94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Psychol., 29 September 2023

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1194767

This article is part of the Research TopicPromoting Patient and Caregiver Engagement in Chronic Disease ManagementView all 8 articles

Giada Rapelli1*

Giada Rapelli1* Emanuele Maria Giusti2

Emanuele Maria Giusti2 Claudia Tarquinio3

Claudia Tarquinio3 Giorgia Varallo4

Giorgia Varallo4 Christian Franceschini1

Christian Franceschini1 Alessandro Musetti5

Alessandro Musetti5 Alessandra Gorini6,7

Alessandra Gorini6,7 Gianluca Castelnuovo3,8

Gianluca Castelnuovo3,8 Giada Pietrabissa3,8*

Giada Pietrabissa3,8*Objective: This scoping review aims to provide an accessible summary of available evidence on the efficacy of psychological couple-based interventions among patients with heart disease and their partners focusing on specific aspects and strategies by assessing different emotional and physical cardiac-related outcome measures.

Methods: A literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases using the keywords “heart diseases” and “couple-based intervention.” A literature search using systematic methods was applied. Data were extracted to address the review aims and were presented as a narrative synthesis.

Results: The database search produced 11 studies. Psychological couple-based interventions varied in terms of the type of intervention, personnel, format (group or individual, phone or in person), number of sessions, and duration. Most of the contributions also lacked adequate details on the training of professionals, the contents of the interventions, and the theoretical models on which they were based. Finally, although partners were involved in all the treatment, in most studies, the psychological strategies and outcomes were focused on the patient.

Conclusion: The variability of the psychological couple-based interventions of included studies represents a challenge in summarizing the existing literature. Regarding their impact, psychological interventions for patients with cardiovascular disease and their partners were found to moderately improve patients’ and partners’ outcomes.

Having a heart disease redefines oneself as ill, modifies one’s significant bonds, and requires constant lifestyle changes according to the disease progression (Roger et al., 2020). Furthermore, the management of heart disease is complex and requires constant monitoring of symptoms over time. For this reason, if present, the partner plays an important role by providing both practical and emotional support (Bertoni et al., 2015; Donato et al., 2020). Since romantic relationships play a significant role in people’s lives (Bertoni et al., 2015), it is important to investigate the role of the partner in either helping or hindering the patient’s psychological adjustment to heart disease over the course of the medical treatment.

The role of the partner in cardiovascular disease is central from the acute to the chronic phase of the illness, commonly faced at home (Rapelli et al., 2022). During hospitalization, the presence of a supportive partner can make a difference in terms of the patient’s recovery and psychological wellbeing. By supporting patients’ self-efficacy (Maeda et al., 2013; Rapelli et al., 2022), partners might increase their ability to self-care (George-Levi et al., 2016; Rapelli et al., 2021) even in complex medical situations when an implantable device like the left ventricular assist device is needed (LVAD; Golan et al., 2023; Rapelli et al., 2023). In addition, partners might help to reduce patients’ symptoms of depression and/or anxiety (Sokoreli et al., 2016; Bouchard et al., 2019; Rapelli et al., 2021) or monitor their compliance to complex pharmaceutical therapies, make appointments for follow-ups and accompany the patient to the visits, detect signs of cardiac symptomatology, and be the primary person responsible for the patient’s hyposodic diet (Randall et al., 2009; Rapelli et al., 2020a).

A supportive partner also motivates and helps the patient adopt healthier lifestyle habits–thus reducing cardiovascular risk factors (Maeda et al., 2013; Rapelli et al., 2022) and rates of participation in cardiac rehabilitation programs (Rankin-Esquer et al., 2000).

Conversely, not all forms of support are helpful (Breuer et al., 2017). Indeed, studies have shown that social support may be split into positive and negative forms. Cardiac patients have been the subject of substantial research on positive support, defined as interactions that foster affection (Sebri et al., 2021). On the other hand, scholars paid less attention to negative support, or when the beneficiary of support regards it as unhelpful or feels social limitations by others (Breuer et al., 2017). In fact, patients who feel poorly emotionally supported experience a 41% higher risk of non-compliance with the treatment than those who feel supported by their partner (Leifheit-Limson et al., 2012). Furthermore, perceiving the partner as hostile or overprotective could hinder the patients’ motivation or become a barrier to behavioral changes, thus affecting their health (Fiske et al., 1991; Rapelli et al., 2020b; Bertoni et al., 2022).

Still, partners are not immune to the sense of emptiness and lack of control commonly caused by the disease (Rapelli et al., 2020a), and providing support may be a very stressful and demanding experience for informal caregivers, i.e., those who provide unpaid care to their loved ones (Randall et al., 2009; Bertoni et al., 2015; Rapelli et al., 2020a).

Healthy spouses might present high levels of distress (Randall et al., 2009; Bertoni et al., 2015; Rapelli et al., 2020a) and post-traumatic stress symptoms (Vilchinsky et al., 2017; Fait et al., 2018). Furthermore, partners may refer to absent relational and sexual satisfaction (Bouchard et al., 2019) and perceived low positive dyadic coping, which represents a risk factor for the provision of inadequate support (Rapelli et al., 2021). In addition, it has been speculated that the ability of the spouses of patients with heart disease to be supportive decreases over time, while critical and controlling behaviors increase (Stephens et al., 2006; Rapelli et al., 2022) in the presence of caregiver burden (Luttik et al., 2007).

Since coping with cardiac problems represents, therefore, a dyadic experience rather than proper of the patients (e.g., Rapelli et al., 2021, 2022, 2023; Golan and Vilchinsky, 2023), there is a growing demand for couple-based interventions for heart disease that focus not only on the patients but also on their partners.

For these reasons, this scoping review aims to provide an overview of available evidence on couple-based psychological interventions for coping with heart disease involving both patient and partner by answering the following research questions: (1) What are the main characteristics in terms of the theoretical model, provider, and format of intervention? (2) Which psychological strategies are specifically used in the intervention? (3) Which scoping review outcomes are measured in the short- and long-term?

In the present study, the results of a scoping review focused on couple-based interventions for patients with heart diseases and their partners are shown. Data extraction, critical appraisal, and qualitative synthesis were in line with established systematic review and qualitative synthesis methods (Khan et al., 2003).

Searches were conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science from November to December 2022.

The search strategies combined key terms and Medical Search Headings (MESH) terms based on the PICO (Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes) framework as follows: (“CVD” OR “Cardiovascular disease” OR “Cardiac”) AND (“Couple” OR “Dyad” OR “Partner” OR “Caregiver”) AND (“Couple-based intervention” OR “Couple therapy” OR “Couple program”) (Huang et al., 2006). Boolean and truncation operators were used to systematically combine more searched terms and list documents containing variations on search terms, respectively. The search syntax was modified as appropriate for each database.

Only original articles that (1) employed couple-based interventions involving both patients and partners; (2) were published in English, (3) examined the impact of couple-based interventions on patients with heart disease and their partners were included. Records were excluded if they (1) considered only biomedical outcome variables, (2) were review articles, single-case studies, mixed-method studies, protocol studies, workplace interventions, theses, or internal reports of gray literature, (3) involved only the patient or their family members as caregivers (e.g., parents, siblings, cousins, etc.). Unpublished works were not considered. No restrictions were set for the date of publication and type of study design.

Following the search and exclusion of duplicates, two reviewers (authors GR and CT) independently assessed the eligibility of the articles first on the title and the abstract, and the full text according to the inclusion criteria. Author 3 (CT) resolved disagreements. Following Smith et al. (2011) recommendation, the review team included two people with methodological expertise in conducting systematic reviews (EG and GP) and at least two experts on the topic under review (GR and CT). The reference lists of all selected articles and relevant systematic reviews were manually screened to identify any further references for possible inclusion–but none was found.

A search of electronic databases identified 222 reports, of which 165 were excluded based on information from the title and abstract after removing duplicates. The remaining 23 articles were evaluated for inclusion by reviewing their full text, which resulted in the exclusion of 11 records. The flowchart presented in Figure 1 provides step-by-step details of the study selection.

Two authors (GR and CT) independently extracted the following data from the included studies: (1) first author and year of publication, (2) country, (3) study aim, (4) study design, (5) sample, (6) measures, (7) characteristics of the intervention, (8) primary outcomes, (9) secondary outcomes, (10) setting, (11) provider, (12) duration of the intervention, (13) follow-up point(s), (14) theoretical approach, (15) intervention approach and format, (16) control group, (17) main findings.

They discussed any discrepancies, and, if necessary, consulted a third author (EG) to reach a final decision (Table 1). Extracted data were collated to produce a narrative summary of couple-based interventions for cardiac patients and their partners. Furthermore, to report all characteristics of studies and interventions the CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 checklist (Consort10; Schulz et al., 2010) and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist (TIDieR; Hoffmann et al., 2014) were used.

The studies included in this review are described in Table 1.

The selected articles were published from Dracup et al. (1984) to Tulloch et al. (2021), and were conducted in the USA (Dracup et al., 1984; Gortner et al., 1988; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Daugherty et al., 2002; Sher et al., 2014), Denmark (Dinesen et al., 2019), Canada (Stewart et al., 2001; Hartford et al., 2002; Tulloch et al., 2021), Scotland (Johnston et al., 1999), and Great Britain (Thompson, 1989). Three studies employed a qualitative method (Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Dinesen et al., 2019), and six studies employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design (Gortner et al., 1988; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Hartford et al., 2002; Sher et al., 2014). In the study by Tulloch et al. (2021), a pre-post-study design was employed.

Selected contributions included a total of 665 patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 602 partners of both genders. The sample size varied from a minimum of 14 patients and 12 partners (Dinesen et al., 2019) to a maximum of 72 patients and their partners (Hartford et al., 2002) across studies. The mean age was 58.62 years for the patients and 57.40 years for the partners involved in these 8 studies (Dracup et al., 1984; Gortner et al., 1988; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Stewart et al., 2001; Hartford et al., 2002; Dinesen et al., 2019; Tulloch et al., 2021). Three studies did not report patients’ and partners’ ages (Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Daugherty et al., 2002; Sher et al., 2014). In 8 studies, patients suffered from acute or chronic cardiac illness (Dracup et al., 1984; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Sher et al., 2014; Dinesen et al., 2019; Tulloch et al., 2021), while three records included cardiac surgery patients (Gortner et al., 1988; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Hartford et al., 2002).

The main characteristics of the interventions were extensively reported in Supplementary material 1 using the CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 checklist (Consort10; Schulz et al., 2010) and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist (TIDieR; Hoffmann et al., 2014), and were summarized in Table 2.

In all the selected studies, the treatment aimed at providing heart disease-related information to both patients and their informal caregivers–with the main aim to address treatment expectations, and ambivalence toward behavioral change, as well as to define goals and increase the patient-partner dyad’s adherence to treatment recommendations.

The intervention was delivered through regular in-person focus group meetings in 6 out of 11 studies (Dracup et al., 1984; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Sher et al., 2014; Tulloch et al., 2021). The number of intervention sessions ranged from one (Daugherty et al., 2002) to 18 (Sher et al., 2014). In particular, in the study by Daugherty et al. (2002) the intervention group (IG) consisted in talking about the benefits of social support and of the importance of making lifestyle changes together as partners to modify ineffective behaviors (i.e., criticism and overprotection) using discussion and role-playing. In the study by Dracup et al. (1984), the impact of 10 individual sessions with patients only was compared with a couple-based intervention of equal length. In both IGs, a counseling program on problem-solving was delivered.

In the study by Lenz and Perkins (2000), only partners participated in the focus groups, alternated by telephone sessions. In the study by Sher et al. (2014), couples-assisted focus training groups on behavioral change were provided. In the study by Stewart et al. (2001) patients and partners support group interventions were delivered. In the study by Tulloch et al. (2021), patients and partners participated in an in-person group focused on disease management.

Four interventions out of 11 (Gortner et al., 1988; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Hartford et al., 2002) were in-person individual/(couple) education programs followed by weekly telephone support sessions provided by nurses for 7 (Hartford et al., 2002) or 8 weeks (Gortner et al., 1988). The number of in-person sessions ranged from one (Gortner et al., 1988) to 6 (Hartford et al., 2002). Specifically, the intervention delivered in the study by Gortner et al. (1988) focused on promoting self-efficacy, emotional distress, increased physical activity, and adherence to diet among patients. In the study by Hartford et al. (2002) the intervention consisted of information and support to assist patients and partners in meeting their needs. Johnston et al. (1999) compared 2 types of interventions: inpatient (IG1) vs. inpatient plus outpatients (IG2) counseling for stress management. One intervention was conducted online (Dinesen et al., 2019) and focused on self-management, physical activity, nutritional counseling, and adherence to medications, besides providing psychosocial support.

Only 2 out of the 11 contributions detailed the psychological strategies employed in the intervention (Stewart et al., 2001; Tulloch et al., 2021). In particular, in the study by Stewart et al. (2001) the topics changed weekly based on experienced common stressors. Group discussions were enriched by varied techniques and resources depending on the topic (e.g., case study scenarios focused on a couple coping with a recent myocardial infarction (MI), role-plays, invited consultant or guest speakers, focus group discussions, guided group exercises–for example, weekly diaries about the perceived importance of a given topic, etc.). In the study by Tulloch et al. (2021), couples were guided through seven conversations in which they learned to communicate their need for connection and reassurance, recognize problematic relationship patterns, and rectify them through a series of structured conversations facilitated by different therapeutic strategies including (a) recognize and name emotional states (known as “symbolization”), (b) engage in direct expressions of vulnerability and need (“enactments”), and (c) respond to clear manifestations of vulnerability and a desire for connection (“empathic attunement through enactment”).

The majority of the psychological interventions were provided by one or more trained nurses in 7 interventions (Dracup et al., 1984; Gortner et al., 1988; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Daugherty et al., 2002; Hartford et al., 2002); while in two studies to lead the intervention was a therapist or clinical psychologists (Sher et al., 2014; Tulloch et al., 2021), and in the study by Dinesen et al. (2019) a nurse and a professional with psychological background. Only in one study (Stewart et al., 2001), professionals from various disciplines all working regularly with persons with cardiac disease and/or community-based client groups, and peer supporters (couples in which one spouse was at least 1-year post-MI) conducted the intervention.

The theoretical background of the intervention varied across the studies. Four studies (Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Hartford et al., 2002) referred to the emotional distress theory (Endler and Parker, 1990). Two studies (Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002) referred to the social support theory (Cobb, 1976; Bloom, 1990) and the self-determination theory of Deci and Ryan (2000), Sher et al. (2014), and Dinesen et al. (2019), respectively. Other theoretical backgrounds informing the delivered interventions were: the social support theory (Cobb, 1976) in the study by Daugherty et al. (2002), the theory of coping (Lazarus, 1974; Folkman, 1984) in Stewart et al.’s (2001) contribution, the community of practice approach (Lave and Wenger, 1991) in the study by Dinesen et al. (2019), the transtheoretical model of behavioral change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 2005) in the contribution of Sher et al. (2014), and the interactionist role theory (Dracup and Meleis, 1982) in Dracup et al.’s (1984) study. Moreover, Gortner et al. (1988) referred to both the self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1986) and the double ABCX Model (McCubbin and Patterson, 2014), while Tulloch et al. (2021) referred to the emotionally focused therapy (EFT; Wiebe and Johnson, 2016; Beasley and Ager, 2019) and the attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969, 1973).

Four studies compared the IG with the treatment-as-usual (TAU) condition (Dracup et al., 1984; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Hartford et al., 2002). Furthermore, educational counseling group or individual sessions focused on increasing awareness of the benefits of a healthy lifestyle were used as controls in three contributions (Gortner et al., 1988; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Sher et al., 2014), while four records did not include any control groups (CGs) (Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Dinesen et al., 2019; Tulloch et al., 2021).

Study duration ranged from 2 months (Hartford et al., 2002; Tulloch et al., 2021) to 18 months (Sher et al., 2014). In three studies the intervention had a total duration of 3 months (Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Stewart et al., 2001; Dinesen et al., 2019), in three studies the intervention had a total duration of 6 months (Dracup et al., 1984; Gortner et al., 1988; Thompson, 1989), and only in one study the intervention had a total duration of 12 months (Johnston et al., 1999).

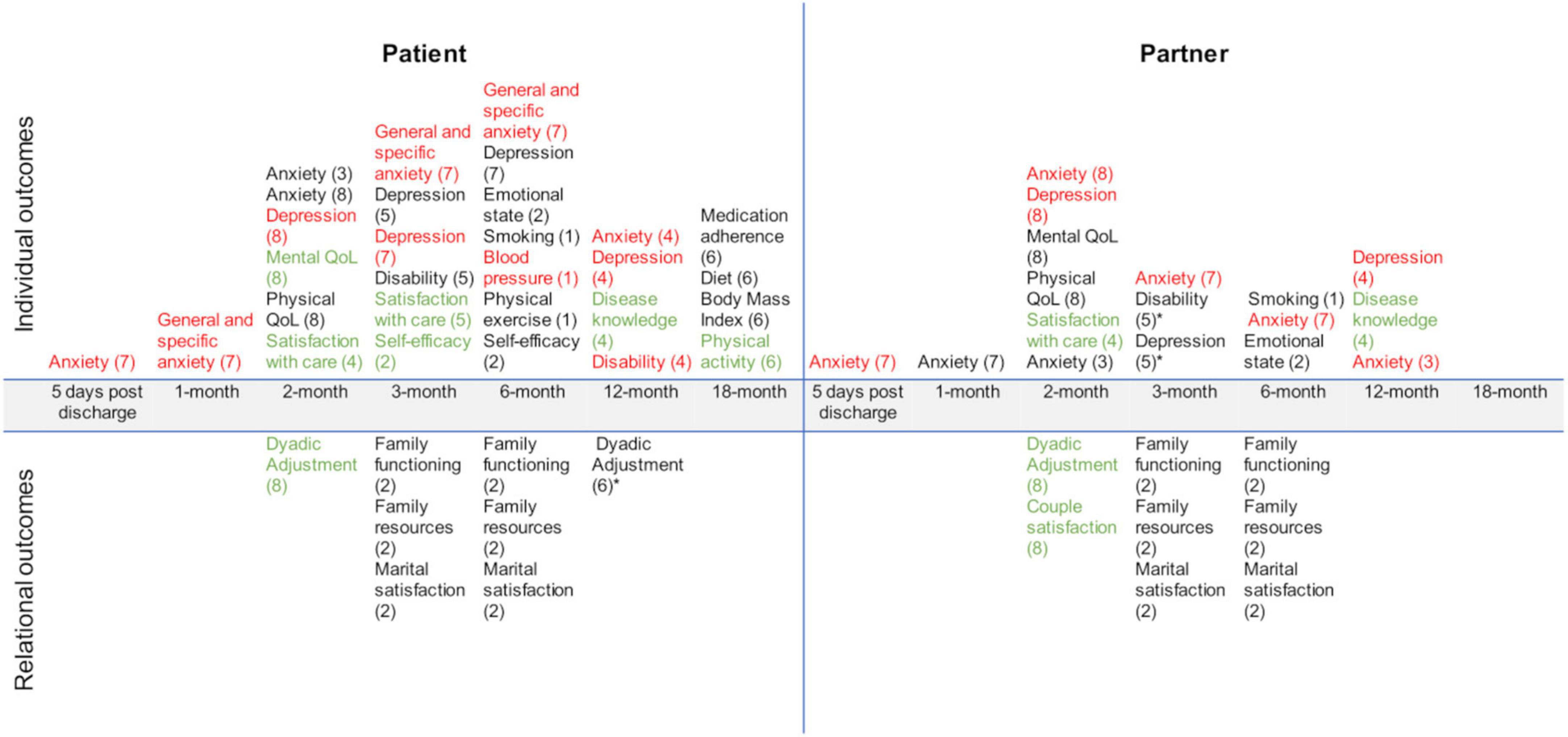

Significant and non-significant effects for both patients and partners are reported in Figure 2. Furthermore, in Supplementary material 2 an extensive summary of the primary and secondary outcomes of the included studies is presented. Briefly, this scoping review showed that couple-based interventions that involved both patients and partners focused on individual outcomes only, relational outcomes only, or both. One out of the 11 selected studies focused on patient individual outcomes only (Sher et al., 2014) not considering partner individual and relational outcomes. Four out of 11 studies focused on patient and partner individual outcomes (Dracup et al., 1984; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Hartford et al., 2002). Three out of 11 studies focused on patient individual and relational outcomes (Gortner et al., 1988; Sher et al., 2014; Tulloch et al., 2021). Two studies out of 11 focused on patient and partner individual and relational outcomes (Gortner et al., 1988; Tulloch et al., 2021).

Figure 2. Primary and secondary outcomes across included studies. 1 = Dracup et al., 1984; 2 = Gortner et al., 1988; 3 = Hartford et al., 2002; 4 = Johnston et al., 1999; 5 = Lenz and Perkins, 2000; 6 = Sher et al., 2014; 7 = Thompson, 1989; 8 = Tulloch et al., 2021. In black the non-significant outcomes; In red the decreased significant outcomes, and in green the increased significant outcomes. *Secondary outcomes.

As shown in Figure 2, the primary outcome is variable across the included studies. Regarding the patient’s primary outcomes: anxiety was measured in 4 studies (Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Hartford et al., 2002; Tulloch et al., 2021), depression was measured in 4 studies (Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Tulloch et al., 2021), disease knowledge was measured in 3 studies (Dracup et al., 1984; Johnston et al., 1999; Sher et al., 2014), physical status was measured in 3 studies (Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Sher et al., 2014), satisfaction with care was measured in 4 studies (Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Daugherty et al., 2002; Dinesen et al., 2019), mood states were measured in one study (Gortner et al., 1988), quality of life was measured in one study (Tulloch et al., 2021), and self-efficacy was measured in one study (Gortner et al., 1988). In 4 out of 11 studies the primary outcome pertained to marital functioning (Gortner et al., 1988; Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Tulloch et al., 2021). In particular, social support was the primary outcome in the qualitative interview studies of Stewart et al. (2001) and Daugherty et al. (2002). In the study by Gortner et al. (1988) family functioning was quantitatively assessed. Last, in one study (Tulloch et al., 2021) the primary outcomes were relationship quality and couple satisfaction.

Regarding the partner’s primary outcomes: anxiety was measured in 4 studies (Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Hartford et al., 2002; Tulloch et al., 2021), satisfaction with care was measured in 3 studies (Johnston et al., 1999; Daugherty et al., 2002; Dinesen et al., 2019), depression was measured in 2 studies (Johnston et al., 1999; Tulloch et al., 2021), mood states were measured in one study (Gortner et al., 1988), quality of life was measured in one study (Tulloch et al., 2021), disease knowledge was measured in one study (Johnston et al., 1999). In 4 studies (Gortner et al., 1988; Stewart et al., 2001; Daugherty et al., 2002; Tulloch et al., 2021) the primary outcome pertained to marital functioning. In particular, social support was the primary outcome in the qualitative interview studies of Stewart et al. (2001) and Daugherty et al. (2002). In the study by Gortner et al. (1988) family functioning was quantitatively assessed. Last, relationship quality and couple satisfaction were measured in the study by Tulloch et al. (2021).

Regarding the secondary outcomes, in the study by Sher et al. (2014) patient marital satisfaction was measured. One study assessed (Lenz and Perkins, 2000) the level of the partner’s physical status. One study assessed (Lenz and Perkins, 2000) the level of partner depression. Both patient and partner satisfaction with care was also assessed in one study (Tulloch et al., 2021).

Results from 5 out of the 11 included studies showed that couple-based interventions were more effective than TAU and/or educational programs in increasing patient outcomes. In particular, self-efficacy at 3-month follow-up (Gortner et al., 1988), disease knowledge at 12-month follow-up (Johnston et al., 1999), physical activity at 18-month follow-up (Sher et al., 2014), satisfaction with care (Johnston et al., 1999; Lenz and Perkins, 2000) at 2- and 3-month follow-ups, respectively. Results from 4 out of the 11 included studies showed that couple-based interventions were more effective than TAU and/or educational programs in decreasing patient anxiety at 5-days from discharge (Thompson, 1989), and at 1- (Thompson, 1989), 3- (Thompson, 1989), 6- (Thompson, 1989), 12-month (Johnston et al., 1999) follow-ups. Furthermore, significant decreases in patient depression at 3-month follow-up (Thompson, 1989), blood pressure at 6-month follow-up (Dracup et al., 1984), and patient-perceived disability at 12-month follow-ups (Johnston et al., 1999) were observed. Regarding the 4 interventions that did not include a CG, only the study by Tulloch et al. (2021) had a quantitative approach and showed a significant increase in the quality of life and dyadic adjustment of the patients, and a significant decrease in their partners’ depression, dyadic adjustment, and couple satisfaction at a 2-month follow-up.

Results from 1 out of the 11 included studies showed that couple-based interventions were more effective than TAU and/or educational programs in increasing partner satisfaction with care at 2-month follow-up (Johnston et al., 1999) and disease knowledge at 12-month follow-up (Johnston et al., 1999). A significant decrease in the partner’s anxiety is observed at 5 days from discharge (Thompson, 1989), 3- (Thompson, 1989), 6- (Thompson, 1989), and 12 months (Hartford et al., 2002) follow-ups.

No significant differences were found for depressive or anxiety symptoms at the 6-month follow-up (Dracup et al., 1984), and for physical exercise level (Sher et al., 2014); there was a significant effect of couple treatment on the increased physical activity and acceleration of treatment over time, but there were no condition effects for adherence to medications and nutritional outcomes.

Notably, significant between-group differences favoring couple-based interventions were mostly observed in the short term, and results were not always maintained over time.

This paper explores the existing literature on couple-based interventions for cardiac patients.

Although evidence increasingly supports the dyadic influence that coping with cardiac illness has on cardiac patients and their partners (Cook and Kenny, 2005), findings reveal that couple-based interventions have received little attention in the literature. Moreover, psychological interventions widely vary in terms of the type of intervention, format (group or individual, phone or in person), number of sessions and duration, and personnel involved across the selected records. In addition, the psychological strategies of the interventions are mostly not comprehensively detailed. This makes it difficult to explore which of them had a specific impact on the dyad’s outcomes and prevent effective studies’ replication. Most of the contributions also lack adequate details on the training of the providers, the contents of the interventions, and the theoretical models on which they were based.

Moreover, we could not assume that couple-based interventions are more or less effective than individual ones, since only 2 out of the 11 studies included in this review (Dracup et al., 1984; Sher et al., 2014) compared a couple-based approach with a patient-only approach.

Regarding the type of intervention, two different types of couple-based interventions can be distinguished. The first class of interventions can be labeled as “partner-assisted”–since the partner acts as the patient’s therapist or coach. These interventions often follow a cognitive-behavioral framework, and require specific tasks to be completed outside the treatment sessions. The treatment plan is supported by the couple’s relationship - but does not focus on it–and does not imply the presence of relational difficulties. This type of couple-based intervention is used in 6 out of the 11 included studies (Dracup et al., 1984; Thompson, 1989; Johnston et al., 1999; Daugherty et al., 2002; Hartford et al., 2002; Dinesen et al., 2019).

A second group of couple interventions–used in 5 out of 11 studies (Gortner et al., 1988; Lenz and Perkins, 2000; Stewart et al., 2001; Sher et al., 2014; Tulloch et al., 2021)–focuses on how a couple interacts in scenarios associated with the individual’s disease. These “disorder-specific” interventions consider the couple’s relationships as a variable potentially affecting either the disorder or the treatment.

No study included in this review implemented couple therapy used with the intent of assisting the individual during the treatment based on the assumption that the functioning of the couple contributes in a broad sense to the development or maintenance of their symptoms.

Overall, couple-based interventions have been shown to have only a modest impact on patients’ outcomes including quality of life, psychological distress, level of physical activity, blood pressure, self-efficacy, disease knowledge, satisfaction with care, and dyadic adjustment.

Partners showed improved perceived psychological distress, disease knowledge, and satisfaction with care; and increased dyadic adjustment scores and couple satisfaction at the relational level.

However, although partners are involved in the treatment, the strategies and the outcomes of the studies are mostly focused on the patient. In fact, as previously mentioned also in other studies (e.g., Rapelli et al., 2022, 2023), it is recommended that relational variables be targeted for interventions.

These findings coupled with those of previous systematic reviews documenting the benefit of couple interventions for patients with chronic diseases (Hartmann et al., 2010; Martire et al., 2010) including cardiac illness (Reid et al., 2013).

However, our results need to be interpreted with caution due to the limitations of the included studies.

This review has some limitations, among them not having considered the assessment of methodological quality, but this limitation is pertinent to the objectives of the scoping review and the heterogeneity of the included studies. Furthermore, it is also worth noting that it was decided to exclude gray literature from the study. This may have affected the validity of the study, but gray literature is not usually subjected to a rigorous review process.

As a strength, we can recognize the use of the TIDieR and Consort10 checklists as useful tools for the replicability of studies since they provide a summary of the proposed interventions with an examination of the limitations and criticalities of the studies themselves. In fact, the present scoping review offers significant information that may guide the design of future research and interventions aimed at improving the efficacy and effectiveness of couple-based interventions for cardiac patients. Specifically, we reported guidelines for research and interventions in the next section.

For future research, given the limitations of the included studies and in order to determine which psychological interventions are most effective, a large, adequately powered, trial assessing psychological interventions for patients alone, compared with psychological interventions for patients and partners, could be recommended. A variety of variables might be investigated, including the timing of the intervention’s start, its intensity, and duration, while also taking into account a clear definition of intervention, its form of delivery, its content, and the type, education, and experience of the therapist. Furthermore, other information lacking in the included studies was the attrition rate and factors related to participation/non-participation. In fact, according to a recent study (Savioni et al., 2022) future psychological interventions may employ ad hoc tools to take into consideration participants’ reasons for non-participation/dropout that often are linked to factors related to intervention commitment and its interference with daily life.

From a clinical point of view, according to the results of this scoping review, more interventions targeted at relational variables are needed. This also means involving the partner in the treatment to increase knowledge of reciprocal needs and activate dyadic resources. The partner would become more aware of the treatment process, more conscious about individual and relational aspects that can influence the patient and the couple’s relationship, and consequently, more involved in the engagement process (Graffigna et al., 2017). Moreover, behavioral modification programs may benefit both the targeted and the non-targeted member of the couple by reducing cardiovascular risk factors in both partners through a virtuous process so one motivates the other since often partners share the same unhealthy diet and inadequate physical activity of patients (Shiffman et al., 2020).

In addition, in the context of chronic illness, it is demonstrated that a group format facilitates the expression and sharing of emotions of both members of the dyad (Saita et al., 2014, 2016) and is cheaper in terms of time and resources compared with individual sessions (Saita et al., 2014).

The use of digital tools might also ensure greater adherence to behavioral changes and support the emotional state of both patients and their partners outside the clinical settings (Graffigna et al., 2017; Dinesen et al., 2019; Bertuzzi et al., 2022). Specifically, telemedicine could be useful to assess caregivers’ burden and to offer specific psychological support to those partners who experience adverse outcomes (Semonella et al., 2022, 2023).

The available literature on couple-based intervention for cardiac patients is scarce and inconsistent, and mostly focused on the outcomes of the sufferers. More research also considering the dyadic component of the intervention and the specific effect of a given program on informal caregivers is urgently needed. Indeed, in the context of chronic diseases, a fundamental role in supporting the patients is played by their informal caregivers, i.e., those who provide unpaid care to their loved ones (Rapelli et al., 2022, 2023; Semonella et al., 2023).

Caring for a significant other can be a rewarding experience, but due to a lack of time and energy, or financial, emotional, and social strains, it can also turn out to be an overwhelming responsibility for caregivers (Donato et al., 2020; Rapelli et al., 2020a; Bertuzzi et al., 2021).

Therefore, it is important to ensure the wellbeing of partners of individuals with cardiovascular disease, and adequately support them with tailored and integrated healthcare actions within the context of cardiac rehabilitation and through the use of telemedicine.

GR, EG, CT, GP, and GC contributed to the development of the study, analysis of the results, and writing of the manuscript. AM, GV, and CF revised the manuscript, reviewed methodological as well as clinical issues, and further edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer VS declared a past co-authorship with the author AG to the handling editor.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1194767/full#supplementary-material

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 4, 359–373. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Baucom, D. H., Shoham, V., Mueser, K. T., Daiuto, A. D., and Stickle, T. R. (1998). Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 66, 53–88. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.53

Beasley, C. C., and Ager, R. (2019). Emotionally focused couples therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness over the past 19 years. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work 16, 144–159. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2018.1563013

Bertoni, A., Donato, S., Graffigna, G., Barello, S., and Parise, M. (2015). Engaged patients, engaged partnerships: Singles and partners dealing with an acute cardiac event. Psychol. Health Med. 20, 505–517. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.969746

Bertoni, A., Rapelli, G., Parise, M., Pagani, A. F., and Donato, S. (2022). “Cardiotoxic” and “cardioprotective” partner support for patient activation and distress: Are two better than one? Fam. Relat. 72, 1335–1350. doi: 10.1111/fare.12694

Bertuzzi, V., Semonella, M., Bruno, D., Manna, C., Edbrook-Childs, J., Giusti, E. M., et al. (2021). Psychological support interventions for healthcare providers and informal caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:6939.

Bertuzzi, V., Semonella, M., Castelnuovo, G., Andersson, G., and Pietrabissa, G. (2022). Synthesizing stakeholders perspectives on online psychological interventions to improve the mental health of the italian population during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 7008.

Bouchard, K., Greenman, P. S., Pipe, A., Johnson, S. M., and Tulloch, H. (2019). Reducing caregiver distress and cardiovascular risk: A focus on caregiver-patient relationship quality. Can. J. Cardiol. 35, 1409–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.05.007

Bowlby, J. (1969). Disruption of affectional bonds and its effects on behavior. Canadas Ment. Health Suppl. 59:12.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss. Volume II. Separation, anxiety and anger. New York, NY: Basic Books, 429.

Breuer, N., Sender, A., Daneck, L., Mentschke, L., Leuteritz, K., Friedrich, M., et al. (2017). How do young adults with cancer perceive social support? A qualitative study. J. Psychos. Oncol. 35, 292–308. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2017.1289290

Cook, W. L., and Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 29, 101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000

Daugherty, J., Saarmann, L., Riegel, B., Sornborger, K., and Moser, D. (2002). Can we talk? Developing a social support nursing intervention for couples. Clin. Nurse Special. 16, 211–218.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Dinesen, B., Nielsen, G., Andreasen, J. J., and Spindler, H. (2019). Integration of rehabilitation activities into everyday life through telerehabilitation: Qualitative study of cardiac patients and their partners. J. Med. Internet Res. 21:e13281. doi: 10.2196/13281

DiPietro, L., Caspersen, C. J., Ostfeld, A. M., and Nadel, E. R. (1993). A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 25, 628–642.

Donato, S., Iafrate, R., Bertoni, A. M. M., and Rapelli, G. (2020). “Partner support,” in Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research, ed. F. Maggino, (Cham: Springer), 1–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_2087-2

Dracup, K. A., and Meleis, A. I. (1982). Compliance: An interactionist approach. Nurs. Res. 31, 31–36.

Dracup, K., Meleis, A., Clarck, S., Clyburn, A., Shields, L., and Staley, M. (1984). Group counseling in cardiac rehabilitation: Effect on patient compliance. Patient Educ. Counsel. 6, 169–177. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(84)90053-3

Endler, N. S., and Parker, J. D. (1990). Stress and anxiety: Conceptual and assessment issues. Stress Med. 6, 243–248. doi: 10.1002/smi.2460060310

Fait, K., Vilchinsky, N., Dekel, R., Levi, N., Hod, H., and Matetzky, S. (2018). Cardiac-diseaseinduced PTSD and Fear of illness progression: Capturing the unique nature of disease related PTSD. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 53, 131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.02.011

Fiske, V., Coyne, J. C., and Smith, D. A. (1991). Couples coping with myocardial infarction: An empirical reconsideration of the role of overprotectiveness. J. Fam. Psychol. 5, 4–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.5.1.4

Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 839–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839

Funk, J. L., and Rogge, R. (2007). The couples satisfaction index (CSI). Michigan: Fetzer Institute.

George-Levi, S., Vilchinsky, N., Tolmacz, R., Khaskiaa, A., Mosseri, M., and Hod, H. (2016). “It takes two to take”: Caregiving style, relational entitlement, and medication adherence. J. Fam. Psychol. 30, 743–751. doi: 10.1037/fam0000203

Gill, R., and Murkin, J. M. (1996). Neuropsychologic dysfunction after cardiac surgery: What is the problem? J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 10, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/S1053-0770(96)80183-2

Golan, M., and Vilchinsky, N. (2023). It takes two hearts to cope with an artificial one: The necessity of applying a dyadic approach in the context of left ventricular assist device transplantation—Opinion paper. Front. Psychol. 14:1215917. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1215917

Golan, M., Vilchinsky, N., Wolf, H., Abuhazira, M., Ben-Gal, T., and Naimark, A. (2023). Couples’ coping strategies with left ventricular assist device implantation: A qualitative dyadic study. Qual. Health Res. 33, 741–752. doi: 10.1177/10497323231168580

Gortner, S. R., Gilliss, C. L., Shinn, J. A., Sparacino, P. A., Rankin, S., Leavitt, M., et al. (1988). Improving recovery following cardiac surgery: A randomized clinical trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 13, 649–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1988.tb01459.x

Graffigna, G., Barello, S., Riva, G., Savarese, M., Menichetti, J., Castelnuovo, G., et al. (2017). Fertilizing a patient engagement ecosystem to innovate healthcare: Toward the first Italian Consensus conference on patient engagement. Front. Psychol. 8:812. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00812

Hartford, K., Wong, C., and Zakaria, D. (2002). Randomized controlled trial of a telephone intervention by nurses to provide information and support to patients and their partners after elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Effects of anxiety. Heart Lung 31, 199–206. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2002.122942

Hartmann, M., Bäzner, E., Wild, B., Eisler, I., and Herzog, W. (2010). Effects of interventions involving the family in the treatment of adult patients with chronic physical diseases: A meta-analysis. Psychother. Psychosom. 79, 136–148. doi: 10.1159/000286958

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., et al. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348: g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

Huang, X., Lin, J., and Demner-Fushman, D. (2006). “Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions,” in Proceedings of the AMIA annual symposium, Vol. 2006, (Bethesda, MD: American Medical Informatics Association), 359.

Jacox, A. K., Bausell, R. B., and Mahrenholz, D. M. (1997). Patient satisfaction with nursing care in hospitals. Outcomes Manag. Nurs. Pract. 1, 20–28.

Johnston, M., Foulkes, J., Johnston, D. W., Pollard, B., and Gudmundsdottir, H. (1999). Impact on patients and partners of inpatient and extended cardiac counseling and rehabilitation: A controlled trial. Psychosom. Med. 61, 225–233.

Khan, K. S., Kunz, R., Kleijnen, J., and Antes, G. (2003). Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 96, 118–121. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). “Learning in doing: Social, cognitive, and computational perspectives,” in Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation Vol. 10, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 109–155.

Lazarus, R. S. (1974). Psychological stress and coping in adaptation and illness. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 5, 321–333. doi: 10.2190/T43T-84P3-QDUR-7RTP

Leifheit-Limson, E. C., Kasl, S. V., Lin, H., Buchanan, D. M., Peterson, P. N., Spertus, J. A., et al. (2012). Adherence to risk factor management instructions after acute myocardial infarction: The role of emotional support and depressive symptoms. Ann. Behav. Med. 43, 198–207. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9311-z

Lenz, E. R., and Perkins, S. (2000). Coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients and their family member caregivers: Outcomes of a family-focused staged psychoeducational intervention. Appl. Nurs. Res. 13, 142–150. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2000.7655

Locke, H. J., and Wallace, K. M. (1959). Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage Fam. Living 21, 251–255.

Luttik, M. L., Blaauwbroek, A., Dijker, A., and Jaarsma, T. (2007). Living with heart failure: Partner perspectives. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 22, 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.05.004

Maeda, U., Shen, B. J., Schwarz, E. R., Farrell, K. A., and Mallon, S. (2013). Self-efficacy mediates the associations of social support and depression with treatment adherence in heart failure patients. Int. J. Behav. Med. 20, 88–96. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9215-0

Martire, L. M., Schulz, R., Helgeson, V. S., Small, B. J., and Saghafi, E. M. (2010). Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 325–342. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2

McCubbin, H. I., and Patterson, J. M. (2014). “The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation,” in Social stress and the family, H. I. M. McCubbin, M. S. B. Sussman and J. M. Patterson (Milton Park: Routledge), 7–37.

McCubbin, H. I., Comeau, J. K., and Harkins, J. A. (1987). “Family inventory of resources for management,” in Family assessment inventories for research and practice, (New York, NY: Oxford University), 145–160.

McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., and Droppleman, L. F. (1971). Profile of mood states. San Diego, CA: Educationai and Industrial Testing SeMce.

Nelson, E. C., Wasson, J. H., and Kirk, J. W. (1987). Assessment of function in routine clinical practice: Description of the COOP chart method and preliminary findings. J. Chron. Dis. 49(Suppl. 1), 55S–63S.

Patrick, D. L., and Peach, H. (1989). “A socio-medical approach to disablement,” in Disablement in the Community, eds D. L. Patrick and H. Peach (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–18.

Prochaska, J. O., and DiClemente, C. C. (2005). The transtheoretical approach. Handb. Psychother. Integr. 2, 147–171.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

Randall, G., Molloy, G. J., and Steptoe, A. (2009). The impact of an acute cardiac event on the partners of patients: A systematic review. Health Psychol. Rev. 3, 1–84. doi: 10.1080/17437190902984919

Rankin-Esquer, L. A., Deeter, A. K., Froeliche, E., and Taylor, C. B. (2000). Coronary heart disease: Intervention for intimate relationship issues. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 7, 212–220. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(00)80034-6

Rapelli, G., Donato, S., and Bertoni, A. (2020a). Il partner del paziente cardiologico: Chi sostiene chi? Psicol. Della Salute 1, 92–103. doi: 10.3280/PDS2020-001008

Rapelli, G., Donato, S., Bertoni, A., Spatola, C., Pagani, A. F., Parise, M., et al. (2020b). The combined effect of psychological and relational aspects on cardiac patient activation. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 27, 783–794. doi: 10.1007/s10880-019-09670-y

Rapelli, G., Donato, S., Pagani, A. F., Parise, M., Iafrate, R., Pietrabissa, G., et al. (2021). The association between cardiac illness-related distress and partner support: The moderating role of dyadic coping. Front. Psychol. 12:106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624095

Rapelli, G., Donato, S., Parise, M., Pagani, A. F., Castelnuovo, G., Pietrabissa, G., et al. (2022). Yes, i can (With You)! Dyadic coping and self-management outcomes in cardiovascular disease: The mediating role of health self-efficacy. Health Soc. Care Commun. 30:e2604–e2617. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13704

Rapelli, G., Giusti, E. M., Donato, S., Parise, M., Pagani, A. F., Pietrabissa, G., et al. (2023). The heart in a bag”: The lived experience of patient-caregiver dyads with Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD) during cardiac rehabilitation. Front. Psychol. 14:913. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1116739

Reid, J., Ski, C. F., and Thompson, D. R. (2013). Psychological interventions for patients with coronary heart disease and their partners: A systematic review. PLoS one 8:e73459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073459

Roger, V. L., Sidney, S., Fairchild, A. L., Howard, V. J., Labarthe, D. R., Shay, C. M., et al. (2020). Recommendations for cardiovascular health and disease surveillance for 2030 and beyond: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 141, e104–e119. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000756

Saita, E., Acquati, C., and Molgora, S. (2016). Promoting patient and caregiver engagement to care in cancer. Front. Psychol. 7:1660. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01660

Saita, E., Molgora, S., and Acquati, C. (2014). Development and evaluation of the cancer dyads group intervention: Preliminary findings. J. Psychos. Oncol. 32, 647–664. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2014.955242

Savioni, L., Triberti, S., Durosini, I., Sebri, V., and Pravettoni, G. (2022). Cancer patients’ participation and commitment to psychological interventions: A scoping review. Psychol. Health 37, 1022–1055.

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., and Fergusson, D. (2010). CONSORT 2010 changes and testing blindness in RCTs. Lancet 375, 1144–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60413-8

Sebri, V., Mazzoni, D., Triberti, S., and Pravettoni, G. (2021). The impact of unsupportive social support on the injured self in breast cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 12:722211. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722211

Semonella, M., Andersson, G., Dekel, R., Pietrabissa, G., and Vilchinsky, N. (2022). Making a virtue out of necessity: COVID-19 as a catalyst for applying Internet-based psychological interventions for informal caregivers. Front. Psychol. 13:856016. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.856016

Semonella, M., Bertuzzi, V., Dekel, R., Andersson, G., Pietrabissa, G., and Vilchinsky, N. (2023). Applying dyadic digital psychological interventions for reducing caregiver burden in the illness context: A systematic review and a meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 13:e070279.

Sher, T., Braun, L., Domas, A., Bellg, A., Baucom, D. H., and Houle, T. T. (2014). The partners for life program: A couples approach to cardiac risk reduction. Fam. Process 53, 131–149. doi: 10.1111/famp.12061

Shiffman, D., Louie, J. Z., Devlin, J. J., Rowland, C. M., and Mora, S. (2020). Concordance of cardiovascular risk factors and behaviors in a multiethnic US nationwide cohort of married couples and domestic partners. JAMA Netw. Open 3:e2022119.

Smilkstein, G. (1978). The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J. Fam. Pract. 6, 1231–1239.

Smith, V., Devane, D., Begley, C. M., and Clarke, M. (2011). Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15

Sokoreli, I., De Vries, J. J. G., Pauws, S. C., and Steyerberg, E. W. (2016). Depression and anxiety as predictors of mortality among heart failure patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail. Rev. 21, 49–63. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9517-4

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J. Marriage Fam. 38, 15–28.

Stephens, M. A. P., Martire, L. M., Cremeans-Smith, J. K., Druley, J. A., and Wojno, W. C. (2006). Older women with osteoarthritis and their caregiving husbands: Effects of pain and pain expression on husbands’ well-being and support. Rehabil. Psychol. 51, 3–12. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.51.1.3

Stewart, M., Davidson, K., Meade, D., Hirth, A., and Weld-Viscount, P. (2001). Group support for couples coping with a cardiac condition. J. Adv. Nurs. 33, 190–199.

Thompson, D. R. (1989). A randomized controlled trial of in-hospital nursing support for first time myocardial infarction patients and their partners: Effects on anxiety and depression. J. Adv. Nurs. 14, 291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03416.x

Tulloch, H., Johnson, S., Demidenko, N., Clyde, M., Bouchard, K., and Greenman, P. S. (2021). An attachment-based intervention for patients with cardiovascular disease and their partners: A proof-of-concept study. Health Psychol. 40, 909–919. doi: 10.1037/hea0001034

Vilchinsky, N., Ginzburg, K., Fait, K., and Foa, E. B. (2017). Cardiac-disease-induced PTSD (CDI-PTSD): A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 55, 92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.009

Wiebe, S. A., and Johnson, S. M. (2016). A review of the research in emotionally focused therapy for couples. Fam. Process 55, 390–407. doi: 10.1111/famp.12229

Keywords: heart diseases, partner support, couple-based interventions, psychological interventions, scoping review

Citation: Rapelli G, Giusti EM, Tarquinio C, Varallo G, Franceschini C, Musetti A, Gorini A, Castelnuovo G and Pietrabissa G (2023) Psychological couple-oriented interventions for patients with heart disease and their partners: a scoping review and guidelines for future interventions. Front. Psychol. 14:1194767. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1194767

Received: 27 March 2023; Accepted: 21 August 2023;

Published: 29 September 2023.

Edited by:

Steve Schwartz, Individuallytics, United StatesReviewed by:

Valeria Sebri, European Institute of Oncology (IEO), ItalyCopyright © 2023 Rapelli, Giusti, Tarquinio, Varallo, Franceschini, Musetti, Gorini, Castelnuovo and Pietrabissa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giada Rapelli, Z2lhZGEucmFwZWxsaUB1bmlwci5pdA==; Giada Pietrabissa, Z2lhZGEucGlldHJhYmlzc2FAdW5pY2F0dC5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.