- 1School of Government and Public Affairs, Communication University of China, Beijing, China

- 2Leiden Institute for Area Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 3Department of East Asian Studies, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei City, Taiwan

Introduction: Social media infuses modern relationships with vitality and brings a series of information dissemination with subjective consciousness. Studies have indicated that official Chinese media channels are transforming their communication style from didactic hard persuasion to softened emotional management in the digital era. However, previous studies have rarely provided valid empirical evidence for the communicational transformation. The study fills the gap by providing a longitudinal time-series analysis to reveal the pattern of communication of Chinese digital Chinese official media from 2019 to 2022.

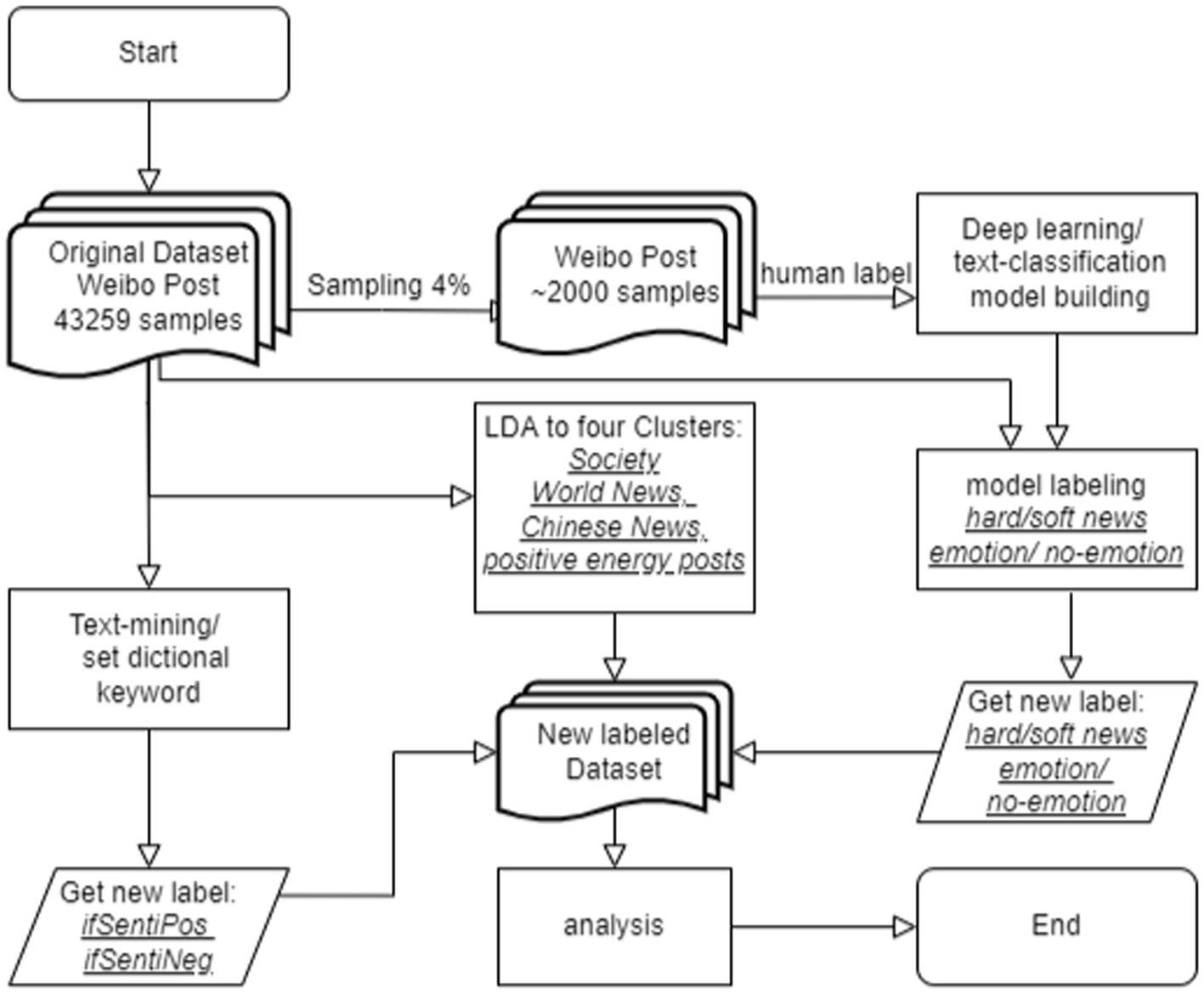

Method: The study crawler collected 43,259 posts from the People’s Daily’s Weibo account from 2019 to 2021. The study analyzed the textual data with using trained artificial intelligence models.

Results: This study explored the practices of the People’s Daily’s Weibo account from 2019 to 2021, COVID-19 is hardly normalized as it is still used as the justification for extraordinary measures in China. This study confirmed that People’s Daily’s Weibo account posts are undergoing softenization transformation, with the use of soft news, positive energy promotion, and the embedding of sentiment. Although the outburst of COVID-19 temporarily increased the media’s use of hard news, it only occur at the initial stage of the pandemic. Emotional posts occupy a nonnegligible amount of the People’s Daily Weibo content. However, the majority of posts are emotionally neutral and contribute to shaping the authoritative image of the party press.

Discussion: Overall, the People’s Daily has softened their communication style on digital platforms and used emotional mobilization, distraction, and timely information provision to balance the political logic of building an authoritative media agency and the media logic of constructing audience relevance.

Introduction

Digital media play a vital role in enabling the government to disseminate information, raise public awareness, and influence the public’s perception of events (Durant and Lambrou, 2009). Therefore, governments are increasingly prioritizing social media and creating official accounts (Huang and Lu, 2017), which has blurred the boundaries among news, propaganda, and entertainment; China is no exception. The digitalization of official media sources has led to a change in communication styles (Huang and Lu, 2017; Shao and Wang, 2017). For instance, Chinese state-run media has adopted a more nuanced approach to forming social consensus and increasing social cohesion than simply applying discursive coercion (Zhang, 2011; Edney, 2014). This led Huang (2015) to suggest that the Chinese state-run social media strategy involves hard and soft propaganda. Hard propaganda is biased information that frames the ruling party positively without mobilizing emotions, whereas soft propaganda involves emotional mobilization (Huang, 2015; Xia, 2020; Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Multiple studies have indicated that official Chinese propaganda outlets have achieved a delicate balance between positive and negative emotions to evoke emotional resonance and creative engagement (Kong, 2016; Fang and Repnikova, 2018; Gao and Wu, 2019), especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhang, 2022).

During the early stages of COVID-19, the Chinese government’s delayed reaction incurred criticism from around the world. Several studies have explored the Chinese government’s propaganda during COVID-19 (Zhang, 2022; Zhang and Jamali, 2022). Studies have suggested that the Chinese government has triggered a sense of nationalism on social media by mobilizing emotion (Zhang, 2022) and positively framed the Chinese government (Zhang and Jamali, 2022; Zhang and Xu, 2022). Although China’s digital propaganda is well documented, most studies have examined China’s digital practices through case studies or qualitative observations and interviews rather than longitudinal time-series analysis. Therefore, this study systematically examined the digital practices and propaganda of Chinese official media from 2019 to 2022. Specifically, this study explored how the Chinese official media used propaganda on Weibo during this period and how COVID-19 influenced their communication strategies. The study evaluated hard news vs. soft news, the news topics covered, and the emotional content of the news to analyze the transformation of Chinese digital propaganda and the effects of the pandemic.

This study examined the 2019, 2020, and 2021 Weibo posts of People’s Daily by using trained artificial intelligence models. The study determined that soft news dominated the People’s Daily Weibo posts, although the frequency of hard news exceeded that of soft news during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study also determined that although emotional mobilization occurred on Weibo, most posts were nonemotional in an apparent attempt to maintain a sheen of objectivity. China’s official social media posts create interaction with the public, and outlets switched to releasing authoritative information (hard news) during the early stages of COVID-19 to reduce panic and promote the stability of public sentiment.

Changing landscape of the Chinese digital media environment

Chinese media serve as the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP; Duan and Takahashi, 2017), which are widely regarded as a party–state political apparatus (Duan and Takahashi, 2017; Qi, 2018; Zhang, 2021) owned, funded, and monitored by the Chinese government (Chan and Qiu, 2001). Jian and Liu (2018) suggested that Chinese media only distributed propaganda because they were fully subsidized by the government from 1949 until the 1980s. Zhang (2021) framed Chinese official media as affiliate organizations of the Chinese government designed to spread the government’s fundamental ideologies (Duan and Takahashi, 2017). However, since the development of the economy and the commercialization of the Chinese media in the 1990s, the media have enjoyed greater freedom (Tan, 2012). Although Chinese media have adopted marketization techniques such as selling advertising, they remain under government supervision (Xu, 2016). Therefore, Wright et al. (2020) suggested that Chinese state media struggle to balance being the government mouthpiece and being a news organization.

Internet and social media use have become widespread in China. According to Statista (2018), the number of Weibo users increased substantially, from 63 million in 2010 to 350 million in 2018. Studies have suggested that social media plays a key role in Chinese politics (Schneider, 2018; Zhang, 2021; Zhang and Xu, 2022). Therefore, the Chinese government has prioritized regulating social media and the internet (Xu and Albert, 2017). Social media accounts are subject to government monitoring, and account owners must self-censor before posting (King et al., 2017). In May 2010, the Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China published a white paper on implementing a more restrictive redline for all internet users, which was followed by the Public Pledge on Self-Regulation and Professional Ethics for the Chinese Internet Industry (Xu and Albert, 2017). The Chinese government usually punishes noncompliant social media users (Ruan et al., 2021). The control of social media has become a part of state stabilization, thereby demonstrating the will to power of the Chinese authorities. Any content designed to enflame or encourage collective movement and social mobilization is the first-line target of government censorship compared with negative posts and even acrimonious criticisms of the state and its leaders and policies (King et al., 2017). Therefore, the Chinese government leaves limited space for the public to participate in politics to appease injustice (King et al., 2017; Fang and Repnikova, 2018). Yan (2020) determined that the Chinese government uses hard power (censorship) and soft power (reshaping public opinion by promulgating ideologies such as nationalism) together to make the internet a digital extension of Chinese-governed geopolitical territory.

China state media’s digitalization

According to the 47th China Statistical Report on Internet Development (CNNIC, 2021), approximately 740 million Chinese internet users access news online. Therefore, the prosperity of the internet and social media provide internet users with options other than state-owned media to receive information (Xin, 2018). Therefore, traditional state-owned media face challenges and must publish tailor-made content to increase their audience and influence while promulgating party viewpoints and policies (Li, 1998, p. 315). Chinese state media use social media platforms to confront these challenges (Huang and Lu, 2017). For instance, new organizations publish news on their websites and Weibo and WeChat accounts (Wu and Pan, 2021). Chinese state media have moved to social media and transitioned from didactic hard persuasion to softened emotion management.

Social media offers an opportunity to change the state media’s communication style (Zhu, 2017). Studies have noted that official social media accounts follow the social media communication logic (Han and Qi, 2019; Shi and Tong, 2020) of competing for attention (Durant and Lambrou, 2009). The traditional relationship between audiences and news organizations is changing because more people are accessing news through mobile devices. Sharing, commenting, and liking news have already altered the assumption of the passive audience in the traditional model of a one-way flow of information (Andersen et al., 2019, p. 2480). Social media is designed for public use, so content should attract the public (Huang and Lu, 2017). Therefore, to survive fierce competition, news organizations must understand the public’s needs to retain interest in the news (Nelson, 2019). To achieve this, Chinese state media on digital platforms have adopted simple methods of expression (Huang and Lu, 2017). Chinese official media have shifted from the mouthpiece model to a user-oriented model, with the language shifting from formal to informal to increase viewership (Huang and Lu, 2017; Shao and Wang, 2017). Therefore, the social media accounts of Chinese state media have changed the old model of “you broadcast, and I watch” to a model that encourages interaction with audiences (Huang and Lu, 2017, p. 3). However, although news media have adopted digitalization, this has failed to transform their official, exclusive, and professional nature (Wu and Pan, 2021; Zhang, 2021). Liu and Zhou (2011, p. 218) noted that although the Weibo accounts of Chinese state media serve as a tool to capture the public voice, a platform to collect sources, and a channel to obtain social news, they also serve as propaganda tools to facilitate the spread of positive news and manage crises. Therefore, the social accounts of Chinese state media have multiple identities: attention-hungry social media that must survive in a competitive (Nye, 2008) marketplace, the propaganda machine of the CCP, and a gatekeeping news organization (Thussu, 2018).

Digital practice and digital propaganda in China

Traditionally, “propaganda” has referred to “an attempt to transmit social and political values” (Kenez, 1985, p. 4). In other words, propaganda refers a means of manipulation of information or significant symbols to influence public opinion (Lasswell, 1927). The Chinese government is well known for using the mass media to conduct propaganda (Thussu, 2018). Shambaugh (2007, pp. 26–27) noted that Chinese propaganda involves “mass mobilization campaigns; the construction of ideological and educational ‘models’ to be emulated; the control of the content of newspaper articles and editorials; development of a nationwide system of loudspeakers that reached into every neighborhood and village; the domination of the broadcast media.” Chinese propaganda is used to consolidate the government’s control over society, stabilize the state, and defend national interests through self-promotion and self-advocacy (Li, 2019, p. 145; Wang, 2012; Zhang and Jamali, 2022). Chinese official media produce a massive amount of content to increase visibility to the public (Xu and Wang, 2022). Studies have suggested that Chinese media propaganda uses social media logic to publish information that appeals to the public (Xia, 2020; Zeng and Li, 2021; Xu and Wang, 2022). For instance, Chinese state media on digital platforms often post soft news rather than hard news (Liang, 2019; Zeng and Li, 2021).

On social media, Chinese state media often report news about economics, international affairs, and environmental problems in a positive tone, whereas civil rights, politics, the military, and terrorism appear less often and have a negative tone (Liang, 2019). Liang (2019) indicated that Chinese official media on digital platforms uses soft power to increase the visibility and positivity of their policies. Scholars have also suggested that the state media following social media logic also create two kinds of propaganda: hard propaganda and soft propaganda (Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Hard propaganda refers to news reports that are inaccurate, exaggerated, fabricated, favorable to China, and antagonistic toward its opponents without emotional mobilization (Huang, 2015). In this sense, hard propaganda is designed to “signal the [ruling party’s] strength in social control and [its] capacity to meet potential challenges” (Huang, 2015, p. 435). Hard propaganda usually frames the ruling party positively, promotes mainstream narratives and ideologies, exaggerates leaders’ actions, and presents disinformation regarding antagonists (Xia, 2020; Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Since Xi Jinping came to power, several studies have explored the transformation of Chinese propaganda from heavy-handed hard persuasion to more refined, emotionally resonant, and esthetically appealing soft propaganda (Huang, 2015; Statista, 2018;Zou, 2021; Mattingly and Yao, 2022). According to Huang (2018), soft propaganda is distinguished by its subtle and sleek political persuasion style by contrast with hard propaganda’s crude and heavy-handed style. Although no settled definition of soft propaganda exists, soft propaganda generally refers to propagandistic content packaged in entertaining formats with emotional mobilization (Zou, 2021; Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Therefore, soft propaganda involves a shift from politicized indoctrination to entertainment-oriented media content production. Lu and Pan (2021) determined that the Chinese government’s digital propaganda tends to include nonpolitical entertaining news content to attract viewers. For example, the propaganda apparatus increasingly synthesizes elements from visual subculture to appeal to the younger generation well-versed in popular culture (Chang and Ren, 2018). Zou (2021) noted that digital propaganda in China not only demonstrates playfulness but also mobilizes emotions through interaction. Therefore, emotional turns constitute another pattern of China’s soft propaganda transformation. Chinese soft propaganda generally arouses fear, anger, and grievances by mobilizing the public’s sense of nationalism (Huang, 2015; Mattingly and Yao, 2022). Zhang and Jamali (2022) explored how the Chinese media on Weibo report on Western vaccines to mobilize negative emotions toward foreign countries. Research has also revealed the mobilization of positive emotions in Chinese propaganda (Yang and Tang, 2018). Wang (2020) analyzed emotional mobilization through the lens of positive energy, which captures the government’s endeavors to promote optimism, confidence, and patriotism while containing negative emotions (Wang, 2020). The promotion of positive energy, according to Yang and Tang (2018), is used to align the public’s emotions with the ideological and value systems of the CCP party-state. Hird (2018) contextualized the positive energy campaign within a neoliberal emotion management regime. In this regime, the pursuit of happiness is privatized, shirking the responsibility of the public sector or private institutions. Analysis of Hird (2018) considered affective biopolitics in Foucauldian terms, which relates to regulating feelings and attitudes in line with the objectives of emotional governance. Zou (2021) used interviews to determine that official media staff members embed emotions into news media production in the service of ideological governance through institutional routines, especially during national scandals (Wang, 2020).

China’s poor handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in the early stages received considerable domestic criticism. Zhang (2022) determined that mouthpiece People’s Daily promoted positive actions from ordinary people to turn negative emotions of grief into positive national solidarity and distract the public, thereby changing the narrative. A discourse analysis conducted by Wang (2020) revealed that the Chinese government presented itself as a savior of the Chinese people during domestic national crisis by punishing officials, informing the public of effective measures, and refuting rumors that had spread on social media. Chen and Wang (2019) suggested that these discourses discipline citizens into being docile subjects who internalize state interests and have the desired emotional responses to current events. Thus, Chinese state media on digital platforms changed their practices to increase their audience and mobilized emotions to conduct soft propaganda during the COVID-19 pandemic (Zou, 2021; Mattingly and Yao, 2022).

Data collection

This study used Weibo posts from People’s Daily to explore the Chinese official media’s digital propaganda practice. People’s Daily is well known as the mouthpiece of the Central Committee of the CCP, which is the center of state power (Wu, 1994). Therefore, People’s Daily as a government organ determines the agenda for the rest of the media (Luther and Zhou, 2005; Song et al., 2016). Some scholars have noted that People’s Daily could represent or at least reflect the standpoints of the Chinese government or China’s top leadership (Wu, 1994; Mao, 2014). The official Weibo account of People’s Daily has more than 116 million followers, making it a highly influential and authoritative account (Dong et al., 2020). Therefore, the official Weibo account of People’s Daily is most representative of the digital practice and digital propaganda of the Chinese official media. This study used a web crawler to collect Weibo posts published by People’s Daily between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2021. We used this 3-year period because it contains three stages: before the pandemic (2019), the middle of the pandemic (2020), and after the pandemic (2021). This enabled us to explore the digital practices of People’s Daily and the changes that occurred after the pandemic began. The crawler collected 43,259 posts for our sample.

Research design

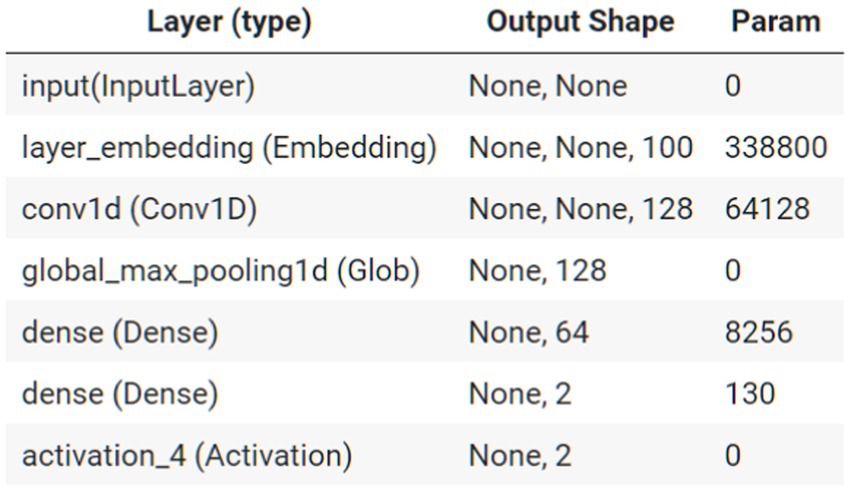

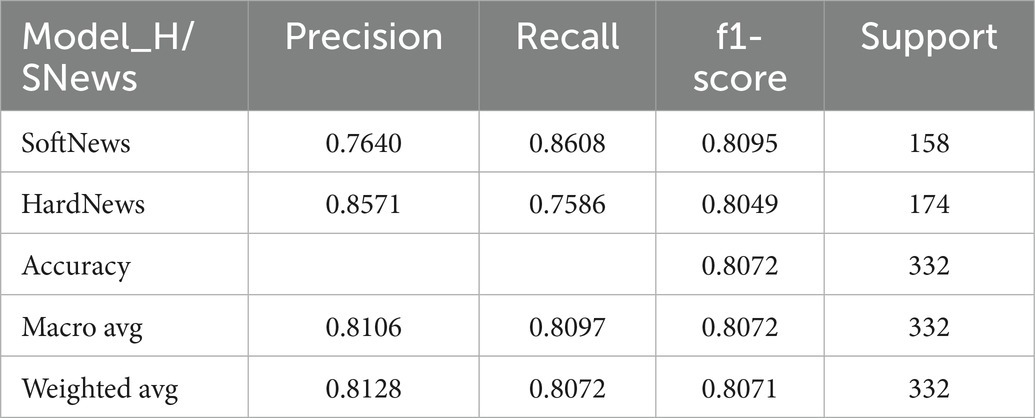

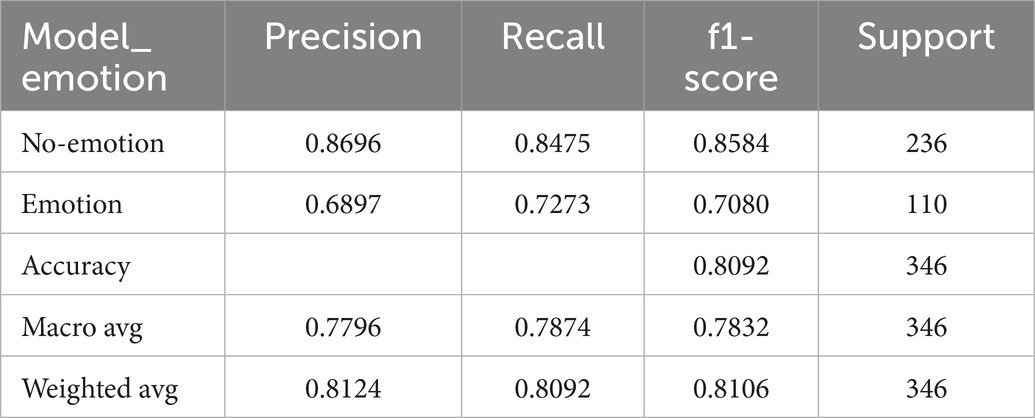

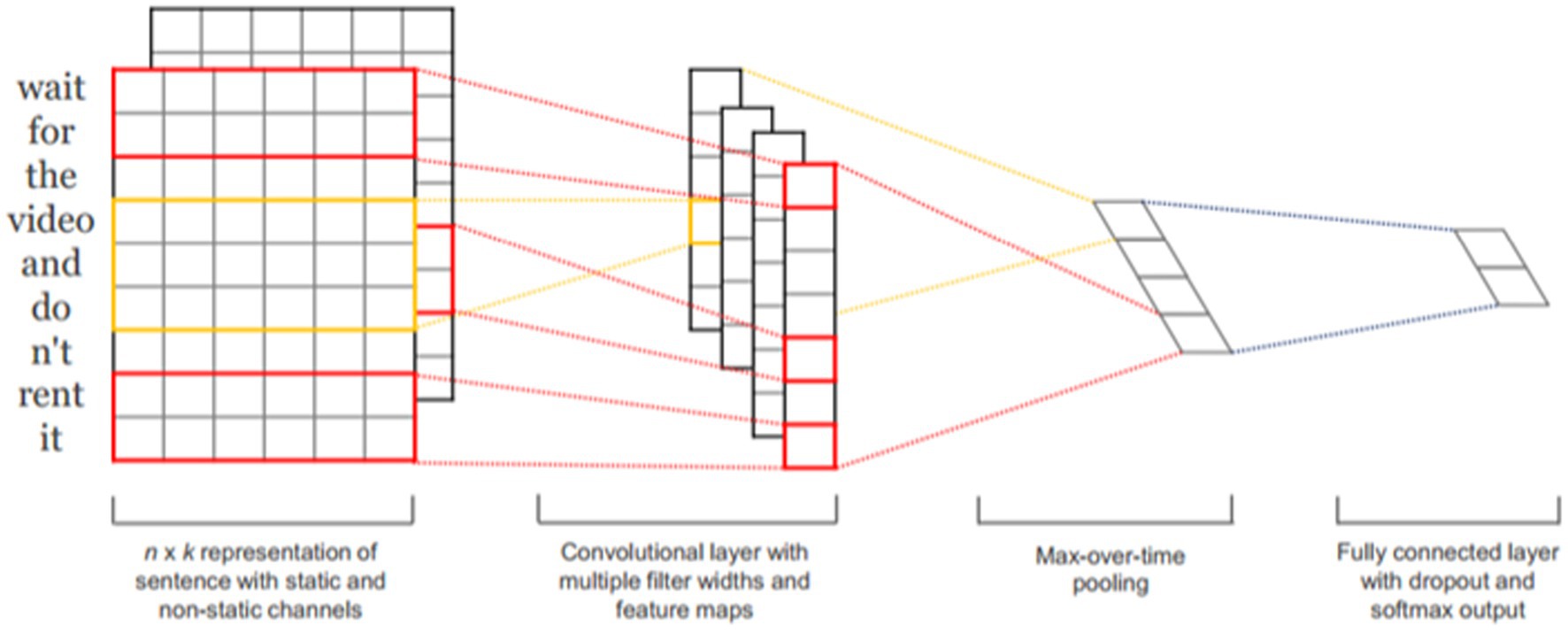

After collecting the posts, we randomly read 3,000 posts from each year and marked them as hard news or soft news (hard news = 1; soft news = −1) and as emotional or nonemotional (emotional = 1; nonemotional = −1).1 Hard news refers to major breaking news about top leaders, major issues, or disruptions in daily life (Patterson, 2000) that should be urgently reported, such as information related to COVID-19 (number of cases and epidemic prevention policy announcements), whereas soft news is “typically more sensational, more personality centered, less timebound, more practical, and more incident-based than other news,” covering human-interest stories about ordinary Chinese citizens (Patterson, 2000). We used the Python text–convolutional neural network (CNN) algorithm in the kashgari package (Eziz, 2019). CNNs have been commonly applied to analyze visual imagery. They can extract features of images and magnify these characteristics (Krizhevsky, 2012). They use a kernel to see-around-point and determine the partial features in the area. This study used a CNN to extract text features and classify them. For example, with a kernel size of 4, the text “新的一年静下心来读书吧” (“calm down and read a book in the new year”) would be broken down into “新的一年” (new year), “的一年静” (“calm new year”), “一年静下” (“calm down in the new year), and “全年静下心” (calm down all next year). Groups of four characters can be analyzed to connections between segments, which can be used to extract meaning from sequential data. Most combinations are not meaningful, but the algorithm can identify meaningful segments and increase their weight to build a model. Compared with a similar method, the bag of words, text-CNN is more appropriate for the Chinese language (Huang and Shao, 2020). Both of our main models achieved higher than 80% accuracy for the test set (Figures 1, 2; Tables 1, 2).

Figure 1. Convolutional neural network (CNN) structure (Kim, 2014).

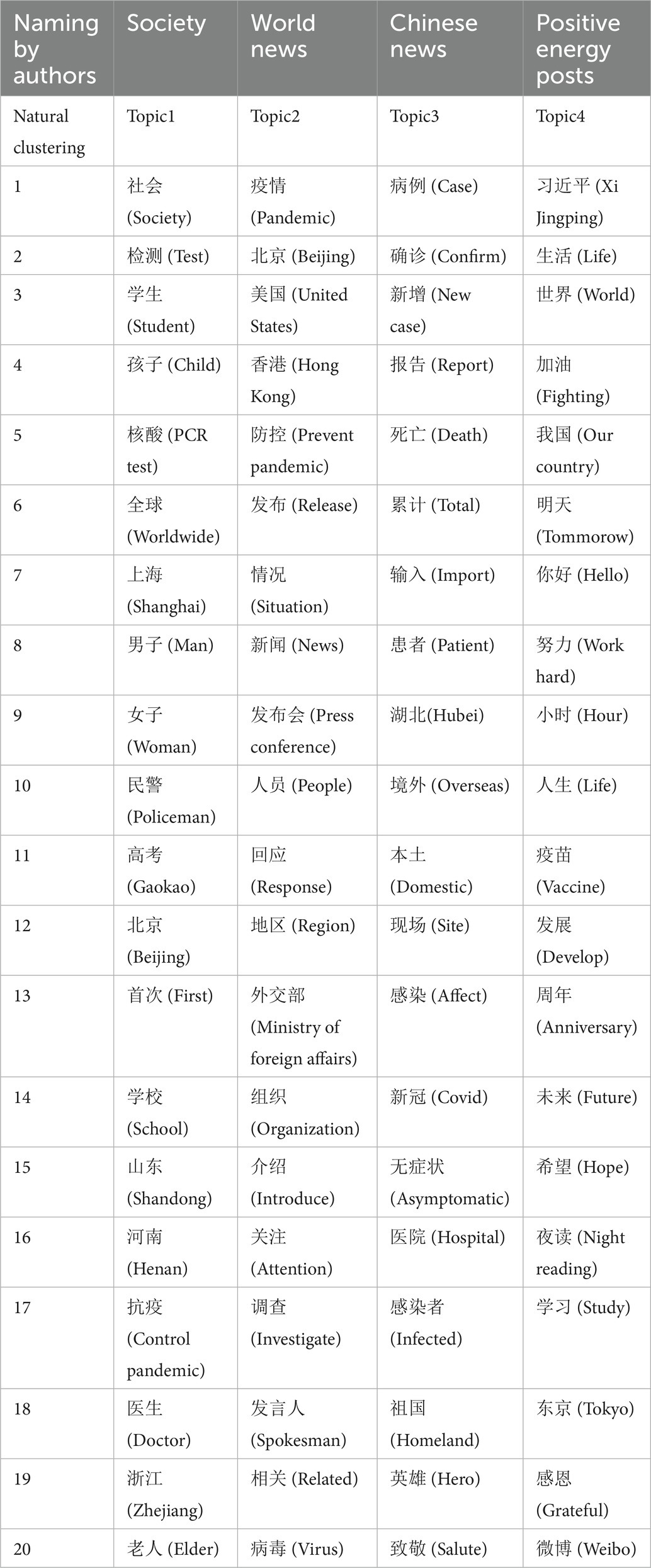

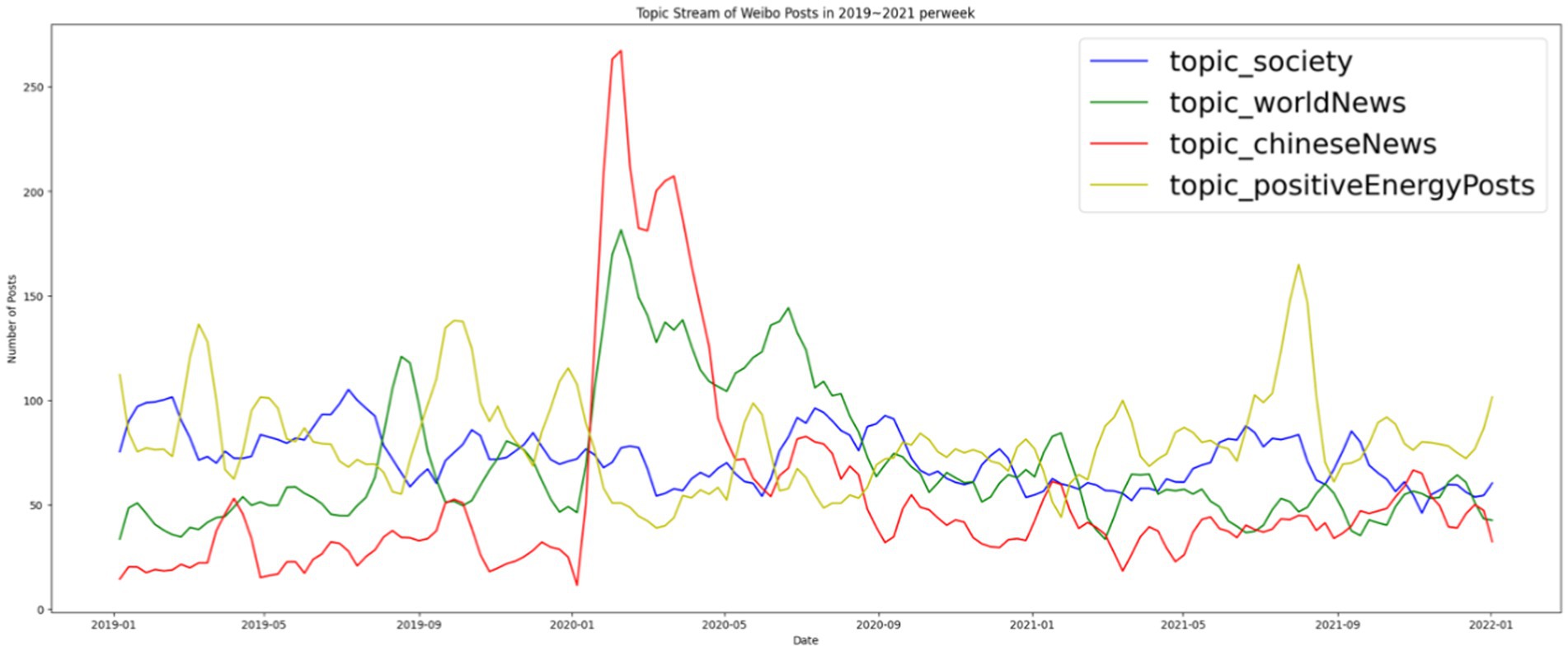

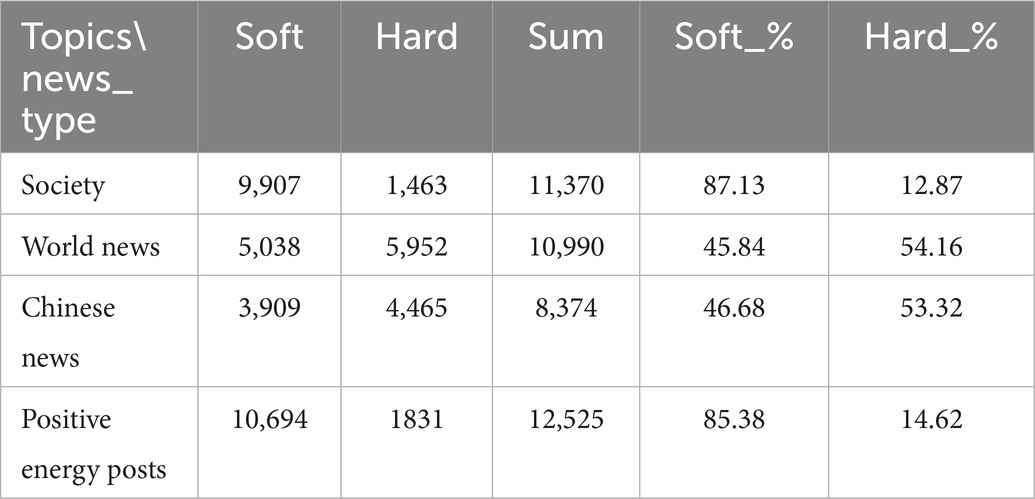

This study used latent Dirichelet allocation (LDA) to explore popular topics in People’s Daily Weibo posts. LDA is an unsupervised clustering tool that can be used to determine latent topics that we are not certain about in the first stage. We used the Python gensim package (Rehurek and Sojka, 2011) and identified 100 feature words for each topic to name the clusters. We selected four topics: social news (Chinese domestic social news, 11,370 posts), Chinese political news (China-related political news, 10,990 posts), world news (8,374 posts), and positive-energy posts (including motivational articles, 12,525 posts) (Table 3).

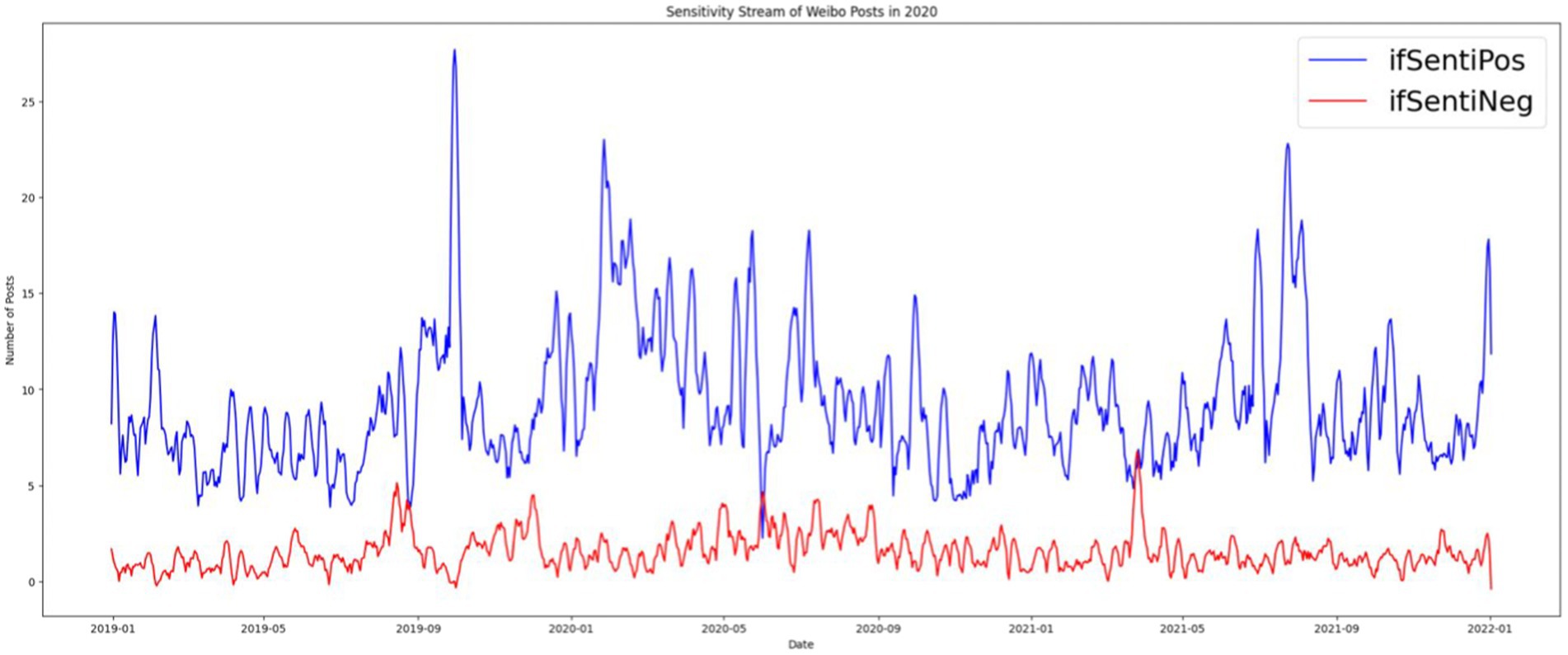

This study used the traditional dictionary method to annotate posts with positive or negative words and perform sentiment analysis. Authors with two extra coders defined a dictionary of positive sensitivity and negative sensitivity (Supplementary Appendix A). Each post that had a word in these dictionaries was labeled as 1 and 0 otherwise. We obtained the labels “ifSentiPos” (0 for 32,276 posts and 1 for 10,983 posts) and “ifSentiNeg” (0 for 40,220 posts and 1 for 3,039 posts; Figure 3).

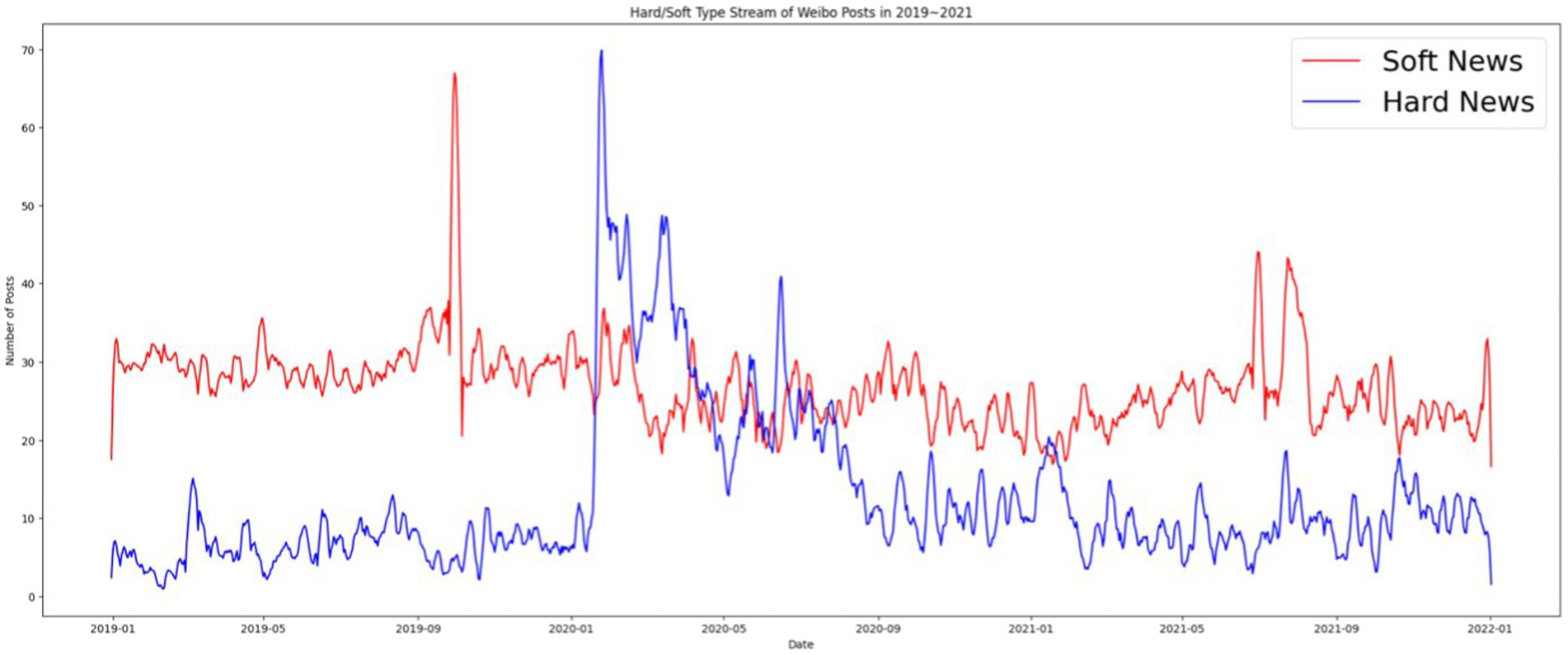

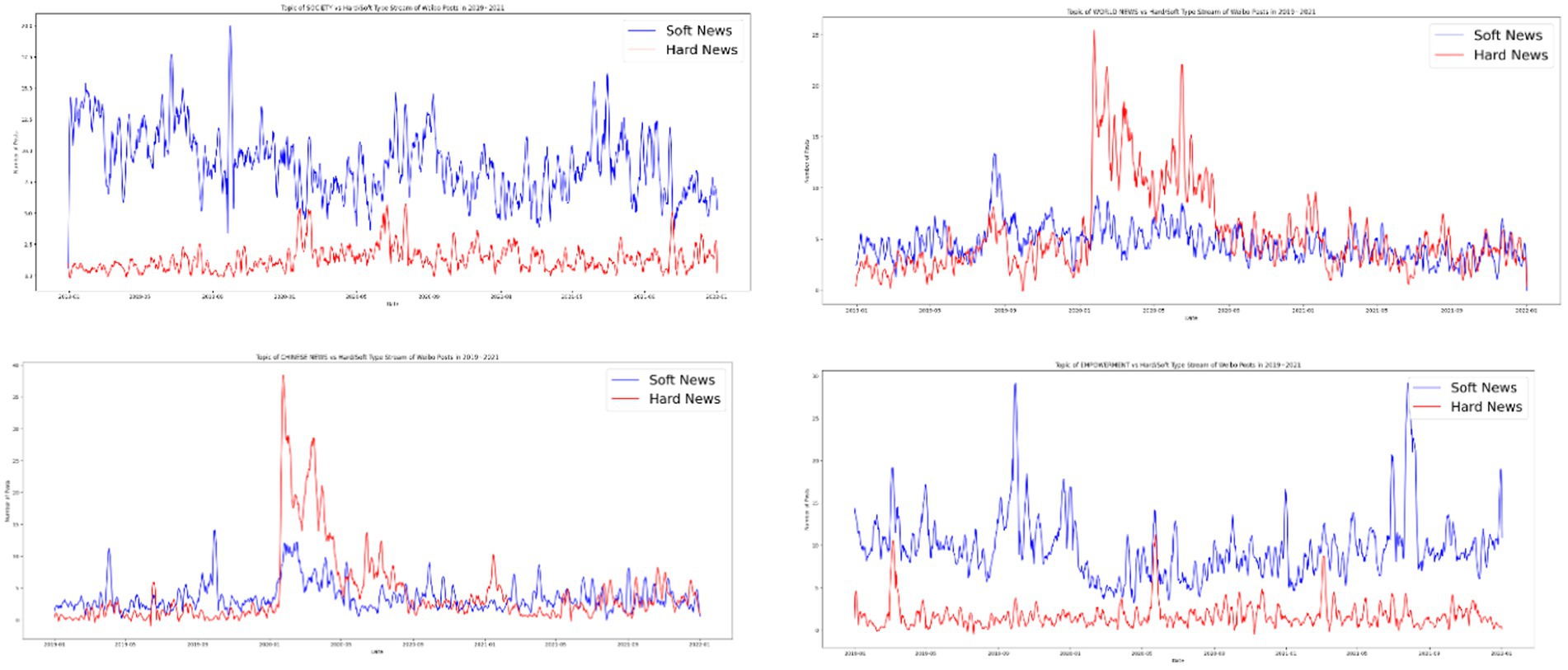

Softening of Chinese digital propaganda I: Soft news replacing hard news

Since the 2000s, scholars have acknowledged the political relevance of soft news. Baum (2002) revealed that political information packaged as soft news and therefore involving entertainment, sensationalization, and a human interest lens tends to be more appealing to apolitical audiences. Although exposure to soft news may not increase an audience’s knowledge of political reality (Prior, 2003), it effectively reinforces the audience’s existing attitudes toward foreign policy for both isolationists and internationalists (Baum, 2003). This study determined that Chinese digital propaganda increasingly involves soft news. For the majority of 2019–2021, soft news was used as the main format of posts on the People’s Daily Weibo account. The only exceptions were between January 2020 and July 2020, when the number of hard news posts exceeded that of soft news posts twice. The first surge of hard news posts followed the outbreak of COVID-19 in China (starting in late January), and the number gradually decreased to a low in May, which marked the first stage of success in China’s battle with COVID-19 because all provinces, including the epicenter of Hubei Province, released the first-level public health emergency response on May 1, 2020. The number of hard news posts exceeded that of soft news posts in June but decreased in July. This period corresponds to a short outbreak of COVID-19 in Beijing, which started from the first detected case in the Xinfadi Wholesale Market on June 5, 2020, to July 10, 2020, when no new cases were detected (Wang et al., 2021). After the outbreak in Beijing was brought under control in July, soft news maintained its dominance over hard news until the end of the study period. The findings have two implications. First, soft news was generally the dominant format of the People’s Daily Weibo posts. Second, in the time of crisis, the official media assumed the role of the legacy media, conveying politically relevant information through rational and nonemotional forms. The People’s Daily Weibo account demonstrated its identity as the party press by conveying authoritative news to the public and pass public opinion up to the political authority, the CPC government (Figure 4).

Softening of Chinese digital propaganda II: Dominance of positive-energy posts

Emotional management was the main task of the People’s Daily digital account, and positive energy was the most prevalent topic in posts. The next most prevalent was social news about depoliticized social issues. Political news was the least prevalent, with world news posts outnumbering Chinese domestic political news posts. This suggests that the People’s Daily’s social media account prioritized interaction over information; that is, they prioritized dialogic interaction with the audience over informing the public of global and domestic political news. After the pandemic started, the number of news posts rose dramatically, especially those about Chinese politics and world news. This is consistent with the findings of Zhang (2011, p. 60), who indicated that the Chinese state media endeavored to increase its relevance by privileging market logic at least as much as they did party logic to spread the views of the government. The public health crisis temporarily changed People’s Daily preferences, leading to them prioritizing informing the public over audience engagement (Table 4; Figure 5).

Table 4. Correlation between hard and soft news and topics (p < 0.001; significant correlation with chi-square contingency on news type by post topics).

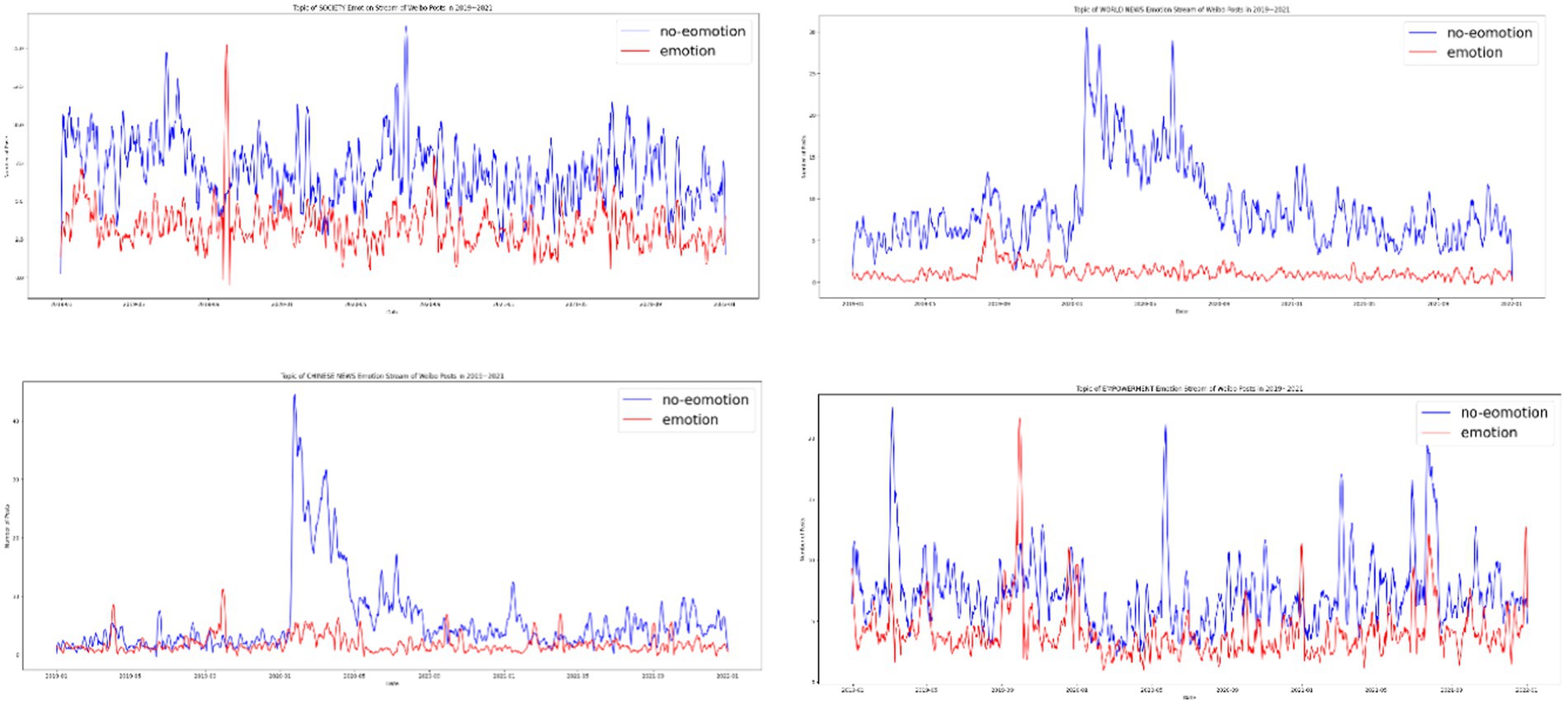

After establishing the dominance of soft news and positive posts during normal times and the surge of hard news and informational posts at the peak of the pandemic, we investigated how the People’s Daily matched topics with formats. A cross-examination revealed that the majority of soft news focused on social news (87.13%) or promoting positive energy (85.38%), although a nonnegligible amount of world news (45.84%) and Chinese news (46.68%) was covered in the form of soft news. More political news, including those relating to both international affairs and domestic politics, was packaged as hard news. Soft news was the main format for social news from People’s Daily and posts to spread positive energy, and both soft and hard news were used when domestic political news and foreign news were the subjects. During the initial stages of the pandemic, when hard news superseded soft news in the People’s Daily’s Weibo posts, more social news was expressed in the form of hard news. The same pattern was observed for Chinese domestic political and foreign news. Although positive-energy posts tended to be soft news, the outbreak of COVID-19 led to several positive-energy posts in the form of hard news (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Hard news vs. soft news by topic over time; upper left, society; upper right, world news; lower left, Chinese political; lower right, positive energy.

This study determined that the pandemic prompted the People’s Daily Weibo account to pivot to being a traditional media outlet that disseminates hard news. However, COVID-19 did not have a long-term effect on communication strategies, and soft news regained dominance shortly after the pandemic.

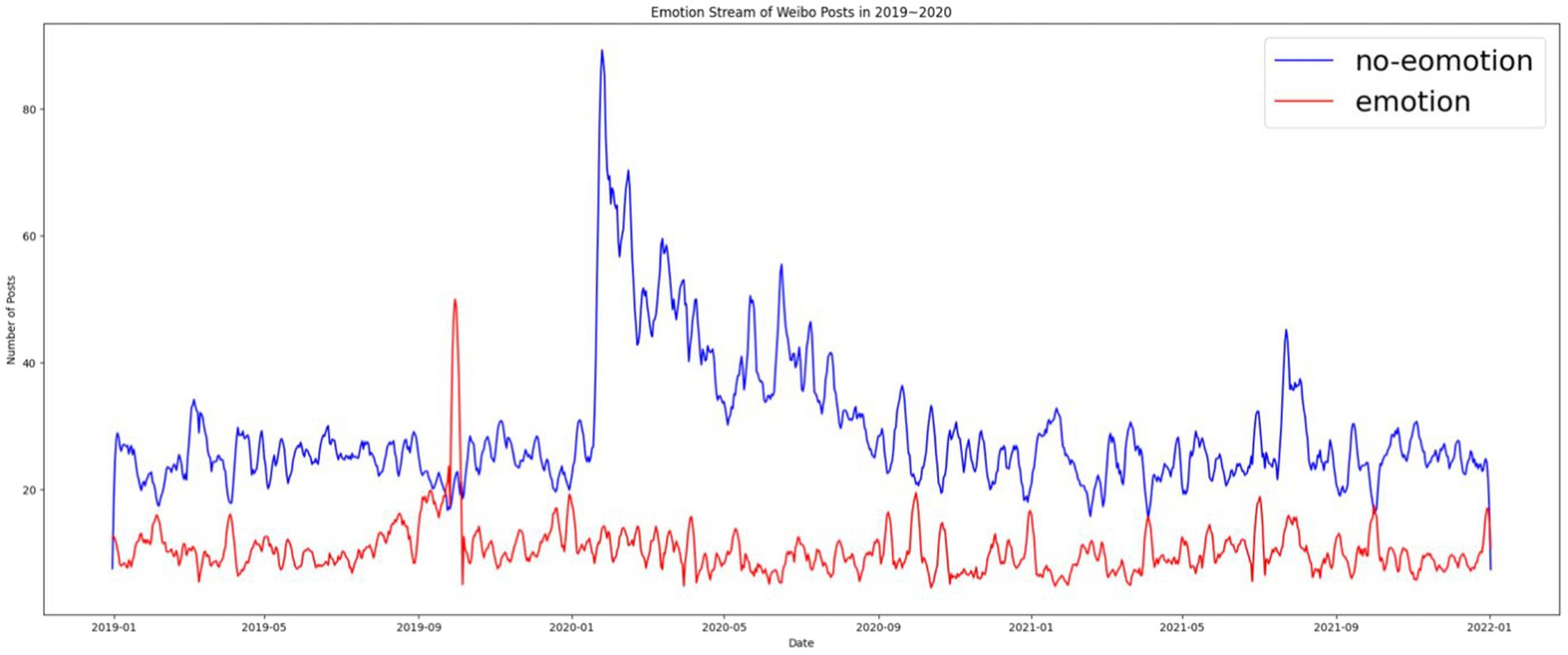

Softening of Chinese digital propaganda III: Emotionalization of the party press’s digital accounts

Traditionally, emotions are irrelevant to hard news about serious topics such as international trade and domestic and foreign politics (Tuchman, 1973). By contrast, soft news is expected to be emotional, sensational, and personality centered (Patterson, 2000; Plasser, 2005). We expected a positive association between soft news and emotionality in news posts. Given that soft news was the dominant news format on the People’s Daily Weibo account, we expected that news with emotions would also dominate. However, we observed that nonemotional news was dominant except for in October 2019 during the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The state-run media reduced the importance of emotion to cultivate an air of objectivity. However, emotional mobilization occurred throughout, and we observed that most posts contained positive emotion. The number of posts with negative sentiments only exceeded the number with positive sentiments in September 2019, June 2020, and April 2021, which corresponds to a high point for the Hong Kong protests, the rise of criticism and speculation about the origins of SARS-CoV-2 in China, and disputes over Xinjiang cotton, respectively. Those are occasions in which People’s Daily either published articles attacking China’s critics or defending Chinese governmental policies against external criticism, and negative sentiment was used to reinforce the critical rhetoric in the posts (Figures 7, 8).

Positive-energy posts designed to stimulate optimism and resilience contained the highest density of emotions. Less emotional forms of news were social news, Chinese political news, and world news, in descending order. We examined not only the relationship between emotions and the topics of posts but also the relationship between the valence of emotions and post topics. Social news, Chinese political news, and positive energy posts were more likely to be linked to positive sentiments. People’s Daily tended to present Chinese political news with a positive sentiment. By contrast, news related to foreign countries tended to include both positive and negative sentiments. Although both positive and negative news about foreign countries increased during the early stages of the pandemic, positive news appeared at a higher frequency. This positivity in world news was due to coverage of foreign countries’ expressions of prayers, good wishes, and foreign aid for China. However, starting in March 2020, the tone of world news turned negative until July. The main reason is that during this period, critiques of China’s early-stage mismanagement of the pandemic appeared along with investigative reports on the source of COVID-19. The People’s Daily Weibo shifted from being a positive energy machine to defending the Chinese government, including defending governmental policies from both domestic and international criticism. At the same time, positive domestic news increased as People’s Daily attempted to counter negative external criticism. When the stabilized, the amount of positive news returned to prepandemic levels. In addition, we observed that the number of positive-energy posts decreased dramatically. Overall, we observed that People’s Daily preferred to post positive news about China, whereas the tone of international news depended on the event (Figures 9, 10).

Figure 9. Emotionality of news over time by topic; upper left, society; upper right, world news; lower left, Chinese political news; lower right, positive energy posts.

Figure 10. Positive and negative sentiment in the news by topic; upper left, society; upper right, world news; lower left, Chinese political news; lower right, positive energy posts.

We observed three indicators of the softening of the Chinese party press’s digital strategy. First, we observed that soft news that focused on nonpolitical or long-term topics or framed political news from a dramatic, sensational, and human interest–based perspective dominated the People’s Daily Weibo account. This indicates that the Chinese state media’s digital strategy softened as the market logic of appealing to the audience prevailed over the party logic of conveying authoritative news information. Second, we detected a predominance of positive-energy posts. Posts that stimulated positive emotions such as comfort, excitement, gratitude, and warmth were widespread on the People’s Daily Weibo posts. Positive-energy posts were highly likely to be presented in the form of soft news, including that regarding Chinese domestic social news. Even for news about foreign countries and Chinese domestic politics, almost half of the posts were presented as soft news. The third marker of the softening of the Chinese state media’s digital strategy is the embeddedness of emotions. By contrast with the notion that Chinese digital news is often considerably emotional, we observed that the majority of posts were emotionally neutral. This means that although China’s state media integrated sentiment into its social media content, posts without emotions were still dominant. Although qualitative studies have tended to identify the mobilization of both positive and negative emotions in China’s news posts, our research demonstrated that positive emotions were dominant among sentimental posts. Chinese domestic stories were given positive coverage, whereas foreign countries received mixed treatment, with the tone varying by perspective on China.

Discussion

Drawing on a longitudinal study of the People’s Daily Weibo account, this study solved three puzzles. First, we mapped the Chinese state media’s digital strategies from 2019 to 2022. The time frame enabled us not only to perform an empirical analysis of trends but also to determine the effects of COVID-19 on China’s digital propaganda strategies. Second, our research responded to the increase in scholarship on China’s soft propaganda in the digital era. Unlike case studies that have revealed the dimensions of the transformation of China’s digital propaganda strategy, we used computer-aided textual analysis to validate our results and determine the extent to which China’s digital state media softened. Third, we considered how COVID-19 shaped China’s digital media strategies.

The softening of China’s digital propaganda is an extension of Chinese propaganda’s marketization and commercialization. Our research supported the findings of other studies indicating that Chinese digital propaganda involves social media logic and utilizes soft news and positive energy posts to engage with audiences (Liang, 2019; Zeng and Li, 2021). Thus, the Chinese government used soft propaganda, namely by packaging propagandistic content in nonpolitical entertaining formats (Zou, 2021; Mattingly and Yao, 2022), especially during nonpandemic times. However, our results are inconsistent with the notion that Chinese propaganda is becoming more emotional. Although Zou (2021) suggested that emotional mobilization is increasing in official social media posts, this study finds that the majority of posts are emotional neutral. Posts only contained strong emotions to refute criticism when China faced external or domestic discursive attacks. Emotional mobilization is more likely to help stabilize the Chinese government’s control when that control is under threat (Zhang and Jamali, 2022). Therefore, emotional mobilization is a tool for the Chinese government to distract the public when the Chinese government is challenged. As expected, domestic political news received positive coverage, but foreign news received mixed coverage. When foreign countries expressed friendly diplomatic signals, Chinese digital official media tended to give them positive coverage. When foreign countries adopted antagonistic attitudes toward China, they gave them negative coverage. Therefore, the role of the Chinese state-run media on any platform remains maintaining social stability, defending national interests, and strengthening the government’s position (Li, 2019, p. 145; Wang, 2012).

Studies have suggested that the Chinese state-run media mobilized emotion during COVID-19 (Zou, 2021; Zhang, 2022). The results partially support this notion. We observed that emotional mobilization was used but not in the majority of posts during the pandemic. COVID-19 caused the Chinese official media to return to releasing authoritative information, temporarily reduce the amount of soft news, and release hard news and nonemotional news. This may be because the Chinese government relied on official media to inform the public of the severity of the pandemic and the necessary response measures (Han et al., 2021). This indicates that People’s Daily was sought to balance being the legacy media of a party press and a popular social media account. However, the uptick in hard news did not last long. When the pandemic came under control, soft news and positive-energy posts regained dominance. Overall, Chinese propaganda combines hard and soft propaganda to maintain its authority, market relevance, and credibility.

Conclusion

The internet has changed the digital practices and propaganda model of the Chinese state-run media, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhang, 2022). This study determined that COVID-19 strongly affected the Chinese state-run media’s practices on Weibo; however, the effects were short lived. Chinese state-run media benefit considerably from soft propaganda, and the changes during COVID-19 were only an emergency measure taken by the Chinese government. Chinese state media have developed a diverse toolbox and applied nuanced measures ranging from emotional mobilization and distraction to timely updates to manage domestic public opinion. Further research may benefit from qualitative content analysis to elucidate how news posts on different topics are packaged as soft or hard news and how emotions are embedded in various posts, especially positive-energy posts. Although this study suggest that emotional mobilization is not significant, however, its overall tendency is increasing. Hence, it could be interesting to explore how the state-led media mobilize emotion on social media through a qualitative analysis. This study could also be extended by combining content analysis with interview (staffs at state-led media). A major question that remains is the extent to which the softening of Chinese digital propaganda was influenced by organizational culture of Chinese state-led media.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The authors also would like to acknowledge their gratitude for funding from Ministry of Science and Technology “Knowledge Graph of China Studies: Knowledge Extraction, Graph Database, Knowledge Generation” (MOST 110-2628-H-003-002-MY4, Ministry of Science and Technology). The research also receives financial support from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant number: 2022M712941).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1049671/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^These materials are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Andersen, E. M., Grønning, A., Hietaketo, M., and Johansson, M. (2019). Direct reader address in health-related online news articles: imposing problems and projecting desires for action and change onto readers. Journal. Stud. 20, 2478–2494. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2019.1603080

Baum, M. A. (2002). Sex, lies, and war: how soft news brings foreign policy to the inattentive public. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 96, 91–109. doi: 10.1017/S0003055402004252

Baum, M. A. (2003). Soft news and political knowledge: evidence of absence or absence of evidence? Polit. Commun. 20, 173–190. doi: 10.1080/10584600390211181

Chan, J. M., and Qiu, J. L. (2001). “China: media liberalization under authoritarianism” in Media Reform: Democratizing the Media, Democratizing the State. eds. M. E. Price, B. Rozumilowicz, and S. G. Verhulst (London: Routledge), 27–46.

Chang, J., and Ren, H. (2018). The powerful image and the imagination of power: the ‘new visual turn’ of the CPC’s propaganda strategy since its 18th National Congress in 2012. Asian J. Commun. 28, 1–19.

Chen, Z., and Wang, C. Y. (2019). The Discipline of Happiness: The Foucauldian Use of the “Positive Energy” Discourse in China’s Ideological Works. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 48, 201–225. doi: 10.1177/1868102619899409

CNNIC (2021). The 47th China statistical report on internet development. Available at: https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202104/P020210420557302172744.pdf

Dong, W., Tao, J., Xia, X., Ye, L., Xu, H., Jiang, P., et al. (2020). Public emotions and rumors spread during the COVID-19 epidemic in China: web-based correlation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22:e21933. doi: 10.2196/21933

Duan, R., and Takahashi, B. (2017). The two-way flow of news: a comparative study of American and Chinese newspaper coverage of Beijing’s air pollution. Int. Commun. Gaz. 79, 83–107. doi: 10.1177/1748048516656303

Eziz, E. (2019). Kashgari. Available at: https://github.com/BrikerMan/Kashgari (Accessed May 15, 2022).

Fang, K., and Repnikova, M. (2018). Demystifying “little pink”: the creation and evolution of a gendered label for nationalistic activists in China. New Media Soc. 20, 2162–2185. doi: 10.1177/1461444817731923

Gao, P., and Wu, Y. (2019). From Agenda Setting to Emotion Setting: Emotion Guidance of People’s Daily during China-US trade disputes 从议程设置到情绪设置: 中美贸易摩擦期间《 人民日报》 的情绪引导.. Modern Communication [现代传播: 中国传媒大学学报], 10, 67–71.

Han, Y., and Qi, X. (2019). Research on the polarization of China-related public opinion on twitter: a case study of the Sino–U.S. trade dispute. Mod. Commun. 3, 144–150.

Han, X., Wang, J., Zhang, M., and Wang, X. (2020). Using Social Media to Mine and Analyze Public Opinion Related to COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082788

Hird, D. (2018) in Smile yourself happy: Zheng Nengliang and the discursive construction of happy subjects. eds. G. Wielander and D. Hird (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press), 106–128.

Huang, H. (2015). Propaganda as Signaling. Comp. Polit. 47, 419–444. doi: 10.5129/001041515816103220

Huang, L., and Lu, W. (2017). Functions and roles of social media in media transformation in China: a case study of “@ CCTV NEWS”. Telematics Inform. 34, 774–785. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.015

Huang, S., and Shao, H. (2020). Applying natural language processing and text mining to classifying child custody cases and predicting outcomes. Nat. Taiwan Univ. Law J. 49, 195–224.

Jian, G., and Liu, T. (2018). Journalist social media practice in China: a review and synthesis. Journalism 19, 1452–1470.

Kenez, P. (1985). The Birth of the Propaganda State: Soviet Methods of Mass Mobilization, 1917–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Kim, Y. (2014). Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.3115/v1/D14-1181

King, G., Pan, J., and Roberts, M. E. (2017). How the Chinese government fabricates social media posts for strategic distraction, not engaged argument. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 111, 484–501. doi: 10.1017/S0003055417000144

Kong, S. (2016). Popular media, social emotion and public discourse in contemporary China. London, Routledge

Krizhevsky, A. S.-L. (2012). “Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. eds. M. I. Jordan, Y. LeCun, and S. A. Solla (New York: The MIT Press), 1097–1105.

Lasswell, H. D. (1927). The theory of political propaganda. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 21, 627–631. doi: 10.2307/1945515

Li, Z. (1998). Popular journalism with Chinese characteristics: from revolutionary modernity to popular modernity. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 1, 307–328. doi: 10.1177/136787799800100301

Li, H. (2019). New media public diplomacy under the belt and road initiative: theory and practice. Acad. Forum 2, 142–148.

Liang, F. (2019). The new silk road on Facebook: how China’s official media cover and frame a national initiative for global audiences. Commun. Public 4, 261–275. doi: 10.1177/2057047319894654

Liu, Y., and Zhou, Y. (2011). “Social Media in China: rising Weibo in government.” in 5th IEEE International Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies. Daejeon.

Lu, Y., and Pan, J. (2021). Capturing clicks: how the Chinese government uses clickbait to compete for visibility. Polit. Commun. 38, 23–54. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2020.1765914

Luther, C. A., and Zhou, X. (2005). Within the boundaries of politics: news framing of SARS in China and the United States. J. Mass Commun. Q. 82, 857–872. doi: 10.1177/107769900508200407

Mao, Z. (2014). Cosmopolitanism and global risk: news framing of the Asian financial crisis and the European debt crisis. Int. J. Commun. 8, 1029–1048.

Mattingly, D. C., and Yao, E. (2022). How soft propaganda persuades. Comp. Pol. Stud. 55, 1569–1594. doi: 10.1177/00104140211047403

Nelson, J. (2019). The next media regime: the pursuit of ‘audience engagement’ in journalism. Journalism. doi: 10.1177/1464884919862375

Nye, J. S. Jr. (2008). Public diplomacy and soft power. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 616, 94–109. doi: 10.1177/0002716207311699

Patterson, T.E. (2000). Doing Well and Doing Good: How Soft News Are Shrinking the News Audience and Weakening Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Plasser, F. (2005). From hard to soft news standards? How political journalists in different media systems evaluate the shifting quality of news. Harvard Int. J. Press Politics 10, 47–68. doi: 10.1177/1081180X05277746

Prior, M. (2003). Any good news in soft news? The impact of soft news preference on political knowledge. Polit. Commun. 20, 149–171. doi: 10.1080/10584600390211172

Qi, D. (2018). The roles of government, businesses, universities and media in China’s think tank fever: a comparison with the American think tank system. China Int. J. 16, 31–50. doi: 10.1353/chn.2018.0012

Rehurek, R., and Sojka, P. (2011). Gensim–python framework for vector space modelling. NLP Centre, Faculty of Informatics, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic, 3.

Ruan, L., Knockel, J., and Crete-Nishihata, M. (2021). Information control by public punishment: the logic of signalling repression in China. China Info. 35, 133–157. doi: 10.1177/0920203X20963010

Shambaugh, D. (2007). China’s propaganda system: institutions, processes and efficacy. China J. 57, 25–58. doi: 10.1086/tcj.57.20066240

Shao, P., and Wang, Y. (2017). How does social media change Chinese political culture? The for-mation of fragmentized public sphere. Telematics Inform. 34, 694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.018

Shi, A., and Tong, T. (2020). Digital public diplomacy under the COVID-19 epidemic: challenges and innovation. Int. Commun. 5, 24–27.

Song, Y., Lu, Y., Chang, T.-K., and Huang, Y. (2016). Polls in an authoritarian space: reporting and representing public opinion in China. Asian J. Commun. 27, 339–356. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2016.1261362

Statista (2018). Number of microblog users in China from December 2010 to December 2018. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/321806/user-number-of-microblogs-in-china/

Tan, Y. (2012). Organizational ethics of Chinese mass media. J. Mass Media Ethics 27, 277–293. doi: 10.1080/08900523.2012.746124

Thussu, D. (2018). A new global communication order for a multipolar world. Commun. Res. Pract. 4, 52–66. doi: 10.1080/22041451.2018.1432988

Tuchman, G. (1973). Making news by doing work: routinizing the unexpected. Am. J. Sociol. 79, 110–131. doi: 10.1086/225510

Wang, Y. (2012). Domestic constraints on the rise of Chinese public diplomacy. Hague J. Diplom. 7, 459–472. doi: 10.1163/1871191X-12341237

Wang, G. (2020). Legitimization strategies in China's official media: the 2018 vaccine scandal in China. Soc. Semiot. 30, 685–698. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2020.1766262

Wang, X.-L., Lin, X., Yang, P., Wu, Z.-Y., Li, G., McGoogan, J. M., et al. (2021). Coronavirus disease 2019 Outbreak in Beijing’s Xinfadi Market, China: A modeling study to inform future resurgence response. Infect. Dis. Poverty 10:62. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00843-2

Wright, K., Scott, M., and Bunce, M. (2020). Soft power, hard news: how journalists at state-funded transnational media legitimize their work. Int. J. Press Politics 25, 607–631. doi: 10.1177/1940161220922832

Wu, G. (1994). Command communication: the politics of editorial formulation in the People's daily. China Q. 137, 194–211. doi: 10.1017/S0305741000034111

Wu, G., and Pan, C. (2021). Audience engagement with news on Chinese social media: a discourse analysis of the People’s daily official account on WeChat. Discourse Commun., 6, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/17504813211026567

Xia, L. (2020). “Impact of power relations on news translation in China” in Analysing Chinese Language and Discourse Across Layers and Genres. ed. W. Wang (Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters), 178–193.

Xin, X. (2018). Popularizing party journalism in China in the age of social media: the case of Xinhua news agency. Glob. Media China 3, 3–17. doi: 10.1177/2059436418768331

Xu, Y. (2016). Modeling the adoption of social media by newspaper organizations: an organiza-tional ecology approach. Telematics Inform. 34, 151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.002

Xu, B., and Albert, E. (2017). Media censorship in China. Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/media-censorship-china (Accessed October 10, 2021).

Xu, W. W., and Wang, R. (2022). Nationalizing truth: digital practices and influences of state-affiliated Media in a Time of global pandemic and geopolitical decoupling. Int. J. Commun. 16, 356–385.

Yan, F. (2020). Managing ‘digital China’ during the Covid-19 pandemic: nationalist stimulation and its backlash. Postdig. Sci. Educ. 2, 639–644. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00181-w

Yang, P., and Tang, L. (2018). ‘Positive energy’: hegemonic intervention and online media discourse in China’s xi Jinping era. China Int. J. 16, 1–22. doi: 10.1353/chn.2018.0000

Zeng, W., and Li, D. (2021). Presenting China’s image through the translation of comments: a case study of the WeChat subscription account of reference news. Perspectives, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2021.1960397

Zhang, X. (2011). The Transformation of Political Communication in China: From Propaganda to Hegemony, Singapore: World Scientific.

Zhang, D. (2021). The media and think tanks in China: the construction and propagation of a think tank. Media Asia 48, 123–138. doi: 10.1080/01296612.2021.1899785

Zhang, C. (2022). Contested disaster nationalism in the digital age: emotional registers and geopolitical imaginaries in COVID-19 narratives on Chinese social media. Rev. Int. Stud. 48, 219–242. doi: 10.1017/S0260210522000018

Zhang, D., and Jamali, A. B. (2022). China’s “weaponized” vaccine: intertwining between international and domestic politics. East Asia 39, 279–296. doi: 10.1007/s12140-021-09382-x

Zhang, D., and Xu, Y. (2022). When nationalism encounters the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding Chinese nationalism from media use and media trust. Glob. Soc., 1–21. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2022.2098092

Zhu, W. (2017). “The impacts of social media on political communication: a case study of news on Chinese Officials' corruption.” in 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering.

Keywords: China, propoganda, COVID-19, Weibo, state-run media

Citation: Zhang C, Zhang D and Shao HL (2023) The softening of Chinese digital propaganda: Evidence from the People’s Daily Weibo account during the pandemic. Front. Psychol. 14:1049671. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1049671

Edited by:

Richard G. Ellefritz, University of The Bahamas, BahamasReviewed by:

Ştefan Vlăduţescu, University of Craiova, RomaniaJan Martijn Meij, Florida Gulf Coast University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Zhang, Zhang and Shao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dechun Zhang, ZC56aGFuZ0BodW0ubGVpZGVudW5pdi5ubA==; Hsuan Lei Shao, aGxzaGFvMkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Chang Zhang

Chang Zhang Dechun Zhang

Dechun Zhang Hsuan Lei Shao

Hsuan Lei Shao