- 1Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 2Department of Spiritual Health, Emory University Woodruff Health Sciences Center, Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, GA, United States

Background: Compassion is considered a fundamental human capacity instrumental to the creation of medicine and for patient-centered practice and innovations in healthcare. However, instead of nurturing and cultivating institutional compassion, many healthcare providers cite the health system itself as a direct barrier to standard care. The trend of compassion depletion begins with medical students and is often attributed to the culture of undergraduate medical training, where students experience an increased risk of depression, substance use, and suicidality.

Objectives: This qualitative study aims to develop a more comprehensive understanding of compassion as it relates to undergraduate medical education. We used focus groups with key stakeholders in medical education to characterize beliefs about the nature of compassion and to identify perceived barriers and facilitators to compassion within their daily responsibilities as educators and students.

Methods: Researchers conducted a series of virtual (Zoom) focus groups with stakeholders: Students (N = 14), Small Group Advisors (N = 11), and Medical Curriculum Leaders (N = 4). Transcripts were thematically analyzed using MAXQDA software.

Results: Study participants described compassion as being more than empathy, demanding action, and capable of being cultivated. Stakeholders identified self-care, life experiences, and role models as facilitators. The consistently identified barriers to compassion were time constraints, culture, and burnout. Both medical students and those training them agreed on a general definition of compassion and that there are ways to cultivate more of it in their daily professional lives. They also agreed that undergraduate medical education – and the healthcare culture at large – does not deliberately foster compassion and may be directly contributing to its degradation by the content and pedagogies emphasized, the high rates of burnout and futility, and the overwhelming time constraints.

Discussion: Intentional instruction in and cultivation of compassion during undergraduate medical education could provide a critical first step for undergirding the professional culture of healthcare with more resilience and warm-hearted concern. Our finding that medical students and those training them agree about what compassion is and that there are specific and actionable ways to cultivate more of it in their professional lives highlights key changes that will promote a more compassionate training environment conducive to the experience and expression of compassion.

1. Introduction

Compassion, the affectionate motivation to help alleviate suffering, is crucial to the purpose, function, and structure of health systems (Lown, 2014; Sinclair et al., 2016; Cochrane et al., 2019; Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019). Neurobiologically distinct from empathy, compassion builds on the empathic concern that can arise in response to suffering and includes the motivation and intention for improving the well-being of another (Singer and Klimecki, 2014). Compassion can lead to profound benefits for the individual experiencing compassionate motivation, the recipients of compassionate actions, and to the systems that support their emergence (Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019). Moreover, patients and their families, providers, and health organizations identify compassion as a hallmark of quality care (Paterson, 2011; Sinclair et al., 2016; Cochrane et al., 2019; Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019). For patients, physician compassion is linked with improved clinical outcomes (Hojat et al., 2011; del Canale et al., 2012), greater patient satisfaction (Wang et al., 2018), and adherence to treatment (Neumann et al., 2007). Of benefit to health systems, compassionate physicians order fewer unnecessary tests and referrals (Bertakis and Azari, 2011), commit fewer major errors (West et al., 2009), and are less likely to be sued for malpractice (Moore et al., 2000). For the provider, the experience of compassion is associated with positive affect (Stellar et al., 2015), pro-social motivation (Mascaro et al., 2013), improved resilience (Klimecki et al., 2014), and has even been proposed as an antidote to burnout (Singer and Klimecki, 2014; Neff and Dahm, 2015; Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019).

Despite the beneficial qualities of compassion, the professional and organizational cultures of allopathic medicine have increasingly adopted policies and positions that create barriers to compassionate care, rather than facilitating it (Shanafelt et al., 2019). Excessive preauthorization and documentation, staff shortages, focus on relative value units and patient volume, and limited appointment lengths contribute to disturbing rates of provider/physician depression, substance abuse, and even suicide, all of which likely disturb a provider’s capacity for compassion (Sprang et al., 2007; Lancet, 2019; Shanafelt et al., 2019; The National Academy of Medicine, 2019; Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019). Moreover, even though they are buffered from the burden of clerical medicine, there is a measurable atrophy of compassion among medical students (Hojat et al., 2009). Quickly after matriculation into medical training, students exhibit similar rates of burnout, depression, substance use, and suicide as the physicians training them (Ludwig et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2016; The National Academy of Medicine, 2019; Dyrbye et al., 2021). It is imperative that deliberate steps are taken to inure future providers from the degradation of compassion and overwhelming burnout so pervasive in their chosen career path (Neumann et al., 2011). Undergraduate medical education (UME) offers a unique opportunity to operationalize compassion interventions and curricula designed to entrain sustainable compassion. Medical students spend a large portion of their training away from the bedside, in the relative safety and structure of classrooms and simulations. Additionally, compared to residents and faculty, students have limited and purposefully regulated responsibility for patient care; their primary responsibility is to learn (Liaison Committee on Medical Education, 2022). Developing the tools and skills required to maintain their compassion and resilience as they grow intimate with human suffering and the successes and failures of medicine would benefit their own well-being, the patients they serve, and the teams they will lead. Yet, despite the evidence for the value of compassion, two recent systematic reviews found that current approaches to compassion training are of limited duration, designed primarily for developing individual compassion rather than institutional, and created as adjuncts to the core curriculum rather than as an integrated, longitudinal, multi-faceted approach to compassion cultivation (Patel et al., 2019; Sinclair et al., 2021a). These approaches can be overly burdensome to students and teachers and are often less effective than curricula that incorporate a systematic culture of compassion (Michalec, 2009; Neumann et al., 2011).

We hypothesize that making compassion cultivation a central part of the content and pedagogies utilized in undergraduate medical training would produce profound benefits for medical students, those training them, and ultimately the healthcare systems and patients they serve. In order to develop a more comprehensive approach to compassion cultivation in medical training, we conducted a series of focus groups with medical students and educators to query their conceptions of compassion. We sought to identify how key stakeholders in undergraduate medical education describe compassion, as well as the factors that facilitate and inhibit the enaction of compassion in their day-to-day professional environment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study overview

To address our aim, we conducted a series of virtual (Zoom) focus groups with key stakeholders: small group advisors (SGA), medical curriculum leaders (MCL), and medical students (MS) between October 2021 and January 2022. The study was conducted in accordance with approval from our university’s institutional review board and all study participants provided informed consent.

2.2. Participants

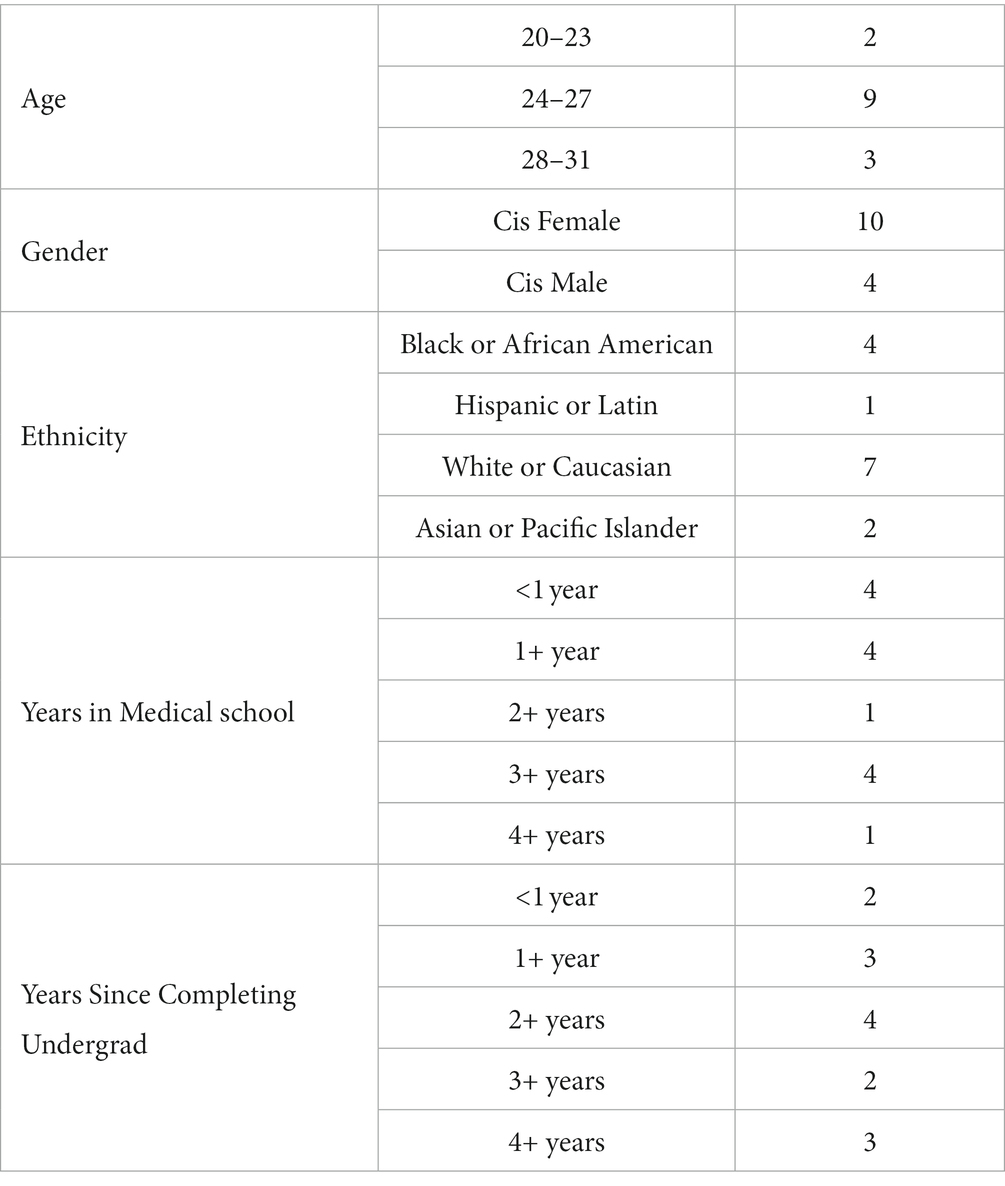

We used convenience sampling to recruit between 4 and 12 participants per focus group. To facilitate conversation and to better ensure that stakeholders felt comfortable and safe to share their responses (Ayala and Elder, 2011), focus groups were subdivided by participant role in medical education: medical students (n = 14), small group advisors (SGAs; n = 11), and medical curriculum leaders (MCLs; n = 4). SGAs planned a professional development seminar to accommodate the focus groups and MCLs were recruited by direct email. Students were recruited by listserv emails sent to all currently enrolled MD students and offered a $15 gift card for their participation. Our inclusion criteria consisted of the current school of medicine students and faculty; we had no exclusion criteria. To ensure that SGAs and MCLs felt safe to share their beliefs and to better ensure the anonymity of these small populations, we did not acquire demographic data for these groups; MS demographics data were collected by Qualtrics survey during recruitment and are summarized in Table 1.

2.3. Focus groups

Focus groups queried stakeholders’ general beliefs about compassion using an interview guide that was created prior to the focus group sessions. We asked the participants about their conceptions of the nature of compassion, whether they conceived of compassion as sustaining or draining, whether and how compassion can be cultivated, and what supports or hinders their experience of compassion in their day-to-day responsibilities. We reached saturation with available educators and held an additional focus group with students to confirm the saturation of themes.

2.4. Analysis

Focus groups were recorded, transcribed, and the transcripts were then anonymized. We used MAXQDA.20 to manage and thematically analyze the transcripts. We first familiarized ourselves with the data by reviewing the interview guide and all transcripts to generate a preliminary codebook of themes identified by researchers. Then, two researchers (CL and EB) independently used this preliminary codebook to thoroughly review the transcripts and identify any salient themes missing from the codebook, to reduce redundancy of themes, and establish any identified hierarchical grouping. After this, the entire research team discussed codes to reconcile any coding differences, to ensure concordance and reliability, and to finalize the codebook. The finalized codebook was used to generate reports in MAXQDA.20 for which the results are described below.

3. Results

3.1. Defining compassion

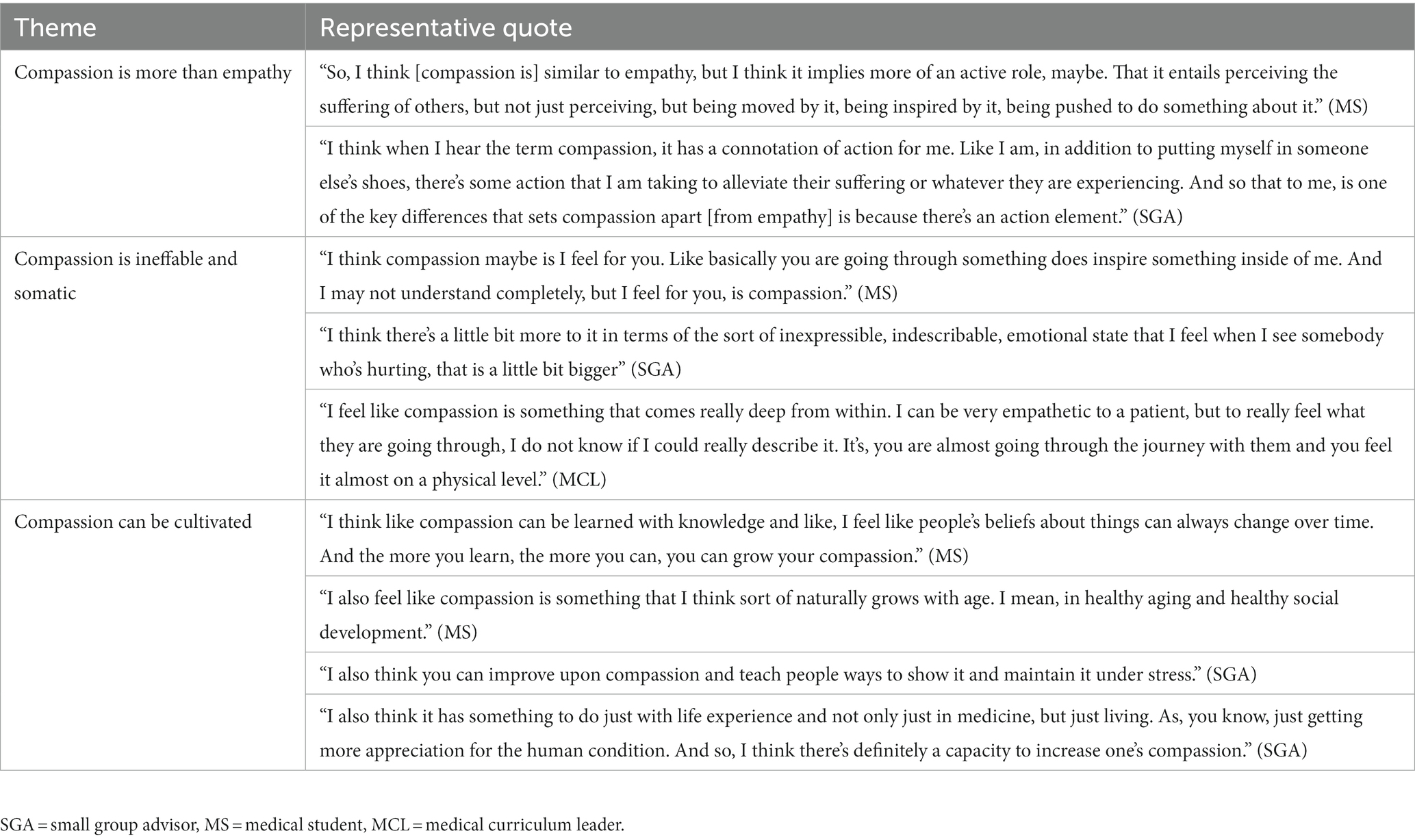

Assessing student and educator conceptions of compassion revealed striking similarities in the descriptions across the three stakeholder groups. Emergent themes included that compassion is more than empathy (themes and representative quotes found in Table 2). All stakeholder groups characterized compassion as an emotional arousal that is more than empathy and typified by motivated action to address another’s suffering. A second emergent theme was that compassion is ineffable. All stakeholder groups acknowledged a felt somatic sense of compassion that they reported could not be described by words and made the experience of compassion feel more impactful to them. A third theme was that compassion can be cultivated. There was unanimous agreement across all focus groups that compassion is not a fixed trait, but rather something that can be cultivated and grown with age and experience.

3.2. Positive influences on compassion

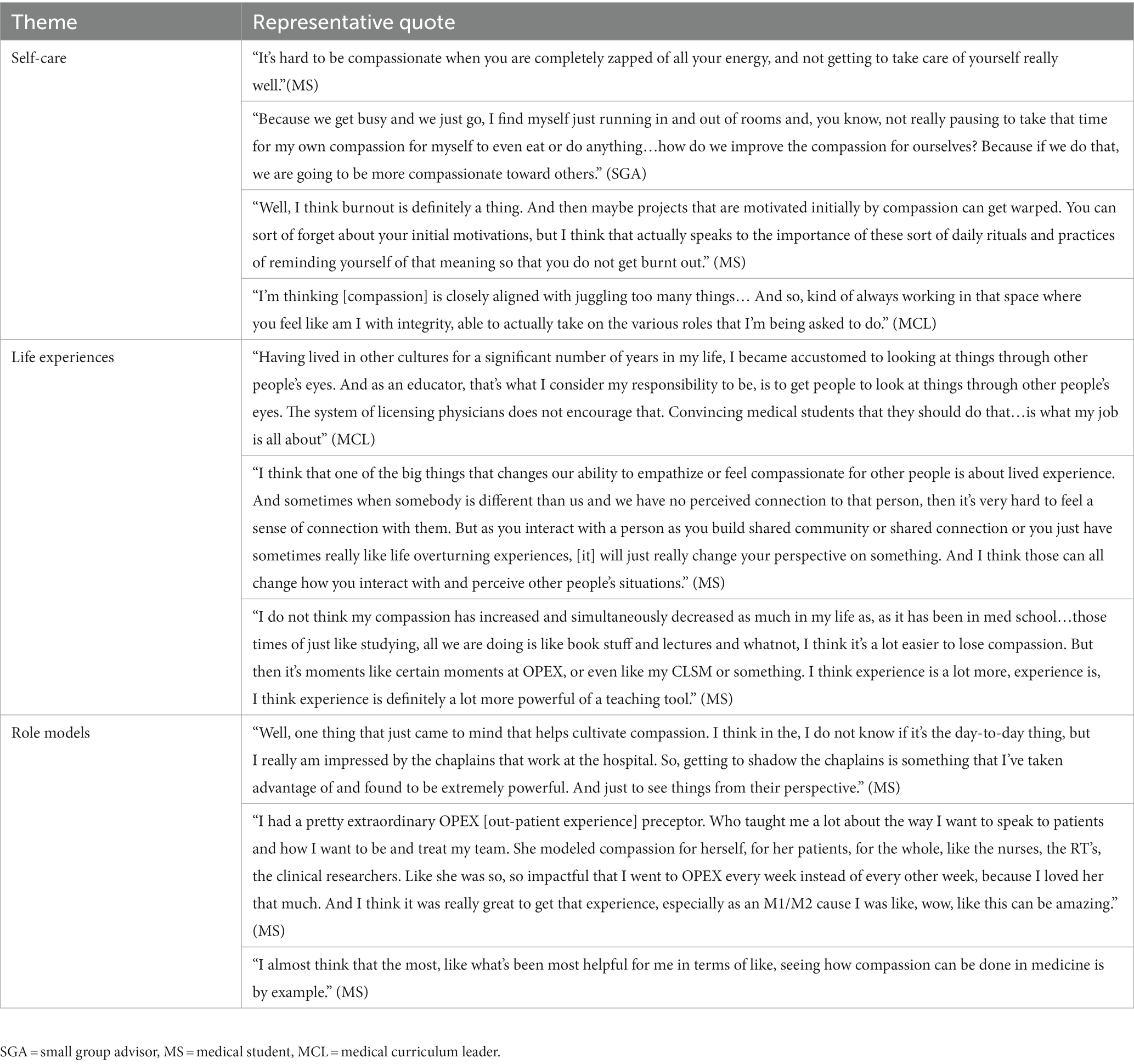

Participants identified factors that facilitate the enaction of compassion in their day-to-day professional environment (themes and representative quotes found in Table 3). Again, there was a significant overlap in answers across stakeholder groups. The importance of self-care and meeting one’s basic needs to maintain compassion emerged as a central theme in every focus group. Participants discussed self-care in terms of attending to their own needs, including adequate sleep, self-regulation, therapy, spiritual practice, and spending time with a nurturing community of colleagues and loved ones. All focus groups also identified the importance of life experiences, which exposed them to diverse people and helped build cognitive empathy for others’ perspectives, as supportive of compassion. For students, this theme extended to the experiential learning they received in their medical training. They acknowledged that their medical training challenged their compassion when they spent most of their time behind computers and studying for written exams. Rather, it was the experiential learning opportunities where they felt compassionate intentions arise. Finally, students were more likely than educators to express the importance of compassionate role models and teachers to cultivate compassion in their training, often providing specific exemplars of compassion.

3.3. Negative influences on compassion

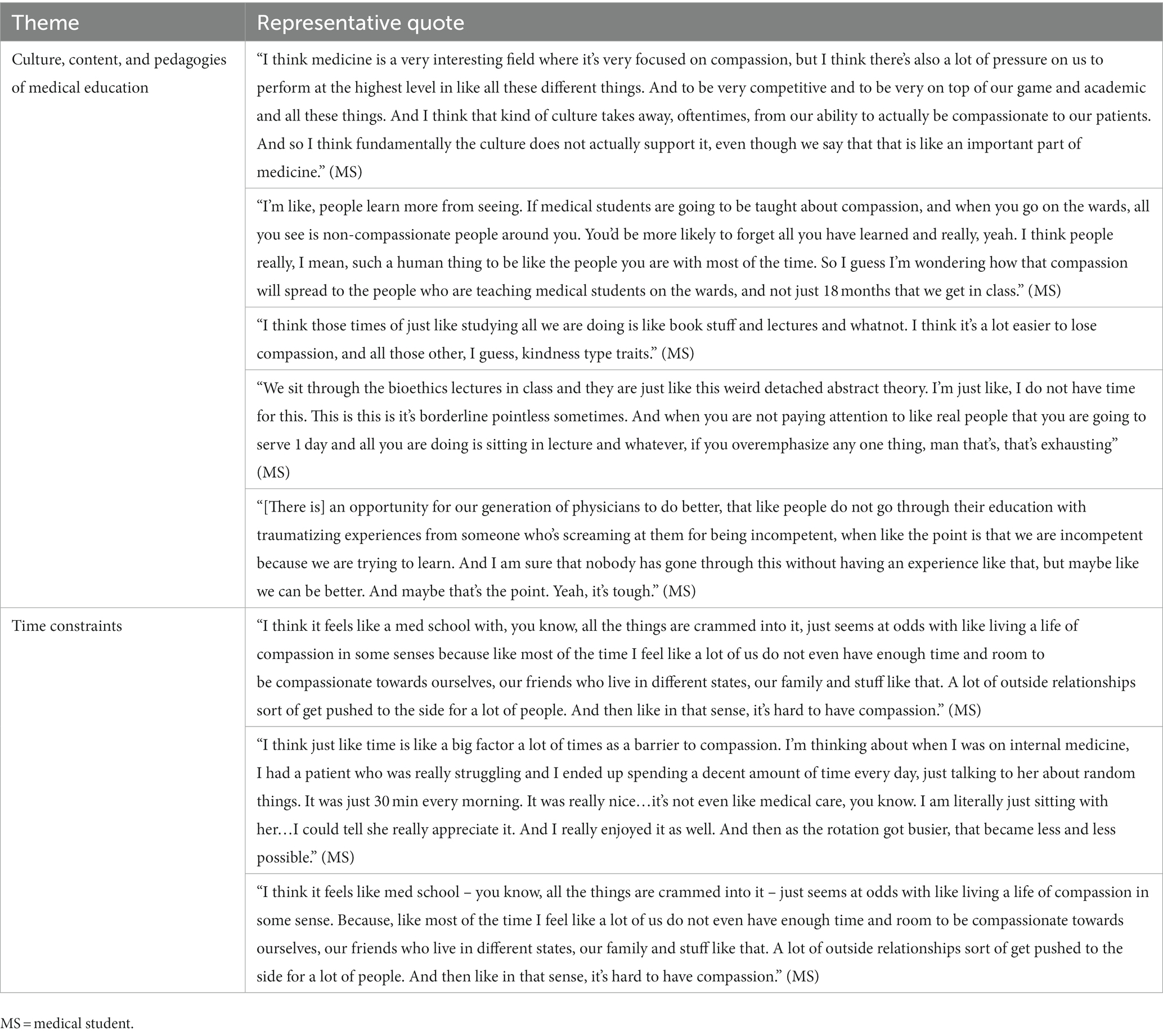

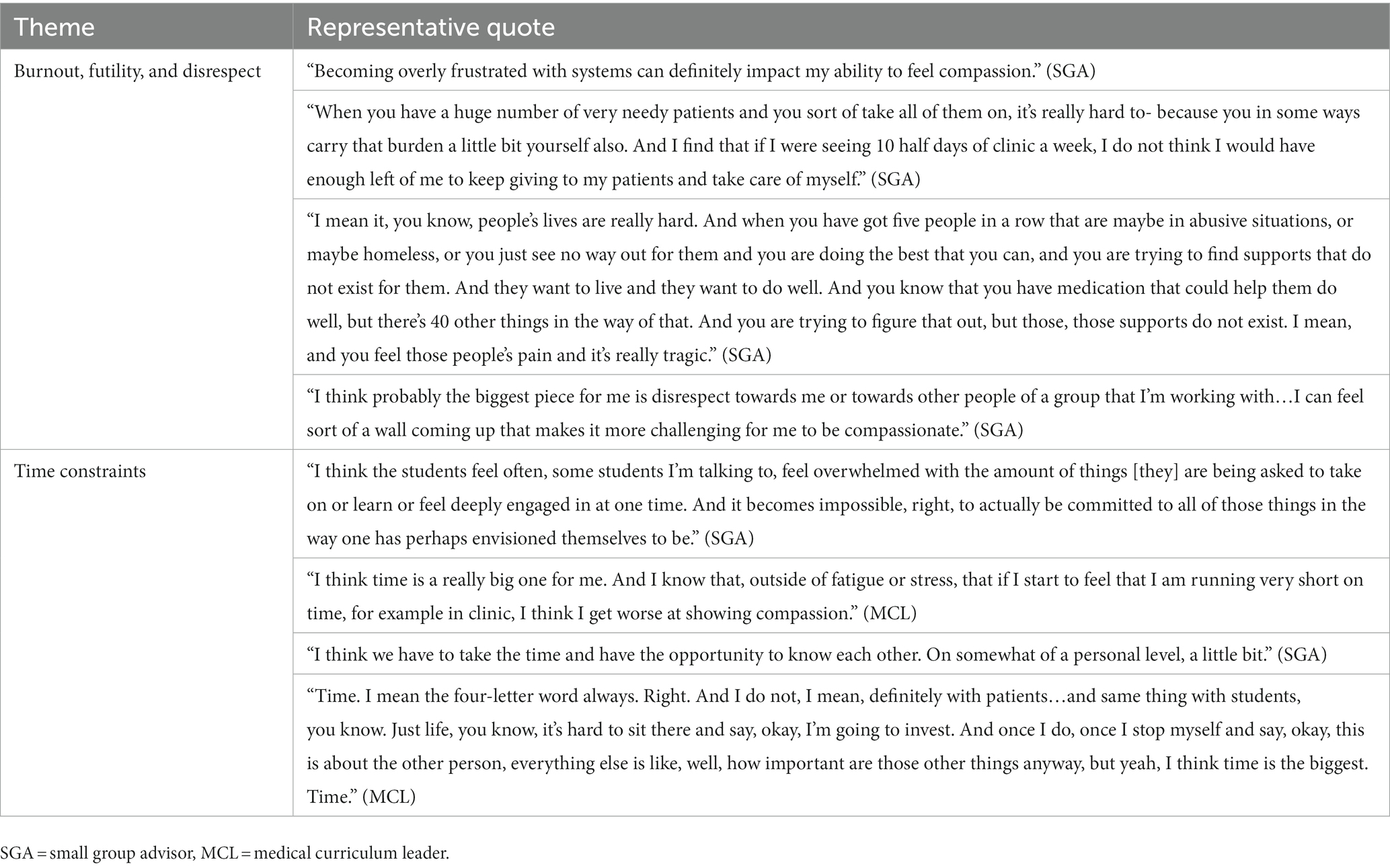

Participants also identified factors that inhibit the enaction of compassion in their day-to-day professional environment (themes and representative quotes found in Tables 4, 5). Emergent themes regarding the hindrances to compassion were slightly more varied between stakeholder groups. Differences were highlighted in their discussion regarding the culture of medical education. Students primarily described how the culture, content, and pedagogies of medical education were more likely to drain their compassion than bolster it. They discussed an overemphasis on book learning and multiple-choice exams, as well as experiencing a toxic culture on the wards. SGAs, on the other hand, were more likely to describe instances of burnout, futility, and disrespect as barriers to their compassionate intentions. They expressed a sense of hopelessness and exhaustion when their efforts to support patient care and student development confronted the limitations and failures of the health system and undergraduate medical licensing requirements. SGAs also expressed that disrespectful behavior created a barrier to their compassionate motivations. Whether it came from patients, colleagues, or students, and regardless of whether it was directed at them, their colleagues, or public health efforts in general, incivility was consistently noted as a barrier. Finally, all groups acknowledged time constraints as a major barrier to their experience of compassion. This included having time to complete professional responsibilities, time to take care of themselves, time to spend with colleagues and loved ones, as well as enough time to teach and learn the requisite content prior to graduation.

4. Discussion

Compassion is central to quality health care and antithetical to harmful states of burnout that so many healthcare professionals experience. Although medical education offers a formative time for sustainable compassion training, rather than preparing medical students for the rigors of practicing medicine, many students do not receive the training and support necessary to maintain their compassionate motivations in the face of personal and health systems limitations, often with devastating consequences (Hojat et al., 2009). Beyond measurable declines in compassion, within a short time of starting training, students experience increases in burnout, substance use, depression, and death by suicide (Ludwig et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2016; The National Academy of Medicine, 2019; Dyrbye et al., 2021). Moreover, studies examining the root causes of both the increase in mental distress and the decline in compassion point to the larger culture of medicine and have done so for decades (Pence, 1983; Neumann et al., 2011; The National Academy of Medicine, 2019). Rather than promoting the individual and collective benefits afforded through the expression of compassion, medical students are quickly inculcated with a mindset of “perfectionism, lack of vulnerability, and low self-compassion” (Shanafelt et al., 2019).

With the ultimate goal of facilitating the development of a comprehensive compassion curriculum for undergraduate medical education, this study examines how medical students, junior and senior small group advisors, and deans and directors of medical curricula conceive of compassion in the medical training environment. We also explored these key stakeholders’ perceptions of how their day-to-day routines and responsibilities support or hinder their compassion. When participants define compassion in their own terms, there is remarkable concordance across both educators and students with the definition commonly found in the scientific literature (Goetz et al., 2010; Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019; Mascaro et al., 2020). Across all focus groups, participants described compassion as an ineffable motivation that is more than empathy, demands action, and can be cultivated. Participants’ understanding that compassion is more than empathy is consistent with what has been identified as contributing to compassion’s apparent buffering effects to empathic distress and burnout (Singer and Klimecki, 2014; Trzeciak and Mazzarelli, 2019). Additionally, their identification of the ineffable felt sense of compassion is consistent with the physiological regulatory effects associated with compassion, including changes in stress and immune responses (Pace et al., 2010; Stellar et al., 2015). Just as anger can be felt in our bodies as tightness in our jaw, increased heart rate, or a sense of agitation, compassion has a somatic experience that researchers are uncovering is associated with widespread physiologic benefits (McCraty and Zayas, 2014; Stellar et al., 2015; Kirby, 2017; Volynets et al., 2020). Regarding the prospect of potential intervention, previous research has identified the belief that compassion is not a fixed trait – which was unanimous in our study population – as a prerequisite for effective compassion training (Sinclair et al., 2021b).

With respect to the factors of their day-to-day responsibilities that support their compassion, participants consistently identified the importance of life experiences. For students, they valued the experiences that put them in contact with others, but contrarily shared how they spend most of their time dedicated to over-simplifications in lieu of humanistic, context-dependent, whole-system science. Educators, on the other hand, talked more about the experiences they or their students may have had before coming to medical school “in the real world,” (i.e., not necessarily during formal medical training). For all groups, although self-care was seen as conducive and necessary for their compassion, participants also acknowledged how self-care was anathema to medical culture. The apparent importance of role models for student compassion highlights the harmful downstream effects of a system in which so many of their mentors and educators are burned out, under-resourced, and limited in their own compassionate reserve (Shanafelt et al., 2019). It follows from this that one of the best ways to cultivate sustainable compassion among medical students is to support their educators.

Confirming the above limitations to supporting student and educator compassion during undergraduate medical training, participants pointed overwhelmingly to the “status quo” as an active barrier to their day-to-day compassion. For students, this barrier emerged in relation to general lecture and test formats, specific clinical and non-clinical learning opportunities, and certain behaviors of potential mentors. Compounding this sentiment was a sense that there was not enough time in the day to accomplish all their academic demands, let alone attend to their personal well-being. For educators, a sobering and honest discussion of burnout and their sense of futility when fighting a poorly incentivized health system made clear that maintaining their compassion is often a practice of sheer individual will. Without institutional support, educators expressed how disrespect could challenge their ability to be compassionate towards others, regardless of circumstances. This sentiment also highlights a potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our results, as many educators shared how the increased demand on the healthcare infrastructure stressed their already limited bandwidth, leaving little room for a compassionate understanding of those who are impolite, disregard public health measures, or endanger others. Again, time constraints permeated every discussion with educators and contributed to a sense of hopelessness among SGAs and MCLs.

This study had several limitations. Beyond the small sample size of this study, the general limitations of convenience sampling create the potential for sampling bias. Focus groups should allow for a natural flow of conversation, and the resulting probing questions varied slightly from group to group. Additionally, while this study targeted UME, medical students and their formal educators are not siloed. The perspective of graduate medical education and continuing medical education, as well as the beliefs of nurses, pharmacists, social workers, support serves, administrators, industry, and patients, would help further elucidate the role of compassion in training future physicians. Additionally, future work can build upon the findings from this research by examining conceptions of compassion held at other institutions to examine whether our findings generalize to other undergraduate medical schools and to the broader medical training landscape. Continuing this work will be critical to developing a comprehensive approach to cultivating compassion within medical education and sustaining an effort to mend the professional culture of healthcare.

5. Conclusion

Medical students, those training them, and current patients are desperate for programs and interventions that prioritize and facilitate compassion in healthcare. Given the widespread benefits for those receiving, those expressing, and even those promoting compassion, it seems imperative that prompt and deliberate actions are taken to cultivate compassion in all aspects of medicine. To help with that endeavor, this research identifies the day-to-day facilitators and barriers to compassion in medical training. The sample is small, and it would be appropriate to continue studying the issue with a larger sample. Further research can develop more granular, actionable steps to inculcate the foundation of medical instruction with a culture conducive to creating the next generation of physician. Armed with sustainable compassion, these future leaders in medicine can persevere in greater numbers and help promulgate compassionate care for themselves, their colleagues, and their patients.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Emory University Institutional Review Board. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author contributions

CL conceived the study, helped develop the interview guide, IRB proposal, and initial code book, co-led focus groups, transcribed the recordings, and coded the transcripts. EB provided feedback on the interview guide, IRB proposal, and codebook. She co-led focus groups, coded the transcripts, and provided substantive feedback on the manuscript. JM secured the grant proposal that funded this work and provided guidance and oversight on the IRB proposal, interview guide, conduct of the focus groups, analysis, and interpretation. She also provided substantive feedback on several drafts of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number UL1TR002378.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ayala, G. X., and Elder, J. P. (2011). Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioral and social interventions to the target population. J. Public Health Dent. 71:S69. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00241.x

Bertakis, K. D., and Azari, R. (2011). Patient-Centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 24, 229–239. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100170

Cochrane, B. S., Ritchie, D., Lockhard, D., Picciano, G., King, J. A., and Nelson, B. (2019). A culture of compassion: how timeless principles of kindness and empathy become powerful tools for confronting today’s most pressing healthcare challenges. Healthc. Manage. Forum 32, 120–127. doi: 10.1177/0840470419836240

del Canale, S., Louis, D. Z., Maio, V., Wang, X., Rossi, G., Hojat, M., et al. (2012). The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad. Med. 87, 1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf

Dyrbye, L. N., Satele, D., and West, C. P. (2021). Association of Characteristics of the learning environment and US medical student burnout, empathy, and career regret. JAMA Netw. Open 4:e2119110. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19110

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., and Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol. Bull. 136, 351–374. doi: 10.1037/a0018807

Hojat, M., Louis, D. Z., Markham, F. W., Wender, R., Rabinowitz, C., and Gonnella, J. S. (2011). Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad. Med. 86, 359–364. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1

Hojat, M., Vergare, M., Maxwell, K., Brainard, G., Herrine, S., Isenberg, G., et al. (2009). The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of Erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad. Med. 84, 1182–1191. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55

Jackson, E. R., Shanafelt, T. D., Hasan, O., Satele, D., and v., Dyrbye LN., (2016). Burnout and alcohol abuse/dependence among U.S. medical students. Acad. Med. 91, 1251–1256. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001138

Kirby, J. N. (2017). Compassion interventions: the programmes, the evidence, and implications for research and practice. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 90, 432–455. doi: 10.1111/papt.12104

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Ricard, M., and Singer, T. (2014). Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 873–879. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst060

Lancet, T. (2019). Physician burnout: the need to rehumanise health systems. Lancet 394:1591. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32669-8

Liaison Committee on Medical Education (2022). Functions and Structure of a Medical School [Internet]. Standards, Publications, & Notification Forms. Available at: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Flcme.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2022%2F07%2F2023-24_Functions-and-Structure_2022-03-31.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK [Accessed November 21, 2022].

Lown, B. A. (2014). Seven guiding commitments: making the U.S. healthcare system more compassionate. J. Patient Exp. 1, 6–15. doi: 10.1177/237437431400100203

Ludwig, A. B., Burton, W., Weingarten, J., Milan, F., Myers, D. C., and Kligler, B. (2015). Depression and stress amongst undergraduate medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 15:141. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0425-z

Mascaro, J. S., Florian, M. P., Ash, M. J., Palmer, P. K., Frazier, T., Condon, P., et al. (2020). Ways of knowing compassion: how do we come to know, understand, and measure compassion when we see it? Front. Psychol. 11:2467. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.547241

Mascaro, J. S., Rilling, J. K., Tenzin Negi, L., and Raison, C. L. (2013). Compassion meditation enhances empathic accuracy and related neural activity. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 8, 48–55. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss095

McCraty, R., and Zayas, M. A. (2014). Cardiac coherence, self-regulation, autonomic stability, and psychosocial well-being. Front. Psychol. 5:1090. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01090

Michalec, BA (2009). Caring to learn, but learning to care?: The role of empathy in preclinical medical training. Vol. 70, Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

Moore, P. J., Adler, N. E., and Robertson, P. A. (2000). Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor-patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West. J. Med. 173, 244–250. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.173.4.244

Neff, K. D., and Dahm, K. A. (2015). “Self-compassion: what it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness,” in Handbook of Mindfulness and Self-Regulation, eds B. Ostafin, M. Robinson, and B. Meier (New York, NY: Springer). 121–137. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2263-5_10

Neumann, M., Edelhäuser, F., Tauschel, D., Fischer, M. R., Wirtz, M., Woopen, C., et al. (2011). Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad. Med. 86, 996–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

Neumann, M, Wirtz, M, Bollschweiler, E, Mercer, SW, Warm, M, Wolf, J, et al. (2007). Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: A structural equation modelling approach. Available at: www.elsevier.com/locate/pateducou [Accessed April 23, 2022].

Pace, T. W. W., Negi, L. T., Adame, D. D., Cole, S., Sivilli, T. I., Brown, T. D., et al. (2010). Issa CLR. Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and Behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, 87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.011

Patel, S., Pelletier-Bui, A., Smith, S., Roberts, M. B., Kilgannon, H., Trzeciak, S., et al. (2019). Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: a systematic review. PLoS One 14, 1–25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221412

Paterson, R. (2011). Can we mandate compassion. Hast. Cent. Rep. 41, 20–23. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2011.0036

Shanafelt, T. D., Schein,, Edgar, M. L. B., Trockel, M., Schein, P., and Kirch, D. (2019). Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clin. Proc. 94, 1556–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.026

Sinclair, S., Kondejewski, J., Jaggi, P., Dennett, L., Roze Des Ordons, A. L., and Hack, T. F. (2021a). What is the state of compassion education? A systematic review of compassion training in health care. Acad. Med. 96, 1057–1070. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004114

Sinclair, S., Kondejewski, J., Jaggi, P., Ordons, A. L. R., Des, K. A., Hayden, K. A., et al. (2021b). What works for whom in compassion training programs offered to practicing healthcare providers: a realist review. BMC Med. Educ. 2:455. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02863-w

Sinclair, S., McClement, S., Raffin-Bouchal, S., Hack, T. F., Hagen, N. A., McConnell, S., et al. (2016). Compassion in health care: an empirical model. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 51, 193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.009

Singer, T., and Klimecki, O. M. (2014). Empathy and compassion. Curr. Biol. 24, R875–R878. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.054

Sprang, G., Clark, J. J., and Whitt-Woosley, A. (2007). Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout: factors impacting a Professional’s quality of life. J. Loss Trauma 12, 259–280. doi: 10.1080/15325020701238093

Stellar, J. E., Cohen, A., Oveis, C., and Keltner, D. (2015). Affective and physiological responses to the suffering of others: compassion and vagal activity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 572–585. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000010

The National Academy of Medicine (2019).Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout.

Trzeciak, S, and Mazzarelli, A. Compassionomics: The revolutionary scientific evidence that caring makes a difference. Pensacola, FL: Studer group; (2019).

Volynets, S., Glerean, E., Hietanen, J. K., Hari, R., and Nummenmaa, L. (2020). Bodily maps of emotions are culturally universal. Emotion 20, 1127–1136. doi: 10.1037/emo0000624

Wang, H., Kline, J. A., Jackson, B. E., Laureano-Phillips, J., Robinson, R. D., Cowden, C. D., et al. (2018). Association between emergency physician self-reported empathy and patient satisfaction. PLoS One 13:e0204113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204113

Keywords: medical education, well-being, compassion, burnout, healthcare, training

Citation: Lane CB, Brauer E and Mascaro JS (2023) Discovering compassion in medical training: a qualitative study with curriculum leaders, educators, and learners. Front. Psychol. 14:1184032. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1184032

Edited by:

Sarka Hoskova-Mayerova, University of Defence, CzechiaReviewed by:

Babatunde Oluwaseun Onasanya, University of Ibadan, NigeriaIrena Tušer, AMBIS University, Czechia

Copyright © 2023 Lane, Brauer and Mascaro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Charles B. Lane, Y2hhcmxlcy5iZXJ0aW4ubGFuZUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Charles B. Lane

Charles B. Lane Erin Brauer1

Erin Brauer1

Jennifer S. Mascaro

Jennifer S. Mascaro