- 1Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Eating Disorders National Service, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Psychology, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia

Background: Social isolation, loneliness and difficulties in relationships are often described as a core feature of eating disorders. Based on the experimental research, we have designed one-off workshops for patients in inpatients and day care services and evaluated its acceptability and effectiveness using feedback questionnaires.

Methods: This naturalistic project is an evaluation of multiple positive communication workshops. Forty-one participants completed workshop questionnaires, which were provided immediately at the beginning and end of the workshop, including feedback on these one-off groups. The workshops consisted of educational and experiential components. The questionnaire outcomes were evaluated by independent researchers.

Results: All participants were female adults with a mean age of 33 (12.2) and a diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa (AN; either restrictive or binge-purge subtype). Post-workshop questionnaires showed large effect sizes in the improvement of understanding the importance and confidence in using positive communication strategies.

Discussion: Addressing social communication difficulties in eating disorder treatment programmes adds valuable dimensions to these symptom-based treatments in both inpatient settings and day services, and may provide broader benefits in overall social functioning in patients with AN.

Conclusion: Brief one-off workshops targeting social functioning for patients with eating disorders might be useful complementary input for treatment programmes.

1. Introduction

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric condition characterized by both physical health difficulties, such as low weight through intake restriction, and mental health difficulties, such as body image disturbances (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Significant social and functional difficulties are also described as core features of AN (Harrison et al., 2014). Due to the high physical and psychological risk attached to severe eating disorders (ED), professional clinical teams are often occupied with supporting individuals with their nutritional needs in intensive care programmes (i.e., inpatient and day services), through brief and symptom-targeting psychological therapies.

Difficulties in social and emotional processing are recognized as a maintaining factor for AN (Treasure and Schmidt, 2013). Previous studies have proposed that individuals with AN experience emotions to be threatening, meaning when emotions arise, they tend to engage in fasting to avoid them; thus, the symptomatic behaviour acts as a maladaptive means to regulate emotions [(e.g., Wildes et al., 2010; Treasure and Schmidt, 2013; Lynch et al., 2015)]. Studies with self-reported methodologies have also demonstrated that people with AN exhibit high levels of emotion avoidance (Wildes et al., 2010; Hambrook et al., 2011; Westwood et al., 2017), social anhedonia (defined as an absence of pleasure derived from being with people) (Tchanturia et al., 2012), and difficulties in emotion regulation (Harrison et al., 2010; Racine and Wildes, 2013; Lavender et al., 2015). Additionally, experimental studies in AN have shown increased urges to engage in diets when experiencing emotions that they perceive as negative (Wildes et al., 2012). Collectively, these studies suggest that emotion avoidance, or the avoidance of experiencing and expressing emotions (Wildes et al., 2010) may be a characteristic feature of the way in which emotions are processed in people with AN.

Furthermore, in recent years a series of experimental studies have investigated the difficulties of expressing emotions in people with AN. A meta-analysis found that, when exposed to film clips eliciting emotions, participants with AN showed reduced spontaneous facial expression of both positive and negative emotion, compared to healthy controls (HC), with a large and medium effect size, respectively, Davies et al. (2016) and Leppanen et al. (2017). Additionally, there is preliminary evidence to suggest that participants with AN are less accurate than HC when deliberately attempting to show facial expressions of emotions (Dapelo et al., 2016).

Interestingly, findings suggest that individuals who have recovered from AN tend to express more positive emotions facially than those in the acute phase of the illness (Davies et al., 2013; Dapelo et al., 2016), which is in line with the hypothesis that these socioemotional difficulties contribute to the maintenance of the ED.

Besides its possible role as a perpetuating factor for AN, the avoidance of expressing emotions may impact the ability of individuals with AN to build and maintain social relationships, affecting their social functioning. For example, expressing positive emotions play a key role in establishing rapport and alliance in social interactions (Schmidt and Cohn, 2001), even expressing negative emotions, such as sadness or anger, may have positive effects on affiliation by promoting responsiveness and a sense of intimacy in social relationships (Fischer et al., 2008; Graham et al., 2008). Furthermore, studies on individuals with limited facial expression indicate that they are perceived as reserved and unhappy, and report being less interested in establishing friendship ties with them (Tickle-Degnen and Lyons, 2004; Hemmesch et al., 2009; Bogart et al., 2014). Individuals with AN have also reported feelings of isolation (Robinson et al., 2015), difficulties establishing friendships (Doris et al., 2014; Westwood et al., 2016; Sedgewick et al., 2019; Datta et al., 2021), and a negative impact of the disorder in the social arena (Tchanturia et al., 2013). Evidence within the literature suggests that emotion avoidance may be a contributing factor for the reported social difficulties in individuals with AN.

The social difficulties reported in the literature by people with AN, warrant the establishing for treatment strategies aimed at enhancing emotion expression. Cognitive remediation and emotion skills training (CREST) is a manualised treatment for inpatients with severe AN that was developed with the purpose of targeting emotional processing through psychoeducation and interactivity (Money et al., 2011; Tchanturia et al., 2014, 2015).

Research exploring the effects of CREST in people with AN shows that those who engaged in CREST exhibited a decrease in social anhedonia and in self-reported alexithymia, and provided positive qualitative feedback (Money et al., 2011; Tchanturia et al., 2014). CREST is still under development and there is continuous effort to improve outcomes by modifying its interventions based on research evidence and on patient’s feedback.

In this context, we designed a single-session workshop with the goal of raising awareness of the importance of enhancing positive communication and emotional expression in those receiving treatment for AN. The workshop was delivered in groups and lasted 90 min. We named the workshop as a “Positive Communication Workshop” to emphasize the positive, welcoming character of the intervention, rather than focusing on emotions per se, which could feel more threatening and anxiety-provoking for participants. The workshop included psychoeducation as well as activities designed to increase non-verbal expression of emotions and promoting eye gaze, and reflection. Details on the workshop content and activities are provided in the appendix number 1.

The present study aimed to pilot a single session workshop with the goal of raising awareness of the importance in enhancing positive communication and emotional expression in those receiving treatment for AN; whilst also learning from participants’ views about this workshop. Specifically, our aims were to: (1) explore the feasibility of positive communication workshops in ED inpatients’ and day services’ treatment programmes; (2) to evaluate feedback from patients; and (3) to plan future potential developments with positive communication workshops.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

A total of 41 participants took part in the workshop. All participants were female adults aged between 18 and 50 years old, with the mean age at 33 (SD = 12.2). Participants had a diagnosis of AN according to the DSM-5, were in various stages of their illness, and were receiving treatment through either an inpatient admission or day services at South London and Maudsley Specialist Eating Disorder Services. All participants were of consecutive admissions to clinical services. There were no exclusion criteria, everyone admitted to these services were invited to participate in the workshop. Study permission was obtained from the local research and governance committee at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

2.2. Self-report measures

All workshop participants were asked to complete 2 questionnaires, one before and one after the workshop. In addition, participants completed a feedback form at the end of the workshop. All the measures were designed by the investigators to obtain feedback from participants in every-day clinical practice:

2.2.1. Pre-workshop questionnaire

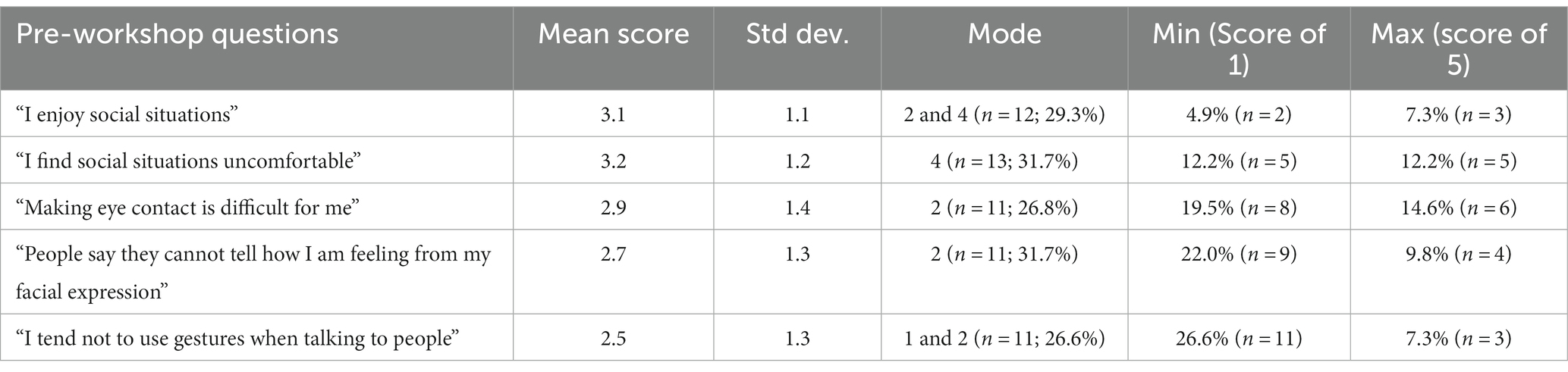

The questionnaire was designed to enable participants to rate their understanding of their own communication styles prior to attending the workshop (Appendix 2). This pre-workshop questionnaire consisted of 5 questions: 1. “I enjoy social situations; 2. “I find social situations uncomfortable”; 3. “Making eye contact with people is difficult for me”; 4. “People say they cannot tell how I am feeling from my facial expressions”; and 5. “I tend not to use gestures when talking to people.” It used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Completely disagree”) to 5 (“Agree completely”).

2.2.2. Post-workshop questionnaire

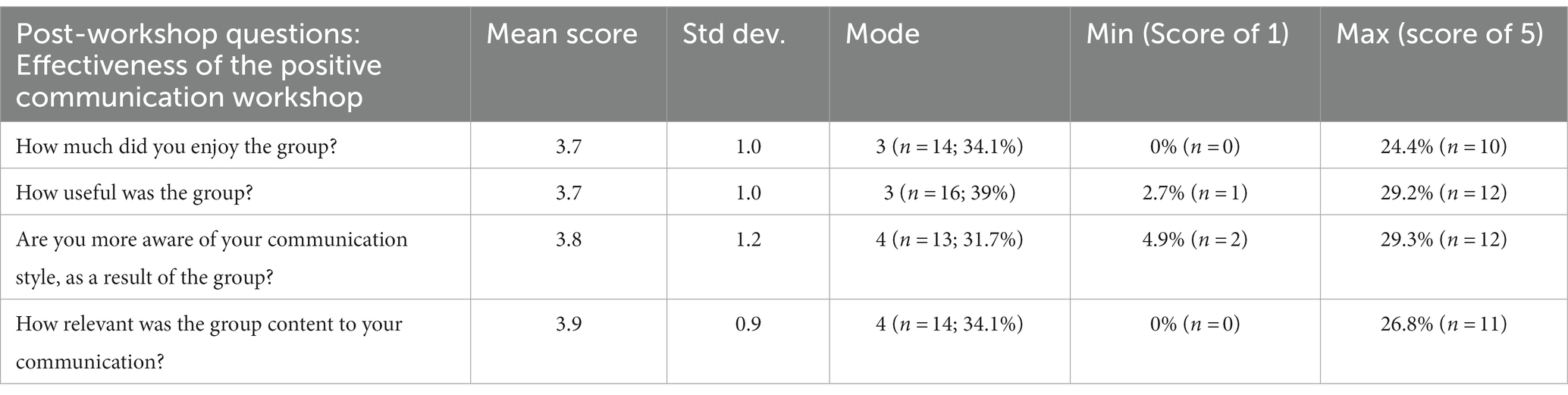

This post-workshop questionnaire had two groups of questions (Appendix 2). The first group of questions assessed the effectiveness of the workshop, questions included: 1. “How much did you enjoy the group?”; 2. “How useful was the group?”; 3. “Are you more aware of your communication styles as a result of the group?”; and 4, “How relevant was the group content to your communication?” The second group of questions assessed their understanding of the importance and their confidence in different communication styles including: eye contact; tone of voice; facial expression; and body language. This questionnaire also used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Very”).

2.2.3. Feedback questionnaire

Feedback form with two open-ended questions asking participants what they liked most about the workshop and if they had any suggestions for improvements (Appendix 3).

2.3. Procedure

The workshop protocol was developed in collaboration with researchers and clinicians in the Eating Disorder Services at SLaM. The workshop consisted of three interactive activities, followed by a reflective component (Appendix 1).

After introducing themselves, workshop facilitators (N = 2) alternated in providing a brief overview of the experimental research about positive communication. This included an introduction on the importance of body language, tone of voice, and smiling as a social rewarding signal. Facilitators then shared current research findings on the poor use of positive emotional signaling in eating disorders followed by practical exercises. Psychoeducational materials in addition to these exercises were adapted from the actors training programmes by principal author (KT). Before they were included in the workshop format, these exercises were evaluated and calibrated for the purpose by KT and her research lab.

The session started with a psychoeducation section, in which the relevance of expressing emotions and communicating inner states for social functioning in the context of eating disorders was explained. This section was conducted in an interactive format, with the use of videos, and graphical images.

Then, three interactive activities were carried out, the first of which aimed to promote eye gaze. The other two activities encouraged participants to increase their expressivity using games involving the imitation of others’ facial emotional expressions, and non-verbal communication of positive emotions. Following this, the participants were given time to reflect and to relate the content of the interactive activities to the importance of communicating emotions in daily life.

The psychoeducation and interactive elements of this workshop were developed to make the workshop easier to engage with. Flyers were produced to invite patients under inpatient and day services care to attend these workshops. Pre- and post- workshop questionnaires were collected at the beginning and end of the workshop (Table 1). Participants of the workshop were also provided with information leaflets to refer to after the workshop.

2.4. Data analysis

Feedback provided in the pre- and post-workshop questionnaires was analysed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 27, with frequencies and exploratory statistics (means, SD, min, max and mode). The post-workshop questionnaires (Table 2) were analysed using a paired samples t-test.

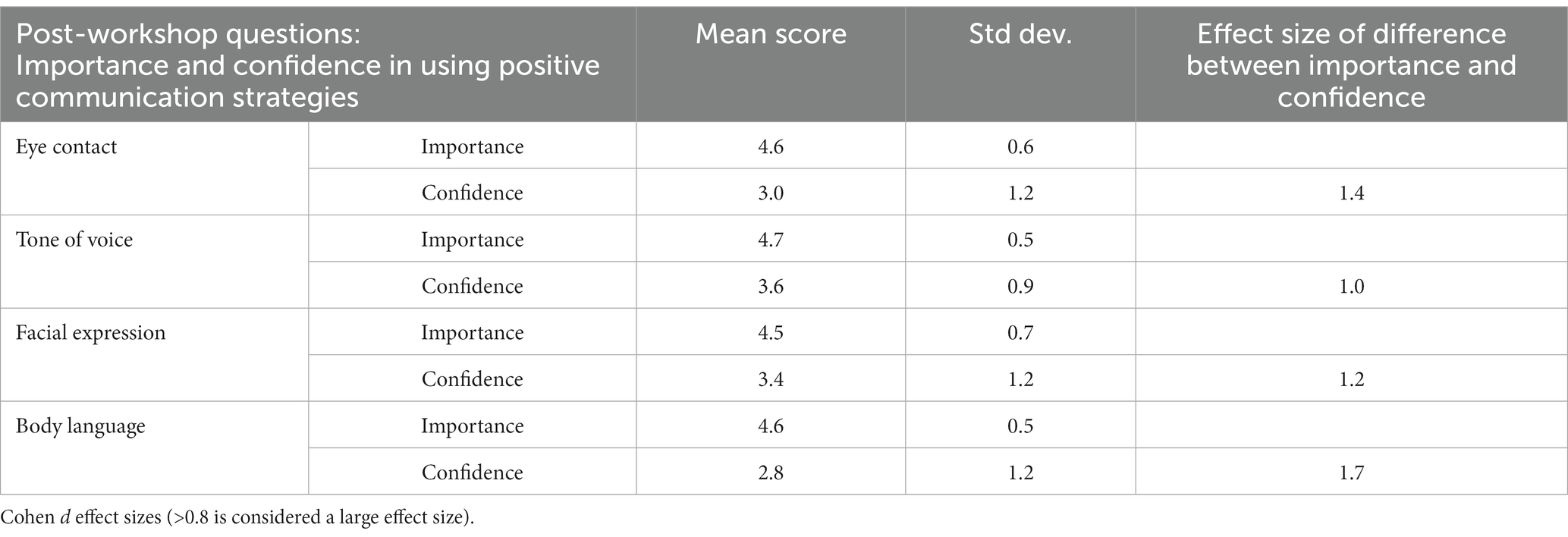

Table 2. Exploratory statistics from post-workshop questionnaire, comparing participants’ understanding of the importance and confidence in using positive communication strategies (n = 37).

Qualitative data was obtained from the participants’ responses on the following questions in the feedback questionnaire: “What did you like most about the group,” and “Ideas for improvements.” Two researchers independently identified themes from these responses before comparing and agreeing themes identified in their meeting. This data was then analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

3. Results

In total, 41 patients attended a positive communication workshop and completed questionnaires. Four of these participants had incomplete data as they had returned completed post-workshop questionnaires. There were also ten other participants who attended the workshops, however, they only expressed their feedback verbally, and so this was not included in the analysis to keep the report consistent.

3.1. Quantitative feedback from participants

The results show in the post-workshop questionnaires, that participants rated highly the relevance and usefulness of the communication styles demonstrated in the workshop (Table 3). Participants also rated the importance of using positive communication strategies higher than their confidence to use them with a large effect size on all domains (Table 2).

3.2. Qualitative feedback from participants

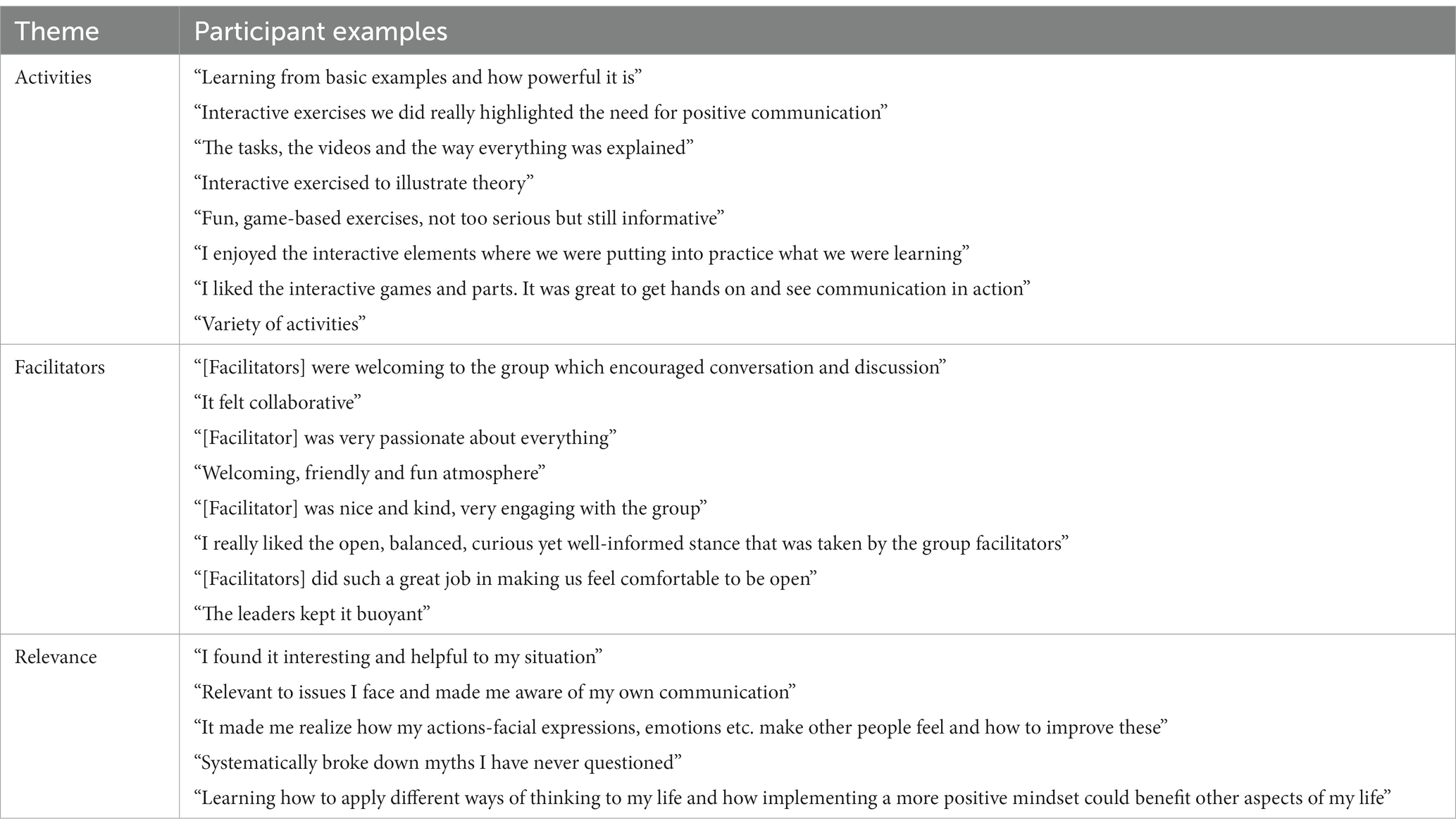

Qualitative feedback was collected using open-ended questions in both inpatient and day services programmes in order to improve future workshop content and delivery. Overall, both written and verbal feedback was very positive. Inductive thematic analysis was used to identify themes in the comments provided. Three key themes were identified for both questions and are summarized below (examples of quotes for each theme are in given in Tables 4, 5):

3.2.1. What I liked the most

3.2.1.1. Activities

Participants expressed that the activities in the workshop demonstrating and practicing different positive communication strategies were fun, engaging and interactive.

3.2.1.2. Facilitators

Participants reported that the group facilitators were welcoming, kind, and friendly.

3.2.1.3. Relevance

Participants commented that the psychoeducational materials were useful, informative, relevant, and that the content of the workshop was interesting.

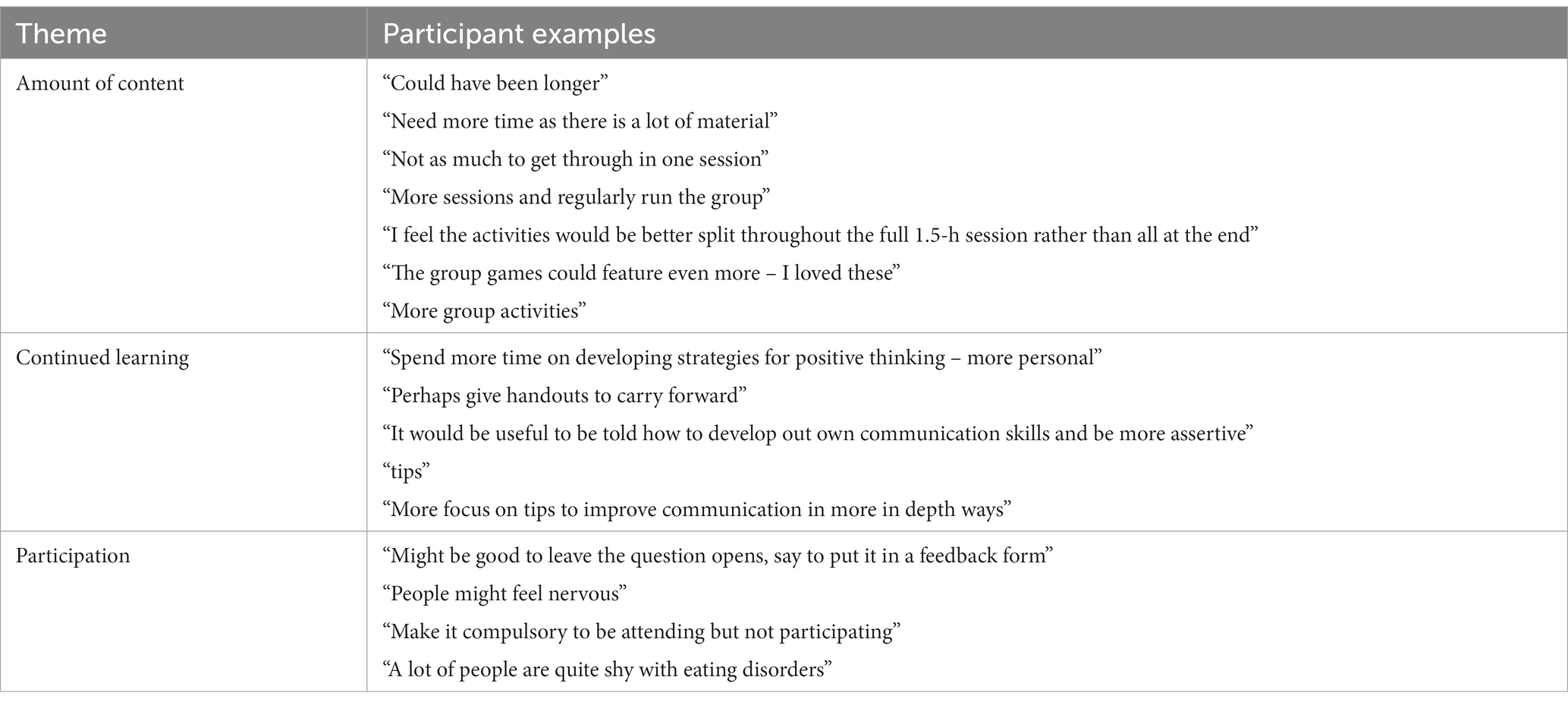

3.2.2. Ideas for improvements

3.2.2.1. Amount of content

Participants commented that there was considerable amount of content to cover in the time given for the workshop. Suggestions were made to either include less content, allow more time or to find a better balance of content and activities.

3.2.2.2. Continued learning

Participants expressed that they could have benefitted from more time and practice on developing these strategies outside of the workshop and would have liked more materials that they could take away with them.

3.2.2.3. Participation

Participants reported they would have preferred participation in discussions and activities to have been optional rather than expected throughout the workshop.

In total, 80% of the workshop participants returned completed questionnaires and the feedback was largely positive (Table 4). There were a number of suggestions for improvements to the workshop including having more time, more interactive games and group activities and further detailed handouts to provide post-workshop (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The data from this study, along with previous research demonstrating positive patient experience and clinical outcomes in group therapies (Sparrow and Tchanturia, 2016), indicated that there is feasibility for group workshops to be delivered as add-ons in the ED treatment programme.

Findings from the pre-workshop questionnaire suggest that the patients attending the workshop were aware of their difficulties in social interactions, such as finding social situations difficult and having problems with eye contact, expressing emotions and engaging in social communication. This is in line with findings from experimental studies demonstrating that individuals with AN show significantly less eye contact than healthy controls (Harrison et al., 2018), they also spend less time watching social stimuli (Kerr-Gaffney et al., 2022). As expected, we found a large effect size difference in participant’s self-reported ratings of the importance and their confidence in using eye contact, tone of voice, body language in the communication; suggesting that participants found all key elements of effective communication important but were not confident using this knowledge in real life situations. The results from the post-workshop questionnaire indicate that patients found the workshop content relevant, useful, and were more aware of their communication style as a result.

The positive feedback elicited from participants on the feedback questionnaires highlights the acceptability of the positive communication group workshop. Participants generally found the group experience positive, and feedback from the workshop indicated that the majority of participants found it helpful. They particularly enjoyed the interactive and easy nature of the workshop, in addition to learning about different positive communication strategies and how they have an impact on their lives. The positive feedback and acceptability of the intervention suggests that developing these workshops further has potential.

The feedback obtained in the post-workshop questionnaires also suggested further improvements that could be made to enhance the workshop. In the themes that emerged, there would be merit to explore, in future workshops, increasing the time of the session and developing the take-away materials to allow maximum benefit of the content. It would also be interesting to examine the differences in outcomes and feedback of these potential workshop developments with the current evaluation.

The idea of further opportunities post-workshop to practice positive communication skills is an interesting one. Individuals with AN receiving inpatients or day services treatment will often remain isolated and avoid contact with other patients, thus, it could be worthwhile for services to observe participants’ use of the skills at post-workshop. This could be in the form of follow-up opportunities with workshop participants within clinical services to evaluate the use of the learned skills in everyday life and provide further support.

Moreover, it would be interesting to assess the usefulness of carrying out this workshop in younger patients. Even though there is evidence that social anxiety increases with age (Kerr-Gaffney et al., 2018) it is relevant to note that social anxiety and interpersonal difficulties usually begin before the onset of the eating disorder and can predispose to the development of AN (Treasure et al., 2020). Therefore, providing tools to enhance positive communication and emotional expression early on to adolescent patients with AN might have a positive impact, preventing these social difficulties from becoming more severe.

This pilot study has some strengths worth mentioning, it is the first case series of its kind, reporting on pilot work with positive communication workshops. It contains a protocol allowing others to replicate and develop the workshop and has allowed us to suggest improvements to the existing protocol, which paves the way for these workshops to be trialed in larger studies. This pilot study aimed to explore the feasibility of the one-off positive communication workshops and subjective outcomes and concludes acceptability and feasibility of these workshops, meeting objectives 1 and 2. Follow-up studies would benefit from more objective evaluation based on investigator-administered scales of communication styles and other variables.

The group intervention design of the workshop is another strength. Psychological group interventions can generally bring unique benefits that are not achievable when working individually with patients. These benefits include sharing experiences and learning from others in a safe and therapeutic environment, being with other people and practicing interpersonal skills. Individuals with AN have difficulties with social contacts, and report high levels of social anhedonia (Harrison et al., 2014; Kerr-Gaffney et al., 2018). It has been observed that patients with AN often remain isolated and tend to avoid communicating with other patients in the intensive treatment programmes (Hambrook et al., 2011; Tchanturia et al., 2012; Doris et al., 2014; Westwood et al., 2016). Therefore, by employing a group design for the workshop, these benefits are promoted.

In terms of limitations, we note that there is an absence of a control group in this evaluation. Future studies would benefit from including a control group, larger numbers of participants and additional measures to capture change before and after the intervention in comparison to healthy controls. For specificity, this study only included patients with an AN diagnosis, and it would be valuable to investigate other ED diagnoses and comorbidities in future studies. It will be important for future studies to have clarity and analyse subgroups with and without an autism comorbidity to explore the question of the similarities and differences between these groups in response to treatment.

5. Conclusion

Positive communication workshops seem to be a feasible format for patients with AN. This pilot demonstrated that the workshop was able to enhance patients’ awareness of their communication and gave opportunity to learn strategies to enhance their confidence in managing social communication. Improving awareness of communication styles may help participants to manage distress and form healthy coping mechanisms, further supporting their recovery from EDs and understand their social interaction style.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of the participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to S2F0ZS50Y2hhbnR1cmlhQGtjbC5hYy51aw==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the South London and Maudsley Clinical governance board (2009/09). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. All participants were age 18 and above and consented to publish the data anonymously.

Author contributions

KT and MD: conceptualization. KT: methodology and supervision. PC: formal analysis, VH and PC: investigation. KT, PC, and VH: data curation. KT, PC, VH, and MD: writing review and editing. JW, PC, and VH: project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

KT received the funding from UKRI Medical Research Council (MRC-MRF) Fund [MR/R004595/1].

Acknowledgments

KT would like to thank the Maudsley Charity for the assistance to conduct this study. We would like to thank Staff and patients in the Eating disorder Service in South London and Maudsley NHS foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1234928/full#supplementary-material

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Edn.). American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA.

Bogart, K., Tickle-Degnen, L., and Ambady, N. (2014). Communicating without the face: holistic perception of emotions of people with facial paralysis. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 36, 309–320. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2014.917973

Dapelo, M. M., Bodas, S., Morris, R., and Tchanturia, K. (2016). Deliberately generated and imitated facial expressions of emotions in people with eating disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 191, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.044

Dapelo, M. M., Hart, S., Hale, C., Morris, R., and Tchanturia, K. (2016). Expression of positive emotions differs in illness and recovery in AN. Psychiatry Res. 246, 48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.09.014

Datta, N., Foukal, M., Erwin, S., Hopkins, H., Tchanturia, K., and Zucker, N. (2021). A mixed-methods approach to conceptualizing friendships in anorexia nervosa. PLoS One 16:e0254110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254110

Davies, H., Schmidt, U., and Tchanturia, K. (2013). Emotional facial expression in women recovered from AN. BMC Psychiatry 13, 1–29. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-291

Davies, H., Wolz, I., Leppanen, J., Fernandez-Aranda, F., Schmidt, U., and Tchanturia, K. (2016). Facial expression to emotional stimuli in non-psychotic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 64, 252–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.015

Doris, E., Westwood, H., Mandy, W., and Tchanturia, K. (2014). A qualitative study of friendship in patients with anorexia nervosa and possible autism Spectrum disorder. Psychol 5, 1338–1349. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.511144

Fischer, A., and Manstead, A. (2008). “Social functions of emotion” in Handbook of emotions. eds. M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, and L. F. Barrett. 3rd ed (New York, NY, USA: The Guildford Press), 456–468.

Graham, S. M., Huang, J. Y., Clark, M. S., and Helgeson, V. S. (2008). The positives of negative emotions: willingness to express negative emotions promotes relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 394–406. doi: 10.1177/0146167207311281

Hambrook, D., Oldershaw, A., Rimes, K., Schmidt, U., Tchanturia, K., Treasure, J., et al. (2011). Emotional expression, self-silencing, and distress tolerance in anorexia nervosa and chronic fatigue syndrome. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 50, 310–325. doi: 10.1348/014466510X519215

Harrison, A., Mountford, V., and Tchanturia, K. (2014). Social anhedonia and work and social functioning in the acute and recovered phases of eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 218, 187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.007

Harrison, A., Sullivan, S., Tchanturia, K., and Treasure, J. (2010). Emotional functioning in eating disorders: attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol. Med. 40, 1887–1897. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000036

Harrison, A., Watterson, S. V., and Bennett, S. D. (2018). An experimental investigation into the use of eye-contact in social interactions in women in the acute and recovered stages of anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 52, 61–70. doi: 10.1002/eat.22993

Hemmesch, A. R., Tickle-Degnen, L., and Zebrowitz, L. A. (2009). The influence of facial masking and sex on older adults' impressions of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Psychol. Aging 24, 542–549. doi: 10.1037/a0016105

Kerr-Gaffney, J., Harrison, A., and Tchanturia, K. (2018). Social anxiety in the eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 48, 2477–2491. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000752

Kerr-Gaffney, J., Jones, E., Mason, L., Hayward, H., Murphy, D., Loth, E., et al. (2022). Social attention in anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorder: role of social motivation. Autism 26, 1641–1655. doi: 10.1177/13623613211060593

Lavender, J. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Engel, S. G., Gordon, K. H., Kaye, W. H., and Mitchell, J. E. (2015). Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 40, 111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.010

Leppanen, J., Dapelo, M. M., Davies, H., Lang, K., Treasure, J., and Tchanturia, K. (2017). Computerised analysis of facial expression in eating disorders. PLoS One 12:13, 1, e0178972–e0178976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178972

Lynch, T. R., Hempel, R. J., and Dunkley, C. (2015). Radically open-dialectical behavior therapy for disorders of over-control: signaling matters. Am. J. Psychother. 69, 141–162. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.141

Money, C., Genders, R., Treasure, J., Schmidt, U., and Tchanturia, K. (2011). A brief emotion focused intervention for inpatients with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. J. Health Psychol. 16, 947–958. doi: 10.1177/1359105310396395

Racine, S. E., and Wildes, J. E. (2013). Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of anorexia nervosa: the unique roles of lack of emotional awareness and impulse control difficulties when upset. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 46, 713–720. doi: 10.1002/eat.22145

Robinson, P. H., Kukucska, R., Guidetti, G., and Leavey, G. (2015). Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SEED-AN): a qualitative study of patients with 20+ years of anorexia nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 23, 318–326. doi: 10.1002/erv.2367

Schmidt, K. L., and Cohn, J. F. (2001). Human facial expressions as adaptations: evolutionary questions in facial expression research. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 116, 3–24. doi: 10.1002/Ajpa.20001

Sedgewick, F., Lappanen, J., and Tchanturia, K. (2019). The friendship questionnaire, autism and gender differences: a study revisited. Mol. Autism 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0295-z

Sparrow, K. A., and Tchanturia, K. (2016). Inpatient brief group therapy for anorexia nervosa: patient experience. Int. J. Group Psychother. 66, 431–442. doi: 10.1080/00207284.2016.1156406

Tchanturia, K., Davies, H., Harrison, A., Fox, J. R., Treasure, J., and Schmidt, U. (2012). Altered social hedonic processing in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45, 962–969. doi: 10.1002/eat.22032

Tchanturia, K., Doris, E., and Fleming, C. (2014). Effectiveness of cognitive remediation and emotion skills training (CREST) for anorexia nervosa in group format: a naturalistic pilot study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 22, 200–205. doi: 10.1002/erv.2287

Tchanturia, K., Doris, E., Mountford, V., and Fleming, C. (2015). Cognitive remediation and emotion skills training (CREST) for anorexia nervosa in individual format: self-reported outcomes. BMC Psychiatry 15:53. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0434-9

Tchanturia, K., Hambrook, D., Curtis, H., Jones, T., Lounes, N., Fenn, K., et al. (2013). Work and social adjustment in patients with anorexia nervosa. Compr. Psychiatry 54, 41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.03.014

Tickle-Degnen, L., and Lyons, K. D. (2004). Practitioners' impressions of patients with Parkinson's disease: the social ecology of the expressive mask. Soc. Sci. Med. 58, 603–614. doi: 10.1016/s0277-95369(03)00213-2

Treasure, J., and Schmidt, U. (2013). The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: a summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. J. Eat. Disord. 1, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-13

Treasure, J., Willmott, D., Ambwani, S., Cardi, V., Clark Bryan, D., Rowlands, K., et al. (2020). Cognitive interpersonal model for anorexia nervosa revisited: the perpetuating factors that contribute to the development of the severe and enduring illness. J. Clin. Med. 9:630. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030630

Westwood, H., Kerr-Gaffney, J., Stahl, D., and Tchanturia, K. (2017). Alexithymia in eating disorders: systematic review and meta-analyses of studies using the Toronto alexithymia scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 99, 66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.007

Westwood, H., Lawrence, V., Fleming, C., and Tchanturia, K. (2016). Exploration of friendship experiences, before and after illness onset in females with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. PLoS One 11, 1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163528

Wildes, J. E., Marcus, M. D., Bright, A. C., and Dapelo, M. M. (2012). Emotion and eating disorder symptoms in patients with anorexia nervosa: an experimental study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45, 876–882. doi: 10.1002/eat.22020

Keywords: eating disorders, group, positive psychology, communication, brief therapy, treatment

Citation: Tchanturia K, Croft P, Holetic V, Webb J and Dapelo MM (2023) Positive communication workshops: are they useful for treatment programmes for anorexia nervosa? Front. Psychol. 14:1234928. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1234928

Edited by:

Chao Liu, Huaqiao university, ChinaReviewed by:

Sarah Maguire, The University of Sydney, AustraliaOctavian Vasiliu, Dr. Carol Davila University Emergency Military Central Hospital, Romania

Copyright © 2023 Tchanturia, Croft, Holetic, Webb and Dapelo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kate Tchanturia, S2F0ZS50Y2hhbnR1cmlhQGtjbC5hYy51aw==

Kate Tchanturia

Kate Tchanturia Philippa Croft2

Philippa Croft2 Victoria Holetic

Victoria Holetic Jessica Webb

Jessica Webb