94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 26 October 2023

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1171993

This article is part of the Research TopicMindfulness-Based Interventions in Clinical Settings: Are There Benefits for Both Patients and Their Physicians?View all 7 articles

Gretchen Roman1,2*

Gretchen Roman1,2* Reza Yousefi-Nooraie1

Reza Yousefi-Nooraie1 Paul Vermilion3

Paul Vermilion3 Anapaula Cupertino1,4

Anapaula Cupertino1,4 Steven Barnett2

Steven Barnett2 Ronald Epstein2

Ronald Epstein2Introduction: Medical interpreters experience emotional burdens from the complex demands at work. Because communication access is a social determinant of health, protecting and promoting the health of medical interpreters is critical for ensuring equitable access to care for language-minority patients. The purpose of this study was to pilot a condensed 8-h program based on Mindful Practice® in Medicine addressing the contributors to distress and psychosocial stressors faced by medical sign and spoken language interpreters.

Methods: Using a single-arm embedded QUAN(qual) mixed-methods pilot study design, weekly in-person 1-h sessions for 8 weeks involved formal and informal contemplative practice, didactic delivery of the week's theme (mindfulness, noticing, teamwork, suffering, professionalism, uncertainty, compassion, and resilience), and mindful inquiry exercises (narrative medicine, appreciative interviews, and insight dialog). Quantitative well-being outcomes (mean±SEM) were gathered via survey at pre-, post-, and 1-month post-intervention time points, compared with available norms, and evaluated for differences within subjects. Voluntary feedback about the workshop series was solicited post-intervention via a free text survey item and individual exit interviews. A thematic framework was established by way of qualitative description.

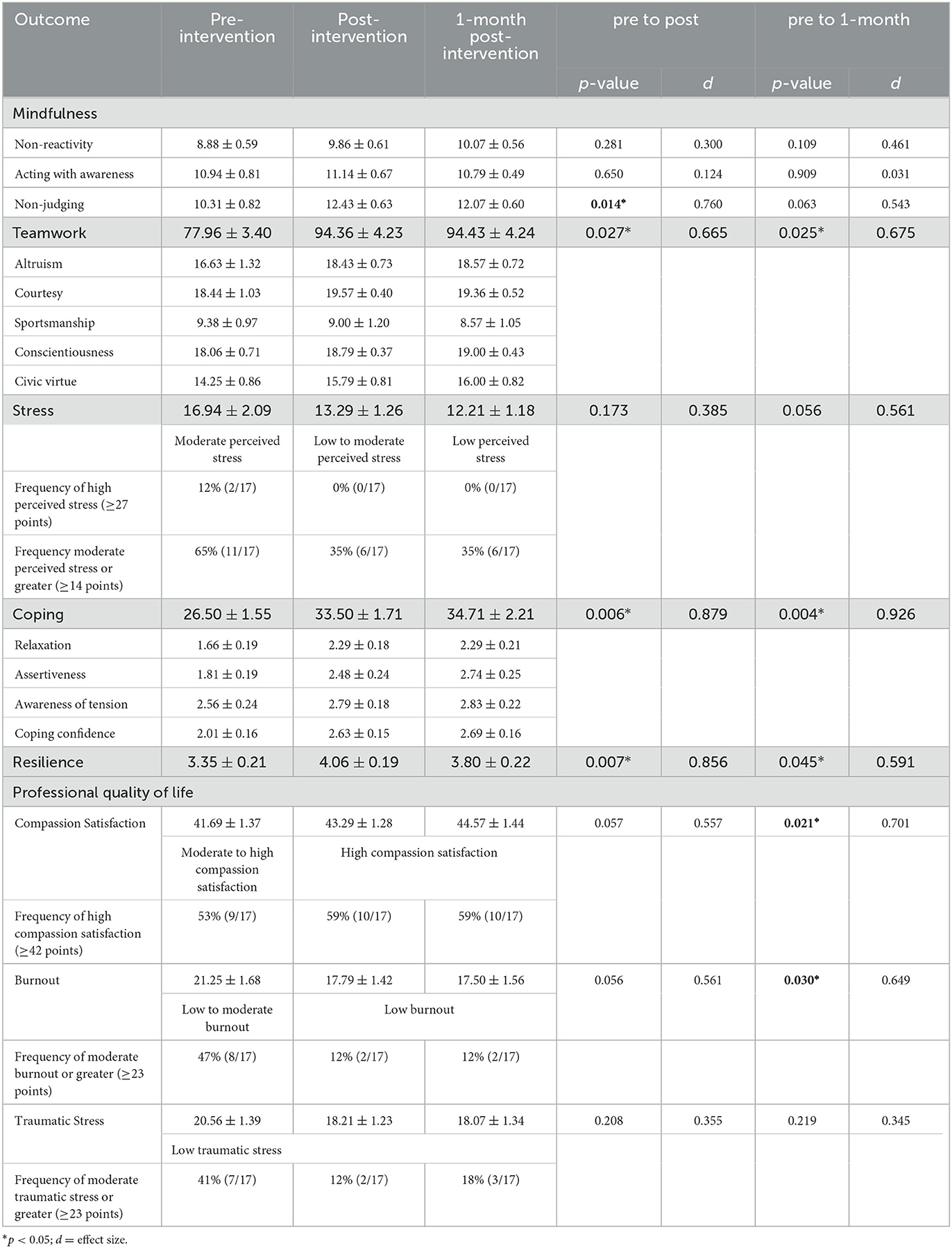

Results: Seventeen medical interpreters (46.2 ± 3.1 years old; 16 women/1 man; 8 White/9 Hispanic or Latino) participated. Overall scores for teamwork (p ≤ 0.027), coping (p ≤ 0.006), and resilience (p ≤ 0.045) increased from pre- to post-intervention and pre- to 1-month post-intervention. Non-judging as a mindfulness component increased from pre- to post-intervention (p = 0.014). Compassion satisfaction (p = 0.021) and burnout (p = 0.030) as components of professional quality of life demonstrated slightly delayed effects, improving from pre- to 1-month post-intervention. Themes such as workshop schedule, group size, group composition, interactivity, topics to be added or removed, and culture are related to the overarching topic areas of intervention logistics and content. Integration of the findings accentuated the positive impact of the intervention.

Discussion: The results of this research demonstrate that mindful practice can serve as an effective resource for medical interpreters when coping with work-related stressors. Future iterations of the mindful practice intervention will further aspire to address linguistic and cultural diversity in the study population for broader representation and subsequent generalization.

Mindfulness and resiliency training in the healthcare workforce has expanded to include many members of the broader care team. Previous literature has investigated the positive effect of mindfulness-based interventions on the health and well-being of medical providers, chaplains, and other allied health professionals (McCracken and Yang, 2008; Irving et al., 2009; Krasner et al., 2009; Geary and Rosenthal, 2011; Beckman et al., 2012; Mehta et al., 2016; Trowbridge and Lawson, 2016; Lomas et al., 2017; Lebares and Hershberger, 2018; Ducar et al., 2020; Grabbe et al., 2021; Epstein et al., 2022); however, few studies have evaluated mindfulness training with medical interpreters (Table 1, note a). Medical interpreters are essential members of the broader care team, serving not only as language interpreters but also as message clarifiers and cultural mediators, all the while navigating the power dynamics between majority and minority cultures (Roat, 1999; Latif et al., 2022). In the absence of an interpreter, language-minority patients were less likely to receive preventive services from their primary care physicians resulting in long-term health implications (McKee et al., 2011). Communication access has been determined a social determinant of health (Smith and Chin, 2012), and thus, providing psychosocial support for the medical interpreter is critical for ensuring equitable access to care (Roman et al., 2022a).

Medical interpreters and the important roles they play in multilingual, cross-cultural communication often go unnoticed. Medical interpreters have reported feeling isolated and devalued (Latif et al., 2022). They have expressed emotional burdens from the complex demands at work (Butow et al., 2012) and are often confronted with various psychosocial stressors (Park et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2022), which have only become more pressing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Roman et al., 2022a,b). The type of clinic (oncology, psychology, and intensive care), type of medical encounter (new diagnosis of serious illness and end of life), emotional content, the interpreter's role (interpreting bad news), and uncertainty (anticipation and lack of preparation) have been identified as contributors to interpreter distress (Lim et al., 2022). In one study, patient- and system-based stressors, role challenges, and interactions with the medical team were the types of daily stressors experienced by medical interpreters (Park et al., 2017). Patient-based stressors were the largest category and incorporated themes, such as patients who are seriously ill or clinically declining, developing attachments and relationships to patients, and identifying with the patient and family members. System-based stressors included lack of resources, lack of time, and scheduling. Role challenges involved bridging communication between the doctor, patient, and family, translating cultures, making cultural adaptations, maintaining professionalism and accuracy, and breaking bad news. Finally, challenging interactions with the medical team consisted of multiple doctors or caregivers talking simultaneously, having responsibility but no control, not feeling part of the team, and abilities not being respected (Park et al., 2017).

Training and certification vary among medical interpreters due to an array of factors. While some medical interpreters are already certified or working toward certification, not all working medical interpreters are certified unless required by the institution. Professional associations serve as certifying entities and have different minimum education requirements (NBCMI, 2021; CCHI, 2022; RID, 2023). Some medical interpreters must have a minimum of a Bachelor's degree (RID, 2023), whereas others require high school-level education or equivalent and completion of a medical interpreter training for a minimum of 40 h (NBCMI, 2021; CCHI, 2022) or a medical interpreter training course of at least three college or university credit hours (NBCMI, 2021). Even though interpreters undergo training to ensure cultural awareness, language fluency, and competency within specialized settings, the extent to which they receive any professional or on-the-job training to cope with work-related distress is unknown. Some studies (Park et al., 2017) suggest training to cope, however, data on the topic is scant, and medical interpreters' exposure to coping resources and training may vary depending on their working language and the context of their interpreting employment. To promote professionalism in sign language (Table 1, note b) interpreter education, programs seeking to become accredited must maintain mental, physical, and emotional self-care and monitoring standards (Standard 6.1, CCIE, 2019). However, not all interpreting programs are accredited and thus not held accountable for upholding such standards.

In a variety of challenging clinical contexts, medical interpreters have identified the need for training, resources, and support across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and organizational levels. Mindfulness was an intrapersonal resource accessible to some medical interpreters for coping with distress (Lim et al., 2022). A resiliency program was previously piloted with medical interpreters in cancer care (Park et al., 2017). The investigators modified the Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (Park et al., 2013; Mehta et al., 2016) into the Coping and Resiliency Enhancement (CARE) program to meet the unique needs of medical spoken language interpreters and showed pre- to post-participation differences in job satisfaction (Park et al., 2017). This past work demonstrated that the delivery of a relaxation and resiliency program could be successfully modified to a different context and was used to guide the adaptation of a mindful practice program with medical interpreters in the current study.

The purpose of this study was to pilot a condensed 8-h mindful practice program to address the contributors to distress and psychosocial stressors faced by medical sign and spoken language interpreters (Park et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2022). We hypothesized that medical interpreters would experience improved mindfulness, teamwork, stress, coping, resilience, and professional quality of life when responding effectively to the demands at work and that these gains would be sustained at a 1-month follow-up. With the results from this study, study investigators aim to direct greater attention to the occupational well-being of medical interpreters because of their essential roles in bridging communication.

This single-arm pilot embedded QUAN(qual) mixed-methods (Schoonenboom and Burke Johnson, 2017) pilot study was approved through the University of Rochester's Research Subject Review Board (STUDY00007212).

Adults aged 18 years or older were eligible if they predominantly worked as an interpreter in a medical setting and lived within driving distance of the University of Rochester Medical Center's campus in Rochester, NY. Interested participants could be community/freelance, staff, student, and/or video remote interpreters. To reflect the current realities of medical interpreting in the United States, interpreting certification was not required. Any minimum number of medical interpreting hours per week or years of medical interpreting experience was also not required. We included interpreters working within or across medical settings (inpatient/acute care, outpatient, surgical, urgent care, home care, and skilled nursing/assisted living). Previous mindfulness experience was neither encouraged nor prohibited. Participants with previous mindfulness experience or an established mindful practice were asked to adhere to the mindful practices described in the intervention during the time they participated in the study.

We openly recruited non-deaf (hearing) and deaf medical sign language interpreters (Table 1, notes c-d), who were bilingual in English and American Sign Language, and medical spoken language interpreters (Table 1, note e), who were bilingual in English and another spoken language, such as Arabic, Mandarin, or Spanish. We distributed study recruitment materials to local interpreting administrators at medical institutions, interpreter referral agencies, video relay service providers (telecommunication between deaf or hard-of-hearing and hearing participants) who also provide coverage of community medical interpreting requests, teachers at local interpreter education programs with an emphasis on medical interpreting, and not-for-profit associations. We requested these entities to offer recruitment support by dispensing materials to interpreters on their teams, students in their classes, and via their organization's social media and newsletters. Recruitment materials were also posted via the social media accounts of study investigators. Interested medical interpreters clicked a link on the study flier and completed a pre-screening survey. Eligible interpreters received an email (with an information sheet attached for review ahead of time) requesting time to schedule a virtual intake appointment when study procedures and expectations were clearly explained. After completion of the intake appointment, if individuals remained interested in taking part in the study, they were emailed a link to the pre-intervention survey (Cohen et al., 1983; Baer et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2008; Krasner et al., 2009; Muzamil Kumar and Ahmad Shah, 2015; Lomas et al., 2017; Park et al., 2017; ProQOL, 2021; Epstein et al., 2022). Participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria received an email explaining their ineligibility.

The research team worked, respectively, with the education committee and continuing education accreditation and certification maintenance programs at the International Medical Interpreters Association/National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters (NBCMI 2016), Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters (CCHI 2023), and Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID, 2023). Collectively, these certifying entities represented the working languages of Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Russian, Korean, Vietnamese, and sign language. The necessary paperwork was submitted for review, and upon subsequent approval, payment was rendered for support with processing continuing education credits to participants as a means of compensation upon the completion of the intervention. Non-certified interpreters received no equivalent compensation. As this was a pilot study to address the contributors to distress and psychosocial stressors faced by medical interpreters, consistent with current recommendations, we did not conduct a power analysis to determine sample size (Leon et al., 2011). Instead, we used a convenience sample to recruit a number of medical interpreters similar to that reported by Park et al. (2017).

Mindful Practice® in Medicine (MPIM) was developed by two physicians at the University of Rochester Medical Center and is an evidence-based educational program designed to build skills and inspire health professionals to thrive, restore joy, and address burnout and distress (Krasner et al., 2009; Epstein et al., 2022; MPIM, 2022). MPIM offers experiential workshops to enhance the self-awareness, emotional intelligence, attentiveness, and compassionate attitudes of health professionals. The goal of MPIM is to advance the quality of interpersonal care in medical settings by improving relationships within healthcare teams and enhancing the resilience and well-being of the healthcare workforce (MPIM, 2022). Past research on MPIM has demonstrated improved and sustained health professional well-being after participation, specifically, reduced burnout and work-related distress, improved empathy, mindfulness, teamwork, job satisfaction, and work engagement, and enhanced personal characteristics for greater delivery of compassionate patient-centered care (Krasner et al., 2009; Epstein et al., 2022).

One of the Co-Directors of MPIM (RE) was an investigator on this study team. Another investigator on the study team (GR) completed MPIM training by participating in the MPIM introductory, core, and facilitator training courses (MPIM, 2022). Cognitive interviews were conducted with the managers and leads of American Sign Language and Spanish patient-care interpreting teams at the University of Rochester Medical Center and insight was shared from collaborators (RH and PV) who have worked with medical interpreters in the Department of Medicine, Palliative Care Program. Interpreting administrators (individuals in positions of administrative leadership) confirmed the potential interest in the topic, shared scheduling preferences and information about interpreter credentials for continuing education credits, offered feedback on proposed incentives, and supported recruitment. Department collaborators helped the research team develop trustworthiness as they had experience disseminating educational information with these teams, and based on such, offered insight into the prominent stressors expressed (i.e., witnessing and supporting patient/family anguish in the face of serious medical information, perceived clinician insensitivity in general or culturally specific clinician insensitivity in communicating that serious medical information, etc.). Based on this input and the relevant literature (Park et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2022), the study team adapted MPIM to address the contributors to distress and stressors faced by medical interpreters. We included challenging interactions with the medical team identified by Park et al. (2017) in the teamwork module (module 3), relevant patient-based stressors in the responding to suffering module (module 4), role challenges in the professionalism module (module 5), and system-based stressors in the uncertainty module (module 6) (Table 2).

The intervention occurred on-site at the University of Rochester Medical Center's campus for 8 weeks with weekly in-person 1-h sessions. Medical sign language interpreters met from July to September 2022 (n = 8) and medical spoken language interpreters met from September to November 2022 (n = 9). Two study investigators (GR and RE) facilitated the delivery of the mindful practice intervention with sign language interpreters and one study investigator (GR) facilitated the delivery with spoken language interpreters.

Each session began with a formal contemplative practice designed to enhance the participants' awareness of their thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations and inform them of their moment-to-moment behavior and actions (Epstein and Krasner, 2017). These practices involved mindful sitting, body scan, mindful movement, or mindful walking (Kabat-Zinn, 2013; Epstein and Krasner, 2017; Table 2). After receiving didactic delivery of the week's theme (Table 2), participants engaged in a relevant mindful inquiry exercise working in pairs or small groups (Figure 1). Mindful inquiry exercises involve the contemplation, writing, sharing, and discussion of professional and personal stories (Epstein and Krasner, 2017). These exercises included the mindful salon, narrative medicine, appreciative interviews, insight dialogue, and an exercise known as RAIN, an acronym for recognize, allow, investigate, and nurture and nourish. Based on The World Café (2008), the mindful salon asked reflective questions, such as “What needs to be cultivated?” and “What needs letting go of?” to explore the educational needs of participants. Narrative medicine (Charon, 2001; Epstein and Krasner, 2017; Columbia University Irving Medical Center, 2022) included reflective writing about the participants' clinical experiences or experiences with colleagues, storytelling, deep listening, and reflective questioning (i.e., “what were you unable to see?”, “what are you assuming that might not be true?”, “can you see the same situation with new eyes?”, or “what moved you most about this situation?”). Based on appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider and Whitney, 2005; Epstein and Krasner, 2017), appreciative interviews were used to focus on the participants' positive potential and successes, rather than problems and challenges. Participants also engaged in insight dialog (Kramer, 2007; Epstein and Krasner, 2017; Insight Dialogue Community, 2022), which involved creating personal and interpersonal space in conversation with a colleague (pause/relax/open), being oneself (attune to emergence), and being present (listening deeply/speaking the truth). For RAIN, participants were asked to recognize the thoughts, feelings, and sensations that were happening inside themselves, allow their thoughts, feelings, and sensations to be just as they are, without trying to change them, investigate their inner experience more deeply with curiosity and kindness, and nurture and nourish with self-compassion, offering themselves kindness, support, and understanding (Brach, 2013, 2022; Epstein and Krasner, 2017; Table 2). After each session, participants were instructed in an informal contemplative practice (Epstein and Krasner, 2017; Chozen Bays, 2022) or a brief feasible practice to be implemented when at work and on their own time in between modules. Grounding and loving-kindness were a couple examples of the informal practices shared (Table 2).

Outcomes were collected across three time points (pre-, post-, and 1-month post-intervention) using a collective survey instrument (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). The post-intervention data collection occurred immediately upon the completion of the workshop series and the 1-month post-intervention occurred 1-month after completion of the workshop series regardless of whether the participant completed all of the sessions. Our survey included the following measures: Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ-15) (Baer et al., 2006; Krasner et al., 2009; Epstein et al., 2022), Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale (Muzamil Kumar and Ahmad Shah, 2015; Epstein et al., 2022) for teamwork, Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983; Lomas et al., 2017), Part A of the Measure of Current Status (MOCS-A) (Park et al., 2017) for coping, Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) (Smith et al., 2008), and Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) (Lomas et al., 2017; ProQOL, 2021) (Table 3).

In addition to the quantitative outcome measures, one free text item was included in the post-intervention survey. Participants were asked to voluntarily offer any suggestions about how the intervention could be improved. Also, at the time of the post-intervention survey, participants were offered the opportunity to participate in a voluntary exit interview with a study investigator to elaborate upon any feedback they wanted to share from their time in the workshop series. Each exit interview was performed remotely for 15–50 min and recorded using video conferencing software (Zoom, San Jose, CA). The guide for these individual interviews included questions about intervention logistics, such as “What worked and did not work regarding the workshop series schedule?” and “How did you find the group size?” Questions about intervention content were also included, such as “How did you find the interactivity within each of the sessions (i.e., the formal and informal mindful practices, large group, small group, and paired discussions, as well as the mindful inquiry exercises)?” and “How was the complexity of the content? Do any topics need to be added or removed from the curriculum as it was presented?”

Quantitative data were compiled and qualitative data were manually transcribed. With significance at p < 0.05, all quantitative statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v.29, IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics for participant demographics and quantitative outcome variables were calculated (mean ± SEM). Perceived stress and professional quality of life were compared with available normative values (Cohen and Williamson, 1988; ProQOL, 2021). Paired samples t-tests and effect size measurements using Cohen's d were separately performed to analyze the mindfulness sub-scales, overall teamwork, stress, overall coping, resilience, and professional quality of life sub-scales from pre- to post-intervention and from pre- to 1-month post-intervention for the combined cohort of medical interpreters. While descriptive statistics were reported for the teamwork and coping sub-scales, we elected against analyzing for within-subject differences across time points because of concerns relating to type I errors with multiple comparisons.

A thematic framework matrix was established by way of qualitative description (MaxQDA, Berlin, Germany) for qualitative data analysis (Sandelowski, 2000; Gale et al., 2013; Spencer et al., 2013). Qualitative description used everyday terms and provided a summary of the participant's experience in the workshop series (Sandelowski, 2000). One study investigator (GR) initially coded the data, using a paraphrase or label that described what was interpreted as important in the feedback. Thereafter, two study investigators (GR and RY-N) discussed and debated the initial coding structure and triangulated the identified topic areas of improvement or suggestions for the overall study, intervention logistics, and intervention content into themes and sub-themes. We elected not to create operational definitions after the initial coding, nor did we employ respondent validation because of the straightforward nature of qualitative description. Finally, the same study investigators (GR and RY-N) worked together to integrate the quantitative and qualitative data to emphasize any concordant or discordant findings (Creamer, 2018).

Seventeen medical interpreters (46.2 ± 3.1 years old; 16 women/1 man; 8 White/9 Hispanic or Latino) participated. Eight participants were hearing medical sign language interpreters, and nine were medical Spanish interpreters. No deaf medical sign language interpreters participated. Participants had 8.2 ± 2.0 years of medical interpreting experience and worked 26.1 ± 2.9 h/week of medical interpreting. Eleven participants were certified interpreters, and eight reported previous experience with mindfulness. Three withdrew before the start of the intervention citing family reasons unrelated to the study. Interpreters represented two different health systems and worked across congregate living, hospital, outpatient, surgical, urgent care, home care, telehealth, and mobile crisis settings. Four interpreters reported working in two of these settings, six interpreters worked in three settings, four interpreters reported working in four of these settings, one interpreter worked across five settings, one interpreter worked in six settings, and one interpreter reported working across seven settings. Six interpreters worked full-time, two worked part-time, and eight worked per diem or time as reported. One interpreter identified working as a freelance interpreter or independent contractor. Attendance ranged from one to eight sessions (5.3 ± 0.7 sessions). Nine interpreters were able to attend six or more sessions (four interpreters attended all eight sessions, one interpreter attended seven sessions, and four attended six sessions), four interpreters were able to attend between two and five sessions (two attended five sessions, one attended four sessions, and one attended two sessions), and one interpreter only attended one session.

The survey response rate was 94% (16 out of 17), 82% (14 out of 17), and 82% (14 out of 17) at pre-, post-, and 1-month post-intervention, respectively. Out of 15 possible points for each mindfulness sub-scale, there were no significant within-subject differences (Table 4) across time points for non-reactivity [pre to post: t(13) =-1.124, p = 0.281, d = 0.300; pre to 1-month: t(13) = −1.723, p = 0.109, d = 0.461] and acting with awareness [pre to post: t(13) = −0.465, p = 0.650, d = 0.124; pre to 1-month: t(13) = 0.116, p = 0.909, d = 0.031]. Within-subject differences significantly improved from pre- to post-intervention for non-judging [t(13) = −2.844, p = 0.014, d = 0.760]; however, such differences were not maintained from pre- to 1-month post-intervention [t(13) = −2.030, p = 0.063, d = 0.543]. Out of 105 possible points for overall teamwork, within-subject differences significantly increased from pre- to post-intervention [t(13) = −2.488, p = 0.027, d = 0.665] and from pre- to 1-month post-intervention [t(13) = −2.526, p = 0.025, d = 0.675]. Ranging from 0 to 40 possible points, within-subject scores for stress across time points did not significantly decrease from pre- to post-intervention [t(13) = 1.441, p = 0.173, d = 0.385]; however, stress demonstrated a moderate effect size (Cohen, 1988; Sawilowsky, 2009) and changed from moderate to low perceived stress (Cohen and Williamson, 1988) when comparing pre- to 1-month follow-up [t(13) = 2.097, p = 0.056, d = 0.561]. Table 4 conveys the stress values compared with the available norms from the general population (Cohen and Williamson, 1988), as well as the frequencies of participants with high perceived stress and moderate perceived stress or greater. Out of the 52 possible points for overall coping, within-subject increases from pre- to post-intervention [t(13) = −3.290, p = 0.006, d = 0.879) and from pre- to 1-month post-intervention [t(13) = −3.464, p = 0.004, d = 0.926] were significant and revealed a strong effect of the mindful practice. The average scores on a 5-point Likert scale across the six items on the BRS significantly improved from pre- to post-intervention [t(13) = −3.202, p = 0.007, d = 0.856] and from pre- to 1-month post-intervention [t(13) = −2.212, p = 0.045, d = 0.591]. Ranging from 10 to 50 possible points on each professional quality of life sub-scale, differences within subjects for compassion satisfaction demonstrated a moderate effect size and changed from moderate to high compassion satisfaction (ProQOL, 2021) when comparing pre- to post-intervention [t(13) = −2.085, p = 0.057, d = 0.557] and significantly increased from pre- to 1-month post-intervention [t(13) = −2.624, p = 0.021, d = 0.701]. Burnout scores also demonstrated a moderate effect of the mindful practice and changed from low to moderate to low burnout (ProQOL, 2021) when comparing pre- to post-intervention (t(13) = 2.097, p = 0.056, d = 0.561) and significantly decreased from pre- to 1-month post-intervention (t(13) = 2.427, p = 0.030, d = 0.649). Scores for traumatic stress showed no differences within subjects across time points [pre to post: t(13) = 1.326, p = 0.208, d = 0.355; pre to 1-month: t(13) = 1.291, p = 0.219, d = 0.345]. Table 4 conveys the ProQOL values compared with available norms (ProQOL, 2021), the frequency of participants reporting high compassion satisfaction, and the frequencies of participants with moderate burnout or greater and moderate traumatic stress or greater.

Table 4. Mean (±SEM) scores and unadjusted differences within subjects across time points for mindfulness, teamwork, stress, coping, resilience, and professional quality of life.

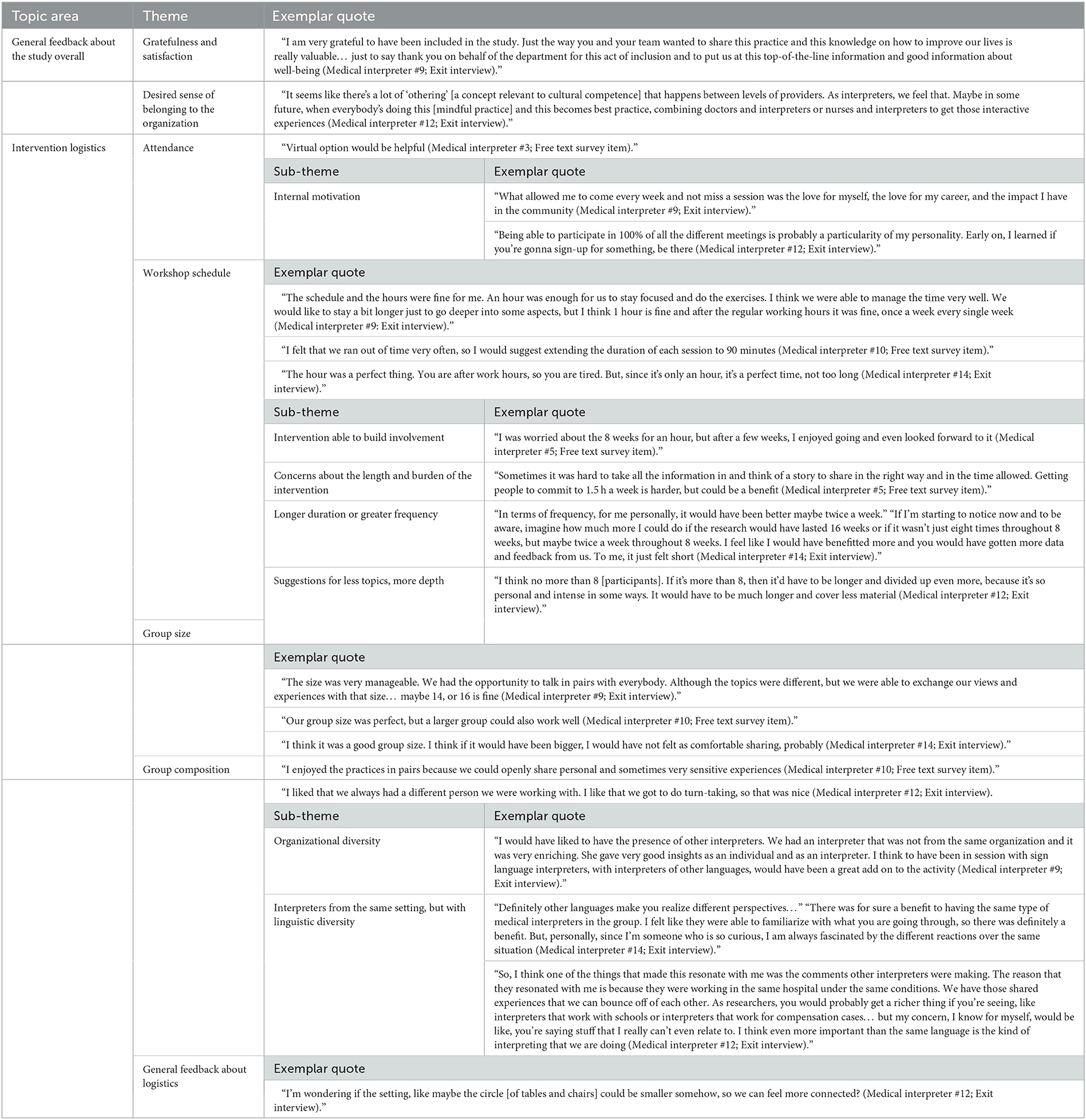

Six out of 17 participants (35%) provided a qualitative response to the free text item on the post-intervention survey, and three out of 17 participants (18%) participated in an individual exit interview. Themes such as workshop schedule, group size, group composition, interactivity, topics to be added or removed, and culture are related to the overarching topic areas of intervention logistics (Table 5) and intervention content (Table 6). The majority of respondents desired either extending the duration of the session, frequency of the sessions, and/or duration of the overall intervention. Some respondents would not have felt as comfortable sharing in a larger group, whereas others thought a larger group would work well with the understanding that it would require more time and have to cover less material or the material would have to be divided up across more sessions. Respondents valued being with other medical interpreters during the workshop series rather than with interpreters working in non-medical settings and welcomed the differing perspectives of interpreters from other medical organizations and who interpret across different languages. While respondents liked the consistent structure of delivery from session to session, they also liked the different practices with opportunities to work in pairs and take turns in the storyteller and listener roles. Regarding topics to be added or removed, one respondent requested more depth about professionalism or professional processing of the exposures at work; specifically, more formalized peer debriefing after an assignment. “We come back from one session and it's just like doing catharsis. I think on a deeper level as professionals, not as human beings complaining (laughing), would be helpful (Medical interpreter #9; Exit interview).” The same respondent felt that mindful practice was very inclusive and the intervention allowed them to get in touch with their culture. Another respondent shared that culturally, it felt rushed. “Hispanics, we like to talk and think out loud. Once we get going, we generally don't say anything unless we're gonna say something, and then we kind of wanna be heard (laughter) (Medical interpreter #12; Exit interview).” Regarding cultural adaptation of the intervention, more time was suggested to allow participants to process the information and experience. Respondents addressed issues of race, ethnicity, and language of the facilitator. Respondents felt it was important that the facilitator was an interpreter but did not require the facilitator to serve as an interpreter for the same language (a sign language interpreter leading the cohort of sign language interpreters or a Spanish interpreter leading the cohort of Spanish interpreters). Respondents generously shared the personal impact of the intervention (Table 6) and humanized the significant quantitative findings (Table 4) for non-judging (mindfulness), teamwork, coping, resilience, compassion satisfaction, and burnout (professional quality of life). “…this information is freedom. This information is empowerment. And that's what we need to do… every single thing in our lives. We, most of the time, are doubtful or hesitant… and this is just saying, yes you are, and yes you can and this is the way and you are going to have support and that is what this ancient teaching is giving us. I really liked it (Medical interpreter #9; Exit interview).” Another respondent stated, “I did notice, not a change, but an impact. A positive impact of recognizing, of noticing, mostly noticing certain moments… I'm noticing myself, noticing how I'm feeling, noticing the feelings arising, noticing the emotions or the feelings in my body. For me that was huge, I'm like, ‘oh my God, I'm noticing. I'm recognizing, I'm thinking about it.' Before, I wasn't doing that. None of it (Medical interpreter #14; Exit interview).”

Table 5. Qualitative feedback from study participants about the study overall and intervention logistics.

By incorporating the insight of interpreting administrators and collaborators who have worked with medical interpreters, as well as the contributors to interpreter distress and psychosocial stressors from the relevant literature (Park et al., 2017; Lim et al., 2022), we adapted and piloted an MPIM program with medical interpreters using a single-arm pilot embedded QUAN(qual) mixed-methods study design (Schoonenboom and Burke Johnson, 2017). We hypothesized that effects would occur at the post-intervention time point and be maintained at 1-month follow-up; thus, significant differences were anticipated from pre- to post-intervention and from pre- to 1-month post-intervention. In support of our hypothesis, the overall scores for teamwork, coping, and resilience all increased from pre- to post-intervention and pre- to 1-month. As components of professional quality of life, compassion satisfaction and burnout were in partial support of our hypothesis demonstrating significant delayed effects of the intervention. Compassion satisfaction increased and burnout decreased from pre- to 1-month post-intervention; however, each had moderate effect sizes and improved when compared with available normative values (ProQOL, 2021) but were not statistically significant from pre- to post-intervention. Also, in partial support of our hypothesis, non-judging as a mindfulness component increased from pre- to post-intervention, however, was not sustained 1-month later. Stress demonstrated delayed moderate effects of the mindful practice from pre- to 1-month with a change from moderate to low perceived stress, and marginal statistical significance, however, was not significant from pre- to post-intervention. The intervention was unable to impact change in the mindfulness components of non-reactivity and acting with awareness and in the professional quality of life component of traumatic stress. Qualitative data revealed that those who attended every session had a strong internal motivation and that participation in the intervention helped to build involvement for those who may have been initially hesitant. Even though feelings were mixed about similar or larger group size, participants welcomed different perspectives from interpreters at different organizations and across different languages but wanted to limit the sessions to interpreters who practice within the same setting. As such, any future iterations should combine cohorts of medical interpreters. The impact of the intervention had positive effects, guiding participants to notice their thoughts, feelings, emotions, and physical sensations and be more responsive vs. reactive. Addressing fewer topics with more depth or the same number of topics but across multiple sessions or by extending the session duration was suggested; specifically, more depth about professionalism was requested. The role of the mindful practice facilitator with medical interpreters should be maintained by an interpreter with no specific requirement of race, ethnicity, or language, just cultural humility and openness. Finally, the integration of our quantitative and qualitative findings accentuated the positive impact of the mindful practice intervention.

Although there were differences in sampling demographics and methodology, our work adds to the previous work (Park et al., 2017) by demonstrating that an adapted mindful practice intervention was able to impact positive change in medical interpreter well-being. Group composition across the current and past study cohorts (Park et al., 2017) was similar with 53% and 54% identifying as Hispanic or Latino, respectively; however, Park et al. (2017) did not include medical sign language interpreters and had a greater diversity of medical spoken language interpreters. Park et al. (2017) delivered the CARE program for medical interpreters in one 4-h block, whereas the current study delivered a condensed MPIM program for 8 weeks with weekly in-person 1-h sessions. Stress, coping, and satisfaction were comparable outcome variables of interest across studies. Stress and coping were measured using the same tools; however, satisfaction was measured using different tools. We found a moderate effect of the intervention on stress was delayed and marginal statistical significance inviting confirmation with a larger study. This contrasted with Park et al. (2017) who found no differences in stress across time points (p = 0.360, d = 0.170). The mindful practice intervention was able to impact a significant increase in overall coping, whereas the relaxation response and resiliency program (Park et al., 2017) reported no overall change (p=0.130, d=0.330). We measured compassion satisfaction, which was defined as the pleasure derived from being able to work well (ProQOL, 2021) using the ProQOL, and Park et al. (2017) used modified items from the 2006 Massachusetts General Hospital staff survey to measure job satisfaction. Compassion satisfaction in the current study and job satisfaction in the past work (Park et al., 2017) both demonstrated significant improvement.

Future mindful practice intervention development and adaptation could borrow from some of the tactics used in the CARE program (Park et al., 2017). Participants in this study requested presentation handouts, in addition to electronic delivery of the presentation slides, to enhance their learning and reference later on as a reminder of what was learned. Participants also wished there were more efforts to foster accountability in between sessions. Even though each week concluded with an introduction of new practices or review of previous informal mindful practices that could be implemented between sessions, participants felt it was too easy to forget and were eager for more engagement, like a journal or a discussion board, and more group debriefing about their independent mindful practice efforts. As resources permit, a manual to write in during the sessions, inclusive of the didactic content and interactive exercises, as well as recordings to guide daily practice in between sessions for enhanced sustainment after completion of the intervention could be provided.

This study had a few limitations. Although we had interpreters from other medical organizations and combined medical sign and spoken language interpreter cohorts in our analyses, readers are cautioned about deriving generalizations using these limited data as the study may be underpowered. Additionally, because of the low response to the free text survey item and low participation in exit interviews, we recognize the limited degree to which the qualitative results represent the scope of reactions to the intervention. Because of the pilot nature of this study and our aim to detect trends, we elected not to control for type I errors across the multiple comparisons; thus, some false positives may exist. Investigators strongly encouraged medical interpreters to participate across the entire duration of the study; however, we did not exclude or withdraw those who missed any specific number of sessions. Data analyses did not compare across the number of sessions attended or compare across languages, years of medical interpreting, certification, or previous mindfulness experience because of our small sample. Past iterations of MPIM with physicians and medical educators have been conducted in Western New York, Norway, and the Netherlands with participants from Africa, Asia, Australia/Oceania, Europe, and North and South America (Epstein et al., 2022). With greater societal awareness, diversity, equity, and inclusion themes are increasingly incorporated into the MPIM content and cultural, racial, linguistic, and occupational diversity are increasingly being represented by the MPIM teaching faculty, facilitators, and learners. Future iterations of the mindful practice intervention with medical interpreters should further aspire to address linguistic and cultural diversity in the study population for broader representation and subsequent generalization. Formal contemplative practices of mindfulness are often inaccessible to deaf medical sign language interpreters or deaf patient communities because they encourage participants to soften or lower their gaze or close their eyes. This limits participation as deaf persons rely more on visual communication than their non-deaf (hearing) peers. To avoid the exclusion of minoritized groups, past studies have emphasized, that research participants and facilitators for mindfulness-based programs should be representative and have shown meaningful cultural adaptations in language, content, and methods (Castellanos et al., 2020; Eichel et al., 2021). The next steps in this research agenda will involve community collaborations to develop, disseminate, and assess accessible mindfulness resources (i.e., video recordings in sign language) as currently there are limited mindfulness opportunities available for deaf sign language users.

An array of training, resources, and support across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and organizational levels (Lim et al., 2022) are necessary for promoting the management of psychosocial stressors experienced by medical interpreters. Because communication access is a social determinant of health, protecting and promoting the health of medical interpreters are critical for ensuring equitable healthcare access for language-minority patients. Mindful practice could serve as an effective resource for medical interpreters when coping with work-related stressors. The most important findings from this study were improved and sustained teamwork, coping, and resilience, which replicated the improved and sustained well-being outcomes of the MPIM program with health professionals (Krasner et al., 2009; Epstein et al., 2022). All qualitative feedback gathered from study participants about intervention logistics and content will be incorporated into future iterations for improved intervention efficacy. After the completion of initial mindful practice training, any ongoing sessions should include members across disciplines, such as physicians and nurses to promote interpreters' desired sense of belonging to the organization. Efforts from this research demonstrate the need for greater visibility and attention to medical interpreters as essential members of the broader care team.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Rochester, Research Subjects Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because this study posed no greater than minimal risk. An information sheet was used instead when enrolling participants. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because this study posed no greater than minimal risk.

GR, RY-N, PV, AC, SB, and RE: conceptualization, visualization, and writing—review and editing. GR: data curation, project administration, and writing—original draft. GR and RY-N: formal analysis. GR, RY-N, AC, SB, and RE: methodology. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The project described in this publication was supported by start-up funding (AC and GR) from the University of Rochester.

The authors thank the medical interpreters who participated in this study, as well as the managers and leads of American Sign Language and Spanish patient-care interpreting teams and the manager of the Deaf Professional interpreting team for their time, support, and commitment to overall improved well-being through mindful practice. The authors are grateful to Robert Horowitz, MD, a colleague who works with medical interpreters in the Department of Medicine, Palliative Care Program, for his assistance during the early planning phases of the study with recruitment and intervention adaptation. The authors also thank Aurora Rodriguez, CMI Spanish, Brianna Conrad, NIC, and Keven Poore, CDI for taking the time to offer feedback on the glossary of terms in Table 1 and Joann Leslie for her administrative support.

RE is a Co-Director of MPIM.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., and Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 13, 27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504

Beckman, H. B., Wendland, M., Mooney, C., Krsner, M. S., Quill, T. E., Suchmann, A. L., et al. (2012). The impact of a program in mindful communication on primary care physicians. Academic Medicine. 87:815–819. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253d3b2

Brach, T. (2013). True Refuge: Finding Peace and Freedom in Your Own Awakened Heart. New York, NY: Bantam.

Brach, T. (2022). Meditation, Emotional Healing, and Spiritual Awakening. Available online at: https://www.tarabrach.com/ (accessed on January 15, 2023).

Butow, P. N., Lobb, E., Jefford, M., Goldstein, D., Eisenbruch, M., Girgis, A., et al. (2012). A bridge between cultures: interpreters' perspectives of consultations with migrant oncology patients. Care Cancer. 20, 235–244. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1046-z

Castellanos, R., Yildiz Spinel, M., Phan, V., Aguayo, R. O., Humphreys, K., and Flory, K. (2020). A systematic review and mete-analysis of cultural adaptations of mindfulness-based interventions for Hispanic populations. Mindfulness 11, 317–322. doi: 10.1007/s12671-019-01210-x

CCHI (2022). Candidate's Examination Handbook. Available online at: https://cchicertification.org/uploads/CCHI_Candidate_Examination_Handbook.pdf (accessed January 15, 2023).

CCIE (2019). Commission on Collegiate Interpreter Education Accreditation Standards. Available online at: http://www.ccie-accreditation.org/standards.html (accessed January 15, 2023).

Charon, R. (2001). Narrative medicine. A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 286, 1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

Chozen Bays, J. (2022). Mindful Medicine: 40 Simple Practices to Help Healthcare Professionals Heal Burnout and Reconnect to Purpose. Boulder, CO: Shambjala.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., and Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24:385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

Cohen, S., and Williamson, G. (1988). “Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States,” in The Social Psychology of Health, ed. Spacapan S, Oskamp S (SAGE), 31–68.

Columbia University Irving Medical Center (2022). Department of Medical Humanities and Ethics. Division of Narrative Medicine. Available online at: https://www.mhe.cuimc.columbia.edu/division-narrative-medicine (accessed January 1, 2023).

Cooperrider, D., and Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative Inquiry. A Positive Revolution in Change. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Creamer, E. G. (2018). An Introduction to Fully Integrated Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, C. A.: SAGE.

Ducar, D. M., Penberthy, J. K., Schorling, J. B., Leavell, V. A., and Calland, J. F. (2020). Mindfulness for healthcare providers fosters professional quality of life and mindful attention among emergency medical technicians. Explore 16, 61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2019.07.015

Eichel, K., Gawande, R., Acabchuk, R. L., Palitsky, R., Chau, S., Pham, A., et al. (2021). A retrospective systematic review of diversity variables in mindfulness research, 2000–2016. Mindfulness 12, 2573–2592. doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01715-4

Epstein, R., and Krasner, M. (2017). Mindful Practice® Workshop Facilitator Manual. 3rd Ed. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Medical Center.

Epstein, R. M., Marshall, F., Sanders, M., and Krasner, M. S. (2022). Effect of an intensive mindful practice workshop on patient-centered compassionate care, clinician well-being, work engagement, and teamwork. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 42, 19–27. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000379

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., and Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Geary, C., and Rosenthal, S. L. (2011). Sustained impact of MBSR on stress, well-being, and daily spiritual experiences for 1 year in academic health care employees. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 17, 939–944. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0335

Grabbe, L., Higgins, M. K., Baird, M., and Pfeiffer, K. M. (2021). Impact of a resiliency training to support the mental well-being of front-line workers. Med. Care. 59, 616–621. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001535

Insight Dialogue Community (2022). Living Relational Dhamma. Available online at: https://insightdialogue.org/ (accessed January 15, 2023).

Irving, J. A., Dobkin, P. L., and Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: a review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 15, 61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.01.002

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full Catastrophe Living (Revised Edition): Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Kramer, G. (2007). Insight Dialogue: The Interpersonal Path to Freedom. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications.

Krasner, M. S., Epstein, R. M., Beckman, H., Suchman, A. L., Chapman, B., Mooney, C. J., et al. (2009). Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA 302, 1284–1293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384

Latif, Z., Makuvire, T., Feder, S. L., Crocker, J., Pinzon, P. Q., and Warraich, H. J. (2022). Forgotten in the crowd: a qualitative study of medical interpreters' role in medical teams. J. Hosp. Med. 7, 719–725. doi: 10.1002/jhm.12925

Lebares, C. C., Hershberger, A. O, Guvva, E. V., Desai, A, Mitchell, J, Shen, W, et al. (2018). Feasibility of formal mindfulness-based stress-resilience training among surgery interns. JAMA Surg. 153, e182734. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2734

Leon, A. C., Davis, L. L., and Kraemer, H. C. (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J. Psychiatr. Res. 45, 626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008

Lim, P. S., Olen, A., Carballido, J. K., LiaBrateen, B., Sinnen, S. R., Balistrein, K. A., et al. (2022). “We need a little help”: a qualitative study on distress and coping among pediatric medical interpreters. J. Hosp. Manage. Health Policy. 6, 36. doi: 10.21037/jhmhp-22-23

Lomas, T., Medina, J. C., Ivtzan, I., Rupprecht, S., and Eiroa-Orsa, F. (2017). A systematic review of the impact of mindfulness on the well-being of healthcare professionals. J. Clin. Psychol. 74:319–355. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22515

McCracken, L. M., and Yang, S. (2008). A contextual cognitive-behavioral analysis of rehabilitation workers' health and well-being: influences of acceptance, mindfulness, and values-based action. Rehabil. Psychol. 53, 479–485. doi: 10.1037/a0012854

McKee, M. M., Barnett, S. L., Block, R. C., and Pearson, T. A. (2011). Impact of communication on preventive services among deaf American sign language users. Am. J. Prev. Med. 41, 75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.004

Mehta, D. H., Perez, G. K., Traeger, L., Park, E. R., Goldman, R. E., Haime, V., et al. (2016). Building resiliency in a palliative care team: a pilot study. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 51, 604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.013

MPIM (2022). Helping Clinicians Thrive. Available online at: https://mindfulpracticeinmedicine.com/ (accessed January 15, 2023).

Muzamil Kumar, M., and Ahmad Shah, S. (2015). Psychometric properties of Podsakoff's organizational citizenship scale in the Asian context. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 3, 51–60. doi: 10.25215/0301.152

NAD Website (2023). What is America Sign Language? Available online at: https://www.nad.org/resources/american-sign-language/what-is-american-sign-language/#:~:text=American%20Sign%20Language%20(ASL)%20is,important%20parts%20in%20conveying%20information (accessed on February 10, 2023).

NBCMI (2021). “Certified medical interpreter,” in NBCMI Candidate Handbook. Available online at: https://www.certifiedmedicalinterpreters.org/assets/docs/NBCMI_Handbook.pdf?v=20211117 (accessed January 15, 2023).

NCIEC (2023). Deaf Interpreter Institute. What is a Deaf interpreter? Available online at: http://diinstitute.org/what-is-the-deaf-interpreter/ (accessed on February 2, 2023).

Park, E. R., Mutchler, J. E., Perez, G., Goldman, R. E., Niles, H., Haime, V., et al. (2017). Coping and resiliency enhancement program (CARE): A pilot study for interpreters in cancer care. Psychooncology 26, 1181–1190. doi: 10.1002/pon.4137

Park, E. R., Traeger, L., Vranceanu, A. M., Scult, M., Lerner, J. A., Benson, H., et al. (2013). The development of a patient-centered program based on the relaxation response: the relaxation response resiliency program (3RP). Psychosomatics 54, 165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.09.001

Pfau, R., Steinbach, M., and Woll, B. (2012). Sign Language An International Handbook. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton.

ProQOL (2021). ProQOL Measure. Available online at: https://proqol.org/proqol-measure (accessed January 15, 2023).

RID (2023). Available Certifications. Available online at: https://rid.org/certification/available-certifications/ (accessed January 15, 2023).

Roat, C. (1999). “Bridging the gap: a basic training for medical interpreters,” in Cross Cultural Health Care Program (CCHP) Seattle, WA. Available online at: https://xculture.org/bridging-the-gap/ (accessed February 10, 2023).

Roman, G., Samar, V., Ossip, D., McKee, M., Barnett, S., and Yousefi-Nooraie, R. (2022a). The occupational health and safety of sign language interpreters working remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Chronic Dis. 19, 210462. doi: 10.5888/pcd19.210462

Roman, G., Samar, V., Ossip, D., McKee, M., Barnett, S., and Yousefi-Nooraie, R. (2022b). Perspectives of sign language interpreters and interpreting administrators during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative description. Public Health Rep. 138, 691–704. doi: 10.1177/00333549231173941

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health. 23, 334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g

Sawilowsky, S. S. (2009). New effect size rules of thumb. J. Moder. Appl. Stat. Methods. 8, 597–599. doi: 10.22237/jmasm/1257035100

Schoonenboom, J., and Burke Johnson, R. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. Kolner Z. Soz. Sozpsychol. 69, 107–131. doi: 10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., and Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 15(3):194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972

Smith, S. R., and Chin, N. P. (2012). “Social determinants of health in deaf communities,” in Public health – Social and Behavioral Health, ed. J. Maddock (Rijeka, Croatia: InTech), 449–460.

Spencer, L., Richie, J., Ormston, R., et al. (2013). “Analysis: principles and processes,” in Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 2nd ed, eds. J. Ritchie, J. Lewis, C. McNaughton Nicholls, and R. Ormston. (London: SAGE Publications, Ltd), 269–294.

The World Café (2008). Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter. The World Café Presents… A Quick Reference Guide for Putting Conversations to Work. Available online at: https://theworldcafe.com/ (accessed January 15, 2023).

Keywords: coping, medical interpreters, mindfulness, mindful practice, professional quality of life, resilience, stress, teamwork

Citation: Roman G, Yousefi-Nooraie R, Vermilion P, Cupertino AP, Barnett S and Epstein R (2023) Mindful practice with medical interpreters. Front. Psychol. 14:1171993. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1171993

Received: 22 February 2023; Accepted: 28 September 2023;

Published: 26 October 2023.

Edited by:

Petra Hanson, University of Warwick, United KingdomReviewed by:

Amy Olen, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Roman, Yousefi-Nooraie, Vermilion, Cupertino, Barnett and Epstein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gretchen Roman, R3JldGNoZW5fUm9tYW5AdXJtYy5yb2NoZXN0ZXIuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.