- 1Center for the Study of Language and Cognition, School of Philosophy, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2Department of Automation, School of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Zhejiang SCI-TECH University, Hangzhou, China

Introduction

The study of consciousness is becoming one of several significant challenges at the frontiers of science, in contrast to its previously being off-limits. With the application of binocular rivalry, split brain, blindsight, and other paradigms by passionate pioneers in the last century (Seth, 2018), empirical theories of consciousness have emerged in neuroscience. Currently, the situation has reached a critical point of both hope and challenge in that a large number of theories of consciousness (ToCs), each with specific empirical support, have claimed their respective plausibilities, and their proposed conjectures have led to diverging predictions (Del Pin et al., 2021; Signorelli et al., 2021; Seth and Bayne, 2022; Yaron et al., 2022). Various theories have been discussed, and it appears that this issue is becoming more prevalent. Currently, the lack of collaboration between different groups and fields hinders the advancement of theories of consciousness. However, a fundamental theory which is not limited by the boundaries of individual theories is expected to emerge in the future (Koch, 2018).

In this process, four major kinds of ToCs have garnered the most attention (Seth and Bayne, 2022): Integrated Information Theory (IIT) (Tononi, 2008; Oizumi et al., 2014; Tononi et al., 2016), Global Neural Workspace Theory (GNWT) (Dehaene, 2014; Mashour et al., 2020), Higher-Order Theory (HOT) (Lau and Rosenthal, 2011; Brown et al., 2019), and Recurrent Processing Theory (RPT) (Lamme, 2018) and Predictive Processing Theory (PP) (Seth and Hohwy, 2021).

Briefly, IIT identifies any conscious experience with the maximally irreducible cause-effect structure of the system in the corresponding state; GNWT proposes that the global workspace, triggered by widespread neural ignition and the sharing of information across several cognitive modules, is the key to conscious access; HOT is based on the higher-order structure of conscious experience in which “I” am aware of “something” (the representation of “something” is first-order). At the same time, RPT and PP emphasize the importance of top-down processing in conscious mental activity.

Rather than attributing consciousness to neural activities, a fifth approach has identified consciousness with underlying physical processes across multiple spatiotemporal scales. As a typical and noted paradigm, Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR, cf. Hameroff and Penrose, 2014) theory claims that mental aspects like understanding, free will, or insight cannot be Turing machine computable based on Gödel's incompleteness theorems (Penrose, 1999). It associates consciousness with quantum mechanical processes. The Field Theories of Consciousness, which compare uncertain particle-like and wave-like phenomena as the “neuron–wave duality” (John, 2001), propose that the widespread electromagnetic (EM) fields in brains could be the physical correlates of consciousness (Hunt and Jones, 2023).

Their rivalries are likely to yield a winner through empirical tests (or remove inappropriate theories from the competitive stage to the extent possible) and eventually enable contemporary theories to move toward falsifiable unification (Ellia et al., 2021). Since the preparations begun in 2019, there has been an initial adversarial collaboration between IIT and GNWT (Reardon, 2019; Melloni et al., 2021), a project aimed at falsifying various ToCs and breaking down the barriers between them. With the implementation of Chalmers winning the “25-year wager” with Koch on unraveling the mechanism of consciousness at the meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness (ASSC) in 2023, the preliminary result of the adversarial collaboration has been published: neither of them matches their tests perfectly (Lenharo, 2023).

Block (1995) advocated an early distinction between P-consciousness, which focuses on the experiential properties of consciousness (qualia), and A-consciousness, which focuses on the cognitive functions of consciousness (e.g., linguistic activities). Regarding these two aspects of consciousness, GNWT and HOT generally refer to the so-called A-consciousness, whereas IIT and RPT might refer to P-consciousness. This seems to explain why IIT would maintain that the maximum integrated information should be generated in the posterior cortex, whereas the prefrontal cortex, which GNWT emphasizes, would not be necessary for IIT (cf. Koch et al., 2016; Boly et al., 2017; Odegaard et al., 2017). As Doerig et al. (2021a,b) discussed in the hard criteria for testing ToCs, some ToCs associate consciousness singularly with their preferred properties and mechanisms, which are likely to be necessary but insufficient. Similarly, Lamme (2018) comparison of her RPT with other ToCs led to the conclusion that “missing ingredients” exist in all of these necessary theories.

The trend of unifying the theories of consciousness

In the Chinese context, the classic metaphor of “blind men feeling the elephant” is often used to describe how people each grasp only a particular facet of a thing and therefore perceive the same thing differently because of the discrepancies in the facets to which they have been exposed. In a practical investigation, however, following the method the blind men do may not be such a bad start, as it suggests that we have been exposed to at least parts of the fact and that by correlating this knowledge, we will come to a complete understanding.

The recognized trend toward unifying ToCs has become more widely adopted, such as Wiese (2020) advocating a “minimal unifying model” (MUM) that would be compatible with the major theories. In an attempt to integrate multiple ToCs, Safron (2020) combined IIT, GNWT, and PP to construct a comprehensive theory. This was a remarkable effort, and it would be more explanatory if it incorporated more theoretical and experimental evidence, and could further respond to the conflicts between the remaining theories. As for HOT, Brown et al. (2019) argued that realizing a global workspace requires higher-order metacognition. The Attention Schema Theory (AST) (Graziano, 2019a,b), another current theory of consciousness, has also attracted much attention; Graziano et al. (2020) previously attempted to integrate their AST with GNWT, HOT, and other theories into a standard model of consciousness. In their response, Panagiotaropoulos et al. (2020) agreed with Graziano et al., at least on the orthogonal dimensions of the model of consciousness.

Nevertheless, some cruxes must be considered when comparing and contrasting the various theories. First, we must correctly touch the “elephant” and not something else; otherwise, for example, the integration of a model of finger movements (obviously not consciousness) into a model of consciousness would be troublesome; second, we also need to consider whether the methods or strategies used are appropriate. Regarding ToCs, for the first question, we need to cautiously confirm the diverse global states of consciousness (Bayne et al., 2016; McKilliama, 2020). A transformation in the global state of consciousness would result in a marked shift in the structure of the entire experience, as if going from one inner world to a very different one, rather than a simple change in the intensity or content of the experience. As for the second issue, Lau (2022), in his new book, analyzes in detail the ways in which current experimental methods can lead to biased interpretations of results. The rise of “no-report paradigms” (Tsuchiya et al., 2015), even “no-cognition paradigm” (Block, 2019), recently manifested a practical step forward in this regard.

Being careful of both concerns above, we might effectively have a series of necessary elements if to suppose as A, B, and C… for each indicates a model and corresponding mechanism, such as A referring to IIT. Based on the present approaches to unification, the fundamental theory would be an integration of these elements, i.e.,

the fundamental theory = A and B and C and …

Ideally, this result would be a necessary and sufficient condition for consciousness, also referred to as “minimally sufficient” (Fink, 2016). Is this always true? Is it possible that by integrating more and more candidate theories, our model could become more and more accurate? It is also important to note that such attempts at unification often overlook the fifth physical approach.

The architecture of a layered mind for consciousness

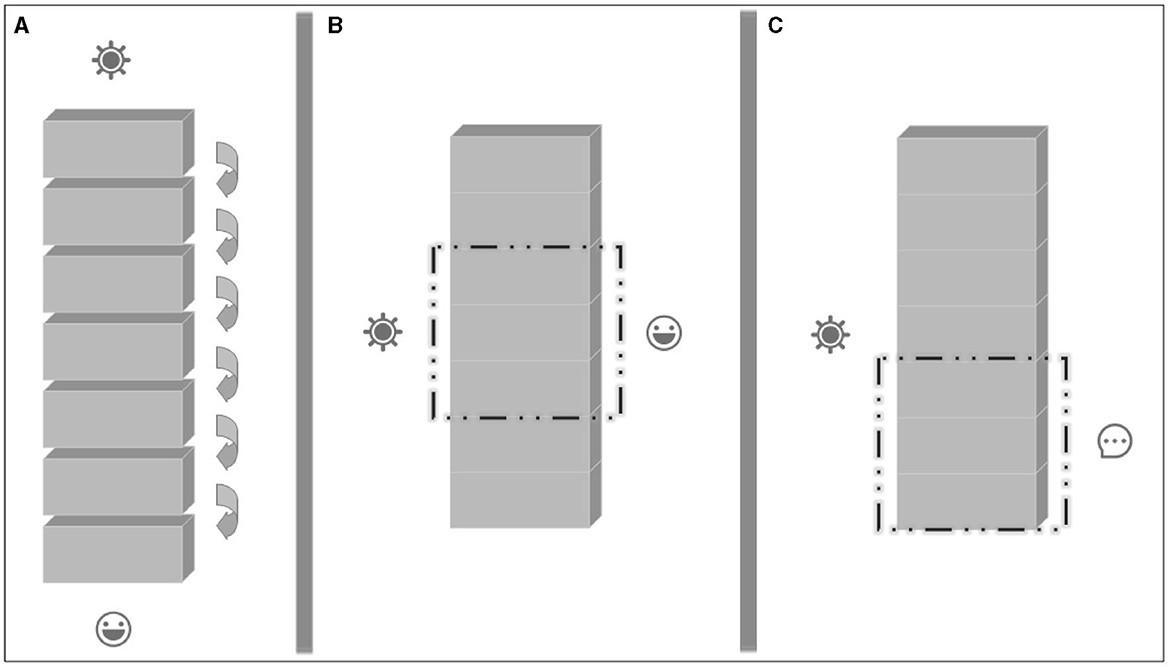

Gazzaniga (2018), “the father of cognitive neuroscience,” suggested his unique view of how consciousness arises based on many instances of abnormal brains he had been exposed to during ward rounds and split-brain research. For machines, confronting a breakdown is a better way for engineers to access and understand how they work. Similarly, neurological diseases indirectly provide an excellent window into the mechanisms of the mind, which Gazzaniga used to explore consciousness in the brain. For his strategy, Gazzaniga considered diverse global states and appropriate methods. He then argued that consciousness is the overall manifestation of the coordination of the diverse basic instincts of the mind, like a symphony without a conductor; in such a distributed system, individuals operate relatively independently, and different combinations of them can exhibit different patterns of performance (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The architecture of layered mind for consciousness. (A): In the architecture of traditional information processing, the stimulus signals are processed sequentially in modules, of which each specific form of information is only the product of a specific processing step, and would finally constitute experience in the so-called imaginary “module of consciousness”; (B): However, in the architecture of layered mind, signals are processed simultaneously in various layers, each of which is a candidate for a temporary “zone of consciousness”; (C): The arbitrary bonds of different layers bring specific types of experiences with different structures and attributes, such as the intervention of higher cognitive functional layers to bring the experience of the conceptual component.

Unlike other theories, this view does not specify whether cortical activity is sufficient or necessary for consciousness. Gazzaniga found that our brains were resilient. A computer with many severely damaged components would be rendered wholly paralyzed, but the damaged brains in the wards had still been functioning well in a way. There is no palace in the cortex and no part that acts like the core of a computer. Not only are the frontal cognitive modules and the posterior higher sensory cortex candidates for consciousness, but the entire cortex is also an evolutionary expansion of earlier forms of consciousness. In addition to Damasio (2010), Gazzaniga believes that the subcortical affective system may act as an “engine,” with which any cortical module can collaborate to produce a unique conscious experience accompanied by a sense of self. Additionally, Seth (2021) recently endorsed Damasio's illumination of the role of emotion in generating experiences in his theory of consciousness based on PP. If we consider a layered architecture for consciousness, the formulation of the above integration should be

the necessary and sufficient model = the “engine” and (A or B or C or …)

In his recent work, Block (2023) distinguished our perception from cognition, which he used to argue against what he called “cognitive theories of consciousness.” Layered architecture can reconcile this apparent contradiction. From the perspective of the architecture of the layered mind, different global states may result from diverse brain regions and mechanisms. Eventually, both IIT and GNWT, as well as various other important ToCs, will be assessed for their indicative roles within a synthetic model in the meaning of layered architecture.

If we explore this architecture radically into more essential ranges, it may extend to a general version that the physical approach may help out. Our brains, as complex systems, have many components and layers of subsystems, and both Orch OR and EM fields can operate as a hierarchy across multiple levels of the brain. Hameroff (2022) argued the orders of magnitude in frequency in microtubules inside each neuron. The proponents of EM fields describe them from micro to macro scales as “stuff” of phenomenology, patterns of experiences, and phenomenal objects, respectively (Fingelkurts et al., 2013; Hales and Ericson, 2022).

Further work will focus on determining the specific interpretative position of each ToC within the layered model and will help unravel the interaction protocols between the components in the model.

Discussion

In this opinion article, we reviewed the stalemate that various theories of consciousness, each with its specific empirical support and respective plausibility, and attempted to unify these theories. Contrasting a layered architecture with the unification of traditional viewpoints suggests that it may be a more conducive approach to profoundly understand consciousness and may be compatible with competing theories.

Author contributions

ZR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant Nos. 21ZD0b1 and 18ZDA029).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Hengwei Li, Shiling Cai, Xuting Cao, and other colleagues for their suggestions on the work presented here and also the editor and two reviewers for their helpful comments on this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bayne, T., Hohwy, J., and Owen, A. M. (2016). Are there levels of consciousness? Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.03.009

Block, N. (1995). On a confusion about a function of consciousness. Behav. Brain Sci. 18, 227–247. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00038188

Block, N. (2019). What is wrong with the no-report paradigm and how to fix it. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.10.001

Boly, M., Massimini, M., Tsuchiya, N., Postle, B. R., Koch, C., Tononi, G., et al. (2017). Are the neural correlates of consciousness in the front or in the back of the cerebral cortex? Clinical and neuroimaging evidence. J. Neurosci. 37, 9603–9613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3218-16.2017

Brown, R., Lau, H., and LeDoux, J. E. (2019). Understanding the higher-order approach to consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 754–768. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.06.009

Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Del Pin, S. H., Skóra, Z., Sandberg, K., Overgaard, M., and Wierzchoń, M. (2021). Comparing theories of consciousness: why it matters and how to do it. Neurosci. Conscious. 2021, 19. doi: 10.1093/nc/niab019

Doerig, A., Schurger, A., and Herzog, M. H. (2021a). Hard criteria for empirical theories of consciousness. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 41–62. doi: 10.1080/17588928.2020.1772214

Doerig, A., Schurger, A., and Herzog, M. H. (2021b). Response to commentaries on 'hard criteria for empirical theories of consciousness'. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 99–101. doi: 10.1080/17588928.2020.1853086

Ellia, F., Hendren, J., Grasso, M., Kozma, C., Mindt, G., Lang, P. J., et al. (2021). Consciousness and the fallacy of misplaced objectivity. Neurosci. Conscious. 20, 32. doi: 10.1093/nc/niab032

Fingelkurts, A. A., Fingelkurts, A. A., and Neves, C. F. H. (2013). Consciousness as a phenomenon in the operational architectonics of brain organization: criticality and self-organization considerations. Chaos Sol. Fract. 55, 13–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2013.02.007

Fink, F. (2016). A deeper look at the “neural correlate of consciousness”. Front. Psychol. 7, 44. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01044

Gazzaniga, M. S. (2018). The Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the Mystery of How the Brain Makes the Mind. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Graziano, M. S. A. (2019a). Attributing awareness to others: the attention schema theory and its relationship to behavioral prediction. J. Conscious. Stud. 26, 17–37.

Graziano, M. S. A. (2019b). Rethinking Consciousness: A Scientific Theory of Subjective Experience. New York: Norton.

Graziano, M. S. A., Guterstam, A., Bio, B. J., and Wilterson, A. I. (2020). Toward a standard model of consciousness: reconciling the attention schema, global workspace, higher-order thought, and illusionist theories. Cog. Neuropsychol. 37, 155–172. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2019.1670630

Hales, C. G., and Ericson, M. (2022). Electromagnetism's bridge across the explanatory gap: how a neuroscience/physics collaboration delivers explanation into all theories of consciousness. Front. Human Neurosci. 16, 836046. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.836046

Hameroff, S. (2022). Consciousness, cognition and the neuronal cytoskeleton—A new paradigm needed in neuroscience. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15, 869935. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.869935

Hameroff, S., and Penrose, R. (2014). Consciousness in the universe a review of the 'orch or' theory. Physics Life Rev. 11, 39–78. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2013.08.002

Hunt, T., and Jones, M. (2023). Fields or firings? Comparing the spike code and the electromagnetic field hypothesis. Front. Psychol. 14, 1029715. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1029715

John, E. R. (2001). A field theory of consciousness. Consciousness and Cognition, 10, 184–213. doi: 10.1006/ccog.2001.0508

Koch, C. (2018). What is consciousness: scientists are beginning to unravel a mystery that has long vexed philosophers. Nature 557, 9–12. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05097-x

Koch, C., Massimini, M., Boly, M., and Tononi, G. (2016). Posterior and anterior cortex—Qhere is the difference that makes the difference? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 666. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.105

Lamme, V. A. F. (2018). Challenges for theories of consciousness: seeing or knowing, the missing ingredient and how to deal with panpsychism. Philosoph. Transact. Royal Soc. B. 373, 344. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0344

Lau, H. (2022). In Consciousness We Trust: The Cognitive Neuroscience of Subjective Experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lau, H., and Rosenthal, D. (2011). Empirical support for higher-order theories of conscious awareness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.009

Lenharo, M. (2023). Philosopher wins consciousness bet with neuroscientist. Nature 619, 14–15. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-02120-8

Mashour, G. A., Roelfsema, P., Changeux, J. P., and Dehaene, S. (2020). Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron 105, 776–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.026

McKilliama, A. (2020). What is a global state of consciousness. Philoso. Mind Sci. 1, 58. doi: 10.33735/phimisci.2020.II.58

Melloni, L., Mudrik, L., Pitts, M., and Koch, C. (2021). Making the hard problem of consciousness easier. Science 372, 911–912. doi: 10.1126/science.abj3259

Odegaard, B., Knight, R. T., and Lau, H. (2017). Should a few null findings falsify prefrontal theories of conscious perception? J. Neurosci. 37, 9593–9602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3217-16.2017

Oizumi, M., Albantakis, L., Tononi, G., and Sporns, O. (2014). From the phenomenology to the mechanisms of consciousness: integrated information theory 3.0. PLoS Comput. Biolog. 10, 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003588

Panagiotaropoulos, T. I., Wang, L., and Dehaene, S. (2020). Hierarchical architecture of conscious processing and subjective experience. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 37, 180–183. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2020.1760811

Penrose, R. (1999). The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and The Laws of Physics. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks.

Reardon, S. (2019). Rival theories face off over brain's source of consciousness. Science 366, 293. doi: 10.1126/science.366.6463.293

Safron, A. (2020). An integrated world modeling theory (iwmt) of consciousness: combining integrated information and global neuronal workspace theories with the free energy principle and active inference framework: toward solving the hard problem and characterizing agentic causation. Front. Artif. Intell. 3, 30. doi: 10.3389/frai.2020.00030

Seth, A. K. (2018). Consciousness: the last 50 years (and the next). Brain Neurosci. Adv. 2, 1–6. doi: 10.1177/2398212818816019

Seth, A. K., and Bayne, T. (2022). Theories of consciousness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 439–452. doi: 10.1038/s41583-022-00587-4

Seth, A. K., and Hohwy, J. (2021). Predictive processing as an empirical theory for consciousness science. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 2. doi: 10.1080/17588928.2020.1838467

Signorelli, C. M., Szczotka, J., and Prentner, R. (2021). Explanatory profiles of models of consciousness—Toward a systematic classification. Neurosci. Conscious. 2021, 21. doi: 10.1093/nc/niab021

Tononi, G. (2008). Consciousness as integrated information: a provisional manifesto. Biol. Bullet. 215, 216–242. doi: 10.2307/25470707

Tononi, G., Boly, M., Massimini, M., and Koch, C. (2016). Integrated information theory: from consciousness to its physical substrate. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.44

Tsuchiya, N., Wilke, M., Frässle, S., and Lamme, V. A. F. (2015). No-report paradigms: extracting the true neural correlates of consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 757–770. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.10002

Wiese, W. (2020). The science of consciousness does not need another theory, it needs a minimal unifying model. Neurosci. Conscious. 20, 13. doi: 10.1093/nc/niaa013

Keywords: consciousness, Gazzaniga, theories of consciousness, IIT, GNWT

Citation: Ruan Z (2023) The necessary and sufficient mechanism of consciousness in a layered mind. Front. Psychol. 14:1280959. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1280959

Received: 21 August 2023; Accepted: 14 September 2023;

Published: 28 September 2023.

Edited by:

Luca Simione, Università degli studi Internazionali di Roma (UNINT), ItalyReviewed by:

Alexander Fingelkurts, BM-Science, FinlandStuart Hameroff, University of Arizona, United States

Copyright © 2023 Ruan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zenan Ruan, em5ydWFuQHpqdS5lZHUuY24=

Zenan Ruan

Zenan Ruan