95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 07 August 2023

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1181976

Megan Cherewick1*

Megan Cherewick1* Christina Daniel2

Christina Daniel2 Catherine Canavan Shrestha3

Catherine Canavan Shrestha3 Priscilla Giri3

Priscilla Giri3 Choden Dukpa3

Choden Dukpa3 Christina M. Cruz4

Christina M. Cruz4 Roshan P. Rai3

Roshan P. Rai3 Michael Matergia5,6

Michael Matergia5,6Background: Most autistic individuals reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) and have limited access to medical providers and specialists. Support for delivery of psychosocial interventions by non-specialists is growing to address this mental health care gap. This scoping review involved a systematic analysis of studies of non-specialist delivered psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents diagnosed with autism and living in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods: The primary objective of this review was to identify psychosocial interventions for autistic children and adolescents in LMIC delivered by non-specialists (parent, teacher, peer, community, multi-level) and to summarize resulting effects on targeted outcomes. The search strategy was completed in four databases with predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The systematic search generated 3,601 articles. A total of 18 studies met inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data extraction was completed, and results summarized by; (1) participant sample; (2) intervention procedures; (3) implementation by non-specialists; (4) effect on evaluated outcomes; and (5) assessment of risk of bias. Studies examined a range of child and adolescent outcomes including assessment of communication skills, social skills, motor skills, functional and adaptive behaviors, emotional regulation, attention and engagement, sensory challenges, depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Several studies also evaluated intervention effects on family relationships, parent/caregiver stress and parent/caregiver mental health.

Results: Collectively, the 18 studies included a total of 952 ASC participants ranging in age from 2 to 16 years. Of the included studies, 8 studies were parent/caregiver-mediated, 1 study was peer-mediated, 2 studies were teacher-mediated, and 7 studies included multi-level non-specialist mediated components. Effects on evaluated outcomes are reported.

Conclusion: Non-specialist delivered interventions for autistic children and adolescents are effective for an array of outcomes and are particularly well suited for low- and middle-income countries. Implications for future research are discussed.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a group of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by differences in communication, socialization and repetitive or restricted patterns of behaviors, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These characteristics present differently in each autistic child and include a range of strengths and challenges. Classification of autism as a disorder in the DSM-5 nomenclature has received increasing attention. The term disorder motivates alignment with deficit focused frameworks and subsequent treatment approaches. More recently, autistic individuals and advocates have supported redefinition of Autism Spectrum Disorder to Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) to highlight heterogeneity in presentation that includes both challenges and strengths associated with autism. In this article, we will use the term “autism” or ASC to refer to autistic children and adolescents.

Autism Spectrum Condition has a global prevalence rate estimated to be between 0.7 and 1.5%, making ASC one of the most common developmental disabilities (Baird et al., 2006; Lord and Spence, 2006; Fombonne, 2009; Lyall et al., 2017). Comorbidity of ASC with other mental health challenges is common, including anxiety, depression, externalizing behaviors, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, feeding disorders, sleep disorders and sensory processing disorder which (Kogan et al., 2008; LoVullo and Matson, 2009; Reaven, 2009; Hodgetts et al., 2015; Vohra et al., 2017). A common challenge are sensory processing differences, estimated to be present in 80% of children with ASC (Ben-Sasson et al., 2009). Another study found 50% of parents described their autistic child as having more than four comorbid problems (Mannion et al., 2013).

Caregivers of autistic children often experience financial impacts related to caring for their child and may be unable to earn a livelihood due to the responsibilities of caring for their child without adequate support (Rogge and Janssen, 2019). While it is difficult to compare costs associated with ASC globally due to wide variation in cost categories by country, the total costs of care are profound regardless of context. Costs include caregiver productivity loss, medical care, special education, specialized therapies, and accommodation in residential facilities (Amendah et al., 2011; Deanna and Dana, 2011; Buescher et al., 2014). In recent reviews it was estimated that overall lifetime costs for autistic individuals are estimated to be $2.4 million – 3.2 million in US dollars with costs of services accounting for 79% of the total cost burden (Ganz, 2007; Järbrink, 2007; Buescher et al., 2014; Rogge and Janssen, 2019).

In the past few decades, new approaches to supporting autistic children – predominantly psychosocial interventions, have been developed. Psychosocial interventions are interpersonal or informational activities, techniques, or strategies that aim to improve the health, functioning and wellbeing of children by targeting biological, behavioral, cognitive, emotional, social, or environmental factors that affect autism outcomes (Committee on Developing Evidence-Based Standards for Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Disorders et al., 2015). While traditional approaches to “treating” autism have focused on deficits and inabilities, a paradigm shift toward neurodiversity frameworks shifts attention toward recognition of differences in abilities and strengths. Common strengths of autistic children include excellent memory skills, attention to detail, motivation to recognize patterns, visual learning, analytical proficiency, and creative thinking (Craig and Baron-Cohen, 1999; Baron-Cohen, 2006; Chamak et al., 2008; Dawson and Mottron, 2009; Mottron et al., 2013, 2014; Russell et al., 2019). A neurodiversity framework combines recognition of differences in functional and behavioral presentation, and strengths, to center intervention focus on inclusion, needed accommodations and support tailored to each autistic child. Current research has reached consensus that autistic children require specialized interventions tailored to support needs to address challenges in communication (Smith et al., 2004), social interaction (Mcconnell, 2002), sensory regulation (Dawson and Watling, 2000; Baranek, 2002), and behaviors (Matson and Rivet, 2008).

Of the estimated 52 million individuals with ASC in the world, most autism research has been completed in high-income countries (HIC) even though most autistic children live in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (Rahman et al., 2016; Pervin et al., 2022). While there is growing evidence for the positive impact of psychosocial interventions, the vast majority have been developed and tested in HIC in the global north although 95% of autistic individuals live in LMIC without access to diagnostic, treatment or support services (Pervin et al., 2022). For example, South Asia is a region with the largest number of children in the world with recent epidemiological estimates from India indicating approximately two million families had a child with ASC between the ages of 2–9 (Deshmukh et al., 2013). A recent meta-review analyzing systematic reviews on the effectiveness of interventions in autistic children and adolescents compared intervention approaches reported from HIC and LMIC (Pervin et al., 2022). Results from the meta-review included 35 systematic reviews; 6 included comprehensive treatment programs addressing multiple developmental domains (e.g., communication skills, social skills, daily living skills, and sensory regulation), two of which were from LMIC; 14 included focused interventions targeting a specific behavioral or developmental problem such as joint attention, five of which were from LMIC; and 11 reviews included complementary and alternative medicine interventions (e.g., acupuncture, massage, herbal medicine), seven of which were from LMIC (Handleman and Harris, 2001; Vismara and Rogers, 2008; Pervin et al., 2022). Results also reported that 15 reviews included delivery by non-specialists with 5 from LMIC; 4 reviews included medical interventions with two from LMIC; and 15 reviews examined technology-assisted interventions, two from LMIC (Vismara and Rogers, 2008).

To address the care gap for autistic children in LMIC, the global community has begun to consider different implementation strategies to deliver psychosocial support that is feasible, acceptable, and sustainable in resource-poor settings. The body of research produced in high-income countries on autism is an important contribution to the evidence in design of effective autism interventions, however, these findings need to be translated appropriately with communities to be effective in contexts where resources and cultural belief systems vary dramatically. An opportunity for innovation in LMIC to develop, test, and refine new intervention approaches exists that can advance progress toward supporting development of autistic children and adolescents that is effective, efficient, scalable, and sustainable in LMIC.

Seizing this opportunity will require addressing cultural knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors specific to a particular setting, as well as more universal challenges such as access to formal diagnostic evaluation, time, and costs associated with programs for autistic individuals. A crucial difference between HIC and LMIC contexts is the availability of specialist providers. Interventions in HICs most often include parent coaching and one-on-one therapy with speech language pathologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, developmental interventionists, and developmental and psychiatric physicians (Rojas-Torres et al., 2020; Gibson et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022). In low-resource contexts, lack of access to mental health specialists is limited and specialists are typically concentrated in urban areas and these specialists are more likely to expect higher salaries provided by private sectors which can further exacerbate the gap between poorer and more affluent communities to afford and access needed services.

An additional barrier faced in LMIC is the limited availability of specialists that can provide a clinical diagnosis of ASC. Many of the “gold standard” diagnostic tools are difficult to access by researchers in LMIC and/or may not be available in local languages, culturally adapted or validated in LMIC. The costs associated with using these tools are estimated to exceed per capita annual healthcare expenditures for most of the global ASC population by more than four-fold (Durkin et al., 2015). Heterogeneity in the presentation of autism poses challenges to developing tools with the sensitivity and specificity to capture the full range of presentation of autism symptoms across the spectrum (Durkin et al., 2015). In addition, cultural differences in perceptions of typical or atypical behavior are interwoven with culturally defined norms and standards (Mandell and Novak, 2005; Norbury and Sparks, 2013; Donohue et al., 2019; de Leeuw et al., 2020). For example, measures evaluating eye contact and imaginary play are commonly used to screen and diagnosis autism in the global north, but in other contexts, these measures may not be well-aligned to cultural value systems (Zhang et al., 2006; Bernier et al., 2010; Bornstein, 2013; Smith et al., 2017). While there has a been a proliferation in screening and diagnostic tools, comparatively less research studies have been published testing ASC interventions in LMIC (Rojas-Torres et al., 2020).

Within the field of global mental health, task-shifting approaches have been utilized to address human resource challenges associated with the limited availability of specialists (Divan et al., 2015; Matergia et al., 2019). In task shifting, professionals train and coach non-accredited human resources (such as lay counselors and community health workers) to deliver care. Examples of this approach for child and adolescent mental health may be particularly instructive given the co-morbidity of autism and other mental health challenges. In LMIC settings where psychologists and therapists are in short supply, there is emerging evidence for the delivery of mental health care by lay counselors such as teachers. For autistic children and adolescents, non-specialist mediators of psychosocial interventions have included parents, teachers, peers and/or community members.

A review of psychosocial interventions for autistic children in LMIC, delivered by non-specialists is important to build a nuanced evidence-base that examines which outcomes were attained by non-specialists. The primary objective of this review was to evaluate current evidence on use of non-specialist delivered interventions for autistic children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries. This review sought to describe the characteristics of studies, type of non-specialists delivering interventions; effect on evaluated targeted outcomes, and to appraise the certainty of the evidence by completing a risk of bias (RoB) quality assessment. A secondary objective was to identify potential synergies for impact by evaluating effects of multi-level implementation designs to identify gaps in the existing research and to inform future research efforts. This paper adds to the literature in providing a comprehensive overview of psychosocial interventions and the effect on outcomes delivered by non-specialists in LMIC.

The initial search strategy was designed with assistance from a health sciences librarian at CU Anschutz Strauss Medical Libraries to search the following: (1) Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms for autism spectrum disorder, (2) MeSH terms for child OR adolescent, (3) key words for psychosocial intervention studies, and (4) LMIC status determined by World Bank-defined low-and middle-income countries. The search was completed on December 5th, 2022. The following data bases were queried: MEDLINE ALL (1946 to date before search date); Embase (11974 to search date); Web of Science, American Psychological Association PsychInfo (1806 to present), and Global Index Medicus (World Health Organization). We identified additional sources through bibliography scans of included references. Search terms were first developed for Ovid Medline and were subsequently translated for each database (Table 1).

All raters screened title and abstracts and applied the inclusion/exclusion criteria displayed in Table 2. Inclusion criteria included: (1) target population was children or adolescents (defined as ages 0–19), (2) target population was children/adolescents who had received an autism diagnosis, (3) included original data resulting from a psychosocial intervention that was delivered by non-specialists, (4) conducted in an LMIC, and (5) were published in English up until December 5th, 2022, (6) study sample > 10. Psychosocial interventions were defined as “interpersonal or informational activities, techniques, or strategies that target biological, behavioral, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, social, or environmental factors with the aim of improving health functioning and well-being” (Committee on Developing Evidence-Based Standards for Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Disorders et al., 2015). Non-specialists were defined to include community health workers, parents/caregivers, teachers, community leaders, and peers. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Three authors examined articles for eligibility (CD, CCS, and MC).

Title and abstract screening agreement using the inclusion and exclusion criteria was obtained in 95.12% of studies. During full-text review, agreement between reviewers was obtained in 74.19% of studies reviewed. Discrepancies were resolved through discussions among CC, CCS and MC.

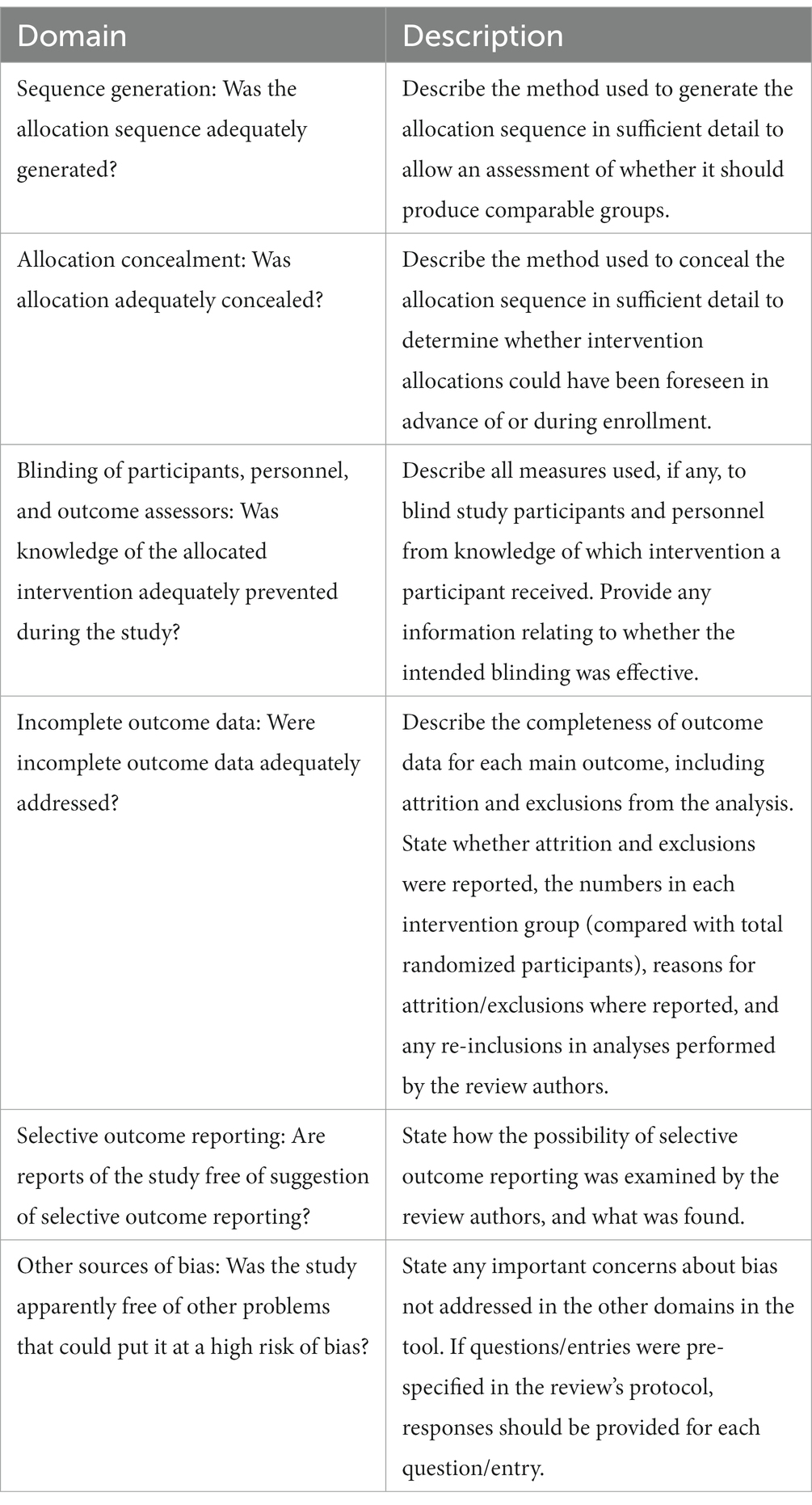

Quality assessment was completed using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trails (RoB 2) and were completed independently by two review authors (SG and CD) with discrepancies resolved by MC (Sterne et al., 2019). Table 3 reports the risk of bias domains; (1) Sequence generation; (2) Allocation concealment; (3) Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; (4) Incomplete outcome data; (5) selective outcome reporting; and (6) Other sources of bias (Sterne et al., 2019). Judgements were rated as ‘high’, ‘moderate’ and ‘low’ risk of bias.

TABLE 3. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool (Sterne et al., 2019).

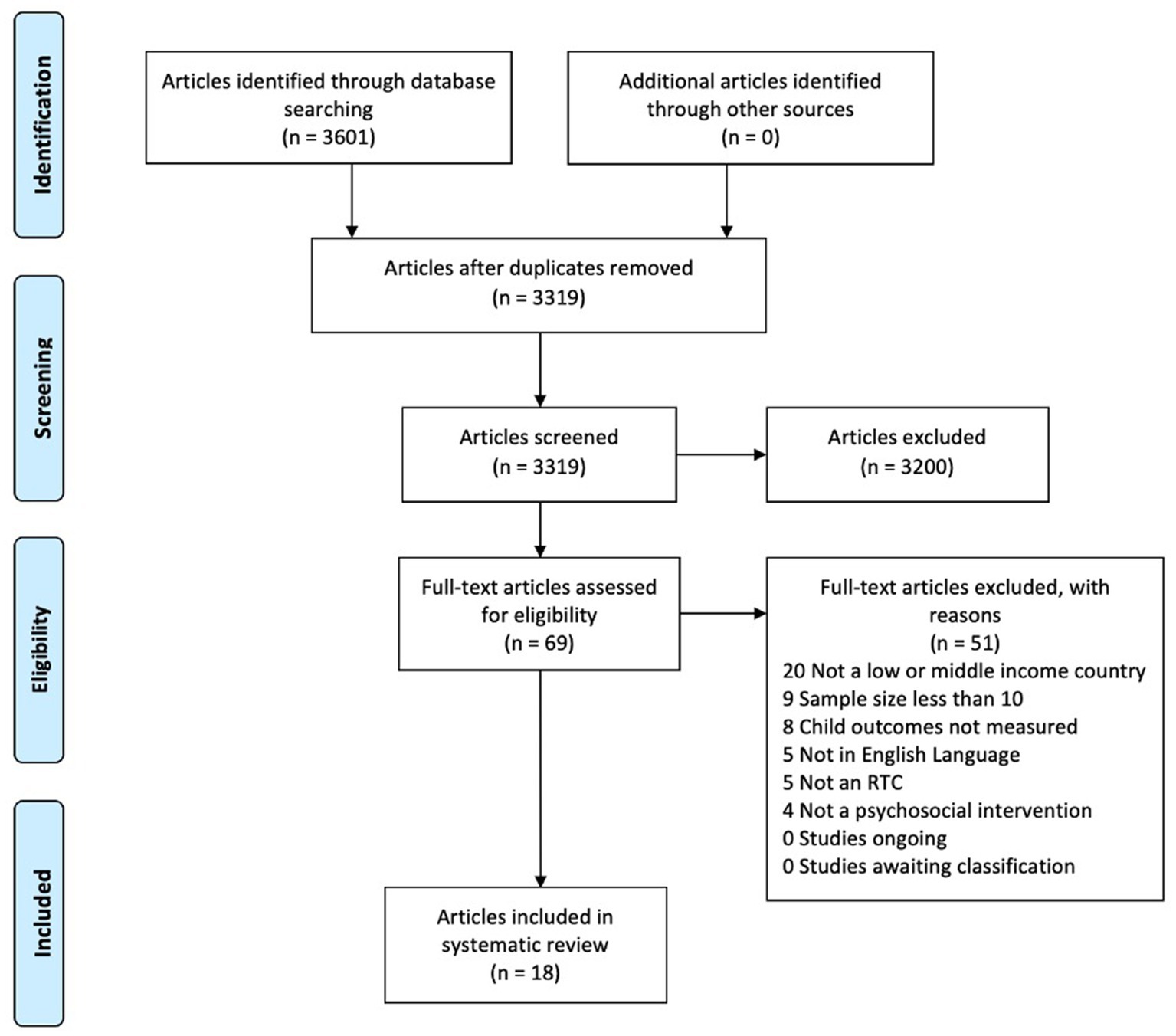

After completing the search, 3,877 total citations were retrieved. Duplicates were removed and organized using the citation management software Endnote version 20. After duplicates were removed 3,601 total unique citations were uploaded to Covidence, a systematic review citation and screening software. Covidence detected 282 additional duplicates leaving 3,319 citations for initial title/abstract screening. After screening titles/abstracts, 3,200 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full-text review was completed on the remaining articles (N = 69) and studies were excluded if they were found not to meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 18 articles were included in the final review and reasons for excluded studies (N = 51) are presented in the PRISMA systematic review flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009).

Quality assessment was completed using the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool for randomized trails (RoB 2) and were completed independently by two review authors (SG and CD) (Sterne et al., 2019). Final judgements of risk of bias were then reached by consensus (SG, CD and MC). In total, 8 studies were assessed to have low risk of bias; 7 were judged to have ‘moderate’ risk of bias; and 3 were assessed as “high” risk of bias.

A scoping review database was created in Covidence to allow for extraction of data from each of 18 empirical research articles. All studies included participants who had received an autism diagnosis. The following data was collected from each study: (1) bibliographic information including author, year, country, study design; (2) sample size and description; (3) intervention descriptions and outcomes targeted; (4) implementation methods, challenges, and successes; and (5) main findings on effect on targeted outcomes. Detailed results of included studies, effects on measured outcomes, and risk of bias judgements are presented in Table 4 and organized by type of non-specialist delivered components. In total, 952 autistic children and adolescents were included in the 18 studies. Eight included studies were parent/caregiver mediated approaches that were sometimes supplemented by coaching of parents by therapists. In some studies, the intervention was designed to integrate educational and developmental techniques such as those from Developmental, Individual-Difference, Relationship-Based DIR techniques (Pajareya and Nopmaneejumruslers, 2011; Casenhiser et al., 2015), Early Start Denver Model (Dawson et al., 2010), Early intensive behavioral intervention (Smith, 2010), parent coaching (Ingersoll and Dvortcsak, 2019), Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions (Schreibman et al., 2015), and Home-based sensory intervention (Chara and Chara, 2004; Pfeiffer et al., 2011).

One study was a peer-mediated intervention to improve social interaction. Two studies were teacher-mediated with one using virtual reality training and physical education and the other focused on sensory regulation based on “the Sensory Diet” (Lease et al., 2016). A total of seven included studies included a parent component and a second level; one study was a parent and sibling mediated intervention, four were parent and teacher mediated interventions, and two were parent and community mediated interventions. The parent-sibling-mediated intervention adapted Rational emotive behavior therapy (Ellis and Dryden, 2007) Parent-teacher-mediated interventions including adaptations of Multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention (White et al., 2013), emotional enhancement intervention (Solomon et al., 2004), massage therapy, and the Early Start Denver Model (Dawson et al., 2010). The parent-community-mediated interventions were both modeled after parent-mediated interventions in India (Rahman et al., 2016). The duration of intervention in included studies ranged from 3 weeks to 6 months with considerable variation in the intensity of sessions (daily to weekly). The control conditions reported ranged from no treatment, or ‘treatment as usual’ to alternative treatments.

Investment in capacity building around training professionals to meet the needs of children with autism may not be the most efficient or effective approach in LMIC. First, the costs associated with training professionals can be resource intensive and time-consuming. Lessons learned from LMIC indicate that it can be difficult to incentivize trained professionals to serve populations in remote, rural, locations (Strasser, 2003; Pruitt and Epping-Jordan, 2005, Anyangwe and Mtonga, 2007). Second, trained professionals are also more likely to expect higher salaries provided by private sectors which can further exacerbate the gap between poorer and more affluent communities to afford and access needed services (Kolehmainen-Aitken, 2004; Hagopian et al., 2009). Third, the types of supportive therapy that may be effective in ASC children and adolescents is widely variable and comparative studies between specialists and non-specialists delivering interventions have not been completed. Autism interventions must be flexibly adapted to the unique sets of needs and strengths of each autistic child, and non-specialists close to autistic individuals may be best positioned to notice these needs and strengths (Fleming et al., 2015). Non-specialists such as parents, teachers, peers, siblings and community members can identify opportunities to scaffold learning approaches that reinforce or inclemently challenge a child appropriately (Burrell and Borrego, 2012; Guralnick, 2019). Fourth, a focus on delivery of therapeutic interventions by specialists can dissuade education systems from embracing inclusive learning environments that have been shown to be effective in supporting learning of a broad array of neurodiverse students (Mariga and McConkey, 2014). Fifth, leveraging naturalistic, real-life settings is important for supporting the development of ASC children by providing opportunities to practice and master skills in different settings. This may be particularly true for ASC where the disabilities experienced by differences in social emotional and communication areas are experienced in relationship with the context in which the individual lives (e.g., neighborhoods, schools, work environments) (Ebbels et al., 2019).

Most autism intervention approaches in low- and middle-income countries are parent/caregiver mediated interventions (N = 8; 44%). In total, Parent/Caregiver intervention approaches included children ages 2–12, with all but one study targeting children ages 2–6. The reason for targeting parents/caregivers during this age is based on evidence suggesting positive effects of early intervention (ages 1–7) on developmental trajectories (Anderson et al., 1987; Corsello, 2005; Itzchak and Zachor, 2011), however the quality of the evidence base is low with few successful replication studies (McConachie and Diggle, 2007). Results from meta-analyses of parent-mediated RCTs have found small but significant effects for parent–child interaction only, with insignificant effects for communication, language, adaptive behavior and adaptive behavior (Oono et al., 2013; Nevill et al., 2018). While reviews have reported small positive effects for children, there is evidence of greater improvements for parents, including reduced stress and increased sense of competence (Wyatt Kaminski et al., 2008; Beaudoin et al., 2014). Reduction in parenting stress is an important outcome because parents and caregivers of autistic children experience higher rates of mental health disorders than parents of neurotypical children (Bitsika and Sharpley, 2004; Davis and Carter, 2008; Estes et al., 2009; Phetrasuwan and Shandor Miles, 2009).

A challenge to meta-analysis of parent-mediated interventions is that programs vary dramatically in theoretical background supporting the approaches tested. More recently, critiques of early intervention have emerged that argue that early intervention approaches have often set goals that are not well matched to common autistic learning trajectories and/or target goals that unnecessary for healthy development such as reduction in repetitive behaviors and special interests (Mottron, 2017). While many autism interventions have focused on supporting parents/caregivers of children with ASC to reduce the mental health burden of parents/caregivers who experience stress, financial difficulties, and stigma, more recent research has aimed to capture positive parenting experiences of children with developmental disabilities (Hastings and Taunt, 2002).

Two studies reviewed were teacher mediated interventions delivered in school classrooms. One study completed in Turkey included autistic children 7–11 years old who received 12-weeks of the intervention that included somatosensory stimulation based on the “The Sensory Diet” (Fazlioglu and Baran, 2008). This study found significant improvements in auditory responsiveness, and social communication and a significant reduction in repetitive behavior and sensory problems. The second teacher-mediated intervention included autistic children ages 12–13 living in China and included six weeks of virtual environment training and physical exercise with a significant effect reported on visual attention outcomes (Ji and Yang, 2021). Both studies were assessed to have high risk of bias.

Teacher-mediated interventions for autistic children and adolescents are a promising new approach to addressing ASC support services, especially in LMIC settings where special education services are limited, and most school-attending autistic children are in general education classrooms. Many teachers have received training in child development and are skilled in individualizing instruction based on developmental level. By building off this experience, teachers may be trained in the skills needed to support autistic children and adolescents with different need. Furthermore, teachers have daily consistent access to autistic children and can observe changes in behavior, social, emotional, and cognitive patterns. Prior research has indicated that teachers trained in integrating mental health care for indicated cases in delivery of curriculum can benefit children with mental health challenges and simultaneously support the mental wellbeing of classmates (Cruz et al., 2021). While this intervention was not designed for autistic children, a motivation for teachers delivering care in an inclusive classroom environment to empower teachers with the skills needed to address a range of mental health symptoms. Training teachers to support autistic children could similarly help to address a broad range of needs and strengths of autistic children and could potentially help to reduce stigma associated with autism. Enhancing the capacity of teachers to help support learning in an inclusive environment can reduce costs associated with private schools and/or special needs schools and provides an additional benefit of allowing autistic children to learn through peer-modeling of neurotypical kids. Additionally, a recent review on economic costs related to ASC found that education related costs were a major cost component for parents and children (Rogge and Janssen, 2019). Enhancing the capacity of teachers to help support learning in an inclusive environment can reduce costs associated with private schools and/or special needs schools and provides an additional benefit of allowing autistic children to learn through peer-modeling of neurotypical kids (Anaby et al., 2019).

Peer mediated interventions include approaches where peers are trained to deliver or facilitate programs (Harrell et al., 1997; Laushey and Heflin, 2000). Only one study included in this review was peer mediated. This study was completed in China with autistic children ages 4–12, matched to neurotypical peers trained to support social skill development over 2 months (Zhang et al., 2022). Importantly, while results indicated a significant improvement in social skills, the authors noted that peer interventionists did not work well with ‘severely autistic children’(Zhang et al., 2022). In high-income countries, peer-mediated intervention approaches for ASC have shown similar positive effect on acquisition of social skills (DiSalvo and Oswald, 2002; Bass and Mulick, 2007). Including peers in school-based intervention approaches may be particularly beneficial in combination with teacher-mediated interventions because peers can provide reinforcing opportunities for social emotional learning and to practice social emotional skills in the classroom, during breaks, during mealtimes, during recess, and in before and after school programs (Chan et al., 2009).

Findings from developmental science on neurotypical children suggest that key transitional periods or inflection points during adolescence can improve the efficacy of interventions through precision in timing, sequencing, and design (Crone and Fuligni, 2020). The rapid changes in neural development and hormones that occur during puberty heighten the affective salience of experiences with peers, family, school, and the community. As adolescents develop, they are increasingly sensitive to social status and admiration or social rejection and loneliness (Steinberg, 2008; Blakemore and Mills, 2014; Lam et al., 2014; Shulman et al., 2016; Orben et al., 2020). As adolescents learn to navigate an increasingly complex social world, they actively shape their own identity, sense of purpose, and set goals for the future (Crone and Dahl, 2012; Pfeifer and Berkman, 2018). Integrating peer-mediated components during adolescence, particularly early adolescence (ages 10–14) should be explored for autistic children and including peers in intervention approaches can also reinforce inclusivity in learning environments and could potentially reduce stigma associated with autism.

Seven studies were categorized as ‘multi-level’ for including both a parent-mediated component with a sibling component (N = 1), teacher component (N = 3), or community member component (N = 3). In Nigeria, a parent and sibling intervention included autistic adolescents ages 15–16 that completed a 120 week Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy intervention that reported positive effects on communication skills and social skills (Nnamani et al., 2019). Four studies included parent and teacher-mediated components in Kenya, India, Thailand, and China. Age ranges of included participants ranged from 2 to 12 years of age and duration of the intervention varied from 8-weeks to 6-months. Positive significant effects were found for communication and social skills, adaptive behavior, and improved sleep; significant reduction in global autism symptoms, anxiety and repetitive behaviors were reported. Two included studies involved parent and community member components, both completed in India over 6-months. The community members involved in the interventions were community members who received training. These two studies reported positive effects on communication skills and parental mental health, but non-significant findings were reported for global autism symptoms, verbal language, and adaptive behaviors. For many mental health disorders, psychosocial interventions that engage multiple levels within an individual’s social ecology have proven to be successful (Kohrt et al., 2018).

A comprehensive review of interventions for autistic children in LMIC is useful because certain types of needs and strengths of autistic children may be most effectively addressed if developmentally timed, sequenced and matched to the support system most effective in affecting change in particular areas of difference (Green, 2019). Leveraging naturalistic, real-life settings is important for supporting the development of autistic children. Scaffolding appropriate opportunities for mastery and challenge in different contexts and with different influential people within the social-ecology of autistic children should be explored (Carey et al., 2019). In all contexts, but particularly in LMIC comprehensive approaches addressing multiple developmental domains are most promising because they can better address the diverse needs and strengths of autistic individuals in comparison to focused treatment approaches targeting a specific need.

In addition to matching non-specialist mediated interventions to developmental periods, future research should consider the strength and quality of existing evidence and the perspectives of autistic adults on which outcomes should be targeted, when and by whom. Findings from developmental neuroscience are useful to consider which outcomes to target during a developmental period. For example, experience-expectant learning theories explain that neurological development influences whether or not the brain can process and learn from environmental stimuli (Greenough et al., 2002). Further, research with autistic adults has underscored the situational importance of whether particular autistic traits are advantageous or disadvantageous in different contexts because particular traits may be more or less favorably perceived dependent on cultural and situational factors (Mandell and Novak, 2005; Norbury and Sparks, 2013; Donohue et al., 2019; de Leeuw et al., 2020). For example, eye contact may be valued in some cultural contexts but may be unexpected or even perceived as disrespectful in others (Zhang et al., 2006; Bernier et al., 2010; Bornstein, 2013; Smith et al., 2017).

Meta-analyses show that specialist interventions have been completed mostly in HIC to address behavioral problems, however, it is plausible that comprehensive treatment approaches beginning during early childhood and continuing through early adulthood delivered by non-specialists may prevent the need for clinical intervention. Comparative evaluation studies examining differences in implementation strategies and effectiveness are needed to identify mechanistic pathways through which interventions achieve effects. Implementation science is urgently needed to identify mechanisms of change that result in positive effects. Mechanisms of change include affective, behavioral, cognitive, and physiological mediating variables (Cherewick and Matergia, 2023). Identification of implementation barriers and facilitators would provide evidence needed to understand the implementation factors required to achieve effects in diverse contexts. Implementation science can also support identification of essential elements to achieve effects, thereby eliminating redundant or ineffective elements and reshaping intervention design strategies to focus on amplifying the most potent elements of interventions.

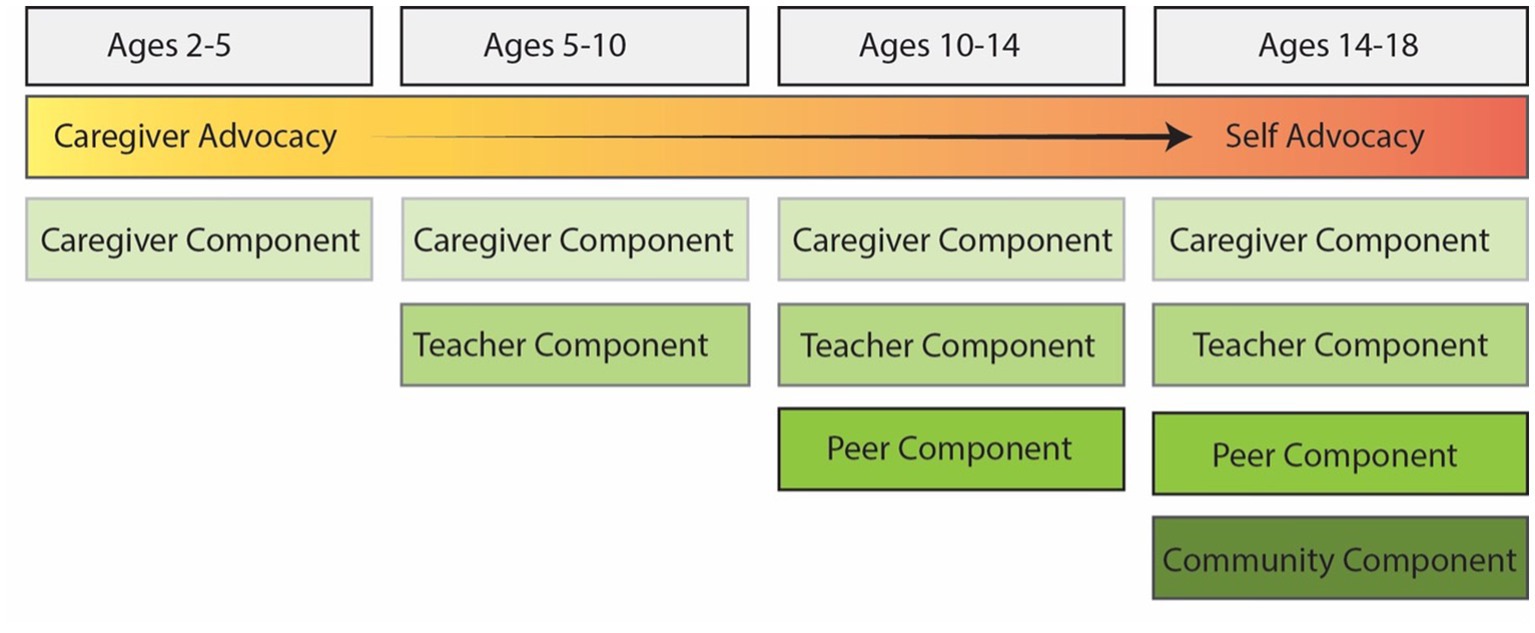

Future research should consider testing interventions during developmental periods where non-specialist interventionists are likely to be most influential in supporting needs and leveraging strengths of autistic children. A general schema for sequential and multi-level intervention components is provided in Figure 2. Caregiver mediated interventions may be best matched to support communication and regulation skills during early development. Teacher mediated interventions may be best matched to support executive function, and adaptive behavior. Peer mediated interventions may be best matched to supporting social emotional learning. Community mediated interventions may be best matched to for mastery learning in specific vocational skills. Across development, integrating positive, neurodiversity affirming advocacy messages may be especially beneficial for autistic children and adolescents. Designing effective advocacy focused components that can be integrated into interventions should consider participatory methods and co-design with autistic adults.

Figure 2. Developmentally sequenced social ecological intervention model for autistic children and adolescents.

The addition of an overarching advocacy component across childhood and adolescence in Figure 2 is included to represent the reinforcing potential of advocacy efforts that begin with caregivers and transition to self-advocacy as autistic children develop. Autism advocacy can reduce stigma, and allows autistic children and their families to articulate needed accommodations and strengths (Mitter et al., 2019). Previous research has explored participatory methods and co-design of autism interventions with autistic adults (Chamak et al., 2008; Davidson, 2010; Kuper et al., 2021). Autistic adults can bring lived experience to improve all aspects of the research process including design of studies, intervention, implementation, and evaluation methods. Future research should consider inclusion of autistic adolescents in design of intervention programming. Inclusion of autistic individuals in design of interventions may also help support flexibility in implementation by identifying how interventions can be best tailored to different developmental levels, needs, and strengths.

Due to time and resource restraints, this study was limited to randomized controlled trial designs. We recognize that other study designs are important to designing effective interventions. We excluded studies that used artificial intelligence and/or robot implementation methods because these methods did not fit our pre-determined definition of psychosocial interventions. However, technology-mediated interventions and those that use artificial intelligence, while nascent, may hold promise in the future.

Non-specialist mediated interventions for autistic children and adolescents are well suited for resource poor-environments. Studies included in this review demonstrated non-specialist delivered interventions in LMIC had positive effects in communication/language, social skills, motor skills, adaptive behaviors, and improved mental wellbeing. Moreover, synergies between non-specialist mediated intervention approaches across development should be matched and sequenced to developmental periods. An approach that engages multiple non-specialists in a child’s social ecological environment can be particularly beneficial to allow autistic children and adolescents to practice and master learning in different settings. Multi-level intervention approaches can also effect change in the individuals’ delivering interventions, leading to enhanced autism advocacy efforts to reduce stigma and celebrate the unique strengths of autistic individuals.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MC, MM, and CC conceived of the objective of the systematic review. MC developed the search strategy and completed searches in databases. CDa and CS completed title and abstract screening, and full text-reviews. CDa and MC completed quality assessments of included articles. MC resolved any conflicts. MC, MM, RR, CDa, PG, CC, CDu, and CS analyzed and synthesized the results. All authors contributed substantially to writing the manuscript, read and approved of the manuscript prior to submission.

The authors are grateful for the assistance of Ben Harnke, MLIS at Strauss Health Sciences Library, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus for his assistance in developing our search strategy. The authors would also like to acknowledge Sarah Gelinas, who assisted with the quality assessment of included articles.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Embase.com

Akhani, A., Dehghani, M., Gharraee, B., and Hakim Shooshtari, M. (2021). Parent training intervention for autism symptoms, functional emotional development, and parental stress in children with autism disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Asian J. Psychiatr. 62:102735. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102735

Amendah, D., Grosse, S. D., Peacock, G., and Mandell, D. S. (2011). “The economic costs of autism: A review,” in Autism spectrum disorders. eds. D. Amaral, D. Geschwind, and G. Dawson (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1346–1360.

Anaby, D. R., Campbell, W. N., Missiuna, C., Shaw, S. R., Bennett, S., Khan, S., et al. (2019). Recommended practices to organize and deliver school-based services for children with disabilities: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 45, 15–27. doi: 10.1111/cch.12621

Anderson, S. R., Avery, D. L., Dipietro, E. K., Edwards, G. L., and Christian, W. P. (1987). Intensive home-based early intervention with autistic children. Educ. Treat. Child. 10, 352–366.

Anyangwe, S. C., and Mtonga, C. (2007). Inequities in the global health workforce: the greatest impediment to health in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 4, 93–100. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2007040002

Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D., et al. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the special needs and autism project (SNAP). Lancet 368, 210–215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7

Baranek, G. T. (2002). Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 32, 397–422. doi: 10.1023/A:1020541906063

Baron-Cohen, S. (2006). The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 30, 865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010

Bass, J. D., and Mulick, J. A. (2007). Social play skill enhancement of children with autism using peers and siblings as therapists. Psychol. Sch. 44, 727–735. doi: 10.1002/pits.20261

Beaudoin, A. J., Sébire, G., and Couture, M. (2014). Parent Training Interventions for Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism res. treat. 2014:839890. doi: 10.1155/2014/839890

Ben-Sasson, A., Hen, L., Fluss, R., Cermak, S. A., Engel-Yeger, B., and Gal, E. (2009). A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 39, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3

Bernier, R., Mao, A., and Yen, J. (2010). Psychopathology, families, and culture: autism. Child Adolesc Psychiat Clin 19, 855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.005

Bitsika, V., and Sharpley, C. F. (2004). Stress, anxiety and depression among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 14, 151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.011

Blakemore, S.-J., and Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65, 187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202

Bordini, D., Paula, C. S., Cunha, G. R., Caetano, S. C., Bagaiolo, L. F., Ribeiro, T. C., et al. (2020). A randomised clinical pilot trial to test the effectiveness of parent training with video modelling to improve functioning and symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 64, 629–643. doi: 10.1111/jir.12759

Bornstein, M. H. (2013). Parenting and child mental health: a cross-cultural perspective. World Psychiatry 12, 258–265. doi: 10.1002/wps.20071

Buescher, A. V., Cidav, Z., Knapp, M., and Mandell, D. S. (2014). Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 168, 721–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210

Burrell, T. L., and Borrego, J. R. (2012). Parents' involvement in ASD treatment: what is their role? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 19, 423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.04.003

Carey, A. C., Block, P., and Scotch, R. K. (2019). Sometimes allies: parent-led disability organizations and social movements. Disabil. Stud. Quarter. 39. doi: 10.18061/dsq.v39i1.6281

Casenhiser, D. M., Binns, A., Mcgill, F., Morderer, O., and Shanker, S. G. (2015). Measuring and supporting language function for children with autism: evidence from a randomized control trial of a social-interaction-based therapy. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 846–857. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2242-3

Chamak, B., Bonniau, B., Jaunay, E., and Cohen, D. (2008). What can we learn about autism from autistic persons? Psychother. Psychosom. 77, 271–279. doi: 10.1159/000140086

Chan, J. M., Lang, R., Rispoli, M., O’Reilly, M., Sigafoos, J., and Cole, H. (2009). Use of peer-mediated interventions in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Res. Autism. Spectr. Disord. 3, 876–889.

Chara, K. A., and Chara, P. J. (2004). Sensory smarts: a book for kids with ADHD or autism spectrum disorders struggling with sensory integration problems. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Cherewick, M., and Matergia, M. (2023). Neurodiversity in Practice: a Conceptual Model of Autistic Strengths and Potential Mechanisms of Change to Support Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing in Autistic Children and Adolescents. Adv. Neurodev. Disord.

Committee on Developing Evidence-Based Standards for Psychosocial Interventions for Mental DisordersBoard on Health Sciences PolicyInstitute of Medicine. (2015). “The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health,” in: Psychosocial Interventions for Mental and Substance Use Disorders: A Framework for Establishing Evidence-Based Standards. eds. M. J. England, A. S. Butler, and M. L. Gonzalez, (Washington, DC: National Academies Press).

Corsello, C. M. (2005). Early intervention in autism. Infants Young Child. 18, 74–85. doi: 10.1097/00001163-200504000-00002

Craig, J., and Baron-Cohen, S. (1999). Creativity and imagination in autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 319–326. doi: 10.1023/A:1022163403479

Crone, E. A., and Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313

Crone, E. A., and Fuligni, A. J. (2020). Self and others in adolescence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71, 447–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050937

Cruz, C. M., Giri, P., Vanderburg, J. L., Ferrarone, P., Bhattarai, S., Giardina, A. A., et al. (2021). The potential emergence of “education as mental health therapy” as a feasible form of teacher-delivered child mental health care in a low and middle income country: a mixed methods pragmatic pilot study. Front. Psych. 12:790536. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.790536

Davidson, J. (2010). ‘It cuts both ways’: a relational approach to access and accommodation for autism. Soc. Sci. Med. 70, 305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.017

Davis, N. O., and Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: associations with child characteristics. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 38, 1278–1291. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z

Dawson, M., and Mottron, L. Where autistics excel: Compiling an inventory of autistic cognitive strengths. Chicago. IL: International Meeting for Autism Research, (2009).

Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., et al. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the early start Denver model. Pediatrics 125, e17–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958

Dawson, G., and Watling, R. (2000). Interventions to facilitate auditory, visual, and motor integration in autism: a review of the evidence. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 30, 415–421. doi: 10.1023/A:1005547422749

Deanna, L. S., and Dana, L. B. (2011). “The Financial Side of Autism: Private and Public Costs,” in A Comprehensive Book on Autism Spectrum Disorders. ed. M. Mohammad-Reza, Rijeka: IntechOpen.

De Leeuw, A., Happé, F., and Hoekstra, R. A. (2020). A conceptual framework for understanding the cultural and contextual factors on autism across the globe. Autism Res. 13, 1029–1050. doi: 10.1002/aur.2276

Deshmukh, V., Mohapatra, A., Gulati, S., Nair, M., Bhutani, V., and Silberg, D. (2013). Prevalence of neuro-developmental disorders in India: Poster presentation. West Hartford: IMFAR, 76.

Disalvo, C. A., and Oswald, D. P. (2002). Peer-mediated interventions to increase the social interaction of children with autism: consideration of peer expectancies. Focus Autism Develop. Disabil. 17, 198–207. doi: 10.1177/10883576020170040201

Divan, G., Hamdani, S. U., Vajartkar, V., Minhas, A., Taylor, C., Aldred, C., et al. (2015). Adapting an evidence-based intervention for autism spectrum disorder for scaling up in resource-constrained settings: the development of the PASS intervention in South Asia. Glob. Health Action 8:27278. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27278

Divan, G., Vajaratkar, V., Cardozo, P., Huzurbazar, S., Verma, M., Howarth, E., et al. (2019). The feasibility and effectiveness of PASS plus, a lay health worker delivered comprehensive intervention for autism Spectrum disorders: pilot RCT in a rural low and middle income country setting. Autism Res. 12, 328–339. doi: 10.1002/aur.1978

Donohue, M. R., Childs, A. W., Richards, M., and Robins, D. L. (2019). Race influences parent report of concerns about symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. Autism 23, 100–111. doi: 10.1177/1362361317722030

Durkin, M. S., Elsabbagh, M., Barbaro, J., Gladstone, M., Happe, F., Hoekstra, R. A., et al. (2015). Autism screening and diagnosis in low resource settings: challenges and opportunities to enhance research and services worldwide. Autism Res. 8, 473–476. doi: 10.1002/aur.1575

Ebbels, S. H., Mccartney, E., Slonims, V., Dockrell, J. E., and Norbury, C. F. (2019). Evidence-based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 54, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12387

Ellis, A., and Dryden, W. (2007). The practice of rational emotive behavior therapy. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Estes, A., Munson, J., Dawson, G., Koehler, E., Zhou, X.-H., and Abbott, R. (2009). Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism 13, 375–387. doi: 10.1177/1362361309105658

Fazlioglu, Y., and Baran, G. (2008). A sensory integration therapy program on sensory problems for children with autism. Percept. Mot. Skills 106, 115–422. doi: 10.2466/pms.106.2.415-422

Fleming, B., Hurley, E., and Mason, J. (2015). Choosing autism interventions: A research-based guide. Hove, UK: Pavilion Publishing and Media Limited.

Fombonne, E. (2009). Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr. Res. 65, 591–598. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e7203

Ganz, M. L. (2007). The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 161, 343–349. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.4.343

Gibson, J. L., Pritchard, E., and De Lemos, C. (2021). Play-based interventions to support social and communication development in autistic children aged 2–8 years: a scoping review. Autism Develop. Lang. Impair. 6:23969415211015840. doi: 10.1177/23969415211015840

Green, J. (2019). Editorial Perspective: Delivering autism intervention through development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 60, 1353–1356. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13110

Greenough, W. T., Black, J. E., and Wallace, C. S. (2002). Experience and brain development. Child develop. 58, 539–559.

Guralnick, M. J. (2019). Effective early intervention: The developmental systems approach, Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing, Company.

Hagopian, A., Zuyderduin, A., Kyobutungi, N., and Yumkella, F. (2009). Job satisfaction and morale in the Ugandan health workforce: the Ministry of Health must focus on ways to keep health care workers from leaving their jobs—or leaving the country altogether. Health Aff. 28, w863–w875. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w863

Handleman, J. S., and Harris, S. L. (2001). Preschool education programs for children with autism. Austin, TX: Citeseer.

Harrell, L. G., Kamps, D., and Kravits, T. (1997). The effects of peer networks on social—communicative behaviors for students with autism. Focus Autism Develop. Disabil. 12, 241–256. doi: 10.1177/108835769701200406

Hastings, R. P., and Taunt, H. M. (2002). Positive perceptions in families of children with developmental disabilities. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 107, 116–127. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0116:PPIFOC>2.0.CO;2

Ho, M.-H., and Lin, L.-Y. (2020). Efficacy of parent-training programs for preschool children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 71:101495. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101495

Hodgetts, S., Zwaigenbaum, L., and Nicholas, D. (2015). Profile and predictors of service needs for families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 19, 673–683. doi: 10.1177/1362361314543531

Ingersoll, B., and Dvortcsak, A. (2019). Teaching Social Communication to Children with Autism and Other Developmental Delays, Second Edition: The Project ImPACT Manual for Parents, Guilford Publications.

Ireri, N. W., White, S. W., and Mbwayo, A. W. (2019). Treating anxiety and social deficits in children with autism Spectrum disorder in two schools in Nairobi, Kenya. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 3309–3315. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04045-6

Itzchak, E. B., and Zachor, D. A. (2011). Who benefits from early intervention in autism spectrum disorders? Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 5, 345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.04.018

Järbrink, K. (2007). The economic consequences of autistic spectrum disorder among children in a Swedish municipality. Autism 11, 453–463. doi: 10.1177/1362361307079602

Ji, C., and Yang, J. (2021). Effects of physical exercise and virtual training on visual attention levels in children with autism Spectrum disorders. Brain Sci. 12:41. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12010041

Kanagaraj, S., Kancharla, K., Sridhar, O. T. S., Lakshmi, R. V., Karthikeyan, S., Gopal, C. N. R., et al. (2022). A randomized control trial of cognitive behavior and emotional enhancement intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Adv. Neurodevelop. Disord. 7, 203–212. doi: 10.1007/s41252-022-00283-5

Kogan, M. D., Strickland, B. B., Blumberg, S. J., Singh, G. K., Perrin, J. M., and Van Dyck, P. C. (2008). A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics 122, e1149–e1158. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1057

Kohrt, B. A., Asher, L., Bhardwaj, A., Fazel, M., Jordans, M. J., Mutamba, B. B., et al. (2018). The role of communities in mental health care in low-and middle-income countries: a meta-review of components and competencies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:1279. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061279

Kolehmainen-Aitken, R.-L. (2004). Decentralization's impact on the health workforce: perspectives of managers, workers and national leaders. Hum. Resour. Health 2, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-5

Kumar, S. V., Narayan, S., Malo, P. K., Bhaskarapillai, B., Thippeswamy, H., Desai, G., et al. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of early childhood intervention programs for developmental difficulties in low-and-middle-income countries. Asian J. Psychiatr. 70:103026. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103026

Kuper, H., Hameed, S., Reichenberger, V., Scherer, N., Wilbur, J., Zuurmond, M., et al. (2021). Participatory research in disability in low-and middle-income countries: what have we learnt and what should we do? Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 23, 328–337. doi: 10.16993/sjdr.814

Lam, C. B., Mchale, S. M., and Crouter, A. C. (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Dev. 85, 1677–1693. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12235

Laushey, K. M., and Heflin, L. J. (2000). Enhancing social skills of kindergarten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 30, 183–193. doi: 10.1023/A:1005558101038

Lease, H., Hendrie, G. A., Poelman, A. A., Delahunty, C., and Cox, D. N. (2016). A sensory-diet database: a tool to characterise the sensory qualities of diets. Food Qual. Prefer. 49, 20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.11.010

Leung, C., Chan, S., Lam, T., Yau, S., and Tsang, S. (2016). The effect of parent education program for preschool children with developmental disabilities: a randomized controlled trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 56, 18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.015

Liang, S., Zheng, R. X., Zhang, L. L., Liu, Y. M., Ge, K. J., Zhou, Z. Y., et al. (2022). Effectiveness of parent-training program on children with autism spectrum disorder in China. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 68, 495–499. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2020.1813063

Lord, C., and Spence, S. J. (2006). “Autism Spectrum Disorders: Phenotype and Diagnosis,” in Understanding autism: From basic neuroscience to treatment. eds. S. O. Moldin and J. L. R. Rubenstein (CRC Press/Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), pp. 1–23.

Lovullo, S. V., and Matson, J. L. (2009). Comorbid psychopathology in adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 30, 1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.05.004

Lyall, K., Croen, L., Daniels, J., Fallin, M. D., Ladd-Acosta, C., Lee, B. K., et al. (2017). The changing epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu. Rev. Public Health 38, 81–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044318

Malucelli, E. R. S., Antoniuk, S. A., and Carvalho, N. O. (2021). The effectiveness of early parental coaching in the autism spectrum disorder. J. Pediatr. 97, 453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.09.004

Mandell, D. S., and Novak, M. (2005). The role of culture in families' treatment decisions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 11, 110–115. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20061

Mannion, A., Leader, G., and Healy, O. (2013). An investigation of comorbid psychological disorders, sleep problems, gastrointestinal symptoms and epilepsy in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 7, 35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.05.002

Manohar, H., Kandasamy, P., Chandrasekaran, V., and Rajkumar, R. P. (2019). Brief parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: a feasibility study from South India. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 3146–3158. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04032-x

Mariga, L., and Mcconkey, R. (2014). Inclusive education in low-income countries: a resource book for teacher educators, parent trainers and community development. Cape Town, South Africa: African Books Collective.

Matergia, M., Ferrarone, P., Khan, Y., Matergia, D. W., Giri, P., Thapa, S., et al. (2019). Lay field-worker–led school health program for primary schools in low-and middle-income countries. Pediatrics 143. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0975

Matson, J. L., and Rivet, T. T. (2008). Characteristics of challenging behaviours in adults with autistic disorder, PDD-NOS, and intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 33, 323–329. doi: 10.1080/13668250802492600

Mcconachie, H., and Diggle, T. (2007). Parent implemented early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 13, 120–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00674.x

Mcconnell, S. R. (2002). Interventions to facilitate social interaction for young children with autism: review of available research and recommendations for educational intervention and future research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 32, 351–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1020537805154

Mitter, N., Ali, A., and Scior, K. (2019). Stigma experienced by families of individuals with intellectual disabilities and autism: a systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 89, 10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2019.03.001

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med, 3, e123–30.

Mottron, L. (2017). Should we change targets and methods of early intervention in autism, in favor of a strengths-based education? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 815–825. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-0955-5

Mottron, L., Belleville, S., Rouleau, G. A., and Collignon, O. (2014). Linking neocortical, cognitive, and genetic variability in autism with alterations of brain plasticity: the trigger-threshold-target model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 47, 735–752. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.012

Mottron, L., Bouvet, L., Bonnel, A., Samson, F., Burack, J. A., Dawson, M., et al. (2013). Veridical mapping in the development of exceptional autistic abilities. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 209–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.016

Nevill, R. E., Lecavalier, L., and Stratis, E. A. (2018). Meta-analysis of parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 22, 84–98. doi: 10.1177/1362361316677838

Nnamani, A., Akabogu, J., Otu, M. S., Uloh-Bethels, A. C., Ukoha, E., Iyekekpolor, O. M., et al. (2019). Using rational-emotive language education to improve communication and social skills of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders in Nigeria. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e16550. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016550

Norbury, C. F., and Sparks, A. (2013). Difference or disorder? Cultural issues in understanding neurodevelopmental disorders. Dev. Psychol. 49, 45–58. doi: 10.1037/a0027446

Oono, I. P., Honey, E. J., and Mcconachie, H. (2013). Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Evid. Based Child Health 8, 2380–2479. doi: 10.1002/ebch.1952

Orben, A., Tomova, L., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adoles Health 4, 634–640. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3

Padmanabha, H., Singhi, P., Sahu, J. K., and Malhi, P. (2019). Home-based sensory interventions in children with autism Spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Pediatr. 86, 18–25. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2747-4

Pajareya, K., and Nopmaneejumruslers, K. (2011). A pilot randomized controlled trial of DIR/Floortime™ parent training intervention for pre-school children with autistic spectrum disorders. Autism 15, 563–577. doi: 10.1177/1362361310386502

Pervin, M., Ahmed, H. U., and Hagmayer, Y. (2022). Effectiveness of interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in high-income vs. lower middle-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews and research papers from LMIC. Front. Psychiatry 13:834783. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.834783

Pfeifer, J. H., and Berkman, E. T. (2018). The development of self and identity in adolescence: neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 158–164. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12279

Pfeiffer, B. A., Koenig, K., Kinnealey, M., Sheppard, M., and Henderson, L. (2011). Effectiveness of sensory integration interventions in children with autism spectrum disorders: a pilot study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 65, 76–85. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.09205

Phetrasuwan, S., and Shandor Miles, M. (2009). Parenting stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 14, 157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00188.x

Piravej, K., Tangtrongchitr, P., Chandarasiri, P., Paothong, L., and Sukprasong, S. (2009). Effects of Thai traditional massage on autistic children's behavior. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 15, 1355–1361. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0258

Pruitt, S. D., and Epping-Jordan, J. E. (2005). Preparing the 21st century global healthcare workforce. BMJ 330, 637–639. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.637

Rahman, A., Divan, G., Hamdani, S. U., Vajaratkar, V., Taylor, C., Leadbitter, K., et al. (2016). Effectiveness of the parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder in South Asia in India and Pakistan (PASS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 128–136. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00388-0

Reaven, J. A. (2009). Children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and co-occurring anxiety symptoms: implications for assessment and treatment. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 14, 192–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00197.x

Rogge, N., and Janssen, J. (2019). The economic costs of autism spectrum disorder: a literature review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 49, 2873–2900. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04014-z

Rojas-Torres, L. P., Alonso-Esteban, Y., and Alcantud-Marín, F. (2020). Early intervention with parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a review of programs. Children 7:294. doi: 10.3390/children7120294

Russell, G., Kapp, S. K., Elliott, D., Elphick, C., Gwernan-Jones, R., and Owens, C. (2019). Mapping the autistic advantage from the accounts of adults diagnosed with autism: a qualitative study. Autism Adulthood 1, 124–133. doi: 10.1089/aut.2018.0035

Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., Landa, R., Rogers, S. J., Mcgee, G. G., et al. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 2411–2428. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8

Shulman, E. P., Smith, A. R., Silva, K., Icenogle, G., Duell, N., Chein, J., et al. (2016). The dual systems model: review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 17, 103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.010

Smith, T. (2010). “Early and intensive behavioral intervention in autism,” in Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. eds. J. R. Weisz and A. E. Kazdin (The Guilford Press), pp. 312–326.

Smith, C., Goddard, S., and Fluck, M. (2004). A scheme to promote social attention and functional language in young children with communication difficulties and autistic spectrum disorder. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 20, 319–333. doi: 10.1080/0266736042000314268

Smith, L., Malcolm-Smith, S., and De Vries, P. J. (2017). Translation and cultural appropriateness of the autism diagnostic observation Schedule-2 in Afrikaans. Autism 21, 552–563. doi: 10.1177/1362361316648469

Solomon, M., Goodlin-Jones, B. L., and Anders, T. F. (2004). A social adjustment enhancement intervention for high functioning autism, Asperger’s syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder NOS. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 34, 649–668. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-5286-y

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Rev. 28, 78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002

Sterne, J. A., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., et al. (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

Strasser, R. (2003). Rural health around the world: challenges and solutions. Fam. Pract. 20, 457–463. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg422

Vismara, L. A., and Rogers, S. J. (2008). The early start Denver model: a case study of an innovative practice. J. Early Interv. 31, 91–108. doi: 10.1177/1053815108325578

Vohra, R., Madhavan, S., and Sambamoorthi, U. (2017). Comorbidity prevalence, healthcare utilization, and expenditures of Medicaid enrolled adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 21, 995–1009. doi: 10.1177/1362361316665222

White, S. W., Ollendick, T., Albano, A. M., Oswald, D., Johnson, C., Southam-Gerow, M. A., et al. (2013). Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43, 382–394. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x

World Bank. (2022). World Bank data [online]. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country (Accessed July 13, 2023 2022).

Wyatt Kaminski, J., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., and Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 36, 567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9

Xu, Y., Yang, J., Yao, J., Chen, J., Zhuang, X., Wang, W., et al. (2018). A pilot study of a culturally adapted early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders in China. J. Early Interv. 40, 52–68. doi: 10.1177/1053815117748408

Zhang, B., Liang, S., Chen, J., Chen, L., Chen, W., Tu, S., et al. (2022). Effectiveness of peer-mediated intervention on social skills for children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Pediatr 11, 663–675. doi: 10.21037/tp-22-110

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, child, adolescent, psychosocial, low- and lower-middle-income countries, non-specialist, mental health

Citation: Cherewick M, Daniel C, Shrestha CC, Giri P, Dukpa C, Cruz CM, Rai RP and Matergia M (2023) Psychosocial interventions for autistic children and adolescents delivered by non-specialists in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 14:1181976. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1181976

Received: 08 March 2023; Accepted: 24 July 2023;

Published: 07 August 2023.

Edited by:

Pamela Bryden, Wilfrid Laurier University, CanadaReviewed by:

Mahnaz Ilkhani, Shahid Beheshti University, IranCopyright © 2023 Cherewick, Daniel, Shrestha, Giri, Dukpa, Cruz, Rai and Matergia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Megan Cherewick, bWVnYW4uY2hlcmV3aWNrQGN1YW5zY2h1dHouZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.