- 1Faculty of Psychology, Sigmund Freud University, Vienna, Austria

- 2Association for Psychotherapy, Counselling, Supervision and Group Facilitation, Vienna, Austria

- 3Institute for Person-Centered Studies, Vienna, Austria

Introduction: Preliminary research based on everyday observations suggests that there are people, who experience severe fear when addressing others with their personal names. The aim of this study was to explore the extent to which this hitherto little-known psychological phenomenon really exists and to investigate its characteristic features, considering the everyday experience of not being able to use names and its impact on affected individuals and their social interactions and relationships.

Methods: In this mixed-methods study based on semi-structured interviews and psychometric testing, 13 affected female participants were interviewed and evaluated using self-report measures of social anxiety, attachment-related vulnerability, and general personality traits. An inductive content analysis and inferential statistical methods were used to analyze qualitative and quantitative data, respectively.

Results: Our findings show that affected individuals experience psychological distress and a variety of negative emotions in situations in which addressing others with their name is intended, resulting in avoidance behavior, impaired social interactions, and a reduced quality of affected relationships.

Discussion: The behavior can affect all relationships and all forms of communication and is strongly linked to social anxiety and insecure attachment. We propose calling this phenomenon Alexinomia, meaning “no words for names”.

1. Introduction

“It has always been like that, as long as I can remember. I couldn’t address others with their names, and it took extreme efforts to try. I became really conscious of it, when I met my husband. I wanted to address him by name, but I could not do it. That’s when I realized that it’s a problem, that I can’t say other people’s names.”

In this article, we present an unknown psychological phenomenon characterized by knowing a name but being unable to use it in personal communication. For affected individuals, it is impossible to say, for example, “Good morning, Maria.” or “Armin! Great to see you.” They experience acute anxietiy and a variety of other negative emotions in social situations in which using a personal name is intended. We refer to this undocumented psychological phenomenon as Alexinomia. Alexinomia is a compound of the Greek loanwords á (a-, “not”) + λέξεις (léxis, “words”) + óνoμα (ónoma, “name”) and literally means “no words for names.”

Personal names—in the context of this article defined as first names, given names, and forenames, rather than last names, family names—are of substantial social importance (Horne, 1986). We use personal names to address and to greet others, to personalize conversation, and to call people over a distance. Names can be indicative of a person’s gender (Cassidy et al., 1999), age group (Lansley and Longley, 2016), socio-economic status (Bloothooft and Onland, 2011), and often have a literal or connotative meaning that people identify with (Brennen, 2000). In many situations, personal names are deliberately used to show respect, affection, and to create closeness. In this way, names determine our social interactions and, on an intra-individual level, are a fundamental factor for the sense of personal identity (Dion, 1983; Alford, 1987; Pilcher, 2016; Watzlawik et al., 2016).

The significance of using names in personal conversations has been highlighted in research in various fields. In education it has been claimed that teachers knowing and using the students’ names creates an atmosphere of trust and community in the classroom that facilitates learning (Glenz, 2014). It has been argued that calling students by their names makes them feel cared about and taken seriously (Syverud, 1993). Deliberately using first names to establish connection and equality in a relationship is a well-established technique in sales and in other persuasion-based occupational areas (DeCormier and Jackson, 1998). Furthermore, the importance of using names has been discussed in psychoanalytic texts in the context of the unpleasant effects of forgetting someone’s name on the affected individual (Murphy, 1957).

From a psychological perspective, the subjective experience of fear related to addressing others by name was preliminarily described by Welleschik (2019). Based on personal observations and unsystematic online research, Welleschik (2019) portrayed the case of a young woman who was unable to say her partner’s name. The preliminary findings provided by this research suggest that being unable to address others by name has severe consequences for personal and professional life. With partners, friends, and family, not saying their names may be considered impersonal or even rude and can create a social distance that is usually neither intended nor appreciated. In other situations, such as work meetings or at school, being unable to name others can heavily limit someone’s options, for example, when it comes to speaking up in groups, attracting attention, or to nuance conversation in a professional manner. The impact of this behavior on relationships is significant and concerns both the primarily affected individuals and the people around them. In severe cases, affected persons report to have never used their spouse’s name or have not said anyone’s name in many years.

Welleschik (2019) made references to the reports of other cases of affected individuals found online, which in the meantime have been confirmed by a systematic analysis of 257 online forum and blog posts by people expressing a problem in the specific social context of addressing others with their names (Bergert et al., unpublished data). Given the large scope of these materials, it is surprising that this distinct phenomenon is still undocumented. So far, there is no published scientific evidence based on systematic, empirical research showing that alexinomia really exists and describing how it affects those concerned and their relationships. The number of affected individuals is unknown, and so are the origins and causes of the problem.

To address the most fundamental open questions related to alexinomia, an explorative mixed-methods study was employed that expanded qualitative (i.e., interview) with quantitative (i.e., psychometric) data. To identify the experiential grounds and constituting factors of alexinomia, we employed a descriptive approach to inquiry using qualitative semi-structured interviews and inductive content analysis.

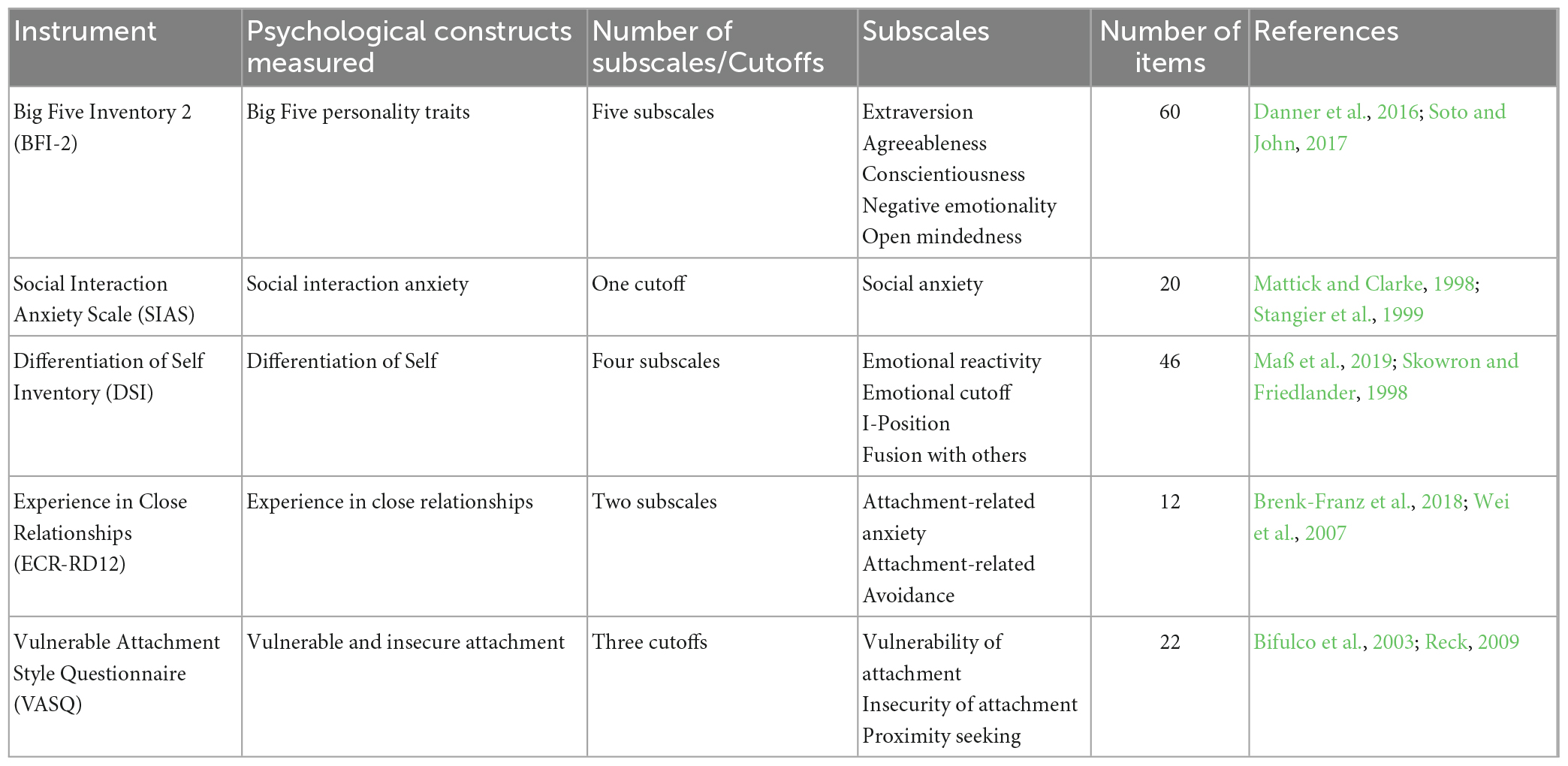

In addition, a psychometric test battery, including a set of standardized psychological self-report questionnaires, was administered to test for links of alexinomia with already known psychological constructs. Given the social importance of names and the social nature of the situations in which alexinomia seems to occur most frequently, social anxiety was considered a likely candidate to underly the problem. The role of names in identity formation (Watzlawik et al., 2016) and the differentiation of oneself and others (Palsson, 2014) led us to assume that these factors are likely to play a crucial role in alexinomia. Further, alexinomia-related symptoms seem to become more severe the closer the affected relationship is. Therefore, it seemed likely that problematic name saying could originate from attachment-related vulnerabilities and insecurities. Additionally, a test of general personality traits (i.e., big 5) was administered to test for general peculiarities that might arise in the personality structure of individuals with alexinomia. See Table 1 for a complete list of all instruments.

By expanding qualitative data with already known psychological attributes using quantitative parameters, our intention was to provide an as comprehensive a picture of the phenomenon as possible. The method and results sections are therefore divided into qualitative and quantitative procedures and results. In the discussion, we draw links between the different levels of data and give a summarizing interpretation that allows a first systematic conceptualisation of alexinomia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

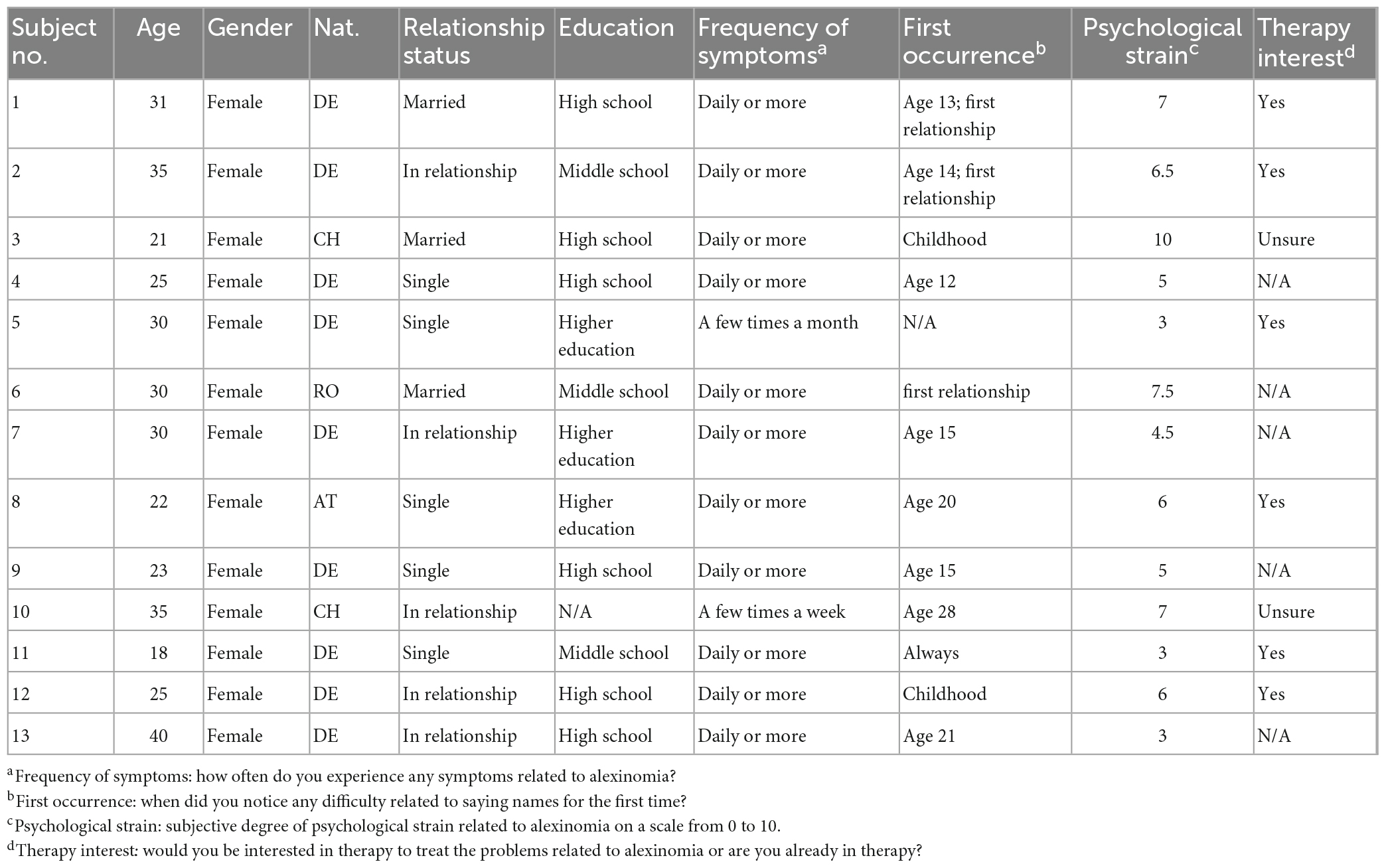

Thirteen German-speaking women with a mean age of 28.1 years (range: 18–40 years) participated in the study. Participants were recruited from a patient database created by one of the authors (L.W.) in response to letters from affected individuals that were received via the author’s personal website1 over the past few years. At the time of data collection, the database included about 80 entries of affected individuals from all genders and many countries. Most contacts belonged to the group of young, female, German-speaking adults. Hence, for the purpose of this study, we recruited participants from this largest group of available contacts. The sample size was determined after iteratively analysing the contents of the first interviews. Once the central conceptual categories had emerged and started reappearing throughout most of the interviews, we stopped the sampling process.

Out of these 13 participants, 11 indicated noticing the problem of not being able to use names daily or multiple times per day. Nine participants reported noticing it for the first time as a child or teenager. The degree of psychological strain caused by the problem was rated as 5.7 on average (min = 3; max = 10; scale: 0–10). A summary of participants’ socio-demographic data and descriptive data with regards to the symptoms of alexinomia are shown in Table 2.

2.2. Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all participants to explore in depth their everyday lived experience in relation to using names. An interview guide including a set of open-ended questions was prepared before data collection that was flexible as to the sequence of questions and adapted according to the responses of the interviewees. The interview guide was structured into three main topics: (1) General experiences with the phenomenon of having difficulty addressing someone by their name, (2) coping strategies and (3) self-theories on alexinomia-related symptoms. This interview structure ensured that participants could develop their narratives openly to maximize our understanding of the phenomenon by allowing participants’ own frame of reference and concepts to unfold naturally (Willig, 2013). Where necessary, the interviewers posed individualized follow-up questions to be responsive to the interviewees and encourage them to expand on their experiences, feelings and/or self-theories. Follow-up questions were either probing questions aimed at further elaboration or specifying questions.

At the end of the interview, the interviewers asked for the relevant socio-demographic data that would allow for a sufficient contextualization of the interview data. The following factors were addressed: age, gender, partnership, the highest level of education, occupation, frequency of experiencing difficulties with using names (How often do you experience these difficulties?), history (When did it first occur?), personal psychological strain (0 to 10), and interest in a therapy to treat the problem.

2.3. Psychometric measures

The following psychometric instruments were used to measure personality factors that might be linked to alexinomia. We used the German versions of all listed scales: (1) Big Five Inventory (BFI-2; Soto and John, 2017): The BFI-2 assesses the Big Five personality domains Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Negative Emotionality, and Open-Mindedness; (2) Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick and Clarke, 1998): The SIAS measures the degree of psychological distress when interacting with other people and provides a cutoff score for Social Anxiety (i.e., generalized irrational fears across numerous social situations with avoidance and impairments) (3) Differentiation of Self Inventory (DSI; Skowron and Friedlander, 1998): A measure of the ability to experience intimacy with and independence from others; the test includes the subscales Emotional Reactivity (i.e., the degree to which a person responds to environmental stimuli with emotional flooding, emotional lability, or hypersensitivity), Emotional Cutoff (i.e., feeling threatened by intimacy and feeling excessive vulnerability in relationships with others), I-Position (i.e., presence of a clearly defined sense of self and the ability to thoughtfully adhere to one’s convictions when pressured to do otherwise), and Fusion with Others (i.e., emotional overinvolvement with others, including triangulation and overidentification with parents); (4) Experience in Close Relationships (ECR-RD12; Wei et al., 2007): Assesses individual differences with respect to Attachment-related Anxiety (i.e., the extent to which people are insecure vs. secure regarding the availability of and responsiveness to the people they are romantically involved with) and Attachment-related Avoidance (i.e., the extent to which people feel uncomfortable being close to others vs. secure in depending on others); and (5) Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ; Bifulco et al., 2003): This instrument provides a total measure of the Vulnerability of Attachment including the subscales Insecurity of Attachment (i.e., feelings and attitudes relating to discomfort with, or barriers to, closeness with others, including inability to trust and hurt or anger at being let down) and Proximity Seeking (i.e., dependence on others and approach behavior).

All instruments are listed in Table 1.

2.4. Study design

The study was designed following a mixed-methods approach by which qualitative data as the primary source of data were expanded with quantitative data. This design allowed us to fully exploit the breadth of content and scope by using different methods for different parts of the study (Kuckartz, 2014). Therefore, we aimed at characterizing the phenomenon of interest based on the qualitative data and supplementing it with the results of psychometric testing to also situate it in existing psychological discourses.

The two parts of the study were conducted in the following order: (i) interview and (ii) psychometric testing. Interviews were conducted for each participant individually with two interviewers (T.D. and L.W.). Due to the security measures in place at the time of the data collection caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted online using the video meeting software Microsoft Teams (Microsoft 365, Version 1.5.00.22362). Video and audio channels were used for the entire meeting by all parties. Audios were recorded using an external digital voice recorder (Olympus WS-853, Tokyo) placed next to the interviewers’ computers. The video was not recorded. Participants were informed about the audio recordings prior to the start of the interviews. Participants were also informed about the general aim of the study and the interview procedure, stating that the interview will address how people with alexinomia feel and how it affects everyday life. Additionally, participants were informed about the GDPR-conform processing of personal data. Raw data audio files were kept on secure storage media at the university and stored locally and separately from any identifying personal data. Participants gave written consent to all described procedures.

The interviews lasted 32–61 min, with a mean duration of 42.2 min. For the second part of the study, the link to the questionnaire was provided by email. The online questionnaire was realized using SoSci Survey (Leiner, 2019) and was made available to participants on the website https://onlinebefragungen.sfu.ac.at/. It included five standardized psychological instruments (Table 1). There were 160 items in total; completing the questionnaire took about 60 min. All participants fully completed all parts of the study. All procedures were approved by the Sigmund Freud University (SFU) ethics committee.

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Analysis of qualitative data

The interviews were transcribed word for word. Content analysis focused on summarizing the main topics directly uttered, therefore, dialect and intonation were not transcribed. All interviews were conducted and analyzed in German. Participants’ quotes presented as text examples in this paper were translated from German to English by the authors for publishing purposes. Translations were made literally, meaning that the translation was kept as close as possible to the original wording but that the grammar rules of the target language (English) were applied. Personal data (i.e., names, places, etc.) were replaced with pseudonyms.

The interview data were coded according to Mayring’s procedure of an inductive, summarizing content analysis (Mayring, 2014, 2015). Mayring’s methodical concept is particularly useful at the interface with quantitative methods to enable the triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data. The procedure employs a hermeneutical logic in assigning categories to text passages, resulting in a hierarchical category scheme of main categories and subcategories of multiple order. This procedure aims at reducing a large body of data to its relevant thematic constituents, identifying a content structure, which can unravel and display the different layers of a phenomenon.

The inductive, summarizing coding process was structured into the following seven steps (Mayring, 2014): (1) Defining the category, (2) paraphrasing all utterances of all interviews that were relevant according to category definition, (3) generalizing the paraphrases to their main content, (4) first reduction, (5) second reduction, (6) listing all identified categories in the form of a category scheme, and (7) revising the category scheme including repetition of steps 2–5 in case the categories and codes did not work for additional data.

Further, the category scheme was summarized by revising the list of categories and generalized again by combining categories with similar meanings, thus identifying main- and subcategories. This step was repeated multiple times to carve out the main factors of the phenomenon.

The category definition focused on the identification of all relevant intra- and inter-personal factors characterizing the phenomenon of having difficulty with saying names in everyday practice including interactions where it occurs and their subjective experience, coping strategies when it happens, and self-theories on the development of the difficulty throughout the lifespan. To ensure reliability, two researchers coded the first interview. From this first interview, the initial main categories as well as the subcategories were created and on this practice the coding guidelines for the analysis of further interviews were developed. According to these guidelines, all other interviews were coded independently by two researchers.

2.5.2. Analysis of quantitative data

To analyze the questionnaire data, participants’ test scores were subjected to a series of summary independent-samples t-tests, one for each subscale of each instrument for which norm data (i.e., sample sizes, means, and standard deviations) were available. These instruments were the BFI-2, DSI, and ECR-RD12. Questionnaires using cutoff-scores to indicate the presence or absence of a psychological trait (i.e., SIAS and VASQ) were analyzed separately for each subscale using one-sample t-tests tested against these respective cutoff values. The alpha-level was set to 0.05 for all analyses. All p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons (Holm-Bonferroni) across the entire data set. Hedges’ g is reported for all analyses as a measure of effect size.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative data

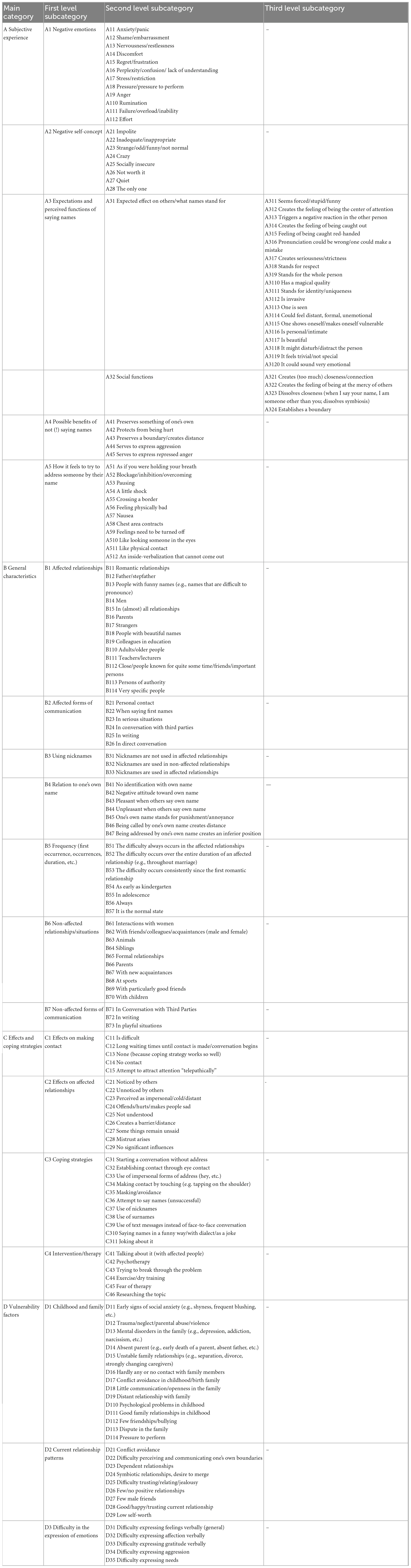

We identified the following four main categories that, based on our data, constitute alexinomia: (1) Factors of subjective experience when trying to address others by their personal names such as emotional states and physical reactions, (2) general characteristics of alexinomia such as first occurrences, affected relationships, and affected forms of communication, (3) effects on relationships and on communication in relationships and strategies to cope, (4) vulnerability factors based on biographical information and current relationship patterns. Table 3 shows the complete category scheme in detail. In the following, the main categories are presented with significant quotes from the interviews to support our conclusions. In addition, the most important subcategories are elaborated to detail the phenomenon.

3.1.1. Factors of subjective experience

All participants in the study reported having problems with addressing persons by their names. When, for instance, asked to describe the problem in their own words, they said:

It has always been like that, as long as I can remember, in kindergarten, in school. I couldn’t address classmates with their names, and it took extreme efforts to try. I used to think twice about whether I really needed to say the name, whether my question was important enough or not. (…) I then became really conscious of it, when I met my husband about one and a half years ago. I wanted to address him by name, but I could not do it. I wanted to, but I couldn’t. That’s when I realized that it’s a problem, that I can’t say other people’s names. (…) I tried to practice his name alone, because I thought maybe it’s because I’m afraid that I pronounce it wrong or something like that, and I still couldn’t do it. And yes, even to this day it’s still difficult for me to address him by name, I always say “you” or “hey,” things like that (Participant 3).

It’s very difficult for me to call someone by name, but also when I talk about someone, to say the name. (…) I always say “I was walking with my neighbor” or “I meet with my fellow student.” I wouldn’t say their first names. That’s when I really notice how difficult it is for me, no matter whether it’s a good friend or not such a good friend, to say the name. (…) To give an example, I was helping in the field to dig up potatoes. We were up at the back of the harvester and my ex-boyfriend was driving the tractor. And then the ladies who were also helping asked me to please tell him to slow down, otherwise it’s going too fast. I was completely overwhelmed, and I shouted “Hey, hey, hey!”, because I just could not call the first name. He didn’t hear me and finally one of the other ladies then said his first name and he then heard that and stopped. So that was a situation where they actually hoped for me to tell him to please slow down. But I just couldn’t do it, I just didn’t call his name, I said “Hey, hey!”, I was like, I failed (Participant 8).

in situations in which saying a name is intended, participants frequently reported experiencing negative emotions such as anxiety/panic, shame/embarrassment, regret/frustration, and feelings of inadequacy/failure. These feelings are often accompanied by unpleasant physical reactions that, for example, were described as “a tight feeling in the chest” (Participant 10) and were compared to how it feels to “touch someone” (Participant 11) and “to look someone into the eyes” (participant 11). In the words of participant 2:

It feels almost a bit like the beginning of a panic attack. Like loss of control and nervousness, agitation (…) a feeling of discomfort, an “I’m about to be the center of attention” feeling or like when you have to give a lecture, like stage fright, really extremely uncomfortable and scary. It’s insecurity. Insecurity (Participant 2).

Participants further highlighted what seems to be a complex relationship of the inability to say a name and the control of closeness and distance in a (often romantic) relationship. While about half of our participants reported experiencing forms of alexinomia in all their social relationships (7 participants), several participants reported that the problem became more severe the closer the relationship (4 participants) and many claimed that it is strongest in romantic relationships (10 participants). Saying the name of a loved one was frequently described as too close, too personal, too intimate, and thus overwhelming and emotionally exposing. Therefore, some affected individuals speculated that not saying a name could have the function of keeping the other person at a certain distance. This distance, however, puts strain on the relationship and affected individuals expressed a strong desire to be able to overcome it. Almost contrary to the above situations, for some participants using names was also described as distancing and impersonal, as if using a partner’s personal name would take away “the magic” (participant 4) between them and thus create an unwanted distance. Along these lines, some participants indicated the use of names deliberately to control the distance in a relationship. Participant 10 described the dilemma of a deep longing for closeness and worries about the vulnerability that would come with it as follows: “I’m not sure if I would be able to cope with this, this closeness that would then be there. The vulnerability that would then be there, although this is what I want so badly.” (Participant 10).

Participant 12 addressed the complexity of the impact of naming on the experienced closeness or distance in social relationships:

It’s strange, at first I thought that somehow it had something to do with closeness, but then I realized that on the other hand you can use it very well to maintain distance. It’s somehow this autonomy, closeness, distance, where that plays a big role, especially with hierarchies, like bosses or superiors, or in love relationships, where you’re kind of afraid of showing yourself vulnerable, where you think “oh, there is suddenly someone above yourself.” (…) There is also a bit of fear that it sounds funny for him because I might pronounce it somehow special or that he could hear my emotions because of me pronouncing it somehow differently. (…) To me, saying his name would feel closer, but when he says my name, I feel more of a distance. Because everybody calls me that. It’s nothing special (Participant 12).

3.1.2. General characteristics

Affected relationships included mainly romantic relationships, close friends, and family. However, several participants reported experiencing alexinomia in all relationships, regardless of the level of closeness. Hierarchy seems to play a role in a way that the symptoms are more severe in interactions with persons of authority such as bosses, superiors, and teachers. For example:

At school it was sometimes unpleasant to address teachers by name, especially those who were very authoritarian. (…) I couldn’t say the names of people who were hierarchically superior. (…) In relationships with a power dynamic it is more pronounced (Participant 7).

Some participants indicated that the severity of the problem also depends on the name in question. Unusual names, names that are difficult to pronounce, and names that are considered particularly beautiful or unattractive can make the symptoms more severe.

Other factors that contribute to the name saying difficulties of our participants included the relationship to one’s own name, whether one likes to be addressed by name or not, and the general attitude toward naming others and being named by others. Most participants said that they liked to be addressed by name and that they considered it a sign of respect. Some participants, however, associated being called by the name with a certain seriousness that feels strict, cold, and generally unpleasant. Interestingly, even in very severe cases of alexinomia, there were usually certain individuals whose names could be said (e.g., the name of a pet animal or of a sibling).

Frequently, the symptoms of alexinomia extend to conversations with others about the person with the problematic name. For some participants however, the symptoms were limited to only direct personal conversations. Participant 1 described the situation of saying her partner’s name when talking to someone else about her partner while him being present: “With very great restraint and with a low tone, it works. But so that he almost doesn’t hear it. It’s unpleasant, but I somehow manage.” (Participant 1) In conversations with others, names are often avoided even if the respective person is absent by refering to their social role such as “my friend,” “my cousin,” etc. Symptoms can be less severe in written compared to verbal direct communication. About half of our particpants have no difficulty writing someone’s name in Emails and texts. For participant 1 it “just feels safer in writing.” Other participants on the other hand indicated avoiding names also in writing, for example participant 13 who prefers to use nick names, such as “sweetheart” to greet a female friend in a written conversation.

Characteristically the signs of alexinomia were there from the very beginning of the affected relationships and, if untreated, were present throughout the entire duration of the relationship. Most of our participants reported that they recall having the problem since they were children or teenagers or that it “has always been there” (participant 11). In several cases, participants first noticed having the problem in their first romantic relationship.

3.1.3. Effects and coping mechanisms

Alexinomia affects communication in relationships in a multitude of ways. Instead of using names, most affected individuals reported starting a conversation without using a personal address or by using an impersonal address such as “Hey” or “Hi.” Often, they would wait for some time before saying something until they got the addressees’ attention via eye contact, physical touch (e.g., tapping on the shoulder) or using “telepathy” (Participant 10). If none of these worked, several participants reported that they would rather stay silent and forget about the intended conversation than using the name. To give an example:

I wait for eye contact. When sitting at a large table with many people talking, it’s sometimes a bit difficult. I really have to wait until he looks directly at me and then say, “Can you please pass me something?”. So stupid. Or just “You” or “Hey,” so rude actually. Or I touch him, tap him and just start talking. (…) Anyway, apparently I have done really well, no one has noticed until now (Participant 2).

According to some participants, it sometimes helps to use nicknames or to say the name in a playful way (4 participants). Most participants, however, said that using nicknames was also not an option for them (9 participants).

While these compensatory strategies can help avoiding names and hiding the problem successfully, alexinomia can put a serious strain on a relationship due to the distance and insecurities that it facilitates in both partners:

With my husband, I notice that it burdens him. (…) He spoke to me directly about it and said that he thinks it’s a shame that I never address him by his name. He said that it annoys him and that he finds it impersonal and kind of disrespectful, like when you’re not looking at each other in a conversation. That’s how it feels, like I’m looking away. I then tried to explain to him, it’s just the opposite. (…) It is very hard for me to realize that he feels offended and put down. We have very, very different views on what it means that I am not saying his name (Participant 1).

When my partner confronted me, that was actually the most unpleasant thing, it was like getting caught, “Oh my God, now someone has caught me, after all these years someone has now really caught me.” Yes, that was the most unpleasant thing. (…) It was very, very, very embarrassing, I felt ashamed that I had to admit having a problem with this. It was a feeling of extreme shame (Participant 2).

It burdens me, because I see that it burdens him. Because he says that he is also a normal person, like me, and that he also needs love and to hear his name from my mouth and that he never gets that from me. I get it from him, but he does not get it (Participant 6).

3.1.4. Vulnerability factors

The main purpose of this study was to describe alexinomia with regards to its main characteristics and attributes, thus the underlying causes of the problem will be the subject of future research. However, there were details that were mentioned multiple times in the interviews that could constitute factors of vulnerability which might contribute to the development and maintenance of alexinomia. From the category of biographical details participants mentioned early signs of social anxieties as a child (e.g., shyness; blushing; etc.), childhood trauma, violence, and neglect, and the presence of psychological disorders such as depression, addiction, and personality disorders in the family. From the category of current relationship patterns participants displayed a tendency to avoid conflicts and to enter symbiotic relationships and to have low levels of self-esteem and self-confidence in relationships and social interactions. Another category was formed from reports of having difficulty in expressing emotions. Participants reported having problems with expressing emotions in general and especially with verbally expressing love, affection, and gratefulness (3 participants).

3.2. Quantitative data

All participants completed all questionnaires. There were no missing data and no outliers. Therefore, all available data was included in the analysis.

3.2.1. Big Five personality traits (BFI-2)

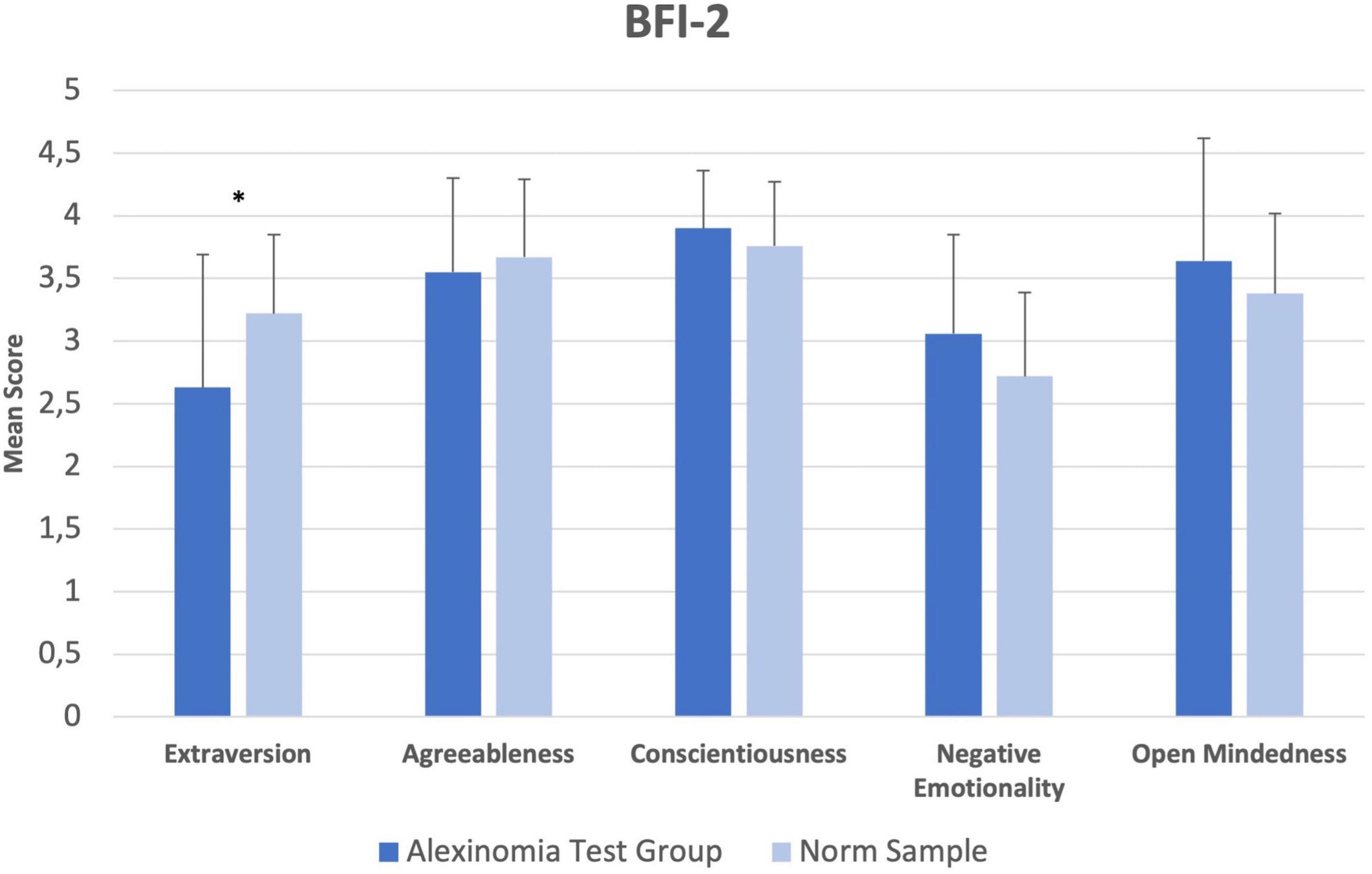

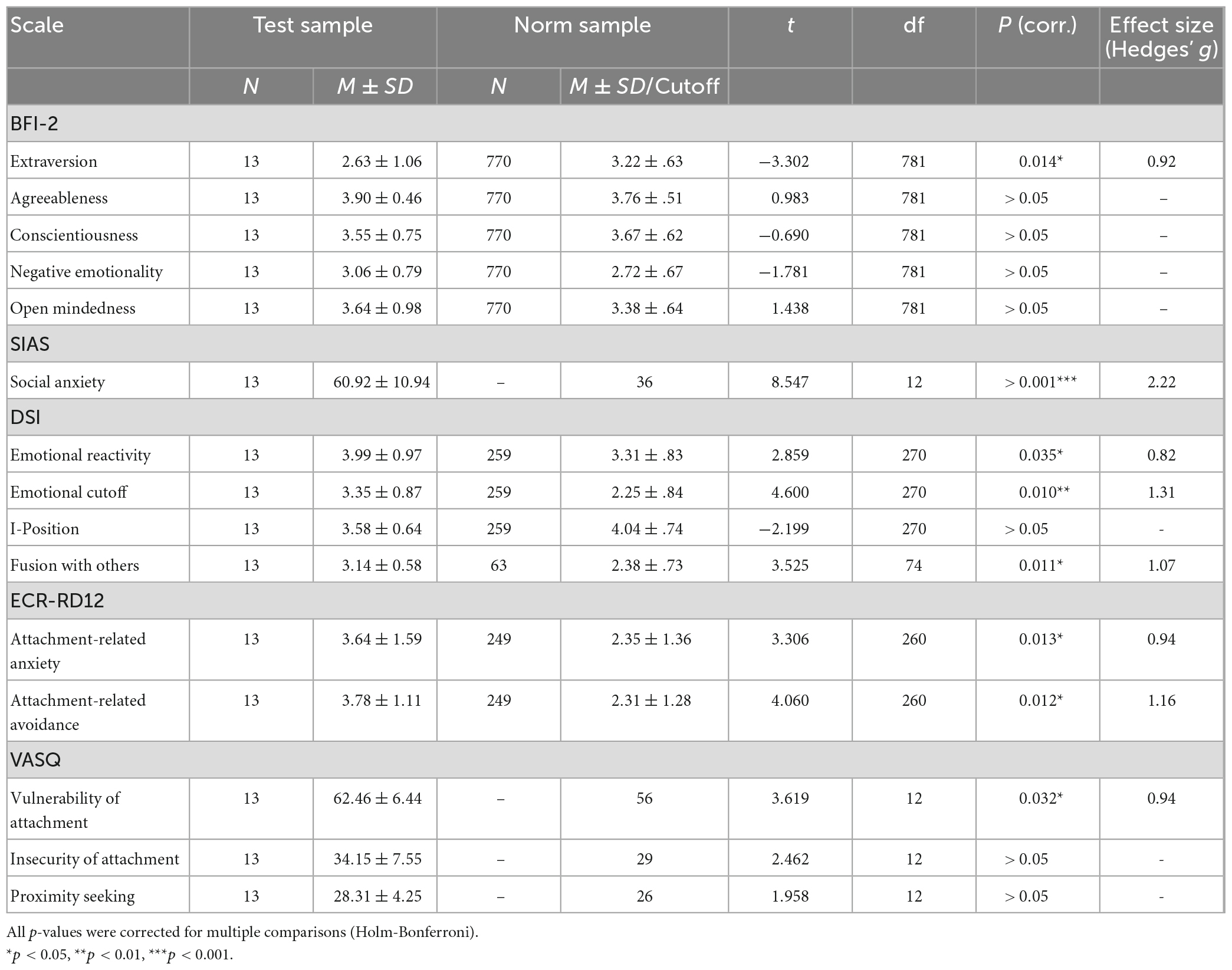

Summary independent-samples t-tests were calculated for each of the five subscales of the BFI-2. The mean test score of the test group was significantly lower in the scale Extraversion (M = 2.63; SD = 1.06) compared with norms (M = 3.22; SD = 0.63), t(781) = -3.302, p = 0.014, g = 0.92. Comparisons of the other subscales were not significant (Figure 1).

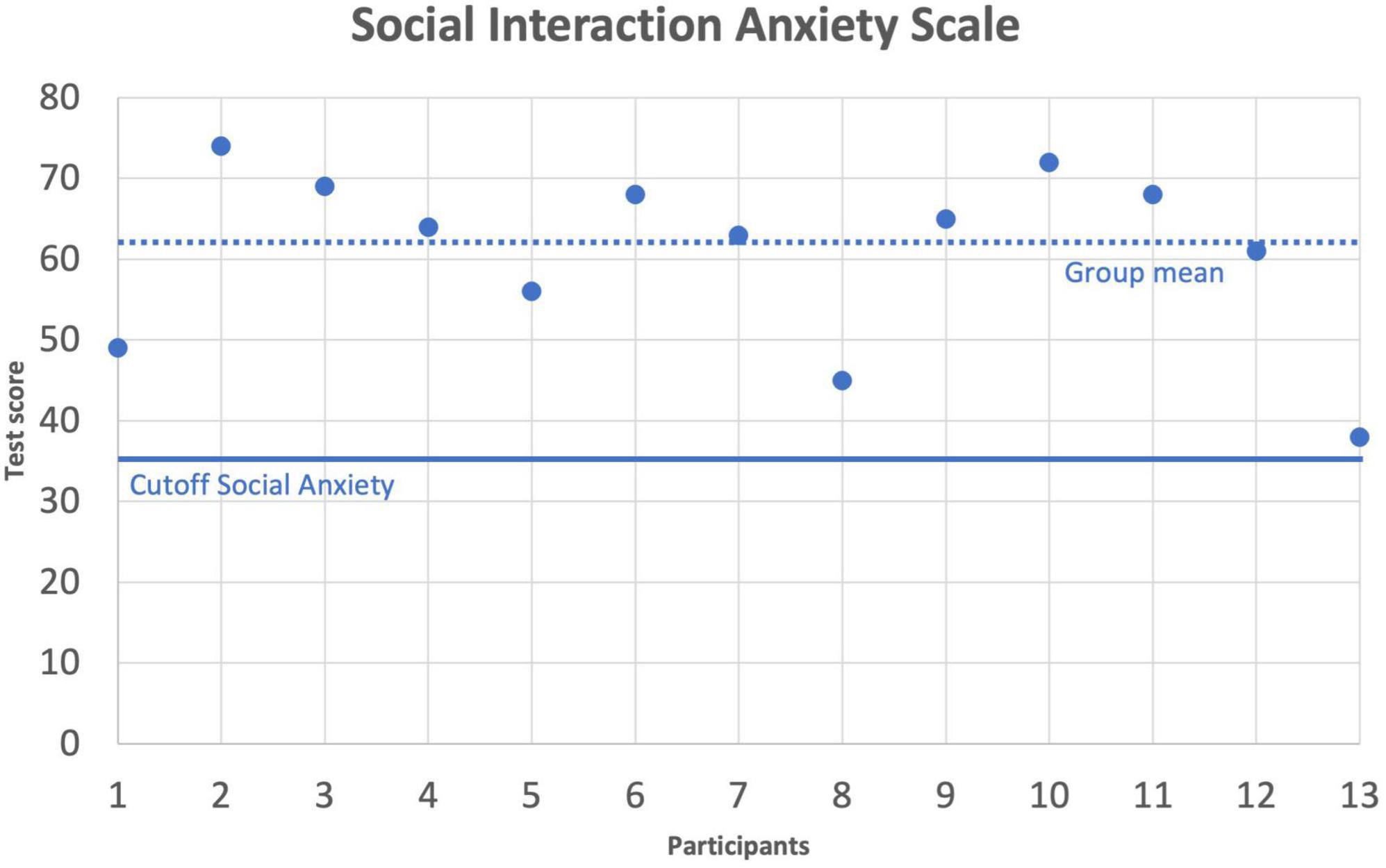

3.2.2. Social anxiety (SIAS)

To analyze data related to social anxiety as measured by the SIAS, participants’ test scores were compared with the cutoff value for social anxiety. All participants scored above the cutoff of 36 which indicates the presence of social anxiety (Mattick and Clarke, 1998). The group mean in the SIAS was M = 60.92 (SD = 10.94). A one-sample t-test against the test value of 35 confirmed a significant group effect for social anxiety, t(12) = 8.547, p < 0.001, g = 2.22 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS). Individual scores and group mean (dotted line) in the SIAS. The solid line indicate the SIAS cutoff value for social anxiety.

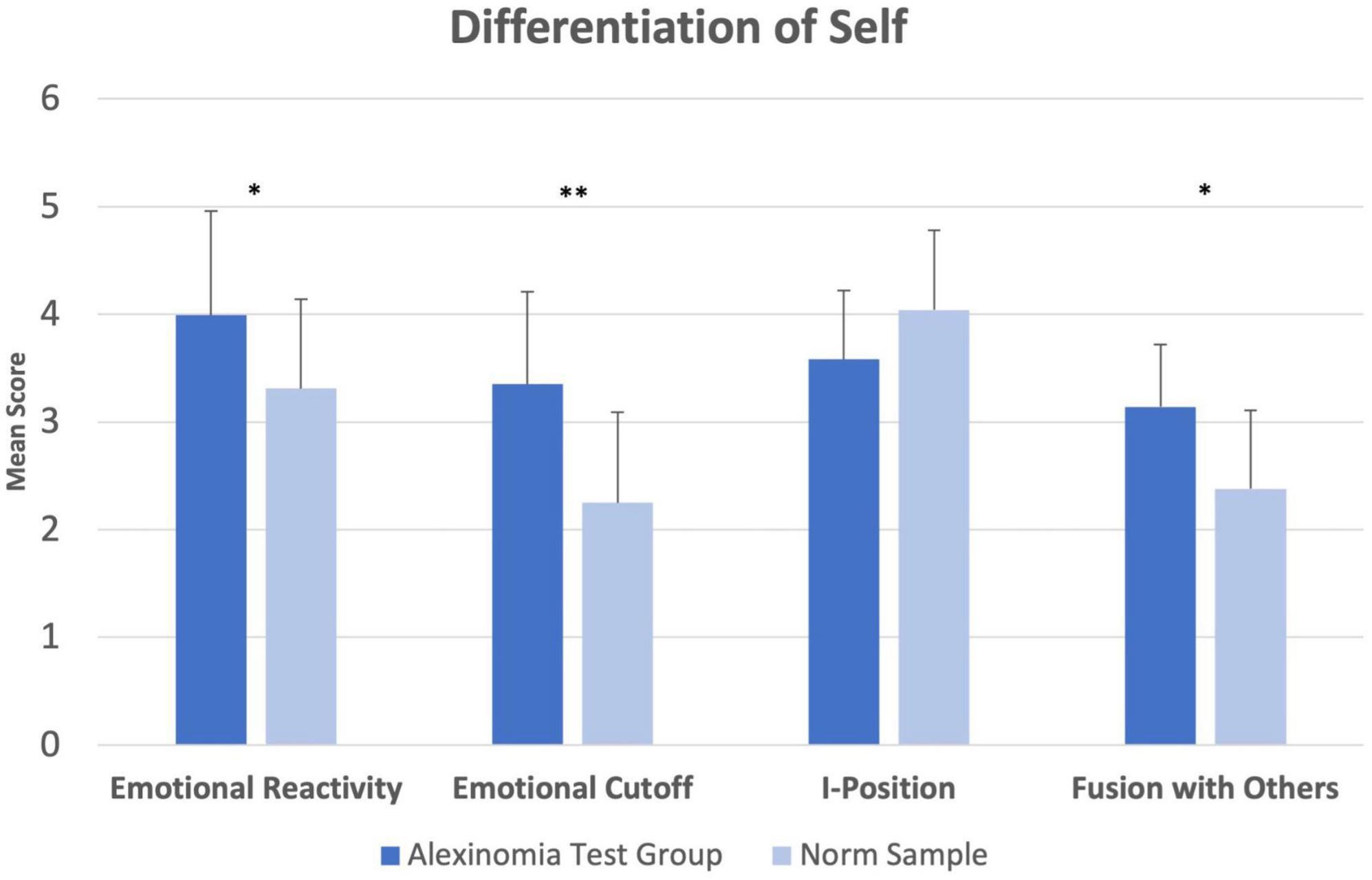

3.2.3. Differentiation of self (DSI)

The four scales of the DSI were analyzed using summary independent-samples t-tests. Group means were compared to norm data. This comparison revealed significantly higher scores of the test group compared with norms in the following scales: Emotional Reactivity (M = 3.99; SD = 0.97 vs. M = 3.31; SD = 0.83; t(270) = 2.859, p = 0.035, g = 0.82), Emotional Cutoff (M = 3.35; SD = 0.87 vs. M = 2.25; SD = 0.84; t(270) = 4.600, p = 0.010, g = 1.31), and Fusion with Others (M = 3.14; SD = 0.58 vs. M = 2.38; SD = 0.73; t(74) = 3.525, p = 0.011, g = 1.07). Comparisons of the subscale I-Position were not significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Differentiation of Self Inventory (DSI). Comparisons of group means in the DSI. Error bars indicate 1 SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.1.

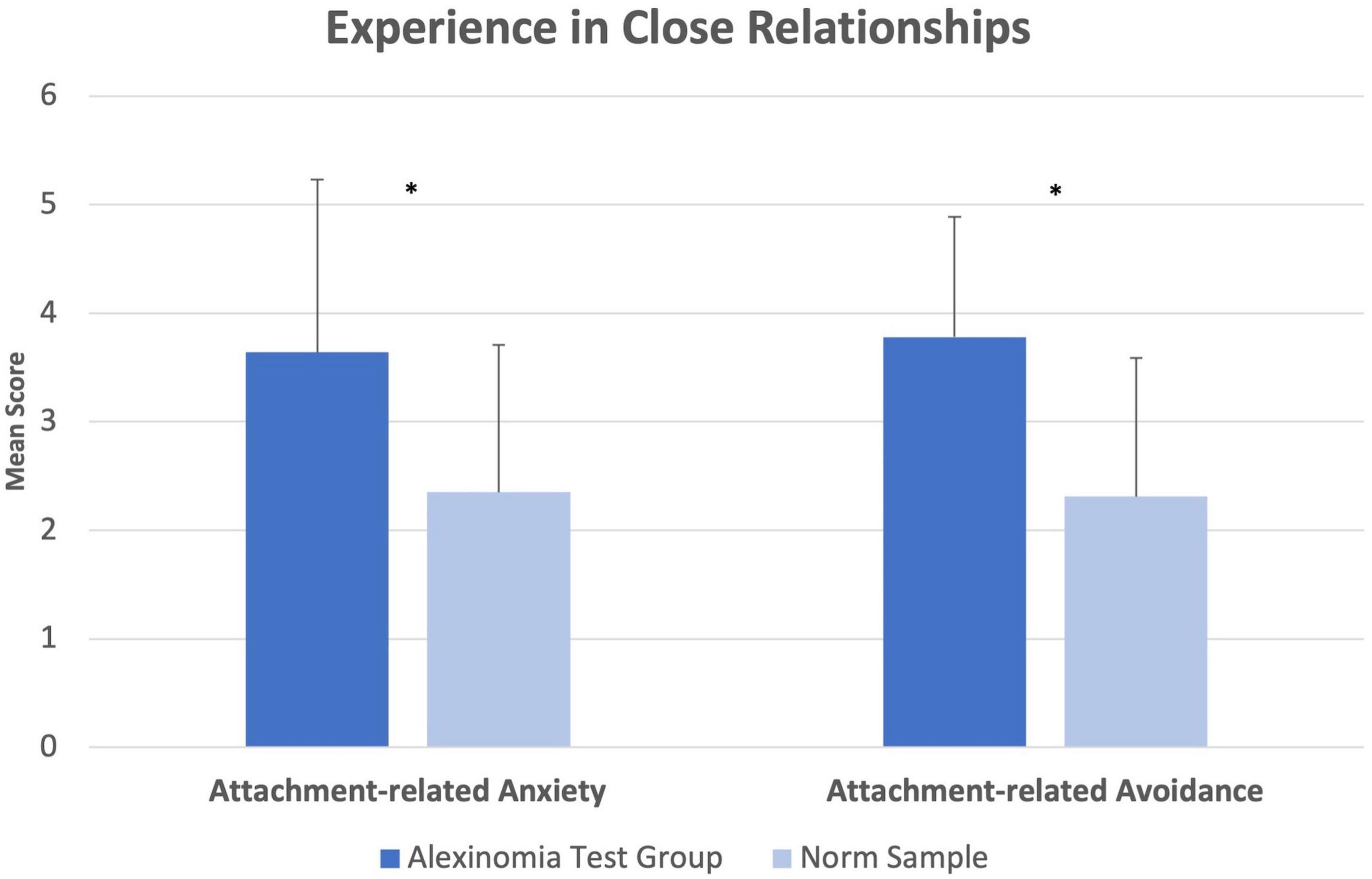

3.2.4. Experience in close relationships (ECR-RD12)

Our sample differed significantly from norms in both scales of the ECR-RD12, Attachment-related Anxiety (M = 3.64; SD = 1.59 vs. M = 2.35; SD = 1.36; t(260) = 3.306, p = 0.013, g = 0.94) and Attachment-related Avoidance (M = 3.78; SD = 1.11 vs. M = 2.31; SD = 1.28; t(260) = 4.060, p = 0.012, g = 1.16) as revealed by summary independent-samples t-tests (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Experience in Close Relationships (ECR-RD12). Comparisons of group means in the ECR-RD12. Error bars indicate 1 SD. *p < 0.05.

3.2.5. Vulnerability of attachment (VASQ)

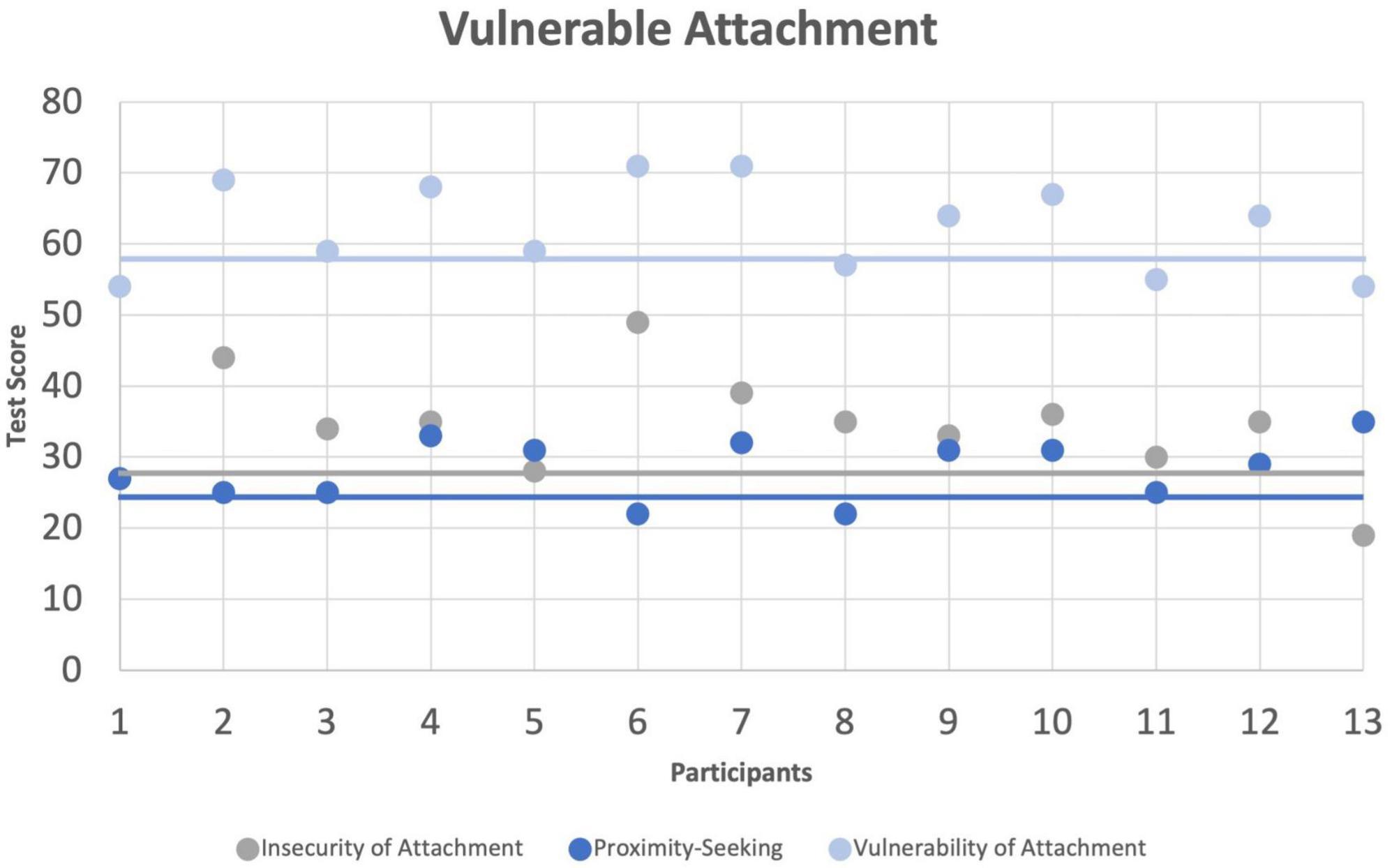

The VASQ includes three scales, and it offers cutoff values for each of these. In our sample, 10 out of 13 participants scored above the cutoff of 57 which indicates the presence of general Vulnerability of Attachment. The cutoff for the scale Insecurity of Attachment of 30 was met or exceeded by 10 participants and eights participants scored 27 or higher in the scale Proximity Seeking (Figure 5). One-sample t-tests against the respective test values of each scale showed a significant group effect for Vulnerability of Attachment, t(12) = 3.619, p = 0.032, g = 0.94. Differences in the other scales were not significant (ps > 0.05).

Figure 5. Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire (VASQ). Individual scores in the VASQ. Lines indicate VASQ cutoff values for the respective scales.

Table 4 shows a summary of the results of the quantitative analysis of questionnaire data.

To summarize, results from psychometric testing show that our sample of individuals affected by alexinomia fulfilled the criteria for the presence of social anxiety both on individual and group levels. In addition, participants scored significantly higher on several attachment- and relationship-related anxiety and vulnerability scales compared with the respective norms. The ability to regulate emotions was reduced and participants showed decreased levels of extraversion. This pattern of results is well in line with previous research showing that social anxiety is related to insecure attachment (Manning et al., 2017), impaired regulation of emotions (Jazaieri et al., 2015), and negatively correlated with extraversion (Kaplan et al., 2015).

Taken together, and as a very first attempt to conceptualize alexinomia from a clinical diagnostics point of view, data from both qualitative and quantitative analyses suggest the following key symptoms of alexinomia: (i) The individual experiences fear or anxiety in situations, in which using personal names is intended; (ii) Intending to use a name almost always provokes fear or anxiety in the individual in at least one relationship; (iii) the feared situations are avoided or dealt with using compensatory strategies, (iv) the fear, anxiety, or avoidance is persistant; (v) the fear, anxiety, or avoidance causes significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

This preliminary symptom list is based on the diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), is not exhaustive and should be seen as a first proposal to the scientific community to inspire the generation of new hypotheses to testify the construct in a more rigorous statistical fashion.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore and describe the distinctive features of alexinomia—a previously unknown and scientifically undocumented psychological phenomenon characterized by an inability to use personal names in communication. Using a mixed-methods approach combining qualitative data from personal interviews with participants who are personally affected by alexinomia, and quantitative data gained from psychometric testing of the same sample, our findings allowed us to describe alexinomia on a phenomenological level and to get an understanding of its key attributes and potential links to other psychological constructs including social anxiety and attachment.

Results indicated that all participants had the desire to use personal names in everyday social interactions, especially in their closest relationships. The phenomenological experience of alexinomia, however, is that of an inability to do so. This inability is accompanied by feelings of anxiety, panic and physical as well as psychological discomfort. The affected individuals’ experience is further characterized by feelings of regret, embarrassment, and shame, especially when confronted with their behavior by others.

Our data suggest that alexinomia usually occurs for the first time in childhood or adolescence and is then ongoing. It affects all forms of relationships and communication and is strongest in romantic relationships and in direct verbal communication. Interestingly, the problem becomes increasingly severe the closer the relationship, which often puts a heavy strain on also the romantic relationships of the people affected. There operates a painful ambiguity in individuals affected by alexinomia in the form of a longing for closeness and intimacy in a relationship on the one hand and feelings of vulnerability and being emotionally overwhelmed, that come with saying a loved ones’ name on the other hand. Such feelings of emotional exposure and fear of unbearable closeness seem to constitute the core features of the name saying avoidance behaviors described here.

Results based on the analysis of psychometric tests suggest a strong link between alexinomia-related behaviors and social anxiety (Stein and Stein, 2008). All participants of our sample fulfilled the criterion for the presence of social phobia according to the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (Mattick and Clarke, 1998). This finding is well in line with the main findings from the interviews showing that feelings of anxiety and embarrassment are among the main symptoms of alexinomia. Social anxiety has been shown to be linked to low intimacy and decreased satisfaction in romantic relationships (Davila and Beck, 2002; Rodebaugh, 2009) and, thus, can also be conceptualized from an attachment viewpoint. Participants in our study displayed increased levels of attachment-related anxiety and avoidance as measured by the ECR-RD12 and vulnerability of attachment as measured by VASQ. These findings indicate that those affected by alexinomia are insecure with regards to the availability of and responsiveness to the people they are romantically involved with and tend to feel uncomfortable being close to others. Moreover, measures of the ability to experience intimacy with and independence from others, indicated increased levels of emotional reactivity (i.e., emotional flooding, emotional lability, or hypersensitivity), increased levels of feeling threatened by intimacy, and an emotional overinvolvement with others, including triangulation and overidentification with parents. Additionally, our sample showed significantly lower levels of extraversion compared with norms as measured by the BFI-2. These results from standardized psychological instruments are well in line with the qualitative data gained from the interviews.

Taken together our findings based on both qualitative and quantitative data suggest alexinomia lies at the center of where social anxiety, fear of attachment, and impaired emotional processing with regards to social interactions meet.

Several additional factors that relate to and/or potentially interact with alexinomia were observed but not elaborated in depth in the present study. These included participants’ attitudes toward their own names, whether they liked their name and being called by it or not and its co-existence with related phenomena of impaired communication, including an inability to call one’s parents “Mom” and “Dad” and to say “I love you.” So far, we do not have any data on whether or not affected individuals are able to say and write their own names. Another potentially directly related concept is name idealization in in-love couples, which, together with name avoidance, has been suggested to be a sign of the partners’ name being a taboo (Leisi, 1980).

Alexinomia should be differentiated from physical and cognitive impairments that affect the ability to produce language, known as aphasia. Also, alexinomia is not caused by impaired memory for names. Further, deliberately refusing to say someone’s name to humiliate a person or to show dominance or disrespect, in our opinion, is also fundamentally different from the type of name avoidance described here.

Our sample consisted of German-speaking women aged between 18 and 40 years, therefore all conclusions drawn from this study are limited to this sociocultural group, which was selected based on the availability of contacts of affected individuals. With these limitations in generalizability of our findings in mind, findings from ongoing online research suggest alexinomia to be prevalent also in other sociocultural groups (unpublished data). Hence, future research will explore whether alexinomia also occurs in other genders, age groups, cultural regions and how it is affected by language and cultural aspects of naming and name usage in everyday language. A scale to measure the precence and severity of alexinomia-related symptoms is warranted for statistically validating the construct further and for the development of a clinical diagnostic. Future quantitative research on larger samples might further address the prevalence of alexinomia in the general population, its neurobiological foundations, and psychosocial origins and causes. Not at least, the research presented here was mainly focused on the impact of alexinomia on primarily affected individuals. However, our findings also suggest a significant impact on family and other affiliates; therefore, looking at these secondarily affected individuals will be another important next step in this line of research to further understand alexinomia and to work toward a potential treatment of it.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Sigmund Freud University (SFU) Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

TD and LW collected the data. TD and NR analyzed the data. TD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NR wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexis Bergert, Sara Jakaj, Mara Sartorio, and Katharina Süss for their help with data collection and data processing. We also thank Claus-Christian Carbon and Jaan Valsiner for their valuable comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Alford, R. (1987). Naming and Identity: a Cross-Cultural Study of Personal Naming Practices. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

Bifulco, A., Mahon, J., Kwon, J.-H., Moran, P. M., and Jacobs, C. (2003). The vulnerable attachment style questionnaire (VASQ): an interview-based measure of attachment styles that predict depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 33, 1099–1110. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008237

Bloothooft, G., and Onland, D. (2011). Socioeconomic determinants of first names. Names A J. Onomatics 59, 25–41. doi: 10.1179/002777311X12942225544679

Brenk-Franz, K., Ehrenthal, J., Freund, T., Schneider, N., Strauß, B., Tiesler, F., et al. (2018). Evaluation of the short form of “experience in close relationships”(revised, german version “ECR-RD12”)-A tool to measure adult attachment in primary care. PLoS One 13:e0191254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191254

Brennen, T. (2000). On the meaning of personal names: a view from cognitive psychology. Names A J. Onomatics 48, 139–146. doi: 10.1179/nam.2000.48.2.139

Cassidy, K. W., Kelly, M. H., and Sharoni, L. J. (1999). Inferring gender from name phonology. J. Exp. Psychol. General 128, 362–381. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.128.3.362

Danner, D., Rammstedt, B., Bluemke, M., Treiber, L., Berres, S., Soto, C. J., et al. (2016). Die deutsche Version des Big Five Inventory 2 (BFI-2). Mannheim: GESIS – Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. doi: 10.6102/ZIS247

Davila, J., and Beck, J. G. (2002). Is social anxiety associated with impairment in close relationships? a preliminary investigation. Behav. Therapy 33, 427–446. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80037-5

DeCormier, R. A., and Jackson, A. (1998). Anatomy of a good sales introduction - part I. Ind. Commercial Training 30, 255–262. doi: 10.1108/00197859810242879

Dion, K. L. (1983). Names, identity, and self. Names A J. Onomatics 31, 245–257. doi: 10.1179/nam.1983.31.4.245

Horne, M. D. (1986). Potential significance of first names: a review. Psychol. Rep. 59, 839–845. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1986.59.2.839

Jazaieri, H., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P. R., and Gross, J. J. (2015). The role of emotion and emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 17:531. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0531-3

Kaplan, S. C., Levinson, C. A., Rodebaugh, T. L., Menatti, A., and Weeks, J. W. (2015). Social anxiety and the big five personality traits: the interactive relationship of trust and openness. Cogn. Behav. Therapy 44, 212–222. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2015.1008032

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Mixed Methods: Methodologie, Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren. Berlin: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-93267-5

Lansley, G., and Longley, P. (2016). Deriving age and gender from forenames for consumer analytics. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 30, 271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.02.007

Leisi, E. (1980). Aspekte der namengebung bei liebespaaren. Beiträge Zur Namenforschung Heidelberg 15, 351–360.

Manning, R. P. C., Dickson, J. M., Palmier-Claus, J., Cunliffe, A., and Taylor, P. J. (2017). A systematic review of adult attachment and social anxiety. J. Affect. Disorders 211, 44–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.020

Mattick, R. P., and Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav. Res. Therapy 36, 455–470. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt. Available online at: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

Mayring, P. (2015). “Qualitative content analysis: theoretical background and procedures,” in Approaches to Qualitative Research in Mathematics Education: Examples of Methodology and Methods, eds A. Bikner-Ahsbahs, C. Knipping, and N. C. Presmeg (Berlin: Springer), 365–380. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_13

Maß, R., Schottke, M.-L., Borchert, A.-M., Ellermann, P. M., Jahn, L.-M., and Morgenroth, O. (2019). Die deutsche version des differentiation of self inventory. Zeitschrift Für Klinische Psychologie Und Psychotherapie 48, 17–28. doi: 10.1026/1616-3443/a000495

Murphy, W. F. (1957). A note on the significance of names. Psychoanalytic Quart. 26, 91–106. doi: 10.1080/21674086.1957.11926047

Palsson, G. (2014). Personal names: embodiment, differentiation, exclusion, and belonging. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 39, 618–630. doi: 10.1177/0162243913516808

Pilcher, J. (2016). Names, bodies and identities. Sociology 50, 764–779. doi: 10.1177/0038038515582157

Reck, C. (2009). Translation of the Vulnerable Attachment Style Questionnaire into German [Unpublished protocol]. Germany: University of Heidelberg.

Rodebaugh, T. L. (2009). Social phobia and perceived friendship quality. J. Anxiety Disorders 23, 872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.05.001

Skowron, E. A., and Friedlander, M. L. (1998). The differentiation of self inventory: development and initial validation. J. Couns. Psychol. 45, 235–246. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.235

Soto, C. J., and John, O. P. (2017). The next big five inventory (BFI-2): developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113, 117–143. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000096

Stangier, U., Heidenreich, T., Berardi, A., Golbs, U., and Hoyer, J. (1999). Die erfassung sozialer phobie durch social interaction anxiety scale (SIAS) und die social phobia scale (SPS). [assessment of social phobia by the social interaction anxiety scale (SIAS) and the social phobia scale (SPS).]. Zeitschrift Für Klinische Psychologie 28, 28–36. doi: 10.1026//0084-5345.28.1.28

Stein, M. B., and Stein, D. J. (2008). Social anxiety disorder. Lancet 371, 1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2

Syverud, K. (1993). Taking students seriously: a guide for new law teachers. J. Legal Educ. 43, 247.

Watzlawik, M., Guimarães, D. S., Han, M., and Jung, A. J. (2016). First names as signs of personal identity: an intercultural comparison. Psychol. Soc. 8, 1–21.

Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., and Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in close relationship scale (ECR)-short form: reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 88, 187–204. doi: 10.1080/00223890701268041

Welleschik, L. (2019). Von der Unfähigkeit, andere mit ihrem namen anzusprechen oder: das namenssyndrom‘. Beiträge Zur Namenforschung 54, 1–13.

Keywords: social anxiety, fear, attachment, identity, names, addressing, alexinomia

Citation: Ditye T, Rodax N and Welleschik L (2023) Alexinomia: The fear of using personal names. Front. Psychol. 14:1129272. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1129272

Received: 21 December 2022; Accepted: 03 March 2023;

Published: 17 March 2023.

Edited by:

Anastassia Zabrodskaja, Tallinn University, EstoniaReviewed by:

Waqar Husain, COMSATS University Islamabad, PakistanDamaris Nübling, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany

Copyright © 2023 Ditye, Rodax and Welleschik. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thomas Ditye, dGhvbWFzLmRpdHllQHNmdS5hYy5hdA==

Thomas Ditye

Thomas Ditye Natalie Rodax1

Natalie Rodax1 Lisa Welleschik

Lisa Welleschik