- 1Xingzhi College, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China

- 2College of Foreign Languages, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China

Academic engagement plays an undeniable role in students’ leaning outcome. Therefore, identifying the influential antecedents of promoting students’ academic engagement is extremely crucial. Despite previous empirical studies have delved into the part played by several student-related and teacher-related factors in triggering Chinese students’ academic engagement, the exploration on the roles of teacher support and teacher–student rapport is still scant. Thus, this study attempts to concentrate on the influence of teacher support and teacher–student rapport on undergraduate students’ academic engagement in China. Three scales of the questionnaire—one each for teacher’s support, student-teacher rapport, and the level of academic engagement—were completed by a total of 298 undergraduate students. Spearman Rho test was adopted to detect the correlations between the variables. Following that, multiple regression analysis was used to estimate the predictive power of the dependent variables. The result found that teacher support and teacher–student rapport exert a tremendous influence on boosting Chinese students’ academic engagement. The leading implications and future directions are also presented.

1. Introduction

Students’ academic engagement is considered to be a crucial component to positive academic behaviors (Peng, 2021), social, or extracurricular activities (Snijders et al., 2020) in the educational context (Jiang and Zhang, 2021), especially for teenagers who are confronted with emerging challenges and academic needs (Geng et al., 2020). Engagement is acclaimed as a state of greater focus and active participation in which involvement is not only cognitive, but also social, behavioral, and emotional (Philp and Duchesne, 2016). Students who are actively engaged in their learning experiences are found to show energy, flexibility, and positive emotions, which raises their likelihood of academic performance, positive adolescent development results, and positive instructor attention (Skinner et al., 2008; Oga-Baldwin and Nakata, 2017; Quin, 2017; Wang, 2022). More specifically, high levels of learner engagement have been evidenced to be correlated with an array of optimistic academic performance, including enhanced academic tenacity, dedication, academic desires, fulfillment, increased mental health, low levels of student boredom, alienation, degree completion, dropout rates, and reduced high-risk behaviors (Snijders et al., 2020; Hiver et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the predictors of students’ academic engagement have remained unknown (Wang, 2022).

In light of this, extensive empirical studies investigating student engagement and its potential antecedents have been conducted. As an instance, in examining the effects of second language learning (L2) enjoyment and academic motivation on Chinese students’ participation in English as a foreign language (EFL) classes, Wang (2022) discovered that both factors exerted a significant influence on Chinese students’ academic engagement. More specifically, the more academic engagement students demonstrate, the higher the level of L2 enjoyment and academic enthusiasm they possess. In addition, existing studies of teachers’ instructional roles have focused on how elements associated to teachers can help enhance students’ active engagement in their academic study, including teacher caring behavior and teacher praise (Peng, 2021; Sun, 2021; Derakhshan et al., 2022), teacher stroke (Yuan, 2022), and teachers’ teaching style (Jiang and Zhang, 2021). However, according to Sun and Shi (2022), previous research have not definitely highlighted the influencing mechanisms of teacher support and teacher–student rapport as two significant teacher-related factors on academic engagement. That is to say, it has remained challenging to figure out the amount to which teacher support and student-teacher rapport can foster Chinese students’ academic engagement. The current research endeavors to investigate the impact of teacher support and teacher–student rapport on Chinese students’ academic engagement so as to address this need.

Teacher support, as a potential driver of academic engagement, pertains to “the extent to which learners believe their teachers value and seek to establish personal relationships with them” (Chong et al., 2018, p. 3). The extant literature highlighted the influence of teachers’ behavior supports on students’ cognitive, affective and social learning behaviors (Farmer et al., 2011) as well as students’ learning beliefs and approaches (Davis, 2003). An empirical study conducted by Alrashidi et al. (2016) indicated that one strategy to strengthen and improve students’ proactive engagement in academic and school-related activities is through teacher support. According to Liu et al. (2021), teacher support may be incredibly crucial to middle school students and has an enormous impact on students’ motivational beliefs. Hence, teacher assistance is vital in elevating middle school students’ creative self-efficacy in academic settings. Similarly, Sun and Shi (2022) advanced that Chinese students’ affective learning can be strongly impacted by their teachers, therefore EFL learners who get consistent help and support are more likely to achieve good learning results.

Another teacher-related factor that may influence students’ academic engagement is teacher–student rapport. In terms of educational psychological context, it is deemed as the trusting relationship which can connect teachers and students in a certain emotional atmosphere and experience and realize the transmission and communication of emotional information in numerous positive interpersonal interactions (Derakhshan et al., 2022). As stated by Skinner et al. (2008), academic engagement, concentration in the classroom, love of the school, and expectations for academic success are all strongly correlated with the quality of student-teacher connections in the form of loving, encouraging alliances. Besides, Quin (2017) elucidated that teacher–student relationships both directly and indirectly influenced multiple indicators of students’ active learning engagement. It’s conceivable that good teacher–student relationships will stimulate students’ desire to learn. Similarly, Xie and Derakhshan (2021) also delineated that an array of desirable students’ academic outcomes, such as active learning engagement behaviors, are strongly facilitated by positive teacher–student interpersonal relationships.

Acknowledging the utmost important of teacher support and student-teacher relationship in pedagogical dimensions (Sadoughi and Hejazi, 2021; Shen and Guo, 2022; Sun and Shi, 2022), a handful of investigations have been made to achieve their desired outcomes (e.g., Pitzer and Skinner, 2017; Lei et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021; Affuso et al., 2022; Sun and Shi, 2022). Yet, there has not been much focus on how these constructs can enhance students’ academic engagement. Moreover, grounded on the existing literature, we assume that few empirical studies have simultaneously conducted on these two teacher-related factors to identify their effects on enhancing Chinese students’ academic engagement. By inspecting the importance of teacher support and teacher–student rapport in promoting Chinese students’ academic engagement, this investigation attempts to eliminate the aforementioned gaps.

2. Literature review

2.1. Teacher support

Teachers exert a significant influence on students’ cognitive, affective, and social learning behaviors, which considerably affects the quality of their learning experiences (Pan and Chen, 2021). Consequently, in the classroom, teachers are pivotal in the dissemination of knowledge, instruction, and development of students’ academic performance (Chong et al., 2018). As shown by self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2020), teacher support signifies that teachers proactively address students’ three core psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. As reported in previous studies (Lei et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021; Sadoughi and Hejazi, 2022; Wu and Yang, 2022), teacher support, as a multidimensional construct, can be classified as academic support, emotional support, and competence support, appraisal support, and instrumental support etc. Academic support refers to students’ belief that their instructors care about what they have learned, how much they have learned, and how they can help them learn (Liu et al., 2021; An et al., 2022; Wu and Yang, 2022). Emotional support is marked by compassion, kindness, respect, inspiration, and care (Utvær et al., 2022). Teachers’ remarks, judgments, and evaluations of students’ performance, together with their recommendations and suggestions, are referred to as appraisal support (Sadoughi and Hejazi, 2022). Instrumental support involves teachers’ tangible resource in terms of skills, services, time and money (Lei et al., 2018; Sadoughi and Hejazi, 2022).

2.2. Teacher–student rapport

In terms of instructional context, Rapport, generally speaking, was conceptualized as “an overall feeling between two people encompassing a mutual, trusting, and prosocial bond” (Frisby and Martin, 2010, p. 147). Further, it was described as an interrelationship formed between teachers and students in the process of education and teaching, characterized by satisfaction, connectedness, respect, and interpersonal trust (Delos Reyes and Torio, 2021). Friendship, mutual respect and appreciation, caring and delight can all be signs of rapport (Delos Reyes and Torio, 2021; Meng, 2021). According to Zhou (2021), since teacher–student rapport is a strong connection between educators and learners that allows them to collaborate in classroom settings, any emphasis on education cannot be detached from spotlighting it (Yuan, 2022). As Aldrup et al. (2018) addressed, teacher–student relationships constitute essential components of educational environments; however, even for many experienced teachers, the task of building and keeping an encouraging interpersonal relationship is extremely challenging. Considering the significance of teacher–student relationships in the educational realm, a range of researchers have proposed ways in which teachers can build a good and strong rapport with learners. According to Yang (2021), when students receive positive feedback, it appears to increase their enthusiasm for learning and makes learning contexts much more pleasurable, leading in a willing to interact between teachers and students. In a similar vein, Santana (2019) proposed seven methods which are conduce to build positive rapport with learners, such as understanding the students, encouraging the students and caring, communicating effectively, being approachable, being respectful and respected, being authentic, and using humor.

2.3. Academic engagement

Students’ academic engagement is considered as “the time and energy students devote to educationally sound activities inside and outside of the classroom, and the policies and practices that institutions use to induce students to take part in these activities” (Kuh, 2003, p. 25). Further, Skinner et al. (2009) proposed that engagement pertains to “the quality of a student’s connection or involvement with the endeavor of schooling and hence with the people, activities, goals, values, and place that compose it” (p. 494). When it comes to the language learning context, Hiver et al. (2021) defined academic engagement as “how actively involved a student is in a learning task and the extent to which that physical and mental activity is goal-directed and purpose-driven” (p. 3). Finally, taking all above definitions in consideration, academic engagement is conceptualized by Alrashidi et al. (2016) as “a positive and proactive term that captures students’ quality of participation, investment, commitment, and identification with school and school-related activities to enhance students’ performance” (p. 42). Despite the growing attention in student academic engagement (Brint et al., 2008; Skinner et al., 2008; Peng, 2021; Wang, 2022), the term “academic engagement” is interpreted in an array of ways and is occasionally employed interchangeably with terms like “school engagement,” “student engagement in school,” “engagement in class,” and “engagement in schoolwork” (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Fredricks et al., 2004; Darr, 2012;Alrashidi et al., 2016; Peng, 2021). Likewise, the numbers and sorts of elements that make up this structure have been the focus of a protracted argument (Alrashidi et al., 2016; Peng, 2021). For example, Fredricks et al. (2004) categorized student academic engagement into three components (i.e., behavioral, emotional, and cognitive), whereas Reeve and Tseng (2011) divided this construct into four main dimensions (i.e., behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and agentic) (Oga-Baldwin, 2019). According to Pedler et al. (2020), student engagement is generally viewed as a ductile, multidimensional construct that incorporates the three aspects of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement. The term “behavioral engagement” refers to the visible academic performance and wanting to share tasks and activities that are assessed through observable educational acts such as: student desirable outcome, greater involvement, endeavor to concentrate on practices, willingness to participate in class discussions, desire to contribute in educational activities (Sun, 2021). Students’ emotional states throughout educational process (such as curiosity, delight, passion, boredom, happiness, sadness, and anxiety) alongside their sense of identification and relatedness to counterparts, educators, and the school are all considered to be part of emotional engagement (Darr, 2012; Lawson and Lawson, 2013; Geng et al., 2020). Cognitive engagement entails the way learners proactively engage about the subject they are learning by elucidating meanings, drawing connections, addressing problems, memorizing concepts, and responding to questions (Oga-Baldwin and Nakata, 2017). According to Weyns et al. (2018) and Skinner et al. (2008), teacher support and teacher–student rapport were demonstrated to foretell academic engagement as two external factors cultivating optimistic child development at school. However, few studies have considered both teacher support and teacher–student rapport as factors that enhance students’ academic engagement. Additionally, grounded on the existing literature, few investigations have assessed the simultaneous role of teacher support and teacher–student rapport. The present study intended to close this gap by exploring the effect of teacher support and teacher–student rapport on academic engagement. Informed by the above discussed, two overarching research questions were generated:

(1) What are the relations between academic engagement, teacher support, and teacher–student rapport among Chinese students?

(2) Do teacher support and teacher–student rapport significantly enhance Chinese students’ academic engagement?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

A total of 305 undergraduate students in a comprehensive university in China, aged from 18 to 22 (average age = 20, SD = 1.52), were enrolled to participate in the study using the convenience sampling strategy. Nevertheless, owing to incomplete questionnaires, 7 students’ data were deleted. Thus, the final sample was 298, consisting of 104 (34.9%) males and 194 (65.1%) females. Participants varied regarding grade, ranging from freshmen to seniors. Before collecting the data, participants were all informed of the research purpose and of their voluntary participation. Meanwhile, they received reassurances that their answers and personal data would be treated in strict confidence.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Teacher support

The questionnaire scale of teacher support, adapted from Babad (1990) and Ouyang (2005), served to gauge how an instructor is perceived by Chinese undergraduates as being supportive. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to remove garbage items and thereby this scale of teacher support totally involved 18 items of three dimensions: academic support (6 items, e.g., “When we are unable to answer a question, the instructor frequently repeats the explanation”), emotional support (6 items, e.g., “The instructor usually supports and cares about our academic performance”), and competence support (6 items, e.g., “My teacher frequently suggests that I take part in various competitions”). Each item was assessed on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated better perceptions of teacher support. The Cronbach’s α value of teacher support scale was 0.95, indicating good reliability.

3.2.2. Teacher–student rapport

The Wilson et al. (2010)‘s “Professor-Student Rapport Scale (P-SRS)” was modified to measure students’ perceptions on the quality of their relations with teachers. The scale encompasses 6 items, each of which is scored on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). One sample item is “The teacher encourages students’ questions and comments.” In this study, the Cronbach’s α value of this scale was 0.93, showing good reliability.

3.2.3. Academic engagement

Reeve and Tseng’s (2011) Academic Engagement Scale and Wang et al. (2016) The Math and Science Engagement Scales were both modified to measure academic engagement. Some items were changed and produced in response to the realistic situation. EFA was conducted to spot and remove unrelated items, thus remaining 18 items. This six-point Likert scale involves three sub-scales: behavioral engagement (6 items, e.g., “I actively answer the questions asked by the teacher in class”), emotional engagement (6 items, e.g., “I eagerly await English class”), and cognitive engagement (6 items, e.g., “No matter how difficult the learning content is, I will not give up and try to understand them”). With the Cronbach’s α value of 0.96, a good reliability of this scale was found in the present study.

3.3. Procedure and data analysis

To begin with, the above-mentioned three scales were distributed to the participants on the spot during lesson intervals and collected immediately after completion. Moreover, all respondents received instructions on how to answer to the survey questions, which heightened the accuracy and credibility of responses. After completing the procedure of data collection, the respondents’ answers were further reviewed to ensure the reliability of the collected data. Afterward, the SPSS 21.0 was adopted to conduct Spearman correlation analyses to assess the relationships between teacher support, teacher–student rapport, and academic engagement. At last, to ascertain how much of the variance in Chinese students’ academic engagement may be ascribed to teacher support and teacher–student rapport, multiple regression analyses were carried out.

4. Results

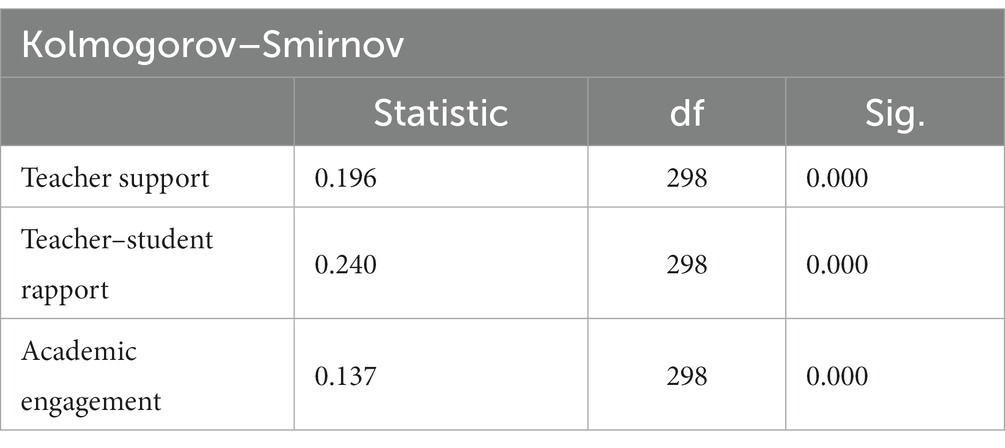

First of all, the normality of the gathered data was verified utilizing Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The results are shown in Table 1.

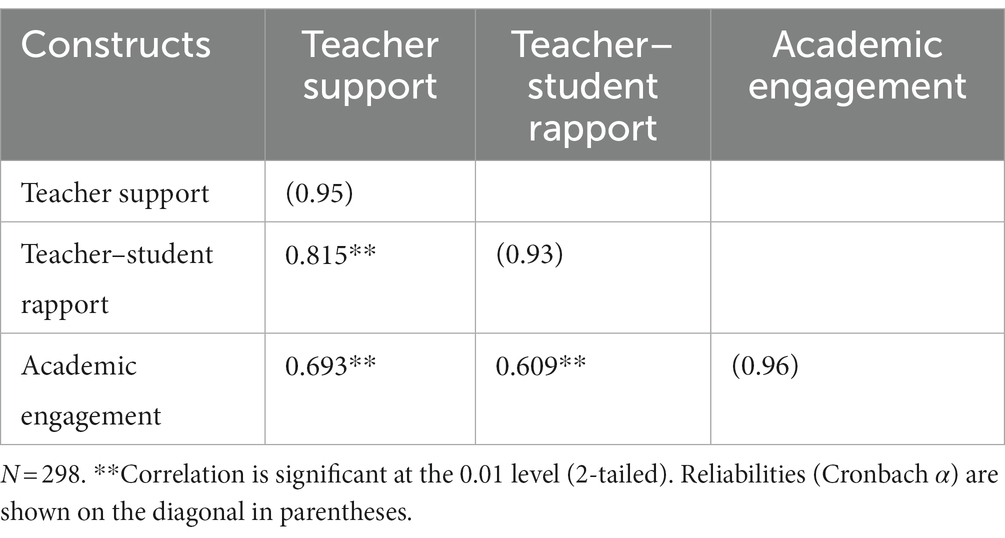

As depicted in Table 1, the data distribution of all of the three questionnaires showed abnormal. Therefore, non-parametric tests were needed to calculate possible associations between variables. The relations between teacher support, teacher–student rapport, and academic engagement were examined using the Spearman correlation test. Table 2 showed the results of the Spearman correlation test.

As Table 2 delineated, there is a strong and largely favorable association between teacher support and teacher–student rapport (r = 0.815, p < 0.001). The results of Spearman correlation indicated a significant relationship (r = 0.693, p < 0.001) between academic engagement and teacher support. Academic engagement was also very closely related to teacher–student relationship (r = 0.609, p < 0.001). That is to say, the higher the level of teacher support and teacher–student rapport predicts the greater degree of academic engagement. Afterwards, to investigate the role of teacher support and teacher–student rapport in influencing academic engagement in Chinese students, multiple regression analysis was implemented. Table 3 displayed the results of the regression analysis.

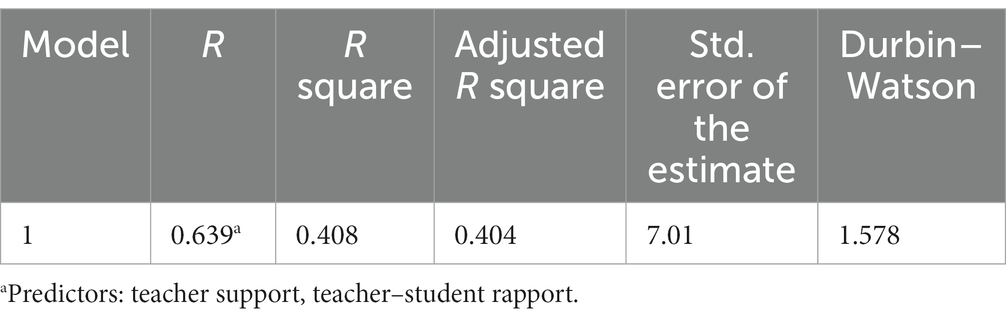

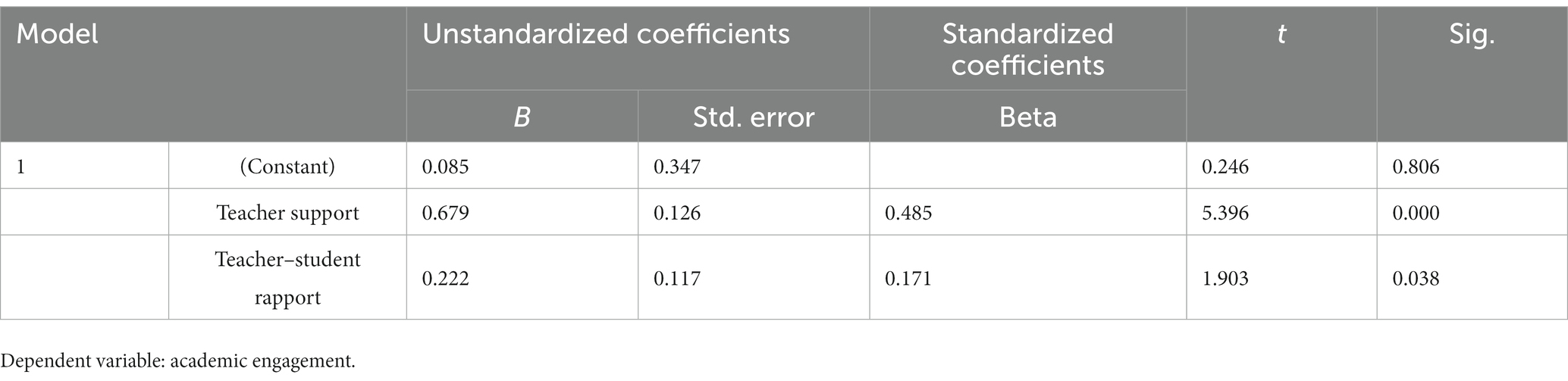

Based on Table 3, teacher support and student–teacher rapport account for 40.8% of the variation in Chinese students’ academic engagement. Beta coefficient table was subsequently conducted to discern the results of independent variables (teacher support and teacher–student rapport) contributing to enhanced academic engagement. From the beta column (Table 4), the beta coefficient of teacher support was 0.171 with a statistical significance (p < 0.05), indicating the positive stimulating effect of teacher–student rapport on students’ academic engagement. Furthermore, the beta coefficient of teacher support was 0.485 with a statistical significance (p < 0.001), which contributed the most to the improvement of Chinese students’ academic engagement. In other words, it was discovered that teacher support was a great indicator of Chinese students’ academic engagement.

5. Discussion

The primary intention of this study was to shed light on the degree to which Chinese students’ academic engagement is correlated with teacher support and teacher–student rapport. The Spearman correlation test unveiled, firstly, a straightforward and powerful correlation between teacher support and academic engagement, and secondly, a positive association of teacher–student rapport and academic engagement. On the obvious association between academic engagement and support from teachers, this finding is in line with the study of Sadoughi and Hejazi (2021), which identified teacher support could have a direct and positive impact on EFL learners’ academic engagement. It is noteworthy that this result is also consistent with that of Zhou et al. (2022), who found that all three dimensions of teacher support were favorably correlated with students’ learning engagement. Just as the theory of self-determination concentrating largely on how environments influence people’s psychological needs (Jeno et al., 2019), as an important part of social support, teacher support helps cultivate students’ autonomy and encourages students to explore independently, so that they can actively face challenges in learning. In addition, teacher support promotes students’ internal motivation and enhances students’ concentration in the learning process, thus giving rise to a higher level of academic engagement. Regarding the favorable correlation between teacher–student rapport and academic engagement, this lends support to Engels et al. (2021), who stated warm and intimate teacher–student relationships contribute to adolescents’ school engagement. This also accords with the previous study from Zhou (2021), who summarized that rapport between teachers and learners is desirable to arouse students’ academic engagement. This result also further reinforces what Xie and Derakhshan (2021) have put emphasis on the significance of teacher–student rapport, namely, when an effective teacher–student rapport is established, positive student outcomes, including L2 engagement, are on the horizon.

Besides, this study attempted to ascertain the worth of teacher support and teacher–student rapport in fostering students’ academic engagement. That is to say, this study was to investigate how much teacher support and teacher–student rapport exert influence on the enhancement of students’ academic engagement. As illustrated by the results of the regression analysis, teacher support has proven to be a robust predictor of Chinese students’ academic engagement. Chinese students’ academic engagement is positively affected by teacher support, as students who are capable of receiving adequate and prompt assistance from their teachers are prone to enjoy learning and are inclined to put forth more time and effort into it (Zhao and Yang, 2022). Such an explanation aligns with An et al. (2022) who uncovered a strikingly remarkable correlation between teacher support and academic engagement in a technology-related educational setting. To be specific, students will get involved in learning deeper if teachers provide them with more emotional and behavioral support in contexts that contain technology. This finding also echoes the idea of Ruzek et al. (2016), who posited that teacher behaviors, such as offering timely academic and emotionally caring feedback to students, complimenting and respecting students, are notably linked to students’ academic engagement, which contributed to an increase in students’ desire to be engaged in learning activities. As with teacher support, teacher–student rapport is a powerful antecedent to students’ engagement as well. This is in accord with the finding of Cooper (2014) study, who stated that active relationships between teachers and students can be a crucial resource for underpinning students’ academic endeavors as well as stimulating students to become deeper engaged in their studies.

6. Conclusion

The primary aim of the current study was to figure out how much academic engagement among Chinese students is influenced by teacher support and teacher–student rapport. Multiple regression analysis and Spearman Rho correlation analysis indicated that teacher support and teacher–student rapport could dramatically boost Chinese students’ academic engagement. Therefore, students are more probable to be involved in a range of learning tasks and put efforts into them if they get enough support and encouragement from teachers and develop friendly relationships with them. This result does seem to be impressively profound for educators and teachers, especially those who are now engaged in teaching in EFL environments. That is because notwithstanding the indispensable role of teacher–student rapport in any learning setting, the task of establishing and upholding a positive interpersonal relationship can be a daunting challenge, even for many well-prepared teachers. Given the findings of this investigation, teachers are encouraged to be supportive of their students as much as possible and to develop a friendly and harmonious relationship with them so that they can be more engaged in the learning process. Considering the contribution of teacher–student rapport in increasing students’ academic engagement, teachers can undertake diverse initiatives, including giving timely positive feedback to students, listening carefully and pondering on learners’ voices, so as to get the students to be engaged in the classroom. Given that teacher support significantly improves students’ academic engagement, teachers entail to provide student with constant support and assistance.

In spite of research implications found, several limitations exist in this study. Firstly, the cross-sectional quantitative approach was applied merely to conduct this exploration, which may give rise to a potential bias. Upcoming studies are suggested to utilize longitudinal method to obtain more inclusive results. Secondly, in this study, the research sample is comparatively small. Hence, further studies can adopt large-scaled survey to further assess the results. Thirdly, it needs to be highlighted that contextual factors including gender, age, and educational background were neglected and ought to be inspected in ongoing studies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XP conceived, designed, and executed the study, collected the data, wrote the manuscript, and revised the final version of the manuscript. YY analyzed the data and participated in writing and revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Project of the 2021 Teaching Reform of Xingzhi College, Zhejiang Normal University (Grant no. ZC303921073).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Affuso, G., Zannone, A., Esposito, C., Pannone, M., Miranda, M. C., Angelis, G. D., et al. (2022). The effects of teacher support, parental monitoring, motivation and self-efficacy on academic performance over time. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 38, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s10212-021-00594-6

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, K., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., and Trautwein, U. (2018). Student misbehavior and teacher well-being: testing the mediating role of the teacher–student relationship. Learn. Instr. 58, 126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.006

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., and Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: an overview of its definitions, dimensions, and major conceptualizations. Int. Educ. Stud. 9, 41–52. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n12p41

An, F., Yu, J., and Xi, L. (2022). Relationship between perceived teacher support and learning engagement among adolescents: mediation role of technology acceptance and learning motivation. Front. Psychol. 13:992464. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992464

Babad, E. (1990). Measuring and changing teachers’ differential behavior as perceived by students and teachers. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 683–690. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.683

Brint, S., Cantwell, A. M., and Hanneman, R. A. (2008). The two cultures of undergraduate academic engagement. Res. High. Educ. 49, 383–402. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9090-y

Chong, W. H., Liem, G. A. D., Huan, V. S., Phey Ling Kit, P. L., and Ang, R. P. (2018). Student perceptions of self-efficacy and teacher support for learning in fostering youth competencies: roles of affective and cognitive engagement. J. Adolesc. 68, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.002

Cooper, K. S. (2014). Eliciting engagement in the high school classroom: a mixed-methods examination of teaching practices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 51, 363–402. doi: 10.3102/0002831213507973

Darr, C. W. (2012). Measuring student engagement: the development of a scale for formative use. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 707–724). Springer, Boston, MA.

Davis, H. A. (2003). Conceptualizing the role and influence of student–teacher relationships on children’s social and cognitive development. Educ. Psychol. 38, 207–234. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3804_2

Delos Reyes, R. D. G., and Torio, V. A. G. (2021). The relationship of expert teacher–learner rapport and learner autonomy in the CVIF-dynamic learning program. Asia-Pacific Edu. Res. 30, 471–481. doi: 10.1007/s40299-020-00532-y

Derakhshan, A., Dolinski, D., Zhaleh, K., Enayat, M. J., and Fathi, J. (2022). A mixed-methods cross-cultural study of teacher care and teacher–student rapport in Iranian and polish university students’ engagement in pursuing academic goals in an L2 context. System 106:102790. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102790

Engels, M. C., Spilt, J., Denies, K., and Verschueren, K. (2021). The role of affective teacher–student relationships in adolescents’ school engagement and achievement trajectories. Learn. Instr. 75:101485. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101485

Farmer, T. W., Lines, M. M., and Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: the role of teachers in children’s peer experiences. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

Frisby, B. N., and Martin, M. M. (2010). Instructor–student and student–student rapport in the classroom. Commun. Educ. 59, 146–164. doi: 10.1080/03634520903564362

Geng, L., Zheng, Q., Zhong, X. Y., and Li, L. Y. (2020). Longitudinal relations between students’ engagement and their perceived relationships with teachers and peers in a Chinese secondary school. Asia-Pacific Edu. Res. 29, 171–181. doi: 10.1007/s40299-019-00463-3

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., and Wu, J. (2021). Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res., Early Access. doi: 10.1177/13621688211001289

Jeno, L. M., Adachi, P. J. C., Grytnes, J., Vandvik, V., and Deci, E. L. (2019). The effects of m-learning on motivation, achievement and well-being: a self-determination theory approach. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 669–683. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12657

Jiang, A. L., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). University teachers’ teaching style and their students’ agentic engagement in EFL learning in China: a self-determination theory and achievement goal theory integrated perspective. Front. Psychol. 12:704269. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704269

Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we’re learning about student engagement from NSSE: benchmarks for effective educational practices. Change Magaz. Higher Learn. 35, 24–32. doi: 10.1080/00091380309604090

Lawson, M. A., and Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Rev. Educ. Res. 83, 432–479. doi: 10.3102/0034654313480891

Lei, H., Cui, Y., and Chiu, M. (2018). The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: a Meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 8:2288. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02288

Liu, X., Gong, S., Zhang, H., Yu, Q., and Zhou, Z. (2021). Perceived teacher support and creative self-efficacy: the mediating roles of autonomous motivation and achievement emotions in Chinese junior high school students. Think. Skills Creat. 39:100752. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100752

Meng, Y. (2021). Fostering EFL/ESL students’ state motivation: the role of teacher–student rapport. Front. Psychol. 12:754797. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.754797

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q. (2019). Acting, thinking, feeling, making, collaborating: the engagement process in foreign language learning. System 86:102128. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.102128

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q., and Nakata, Y. (2017). Engagement, gender, and motivation: a predictive model for Japanese young language learners. System 65, 151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.01.011

Ouyang, D. (2005). A research on the relation among teachers’ expectation, self-conception of students’ academic achievement, students’ perception of teacher’s behavioral supporting and the study achievement. Dissertation/Master’s Thesis. Nanning: Guangxi Normal University.

Pan, X., and Chen, W. (2021). Modeling teacher supports toward self-directed language learning beyond the classroom: technology acceptance and technological self-efficacy as mediators. Front. Psychol. 12:751017. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.751017

Pedler, M., Yeigh, T., and Hudson, N. (2020). The teachers’ role in student engagement: a review. Austr. J. Teacher Edu. 45, 48–62. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2020v45n3.4

Peng, C. (2021). The academic motivation and engagement of students in English as a foreign language classes: does teacher praise matter? Front. Psychol. 12:778174. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.778174

Philp, J., and Duchesne, S. (2016). Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 36, 50–72. doi: 10.1017/S0267190515000094

Pitzer, J., and Skinner, E. (2017). Predictors of changes in students’ motivational resilience over the school year: the roles of teacher support, self-appraisals, and emotional reactivity. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 41, 15–29. doi: 10.1177/0165025416642051

Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher–student relationships and student engagement. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 345–387. doi: 10.3102/0034654316669434

Reeve, J., and Tseng, M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of student engagement during learning activities. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Ruzek, E. A., Hafen, C. A., Allen, J. P., Gregory, A., Mikami, A. Y., and Pianta, R. C. (2016). How teacher emotional support motivates students: the mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learn. Instr. 42, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.004

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101860. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sadoughi, M., and Hejazi, S. Y. (2021). Teacher support and academic engagement among EFL learners: the role of positive academic emotions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 70:101060. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101060

Sadoughi, M., and Hejazi, S. Y. (2022). The effect of teacher support on academic engagement: the serial mediation of learning experience and motivated learning behavior. Curr. Psychol. Early Access. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03045-7

Santana, J. C. (2019). Establishing teacher–student rapport in an English medium instruction class. Latin Am. J. Content Lang. Integr. Learn. 12, 265–291. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2019.12.2.4

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Shen, Y., and Guo, H. (2022). Increasing Chinese EFL learners’ grit: the role of teacher respect and support. Front. Psychol. 13:880220. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.880220

Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., and Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: part of a larger motivational dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 100, 765–781. doi: 10.1037/a0012840

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., and Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of Children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 69, 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0013164408323233

Snijders, I., Wijnia, L., Rikers, R. M. J. P., and Loyens, S. M. M. (2020). Building bridges in higher education: student-faculty relationship quality, student engagement, and student loyalty. Int. J. Educ. Res. 100:101538. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101538

Sun, Y. (2021). The effect of teacher caring behavior and teacher praise on students’ engagement in EFL classrooms. Front. Psychol. 12:746871. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746871

Sun, Y., and Shi, W. (2022). On the role of teacher–student rapport and teacher support as predictors of Chinese EFL students’ affective learning. Front. Psychol. 13:856430. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.856430

Utvær, B. K., Torbergsen, H., Paulsby, T. E., and Haugan, G. (2022). Nursing students’ emotional state and perceived competence during the COVID-19 pandemic: the vital role of teacher and peer support. Front. Psychol. 12:793304. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.793304

Wang, X. (2022). Enhancing Chinese EFL students’ academic engagement: the impact of L2 enjoyment and academic motivation. Front. Psychol. 13:914682. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.914682

Wang, M., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., and Linn, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learn. Instr. 43, 16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.008

Weyns, T., Colpin, H., Laet, S. D., Engels, M., and Verschueren, K. (2018). Teacher support, peer acceptance, and engagement in the classroom: a three-wave longitudinal study in late childhood. J. Youth Adolescence. 47, 1139–1150. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0774-5

Wilson, J. H., Ryan, R. G., and Pugh, J. L. (2010). Professor–student rapport scale predicts student outcomes. Teach. Psychol. 37, 246–251. doi: 10.1080/00986283.2010.510976

Wu, S., and Yang, K. (2022). The effectiveness of teacher support for students’ learning of artificial intelligence popular science activities. Front. Psychol. 13:868623. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868623

Xie, F., and Derakhshan, A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Front. Psychol. 12:708490. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490

Yang, D. (2021). EFL/ESL students’ perceptions of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice: the impact of positive teacher–student relation. Front. Psychol. 12:755234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.755234

Yuan, L. (2022). Enhancing Chinese EFL students’ grit: the impact of teacher stroke and teacher–student rapport. Front. Psychol. 12:823280. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.823280

Zhao, Y., and Yang, L. (2022). Examining the relationship between perceived teacher support and students’ academic engagement in foreign language learning: enjoyment and boredom as mediators. Front. Psychol. 13:987554. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.987554

Zhou, X. (2021). Toward the Positive Consequences of Teacher-Student Rapport for Students’ Academic Engagement in the Practical Instruction Classrooms. Front. Psychol. 12:759785. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759785

Keywords: academic engagement, teacher support, teacher–student rapport, Chinese undergraduate students, empirical investigation

Citation: Pan X and Yao Y (2023) Enhancing Chinese students’ academic engagement: the effect of teacher support and teacher–student rapport. Front. Psychol. 14:1188507. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1188507

Edited by:

Elisabetta Sagone, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Benedetta Ragni, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyAna Fuensanta Hernandez Ortiz, University of Murcia, Spain

Amanda Rodrigues De Souza, University of La Laguna, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Pan and Yao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoquan Pan, cHhxQHpqbnUuY24=

Xiaoquan Pan

Xiaoquan Pan Yuanyuan Yao2

Yuanyuan Yao2