- 1School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia

- 2Department of Business Education, The University of Chenab, Gujrat, Pakistan

- 3Department of Management Science, National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 4Department of Business Administration, College of Business and Administration, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 5School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang, Malaysia

Purpose: We seek to understand why and how leaders’ actions that are positive from organizational perspectives, drive to engage employees in cheating behaviors.

Design/methodology/approach: The proposed mediated moderation model was tested in two separate studies, study 1 and study 2, with data collected from police officers and employees of Islamic banking respectively, and then analyzed with Mplus for random coefficient models for direct effects, indirect effects, and for mediated moderation.

Findings: It was found that leaders’ ambitions may enhance performance pressure on the subordinates, which in turn promotes their cheating behavior. Overall, we found that the traditional view of ambition theory only emphasizes good mechanisms such as motivation. However, to integrate with a social identity perspective, ambition would also cause pressure and pressure rather than motivation. Additionally, leaders’ ambitions are more strongly and positively related to the performance pressure and cheating behaviors of employees when subordinates also have high leader identification. The findings of this research suggested that leaders’ positive workplace behavior could also spawn subordinates’ unethical behaviors.

Practical implications: Through this research, we can help policymakers understand that leaders’ positive desire in general and ambition, in particular, may not be necessarily associated with subordinates’ positive behaviors. Our results revealed that internalized with performance pressure, the leaders’ ambition is associated with subordinates’ cheating behavior. The findings of this research will help policymakers understand what might be promoting unethical behavior of employees. The cheating behavior of employees is not a singular level phenomenon of subordinates, it could also be triggered by contextual factors. Therefore, in developing policies for reducing the chance of cheating at work, the policymakers should also focus on the contextual factors that might be promoting cheating.

Originality/value: Ambitious leaders tend to demonstrate high performance, also, performance pressure literature focuses efforts of the employees toward high performance. The dark side of these lines of researches is still underexplored. We shifted the conventional focus of understanding to the positive side of ambition and performance pressure by explaining the potential cost in the form of employees’ enhanced cheating behavior. The interplay between the relationship between leaders’ ambition and subordinates’ perception of leader identification also enhanced our understating about the boundary condition of the relationship between leaders’ ambition, performance pressure, and cheating behavior of subordinates.

Introduction

Cheating behavior refers to unethical acts intended to create unfair advantages or help to attain benefits that an employee would not otherwise be entitled to receive (Shu et al., 2011) is associated with the financial drain of the organizations (Meyer, 2010). Frequently cited examples of cheating behavior include lying to customers, over-reporting, under-reporting, scamming, and deceiving to advance personal interest by creating unfair advantages. The upward trend of cheating has been found in almost every sector from education to manufacturing (McCabe, 2016; Thompson, 2016; Bretag et al., 2018) and from financial to public services (Egan, 2016; Belle and Cantarelli, 2017). Scholars have long recognized cheating as a singular level phenomenon of people (Williamson, 1984; Higgins, 1997) triggered by personal traits (Hilbig and Zettler, 2015). Yet the rise in cheating behavior has made researchers think contextual cues that might affect cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018; Spoelma, 2021).

Scholars have speculated that certain factors within organizations promote employees’ ethical behaviors (Treviño et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2018). For instance, leaders’ ethical conduct plays an important role in determining employees’ ethical conduct (Paterson and Huang, 2018). They implement ethical and moral standards that their followers often demonstrate (Krasikova et al., 2013). Their workplace actions “trickles down” to followers at lower levels (Schaubroeck et al., 2012; Adeel et al., 2019a, 2022a); leaders’ positive actions normalize followers unethical intentions (van Gils et al., 2015), and buffers the unethical behavior of employees (Braun and Hornuf, 2018). However, negative actions are translated into followers’ unethical intentions and behaviors (Schyns and Schilling, 2013). While this approach can be useful to explain leaders’ deeds and ethical behavior of subordinates. Scholars are beginning to ask why and how leaders’ actions, which are positive from organizational perspectives, drive to engage employees in unethical behaviors (van Gils et al., 2015).

Our research addresses this issue, taking leaders’ ambition as a desired workplace behavior (Steffens et al., 2018), we develop and test a model that how leaders’ ambition is translated into employees’ cheating behavior. Ambitious leaders seize the opportunities to change things for the betterment (Balda and Mora, 2011), they achieve high goals (McClelland, 1975), which ultimately benefit organizations in the form of high employee commitment and better performance (Steffens et al., 2018). Drawing on ambition theory (Schlesinger, 1966), this research hypothesized leader ambition is a positive workplace action (Steffens et al., 2018) to enhance the cheating behavior of employees. Past research has consistently shown that leaders’ high ambition tend to spawn positive behavior of followers, such as energizing followers for their full potential (Hobfoll, 2011), influencing followers interests (Dilchert, 2007), internalizing followers self-concept (DeRue et al., 2009), and fueling force of betterment (Caro, 2002). In essence, a leader’s ambition would provide all the positive energies that followers need to behave positively at work. However, these studies have ignored the fact that although leaders’ ambition drives followers to engage in positive workplace behaviors, there could be potential risks of being unethical by demonstrating cheating behavior due to the leader’s high ambition.

Followers of an ambitious leader tend to demonstrate high levels of achievements (Dilchert, 2007) or are more result-oriented (Winsborough and Sambath, 2013; Sieberer and Müller, 2017; Nagel et al., 2020), to some extent, these studies support that with high ambitious leader followers have to take more ownership and pressure to achieve leaders’ goals. Thus, when leaders at organizations are driven to succeed, their followers feel more pressure to achieve organizational goals. Based on these arguments, this study uses ambition theory (Schlesinger, 1966) to hypothesize that leaders’ ambition increases performance pressure on employees which in turn enhances chances of employees’ cheating behavior. Social identity theory (Ashforth and Mael, 1989) predicts that employees develop social identification within their organizations when they attribute belongingness to others based on some attraction or the attributes and characteristics they use to define themselves (F. A. Mael and Tetrick, 1992). To reveal boundary condition of the relationship between leader ambition and employees’ performance pressure, in this research, building on social identity theory, we propose and test moderating effect of subordinates’ leader identification on this relationship. To summarizing, we propose a mediated moderation model to systematically analyze how leaders’ ambition is related to employees’ cheating behavior through performance pressure and the boundary conditions thereof. This research will help organizations understand cheating behavior as triggered by ambitions of the leaders thereby developing strategies for normalizing performance pressure and for lowering intentions of employees to cheat at work.

This research intends to make several contributions. We address recent calls to uncover the contextual factors within organizations that enhance employees’ cheating behavior (Treviño et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2018). In emerging research on cheating behavior, scholars have speculated that certain organizational factors promote the employees unethical intentions; for instance researcher speculated that several environmental factors contribute to self-interest which may further promote unethical behaviors (Spoelma, 2021; Hillebrandt and Barclay, 2022; Kamran et al., 2022; Malesky et al., 2022). Similarly in the same vein, other researchers found that employees intentions to cheat at work are enhanced when employees need to protect self-interest (Mitchell et al., 2018; Spoelma, 2021). Our study provides unique insight into cheating’s emerging research that how leaders’ positive actions are translated into employees’ cheating behavior. Recent literature has provided evidence that emotions, cognition, and performance goals are translated into cheating intentions (Welsh and Ordóñez, 2014; Mitchell et al., 2018). We shed light on the leadership side that is translating into followers’ cheating behavior. Additionally, the traditional view of ambition only emphasizes the good mechanism such as motivation (Steffens et al., 2018), however, to integrate with the social identity perspective, ambition would also cause pressure, rather than motivation.

Our research also provides unique insights by offering a needed explanation of the antecedents that promote performance pressure. More specifically, the antecedents are not singular in nature and have roots within the organizations. The presumed benefit of performance pressure is to motivate individuals to increase their efforts for higher achievements which ultimately benefit organizations. We also contributed to the list of negative consequences of performance pressure by offering employees’ cheating behavior as affected by both leaders’ ambition and performance pressure. Finally, we investigated leaders’ actions and followers’ responses in a single study, which is rarely investigated in management research (Day, 2014; Bastardoz and Van Vugt, 2019).

Literature review and hypotheses

Understanding cheating behavior

Cheating at work is an employee’s unethical act for creating unfair advantages and attaining benefits (Shu et al., 2011). These unfair acts of employees cost billions of dollars to the organizations (GRTB–Global Retail Theft Barometer, 2016), thus, organizations seek to find ways to reduce cheating. Cheating and unethical behaviors were traditionally conceptualized as individual-level psychological phenomena; therefore, the focus of research remained with understating and investigating psychological factors that contribute to employees’ cheating and unethical behavior (Hsiao and Yang, 2011). Employee cheating is a result of cost and benefit calculation (Becker, 1993) that includes three main predictors (i) expected benefits (ii) the possibility and probability of cheating detection (iii) and the cost in the form of punishment and its magnitude in case of cheating detection. The empirical evidence linking these three predictors with cheating differ in their impact (Nagin and Pogarsky, 2003). The behavioral ethical literature concerns with the influence of intervening factors that influence cheating behavior of employees; contextual factors, professional background, cultural context, and the relational ties between leaders and the followers predict cheating at work (Trevino, 1986; Brass et al., 1998; Treviño et al., 2006; Cohn et al., 2014). The predominant part of this line of research has focused on the role of leadership in promoting or impeding cheating at work (Djawadi and Fahr, 2015; Paterson and Huang, 2018). Based on the behavioral integrity of the leaders as perceive by the followers (Kiersch and Byrne, 2015), leaders play a vital role in explaining and promoting desirable outcomes and preventing the outcomes that are not required (Leroy et al., 2012), thus, affecting cheating behavior of their subordinates (Cianci et al., 2014; Braun and Hornuf, 2018).

Performance pressure and cheating behavior

Performance pressure is defined as the factors that increase the magnitude of performing well at workplaces (Baumeister, 1984). The employees who feel performance pressure at their workplaces believe that high performance is required at work and the efforts to perform high will be linked to their distal consequences and that their efforts to perform workplace tasks will be scrutinized in a high-stakes manner (Gutnick et al., 2012; Sheng and Fan, 2022). Meeting high demands will lead to enhanced standing of the individuals; however, failure to meet the workplace’s high demands may put him/her in danger at work. Researchers have found that the performance pressure is a threatening experience for the employees as it questions the current efforts of the employee concerning high performance demand (Sitkin et al., 2011), indicating the inadequacy of current performance for attaining the required demanded output (Zhang et al., 2017). The employees then try to elevate their efforts to meet the demanded output by stretching their capabilities, which at times are impossible to manage (Baumeister, 1984; Shalley and Perry-Smith, 2001).

In addition to performance pressure as a work demand, employees well understand that workplace efforts are linked with distal consequences (Gutnick et al., 2012), not meeting the high demands of the workplace may bring undesired negative outcomes. Employees sometimes engage in promoting and protecting self-interest by engaging in unethical practices and fabricating performance levels. In contemporary organizations, employees feel more pressure, employers are more demanding, they pressure their employees to elevate their performance ever increasing (DeZoort et al., 2006; Gutnick et al., 2012). Thereby, employees feel more pressure to be seen as performers at work by raising their performance level, otherwise, they have to face undesirable consequences, such as salary deductions, contract terminations, and/or some sort of punishments (Gutnick et al., 2012).

Researchers have also found that when employees perceive their work task based on performance goals, they are motivated to engage in unethical behaviors and they are also motivated to exaggerate their work performance (Schweitzer et al., 2004; Welsh and Ordóñez, 2014). Thereby, by putting pressure on employees to enhance their performance, the organizations might be inadvertently and actively promoting cheating behavior of their employees (Chen and Chen, 2021; Campos et al., 2022). The belongingness to a social work group also emerges as a predictor of performance pressure on employees, the threat of being excluded from a social work group makes anger a likely response, thereby promoting employees’ cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018; Spoelma, 2021). Thereby, performance pressure threatens employees, elicits self- interests, and promotes cheating behavior of employees as a way to obtain undeserved benefits by fabricating performance level for addressing increasing performance demands. Because, by nature, the performance pressure threaten employees and produces paradoxical reactions (Baumeister, 2002), when employees experience performance pressure, their unethical intentions increases (Deng et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022).and their cheating behavior is enhanced (Mitchell et al., 2018; Spoelma, 2021).

Leaders’ ambition and subordinates’ performance pressure

Ambition is a desire to achieve ends, especially, ends like success, power, and wealth (Hansson et al., 1983). Scholars have taken different theoretical perspectives to explain ambition (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012), the central to all of these different theoretical perspectives is the aspirational nature of ambition- the motivational process that energizes individuals for the attainment of outcomes. Ambition theory (Schlesinger, 1966) explains the ambition of a person as the degree to which a person seems socially self-confident, leader-like, competitive, and energetic (Hogan et al., 2007). These persistent efforts to strive for success, attainment, and accomplishment (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012) benefit organizations by enhancing a high level of commitment and performance (Steffens et al., 2018). Generally, it has been conceptualized as a psychological level phenomenon and treated as an individual-level trait (Hansson et al., 1983), however, ambition has also been affected by socioeconomic factors (Sewell et al., 2003). Recent research has found that ambition by definition, is a facet of conscientiousness or extroversion (Hogan et al., 2007; Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). Ambition is an extroversion facet of an individual’s personality (Hogan et al., 2007), and the leaders with this feature (Digman, 1990) show more consistency in their effort to perform better along with their followers (Judge et al., 2002).

The tradition in psychological research is to explain ambition with respect to goals, plans, and accomplishments (Locke and Latham, 2002), however, ambition is more about attaining than achieving (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). Ambitious individuals with strive to achieve high targets in life, will put more efforts to achieve a higher level of education (Meyer, 1977), will have a satisfying career and social status, and receive better grades (Kim and Schneider, 2005). To achieve higher levels of financial rewards is also high for ambitious individuals, one of the core features of ambitious individuals is having a desire to achieve financial success, thus, with the achievement of personal wealth they signal that they have succeeded and attained success (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). A high level of occupational success is also a sign of attainment and attractiveness for ambitious individuals, therefore, individuals with high ambitions translate their intentions to perform into practice (Rhodes et al., 2005). Organizations also set ambitious goals to shorter duration of unemployment (Kanfer et al., 2001), more financial success (Nickerson et al., 2007), and highly creative achievement of their employees (Helson and Srivastava, 2002). Overall, research has established that ambitious individuals- due to their aspirational nature, put more effort into their activities and attain high targets in life (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012).

Leaders’ role remained significant for performance pressure, employee’s actual performance and un-ethical behavior (Zhang et al., 2021, 2022; Liu et al., 2022). Ambitious leaders are needed by organizations (Steffens et al., 2018). They do whatever it takes to grow their business even at the cost of some necessary sacrifices (Gundry and Welsch, 2001). Ambitious leaders seize the opportunities to change things for the betterment (Balda and Mora, 2011), they achieve high goals (McClelland, 1975), which ultimately benefit organizations in the form of high employee commitment and better performance (Steffens et al., 2018). Followers of an ambitious leader tend to demonstrate high levels of achievements (Dilchert, 2007) or are more result-oriented (Winsborough and Sambath, 2013; Sieberer and Müller, 2017), to some extent, these studies support that with high ambitious leader followers have to take more ownership and pressure to achieve leaders’ goals. Thus, employees working with an ambitious leader must feel pressure to perform their routine tasks.

H1: There is a positive association between leaders’ ambition and subordinates’ performance pressure.

The moderating role of leader identification

Social identity theory (Ashforth and Mael, 1989) has been used to explain employees’ self-identification with their organizations, groups, and with their leaders (Chen et al., 2015; Chughtai, 2016; Nason et al., 2018). The core premise in social identity theory is identifying and belongingness of an individual with others based on some attributes, characteristics, or attractions. The identification with the leader is a relational self-based on the characteristics they see in the leaders they use to define themselves (Wang and Rode, 2010). The identification with a leader works from two sides: follower recognize that he or she shares similar characteristics with the leader, and/or desire to change his or her self-concept so that his or her values and beliefs become similar to the leader (Pratt, 1998). Leader identification reflects the extent to which followers believe that their leader is self-defining (Kark et al., 2003); that is the perception of the followers’ oneness with the leader (Ashforth et al., 2016). In one of the few studies to investigate leader identification, researchers found that when followers have high identification with their leader, they exert more effort to meet the expectations of their leader for creativity (Wang and Rode, 2010). It appears that investigating how identification with a leader relates to a leader’s ambitions is essential for a proper understanding of the effects of leaders’ ambition. Extending our previous discussion on the topic, here we suggest that followers’ perception of identification with their leader integrate with their leaders’ ambition for the magnitude of performance pressure.

Researchers have stated that followers’ identification with their leader leads individuals to experience the minimal distinction between themselves and their leader (Andersen and Chen, 2002), enhancing commitment and consideration toward their leader (Sluss and Ashforth, 2007). Followers with high identification with their leaders perceive that acting for the benefits and need of their leader is acting for their benefits and needs; they become more sensitive toward the behavior of their leaders, success of their leaders, expectations of their leaders, and needs of their leader (Berscheid and Reis, 1998; Van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Accordingly, we posit that followers’ identification with their leader will play a vital role in explaining and determining whether leaders’ ambition is associated with performance pressure that employees feel at workplaces. Research has proposed that followers’ identification with their leaders must augment with leaders’ behavior for a higher level of influence on the followers’ performance (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Wang and Rode, 2010).

H2: The positive association between leaders’ ambition and subordinates’ performance pressure is strengthened when subordinates also have high levels of leader identification.

The mediating role of performance pressure

Previous studies on leaders’ ambition suggest that the motivational process of aspiration energizes individuals to evaluate their own competence and set progressive goals to achieve desired results with high growth strategies (Gundry and Welsch, 2001; Judge et al., 2002; Hogan et al., 2007). Leaders are considered to be a continuous source of pressure for the employees (Kamran et al., 2022; Sheng and Fan, 2022). Ambitious leaders require high performance from their subordinates, thereby employees may feel more performance pressure. Researchers found that ambitious leaders set high performance goals with higher growth strategies to achieve higher goals (Winsborough and Sambath, 2013). Consequently, increasing the motivational basis for professional and organizational commitment to achieve high performance goals (Desrochers and Dahir, 2000), thereby, enhancing performance pressure on the followers (Roberts et al., 2007; Winsborough and Sambath, 2013).

We contend that performance pressure may mediate the relationship between leaders’ ambition and subordinates’ cheating behavior. As noted above, more ambition of the leaders is associated with high performance pressure of the followers because high ambition and expectations of the leaders are translated into followers’ high attainment, accomplishments, and need for generalized striving for success (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012) and because it may create an impression of the subordinates’ high achievement among their supervisors (Locke and Latham, 2002). In addition, there is accumulating evidence that subordinates perform better when they have positive workplace associations (Adeel et al., 2019b), when they define themselves as identical to their leaders (Wang and Rode, 2010), and when their leaders are high in ambitions (Steffens et al., 2018).

Although ambition is often not generally viewed as having negative consequences, it is still unclear whether it has vice or virtue consequences (Pettigrove, 2007; Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). In particular, some researchers have argued that the leaders’ ambition has a positive effect on the behavior of their subordinates (Locke and Latham, 2002; Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012) when driven by identification of the subordinates with their leaders (Wang and Rode, 2010). Hence, here we believe that identification with leaders may influence leaders’ ambition on the cheating behavior of employees in the same way as it influences the effects of leaders’ ambition on performance pressure. Consequently, we contend that identifying with one’s leader may interrupt the performance pressure as triggered by the leader’s ambition. Therefore, we predict a mediated moderation as depicted in the hypothesis below.

H3: Performance pressure mediates the interactive effects of leaders’ ambition and subordinates’ leader identification on subordinates’ cheating behavior.

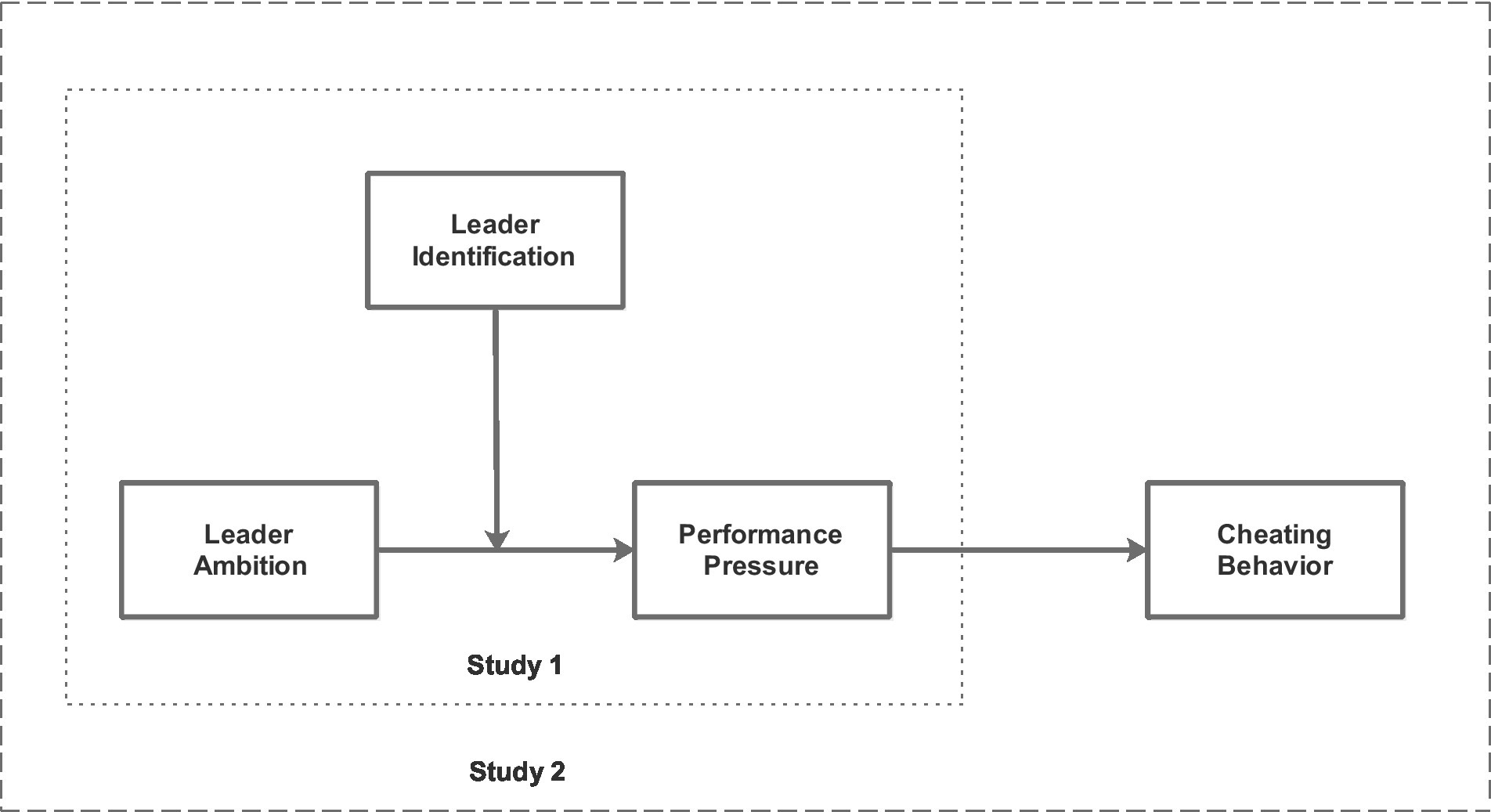

Data for the hypothesized relationships was collected in two separate studies. Since in study 1 we could not collect data for employees’ cheating behavior (police officers), we only tested hypotheses 1 and 2 in this study. In study 2, we collected data for all of our Islamic banking professionals’ variables and examined all the hypotheses. The key theoretical relationships are presented in Figure 1. Previous researchers have used non-probability sampling by recruiting a variety of adequate participants (Erdogan et al., 2015; Adeel et al., 2022b), therefore, following previous research we have also used convenience sampling.

Study 1

Sample and data collection

Data for this study was sampled from a police academy in Punjab province. The officers were on the job training for intermediate and upper-class courses with 16 weeks duration. Studying performance pressure and its relationship with leader ambition and leader identification on a sample of police officers appears practically interesting due to the high stressful performance demand of this job (Romosiou et al., 2018; Zempi, 2018) and the relevance of the research question with the context of this study. In February 2019, an Initial email was sent to all of the 437 officers who were part of the training center. Three hundred and thirty one showed their willingness via return email, we then sent a questionnaire to those willing to participate in this study. The initial response was received from 218 officers and all of their 6 training managers. After deleting data with missing values and mismatched with instructors’ response, our final sample yielded 196 from officers and 6 from their relevant instructors with a response rate of 59 and 100%, respectively. This final sample included officers from (criminal investigation, security police, and police command). In our final qualified sample, over half of the respondents (51%) with; the average age of participants was 22.81 years.

Measures

Leaders’ Ambition: We measured leaders’ ambition with five items ambition scale (Duckworth et al., 2007) adapted by (Rodriguez et al., 2013). Course instructors responded on this -reporting measure of leaders’ ambition with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all like me to 5 = very much like me. Scale items are “I aim to be the best in the world at what I do,” “I am ambitious,” “Achieving something of lasting importance is the highest goal in my life,” “I think achievement is overrated,” and “I am driven to succeed” (α = 0.86).

Performance Pressure: We measured performance pressure (Mitchell et al., 2018) with four items five-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. Officer provided their response for this self-reporting measure. Sample scale items are “The pressures for performance in my workplace are high” and “If I do not produce at high levels, my job will be at risk” (α = 0.92).

Leader Identification: We measured leader identification (Kark et al., 2003; Wang and Howell, 2012) with six items five-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. Officers provided this response on this self-reporting measure. The sample item is “My supervisors’ successes are my successes” (α = 0.78).

Control Variables: Research has shown that demographic variables influence the perception of pressure (Kish-Gephart et al., 2010). Therefore, we controlled for subordinates’ gender, age, and organizational tenure. Researchers have argued that moral identity may also affect the performance pressure (Chen and Chen, 2021) and moral development and behaviors (Kohlberg and Power, 1981; Aquino and Reed, 2002). Therefore, we controlled for moral identity in both of our studies with five items five-point likert type scale (Aquino and Reed, 2002).

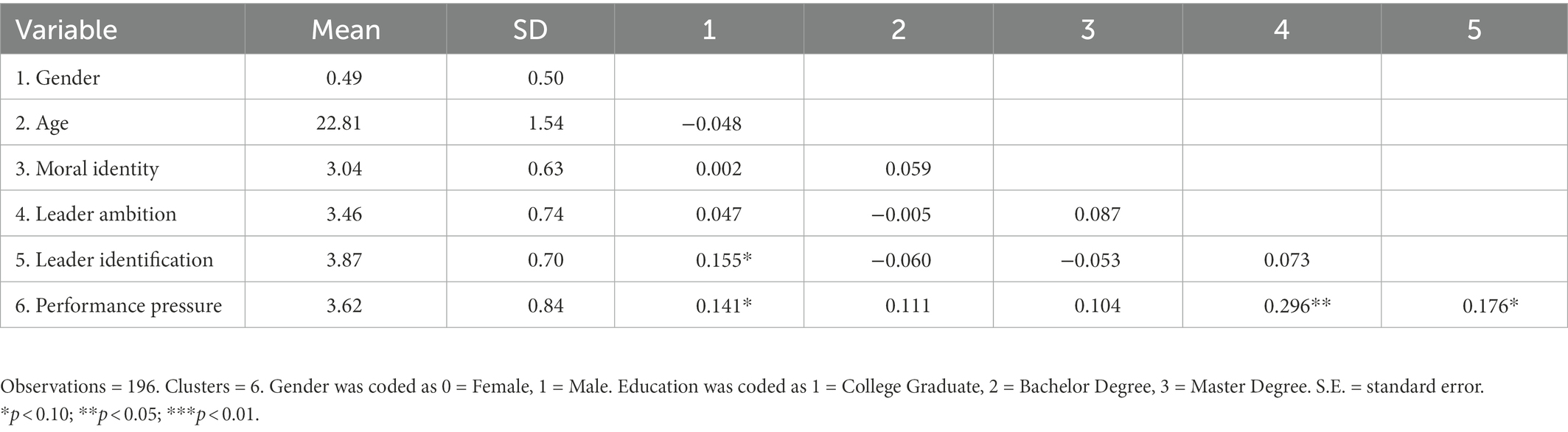

Descriptive statistics

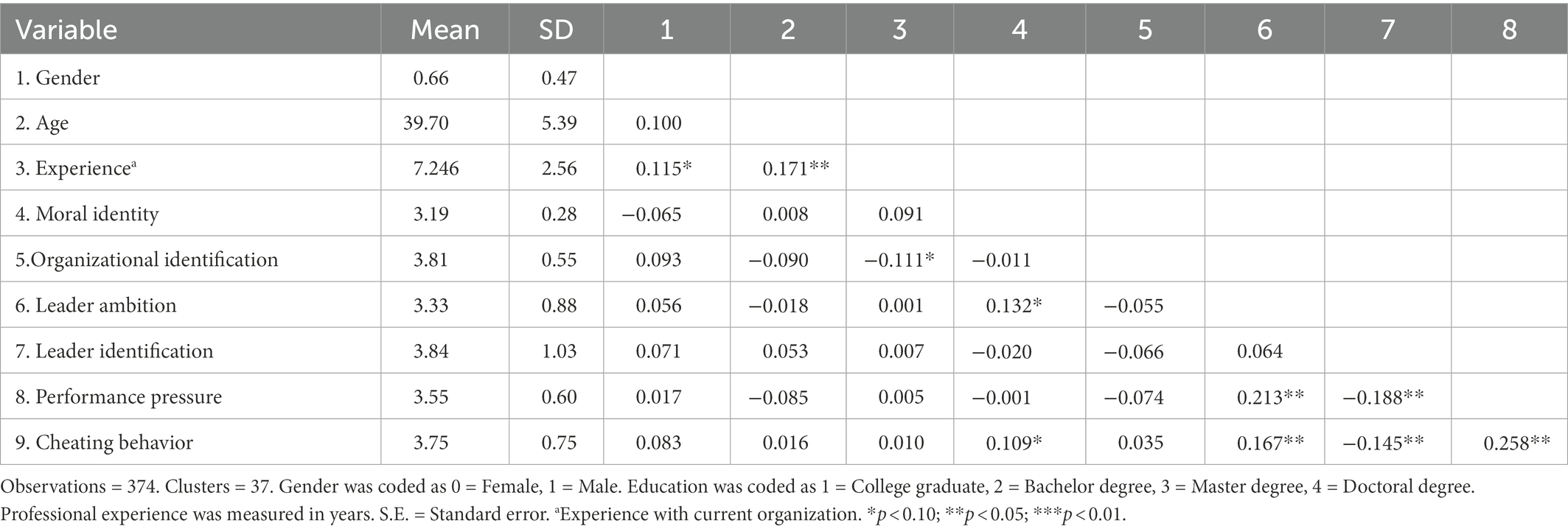

Mean, standard deviation, and correlations among the study variables are depicted in Study 1-Table 1.

Results

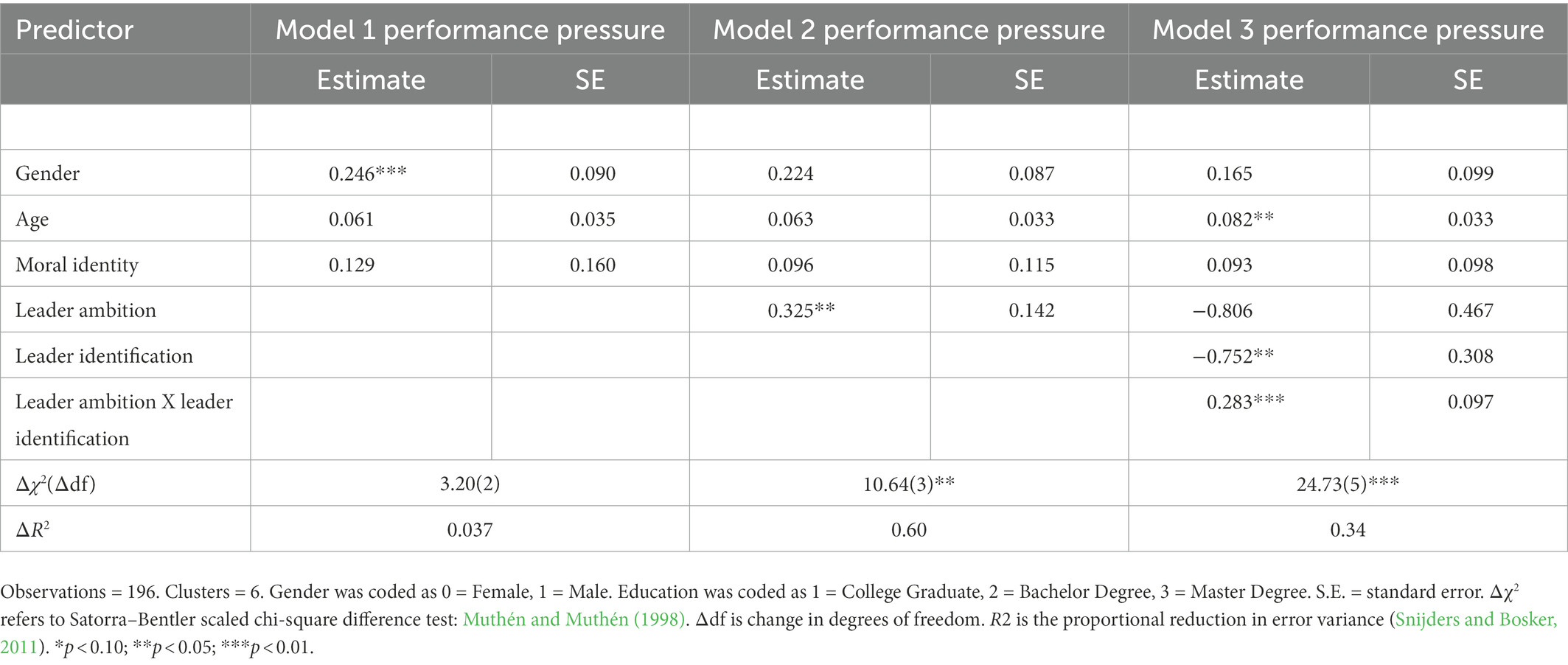

Due to the nested nature of the study sample, linear regression for this study could underestimate standard error. Therefore, on recommendations of researchers for nested data (Scherbaum and Ferreter, 2009), we used random coefficient modeling for a single level of analyzes with Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Although the technique eliminates chances of standard error underestimation and potential interdependence among study variables, the output produced with this technique cannot be used for model fit indicators regularly. Therefore, for chi-squared different testing, we performed the Satorra-Bentler difference test using the log-likelihood method with the scaling correction factor (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Main study variables, control variables, and interaction term also grand mean-centered before any analyzes of this study.

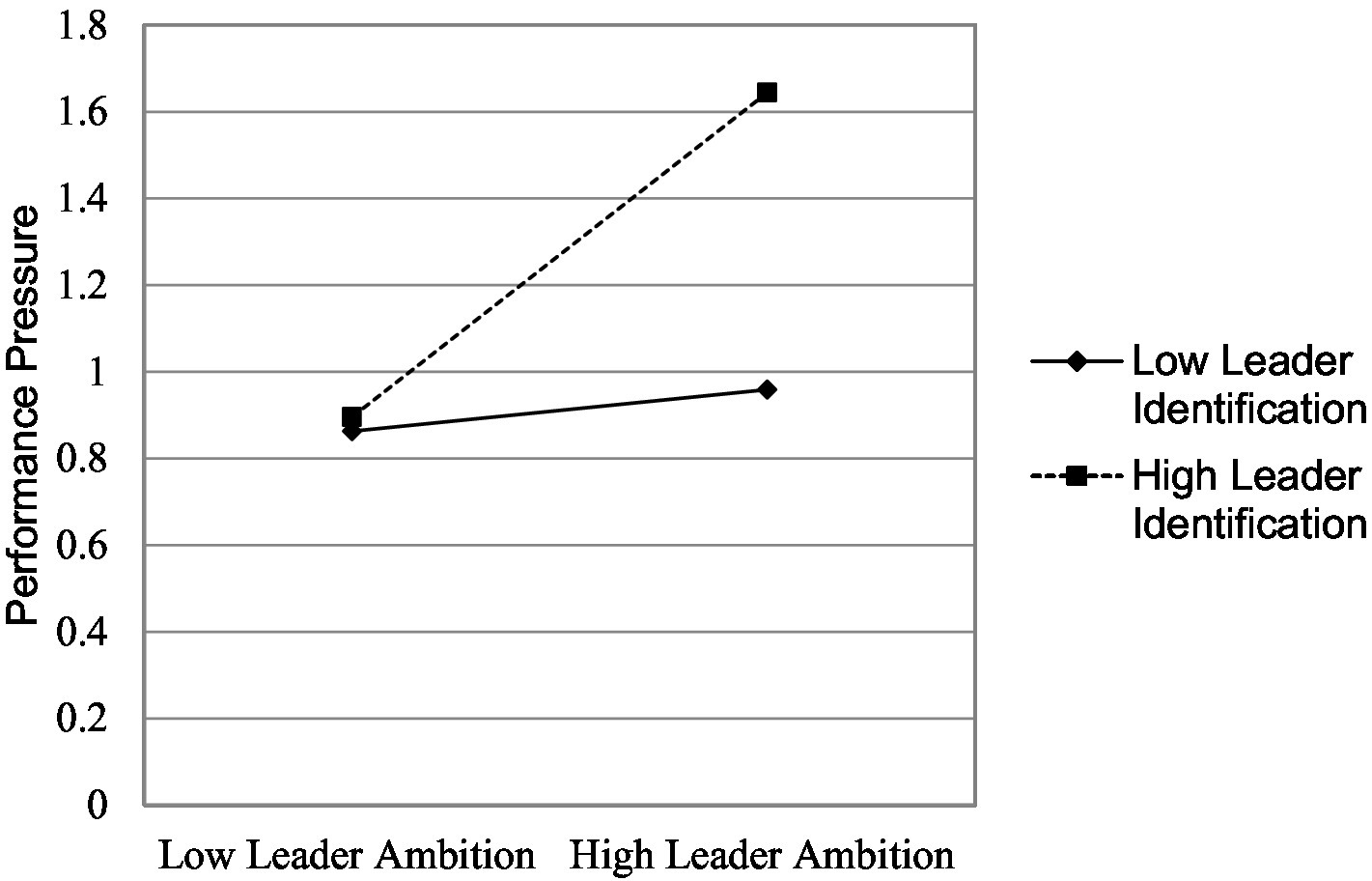

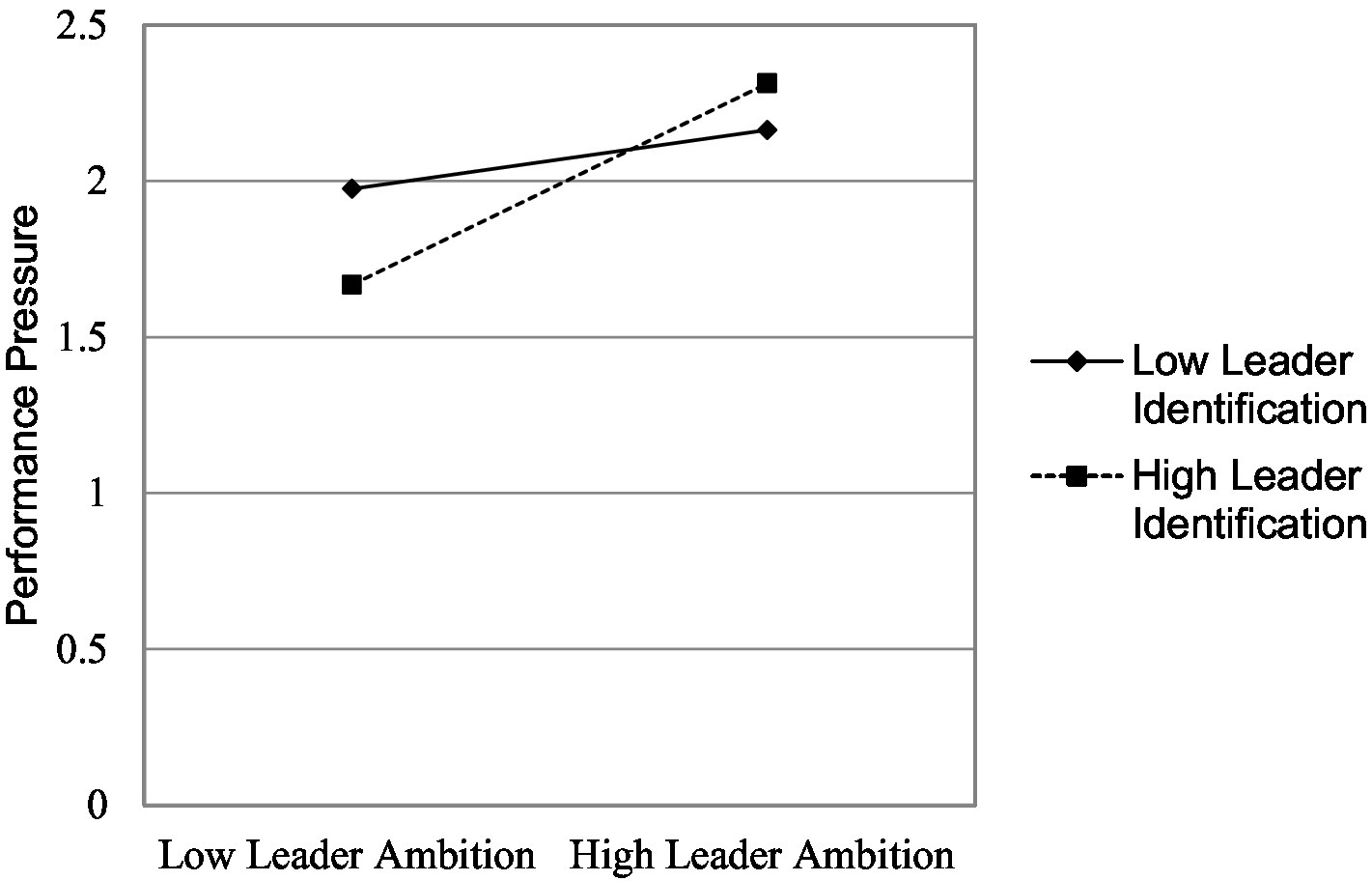

Random coefficient regression analyzes are depicted in Study 1-Table 2. For this study we were interested to know the effects leader ambition could have on performance pressure, therefore, our core hypothesis was about the relationship between leader ambition and performance pressure. Results in Study 1-Table 2 model 2 shows that leader ambition is a positive predictor of performance pressure (β = 0.325, p ≤ 0.05). The interaction term of leader ambition and leader identification in the Study 1-Table 2 model 3, also emerged as a positive predictor of performance (β = 0.283, p ≤ 0.001). Study 1-Figure 2 depicts interaction findings; the results of this interaction show that performance pressure is higher when both leader ambition and leader identification are high. High leader ambition is likely to produce a higher level of performance pressure when subordinates also had a high level of leader identification. The results of this study supported both hypotheses of this study.

Study 2

Sample and data collection

To increase the generalizability and validity of proposed relationships, we conducted a second study, using data collected from Islamic banking professionals. Since, in study 1, we could not collect data for employees’ cheating behavior, we only tested hypotheses 1 and 2. In study 2, we collected data for leader ambition, leader identification, performance pressure, and cheating behavior. Thus, we examined all the hypotheses, including mediated moderation in study 2.

The sample of study 2 included 374 responses from their respective 37 managers from an Islamic bank operating in Pakistan. The claim that Islamic banking has an ethical foundation is based on the Islamic principles of equity, cooperation, and social justice (Ismaeel and Blaim, 2012; Mansour et al., 2015). Therefore, Islamic banking operations and management are considered best suited for this study’s purpose and scope.

We discussed the purpose, scope, and relevance of the study with the management of the bank and obtained approval for data collection. For this study, we used two sources of data collected from managers and their respective subordinates by dividing the data collection process into three points in time. HR department sent a questionnaire to 758 subordinates and their respective 58 supervisors at time 1. The response was received from 621 subordinates at time 1, 590 subordinates at time 2, and 394 subordinates at time 3. After deleting records with missing values and mismatched data with managers’ responses, our final sample yielded a subordinates’ response of 374 and the managers’ response of 37 (49 and 65% respectively). Subordinates provided their response for demographic variables, organizational experience, moral identity, organizational identity, and leader identification at time 1; they also provided their response for performance pressure and cheating behavior at times 2 and 3. Managers provided their response for leader ambition at time 1 only. Thus, subordinates provided data for demographic variables, organizational experience, moral identity, organizational identity, leader identification, performance pressure, and cheating behavior, and managers provided their response for leader ambition. In this study’s final qualified sample, 66% were males and 34% were females; the average age of the subordinates was 39.70 years; an average of organizational experience was 7.246 years.

Measures

Leaders’ Ambition: We measured leaders’ ambition using five items ambition scale (Duckworth et al., 2007) adapted by (Rodriguez et al., 2013) as used in study 1 (α = 0.95). Performance Pressure: We used a 4-item scale to measure performance pressure (Mitchell et al., 2018) as used in study 1 (α = 0.93). Leader Identification: We measured leader identification with the same six items scale (Kark et al., 2003; Wang and Howell, 2012) as used in study 1 (α = 0.85).

Control Variables: Similar to study 1, we also controlled for subordinates’ gender, age, experience with current organization, and moral identity, which may affect cheating behavior (Kohlberg and Power, 1981; Aquino and Reed, 2002; Kish-Gephart et al., 2010). Research has shown that organizational identification influences organizations’ unethical behavior (Chen et al., 2016). Consequently, we controlled for organizational identification with six items five-point Likert type scale (Mael and Ashforth, 1992). Scale items range from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree. Sample scale items are “When someone criticizes my organization, it feels like a personal insult” and “I am very interested in what others think about my organization” (α = 0.83).

Data analysis

Results

Study 2-Table 3 reports descriptive statistics and zero-order correlation among the study variables.

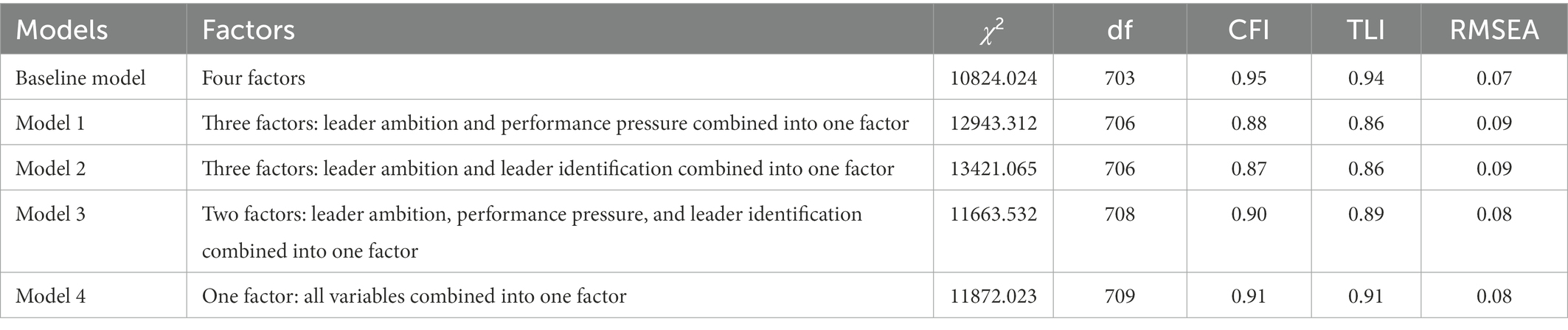

Confirmatory factor analyzes

In order to evaluate discriminant validity of study variables, we conducted a CFA using Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Item level indicators were modeled which provided a good fit to the data χ2 = 10824.024 (703), p < 0.01; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.07 as compared to all other alternative constrained models illustrated in Table 4. These CFA results demonstrated that the four-factor model had satisfactory discriminant validity.

Results

Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén, 2010) was used to test hypotheses in this study. We used random coefficient regression analyzes operated at a single level as used in study 1. Data collected from bankers was nested in nature; therefore, the use of OLS regression could underestimate standard error (Scherbaum and Ferreter, 2009). Additionally, due to the potential problem of interdependence among study variables, we used random coefficient modeling at a single level of analysis for all these study models. The output produced with random coefficient modeling cannot be used in a regular way for model fit indicators (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Therefore, we performed the Satorra-Bentler difference test using the log-likelihood method for null and alternate models with scaling correction factors. Same methods of analysis have already been used by researchers with data of similar characteristic (Adeel et al., 2022a,b). We also grand mean centered all the study variables, including interaction terms (Aiken et al., 1991; Hofmann and Gavin, 1998). Random coefficient analyzes results are depicted in Study 2-Table 5. Bootstrapping cannot be used for indirect effects with random coefficient analyzes (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). Therefore, for random coefficient mediated moderation, we followed the three-step procedure of mediated moderation (Baron and Kenny, 1986; Muller et al., 2005).

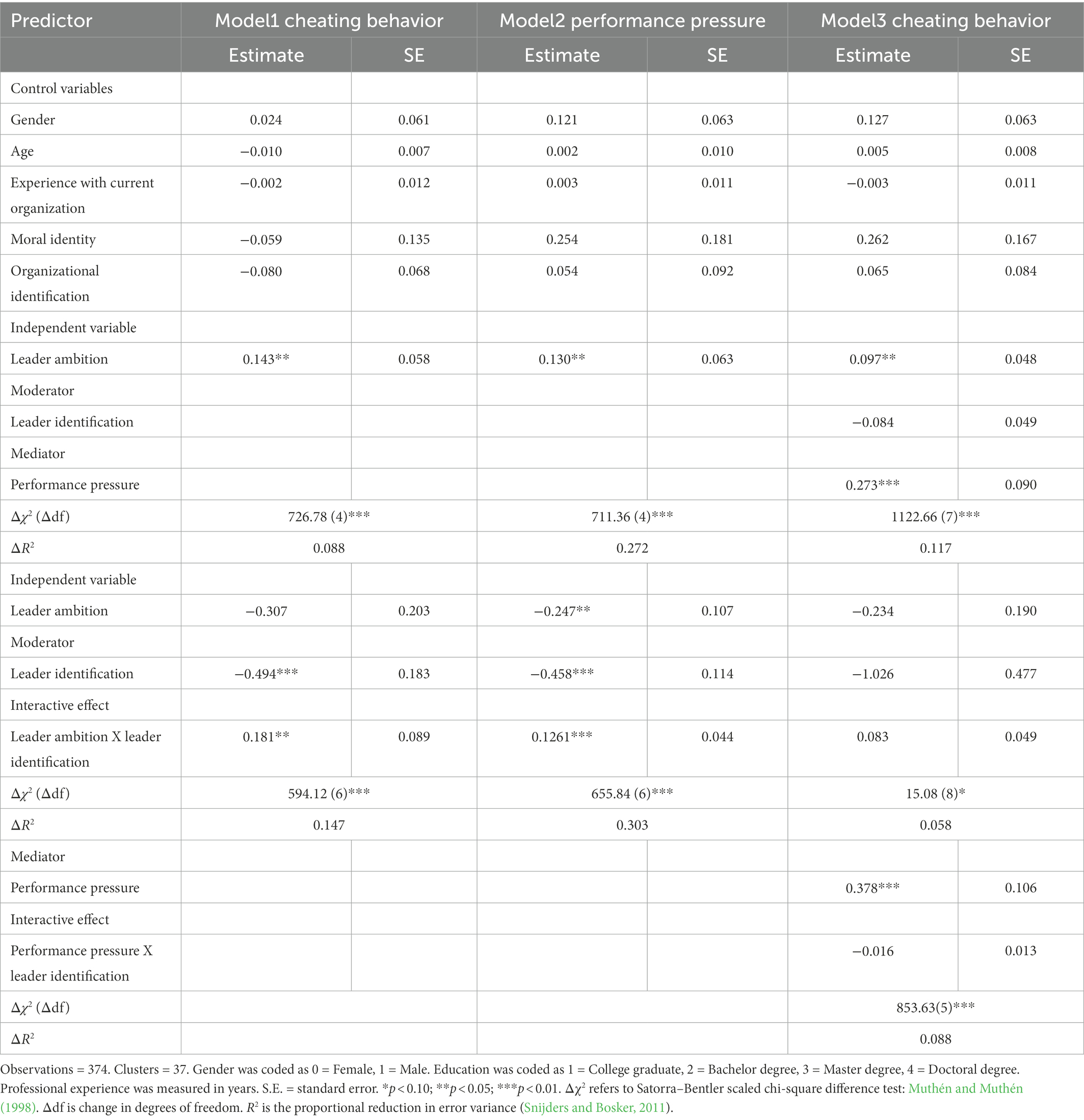

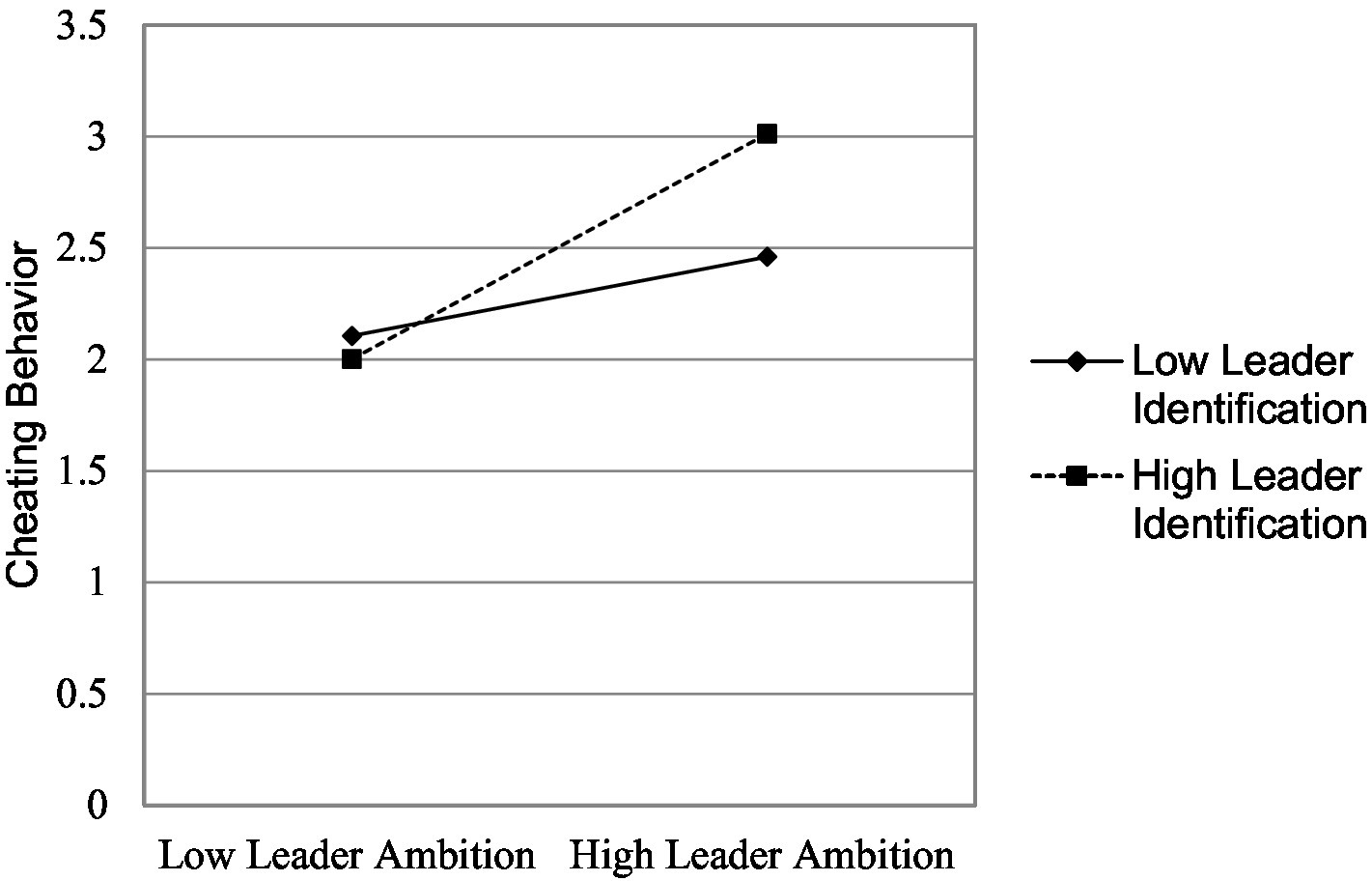

As in study 1, we also examined the direct effect of leaders’ ambition on performance pressure and the interaction of leaders’ ambition and leader identification on performance pressure. We used subordinates’ gender, age, experience with current organization, moral identity, and organizational identification as controls; leaders’ ambition as the independent variable; performance pressure as mediator; and leader identification as a moderator in this study. Study 2-Table 5 (model 1 and 2), leaders’ ambition is a positive predictor of cheating behavior (β = 0.143, p < 0.05, Δ R2 = 0.088) and performance pressure, respectively, (β = 0.130, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.272). As shown in Study 2-Table 5 (model 1), the interaction term of leaders’ ambition and leader identification also emerged as a positive predictor of cheating behavior (β = 0.181, p < 0.05, ΔR2 = 0.147). With these results, we fulfilled the first requirement of the mediated moderation model. The interaction results are depicted in Study 2-Figure 3. The results demonstrate that cheating behavior is higher when both leaders’ ambition and leader identification are high. Study 2-Table 5 (model 2), the interaction term of leaders’ ambition and leader identification also emerged as a positive predictor of performance pressure (β = 0.126, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.303); fulfilling the second requirement of the mediated moderation model. The interaction results are shown in study 2-Figure 4. The results show that performance pressure is higher when both leaders’ ambition and leader identification are high.

Finally, in study 2-Table 5 (model 3), the results revealed that performance pressure has a significant mediating effect on cheating behavior in presence of all control variables, leaders’ ambition, leader identification, the interaction of leaders’ ambition and leader identification, and interaction of performance pressure and leader identification (β = 0.378, p < 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.088), however, the coefficient of the interaction term of leaders’ ambition and leader identification became insignificant (β = 0.083, p ˃ 0.10, ΔR2 = 0.058); fulfilling the final requirement of the mediated moderation model. The results indicate that performance pressure fully mediates the interaction effect of leaders’ ambition and leader identification on cheating behavior of employees. With the results of this study, we provided support to all of the hypotheses of this research.

Discussion

We found that leaders’ ambition is more strongly related to subordinates’ performance pressure and subordinates’ cheating behavior when leader identification is high. These findings suggest that leaders themselves can be sources of performance pressure and cheating behavior of employees at organizations. Subordinates with high leader identification take more pressure and are likely to demonstrate more cheating when working with ambitious leaders. Indicating that a high level of loyalty to the leader is dangerous for the organizations. Thus, the results of this research have extended leaders’ ambition literature by demonstrating the role and importance of subordinates’ leader identification for subordinates’ performance pressure and subordinates’ cheating behavior.

Theoretical implications

This research offers some distinct contributions to the literature. This research’s primary contribution lies in answering the fundamental question that what leaders and organizations are unintentionally doing, may motivate employees for cheating. Researchers have long been emphasizing the need for organizations that motivate employees to behave unethically (Moore and Gino, 2013; Mitchell et al., 2018). We theorized that organizations’ cheating behavior occurs when leaders heighten their achievement of goals by energizing employees to use their full potential for the betterment of the organizations, which they do when they pressure their subordinates to raise performance. Prior research has explored the role of high performance pressure on employees’ cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018). This research line has shown that in order to overstate productivity, organizations unintentionally enhance employees’ self-interested motives and need for self-protection that elicits employees’ cheating behavior through enhanced performance pressure. We enhanced this research line, further unpacking the reasons when and how performance demands as fueled by leaders’ ambitions promotes the cheating behavior of employees. We argue that leaders’ high ambitions of achievements for their organizations enhance their demand from the subordinates for high performances- a subjective experience of the employees to raise their efforts for high performance linked with distal consequences promotes employee cheating behavior. Thus, leaders’ ambition becomes a threatening cause and elicits employee cheating behavior, which is internalized through the subjective experience of pressure to perform high.

We extend the literature on leadership by investigating how leaders’ ambitions are translated into performance pressure and cheating behavior of employees. The results of this research provide more understanding of the consequences of leaders’ ambitions. The presumed consequences of high ambitious leaders are beneficial for the organizations, they energize their followers (Steffens et al., 2018) for the achievement of goals (McClelland, 1975) and for the benefits of their organizations (Balda and Mora, 2011; Saleem et al., 2020). We add to this line of research by explaining the potential negative side of leaders’ ambitions. This addition to the previous research efforts is important because leaders focus on the employees for the achievement of goals in the work context. Additionally, this research also explained that subordinates with high leader identification are expected to take more pressure to perform, thereby enhancing their cheating intentions. This research highlighted the process that explains why and how leaders’ ambitions are translated into employees’ cheating behaviors.

We shift the focal point away from the analysis of leaders and followers separately, a much-needed shift (Shamir, 2007; Bastardoz and Van Vugt, 2019), previous research has rarely investigated leaders and followers in a single study (Day, 2014; Bastardoz and Van Vugt, 2019). The main reason remained; followers are considered the default in leadership research ignoring the fact that they are not just a monolithic group (Carsten et al., 2010) but individuals with different emotions, behaviors, abilities, aptitude, and motivation that are affected by leaders (Bastardoz and Van Vugt, 2019). Therefore, for a deeper understanding of leaders and followers, and the behavior of followers triggered by leaders, a shift of conventional investigation lens was needed. Our final contribution is concerned with the integration of ambition theory with social identity theory, in our point of view, provides a more comprehensive and integrative model to understand leaders’ deeds that are translated into followers’ behaviors, more specifically, the positive deeds of leaders that are promoting negative behaviors of followers.

Managerial implications

This study’s practical implication is that leaders’ positive desire in general and ambition, in particular, may not be necessarily associated with subordinates’ positive behaviors. Our results revealed that internalized with performance pressure, the leaders’ ambitions are associated with subordinates’ cheating behavior. The high ambitions of leaders are associated with high cheating behavior and high performance pressure for those subordinates who also had high identification with the leaders. The results help us understand what might be enhancing performance pressure and ultimately cheating behavior of subordinates, therefore, it is critically important for the organizations to not only have ambitious leaders but also subordinates of an ambitious leader with low leader identification so that the intentions of cheating could be minimized. Customized training programs for the development of organizational identification in employees may help prevent the elicitation of cheating behaviors by shifting the focus of the employees from identification with their leader to identification with their organization.

It is known that subordinates’ identification with their leader as a relational bias affect the oneness perceptions of subordinates with their leader (Ashforth et al., 2016) where meeting leaders’ expectations become the prime interest of the subordinates (Wang and Rode, 2010) ignoring the expectations of their organization (Chen et al., 2015; Chughtai, 2016; Nason et al., 2018). If a subordinate, who genuinely wants to enhance work performance for his/her organization, mistakenly attributes his/her identification with the leader as identification with his/her organizations, is likely to be stirred toward more pressure to perform and cheating. Employee development programs designed to develop and enhance ethics may also help reduce the cheating intentions of employees. Discussion forums at the organization’s web portal, operated by high officials, could be used to shift employees’ identification from their leaders to identification with their organization. These discussion forums could also be used for employees’ ethical development and for communicating proper performance measures as needed by their organization. These transparency measures would increase the organization’s direct communication to the employees, organization’s direct communication to the employees, leaving fewer chances for leaders to manipulate situations for high performance demands, ultimately promoting cheating behaviors.

Limitations and future research directions

Like any study, this research is also not free from limitations. Although we have strong theoretical reason to expect that leader ambition would precede performance pressure and/or cheating behavior and not vice versa, the research design of this research does not allow us to test the temporal order of the study variables, and the conditions under which cheating behavior would precede performance pressure and/or leader ambition. The theoretical reason we expect that leader ambition would precede performance pressure and/or cheating behavior and not vice versa is that leaders’ ambition literature predominantly shown that the ambitious leaders energize followers (Steffens et al., 2018) to use their full potential (Hobfoll, 2011) for the achievement of goals (McClelland, 1975).

Empirically, however, we could not tease apart the causality of the proposed relationships among the study variables. One possible reason for this limitation would be the age and the professional experiences, even though, the supervisors in our research had legitimate positions in organizations, they had an almost similar level of professional experience [7.24 years for the subordinates and 8.37 years for the supervisors (study 2)] and age (22.81 and 39.7 years for the subordinates for study 1 and study 2 respectively; 23.37 and 41.54 years for the supervisors for study 1 and study 2 respectively). A possible different interpretation of our results could be that when subordinates take pressure on their assigned tasks, they are energized for high ambitions. However, our findings at least provided some evidence that treating leader ambitions as an antecedent, rather than a consequence, of cheating behavior is consistent with theory as well as the sample characteristics we studied. Still, future research should seek to further explore the directionality issue, in a longitudinal experimental design.

Another limitation of this study lies in the context of this research. We collected data from the police officers in study 1 and from the Islamic banking professional in study 2, although both of these departments are expected to be ethical. However, we found positive results for performance pressure and cheating in an ambitious leader. However, it is still unclear whether the study results would generalize to disparate occupations, cultures, and at different organizational levels. Although the police department and banking profession are important employers worldwide, further research should focus on disparate occupations so that the results would be generalized. Thus, we recommend, future research should explore and operationalize the relationships among leaders’ ambitions, leader identification, performance pressure, and cheating behavior in industries other than banking and police departments where data collected from the employees working at different hierarchical levels.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The University of Chenab. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeel, A., Batool, S., and Ali, R. (2019a). Empowering leadership and team creativity: understanding the direct-indirect path. Business 19, 242–254. doi: 10.3846/btp.2018.24

Adeel, A., Batool, S., Daisy, K. M. H., and Khan, M. K. (2022a). LMX and creative idea validation: the role of helping and bullying. Asian. Acad. Manag. J.

Adeel, A., Kee, D. M. H., and Daghriri, Y. Q. (2022b). Conflict side of creativity: role of supervisory support and team affective tone in facilitating creative idea validation. Frontiers. Public Health 10:965278. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.965278

Adeel, A., Pengcheng, Z., Saleem, F., Ali, R., and Batool, S. (2019b). Conflicts and creative idea endorsement. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 30, 637–656. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-02-2019-0033

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., and Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Andersen, S. M., and Chen, S. (2002). The relational self: an interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychol. Rev. 109, 619–645. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.4.619

Aquino, K., and Reed, I. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 1423–1440. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423

Ashforth, B. E., and Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 20–39. doi: 10.2307/258189

Ashforth, B. E., Schinoff, B. S., and Rogers, K. M. (2016). “I identify with her,” “I identify with him”: unpacking the dynamics of personal identification in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 41, 28–60. doi: 10.5465/amr.2014.0033

Balda, J. B., and Mora, F. (2011). Adapting leadership theory and practice for the networked, millennial generation. J. Leadersh. Stud. 5, 13–24. doi: 10.1002/jls.20229

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bastardoz, N., and Van Vugt, M. (2019). The nature of followership: evolutionary analysis and review. Leadersh. Q. 30, 81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.09.004

Baumeister, R. F. (1984). Choking under pressure: self-consciousness and paradoxical effects of incentives on skillful performance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 610–620. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.610

Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Yielding to temptation: self-control failure, impulsive purchasing, and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 28, 670–676. doi: 10.1086/338209

Becker, G. S. (1993). Nobel lecture: the economic way of looking at behavior. J. Polit. Econ. 101, 385–409. doi: 10.1086/261880

Belle, N., and Cantarelli, P. (2017). What causes unethical behavior? A meta-analysis to set an agenda for public administration research. Public Adm. Rev. 77, 327–339. doi: 10.1111/puar.12714

Berscheid, E., and Reis, H. T. (1998). “Attraction and close relationships” in The Handbook of Social Psychology. eds. D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (New York: McGraw-Hill).

Brass, D. J., Butterfield, K. D., and Skaggs, B. C. (1998). Relationships and unethical behavior: a social network perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 14–31. doi: 10.2307/259097

Braun, S., and Hornuf, L. (2018). “Authentic leadership and followers” in Cheating Behaviour: A Laboratory Experiment from a Self-concept Maintenance Perspective Authentic Leadership and Followership (Berlin: Springer), 215–244.

Bretag, T., Harper, R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Rozenberg, P., et al. (2018). Contract cheating: a survey of Australian university students. Stud. High. Educ. 44, 1837–1856. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1462788

Campos, V. F., Valle, M. A., and Bueno, J. L. O. (2022). Cheating modulated by time pressure in the matrix task. Trends Psychol., 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s43076-022-00148-9

Caro, R. (2002). The Old Bull-Arthur Herman, the Years of Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate. Bristol Connecticut: National Review, 54, pp. 46–47.

Carsten, M. K., Uhl-Bien, M., West, B. J., Patera, J. L., and McGregor, R. (2010). Exploring social constructions of followership: a qualitative study. Leadersh. Q. 21, 543–562. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.015

Chen, M., and Chen, C. C. (2021). The moral dark side of performance pressure: how and when it affects unethical pro-organizational behavior. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag., 1–31. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2021.1991434

Chen, M., Chen, C. C., and Sheldon, O. J. (2016). Relaxing moral reasoning to win: how organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 1082–1096. doi: 10.1037/apl0000111

Chen, Z., Zhu, J., and Zhou, M. (2015). How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self-identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 511–521. doi: 10.1037/a0038036

Chughtai, A. A. (2016). Servant leadership and follower outcomes: mediating effects of organizational identification and psychological safety. J. Psychol. 150, 866–880. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2016.1170657

Cianci, A. M., Hannah, S. T., Roberts, R. P., and Tsakumis, G. T. (2014). The effects of authentic leadership on followers' ethical decision-making in the face of temptation: an experimental study. Leadersh. Q. 25, 581–594. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.12.001

Cohn, A., Fehr, E., and Maréchal, M. A. (2014). Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature 516, 86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature13977

Day, D. V. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations: Oxford Library of Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deng, M., Li, X., Wang, F., and Shi, W. (2022). Affirming who I am: effects of intrinsic and extrinsic affirmations on responses to interpersonal offenses in the workplace. Int. J. Confl. 33, 829–859. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-08-2021-0123

DeRue, D. S., Ashford, S. J., and Cotton, N. C. (2009). “Assuming the mantle: Unpacking the process by which individuals internalize a leader identity” in Exploring Positive Identities and Organizations: Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation (Milton Park: Routledge), 213–232.

Desrochers, S., and Dahir, V. (2000). Ambition as a motivational basis of organizational and professional commitment: preliminary analysis of a proposed career advancement ambition scale. Percept. Mot. Skills 91, 563–570. doi: 10.2466/pms.2000.91.2.563

DeZoort, T., Harrison, P., and Taylor, M. (2006). Accountability and auditors’ materiality judgments: the effects of differential pressure strength on conservatism, variability, and effort. Acc. Organ. Soc. 31, 373–390. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2005.09.001

Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 41, 417–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221

Dilchert, S. (2007). Peaks and valleys: predicting interests in leadership and managerial positions from personality profiles. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 15, 317–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2007.00391.x

Djawadi, B. M., and Fahr, R. (2015). “… and they are really lying”: clean evidence on the pervasiveness of cheating in professional contexts from a field experiment. J. Econ. Psychol. 48, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2015.03.002

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., and Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 1087–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Egan, M.. (2016). 5,300 Wells Fargo Employees Fired Over 2 Million Phony Accounts. Available at: https://money.cnn.com/2016/09/08/investing/wells-fargo-created-phony-accounts-bank-fees/index.html (Accessed April 15, 2017).

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., and Walter, J. (2015). Deeds that help and words that hurt: helping and gossip as moderators of the relationship between leader–member exchange and advice network centrality. Pers. Psychol. 68, 185–214. doi: 10.1111/peps.12075

GRTB–Global Retail Theft Barometer. (2016). Global Retail Theft Barometer 2014–2015. Available at: https://www.GlobalRetailTheftBarometer.com (Accessed September 10, 2017).

Gundry, L. K., and Welsch, H. P. (2001). The ambitious entrepreneur: high growth strategies of women-owned enterprises. J. Bus. Ventur. 16, 453–470. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00059-2

Gutnick, D., Walter, F., Nijstad, B. A., and De Dreu, C. K. (2012). Creative performance under pressure: an integrative conceptual framework. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2, 189–207. doi: 10.1177/2041386612447626

Hansson, R. O., Hogan, R., Johnson, J. A., and Schroeder, D. (1983). Disentangling type a behavior: the roles of ambition, insensitivity, and anxiety. J. Res. Pers. 17, 186–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(83)90030-2

Helson, R., and Srivastava, S. (2002). Creative and wise people: similarities, differences, and how they develop. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 1430–1440. doi: 10.1177/014616702236874

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 52, 1280–1300. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.12.1280

Hilbig, B. E., and Zettler, I. (2015). When the cat’s away, some mice will play: a basic trait account of dishonest behavior. J. Res. Pers. 57, 72–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.04.003

Hillebrandt, A., and Barclay, L. J. (2022). How COVID-19 can promote workplace cheating behavior via employee anxiety and self-interest–and how prosocial messages may overcome this effect. J. Organ. Behav. 43, 858–877. doi: 10.1002/job.2612

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hofmann, D. A., and Gavin, M. B. (1998). Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: implications for research in organizations. J. Manag. 24, 623–641. doi: 10.1177/014920639802400504

Hogan, J., Barrett, P., and Hogan, R. (2007). Personality measurement, faking, and employment selection. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1270–1285. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1270

Hsiao, C.-H., and Yang, C. (2011). The impact of professional unethical beliefs on cheating intention. Ethics Behav. 21, 301–316. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2011.585597

Ismaeel, M., and Blaim, K. (2012). Toward applied Islamic business ethics: responsible halal business. J. Manag. Dev. 31, 1090–1100. doi: 10.1108/02621711211281889

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., and Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). Personality and leadership: a qualitative and quantitative review. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 765–780. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

Judge, T. A., and Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2012). On the value of aiming high: the causes and consequences of ambition. J. Appl. Psychol. 97, 758–775. doi: 10.1037/a0028084

Kamran, K., Azam, A., and Atif, M. M. (2022). Supervisor bottom-line mentality, performance pressure, and workplace cheating: moderating role of negative reciprocity. Front. Psychol. 13:801283. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.801283

Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., and Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: a personality–motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 837–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.837

Kark, R., Shamir, B., and Chen, G. (2003). The two faces of transformational leadership: empowerment and dependency. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 246–255. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.246

Kiersch, C. E., and Byrne, Z. S. (2015). Is being authentic being fair? Multilevel examination of authentic leadership, justice, and employee outcomes. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 22, 292–303. doi: 10.1177/1548051815570035

Kim, D. H., and Schneider, B. (2005). Social capital in action: alignment of parental support in adolescents' transition to postsecondary education. Soc. Forces 84, 1181–1206. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0012

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., and Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 95, 1–31. doi: 10.1037/a0017103

Kohlberg, L., and Power, C. (1981). Moral development, religious thinking, and the question of a seventh stage. Zygon 16, 203–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9744.1981.tb00417.x

Krasikova, D. V., Green, S. G., and LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership: a theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. J. Manag. 39, 1308–1338. doi: 10.1177/0149206312471388

Leroy, H., Palanski, M. E., and Simons, T. (2012). Authentic leadership and behavioral integrity as drivers of follower commitment and performance. J. Bus. Ethics 107, 255–264. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1036-1

Liu, L., Fan, Q., Liu, R., and Long, J. (2022). How leader bottom-line mentality relates to employee innovation: a cross-layer model mediated by psychological contract breach. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 43, 580–595. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-04-2021-0156

Locke, E. A., and Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57, 705–717. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

Mael, F., and Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 13, 103–123. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130202

Mael, F. A., and Tetrick, L. E. (1992). Identifying organizational identification. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 52, 813–824. doi: 10.1177/0013164492052004002

Malesky, A., Grist, C., Poovey, K., and Dennis, N. (2022). The effects of peer influence, honor codes, and personality traits on cheating behavior in a university setting. Ethics Behav. 32, 12–21. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2020.1869006

Mansour, W., Ben Jedidia, K., and Majdoub, J. (2015). How ethical is Islamic banking in the light of the objectives of Islamic law? J. Relig. Ethics 43, 51–77. doi: 10.1111/jore.12086

McCabe, D. (2016). “Cheating and honor: lessons from a long-term research project” in Handbook of Academic Integrity (Berlin: Springer), 187–198.

Meyer, J. W. (1977). The effects of education as an institution. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 55–77. doi: 10.1086/226506

Mitchell, M. S., Baer, M. D., Ambrose, M. L., Folger, R., and Palmer, N. F. (2018). Cheating under pressure: a self-protection model of workplace cheating behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 103, 54–73. doi: 10.1037/apl0000254

Moore, C., and Gino, F. (2013). Ethically adrift: how others pull our moral compass from true north, and how we can fix it. Res. Organ. Behav. 33, 53–77. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2013.08.001

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., and Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 89, 852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers: User’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nagel, J. A., Patel, K. R., Rothstein, E. G., and Watts, L. L. (2020). Unintended consequences of performance incentives: impacts of framing and structure on performance and cheating. Ethics Behav. 31, 1–18.

Nagin, D. S., and Pogarsky, G. (2003). An experimental investigation of deterrence: cheating, self-serving bias, and impulsivity. Criminology 41, 167–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb00985.x

Nason, R. S., Bacq, S., and Gras, D. (2018). A behavioral theory of social performance: social identity and stakeholder expectations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 43, 259–283. doi: 10.5465/amr.2015.0081

Nickerson, C., Schwarz, N., and Diener, E. (2007). Financial aspirations, financial success, and overall life satisfaction: who? And how? J. Happiness Stud. 8, 467–515. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9026-1

Paterson, T. A., and Huang, L. (2018). Am I expected to be ethical? A role-definition perspective of ethical leadership and unethical behavior. J. Manag. 45, 2837–2860. doi: 10.1177/0149206318771166

Pettigrove, G. (2007). Ambitions. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 10, 53–68. doi: 10.1007/s10677-006-9044-4

Pratt, M. (1998). “To be or not to be: central questions in organizational identification” in Identity in Organizations: Developing theory through Conversations. eds. D. Whetten and P. Godfrey (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 171–207.

Rhodes, R. E., Courneya, K. S., and Jones, L. W. (2005). The theory of planned behavior and lower-order personality traits: interaction effects in the exercise domain. Personal. Individ. Differ. 38, 251–265. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.005

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., and Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: the comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2, 313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

Rodriguez, K. M., Castillo, L. G., and Gandara, L. (2013). The influence of marianismo, ganas, and academic motivation on Latina adolescents’ academic achievement intentions. J. Latin. Psychol. 1, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/lat0000008

Romosiou, V., Brouzos, A., and Vassilopoulos, S. P. (2018). An integrative group intervention for the enhancement of emotional intelligence, empathy, resilience and stress management among police officers. Police Pract. Res. 20, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2018.1537847

Saleem, F., Zhang, Y. Z., Gopinath, C., and Adeel, A. (2020). Impact of servant leadership on performance: the mediating role of affective and cognitive trust. SAGE Open 10:215824401990056. doi: 10.1177/2158244019900562

Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W., Lord, R. G., Treviño, L. K., et al. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organization levels. Acad. Manag. J. 55, 1053–1078. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0064

Scherbaum, C. A., and Ferreter, J. M. (2009). Estimating statistical power and required sample sizes for organizational research using multilevel modeling. Organ. Res. Methods 12, 347–367. doi: 10.1177/1094428107308906

Schlesinger, J. A. (1966). Ambition and Politics: Political Careers in the United States. Chicago: Rand McNally and Co.

Schweitzer, M. E., Ordóñez, L., and Douma, B. (2004). Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 47, 422–432. doi: 10.2307/20159591

Schyns, B., and Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 24, 138–158. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001

Sewell, W. H., Hauser, R. M., Springer, K. W., and Hauser, T. S. (2003). As we age: a review of the Wisconsin longitudinal study, 1957–2001. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 20, 3–111. doi: 10.1016/S0276-5624(03)20001-9

Shalley, C. E., and Perry-Smith, J. E. (2001). Effects of social-psychological factors on creative performance: the role of informational and controlling expected evaluation and modeling experience. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 84, 1–22. doi: 10.1006/obhd.2000.2918

Shamir, B. (2007). “From passive recipients to active co-producers: Followers' roles in the leadership process” in Follower-centered Perspectives on Leadership: A Tribute to the Memory of James R. Meindl (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.), 9–39.

Sheng, Z., and Fan, B. (2022). The double-edged sword effect of performance pressure on public employees: the mediation role of mission valence. Front. Psychol. 13:992071. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992071

Shu, L. L., Gino, F., and Bazerman, M. H. (2011). Dishonest deed, clear conscience: when cheating leads to moral disengagement and motivated forgetting. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 330–349. doi: 10.1177/0146167211398138

Sieberer, U., and Müller, W. C. (2017). Aiming higher: the consequences of progressive ambition among MPs in European parliaments. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 9, 27–50. doi: 10.1017/S1755773915000260

Sitkin, S. B., See, K. E., Miller, C. C., Lawless, M. W., and Carton, A. M. (2011). The paradox of stretch goals: organizations in pursuit of the seemingly impossible. Acad. Manag. Rev. 36, 544–566. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2011.61031811

Sluss, D. M., and Ashforth, B. E. (2007). Relational identity and identification: defining ourselves through work relationships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 32, 9–32. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.23463672

Snijders, T. A., and Bosker, R. J. (2011). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. sage.

Spoelma, T. M. (2021). Counteracting the effects of performance pressure on cheating: a self-affirmation approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 107, 1804–1823. doi: 10.1037/apl0000986

Steffens, N. K., Fonseca, M. A., Ryan, M. K., Rink, F. A., Stoker, J. I., and Pieterse, A. N. (2018). How feedback about leadership potential impacts ambition, organizational commitment, and performance. Leadersh. Q. 29, 637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.06.001

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: a person-situation interactionist model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 11, 601–617. doi: 10.2307/258313

Treviño, L. K., Den Nieuwenboer, N. A., and Kish-Gephart, J. J. (2014). (un) ethical behavior in organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65, 635–660. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143745

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., and Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: a review. J. Manag. 32, 951–990. doi: 10.1177/0149206306294258

van Gils, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., van Knippenberg, D., van Dijke, M., and De Cremer, D. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower organizational deviance: the moderating role of follower moral attentiveness. Leadersh. Q. 26, 190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.08.005

Van Knippenberg, D., Van Knippenberg, B., De Cremer, D., and Hogg, M. A. (2004). Leadership, self, and identity: a review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 15, 825–856. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.002

Wang, X.-H. F., and Howell, J. M. (2012). A multilevel study of transformational leadership, identification, and follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 23, 775–790. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.02.001

Wang, P., and Rode, J. C. (2010). Transformational leadership and follower creativity: the moderating effects of identification with leader and organizational climate. Hum. Relat. 63, 1105–1128. doi: 10.1177/0018726709354132

Welsh, D. T., and Ordóñez, L. D. (2014). The dark side of consecutive high performance goals: linking goal setting, depletion, and unethical behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 123, 79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.07.006

Williamson, O. E. (1984). The economics of governance: framework and implications. Z. Gesamte Staatswiss. 1, 195–223.

Winsborough, D. L., and Sambath, V. (2013). Not like us: an investigation into the personalities of New Zealand CEOs. Consult. Psychol. J. 65, 87–107. doi: 10.1037/a0033128

Zempi, I. (2018). ‘Looking back, i wouldn’t join up again’: the lived experiences of police officers as victims of bias and prejudice perpetrated by fellow staff within an English police force. Police Pract. Res. 21, 1–16.

Zhang, W., Jex, S. M., Peng, Y., and Wang, D. (2017). Exploring the effects of job autonomy on engagement and creativity: the moderating role of performance pressure and learning goal orientation. J. Bus. Psychol. 32, 235–251. doi: 10.1007/s10869-016-9453-x

Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Xie, J., and Yang, X. (2021). Coping with supervisor bottom-line mentality: the mediating role of job insecurity and the moderating role of supervisory power. Curr. Psychol., 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02336-9

Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., and Chen, S. (2022). The relationship between supervisor bottom-line mentality and subordinate work performance: linear or curvilinear effects? Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 15, 725–735. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S351206

Keywords: leaders’ ambitions, leader identification, performance pressure, cheating behavior, ambition theory, social identity theory

Citation: Adeel A, Kee DMH, Mubashir AS, Samad S and Daghriri YQ (2023) Leaders’ ambition and followers’ cheating behavior: The role of performance pressure and leader identification. Front. Psychol. 14:982328. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.982328

Edited by:

Ishfaq Ahmed, Hailey College of Commerce, PakistanReviewed by:

Xingshan Zheng, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaRizwan Shabbir, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan

Copyright © 2023 Adeel, Kee, Mubashir, Samad and Daghriri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmad Adeel,  YWRlZWxsZWFkc0B5YWhvby5jb20=

YWRlZWxsZWFkc0B5YWhvby5jb20=

Ahmad Adeel

Ahmad Adeel Daisy Mui Hung Kee

Daisy Mui Hung Kee Anila Sadaf Mubashir

Anila Sadaf Mubashir Sarminah Samad

Sarminah Samad Yahya Qasim Daghriri5

Yahya Qasim Daghriri5