- 1Fondazione Patrizio Paoletti, Assisi, Italy

- 2Research Institute for Neuroscience Education and Didactics, Fondazione Patrizio Paoletti, Assisi, Italy

- 3Department of Philosophy, Sociology, Pedagogy, and Applied Psychology, University of Padua, Padua, Italy

Since February 2022, 7.8 million people have left Ukraine. In total, 80% are women and children. The present quali-quantitative study is the first in Italy to (i) describe the adaptation challenges and the resources of refugee parents and, indirectly, of their children and (ii) investigate the impact of neuropsychopedagogical training on their wellbeing. The sample includes N = 15 Ukrainian parents (80% mothers, mean age = 34 years) who arrived in Italy in March and April 2022. The parents participated in neuropsychopedagogical training within the program Envisioning the Future (EF): the 10 Keys to Resilience. Before the training, participants completed an ad hoc checklist to detect adjustment difficulties. After the training, they responded to a three-item post-training questionnaire on the course and to a semi-structured interview deepening adaptation problems, personal resources, and the neuropsychopedagogical training effects. Participants report that since they departed from Ukraine, they have experienced sleep, mood, and concentration problems, and specific fears, which they also observed in their children. They report self-efficacy, self-esteem, social support, spirituality, and common humanity as their principal resources. As effects of the training, they report an increased sense of security, quality of sleep, and more frequent positive thoughts. The interviews also reveal a 3-fold positive effect of the training (e.g., behavioral, emotional-relational, and cognitive-narrative).

1. Introduction

According to the United Nation Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2022) report—updated on 23 November 2022—since 24 February 2022, more than 7.84 million Ukrainians (a quarter of the country's total population) have fled their homes in the face of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and sought refuge in Europe. An estimated 40% are children (Save the Children, 2022). According to the scientific literature, refugee children and adolescents may develop post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression symptoms, mainly related to the protracted sense of threat to their safety (Bronstein and Montgomery, 2011). As with natural disasters and other widespread socio-political conflicts around the world (Fazel and Stein, 2002; Taylor and Sidhu, 2012; Cai et al., 2022; Tandon et al., 2022), the conflict between Russia and Ukraine can threaten the mental health of refugee children and adolescents.

In families fleeing war, special attention must also be paid to parents. Higher levels of anxiety and psychological distress in parents predict internalizing and externalizing behaviors in their children, as shown in a study of refugees from Eritrea (Betancourt et al., 2012a) and Colombia (Flink et al., 2013). A study by Hosin et al. (2006), on refugees from Iraq, reported that children of refugee parents may also show lower adaptation skills. Conversely, having parents who can offer care, listening, and respect is a predictor of lower levels of anxiety in refugee children from Chechnya (Betancourt et al., 2012b). Similarly, a study of Syrian refugee children revealed that a family climate that encourages emotional expression decreases the risk of developing PTSD symptoms (Khamis, 2019).

It has been underlined by ethnographic research that resilience is a key resource for parents who are going through alone such a severe situation (Lenette et al., 2013). In such a population, resilience should be fostered through specific educational programs (Paoletti et al., 2022a). These activities allow the individuals to be fortified by trauma and adversity, turning challenging events into opportunities to improve oneself in the present and future (Grotberg, 1995), including the experience of parenting. Specifically, in response to humanitarian crises, programs that integrate combined complementary approaches (Kalmanowitz and Ho, 2016) can facilitate improvements in refugees' quality of life (Chung and Hunt, 2016) by reducing negative symptoms of stress, intrusive thoughts, and sleep disturbances (Rees et al., 2014) and helping them to view adversity situations with a more positive mindset (Goehring, 2018).

Refugee parents, who are subjected to high levels of stress, may be compromised in their ability to care for their children. Therefore, their children's health must also be implemented and protected by, in turn, promoting the health of their caregivers (Riber, 2017; Buchmüller et al., 2018; Scharpf et al., 2021) and implementing their overall wellbeing, as individuals and as parents, under adversity.

In consideration of the premises highlighted in the literature, it is a priority to monitor the health and coping strategies of refugee parents in the host country and implement interventions that are helpful to increase the level of wellbeing in these populations.

2. Study aims

The aims of this research note were two-fold: (i) to describe both the adaptation challenges faced by Ukrainian parents, and indirectly by their children, and the main personal resources they have put in place since their arrival in the host country; (ii) to investigate the impact of neuropsychopedagogical training on the wellbeing of Ukrainian parents and the indirect impact on their children.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Procedure

Neuropsychopedagogical training based on the program “The 10 Keys to Resilience” (Paoletti et al., 2022b) took place in the context of an educational campus targeting Ukrainian families fleeing war, held from 13 June to 22 July 2022, organized by Fondazione Patrizio Paoletti (FPP) with the support of Assisi International School (AIS). The program has been applied in several emergency settings, in Italy, as part of the multi-year Envisioning the Future (EF) project (Di Giuseppe et al., 2022, 2023; Maculan et al., 2022; Paoletti et al., 2022b). The goal of EF is to provide individuals and communities with an educational pathway to strengthen the resilience and resources of people engaged in the care of children and adolescents. The educational intervention and related research were conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Padua (Protocol No. 0003662). At the campus, the educational materials used were translated into Ukrainian.

The theoretical-practical framework of the program “The 10 Keys to Resilience” is based on the Sphere Model of Consciousness (Paoletti and Ben-Soussan, 2019; Pintimalli et al., 2020) and Pedagogy for the Third Millennium (Paoletti, 2008), developed by the FPP interdisciplinary team, which includes guidance based on neuropsychopedagogical knowledge and techniques for coping with stress and difficulties. The program has been successfully implemented among educators in the juvenile penal circuit (Paoletti et al., 2022c, 2023), among inmates during the COVID-19 pandemic (Di Giuseppe et al., 2022), and among earthquake survivor communities (Di Giuseppe et al., 2023). The “10 keys to resilience” are as follows: (1) restart from what you can control and make small decisions; (2) identify an attainable, challenging, and measurable goal; (3) several times a day become aware of your posture; (4) be inspired by the others stories; (5) ask yourself what is really important; (6) cultivate gratitude; (7) experience the other as a resource, cultivate and expand your social network; (8) cultivate curiosity; (9) practice a few minutes of silence; (10) embrace and transform: before going to sleep, generate today your own tomorrow (for more information, see Paoletti et al., 2022a,b).

The program provided for Ukrainian parents to benefit from the blended training (e.g., online and in-person activities) “The 10 Keys to Resilience,” through 14 meetings (average duration of 2.5 h), with simultaneous translation and training materials provided in both Italian and Ukrainian. The presence of a cultural mediator of Ukrainian nationality was provided both in the design and creation phase of the content and in its fruition, ensuring not only translation but also a relational link between teachers and participants.

The program included two intervention focuses: self-focused, for the development of parental resilience and positive resources, and child-focused, for the strengthening of parenting skills during adversity.

3.2. Participants

In total, 15 Ukrainian parents (mean age = 34 years, 80% mothers), who were subject to informed consent, took part in the study. They arrived in Italy (Umbria), with their children, through the support of Ukrainian relatives, friends, and acquaintances, already residing in Italy. The latter created on their own initiative communities of welcome and support for their refugee compatriots (providing them with accommodation, food, and the possibility of temporary job placement). The participants, welcomed by these spontaneous communities, reported leaving Ukraine 20% in April and 80% in March 2022. Most of the refugee participants were from the city of Kyiv (46%), with the remainder coming from Ivano-Frankivsk (27%), Kharkiv (7%), Irpin (7%), Smila (7%), and Dnipro (6%). A total of 53% were mothers who reported being in Italy without the child's other parent.

3.3. Measures

The measures were created ad hoc following the principles of psychology research methods (Kazdin, 2013). Pre-training, participants completed an ad hoc self-administered checklist on their own and their children's biopsychosocial health status. The checklist allows them to report dichotomously (e.g., by answering yes or no to each item) on the occurrence, since leaving Ukraine, of problems related to adaptation (e.g., lack of attention, negative mood, specific fears, irritability, physical symptoms, appetite-related difficulties, sleep-related difficulties, and, in children, also difficulties in relating to peers and playing).

Post-training, an ad hoc questionnaire was also administered: it consisted of three items related to the program experience on “The 10 Keys to Resilience,” which investigated dichotomously (with yes or no answer options) improvements with respect to the participant's sleep quality, increase in positive thoughts, and increased perception of safety.

In addition, post-training, participants also responded to individual semi-structured interviews, conducted by a psychologist, about issues of adaptation, major difficulties since arrival in Italy, and the impact of the training. The interviews were conducted in the presence of a cultural mediator of Ukrainian nationality, in line with the literature that posits the mediator as an active participant in the interview and not just a translator (Raga et al., 2020), capable of creating a link between the interviewer and the interviewee.

3.4. Data analysis

To investigate the defined aims, two studies were implemented. The first one aimed at a quali-quantitative analysis of the main personal resources and adjustment challenges of Ukrainian parents, and—indirectly—the difficulties of their children. For this purpose, descriptive statistics were performed on the data from the ad hoc self-administered checklist and bottom-up text analysis on the verbatim transcripts of the semi-structured interviews, with subsequent categorization.

The second study aimed at a quali-quantitative assessment of the impact of “The 10 Keys to Resilience” training on Ukrainian parents. For this purpose, descriptive statistics were performed on the responses to ad hoc post-training dichotomous items. To understand the effect of the training, according to the two lines of intervention (self-focused and child-focused), the transcripts of the interviews were analyzed in a bottom-up approach, extracting the main categories.

For the categories that emerged in the two studies, the analysis of the interviews involved the statistical calculation of the inter-rater agreement between two different evaluators using Cohen's K. The evaluators were to score the relevance of the extracts related to each category on a scale from 0 = not relevant to 3 = totally relevant.

4. Results

4.1. Study 1: Adjustment problems and personal resources

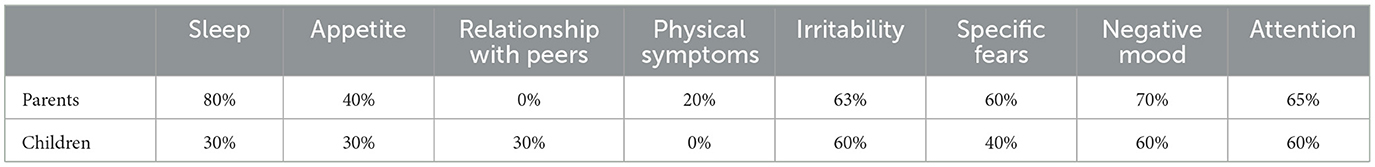

Most parents report that in recent months, they are experiencing sleep-related difficulties (80%), negative mood (70%), lack of attention and concentration difficulties (60%), specific fears (60%), and irritability (63%) (Table 1). Similarly, they report that their children are experiencing mostly problems related to attention (60%), mood (60%), irritability (60%), and specific fears (40%) (Table 1).

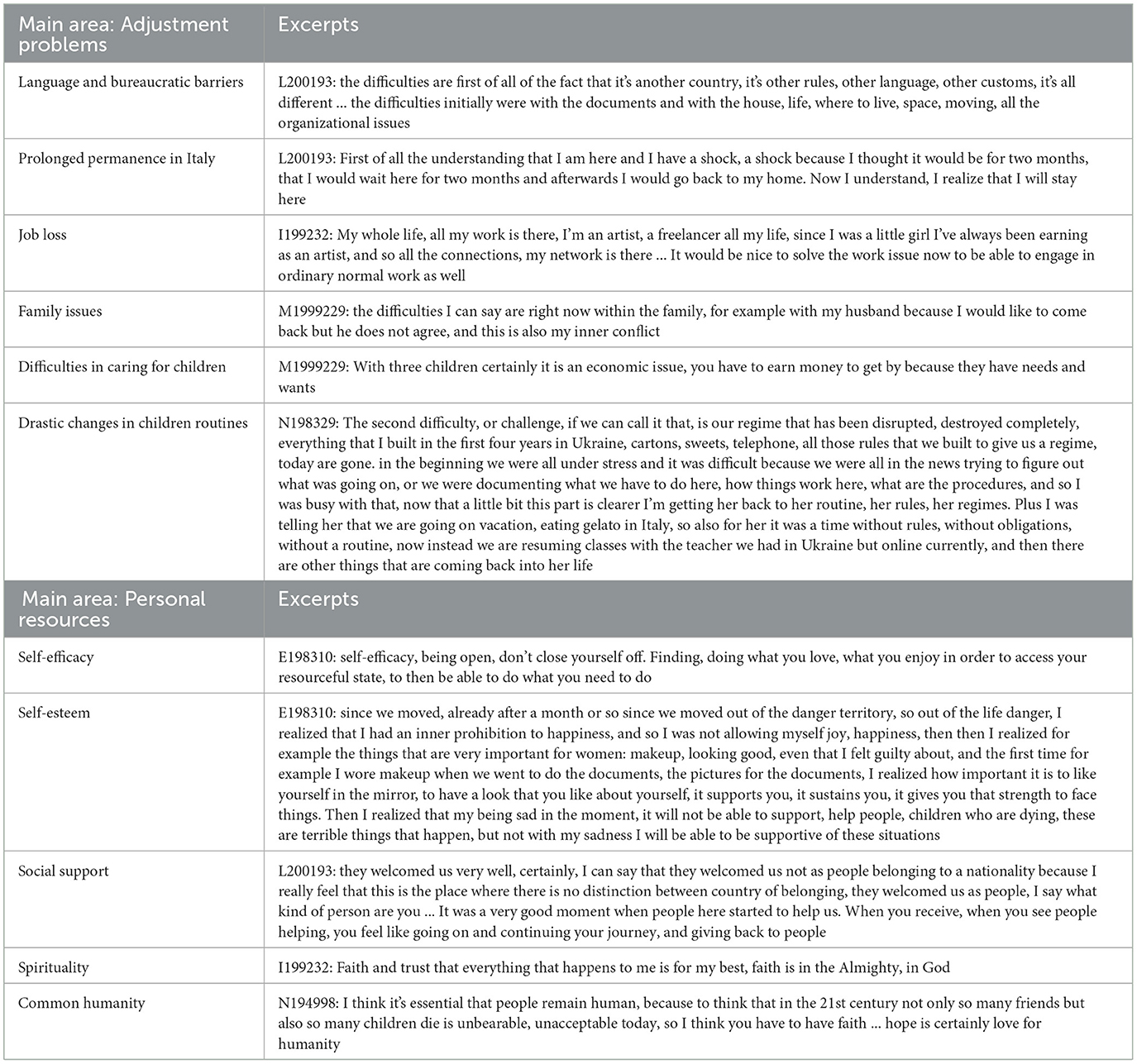

Parents' main adjustment problems, as revealed by the analysis of the semi-structured interviews (Table 2), appeared to be related to the language and bureaucratic barrier (40%), prolonged permanence in Italy (13%), job loss (13%), and family issues (6%). Difficulties in caring for children (20%) and, for the latter, drastic changes in their routines (6%) also emerged (Table 2). At the same time, the main resources deployed by parents appear to be self-efficacy (26%), perceived social support (66%), spirituality (6%), common humanity (13%), and self-esteem (13%). The inter-rater agreement appears to be high (Cohen's K = 0.88).

Table 2. Excerpts of the main areas related to adjustment problems and personal resources of Ukrainian parents (N = 15).

4.2. Study 2: The impact of the “10 Keys to Resilience” program

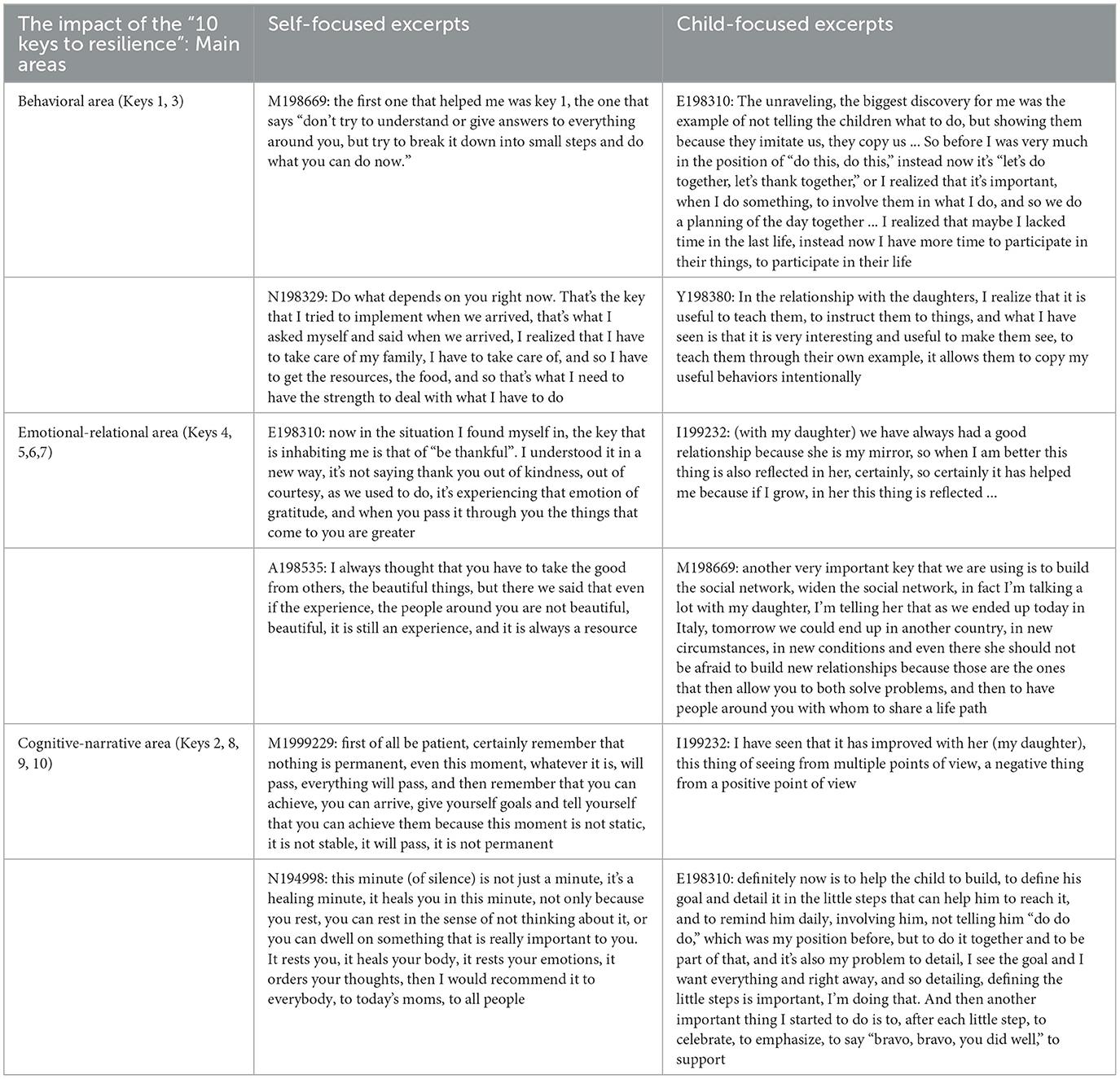

According to the statistical-descriptive results, on the post-training questionnaire, Ukrainian parents report that they perceived improved sleep (80%), increased confidence (86%), and more frequent positive thoughts (86%) after the training on the “10 Keys to Resilience.” The impact of the training was further explored by text analysis of the interview excerpts (Table 3).

Table 3. Excerpts from the interviews with Ukrainian parents participating in the intervention (N = 15).

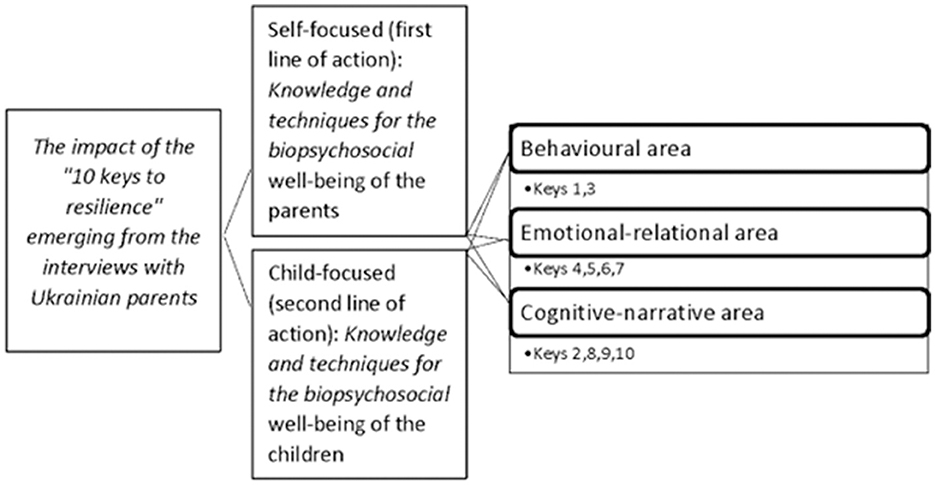

Ukrainian parents reported that the “The 10 Keys to Resilience” training provided them with theoretical-practical instruments, to be used for their own (self-focused line of intervention) and children's (child-focused line of intervention) wellbeing, concerning three specific areas (Figure 1): (i) behavioral (keys 1 and 3); (ii) emotional-relational (keys 4, 5, 6, and 7); (iii) cognitive-narrative (keys 2, 8, 9, and 10). The inter-rater agreement is found to be high (Cohen's K = 0.88).

Figure 1. Impact of the “10 Keys to Resilience” emerging from the interviews with Ukrainian parents.

5. Discussion

5.1. Ukrainian refugee parents in Italy: Principal features

5.1.1. Adaptation challenges

Study 1 results show that Ukrainian refugee parents experience mood-related problems and irritability. This finding is in line with recent studies investigating both migration flows caused by wars and the COVID-19 pandemic reactions, showing the prevalence of emotional dysregulation, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress in individuals, across different nations and socio-political conditions (Henkelmann et al., 2020; Turliuc and Candel, 2022). In addition, they report sleep problems related to both migration stress and broader post-traumatic symptomatology (Richter et al., 2020). These elements may also cause the lack of concentration that the participants' report (Kaplan, 2009) and the experience of specific fears and phobias (Thapa et al., 2003; Betancourt et al., 2017).

Regarding the issues parents report in their children, the literature highlights a higher incidence of PTSD among refugee children and adolescents than among adults (Henkelmann et al., 2020): a statistical comparison was not performed in this study, but issues of irritability and negative mood in children are defined as salient by their parents. Similarly, adults report a lack of concentration in children that could be due to the effects of trauma, with a possible negative impact on cognitive development and learning abilities (Beers and De Bellis, 2002; Kaplan et al., 2016). Finally, specific phobias and fears may emerge in the child subjected to traumatic situations (e.g., detachment from one of the parents, from one's routine, from one's home, and from one's parental and friendship circle), as witnessed by the parents, which may negatively influence development (Javanbakht et al., 2021).

The adaptation difficulties that emerged from the semi-structured interviews concern multiple topics: forced migration, language and bureaucratic difficulties, sense of uncertainty, unemployment, and taking care of the children. First, the dramatic circumstances in the participants' home country lead them to a forced migration where the destination country was not chosen (Becker, 2022). Language difficulties amplify the sense of alienation in the new context, and language constitutes a barrier to the fulfillment of bureaucratic matters (Gerlach and Ryndzak, 2022), undermining the individual's sense of autonomy as well as their perceived ability to manage their family. Other sources of concern include the sense of uncertainty about the future provoked by the ongoing war in Ukraine (Mohamed and Thomas, 2017; Becker, 2022) and the unemployment status which can predict depression among refugees (Beiser et al., 1993). Adaptation difficulties are also reported in the management of children: refugee parents are worried about their mental and physical health status (Javanbakht, 2022), given the disruption of their before-war routines.

5.1.2. Adaptive resources

In Study 1, five adaptive resources emerged from the semi-structured interviews of Ukrainian refugee parents: self-efficacy, social support, spirituality, sense of common humanity, and self-esteem. Being a refugee could decrease individual empowerment (Bowie et al., 2017). However, among the resources deployed by parents, self-efficacy appears to strengthen coping by supporting them in raising children (Slagt et al., 2012; Vintilă and Istrat, 2014). More specifically, self-efficacy predicts greater relational involvement (Shumow and Lomax, 2002) and greater support and ability to maintain general wellbeing (i.e., their own and the children) (Deković et al., 2010; Goian, 2014; Kalaitzaki et al., 2022), factors associated with positive adaptation (Meunier and Roskam, 2009).

Another key resource is the perceived social support both externally and within the refugee community. This finding is in line with previous research highlighting the importance of social support in decreasing the risk of PTSD and increasing adaptation among Sudanese refugees in Australia (Schweitzer et al., 2006) and Afghans in Canada (Ahmad et al., 2020). Specifically, a study by Stewart et al. (2017), on refugee parents from Sudan and Zimbabwe in Canada, reports that social support is perceived as higher if it comes both from the refugee community and from professionals who are sensitive to cultural differences issues. An additional resource mentioned by Ukrainian parents is spirituality, consistent with evidence on spirituality as a coping resource associated with greater hope and optimism in refugees (Ai et al., 2003), especially among refugee parents (El-Khani et al., 2017).

Participants refer to perceive a sense of closeness with other human beings. This data could be interpreted in light of Neff (2011) “Common Humanity,” a subdimension of self-compassion, which describes the sense of feeling as a part of humanity. Finally, perceiving intact self-esteem is mentioned by the refugee parents as a basic element for psychological wellbeing (Neff, 2011).

5.1.3. The impact of the neuropsychopedagogical training

In Study 2, participants responses to the post-training questionnaire reveal an improvement in sleep after the training. In this sense, the intervention may be a protective factor against the chronicization of sleep disorders, which can remain in refugees long-term after the traumatic events, with negative consequences for individual health (Basishvili et al., 2012; Richter et al., 2020). The responses to the questionnaire, “The 10 Keys to Resilience” within the EF program, appear to increase the frequency of positive thoughts, in line with the outcomes of positive psychology interventions on refugees (Kubitary and Alsaleh, 2018; Foka et al., 2021), to facilitate post-traumatic growth through hope (Umer and Elliot, 2021). Parents report that EF increased their sense of security, comforting them about their newfound safety but also about the possibility of constituting, in attachment terms, a secure base for themselves and their children (Dalgaard et al., 2016). Moreover, by helping parents to focus on their own positive resources, the intervention could have played an important role to prevent the feeling of “subjective incompetence” in stressful situations, described in the literature as demoralization (Costanza et al., 2022a).

Extracts from the participants' interviews describe the positive impact of the training on the behavioral, emotional-relational, and cognitive-narrative areas, highlighting the importance of providing the Ukrainian population with psychological support tools (Costanza et al., 2022b).

As regard the behavioral area, the training encouraged participants to perceive themselves as active subjects, who can exert control over their environment. Having a greater sense of control promotes safety and a reduction in anxiety and negative emotions (Gallagher et al., 2014). Participants refer an increase in wellbeing and coping through small actions. This data also reflects the importance for parents of being an example for their children and engaging them in practical actions to build together new reassuring routines, able to mitigate uncertainty. As reported in the literature, in times of severe crisis, being able to decide which simple and regular activities to be engaged in is fundamental. This allows persons to reinforce the perception of a safe and stable surrounding (Nelson and Shankman, 2011; Bentley et al., 2013), as experienced by the refugee parents through EF.

Regarding the emotional-relational area, refugee parents felt gratitude, an emotional state associated with wellbeing, in a relationship mediated by perceived social support (Lin, 2016). Social support is a key resource for refugees' mental health and resilience (Schweitzer et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2017; Sim et al., 2019; Ahmad et al., 2020) and a positive coping strategy (El-Khani et al., 2017). Perceiving higher social support may lead individuals to want to show reciprocity and be helpful to others in turn (Schmitt, 2021) as emerged in the interviews.

Finally, the intervention seems to have had an impact on the cognitive-narrative area. The use of cognitive strategies, such as problem-solving, planning, and positive reappraisal, helps cope with stressors (Feder et al., 2009) and makes it possible to experience a minor impact of war-related trauma and life changes related to refugee status (Fino et al., 2020). The practice of silence-based meditation (Paoletti, 2018), suggested in the program, also impacts the cognitive-narrative area, and it is described by the participants as a powerful tool for activating a re-narration of experiences through self-talk, in the form of a “silent narrative” (Morin, 2009; Kross et al., 2014). The practice of silence-based meditation is mentioned as a healing experience, in line with studies on the therapeutic effect of meditative practices on refugees (Hinton et al., 2013; Kalmanowitz and Ho, 2016), and as a restful experience, promoting mental functioning and reducing alertness and stress symptoms (Rees et al., 2014).

6. Limitations and future directions

The first limitation of the present research is the small sample size, which does not allow result generalization. However, sample size standards in qualitative research are linked to historical and cultural factors related to the target sample (Marshall et al., 2013). The second limitation is the use of the semi-structured interview, even in the presence of a cultural mediator, that could generate social desirability bias in refugee samples (Da Silva Rebelo et al., 2022).

Notwithstanding these limitations, this is the first study in Italy to investigate the adaptation problems and challenges of Ukrainian parents and at the same time the effects of neuropsychopedagogical training on their wellbeing. The study lays the foundation for subsequent investigations into the biopsychosocial health of Ukrainian refugees, especially concerning the experience of parenting and interventions aimed at supporting them. It is suggested for future studies in the field to implement a multidisciplinary approach that integrates clinical and socio-educational interventions, which should be longitudinally evaluated.

7. Conclusion

The present findings describe the complexity of the experience of Ukrainian refugee parents, who arrived in Italy between March and April 2022. The quantitative analysis highlights the negative impact of refugee status on the wellbeing of Ukrainian parents. However, attention is also paid to the positive resources emerging from the qualitative analysis of their interviews. It is precisely this aspect that the EF training sought to enhance to support Ukrainian refugee parents. The training allowed the refugee parents not only to improve their coping strategies but also to renew their awareness of their role as a parent, guiding their children in times of complexity. The interviews' extracts highlight their role, not only as protectors and caregivers of their children but also as active educators promoting their mental and emotional wellbeing.

The research is the first neuropsychopedagogical experience, in Italy, to apply a specific theoretical and methodological framework to safeguard the wellbeing of Ukrainian refugees, educating primary educators (e.g., parents) in the functioning of the resilient mind and transmitting usable long-term techniques (e.g., the practice of silence). The interdisciplinary approach recalls the importance of monitoring the wellbeing of refugees—adults and, indirectly, children. The study highlights the timeliness of intervening to transform the traumatic experience into a source of resources to face the present and future.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Padua (Protocol No. 0003662). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PP, TD, CL, and GP contributed to the design and implementation of the research. GP, CL, and GS analyzed quantitative and qualitative data. GS, AM, and FV helped with the references. PP structured the theoretical framework as the developer of the Sphere Model of Consciousness and Pedagogy for the Third Millennium. GP, LC, and TD drafted the manuscript. TD integrated and coordinated the study. All authors provided substantial contributions to the study, critically revised the manuscript, approved this version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this study and its integrity.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help from Elena Perolfi as director of the training project, Luca Cerrao as coordinator of the project, Oleksandra Lomaka as a translator and cultural mediator, Barbara Piva as the school management of Assisi International School (AIS), and Patrizia Siena for transcribing the interviews.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, F., Othman, N., and Lou, W. (2020). Posttraumatic stress disorder, social support and coping among Afghan refugees in Canada. Commun. Ment. Health J. 56, 597–605. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00518-1

Ai, A. L., Peterson, C., and Huang, B. (2003). The effect of religious-spiritual coping on positive attitudes of adult Muslim refugees from Kosovo and Bosnia. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 13, 29–47. doi: 10.1207/S15327582IJPR1301_04

Basishvili, T., Eliozishvili, M., Maisuradze, L., Lortkipanidze, N., Nachkebia, N., Oniani, T., et al. (2012). Insomnia in a displaced population is related to war-associated remembered stress. Stress Health 28, 186–192. doi: 10.1002/smi.1421

Becker, S. (2022). “Lessons from history for our response to Ukrainian refugees,” in Global Economic Consequences of the War in Ukraine Sanctions, Supply Chains and Sustainability, eds L. Garicano, D. Rohner, B. Weder Di Mauro (London: CEPR Press).

Beers, S. R., and De Bellis, M. D. (2002). Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 483–486. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.483

Beiser, M., Johnson, P. J., and Turner, R. J. (1993). Unemployment, underemployment and depressive affect among Southeast Asian refugees. Psychol. Med. 23, 731–743. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700025502

Bentley, K. H., Gallagher, M. W., Boswell, J. F., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., Woods, S. W., et al. (2013). The interactive contributions of perceived control and anxiety sensitivity in panic disorder: A triple vulnerabilities perspective. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 35, 57–64. doi: 10.1007/s10862-012-9311-8

Betancourt, T. S., Newnham, E. A., Birman, D., Lee, R., Ellis, B. H., and Layne, C. M. (2017). Comparing trauma exposure, mental health needs, and service utilization across clinical samples of refugee, immigrant, and US-origin children. J. Trauma. Stress 30, 209–218. doi: 10.1002/jts.22186

Betancourt, T. S., Salhi, C., Buka, S., Leaning, J., Dunn, G., and Earls, F. (2012a). Connectedness, social support and internalising emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents displaced by the Chechen conflict. Disasters 36, 635–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2012.01280.x

Betancourt, T. S., Yudron, M., Wheaton, W., and Smith-Fawzi, M. C. (2012b). Caregiver and adolescent mental health in Ethiopian Kunama refugees participating in an emergency education program. J. Adolesc. Health 51, 357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.001

Bowie, B. H., Wojnar, D., and Isaak, A. (2017). Somali families' experiences of parenting in the United States. West. J. Nurs. Res. 39, 273–289. doi: 10.1177/0193945916656147

Bronstein, I., and Montgomery, P. (2011). Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 14, 44–56. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0081-0

Buchmüller, T., Lembcke, H., Busch, J., Kumsta, R., and Leyendecker, B. (2018). Exploring mental health status and syndrome patterns among young refugee children in Germany. Front. Psychiatry 9, 212. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00212

Cai, H., Bai, W., Zheng, Y., Zhang, L., Cheung, T., Su, Z., et al. (2022). International collaboration for addressing mental health crisis among child and adolescent refugees during the Russia-Ukraine war. Asian J. Psychiatr. 72, 103109. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103109

Chung, S. C., and Hunt, J. (2016). Meditation in humanitarian aid: an action research. Lancet 388, S36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32272-3

Costanza, A., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A., Magnani, L., Huguelet, P., Serafini, G., et al. (2022b). Meaning-centered therapy in Ukraine's war refugees: an attempt to cope with the absurd? Front. Psychol. 13, 1067191. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1067191

Costanza, A., Vasileios, C., Ambrosetti, J., Shah, S., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A., et al. (2022a). Demoralization in suicide: a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 157, 110788. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110788

Da Silva Rebelo, M. J., Fernández, M., and Meneses-Falcón, C. (2022). Chewing revenge or becoming socially desirable? Anger rumination in refugees and immigrants experiencing racial hostility: Latin-Americans in Spain. Behav. Sci. 12, 180. doi: 10.3390/bs12060180

Dalgaard, N. T., Todd, B. K., Daniel, S. I., and Montgomery, E. (2016). The transmission of trauma in refugee families: associations between intra-family trauma communication style, children's attachment security and psychosocial adjustment. Attachm. Human Dev. 18, 69–89. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1113305

Deković, M., Asscher, J. J., Hermanns, J., Reitz, E., Prinzie, P., and van den Akker, A. L. (2010). Tracing changes in families who participated in the Home-Start parenting program: parental sense of competence as mechanism of change. Prev. Sci. 11, 263–274. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0166-5

Di Giuseppe, T., Perasso, G., Mazzeo, C., Maculan, A., Vianello, F., and Paoletti, P. (2022). Envisioning the future: a neuropsycho-pedagogical intervention on resilience predictors among inmates during the pandemic. Ricerche Psicol. Open Access. doi: 10.3280/rip2022oa14724. [Epub ahead of print].

Di Giuseppe, T., Serantoni, G., Paoletti, P., and Perasso, G. (2023, April). Un sondaggio a quattro anni da Prefigurare il Futuro, un intervento neuropsicopedagogico postsisma [A survey four years after Envisioning the Future, a post-earthquake neuropsychopedagogic intervention]. Orientamenti Pedagogici, Ed. Erikson.

El-Khani, A., Ulph, F., Peters, S., and Calam, R. (2017). Syria: coping mechanisms utilised by displaced refugee parents caring for their children in pre-resettlement contexts. Intervention 15, 34–50. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000136

Fazel, M., and Stein, A. (2002). The mental health of refugee children. Arch. Dis. Childhood 87, 366–370. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.5.366

Feder, A., Nestler, E. J., and Charney, D. S. (2009). Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 446–457. doi: 10.1038/nrn2649

Fino, E., Mema, D., and Russo, P. M. (2020). War trauma exposed refugees and posttraumatic stress disorder: the moderating role of trait resilience. J. Psychosom. Res. 129, 109905. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109905

Flink, I. J., Restrepo, M. H., Blanco, D. P., Ortegon, M. M., Enriquez, C. L., Beirens, T. M., et al. (2013). Mental health of internally displaced preschool children: a cross-sectional study conducted in Bogotá, Colombia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 48, 917–926. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0611-9

Foka, S., Hadfield, K., Pluess, M., and Mareschal, I. (2021). Promoting well-being in refugee children: an exploratory controlled trial of a positive psychology intervention delivered in Greek refugee camps. Dev. Psychopathol. 33, 87–95. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419001585

Gallagher, M. W., Bentley, K. H., and Barlow, D. H. (2014). Perceived control and vulnerability to anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cogn. Therap. Res. 38, 571–584. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9624-x

Gerlach, I., and Ryndzak, O. (2022). Ukrainian migration crisis caused by the war. Stud. Eur. Affairs 26, 17–29. doi: 10.33067/SE.2.2022.2

Goehring, K. (2018). Stop, Meditate, and Listen: A Treatment Modality for Iraqi Refugees with depression. Doctor of Nursing Practice Final Manuscripts. 67. Available online at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/dnp/67

Goian, C. (2014). Transnational wellbeing analysis of the needs of professionals and learners engaged in adult education. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 142, 380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.695

Grotberg, E. H. (1995). A Guide to Promoting Resilience in Children: Strengthening the Human Spirit (Vol. 8). The Hague, Netherlands: Bernard van leer foundation.

Henkelmann, J. R., de Best, S., Deckers, C., Jensen, K., Shahab, M., Elzinga, B., et al. (2020). Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees resettling in high-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 6, 54. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.54

Hinton, D. E., Pich, V., Hofmann, S. G., and Otto, M. W. (2013). Acceptance and mindfulness techniques as applied to refugee and ethnic minority populations with PTSD: examples from” Culturally Adapted CBT”. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 20, 33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.09.001

Hosin, A. A., Moore, S., and Gaitanou, C. (2006). The relationship between psychological well-being and adjustment of both parents and children of exiled and traumatized Iraqi refugees. J. Muslim Mental Health 1, 123–136. doi: 10.1080/15564900600980616

Javanbakht, A. (2022). Addressing war trauma in Ukrainian refugees before it is too late. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 13, 2104009. doi: 10.1080/20008066.2022.2104009

Javanbakht, A., Stenson, A., Nugent, N., Smith, A., Rosenberg, D., and Jovanovic, T. (2021). Biological and environmental factors affecting risk and resilience among Syrian refugee children. J. Psychiatry Brain Sci. 6, e210003. doi: 10.20900/jpbs.20210003

Kalaitzaki, A., Tamiolaki, A., and Tsouvelas, G. (2022). From secondary traumatic stress to vicarious posttraumatic growth amid COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: the role of health care workers' coping strategies. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 14, 273. doi: 10.1037/tra0001078

Kalmanowitz, D., and Ho, R. T. (2016). Out of our mind. Art therapy and mindfulness with refugees, political violence and trauma. Arts Psychother. 49, 57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.012

Kaplan, I. (2009). Effects of trauma and the refugee experience on psychological assessment processes and interpretation. Aust. Psychol. 44, 6–15. doi: 10.1080/00050060802575715

Kaplan, I., Stolk, Y., Valibhoy, M., Tucker, A., and Baker, J. (2016). Cognitive assessment of refugee children: effects of trauma and new language acquisition. Transcult. Psychiatry 53, 81–109. doi: 10.1177/1363461515612933

Khamis, V. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation among Syrian refugee children and adolescents resettled in Lebanon and Jordan. Child Abuse Neglect. 89, 29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.013

Kross, E., Bruehlman-Senecal, E., Park, J., Burson, A., Dougherty, A., Shablack, H., et al. (2014). Self-talk as a regulatory mechanism: how you do it matters. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106, 304. doi: 10.1037/a0035173

Kubitary, A., and Alsaleh, M. A. (2018). War experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder, sleep disorders: clinical effectiveness of treatment by repeating phrases of positive thoughts (TRPPT) of mental-war disorders in Syrian refugees children and adolescents war victims—a new therapeutic trial. Sleep Hypnosis 20, 210–226. doi: 10.5350/Sleep.Hypn.2017.19.0153

Lenette, C., Brough, M., and Cox, L. (2013). Everyday resilience: narratives of single refugee women with children. Qual. Social Work 12, 637–653. doi: 10.1177/1473325012449684

Lin, C. C. (2016). The roles of social support and coping style in the relationship between gratitude and well-being. Pers. Individ. Dif. 89, 13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.032

Maculan, A., Di Giuseppe, T., Vianello, F., and Vivaldi, S. (2022). Narrazioni e risorse. Gli operatori del sistema penale minorile al tempo del covid-19. Auton. locali Serv. Soc. 2, 349–365.

Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., and Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 54, 11–22. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

Meunier, J. C., and Roskam, I. (2009). Self-efficacy beliefs amongst parents of young children: validation of a self-report measure. J. Child Fam. Stud. 18, 495–511.doi: 10.1177/0165025410382950

Mohamed, S., and Thomas, M. (2017). The mental health and psychological well-being of refugee children and young people: an exploration of risk, resilience and protective factors. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 33, 249–263. doi: 10.1080/02667363.2017.1300769

Morin, A. (2009). Self-awareness deficits following loss of inner speech: Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor's case study. Conscious. Cogn. 18, 524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.09.008

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 5, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Nelson, B. D., and Shankman, S. A. (2011). Does intolerance of uncertainty predict anticipatory startle responses to uncertain threat? Int. J. Psychophysiol. 81, 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.05.003

Paoletti, P., and Ben-Soussan, T. D. (2019). The sphere model of consciousness: from geometrical to neuro-psycho-educational perspectives. Log. Univ. 13, 395–415. doi: 10.1007/s11787-019-00226-0

Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Anella, S., and Santinelli, A. (2022b). Le Dieci Chiavi della Resilienza. Available online at: https://fondazionepatriziopaoletti.org/10-chiavi-resilienza/ (accessed December 10, 2022).

Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Ben-Soussan, T. D., Bozkurt, A., Tabibnia, G., et al. (2022a). What can we learn from the COVID-19 pandemic? Resilience for the future and neuropsychopedagogical insights. Front. Psychol. 5403, 993991. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.993991

Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Serantoni, G., Perasso, G., Maculan, A., et al. (2022c). La resilienza nel circuito penale minorile in tempi di pandemia: un'esperienza di studio e formazione basata sul modello sferico della coscienza su un gruppo di educatori. Narrare i gruppi, pagine-01.

Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Serantoni, G., Perasso, G., Maculan, A., et al. (2023). Training spherical resilience in educators of the juvenile justice system during pandemic. World Futures 2023, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/02604027.2023.2169569

Pintimalli, A., Di Giuseppe, T., Serantoni, G., Glicksohn, J., and Ben-Soussan, T. D. (2020). Dynamics of the sphere model of consciousness: silence, space, and self. Front. Psychol. 11, 2327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.548813

Raga, G. F., Sales Salvador, D., and Sánchez Pérez, M. (2020). Interlinguistic and intercultural mediation in psychological care interviews with asylum seekers and refugees: handling emotions in the narration of traumatic experience. Cultus 13, 94–122.

Rees, B., Travis, F., Shapiro, D., and Chant, R. (2014). Significant reductions in posttraumatic stress symptoms in Congolese refugees within 10 days of transcendental meditation practice. J. Trauma. Stress 27, 112–115. doi: 10.1002/jts.21883

Riber, K. (2017). Trauma complexity and child abuse: a qualitative study of attachment narratives in adult refugees with PTSD. Transcult. Psychiatry 54, 840–886. doi: 10.1177/1363461517737198

Richter, K., Baumgärtner, L., Niklewski, G., Peter, L., Köck, M., Kellner, S., et al. (2020). Sleep disorders in migrants and refugees: a systematic review with implications for personalized medical approach. EPMA J. 11, 251–260. doi: 10.1007/s13167-020-00205-2

Save the Children (2022). This is My Life, and I Don't Want to Waste a Year of It: The Experiences and Wellbeing of Children Fleeing Ukraine. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/poland/my-life-and-i-dont-want-waste-year-it-experiences-and-wellbeing-children-fleeing-ukraine-november-2022#:~:text=Since%20the%20escalation%20of%20conflict,An%20estimated%2040%25%20are%20children (accessed November 25, 2022).

Scharpf, F., Mkinga, G., Neuner, F., Machumu, M., and Hecker, T. (2021). Fuel to the fire: The escalating interplay of attachment and maltreatment in the transgenerational transmission of psychopathology in families living in refugee camps. Dev. Psychopathol. 33, 1308–1321. doi: 10.1017/S0954579420000516

Schmitt, C. (2021). ‘I want to give something back': social support and reciprocity in the lives of young refugees. Refuge Can. J. Refugees 37, 3–12. doi: 10.25071/1920-7336.40690

Schweitzer, R., Melville, F., Steel, Z., and Lacherez, P. (2006). Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Austral. NZ J. Psychiatry 40, 179–187. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x

Shumow, L., and Lomax, R. (2002). Parental efficacy: predictor of parenting behavior and adolescent outcomes. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2, 127–150. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0202_03

Sim, A., Bowes, L., and Gardner, F. (2019). The promotive effects of social support for parental resilience in a refugee context: a cross-sectional study with Syrian mothers in Lebanon. Prev. Sci. 20, 674–683. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-0983-0

Slagt, M., Deković, M., de Haan, A. D., van den Akker, A. L., and Prinzie, P. (2012). Longitudinal associations between mothers' and fathers' sense of competence and children's externalizing problems: the mediating role of parenting. Dev. Psychol. 48, 1554–1562. doi: 10.1037/a0027719

Stewart, M., Kushner, K. E., Dennis, C., Kariwo, M., Letourneau, N., Makumbe, K., et al. (2017). Social support needs of Sudanese and Zimbabwean refugee new parents in Canada. Int. J. Migrat. Health Social Care 13, 234–252. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-07-2014-0028

Tandon, S., D'Souza, A., Favari, E., and Siddharth, K. (2022). Consequences of Forced Displacement in Active Conflict: Evidence from the Republic of Yemen. Policy Research Working Paper: 10176. World Bank, Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/38021 (accessed December 10, 2022).

Taylor, S., and Sidhu, R. K. (2012). Supporting refugee students in schools: what constitutes inclusive education? Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 16, 39–56. doi: 10.1080/13603110903560085

Thapa, S. B., Van Ommeren, M., Sharma, B., de Jong, J. T., and Hauff, E. (2003). Psychiatric disability among tortured Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. Am. J. Psychiatry 160, 2032–2037. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.2032

Turliuc, M. N., and Candel, O. S. (2022). The relationship between psychological capital and mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: a longitudinal mediation model. J. Health Psychol. 27, 1913–1925. doi: 10.1177/13591053211012771

Umer, M., and Elliot, D. L. (2021). Being hopeful: Exploring the dynamics of post-traumatic growth and hope in refugees. J. Refug. Stud. 34, 953–975. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fez002

United Nation Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2022). Situation Report, 23rd November 2022. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/ukraine-situation-report-16-nov-2022-enruuk (accessed November 25, 2022).

Keywords: refugees, neuropsychopedagogical training, parents, resilience, positive resources, Ukraine, asylum seekers, war

Citation: Paoletti P, Perasso GF, Lillo C, Serantoni G, Maculan A, Vianello F and Di Giuseppe T (2023) Envisioning the future for families running away from war: Challenges and resources of Ukrainian parents in Italy. Front. Psychol. 14:1122264. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1122264

Received: 12 December 2022; Accepted: 13 February 2023;

Published: 15 March 2023.

Edited by:

Mona Vintilă, West University of Timişoara, RomaniaReviewed by:

Otilia I. Tudorel, West University of Timişoara, RomaniaRosella Tomassoni, University of Cassino, Italy

Alessandra Costanza, University of Geneva, Switzerland

Copyright © 2023 Paoletti, Perasso, Lillo, Serantoni, Maculan, Vianello and Di Giuseppe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giulia Federica Perasso, Zy5wZXJhc3NvQGZvbmRhemlvbmVwYXRyaXppb3Bhb2xldHRpLm9yZw==

Patrizio Paoletti1

Patrizio Paoletti1 Giulia Federica Perasso

Giulia Federica Perasso Grazia Serantoni

Grazia Serantoni Tania Di Giuseppe

Tania Di Giuseppe