94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 15 May 2023

Sec. Positive Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1180995

This article is part of the Research TopicHealth and Well-being, Quality Education, Gender Equality, Decent work and Inequalities: The contribution of psychology in achieving the objectives of the Agenda 2030View all 13 articles

Introduction: The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development aims to contribute to the establishment of a culture of sustainability regarding the 2030 Agenda and its 17 sustainable development goals.

Methods: In this framework, this study examined the associations between acceptance of change and well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic sides), controlling for the effects of personality traits, in 284 Italian university students.

Results: Acceptance of change explained additional variance over personality traits regarding hedonic and eudaimonic well-being.

Discussion: Acceptance of change could thus represent a promising well-being resource from the perspective of strength-based prevention, opening future perspectives to face the challenges of sustainable development, particularly concerning Goal 3 of the 2030 Agenda: “Good health and well-being.”

The 2030 Agenda of the United Nations has advanced 17 sustainable development goals (see Table 1) to promote sustainability worldwide. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development (PSSD) (Di Fabio and Rosen, 2018, 2020; Rosen and Di Fabio, n.d.) is a current research area contributing to the transdisciplinary framework of sustainability science (Rosen, 2017), and it supports a preventive culture regarding the 2030 Agenda and its 17 sustainable development goals.

Currently, we are facing enormous challenges in an even more turbulent scenario than that which appeared at the beginning of the 21st century (Blustein et al., 2019); it is impacting the labor market and is characterized by change and instability. This new scenario is accelerating and increasing in intensity: on the one hand are acceleration, change, and precariousness; on the other hand are pandemics, war, climatic changes, etc. To deal with these changeable and demanding new contexts, people must adapt incessantly to change, and strength is required to constructively cope with change (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a). Individuals who consider change as a possibility to discover and develop have a higher probability of responding positively to the difficulties of the present scenario (Blustein et al., 2019), successfully facing threats and shifts and thus enhancing well-being (Di Fabio and Kenny, 2016).

The concept of acceptance of change (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a) refers to the tendency to encompass change. It includes the following factors: predisposition to change—the perception of individuals that they might acquire something as a result of change by utilizing change to increase the quality of their lives; support for change—support is perceived to be received from other people in the face of changes; change seeking—behavior where a person pursues change; acquiring and retaining information as well as exhibiting a need to receive novel stimulation; a positive reaction to change as perceived by positive emotions resulting from changing; positively experiencing and benefiting from change. Cognitive flexibility is perceived as having the “ability to think about multiple concepts simultaneously, to change decisions if this is advantageous, and to change plans and routines easily” (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a, p. 2).

Resistance to change (Oreg, 2003) has traditionally been studied in literature and is considered the dark side of change processes. With the introduction of the acceptance of change (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a), a new positive preventive perspective was proposed concerning change processes based on promoting resources and not only on reducing dysfunctionalities (Di Fabio, 2017a). From this perspective, acceptance of change is conceptualized as a resource to constructively face changes, permitting individuals to find ways to deal successfully with challenges and promote their well-being (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a). This perspective is in line with positive psychology (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Seligman, 2002), which is focused on the study of well-being by considering human strengths instead of failures. In this framework, the acceptance of change represents a positive resource for individuals to cope with the complex challenges they can meet in their lives.

Occupational health psychology has emphasized the value of a positive health perspective by considering the relevance of promoting the health, well-being, flourishing, and optimal functioning of workers (Tetrick and Peiró, 2012). It is proposed (Di Fabio et al., 2020) that this positive approach is integrated with a strength-based prevention perspective (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2021) for healthy organizations. The focus is on a primary preventive approach focused on building workers’ positive individual resources for enhancing both well-being and performance in organizations (Di Fabio et al., 2020), thus facilitating the achievement of the third goal of the 2030 Agenda, “Good health and well-being.”

According to this perspective, well-being has to be considered both from the hedonic (Kahneman et al., 1999) and eudaimonic perspectives (Ryff and Singer, 2008) as well as from strength-based prevention perspectives (Di Fabio and Saklofske, 2021) considering the crucial asset of constructing personal resources (Di Fabio and Kenny, 2021) to foster well-being. In this preventive framework, including a primary preventive perspective (Di Fabio and Kenny, 2021), the acceptance of change is conceived as a promising resource related to well-being, advancing the research related to determinants of well-being, personality factors, and personal and environmental resources (Ramaci et al., 2020; Bellini et al., 2022; De Giorgio et al., 2023).

In the literature, some constructs holding the same perspective of acceptance of change in organizations were studied in relation to well-being: readiness for change (Helfrich et al., 2018), commitment to change (Jing et al., 2014), and change culture (Quigley et al., 2022). Specifically, regarding the relationships between acceptance of change and well-being, acceptance of change was positively associated with both hedonic well-being (life satisfaction) and eudaimonic well-being (flourishing) in workers and students (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a). Another study (Di Fabio et al., 2016) conducted on Italian workers reported positive correlations between acceptance of change and both life satisfaction and meaning in life. Furthermore, two further studies conducted on Italian workers indicated that acceptance of change was positively linked to job satisfaction (Di Fabio and Gori 2020; Gori and Topino, 2020). In this context, acceptance of change appears particularly promising in relation to “good health and well-being,” the third of the 17 SDGs of the 2030 Agenda of the United Nations. Therefore, acceptance of change emerges as a deeply embedded theme in the PSSD research area (Di Fabio, 2017a,b; Di Fabio and Rosen, 2018, 2020), which also highlights the importance of prevention.

Analyzing the literature, to the best of our knowledge, no research exists that has specifically studied the relationships between the acceptance of change construct (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a) and well-being that also considers personality traits. Furthermore, concerning the acceptance of change, no studies have simultaneously considered the following aspects of hedonic well-being: positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction; and the same can be said for the following aspects of eudaimonic well-being: meaning in life and flourishing. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed: acceptance of change explains additional variance regarding positive affect (H1), negative affect (H2), life satisfaction (H3), meaning in life (H4), and flourishing (H5) beyond that accounted for by personality traits.

A total of 284 university psychology students from the University of Florence (28.52% male and 71.48% female; mean age = 22.81 years, SD = 1.88) participated in the study. University students participated voluntarily in the study and were not compensated. They provided informed consent. Instruments were administered to groups by specialized personnel adhering to Italian privacy laws (DL-196/2003; EU 2016/679). The administration order of the measures was balanced to contain the presentation order effects. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Integrated Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Institute (IPPI) (IPPI Ethical Committee Number 016/2022).

Big five questionnaire (BFQ; Caprara et al., 1993), 132 items (1–5, from «Absolutely false» to «Absolutely true»), five factors: emotional stability (Alpha = 0.90), extraversion (Alpha = 0.81), conscientiousness (Alpha = 0.81), Openness (Alpha = 0.75), and Agreeableness (Alpha = 0.73).

Acceptance of change scale (ACS; Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a), 20 items (1–5, from «Not at all » to «A great deal»), five dimensions: predisposition to change (Alpha = 0.83), support for change (Alpha = 0.79), change seeking (Alpha = 0.80), positive reaction to change (Alpha = 0.75), and cognitive flexibility (Alpha = 0.72).

Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988; Italian version Terraciano et al., 2003), 20 adjectives (1–5, from «Very slightly or not at all» to «Extremely»), PA (Alpha = 0.83), and NA (Alpha = 0.85).

Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985, Italian version, Di Fabio and Gori, 2016b): 5 items (1–7, from «Strongly disagree» to «Strongly agree») and Alpha coefficient: 0.85.

Meaning in life measure (MLM; Morgan and Farsides, 2009, Italian version Di Fabio, 2014): 23 items (1–7, from «Strongly disagree» to «Strongly agree»), five dimensions: exciting life, accomplished life, principled life, purposeful life, valued life, and alpha coefficient: 0.85 (total score).

Flourishing scale (FS; Diener et al., 2010, Italian version by Di Fabio, 2016): 8 items (1–7, from «Strongly disagree» to «Strongly agree») and Alpha coefficient: 0.88.

Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s r correlations, and hierarchical regressions were calculated using the IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 28). We carried out hierarchical regressions with personality traits during the first step, acceptance of change dimensions during the second step, and alternated positive affect, negative affect, satisfaction with life, meaning in life, and flourishing as the dependent variables.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the study variables.

Table 3 presents Pearson’s r correlations for the study variables.

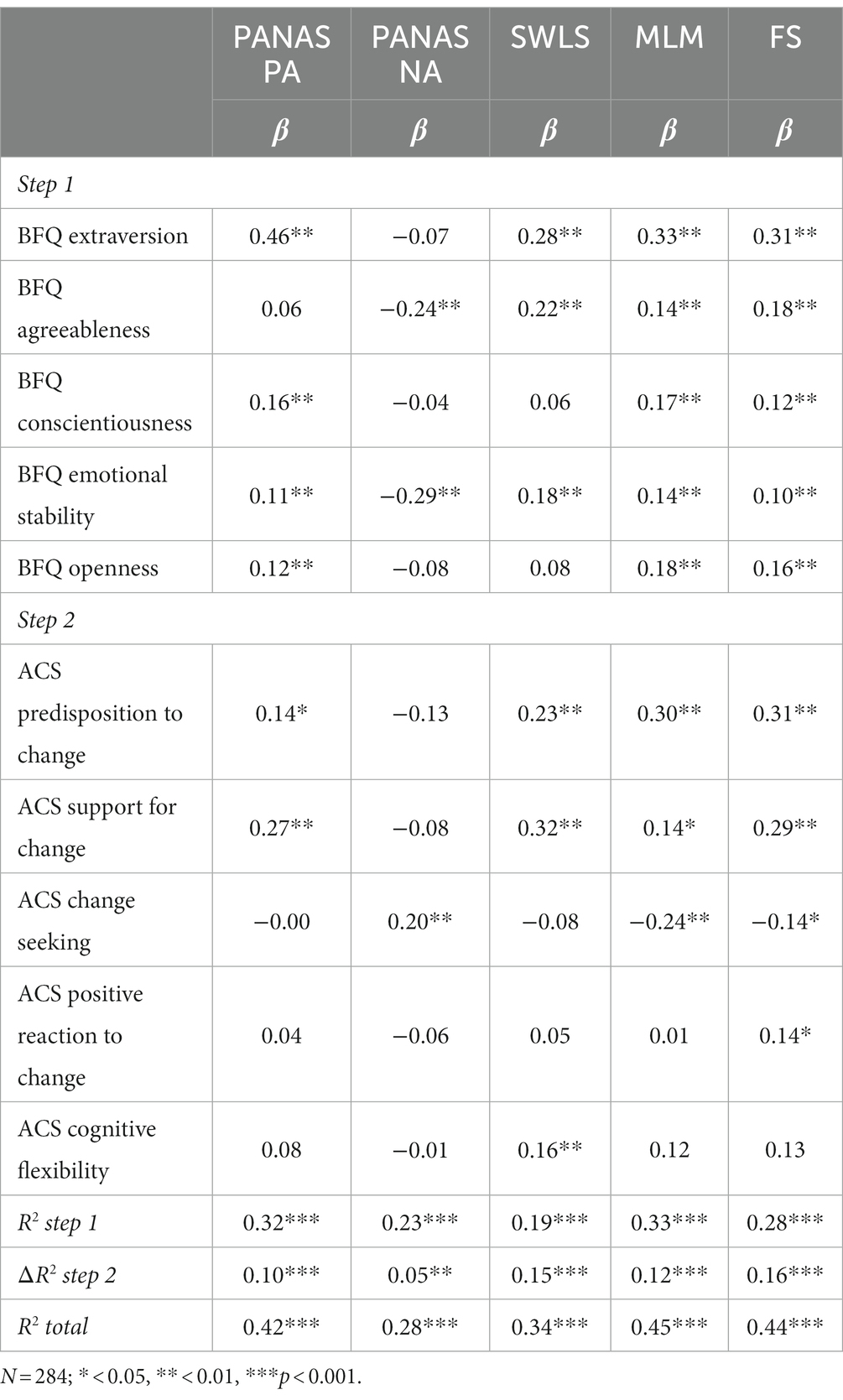

Table 4 presents the results of the hierarchical regressions.

Table 4. Hierarchical regression: contribution of big five (BFQ) and ACS dimensions in relation to PANAS, SWLS, MLM, FS.

Regarding positive affect, BFQ explained 32% of the variance, and the ACS dimensions explained 10%, for a total variance of 42%.

Regarding negative affect, BFQ explained 23% of the variance, and the ACS dimensions explained 5%, for a total variance of 28%.

Regarding satisfaction with life, BFQ explained 19% of the variance, and the ACS dimensions added 15%, for a total variance of 34%.

Concerning meaning in life, the BFQ explained 33% of the variance, and the ACS dimensions added 12%, for a total variance of 45%.

Concerning flourishing, BFQ explained 28% of the variance, and the ACS dimensions added 16%, for a total variance of 44%.

This study analyzed, for the first time, the associations between the acceptance of change construct (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a) and both hedonic (PA, NA, SWLS) and eudaimonic well-being (MLM, FS), considering personality traits, in Italian university students. Our findings support this hypothesis.

Regarding hedonic well-being, the results confirmed the first hypothesis. Acceptance of change explained additional variance to the big five for positive affect. Particularly, regarding positive affect, positive significant relationships emerged with the predisposition to change dimension as well as with support for changing dimension. Aspects of acceptance of change relative to individuals’ perceptions of acquiring from change and applying changes to increase their quality of life as well as perceiving social support in coping with changes (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a) are related to the propensity to experience positive emotions (Watson et al., 1988). These results highlighted that considering change as a positive challenge and perceiving support from others in facing change were associated with the positive affect experienced by the participants in this study.

The findings confirm the second hypothesis. Acceptance of change explained additional variance to the big five for negative affect. Particularly, negative affect indicated a significant direct relationship with the change-seeking dimension. This relationship is interesting, even if it may seem counterintuitive at first. In this study, a search for change was associated with the experience of negative affect, probably because the perception of looking for change and exhibiting a necessity for new stimuli (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a) could be connected to encountering the world more negatively (Watson et al., 1988), and perhaps a need for change could emerge.

Thus, the third hypothesis was confirmed. Acceptance of change explained the additional variance to the big five for life satisfaction. Particularly, life satisfaction was positively associated with support for change, predisposition to change, and cognitive flexibility dimensions, in this order of importance. In this study, different aspects of acceptance of change were associated with the global satisfaction of an individual’s existence (Diener et al., 1985): the perception of support received by others in facing change, primarily the perception of being predisposed to change, and the perception of having the capacity to shift between various conceptions using adaptive cognitive strategies. A global positive evaluation of one’s life includes aspects of relational satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985) and thus appears to be associated with the perception of being supported by others in the face of changes. Moreover, being satisfied with one’s life includes aspects related to a predisposition to change regarding the perception of having opportunities to learn from change as well as the perception of being able to face the challenges of life (Diener et al., 1985). Life satisfaction, as a cognitive aspect of hedonic well-being regarding favorable evaluation of personal life rather than present feelings (Diener et al., 1985), was also connected to the cognitive flexibility of acceptance of change in this study. It is worth emphasizing that life satisfaction was the only aspect of well-being significantly associated with the cognitive flexibility dimension of acceptance of change in this study, probably because these two variables are more closely linked to cognitive processes. The findings of this study, thus, documented the relationships between acceptance of change and diverse facets of hedonic well-being, even after considering personality.

Regarding eudaimonic well-being, our results confirmed the fourth hypothesis. Acceptance of change explained additional variance to the big five for meaning in life. Meaning in life indicated significant positive relationships with the predisposition to change and support for change dimensions and a significant inverse relationship with the change-seeking dimension. In this study, a greater acknowledgment and awareness of meaningful and authentic goals (Morgan and Farsides, 2009) is positively related to different features of acceptance of change regarding the perception of being predisposed to change and being supported by others when facing changes. The findings emphasize the value of a positive attitude toward change concerning predisposition to change and support for change in eudaimonic well-being as authenticity and self-realization. The inverse relationship between the change-seeking dimension and meaning in life could highlight that the participants in this study, seeking new stimuli and probably experiencing a less meaningful life, could be pushed towards novelties.

Finally, the fifth hypothesis was confirmed. Acceptance of change explained the additional variance to the big five for flourishing. Particularly, flourishing indicated significant positive relationships with the predisposition to change, support for change, and positive reaction to change dimensions, whereas a significant inverse relationship emerged with the change-seeking dimension. It is possible to notice a more comprehensive form of eudaimonic well-being, namely, flourishing, defining it as the perception of psychological well-being concerning “relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism” (Diener et al., 2010, p. 143) that resulted from the majority of the dimensions of acceptance of change, including also the positive reaction to change dimension. In this study, acceptance of change in terms of predisposition to change, support for change, and positive reaction to change seem to be relevant for achieving a form of eudaimonic well-being that permits flourishing, functioning optimally, and developing to the best of one’s possibilities (Diener et al., 2010). Furthermore, the link between flourishing and change seeking was inverse, indicating that in this study, when participants sought change, they appeared to experience less eudaimonic well-being regarding flourishing, just as the desire to change appears to be motivated by a desire to achieve greater overall eudaimonic well-being. Thus, acceptance of change emerged in this study regarding aspects of eudaimonic well-being concerning both meaning in life and flourishing.

Further reflections can be emphasized regarding the associations between acceptance of change and different forms of well-being. In this study, the contribution of acceptance of change was greater for the eudaimonic well-being aspect of flourishing, followed by satisfaction with life for hedonic well-being and meaning in life for eudaimonic well-being as the third aspect. Acceptance of change appears to be related to a great flourishing of eudaimonic well-being and, subsequently, be associated with a great cognitive reflection on global satisfaction with one’s own life (Diener et al., 1985) for hedonic well-being and is related to meaning in life (Morgan and Farsides, 2009) for eudaimonic well-being. In this study, the perception of accepting change seems to be relevant, particularly in forms of eudaimonic well-being as functioning optimally, emphasizing self-expression and self-realization (Diener et al., 2010), and adherence to authentic meanings and values (Morgan and Farsides, 2009), but also with hedonic well-being, especially regarding life satisfaction, suggesting that being open to changes could be linked to various types of well-being.

Despite the results obtained, this study has some limitations that must be addressed. First, a limitation relative to the participants is that students in psychology at the University of Florence were predominantly female. Even if this composition of the group of participants tends to reflect the distribution of gender among psychology students, it remains a limitation of this study. Future studies should be conducted considering a better balance between males and females, as well as the inclusion of students from various disciplines and from other universities in Italy. Future studies could extend this study to different international contexts. A further limitation is that the study used self-reported measures. The cross-sectional design constitutes another limitation, suggesting a longitudinal approach for future research. Additionally, future research could consider studying these relationships in students attending high school as well as in other targets, such as workers. With this latter target, future studies could also investigate the acceptance of change regarding other specific aspects of well-being at work, such as job satisfaction (Judge et al., 1998) and work meaning (Steger et al., 2012).

If these results are replicated, new perspectives on intervention can be opened. The current complex, unstable, and detonating scenario (Blustein et al., 2019) is calling for strength to cope with change in a constructive manner, and to successfully face transitions and adversities, so that the well-being of individuals is not threatened. In this scenario, acceptance of change emerges as a promising resource. In fact, acceptance of change is amenable to training, contrary to personality traits, which are generally stable (Costa and McCrae, 1992). Thus, helping individuals face the transforming and mutable environments of the current century effectively (Di Fabio and Gori, 2016a) could be a resource for enhancing their well-being. According to strength-based perspectives, especially in a primary preventive approach (Di Fabio and Kenny, 2021), acceptance of change could be configured as a promising resource to respond to the challenges connected in particular to the third sustainable development goal, “Good health and well-being” (SDG 3). Furthermore, from these perspectives, early preventive actions on acceptance of change for university students could also address the challenges of decent education (Duffy et al., 2022) and decent work (Duffy et al., 2017; Di Fabio and Kenny, 2019; Svicher et al., 2022). Improving resources for change in young people as future workers in organizations (Di Fabio and Blustein, 2016) could promote decent work as the eighth sustainable development goal (SDG8). Early preventive actions enhancing acceptance of change could also better deal with the challenges relative to all other sustainable development goals (SDGs) for the promotion and establishment of a culture of sustainability and sustainable development.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Integrated Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Institute (IPPI). IPPI Ethical Committee Number 016/2022. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ADF conceptualized the paper. ADF, LP, AB, AG, and AS contributed to the data collection. LP ran statistical analyses. ADF and LP wrote the first draft of the paper. ADF, AS, and AG edited and wrote the final draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bellini, D., Barbieri, B., Barattucci, M., Mascia, M. L., and Ramaci, T. (2022). The role of a restorative resource in the academic context in improving intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and flow within the job demands–resources model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:15263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192215263

Blustein, D. L., Kenny, M. E., Di Fabio, A., and Guichard, J. (2019). Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. J. Career Assess. 27, 3–28. doi: 10.1177/1069072718774002

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., and Borgogni, L. (1993). BFQ: big five questionnaire. 2nd Edn. Florence, Italy:Giunti O.S.

Costa, P. T., and McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO PI-R professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

De Giorgio, A., Barattucci, M., Teresi, M., Raulli, G., Ballone, C., Ramaci, T., et al. (2023). Organizational identification as a trigger for personal well-being: associations with happiness and stress through job outcomes. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 33, 138–151. doi: 10.1002/casp.2648

Di Fabio, A. (2014). Meaningful life measure: primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana [meaningful life measure: first contribution to the validation of the Italian version]. Counseling Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni 7, 307–315. doi: 10.1037/t54712-000

Di Fabio, A. (2016). Flourishing scale: primo contributo alla validazione della versione italiana [flourishing scale: first contribution to the validation of the Italian version] counseling. Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni 9. doi: 10.14605/CS911606

Di Fabio, A. (2017a). Positive healthy organizations: promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 8:1938. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01938

Di Fabio, A. (2017b). The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 8:1534. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01534

Di Fabio, A., and Blustein, D. L. (2016). Editorial: from meaning of working to meaningful lives: the challenges of expanding decent work. Front. Psychol. 7:1119. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01119

Di Fabio, A., Cheung, F., and Peiró, J.-M. (2020). Editorial special issue personality and individual differences and healthy organizations. Pers. Individ. Diff. 166:110196. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110196

Di Fabio, A., Giannini, M., Loscalzo, Y., Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., Guazzini, A., et al. (2016). The challenge of fostering healthy organizations: an empirical study on the role of workplace relational civility in acceptance of change, and well-being. Front. Psychol. 7:1748. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01748

Di Fabio, A., and Gori, A. (2016a). Developing a new instrument for assessing acceptance of change. Front. Psychol. 7:802. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00802

Di Fabio, A., and Gori, A. (2016b). Measuring adolescent life satisfaction: psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of Italian adolescents and young adults. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 34, 501–506. doi: 10.1177/0734282915621223

Di Fabio, A., and Gori, A. (2020). Satisfaction with life scale among italian workers: reliability, factor structure and validity through a big sample study. Sustainability 12:5860. doi: 10.3390/su12145860

Di Fabio, A., and Kenny, M. E. (2016). Promoting well-being: the contribution of emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 7:1182. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01182

Di Fabio, A., and Kenny, M. E. (2019). Decent work in Italy: context, conceptualization, and assessment. J. Vocat. Behav. 110, 131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.014

Di Fabio, A., and Kenny, M. E. (2021). Positive and negative effects and meaning at work: trait emotional intelligence as a primary prevention resource in organizations for sustainable and positive human capital development. In A. FabioDi (Ed.), Cross-cultural perspectives on well-being and sustainability in organizations. (Switzerland: Springer), 139–152.

Di Fabio, A., and Rosen, M. A. (2018). Opening the black box of psychological processes in the science of sustainable development: a new frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2:47. doi: 10.20897/ejosdr/3933

Di Fabio, A., and Rosen, M. A. (2020). An exploratory study of a new psychological instrument for evaluating sustainability: the sustainable development goals psychological inventory. Sustainability 12:7617. doi: 10.3390/su12187617

Di Fabio, A., and Rosen, M. A. (n.d.). Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development in organizations: empirical evidence from environment to safety to innovation and future research. In A. FabioDi and C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development in organizations. (New York, NY:Routledge Taylor & Francis Group). in press.

Di Fabio, A., and Saklofske, D. H. (2021). The relationship of compassion and self-compassion with personality and emotional intelligence. Pers. Individ. Differ. 169:110109. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110109

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 97, 143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., England, J. W., Blustein, D. L., Autin, K. L., Douglass, R. P., et al. (2022). The development and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. J. Couns. Psychol. 64, 206–221. doi: 10.1037/cou0000191

Duffy, R. D., Kim, H. J., Perez, G., Prieto, C. G., Torgal, C., and Kenny, M. E. (2022). Decent education as a precursor to decent work: an overview and construct conceptualization. J. Vocat. Behav. 138:103771. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103771

Gori, A., and Topino, E. (2020). Predisposition to change is linked to job satisfaction: assessing the mediation roles of workplace relation civility and insight. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:2141. doi: 10.3390/su12197902

Helfrich, C. D., Kohn, M. J., Stapleton, A., Allen, C. L., Hammerback, K. E., Chan, K. G., et al. (2018). Readiness to change over time: change commitment and change efficacy in a workplace health-promotion trial. Front. Public Health 6:110. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00110

Jing, R., Lin Xie, J., and Ning, J. (2014). Commitment to organizational change in a Chinese context. J. Manag. Psychol. 29, 1098–1114. doi: 10.1108/JMP-08-2011-0042

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., and Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: the role of core evaluations. J. Appl. Psychol. 83, 17–34. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., and Schwarz, N. (Eds.) (1999). Well-being: foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, NY:Russell Sage Foundation.

Morgan, J., and Farsides, T. (2009). Psychometric evaluation of the meaningful life measure. J. Happiness Stud. 10, 351–366. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9093-6

Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: developing an individual differences measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 680–693. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.680

Quigley, J., and Lambe, K., Moloney, T., Farragher, L., Farragher, A., and Long, J. (2022). Promoting workplace health and wellbeing through culture change. An evidence review. Health Research Board. https://www.hrb.ie/

Ramaci, T., Rapisarda, V., Bellini, D., Mucci, N., De Giorgio, A., and Barattucci, M. (2020). Mindfulness as a protective factor for dissatisfaction in HCWs: the moderating role of mindful attention between climate stress and job satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:3818. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113818

Rosen, M. A. (2017). Sustainable development: a vital quest. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 1:2. doi: 10.20897/ejosdr.201702

Ryff, C. D., and Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: a eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 9, 13–39. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). “Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy” in Handbook of positive psychology. eds. C. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez (New York: Oxford University Press), 3–9.

Seligman, M. E. P., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., and Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: the work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 20, 322–337. doi: 10.1177/1069072711436

Svicher, A., Di Fabio, A., and Gori, A. (2022). Decent work in Italy: a network analysis. Aust. J. Career Dev. 31, 42–56. doi: 10.1177/10384162221089462

Terraciano, A., McCrae, R. R., and Costa, P. T. Jr. (2003). Factorial and construct validity of the Italian positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Eur. J. Psychol. 19, 131–141. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.19.2.131

Tetrick, L. E., and Peiró, J. M. (2012). Occupational safety and health. The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology. 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Keywords: acceptance of change, hedonic well-being, eudemonic well-being, personality traits, sustainability, sustainable development, good health and well-being

Citation: Di Fabio A, Palazzeschi L, Bonfiglio A, Gori A and Svicher A (2023) Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being for sustainable development in university students: personality traits or acceptance of change? Front. Psychol. 14:1180995. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1180995

Received: 16 March 2023; Accepted: 25 April 2023;

Published: 15 May 2023.

Edited by:

Paola Magnano, Kore University of Enna, ItalyReviewed by:

Emanuela Ingusci, University of Salento, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Di Fabio, Palazzeschi, Bonfiglio, Gori and Svicher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Annamaria Di Fabio, YW5uYW1hcmlhLmRpZmFiaW9AdW5pZmkuaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.