94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 10 May 2023

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1127194

Purpose: Prosocial behavior (PSB) plays a critical role in everyday society, especially during the pandemic of COVID-19. Understanding the underlying mechanism will provide insight and advance its implementation. According to the theory of PSB, social interaction, family and individual characters all contribute to its development. The current study aimed to investigate the influencing factor of PSB among Chinese college students during COVID-19 outbreak. This is an attempt to understand the mechanism of PSB and to provide a reference for the formulation of policies aimed at promoting healthy collaborative relationships for college students.

Method: The online questionnaire was administered to 664 college students from 29 provinces of China via Credamo platform. There were 332 medical students and 332 non-medical students aged between 18 and 25 included for final study. The mediating role of positive emotion/affect (PA) and the moderating role of parental care in the association between social support and PSB during the pandemic of COVID-19 was explored by using Social Support Rate Scale (SSRS), Prosocial Tendencies Measurement Scale (PTM), The Positive and Negative Affect (PANAS), as well as Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI). The process macro model of SPSS was adopted for mediating and moderating analysis.

Results: The results showed that social support positively predicted PSB among Chinese college students, even after adding PA as a mediation variable. PA during COVID-19 mediated the association between social support and PSB. PSB also revealed as a predictor of PA by regression analysis. Moreover, the moderating effect of parental care in the relationship between PA and PSB was detected.

Conclusion: PA under stress acts as a mediator between social support and PSB. This mediating effect was moderated by PC in childhood. In addition, PSB was observed to predict PA reversely. The promoting factors and path between the variables of PSB are complex and need to be explored extensively. The underlying factors and process should be further investigated for the development of intervention plans.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a serious global public health emergency (Word Health Organization, 2020). The pandemic created a huge crisis for individuals, triggering stress responses both physically and psychologically (Tang et al., 2021). There is a growing need for the public to be involved voluntarily in the prevention work (Gallaway et al., 2020). It has been pointed out that the effective implementation of policies for controlling the pandemic is largely dependent upon compliance from the public (Han et al., 2023). The pandemic situation brought collective pressure and a rapid switch in daily life. Face-to-face communications have been greatly reduced, accompanied by negative emotions. The pandemic has also brought about major challenges to the implementation of disease prevention policies in public health. Supportive interactions were proven to show benefits in promoting public compliance, even only via daily efforts such as frequent hand washing, wearing masks and maintaining social distancing (Alzyood et al., 2020; Howard et al., 2021; Deng and Chen, 2022). These public measures, and interpersonal support, can contribute to PSB when it relates to social expectations and benefit other groups and society (Huang, 2004). This can be an effective indicator for individual mental health (Son and Padilla-Walker, 2020; Alvis et al., 2022) and moral development (Eisenberg et al., 2002b), encouraging individuals to adapt effectively to society and secular moral standards.

Prosocial behavior is considered a positive reaction mode gradually developed in the process of integrating self and the external world. The cultivation of PSB in young adults is of great significance to their individual psychological development (Yang et al., 2015). It has been demonstrated that adolescents present more helping behaviors during critical situations, including in the COVID-19 pandemic (Liu et al., 2021; Alvis et al., 2022; Sweijen et al., 2022). Though the pace of life and learning habits were greatly affected, college students still presented more helping behaviors (Rotenberg et al., 2005) in this period. It is worthwhile to explore the underlying mechanisms of PSB in college students. Furthermore, it should be taken into consideration how psychological and external environmental factors initialise and stimulate helping behaviors, and whether prosocial behavior in turn promotes emotional health (Liu et al., 2021).

Although, the reasons for “helping” conduct become increasingly complicated with age. The PSB for teenagers may reflect their enhanced sense of social moral responsibility (Carlo et al., 2003; Brandenberger, 2005). It has been proposed that PSB originates from the internalization of social ethics in the early years of life (Helena and Bernardes, 1997; Hardy and Carlo, 2005). The research on children and adolescents also found that PSB showed longitudinal continuity in different stages of development (Luengo Kanacri et al., 2014). It was suggested that paying attention to prosocial behavior education in childhood, is helpful to the development of moral personality (Winer, 2013), in terms of the cultivation of specific prosocial behaviors, that have been gradually integrated into family and school education (Reiman, 2009). The concept of PSB education in other cultural backgrounds has confirmed this observation (Yu, 2010). At the same time, according to the motivation theory (Gan and Zuo, 2006), PSB is also related to the activation of appropriate external environmental factors under internalized moral norms. In emergency situations, emotional factors play a major role in the decision-making process of PSB. It has been pointed out that a positive mood promotes prosocial behavior (Kou and Tang, 2004).

According to the information processing model of social adaptation (Crick and Dodge, 1994), the connection between intention and behavior of PSB contact was affected by individual abilities and needed to be promoted. On the other hand, social learning theory indicates that individual behavior characteristics are mainly affected by the social environment (Bandura, 1977). College students are at the stage of rapid changes in psychological development and are immersed in more social information beyond family and school. They have a greater desire to willingly participate in peer interaction and are inclined to show more helpful behavior (Yang et al., 2020).

Generally speaking, theories about PSB primarily emphasize the interaction of social, family and individual characteristics. The perspective of social support, an individual’s emotional state and family-rearing history, should be taken into consideration (Zhang, 2017). With a decrease in interpersonal communication during the pandemic, it is worthwhile to explore the underlying mode of cultivation of PSB. The promotion of PSB can be discussed from the cross-sectional and longitudinal dimensions, as well as the internal and external factors of individuals. Besides, it would strengthen the theoretical basis for the cultivation of PSB in young adults (China Central Television (CCTV), 2021).

Social support refers to the tangible and intangible resources people obtain at the individual, group and organizational levels through social interactions. Social support theory highlights the prosocial facets of human relationships and the support provided by an individual’s social environment. It expands beyond the individuals to their families, and communities, and aims to think of alternative social security-building policies (Chouhy, 2019). People with greater social capital (i.e., resources and benefits gained from relationships, experiences, and social interactions) may be more likely to be prosocial bystanders (Jenkins and Fredrick, 2017). Individuals with higher levels of social support showed more PSB (Gest et al., 2010). Active social support provides a good environment for the practice and development of PSB (De Guzman et al., 2012).

During the pandemic, it was reported that social support was increasing in Chinese adolescents (Kuang et al., 2020; Geng et al., 2022). Moreover, it can positively predict PSB (Kou and Zhang, 2006; Wang, 2011). College students presented with more PSB tendencies though facing the change of learning style and the decrease in interpersonal communication. It is worthwhile to further reveal the role social support plays during the process (Liu et al., 2021).

Herein, the current study assumes that social support can positively predict PSB among Chinese college students during the pandemic. Thus, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 1: Social support can positively predict prosocial behavior among Chinese college students.

The intention of PSB or helping behavior was largely induced in critical situations via internal motivation factors (Zheng et al., 2021). The temporary positive emotional state, positive interpersonal experience (Cirelli et al., 2014; Li et al., 2019) as well as active social support will further promote the underlying process (Eisenberg et al., 2002a).

According to Barbara Fredrickson’s expansion-construction theory (Isgett and Fredrickson, 2015), positive emotion is conducive to expanding the scope of individual attention, cognition and action, and enhancing social flexibility. It will further encourage individuals to actively participate in interpersonal activities, building long-lasting resources (Chen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019) and more likely to show PSB (Fredrickson, 2004). Furthermore, in interpersonal help situations, individuals tended to identify with the just behavior of others (Michie, 2009), and also to follow the role models (Greitemeyer, 2022). Accordingly, public implementation of PSB can enhance well-being (Miles et al., 2021) and promote positive emotion (Varma et al., 2023), even among volunteers (Li, 2020). Though heterogeneous in adult samples, more positive emotion and well-being were reported in college students during COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, it was suggested there is a link between prosocial behaviors and positive emotions (Snippe et al., 2017). From the perspective of pandemic prevention and control, this study will pay more attention to the combined mediating effects of positive emotion, social support, and PSB. It is necessary to further clarify the indirect effect of positive emotion on prosocial behavior tendency. To better understand the possible role that positive emotion plays in the promotion of PSB, we put forward the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Positive affect during COVID-19 would play a mediating role between social support and prosocial behavior.

It has also been proposed that the inheritance of family culture, in particular family education factors, can affect the development of PSB tendency. According to the internalization model, children and adolescents develop expectancies regarding their parents’ reactions to their behaviors. To be specific, positive parenting in the form of parental care and guidance can reinforce parents’ values of care and respect for others (Grusec and Goodnow, 1994) through exemplary role models (Augustine and Stifter, 2015). It also contributes to promoting the development of children’s social abilities (Caplan et al., 2019), greatly affecting the formation of secure attachment (Liu et al., 2009). Mother’s rearing style was revealed to be related to PSB in children. In experimental conditions, improving attachment security can enhance self-transcendence, thus promoting the occurrence of PSB (Wu, 2009). Retrospective studies also pointed out that early attachment security in adolescents can predict PSB during the COVID-19 pandemic (Coulombe and Yates, 2021). Therefore, this study hypothesized that early parental care played a moderating role in positive emotion and PSB during the pandemic.

Hypothesis 3: Parental care may moderate the relationship between positive affect (PA) during COVID-19 and prosocial behavior.

As reviewed above, we constructed a moderated mediation model to examine the medial effect of positive affect (PA) during the COVID-19 pandemic. We further expected the indirect path between social support and prosocial behavior would be moderated by parental care in childhood. The theoretical model was presented in Figure 1.

Credamo is an online professional data platform for research use with over 3 million pooling participants. It has provided research and data services for more than 2,000 universities and scholars around the world (Credamo, 2023). The studies accomplished by using Credamo, have been published in international top journals in the fields of psychology, management, sociology, and public health.

In this online survey, Credamo randomly distributed questionnaires in 29 provinces of China. The survey ran from February 8 to February 16, 2021, 18- to 25-year-old undergraduates were randomly invited to participate in the study. There were 731 responders completed the task. The researcher assured all participants voluntarily involved and their anonymity, confidentiality, and the information every respondent provided was only for study purposes. Screening questions were set up in Credamo in advance to ensure the authenticity of the data. Those who failed the examination questions (e.g., answering the wrong “please choose very satisfied” instruction) and with inconsistent or contradictory answers were rejected. Finally, with 67 participants excluded, the actual number of valid questionnaires was 664. Among those participants, 332 medical students and 332 non-medical students were included. The final sample consisted of 52 freshmen (7.8%), 164 sophomores (24.7%), 204 juniors (30.7%), and 244 seniors (36.75%, 194 in grade 4 and 50 in grade 5), including 247 males (37.2%) and 417 females (62.8%). The participants all had normal visual acuity and no mental illness. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee, Kunming University of Science and Technology (approval number: KMUST-MEC-142).

Social support was assessed by using the Social Support Rate Scale (SSRS; Xiao, 1994). The scale is a self-administered questionnaire originally developed by Chinese scholar. At present, it has been mainly used to measure the social support of the general population, patients and medical staff in Chinese population (He et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2014). The scale consists of three dimensions, including subjective support, objective support and utilization of support. The total score of three dimensions was used to evaluate social support, with a higher score indicating stronger social support. It presented good reliability and validity in Chinese college students (Zhang, 2007). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha value for this overall scale was 0.748. The alpha coefficients for the three subscales were 0.637, 0.510, and 0.586. The reliability and validity were similar to that reported in a recent study among Chinese college students (Lu et al., 2023).

The Prosocial Tendencies Measurement Scale (PTM) was developed by Carlo (Carlo and Randall, 2002). The Chinese version (Kou et al., 2007) was used to assess PSB in the participants. The PTM is a 5-point Likert scale, consisting of 23 items, broadly used in Chinese college students with good reliability and validity (Wang et al., 2021). A higher total score indicated a higher PSB tendency. It was categorized into six dimensions, including openness, anonymity, altruism, compliance, emotion and urgency. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.866 for this overall scale. The alpha coefficients for each dimension were as follows: openness (0.742), anonymity (0.809), altruism (0.578), compliance (0.755), emotion (0.648), and urgency (0.592) in the current study.

The PANAS scale was developed by Watson et al. (1988). The Chinese version (Huang et al., 2003) was developed based on the original one, which consists of 20 items, with each of 10 items evaluating positive and negative effects. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82 for the whole scale, that for Positive Affect and Negative Affect subscale were 0.85 and 0.83, respectively. The Likert 5-point scoring is used to measure the affection during the COVID-19 outbreak for participating college students. Participants rated all items from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very high). The higher the score, the more positive or negative emotions the individual experiences. PANAS was proved to be validated in China during COVID-19 (Tian et al., 2021). For the present study, the Chinese version of the scale was used, employing only the 10 items from the Positive Affect factor. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the sample in this study was 0.892.

PBI is a retrospective self-report questionnaire based on attachment theory developed by Parker (Parker et al., 1979), aiming to measure care and protection for each parent. The Chinese version (Yang et al., 2009) of the scale is composed of two parts, the Mother version (PBI-M) and the Father version (PBI-F) both containing 23 items. There are three subscales for each part, i.e., caring, encouraging autonomy, and control. In this study, the scale was used to measure only the part of the father and mother’s care. The total score of the father and mother’s care was considered as a measurement of parental care. The scale was proved to be of satisfied validities and variabilities and suitable for Chinese undergraduates (Yang et al., 2009). The higher the score, the stronger the subjects’ feeling of family warmth. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for maternal care, paternal care and parental care were 0.798, 0.795, and 0.844.

In the first place, the descriptive information of variables was analyzed, and the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the relationships between these variables. Secondly, the process macro model 4 (a simple mediating model; Hayes, 2013) of SPSS 22.0 was used to test the moderating properties of positive affect (PA) during the COVID-19 outbreak, between social support and prosocial behavior. Next, the process macro model 14 of SPSS was used to investigate the moderating effect of parental care on the mediation effect, that is, whether the prediction of positive emotion on PSB was regulated by parental care. In the model, all continuous variables were normalized to be more comparable. A bootstrap test was conducted and the resultant 95% confidence interval was inspected to determine the significance of the results for mediating and moderating analysis. Confidence intervals without zero indicated significant impact. Additionally, unary linear regression mode was used to further reveal the prediction effect of PSB on PA reversely.

Before the data analysis, we adopted several methods to reduce common method deviations, including anonymity of participants, rearrangement and reverse expression of questions. The Harman one-way factor analysis was used to test for common method biases. There were 20 factors with eigenvalues >1 when unrotated, which explains 62.976% of the variance. The amount of variance explained by the first common factor was 16.951%, less than the critical value of 40%. Thus, no serious common method bias was detected in the current study.

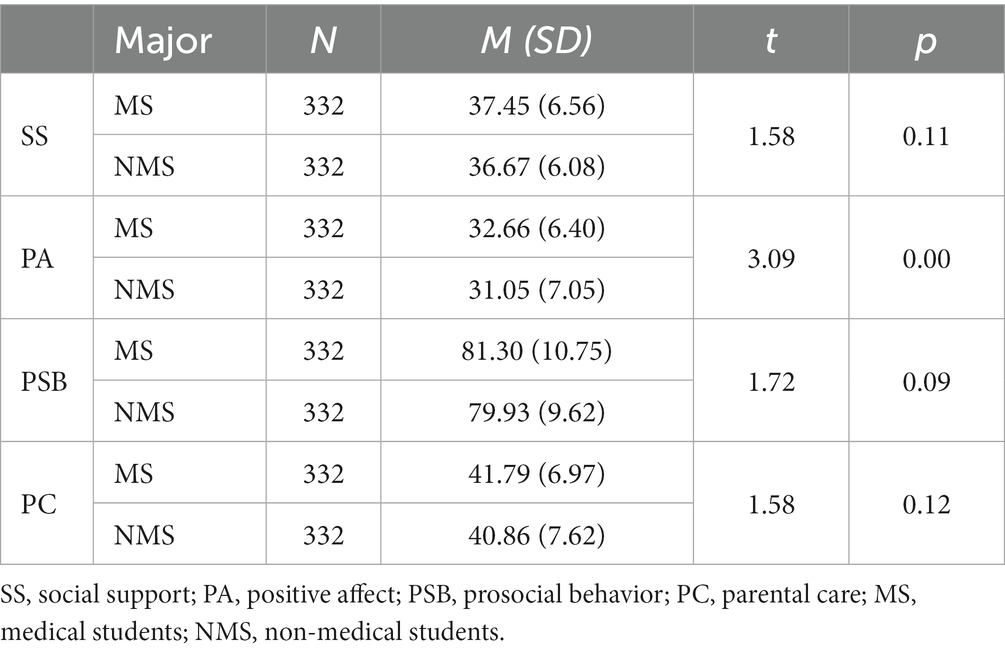

In the current study, medical and nonmedical students were recruited. Descriptive information of the variables according to major was provided in Table 1. The results showed medical students reported a more positive affect (PA) during COVID-19 (t = 3.09, p < 0.01), while no significant difference was observed in social support, PSB and parental care (p > 0.05).

Table 1. Descriptive information of the variables in the medical students and non-medical student groups.

In correlation analysis, positive correlation effects were detected between any two of the variables. To be specific, PSB was positively related to social support (r = 0.38, p < 0.01), positive affect during COVID-19 (r = 0.43, p < 0.01) as well as parental care (r = 0.30, p < 0.01). Moreover, positive affect during COVID-19 was positively related to social support (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) and parental care (r = 0.45, p < 0.01; Table 2).

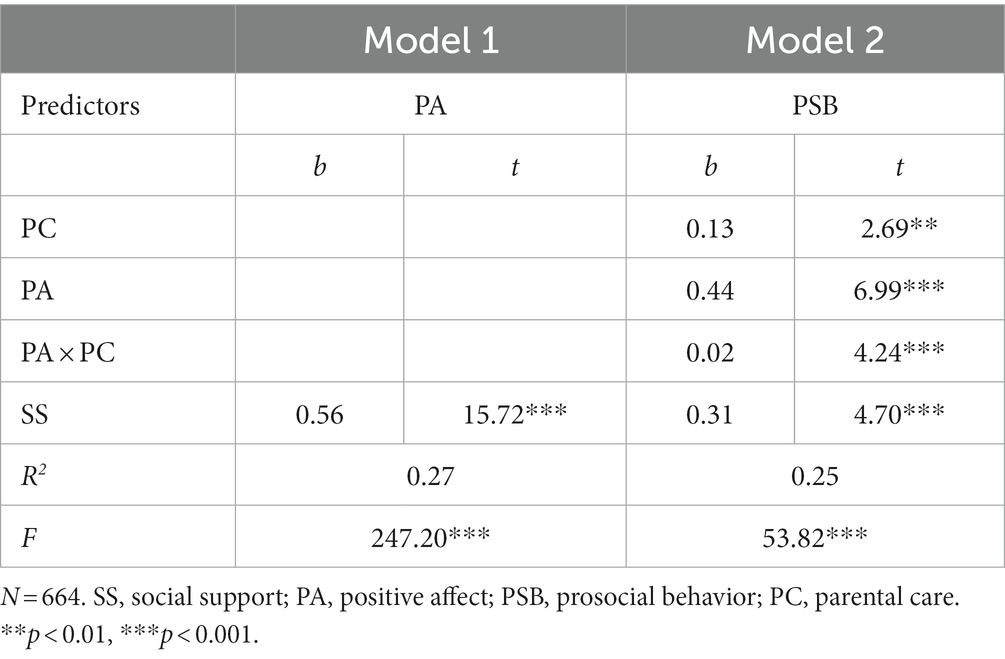

The mediating role of positive affect (PA) in the relationship between social support and PSB was tested by utilizing Model 4 of the PROCESS macro. As shown in Table 3, social support positively predicted PSB (b = 0.62, t = 10.63, p < 0.001). After adding PA as a mediation variable, social support was still a significant predictor of PSB (b = 0.35, t = 5.35, p < 0.001). Moreover, social support positively predicted PA (b = 0.56, t = 15.72, p < 0.001), and positively predicted PSB (b = 0.48, t = 7.93, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the bootstrap test indicated the significant indirect positive (CI = 0.19 to 0.36, effect size = 0.27) in Table 4, the mediation effect accounted for 43.55% of the total effect. Positive affect (PA) partially mediated the relationship between social support and PSB. The reverse was seen in the unary linear regression analysis, PSB also predicted PA during the pandemic of COVID-19 among university students (B = 8.788, SE = 0.286, t = 12.305, β = 0.431, p < 0.01).

To examine whether parental care would moderate the indirect relationship between social support and PSB through positive affect (PA). The PROCESS macro (Model 14) was used to test the moderated mediation mode. In detail, the moderating effect of parental care on the relationship between social support and PSB was estimated (Table 5). Model 2 indicated that there was a significant main effect of positive influence on PSB, b = 0.44, t = 6.99, p < 0.001. The results of the test indicated this was moderated by parental care (b = 0.02, t = 4.24, p < 0.001).

Table 5. Moderated mediation effects of parental care on the relationship between positive affect during COVID-19 and prosocial behavior.

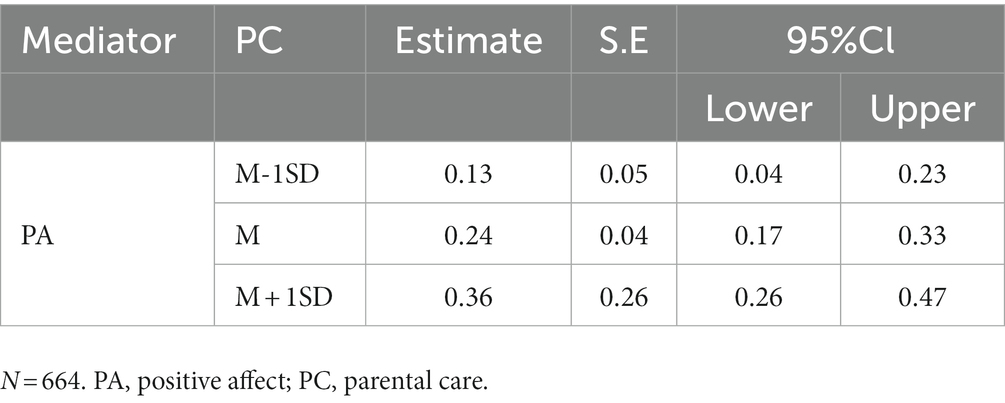

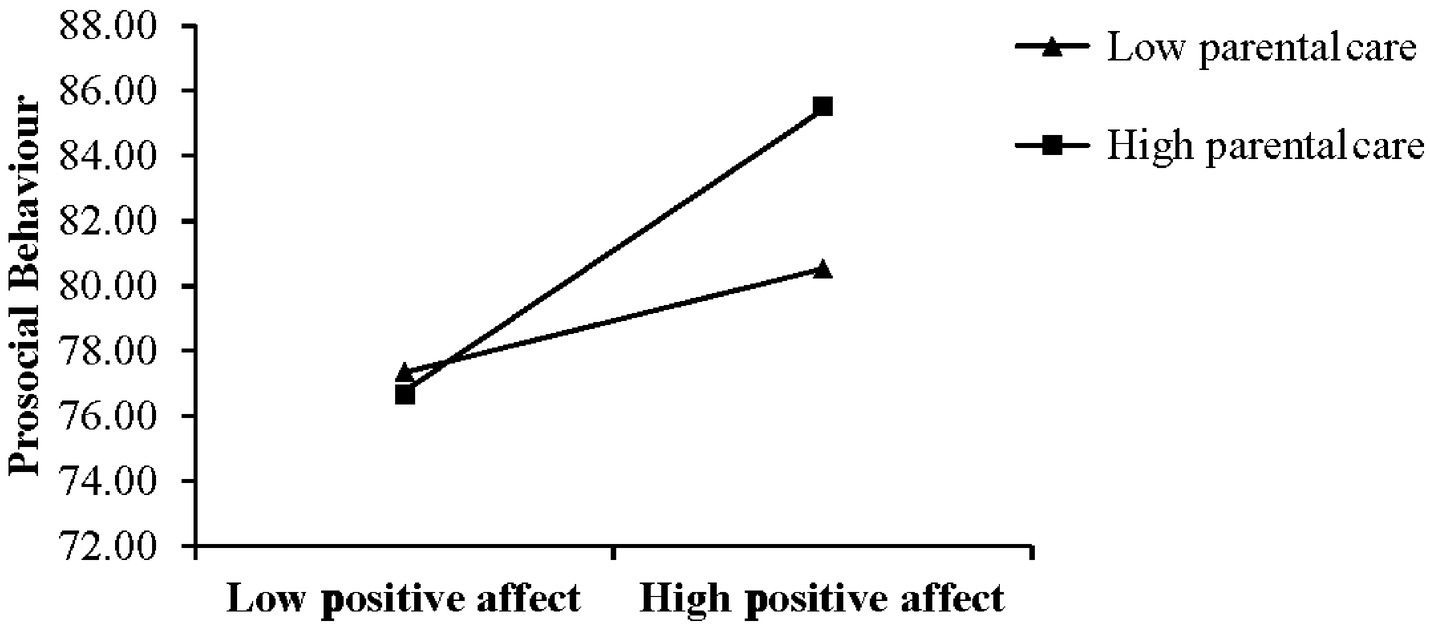

Table 6 shows the results of the bootstrap test, which revealed the conditional indirect effect of parental care. The 95% confidence intervals did not include a 0. In other words, the moderating effect of parental care through PA on PSB differed for individuals who reported low (i.e., M–1SD), average (i.e., mean), and high (i.e., M + 1SD) levels of parental care. Positive affect (PA) could positively predict PSB during the COVID-19 period among individuals with lower parental care (M–1SD, simple slope = 0.24, t = 2.97, p = 0.003). The mediated effect value elevated to 0.3 among individuals with higher parental care (M + 1SD, simple slope = 0. 64, t = 8.18, p < 0.001), indicating an enhanced prediction. The results suggested that, during the COVID-19 outbreak, the prediction effect of positive affect (PA) to PSB increased along with parental care level in childhood (Figure 2).

Table 6. Conditional indirect effect of parental care when positive affect during COVID-19 mediated between social support and prosocial behavior.

Figure 2. Parental care moderated the relationship between positive emotion during COVID-19 and prosocial behavior.

A variety of studies have tried to elaborate on the relationship between social support and PSB. Many of the impact factors were referred. In the current study, positive emotion as a situational (Eisenberg et al., 2002a) element has been verified to cast a mediation effect on the process. The present study further examined the moderating effect of parental care. Results showed that positive emotion during COVID-19 played a mediating role between social support and PSB, and this mediating effect was moderated by parental care in childhood among university students.

First, in line with previous studies on Chinese students, the contribution of social support to PSB (Li, 2010) was observed. In the context of the pandemic, the promotion of PSB may contribute to the setting of prosocial role models through social media (Greitemeyer, 2022), the workshops or open classes of preventative knowledge, as timely social support that strengthened a sense of concern and protection from social communities (Wouter et al., 2018; Kislyakov and Shmeleva, 2021).

According to the buffer model, social support is an effective intervention for individuals to deal with stressful events. Higher levels of social support among college students correlated to a more active, seeking mindset, in dealing with negative emotions (Liu, 2016). Emotion regulation and self-efficacy were improved for individuals where social support is concerned (Zeng and Suqun., 2012). Individuals with higher social support were more likely and tended to get help and guidance in time, also making it possible to resonate with others (Wei, 2020). The occurrence of PSB would be a consequence of improving physical and mental health (Liu et al., 2016).

Consistent with previous studies, and the extended exploration of critical situations, our results suggest that college students with high social support showed a higher tendency to PSB during the pandemic. To summarize, in the critical situations of the pandemic, social support played a positive role in promoting PSB in the buffering of stress (Mcguire et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021), role model demonstration (Feng, 2016), positive publicity (Hu, 2020) and so on.

In the current study, it was demonstrated that positive emotion partially mediates the relationship between social support and PSB during the COVID-19 outbreak. As reviewed above, people are more mindful to pay attention to the needs of others when in a positive emotional state, which also shows PSB in the context of help-seeking (Yu, 2010). The intention of PSB was largely created in critical situations through empathy (Eyal et al., 2018), which was further enhanced in temporary positive emotional states (Eisenberg et al., 2002a). Prosocial behavior is more likely to be aroused by the sharing of success and joy in helping others (Tan et al., 2020). At the same time, social support, as a factor of protection and also acted as a buffer during stress promoting positive emotions (Wang et al., 2022; Jasiński and Derbis, 2023) and subjective well-being (Yıldırım and Celik, 2020), thus possibly elevating the occurrence of PSB (Snippe et al., 2017). Previous studies also reported that the cultivation of PSB in children during the pandemic contributed to the shaping of mental health and resilience (Coyne et al., 2021). The mutual predicting effect between PSB and positive emotion (Snippe et al., 2017) was also detected in the current study. Moreover, medical students reported more positive effects during COVID-19 in the current investigation. This was in line with previous research of medical student volunteers (Zhang et al., 2021) and health workers (Mo et al., 2021). Most students reported being able to maintain a positive mindset during the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhao et al., 2021). However, there was still a transition in the emotional state of volunteers over time (Zhang et al., 2021). A longitudinal design is probably needed to detect the causation of major and emotional states under stress.

In this study, it was observed that parental care casts a positive predictive effect on PSB. The interaction of positive emotion and parental care was also probed, suggesting that the mediating effect of positive emotion on PSB is reinforced by parental care. Previous studies on parental rearing styles and PSB are mostly focused on children, adolescents or young adults (Mestre et al., 2007; Han, 2018). But there are few retrospective studies on the related factors of PSB in critical situations (Petrocchi et al., 2021).

According to the attachment theory, individuals who are safely attached in their early years are more likely to form interpersonal connections (Tuo, 2014). Those children tended to establish interpersonal relationships actively, showed higher social support, and an ease of participation in prosocial activities (Su, 2019; Zhang, 2019). The moderate rearing style plays a positive role in promoting PSB (Mestre et al., 2007). In our study, parental care showed a moderating effect on the process of positive emotion and PSB. The result of the moderated mediation model indicates that more social attention is needed in this population to create more positive emotions, especially during the pandemic. It can be a possible way to promote the occurrence of their prosocial behavior, emphasizing the importance of childhood parental care in individual growth. Changes in the external environment did act as a trigger factor in the process of promoting PSB (Figure 2). In short, parental care in childhood is of vital significance to PSB in critical situations in college students.

To summarize, mainly based on the theory of PSB (Rosser, 1981), broaden-and-build theory (Isgett and Fredrickson, 2015) and attachment theory (Schroeder et al., 1995), this study discussed the mediating effect of social support on PSB. The moderating effect of parental care was also examined. Our results suggest that positive emotions in critical situations play an incomplete intermediary role between social support and PSB. Parental care positively regulates the mediating process. There is an interaction between positive emotion and parental care in childhood, which suggests that parental rearing in early childhood can better promote PSB. It provides new clues to understanding the promotion of PSB and the significance of the process. Namely, strengthening social support in college student is beneficial for promoting prosocial behavior tendency. The temporary positive affect during stress also serves as a target for its mediating role in the procedure. The promotion of PSB can enhance individuals’ positive emotions in turn. Early family education can moderate this mediation process. Therefore, the promotion of PSB may need to be approached from multiple aspects, including current social support, personal emotional state, and early family education, as these efforts reflect the ultimate aim of promoting mental health in adolescent and young adults.

First of all, according to social learning theory, the development of PSB is an interactive process of cognition, behavior and environment. Although a cross-sectional survey was adopted in the present study, the relationship between variables still needs to be observed dynamically. Detection at a single time point is not sufficient to support a comprehensive understanding of the processes. Moreover, in the current study, the measurement of parental care relies on retrospective self-reporting, which may possibly be influenced by inaccurate memory. Finally, although this study discusses the mediating role of positive emotion and parenting, the promoting factors and path between the variables of PSB are still extremely complex and need to be explored more extensively. In addition, we only examined the model in the total sample due to the difference not being significant for each subjective measurement dimension between medical and non-medical students. The impact of majoring in mediating the effect of positive affect is still worth exploring in future studies.

Therefore, a time-event analysis (Ramseyer et al., 2014) is probably needed in the future work. Experimental and longitudinal studies should be included to further investigate the causal relationship of variables. The PSB events also need to be clearly defined and stratified by degree of effort. Prospective study (Malamut et al., 2021) was recommended regarding the interaction between individual, parental rearing, and or social environment (e.g., community/school). The underlying protective and risk factors, as well as resources (Alshehri et al., 2020; Arslan and Yıldırım, 2021a,b; Yıldırım et al., 2022) should be further explored, in order to facilitate the development of more concrete intervention plans.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee, Kunming University of Science and Technology (approval number: KMUST-MEC-142). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

ZH and QG contributed to data collection, data processing, data analysis, statistical analysis, original manuscript drafting, and manuscript editing. ML, YZ, and JG contributed to data collection and data analysis. YF and ZC contributed to project conception, research design, and manuscript revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; Nos. 32060196, 82201597, 31760281, and 81760258), Yunnan Ten Thousand Talents Plan Young and Elite Talents Project (YNWR-QNBJ-2018-027) and YN College Students’ innovation and entrepreneurship training program (S202210674097).

The authors would like to thank Xing Wang for her assistance with the study design and data collection. We thank DG Barns for helpful suggestions on the manuscript proofreading.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alshehri, N., Yıldırım, M., and Vostanis, P. (2020). Saudi adolescents’ reports of the relationship between parental factors, social support and mental health. Arab J. Psychiatry 31, 130–143. doi: 10.12816/0056864

Alvis, L., Douglas, R., Shook, N., and Oosterhoff, B. (2022). Associations between adolescents’ prosocial experiences and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol., 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02670-y

Alzyood, M., Jackson, D., Aveyard, H., and Brooke, J. (2020). COVID-19 reinforces the importance of handwashing. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 2760–2761. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15313

Arslan, G., and Yıldırım, M. (2021a). Perceived risk, positive youth–parent relationships, and internalizing problems in adolescents: initial development of the meaningful school questionnaire. Child Indic. Res. 14, 1911–1929. doi: 10.1007/s12187-021-09841-0

Arslan, G., and Yıldırım, M. (2021b). Psychological maltreatment and loneliness in adolescents: social ostracism and affective experiences. Psychol. Rep. 125, 3028–3048. doi: 10.1177/00332941211040430

Augustine, M. E., and Stifter, C. A. (2015). Temperament, parenting, and moral development: specificity of behavior and context. Soc. Dev. 24, 285–303. doi: 10.1111/sode.12092

Brandenberger, J. (2005). “College, character, and social responsibility: Moral learning through experience,” in Character psychology and character education. eds. D. K. Lapsley and P. F. Clark (Notre dame: University of Notre Dame Press), 305–334.

Caplan, B., Morgan, J. E., Noroña, A. N., Tung, I., Lee, S. S., and Baker, B. L. (2019). The nature and nurture of social development: the role of 5-HTTLPR and gene-parenting interactions. J. Fam. Psychol. 33, 927–937. doi: 10.1037/fam0000572

Carlo, G., Hausmann, A., Christiansen, S., and Randall, B. A. (2003). Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of prosocial tendencies for adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 23, 107–134. doi: 10.1177/0272431602239132

Carlo, G., and Randall, B. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 31, 31–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1014033032440

Chen, S. L., Xu,, and Zheng, X. (2017). Unidimension or dual dimension? An exploration of the construct of positive emotion of well-being. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 25:5. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.01.021

Chen, Y., Yao, S., and Xia, L. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the subjective socioeconomic status scale in a general adult population. Chin. Ment. Health J. 28, 869–874. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2014.11.013

Chen, X., Zou, Y., and Gao, H. (2021). Role of neighborhood social support in stress coping and psychological wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Hubei, China. Healthplace 69:102532. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102532

China Central Television (CCTV) (2021). Chinese story: Oxford sisters against the pandemic. Available at: http://tv.cctv.com/2021/01/09/VIDEB4VZltHzdtRtlMlUDmPY210109.shtml (Accessed April 10, 2023).

Chouhy, C. (2019). “Social support and crime” in Handbook on crime and deviance. eds. M. D. Krohn, N. Hendrix, G. Penly Hall, and A. J. Lizotte (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 213–241.

Cirelli, L., Einarson, K., and Trainor, L. (2014). Interpersonal synchrony increases prosocial behavior in infants. Dev. Sci. 17, 1003–1011. doi: 10.1111/desc.12193

Coulombe, B., and Yates, T. (2021). Attachment security predicts adolescents’ prosocial and health protective responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Dev. 93, 58–71. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13639

Coyne, L. W., Gould, E. R., Grimaldi, M., Wilson, K. G., Baffuto, G., and Biglan, A. (2021). First things first: parent psychological flexibility and self-compassion during COVID-19. Behav. Anal. Pract. 14, 1092–1098. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00435-w

Credamo (2023). Credamo: Professional Survey & Experiment Tool [Online]. Available at: https://www.credamo.world/#/ (Accessed 2023).

Crick, N. R., and Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in Children’s social adjustment. PsyB 115, 74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74

De Guzman, M. R., Jung, E., and Do, K.-A. (2012). Perceived social support networks and prosocial outcomes among Latino/a youth in the United States. Int. J. Psychol. 46, 413–424. doi: 10.30849/rip/ijp.v46i3.303

Deng, Z., and Chen, Q. (2022). What is suitable social distancing for people wearing face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic? Indoor Air 32:e12935. doi: 10.1111/ina.12935

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, A. R., Guthrie, K. I., and Reiser, M. (2002a). “The role of emotionality and regulation in children's social competence and adjustment” in Paths to successful development: Personality in the life course. eds. L. Pulkkinen and A. Caspi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 46–70.

Eisenberg, N., Guthrie, I., Cumberland, A., Murphy, B., Shepard, S., Zhou, Q., et al. (2002b). Prosocial development in early adulthood: a longitudinal study. JPSP 82, 993–1006. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.993

Eyal, T., Steffel, M., and Epley, N. (2018). Perspective mistaking: accurately understanding the mind of another requires getting perspective, not taking perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 114, 547–571. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000115

Feng, Z. (2016). The priming effect of moral model on modern college students’ prosocial behavior. Doctorial Dissertation. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 359, 1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

Gallaway, M., Rigler, J., Robinson, S., Herrick, K., Livar, E., Komatsu, K., et al. (2020). Trends in COVID-19 incidence after implementation of mitigation measures – Arizona, January 22-August 7, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 69, 1460–1463. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e3

Gan, L., and Zuo, B. (2006). Motivation theory of prosocial behavior. J. Harbin Univ. 27, 17–21. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5856.2006.12.005

Geng, Y., Cheung, S., Huang, C., and Liao, J. (2022). Volunteering among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 19:5154. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095154

Gest, S. D., Graham-Bermann, S. A., and Hartup, W. W. (2010). Peer experience: common and unique features of number of friendships, social network centrality, and sociometric status. Soc. Dev. 10, 23–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00146

Greitemeyer, T. (2022). Prosocial modeling: person role models and the media. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.024

Grusec, J. E., and Goodnow, J. J. (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child’s internalization of values: a reconceptualization of current points of view. DP 30, 4–19. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4

Han, C. (2018). The effects of parental rearing styles on college students’ prosocial behaviors: the mediating role of aggression. Adv. Soc. Sci. 7, 252–259. doi: 10.12677/ASS.2018.73042

Han, Q., Zheng, B., Cristea, M., Agostini, M., Bélanger, J., Gützkow, B., et al. (2023). Trust in government regarding COVID-19 and its associations with preventive health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the pandemic: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychol. Med. 53, 149–159. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001306

Hardy, S. A., and Carlo, G. (2005). Religiosity and prosocial behaviours in adolescence: the mediating role of prosocial values. J. Moral Educ. 34, 231–249. doi: 10.1080/03057240500127210

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

He, X., Xiao, S., and Zhang, D. (2008). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of geriatric depression scale: a study in a population of Chinese rural community-dwelling elderly. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 16:473.

Helena, K. S., and Bernardes, N. (1997). Desenvolvimento moral pró-social: Semelhanças e diferenças entre os modelos teóricos de Eisenberg e Kohlberg. Estud. Psicol. 2, 223–262.

Howard, J., Huang, A., and Li, Z. (2021). An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118:e2014564118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014564118

Hu, D. (2020). Empathy communication: public opinion guidance for public emergencies. Ningbo Econ. 6, 20–23.

Huang, L. Y., Tingzhong,, and Ji, Z. (2003). Applicability of the positive and negative affect scale in Chinese. Chin. Ment. Health J. 17, 54–56. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2003.01.018

Isgett, S. F., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). “Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). ed. J. D. Wright (Oxford: Elsevier), 864–869.

Jasiński, A. M., and Derbis, R. (2023). Social support at work and job satisfaction among midwives: the mediating role of positive affect and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 79, 149–160. doi: 10.1111/jan.15462

Jenkins, L. N., and Fredrick, S. S. (2017). Social capital and bystander behavior in bullying: internalizing problems as a barrier to prosocial intervention. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 757–771. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0637-0

Kislyakov, P. A., and Shmeleva, E. A. (2021). Strategies of prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Open Psychol. J. 14, 266–272. doi: 10.2174/1874350102114010266

Kou, Y., Hong, H., Tan, C. L., and Lei, (2007). Revisioning prosocial tendencies measure for adolescent. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 23, 112–117. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4918.2007.01.020

Kou, Y., and Tang, L. (2004). A survey of studies on the relationship between moods and prosocial behaviors. J. Beijing Normal Univ. 2004, 44–49. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0209.2004.05.007

Kou, Y., and Zhang, Q. (2006). Conceptual representation of early adolescent’ prosocial behavior. Soc. Stud. 21, 169–187.

Kuang, J., Lu, A., Yin, X., and Sun, X. (2020). The relationship between coping style and social support of college student during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychologies 15, 60–61. doi: 10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2020.20.022

Li, C. (2010). The study on the relations between the social support to poor students in universities and prosocial behaviours-based on the investigation of the poor students of the two universities in Hu'nan and Guizhou. J. Hebei Univ. Sci. Technol. 10, 90–95. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-1653.2010.02.017

Li, H. (2020). Research on the role of voluntary service activities in improving college students’ mental health from the perspective of positive psychology. Archive 13:262.

Li, W., Guo, F., and Chen, Z. (2019). The effect of social support on adolescents’ prosocial behavior: a serial mediation model. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 4, 817–821. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.04.037

Liu, L. (2016). On the relationship among shyness, perceived social support and regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Adv. Psychol. 06, 275–280. doi: 10.12677/AP.2016.63036

Liu, A., Wang, W., and Wu, X. (2021). Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth mediate the relations between social support, prosocial behavior, and antisocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 12:1864949. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1864949

Liu, Q., Xu, Q., Liu, H., and Liu, Q. (2016). The relationship between online social support and online altruistic behavior of college students: a moderated mediating model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 32, 426–434. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2016.04.06

Liu, Q., Zhou, S., Yang, H., Chu, Y., and Liu, L. (2009). Adolescent’s adult attachment and its relationship with parenting styles. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 17, 615–616.

Lu, X., Zhang, M., and Zhang, J. (2023). The relationship between social support and internet addiction among Chinese college freshmen: a mediated moderation model. Front. Psychol. 13:1031566. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1031566

Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Pastorelli, C., Zuffianò, A., Eisenberg, N., Ceravolo, R., and Caprara, G. V. (2014). Trajectories of prosocial behaviors conducive to civic outcomes during the transition to adulthood: the predictive role of family dynamics. J. Adolesc. 37, 1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.002

Malamut, S. T., Van Den Berg, Y. H. M., Lansu, T. A. M., and Cillessen, A. H. N. (2021). Bidirectional associations between popularity, popularity goal, and aggression, alcohol use and Prosocial behaviors in adolescence: a 3-year prospective longitudinal study. J. Youth Adolesc. 50, 298–313. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01308-9

Mcguire, A. P., Hayden, C., Frankfurt, S. B., Kurz, A. S., Anderson, A. R., Howard, B., et al. (2020). Social engagement early in the U.S. COVID-19 crisis: exploring social support and prosocial behavior between those with and without depression or anxiety in an online sample. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 39, 923–953. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2020.39.10.923

Mestre, V., Tur-Porcar, A., Samper, P., Nácher, M. J., and Cortés, M. (2007). Rearing styles in adolescence: their relation with prosocial behavior. Rev. Latinoamericana de Psicol. 39, 211–225.

Michie, S. (2009). Pride and gratitude: how positive emotions influence the prosocial behaviors of organizational leaders. J. Leadership Organ. Stud. 15, 393–403. doi: 10.1177/1548051809333338

Miles, A., Andiappan, M., Upenieks, L., and Orfanidis, C. (2021). Using prosocial behavior to safeguard mental health and foster emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a registered report protocol for a randomized trial. PLoS One 16:e0245865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245865

Mo, T., Layous, K., Zhou, X., and Sedikides, C. (2021). Distressed but happy: health workers and volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cult. Brain 10, 27–42. doi: 10.1007/s40167-021-00100-1

Parker, G., Tupling, H., and Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 52, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x

Petrocchi, S., Bernardi, S., Malacrida, R., Traber, R., Gabutti, L., and Grignoli, N. (2021). Affective empathy predicts self-isolation behaviour acceptance during coronavirus risk exposure. Sci. Rep. 11:10153. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89504-w

Ramseyer, F., Kupper, Z., Caspar, F., Znoj, H., and Tschacher, W. (2014). Time-series panel analysis (TSPA): multivariate modeling of temporal associations in psychotherapy process. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 828–838. doi: 10.1037/a0037168

Reiman, A.J. (2009). Conditions for promoting moral and prosocial development in schools. Springer Boston, MA.

Rosser, R. A. (1981). “Social learning theory and the development of prosocial behavior: a system for research integration,” in Parent-child interaction: theory, research, and prospects. ed. R. W. Henderson (New York: Academic Press), 59–81.

Rotenberg, K. J., Fox, C., Green, S., Ruderman, L., Slater, K., Stevens, K., et al. (2005). Construction and validation of a children's interpersonal trust belief scale. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 23, 271–293. doi: 10.1348/026151005X26192

Schroeder, A.D., Penner, A.L., Dovidio, F.J., and Piliavin, A.J. (1995). The psychology of helping and altruism: problems and puzzles. New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, Inc.

Snippe, E., Jeronimus, B., Rot, M., Bos, E., Jonge, P., and Wichers, M. (2017). The reciprocity of prosocial behavior and positive affect in daily life. J. Pers. 86, 139–146. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12299

Son, D., and Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2020). Happy helpers: a multidimensional and mixed-method approach to prosocial behavior and its effects on friendship quality, mental health, and well-being during adolescence. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 1705–1723. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00154-2

Su, L. (2019). Early socialization of children's emotions. Chinese J. Child Health Care 27, 929–931. doi: 10.11852/zgetbjzz2019-0177

Sweijen, S. W., Groep, S. V. D., Green, K., Brinke, L. T., and Crone, E. A. (2022). Daily prosocial actions during the COVID-19 pandemic contribute to giving behavior in adolescence. Sci. Rep. 12:7458. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11421-3

Tan, J., Yan, L.L., and Pedraza-Martinez, A. (2020). "How to share prosocial behavior without being considered a braggart?", in: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, Hawaii, USA.

Tang, S., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., and Xiang, Y. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: the importance of parent-child discussion. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

Tian, F., Yu, W., Wang, S., Huang, Q., Peng, H., Li, L., et al. (2021). Application of simplified cognitive behavioral therapy to emergency psychological stress response in the new crown pneumonia epidemic. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 29, 701–705. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2021.05.013

Tuo, R. (2014). The influence of safe attachment on interpersonal trust. Master’s Dissertation. Xi'an: Shaanxi Normal University.

Varma, M. M., Chen, D., Lin, X., Aknin, L. B., and Hu, X. (2023). Prosocial behavior promotes positive emotion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emotion 23, 538–553. doi: 10.1037/emo0001077

Wang, X., Luo, R., Guo, P., Shang, M., Zheng, J., Cai, Y., et al. (2022). Positive affect moderates the influence of perceived stress on the mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 19:13600. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013600

Wang, H. (2011). Relationship between network of social support and prosocial behavior among vocational students. Chin. J. Public Health 27, 700–702. doi: 10.11847/zgggws2011-27-06-12

Wang, H., Wu, S., Wang, W., and Wei, C. (2021). Emotional intelligence and prosocial behavior in college students: a moderated mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:713227. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713227

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. JPSP 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wei, W. (2020). The relationship between social support and emotion of community personnel during post-epidemic period: mediating effect and intervention of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Master’s Dissertation. Chongqing: Southwest University.

Winer, A.C. (2013). Are prosocial children also compliant children? Individual differences in and maternal influences on early sociomoral development. Dissertations & Theses – Gradworks.

Word Health Organization (2020). Listings of WHO’s response to COVID-19. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (Accessed April 10, 2023).

Wouter, V., Crone, E. A., Rosa, M., Berna, G., and Giovanni, P. (2018). Social network cohesion in school classes promotes prosocial behavior. PLoS One 13:e0194656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194656

Wu, H. (2009). A study on the relationship between mother's rearing style, mother-child attachment and kindergarten adaptation in junior class. Marster’s Dissertation. Beijing: Capital Normal University.

Xiao, S. (1994). Theoretical basis and application in research of social support rating scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 4, 98–100.

Yang, X., Gao, L., Zhang, S., Zhang, L., and Zhou, S. (2020). Psychological status and its relationship with social support in college students during COVID-19 epidemic. J. Psychiatry 33, 241–246. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-9346.2020.04.001

Yang, J., Yu, J., Kou, Y., and Fu, X. (2015). Intervention on peer relationship promoting middle school students’ prosocial behavior. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 31:7. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.02.14

Yang, H. J., Zhou, S. J., Chu, Y. M., Li, L., and Liu, Q. (2009). The revision of parental bonding instrument for Chinese college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 4, 434–436.

Yıldırım, M., Ağış, Z. G., Batra, K., Ferrari, G., Kizilgeçit, M., Chirico, F., et al. (2022). Role of resilience in psychological adjustment and satisfaction with life among undergraduate students in Turkey: a cross-sectional study. J. Health Soc. Sci. 7, 224–235. doi: 10.19204/2022/RLFR8

Yıldırım, M., and Celik, F. (2020). Social support, resilience and subjective well-being in college students. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 5, 127–135. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v5i2.229

Zeng, D. L., and Suqun, (2012). Effect of social support on the regulatory emotional self-efficacy in the patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. China Medical Herald 9, 126–128. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7210.2012.24.054

Zhang, J. R. (2007). The correlation between social support, coping style and subjective well-being of college students. Chin. J. Clin. Psych. 15, 629–631. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3611.2007.06.025

Zhang, Q. (2017). Grow with community: how to improve adolescents’ prosocial behavior. Beijing: China Social Sciences Publishing House.

Zhang, L. (2019). The relationship between parental rearing style, emotional regulation and prosocial behavior of preschool children. Master’s Dissertation. Jinan: Shandong Normal University.

Zhang, K., Peng, Y., Zhang, X., and Li, L. (2021). Psychological burden and experiences following exposure to COVID-19: a qualitative and quantitative study of Chinese medical student volunteers. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 18:4089. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084089

Zhao, H., Xiong, J., Zhang, Z., and Qi, C. (2021). Growth mindset and college students’ learning engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: a serial mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12:621094. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621094

Keywords: social support, prosocial behavior, moderated mediation model, parental care, COVID-19

Citation: Huang Z, Gan Q, Luo M, Zhang Y, Ge J, Fu Y and Chen Z (2023) Social support and prosocial behavior in Chinese college students during the COVID-19 outbreak: a moderated mediation model of positive affect and parental care. Front. Psychol. 14:1127194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1127194

Received: 19 December 2022; Accepted: 18 April 2023;

Published: 10 May 2023.

Edited by:

Murat Yildirim, Ağrı İbrahim Çeçen University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Gözde Ersöz, Fenerbahçe University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2023 Huang, Gan, Luo, Zhang, Ge, Fu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhuangfei Chen, Y2hlbi56aGZAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.