- 1Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Central de Chile, Santiago, Chile

- 2Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Mayor, Santiago, Chile

- 3Laboratorio Transformación y Agencia Humana, Instituto de Bienestar Socioemocional, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile

Introduction: This systematic review identified qualitative and mixed-methods empirical studies on psychotherapy from dialogical and narrative approaches, aiming to address the following questions: (1) How are subjectivity and intersubjectivity qualitatively understood in dialogical and/or narrative psychotherapies studied using dialogical and narrative approaches? (2) How do therapeutic changes occur, including their facilitators and barriers? (3) What psychotherapeutic resources are available for psychotherapists in these types of studies?

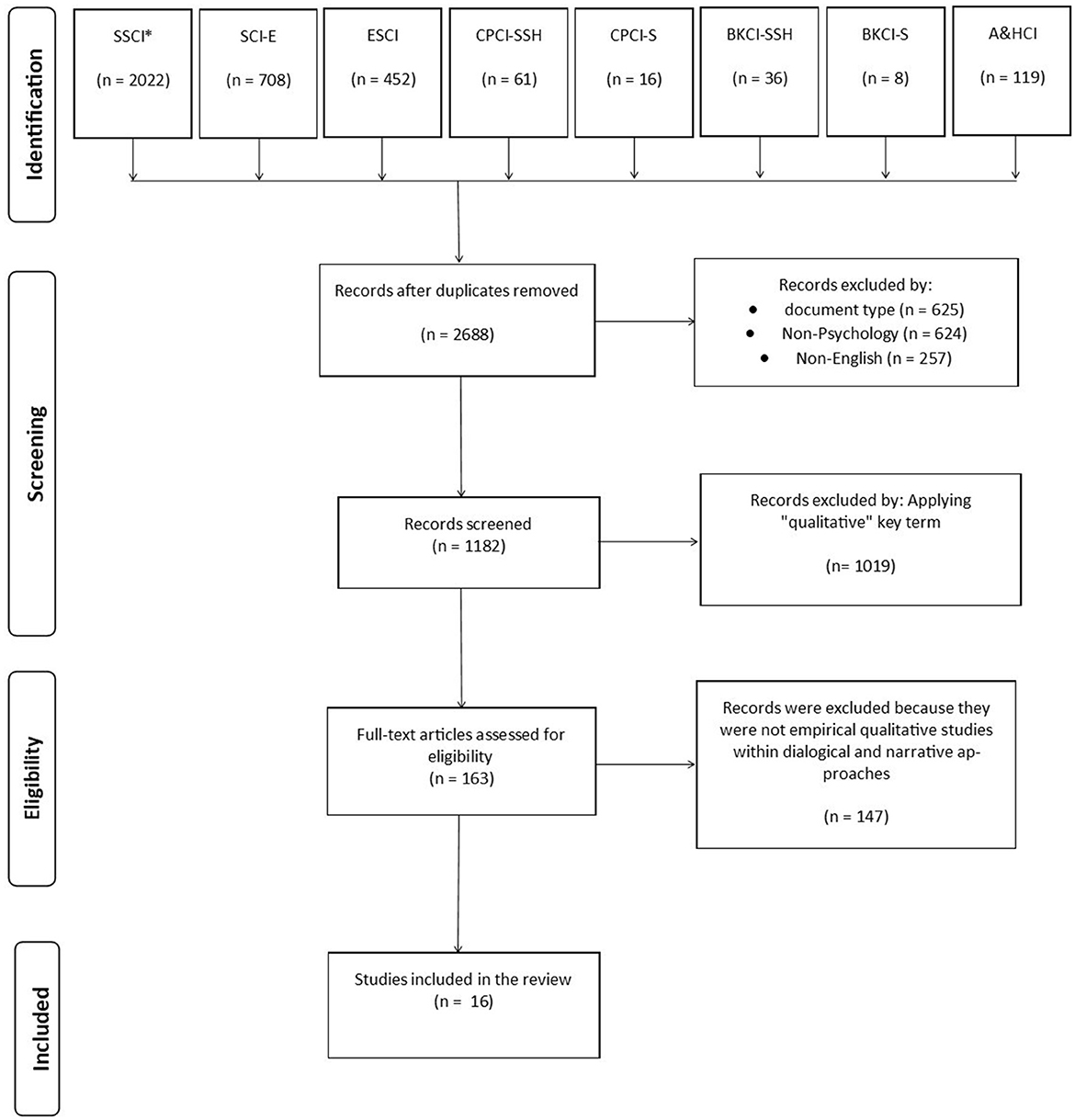

Method: The articles were selected according to the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the eligibility criteria proposed by the PICOS strategy (participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design) from 163 records identified in the Web of Science Core Collection databases.

Results: The systematic review process allowed the selection of 16 articles. The results provided insights into the understanding of subjectivity, intersubjectivity, change in psychotherapy, its facilitators, and barriers from these perspectives. It also offered some therapeutic interventions that can be implemented in psychotherapies, integrating dialogical and/or narrative aspects.

Discussion: The centrality of dialogical exploration of patient/client resources, therapists as interlocutors fostering client agency, polyphony serving as scaffolding for change, and interconnection with the sociocultural environment are discussed. The integration of this latter topic has been a challenge for these types of studies, considering the active construction of shared meanings. The dialogical and narrative approaches focus psychotherapy on transforming meanings through dialogue and re-authoring stories, evolving within cultural and historical contexts. Thus, this study highlights the relevance of these perspectives in contemporary psychotherapy, emphasizing dialogue in co-creation within an intersubjective framework.

1 Introduction

The evolution of psychotherapeutic knowledge includes the integration of approaches that have been proposed at other times or from other disciplines and that allow for resituating concepts from a broader and more contemporary perspective. Certain psychological paradigms that extend their fields of action to psychotherapy have taken up notions coming from, among others, linguistics, anthropology, or the classics of psychology, sustaining a form of understanding that is usually comprehensive, as it is complemented and integrated by different lenses, such as the semiotics and cultural studies of R. Barthes, the historical-cultural psychology of Lev Vygotsky, the literary theory, sociolinguistics, and culturalism of M. Bakhtin, or the functionalism of W. James (Hermans and Gieser, 2013a; Valsiner, 2014).

In general, some of these new traditions recognize that, in any psychotherapy, an interaction is established between at least two individuals, in which patients/clients construct stories in the presence of themselves and their therapists. These stories are constructed within an exchange or dialogical space in which novel content or new connections between their constituent parts can be established (Hermans, 2004). Furthermore, this reflects the activation of narrative processes by patients/clients, shaping these specific stories or accounts and giving them structures that convey other contextualizing aspects, imparting a narrative quality to them (McLeod, 1997). Psychotherapy would then be a dialogic scenario in which stories are told and actualized, sometimes as descriptions and other times as narratives, drawing on their constituent elements from the constant interaction of the patient's self, the therapist, and the cultural and historical contexts in which they are embedded. Narratives are forms of organization of different experiences in which the narrators are storytellers and that may include themselves, that is, in self-narratives organized within an intersubjective and dialogical process in which the therapist and patient/client intertwine internal and external, real and imaginary dialogues (Hermans and Hermans-Jansen, 1995).

In recent decades, two approaches have stood out for their contributions to understanding dialogic and narrative construction in psychotherapy. One is rooted in the dialogical perspective, primarily, though not exclusively, in dialogical self-theory (Hermans and DiMaggio, 2004; Konopka et al., 2018a), and the other is known simply as narrative therapy (White and Epston, 1990; Angus and McLeod, 2004). The dialogical perspective integrates a modern understanding of patients' selves, considering coherence and continuity, with a postmodern or post-Cartesian perspective suggesting disorganization, fragmentation of the self, and transcending external/internal duality (Hermans, 2003, 2014). Both dialogical and narrative approaches reference constructivist and constructionist thinking, conceptualizing identity as multiple, changing, and interpenetrating with the social world (Hermans et al., 1992; Neimeyer, 2006).

There are also dialogical and narrative contributions to individual and family psychological assessment methods. At the individual level, collaborative assessment methods (CAM) promote the involvement or collaboration of patients in their evaluative processes through a procedure of triangulating narratives (Aschieri, 2012), co-constructing assessment goals and tasks in coherence with their life experiences and goals (Aschieri et al., 2023), which will ultimately influence more integrated self-narratives and therapeutic change. At the family level, the Therapeutic Assessment with Families with Children (TA-C) proposes that test results be addressed as hypotheses that can be discussed and reconstructed among the family and the evaluators, fostering flexibility and the development of creative solutions to difficulties (Aschieri et al., 2012).

The dialogical approach proposes that the self is shaped by a set of I-positions that function as a society of the mind capable of conceiving dialogical or monological interactions (Konopka et al., 2018b). Based on the Bakhtinian notion of speech genres, which are defined as heterogeneous temporal structures of discourse and as relatively stable types of utterances that settle in each sphere of language use (Bakhtin, 2022), for dialogism, there exists no discourse outside the speech genre. Psychotherapy can be understood as a particular cultural practice organizing discursive exchanges between therapist and patient, considering it a language community or part of situational languages (Leiman, 2011; Martínez et al., 2014). Moreover, similar to a polyphonic novel, each self-position can construct specific narratives through a multiplicity of voices (Hermans, 1996, 2003). The voices engage in a dialogue between internal and external I-positions, with the external referring to positions where others are present within the I, that is, the other conceived as another I within an extended dialogical self (Hermans, 2014). It is also possible for certain external positions to be internalized by adopting others' viewpoints (DiMaggio et al., 2010). Thus, an I-position can be considered the place from which voices engage in internal dialogue or emerge toward the external world. Seikkula (2008) asserted that experience leaves traces in the body, but only a minimal portion is formulated into spoken narratives. When converted into words, they become voices. Voices are also defined as traces or marks that are activated and triggered by new events similar to or related to an experience (Stiles, 2002). Therefore, individuals would have multiple internal voices. These inner voices can be understood as sub-communities of experiences connected through shared and mutually accessible meanings (Osatuke and Stiles, 2006), imbued by broader social and cultural contexts. In dialogical exchanges, voices are spatially positioned, and narratives are temporally displayed (Pollard, 2019).

Similar to other postmodern therapies, the dialogical perspective understands change in psychotherapy as a semantic process of transforming meanings (Avdi and Georgaca, 2007), as can be seen in the narratives that emerge from dialogical exchanges between therapists and patients/clients. The transformation of meaning is based on the negotiation and exchange of signs between the I and the other, which are socially acquired in the processes of semiotic mediation (Valsiner, 2002; Salgado and Clegg, 2011). The dialogical self can generate self-reflective processes that accompany its transition from monological and rigid to dialogical and flexible discursive exchanges. These processes can be supported by positions called promoters and meta-positions. Promoter positions have the potential to generate and organize more specific, future-oriented positions and contribute to the reorganization of the self. On the other hand, meta-positions allow for maintaining some distance from other positions and provide an overview that allows the observation and identification of significant connections between them (Hermans and Gieser, 2013b). Changes are based on the multivoiceness in dialogue that constructs new meanings as new conversations are established (Rober, 2005; Seikkula and Arnkil, 2019), including therapeutic conversations that enhance novel distinctions in stories and narratives. Narrative therapy considers it fundamental that the organization of the life events of patients/clients revolves around specific stories or narratives expressed in sequences over time, allowing for the formation of coherent narratives of themselves and the world around them (Neimeyer, 2000; Adler, 2013). The representations of these stories or narratives, which are based on experiences, determine how life and interpersonal relationships are experienced. White and Epston (1990) suggest that stories have a characteristic of “relative indeterminacy” or ambiguity due to the presence of implicit meanings, varying perspectives, and a diversity of metaphors that can enrich event descriptions. They would present states of credibility that point not to a final state of certainty but to varying perspectives. Their morphosyntactic structure is organized in relation to time and often manifests grammatically in the subjunctive mood (expressing actions, states, or situations that are hypothetical, possible, uncertain, or subjective) instead of an indicative mood (expressing actions, states, or situations considered real, objective, and concrete).

Therapy from this approach focuses on “therapeutic conversations” as it transcends the linearity of an intervention or treatment. The general assumption is that people face problems and seek therapy when the narratives they construct about their experiences do not adequately represent those experiences. The therapeutic conversations allow patients/clients to disengage from the dominant stories that have influenced their lives and relationships. The externalization process promotes the interpretation of new meanings by integrating novel outcomes into alternative stories that can be coherently integrated. As storytellers, patients/clients can position themselves as protagonists in their experiences. Based on the notion of interpretive acts, the retelling of stories as novel narratives becomes relevant either by themselves or together with others, engaging in the constant re-authoring of one's own life and interactions with others. In doing so, they may discover important aspects of their experience that they had not previously considered but that may potentially be significant (White and Epston, 1990; McLeod, 2006; White, 2016).

One common and possibly core aspect of the dialogical approach and narrative therapy is the concept of self-narratives. Any process of “reconstructing subjectivity” (Avdi and Georgaca, 2007) requires a transformation in the self-narratives, whether it is understood as a re-authoring or a re-subjectivation process. A self-narrative consistent with lived experiences allows for a sense of continuity and meaning, organizing life in the present moment and interpreting subsequent experiences (White and Epston, 1990). Therapeutic conversations can facilitate integration and greater awareness among the multiple voices and positions of patients/clients (Martínez et al., 2014) to the extent that the dialogues integrate self-narratives into their stories or narratives. The generation of therapist-patient/client dialogues that enable these changes requires the emergence of an intersubjective awareness in which the issues raised can be addressed by paying attention to and suggesting possible new perspectives on them (Seikkula and Arnkil, 2019). The relational perspective underlying these approaches considers subjectivity to be the result of internal dialogues and allows us to understand intersubjectivity within the framework of communicative relations intertwined with culture and social institutions (Rober et al., 2008; Gillespie and Cornish, 2010). According to Marková (2003, 2016), the dialogical perspective on intersubjectivity could be situated in a dimension of irreducible interdependence between self and other(s) in which experiences are constituted in a given social and cultural context. According to the author, from a Bakhtinian perspective, this inter-subjective dynamic is better expressed by the concept of co-authorship. In this way, dialogical interaction would not result in the fusion of self and other(s) but rather in an active understanding of the unfamiliar within oneself in reference to others, in discourse (leading to tension between Ego and Alter), and in the result of their own positions arising from this exchange or confrontation. This struggle for the construction of meanings is established in a frontier in which the limits are diffusely demarcated by the interrelationship between self and other (s) (del Río, 2012), who are co-authors and share responsibility for the communication processes they establish.

A critical review of narrative research in psychotherapy included 20 articles (published between 1997 and 2005) and identified four specific aspects: (a) studies that produce thematic analyses of the content of narratives, (b) studies that produce typologies of client narratives, (c) studies that employ a dialogical approach to the study of narratives, and (d) studies that focus on narrative processes (Avdi and Georgaca, 2007). Within the scope of the two dialogical studies collected by this review (aspect c, including two studies in total), it can be observed that therapeutic change can be evidenced in the development of richer dialogues among the main characters in the patients'/clients' narratives as well as in the development of a reflective and observational metaposition.

A meta-synthetic systematic review that collected 35 articles (published between 1992 and 2018) based on systemic and constructivist approaches in psychotherapy addressed the process of change in therapeutic dialogue in sessions and found four main themes: (a) shifting to a relational perspective, (b) shifting to a non-pathologizing therapeutic dialogue, (c) moving dialogue forward, and (d) the dialogic interplay of power (Tseliou et al., 2021). Regarding the dialogical studies included in this systematic review, it was possible to establish results in three of the themes that emerged (themes a, c, and d, including four studies in total), leading to the conclusion that the evolution of psychotherapy requires a shift from monologic to dialogic and an alternation in the distribution of the exercise of power. These dimensions point to the achievement of polyphony and communicative reflexivity based on therapists' receptivity and authenticity in relation to the voices of patients/clients, using techniques such as open-ended questions, cross-voice positioning (adopting the voices of others), or the introduction of alternative meanings.

These two reviews address important aspects of the dialogical and narrative understanding of psychotherapy studies. However, both studies have limited scope with respect to the number of properly dialogical studies reviewed and do not include in their search any research based on methods built from these perspectives and applicable to psychotherapy, such as the Personal Position Repertoire (PPR) (Hermans, 2001, 2006), Narrative Process Coding System, or Narrative-Emotion Process Coding System (Angus et al., 1999, 2017), among others. A third recent review was built exclusively on studies designed from the latter two aforementioned narrative coding methods and concluded that these coding systems allow the recognition of whether patients/clients are in non-productive processes, such as identifying impersonal and superficial narratives (problem markers), or whether they are in the process of change (transition markers) (Aleixo et al., 2021). These systems enable distinguishing between different ways of constructing narratives, aiding in understanding the stages of the change process, and guiding potential interventions.

Unlike previous reviews, the present systematic review aimed to identify studies based on qualitative methods in psychotherapy that clearly presented a dialogical and narrative perspective in the intervention offered, design, and interpretation of results. The questions addressed in the current systematic review were as follows: (1) How are subjectivity and intersubjectivity qualitatively understood in dialogical and/or narrative psychotherapies studied using dialogical and narrative approaches? (2) How do therapeutic changes occur, including their facilitators and barriers? 3. What psychotherapeutic resources are available for psychotherapists in these types of studies?

2 Materials and methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021a,b) were used for this review, and the PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study Design) strategy was used to establish the eligibility criteria for the studies (Higgins and Green, 2008; Methley et al., 2014). According to the checklist of the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021a,b), the following quality steps for systematic reviews were verified in line with the following sections: 1 (title), 2 (structured abstract), 3 (rationale), 4 (objectives), 5 (eligibility criteria), 6 (sources of information), 7 (search strategy), 8 (selection process), 9 (data extraction process), 10a and 10b (data items), 11 (study risk of bias assessment), 13 (synthesis methods), 16a and 16b (study selection), 17 (study characteristics), 18 (risk of bias in studies), 23 (discussion), 24 (registration and protocol), 25 (support), 26 (competing interests), and 27 (availability of data, code, and other materials). The following sections were excluded because the data from each study that satisfied the criteria were not considered pertinent for the present review, were not available, or were presented only in a general manner after having been part of a respective protocol: 12 (effect measures), 14 (reporting bias assessment), 15 (certainty assessment), 19 (results of individual studies), 20 (results of syntheses), 21 (reporting biases), and 22 (certainty of evidence). This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023418839) and is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023418839.

The search strategy and selection of studies that are part of the review are described below and are analyzed following the guidelines for narrative syntheses in systematic reviews suggested by the document PRISMA-P 2015 (Popay et al., 2006; Shamseer et al., 2015). The choice of narrative synthesis rather than qualitative meta-analysis or meta-synthesis was based on the descriptive nature of the information sought from the studies and the different potential methodological sources used to create dialogical and narrative data. In contrast, the criteria for guiding qualitative meta-analyses or meta-syntheses (Walsh and Downe, 2005; Levitt, 2018) require diverse studies that delimit methodological techniques (in our case, for example, we could include phenomenological and hermeneutic methodologies) and similar thematic issues or types of studies, which can be compared (in our case, we will include naturalistic studies as well as single and multiple case studies), thus avoiding, in this particular case, problems with the reliability of the results.

2.1 Search strategy

A group of articles was established as a homogeneous citation base, thereby safeguarding the independence of indexing databases that use different calculation strategies to determine the impact factors and quartiles of the journals (Bakkalbasi et al., 2006; Falagas et al., 2008; Chadegani et al., 2013; Harzing and Alakangas, 2016; Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). The review relied on the Web of Science (WoS) core collection, selecting articles published in journals indexed by WoS via a search vector on this topic in psychotherapy [TS = ((psychother*) AND ((dialogic*) OR (narrati*))] without restricted temporal parameters. The extraction was performed on 5 April 2023. Only documents typified as articles by WoS were included, regardless of whether they had additional parallel typifications by WoS. Next, considering the focus of this review, the key term “qualitative” was applied to each abstract of the pre-selected articles to filter out studies that did not explicitly declare the use of this methodology, which is predominant in dialogical and narrative studies.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

The articles were selected based on the PICOS eligibility criteria (Table 1).

Table 1. Eligibility criteria using Participants, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study Design (PICOS).

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

First, duplicate articles were manually removed. Review articles, early access papers, proceeding papers, editorial material, book reviews, book chapters, meeting abstracts, books, corrections, discussions, letters, and reprints were excluded from the analysis. Articles not related to psychology research were also excluded. Finally, articles that were not in English were also excluded.

Afterward, the titles and abstracts of each article were checked for relevance by all authors of this work (clinical psychologists with postgraduate dialogical training). Subsequently, the authors independently reviewed the abstracts and full texts of potentially eligible articles using the PICOS criteria. The eligibility stage leading to the final inclusion was first independently conducted by the four authors, with an equal distribution of documents listed in an Excel spreadsheet from the previous stages. During this procedure, any disagreements were addressed and discussed by the two authors and were consistently ensured through intersubjective consensus (Levitt et al., 2021).

2.4 Quality assessment and risk of bias

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality and risk of bias of the included studies. The MMAT scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of the article. All of the authors independently applied the instruments to each selected study.

MMAT includes a checklist based on the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence, including criteria for the evaluation of mixed studies for systematic reviews. It defines the study category, and seven items are applied according to a score from zero to one to obtain a final percentage mean. Studies were considered high (>75%), moderate (50%−74%), or low (< 49%) quality (Hong et al., 2018; Arenas-Monreal et al., 2023).

3 Results

The search over an unrestricted period in the WoS main collection resulted in 2,688 documents from eight different databases in the Web of Science Core Collection (SSCI, Social Sciences Citation Index; SCI-EXPANDED, Science Citation Index Expanded; ESCI, Emerging Sources Citation Index; CPCI-SSH, Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science and Humanities; CPCI-S, Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science; BKCI-SSH, Book Citation Index—Social Sciences and Humanities; BKCI-S, Book Citation Index—Science; A and HCI, Arts and Humanities Citation Index). Excluding records according to document type (625), non-psychology research area (n = 624), and non-English-language articles (257) resulted in 1,182 records published between 1992 and 2023 for screening (details in Supplementary Table 1). Applying the “qualitative” key term to abstracts, 1,019 articles were excluded, reducing the corpus analyzed to 163 full-text articles retrieved and screened using the selection criteria defined with the PICOS strategy. Finally, articles that presented studies not based on psychotherapeutic empirical qualitative studies using dialogical and narrative approaches (147) were excluded. Ultimately, 16 studies published between 2003 and 2023 were selected and evaluated for quality.

The document set entered as input in the PRISMA diagram flow according to the eligibility criteria (PICOS) listed in Table 1 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram flow. *SSCI, Social Sciences Citation Index; SCI-EXPANDED, Science Citation Index Expanded; ESCI, Emerging Sources Citation Index; CPCI-SSH, Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Social Science and Humanities; CPCI-S, Conference Proceedings Citation Index—Science; BKCI-SSH, Book Citation Index—Social Sciences and Humanities; BKCI-S, Book Citation Index—Science; A&HCI, Arts and Humanities Citation Index.

A summary of the general characteristics of the included systematic reviews is presented in Table 2.

The proposed research questions were addressed using a narrative synthesis procedure applied to the selected articles. A summary of the definitions of subjectivity, intersubjectivity, change in psychotherapy, facilitators of and barriers to change, and the main therapeutic interventions from dialogical and narrative approaches obtained from each of the studies can be found in Table 3, while Table 4 shows the salient qualitative methodologies and techniques arising from each of the articles in the present review.

Quality assessment and risk of bias according to the MMAT criteria showed that 87.5% of the articles (n = 14) met >75% of the checklist criteria, indicating high quality. Twelve and a half percent of the articles (n = 2) met < 50% (42.86%) of the assessed criteria, indicating low quality. The assessment results are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

3.1 Subjectivity and intersubjectivity in psychotherapies qualitatively studied from dialogical and narrative perspectives (first review question)

From the studies examined, it can be noted that subjectivity is proposed as a dynamic and multidimensional construct involving the dialogical interaction of a multiplicity of voices and perspectives or positions (Penttinen et al., 2016; Dawson et al., 2021; Kay et al., 2021, 2023; Mellado et al., 2022a,b; Chiara et al., 2023; Hills, 2023) and that it is understood and organized through narratives that can be constantly reconstructed. These narratives reflect a unique understanding of one's personal perspective, thoughts, emotions, and interpersonal relationships. Subjectivity refers to how individuals experience and construct their sense of self and understanding of the world around them through interconnected narratives (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Boothe et al., 2010; Cardoso et al., 2016; Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016; Råbu et al., 2019; Mellado et al., 2022b; Chiara et al., 2023; Steen et al., 2023), interactions among subjective positions, and a continuous reflection on their internal and external experiences, sustained by the continuous construction of meanings (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Boothe et al., 2010: Cardoso et al., 2016; Penttinen et al., 2016; Råbu et al., 2019). It is proposed as a process in which internal voices, in constant dialogue, contribute to the formation of identity, self-awareness, a sense of agency, and the interpretation of lived experiences (Penttinen et al., 2016; Steen et al., 2023).

Self-narratives are situated as overarching structures that organize experiences into macro-narratives (more comprehensive and articulated narratives), which consolidate the understanding and meaning of the self (Cardoso et al., 2016). Subjectivity is also considered to be influenced by the cultural context, highlighting the influence of culture on the understanding of individual experiences (Danner et al., 2007).

In addition, from the information presented in some of the studies included in this review, it can be noted that intersubjectivity is proposed as a concept that underlines the relational, interactive, and collaborative basis of human experience as well as a point of connection among individuals. Intersubjectivity implies that human beings interact with each other by co-creating meanings, joint reflections, and narratives through dialogue and communication (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Danner et al., 2007; Mellado et al., 2022b; Chiara et al., 2023), generating a permanent interrelationship in which external and internal voices promote assemblies and mutual resonances (Kay et al., 2021), and positioning characters integrated into the self in an internal scenario, influencing subjective dynamics (Mellado et al., 2022a; Kay et al., 2023). Personal identities and narratives are collectively and collaboratively constructed with others through social and dialogic processes (Pote et al., 2003; Råbu et al., 2019; Chiara et al., 2023).

Intersubjectivity allows for relational unfolding in therapeutic contexts, with therapists and patients/clients collaborating to develop a trusting relationship and mutual understanding and working toward common goals in the space of encounter and recognition (Boothe et al., 2010; Penttinen et al., 2016). It is expected that in these spaces, genuine listening and openness to the negotiation of silenced and blocked voices can be generated (Dawson et al., 2021). This also involves a reciprocal process, creating an environment in which patients/clients feel free to express their experiences and emotions.

3.2 Psychotherapeutic change and its facilitators and barriers (second review question)

Regarding change, it has been suggested that during the therapeutic process, transformations can be observed in different dimensions of an individual's experience. These dimensions are (1) transformation and evolution of subjective internal and/or external positions and voices; an integration of voices within the self is generated, and their dysfunctional relationships, that is, rigid and inflexible repertoires, begin to be modified. Problematic or critical voices (for example, a critical I-position of a patient diagnosed with depression, I as wronged, expressed self-criticism based on the criticism she felt she received from “everyone” toward her) begin to be accepted and understood in a broader context, which contributes to the coherence and unity of the self (Penttinen et al., 2016; Råbu et al., 2019; Kay et al., 2021, 2023; Mellado et al., 2022a,b; Hills, 2023). (2) Transformation of narratives: transformations of personal narratives have been evidenced, along with the formation and reconstruction of self-narratives and the creation of new meanings. The re-signification of experiences and the integration of stories into personal biographies stand out as key components of change. Another relevant aspect is the construction of alternative narratives to those that were previously dominant, creating greater breadth, independence, and wellbeing (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Cardoso et al., 2016; Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016; Mellado et al., 2022a; Chiara et al., 2023; Steen et al., 2023). (3) Reconstruction of the experience of identity: individuals begin to experience changes in how they perceive themselves as well as in relation to others. A more autonomous, independent, and enriched identity develops as the self begins to re-author personal stories. Additionally, feelings of competence and self-management are generated, along with an increase in the individual's sense of agency (Dawson et al., 2021; Steen et al., 2023). (4) Reflexivity and self-observation: there is an increase in the reflexivity of patients/clients and their ability to observe and reflect on their internal experiences. Reflexivity provides an observational stance that allows individuals to more consciously question and revise interpretations of their experiences (Boothe et al., 2010; Penttinen et al., 2016). (5) Change in relationships with others: the therapeutic relationship promotes change in interpersonal relationships, serving as a model for individuals to re-signify relevant aspects of the self-other relationship and modify conflictive patterns in the different subsystems in which they interact (Pote et al., 2003; Steen et al., 2023).

Aspects that can have both a positive and negative impact on the process of change in psychotherapy should be considered.

3.2.1 Change facilitators

A safe, trusting, supportive, and understanding therapeutic environment facilitates emotional and psychological change. Overall, it strengthens and supports the relational aspects of therapeutic alliances (Dawson et al., 2021). For example, Dawson et al. (2021) showed how the dialogical process of open dialogue made women who experienced domestic violence feel safe as a non-pathologizing experience in which service users defined their own issues and felt heard and validated. Participants achieved greater security and empowerment.

Focus on emotions, reflexivity, and self-reflexivity: experiencing and reflecting on emotions can enhance emotional growth and understanding of one's internal processes, which can facilitate an increase in the breadth of dialogicality and contribute to change (Cardoso et al., 2016; Kay et al., 2023). For example, Cardoso et al. (2016) described cases in which tasks were set for patients to reflexively connect feelings, behaviors, and life episodes (micro-level) to promote understanding of the causes and consequences of issues (macro-level), aiding in the subsequent construction of new meanings.

Sharing emotional experiences: shared emotional experiences can create a sense of connection and empathy, thereby creating a supportive environment of change (Danner et al., 2007; Råbu et al., 2019; Chiara et al., 2023; Hills, 2023). According to Danner et al. (2007), women from a therapeutic group managed to share their feelings and opinions about gender roles in their culture and subsequently generated alternative ideas to safely maintain contact outside the group.

Openness to new perspectives: the willingness of patients/clients to consider new ways of experiencing and thinking (new voices and positions, characters, or relationships among them that facilitate dialogue, metaperspectives, and the possibility of rewriting stories) can enable the exploration of alternatives and changes in dysfunctional thought patterns and subjective states (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Penttinen et al., 2016; Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016; Mellado et al., 2022b; Kay et al., 2023). In the therapy of a depressed patient, the external voice of her therapist joined the patient's repertoire of internal voices and helped her generate a new version of herself, incorporating an increase in her reflective capacity and willingness to dialogue with other positions. Hence, her depressive symptoms improved (Kay et al., 2023).

Strengthening patients/clients' personal resources: this refers to enquiring into and working with one's personal characteristics and dispositions (Danner et al., 2007). For example, therapists helped depressed patients connect with resources rooted in their culture (spiritual aspects that allowed them to understand health and illness) that had not been directly addressed at the beginning of treatment. This increases the legitimacy and trust placed in therapy and enables patients to identify coping strategies close to their experience (Danner et al., 2007).

Social, family, and external resource support (Pote et al., 2003; Danner et al., 2007). Pote et al. (2003) identified categories of family therapy cases, highlighting the co-construction of reality among therapists, patients, families, and their context. The family, therapeutic team, and support network promote the construction of meanings in multiple ways, avoiding the limitations of a single reality.

3.2.2 Change barriers

Lack of internal dialogue: the lack of willingness to engage in internal dialogue between different parts of the self and the presence of monological patterns may hinder openness to new perspectives and the integration of experiences (Mellado et al., 2022a; Kay et al., 2023). In some patients, a “dictatorship” can be created wherein certain subjective positions are silenced, leaving them passive and voiceless. Kay et al. (2023) discussed the case of a patient in which a monological pattern dominated by a suppressive position called “I-shouldn't-exist” was identified, and this was associated with the maintenance of depressive symptoms.

Dominance of limiting or critical positions: if a limiting or highly critical position dominates one's internal dialogue, it can obstruct change by maintaining negative and self-critical patterns (Penttinen et al., 2016; Mellado et al., 2022a). A patient diagnosed with borderline personality disorder used to speak with a voice called “envious child” (identified with the Model of Discursive Positioning in Psychotherapy, MAPP) when she compared her troubled childhood with that of others. This comparison created ambivalence toward her adult life as she felt that she had not truly experienced a happy childhood (Mellado et al., 2022a).

Difficulty expressing internal experiences (intense emotions or hard-to-verbalize thoughts), rigidification of certain beliefs, and not sharing narratives in meaningful emotional contexts should be considered. Such a scenario challenges the therapeutic relationship and its understanding (Boothe et al., 2010; Chiara et al., 2023; Hills, 2023). Chiara et al. (2023) described difficulties in therapeutic changes for patients who had experienced traumatic events. Certain dominant positions (such as “I as victim”) were identified, which limited their narratives and affected their psychological growth. Progress was achieved when these positions were listened to and accepted in the therapeutic space.

External obstacles to the therapeutic process: external obstacles can hinder the therapeutic process and change. Short-term therapies with a limited number of sessions may hinder further exploration (Danner et al., 2007; Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016). The patients in one study indicated that the duration of 10 sessions of therapy was insufficient to benefit from the process (Danner et al., 2007).

3.3 Psychotherapeutic resources available to psychotherapists (third review question)

The types of interventions mentioned below reflect the active and collaborative role of therapists with patients/clients in the co-construction of meanings and in promoting the context of growth and subjective transformation in psychotherapy. Studies have demonstrated consistency between the theoretical and clinical assumptions of these models and the therapeutic interventions they describe.

1. Establishing empathy and acceptance: putting empathy into practice toward all voices and positions of patients/clients, allowing them to feel actively heard and understood (Penttinen et al., 2016; Chiara et al., 2023; Kay et al., 2023).

2. Co-creation or co-authoring of meaning: working with patients/clients to make sense of their experiences and explore different interpretations, perspectives, re-authoring processes, and possible meanings. Therapists can encourage the exploration of multiple perspectives and the negotiation of new storylines for narratives that arise in therapy (Pote et al., 2003; Danner et al., 2007). Using specific techniques such as externalizing problems (White and Epston, 1990), which focus on viewing difficulties as something external to the definition of the self, can mobilize different positions and perspectives (Danner et al., 2007; Hills, 2023).

3. Developing reflexivity: this involves encouraging reflection on one's own experiences and thoughts, helping patients/clients question their beliefs and perspectives, promoting the subjective and reflective processes of re-elaboration, and facilitating symbolic representation (Cardoso et al., 2016; Råbu et al., 2019). Additionally, it is crucial to explore how patients'/clients' different positions interact and influence each other and how they may change over time.

4. Promoting internal and external dialogue and the emergence of meta-positions: enable dialogue among different patient/client positions to explore internal conflicts, modify dialogues among characters that inhibit the patient's self, promote open communication, open dialogue (Seikkula et al., 2003), and build new perspectives and alternative narratives or counter-narratives (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Danner et al., 2007; Dawson et al., 2021; Mellado et al., 2022b; Chiara et al., 2023; Kay et al., 2023).

5. Amplifying change: identifying moments of change, innovations, or new perspectives in the narratives of patients/clients and exploring positions and styles of authorship that allow for their amplification and strengthening (Mellado et al., 2022a; Hills, 2023). This can facilitate the emergence of new ways of thinking and feeling as they recur in the therapeutic process.

6. Contextual interventions and analysis/use of narrative styles: working on contextualizing and reflecting on the context of the stories, including social, cultural, and personal aspects that influence the adoption of specific narratives, the analysis of the structure/coherence of autobiographical narratives, and the exploration of changes, conflict themes, and significant relationships in the narratives (Pote et al., 2003; Boothe et al., 2010; Steen et al., 2023).

7. Aligning techniques with the stage of the change process: using techniques that fit the stage of change in which patients/clients find themselves, respect their ability to address particular issues according to their subjective constitution at the moment (Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016).

4 Discussion

This systematic review, guided by the PRISMA guidelines, aimed to understand how subjectivity and intersubjectivity are understood in psychotherapy from dialogical and narrative approaches, as well as the process of change in psychotherapy and identify its facilitators and barriers. In addition, it provides information on psychotherapeutic resources and strategies that may be available to psychotherapists based on these approaches. For this purpose, an analysis was centered on WoS databases, which allowed us to focus on the search according to the document type, research area, and language of the eligible articles. The second phase was oriented toward the final selection of articles based on qualitative and mixed-methods empirical studies. Sixteen articles were reviewed after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This review highlights the emphasis on the transformation of meanings through dialogue and the co-creation of narratives within an intersubjective framework promoted by dialogical and narrative perspectives. The studies employed mostly qualitative methodologies that capture both narrative-dialogical exchanges and the construction of stories related to the therapeutic process, providing relevant study material for psychotherapists and those working in clinical psychology. This was also manifested in the psychotherapeutic interventions derived from previous studies, offering insights and specific tools for improving practices.

In general, the outcomes of the patients/clients reviewed in the studies highlighted awareness, self-reflection, and reflective dialogues of internal and external positions in therapy, along with a review of life experiences, as well as the co-construction of narratives in therapy. Additionally, the therapists' self-reflection processes regarding their role, functions, possibilities, and limitations were emphasized, occasionally stressing a non-expert stance and being an engaged interlocutor in a dialogue whose mission is to promote agency, subjective transformation, and empowerment of patients/clients. The dialogical approach emphasizes the exploration of patient resources, with therapists acting as active interlocutors, facilitating dialogue. The use of resources and a sense of agency enable the interplay between the elaboration of new meaning and narrative construction.

This review showed that the organization of narratives is dynamic and becomes more complex as new subjective positions are integrated through dialogical exchanges promoted by psychotherapy. In this context, the therapist's role in promoting new voices or alternative positions (Mellado et al., 2022b; Chiara et al., 2023) or offering other perspectives regarding the dominant viewpoint (or dominant voices) of patients/clients (DiMaggio et al., 2003; Kay et al., 2021, 2023) is fundamental for the mobilization of narratives. These approaches are based on the premise that patients and clients have the capacity to construct their reality and reconstruct it through reflection and the affective connections established in their social exchanges, with therapeutic relationships being a particular social instance for promoting this creative potential.

One study suggests that the Vygotskian concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZDP) can be understood as a dialogic space of encounter between therapist and patient positions (Penttinen et al., 2016), beyond the precautions needed when conducting psychotherapy interventions (Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016). The classical definition of ZDP indicates a space for potential learning that lies between what an individual can already do on their own and what they cannot yet do, even with external assistance (Vygotsky, 1978). In other words, it represents an individual's learning potential, which another individual can facilitate if it does not go beyond an unattainable level of demand.

Leiman and Stiles (2001) propose that the ZPD can describe the joint activity of the therapist and patient, as a transitional space between the patient's current level of development and the level they can reach with the help of the therapist to overcome their psychological difficulties. This application aligns with the stages of the patient's assimilation continuum to resolve problems and match therapeutic interventions (Zonzi et al., 2014). Encounters and mismatches can either facilitate or hinder unidirectional therapeutic progress.

Discursive and linguistic interventions guided by dialogical principles both facilitate and challenge the transition between a patient's current achievements and their potential by inquiring into each other and generating alternative meanings that are not autonomously explored or externalized. Polyphony can be an alternative for facilitating and scaffolding therapeutic changes.

Regarding some methodological tools used in the studies, Hills (2023) proposed an autoethnographic account using tools such as supervision, personal therapy, dreams, and daily life. He stated that theories of change in the therapist respond to ongoing meaning processing in the therapeutic space as dialogue evolves. He intended to demonstrate the use of self-reflection as a research instrument. Råbu et al. (2019) referred to two important processes when employing autoethnography: the therapist's self-awareness as an ongoing process understood as curiosity toward oneself and the therapy process itself, and the fact that retelling personal experiences is recognizing self-awareness. The use of personal experiences can be a threat to less experienced therapists as it inevitably triggers personal memories. In addition, having the experience of undergoing therapy was considered important for understanding clients' feelings and difficulties in relation to psychotherapy. It could be determined upon reflection at this point that to understand the client's experience, the therapist must necessarily find some common ground, be it a feeling, some knowledge, curiosity, or a familiar situation, to make sense of the process. Both Hills (2023) and Råbu et al. (2019) agreed that active self-reflection by therapists promotes therapeutic change.

In clinical practice employing narrative and dialogical approaches, therapists are considered partners in an ongoing dialogue, distinguishing their expertise as following, encouraging, and sustaining new meanings for old problems (Danner et al., 2007). This calls for respect for others, great flexibility, a sense of timing and trust, and respecting the pace and idiosyncratic ways of patients (Dawson et al., 2021). Dialogues evolve, and narratives are repeatedly told until a novel perspective is gained. Several qualities are frequently mentioned as essential to clinical practice, such as flexibility, emphatic disposition, willingness to contribute to narratives and dialogues, and promotion of new narratives (Pote et al., 2003; Penttinen et al., 2016; Piazza-Bonin et al., 2016). To this end, it should add tolerance to uncertainty, ambivalence, and ambiguity, all semiotic qualities that accompany any psychological elaboration. They are part of the manner in which the self is expressing itself, provide the stance to reframe the ongoing processing in psychotherapy, and provide an opportunity for psychotherapists to intervene. Finally, when narrating or engaging in dialogue, therapists situate themselves within a basic trust frame (Marková and Gillespie, 2007). Pieces of experiences and thoughts brought about by internal and external visiting voices were offered to both the therapist and patients. When citing Bakjtin, Markova stated that trust is vital for communication (Marková and Gillespie, 2007). Any attempt to avoid commitment and responsibility results in non-communication. Orange (2009) added that pursuing hermeneutic psychotherapeutic sensibility requires a strong awareness of one's own limitations and resources, a historical sense of the lives of others, expectations of complexity, and a strong commitment.

An important limitation of the present review lies in the deliberate search for studies that have explicitly stated the term “qualitative” to refer to the methodology used in their research, potentially excluding articles that have not declared this. In addition, most of the participants identified were psychiatric patients and individual case studies, which limits the possibilities for understanding other dimensions of these approaches (e.g., family therapy, couple therapy, group therapy, and psychosocial interventions).

Avdi and Georgaca (2007) suggest that sociocultural aspects might not be sufficiently incorporated when conducting microtherapeutic processing. This poses a limitation that should be considered when implementing microanalytical qualitative methodologies such as those used in the studies included in this review. If voices are partially shaped by culture and respond to external demands, these voices, whether internal or external, would be continually related to various external sources, as well as discursive and linguistic interventions that both facilitate and tension the generation of alternative meanings that are yet unexplored and that refer to cultural aspects that need to be considered.

Marková (2003) has emphasized that, from a Bakhtinian perspective, dialogical intersubjectivity implies providing a space for the expression of the self; that is, the individual needs the other's otherness to define themselves and simultaneously propose something new in the relationship (“I-Other(s)” irreducible dyad). Following Bakhtin (2000), if words are actions, the responsiveness and protagonism of the other allow for the unfolding of the self. Although all studies acknowledge and reinforce the notion of dialogicity in both patients and therapists, the inter-subjective framework that facilitates this process is not always evident. While not explicitly stated in all of the reviewed articles, they share a perspective on subjectivity and intersubjectivity. However, the connections between these concepts are often not clearly articulated.

Moreover, terms such as meaning construction, meaning-making processes, and narrative creation have not yet been fully explained in their conceptual and clinical scopes when approached methodologically from these perspectives. On one hand, dialogical elaboration implies active interlocutors in a constant construction, an exchange in the here and now, and possibly a basis for the formation of narratives. On the other hand, narrative creation must be defined as the result of dialogical processes in which temporally framed and meaningful narratives emerge in discourse. This entails considering not only a narrator but also multiple co-authorships, achieving the coherence of events linked to a temporally sequenced theme (White and Morgan, 2006). It could also be argued that patients/clients' narratives about their problems, as well as their drawings and written texts, trigger dialogical exchange in therapy. Thus, the construction of meanings involves evolution and movement in terms of constant elaboration with no pre-established endpoint. Narratives are constructed in a dialogical exchange mediated by cultural signs, implying the early construction of notions and meaning complexes that emerge in relationships with others. Intersubjective psychoanalytic authors point out that individuals are shaped by relatively stable patterns of relationships established early in their lives (Orange et al., 2015), which can be visualized as leading voices insofar as they can offer life perspectives and organize narratives.

Future research in the field could encompass other subjective and intersubjective dimensions in dyadic psychotherapies, including some of those already addressed in studies of family and couples therapy, among others. In this scenario, multivocality may pose a challenge for both individual and interindividual research, involving processes of meaning construction in narratives and integrating the internal and external dialogues of therapists and patients/clients. However, exploration can continue regarding how certain subjective positions are more likely to be accepted by patients/clients in accordance with the potential zones established in therapist/patient dialogical exchanges, as suggested by Leiman and Stiles (2001), Penttinen et al. (2016), Piazza-Bonin et al. (2016), and Valsiner (2007). This can be analyzed through micro-processes that account for meaning construction within changing contexts in temporally bounded segments (del Río et al., 2023) in which relatively stable bonding qualities exist. Once these constructions of meaning are identified, therapists can recognize the facilitating contexts in which the emergence of subjective positions in emotionally difficult situations can be promoted.

Regarding internal conversations, it has been proposed that there are different positions in the therapist's self that engage in dialogue with each other (Rober, 2010) as well as a continuous dialogue between the professional and personal selves of therapists (Mikes-Liu et al., 2016), which underlies some interventions that emerge in external conversations with patients. Understanding the intersection between the two dimensions can be achieved by combining descriptive methodologies, such as systems for coding subjective positions (e.g., Kay et al., 2021, 2023), with techniques that allow the recognition and tracking of internal voices, such as autoethnography (e.g., Råbu et al., 2019; Hills, 2023), or post-session semi-structured interviews with therapists and patients. In this way, greater awareness could be gained regarding how internal and external dialogues contribute and intertwine to generate transformations in the narratives of patients/clients.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review included a search for qualitative and mixed-methods studies on narrative and dialogical psychotherapy approaches. It encompassed topics related to subjectivity, intersubjectivity, therapeutic changes, facilitators, barriers, and intervention strategies. The analysis was based on articles published in journals indexed in JCR-WoS. The results were derived from a rigorous evaluation procedure that enabled a narrative synthesis and discussion.

The findings of this review highlight how narrative and dialogical approaches emphasize the exploration of patient resources and the promotion of reflexivity, with therapists as active interlocutors fostering therapeutic change. Moreover, tensions related to the conceptual foundations that these perspectives support were identified, suggesting the potential applications of specific psychological concepts to dialogical and narrative-oriented psychotherapy. Among other concepts, multivoicedness remains an area to be explored as a contributing aspect of psychotherapeutic practice. These insights contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of psychotherapeutic practices and their impact on patient wellbeing.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PA-A: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MM: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The article processing charge (APC) was funded by the Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Central de Chile (Code: ACD 219201).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1308131/full#supplementary-material

References

Adler, J. M. (2013). Clients' and therapists' stories about psychotherapy. J. Pers. 81, 595–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00803.x

Aleixo, A., Pires, A. P., Angus, L., Neto, D., and Vaz, A. (2021). A review of empirical studies investigating narrative, emotion, and meaning-making modes and client process markers in psychotherapy. J. Contemp. Psychother. 51, 31–40. doi: 10.1007/s10879-020-09472-6

Angus, L. E., Boritz, T., Bryntwick, E., Carpenter, N., Macaulay, C., Khattra, J., et al. (2017). The narrative-emotion process coding system 2.0: a multi-methodological approach to identifying and assessing narrative-emotion process markers in psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 27, 253–269. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1238525

Angus, L. E., Levitt, H., and Hardtke, K. (1999). The narrative processes coding system: research applications and implications for psychotherapy practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 55, 1255–1270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1255::AID-JCLP7>3.0.CO;2-F

Angus, L. E., and McLeod, J. (Eds.) (2004). The Handbook of Narrative and Psychotherapy: Practice, Theory, and Research. London: Sage Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412973496

Arenas-Monreal, L., Galvan-Estrada, I. G., Dorantes-Pacheco, L., Márquez-Serrano, M., Medrano-Vázquez, M., Valdez-Santiago, R., et al. (2023). Alfabetización sanitaria y COVID-19 en países de ingreso bajo, medio y medio alto: revisión sistemática. Glob. Health Promot. 30, 79–89. doi: 10.1177/17579759221150207

Aschieri, F. (2012). Epistemological and ethical challenges in standardized testing and collaborative assessment. J. Humanist. Psychol. 52, 350–368. doi: 10.1177/0022167811422946

Aschieri, F., Fantini, F., and Bertrando, P. (2012). Therapeutic assessment with children in family therapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 33, 285–298. doi: 10.1017/aft.2012.37

Aschieri, F., van Emmerik, A. A. P., Wibbelink, C. J. M., and Kamphuis, J. H. (2023). A systematic research review of collaborative assessment methods. Psychotherapy 60, 355–369. doi: 10.1037/pst0000477

Avdi, E., and Georgaca, E. (2007). Discourse analysis and psychotherapy: a critical review. Eur. J. Psychother. Counsell. 9, 157–176. doi: 10.1080/13642530701363445

Bakhtin, M. (2000). Yo También Soy. Fragmentos Del Otro (1ra edición). Buenos Aires: Godot (originalmente publicada en 1975).

Bakhtin, M. (2022). Estética de la creación verbal (3ra edición). Buenos Aires: Siglo veintiuno editores (originalmente publicada en 1979).

Bakkalbasi, N., Bauer, K., Glover, J., and Wang, L. (2006). Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 3, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1742-5581-3-7

Boothe, B. (2004). Der Patient als Erza?hler in der Psychotherapie [The patient as narrator in psychotherapy], 2nd Edn. Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

*Boothe, B., Grimm, G., Hermann, M.-L., and Luder, M. (2010). JAKOB narrative analysis: The psychodynamic conflict as a narrative model. Psychother. Res. 20, 511–525. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2010.490244

*Cardoso, P., Duarte, M. E., Gaspar, R., Bernardo, F., Janeiro, I. N., and Santos, G. (2016). Life design counseling: a study on client's operations for meaning construction. J. Vocat. Behav. 97, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.07.007

Chadegani, A. A., Salehi, H., Yunus, M. M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., et al. (2013). A comparison between two main academic literature collections: web of Science and Scopus databases. ASS 9:5. doi: 10.5539/ass.v9n5p18

*Chiara, G., Romaioli, D., and Contarello, A. (2023). Self-positions and narratives facilitating or hindering posttraumatic growth: a qualitative analysis with migrant women of Nigerian descent survivors of trafficking. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 15, 1041–1050. doi: 10.1037/tra0001245

*Danner, C. C., Robinson, B. B. E., Striepe, M. I., and Rhodes, P. F. Y. (2007). Running from the demon: culturally specific group therapy for depressed Hmong women in a family medicine residency clinic. Women Ther 30, 151–176. doi: 10.1300/J015v30n01_07

*Dawson, L., Einboden, R., McCloughen, A., and Buus, N. (2021). Beyond polyphony: open dialogue in a women's shelter in Australia as a possibility for supporting violence-informed practice. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 47, 136–149. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12457

del Río, M. T. (2012). Situándose en la frontera: de la apropiación de la palabra y la tensión entre la palabra propia y la palabra ajena. Rev. Liminales. Escr. Psicol. Soc. 1, 97–115. doi: 10.54255/lim.vol1.num02.225

del Río, M. T., Andreucci-Annunziata, P., and Mellado, A. (2023). Psychotherapy displayed as an ongoing meaning-making dialogue. Cult. Psychol. doi: 10.1177/1354067X231201396

DiMaggio, G., Hermans, H. J., and Lysaker, P. H. (2010). Health and adaptation in a multiple self: the role of absence of dialogue and poor metacognition in clinical populations. Theory Psychol. 20, 379–399. doi: 10.1177/0959354310363319

*DiMaggio, G., Salvatore, G., Azzara, C., and Catania, D. (2003). Rewriting self-narratives: the therapeutic process. J. Constr. Psychol. 16, 155–181. doi: 10.1080/10720530390117920

Falagas, M. E., Pitsouni, E. I., Malietzis, G., and Pappas, G. (2008). Comparison of PubMed, scopus, web of science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 22, 338–342. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF

Gillespie, A., and Cornish, F. (2010). Intersubjectivity: towards a dialogical analysis. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 40, 19–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2009.00419.x

Gonçalves, M. M., Ribeiro, A. P., Mendes, I., Matos, M., and Santos, A. (2011). Tracking novelties in psychotherapy process research: the innovative moments coding system. Psychother. Res. 21, 497–509. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.560207

Harzing, A. W., and Alakangas, S. (2016). Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 106, 787–804. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1798-9

Hermans, H. J. M. (1996). Voicing the self: from information processing to dialogical interchange. Psychol. Bull. 119, 31–50. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.31

Hermans, H. J. M. (2001). The construction of a personal position repertoire: method and practice. Cult. Psychol. 7, 323–366. doi: 10.1177/1354067X0173005

Hermans, H. J. M. (2003). The construction and reconstruction of a dialogical self. J. Constr. Psychol. 16, 89–130. doi: 10.1080/10720530390117902

Hermans, H. J. M. (2004). “The innovation of self-narratives: a dialogical approach,” in The Handbook of Narrative and Psychotherapy: Practice, Theory, and Research, eds. L. E. Angus and J. McLeod (London: Sage Publications, Inc), 175–191. doi: 10.4135/9781412973496.d14

Hermans, H. J. M. (2006). The self as a theater of voices: disorganization and reorganization of a position repertoire. J. Constr. Psychol. 19, 147–169. doi: 10.1080/10720530500508779

Hermans, H. J. M. (2014). Self as a society of I-positions: a dialogical approach to counseling. J. Humanist. Counsel. 53, 134–159. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1939.2014.00054.x

Hermans, H. J. M., and DiMaggio, G. (Eds.) (2004). The Dialogical Self in Psychotherapy: An Introduction. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203314616_The_dialogical_self_in_psychotherapy

Hermans, H. J. M., and Gieser, T. (2013b). “Introductory chapter: history, main tenets and core concepts of dialogical self theory,” in Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory, eds. H. J. M. Hermans and T. Gieser (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–22. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139030434.002

Hermans, H. J. M., and Gieser, T. (Eds.) (2013a). Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hermans, H. J. M., and Hermans-Jansen, E. (1995). Self-Narratives: The Construction of Meaning in Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hermans, H. J. M., Kempen, H. J., and Van Loon, R. J. (1992). The dialogical self: beyond individualism and rationalism. Am. Psychol. 47, 23–33. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.23

Higgins, J. P., and Green, S. (2008). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley and Sons Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9780470712184

*and Hills, J. (2023). Modelling change in self-narratives and embodied experience:a multicase study and autoethnography. Counsell. Psychother. Res. 23, 270–282. doi: 10.1002/capr.12502

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., et al. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 34, 285–291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

Honos-Webb, L., Stiles, W. B., and Greenberg, L. S. (2003). A method of rating assimilation in psychotherapy based on markers of change. J. Counsel. Psychol. 50, 189–198. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.189

Kagan, N. (1975). Interpersonal process recall: A method for influencing human action. Unpublished manuscript, Houston, TX: University of Houston.

*Kay, E., Gillespie, A., and Cooper, M. (2021). Application of the qualitative method of analyzing multivoicedness to psychotherapy research: the case of “Josh.” J. Constr. Psychol. 34, 181–194. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2020.1717145

*Kay, E., Gillespie, A., and Cooper, M. (2023). From conflict and suppression to reflection: longitudinal analysis of multivoicedness in clients experiencing depression. J. Constr. Psychol. 37, 239–258. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2023.2175752

Konopka, A., Hermans, H. J., and Gonçalves, M. M. (2018b). “The dialogical self as a landscape of mind populated by a society of I-positions,” in Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory and Psychotherapy, eds. A. Konopka, H. J. Hermans, and M. M. Gonçalves (London: Routledge), 9–23. doi: 10.4324/9781315145693-2

Konopka, A., Hermans, H. J., and Gonçalves, M. M. (Eds.) (2018a). Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory and Psychotherapy: Bridging Psychotherapeutic and Cultural Traditions. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315145693

Leiman, M. (2011). Mikhail Bakhtin's contribution to psychotherapy research. Cult. Psychol. 17, 441–461. doi: 10.1177/1354067X11418543

Leiman, M., and Stiles, W. B. (2001). Dialogical sequence analysis and the zone of proximal development as conceptual enhancements to the assimilation model: the case of Jan revisited. Psychother. Res. 11, 311–330. doi: 10.1080/713663986

Levitt, H. M. (2018). How to conduct a qualitative meta-analysis: tailoring methods to enhance methodological integrity. Psychother. Res. 28, 367–378. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1447708

Levitt, H. M., Ipekci, B., Morrill, Z., and Rizo, J. L. (2021). Intersubjective recognition as the methodological enactment of epistemic privilege: A critical basis for consensus and intersubjective confirmation procedures. Qual. Psychol. 8, 407–427. doi: 10.1037/qup0000206

Marková, I. (2003). Constitution of the self: Intersubjectivity and dialogicality. Cult. Psychol. 9, 249–259. doi: 10.1177/1354067X030093006

Marková, I. (2016). The Dialogical mind: Common Sense and Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511753602

Marková, I., and Gillespie, A. (2007). Trust and Distrust: Sociocultural Perspectives. Charlotte, NC: IAP.

Martínez, C., and Tomicic, A. (2018). “From dissociation to dialogical reorganization of subjectivity in psychotherapy,” in Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory and Psychotherapy: Bridging Psychotherapeutic and Cultural Traditions, eds. A. Konopka, H. J. Hermans, and M. M. Gonçalves (London: Routledge), 170–185. doi: 10.4324/9781315145693-12

Martínez, C., Tomicic, A., and Medina, L. (2014). Psychotherapy as a discursive genre: a dialogic approach. Cult. Psychol. 20, 501–524. doi: 10.1177/1354067X14551292

McLeod, J. (1997). Narrative and Psychotherapy. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781849209489

McLeod, J. (2006). Narrative thinking and the emergence of postpsychological therapies. Narrat. Inq. 16, 201–210. doi: 10.1075/ni.16.1.25mcl

*Mellado, A., Martínez, C., Tomicic, A., and Krause, M. (2022a). Dynamic patterns in the voices of a patient diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, and the therapist throughout long-term psychotherapy. J. Constr. Psychol. 1–24. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2022.2082606

*Mellado, A., Martínez, C., Tomicic, A., and Krause, M. (2022b). Identification of dynamic patterns of personal positions in a patient diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and the therapist during change episodes of the psychotherapy. Front. Psychol. 13:716012. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.716012

Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., and Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

Mikes-Liu, K., Goldfinch, M., MacDonald, C., and Ong, B. (2016). Reflective practice: an exercise in exploring inner dialogue and vertical polyphony. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 37, 256–272. doi: 10.1002/anzf.1166

Mongeon, P., and Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106, 213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Neimeyer, R. A. (2000). “Narrative disruptions in the construction of the self,” in Constructions of Disorder: Meaning-Making Frameworks for Psychotherapy, eds. R. A. Neimeyer and J. D. Raskin (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 207–242. doi: 10.1037/10368-009

Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Narrating the dialogical self: toward an expanded toolbox for the counselling psychologist. Couns. Psychol. Quart. 19, 105–120. www.doi.org//10.1080/09515070600655205 doi: 10.1080/09515070600655205

Orange, D. M. (2009). Thinking for Clinicians: Philosophical Resources for Contemporary Psychoanalysis and the Humanistic Psychotherapies. Milton Park: Taylor and Francis.

Orange, D. M., Atwood, G. E., and Stolorow, R. D. (2015). Working Intersubjectively: Contextualism in Psychoanalytic Practice. London: Routledge.

Osatuke, K., and Stiles, W. B. (2006). Problematic internal voices in clients with borderline features: an elaboration of the assimilation model. J. Constr. Psychol. 19, 287–319. doi: 10.1080/10720530600691699

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021a). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88:105906. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021b). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372;n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

*Penttinen, H., Wahlström, J., and Hartikainen, K. (2016). Assimilation, reflexivity, and therapist responsiveness in group psychotherapy for social phobia: a case study. Psychother. Res. 27, 710–723. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1158430

*Piazza-Bonin, E., Neimeyer, R. A., Alves, D., Smigelsky, M., and Crunk, E. (2016). Innovative moments in humanistic therapy I: process and outcome of eminent psychotherapists working with bereaved clients. J. Constr. Psychol. 29, 269–297. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2015.1118712

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., et al. (2006). Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product From the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster, PA: Lancaster University.

*Pote, H., Stratton, P., Cottrell, D., Shapiro, D., and Boston, P. (2003). Systemic family therapy can be manualized: research process and findings. J. Fam. Ther 25, 236–262. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00247

*Råbu, M., McLeod, J., Haavind, H., Bernhardt, I. S., Nissen-Lie, H., and Moltu, C. (2019). How psychotherapists make use of their experiences from being a client: Lessons from a collective autoethnography. Couns. Psychol. Quart. 34, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2019.1671319

Rober, P. (2005). The therapist's self in dialogical family therapy: some ideas about not-knowing and the therapist's inner conversation. Fam. Process 44, 477–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00073.x

Rober, P. (2010). The interacting-reflecting training exercise: addressing the therapist's inner conversation in family therapy training. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 36, 158–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2010.00192.x

Rober, P., Elliott, R., Buysse, A., Loots, G., and De Corte, K. (2008). Positioning in the therapist's inner conversation: a dialogical model based on a grounded theory analysis of therapist reflections. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 4, 406–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00080.x

Salgado, J., and Clegg, J. W. (2011). Dialogism and the psyche: Bakhtin and contemporary psychology. Cult. Psychol. 17, 421–440. doi: 10.1177/1354067X11418545

Seikkula, J. (2008). Inner and outer voices in the present moment of family and network therapy. J. Fam. Ther. 30, 478–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00439.x

Seikkula, J., Alakare, B., Aaltonen, J., Holma, J., Rasinkangas, A., Lehtinen, V., et al. (2003). Open dialogue approach: treatment principles and preliminary results of a two-year follow-up on first-episode schizophrenia. Ethical Hum. Sci. Serv. 5, 163–182.

Seikkula, J., and Arnkil, T. E. (2019). Diálogos abiertos y anticipaciones terapéuticas: Respetando la alteridad en el momento presente. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder Editorial.

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647

*Steen, A., Graste, S., Schuhmann, C., de Kubber, S., and Braam, A. W. (2023). A meaningful life? A qualitative narrative analysis of life stories of patients with personality disorders before and after intensive psychotherapy. J. Constr. Psychol. 36, 298–316. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2021.2015729

Stiles, W. B. (2002). “Assimilation of problematic experiences,” in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients, ed. J. C. Norcross (Oxford University Press), 462–465.

Tseliou, E., Burck, C., Forbat, L., Strong, T., and O'Reilly, M. (2021). The discursive performance of change process in systemic and constructionist therapies: a systematic meta-synthesis review of in-session therapy discourse. Fam. Process 60, 42–63. doi: 10.1111/famp.12560

Valsiner, J. (2002). Forms of dialogical relations and semiotic autoregulation within the self. Theory Psychol. 12, 251–265. doi: 10.1177/0959354302012002633

Valsiner, J. (2007). Culture in Minds and Societies: Foundations of Cultural Psychology. Sage. doi: 10.4135/9788132108504

Valsiner, J. (2014). An Invitation to Cultural Psychology. London: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781473905986

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Walsh, D., and Downe, S. (2005). Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 50, 204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x

Watson, J. C., and Rennie, D. L. (1994). Qualitative analysis of clients' subjective experience of significant moments during the exploration of problematic reactions. J. Counsel. Psychol. 41, 500–509. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.41.4.500

White, M., and Morgan, A. (2006). Narrative Therapy with Children and their Families. Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications.

White, M. C., and Epston, D. (1990). Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. New York, NY: WW Norton and Company.

Zonzi, A., Barkham, M., Hardy, G. E., Llewelyn, S. P., Stiles, W. B., Leiman, M., et al. (2014). Zone of proximal development (ZPD) as an ability to play in psychotherapy: a theory-building case study of very brief therapy. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 87, 447–464. doi: 10.1111/papt.12022