94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 04 March 2024

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1292996

This article is part of the Research TopicPandemic, War and Climate Changes: the Effect of These Crises on Individual and Social Well-beingView all 7 articles

Introduction: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has posed a huge challenge to the career situation of college students. This study aimed to understand the mechanism underlying meaning in life on career adaptability among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: A quantitative method was adopted. In total, 1,182 college students were surveyed using the Meaning in Life Questionnaire, the Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire, the Adult General Hope Scale, and the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale.

Results: There was a significant positive correlation between meaning in life, positive coping styles, hope, and career adaptability. Positive coping styles and hope play a separate mediating role and a chain mediating role.

Discussion: The findings of this study emphasize the importance of meaning in life among college students to improve their career adaptability. Furthermore, positive coping styles and increased levels of hope contribute to the development of career adaptability among college students.

College students' mental health deteriorated rapidly during the COVID-19 outbreak. The impact of the pandemic and related prevention and control measures, coupled with the pressures of study and employment, led to students' maladjustment, which might have a negative impact on their future careers and mental health (Conrad et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). College students are at that stage in their lives where they experience the challenge of finding their “professional self.” Faced with complex and changeable employment situations, they must be well prepared. The key to career preparation for college students is improving their career adaptability, which is regarded as a core ability for career success (Hou et al., 2012). Research has shown that high levels of career adaptability can cushion the impact of environmental stressors, which in turn enhances wellbeing (Ding and Li, 2023). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the factors influencing career adaptability to help students grow under the stress of the pandemic.

Social adjustment is produced by the interaction between the individual and the social environment, in which the individual continuously adjusts their behavior and way of thinking to the changing social environment (Dong et al., 2021). Career adaptability, on the other hand, is an expression of the competence of social adjustment in the vocational field. It is the ability to cope with career changes in their interactions with the career environment (van Vianen et al., 2009). A recent study showed that Chinese college students could not fully adapt in the face of future career changes due to the impact of COVID-19 (Wan et al., 2021). Psychological career phenomenon is a dynamic and endogenous process of change (Savickas, 2005). Intrinsic psychological factors can significantly predict career adaptability (Buyukgoze, 2016). Accordingly, this study explores the intrinsic elements that affect college students' career adaptability, providing implications for enhancing college students' career adaptability and helping them cope with uncertain employment environments so as to improve their wellbeing.

As Frankl (1992) states, meaning in life is a protective factor against painful events. Meaning in life is one of the most important features of wellbeing, with its core functions becoming more prominent during the pandemic (Yildirim and Arslan, 2022). Meaning in life means that the individual can clearly perceive the value of the meaning of existence, which contributes to the achievement of goals (Steger, 2012). The inability to experience meaning in life may have negative effects, such as depression and anxiety, and even extreme behaviors, such as self-injury or suicide (Sun et al., 2022). Meaning in life is relevant to student learning, life satisfaction, and career fields (To et al., 2014; Sari, 2019). The process of making decisions related to meaning in life is one of the adaptation. Maladjustment is manifested by the lack of a clear and meaningful pursuit of life, a feeling of confusion or dissatisfaction with life, and a loss of motivation to find meaning and value in one's existence. A career involves close attention and reflection on one's own survival and development, and it is in the process of career development that meaning in one's life is revealed and fulfilled.

In an epidemic, coping styles are critical to psychological wellbeing in response to the epidemic (Gurvich et al., 2020). A positive coping style is an active behavioral effort made by an individual after a cognitive judgment of changes in the internal and external environments (Zhao et al., 2017). The domain function model suggests that individuals interact with their social environment by adapting to or changing it or regulating themselves to achieve good adaptation and development. Adopting positive coping styles can help to avoid personal failure and distress, thus maintaining good social adjustment and wellbeing (Li et al., 2017; Fullerton et al., 2021).

Coping styles have been shown to mediate the relationship between personal traits (e.g., self-esteem) and career decision-making difficulties (Xu et al., 2022). Previous research suggests that college students' meaning in life has significantly and positively predicted positive coping styles; finding and experiencing meaning in life enables them to cope more positively (Aldwin, 2007). Meaning in life can support the management of negative life events (Chen et al., 2021). Individuals with higher levels of meaning in life tend to adopt positive coping styles to solve problems in response to stressful events. Empirical research has confirmed the relationship between coping styles and adaptation, which is an important predictor of an individual's physical and mental health and environmental adaptability (Barendregt et al., 2015). In students, a positive coping style partially mediates the relationship between meaning in life and the level of social adjustment. Protective coping strategies can weaken or buffer negative psychological effects (Hollister-Wagner et al., 2001; Zhao and Shi, 2016). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: A positive coping style will mediate the relationship between meaning in life and career adaptability.

Hope theory posits that hope is a trait that has a significant impact on general wellbeing and full functioning (Snyder, 2002). Research has shown that hope can help individuals cope with environmental risk factors and overcome traumas, which is important for healthy physical and mental development (Lenz, 2020). The stress-buffering hypothesis states that positive traits moderate the potential negative effects of stress on psychological functioning and optimize event outcomes. This suggests that hope is an important mechanism mediating psychological adjustment (Cohen and Wills, 1985; Hagen et al., 2010). In this ever-changing world, hopeful individuals tend to have higher levels of career wellbeing (e.g., job satisfaction and career adaptability) to prepare for a successful life (Hirschi, 2014; Ding and Li, 2023). Yalçin and Malkoç (2015) found that meaning in life positively predicted hope among college students. College students who pursue meaning in life can increase their levels of hope. There is a significant positive correlation between meaning in life and hope, which is consistent across cultures. Consistent findings have been reported in cohort studies on Turkish adults, Malaysian nurses, and Chinese college students (Vaksalla and Hashimah, 2015; Cheng et al., 2019; Karataş et al., 2021). Individuals who can deeply experience meaning in life and strive to recognize its value have a clear perception of their lives and a sense of value in achieving their goals, thus raising their hopes. Individuals with a strong sense of meaning in life, who know the value of their existence, are better able to regulate negative emotions (Kesebir and Pyszczynski, 2014). Hope may be a mediating variable influencing psychological adjustment. Hope helps individuals achieve their desired goals, supports psychological adjustment, and positively predicts career adaptability (Buyukgoze, 2016; Deniz et al., 2023). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H2: Hope will function as a mediator of the relationship between a sense of meaning in life and career adaptability.

Constructing positive meaning in life can lead to effective social adjustment (Ge et al., 2021). Life that is not guided by meaning negatively impacts career tasks (Baumeister et al., 2013). By actively pursuing and gaining meaning in life, individuals focus on their future directions and show strong adaptability to their careers and lives (Yuen and Yau, 2015). Previous research has shown that positive coping styles are significantly and positively related to levels of hope. Li (2021) conducted a study on Chinese college students and found that positive coping styles contributed to higher levels of hope. Positive coping styles can facilitate access to resources, alleviate negative emotions, and enhance hope in problem solving (Chen, 2016). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: Positive coping styles and hope will act as chain mediators in the relationship between a sense of meaning in life and career adaptability among college students.

Although several studies have explored the impact of meaning in life on psychological adaptation, little research has been conducted on the mechanism underlying the role of meaning in life in career adaptability, especially in the context of COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the occupational psychological health of Chinese college students. Therefore, this study enrolled college students as research participants and conducted an in-depth examination of the inner mechanism underlying the effect of meaning in life on career adaptability, contributing to the enrichment of career adaptability studies and providing suggestions for adjusting college students' career psychology during the post-pandemic period. Figure 1 provides a diagram of the hypothetical model.

Cluster sampling was used in this study. The participants were recruited from six representative universities in Fujian, China. A total of 1,320 questionnaires were distributed; 138 questionnaires were excluded owing to missing answers, and 1,182 valid questionnaires were returned with an effective rate of 89.55%. There were 562 men and 758 women. The participants comprised 404 freshmen, 323 sophomores, 312 juniors, and 143 seniors.

This study used the Meaning in Life Questionnaire, developed by Steger et al. (2006) and revised by Liu and Gan (2010). The scale consists of nine questions (e.g., “I am looking for meaning in my life”). Items on the questionnaire are scored on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). The higher the score, the higher the level of meaningfulness in life for the test. In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.843.

We used the Adult General Hope Scale, originally developed by Snyder et al. (1996) and later translated and revised by Chen et al. (2009). The scale is divided into two dimensions, namely, the motivation factor and the path factor. There are 12 questions on the scale (e.g., “There are multiple solutions to any problem and I can think of many ways to get what is most important to me in life”). For each question, the responses are based on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Four questions regarding goals were used to divert the participant's attention and were not scored. The scale has been used extensively in China for research on hope. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.752.

This study used the Positive Coping Styles subscale of the revised Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire developed by Wang and Zhang (2014), which was based on the Ways of Coping Questionnaire developed by Folkman and Lazarus (1988). The subscale has 12 questions (e.g., “when frustrated in life, I find several different ways to solve problems”) and is scored on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate a greater tendency to adopt a positive coping style. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.913.

This study used the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale, originally developed by Savickas and Porfeli (2012) and adapted for the Chinese population by Hou et al. (2012). The Chinese version has four dimensions: career focus (“I am concerned about my career development”), career control (“I can make my own decisions”), career curiosity (“I am constantly looking for opportunities for personal growth”), and career confidence (“I will continue to solve problems through my own efforts”). Each dimension has six questions. Each response is based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “very unlikely,” 5 = “very likely”). Higher scores on the scale indicate higher levels of career adaptability. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.966.

In 2022, the pandemic was effectively controlled in China, and students gradually returned to college campuses; therefore, we conducted an offline questionnaire survey. Before the commencement of the survey, the study obtained the consent of the relevant authorities. The test was administered as a group, with the questionnaire distributed uniformly, and the instructions and notes for completing the questionnaire were read by the test leader. Before completing the survey, all participants were informed of the purpose of the study and signed a voluntary informed consent form. The process was completed in ~30 min.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0, with the common method bias test, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis as the main methods. Amos 21.0 was used for structural equation modeling and mediating effects testing. With meaning in life as the independent variable and career adaptability as the dependent variable, the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method was used to test the significance of the mediating effects of positive coping style and hope, which were estimated using 95% confidence intervals. An interval estimate of 0 meant that the mediating effect was not significant, whereas the opposite implied that the mediating effect was significant.

Harman's one-way test was used to test for common bias. The results showed that eight factors had eigenvalues >1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 33.66%, which was less than the critical criterion of 40%, indicating that the common method bias of the study was relatively insignificant.

In the Pearson correlation analysis, meaning in life, positive coping styles, hope, and career adaptability were all significantly and positively correlated (r = 0.44, p < 0.001; r = 0.413, p < 0.001; and r = 0.684, p < 0.001). Positive coping styles were significantly and positively associated with hope and career adaptability (r = 0.456, p < 0.001 and r = 0.417, p < 0.001). Hope and career adaptability were positively correlated (r = 0.448, p < 0.01). This finding indicates that when the level of meaning in life, positive coping styles, and hope increases, so does the career adaptability of college students. The results are shown in Table 1.

The measurement model included 4 latent variables (meaning in life, positive coping styles, hope, and career adaptability) and 11 observed variables (latent variable dimensions). Because positive coping styles are unidimensional, to reduce inflation error, a structural factorial algorithm was used to pack positive coping styles into three dimensions. First, a factor analysis was conducted, and the items were ranked from the highest to the lowest loadings and then rotated from the highest to the lowest according to the number of groups. The items with the second-highest loadings were then added sequentially in the opposite direction for balancing (Rogers and Schmitt, 2004). When the sample size is large, the χ2/df criterion may increase. According to Hou et al. (2004) suggestion, the χ2/df criterion is not recommended when the sample size is N ≧ 1000. The measurement model achieved a good fit (RMSEA = 0.065, GFI = 0.965, RMR = 0.014, AGFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.974, and CFI = 0.978). The intermediary model can be further analyzed.

As shown in Table 2, in the results of the regression analysis, controlling for gender and grade, meaning in life positively and significantly predicted career adaptability (β = 0.438, p < 0.001), positive coping style (β = 0.255, p < 0.001), and predicted hope (β = 0.125, p < 0.001) and positive coping style positively and significantly predicted hope (β = 0.281, p < 0.001). When gender, grade, meaning in life, positive coping style, and hope were entered into the regression equation simultaneously, meaning in life, positive coping style, and hope significantly predicted career adaptability.

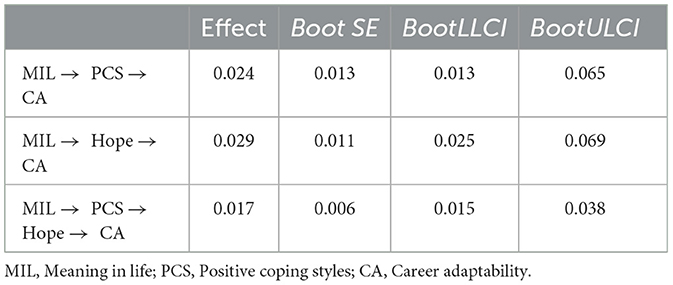

The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method was further used to test the mediating effects, and the results showed that the indirect effects of each path in the model were significant. The results are summarized in Table 3. The mediating effect of positive coping styles and hope was significant, with a total indirect effect value of 0.07. The mediating effect was generated by three chains of mediators. Indirect Effect 1 consisted of meaning in life, positive coping styles, and career adaptability; the indirect effect was 0.024, and the bootstrap 95% confidence interval did not contain 0 (CI = [0.013, 0.065]), indicating that the mediating effect of positive coping styles was significant. Indirect Effect 2 consisted of meaning in life, hope, and career adaptability; the indirect effect was 0.029, and the bootstrap 95% confidence interval did not contain 0 (CI = [0.025, 0.069]), suggesting a significant mediation effect of hope. Finally, Indirect Effect 3 consisted of meaning in life, positive coping styles, hope, and career adaptability, with an indirect effect of 0.017, showing significant mediating effects. The pathways through which college students' meaning in life affected their career adaptability are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3. Mediating effects of positive coping style and hope on the relationship between meaning in life and career adaptability.

This study explored the mediating role of positive coping styles and hope in the relationship between college students' meaning in life and career adaptability. The study findings suggest that meaning in life, positive coping styles, and hope can positively influence college students' career adaptation even during the COVID-19 epidemic phase.

First, the influence of meaning in life on career adaptability was realized through the influence of positive coping styles, which was similar to the findings of Failo et al. (2018) and confirmed H1. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a global public health crisis, and people experienced difficult times. Meaning in life plays an important role in coping with stress in difficult situations (Rosenberg, 2020), such as the pandemic. The domain function model suggests that individuals interact with their social environment by adapting to or changing it or regulating themselves to achieve good adaptation and development. By adopting multiple coping strategies, individuals eventually reach equilibrium with their environment (Zou et al., 2012; Li et al., 2017). Positive coping strategies (such as talking, seeking advice from others, and changing negative perceptions) help individuals improve their ability to deal with problems and create a virtuous cycle (Goodvin and Romdall, 2013). Individuals with a high level of meaning in life are more likely to choose positive ways of coping with life challenges, have positive perceptions in the face of difficulties and setbacks, adopt effective coping strategies, and adapt to changes in the external environment by solving problems or seeking help from the outside, thus enabling them to adapt better (Hajitabar Firouzjaee et al., 2019; Ward et al., 2022).

Our study's findings on the mediating role of hope in meaning in life and career adaptability are consistent with previous research (Korkmaz and Önder, 2019) and confirmed H2. Hope is an important psychological resource for career development and is associated with positive workplace outcomes. Despite the threat of recurring outbreaks, hope remains an important positive trait in reducing negative psychological impacts (Yildirim and Güler, 2021). Individuals with a high level of meaning in life can correctly evaluate their own abilities and values, have a high sense of self-worth, pursue their own life and beliefs about it, and strive for a sense of value in the future, enhancing their cognition and belief in moving toward their goals and experiencing self-improvement and self-fulfillment, thus increasing hope. Individuals with high levels of hope also have a desire for a career, have a positive self-commitment to accept, and integrate changes in the environment more readily, which, in turn, inspires them to be more adaptable to their careers (Wandeler and Bundick, 2011; Hirschi, 2014).

Finally, positive coping styles and hope acted as chain mediators in the relationship between meaning in life and career adaptability, which confirmed H3. This finding suggests that positive coping styles and hope are potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between meaning in life and career adaptability. The stress-buffering model indicated that protective factors (e.g., meaning in life and hope) can diminish the negative impact of risk factors (e.g., epidemics). The level of meaning in life is an important factor for psychological wellbeing, especially during crises (Arslan et al., 2022). If college students actively seek and experience meaning in their lives, they are more likely to adopt positive coping strategies and use effective methods to overcome unfavorable situations, prompting them to pursue their goals, believing in their ability to achieve them, and reaping higher levels of hope when putting into practice. Hope is also considered a protective factor for psychological adaptation during COVID-19 (Seher and Zeynep, 2023). The high levels of hope help individuals prepare for future challenges, have a clear plan for their careers, adapt to career changes in an organized manner, and quickly integrate into a changing career environment, which is also a concrete expression of greater career adaptability. A high level of meaning in life promotes an optimistic attitude toward life and positive behavioral coping patterns to effectively adapt to one's future career. Higher hope indicates better adjustment, adaptability, and strong competence in solving career problems. This suggests that positive coping styles and hope are effective paths for enhancing career adaptability.

Enhancing career adaptability is important to protect the wellbeing of college students. Higher education institutions can adopt targeted strategies to support students' career development during future pandemics.

First, students should be guided to deepen their understanding of the value of life through their experiences of fighting the COVID-19 pandemic to face the unpredictability of a career environment with an optimistic attitude toward life. Students need to be guided in their perception and exploration of meaning in life and to awaken to a sense of responsibility for their future. They should be encouraged to actively seek direction and value in life, closely integrate the meaning of existence with their career, pay attention to their own career development, establish career goals, and keep abreast of all career information.

Additionally, the pandemic has been both a crisis and an opportunity. Coping styles become crucial in the face of career uncertainty (Gurvich et al., 2020). A proactive coping style can help students effectively address career adjustment dilemmas. Students should be encouraged to accept the uncertainty in their careers, develop their ability to identify and seize opportunities, and think of strategies to respond to “opportunity events” to develop their careers. For example, schools can create platforms for students to engage in more social practice activities, where they can deepen their understanding of themselves and their external environment, accumulate career experience, and improve their ability to regulate their careers.

Finally, goals are the central element of hope (Snyder, 2002). Career goals that are too high and beyond students' ability to achieve can leave them frustrated. If goals are too low and easy to achieve, it will reduce students' sense of value and meaning. Therefore, students should be guided to form reasonable expectations regarding their careers and refine their goals.

This study has several limitations. First, most senior-year students were enrolled in off-campus internships and not at school. This resulted in a small sample size of senior-year students when the questionnaire was collected. This may affect the applicability of the results. In the future, a senior-year student group should be selected as a sample to verify the reliability of the results and expand the generalizability of the findings. Second, there may be other factors influencing career adaptability, such as employment pressure and social support, and these factors can be explored in depth in future studies. Additionally, we used a cross-sectional study to examine the factors affecting career adaptability; however, we cannot judge the causality between the variables. Future longitudinal follow-up studies should be conducted to better understand the relationship between meaning in life, positive coping styles, hope, and career adaptability. It is also important to compare the results during the pandemic with the end of the epidemic to explore the stability of the relationship between the four variables. Finally, the research method of the questionnaire survey may have been influenced by bias. There may be problems in answering truthfully, which may have affected the validity of the research. Future studies should adopt both experimental and qualitative methodologies to expand and improve on this area of research.

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on people's studies and work will probably continue for some time. In this study, we found that positive coping style and hope act as a chain mediator between meaning in life and career adaptability. These findings show that meaning in life, positive coping style, and hope are important characteristics that enhance career adaptability. Furthermore, the findings have implications for career education for college students in the post-epidemic era or any future pandemic.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Longyan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ZL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Social Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (Grant Number FJ2021C119) and the project of 14th 5-Year Plan of Educational Science in Fujian Province, China (FJJKBK23-117).

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aldwin, C. M. (2007). Stress, Coping, and Development: An Integrative Perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Arslan, G., Yildirim, M., Karata,ş, Z., Kabasakal, Z., and Kilinç, M. (2022). Meaningful living to promote complete mental health among university students in the context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health. Addict. 20, 930–942. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00416-8

Barendregt, C., Van derLaan, A., Bongers, I., and Van Nieuwenhui-zen, C. (2015). Adolescents in secure residentia1care: the role of active and passive coping on general well-being and self-esteem. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 24, 845–854. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0629-5

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Aaker, J. L., and Garbinsky, E. N. (2013). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. J. Posit. Psychol. 8, 505–516. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.830764

Buyukgoze, K. A. (2016). Predicting career adaptability from positive psychological traits. Career Dev. Q. 64, 114–125. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12045

Chen, C. (2016). The role of resilience and coping styles in subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Asia. Pac. Educ. Res. 25, 377–387. doi: 10.1007/s40299-016-0274-5

Chen, C. R., Shen, H. Y., and Li, X. Z. (2009). Reliability and validity of adult dispositional hope scale. Chine. J. Clin. Psychol. 1, 24–26.

Chen, Q., Wang, X. Q., He, X. X., Ji, L. J., Liu, M. F., and Ye, B. J. (2021). The relationship between search for meaning in life and symptoms of depression and anxiety: Key roles of the presence of meaning in life and life events among Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 282, 545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.156

Cheng, J. W., Yang, R. D., Guo, K. D., Yan, J. X., and Ni, S. G. (2019). Family function and hope among vocational college students: Mediating roles of presence of meaning and search for meaning of life. Chine. J. Clin. Psychol. 27, 577–581. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.10053611.2019.03.030

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Conrad, R. C., Koire, A., Pinder-Amaker, S., and Liu, C. H. (2021). College student mental health risks during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications of campus relocation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 136, 117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.054

Deniz, M. E., Satici, S. A., Okur, S., and Satici, B. (2023). Relations among self-control, hope, and psychological adjustment: A two-wave longitudinal mediation study. Scand. J. Psychol. 6, 728–733. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12927

Ding, Y., and Li, J. (2023). Risk perception of coronavirus disease 2019 and career adaptability among college students: the mediating effect of hope and sense of mastery. Front. Psychol. 14, 1210672. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1210672

Dong, Y., Wang, H., Luan, F., Li, Z., and Cheng, L. (2021). How children feel matters: teacher-student relationship as an indirect role between interpersonal trust and social adjustment. Front. Psychol. 11, 581235. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.581235

Failo, A., Beals-Erickson, S. E., and Venuti, P. (2018). Coping strategies and emotional well-being in children with disease-related pain. J. Child Health Care 22, 84–96. doi: 10.1177/1367493517749326

Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 466–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.466

Fullerton, D. J., Zhang, L. M., and Kleitman, S. (2021). An integrative process model of resilience in an academic context: Resilience resources, coping strategies, and positive adaptation. Plos One 16, e0246000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246000

Ge, Y., Shuai, M. Q. J, Luo, J., Wenger, L., and Lu, C. Y. (2021). Associated effects of meaning in life and social adjustment among Chinese undergraduate students with left-behind experiences in the post-epidemic period. Front. Psychiatry 12, 771082. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.771082

Goodvin, R., and Romdall, L. (2013). Associations of mother-child reminiscing about negative past events, coping, and self-concept in early childhood. Infant Child Dev. 22, 383–400. doi: 10.1002/icd.1797

Gurvich, C., Thomas, N., Thomas, E. H., Hudaib, A. R., Sood, L., Fabiatos, K., et al. (2020). Coping styles and mental health in response to societal changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 12, 20764020961790. doi: 10.1177/0020764020961790

Hagen, K. A., Myere, B. J., and Ms, V. H. M. (2010). Hope, social support, and behavioral problems in at - risk children. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 75, 211–219. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.211

Hajitabar Firouzjaee, M., Sheykholreslami, A., Talebi, M., and Barq, I. (2019). Impact of the meaning in life on students' School Adjustment by mediating problem-focused coping and self-acceptance. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 16, 59–76. doi: 10.22111/jeps.2019.4944

Hirschi, A. (2014). Hope as a resource for self-directed career management: investigating mediating effects on proactive career behaviors and life and job satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 15, 1495–1512 doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9488-x

Hollister-Wagner, G. H., Foshee, V. A., and Jackson, C. (2001). Adolescent aggression: models of resiliency. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 31, 445–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02050.x

Hou, J. T., Wen, Z. L., and Chen, Z. J. (2004). Structural Equation Model and Its Applications. Beijing: Educational Science Press.

Hou, Z. J., Leung, S. A., Li, X., Li, X., and Xu, H. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale-China form: Construction and initial validation. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.006

Karataş, Z., Uzun, K., and Tagay, Ö. (2021). Relationships between the life satisfaction, meaning in life, hope and COVID-19 fear for Turkish adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 12, 778. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633384

Kesebir, P., and Pyszczynski, T. (2014). “Meaning as a buffer for existential anxiety,” in Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology, eds A. Batthyany, and P. Russo-Netzer (New York, NY: Springer).

Korkmaz, O., and Önder, F. C. (2019). Relationship between life goals and career adaptability: Examining the mediating role of hope. J. Educ. Sci. 44, 59–76. doi: 10.15390/EB.2019.8380

Lenz, A. S. (2020). Evidence for relationships between hope, resilience, and mental health among youth. J. Couns. Dev. 99, 96–103. doi: 10.1002/jcad.12357

Li, C. N., Sun, C. C., Xu, E. Z., Gu, J. J., and Zhang, Q. C. (2017). The influence of coping strategies and pressure on social adjustment in secondary school students: longitudinal mediation models. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 33, 172–182. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.02.06

Li, Y. H. (2021). The correlation between the mental health, coping style of college student: The intermediary role of hope perception. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 29, 1297–1300. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.06.036

Liu, S. S., and Gan, Y. Q. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire. Chin. Ment. Health 24, 478–482. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2010.06.021

Rogers, W. M., and Schmitt, N. (2004). Parameter recovery and model fit using multidimensional composites: a comparison of four empirical parceling algorithms. Multivar. Behavl. Res. 39, 379–412. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3903_1

Rosenberg, A. R. (2020). Cultivating deliberate resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 174, 817. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1436

Sari, S. V. (2019). Attaining career decision self-efficacy in life: Roles of the meaning in life and the life satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 38, 1245–1252. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9672-y

Savickas, M. L. (2005). “The theory and practice of career construction,” in Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, eds R. W. Lent and S. D. Brown (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons), 42–70.

Savickas, M. L., and Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt- abilities scale: construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

Seher, A., and Zeynep, G. A. (2023). The role of cognitive flexibility and hope in the relationship between loneliness and psychological adjustment: a moderated mediation model. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 40, 74–85. doi: 10.1080/20590776.2022.2050460

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol. Inq. 13, 249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., and Ybasco, F. C. (1996). Development and validation of the state hope scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psycho. 70, 321–335. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321

Steger, M. F. (2012). Making Meaning in life. Psychol. Inq. 23, 381–385. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2012.720832

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., and Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns Psychol. 53, 80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

Sun, F. K., Wu, M. K., Yao, Y., Chiang, C. Y., and Lu, C. Y. (2022). Meaning in life as a mediator of the associations among depression, hopelessness and suicidal ideation: a path analysis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 29, 57–66. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12739

To, S. M., Tam, H. L., Ngai, S. S. Y., and Sung, W. L. (2014). Sense of meaningfulness, sources of meaning, and self-evaluation of economically disadvantaged youth in Hong Kong: Implications for youth development programs. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 47, 352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.10.010

Vaksalla, A., and Hashimah, I. (2015). How hope, personal growth initiative and meaning in life predict work engagement among nurses in Malaysia private hospitals. Int. J. Arts Sci. 8, 321–378.

van Vianen, A. E. M., De Pater, I. E., and Preenen, P. T. Y. (2009). Adaptable careers: maximizing less and exploring more. Career Dev. Q. 57, 298–309. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2009.tb00115.x

Wan, H. Y., Yu, J. Q., Yan, N. Q., and Huang, J. H. (2021). Relationships between learning burnout and Internet addiction among undergraduates during the novel coronavirus pneumonia:Mediating effect of career adaptability. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 5, 695–701. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2021.05.012

Wandeler, C. A., and Bundick, M. J. (2011). Hope and self-determination of young adults in the workplace. J. Posit. Psychol. 6, 341–354. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2011.584547

Wang, D. W., and Zhang, J. X. (2014). Factor analysis of the simplified coping style questionnaire. J. Shandong Univ. 52, 96–100.

Ward, S., Womick, J., Titova, L., and King, L. (2022). Meaning in life and coping with everyday stressors. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 3, 1461672211068910. doi: 10.1177/01461672211068910

Xu, N., Xu, B. B., Hou, X. H., and Wang, S. Q. (2022). Future time perception and career decision-making difficulties of college students:the chain mediating role of self-esteem and positive coping style. Chin. Health.Psychol 12, 1893–1897. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.12.026

Yalçin, I., and Malkoç, A. (2015). The relationship between meaning in life and subjective well-being: Forgiveness and hope as mediators. J. Happiness Stud. 16, 915–929. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9540-5

Yildirim, M., and Arslan, G. (2022). Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 41, 5712–5722. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2

Yildirim, M., and Güler, A. (2021). Coronavirus anxiety, fear of COVID19, hope and resilience in healthcare workers: a moderated mediation model study. Health Psychol. Rep. 9, 388–397. doi: 10.5114/hpr.2021.107336

Yuen, M., and Yau, J. (2015). Relation of career adaptability to meaning in life and connectedness among adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Vocat. Behav. 91, 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.10.003

Zhang, X., Huang, P. F., Li, B. Q., Xu, W. J., Li, W., and Zhou, B. (2021). The influence of interpersonal relationships on school adaptation among Chinese university students during COVID-19 control period: multiple mediating roles of social support and resilience. J. Affect Disord. 285, 97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.040

Zhao, L., Zhang, X., and Ran, G. (2017). Positive coping style as a mediator between older adults' self-esteem and loneliness. Soc. Behav. Pers. 45, 1619–1628. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6486

Zhao, Y. X., and Shi, H. Y. (2016). A study on the relationship between family function, coping style and social adaption of undergraduates. Adv. Psychol 6, 1318–1322. doi: 10.12677/AP.2016.612166

Keywords: meaning in life, career adaptability, positive coping styles, hope, COVID-19

Citation: Lin Z (2024) The influence mechanism underlying meaning in life on career adaptability among college students: a chain intermediary model. Front. Psychol. 15:1292996. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1292996

Received: 12 September 2023; Accepted: 31 January 2024;

Published: 04 March 2024.

Edited by:

Bernd Roehrle, Philipps University of Marburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Elizabeth Tricomi, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhengzheng Lin, d2VucnVhbjIwMjBAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.