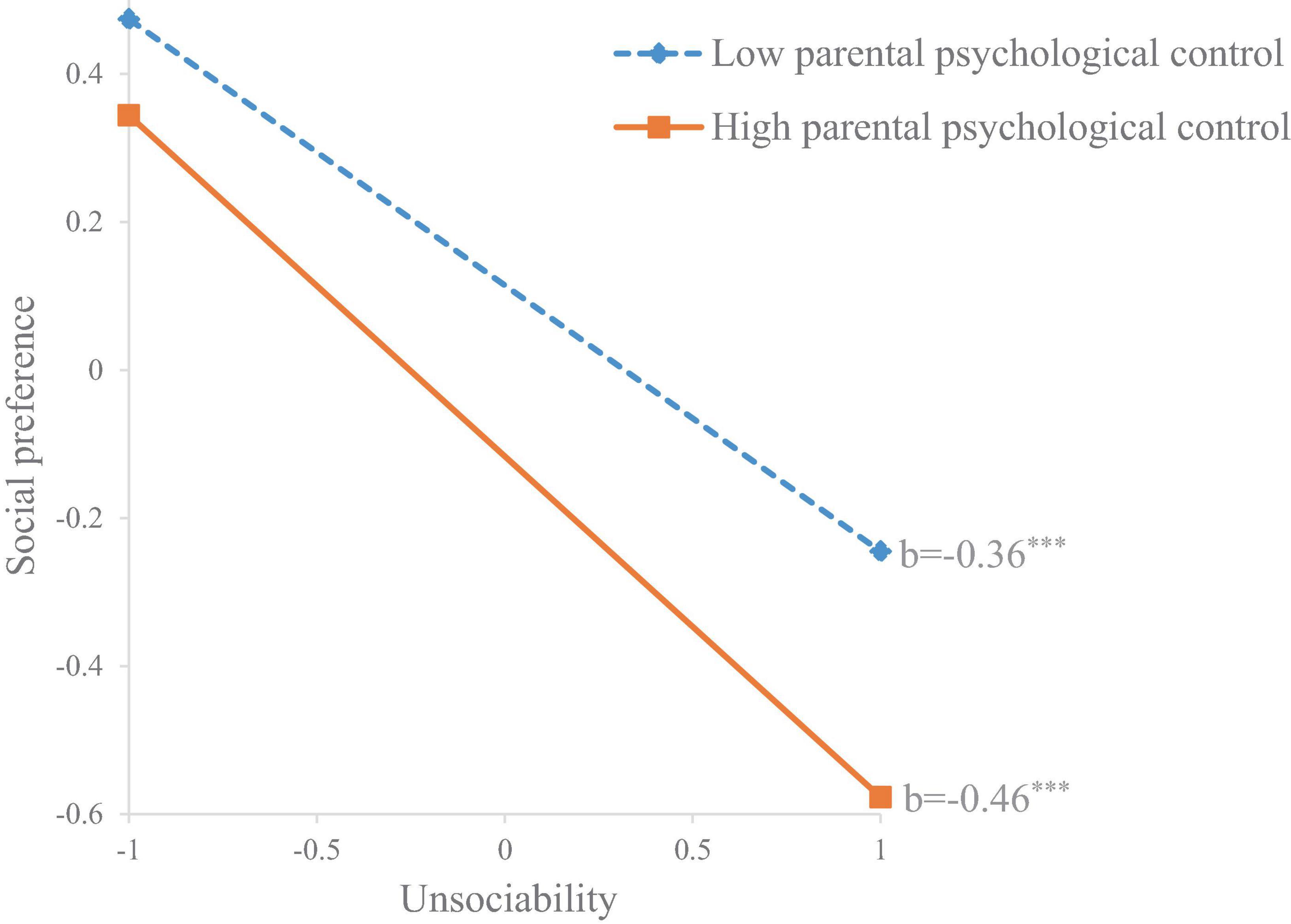

For social preference, parental psychological control also moderated the significant negative association between unsociability and social preference (b = −0.08, SE = 0.04, p = 0.033). Specifically, this association was stronger in children who perceived higher parental psychological (b = −0.46, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001) compared to those who perceived lower parental psychological control (b = −0.36, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001) (see Figure 2). The moderating effects of gender and grade were insignificant.

Figure 2. The moderating effect of parental psychological control on the association between unsociability and social preference. ***p < 0.001.

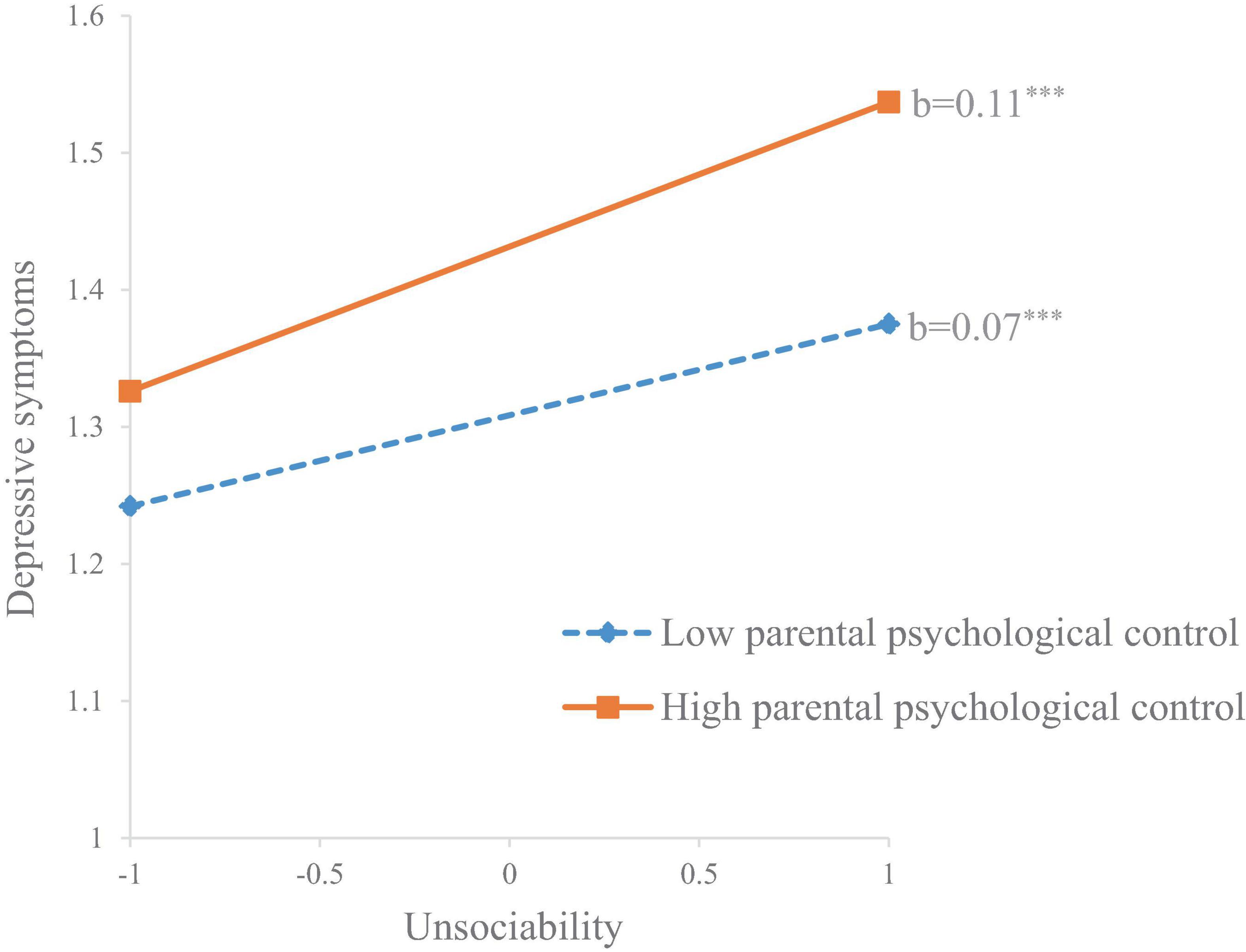

For depressive symptoms, parental psychological control also moderated the positive association between unsociability and depressive symptoms (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p = 0.013). Specifically, this association was stronger in children who perceived higher parental psychological (b = 0.11, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) compared to those who perceived lower parental psychological control (b = 0.07, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) (see Figure 3). Additionally, grade was found to significantly moderate the association between unsociability and depressive symptoms (b = 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = 0.012). Specifically, this association was stronger in students from secondary schools (b = −0.12, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001) compared to students from primary schools (b = 0.07, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001). The moderating effect of gender was insignificant.

Figure 3. The moderating effect of parental psychological control on the association between unsociability and depressive symptoms. ***p < 0.001.

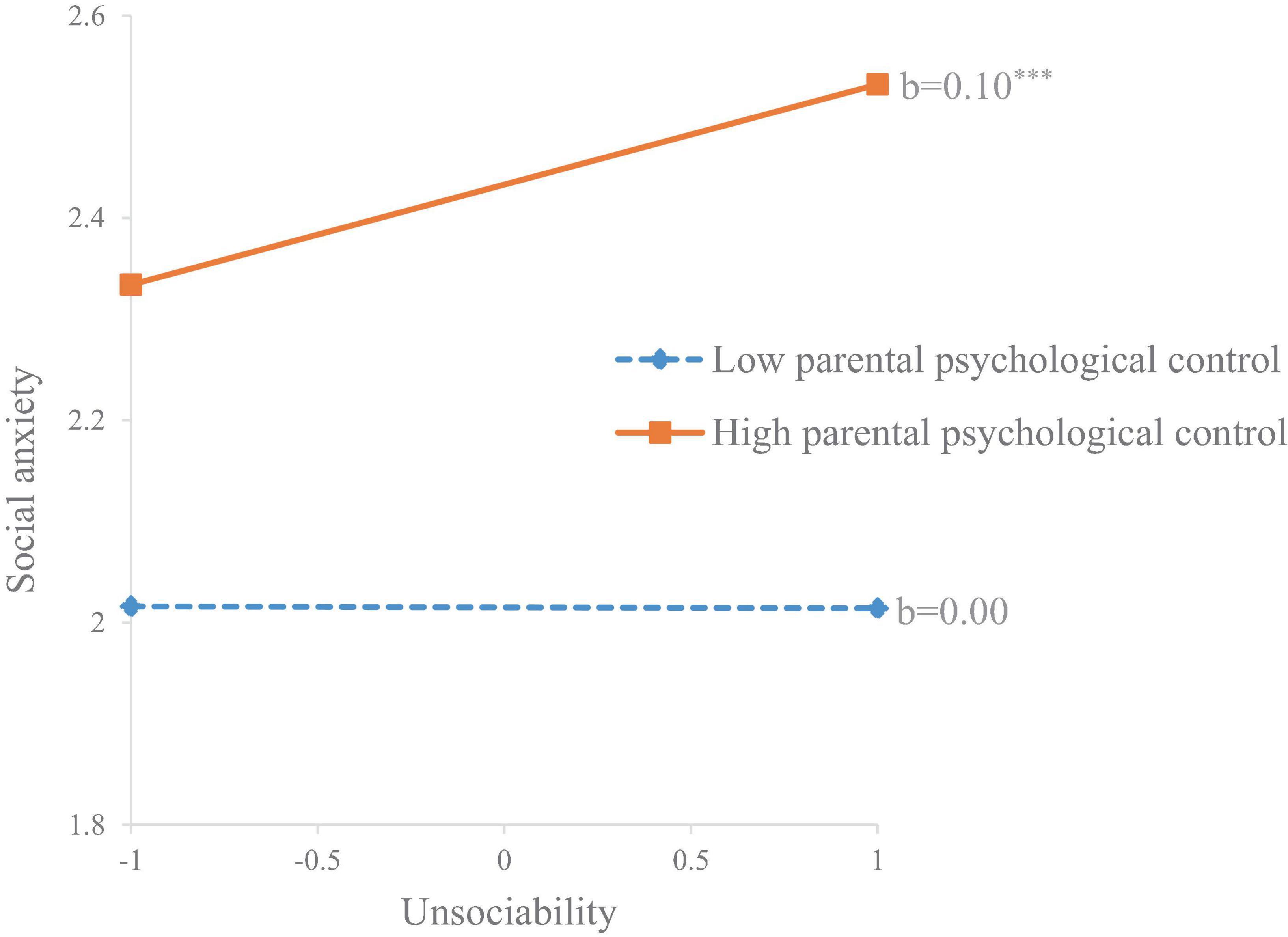

For social anxiety, parental psychological control also moderated the positive association between unsociability and social anxiety (b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, p = 0.023). Specifically, this association was only significant when children perceived higher parental psychological (b = 0.10, SE = 0.03, p = 0.001) rather than when they perceived lower parental psychological control (b = 0.00, SE = 0.04, p = 0.984) (see Figure 4). The moderating effects of gender and grade were insignificant.

Figure 4. The moderating effect of parental psychological control on the association between unsociability and social anxiety. ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the association between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning in Chinese children, and to explore the potential moderating effect of parental psychological control on this relationship. Our findings first supported the hypothesis that unsociability is associated with adjustment problems in urban China today. Furthermore, parental psychological control was found to moderate the relationship between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning. Specifically, our results showed that unsociable behaviors of children are linked more profoundly to peer victimization and low preference by peers when children perceived higher levels of psychological control from their parents. Similarly, our results also indicated that unsociability is associated more closely with internalizing outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms and social anxiety) in children with higher levels of parental psychological control compared to children whose parents are less controlling. These results have important implications for understanding the role of parental psychological control in the relationship between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning in Chinese children.

The moderating effects of parental psychological control on unsociable children’s socio-emotional functioning

It is well established that unsociability is associated with less prosocial behaviors and lower social interactive skills (Rubin et al., 2009), contributing to children’s poor developmental outcomes. In China, a country where children who are not interested in group interactions would be regarded as selfish and deviant (Liu et al., 2017), unsociable children were found to be more susceptible to internalizing problems (Bullock et al., 2020) as well as peer difficulties (Liu et al., 2014). The results in our study further highlight this phenomenon.

Our findings are consistent with previous research that highlighted the importance of favorable parenting style in improving mental health and reducing the risk of socio-emotional difficulties among socially withdrawn children and youths (Degnan and Fox, 2007; Zarra-Nezhad et al., 2014). Parental psychological control is a dimension of parenting style that can impact children’s socio-emotional development. A high level of psychological control, characterized by behaviors such as manipulation, guilt induction, and love withdrawal (Barber, 1996), may increase the risk of youths’ problem behaviors (Yan et al., 2020). The perspective of social support may explain for why parental psychological control would strengthen the associations between children’s unsociability and maladjustment. Seeking social support is one type of coping strategies while confronting with difficulties (Causey and Dubow, 1992), and there have been studies indicating that social support from others (e.g., parents, friends and teachers) was beneficial for children’s adjustment in school (Rueger et al., 2010; Fan and Fan, 2021). It has been found that friend’s support could weaken the associations between unsociability and internalizing problems (Barstead et al., 2018). However, for unsociable children who are characterized as preferring spending time alone (Coplan and Armer, 2007), they may lack social support from their friends, and support from their parents may compensate for it. Therefore, compared to other children, unsociable children may have a stronger need of their parents’ support. Moreover, according to Goodness of Fit Theory (Thomas and Chess, 1977), unsociable children may be more sensitive to controlling parenting behavior because of their own temperament. Influenced by parental psychological control, such an unsupportive parenting style, unsociable children would feel depressed and anxious in their daily lives. Furthermore, they can’t learn social skills from their parents of high controlling parenting behavior, thus it is hard for them to build good relationships with others, which may explain why they had higher level of peer victimization and lower level of social preference when they perceived high parental psychological control.

Our study also shows that age moderates the associations between unsociability and peer victimization and depressive symptoms, with a stronger relationship observed in secondary schools than primary schools. The possible reason might be many other factors outside of family settings, such as peer or teacher, have a growing impact on children as they enter adolescence (Lamblin et al., 2017). Indeed, the social expectations of having more peer interactions increase at peak in early adolescence (Coplan et al., 2019). Therefore, compared to primary school students, secondary school students’ unsociable behavior may be regarded as more unacceptable, because they violate the recognized social norm. As a result, secondary school students are more likely to be excluded by their peers and suffer from socio-emotional difficulties if they have high level of unsociability.

Limitations and future directions

The present study provided insights on the role of parental psychological control in the links between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning among Chinese children. Nevertheless, there are several limitations to this study. First, our study was cross-sectional in nature and it was hard to infer the results of causalities. Future research can utilize longitudinal research with multiple waves to further infer causal effects. Second, children’s unsociability was assessed through peer nominations (Chen, 1992). Given that unsociability was characterized as a combination of low social-approach motivational tendency and low social-avoidance tendency (Asendorpf, 1990), peer nominations of it may not reflect children’s own motivation. Future research can measure children’s unsociability through self-report. Third, parental psychological control was measured via children’s self-reports (Yu et al., 2015), which might not fully reflect actual parenting behavior. Future research should evaluate parental psychological control through observational methods and gather data from parents’ reports. Fourth, some coefficients in the results are significant but small, probably because the sample size of the current study is large. Therefore, the explanation of the results should be cautious. Finally, our study was conducted in Shanghai, a large city in China. Due to the huge differences in the rural and urban areas in China, the results might not be applicable to rural areas. Moreover, the applicability of the results should be also examined in western countries, where parental psychological control may exert different influence.

Despite these limitations, our study reveals the moderating role of parental psychological control between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning among children. For theoretical implications, the results indicate that parental psychological control, a common parenting style in Eastern Asian cultures, might impact children’s adjustment and development in a more subtle and nuanced way. Moreover, the results also suggest that unsociable children and youth could be more susceptible to controlling parenting. For the practical implications, the current study can inform school educators when they hold parenting workshops. In these parenting workshops, educators are encouraged to inform parents that it is important to focus on their children’s psychological needs, such as need for autonomy and need for relatedness, and provide more support for them rather than exhibiting need-thwarting behavior (Ahmadi et al., 2023), especially in China, where controlling parenting behavior is regarded as relative normal and effective. Moreover, society and school can highlight the importance of supporting parents of unsociable children, as their behaviors seemed to have a more profound impact on their children’s adaptation.

Conclusion

This study was aimed at exploring the moderating effect of parental psychological control on the relationship between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning in Chinese children. In the sample of the study, unsociability had a significant positive association with peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and social anxiety, as well as a significant negative association with social preference. The moderating effect of parental psychological control was significant on all of four associations. Specifically, the associations between unsociability and peer victimization, social preference, and depressive symptoms were stronger, and the association between unsociability and social anxiety was only significant among children with higher level of parental psychological control. The results indicated that parental psychological control was a risk factor for unsociable children’s adjustment in China.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Review Board at East China Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

HZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft. YH: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. YC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. RL: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review and editing. NW: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review and editing. XC: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. TC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. JL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Research Project of Changning District Science and Technology Committee (CNKW2022Y37), the Medical Master’s and Doctoral Innovation Talent Base Project of Changning District (RCJD2022S07) and the Changning District Health of Medical Specialty (Grant No: 20232005).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmadi, A., Noetel, M., Parker, P., Ryan, R. M., Ntoumanis, N., and Reeve, J. (2023). A classification system for teachers’ motivational behaviors recommended in self-determination theory interventions. J. Educ. Psychol. 115, 1158–1176. doi: 10.1037/edu0000783

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Asendorpf, J. B. (1990). Beyond social withdrawal: shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Hum. Dev. 33, 250–259. doi: 10.1159/000276522

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 67, 3296–3319. doi: 10.2307/1131780

Barber, B. K., and Harmon, E. L. (2002). “Violating the self: parental psychological control of children and adolescents,” in Intrusive Parenting. How Psychological Control Affects Children and Adolescents, ed. B. K. Barber (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 15–52. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0106-8

Barber, B. K., Stolz, H. E., Olsen, J. A., Collins, W. A., and Burchinal, M. (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 70, 1–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x

Barstead, M. G., Smith, K. A., Laursen, B., Booth-LaForce, C., King, S., and Rubin, K. H. (2018). Shyness, preference for solitude, and adolescent internalizing: the roles of maternal, paternal, and Best-Friend support. J. Res. Adolesc. 28, 488–504. doi: 10.1111/jora.12350

Bullock, A., Liu, J., Cheah, C. S., Coplan, R. J., Chen, X., and Li, D. (2018). The role of adolescents’ perceived parental psychological control in the links between shyness and socio-emotional adjustment among youth. J. Adolesc. 68, 117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.007

Bullock, A., Xiao, B., Xu, G., Liu, J., Coplan, R., and Chen, X. (2020). Unsociability, peer relations, and psychological maladjustment among children: a moderated-mediated model. Soc. Dev. 29, 1014–1030.

Causey, D. L., and Dubow, E. F. (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 21, 47–59. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2101_8

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 65, 1111–1119. doi: 10.2307/1131308

Chen, B., and Santo, J. B. (2016). The relationships between shyness and unsociability and peer difficulties: the moderating role of insecure attachment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 40, 346–358. doi: 10.1177/0165025415587726

Chen, X. (1992). Social reputation and peer relationships in Chinese and Canadian children: a cross-cultural study. Child Dev. 63, 1336–1343. doi: 10.2307/1131559

Chen, X. (2009). “Culture and early socio-emotional development,” in Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, eds R. E. Tremblay, R. G. Barr, R. De, V. Peters, and M. Boivin (Montreal: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development), 1–6.

Chen, X. (2010). “Shyness-inhibition in childhood and adolescence: a cross-cultural perspective,” in The Development of Shyness and Social Withdrawal, eds K. H. Rubin and R. J. Coplan (New York: The Guilford Press), 213–235.

Chen, X. (2019). Culture and shyness in childhood and adolescence. New Ideas Psychol. 53, 58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.04.007

Chen, X., Rubin, K. H., and Li, Z.-Y. (1995). Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: a longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 31, 531–539. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.4.531

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., and Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: a cross-age perspective. Dev. Psychol. 18, 557–570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557

Coplan, R. J., and Armer, M. (2007). A “multitude” of solitude: a closer look at social withdrawal and nonsocial play in early childhood. Child Dev. Perspect. 1, 26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00006.x

Coplan, R. J., Ooi, L. L., and Baldwin, D. (2019). Does it matter when we want to be alone? exploring developmental timing effects in the implications of unsociability. New Ideas Psychol. 53, 47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.01.001

Coplan, R. J., Ooi, L. L., and Nocita, G. (2015). When one is company and two is a crowd: why some children prefer solitude. Child Dev. Perspect. 9, 133–137. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12131

Coplan, R. J., Prakash, K., O’Neil, K., and Armer, M. (2004). Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 40, 244–258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inquiry 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Degnan, K. A., and Fox, N. A. (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Dev. Psychopathol. 19, 729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363

Ding, X., Weeks, M., Liu, J., Sang, B., and Zhou, Y. (2015). Relations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children: moderating effect of behavioural control. Infant Child Dev. 24, 94–103. doi: 10.1002/icd.1864

Fan, Z., and Fan, X. (2021). Effect of social support on the psychological adjustment of Chinese left-behind rural children: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 11:604397. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.604397

Fung, H. (1999). Becoming a moral child: the socialization of shame among young Chinese children. Ethos 27, 180–209. doi: 10.1525/eth.1999.27.2.180

Gao, D., Liu, J., Xu, L., Mesman, J., and van Geel, M. (2022). Early adolescent social anxiety: differential associations for fathers’ and mothers’ psychologically controlling and autonomy-supportive parenting. J. Youth Adolesc. 51, 1858–1871. doi: 10.1007/s10964-022-01636-y

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530

Hartup, W. (1983). “Peer relations,” in Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality, and Social Development, ed. E. M. Hetherington (New York: Wiley), 103–196.

Kovacs, M. (1992). CDI. Children’s Depressive Symptoms Inventory. New York, NY: Multi-Health Systems.

La Greca, A. M., and Stone, W. L. (1993). Social anxiety scale for children-revised: factor structure and concurrent validity. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 22, 17–27. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_2

Lamblin, M., Murawski, C., Whittle, S., and Fornito, A. (2017). Social connectedness, mental health and the adolescent brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 80, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.010

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 1198–1202. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Liu, J., Bowker, J. C., Coplan, R. J., Yang, P., Li, D., and Chen, X. (2019). Evaluating links among shyness, peer relations, and internalizing problems in Chinese young adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 29, 696–709. doi: 10.1111/jora.12406

Liu, J., Chen, X., Coplan, R. J., Ding, X., Zarbatany, L., and Ellis, W. (2015). Shyness and unsociability and their relations with adjustment in Chinese and Canadian children. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 46, 371–386. doi: 10.1177/0022022114567537

Liu, J., Chen, X., Zhou, Y., Li, D., Fu, R., and Coplan, R. J. (2017). Relations of shyness-sensitivity and unsociability with adjustment in middle childhood and early adolescence in suburban Chinese children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 41, 681–687. doi: 10.1177/0165025416664195

Liu, J., Coplan, R. J., Chen, X., Li, D., Ding, X., and Zhou, Y. (2014). Unsociability and shyness in Chinese children: concurrent and predictive relations with indices of adjustment. Soc. Dev. 23, 119–136. doi: 10.1111/sode.12034

Liu, J., Xiao, B., Hipson, W. E., Coplan, R. J., Yang, P., and Cheah, C. S. L. (2018). Self-regulation, learning problems, and maternal authoritarian parenting in Chinese children: a developmental cascades model. J. Child Fam. Stud. 27, 4060–4070. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1218-x

Masten, A. S., Morison, P., and Pellegrini, D. S. (1985). A revised class play method of peer assessment. Dev. Psychol. 21, 523–533. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.3.523

Meerits, P., Tilga, H., and Koka, A. (2023). Web-based need-supportive parenting program to promote physical activity in secondary school students: a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Public Health 23:1627. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16528-4

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus Statistical Modeling Software. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2018). China Statistical Yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

Rubin, K. H., and Coplan, R. J. (2004). Paying attention to and not neglecting social withdrawal and social isolation. Merrill Palmer Quarterly 50, 506–534. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2004.0036

Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., and Bowker, J. C. (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642

Rubin, K. H., and Mills, R. S. L. (1988). The many faces of social isolation in childhood. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 56, 916–924. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.916

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., and Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. J. Youth Adolesc. 39, 47–61. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6

Schwartz, D., Chang, L., and Farver, J. M. (2001). Correlates of victimization in Chinese children’s peer groups. Dev. Psychol. 37, 520–532. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.520

Sun, L., Liang, L., and Bian, Y. (2017). Parental psychological control and peer victimization among Chinese adolescents: the effect of peer pressure as a mediator. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 3278–3287. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0834-1

Terry, R., and Coie, J. D. (1991). A comparison of methods for defining sociometric status among children. Dev. Psychol. 27, 867–880. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.867

Ulman, J. B. (2013). “Structural equation modeling,” in Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th Edn, eds B. G. Tabachnick and L. S. Fidell (London: Pearson Education), 681–785.

Xiao, B., Bullock, A., Liu, J., and Coplan, R. (2021). Unsociability, peer rejection, and loneliness in Chinese early adolescents: testing a cross-lagged model. J. Early Adolesc. 41, 865–885. doi: 10.1177/0272431620961457

Yan, F., Zhang, Q., Ran, G., Li, S., and Niu, X. (2020). Relationship between parental psychological control and problem behaviours in youths: a three-level meta-analysis. Children Youth Serv. Rev. 112:104900. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104900

Youniss, J. (1980). Parents and Peers in Social Development: a Sullivan-Piaget Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Yu, J., Cheah, C. S. L., Hart, C. H., Sun, S., and Olsen, J. A. (2015). Confirming the multidimensionality of psychologically controlling parenting among Chinese-American mothers: love withdrawal, guilt induction, and shaming. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 39, 285–292. doi: 10.1177/0165025414562238

Zarra-Nezhad, M., Kiuru, N., Aunola, K., Zarra-Nezhad, M., Ahonen, T., Poikkeus, A., et al. (2014). Social withdrawal in children moderates the association between parenting styles and the children’s own socioemotional development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 1260–1269. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12251

Zhang, L., and Eggum-Wilkens, N. D. (2018). Unsociability in Chinese adolescents: cross-informant agreement and relations with social and school adjustment. Soc. Dev. 27, 555–570. doi: 10.1111/sode.12284

Zhao, S., Liu, M., Chen, X., Li, D., Liu, J., and Liu, S. (2023). Unsociability and psychological and school adjustment in Chinese children: the moderating effects of peer group cultural orientations. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 54, 283–302. doi: 10.1177/00220221221132810

Keywords: unsociability, parental psychological control, socio-emotional functioning, Chinese children, moderating effect

Citation: Zheng H, Hu Y, Cao Y, Li R, Wang N, Chen X, Chen T and Liu J (2024) The moderating effects of parental psychological control on the relationship between unsociability and socio-emotional functioning among Chinese children. Front. Psychol. 15:1308868. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1308868

Received: 07 October 2023; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 05 March 2024.

Edited by:

Wenchao Ma, The University of Alabama, United StatesReviewed by:

Niccolò Butti, Eugenio Medea (IRCCS), ItalyHenri Tilga, University of Tartu, Estonia

Luis Felipe Dias Lopes, Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil

Copyright © 2024 Zheng, Hu, Cao, Li, Wang, Chen, Chen and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junsheng Liu, anNsaXVAcHN5LmVjbnUuZWR1LmNu

Hong Zheng

Hong Zheng Yihao Hu

Yihao Hu Yuchen Cao3

Yuchen Cao3 Ran Li

Ran Li Nan Wang

Nan Wang Junsheng Liu

Junsheng Liu