- 1Department Humanism and Social Resilience, University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2ARQ National Psychotrauma Center, Diemen, Netherlands

- 3Scientific Information Service, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 4Department of Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden

- 5Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, National Research Center in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFKAM), Arctic University of Norway (UiT), Tromsø, Norway

Introduction: Throughout history, Jewish communities have been exposed to collectively experienced traumatic events. Little is known about the role that the community plays in the impact of these traumatic events on Jewish diaspora people. This scoping review aims to map the concepts of the resilience of Jewish communities in the diaspora and to identify factors that influence this resilience.

Methods: We followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology. Database searches yielded 2,564 articles. Sixteen met all inclusion criteria. The analysis was guided by eight review questions.

Results: Community resilience of the Jewish diaspora was often described in terms of coping with disaster and struggling with acculturation. A clear definition of community resilience of the Jewish diaspora was lacking. Social and religious factors, strong organizations, education, and communication increased community resilience. Barriers to the resilience of Jewish communities in the diaspora included the interaction with the hosting country and other communities, characteristics of the community itself, and psychological and cultural issues.

Discussion: Key gaps in the literature included the absence of quantitative measures of community resilience and the lack of descriptions of how community resilience affects individuals’ health-related quality of life. Future studies on the interaction between community resilience and health-related individual resilience are warranted.

1. Introduction

“A sustainable human community must be designed in such a manner that its ways of life, its businesses, its economy, physical structures, technologies, and social institutions, do not interfere with nature’s inherent ability to sustain life” (Capra and Luisi, 2014).

Jewish communities worldwide have a long and continuous history of traumatic events. The adaptation of Jewish individuals to these traumatic events, especially the Holocaust, has been well documented (Stein, 2009; Keysar, 2014; Lurie, 2017; Diamond et al., 2020; Zimmermann and Forstmeier, 2020). However, research institutions such as the Institute for Jewish Policy Research have mostly reported on community resilience in Israel (Institute for Jewish Policy Research, 2015; Dellapergola and Staetsky, 2020). This paper is based on the assumption that it is also important to understand how the Jewish communities affect the resilience, life, and health of Jewish people living in the diaspora outside Israel.

In this paper we define Jewish diaspora communities as the core and enlarged Jewish population, as described by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research (Institute for Jewish Policy Research, 2015). According to recent numbers (The Jewish Agency for Israel, 2022) 8.25 million Jews live outside Israel (55% of the 15.3 million Jews worldwide). Most of them live in the United States (6 million). Other countries hosting Jewish diaspora communities are France (446.000), Canada (393.500), Great Britain (292.000), Argentina (175.000), Russia (150.000), Germany (118.000), Australia (118.000) or smaller communities, such as the Netherlands (30.000–50.000) (Van Solinge and de Vries, 2001; Van Solinge et al., 2010). Around 38 countries worldwide have a Jewish population of 500 people or fewer.

The concept of resilience has been applied in many scientific disciplines and is one of the core concepts in contemporary social studies (Van der Schoor et al., 2021; Derakhshan et al., 2022). Resilience is often studied from an individual perspective, even though many of these studies have stressed the relevance of the social dimension to maintain and strengthen people’s resilience: the role of the family, the neighborhood, and the community (Bronfenbrenner et al., 1986; van der Kolk, 2014).

In the research literature, three perspectives on resilience can be distinguished (Pfefferbaum et al., 2015; Verbena et al., 2021). First, the resource-based perspective focuses on certain core attributes and resources that resilient entities possess (Tengblad and Oudhuis, 2018). Second, the outcome-based perspective focuses on positive outcomes amidst adversity (Bonanno, 2004; Bonanno et al., 2015). Last, the process-based perspective explores the working mechanisms involved in navigating using resources in the context of adversity to achieve a positive outcome (Norris et al., 2008). This ‘fluctuating’ process is described as a phenomenon occurring through interactions within and between multiple levels, i.e., individual, community, and society (Infurna and Luthar, 2018; Wiles et al., 2019).

In recent decades, there is growing interest in the meaning of the community for individual resilience (Hobfoll et al., 2007; van der Kolk, 2014) and the need for a better understanding of the concept of community resilience. It has been reported that contextual factors, such as the family or the community in which people live, are likely to exert more influence on individual resilience outcomes than individual traits (Landau, 2007; Ungar, 2011; Fischer and McKee, 2017). Several authors have highlighted the relevance to gain a better understanding of the dynamics between community resilience and individual resilience (Norris et al., 2008). Others study the impact of traumatic events on the resilience and health of individuals (Duckers et al., 2017; South et al., 2018) as there is growing evidence of a relationship between somatic and psychological conditions, social context, well-being, and functioning (Scott et al., 2013; Huber, 2014).

A systematic review of community resilience concluded that community resilience remains an amorphous concept that is understood and applied differently by different research groups (Patel et al., 2017). Depending on the perspective of the author, community resilience is, respectively, seen as a continuous adaption process to adversity, the absence of negative effects, the presence of various positive factors, or a combination of all three. Although the definitions differ, Patel et al. (2017) found nine main categories which were subdivided into nineteen sub-elements of community resilience that were common among the definitions in the reviewed scientific articles on disasters. The main elements they mentioned were local knowledge, community networks and relationships, communication, health, governance and leadership, resources, economic investment, preparedness, and mental outlook. Patel et al. (2017) suggest for future research to focus on these main elements as they can be measured and improved, which may contribute to understanding as well as policy making.

While the review of Patel et al. concentrated on the literature on disasters, Flora et al. (2016) focused their research on the dynamic process of communities constantly changing and responding to adversities. Based on that, they developed a theoretical model, the Community Capital Framework, that consists of seven resource categories or ‘capitals’: three material capitals – natural, built, and financial – and four immaterial capitals – human, social, cultural, and political. Van der Schoor (2020)1 assumes these resources can function in several ways, (1) as a buffer against the impact of adversity, (2) as compensation for the negative effects of the adversity and (3) as a catalyst of community members’ ability to change or transform the structural conditions of adversity. Comparable models, in which several capitals are defined can be found in studies aiming to measure community resilience (Mayunga, 2009; Derakhshan et al., 2022).

Though some research has been conducted on the resilience of diaspora communities (Kidron, 2012; Smid et al., 2018; Alefaio-Tugia et al., 2019), there is currently no published systematic overview on the factors that hinder or strengthen the resilience of communities living in the diaspora. Therefore, we aimed to conduct a systematic review of the existing literature on the resilience of Jewish communities living in the diaspora to identify factors that influence community resilience. A scoping review was considered the most suitable type of systematic review method for this purpose, as it is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses exploratory research questions aimed at mapping key concepts, identifying key characteristics related to these concepts, examining how research is conducted on that topic, and identifying knowledge gaps (Colquhoun et al., 2014). The current scoping review intends to inform researchers on how to design future studies on drivers and barriers of diasporic community resilience and inform policymakers, leaders, and members of communities on methods to strengthen the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities outside Israel. A preliminary search for existing reviews on this topic was conducted in PROSPERO, MEDLINE, databases of the Joanna Briggs Institute, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. No protocols for a similar scoping review were identified.

2. Method

The predefined protocol for this scoping review was published in the public domain (Meijer et al., 2022). The protocol followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewers’ Manual for scoping reviews (Aromataris et al., 2020; Jong et al., 2021) and guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews as published by Peters et al. (2020). Results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al., 2018; Supplementary File 1). Since a scoping review analyzes data already published in the literature, no ethical review was needed.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

To identify and define the main concepts in the review questions the Participants/Concept/Context (PCC) framework was used (Peters et al., 2021). The PCC framework is recommended by JBI as a guide to formulate the main review questions of the scoping review.

2.2. Participants

We included studies about Jewish communities worldwide that describe Jewish persons aged 18 years and older. We defined Jewish communities as the core and enlarged Jewish population, as described by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research (Institute for Jewish Policy Research, 2015). The core Jewish population includes people who self-identify as Jewish in social surveys and do not have another monotheistic religion. It also includes people who may not recognize themselves as Jewish but have Jewish parents and have not adopted a different religious identity. It further consists of all converts to Judaism by any procedure and other people who declare themselves Jewish, even without having undergone conversion. The enlarged Jewish population includes the sum of (a) the core Jewish population; (b) all other people of Jewish parentage who, by core Jewish population criteria, are not currently Jewish (e.g., they have adopted another religion or otherwise opted out); and (c) all respective non-Jewish household members (spouses, children, etc.).

2.3. Concept

Resilience is defined as the ability to withstand adversity and the capacity to bounce back from potentially traumatic events (Vanhamel et al., 2021). Articles on closely related concepts, such as coping, recovery, dealing with adversity, adaptation, and acculturation were included in the review. Articles included were not limited to resilience in relation to health or healthcare. Articles describing individual resilience only, without mentioning a link to the community or contextual variables, were excluded. Articles that describe the resilience of Jewish communities in relation to historical events before the Second World War were also excluded.

2.4. Context

Diasporic communities are defined as communities of people who live outside their shared country of origin or ancestry but maintain passive or active connections with it (Nazeer, 2015). A diaspora includes both emigrants and their descendants. In this scoping review, Israel is not considered a diaspora; therefore, studies on Jewish communities in Israel were excluded.

2.5. Objectives

The review addressed the following questions:

Review question 1. What concepts of resilience are being described for Jewish communities living in the diaspora? How is resilience defined, and which underlying theoretical models have been used to understand how the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities functions?

Review question 2. Which trauma or underlying causes of stress (e.g., Holocaust, genocides, or racism) are described in relation to the resilience of Jewish communities living in the diaspora?

Review question 3. Which facilitating factors for the resilience of Jewish communities in the diaspora are described?

Review question 4. Which barriers to the resilience of Jewish communities in the diaspora are described?

Review question 5. What methods are used in studies to measure the resilience of communities?

Review question 6. What is described about the relationship between the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities and the health-related quality of life of individuals belonging to the community?

Review question 7. What are the key gaps in the literature on the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities?

Review question 8. Are there any ethical issues or challenges identified that relate to the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities?

2.6. Types of sources

The selected studies describe peer-reviewed scientific research publications on quantitative and qualitative methodologies, including randomized controlled trials, controlled (non-randomized) clinical trials, controlled before-after studies, prospective and retrospective comparative clinical studies, non-controlled prospective and retrospective observational studies, cohort studies with before-after design, case series, case reports, qualitative studies, PhD theses, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, meta-syntheses, narrative reviews, mixed-methods reviews, qualitative reviews, and rapid reviews. Studies published as master’s or bachelor’s theses, information from books or book chapters, analyses/reviews of books, and analyses/reviews of movies were excluded because we considered them to be outside the scope of the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Conference reports/proceedings were also excluded because they may not contain adequate detailed information for our scoping review and/or describe preliminary data.

2.7. Search strategy and study selection

Two information specialists developed the search strategy (Supplementary File 2) aiming to locate studies already published in the literature. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) (or comparable controlled vocabularies) and free text terms (terms in the title and/or abstract of the articles) were used in databases with controlled vocabulary. The search strategy was adapted broadly in databases without controlled vocabularies to obtain the maximum search yield. In addition to the database searches, the reference lists of articles selected for full-text review were screened for additional studies. In the searches, no restrictions were applied to the study design, date, or language. However, only articles published in English, Danish, Dutch, German, Hebrew, Norwegian, and Swedish were included. Articles published after World War II to the present were included. Excluded were articles describing the resilience of Jewish communities in relation to earlier historical events.

The same information specialists performed searches from April 25 to 28, 2021 in the following databases: PsycInfo, Ovid Medline ALL, Embase, PTSDpubs, SSRN, Sociological Abstracts, JPR, Berman, Rambi, NARCIS, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. Additionally, the gray literature was searched to identify possible relevant PhD theses for inclusion in this scoping review (Paez, 2017). The source of the gray literature search was OpenGrey.eu.

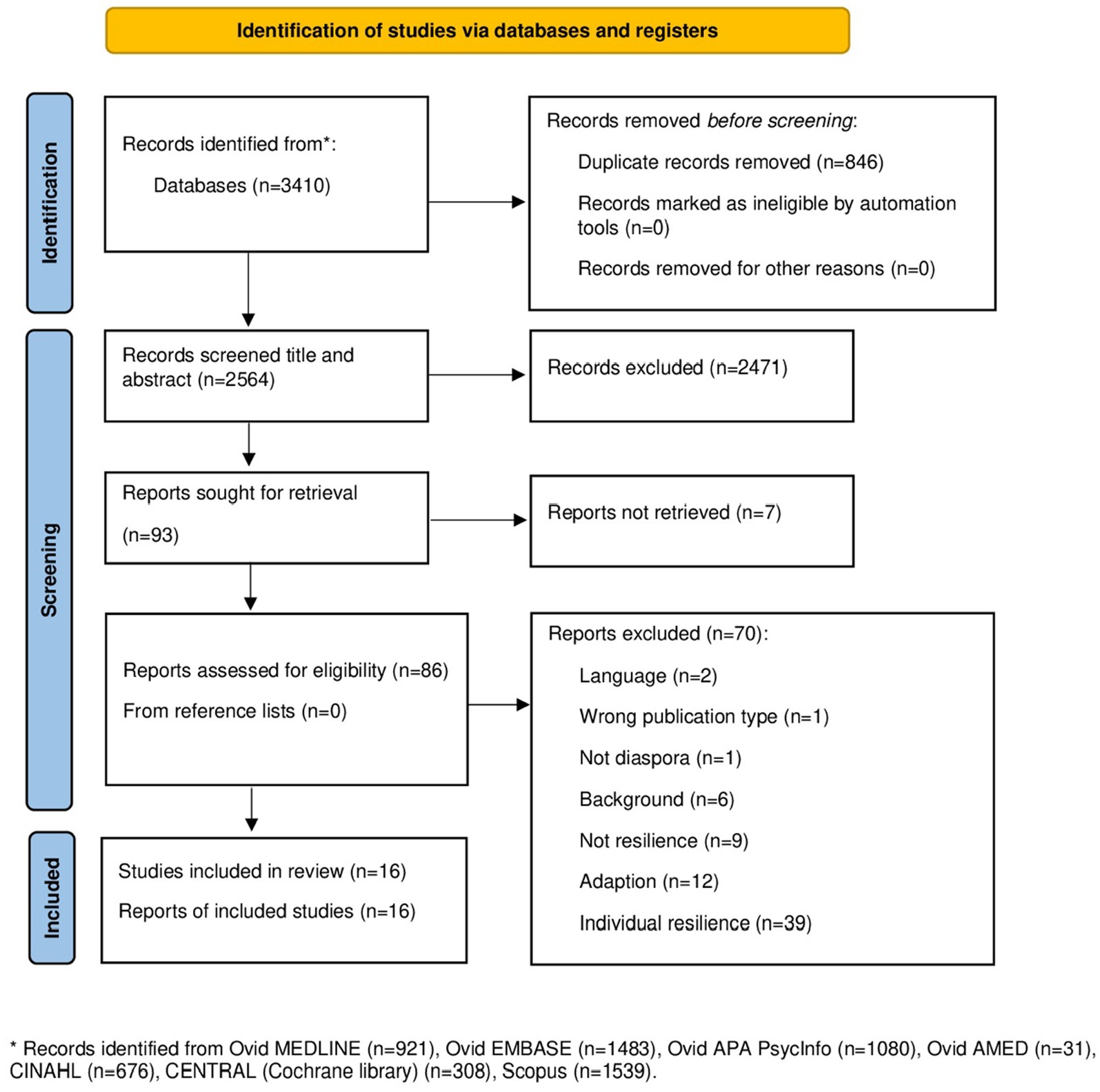

Following the literature search, all identified records and citation abstracts were collated and uploaded into the review web tool Rayyan to facilitate the study selection and data extraction process. Duplicates were removed. Each step in the scoping review process (screening, study inclusion, data extraction etc) was performed independently by at least two authors. The search results and decisions regarding inclusion/exclusion were recorded in Rayyan and are reported in the Prisma-ScR flow diagram (Tricco et al., 2018).

2.8. Data extraction

A pilot data extraction of two articles (Azoulay and Sanchez, 2000; Chalew, 2007) was carried out in Rayyan. After piloting, the authors extracted and assessed the data in relation to the scoping review questions. Accordingly, two items were added to the data extraction form (Supplementary File 3).

2.9. Collating and summarizing the results

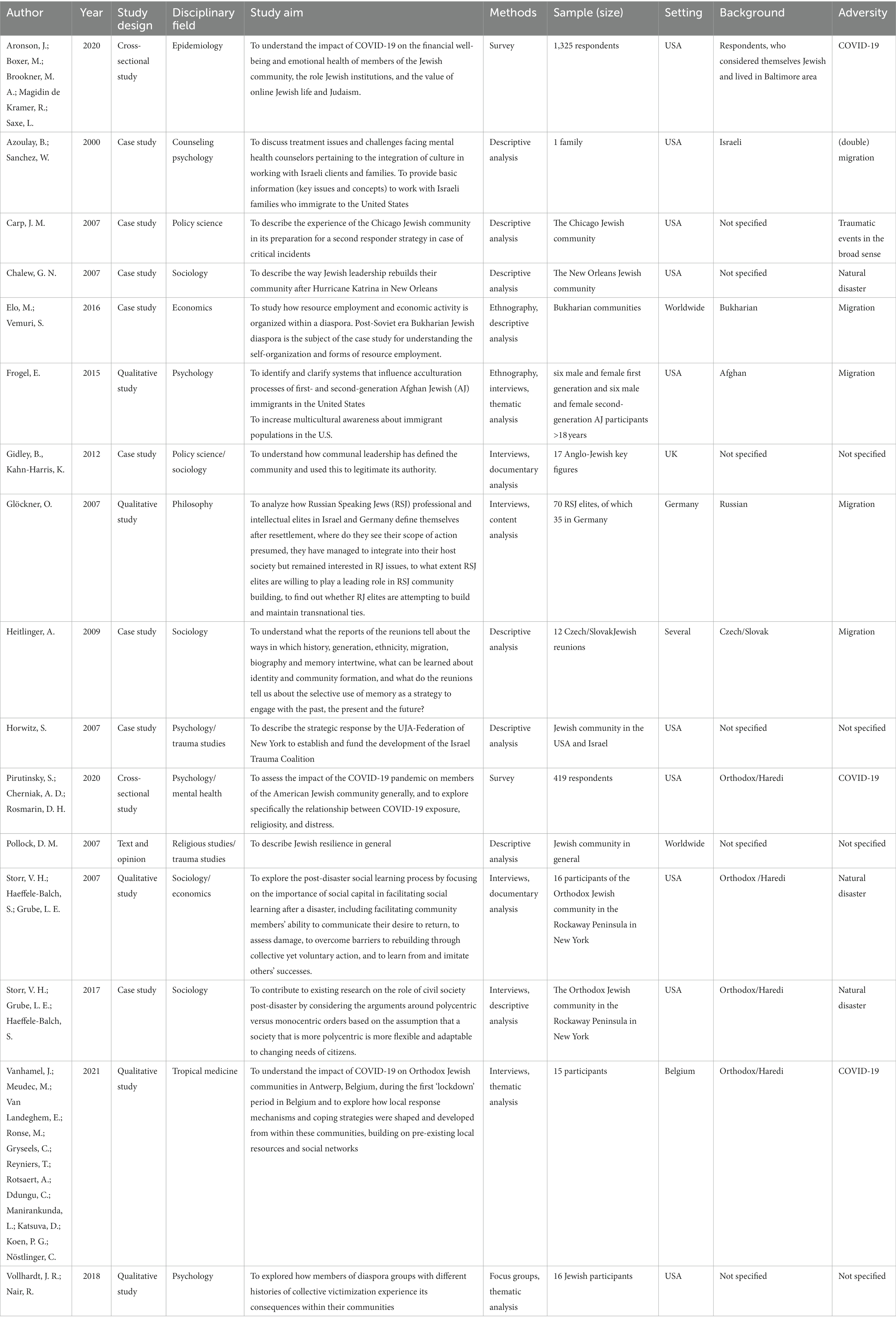

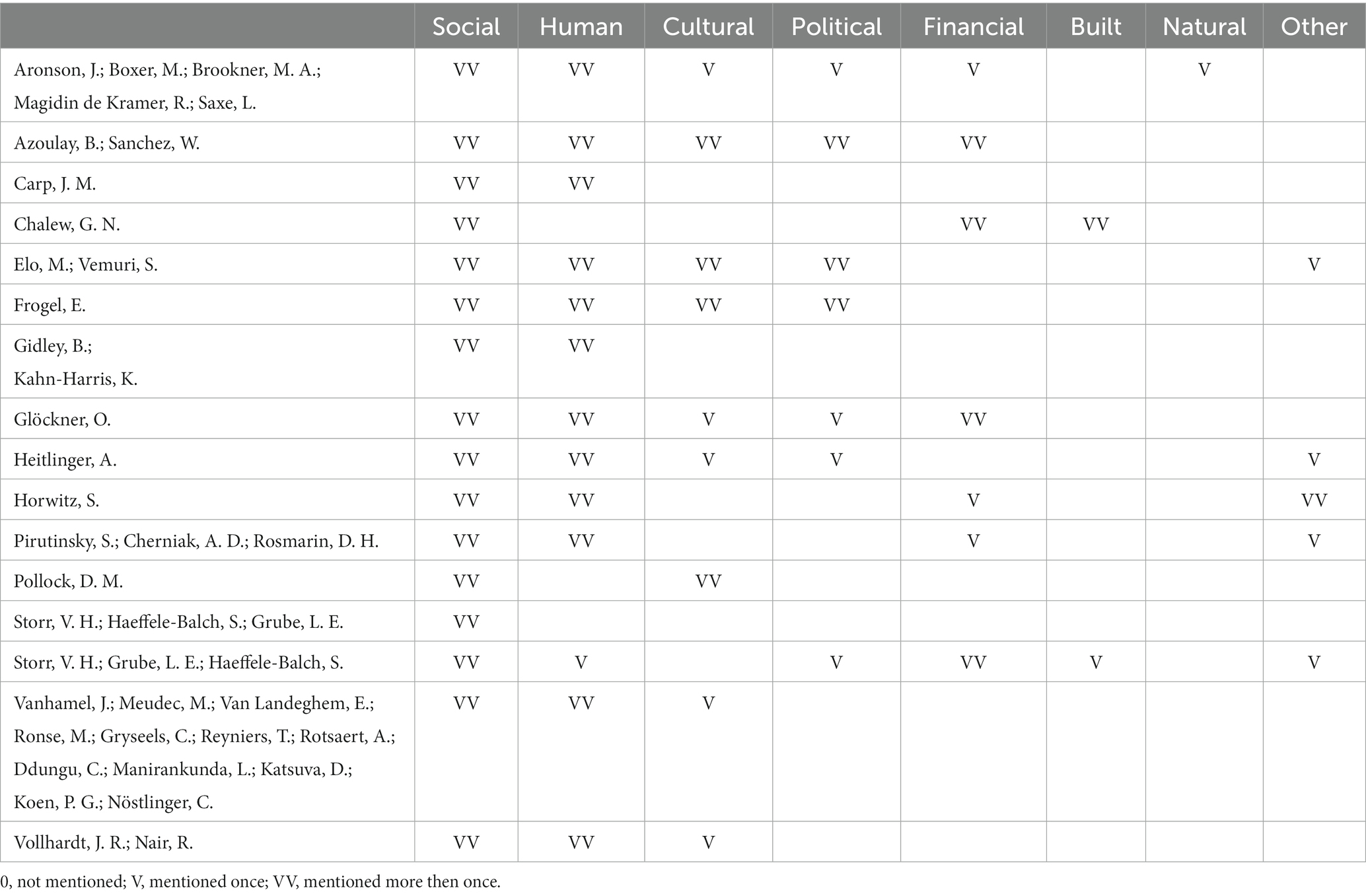

All authors were involved in the process of data synthesis and interpretation. A summary table with detailed information about every included article was provided (see Table 1).

2.10. Patient and public involvement

The first author was employed by the Dutch Jewish Welfare Organization from 2017 to 2021. Furthermore, the review questions of this scoping review were actively discussed and refined with input from three experts within the international Jewish community.

2.11. Deviations from the protocol

In the predefined protocol, it was described that the PAGER methodological framework is used to assist data analyses (Meijer et al., 2022). However, due to the large variety in designs, methodologies, populations, and outcomes of the sixteen studies included, it was not feasible to apply this framework. Instead, an inductive analysis in Atlas-ti was conducted to retrieve a thematic categorization of the mentioned positive factors and barriers (Kiger and Varpio, 2020). Next, all positive factors and barriers were deductively analyzed using the elements of Patel et al. (2017) and the seven capitals of the Community Capitals Framework of Flora et al. (2016) in order to gain further insight into the characteristics of the community resilience of the Jewish diaspora.

2.12. Article identification and selection process

The database and gray literature search yielded 2,564 records after deduplication (Figure 1).

Screening of titles and abstracts resulted in a first selection, after which 2,471 records were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the resulting 93 records, seven records were not retrieved, of which six were dissertations. A total of 86 records were therefore assessed for eligibility. After the full-text screening, sixteen articles met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the scoping review.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included articles

A summary of the included articles and their study designs (n = 16) can be found in Table 1. Included articles were methodologically diverse, mostly based on case studies (n = 8). Other types of studies included were qualitative studies (n = 5); cross-sectional studies (n = 2), and text and opinion (n = 1). Nine of the 16 articles were based on empirical research. The research was conducted by a broad diversity of disciplinary fields including amongst others psychology, economics and sociology (see Table 1). The applied empirical methods were interviews (n = 6), surveys (n = 2) and one focus group. Several types of analysis were conducted: descriptive (n = 8), thematic (n = 3) documentation (n = 2), ethnographic (n = 2) and one content analysis. Two records were dissertations. Nine articles originated from the USA, and others were from Europe (n = 3) or reported on diasporic populations in more than one country (n = 4). The articles were either published from 2000 to 2010 (n = 7) or after 2010 (n = 9). In only five out of sixteen studies, the migration background of the Jewish diasporic community was specified.

3.2. Concepts of community resilience, definitions, and underlying theoretical models (review question 1)

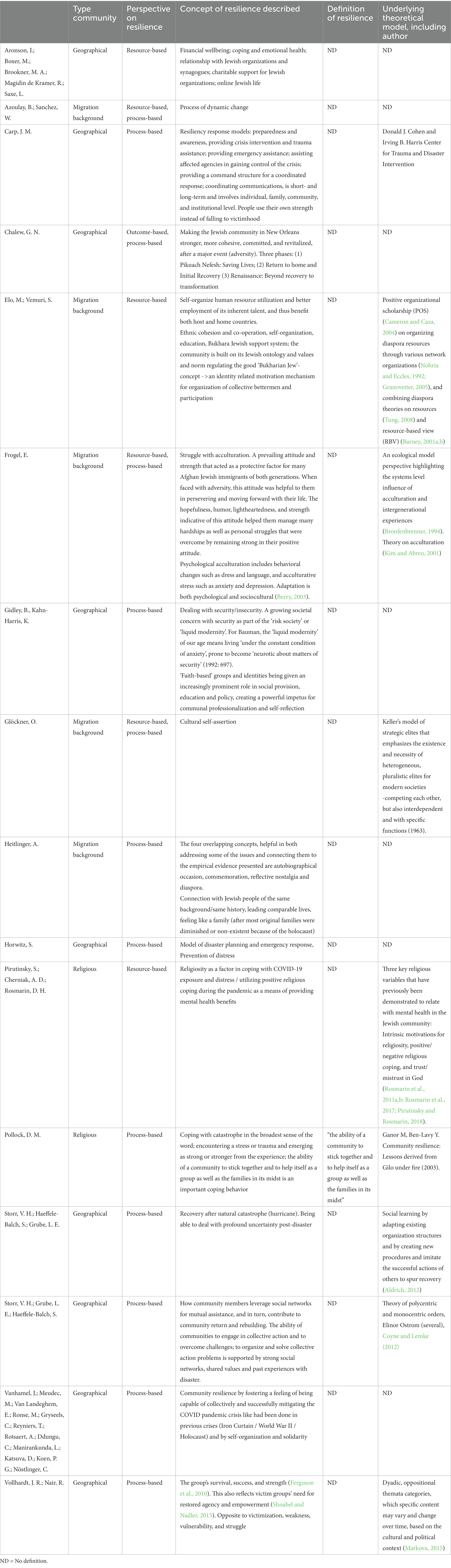

The concepts of community resilience in the included articles are listed in Table 2. The main finding is that the reviewed articles use different definitions of resilience and various underlying theoretical models or frameworks for Jewish diaspora community resilience. In only one of the articles (Pollock, 2007) community resilience was defined as such. Most studies characterized the diasporic Jewish communities by means of a specific geographic location, for example the Antwerp community (n = 9). Other studies characterized the Jewish community based on their migration background, for example Russian Jewish migrants (n = 5). In two studies, the Jewish community was characterized by religious affiliation, in both cases as Orthodox communities. Furthermore, resilience was used as a concept close to other related concepts, such as coping, mitigation, survival, or recovery.

The reviewed literature was categorized according to the three previously reported perspectives on resilience, resource-based (Tengblad and Oudhuis, 2018), outcome-based and process-based (Infurna and Luthar, 2018; Wiles et al., 2019). In most of the articles, resilience was defined from a process-based perspective (n = 9), in six articles the resource-based perspective was leading, and the outcome-based perspective was identified in one article (Chalew, 2007). Chalew, describing the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, also applies a process-based perspective as he distinguished three phases after the disaster: (1) saving lives (pikuach nefesh), (2) return to home and initial recovery, and (3) renaissance beyond recovery to transformation. Three articles (Glöckner, 2010; Frogel, 2015) combined a resource-based perspective with a process-based perspective. Even though these authors defined resilience as resource-based, all three articles describe processes of communities dealing with adversities.

3.3. Traumatic events or causes of stress described (review question 2)

The answer to review question 2 is listed in Table 1. The forms of adversity that were most studied were natural disasters, such as a flood (n = 3) and the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 3). Other adversities in the studies were (un)voluntary migration (n = 5) and five articles did not specify the adversity. Furthermore, eight of the sixteen articles (Carp, 2007; Heitlinger, 2009; Glöckner, 2010; Gidley and Kahn-Harris, 2012; Frogel, 2015; Vollhardt and Nair, 2018; Pirutinsky et al., 2020; Vanhamel et al., 2021) mentioned antisemitism as one of the adversities influencing the quality of life of the members of diasporic Jewish communities.

3.4. Factors facilitating community resilience (review question 3)

The inductive qualitative analysis identified that social and religious factors, strong organizations, and the role of education and communication were facilitating factors for community resilience. All articles describe the importance of good social networks within the community. Next, several articles mention the role of religion as a social factor to strengthen community resilience, and in the sense of a spiritual source of individual resilience. A good education was seen as a facilitator on an individual level, but Jewish educational institutions can also strengthen the community. Communication is important in dealing with adversity. Both articles about COVID-19 stress the role of the community in communication about the developments around the pandemic. This included digital and face-to-face communication, both within the community and from government institutions with community leaders (Aronson et al., 2020; Vanhamel et al., 2021). Elo and Vemuri (2016), Frogel (2015), and Pollock (2007) mentioned specific cultural narratives of resilience, grounded in the Jewish value system, norms, and identity, suggesting that these contribute to the willingness of Jews to invest in their community and the survival of Jewish diaspora communities. An active role in the community is rewarded by bringing societal status, respect, and satisfaction from the community to the individual (Elo and Jokela, 2014).

3.5. Barriers to community resilience (review question 4)

The qualitative analysis identified the following barriers to community resilience: The interaction with the hosting country and other communities, characteristics of the community itself, and psychological and cultural issues. Examples of the first group of barriers are legislation of the hosting country, antisemitism, and connection with Israel. An example of a characteristic of the community itself is the size of the community. Being a small community was considered by two authors as a disadvantage (Frogel, 2015; Elo and Vemuri, 2016). Examples of psychological issues were the impact of the Holocaust and a loss of identity. Cultural issues were different values between generations about family values or gender issues. Several authors also mentioned a language barrier that made it difficult to connect with sources outside the community or communicate between generations.

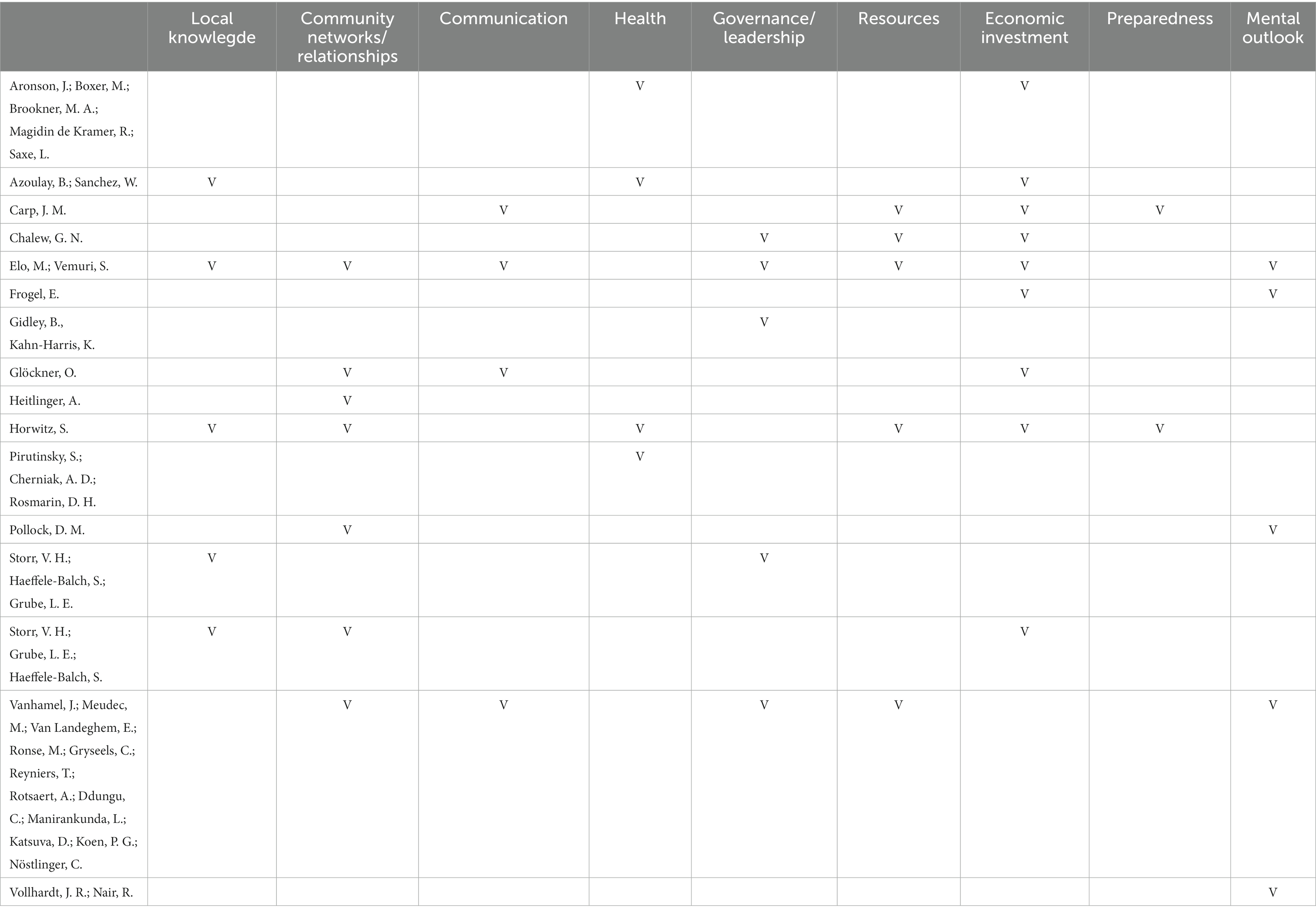

3.6. Comparing categorizations of community resilience

As a next step to gain further insight into the specific characteristics of the community resilience of the Jewish diaspora, all facilitators and barriers described in the included articles were deductively analyzed according to the elements of Patel et al. (2017). All articles included in this review described factors that fall in at least one of the nine main elements: local knowledge, community networks and relationships, communication, health, governance and leadership, resources, economic investment, preparedness, and mental outlook (Table 3). Furthermore, all main elements of Patel et al. were attributed more than once. The element ‘health’ was only found concerning mental health. The majority of studies on the resilience of the Jewish diaspora community described facilitators and barriers in the ‘economic investment,’ ‘social networks and relationships’ element.

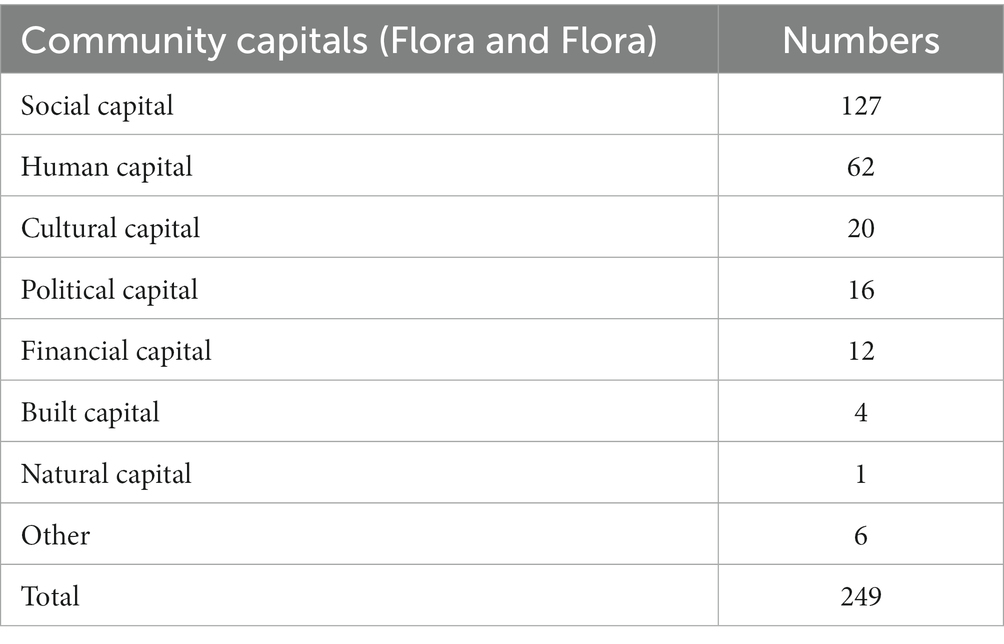

A second framework was used for the further analysis of the community resilience characteristics of the Jewish diaspora, the seven categories of the Community Capital Framework of Flora et al. (2016) (Table 4). All retrieved facilitators and barriers in the sixteen included articles were analyzed using Atlas-ti. A total of 249 quotations were created, and all quotations were coded with one or more of the seven capitals of Flora and Flora. An eighth code was added by the researcher, called ‘Other.’ In all articles, social capital was nominated more than once, human capital was nominated in 13 out of 16 articles, cultural capital in 9 articles, and political and financial capital were both mentioned in 7 articles. Built capital was nominated in two articles and nature in one. In 5 articles characteristics were mentioned that were categorized as ‘other.’ The division of the total quotations is shown in Table 5.

As shown in Table 5, the most frequently mentioned positive factor in the reviewed articles was related to social capital. Many social factors were mentioned by more than one author, such as the role of the family, marriage, friendship and the community, the role of other Jewish communities, the hosting country, the country they left, or Israel. Factors related to human capital were also mentioned often, such as language skills or psychological issues. The importance of the ‘sense of belonging’ was mentioned several times. Cultural and political factors came in third and fourth place. Financial factors were mentioned both on an individual level – the risk that people’s incomes drop after adversity – and on a community level – thus the need for funding after a disaster. Factors relating to the built capital were only mentioned four times, always related to a disaster, and natural capital was mentioned only once, indirectly related to people and their interests during COVID-19. The code ‘other’ was applied for two types of factors: several quotations regarding the availability of technology and the internet for information and social connection, and one for the factor ‘time’ (Elo and Vemuri, 2016). A few authors claim there is a direct relationship between one of the factors and people’s involvement in a resilient community. Glöckner (2010) cites Cohen stating that ‘increasing economic security in private life normally correlates with a growing commitment in the local Jewish community.’

It was observed that the articles on natural disasters refer more often to the material categories, except for one article by Storr that deals specifically with social capital (Storr et al., 2016). Articles dealing with more continuous adversities tend to focus on the immaterial categories. Some authors (Pollock, 2007; Frogel, 2015; Elo and Vemuri, 2016) suggest that Jewish diaspora communities tend to be more resilient due to specific factors, such as Jewish values or being part of a religious community and are thus more capable to deal with adversities.

Previously, it has been suggested that culture and changing environments due to migration and living in the diaspora may significantly impact resilience (Ungar, 2008). Two studies that have reported on the resilience of Jewish communities in the USA involve the way they respond to disasters, specifically, Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy (Chalew, 2007; Storr et al., 2017). Storr et al. (2017) found that privately organized social service providers within the community that joined to coordinate their actions were a key factor in the recovery of the Jewish community in New York after Hurricane Sandy. Chalew (2007) described the rise of a cohesive, committed, and revitalized Jewish community two years after Hurricane Katrina. The key factors for this transformation were found to be the financial generosity of the American Jewish community as a whole and the community leaders who acted to build a new future for the community after the disaster. A recently published study that reported on the importance of the community for the resilience of its members investigated the response of the Antwerp Jewish communities to the COVID-19 pandemic (Vanhamel et al., 2021). In this study, the importance of engaging communities and religious leaders in risk communication and local decision-making was significant in dealing with pandemic control measures and the impact of COVID-19.

3.7. Methods to measure community resilience (review question 5)

The resilience of the Jewish diasporic communities was mainly investigated and narratively described by qualitative methods: (semi-structured) interviews, focus groups, case studies, (field) observations, or an analysis of data from historical, ethnographic, and strategic documents. None of the articles included quantitatively measured community resilience. One article by Aronson et al. (2020) surveyed aspects of individual resilience and indicated the level of involvement in a Jewish community.

3.8. The relationship between community resilience and the health-related quality of life of individuals (review question 6)

Flora et al. (2016) expect that the capitals support sustainability, consisting of a healthy ecosystem, social inclusion, and economic security, which in turn form the quality of life (Vaneeckhaute et al., 2017). None of the articles referred explicitly to the concept of quality of life, in relationship with the resilience of the community, nor used measuring methods and outcomes regarding the quality of life of members of the community.

3.9. Key gaps in the literature on community resilience (review question 7)

The findings of this scoping review reveal several key gaps in the literature on the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities. No univocal definition was found, nor methods to measure community resilience, nor was there elaboration on what community resilience meant for the quality of life of individuals.

Only a few articles were based on theoretical modeling or a framework, and just one author (Pollock, 2007) refers to a theoretical model of community resilience developed by Ganor and Ben-Lavy (2003). Even though nine articles were based on empirical research methods, only one study applied triangulation (Vanhamel et al., 2021), no mixed-methods research was conducted, and, in most studies, the number of participants was small. The majority of studies focused on one type of adversity, a disaster or COVID-19, whereby a more overall perspective of resilience was lacking.

3.10. Ethical issues or challenges studying community resilience (review question 8)

Two authors questioned their role as researchers, one because the researcher was not part of the studied community (Vanhamel et al., 2021), or – on the contrary – because the researcher was part of the studied community (Frogel, 2015). Vanhamel et al. (2021) mentioned that due to his position as a researcher from outside the community he was not able to explore in more depth some social and cultural issues within the Jewish community toward the Belgian government and community. Frogel (2015) wonders if it might have influenced the interviews but indicates mostly positive aspects of her being part of the community. Vollhardt and Nair (2018) report the possibility of socially desirable answers due to group dynamics within the focus groups. They also describe the way they prepared and debriefed the respondents, given the sensitive nature of the topic.

As Jewish identity is not synonymous with the Jewish religion, there are many forms of Jewish identity. The issue of different and variable self-identifications was found in the study on the Afghan Jewish community (Elo and Vemuri, 2016) and the article of Azoulay (Azoulay and Sanchez, 2000). The study of Gidley and Kahn-Harris (2012) also mentions that the Anglo-Jewish community is an entity in motion. Instead, they use the terms “messy, contingent, fluid, evolving and contested” (p. 183, Gidley and Kahn-Harris, 2012) to describe the Jewish diaspora community. Gidley and Kahn-Harris point out another ethical challenge that relates to the neutrality of the researcher. According to them, Jewish leadership has used the existence of antisemitism to regain leadership. The wording they use by describing this reveals a judgment on the behavior of Jewish leadership doing so.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this scoping review is the first comprehensive systematic review focusing on community resilience in the Jewish diaspora community. This review found sixteen studies targeting the concepts of the resilience of the Jewish communities in the diaspora and identified several key factors affecting the resilience of these communities.

4.1. Discussion of major findings in relation to existing literature

The present scoping review reveals that community resilience is mostly described in terms of coping with disaster or struggling with acculturation of the Jewish diaspora. Most articles described concepts that were closely related to resilience, such as adaptation, acculturation, or coping, as were the concepts of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While these concepts highlight the individuals’ reactions to impactful events, the concept of resilience can be applied to both individual and community responses to such events. A clear definition of community resilience of the Jewish diaspora as such, thus seems to be lacking in the literature. Only one article defined the concept of community resilience and associated it with the theoretical model of Ganor and Ben-Lavy (2003) and Pollock (2007).

In the present scoping review we found that in most studies (n = 9) the Jewish diaspora communities were characterized as a place-based community (Chalew, 2007; Storr et al., 2016, 2017). Place-based communities are communities of people who are bound together because of where they reside, work, visit or otherwise spend a continuous portion of their time (Gieryn, 2000). This finding is well in line with other studies on community resilience that mainly involved place-based communities (Kulig et al., 2013; Flora et al., 2016; Vaneeckhaute et al., 2017). The other studies included in this review characterized the Jewish diaspora communities by the country of origin of the members, or by religious affiliation. It thus appears from this scoping review that the Jewish diaspora communities world-wide differ from one another regarding their specific geographic location, migration history and religious affiliation. It is well-known from the literature that the migration history of Jews, especially in Europe, is ancient (Blom et al., 2021) and that in many countries, the Jewish diaspora communities are prosperous in the socioeconomic sense (Wallerstein and Duran, 2010). In contrast to this, we were reminded in the present study that Jewish diaspora communities have been established in the last decennia (Elo and Vemuri, 2016) or consist of members with a more marginalized position (Glöckner, 2010). Jewish diaspora communities appear to have some characteristics which make them different from most studied diaspora communities; they have variously been considered a race, an ethnic group, members of a religion, or a culture. These characteristics lay the foundation of an ongoing scientific debate on the question if Jews can be considered an ethnic minority. However, a comparison of the results of this scoping review with those of Patel et al. (2017) and Flora et al. (2016) suggest that many notions of community resilience are also applicable to the studies on Jewish diaspora communities.

Another important finding of this scoping review is that all three perspectives on resilience – resource-based, outcome-based, and process-based – are found in the research on Jewish diaspora communities world-wide. The process-based perspective appears to be the most common perspective on resilience of Jewish communities living in the diaspora. This finding is in line with the results of Patel et al. (2017), who also demonstrated that the process-based perspective was adopted in most recent studies on resilience of other (non-Jewish) communities. This could be explained by the fact that the context of Jewish diaspora communities worldwide varies substantially, and that this impacts their resilience resources. As both the resources and the adversities can vary, also the outcomes vary. Therefore, research from a process-based perspective appears to be the most relevant when searching for generalizable ways to strengthen the resilience of Jewish diaspora communities.

In the general literature on community resilience, numerous studies and policy documents address the distinct phases communities go through when dealing with adversities and distinguish four phases of dealing with a disaster: preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery (Maguire and Hagan, 2007; FEMA, 2019). In this scoping review comparable phases were identified in articles that describe the aftermath of a natural disaster (Chalew, 2007; Storr et al., 2016, 2017) and in the policy-oriented articles (Carp, 2007; Horwitz, 2007; Pollock, 2007).

Through this scoping review, we identified that social factors and networks are strong positive influencing factors for the resilience of Jewish diaspora communities. These enablers of community resilience have also been reported by others. Based on interviews with Australian rural community members, Buikstra et al. (2010) reported the presence of social networks and support as a critical factor for community resilience. Faulkner et al. (2018) conducted an empirical review of five interrelated characteristics of community resilience, of which one was community networks. They reported that the residents of two different coastal communities in the UK perceived these characteristics in different combinations of importance for enabling resilience. It was concluded that context is important, that context consists of many factors which are interconnected [e.g., past experiences with crisis events, and that strengthening any one factor in isolation from others will probably not lead to enhanced levels of community resilience (Faulkner et al., 2018)]. Based on a group of survivors of an earthquake in China, Wei et al. (2022) reported recently that social capital is the most consistent and positive predictor of perceived community resilience. Liu analyzed the impact of social networks on community resilience in Tianjin (China) and pointed to social trust as a core element, as trust affects the willingness to be involved in communities’ activities and networks (Liu et al., 2022).

The influencing factors for community resilience that were identified in this scoping review were categorized and analyzed using the list of the nine main elements of Patel et al. (2017) and the seven capitals of the Community Capital Framework of Flora et al. (2016). Both classifications are referred to in many studies and have contributed to the understanding of community resilience. They are based on different perspectives on adversities, one-time disasters, and ongoing stress, respectively. The classifications partly overlap, and partly highlight different elements. Further research is needed to find out how these classifications exactly relate to each other. In addition, it is important to highlight that in our analysis we identified two other influencing factors ‘time’ and ‘technology and internet,’ that could not be classified in any of the categories of Flora and Flora. Patel et al. (2017) mentions technology and social media as a sub-category of the element ‘communication.’ Adding the factors ‘time’ and ‘technology and internet’ as separate categories to the classifications might thus be relevant for an overall contemporary perspective on community resilience.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

4.2.1. Strengths

A rigorous and systematic methodology was applied in the present scoping review. The search strategy was adapted as broadly as possible in databases without controlled vocabularies to obtain the maximum search yield. In addition to the database searches, gray literature was searched. Furthermore, two independent researchers screened and included all articles. Another strength of this review is that it was conducted by a multidisciplinary team with researchers from different backgrounds including public health, philosophy, psychiatry, and psychology. The fact that the research questions were intensively discussed with three members of Dutch and Israeli Jewish communities can also be considered a strength of this study.

4.2.2. Limitations

Although 32% of the Jews currently living in Israel are migrants, many Jews worldwide consider Israel as their home country and regard the Jewish community in Israel as the dominant community and not a diaspora community. Because we specifically aimed to explore the characteristics of the Jewish diasporic community outside their home country, where they are a minority, a considerable number of studies on communities in Israel were thus excluded from this scoping review. Some of these excluded Israeli studies (Leykin et al., 2013; Kimhi, 2016; Leykin et al., 2016; Shapira, 2022; Weinberg and Kimchy Elimellech, 2022) may have been relevant for the Jewish diaspora communities. Kimhi, for example, studied the association between individual, community and national resilience and found significant positive but low correlations between community and individual resilience (R = 0.160). Based on that, Kimhi assumes that each resilience level stands for an independent construction, but both predict individual well-being and successful coping with potentially traumatic events (Kimhi, 2016). Shapira and Leykin conducted some of the few longitudinal studies on community resilience in Israeli communities in response to several adversities. Shapira focused on how perceived community resilience levels change over time and while dealing with different hazards (Shapira, 2022). They concluded that throughout the study period, place attachment, collective efficacy, and preparedness were the strongest contributors to community resilience, while trust in local leadership and social trust were the weakest. Shapira’s study also confirms the notion that different adversities impact psychological demands on exposed populations differently, and in turn, affect coping strategies and resiliency. Leykin and Cohen developed the Conjoint Community Resiliency Assessment Measure (CCRAM), a validated instrument to measure community resilience (Cohen et al., 2013; Leykin et al., 2013). Leykin compared community resilience during emergency and routine situations using the CCRAM and confirmed that during an emergency, higher resilience trends will emerge (Leykin et al., 2016). Only one of the five community resilience factors, social trust, stayed constant over time. Weinberg examined the effect of spirituality and perceived community resilience on PTSD and stress of first responders and showed that spirituality, age, and financial situation were negatively associated with PTSD symptoms and stress. However, perceived community resilience was not associated with PTSD symptoms or stress (Weinberg and Kimchy Elimellech, 2022). Summarizing, these insights and instruments are relevant and can contribute to understanding the resilience of Jewish diaspora communities. Another limitation of the present scoping review is that the majority of the reviewed articles were on Jewish diaspora communities living in the United States of America (USA). Therefore, results need to be interpreted with caution and cannot be extrapolated to Jewish diaspora communities worldwide. More research is needed in other countries, specifically because the exploration of the role of history, culture, religion, ethnicity, and antisemitism in and outside the USA may be critical in understanding community resilience and the impact on the individual resilience and health of their members. Lastly, as community resilience is not a well-defined concept (Kulig et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2017), it was sometimes up to the personal understanding and interpretation of the authors of this scoping review whether the article dealt with community resilience of the Jewish diaspora. For this reason, some relevant articles or concepts may have been missed.

4.3. Recommendation for practice and further research

As mentioned in the introduction, most Jews worldwide live in the diaspora (The Jewish Agency for Israel, 2022). There are constant migrant movements of Jews, sometimes as refugees, due to wars or antisemitism, and sometimes as regular migrants looking for a better life. One of the most recent Jewish migrant movements is the migration from Ukraine (McKernan and Kierszenbaum, 2022; Schut, 2022). Because of the constant migrant movements, Jewish diaspora communities are very diversified. Jewish history is a rich history of constantly investing in and (re-)building their communities. Recently, several programs have been developed (Gidron, 2019; Baker, 2020) aiming to strengthen Jewish community resilience within and outside Israel. Our findings in the present scoping review on facilitators and barriers for community resilience are therefore of relevance for these programs and the future support and development of Jewish diaspora communities.

Key gaps in the literature that were identified in this scoping review are that studies on community resilience of Jewish diaspora communities focused on a single crisis only and that none of the included studies applied assessment measures. In addition, no study looked at the association between individual and community resilience, nor described how community resilience affects the health-related quality of life of individuals in this diasporic population. The WHO Health Evidence Network conducted a review of methods to measure health-related community resilience (South et al., 2018) in which different research methods to assess community resilience were evaluated. This study concluded that health-related community resilience is a complex, multidimensional concept. Therefore, research methods should collect data from multiple domains, prioritize social and economic indicators and intersectoral cooperation, combine quantitative and qualitative data or apply a mixed-methods research strategy (South et al., 2018). Infurna and Luthar (2018) and Infurna and Jayawickreme (2019) also show that resilience is a multidimensional construct and expresses the need for a more comprehensive theory and a thorough multidimensional research approach.

Research on community resilience can broadly be divided into two approaches. The first approach studies the collective resilience of communities, whereas the second approach studies the individual resilience of people in communities. Van der Schoor (2020, unpublished, see footnote 1) concluded that hardly any research has been conducted on the interactions between these perspectives. Further research on the lived experiences of members of Jewish diaspora communities can contribute to the understanding of these interactions. Pearson and Geronimus (2011) found that the self-rated health of Jewish Americans was significantly worse than that of other White Americans, and access to co-ethnic social ties was associated with better self-rated health among Jews. None of the reviewed articles in the present study mentioned any relationship between the resilience of Jewish diasporic communities and the health-related quality of life of individuals belonging to the community. In her study on Afghan Jews and their children, Fogel distinguishes eight themes and relates them to the ecological model of Bronfenbrenner (Frogel, 2015). However, she does not analyze the dynamics between these levels. This gap needs further research.

For a better understanding of social support, generally considered to be one of the main contributors to individual resilience, it is recommended that future studies reporting on community resilience focus on the interactions between Jewish diaspora communities and their members, and other diaspora communities.

4.4. Conclusion

Social and religious factors, strong organizations, education, and communication were identified as facilitating factors that increase community resilience. The social factors mentioned were marriage, the family and other social networks, and a sense of belonging and social connections. Religious factors were religious traditions, identity and coping and the role of religious gatherings. The interaction with the hosting country and other communities, characteristics of the community itself, and psychological and cultural issues were specified barriers to the resilience of Jewish communities in the diaspora. The effect of antisemitism in the hosting country as a barrier was mentioned in half of the articles. Community characteristics were its small size and or a lack of unity and dividedness.

The results of this study contribute to a better understanding of the meaning of community resilience and the facilitating factors and barriers for Jewish diasporic communities and their members. Research examining the relevance and importance of resilience in the context of diaspora communities is still lacking. A better understanding of the resilience of Jewish diaspora communities can contribute to strengthen the resilience of Jewish and other diaspora communities. Thus, further research on Jewish communities can help Jewish and other diasporic communities, their leaders, policymakers and supporting organizations to strengthen the resilience of these communities and their members to deal with future traumatic stress.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JM, AM, GS, and MJ: conceptualization and formal analysis. JM, WS, and MJ: data curation. WS and JL: searches. JM and MJ: screening and inclusion. JM and WS: data extraction. JM: project administration and writing – original draft. MJ: validation. MJ, AM, GS, and JM: writing – review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jonna Lind for critically reading the scoping review protocol to develop the search strategy, and Anne-Vicky Carlier and Sam Johnson for their support in searching the selected databases and retrieving the relevant documents. The authors thank David Gidron, Bart Wallet, and Hanna Luden for providing critical feedback and input to the review questions of this scoping review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1215404/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Van der Schoor, Y. (2020). The impact of local resources on CR. Unpublished.

References

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: social capital in post-disaster recovery. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Alefaio-Tugia, S., Afeaki-Mafile’o, E., and Satele, P. (2019). “Pacific-Indigenous community-village resilience in disasters” in Pacific social work. eds. J. Ravulo, T. Mafile'o, and D. B. Yeates. 1st ed (London: Routledge), 68–78.

Aromataris, E., and Munn, Z.,, and Joanna Briggs Institute (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide, Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute.

Aronson, J., Boxer, M., Brookner, M. A., Magidin De Kramer, R., and Saxe, L. (2020). Building resilient jewish communities: baltimore key findings building resilient jewish communities: a jewish response to the coronavirus crisis Brandeis: Waltham.

Azoulay, B., and Sanchez, W. (2000). Israeli families immigration and intercultural issues: challenges to mental health counselors. J. Cult. Divers. 7, 89–98.

Baker, L. (2020). In the UK, learning how to build jewish community resilience. Available at: https://www.jdc.org/voice/leeds-jewish-community-resilience/

Barney, J. B. (2001a). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 26, 41–56. doi: 10.5465/amr.2001.4011938

Barney, J. B. (2001b). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: a ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 27, 643–650. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00115-5

Berry, J. W. (2003). “Conceptual approaches to acculturation” in Acculturation: advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. eds. P. Balls Organista, G. Marín and K. M. Chun (Washington: American Psychological Association), 17–37.

Blom, H., Wertheim, D., Berg, H., and Wallet, B. (2021). Reappraising the history of the jews in the netherlands. 2nd Edn The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience. Am. Psychol. 59, 20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Bonanno, G. A., Romero, S. A., and Klein, S. I. (2015). The temporal elements of psychological resilience: an integrative framework for the study of individuals, families, and communities. Psychol. Inq. 26, 139–169. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.992677

Bronfenbrenner, U., Arastah, J., Hetherington, M., Lerner, R., Mortimer, J. T., Pleck, J. H., et al. (1986). Developmental psychology ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives Dev. Psychol. 22, 723–742.

Buikstra, E., Ross, H., King, C. A., Baker, P. G., Hegney, D., McLachlan, K., et al. (2010). The components of resilience-perceptions of an Australian rural community. J. Community Psychol. 38, 975–991. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20409

Cameron, K. S., and Caza, A. (2004). Introduction contributions to the discipline of positive organizational scholarship. Am. Behav. Sci. (Beverly Hills), 47, 731–739. doi: 10.1177/0002764203260207

Capra, F., and Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carp, J. M. (2007). The road to resilience: building a Jewish community trauma response plan. J. Jewish Commun. Serv. 83, 5–21.

Chalew, G. N. (2007). A community revitalized, a city rediscovered: the new orleans jewish community two years post-katrina. J. Jew. Communal Serv. 83, 84–87.

Cohen, O., Leykin, D., Lahad, M., Goldberg, A., and Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2013). The conjoint community resiliency assessment measure as a baseline for profiling and predicting community resilience for emergencies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 80, 1732–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.12.009

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., et al. (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Coyne, C. J., and Lemke, J. (2012). Lessons from the cultural and political economy of recovery. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 71, 215–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.2011.00821.x

Dellapergola, S., and Staetsky, L. D. (2020). Jews in Europe at the turn of the millennium population trends and estimates.London: Institute of Jewish Policy Research.

Derakhshan, S., Blackwood, L., Habets, M., Effgen, J. F., and Cutter, S. L. (2022). Prisoners of scale: downscaling community resilience measurements for enhanced use. Sustainability 14:6927. doi: 10.3390/su14116927

Diamond, S., Ronel, N., and Shrira, A. (2020). From a world of threat to a world at which to wonder: self-transcendent emotions through the creative experience of holocaust survivor artists. Psychol. Trauma 12, 609–618. doi: 10.1037/tra0000590

Duckers, M., Hoof, W., Jacobs, J., and Holsappel, J. (2017). Het belang van een veerkrachtige gemeenschap: gezondheidsbevordering bij flitsrampen en ‘creeping crises’. Impact Magazine, nr. 4: 12–15.

Elo, M., and Jokela, P. (2014). “Social ties, bukharian jewish diaspora and entrepreneurship: narratives from entrepreneurs” in New perspectives in diasporic experience (Oxford, United Kingdom: Inter-Disciplinary Press), 141–155.

Elo, M., and Vemuri, S. (2016). Organizing mobility: a case study of Bukharian Jewish diaspora. C. Rapoo, M. L. Coelho and Z. Sarwar (Leiden: Brill).

Faulkner, L., Brown, K., and Quinn, T. (2018). Analyzing community resilience as an emergent property of dynamic social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 23:24. doi: 10.5751/ES-09784-230124

Ferguson, N., Burgess, M., and Hollywood, I. (2010). Who are the victims? Victimhood experiences in postagreement Northern Ireland. Polit. Psychol. 31, 857–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00791.x

Fischer, A., and McKee, A. (2017). A question of capacities? Community resilience and empowerment between assets, abilities and relationships. J. Rural. Stud. 54, 187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.06.020

Flora, C. B., Flora, J. L., and Gasteyer, S. P. (2016). Rural communities: legacy+ change. 4th Edn New York. Routledge.

Ganor, M., and Ben-Lavy, Y. (2003). Community resilience: lessons derived from Gilo under fire. J. Jewish Commun. Ser. 79, 105–108.

Gidley, B., and Kahn-Harris, K. (2012). Contemporary anglo-jewish community leadership: coping with multiculturalism. Br. J. Sociol. 63, 168–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2011.01398.x

Gieryn, T. F. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 463–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.463

Glöckner, O . (2010). Immigrated Russian Jewish elites in Israel and Germany after 1990: their integration, self image and role in community building. Available at: http://opus.kobv.de/ubp/volltexte/2011/5036/

Granovetter, M. (2005). The impact of social structure on economic outcomes. J. Econ. Perspect., 19, 33–50. doi: 10.1257/0895330053147958

Heitlinger, A. (2009). From 1960s' youth activism to post-communist reunions: generational community among Czech and Slovak Jewry. East Eur. Jewish Affairs 39, 265–288. doi: 10.1080/13501670903016357

Hobfoll, S. E., Watson, P., Bell, C. C., Bryant, R. A., Brymer, M. J., Friedman, M. J., et al. (2007). Five essential elements of immediate and mid–term mass trauma intervention: empirical evidence. Psychiatry 70, 283–315. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283

Horwitz, S. (2007). Trauma response, recovery, planning, and preparedness. J. Jewish Commun. Serv. 83, 32–38. doi: 10.4337/9781849806541.00011

Huber, M. A. S. (2014). Towards a new, dynamic concept of health: its operationalisation and use in public health and healthcare and in evaluating health effects of food. Available at: https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl:publications%2F506e3a0d-e5ec-4ee2-8604-59f317d2724a

Infurna, F. J., and Jayawickreme, E. (2019). Fixing the growth illusion: new directions for research in resilience and posttraumatic growth. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 28, 152–158. doi: 10.1177/0963721419827017

Infurna, F. J., and Luthar, S. S. (2018). Re-evaluating the notion that resilience is commonplace: a review and distillation of directions for future research, practice, and policy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 65, 43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.003

Institute for Jewish Policy Research . (2015). European Jewish Population Sizes 2014. Available at: http://www.jpr.org.uk/documents/European_Jewish_Population_Sizes.2014.pdf

Jong, M. C., Lown, E. A., Schats, W., Mills, M. L., Otto, H. R., Gabrielsen, L. E., et al. (2021). A scoping review to map the concept, content, and outcome of wilderness programs for childhood cancer survivors. PLoS One 16:e0243908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243908

Keysar, A. (2014). From Jerusalem to New York: researching jewish erosion and resilience. Contemp. Jew. 34, 147–162. doi: 10.1007/s12397-014-9118-x

Kidron, C. A. (2012). Alterity and the particular limits of universalism comparing jewish-israeli holocaust and canadian-cambodian genocide legacies. Curr. Anthropol. 53, 723–754. doi: 10.1086/668449

Kiger, M. E., and Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Kim, B. S. K., and Abreu, J. M. (2001). “Acculturation measurement theory - current instruments, and future directions” in Handbook of multicultural counseling. eds. J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casa, L. Suzuki, and C. M. Alexander. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 394–424.

Kimhi, S. (2016). Levels of resilience: associations among individual, community, and national resilience. J. Health Psychol. 21, 164–170. doi: 10.1177/1359105314524009

Kulig, J. C., Edge, D. S., Townshend, I., Lightfoot, N., and Reimer, W. (2013). Community resilience: emerging theoretical insights. J. Community Psychol. 41, 758–775. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21569

Landau, J. (2007). Enhancing resilience: families and communities as agents for change. Fam. Process 46, 351–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00216.x

Leykin, D., Lahad, M., Cohen, O., Goldberg, A., and Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2013). Conjoint community resiliency assessment measure-28/10 items (CCRAM28 and CCRAM10): a self-report tool for assessing community resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 52, 313–323. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9596-0

Leykin, D., Lahad, M., Cohen, R., Goldberg, A., and Aharonson-Daniel, L. (2016). The dynamics of community resilience between routine and emergency situations. Boston: Elsevier BV.

Liu, Y., Cao, L., Yang, D., and Anderson, B. C. (2022). How social capital influences community resilience management development. Environ. Sci. Policy 136, 642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2022.07.028

Lurie, I. (2017). Sleep disorders among holocaust survivors: a review of selected publications. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 205, 665–671. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000717

Maguire, B., and Hagan, P. (2007). Disasters and communities: understanding social resilience. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 22, 16–20. doi: 10.3316/agispt.20072385

Markova, I. (2015). On thematic concepts and methodological (epistemological) themata. Pap. Soc. Rep. 24, 4.1–4.31.

Mayunga, J. S. (2009). Measuring the measure: a multi-dimensional scale model to measure community disaster resilience in the U.S. Gulf Coast region Available at: http://www.pqdtcn.com/thesisDetails/75D8F779B5A8FF7AB91913E1D737CFE9

McKernan, B., and Kierszenbaum, Q. (2022). It’s driven by fear’: Ukrainians and Russians with Jewish roots flee to Israel; a new wave of Ukrainian Jews and around one in eight Russian Jews has 'made aliyah', or emigrated, to Israel. The Observer

Meijer, J. E. M., Machielse, A., Smid, G. E., and Jong, M. C. (2022). Mapping the concept and factors affecting the resilience of Jewish communities living in the diaspora: a scoping review protocol. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361250262_Mapping_the_concept_and_factors_affecting_the_resilience_of_Jewish_communities_living_in_the_diaspora_A_scoping_review_protocol

Nohria, N., and Eccles, R. (1992). Networks and organizations : structure, form, and action. Harvard Business School Press.

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., and Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Paez, A. (2017). Gray literature: an important resource in systematic reviews. J. Evid. Based Med. 10, 233–240. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12266

Patel, S. S., Rogers, M. B., Amlôt, R., and Rubin, G. J. (2017). What do we mean by “community resilience”? A systematic literature review of how it is defined in the literature. PLoS Curr. 9. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.db775aff25efc5ac4f0660ad9c9f7db2

Pearson, J. A., and Geronimus, A. T. (2011). Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics, coethnic social ties, and health: evidence from the national jewish population survey. Am. J. Public Health 101, 1314–1321. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190462

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., et al. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 18, 2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., et al. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 19, 3–10. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277

Pfefferbaum, B., Pfefferbaum, R. L., and Van Horn, R. L. (2015). Community resilience interventions. Am. Behav. Sci. 59, 238–253. doi: 10.1177/0002764214550298

Pirutinsky, S., Cherniak, A. D., and Rosmarin, D. H. (2020). COVID-19, mental health, and religious coping among american orthodox jews. J. Relig. Health 59, 2288–2301. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z

Pirutinsky, S., and Rosmarin, D. H. (2018). Protective and harmful effects of religious practice on depression among jewish individuals with mood disorders. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 6, 601–609. doi: 10.1177/2167702617748402

Pollock, D. M. (2007). Therefore choose life: the Jewish perspective on coping with catastrophe. Southern Med. J. 100, 948–949. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318145aae0

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Auerbach, R. P., Björgvinsson, T., Bigda-Peyton, J., Andersson, G., et al. (2011a). Incorporating spiritual beliefs into a cognitive model of worry. J. Clin. Psychol. 67, 691–700. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20798

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Carp, S., Appel, M., and Kor, A. (2017). Religious coping across a spectrum of religious involvement among jews. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 9, S96–S104. doi: 10.1037/rel0000114

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., and Pargament, K. I. (2011b). A brief measure of core religious beliefs for use in psychiatric settings. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 41, 253–261. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.3.d

Schut, B . (2022). In Oekraine dreigt een nieuwe exodus. NIW. Available at: https://niw.nl/in-oekraine-dreigt-een-nieuwe-exodus/

Scott, K. M., Koenen, K. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Benjet, C., et al. (2013). Associations between lifetime traumatic events and subsequent chronic physical conditions: a cross-national, cross-sectional study. PLoS One 8:e80573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080573

Shapira, S. (2022). Trajectories of community resilience over a multi-crisis period: a repeated cross-sectional study among small rural communities in Southern Israel. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 76:103006. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103006

Shnabel, N., and Nadler, A. (2015). The role of agency and morality in reconciliation processes: the perspective of the needs-based model. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 24, 477–483. doi: 10.1177/0963721415601625

Smid, G. E., Drogendijk, A. N., Knipscheer, J. W., Boelen, P. A., and Kleber, R. J. (2018). Loss of loved ones or home due to a disaster: effects over time on distress in immigrant ethnic minorities. Transcult. Psychiatry 55, 648–668. doi: 10.1177/1363461518784355

South, J., Jones, R., Stansfield, J., and Bagnall, A. (2018). What quantitative and qualitative methods have been developed to measure health-related community resilience at a national and local level? WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/5540/

Stein, A. (2009). Trauma and origins: post-holocaust genealogists and the work of memory. Qual. Sociol. 32, 293–309. doi: 10.1007/s11133-009-9131-7

Storr, V., Grube, L. E., and Haeffele-Balch, S. (2017). Polycentric orders and post-disaster recovery: a case study of one Orthodox Jewish community following Hurricane Sandy. J. Inst. Econ. 13, 875–897. doi: 10.1017/S1744137417000054

Storr, V., Haeffele-Balch, S., and Grube, L. E. (2016). Social capital and social learning after Hurricane Sandy. Rev. Austrian Econ. 30, 447–467. doi: 10.1007/s11138-016-0362-z

Tengblad, S., and Oudhuis, M. (2018). The resilience framework: organizing for sustained viability. Singapore: Springer.

The Jewish Agency for Israel (2022). Global Jewish population rises to 15.3 million with 7 million in Israel. Arutz Sheva/Israel National News

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Tung, R. L. (2008). Brain circulation, diaspora, and international competitiveness. Eur. Manag. J., 26, 298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2008.03.005

Ungar, M. (2008). Resilience across cultures. Br. J. Soc. Work 38, 218–235. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcl343

Ungar, M. (2011). The social ecology of resilience: addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 81, 1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x

Van der Schoor, Y., Duyndam, J., Witte, T., and Machielse, A. (2021). What's important to me is to get people moving.' Fostering social resilience in people with severe debt problems. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 25, 592–604. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2021.1997930

Vaneeckhaute, V., Jacquet, A., and Meurs, P. (2017). Community resilience 2.0: toward a comprehensive conception of community-level resilience. London: Informa UK Limited.

Vanhamel, J., Meudec, M., Van Landeghem, E., Ronse, M., Gryseels, C., Reyniers, T., et al. (2021). Understanding how communities respond to COVID-19: experiences from the Orthodox Jewish communities of Antwerp city. Int. J. Equity Health 20, 1–78. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01417-2

Van Solinge, H., and de Vries, M. H. (2001). De joden in Nederland anno 2000. Demografisch profiel en binding aan het jodendom. Uitgeverij Aksant.

Van Solinge, H., van Praag, C. S., van der Gaag, N. L., and van de Wardt, M. (2010). De Joden in Nederland anno 2009: continuïteit en verandering AMB. Diemen.

Verbena, S., Rochira, A., and Mannarini, T. (2021). Community resilience and the acculturation expectations of the receiving community. J. Commun. Psychol. 49, 390–405. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22466

Vollhardt, J. R., and Nair, R. (2018). The two‐sided nature of individual and intragroup experiences in the aftermath of collective victimization: findings from four diaspora groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 412–432. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2341

Wallerstein, N., and Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 100, S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036

Wei, J., Han, Z., Han, Y., and Gong, Z. (2022). What do you mean by community resilience? More assets or better prepared? Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 16, 706–713. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.466

Weinberg, M., and Kimchy Elimellech, A. (2022). Civilian military security coordinators coping with frequent traumatic events: spirituality, community resilience, and emotional distress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8826. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148826

Wiles, J., Miskelly, P., Stewart, O., Kerse, N., Rolleston, A., and Gott, M. (2019). Challenged but not threatened: managing health in advanced age. Soc. Sci. Med. 227, 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.018

Keywords: adaption, adversity, community resilience, diaspora, Jewish community, migration

Citation: Meijer JEM, Machielse A, Smid GE, Schats W and Jong MC (2023) The resilience of Jewish communities living in the diaspora: a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 14:1215404. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1215404

Edited by:

Monica Pivetti, University of Bergamo, ItalyReviewed by:

Cristina O. Mosso, University of Turin, ItalyBruria Adini, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Copyright © 2023 Meijer, Machielse, Smid, Schats and Jong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Judith E. M. Meijer, anVkaXRoLm1laWplckBwaGQudXZoLm5s

†ORCID: Judith E. M. Meijer https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4385-0852

Judith E. M. Meijer

Judith E. M. Meijer Anja Machielse

Anja Machielse Geert E. Smid

Geert E. Smid Winnie Schats

Winnie Schats Miek C. Jong4,5

Miek C. Jong4,5