- Muş Alparslan University, Muş, Türkiye

Introduction: Advances in technology make it easier for users to post content on social media. People can post different types of content in digital environments. Sometimes, they post such content in risky situations. Accordingly, this study aims to determine the sociological and psychological reasons why people record dangerous occurrences where they or other people are under risk or threat and post these recordings on social media.

Methods: This study aimed to answer five research questions. a) Why do individuals use social media? b) Why do people post on social media? c) What types of posts do people share on social media? d) What are the possible psychological reasons that push people to share such occurrences on social media? e) Why do individuals feel the need to record and share dangerous occurrences while under risk or danger? This study was conducted on the basis of a case study design, and interviews were conducted with two psychiatrists, two specialist clinical psychologists, and two sociologists.

Results: After the interviews, the reasons why individuals use social media platforms and post on the said platforms were laid out. It can be argued that the most prominent reason behind individuals’ tendency to post while under risk or threat is isolation and inability to help.

1 Introduction

Creating and sharing content in digital environments has become easier with the transition from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 (Creighton, 2012; Hiremath and Kenchakkanavar, 2016; Lomicka and Lord, 2016; Hackl et al., 2022; Lin, 2023). While it was previously necessary to possess knowledge and expertise to produce content and share it in the digital environment, today, there is no longer a need for a high level of technological or digital literacy to do so (Pangrazio and Sefton-Green, 2021). The produced content attracts more attention when it is posted on social media platforms. Any subject/phenomenon that attracts relatively more individuals is instantly shared with the whole world via social media, finds countless sharers, and is discussed (Tellis et al., 2019; Talwar et al., 2020). This can be attributed to the increase in ownership of smartphones (95.9%) and the easy availability of mobile internet connection (We Are Social, 2023). The same report also states that individuals spend 6 h and 37 min on the internet daily, with 2 h and 31 min of that time being spent on social media. According to Similarweb (2023), the majority of the 20 most popular websites worldwide are social media platforms. Individuals now aspire to be present and post on social media all the time. A life without social media is unimaginable for many (Singh et al., 2019). While the concepts of time and space are being transformed with the digital environment, the line between the watcher and the watched has disappeared, and the individual has become both a watcher and watched (Uluç and Yarcı, 2017; Georgakopoulou, 2021; Oguafor and Nevzat, 2023). One-day posts (stories, statuses) facilitate the use of social networks and enable users to create interesting content based on recent updates rather than events from the past (Davidson-Wall, 2018; Maares et al., 2021). After a point, this situation becomes problematic. Posts where ethical concerns are not at the forefront are now shared on social media. That The social media blurs the boundaries between presence and absence, time and space (Kelly, 2016; Finkler, 2023), control and freedom (Baym and Boyd, 2012; Trepte, 2021), personal and mass communication, private and public (Tombul and Sarı, 2021; Sun et al., 2022), and virtual and real (Floridi, 2014; Levin and Mamlok, 2021). It can be said that this situation makes it easier for individuals to share information that they are hesitant to share in real life, therefore eroding the meaning of privacy and private information (Budak, 2018; Chattopadhyay et al., 2021). Images of people under risk or threat are recorded and shared on social media in different instances, such as parents sharing posts about their children freely (Fox and Hoy, 2019; Verswijvel et al., 2019; Ranzini et al., 2020).

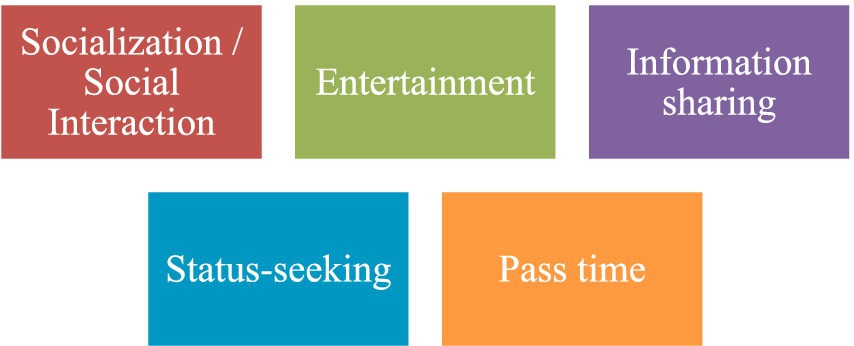

By and large, there are various reasons why individuals use the Internet. Subject to change with the content of the accessed websites, the purpose of Internet use can be online communication and socialization with the social circle (Bilgin, 2018), accessing information (Kwon and Wen, 2010; Hazar, 2011; Park and Kim, 2013; Firth et al., 2019), and entertainment (Ryan et al., 2014; Çömlekçi and Başol, 2019) As for social media platforms, the reasons of entertainment and personal gratification stand out (Dunne et al., 2010; Papacharissi and Mendelson, 2011; Ibáñez-Sánchez et al., 2022). According to the Digital 2022 Global Overview Report by We Are Social, among the purposes of using social media are keeping up with the current news and events, finding entertaining content, killing time, keeping up with friends’ lives, and posting (photos, videos, etc.) (We Are Social, 2023). Thanks to online communication channels such as social media platforms, the formation of a relationship between individuals is facilitated, shyness is overcome, and the need for social belonging is met (Young et al., 2017; Moretta and Buodo, 2020). By sharing statuses and photos on social media, individuals promote themselves and meet the need for self-promotion and self-expression (Vilnai-Yavetz and Tifferet, 2015; Tifferet and Vilnai-Yavetz, 2018; Taylor, 2020). It can thus be said that the use of social media by individuals is somewhat related to the desire for gratification and enjoyment (Gan, 2017; Zafar et al., 2020; Scherr and Wang, 2021; Vaterlaus and Winter, 2021). Five different categories related to gratification and enjoyment stand out in the literature (Figure 1).

As seen in Figure 1, socialization or social interaction, entertainment, information sharing, desire to achieve status, and killing time can be listed among the reasons for using social media. Dunne et al. (2010) stated that the primary reason for individuals to use social media is to fulfill the need for socializing. Individuals of all ages use social media platforms actively in order to maintain or expand their friendship networks and to gather or share information (Duggan et al., 2015; Spottswood and Wohn, 2020). The fact that humans are social beings is the underlying reason for socialization and social interaction. Individuals seek to satisfy their need for belonging and interaction with others by chatting and establishing relationships with them (Whiting and Williams, 2013; Alutaybi et al., 2020). Individuals also wonder what their friends do to socialize. Of social media users, 47.6% are curious about and check out what their friends are doing through social media platforms (We Are Social, 2023). Individuals who use social media for entertainment purposes want to enjoy the moment and relieve their day-to-day concerns (Ma et al., 2011; Brailovskaia et al., 2020; Pelletier et al., 2020; Raza et al., 2020). According to a report by We Are Social (2021), the rate of those who use social media to browse through entertaining content is 35%. In terms of information sharing, social media is interactive and allows users to share information via a two-way dialogue (Whiting and Williams, 2013; Aichner et al., 2021). According to a report by We Are Social (2021), the rate of those who use social media for sharing posts is 27.9%. Status-seeking gratification refers to the desire to be correct, therefore strengthening own feelings and morals (Thompson et al., 2019). By sharing posts on social media, individuals contribute to it. When other members of the platform approve of the contribution to the pool of information, it creates the perception of enhancement of the sharer’s social status (Cheung et al., 2011; Verduyn et al., 2020). Among the prominent functions of social media are self-promotion, willingly revealing personal information, and the aspiration to share a much more positive and ideal representation of one’s life (Błachnio et al., 2013; Lupton, 2021; Ugwudike et al., 2023). The pass-time gratification is defined as using social media to kill time and relieve boredom (Whiting and Williams, 2013; Whelan et al., 2020). According to We Are Social (2023), the rate of those who use social media to pass time is 36.3%. Approving or sharing content on social media is about passing leisure time (Kırcaburun et al., 2020). Accordingly, this study aims to determine the sociological and psychological reasons why people record dangerous occurrences where they or other people are under risk or threat and post these recordings on social media. Accordingly, this study aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. Why do people use social media?

RQ2. Why do people post on social media?

RQ3. What types of posts do people share on social media?

RQ4. What are the possible psychological reasons that push people to share such occurrences on social media?

RQ5. Why do individuals feel the need to record and share dangerous occurrences while under risk or danger?

This study consists of seven sections. In the following section, the background of the culture of posting on social media will be presented. The third section describes the methodology through which the review processes were conducted. The fourth section presents the results, followed by the fifth section which reports on the research questions’ results. The sixth section presents a discussion of the review, and its conclusion. Finally, the last section presents suggestions to further studies.

2 Methods

2.1 Research model

Case studies are defined as an in-depth description and exploration of a limited sample (Merriam, 2013) and they aim to reveal why the event occurred in that way and what should be focused on in future studies (Davey, 1990). Case studies have continued to be the preferred research method in this regard (Niemi and Kousa, 2020; Shahzad et al., 2020). Similarly, as the aim of this study is to reveal an existing situation in detail, the case study model was chosen for use in this study.

2.2 Participants

The participants of the study are two psychiatrists, two expert clinical psychologists, and two sociologists, who are experts in their fields. Expert psychiatrists, expert clinical psychologists, and sociologists who have conducted studies on social media and the effects of social media have been prioritized while selecting participants. The said experts were contacted via e-mail and informed about the study, and those who accepted to conduct an interview became the participants of the study. The participants were coded as P1, P2, etc. according to the chronological order of interviews.

2.3 Data collection and analysis

A semi-structured interview form prepared by the researcher and consisting of five questions was used during data collection. Expert opinions were consulted in order to ensure the validity and reliability of the questions. During the data collection phase, online interviews were held with the mentioned experts, the durations of which varied between 8 and 23 min. The interviews were recorded after obtaining the verbal consent of the participants and the meetings were transcribed afterward. After transcription, the researcher determined the codes, the theme, and the sub-categories.

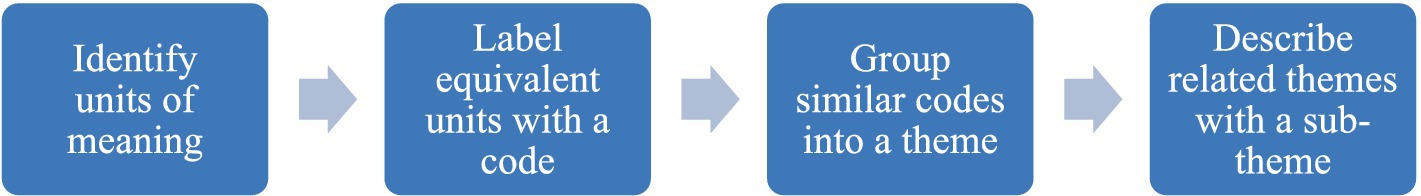

The research findings were obtained through content analysis of the answers given to the questions in the semi-structured interview form. In content analysis, data is categorized into codes, categories, and themes (Miles et al., 2014). Content analysis allows for the analysis of content not only through coding but also by examining themes and subthemes within the content (Graneheim et al., 2017; Lindgren et al., 2020). Yıldırım and Şimşek (2000) emphasize that codes, categories, or themes should be more abstract, general, and inclusive than the concepts obtained in content analysis (Figure 2).

Therefore, the obtained data were first coded, and the codes containing the same expressions were gathered under a common parent theme. After assigning codes and themes, the main themes were determined in line with the purposes described by the questions asked, and the data were grouped accordingly. In order to enhance the reliability of the study by avoiding researcher bias and to keep the internal consistency high, the data were coded by another expert. To enhance the reliability of the research and maintain high internal consistency, the coding process involved having another expert also code the data to protect against the individual influence of the researcher. To strengthen the reliability of the codes determined by both researchers, the agreement formula proposed by Miles et al. (2020) was used (Reliability Formula: Agreement/Agreement + Disagreement * 100). The agreement percentage obtained through this formula was above 85% for all questions. In order for internal consistency to be high, the consensus among the coders is needed (Baltacı, 2017).

3 Results

The participants were asked five questions as a part of the study, which investigates the sociological and psychological reasons behind individuals’ urge to post on social media while they or others are under risk or threat. These five questions are (a) Why do people use social media; (b) Why do people post on social media; (c) What types of posts do people share on social media; (d) What are the possible psychological reasons that push people to share such occurrences on social media and (e) Why do individuals feel the need to record and share dangerous occurrences while under risk or danger? According to content analysis, data has been presented in tables as codes, themes, and subthemes. When moving from codes to subthemes, a path is followed from general to specific. This is also explained in Figure 2. In this section, the findings obtained from the answers were addressed along with the respective questions.

3.1 Individuals’ purposes for using social media

In this section, findings related to why people use social media are presented. Generally speaking, the reasons why individuals use social media can be divided into groups such as communication, intimidation, commercial, information sharing, presence, and interaction (Table 1).

When Table 1 is examined, it can be seen that people undeniably use social media for communication. Social media platforms, which were primarily developed for the purpose of posting photos or messages, now allow people to communicate with each other in visual, audio, and written forms. Even without these features, people could communicate with each other through their posts. Another use of social media is to intimidate others. While sometimes this intimidation takes up the form of bullying, sometimes it is panicking others through fake news. Since social media platforms appeal to people who do not have a sufficient digital literacy level to operate other platforms such as websites, individuals can easily advertise their work on social media. So, social media platforms are also used for commercial purposes. Individuals can advertise their work, just like large companies, which do so through “Influencers.”

Another reason for the use of social media is to share information with others. Some use social media platforms to disseminate information on a certain subject, conveying their fund of knowledge to as many people as possible. Perhaps the most important reason for the use of social media is that it allows individuals to promote themselves, participate in life, and say “me too.” In other words, social media platforms are important in the sense that it enables individuals to manifest their presence. People can see what other people (celebrities) are doing, what they eat, and what they possess on various platforms (one-sided). Social media platforms now provide a medium where average people can promote the activities they do (going around, eating, drinking coffee, taking a vacation, going to the movies, etc.) like the people they follow or other people around them and get the message “I can do it, too/I am doing it” across. The existence of the “Like” button increased users’ efforts to promote their existence. Another reason for the use of social media platforms is the desire of humans, who are social beings, to interact with other people. In addition to interacting with other people, it is important for individuals to have a large number of followers. Because the more the followers, the more the “likes.” People also prioritize not feeling like missing out on something while interacting with others. In traditional news outlets, the act of disseminating news was one-way and in the form of receiving the news. However, on social media platforms, individuals wish to receive news and see posts about people they are curious about quickly and do not want to miss out on the latest developments. Therefore, they turn to social media platforms to receive news.

3.2 Individuals’ purposes for sharing posts

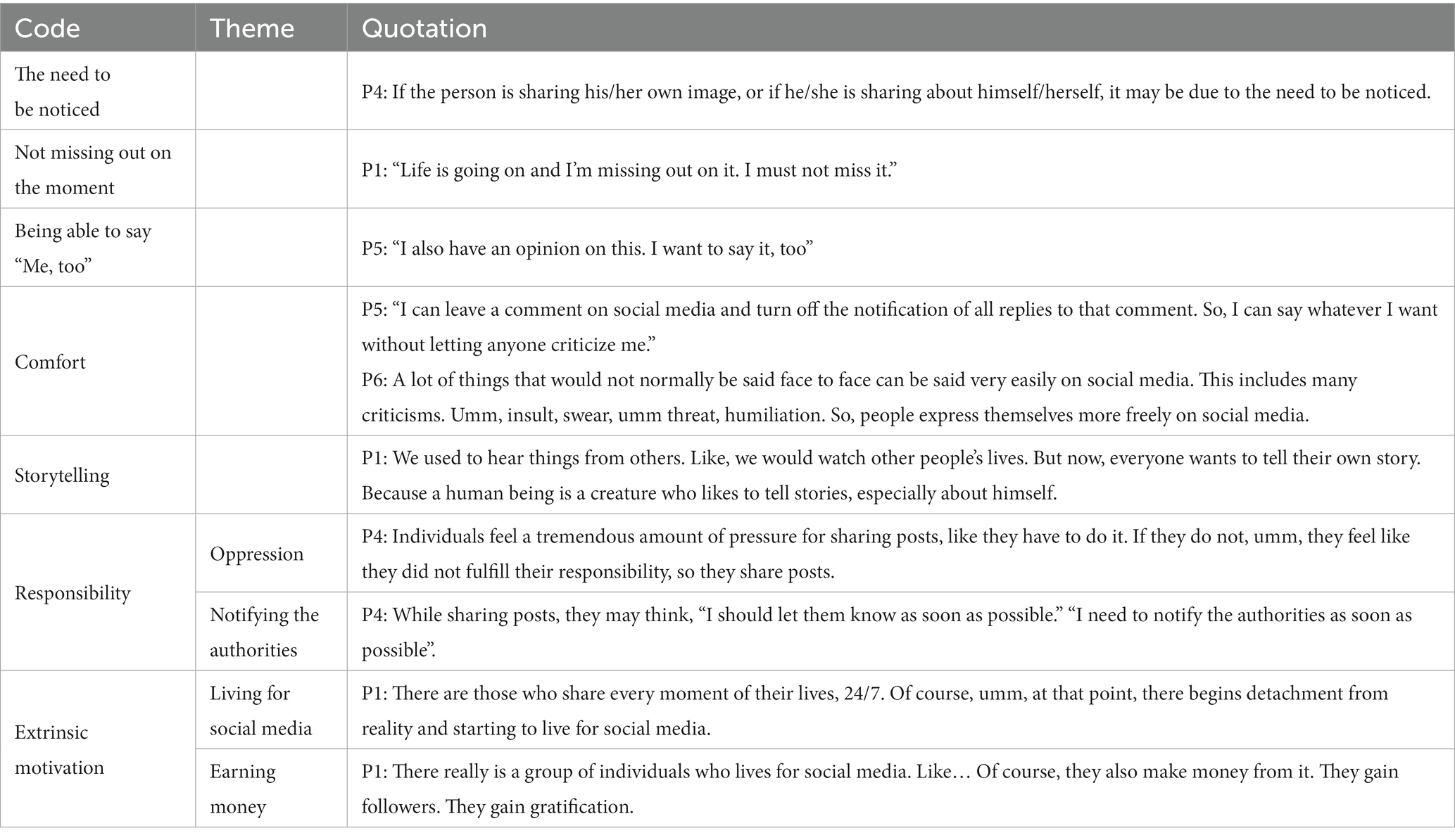

In this section, findings related to why people share content on social media are presented. While individuals use social media platforms for these purposes, they also prefer to share posts there, too. The reasons why people share posts on these platforms can be summarized as seen in Table 2.

Individuals share posts on social media to fulfill their need to be noticed. Such posts usually are shared in the form of images, mostly containing the individual, too. Individuals may share posts by acting upon the impulse of revealing “I am in these environments like you, see me too.” Another purpose of posting on social media is the desire not to lose the moment. Life is finite and posts can be shared in order to savor specific memories, to save them. People who post on social media do so also in order to be able to say “Me, too.” In other words, people who have an opinion on a subject can express their opinion and answer a question asked on social media. The most important advantage of posing on social media platforms is its convenience. Sometimes individuals recklessly utter statements about others that they would otherwise be unable to tell to their faces; they also can easily make positive or negative comments. While expressing an opinion on a subject, posts can also be closed for comments to prevent anyone from approaching a comment from a critical point of view. Individuals enjoy this convenience while posting on social media. Being social creatures, humans used to watch the stories about the lives of others in traditional media outlets. With social media, however, they found a medium where they can share their own stories. Responsibility is an important factor that pushes people to share posts on social media platforms. This is observed especially in public events. For example, in cases of femicide, posts against it are shared, and individuals think “everyone shares it, I need to share a post about this, too. I have a responsibility.” In some cases, there is an impulse to share posts on social media in order to inform the relevant authorities about an event witnessed somewhere. Extrinsic motivation is perhaps the most influential factor affecting the motivation to share posts on social media platforms. In general, individuals act upon extrinsic motivation factors such as getting likes, gaining followers, or a sense of responsibility. Individuals who share every moment of their lives on these platforms and cannot break away from them are steered by extrinsic motivation. There is another group of individuals who share posts on these platforms because they earn money. Money is also an extrinsic motivation source and posts are shared in order to earn it. There are posts shared on social media platforms for this purpose.

3.3 Types of posts

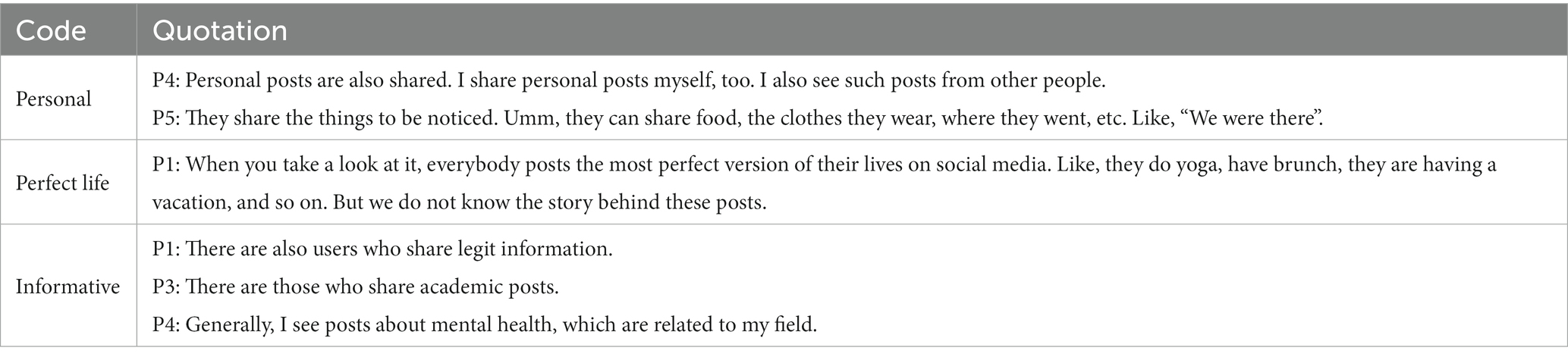

This section includes findings on what type of content people share on social media. The types of content shared for this goal vary (Table 3).

What individuals post on social media varies. Personal posts can be regarded as the most prominent type of post on social media. Individuals can share and present themselves on social media with a selfie or an image that features themselves. They share such posts to say “I’m here, too.” The most widespread of posts are those shared in order to promote a perfect, smooth life. Looking at social media platforms, it can be claimed that everyone has a very good life, their income is high, and they lead a happy life. Another type of post shared on social media platforms is informative content. Such posts aim to transfer knowledge from people who possess a certain level of information on a topic to others. Depending on the social media platform, these contents can be in the form of texts or videos. With the live broadcast feature offered by social media platforms, experts in a given field can share their knowledge interactively and in real time. Individuals’ purposes to use social media platforms, why they share posts, and what kind of posts they share can be summarized as so.

3.4 Socio-psychological reasons that push people to share on social media

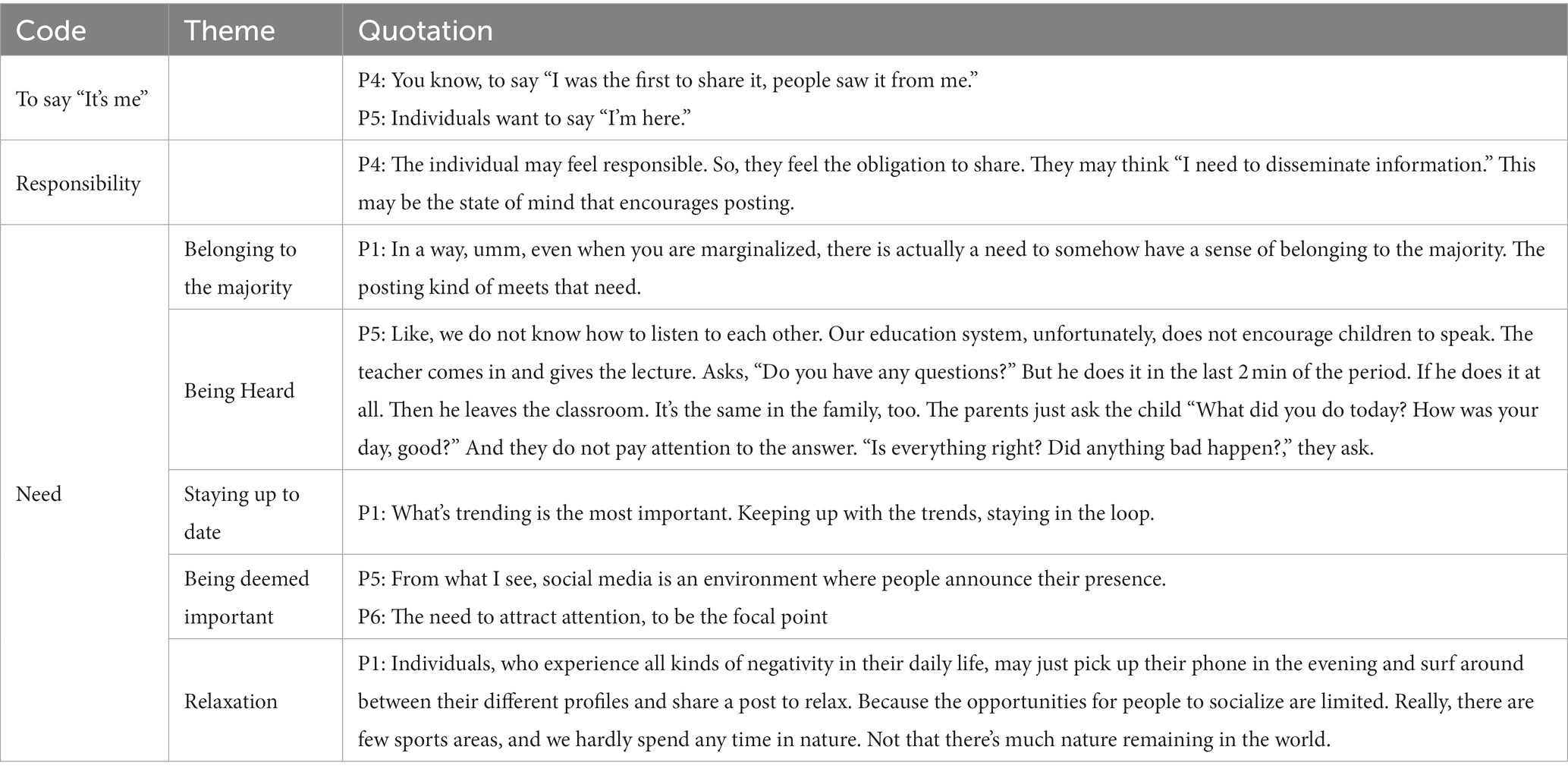

This section includes findings on the psychological reasons that push people to share content on social media. Socio-psychological reasons (Table 4) that push people to share posts on social media are of significant importance. Because individuals use social media platforms voluntarily.

People can share various posts on social media platforms. When we look at the socio-psychological reasons why individuals share such posts, it can be said that the urge of saying “I’m the one” is prominent. They may believe that they should be the first ones to share a post about themselves or a public event. By being the first one to make a comment on such an event, they may want to feel like they are the originator of the information. Or, they may feel the need to announce that they are a part of society, too. Another socio-psychological factor can be claimed to be the feeling of responsibility. Individuals may post due to a sense of responsibility to the environment/society of which they are a part. When we look at the socio-psychological reasons for sharing on social media, it is seen that people share because of a need. These needs can be listed as belonging to the majority, being heard, keeping up with the trends, being deemed important, and relaxing. Being social beings, individuals wish to be included in society and not to be alienated from the majority. Social media platforms offer people an environment where they can make their ideas heard. In everyday life, there are times when people do not listen to each other. However, social media posts are followed with particular attention. So, individuals may use these platforms to be heard. Social media platforms are beginning to replace traditional media and the news now first starts circulating there. Therefore, individuals use social media to get and share the news. The wish to be deemed important is as much a need as the wish to be heard, which social media platforms meet. Social network platforms offer individuals the chance to meet their need to be deemed important through their posts, helping them feel that they are shown the value they deserve. The most prominent socio-psychological reason for posting on or using social media platforms can be claimed to be the need for relaxing. Because in their daily lives, individuals go to work to sustain a living, and worry about themselves and their families. Since opportunities for relaxing in daily life are scarce, social media platforms help individuals relax by browsing around between posts. While individuals generally use social media platforms for these purposes, they may also want to share when they or others are under risk or threat.

3.5 Why people share posts when they or others are under risk or threat?

This section includes findings on why people feel the need to record or share the moment when someone else is at risk or in danger. Reasons for posting in these moments Table 5 can be summarized as shown in Figure 2.

Table 5. Reasons why individuals share posts on social media platforms when they or others are under risk or threat.

People post on social media when they or others are under risk or threat. It can be held that individuals share such posts primarily for the purpose of asking for help. They cannot intervene in the incident, but record it in order to ask for help from their followers or environment. Another reason for posting in such moments can be to raise awareness. Some incidents may be ignored by traditional media outlets. In such cases, social media posts may make a tremendous impact and help solve issues. For example, such posts can be influential in cases of violence against women or child abuse. The desire to be liked may also be a prominent reason. This desire brings with it attention-seeking, and individuals can increase the number of their followers by sharing such posts on social media, which satisfies the need for receiving attention. In some cases, in order to testify, proof may be needed. In order to have evidence, individuals may record the incident and then post it on social media. Some, due to their excrescent need to be liked, overemphasize their involvement. There may be a desire to say “I saw the incident first; I recorded and shared it” behind not intervening and recording and sharing it as a post. So, it can be said that in such cases, there is a narcissistic underlying motivation. There may also be those who make it their mission to share such content. Also, “Whatsapp Hotlines” were established by traditional media outlets in order to broadcast the images they were not present to record, and people send the content they shoot to those hotlines so that they can be telecast. The theme “isolation” is one of the most important findings of the study. Individuals are used to watching images containing violence on traditional media outlets and in order to maintain this habit, they isolate themselves behind their devices. Therefore, instead of watching incidents with the naked eye, they may need to look at the events behind a screen if they are watching the news on television. The theme of escaping is another significant finding of the study. Individuals may be avoiding responsibility. They may think that it is not their duty to intervene but it is the duty of the relevant officials and therefore avoid responsibility. Another reason for escapism may be the lack of problem-solving skills. In order to intervene in an incident (such as a fight, conflict, or accident), it is necessary to have problem-solving knowledge and skills. In addition, it can be said that the fight-flight-freeze response in the face of a shocking event has been added to the “record and post the moment” response. The same is valid for helping. The ability to help is crucial in the face of an incident and in resolving a problem. If a person does not know how to get a sufferer out of a crashed vehicle, he may instead try to record and share the moment to avoid this responsibility. Individuals, by not intervening in the incident, act upon their instinct for security and safeguarding themselves. Accordingly, they may decide to put a device between themselves and the incident rather than intervening. Another fact is that individuals tend to exhibit unethical behaviors more easily while with others.

4 Conclusion and discussion

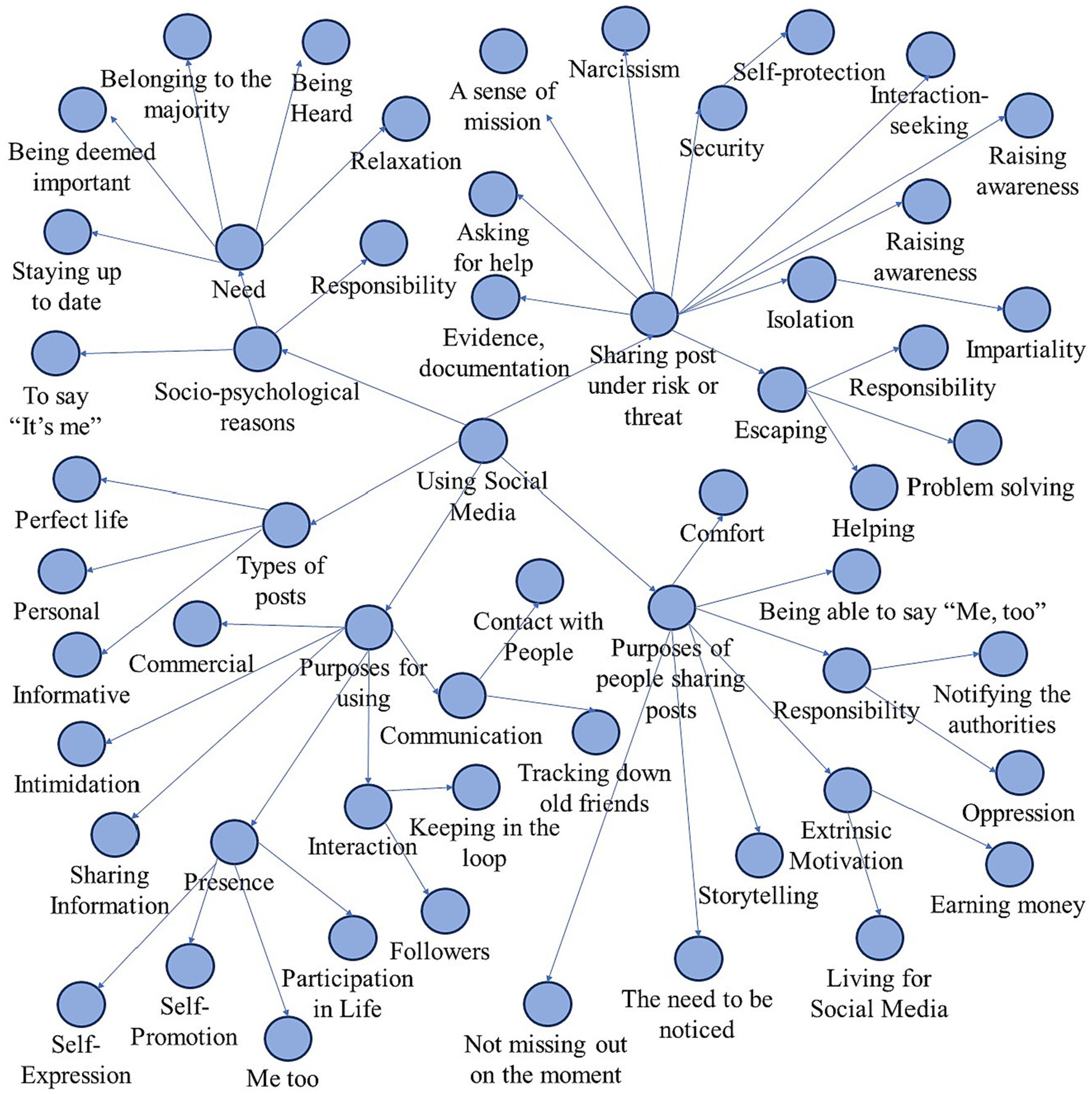

Different themes and sub-themes were identified in this study, in which the socio-psychological reasons why individuals record and post the moment when they or other people are under risk or threat (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Socio-psychological reasons that influence individuals’ use of social media and their posts.

Figure 3 has been organized as a project map in the Nvivo program. The project map is a comprehensive visual aid that assists in discovering the relationships that emerge from the analysis of the data obtained from the study (Mortelmans, 2019). The themes of the purposes of individuals’ social media use can be summarized as communication, intimidation, commercial, information sharing, presence, and interaction. As social beings, humans use social media for communication and interaction. It was stated that social media, which supports participatory communication, is used to express oneself and establish relationships (Sihombing, 2018; Thomas et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021). People can find their old friends on social media platforms, get in touch with people, follow people they know or do not know, and keep up with the latest developments. Social media platforms are used to inform friends about daily experiences, follow other users’ updates, and participate in long public conversations in discussion groups (Sarmiento et al., 2018). Brailovskaia et al. (2020) also list the purposes of using social media as (a) Search for Information and Inspiration; (b) Search for Social Interaction; (c) Beat of Boredom and Pastimes; (d) Escape from Negative Emotions and (e) Search for Positive Emotions. On the other hand, individuals can share various posts in order to intimidate others, too. Such posts usually do not reflect the truth. Social media can also be used for commercial purposes, as it allows to reach out to many people in a short time. These platforms can also be used to share experiences. There are various studies in the literature on uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al., 1974) that aim to understand the reasons why people use certain media platforms. Introne et al. (2018) stated that some of the gratifications that people attain from the use of social media are related to seeking information, sharing knowledge, entertainment, and communication. Seeking information, maintaining relationships, and gaining peer approval are associated with social media use (Dunne et al., 2010; Vaast and Kaganer, 2013; Nesi et al., 2018; Capone et al., 2020; Liu, 2020; Soroya et al., 2021). Also, it can be said that sharing news and information are other sources of gratification attained from using social media (Thompson et al., 2019). It was stated that people use these platforms in order to have fun and pass time, which is a phenomenon that is not among the findings of the study but has been mentioned (Ha et al., 2013; Kolhar et al., 2021). Social media platforms are also used to relax and escape from reality (Lee et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Young et al., 2017).

The reasons for sharing posts on social media can be listed as the need to be noticed, the desire to not miss out on the moment, the wish to say “me too,” social media offering a comfortable environment, the desire to tell a story, responsibility, and extrinsic motivation. Individuals’ desire to be noticed is not limited to the physical environment, they also try to manifest themselves through their posts on social media. This is why they share posts on social media platforms. Also stated that social interaction and connection, as well as self-promotion, are among the main reasons for the use of social networks such as Facebook (Vilnai-Yavetz and Tifferet, 2015; Hajli et al., 2017; Sheldon and Newman, 2019; Sheldon et al., 2021; Ibáñez-Sánchez et al., 2022). The urge not to miss out on the moment is another prominent reason. Individuals use these platforms in order to show others what they are doing and to see what others are doing. They share posts because social media platforms offer a medium where they can freely express their opinions and say “me too”; want to announce what they do and show their life stories to other people on these platforms. Maitri et al. (2023) state that social media allows individuals to express their views and thoughts freely and that their expressions can reach a wide audience. In some cases, however, individuals, due to extrinsic pressure or the motivation to inform the relevant authorities, may post certain incidents, acting upon their sense of responsibility. Recent research has revealed that when sharing information, individuals do not mind if it is true or not as far as it contains precautionary measures on certain issues (Apuke and Omar, 2020). Another purpose of posting on social media is to act upon extrinsic motivation such as getting likes, gaining followers, or earning money.

People share different types of posts on social media. While some share posts about their personal lives and what they have been up to, some share posts that give the appearance of a perfect life. However, the background of the promoted perfect life is also important. The information presented on social media consists mainly of carefully selected photos intended to portray a flawless self-image and an ideal life (Appel et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Schmuck et al., 2019). The viewership rate of more realistic posts rather than idealized lives is also high on social media (Fardouly and Rapee, 2019). However, users continue to have concerns about editing their photos to appear different from their actual selves. There is another group of users that post informative content. In addition to people who share their own experiences, there are also people who share academic posts. Kwahk and Park (2016) stated that since social media environments facilitate the sharing of information and its dissemination between communities and societies, there is an increase in information sharing. Social networking sites also support the dissemination of information by creating a collaborative environment (Ansari and Khan, 2020), and researchers have begun to utilize social media in sharing information because it facilitates information sharing in different contexts (Al Saifi et al., 2016; Bilgihan et al., 2016; Ahmed et al., 2019). Supporting the findings of the study, it was previously stated that individuals who want to keep their social interactions strong are more likely to disclose information as well as share news, including false ones (Apuke and Omar, 2020). In addition, the sharing of fake news or misinformation is also quite common on social media (Talwar et al., 2019; Islam et al., 2020; Mena, 2020; Apuke and Omar, 2021). However, this phenomenon did not emerge in the study results.

The socio-psychological impact of social media takes into account both social and psychological factors responsible for the changes in the behavior, thoughts, and emotions of young individuals influenced by the real or imaginary presence of others on social media (Afsana, 2020). The socio-psychological reasons why people post on social media are being able to say “it’s me,” the sense of responsibility, and need. Social media platforms are environments where individuals introduce themselves and do so by utilizing their individual capabilities (Thompson et al., 2019; Apuke and Omar, 2021). People sometimes want to be the first to share a post on a certain topic on social media. Or they may try to get the message “I’m here, too” across. Sometimes, individuals may share posts due to the responsibility of alerting the relevant authorities. The most important socio-psychological reasons are that individuals feel the need to belong to the majority, be heard, stay up to date, be deemed important, and relax. To meet these needs, individuals share posts on social media. People with a high motivation to seek status, socialize, and seek information post more frequently on social media (Lee and Ma, 2012; Chen et al., 2018; Islam et al., 2020; Malik et al., 2021). However, individuals find it fun to disseminate information online, to exchange information with others within the confines of a social relationship (Anspach and Carlson, 2020; Oliveira et al., 2020).

Individuals share posts when they or others are under risk or threat, too. Among the reasons for this situation are as seeking help, raising awareness, attention-seeking, collecting evidence, documentation, narcissism, a sense of mission, isolation, escaping, and security. People can record and share incidents for the purpose of asking the authorities for help and to document the incident and gather evidence to submit to the relevant authorities. Some incidents may be underpublicized. In such cases, social media posts may help to raise awareness about those occurrences. As stated by Plume and Slade (2018), individuals may act upon their instinct of spreading news and information, without expecting a reward for their sharing. Al-Rawi (2019) and Weeks and Holbert (2013) also found that people are more likely to share content if it is interesting, useful or emotionally engaging. Apuke and Omar (2021) and Ma and Chan (2014) also argued that some social media users may voluntarily collect and disseminate information without expecting any return. Duffy et al. (2020) state that sharing news on social media is seen as contributing to social integration, and users who engage in this behavior are motivated by the emotional impact of the news, the potential interest for the recipient, and the sender’s intention to provide “recommendation or warning.” While sharing news on social media can build or strengthen relationships, sharing fake news can undermine them. Posts are also shared in order to be the first to announce the incident and increase the number of followers, that is, to attract the attention of other social media users. The number of likes or followers obtained on social media is considered an important personal metric (De Cristofaro et al., 2014). However, attention should also be paid to the following point. If a high number of likes or followers are seen in social media posts, this may also indicate that followers or likes have been purchased (De Vries, 2019). While the number of likes and followers is important, such situations may also occur. These are cases where some make it their mission to record and post the event. Another important finding is the instinct of isolation by putting a device in between the incident and the self, witnessing what is happening as if watching it from social media or traditional media outlets. In order to avoid taking responsibility for solving problems or helping, people tend to record and post images of the moment rather than intervening. During and after risky and dangerous occurrences, individuals also look to protect themselves and ensure their safety. Due to such reasons, more and more images and information from these incidents that should actually remain undisclosed are revealed in the social media environment.

5 Limitations

This study has certain limitations. The participants in this study, which investigates the social and psychological reasons behind social media postings, consist of six individuals from three different fields of expertise. Diversifying the fields of expertise may eliminate the limitations of the study in order to access different types of information. Another limitation is the inability to directly access social media users who post under risk and threat.

6 Recommendations

Some findings of this study can serve as a guide for future studies. In the literature, there are many data on the purposes for which social media is used [such as sharing stories, fake news or misinformation (Apuke and Omar, 2020, 2021; Duffy et al., 2020; Sihombing and Aninda, 2022; Annabell, 2023; Talwar et.al, 2020)]. However, there are no psychological studies addressing the background of the reasons for why people record dangerous occurrences where they or other people are under risk or threat and post these recordings on social media. This study features expert opinions that can shed light on this subject. In order to support these views and reveal the associated psychological factors, long-term studies can be conducted with the participation of individuals who share posts on social media. Posting on social media should be considered normal. However, the reasons why individuals post when they or others are under risk or threat, which was the main focal point of this study, should be further examined. The researcher considered contacting people who were eyewitnesses of certain incidents and recorded them instead of intervening, such as a person who filmed a femicide and shared it on social media, risked their own life like a war reporter to record and post a gunfight, and filmed their livestock during a forest fire instead of saving them and posting the footage with the caption “my babies, my dears,” and so on. However, these people could not be reached. Studies can be conducted where such people are interviewed to reveal their sociological characteristics as well as their psychological states when they posted the incidents.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to FY, Zi55YW1hbkBhbHBhcnNsYW4uZWR1LnRy.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I thank the participants who contributed to the current research through their invaluable responses.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afsana, A. (2020). An overvıew of socıo-psychologıcal ımpact of socıal medıa on the youth. J. Crit. Rev. 7, 3535–3538.

Ahmed, Y. A., Ahmad, M. N., Ahmad, N., and Zakaria, N. H. (2019). Social media for knowledge-sharing: a systematic literature review. Telemat. Inform. 37, 72–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.01.015

Aichner, T., Grünfelder, M., Maurer, O., and Jegeni, D. (2021). Twenty-five years of social media: a review of social media applications and definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 24, 215–222.

Al Saifi, S. A., Dillon, S., and McQueen, R. (2016). The relationship between face to face social networks and knowledge sharing: an exploratory study of manufacturing firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 20, 308–326. doi: 10.1108/JKM-07-2015-0251

Al-Rawi, A. (2019). Viral news on social media. Digit. J. 7, 63–79. doi: 10.1080/21670811.2017.1387062

Alutaybi, A., Al-Thani, D., McAlaney, J., and Ali, R. (2020). Combating fear of missing out (FoMO) on social media: the FoMO-R method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 1–28. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176128

Annabell, T. (2023). Sharing ‘memories’ on Instagram: a narrative approach to the performance of remembered experience by young women online. Narrat. Inq. 33, 317–341. doi: 10.1075/ni.21074.ann

Ansari, J. A. N., and Khan, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning. Smart Learn. Environ. 7, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40561-020-00118-7

Anspach, N. M., and Carlson, T. N. (2020). What to believe? Social media commentary and belief in misinformation. Polit. Behav. 42, 697–718. doi: 10.1007/s11109-018-9515-z

Appel, H., Gerlach, A. L., and Crusius, J. (2016). The inter play between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 9, 44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.006

Apuke, O. D., and Omar, B. (2020). Modelling the antecedent factors that affect online fake news sharing on COVID-19: the moderating role of fake news knowledge. Health Educ. Res. 35, 490–503. doi: 10.1093/her/cyaa030

Apuke, O. D., and Omar, B. (2021). Fake news and COVID-19: modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telemat. Inform. 56:101475. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101475

Baltacı, A. (2017). Nitel veri analizinde Miles-Huberman modeli. Ahi Evran Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 3, 1–14.

Baym, N. K., and Boyd, D. (2012). Socially mediated publicness: an introduction. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 56, 320–329. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2012.705200

Bilgihan, A., Barreda, A., Okumus, F., and Nusair, K. (2016). Consumer perception of knowledge-sharing in travel-related online social networks. Tour. Manag. 52:287296, 287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.002

Bilgin, M. (2018). Ergenlerde sosyal medya bağımlılığı ve psikolojik bozukluklar arasındaki ilişki. J. Int. Sci. Resear. 3, 237–247. doi: 10.23834/isrjournal.452045

Błachnio, A., Przepiórka, A., and Rudnicka, P. (2013). Psychological determinants of using Facebook: a research review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 29, 775–787. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2013.780868

Brailovskaia, J., Schillack, H., and Margraf, J. (2020). Tell me why are you using social media (SM)! Relationship between reasons for use of SM, SM flow, daily stress, depression, anxiety, and addictive SM use–an exploratory investigation of young adults in Germany. Comput. Hum. Behav. 113, 106511–106513. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106511

Budak, H. (2018). Sosyal medya iletişiminde mahremiyetin serüveni. İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi 7, 146–170.

Capone, V., Caso, D., Donizzetti, A. R., and Procentese, F. (2020). University student mental well-being during COVID-19 outbreak: what are the relationships between information seeking, perceived risk and personal resources related to the academic context? Sustainability 12:7039. doi: 10.3390/su12177039

Chattopadhyay, S., Zimmermann, T., and Ford, D. (2021). Reel life vs. real life: how software developers share their daily life through vlogs. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM joint meeting on European software engineering conference and symposium on the foundations of software engineering, 404–415.

Chen, Y., Liang, C., and Cai, D. (2018). Understanding WeChat users’ behavior of sharing social crisis information. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 34, 356–366.

Cheung, C. M., Chiu, P. Y., and Lee, M. K. (2011). Online social networks: why do students use Facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.028

Çömlekçi, M. F., and Başol, O. (2019). Gençlerin sosyal medya kullanım amaçları ile sosyal medya bağımlılığı ilişkisinin incelenmesi. Manisa Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 17, 173–188. doi: 10.18026/cbayarsos.525652

Creighton, P. M. (2012). The secret reasons why teachers are not using Web 2.0 tools and what school librarians can do about it. Linworth: ABC-CLIO.

Davidson-Wall, N. (2018). Mum, seriously! Sharenting the new social trend with no opt-out. Available at: http://networkconference.netstudies.org/2018OUA/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Sharenting-the-new-social-trend-with-no-opt-out.pdf

De Cristofaro, E., Friedman, A., Jourjon, G., Kaafar, M. A., and Shafiq, M. Z. (2014). Paying for likes? Understanding Facebook like fraud using honeypots. Proceedings of the 2014 conference on internet measurement, ACM: New York 129–136.

De Vries, E. L. (2019). When more likes is not better: the consequences of high and low likes-to-followers ratios for perceived account credibility and social media marketing effectiveness. Mark. Lett. 30, 275–291. doi: 10.1007/s11002-019-09496-6

Duffy, A., Tandoc, E., and Ling, R. (2020). Too good to be true, too good not to share: the social utility of fake news. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23, 1965–1979. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1623904

Duggan, M., Lenhart, A., Lampe, C., and Ellison, N. B. (2015). Parents and social media. Pew Res Center 16:2.

Dunne, Á., Lawlor, M. A., and Rowley, J. (2010). Young people's use of online social networking sites–a uses and gratifications perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 4, 46–58. doi: 10.1108/17505931011033551

Fardouly, J., and Rapee, R. M. (2019). The impact of no-makeup selfies on young women’s body image. Body Image, 28, 128–134.

Finkler, J. (2023). Solipsism as a factor in content personalization: practice of internet journalism. Bull. Lviv Polytech. Natl. Univ. 1, 50–56. doi: 10.23939/sjs2023.01.050

Firth, J., Torous, J., Stubbs, B., Firth, J. A., Steiner, G. Z., Smith, L., et al. (2019). The “online brain”: how the internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry 18, 119–129. doi: 10.1002/wps.20617

Floridi, L. (2014). The fourth revolution: how the infosphere is reshaping human reality ; Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Fox, A. K., and Hoy, M. G. (2019). Smart devices, smart decisions? Implications of parents’ sharenting for children’s online privacy: an investigation of mothers. J. Public Policy Mark. 38, 414–432. doi: 10.1177/0743915619858290

Gan, C. (2017). Understanding we chatusers’ liking behavior: an empirical study in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 68, 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.002

Georgakopoulou, A. (2021). Small stories as curated formats on social media: the intersection of affordances, values & practices. System 102:102620. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102620

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B. M., and Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 56, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

Guo, J., Liu, N., Wu, Y., and Zhang, C. (2021). Why do citizens participate on government social media accounts during crises? A civic voluntarism perspective. Inf. Manag. 58, 103286–103212. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2020.103286

Ha, L., Yoon, K., and Zhang, X. (2013). Consumption and dependency of social network sites as a news medium: a comparison between college students and general population. J. Commun. Media Res. 5:1.

Hackl, C., Lueth, D., and DiBartolo, T. (2022). Navigating the metaverse: a guide to limitless possibilities in a Web3.0 world. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Hajli, N., Sims, J., Zadeh, A. H., and Richard, M.-O. (2017). A social commerce investigation of the role of trust in a social networking site on purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 71, 133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.004

Hazar, M. (2011). Sosyal medya bağımlılığı: Bir alan çalışması. İletişim, Kuram ve Araştırma Dergisi 32, 151–175.

Hiremath, B. K., and Kenchakkanavar, A. Y. (2016). An alteration of the web 1.0, web 2.0 and web 3.0: a comparative study. Imp. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2, 705–710.

Ibáñez-Sánchez, S., Orus, C., and Flavian, C. (2022). Augmented reality filters on social media. Analyzing the drivers of playability based on uses and gratifications theory. Psychol. Mark. 39, 559–578. doi: 10.1002/mar.21639

Introne, J., Gokce Yildirim, I., Iandoli, L., DeCook, J., and Elzeini, S. (2018). How people weave online information into pseudoknowledge. Soc. Media+Society 4, 205630511878563–205630511878515. doi: 10.1177/2056305118785639

Islam, A. N., Laato, S., Talukder, S., and Sutinen, E. (2020). Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: an affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 159:120201. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201

Islam, T., Mahmood, K., Sadiq, M., Usman, B., and Yousaf, S. U. (2020). Understanding knowledgeable workers’ behavior toward COVID-19 information sharing through WhatsApp in Pakistan. Front. Psychol. 11:572526. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572526

Katz, E., Blumler, J., and Gurevitch, M. (1974). Uses and gratification theory. Public Opin. Q. 37, 509–523. doi: 10.1086/268109

Kırcaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., and Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: a simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 18, 525–547. doi: 10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6

Kolhar, M., Kazi, R. N. A., and Alameen, A. (2021). Effect of social media use on learning, social interactions, and sleep duration among university students. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 2216–2222. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.01.010

Kwahk, K. Y., and Park, D. H. (2016). The effects of network sharing on knowledge-sharing activities and job performance in enterprise social media environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 826–839. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.044

Kwon, O., and Wen, Y. (2010). An empirical study of the factors affecting social network service use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26, 254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.04.011

Lee, E., Lee, J. A., Moon, J. H., and Sung, Y. (2015). Pictures speak louder than words: motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 18, 552–556. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0157

Lee, C. S., and Ma, L. (2012). News sharing in social media: the effect of gratifications and prior experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.002

Levin, I., and Mamlok, D. (2021). Culture and society in the digital age. Information 12:68. doi: 10.3390/info12020068

Lin, H. (2023). Application of web 2.0 technology to cooperative learning environment system design of football teaching. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput., 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2022/5132618

Lindgren, B. M., Lundman, B., and Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies 108:103632.

Liu, P. L. (2020). COVID-19 information seeking on digital media and preventive behaviors: the mediation role of worry. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 677–682. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0250

Lomicka, L., and Lord, G. (2016). Social networking and language learning. Routledge Handb. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2010, 255–268. doi: 10.4324/9781315657899

Lupton, D. (2021). “Sharing is caring”: Australian self-trackers' concepts and practices of personal data sharing and privacy. Front. Digit. Health 3, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.649275

Ma, W. W., and Chan, A. (2014). Knowledge sharing and social media: altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 39, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.015

Ma, L., Lee, C. S., and Goh, D. H. L. (2011), That's news to me: the influence of perceived gratifications and personal experience on news sharing in social media. In Proceedings of the 11th annual international ACM/IEEE joint conference on digital libraries Ottawa, Canada 141–144).

Maares, P., Banjac, S., and Hanusch, F. (2021). The labour of visual authenticity on social media: exploring producers’ and audiences’ perceptions on Instagram. Poetics 84, 101502–101510. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101502

Maitri, W. S., Suherlan, S., Prakosos, R. D. Y., Subagja, A. D., and Ausat, A. M. A. (2023). Recent trends in social media marketing strategy. Jurnal Minfo Polgan 12, 842–850. doi: 10.33395/jmp.v12i2.12517

Malik, A., Mahmood, K., and Islam, T. (2021). Understanding the Facebook users’ behavior towards COVID-19 information sharing by integrating the theory of planned behavior and gratifications. Information Development, 02666669211049383.

Mena, P. (2020). Cleaning up social media: the effect of warning labels on likelihood of sharing false news on Facebook. Policy Internet 12, 165–183. doi: 10.1002/poi3.214

Merriam, A. P. (2013). “Definitions of “comparative musicology” and “ethnomusicology”: an historical-theoretical perspective” in Ethnomusicology (New York: Routledge), 235–250.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J., (2014). Qualitative data analysis: qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook and the coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 4th Edn. Arizona: SAGE.

Moretta, T., and Buodo, G. (2020). Problematic internet use and loneliness: how complex is the relationship? A short literature review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 7, 125–136. doi: 10.1007/s40429-020-00305-z

Mortelmans, D. (2019). Analyzing qualitative data using NVivo. H. Bulckden, M. Puppis, K. Donders, and L. AudenhoveVan The Palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research, United States Springer International Publishing 435–450.

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S., and Prinstein, M. J. (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: part 1—a theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 21, 267–294. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x

Niemi, H. M., and Kousa, P. (2020). A case study of students' and teachers' perceptions in a finish high school during the COVID pandemic. Int. J. Technol. Educat. Sci. 4, 352–369. doi: 10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.167

Oguafor, I. V., and Nevzat, R. (2023). “We are captives to digital media surveillance” Netizens awareness and perception of social media surveillance. Informat. Develop. doi: 10.1177/02666669231171641

Oliveira, T., Araujo, B., and Tam, C. (2020). Why do people share their travel experiences on social media? Tour. Manag. 78:104041. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104041

Pangrazio, L., and Sefton-Green, J. (2021). Digital rights, digital citizenship and digital literacy: what’s the difference? J. New Approach. Educat. Res. 10, 15–27. doi: 10.7821/naer.2021.1.616

Papacharissi, Z., and Mendelson, A. (2011). “Toward a new (er) sociability: uses, gratifications and social capital on Facebook” in Media perspectives for the 21st century, (Ed.) S. Papathanassopoulos (London: Routledge), 212–230.

Park, C. H., and Kim, Y. J. (2013). Intensity of social network use by involvement: a study of young Chinese users. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 8, 22–33. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v8n6p22

Pelletier, M. J., Krallman, A., Adams, F. G., and Hancock, T. (2020). One size doesn’t fit all: a uses and gratifications analysis of social media platforms. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 14, 269–284. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-10-2019-0159

Plume, C. J., and Slade, E. L. (2018). Sharing of sponsored advertisements on social media: a uses and gratifications perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 20, 471–483. doi: 10.1007/s10796-017-9821-8

Ranzini, G., Newlands, G., and Lutz, C. (2020). Sharenting, peer influence, and privacy concerns: a study on the Instagram-sharing behaviors of parents in the United Kingdom. Social Media+ Society 6, 205630512097837–205630512097813. doi: 10.1177/2056305120978376

Raza, S. A., Qazi, W., Umer, B., and Khan, K. A. (2020). Influence of social networking sites on life satisfaction among university students: a mediating role of social benefit and social overload. Health Educ. 120, 141–164. doi: 10.1108/HE-07-2019-0034

Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., and Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 3, 133–148. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016

Sarmiento, I. G., Olson, C., Yeo, G., Chen, Y. A., Toma, C. L., Brown, B. B., et al. (2018). How does social media use relate to adolescents’ internalizing symptoms? Conclusions from a systematic narrative review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 5, 381–404. doi: 10.1007/s40894-018-0095-2

Scherr, S., and Wang, K. (2021). Explaining the success of social media with gratification niches: motivations behind daytime, nighttime, and active use of TikTok in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 124, 106893–106899. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106893

Schmuck, D., Karsay, K., Matthes, J., and Stevic, A. (2019). “Looking up and feeling down”. The influence of mobile social networking site use on upward social comparison, self-esteem, and well-being of adult smartphone users. Telemat. Inform. 42, 101240–101212. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101240

Shahzad, K., Jianqiu, Z., Hashim, M., Nazam, M., and Wang, L. (2020). Impact of using information and communication technology and renewable energy on health expenditure: a case study from Pakistan. Energy 204:117956. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.117956

Sheldon, P., Antony, M. G., and Ware, L. J. (2021). Baby Boomers' use of Facebook and Instagram: uses and gratifications theory and contextual age indicators. Heliyon 7, e06670–e06677. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06670

Sheldon, P., and Newman, M. (2019). Instagram and American teens: understanding motives for its use and relationship to excessive reassurance-seeking and interpersonal rejection. J. Soc. Med. Soc. 58, 102440–102416. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102440

Sihombing, S. (2018). Hubungan pekerjaan dan pendidikan ibu dengan pemberian ASI ekslusif di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Hinai Kiri tahun 2017. Jurnal Bidan Midwife Journal 4, 40–45.

Sihombing, L. H., and Aninda, M. P. (2022). Phenomenology of using Instagram close friend features for self disclosure improvement. Professional: Jurnal Komunikasi dan Administrasi Publik 9, 29–34. doi: 10.37676/professional.v9i1.2282

Similarweb. (2023). Top websites ranking most visited websites in the world. Available at: https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/

Singh, A., Halgamuge, M. N., and Moses, B. (2019). An analysis of demographic and behavior trends using social media: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. (Eds.) N. Dey, S. Borah, R. Babo, A. S. Ashour. London: Elsevier.

Soroya, S. H., Farooq, A., Mahmood, K., Isoaho, J., and Zara, S. E. (2021). From information seeking to information avoidance: understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Inf. Process. Manag. 58, 1–16.

Spottswood, E. L., and Wohn, D. Y. (2020). Online social capital: recent trends in research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 36, 147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.031

Sun, Y., Graham, T., and Broersma, M. (2022). Complaining and sharing personal concerns as political acts: how everyday talk about childcare and parenting on online forums increases public deliberation and civic engagement in China. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 19, 214–228. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2021.1950096

Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Kaur, P., Zafar, N., and Alrasheedy, M. (2019). Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 51, 72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.026

Talwar, S., Dhir, A., Singh, D., Virk, G. S., and Salo, J. (2020). Sharing of fake news on social media: application of the honeycomb framework and the third-person effect hypothesis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 57, 102197–102111. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102197

Taylor, D. G. (2020). Putting the “self” in selfies: how narcissism, envy and self-promotion motivate sharing of travel photos through social media. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 37, 64–77. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2020.1711847

Tellis, G. J., MacInnis, D. J., Tirunillai, S., and Zhang, Y. (2019). What drives virality (sharing) of online digital content? The critical role of information, emotion, and brand prominence. J. Mark. 83, 1–20. doi: 10.1177/0022242919841034

Thomas, L., Orme, E., and Kerrigan, F. (2020). Student loneliness: the role of social media through life transitions. Comput. Educ. 146, 103754–103711. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103754

Thompson, N., Wang, X., and Daya, P. (2019). Determinants of news sharing behavior on social media. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 60, 593–601. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2019.1566803

Tifferet, S., and Vilnai-Yavetz, I. (2018). Self-presentation in LinkedIn portraits: common features, gender, and occupational differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 80, 33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.013

Tombul, I., and Sarı, G. (2021). Transformation of self presentation in virtual space: created realities on Instagram. İletişim Kuram ve Araştırma Dergisi 2021, 93–108. doi: 10.47998/ikad.852841

Trepte, S. (2021). The Social media privacy model: privacy and communication in the light of Social media affordances. Commun. Theory 31, 549–570. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtz035

Ugwudike, P., Lavorgna, A., and Tartari, M. (2023). Sharenting in digital society: exploring the prospects of an emerging moral panic. Deviant Behav., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2023.2254446

Uluç, G., and Yarcı, A. (2017). Culture of social media. The Journal of Dumlupınar University Social Sciences Institute 52, 88–102.

Vaast, E., and Kaganer, E. (2013). Social media affordances and governance in the workplace: an examination of organizational policies. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 19, 78–101. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12032

Vaterlaus, J. M., and Winter, M. (2021). TikTok: an exploratory study of young adults’ uses and gratifications. Soc. Sci. J. 1-20, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/03623319.2021.1969882

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., Massar, K., Täht, K., and Kross, E. (2020). Social comparison on social networking sites. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 36, 32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.002

Verswijvel, K., Walrave, M., Hardies, K., and Heirman, W. (2019). Sharenting, is it a good or a bad thing? Understanding how adolescents think and feel about sharenting on social network sites. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 104, 104401–104410. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104401

Vilnai-Yavetz, I., and Tifferet, S. (2015). A picture is worth a thousand words: segmenting consumers by facebook profile images. J. Interact. Mark. 32, 53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2015.05.002

Wang, J. L., Jackson, L. A., Wang, H. Z., and Gaskin, J. (2015). Predicting social networking site (SNS) use: personality, attitudes, motivation and internet self-efficacy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 80, 119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.016

Wang, J., Wang, H., Gaskin, J., Hawk, S., and Wang, J. (2017). The mediating roles of upward social comparison and self-esteem and the moderating role of social comparison orientation in the association between social networking site usage and subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 8, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg

We Are Social (2021). DIGITAL 2021 your ultimate guide to the evolving digital world. Available at: https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2021/01/digital-2021-uk/

We Are Social The changing world of digital in 2023. (2023). Available at: https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2023/01/the-changing-world-of-digital-in-2023/

Weeks, B. E., and Holbert, R. L. (2013). Predicting dissemination of news content in social media: A focus on reception, friending, and partisanship. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 90, 212–232.

Whelan, E., Najmul Islam, A. K. M., and Brooks, S. (2020). Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach. Internet Res. 30, 869–887. doi: 10.1108/INTR-03-2019-0112

Whiting, A., and Williams, D. (2013). Why people use social media: a uses and gratifications approach. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 16, 362–369. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2013-0041

Yıldırım, A., and Şimşek, H. (2000). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri. Ankara: Seçkin Yayınları.

Young, R., Len-Ríos, M., and Young, H. (2017). Romantic motivations for social media use, social comparison, and online aggression among adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 75, 385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.021

Keywords: posts, social media, social media posts, psychological reasons for posting, sociological reasons for posting

Citation: Yaman F (2023) Why do people post when they or others are under risk or threat? Sociological and psychological reasons. Front. Psychol. 14:1191631. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1191631

Edited by:

An-Jin Shie, Huaqiao University, ChinaReviewed by:

Carol Nash, University of Toronto, CanadaHiroyuki Enoki, Hiroshima International University, Japan

Copyright © 2023 Yaman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fatih Yaman, Zi55YW1hbkBhbHBhcnNsYW4uZWR1LnRy

Fatih Yaman

Fatih Yaman