95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 09 February 2023

Sec. Health Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1092725

This article is part of the Research Topic Psychosocial and Bioethical Challenges and Developments for The Future of Vascularized Composite Allotransplantations View all 11 articles

Nikolas R. Hummel1

Nikolas R. Hummel1 Kevin J. Zuo2

Kevin J. Zuo2 Simon Talbot3

Simon Talbot3 Zoe E. Zimmerman3

Zoe E. Zimmerman3 Jeffrey N. Katz4

Jeffrey N. Katz4 Sarah E. Kinsley3

Sarah E. Kinsley3 Martin Kumnig1*

Martin Kumnig1*Background: The impact of patient-specific psychosocial factors on functional outcomes after upper-extremity (UE) vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) is poorly understood. The objective of this study was to identify relevant psychosocial predictors for success or failure of UE VCA in an Austrian cohort.

Methods: A qualitative study was undertaken consisting of semi-structured interviews with UE VCA staff, transplanted patients, and close relatives. Participants were asked about their perceptions of factors that either favored or hindered a successful transplant outcome, including functional status before surgery, preparation for transplant, decision-making, rehabilitation and functional outcome after surgery, and family and social support. Interviews were conducted online and recorded with the consent of interviewees.

Results: Four bilateral UE VCA patients, 7 healthcare professionals, and a sister of a patient participated in the study. Thematic analysis revealed the importance of an expert interdisciplinary team with adequate resources for patient selection. Psychosocial aspects of prospective candidates are crucial to evaluate as they contribute to success. Both patients and providers may be impacted by public perceptions of UE VCA. Functional outcomes are optimized with a life-long commitment to rehabilitation as well as close, ongoing provider involvement.

Conclusion: Psychosocial factors are important elements in the assessment and follow-up care for UE VCA. To best capture psychosocial elements of care, protocols must be individualized, patient-centered, and interdisciplinary. Investigating psychosocial predictors and collecting outcomes is, thus, critical to justifying UE VCA as a medical intervention and to providing accurate and salient information to prospective candidates.

The primary goal of upper-extremity vascularized composite allotransplantation (UE VCA) is to maximize transplant recipients’ functional, emotional, and social quality of life (QoL). Outcomes are much broader than graft survival, range of motion, and other traditional objective endpoints. Accordingly, while immunological, biomechanical, and medical factors are important determinants of transplant outcomes, psychosocial factors also play critical roles. Due to the small number of performed UE VCA cases and the heterogeneous screening and follow-up protocols, few studies of psychosocial predictors of outcomes have been performed worldwide; hence, our understanding of this topic is limited (Kumnig et al., 2012, 2013; Singh et al., 2015, 2016; Jowsey-Gregoire et al., 2016; Heineman et al., 2020; Bound Alberti et al., 2022; Kumnig et al., 2022), although, several transplant centers worldwide have developed specific VCA programs (Kumnig et al., 2013). Recent research (e.g., Heineman et al., 2020; Kinsley et al., 2022) provides a good understanding of functional and sensory, and psychosocial outcomes (Kumnig et al., 2014). Additionally, comprehensive qualitative research initiatives have recently been undertaken to enhance psychosocial outcomes in VCA and discuss the key psychosocial challenges faced in UE VCA today.

As noted above, UE VCA is life enhancing rather than life saving such as in the case in solid organ transplantation (SOT; Dickenson, 1999; Dubernard, 2011). Hence, the risk-to-benefit ratio is quite different than with SOT in which the risks are offset by the lifesaving nature of the procedure (Tobin et al., 2005; Kumnig et al., 2013, 2014). Ideally, candidates will be strongly motivated for transplantation; have demonstrated reliable adherence with medical care in the past; have strong family support networks; and utilize acceptance, flexibility, and problem solving in adapting to the loss of function from the injury/deficit and for future rehabilitation following transplantation (Sears Jr. et al., 1995; Olbrisch, 1996; Leo et al., 2003; Kumnig et al., 2014). A candidate who has been educated about the various risks, benefits, and demands of the transplant experience, and who has been prepared for the psychological stresses of the experience is more likely to have appropriate expectations regarding the risks of immunosuppression and surgical complications, as well as a more realistic understanding of potential functional gains after transplantation (Lanzetta et al., 2001; Sicard, 2011).

In reality, UE VCA candidates may overestimate the benefits of the procedure while underestimating the surgical risks, duration of recovery, demanding post-transplant medication regimen, and intense rehabilitation requirements (Simmons, 2000; Brenner et al., 2002; Baylis, 2004; Brouha et al., 2006; Petruzzo et al., 2010; Sicard, 2011; Kalluri and Hardinger, 2012; Kumnig et al., 2014; Kinsley et al., 2020). Unmet expectations, an inability to incorporate the transplanted hand (s) (Lanzetta et al., 2005, 2007; Petruzzo et al., 2008; Kumnig et al., 2013), and either new or recurring psychiatric conditions have been reported after UE VCA (Schuind et al., 2007), including suicide attempts (Schuind et al., 2006) and request for amputation (Petruzzo et al., 2008; Petruzzo and Dubernard, 2011). Additionally, recipients may be frustrated with the lengthy process of recovery. The loss of ability to perform tasks that were possible preoperatively also leads to initial postoperative decrease in quality of life (Petruzzo et al., 2010; Kumnig et al., 2014).

Fortunately, the majority of recipients have reported successful psychological integration of the hand(s), and improved confidence in appearance and in social situations (Schuind et al., 2006; Jablecki, 2011). Recipients that have assimilated the transplanted hand(s) into their body-/self-image are generally able to develop a sense of “ownership.” Additional important outcomes are the observed improvements in QOL and activities of daily living (Kumnig et al., 2014). It has become apparent that patients’ coping styles, support from family and friends, and financial factors are important predictors of successful outcomes (Shores, 2011). Recent findings also show that patients’ relationships to healthcare providers, as well as to family members and peers, are correlated with satisfaction (Kinsley et al., 2022). Patients may also experience stress due to media attention which has occurred in a number of UE VCA cases (Kumnig et al., 2012); this impacts the decision to undergo a UE VCA procedure and the post-transplant course. Therefore, multidimensional psychosocial evaluation and follow-up protocols should include these additional domains: health literacy regarding transplantation, assessment of pain related to amputation and phantom limb pain, family support, adaptation to prosthesis, financial and family stressors, assessed through multiple interactions with a variety of assessors including psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, hand therapists, and all team members (Dobbels et al., 2009; Shores, 2011; Kumnig et al., 2014).

This qualitative study has a similar design as the recently published qualitative investigation of Kinsley et al. (2022), which aimed to explore the role of patient-specific factors through a qualitative analysis of interviews with UE VCA recipients.

In the present study, we have adapted and expanded the interview protocol combining the interviews with those of healthcare professionals of the interdisciplinary VCA team and relatives of the UE VCA recipients and contrasting the outcomes of United States VCA recipients with those in Austria. The main goal of this qualitative research was to elucidate relevant psychosocial predictors for success or failure of UE VCA in this European cohort. By understanding these psychosocial factors, we hope to enhance existing heterogeneous screening and follow-up protocols by including identified important psychosocial factors in the evaluation and peri-operative management and optimization of potential candidates for UE VCA.

In total five patients underwent reconstructive UE VCA at the Medical University of Innsbruck so far. One of these patients who received unilateral UE VCA in 2009 died due to progressive gastric cancer, leaving a total of four potential patients, which were eligible to be invited to participate in an online interview. Additionally, online interviews with the staff of the Innsbruck VCA team were scheduled to assess the healthcare professionals’ overall expertise working in the field of UE VCA. Also, interviews with close relatives of the four transplanted patients have been planned to gather individual experiences of partners/main social daily contacts living with somebody who underwent UE VCA.

Inclusion criteria consisted of all patients and healthcare team members with direct experience undergoing VCA or providing care for VCA patients. These include all patients who have undergone UE VCA at Innsbruck, close family members of patients such as a spouse or primary caregiver, and all core members of the interdisciplinary transplant team, which includes surgeons, bioethicists, rehabilitation specialists, psychologists, dermatologists, and institutional or administrative leaders. There were no exclusion criteria other than individuals unable or unwilling to provide commentary or participate in the study. All potential participants and staff received an introductory email inviting participation in an online interview. Written informed consent was provided by the final participants.

A total of four bilateral transplanted patients as well as seven healthcare professionals of the Innsbruck VCA team were interviewed. Overall, four close relatives/partners were potentially eligible to take part in an interview; however, only one family member was enrolled in the study. The wife of the first transplanted patient did not provide informed consent (due to missing skills to realize the online interview), the second patient was living alone (without a partner), and the fifth patient lived with his mother who was almost 90 years old. Only the sister of the third patient provided informed consent to participate in this qualitative research study.

All study activities were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University Hospital, Innsbruck (vote 1044/2020). Recruitment and interviews followed a similar process to that at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Harvard Medical School) published by Kinsley et al. (2022), representing the largest UE VCA samples investigated in this way.

We conducted a total of 12 interviews: 7 with UE VCA healthcare professionals, 4 with UE VCA transplanted patients, and one with a patient’s relative. A trained interviewer conducted the interviews using a semi-structured guide. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions that asked participants about their perceptions of factors that either favored or hindered a successful transplant outcome. Topics included functional status before surgery, experience with the preparation for transplant, decision process and information transfer, rehabilitation and functional outcome after surgery, and family and social support. Interviews were conducted online and recorded with the consent of interviewees. Subsequently, a qualitative analysis of the interview transcripts was performed.

Thematic analysis followed routinely-accepted methodology in qualitative research (Kinsley et al., 2020). Six researchers collaboratively created a coding scheme consisting of 51 codes and 10 subcodes. The codes consisted of single words or short phrases to produce sections of text that meaningfully related to the study’s guiding question, “What factors influence the success of upper extremity VCA?” These codes were applied to all transcript data by six members of the Innsbruck and Harvard research group.

Members of the Innsbruck team grouped the previously created codes into themes, which were formulated as directed hypotheses. Care was taken to ensure that they had sufficient internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity to be sufficiently grouped or distinct from the other themes. We used qualitative analysis software (Atlas.ti) to extract citations supporting the themes. The Innsbruck team listened to the taped recordings and identified themes, using the qualitative analysis software to index their digital location in the recordings, creating codes that have been connected and grouped to themes. All investigators agreed upon a thematic map showing relationships between the individual themes and the guiding questions of the study (for details please see Figure 1).

The study sample consisted of 4 bilateral upper limb VCA patients, the sister of an upper limb VCA patient, and 7 upper limb VCA healthcare professionals. This latter group consisted of 5 transplant surgeons and 1 rehabilitation physician. Four participants were female and 8 were male.

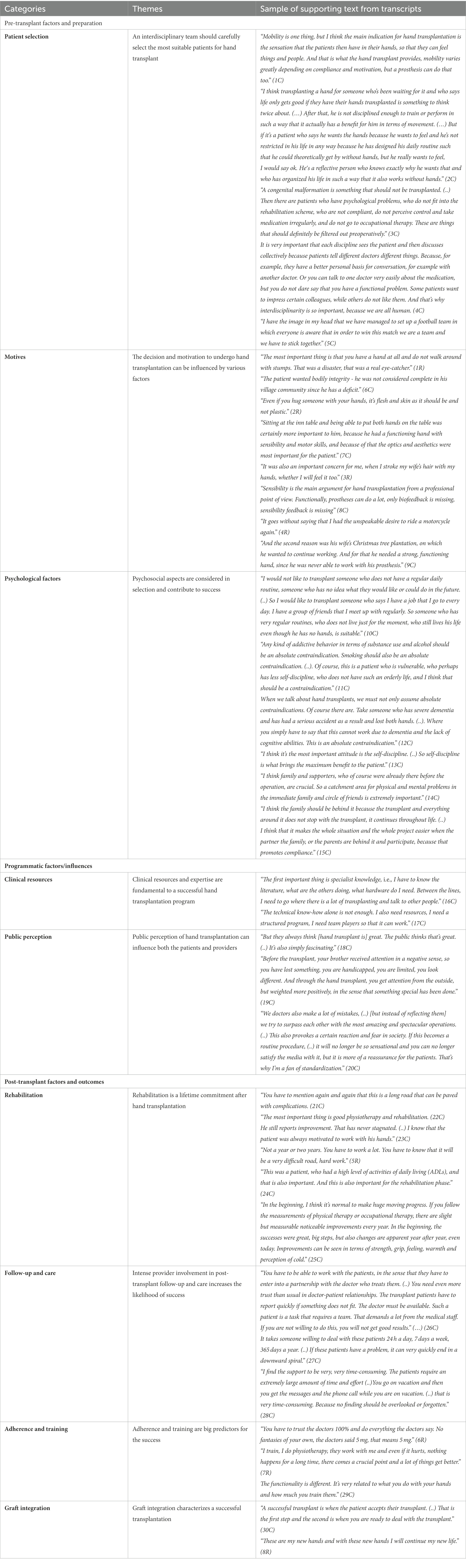

Thematic analysis of participant commentaries led to the identification of three main psychosocial domains: pre-transplant factors and preparation, programmatic factors and influences, and post-transplant factors and outcomes. For each of these three main domains, individual themes were established; these are summarized in detail below and illustrated in Figure 1. Representative participant quotations for each of the domains and themes are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Categories and themes from the thematic map, associated hypotheses and supporting quotations from the interview transcripts.

One main outcome of this qualitative research was the identification of the role of an interdisciplinary team that carefully optimizes and selects the most suitable patients for UE VCA. For pre-transplant patient selection, it can be noted that a higher level of adherence to protocols and willingness to adapt to an intense training and rehabilitation process are important psychosocial predictors of a successful outcome (2C, 3C). The independent involvement of each discipline in the UE VCA with subsequent interdisciplinary discussion, treatment planning, and task distribution enables a holistic evaluation of the patient, prevents the forgetting of information, and leads to better pre-and post-transplant treatment and overall psychosocial outcomes (4C, 5C).

The decision and motivation to undergo UE VCA transplantation can be influenced by various factors. Motives may include a desire to feel whole again or a desire for (gain of) functionality and sensibility. Presumably, since a certain level of function is achievable with prosthetics, sensibility and the sense of wholeness were more often referenced over functionality (1R, 6C, 2R, 7C, 3R, 8C, 4R, and 9C). The desire to no longer to be perceived as “handicapped” or “disabled” as well as one’s own demands and goals for the future influence the motives for undergoing a UE VCA (6C, 9C).

Psychological factors are not only considered in selection but also contribute to success of UE VCA. Factors that had a positive influence on UE VCA were the pursuit of a regular daily routine, family support, and a high degree of self-discipline (10C, 13C, 14C, 15C). On the other hand, addictive behavior and a lack of cognitive abilities were associated with a worse psychosocial and functional outcome and could be considered as areas to be addressed pre-transplant and/or as relative contraindications (11C, 12C).

Clinical resources and expertise are fundamental to a successful UE VCA transplantation program. An advanced understanding of the field, including literature and exchange with colleagues (16C), and a functional and very experienced transplant team is essential to provide the necessary infrastructure to develop a VCA program (17C).

Public perception of UE VCA transplantation can influence both patients and providers. Patients can be influenced by the public, as they primarily perceive the loss of a hand as something negative (19C). However, a successful UE VCA is often viewed as sensational by the public (19C, 20C). As UE VCA becomes more common and routine, this may reduce the sensationalism and provide more reassurance to the patients (19C, 20C).

Rehabilitation is particularly important and a lifetime commitment after UE VCA transplantation. Rehabilitation can be positively influenced by a high level of pre-transplant activities of daily living; however, the rehabilitation process can be experienced as a ‘difficult road’ paved with a variety of complications and challenges (21C, 5R, 24C). Physiotherapy and a high degree of self-motivation lead to steady improvements, in terms of sensibility and motor skills, even after several years (22C, 23C, 25C).

Intense provider involvement in post-transplant follow-up and care increases the likelihood of success. The relationship between the primary healthcare professionals and UE VCA patients differs from ‘regular’ doctor-patient relationships in intensity (26C). Maintaining a close relationship between the primary healthcare professionals and the UE VCA patient is very time consuming and demanding, but due to the often time-sensitive and critical nature of patient issues, it may be necessary to prevent complications (26C, 27C, 28C).

Both adherence and training are big predictors of success. It is essential that patients trust primary healthcare professionals regarding immunosuppressive treatment and other medical management (6R, 7R). Moreover, it is important that patients continue rehabilitation training achieve their highest potential functional improvement (7R, 29C).

Graft integration characterizes a successful transplantation. In order to be motivated through intensive rehabilitation, patients do better when they accept grafts as their own hands (30C, 8R).

In summary, the identified important psychosocial factors that lead to a better overall outcome are typically met when a VCA program provides individualized patient-centered and interdisciplinary care.

In this qualitative research on psychosocial predictors and outcomes of patients that underwent UE VCA, three main psychosocial factors have been identified: pre-transplant, programmatic, and post-transplant factors. These psychosocial factors are discussed and contrasted to findings in recent literature.

Numerous other studies have supported the importance of patient selection in optimizing patient outcomes (Brau and Clarke, 2006; Kinsley et al., 2021, 2022). Often overlooked are two key points raised by our patients and teams. Firstly, patient selection is a dynamic not a static process. Longitudinal evaluation and ongoing optimization of a potential candidate’s psychosocial circumstances is fundamental. For example, patients with a history of substance abuse can be appropriately counseled and supported peri-operatively to help them recover without relapse. Secondly, providers have an important role in optimizing patients’ outcomes, ensuring that preparation and support is adequate.

In two separate studies conducted in the US, Kinsley et al. interviewed UE VCA patients, primary caregivers, and healthcare providers to evaluate perceived predictors of transplant access. These included realistic expectations of life after transplantation, strong social support, and positive framing of one’s situation. A deep desire for limbs or an unrealistic expectation of transplant function can both pose a major barrier to accepting a limb transplant that may be imperfect despite intensive rehabilitation and side effects from lifelong immunosuppression. Patients relied heavily on their caregivers and health providers for both physical and emotional support, while expressing the desire to communicate with other transplant recipients to better set expectations.

Programmatic factors have proven challenging for almost all teams globally (Gordon et al., 2009; Gordon and Siemionow, 2009; Kinsley et al., 2021). There are a small number of patients with bilateral upper-extremity amputations who are ready medically and psychosocially for this major intervention. Matching patients who are optimized with teams able to provide the complex care necessary is an ongoing challenge (Gordon et al., 2009; Gordon and Siemionow, 2009; Siemionow and Gordon, 2010; Kumnig et al., 2012, 2013, 2014; Kumnig and Jowsey-Gregoire, 2016; Kinsley et al., 2021).

These large teams also have their own interdisciplinary challenges. We have found that while teamwork is one of the most rewarding aspects of VCA, it can also be one of the most difficult parts. Groups such as the International Society for Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation, the American Society for Reconstructive Transplantation, and the Chauvet Workgroup, all provide collaboration internationally to help educate ourselves within this small field (Jowsey-Gregoire et al., 2016; Kumnig et al., 2022). Furthermore, the International Registry on Hand and Composite Tissue Transplantation provides a superb repository of data that can further encourage collaboration (Kumnig et al., 2022).

In the US, transplant recipients have emphasized how critical it is to have timely access to a dedicated medical care team for long-term wellbeing (Brau and Clarke, 2006). Geographic barriers pose significant logistical challenges for ongoing care, particularly when compounded on financial and compliance issues. These factors are important for healthcare providers during preoperative discussions about continuity of care. Despite the expertise of multidisciplinary programs, providers struggle with setting realistic expectations of rehabilitation and recovery and predicting recipient compliance.

Post-transplantation care is often focused on medication adherence and physical rehabilitation. In our study, we notice the importance of psychosocial support in the follow-up. Rehabilitation is a lifelong commitment after UE VCA, with ongoing steady improvements in sensorimotor function continuing years after transplantation in self-motivated patients who continue their physiotherapy regimens. Maintaining a close relationship between transplant recipients and healthcare providers, although time consuming and demanding, may be necessary to prevent complications, promote adherence to immunosuppression despite adverse effects, and maximize overall functional success.

Similar findings were noted by Kinsley et al. (Brau and Clarke, 2006) in the US. The “intimate” and “special” relationship with the caregiver team was described by some patients as crucial for their practical and emotional needs, particularly during times of feeling alienated. Patients recognized their dependence and the sacrifices they may place on caregivers and care providers, and this recognition may serve as a motivating factor to maximize their independence. The desire for more involved psychological evaluation and therapy was also expressed, congruent with testaments of resilience, positive attitude, purposeful rehabilitation, and strong social supports being favorable psychosocial factors for a good functional outcome.

Future research efforts that are directed at sharing similar evaluation strategies across centers are needed to establish universal guidelines, pathways, and assessments for candidate evaluation and recipient evaluation (Dew et al., 2007; Kumnig et al., 2014). Another important component of interdisciplinary screening should be the identification of at-risk candidates. Intervention strategies to assist these candidates might then lead them to be eligible for this treatment and might especially be beneficial in supporting their ability to succeed with medication adherence and overall QOL post-transplantation (Kumnig et al., 2012, 2014; Kumnig and Jowsey-Gregoire, 2016).

The citations in Table 1 are more originating from VCA healthcare professionals compared to VCA patient families. However, the number of quotations from each group is proportional to the number of study participants from each group: of 12 participants in our study, 4 UE VCA patients, 7 were healthcare professionals, and only 1 was a patient family member. Our clinical observations show that data from patient families are difficult to collect and thus of particular value to the field, but we want Table 1 to be reflective of our actual data pool. We will certainly endeavor to continue collecting qualitative data from patient families in future studies.

Psychosocial factors are important elements in the assessment and follow-up care for UE VCA. To best capture psychosocial elements of care, protocols must be individualized, patient-centered, and interdisciplinary. Recent research has shown that proposed directions for future research should particularly focus on adherence, training, and close relationship with healthcare providers in the pre-and post-transplant course. The importance of psychosocial factors cannot be overlooked when assessing prospective UE VCA patients preoperatively and optimizing recovery and functional rehabilitation postoperatively. As with all QoL interventions, patients’ subjective experiences are relevant to assessing whether an intervention achieves its aim. Investigating psychosocial predictors and collecting outcomes is, thus, critical to justifying UE VCA as a medical intervention and to providing accurate and salient information to candidates considering the procedure.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck (vote nr.1044/2020). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

NH: writing the manuscript, performance of the research, and contributed new insights. KZ: writing and editing the manuscript. ST, SK, and MK: participated in research design, wrote the manuscript, performance of the research, and contributed new insights. ZZ: participated in research design and contributed important insights to perform the research and to wrote this manuscript. JK: contributed important insights to perform the research and wrote this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the US Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs under the Reconstructive Transplant Research Program—Qualitative Research Award No. W81XWH-17-1-0400. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the US Department of Defense.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

UE VCA, upper-extremity vascularized composite allotransplantation; ISVCA, International Society of Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation; QOL, quality of life; SOT, solid organ transplantation; VCA, vascularized composite allotransplantation.

Baylis, F. (2004). A face is not just like a hand: pace Barker. Am. J. Bioeth. 4, 30–32. doi: 10.1080/15265160490496804

Bound Alberti, F., Ridley, M., Herrington, E., Benedict, J. L., and Hall, S. (2022). What we still don’t know about vascularized composite allotransplantation (VCA) outcomes and quality of life measurements. Transplant. Rev. 36:100708. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2022.100708

Brau, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brenner, M. J., Tung, T. H., Jensen, J. N., and Mackinnon, S. E. (2002). The spectrum of complications of immunosuppression: is the time right for hand transplantation? J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 84, 1861–1870. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00020

Brouha, P., Naidu, D., Cunningham, M., Furr, A., Majzoub, R., Grossi, F. V., et al. (2006). Risk acceptance in composite-tissue allotransplantation reconstructive procedures. Microsurgery 26, 144–149. doi: 10.1002/micr.20227

Dew, M. A., Jacobs, C. L., Jowsey, S. G., Hanto, R., Miller, C., Delmonico, F. L., et al. (2007). Guidelines for the psychosocial evaluation of living unrelated kidney donors in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 7, 1047–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01751.x

Dickenson, H. (1999). Ethical issues in limb transplants. Postgrad. Med. J. 75, 513–515. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.887.513

Dobbels, F., Vanhaecke, J., Dupont, L., Nevens, F., Verleden, G., Pirenne, J., et al. (2009). Pretransplant predictors of posttransplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screening. Transplantation 87, 1497–1504. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a440ae

Dubernard, J. M. (2011). Hand and face allografts: myth, dream, and reality. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 155, 13–22

Gordon, C. R., and Siemionow, M. (2009). Requirements for the development of a hand transplantation program. Ann. Plast. Surg. 63, 262–273. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31818d45e9

Gordon, C. R., Siemionow, M., and Papay, F. (2009). The world’s experience with facial transplantation: what have we learned thus far? Ann. Plast. Surg. 63, 572–578. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181ba5245

Heineman, J., Bueno, E. M., Kiwanuka, H., Carty, M. J., Sampson, C. E., Pribaz, J. J., et al. (2020). All hands on deck: hand replantation versus transplantation. SAGE Open Medicine 8:205031212092635. doi: 10.1177/2050312120926351

Jablecki, J. (2011). World experience after more than a decade of clinical hand transplantation: update on the polish program. Hand Clin. 27, 433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2011.08.003

Jowsey-Gregoire, S., Kumnig, M., Morelon, E., et al. (2016). The Chauvet 2014 meeting report: psychiatric and psychosocial evaluation and outcomes of upper extremity grafted patients. Transplantation 100, 1453–1459. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001013

Kalluri, H. V., and Hardinger, K. L. (2012). Current state of renal transplant immunosuppression: present and future. World J. Transplant. 24, 51–68. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v2.i4.51

Kinsley, S. E., Lenhard, N. K., and Lape, E. C. (2021). Perceived success in upper-extremity vascularized composite Allotransplantation: a qualitative study. Journal of Hand Surgery America 46, 711.e711–711.e735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.01.001

Kinsley, S. E., Song, S., Petruzzo, P., Sardu, C., Losina, E., and Talbot, S. G. (2020). Psychosocial predictors of upper extremity transplantation outcomes: a review of the international registry 1998-2016. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 8:e3133. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003133

Kinsley, S. E., Williams, E. E., Lenhard, N. K., et al. (2022). A provider perspective of psychosocial predictors of upper-extremity vascularized composite Allotransplantation success. Journal of Hand Surgery in America 47, 387.e1–387.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.05.005

Kumnig, M., Jowsey, S. G., and DiMartini, A. (2014). Psychological aspects of hand transplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 19, 188–195. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000047

Kumnig, M., Jowsey, S. G., and Moreno, E. Transplant psychiatry: standards in the psychosocial assessment of candidates for reconstructive hand transplantation. American Society for Reconstructive Transplantation 3rd biennial meeting. The Drake Hotel, Chicago, IL. (2012).

Kumnig, M., Jowsey, S. G., Moreno, E., Brandacher, G., Azari, K., and Rumpold, G. (2013). An overview of psychosocial assessment procedures in reconstructive hand transplantation. Transpl. Int. 27, 417–427. doi: 10.1111/tri.12220

Kumnig, M., Jowsey, S. G., Rumpold, G., Weissenbacher, A., Hautz, T., Engelhardt, T. O., et al. (2012). The psychological assessment of candidates for reconstructive hand transplantation. Transpl. Int. 25, 573–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01463.x

Kumnig, M., and Jowsey-Gregoire, S. (2016). Key psychosocial challenges in vascularized composite allotransplantation. World J. Transplant. 6, 91–102. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i1.91

Kumnig, M., Jowsey-Gregoire, S., Bellew, M., et al. (2022). The Chauvet workgroup: a resource for the psychosocial aspects of reconstructive transplantation. Mayo Clinical Proceedings 97, 1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.02.003

Lanzetta, M., Nolli, R., Borgonovo, A., et al. (2001). Hand transplantation: ethics, immunosuppression and indications. Journal of Hand Surgery 26, 511–516. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2001.0635

Lanzetta, M., Petruzzo, P., Dubernard, J. M., Margreiter, R., Schuind, F., Breidenbach, W., et al. (2007). Second report (1998-2006) of the international registry of hand and composite tissue transplantation. Transpl. Immunol. 18, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2007.03.002

Lanzetta, M., Petruzzo, P., Margreiter, R., et al. (2005). The international registry on hand and composite tissue transplantation. Transplantation 79, 1210–1214. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000157118.28394.fa

Leo, R. J., Smith, B. A., and Mori, D. L. (2003). Guidelines for conducting a psychiatric evaluation of the unrelated kidney donor. Psychosomatics: journal of consultation liaison. Psychiatry 44, 452–460. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.6.452

Olbrisch, M. E. (1996). Ethical issues in psychological evaluation of patients for organ transplant surgery. Rehabil. Psychol. 41, 53–71. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.41.1.53

Petruzzo, P., and Dubernard, J. M. (2011). World experience after more than a decade of clinical hand transplantation: update on the French program. Hand Clin. 27, 411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2011.07.007

Petruzzo, P., Lanzetta, M., Dubernard, J. M., Margreiter, R., Schuind, F., Breidenbach, W., et al. (2008). The international registry on hand and composite tissue transplantation. Transplantation 86, 487–492. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318181fce8

Petruzzo, P., Lanzetta, M., Dubernard, J. M., et al. (2010). The international registry on hand and composite tissue transplantation. Transplantation 90, 1590–1594. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ff1472

Schuind, F., Abramowicz, D., and Schneeberger, S. (2007). Hand transplantation: the state-of-the-art. Journal of Hand Surgery 32, 2–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.09.008

Schuind, F., Van Holder, C., Mouraux, D., et al. (2006). The first Belgian hand transplantation - 37 month term results. Journal of Hand Surgery 31, 371–376. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSB.2006.01.003

Sears, S. F. Jr., Rodrigue, J. R., Greene, A. F., and Mills, R. M. Jr. (1995). Predicting quality of life with a pretransplantation assessment battery: a prospective study of cardiac recipients. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2, 335–355. doi: 10.1007/BF01991681

Shores, J. T. (2011). Recipient screening and selection: who is the right candidate for hand transplantation. Hand Clin. 27, 539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2011.07.009

Sicard, D. (2011). “Ethical aspects of non-life-saving allografts with special regard to the hand” in Hand transplantation. eds. M. Lanzetta, J. M. Dubernard, and P. Petruzzo (Milan: Springer), 107–109.

Siemionow, M. Z., and Gordon, C. R. (2010). Institutional review board-based recommendations for medical institutions pursuing protocol approval for facial transplantation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 126, 1232–1239. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ee482d

Simmons, P. D. (2000). Ethical considerations in composite tissue allotransplantation. Microsurgery 20, 458–465. doi: 10.1002/1098-2752(2000)20:8<458::AID-MICR19>3.0.CO;2-G

Singh, M., Oser, M., Zinser, J., Sisk, G., Carty, M. J., Sampson, C., et al. (2015). Psychosocial out-comes after bilateral hand transplantation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 3:e533. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000520

Singh, M., Sisk, G., Carty, M. J., Sampson, C., Blazar, P., Dyer, G., et al. (2016). Functional outcomes after bilateral hand transplantation: a 3.5-year comprehensive follow-up. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 137, 185–189. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001872

Tobin, G. R., Breidenbach, W. C., Klapheke, M. M., Bentley, F. R., Pidwell, D. J., and Simmons, P. D. (2005). Ethical considerations in the early composite tissue allograft experience: a review of the Louisville ethics program. Transplant. Proc. 37, 1392–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.12.179

Keywords: vascularized composite allotransplantation, qualitative research, psychosocial predictors, psychosocial outcomes, quality of life

Citation: Hummel NR, Zuo KJ, Talbot S, Zimmerman ZE, Katz JN, Kinsley SE and Kumnig M (2023) Psychosocial predictors in upper-extremity vascularized composite allotransplantation: A qualitative study of multidimensional experiences including patients, healthcare professionals, and close relatives. Front. Psychol. 14:1092725. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1092725

Received: 08 November 2022; Accepted: 18 January 2023;

Published: 09 February 2023.

Edited by:

Fatih Zor, Wake Forest University, United StatesReviewed by:

Yalcin Kulahci, Wake Forest University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Hummel, Zuo, Talbot, Zimmerman, Katz, Kinsley and Kumnig. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Kumnig, ✉ TWFydGluLkt1bW5pZ0BpLW1lZC5hYy5hdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.