1. Introduction

The loss of a close family member is usually assumed to be one of the most stressful experiences. In their classical work, indeed, Holmes and Rahe (1967) classified the death of a spouse as the most stressful event, while the death of a close family member ranked fifth. Throughout the years, empirical research has examined the health outcomes of bereavement. One of the research's significant findings is that bereavement increases the risk of mortality, as well as the use of medical services (Stroebe et al., 2007). By way of understanding this finding, several risks and protective factors consisting of intrapersonal and interpersonal variables have been taken into account. For example, considering psychological resilience allow us to explain why some individuals develop a dysfunctional reaction, while other do not (Mancini and Bonanno, 2009). Although grief reactions are diverse, what is noteworthy here regards those leading to psychological symptoms. Depression and anxiety are commonly considered two of the most frequent symptoms among the bereaved, causing significant impairment in quality of life (Boelen and Prigerson, 2007). Among the diverse grief reactions, however, a pooled prevalence of 9.8% of the bereaved develop a syndrome named Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) (Lundorff et al., 2017), even though this finding was grounded on a variety of definitions. More recently, the prevalence rate 1 year after loss using the latest diagnostic DSM criteria for PGD was 4.4–10.9% (Prigerson et al., 2021). Another recent study found a prevalence rate of 3.3% when considering the DSM-5-TR criteria (Rosner et al., 2021). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) included PGD in Section 2, under the chapter named “trauma- and stressor-related disorders” (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). The diagnostic criteria for PGD are the death of a loved one for at least 12 months and the onset of a chronic grief reaction characterized by deep yearning or longing for the lost person accompanied by preoccupation with thoughts or memories. Other symptoms characterizing PGD are identity disruption, intense emotional pain, and emotional numbness related to the loss. Since the high healthcare costs for individuals who develop a PGD, a preventive approach is paramount. This implies a deep understanding of protective and risk factors that might decrease or increase the likelihood of the onset of the disorder. Indeed, a glimpse into the factors underlying the risk of maladaptive reactions to grief is crucial. Of particular interest for empirical research and clinical practice is the field of palliative care. After the loss of their loved one, family members may experience intense grief reactions and, consequently, bereavement support represents a core component of palliative care. As argued by Lichtenthal (2018), improving screening and assessment of individuals at high risk of Prolonged Grief Disorder is challenging, along with implementing empirically supported interventions. However, it is hard to dispute that considering severe grief reactions as a mental disorder triggers some critical points. Research over the years has shown not only that a small but considerable percentage of individuals develop PGD after the death of a loved one, but that they may be at risk of stigmatization (Johnson et al., 2009; Gonschor et al., 2020). Thus, meeting the needs of bereaved individuals presents a substantial challenge to specialists within the field. Stigmatization toward individuals with PGD can have a detrimental impact on prevention as well as on seeking professional help (Schomerus and Angermeyer, 2008).

2. Bereavement and palliative care

In Italy, recent estimates reported more than 180.000 deaths for cancer (Italian Association of Medical Oncology, 2021), while almost 40.000 received palliative home care (Italian Ministry of Health, 2018). Family caregivers of patients in palliative care are more at risk of complicated grief (Guldin et al., 2011). World Health Organization. (2004) defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness”. Relief from pain and other symptoms affecting a patient's quality of life represents the main aim of palliative care. Another aim concerns support for their family members after the loss, even though scant attention has been directed toward the prevention of complicated grief. By this token, it is not by chance that bereavement support has been designated as “the forgotten child” of palliative care (Hudson et al., 2018). Poor resources for individuals who need psychological support seem to characterize the public health approach to bereavement care (Aoun et al., 2012). Not all palliative services have a bereavement support program, even though prevention of complicated grief should represent the main target for them (World Health Organization., 2004). While on one hand, bereavement support remains under-researched, on the other hand, professionals still refer to past theories lacking empirical evidence (Bonanno, 2009). At best, some of these past theories have conceived grief as a sequence of phases that must be going through identically to yield the most efficacy results. Nevertheless, the needs of informal caregivers of patients in palliative care are more complex than expected by a model of the stages of grief, especially when they struggle with the loss. In this vein, it could be useful to consider trajectories of grief over time. For instance, in a study involving a sample of 28 recent widows, Bisconti et al. (2006) found that the pattern of emotional wellbeing widely oscillated across 3 months. Put another way, confusion about one's emotional state may characterize the period immediately following the loss. Factors such as social support may influence the overall intraindividual trend. Another caveat regards antecedent predictors of trajectories of grief. Bonanno et al. (2002) conducted a prospective study from preloss to 18 months postloss among a sample of 205 individuals belonging to the general population. Unlike what one might expect, the resilient pattern outlined by low depression levels over time was the most frequent. Instead, relative to other patterns, common grief pattern was infrequent enough. These findings are in line with Bonanno's (2004) review, indicating that most people facing a potentially traumatic experience showed resilience. Despite there is still lack of evidence in the context of palliative care, some research has attempted to get a glimpse into the psychological factors related to the risk of grief disorder. As one way to better grasp the considerable variation in grief reactions, several authors have zeroed in on the crucial role of attachment style (Bowlby, 1969). Indeed, the attachment system may be undermined by the loss of a loved one. For example, in a study including a sample of 157 family caregivers of cancer patients assisted in palliative home care, Lenzo et al. (2022a) found that discomfort with closeness and relationship as secondary, which are two dimensions of the high order factor of avoidance attachment, moderated the effect of the perceived support on the severity of grief symptoms. Another relevant finding of this study was the need to consider together psychological and social factors. So doing this might then offer a way to grasp the interplay among variables responsible for grief reaction, which can improve the efficacy of any psychological intervention.

3. Discussion

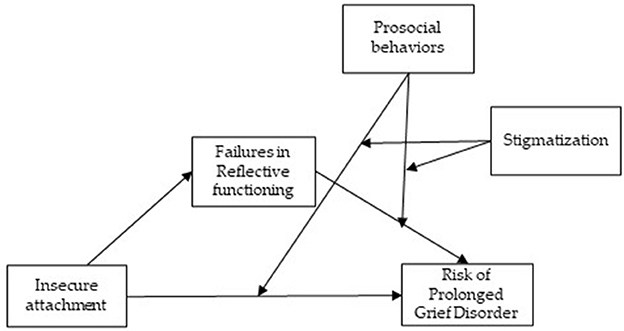

A lot of attention has been directed toward understanding psychological factors underneath grief reactions. However, bereavement theories identifying hypothetical stages of mourning have left unanswered many important questions. A major limitation of this kind of theory is the idea that grief resolution progressed in a linear fashion (Rothaupt and Becker, 2007). The evidence seems to offer a different outline of the factors explaining grief reactions. First of all, contrary to what can be expected, most of the people facing potentially traumatic events showed psychological resilience (Mancini and Bonanno, 2009). Moreover, grief reactions tend to be more complex than what the linear model can explain. Another major limitation concerns the risk of pathologizing grief by introducing a mental disorder related to grief (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Since its introduction, a considerable debate has characterized literature, though most people agreed that Prolonged Grief Disorder could be deemed a mental disorder (Tang et al., 2020). Friends or relatives of family caregivers may stigmatize symptoms experienced by the bereaved (Johnson et al., 2009), though engagement in activities to help them is frequent. Any intentional behavior aimed to benefit another is defined as “prosocial” (Dunfield, 2014; Geraci and Franchin, 2021). Prosocial behaviors appear early in development and play a fundamental role during the life span of humans. There is evidence that prosocial behavior fosters social support, promotes resilience, and improves mental health as well as the quality of life (Ramkissoon, 2022). Yet, prosocial behavior may arise from positive psychological conditions as well as negative ones (Vollhardt, 2009). Although research has mostly focused on its development, prosocial behaviors may play a role in grief reactions among the bereaved. Prevention of PGD, indeed, may be fostered by prosocial behavior around the bereaved caregivers. For example, family associations composed of individuals who had similar experiences could help the bereaved caregivers by sharing coping strategies. Also, other prosocial behaviors offered by family associations such as comforting those who are hurt can alleviate emotional distress and reduce the fear of stigmatization. In this research field, understanding the relationships between these variables remains challenging and more studies are needed. Research has already demonstrated that personality traits are associated with regulations of social behavior (Fiddick et al., 2016). Yet, the possible presence of psychopathology can decrease moral judgment as well as engage in prosocial behavior (Memmott-Elison and Toseeb, 2022). Besides increasing our comprehension of grief reactions, knowledge of prosociality would have much other practical value. Several studies converged in suggesting that prosocial behaviors might have a positive impact on stress (Brown and Brown, 2015; Raposa et al., 2016; Lazar and Eisenberger, 2022). Undoubtedly, prosocial behaviors in response to negative states such as helping, sharing, caring, and comforting may alleviate emotional distress. As already stated, high levels of insecure attachment seem to be associated with the severity of symptoms (Lenzo et al., 2022a). Likewise, low levels of certainty about mental states tend to be related to more symptoms of anxiety and depression (Lenzo et al., 2022b). With few exceptions (Carr et al., 2001; Stroebe et al., 2005), when considering family caregivers of patients deceased in palliative care, social support is paramount (Logan et al., 2018). The relationships between personality traits and prosocial behaviors might be meaningful but not straightforward. In pursuing this question, it could be reasonable to hypothesize that prosocial behavior plays as a moderator of the relationship between insecure attachment and failures in mentalizing, on one hand, and the risk of PGD, on the other hand (Figure 1). At the very least, a deeper understanding of the pathways from individual differences in personality traits to prosocial behavior may be able to lead to more efficacy psychological interventions (Caprara et al., 2012), especially at a time like this. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the fore the relevance of prosocial behavior. Findings of several studies have hitherto well-established the impact of the pandemic on mental health among people (Lenzo et al., 2022c,d), even though protective factors such as resilience contribute to lower it (Lenzo et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic also offers an unprecedented opportunity to grasp the mechanisms underneath prosociality and loss. For instance, restrictive measures and social distancing following the spread of contagion have undoubtedly increased loneliness, which increases negative consequences for mental and physical health (Ernst et al., 2022). Still, restrictive measures in hospitals or funerals without the presence and held remotely may increase the risk of PGD (Wallace et al., 2020). In this vein, prosocial behavior is of utmost relevance to mitigate the potential negative effect of the pandemic. In conclusion, more attention to the underlying psychological factors of negative grief reactions, as well as to the interplay between social behaviors and bereavement, would represent an encouraging approach to prevent PGD among family caregivers of patients deceased in palliative care.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Aoun, S., Breen, L., O'Connor, M., Rumbold, B., and Nordstrom, C. (2012). A public health approach to bereavement support services in palliative care. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 55, 14–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00825.x

Bisconti, T. L., Bergeman, C. S., and Boker, S. M. (2006). Social support as a predictor of variability: an examination of the adjustment trajectories of recent widows. Psychol. Aging. 21, 590. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.590

Boelen, P. A., and Prigerson, H. G. (2007). The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 257, 444–452. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0744-0

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 59, 20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Bonanno, G. A. (2009). The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us About Life After Loss. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bonanno, G. A., Wortman, C. B., Lehman, D. R., Tweed, R. G., Haring, M., Sonnega, J., et al. (2002). Resilience to loss and chronic grief: a prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 1150–1164. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1150

Brown, S. L., and Brown, R. M. (2015). Connecting prosocial behavior to improved physical health: Contributions from the neurobiology of parenting. Neurosc. Biobeh. Rev. 55, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.004

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., and Eisenberg, N. (2012). Prosociality: the contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1289. doi: 10.1037/a0025626

Carr, D., House, J. S., Wortman, C., Nesse, R., and Kessler, R. C. (2001). Psychological adjustment to sudden and anticipated spousal loss among older widowed persons. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 56, S237–S248. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.S237

Dunfield, K. A. (2014). A construct divided: prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Front. Psychol. 5, 958. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00958

Ernst, M., Niederer, D., Werner, A. M., Czaja, S. J., Mikton, C., Ong, A. D., et al. (2022). Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 77, 660. doi: 10.1037/amp0001005

Fiddick, L., Brase, G. L., Ho, A. T., Hiraishi, K., Honma, A., Smith, A., et al. (2016). Major personality traits and regulations of social behavior: Cheaters are not the same as the reckless, and you need to know who you're dealing with. J. Res. Pers. 62, 6–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.02.007

Geraci, A., and Franchin, L. (2021). Is defensive behavior a subtype of prosocial behaviors? Front. Psychol. 12, 678370. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678370

Gonschor, J., Eisma, M. C., Barke, A., and Doering, B. K. (2020). Public stigma towards prolonged grief disorder: Does diagnostic labeling matter? PLoS. ONE. 15, e0237021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237021

Guldin, M. B., Vedsted, P., Zachariae, R., Olesen, F., and Jensen, A. B. (2011). Complicated grief and need for professional support in family caregivers of cancer patients in palliative care: A longitudinal cohort study. Support. Car. Cancer. 20, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1260-3

Holmes, T. H., and Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 11, 213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4

Hudson, P., Hall, C., Boughey, A., and Roulston, A. (2018). Bereavement support standards and bereavement care pathway for quality palliative care. Palliat. Support. Care. 16, 375–387. doi: 10.1017/S1478951517000451

Italian Association of Medical Oncology (2021). Available online at: https://www.aiom.it/wpcontent/uploads/2021/10/2021_NumeriCancro_web.pdf (accessed February 19, 2023).

Italian Ministry of Health (2018). Rapporto al Parlamento sullo stato di attuazione della Legge. Available online at: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2814_allegato.pdf (accessed February 19, 2023).

Johnson, J. G., First, M. B., Block, S., Vanderwerker, L. C., Zivin, K., Zhang, B., et al. (2009). Stigmatization and receptivity to mental health services among recently bereaved adults. Death. Stud. 33, 691. doi: 10.1080/07481180903070392

Lazar, L., and Eisenberger, N. I. (2022). The benefits of giving: effects of prosocial behavior on recovery from stress. Psychophysiology 59, e13954. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13954

Lenzo, V., Quattropani, M. C., Musetti, A., Zenesini, C., Freda, M. F., Lemmo, D., et al. (2020). Resilience contributes to low emotional impact of the covid-19 outbreak among the general population in Italy. Front. Psychol. 11, 576485. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576485

Lenzo, V., Sardella, A., Grazia, V., Corsano, P., Quattropani, M. C., Franceschini, C., et al. (2022d). Fear of COVID-19 and future orientation: different profiles in dealing with the pandemic and associations with loneliness and posttraumatic growth. Psychol. Trauma. doi: 10.1037/tra0001319

Lenzo, V., Sardella, A., Musetti, A., Faraone, C., and Quattropani, M. C. (2022a). Toward a preventive approach to prolonged grief disorder in palliative care: insecure attachment moderates the impact of perceived support on the severity of symptoms. PLoS. ONE. 17, e0266289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266289

Lenzo, V., Sardella, A., Musetti, A., Freda, M. F., Lemmo, D., Vegni, E., et al. (2022c). The relationship between resilience and sleep quality during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 14, 41. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S344042

Lenzo, V., Sardella, A., Musetti, A., Petralia, M. C., Grado, I., Quattropani, M. C., et al. (2022b). Failures in reflective functioning and reported symptoms of anxiety and depression in bereaved individuals: a study on a sample of family caregivers of palliative care patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 11930. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191911930

Lichtenthal, W. G. (2018). Supporting the bereaved in greatest need: we can do better. Palliat Support Care. 16, 371–374. doi: 10.1017/S1478951518000585

Logan, E. L., Thornton, J. A., and Breen, L. J. (2018). What determines supportive behaviors following bereavement? A systematic review and call to action. Death. Stud. 42, 104–114. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2017.1329760

Lundorff, M., Holmgren, H., Zachariae, R., Farver-Vestergaard, I., and O'Connor, M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disorders. 212, 138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030

Mancini, A. D., and Bonanno, G. A. (2009). Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: toward an individual differences model. J. Pers. 77, 1805–1832. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00601.x

Memmott-Elison, M. K., and Toseeb, U. (2022). Prosocial behavior and psychopathology: An 11-year longitudinal study of inter- and intraindividual reciprocal relations across childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 12, 1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0954579422000657

Prigerson, H. G., Boelen, P. A., Xu, J., Smith, K. V., and Maciejewski, P. K. (2021). Validation of the new DSM-5-TR criteria for prolonged grief disorder and the PG-13-Revised (PG-13-R) scale. World. Psych. 20, 96–106. doi: 10.1002/wps.20823

Ramkissoon, H. (2022). Prosociality in times of separation and loss. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 45, 101290. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.008

Raposa, E. B., Laws, H. B., and Ansell, E. B. (2016). Prosocial behavior mitigates the negative effects of stress in everyday life. Clin. Psychol. Sc. 4, 691–698. doi: 10.1177/2167702615611073

Rosner, R., Comtesse, H., and Vogel, A. (2021). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder. J. Affect. Disorders. 287, 301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.058

Rothaupt, J. W., and Becker, K. (2007). A Literature Review of Western Bereavement Theory: From Decathecting to Continuing Bonds. Fam. Jour. 15, 6–15. doi: 10.1177/1066480706294031

Schomerus, G., and Angermeyer, M. C. (2008). Stigma and its impact on help-seeking for mental disorders: what do we know? Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 17, 31–37. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00002669

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., and Stroebe, W. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 370, 1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9

Stroebe, W., Zech, E., Stroebe, M. S., and Abakoumkin, G. (2005). Does social support help in bereavement? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 24, 1030–1050. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.1030

Tang, S., Chow, A. Y. M., Breen, L. J., and Prigerson, H. G. (2020). Can grief be a mental disorder? An online survey on public opinion in mainland China. Death. Stud. 44, 152–159. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2018.1527415

Vollhardt, J. R. (2009). Altruism born of suffering and prosocial behavior following adverse life events: a review and conceptualization. Soc. Just. Res. 22, 53–97. doi: 10.1007/s11211-009-0088-1

Wallace, C. L., Wladkowski, S. P., Gibson, A., and White, P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J. Pain. Symptom. Manage. 60, e70–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

World Health Organization. (2004). Cancer Pain Release. Available online at: http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/cancer_pain_release/en/ (accessed December 30, 2022).

Keywords: clinical psychology, prolonged grief, prosociality, palliative care, health psychology

Citation: Lenzo V and Quattropani MC (2023) Psychological factors and prosociality as determinants in grief reactions: Proposals for an integrative perspective in palliative care. Front. Psychol. 14:1136301. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1136301

Received: 03 January 2023; Accepted: 08 March 2023;

Published: 28 March 2023.

Edited by:

Clare Killikelly, University of Zurich, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Maria Luisa Martino, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Lenzo and Quattropani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vittorio Lenzo, dml0dG9yaW8ubGVuem9AdW5pY3QuaXQ=

Vittorio Lenzo

Vittorio Lenzo Maria C. Quattropani

Maria C. Quattropani