- 1Department of English, School of Foreign Languages, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Chinese and Bilingual Studies, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3College of Education Science, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China

To better understand Mandarin-speaking children’s acquisition of non-canonical word orders, we tested comprehension and production of Mandarin non-canonical active ba-construction and passive bei-construction, in comparison with canonical active SVO sentences among 180 children between three and 6 years of age. Our results showed that children had more difficulties with bei-construction compared to SVO sentences in both comprehension and production, but early problems of ba-construction only lied in production. We discussed these patterns in connection with two accounts of language acquisition which attribute language development to the maturation of grammar or to the exposure to the input, respectively.

1. Introduction

One of the most basic tasks for language learners is to correctly understand and express who does what to whom, which is typically encoded in an active sentence with the canonical SVO word order in Mandarin like (1a). Meanwhile, Mandarin has non-canonical ba-construction (S-ba-O-V) and passive bei-construction (O-bei-S-V) as shown in (1b) and (1c).

(1) a. laohu yao-lee ’yu.

tiger bite-PFV crocodile.

‘The tiger bit the crocodile.’

b. laohu ba e’yuyao-le.

tiger BA crocodile bite-PFV.

‘The tiger bit the crocodile.’

c. laohu bei e’yuyao-le.

tiger BEI crocodile bite-PFV.

‘The tiger was bitten by the crocodile.’

How does a Mandarin-speaking child learn to identify the agent and the patient in these different structures? Theoretical accounts for this issue at the syntax-semantics interface mainly fall into two camps. The maturation approach couched in generative grammar proposes that representations of underlying syntactic structures are innate, but the derivations of some syntactic constructions are not fully represented in child grammar until a certain age (e.g., Borer and Wexler (1987)’s A-Chain Deficit Hypothesis; Chomsky, 1995). By contrast, the usage-based approach suggests that the syntactic constructions gradually build up as children get more exposure to instances of these constructions in the input (e.g., Tomasello, 2003; Goldberg, 2006; see Abbot-Smith and Tomassello, 2016 for a review). The ba- and bei-constructions in Mandarin involve different syntactic movements and are used with different frequencies, thus they can serve as a good test case for examining the two accounts, and provide new insights into the nature of early syntactic development.

In the present study, we explore Mandarin-speaking children’s acquisition of ba- and bei-constructions compared to the canonical SVO sentences. In the remainder of the Introduction, we will briefly introduce the syntactic and semantic properties of ba and bei sentences, and discuss the implications for acquisition with a review of relevant developmental works. We will end this section by raising the research questions of our study.

In both ba- and bei-constructions, ba and bei appear between two noun phrases and indicate the thematic roles of the two arguments (Li and Thompson, 1981). In ba-construction like (1b), the noun phrase after ba is typically the patient; and the construction implies that the patient is “being affected, dealt with or disposed of” (see Sybesma, 1999, p. 132, for a summary). In bei-construction like (1c), the noun phrase after bei is typically the agent while the noun phrase in the surface subject position before bei is the patient. The bei-construction highlights the patient and its affectedness (Li, 1990; Sun, 1991).

In the generative framework, ba is widely regarded as a light verb that assigns an Accusative Case to its object (Bender, 2000; Tian, 2003; Huang et al., 2009). The derivation of ba-construction involves A-movement in which the post-verb patient argument raises to the preverbal position and receives Case from ba as shown below (Huang et al., 2009).

(2) (=1b) laohu ba e’yu yao-le

tiger BA crocodile bite-PFV.

The derivation of the passive bei-construction is more complex and has been under debate. Here we follow Huang’s (1999) approach treating bei as a verb that takes a clausal complement (IP) (see more elaboration in Huang, 2013 and a similar proposal in Bruening and Tran, 2015). The object of the embedded clause is a null operator (OP) and it moves to the specifier position of the embedded clause ([Spec, IP]), then it forms a relation of predication with the matrix subject as shown in (3). Semantically, bei-sentences like (3) express that the matrix subject (laohu “tiger” in (3)) ends up with the property of being an x such that the embedded subject (e’yu “crocodile”) acts upon (yao “bite”) x (Huang et al., 2009).

(3) (=1c) laohu bei e’ yuyao-le.

tiger BEI crocodile bite-PFV.

The ba- and bei-constructions have often been discussed together since they are closely related variations of the SVO order: in general, the subject of the ba-construction takes an agent role and corresponds to the noun phrase appearing after bei while the object of ba, taking a patient role, would surface as the matrix subject of the bei-construction. But these two constructions differ in an important way: the noun phrase after ba cannot be omitted as shown in (4); the noun phrase after bei can be omitted and (5) is called a short passive compared to the long passive in (3). Unlike English where short and long passives have the same syntactic structure and the by-phrase is optional, short passives in Mandarin undergo a different syntactic movement from long passives (Huang et al., 2009). Our study is focused on long passives. We are interested in how children interpret and express the two event roles (i.e., agent and patient) explicitly in different constructions.

(4) * laohu bayao-le.

tiger BAbite-PFV.

Intended meaning: ‘The tiger bit someone.’

(5) laohu bei yao-le.

tiger BEI bite-PFV.

‘The tiger was bitten (by someone).’

Both ba- and bei-constructions are non-canonical as the thematic roles and syntactic positions are not canonically mapped in syntactic derivation. Moreover, these two constructions are much less frequent compared to SVO sentences. To evaluate the availability of both constructions in children’s input, we examined child-directed speech in Zhou’s (2001) corpus, which includes cross-sectional data of 40 mother–child pairs. In this corpus, the Mandarin-speaking children fall into four age groups—14, 20, 26 and 32 months—with 10 children in each group; thus the parent speech could reflect what children hear when their language is growing from the two-word stage to full sentences. The context for the interaction between a mother and her child was a semi-structured play scenario, which is common and representative of everyday communication. Among the total 7,101 parent utterances after removing repetitions and unintelligible utterances, 4,040 utterances were SVO sentences, 332 were ba sentences, and only two were bei sentences, including one long passive and one short passive (the rest were interjections or one-word utterances). This suggests that bei-construction is extremely rare in the input. Apart from syntactic complexity, bei-construction has the semantic connotation that the patient argument has undergone some adverse influence from the action of the agent argument (e.g., Shi, 2005), which may contribute to the extremely low frequency of the construction in everyday parent–child interactions.

According to the maturation account, the formation of ba-construction and bei-construction undergoes syntactic movements. However, the former involves A-movement which occurs within the vP, while the latter involves operator movement in which the null operator moves out of the vP to the edge of IP. Would the different types of movement have an effect on learning the two constructions? In the Minimalist framework, Chomsky (2001) proposed the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) in (6a), under which the object of a verb cannot move out of the vP phase unless v is “defective” (i.e., it does not assign an external argument as in passives). Based on PIC, Wexler (2004, 2007) in his account for English-speaking children’s difficulties with passives proposed that unlike adults, young children lack knowledge about “defective” v (see the Universal Phase Requirement, UPR in (6b)). In other words, in a premature grammar, all vPs are barriers that prevent the object of a verb to move further. Thus passive sentences are misunderstood as active sentences by young children until the maturation of their grammar.

(6) a. PIC: When working at a phase, the edge (the head and any specifiers) of the next lower phase is available for analysis, but nothing lower than the edge. In particular the complement is not available.

b. UPR: for immature children until around age five, v always defines a phase, whether or not v is defective.

If PIC is innate and UPR is universal (as assumed by the maturation approach), then they would predict that ba-construction is available to Mandarin-speaking children from the beginning since the construction only involves a vP-internal movement. In comparison, acquisition of bei-construction which involves long-distance movement out of vP is delayed until the maturation of knowledge about “defective” v and young children may misinterpret bei-sentences as active sentences.

Previous studies have shown Mandarin-speaking children’s difficulties with bei-construction. Using act-out experiments, Chang (1986) showed that even 5-year-olds had non-adult-like comprehension of bei-construction (e.g., they misunderstood bei-sentences as active sentences). The acquisition of ba-construction has also attracted some attention and has often been compared with the acquisition of passives. Using grammaticality judgment and sentence correction tasks, Gong (2007) tested ba- and bei-constructions in 4- and 5-year-olds. The results revealed a clear development from age 4 to age 5, but even 5-year-olds made considerable mistakes in both constructions; particularly, the performance on ba-construction seemed not to be better than that on bei-construction. Liu and Ning (2009) compared the acquisition of unaccusatives, ba-construction, and bei-construction in children from age 2 to age 6. In that study, worse performance on bei-construction compared to the other two was detected in both comprehension and elicited-production tasks. Recent works adopted online measurements to investigate children’s processing of ba- and bei-constructions. Huang et al. (2013) used the visual-world paradigm to examine how 5-year-olds (and adults) assigned thematic roles in sentence comprehension. Their results suggest that passives may involve re-assignment of agent and patient roles, which would lead to processing difficulties and comprehension errors. In comparison, Zhou and Ma (2018) used the same paradigm and found that both 3-year-olds and 5-year-olds could use ba and bei as cues to correctly assign thematic roles. In sum, prior research has adopted a variety of methods exploring the comprehension and production of ba- and bei-constructions in preschool children, but results concerning whether passives are more difficult and acquired later than ba-construction are mixed. Moreover, most of prior studies have not systematically compared ba- and bei-constructions against the canonical SVO sentences in children’s acquisition, and thus it is impossible to examine the effect of syntactic movement in the generative framework. In addition, it is not clear what errors children made in previous tasks.

Apart from the syntactic derivation, ba- and bei-constructions differ in input frequency. The usage-based account of language acquisition argues that frequency plays an important role in children’s learning of a specific construction. For instance, the early difficulties with passives in English-speaking children are attributed to a lack of exposure to passive sentences, which have a low frequency in adult speech (Harris and Flora, 1982; Gordon and Chafetz, 1990; Brooks and Tomasello, 1999). This account predicts that Mandarin-speaking children would acquire SVO sentences first, and then the ba-construction, while bei-construction would be learned even later due to the extreme poverty of the input. Previous naturalistic studies on Mandarin-speaking children’s early production confirmed the prediction to some extent. Ba sentences emerged around age 2 after the appearance of SVO sentences (Yang and Xiao, 2008). 3-year-old children could produce ba sentences with novel verbs (Hsu, 2014). By 4 and a half years, children could use more complex ba-constructions (e.g., using resultative verb compounds instead of single verbs) and their production became adult-like (Li et al., 1990; Li, 1995; Deng et al., 2018). By contrast, bei-construction did not appear until 2 and a half years and more importantly, early bei-sentences were short passives, the derivation of which does not involve null-operator movement and thus is structurally simpler (Zhou et al., 1992; Zhou, 1997). In addition, children seem to be sensitive to the aspectual properties of ba and bei from early on: both ba and bei sentences occur more frequently in perfective than imperfective aspect in child speech (Deng et al., 2018). However, naturalistic data mainly show the production of different sentence structures in young children. What children can produce might be different from what they habitually produce in everyday life. Moreover, it is impossible to assess what children avoid in their utterances. Therefore, children’s linguistic competence may not be fully reflected from the naturalistic data.

To sum up, the SVO word order is canonical and unmarked in Mandarin. Ba-construction and bei-construction are non-canonical word orders and in both constructions, the patient argument is not in the post-verbal object position. Semantically, both constructions highlight the affectedness of the patient argument. Despite their similarities, the two constructions involve two different types of syntactic movement and differ in their frequencies in child-directed speech.

The present study measures how well children (3;6-6;5) comprehend and produce ba and bei sentences compared to the canonical SVO sentences. First, the results are expected to reveal whether the two constructions have similar developmental patterns in preschool children given the mixed findings in prior research. Second, ba- and bei-constructions can be taken as a test case to evaluate the maturation account and the usage-based account of language acquisition. Under the maturation account, we would expect similar performance between ba and SVO sentences but worse performance on bei sentences. By contrast, under the usage-based account, we would expect performance to be best on SVO sentences, poorer on ba-construction, and the poorest on bei-construction. Third, we will examine what kind of errors children make in comprehending and producing ba and bei sentences and discuss why such errors may occur. Together, our results will present a comprehensive picture of how knowledge of sentence structures develops in Mandarin-speaking preschoolers.

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a picture selection task (Leonard et al., 2013; Armon-Lotem et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2016, among many others) to evaluate Mandarin-speaking children’s comprehension of active sentences with the canonical SVO word order, active sentences with a non-canonical S-ba-O-V word order, and passive sentences with a non-canonical O-bei-S-V word order. We conducted a structural priming task (Messenger et al., 2012a,b; Hao and Chondrogianni, 2021, among many others) to evaluate Mandarin-speaking children’s production of the three types of sentences.

2.1. Participants

One hundred and eighty Mandarin-speaking children participated in the two tasks. The participants fell into three age groups: 4-year-olds (N = 68, Female = 37, Male = 31; 3;6–4;5, M = 4;0), 5-year-olds (N = 66, Female = 38, Male = 28; 4;6–5;5, M = 5;0), and 6-year-olds (N = 46, Female = 24, Male =22; 5;6–6;5, M = 5;10). Children were recruited from preschools in Shanghai and Nanjing, China. A consent form was signed by the children’s parents. Children could stop and withdraw from the study at any point they did not want to continue. Data from an additional group of nine children were collected but excluded from analyses because they finished less than two-thirds of the questions. The order of the two tasks was counterbalanced across children.

2.2. Stimuli

2.2.1. Sentences and pictures for the comprehension task

For the comprehension task, we created six test sentences for each sentence type, all of which were recorded by a female speaker of Mandarin using a slow conversational speech rate. To increase the variety of the stimuli, among the six sentences of one sentence type, three sentences were shorter with bare nouns and three sentences were longer with the nouns preceded by a color modifier (see examples of two test sentences in (7)). Two additional passive sentences were created for practice (see Supplementary material 1 for a full list of sentences). The test sentences for SVO and ba-constructions described the same events (i.e., the noun phrases and the verbs were the same). All bare nouns were common disyllabic words denoting animals familiar to children. All color modifiers had a disyllabic color term X-se “X-color” followed by the attributive marker de (Li and Thompson, 1981; Yip and Rimmington, 2004). Participants took a pretest color recognition task in which nine colors were shown in a 3*3 grid on the screen (see Supplementary material 2 for the stimuli). Upon hearing a color term from the experimenter, participants were requested to pick out the matched picture. All participants succeeded in identifying all of the nine colors, among which six were used in the task. All verbs were monosyllabic words denoting an action that involved an agent and a patient. According to the Communicative Development Inventory (CDI) for Mandarin Chinese (Hao et al., 2008), apart from two verbs ya “press” and bang “tie,” all of the words used in the test sentences were already produced by a majority of children at the age of 2;6 (M = 83.2%, SD = 11.2%). As for the two verbs ya “press” and bang “tie,” they also appeared in the following production task and children had no problem using these two words. We also considered the semantic connotation of bei-construction when choosing verbs for our test sentences. Specifically, the patient underwent some negative influence in the events denoted by verbs such as bang “tie.” Therefore, the contexts for using bei sentences were appropriate. We had similar considerations for the design of prime sentences in the following production task.

(7) a. shorter trial:

wuguibeixiaomaobang-zhe.

turtleBEIcattie-PROG.

‘The turtle is tied by the cat.’

b. longer trial:

hongse dewuguibeiheisedexiaomao bang-zhe.

redPARTturtleBEIblackPARTcattie-PROG.

‘The red turtle is tied by the black cat.’

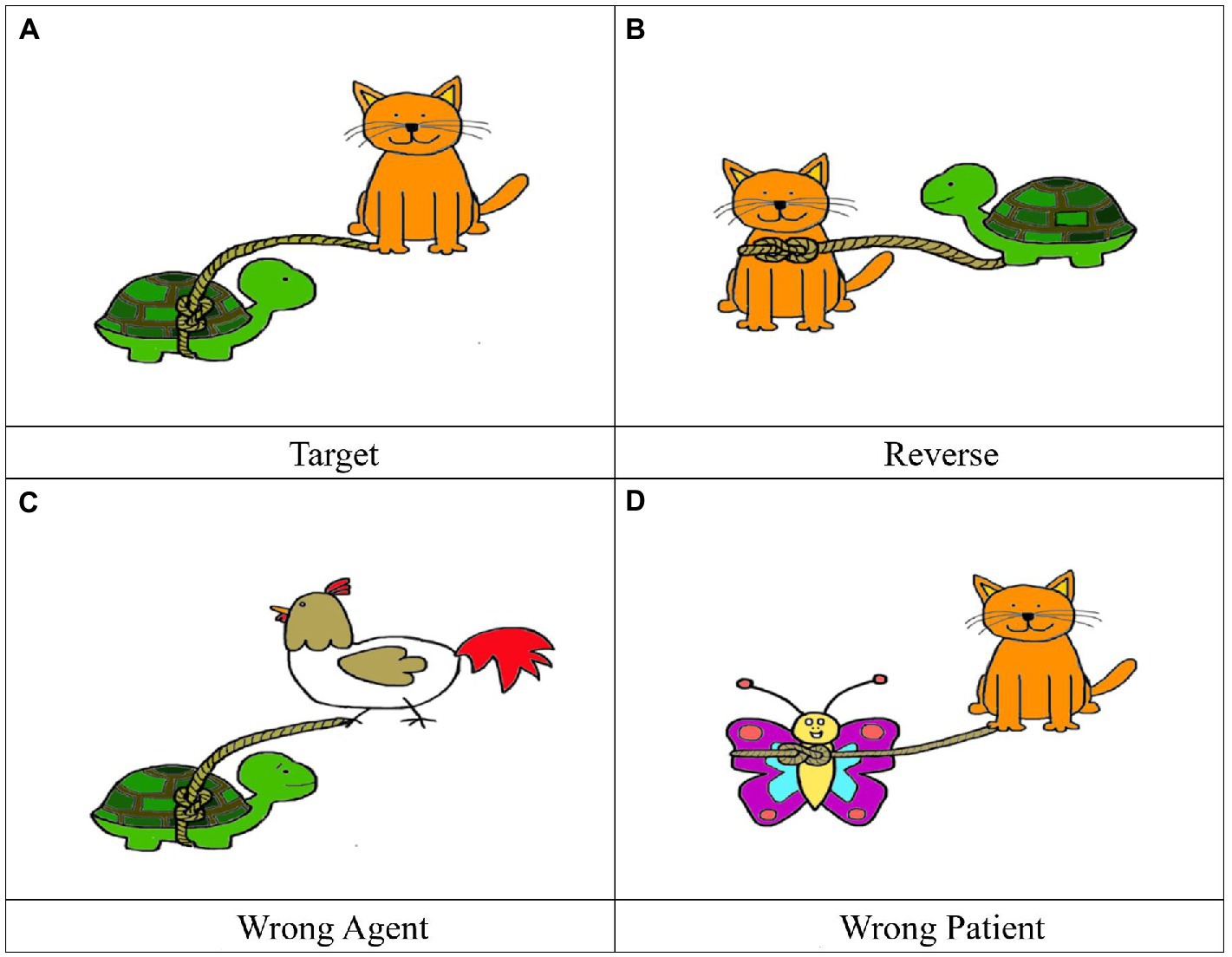

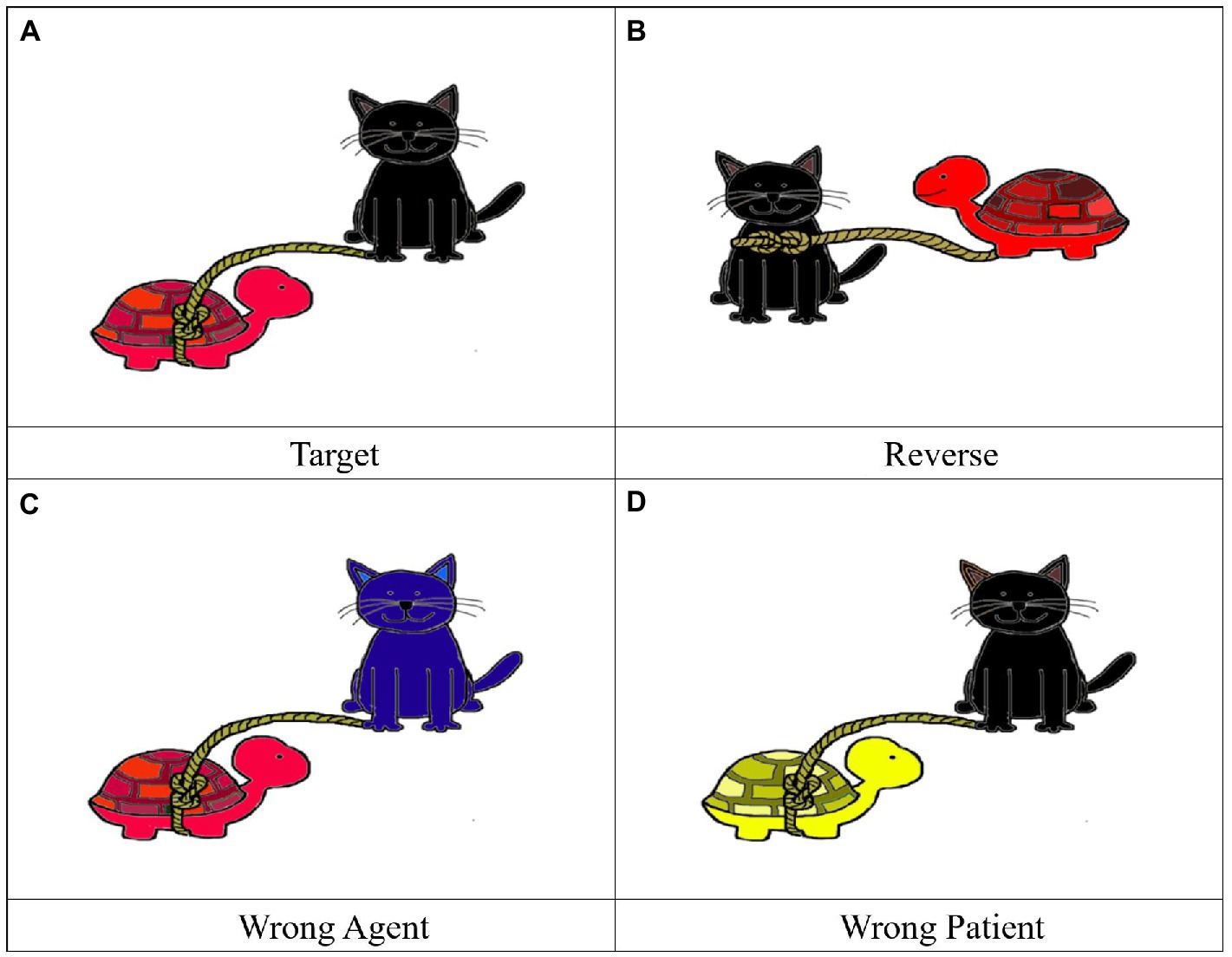

Four pictures including one target and three distractors were designed for each test sentence. For shorter test sentences, the Target picture matched the meaning of the sentence. The Reverse picture had the animals described in the sentence but the thematic relation between the agent and the patient was reverse. In the Wrong Agent picture, the agent animal did not match the test sentence. In the Wrong Patient picture, the patient animal did not match the test sentence. Figure 1 shows the four pictures for (7a). For longer test sentences, the Target picture matched the meaning of the sentence; particularly, the colors of both animals matched the description. In the Reverse picture, both animals and their colors matched the test sentence, but the thematic relation was reverse. In the Wrong Agent picture, the color of the agent animal did not match the test sentence. In the Wrong Patient picture, the color of the patient animal did not match the test sentence Figure 2 shows the four pictures for (7b). The four pictures appeared on a 2*2 split screen with the location of the target and the distractors randomized.

2.2.2. Sentences and pictures for the production task

For the production task, we created eight prime sentences for each sentence type, among which two were used for practice and six were used for testing. Each prime sentence was paired with a target sentence, and the paired prime and target sentences differed only in the second noun phrase as shown in (8) (see Supplementary material 3 for a full list of sentences). We made paired prime and target sentences differ minimally in only one noun phrase because our pilot results showed that young children before 4 years of age had great difficulties producing the target sentence when it differed from the prime sentence in more than one component. The sentences for SVO and ba-constructions described the same events (i.e., the noun phrases and the verbs were the same). All bare nouns were di- or tri-syllabic words denoting either common animals or persons familiar to children. All verbs were monosyllabic words denoting an action that involved an agent and a patient. According to the CDI for Mandarin Chinese (Hao et al., 2008), a majority of the words used in this task were already produced by children at the age of 2 years and a half (M = 80.8%, SD = 0.180). Our pilot results further showed that children had no problems with the words that were not included in the CDI list.

(8) a. youdiyuanti-le hushi. (prime sentence)

mailman kick-PFV nurse.

‘The mailman kicked the nurse.’

b. youdiyuan ti-le jingcha. (target sentence).

mailman kick-PFV policeman.

‘The mailman kicked the policeman.’

Trials of the same sentence types were blocked. We designed three testing orders “SVO-bei-ba,” “ba-SVO-bei,” “SVO-ba-bei.” Children were randomly assigned to the three orders and the effect of order will be examined in data analysis. Interspersed among the three blocks of target sentence types were trials of other sentence types such as relative clause and pivot construction.

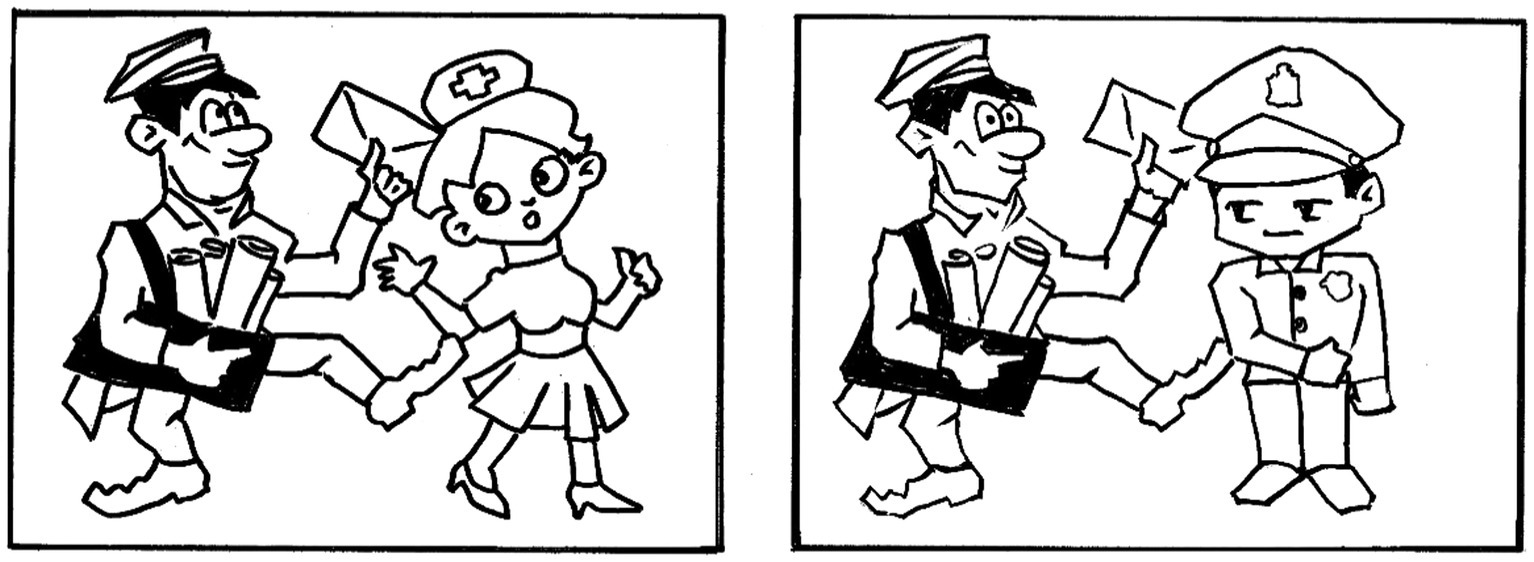

A prime picture and a target picture were created for each prime and target sentence, respectively. Figure 3 shows the pictures for sentences in (8). The two pictures appeared side by side on the screen. The prime picture was always on the left, while the target picture was always on the right.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Procedure of the comprehension task

In the comprehension task, children were requested to listen to a recorded test sentence and then point to the picture which best illustrated what they heard. They first had two trials for practice with feedback provided by the experimenter. Afterward, they went through the 18 test sentences in a randomized order. The task reported in the present paper was part of a larger study. The full testing list was composed of 27 sentences. Nine sentences contained constructions (relative clause and pivot construction) not relevant to the present study and were intermixed with the 18 test sentences.

The test sentences were played and the pictures were presented on a laptop using the E-prime software. When children chose a picture, they pushed the corresponding button. Thus, children’s responses were automatically recorded by the software.

2.3.2. Procedure of the production task

In the sentence production task, children saw two pictures along with the experimenter. They were requested to listen to the experimenter talking about what happened in the left picture. Then, their task was to describe what happened in the right picture. In each trial, the experimenter first pointed to each character and named them (e.g., “This is a mailman and this is a nurse. This is a mailman and this is a policeman.”) to ensure that children had no problem with expressing the noun phrase. Then, the experimenter described the left picture with the prime sentence, and afterward asked children what happened in the right picture. In practice trials, if children could not produce the target sentence, the experimenter modeled the target sentence and asked children to repeat it. In test trials, the experimenter only said the prime sentence once. If children asked about the characters, the experimenter reminded them about the noun phrases. Children’s production throughout the task was audio-recorded.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the comprehension task

3.1.1. Coding

We coded a response as correct when participants chose the Target picture. When participants did not choose the Target picture, the response was coded as an error. Errors were classified into three types: Reverse, Wrong Agent, and Wrong Patient based on which distractor was chosen.

3.1.2. Accuracy

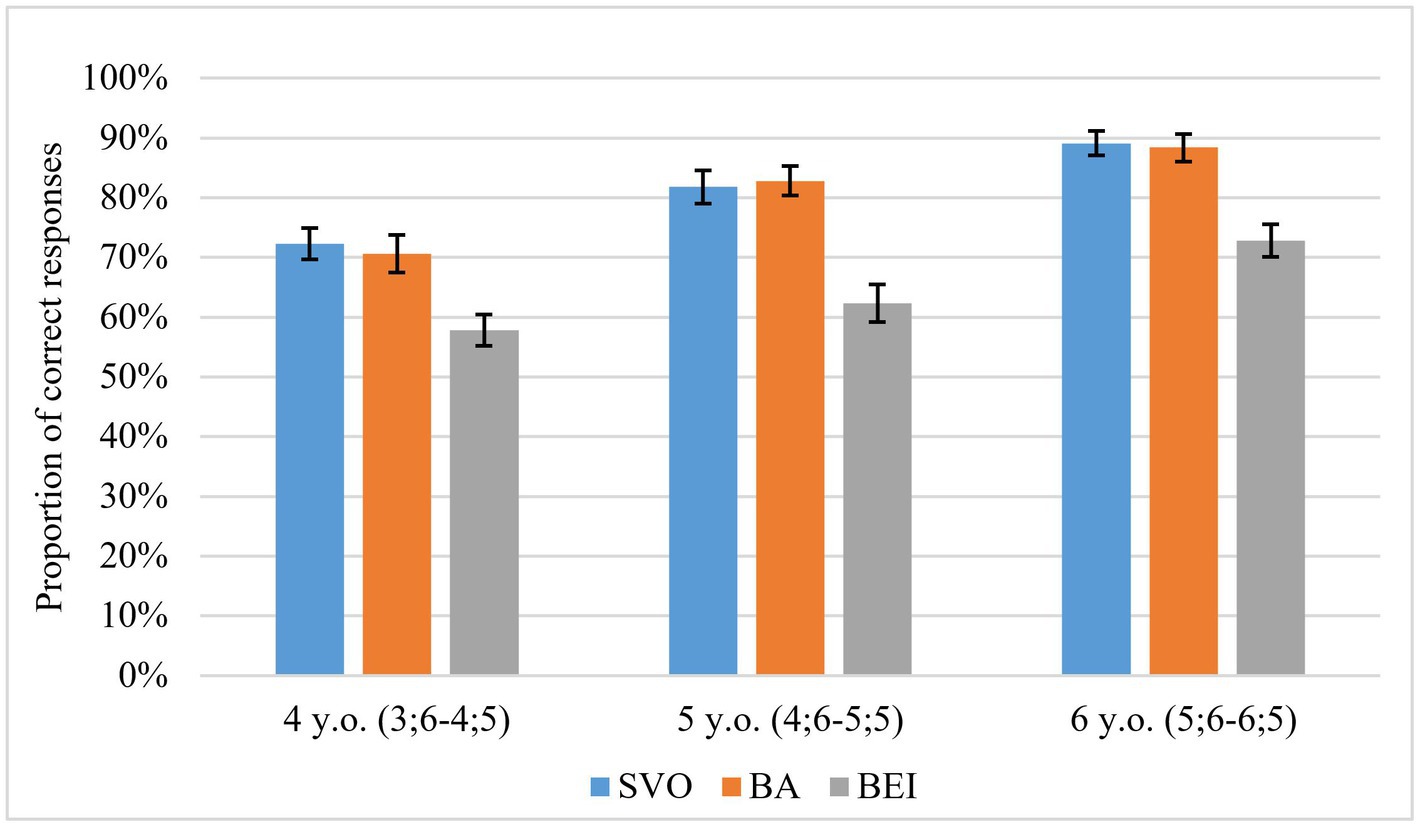

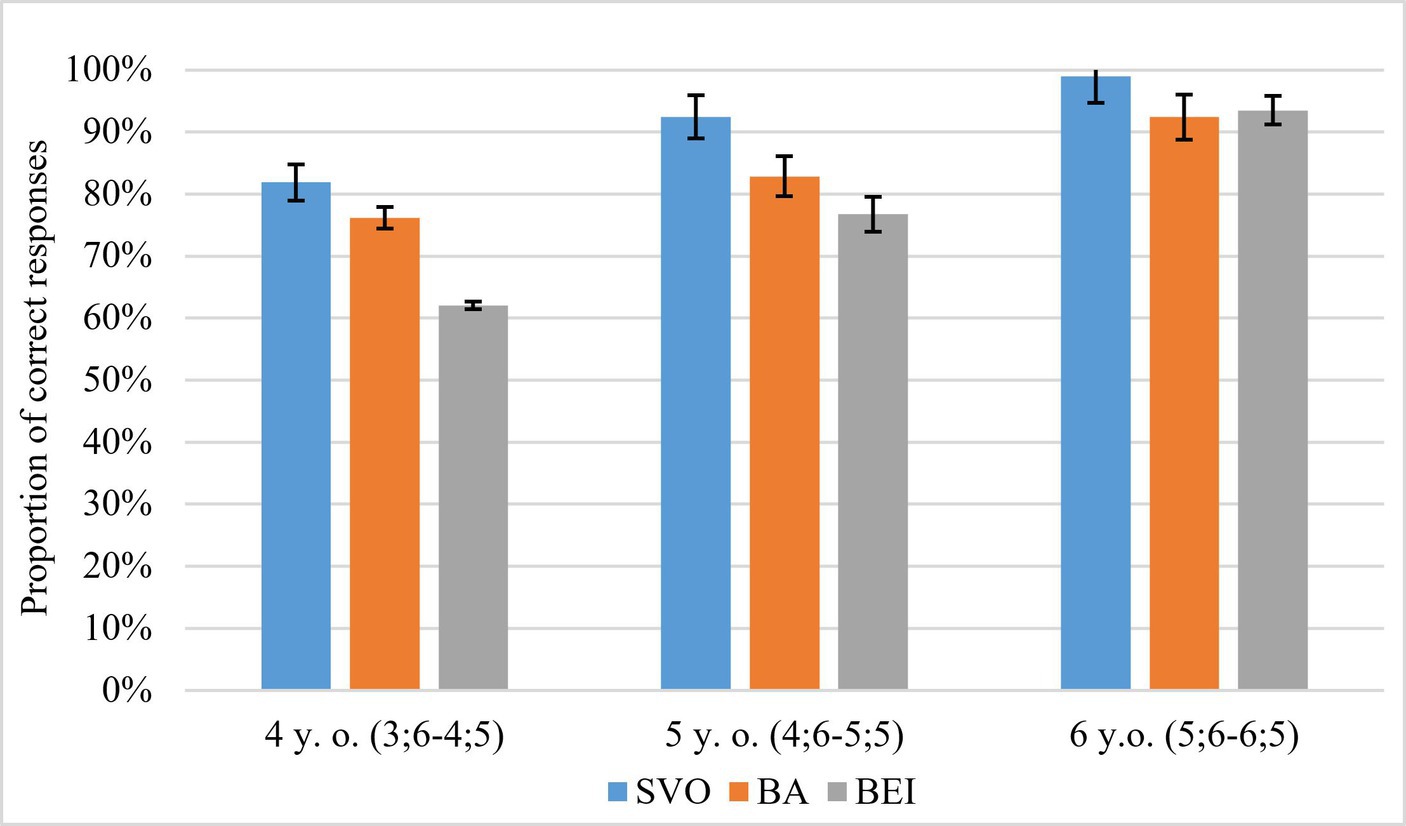

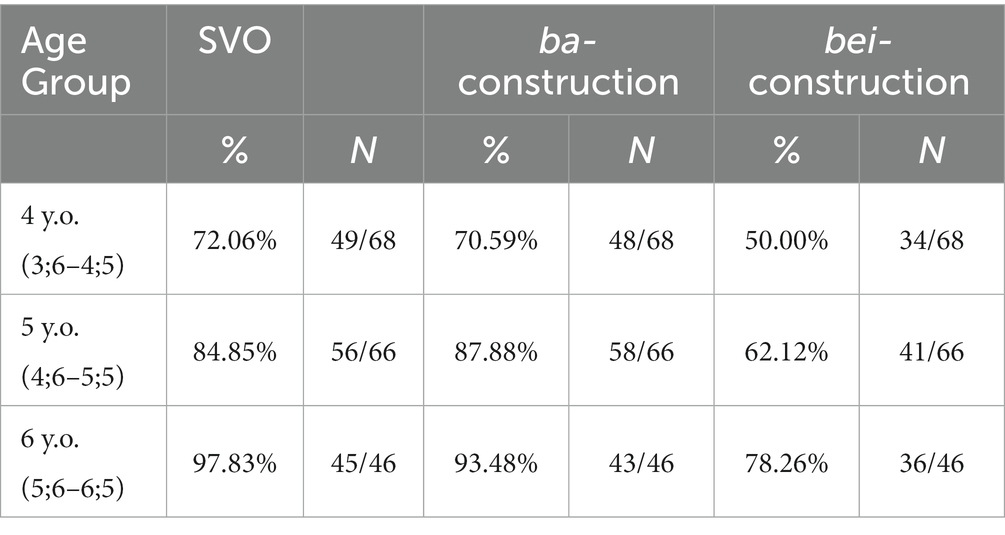

The descriptive results in Figure 4 show that the proportion of correct responses increased with age. Children comprehended the passive bei-construction less accurately than SVO or ba-construction.

The binary accuracy data were analyzed using multi-level mixed logit modeling with crossed random intercepts for Subjects and Items (Baayen, 2008; Baayen et al., 2008; Barr, 2008). Based on the guidelines in Barr et al. (2013, p. 275) and follow-up suggestions in Barr (2013, p. 1), we included random slopes for the two within-subjects factors Sentence Type and Sentence Length when building models incrementally. However, models that included a random slope did not converge. Therefore, we kept only random intercepts in our final model. The same treatment of random slopes can be found in other psycholinguistic work (e.g., Kuhn et al., 2021; Lee and Kaiser, 2021). All models were fit using glmer function of the lme4 package in R Project for Statistical Computing (R-Core-Team, 2012).

Since our SVO and ba-construction trials involved the same verbs and noun phrases in the test sentences, as well as the same picture stimuli, we first checked whether the order between trials of the two sentence types affected children’s performance. Overall, trials of ba-construction appeared 49.3% of the time before their SVO counterparts (i.e., the SVO sentence that had the same verb and noun phrase as the ba sentence) and 50.7% of the time after their SVO counterparts. Children’s accuracy of comprehending either sentence type did not differ between the two orders (all ps > 0.50). Therefore, the order between trials of SVO and ba-construction was not considered in further analysis.

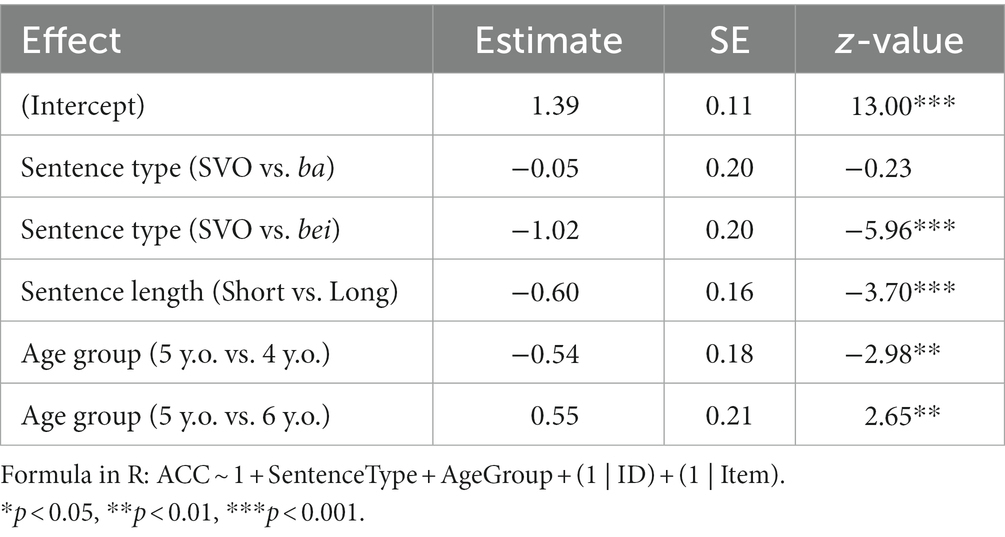

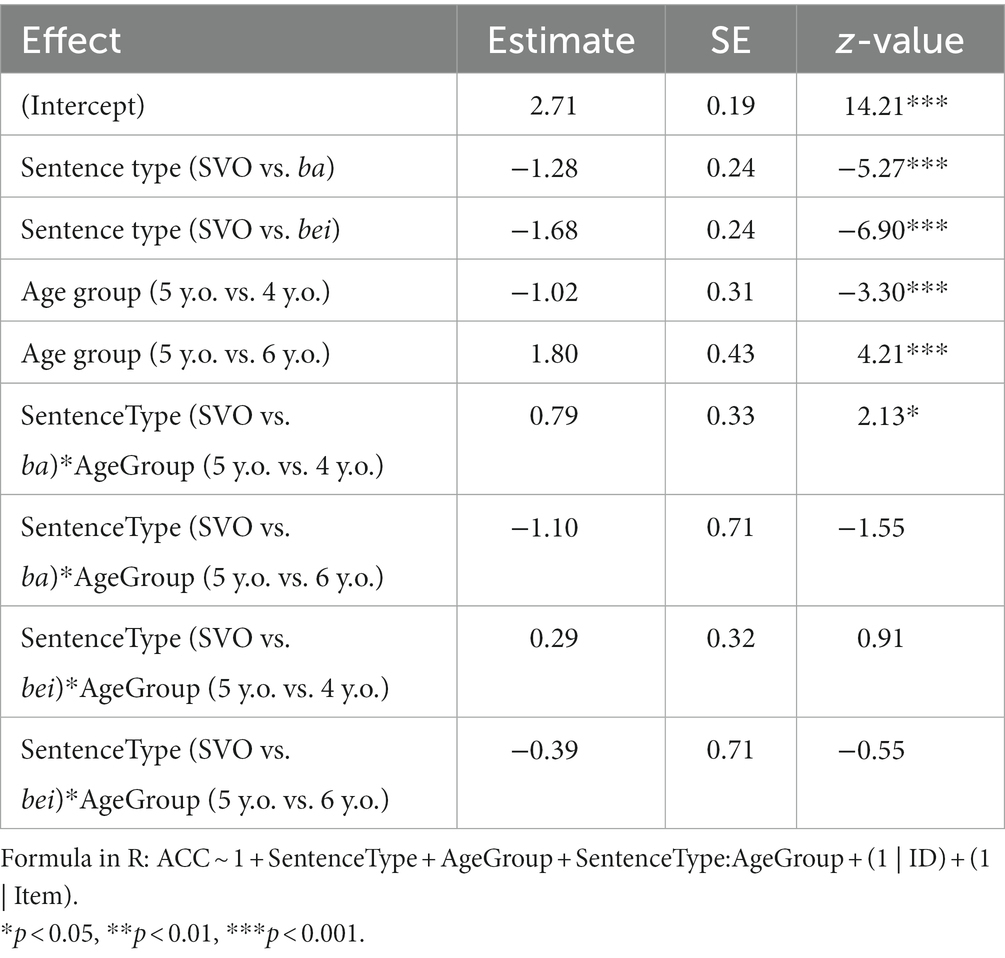

We examined the fixed effects of Age Group (4 y.o. vs. 5 y.o. vs. 6 y.o.), Sentence Type (SVO vs. ba-construction vs. bei-construction), and Sentence Length (Short vs. Long) as well as their interactions. The fixed effect of Age Group was analyzed with planned comparisons using simple contrast coding (c1: 0.66, −0.33, −0.33, c2: −0.33, −0.33, 0.66), which set the 5-year-old group as the reference group. Sentence Type was also analyzed with simple contrast coding (c1: −0.33, 0.66, −0.33, c2: −0.33, −0.33, 0.66), which compared comprehension of ba-construction and that of bei-construction to that of SVO (default word order in Mandarin). The fixed effect of Sentence Length was coded with centered contrast (−0.5, 0.5) and thus, the beta estimate could correctly represent the difference between short and long Sentences. We built up our logit model in a bottom-up fashion: factors of interest (Age Group, Sentence Type, and Sentence Length), a non-theoretically driven predictor Gender, and their interactions were added incrementally to the model to see whether the model fit was improved. Model fit was assessed by Chi-square tests on the log-likelihood values of competing models with three indices, AIC, BIC, and logLik. Predictors or interactions did not reliably improve model fit were excluded from further analysis. The same strategy of model selection was applied to the following analyses. Table 1 reports the final model with parameter estimates of fixed effects.

The statistical analysis confirmed the descriptive results. We detected a significant effect of Sentence Type. Specifically, children’s comprehension of bei-construction was worse compared to SVO sentences (z = −6.96, p < 0.001), but there was no significant difference between children’s comprehension of ba-construction and SVO sentences (z = −0.23, p > 0.250). There was also a significant effect of Sentence Length such that children were better in comprehending shorter sentences than the longer ones (z = −3.70, p < 0.001). Four-year-olds showed worse performance compared with 5-year-olds (z = −2.98, p = 0.003), while 6-year-olds showed better performance than 5-year-olds (z = 2.65, p = 0.008). There was a clear development in children’s grammar across age.

We further looked into the difference between the three age groups by counting the number of passers in each age group. For each sentence type, our task had six trials; the probability of choosing the target picture at random was 25%. Based on the binomial distribution, it was extremely unlikely to give the correct response four times out of the six trials by chance (p = 0.03). Thus, we considered a participant who gave at least four correct responses among the six trials of a sentence type as a passer in comprehension of that sentence type. Results are shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Percentages (%) and numbers of participants who performed above chance in comprehending the three sentence types.

In all age groups, there were significantly more children whose comprehension of SVO and ba-construction was above chance level compared to comprehension of bei-construction (4 y.o.: Cochran’s Q = 11.11, df = 2, p = 0.004; 5 y.o.: Cochran’s Q = 18.50, df = 2, p < 0.001; 6 y.o.: Cochran’s Q = 10.31, df = 2, p = 0.006). This result indicates that the comprehension of passives was delayed.

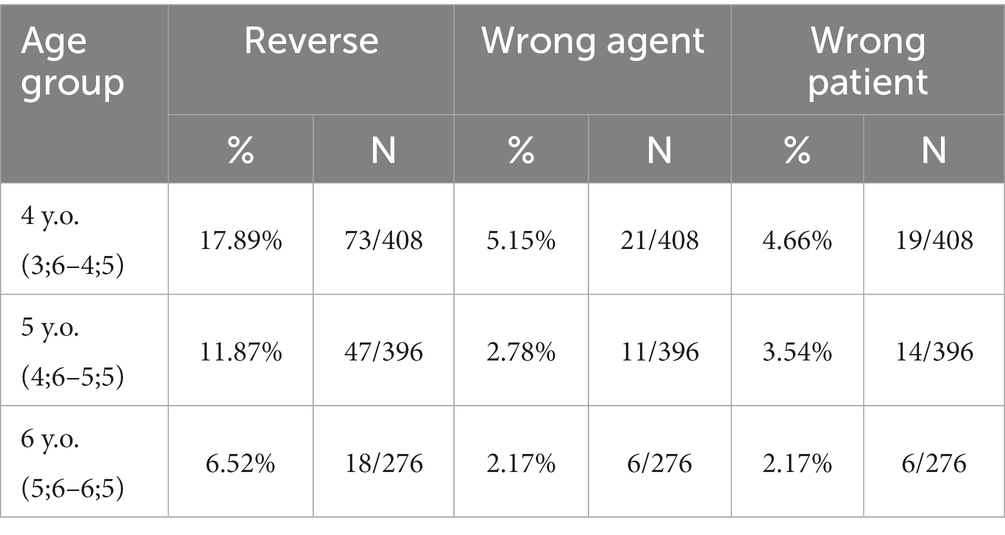

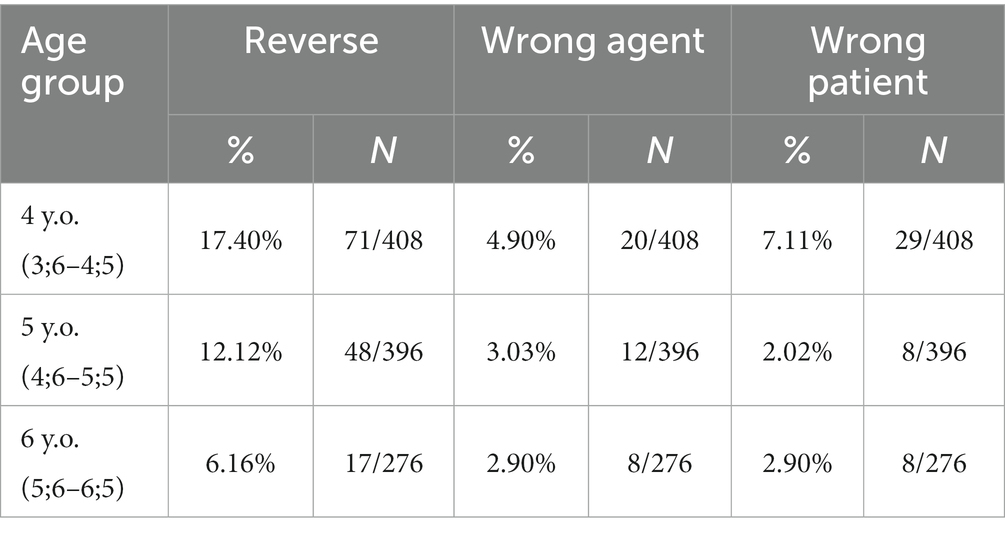

3.1.3. Error analysis

Children could make three types of errors: Reverse, Wrong Agent, and Wrong patient. Tables 3–5 illustrate the distribution of errors when children failed to choose the correct picture matched with the test sentence. Across the three sentence types, Reverse errors were more common compared to Wrong Agent and Wrong Patient errors.

Since we were interested in the distribution of different types of errors in each sentence type, the count data of each age group were separately further fit into a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson distribution and log link. The fixed effect of Error Type was analyzed with planned comparisons using simple contrast coding (c1: −0.33, 0.66, −0.33, c2: −0.33, −0.33, 0.66), which set the Reverse errors as the reference group. The crossed random intercept was provided for Subject. For all age groups, children made more Reverse errors in SVO comprehension than Wrong Agent and Wrong Patient errors (all ps < 0.05). A similar pattern was found in comprehension of ba-constructions. In both 4-year-old and 5-year-old groups, Reverse errors were more prevalent compared to the other two error types (all ps < 0.001). In the oldest group, the difference between Reverse errors and the other two types of errors approached significance (Reverse vs. Wrong Agent: z = −1.76, p = 0.08; Reverse vs. Wrong Patient: z = −1.76, p = 0.08). As for the bei-construction, Reverse errors were more frequent compared with the other two types of errors (all ps < 0.001) in all age groups.

3.1.4. A summary of the comprehension results

Our results illustrate a clear developmental pattern where children’s comprehension of the three sentence types showed a significant improvement between 3;6 and 6;5. As in previous studies (e.g., Chang, 1986; Liu and Ning, 2009; Zeng et al., 2016), we detected delayed acquisition of the passive bei-construction. By contrast, though ba-construction also involves a non-canonical word order, it did not cause more difficulties for children compared to the canonical SVO word order. This pattern cannot be explained under a usage-based account given the lower frequency of ba sentences than SVO sentences; it supports the current syntactic account—the formation of bei-construction requires an operator movement out of the vP phase (Huang, 1999), which seems not to be accessible to young children.

When children failed to map the meaning of a sentence with the correct picture, they in most cases could still pick out the correct animals denoted by the noun phrases in the sentence. but they ignored the thematic relationship between the animals. Interestingly, this type of errors was the most common across the board, regardless of sentence types. It suggests that some extra-linguistic factors could play a role in children’s performance. Specifically, to succeed in the task, children had to maintain their attention, hold the test sentences in memory, and suppress the tendency to select the Reverse picture with correct animals but a wrong thematic relation. Future research needs to take children’s cognitive abilities such as working memory and executive functioning into consideration.

3.2. Results of the production task

3.2.1. Reliability

Children’s responses were transcribed from the audio recordings by three research assistants who are native speakers of Mandarin. To ensure that the responses were transcribed accurately, we randomly chose 10% of the recordings and asked an additional listener to transcribe. The reliability of transcription measured as the proportion of identical transcriptions (by the additional listener and by the RAs) on a word-by-word basis was 95.4%. Discrepancies (mainly in transcriptions of unintelligible utterances by the youngest group) were resolved by the additional listener and the RAs through discussion.

3.2.2. Coding

We coded a response as correct when it satisfied the following requirements. First, the sentence type was the same as the prime sentence. For production of the bei-construction, we allowed using gei “give,” jiao “let,” and rang “allow” instead of bei since all these verbs are alternative morphemes that mark passives. Second, the response was a complete sentence. Specifically, we only allowed the omission of subject since Mandarin is a pro-drop language. Missing the target noun phrase (i.e., the object noun phrase in SVO sentences, the noun phrase after ba in ba-construction, and the noun phrase after bei in bei-construction), the verb, or the aspect marker was regarded as an incomplete sentence. We allowed participants to give slightly different NPs (e.g., a response like baobao tian-le shushu “the baby licked the uncle” was coded as correct though the target NP was baba “dad” instead of shushu “uncle”). Third, the word order was correct such that the thematic relation between the agent and the patient was matched with the picture.

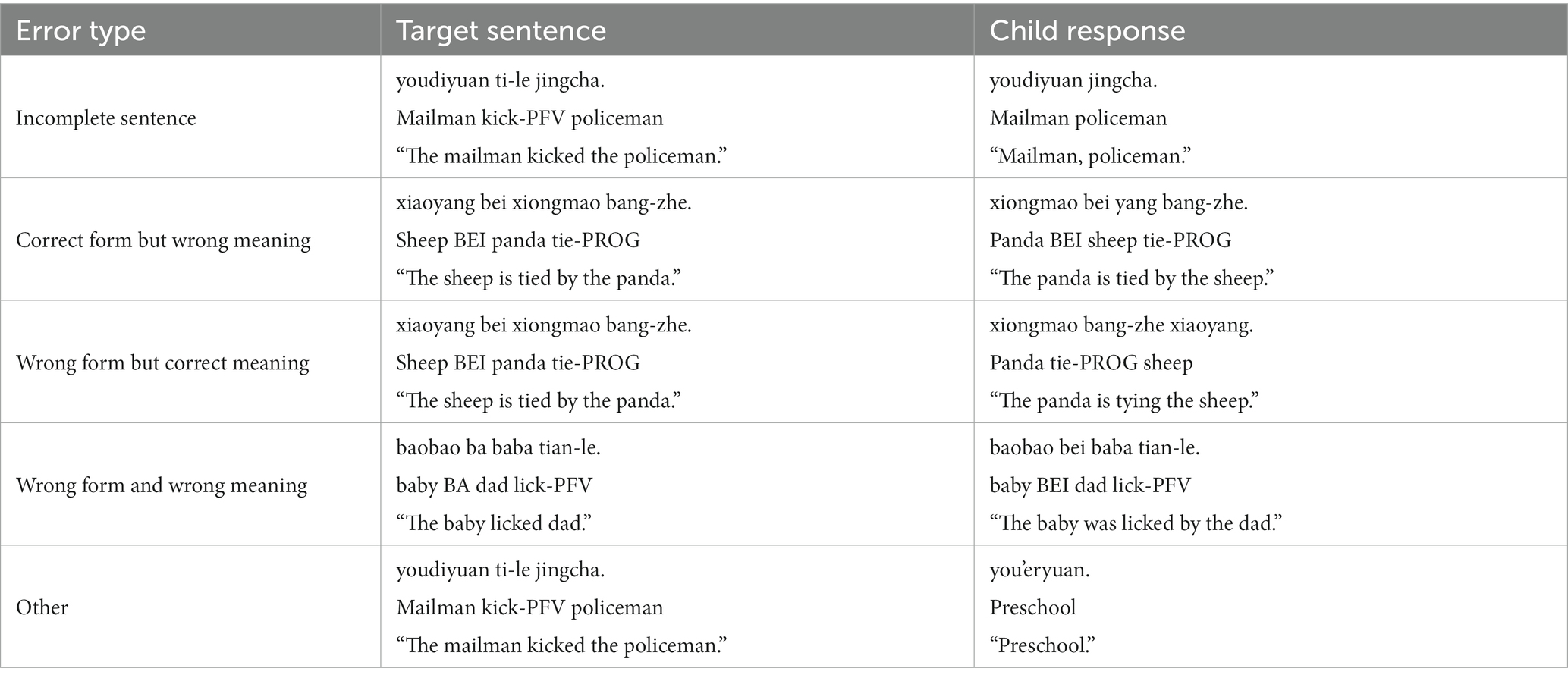

All other responses were coded as errors, which were divided into five types: Incomplete Sentence, Correct Form but Wrong Meaning, Wrong Form but Correct Meaning, Wrong Form and Wrong Meaning, and Other. Incomplete Sentence referred to responses that omitted any of the above-mentioned required elements but included at least one of the required elements. Correct Form but Wrong Meaning meant that the response had the same sentence type as the prime sentence, but the target noun phrase appeared in the wrong place such that the thematic relation was reverse. Wrong Form but Correct Meaning meant that the participant did not use the same sentence type as the prime sentence while the meaning was matched with the picture. Wrong Form and Wrong Meaning meant that the sentence type was not the same as the prime sentence, meanwhile the thematic relation was reverse. The Other category included responses that did not belong to the first four categories as well as unintelligible responses. Table 6 below provides examples illustrating each type of errors.

Compared to studies that coded responses based on whether the primed structure was used (e.g., Huttenlocher et al., 2004) or directly categorized responses based on their sentence type (e.g., Hao and Chondrogianni, 2021), our coding and classification of errors could help us better analyze cases when children did not produce the primed sentence type. Particularly, incomplete sentences and sentences that did not correctly describe the target picture were not trivial cases and an analysis of these errors can provide insights into children’s struggles with the meaning vs. form of different sentence types.

3.2.3. Accuracy

The descriptive results in Figure 5 show that children produced the most target SVO sentences and the least target passive bei-constructions; the performance on ba-construction was in between. Older children tended to produce more target sentences than younger children.

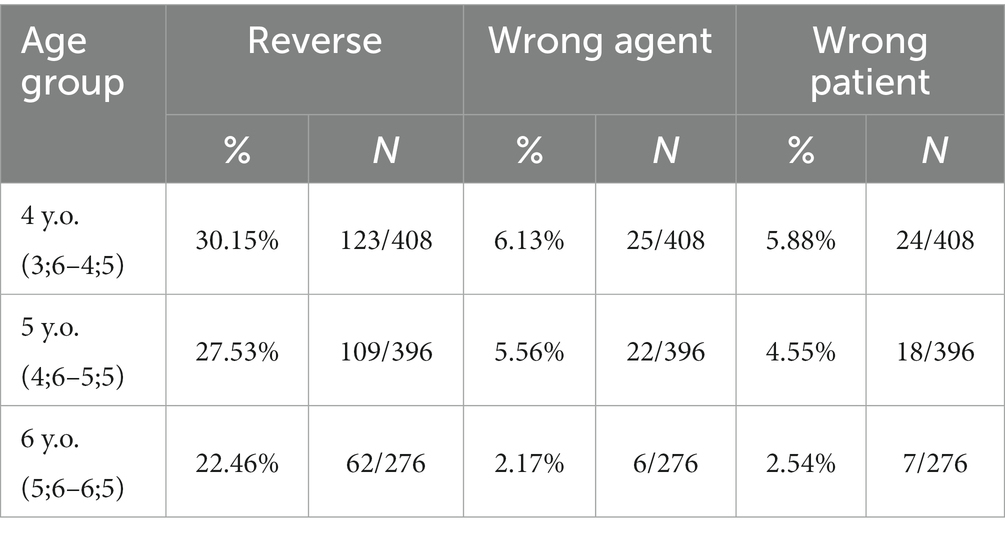

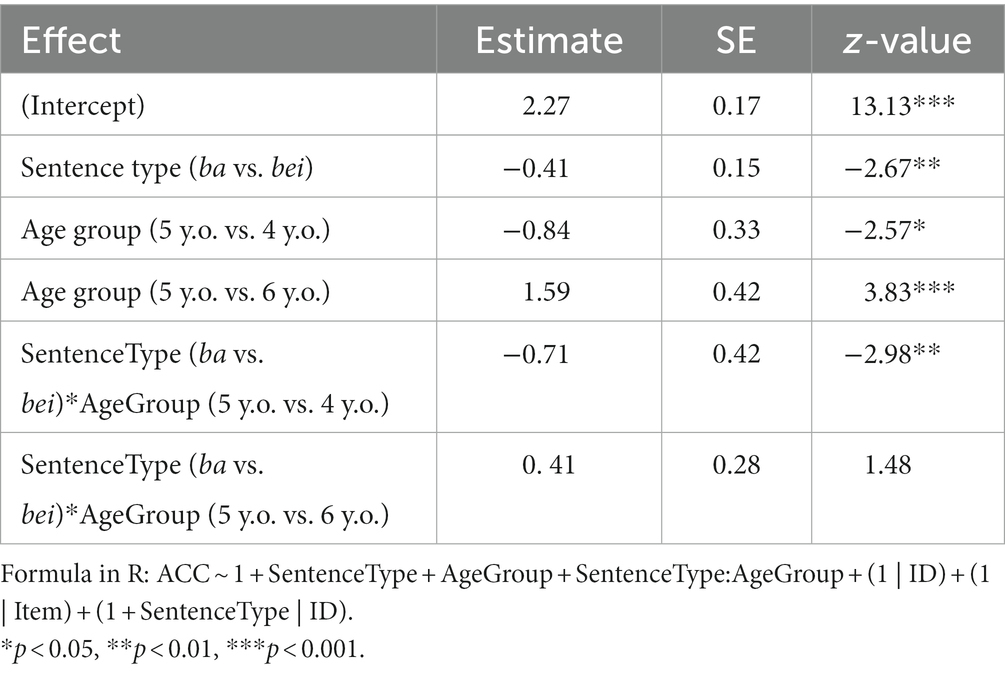

We examined the fixed effects of Age Group (4 y.o. vs. 5 y.o. vs. 6 y.o.), Sentence Type (SVO vs. ba-construction vs. bei-construction), and their interactions. The fixed effect of Age Group was analyzed with planned comparisons using simple contrast coding (c1: 0.66, −0.33, −0.33, c2: −0.33, −0.33, 0.66), which set the 5-year-old group as the reference group. The fixed effect of Sentence Type was analyzed the same way and coded as (c1: −0.33, 0.66, −0.33, c2: −0.33, −0.33, 0.66), which compared comprehension of ba-construction and of bei-construction to that of SVO sentences. We also considered whether the three orders of different sentence types (“SVO-bei-ba,” “ba-SVO-bei,” “SVO-ba-bei”) had an effect on children’s performance. The three levels of the Order factor were dummy coded. The binary accuracy data were first submitted to a mixed logit model with Order as a predictor and random intercepts for each Subject and each Item. Other factors of interest and interactions were added incrementally. It turned out that neither Order nor its interaction with other factors significantly improved the model fit (p > 0.250), suggesting that trials of one sentence type had little influence on performance in trials of another type. The Order factor was thus excluded from the final model. Table 7 reports parameter estimates of fixed effects.

The statistical analysis confirmed the descriptive results. There was a significant effect of Sentence Type. Specifically, children produced fewer target sentences of bei-construction compared to SVO sentences (z = −6.90, p < 0.001); they also produced fewer target sentences of ba-construction compared to SVO sentences (z = −1.28, p < 0.001). We also detected the fixed effect of Age Group. Four-year-olds had worse performance compared with 5-year-olds (z = −1.02, p < 0.001), whose performance was, in turn, worse than 6-year-olds (z = 2.65, p < 0.001). There was a clear development in children’s grammar across age. Last, a significant interaction between Sentence Type and Age Group was found (z = 2.13, p = 0.033): specifically, 4-year-olds did not differ in their production of SVO and ba-construction (odds ratio = 1.56, p = 0.061), but the older age groups had a better performance on SVO sentences compared to ba-constructions (5 y.o.: odds ratio = 3.12, p < 0.001; 6 y.o.: odds ratio = 9.14, p = 0.002).

Unlike comprehension, there was a difference in children’s production of ba-construction and SVO sentences. Therefore, we further compared the production of bei-construction and ba-construction. Again, the order between the ba and bei blocks was first examined and excluded since it did not improve the model fit. The accuracy data of ba- and bei-constructions were submitted to a mixed model with Age Group (4 y.o. vs. 5 y.o. vs. 6 y.o.) and Sentence Type (ba-construction vs. bei-construction) as predictors. As shown in Table 8, there was a fixed effect of Sentence Type, i.e., children produced more target ba sentences than target bei sentences (z = −2.67, p = 0.007). A fixed effect of Age Group was detected: six-year-olds outperformed five-year-olds (z = 3.83, p < 0.001), who, in turn, outperformed 4-year-olds (z = −2.56, p = 0.01). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between the two predictors (z = −2.98, p = 0.004). To interpret the interaction, we used emmeans package in R (Lenth, 2020) to compute pairwise comparisons to examine the effect of Sentence Type in each age group. It turned out that only the youngest group had better performance on ba-construction than bei-construction (odds ratio = 2.51, p < 0.001); 5-year-olds and 6-year-olds did not differ between the two sentence types (5 y.o.: odds ratio = 1.66, p = 0.140; 6 y.o.: odds ratio = 0.82, p > 0.250).

Table 8. Fixed effect estimates for multi-level model of the production of ba- and bei-constructions.

3.2.4. Error analysis

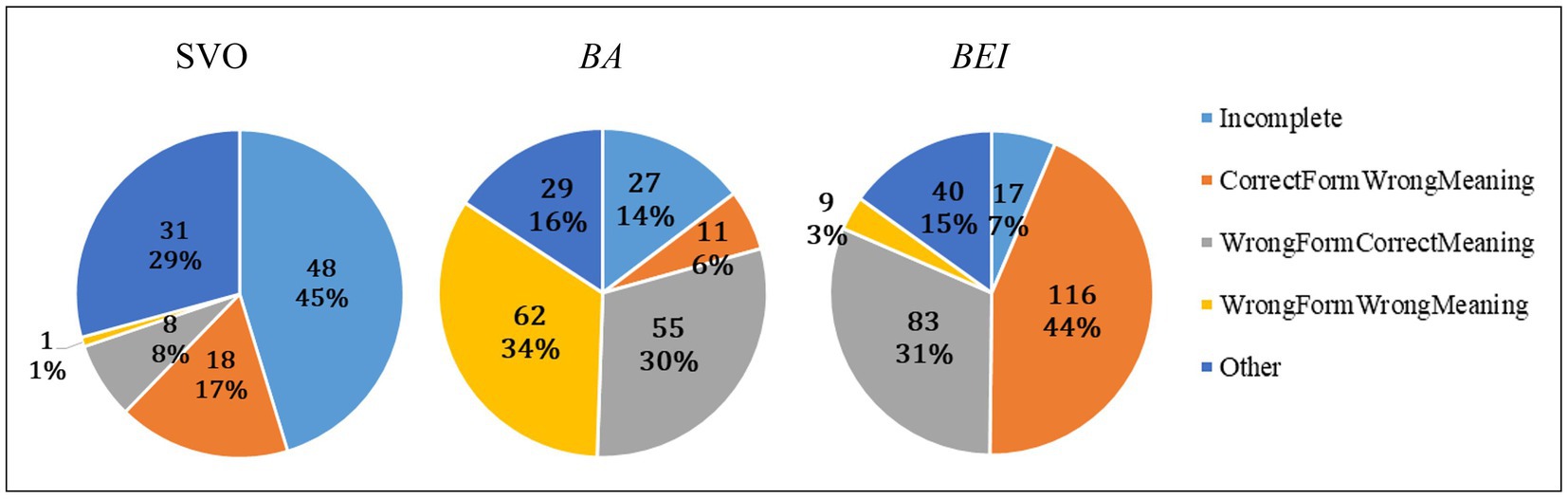

Five types of errors were detected: Incomplete Sentence, Correct Form but Wrong Meaning, Wrong Form but Correct Meaning, Wrong Form and Wrong Meaning, and Other. Figure 6 shows the counts and proportions of different types of errors. We collapsed data of the three age groups since some types of errors were very rare and the performance of the oldest group was almost at ceiling. From the first sight, the distribution of different types of errors varied greatly across the three sentence types. We further analyzed errors for each sentence type separately.

The counts of errors were submitted to a generalized linear mixed model with a Poisson distribution. The fixed effect of Error Type was analyzed with planned comparisons using deviation coding that compared the count of one type of errors to the overall mean of errors. The crossed random intercept was provided for Subject. By including the variation in subjects, the model evaluates whether a type of errors was scattered across many children or was found in just a few children. The random slope was also included since it significantly improved the model fit. This suggests that different subjects have different error distributions.

For SVO sentences, the most frequent errors were of the Incomplete-Sentence type, which were significantly more common than average (z = 5.70, p < 0.001). Among the 48 incomplete responses, 27 included the target noun phrase only while the verb and aspect marker were missing (see the first example in Table 6); 16 had the verb and aspect marker but the target noun phrase was missing; 5 had the verb and the target noun phrase, but the aspect marker was missing.

As for ba-construction, the most frequent errors were classified as Wrong Form and Wrong Meaning. Specifically, ba was replaced by the passive morpheme bei or gei, resulting in a non-target form and a reverse thematic relationship (see the fourth example in Table 6). However, such errors were not significantly more common than average (z = −1.53, p = 0.125). In fact, this type of errors was uncommon, as indicated by the negative Z value. Such errors were found in only 23 out of 180 participants, among which 13 children replaced ba with a passive morpheme in 1 or 2 trials and 10 children did so in at least 3 trials. In other words, a small group of children used the passive morpheme rather than ba. This was not caused by a perseveration from completing the block of bei-construction first, since 15 out of the 23 participants encountered the ba block first. It was not due to potential influence from dialects other than Mandarin either—9 out of 23 children had a parent speaking a southern dialect such as Shanghai dialect which does not allow replacement of ba with other morphemes, 13 children had both parents speaking Mandarin only, and one child had parents speaking a Northeast dialect. At present, we could not provide an explanation for this pattern. The second most frequent errors were of the Wrong-Form-but-Correct-Meaning type, which were more common than average (z = 4.39, p < 0.001). Among the 55 instances of such errors, 49 were SVO sentences and 6 were passive sentences with a passive morpheme bei or gei.

As for the production of bei-construction, the most frequent errors belonged to the type of Correct Form but Wrong Meaning. Such errors were more common than average (z = 6.16, p < 0.001). Although the passive structure was the same as the prime sentence, the two noun phrases appeared in a wrong order, thus the agent-patient relationship was reverse (see the second example in Table 6). Similar to ba-construction, the second most frequent errors involved Wrong Form but Correct Meaning, which were more common than average (z = 4.82, p < 0.001). Among the 83 instances of such errors, 54 were SVO sentences and 29 were ba-constructions.

3.2.5. A summary of the production results

Similar to the results of sentence comprehension, children’s production showed significant improvement between 3;6 and 6;5. Performance of the oldest group was nearly at ceiling. However, unlike comprehension, the youngest children produced significantly less target ba-constructions than SVO sentences. This suggests that although non-canonical word order does not necessarily lead to delayed comprehension, it may cause some difficulties in early production. In addition, children had different problems with producing ba- and bei-construction. Unlike earlier reports from naturalistic studies that 4-year-olds were productive and almost adult-like in using the ba-construction, we found considerable instances where children switched to the canonical SVO word order rather than producing ba sentences. As for bei-construction, our results showed that though children could be primed on the passive structure, they made many errors in the agent-patient relationship and seemed to confuse the structure with active sentences.

4. Discussion

Our results illustrated clear development of Mandarin-speaking children’s syntactic knowledge from 3;6 to 6;5. Specifically, as children grew older, they became better at understanding and producing non-canonical ba and bei sentences. Both non-canonical word orders caused some difficulties for children compared to the canonical SVO sentences. In comprehension, children made more errors in understanding bei sentences though their performance on ba-construction and SVO sentences did not differ. In production, children achieved high accuracy in producing target SVO sentences, but they produced less target ba sentences and even less target bei sentences.

4.1. Early difficulties with the passive Bei-construction

Our study showed delayed acquisition of the passive bei-construction—even 6-year-olds made considerable errors in both tasks, and this finding is in line with previous research (e.g., Chang, 1986; Liu and Ning, 2009; Zeng et al., 2016). Furthermore, we identified the major errors in Mandarin-speaking children: they tended to regard passives as active sentences and this resulted in a reverse agent-patient relationship in both comprehension and production. This pattern is consistent with what has been found in English-speaking children (e.g., Pinker et al., 1987; Gordon and Chafetz, 1990; Brooks and Tomasello, 1999; Messenger et al., 2012b; cf. Armon-Lotem et al., 2016) and provides evidence for the universality of Wexler’s (2004, 2007) proposal, i.e., movement from the object position out of the vP phase is not available in immature grammar due to a lack of knowledge about defective v.

However, there is a challenge for attributing children’s difficulties with bei-construction solely to the maturation of grammar. The maturation account would predict more “categorical” performance—before knowledge about defective v matures, children should have very poor performance with bei sentences. After the knowledge becomes available, there should be a remarkable boost in children’s performance. Our cross-sectional comprehension and production data both show gradual improvement across age groups in bei-construction, which poses questions about what actually drives this improvement. In effect, gradual development of a syntactic construction is expected by the usage-based account - as children grow older, they have more exposure to bei-sentences and their performance becomes better due to their familiarity with the construction. To tease apart the contribution of syntactic knowledge and construction frequency, future research can compare the acquisition of bei-construction with a construction that is equally rare in the input but does not involve long-distance movement out of vP. Future studies may also utilize a longitudinal design to better capture at which point children’s knowledge of long-distance movement matures.

4.2. Acquisition of Ba-construction

Our study also presented a comprehensive picture of the acquisition of ba-construction. In comprehension, no difference between ba and SVO sentences was detected. This may be taken as direct support for the maturation account which assumes that movement within the vP phase is available from the beginning. However, in the comprehension task, children could take some simpler strategy without processing the sentence structure. For instance, upon hearing the first noun phrase, they quickly associate it with the agent since the first argument of a sentence typically takes an agent role in their language (Yang et al., 2003); then they assign the patient role to the second noun phrase they hear. This possibility would be compatible with predictions from cue-based competition models (e.g., Bates and MacWhinney, 1987, 1989) which proposed that word order is a more reliable cue compared to morphological markers such as the passive –en in English (e.g., MacWhinney et al., 1984) and ba in Mandarin (Li et al., 1993). To evaluate this alternative explanation, future research may collect online processing data such as eye gaze patterns that can reveal how children arrive at the correct interpretation. Specifically, if children simply map arguments to thematic roles based on their order, then ba sentences should be processed at a faster speed since the second noun phrase appears earlier compared to SVO sentences. But if children comprehend sentences by analyzing the syntactic structure, then ba sentences might need more time due to the movement operation.

In contrast to comprehension, children’s production of ba-construction was worse than SVO sentences. On the one hand, a small group of children have replaced ba with a passive morpheme; for 80.65% of these cases, gei was used. Though at present we cannot provide an assured explanation to this pattern, historical and dialectal works on gei show that this morpheme, originally a ditransitive verb meaning “give,” has undergone grammaticalization and can be used as an agent marker like bei or as a patient marker like ba at least in Beijing dialect (Xu, 1994; Her, 2006). Further studies are needed to elucidate what children mean in their use of gei. On the other hand, children tended to change a ba sentence into a canonical SVO sentence. Remember that our paired prime and target sentences differed only in one component (i.e., the object NP in both ba and SVO sentences). To successfully produce a target ba sentence, children had to retain the ba morpheme and the verb in their working memory and insert the new object NP in between. By contrast, producing an SVO sentence without ba and a preverbal object was much less demanding. Future research may include some measurement of working memory capacity to better compare children’s production of ba and SVO sentences. In addition, the high frequency of SVO sentences may also lead to this pattern but the exact relationship between the frequency of a construction in the input and the likelihood of a child to use the construction remains to be explored.

4.3. Comparisons between Ba, Bei, and SVO sentences

Comparing between children’s performance on ba and bei sentences, our study revealed that children were better at comprehending ba-construction, which is expected by the maturation account, as well as the usage-based account since ba sentences are more frequent in child-directed speech than bei sentences. Unlike comprehension, only the youngest group had a better performance in the production of ba- than bei-construction. The finding that the older children performed comparably on ba- and bei-production cannot be explained under either the maturation or the usage-based account. It is possible that the production task may have encouraged the use of response strategies among the older children and masked their difficulty with bei- compared to ba-production—they may have taken the shortcut of simply replacing the second noun phrase in the target sentence without extracting the sentence structure. The literature on structural priming suggests that speakers start with a functional level of representation (i.e., linguistic expressions are encoded in terms of their grammatical functions such as subject, direct object; Garrett, 1980), which is mapped onto the specific structure of the prime sentence either in a separate step (see the two-stage model in Hartsuiker et al., 1999) or within the same stage (Pickering et al., 2002). In our production task, the functional representation was “half established” since the first noun phrase and the verb were exactly the same in paired prime and target sentences. In the future, harder priming tasks [e.g., using different lexical items in the target sentence as in Messenger et al. (2012a) and Hao and Chondrogianni (2021)] should be conducted among older children to better tap into their use of different sentence types. Particularly, performance of 5-year-olds and 6-year-olds is worth further investigation as Messenger et al. (2012a) have found that 6-year-old English-speaking children produced reversed passives, but Hao and Chondrogianni (2021) detected adult-like performance in 5-to-9-year-old Mandarin-speaking children.

Last but not least, our study showed some similarities and differences between children’s comprehension and production of the three sentence types. Performance in older children suggests that overall, the comprehension task was more difficult than the production task. At least two task-related factors may have caused this production advantage. First, each trial of the comprehension task was composed of four colored pictures, which differed minimally from each other in only one aspect. To succeed, children had to differentiate the pictures, and reject three distractors. By contrast, the production task had two black-and-white pictures differing in one figure in each trial. Unlike the comprehension task, the similarities between the two pictures could help children produce the target sentence. Second, the comprehension task used a totally randomized list such that the sentence type tended to vary from trial to trial. Children had to activate different syntactic representations throughout the testing. In comparison, in the production task, trials of the same sentence type were presented in one block. Children did not need to switch to a different syntactic structure before reaching a new block. Due to possible differences in task demands, at present, we cannot specify the relationship between comprehension and production apart from showing a strong positive correlation between children’s performance on both tasks (Pearson’s r = 0.490, p < 0.001). Future research needs to investigate what are shared and what may differ in language comprehension and language production, which is still a controversial issue (e.g., Chapman and Miller, 1975; Clark and Hecht, 1983; Håkansson and Hansson, 2000; Segaert et al., 2012). In effect, the maturation account is often supported by results from comprehension studies (for a summary of empirical studies, see Crain and Pietroski, 2002), while the usage-based account is discussed more with production data (for a review, see Abbot-Smith and Tomassello, 2016). A better understanding of the relationship may shed light on the debate between the two accounts of language acquisition.

5. Conclusion

Our study investigates the acquisition of Mandarin non-canonical word orders through a comprehension and a production task with a large sample of 180 Mandarin-speaking children between 3 and 6 years of age. Our results show that children have more difficulties with the passive bei-construction compared to SVO sentences in both comprehension and production, but early problems of ba-construction only lie in production. These findings contribute novel information on the development of Mandarin-speaking children’s syntactic knowledge from Age 3 to Age 6. On the one hand, our study provides insights into two major theories of language acquisition which attribute language development to the maturation of grammar or to the exposure to the input, respectively. On the other hand, our data present challenges to existing theories that call for future studies using a longitudinal design and/or online processing techniques.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/7ru43/, the “Acquisition of non-canonical word orders in Mandarin Chinese” project).

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

YJ performed data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LS was the principal investigator of the whole project on Mandarin preschool children’s language development and reviewed and edited the manuscript. LZ supervised the data collection process. All authors contributed to the study conceptualization and design, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the Beijing Institute of Technology Research Fund Program for Young Scholars (YJ), the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant 21CYY046; YJ), the Pu Dong One Hundred Award (LS), and the Humanities and Social Sciences projects of the Chinese Ministry of Education (Grant 17YJAZH132, LZ and LS).

Acknowledgments

We thank the children, parents, and teachers who participated. We also acknowledge the contribution of Catherine Hui-Yu Huang, Yiwen Zhang, and research assistants Shimei Zhang, Yimeng Mou, Rui Liu, Yaoyao Qin, Ran Gao, and Ru Peng at Nanjing Normal University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1006148/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PFV, perfective aspect marker, PROG, progressive aspect marker, PART, particle, BEI, passive morpheme bei, BA, disposal marker ba, IP, inflection phrase, CP, complementizer phrase, OP, operator,

References

Abbot-Smith, K., and Tomassello, M. (2016). Exemplar-learning and schematization in a usage-based account of syntactic acquisition. Linguis. Rev. 23, 275–290. doi: 10.1515/TLR.2006.011

Armon-Lotem, S., Haman, E., de López, K., Smoczynska, M., Yatsushiro, K., Szczerbinski, M., et al. (2016). A large-scale cross-linguistic investigation of the acquisition of passive. Lang. Acquis. 23, 27–56. doi: 10.1080/10489223.2015.1047095

Baayen, R. H. (2008). Analyzing linguistic data: A practical introduction to statistics using R. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., and Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 59, 390–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

Barr, D. (2008). Analyzing ‘visual world’ eyetracking data using multilevel logistic regression. J. Mem. Lang. 59, 457–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.09.002

Barr, D. J. (2013). Random effects structure for testing interactions in linear mixed-effects models. Front. Psychol. 4:e00328. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00328

Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C., and Tily, H. J. (2013). Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: keep it maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 68, 255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001

Bates, E., and MacWhinney, B. (1987). “Competition, variation, and language learning” in Mechanisms of language acquisition. ed. B. MacWhinney (Mahwah: Erlbaum), 157–193.

Bates, E., and MacWhinney, B. (1989). “Functionalism and the competition model,” in The cross-linguistic study of sentence processing. eds. B. MacWhinney and E. Bates (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 3–76.

Bender, E. (2000). The syntax of mandarin BA: reconsidering the verbal analysis. J. East Asian Linguis. 9, 105–145. doi: 10.1023/A:1008348224800

Borer, H., and Wexler, K. (1987). “The maturation of syntax,” in Parameter Setting. eds. T. Roeper and E. Williams (Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Co), 123–172.

Brooks, P. J., and Tomasello, M. (1999). Young children learn to produce passives with nonce verbs. Dev. Psychol. 35, 29–44. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.29

Bruening, B., and Tran, T. (2015). Vietnamese passives and the nature of the passives. Lingua 165, 133–172. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2015.07.008

Chang, H. W. (1986). “Young children's comprehension of the Chinese passives” in Linguistics, psychology and the Chinese language. eds. H. Kao and R. Hoosain (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press)

Chapman, R., and Miller, J. F. (1975). Word order in early two and three word utterances: does production precede comprehension? J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 18, 355–371. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1802.355

Chomsky, N. (2001). “Derivation by phase,” in Ken Hale: A Life in Language. ed. M. Kenstowicz (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 1–52.

Clark, E. V., and Hecht, B. F. (1983). Comprehension, production, and language acquisition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 34, 325–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.34.020183.001545

Crain, S., and Pietroski, P. (2002). Why language acquisition is a snap. The Linguistic Review 18, 163–183. doi: 10.1515/tlir.19.1-2.163

Deng, X., Mai, Z., and Yip, V. (2018). An aspectual account of Ba and bei constructions in child mandarin. First Lang. 38, 243–262. doi: 10.1177/0142723717743363

Garrett, M. F. (1980). “Levels of processing in sentence production” in Language production. ed. B. Butterworth (London: Academic Press), 177–220.

Goldberg, A. (2006). Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gong, S. (2007). 4-5 sui you’er baziju he beiziju jufa yishi fazhan de tedian [the patterns of 4-to-5-year olds’ developing syntactic awareness of Ba and bei sentences]. Jiaoyu Kexue [Education Science] 23, 92–94.

Gordon, P., and Chafetz, J. (1990). Verb-based versus class-based accounts of actionality effects in children’s comprehension of passives. Cognition 36, 227–254. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90058-R

Håkansson, G., and Hansson, K. (2000). Comprehension and production of relative clauses: a comparison between Swedish impaired and unimpaired children. J. Child Lang. 27, 313–333. doi: 10.1017/S0305000900004128

Hao, J., and Chondrogianni, V. (2021). Comprehension and production of non-canonical word orders in mandarin-speaking child heritage speakers. Linguis. Approach. Bilingual. doi: 10.1075/lab.20096.hao

Hao, M.-L., Shu, H., Xing, A.-L., and Li, P. (2008). Early vocabulary inventory for mandarin Chinese. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 728–733. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.728

Harris, F., and Flora, J. (1982). Children’s use of ‘get’ passives. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 11, 297–311. doi: 10.1007/BF01067584

Hartsuiker, R., Herman, H., Kolk, H., and Huiskamp, P. (1999). Priming word order in sentence production. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 52, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/713755798

Her, O.-S. (2006). Justifying part-of-speech assignments for mandarin gei. Lingua 116, 1274–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2005.06.003

Hsu, D. (2014). Mandarin-speaking three-year-olds’ demonstratin of productive knowledge of syntax: evidence from syntactic productivity and structural priming with the SVO-Ba alternation. J. Child Lang. 41, 1115–1146. doi: 10.1017/S0305000913000408

Huang, C.-T. J. (1999). Chinese passives in comparative perspective. TsingHua J. Chin. Stud. 29, 423–509.

Huang, C.-T. (2013). “Variations in non-canonical passives,” in Non-Canonical Passive. eds. A. Alexiadou and F. Schaefer (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 95–114.

Huang, C.-T. J., Li, Y.-H. A., and Li, Y. (2009). The Syntax of Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139166935

Huang, Y. T., Zheng, X., Meng, X., and Snedeker, J. (2013). Children’s assignment of grammatical roles in the online processing of mandarin passive sentences. J. Mem. Lang. 69, 589–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2013.08.002

Huttenlocher, J., Vasilyeva, M., and Shimpi, P. (2004). Syntactic priming in young children. J. Mem. Lang. 50, 182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2003.09.003

Kuhn, J., Geraci, C., Schlenker, P., and Strickland, B. (2021). Boundaries in space and time: iconic biases across modalities. Cognition 210:104596. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104596

Lee, S. H., and Kaiser, E. (2021). Does hitting the window break it?: investigating effects of discourse-level and verb-level information in guiding object state representations. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 36, 921–940. doi: 10.1080/23273798.2021.1896013

Lenth, R. (2020). Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package Version 1.4.6. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/packages/emmeans/index.html

Leonard, L., Deevy, P., Fey, M., and Bredin-Oja, S. (2013). Sentence comprehension in specific language impairment: a task designed to distinguish between cognitive capacity and syntactic complexity. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 56, 577–589. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0254)

Li, P. (1990). Aspect and aktionsart in child mandarin. [dissertation]. [Leiden]: Leiden University.

Li, Y.-M. (1995) Ertong Yuyan de Fazhan [the development of child language]. Wuhan: Central China Normal University Press.

Li, P., Bates, E., and MacWhinney, B. (1993). Processing a language without inflections: a reaction time study of sentence interpretation in Chinese. J. Mem. Lang. 32, 169–192. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1993.1010

Li, C. N., and Thompson, S. A. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. CA: University of California Press.

Li, X., Zhou, G., and Kong, L. (1990). 2-5 sui ertong yuyong baziju qingkuang de chubu kaocha [a preliminary exploration into 2-to-5-year-old children’s use of Ba sentences]. Yuwen Yanjiu [Linguistic Researches] 4, 43–50.

Liu, H.-Y, and Ning, C.-Y. (2009). “Phase impenetrability condition and the acquisition of unaccusatives, object-raising Ba-constructions, and passives in mandarin-speaking children,” In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA 2008), eds. J. Crowford, K. Otaki, and M. Takahashi (Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

MacWhinney, B., Bates, E., and Kliegl, R. (1984). Cue validity and sentence interpretation in English, German, and Italian. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 23, 127–150. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(84)90093-8

Messenger, K., Branigan, H. P., and McLean, J. F. (2012a). Is children’s acquisition of the passive a staged process? Evidence from six- and nine-year-olds’ production. J. Child Lang. 39, 991–1016. doi: 10.1017/S0305000911000377

Messenger, K., Branigan, H. P., McLean, J. F., and Sorace, A. (2012b). Is young children’s passive syntax semantically constrained? Evidence from syntactic priming. J. Mem. Lang. 66, 568–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2012.03.008

Pickering, M. J., Branigan, H. P., and McLean, J. F. (2002). Constituent structure is formulated in one stage. J. Mem. Lang. 46, 586–605. doi: 10.1006/jmla.2001.2824

Pinker, S., Lebeaux, D. S., and Frost, L. A. (1987). Productivity and constraints in the acquisition of the passive. Cognition 26, 195–267. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(87)80001-X

Segaert, K., Meneti, L., Weber, K., Peterson, K. M., and Hagoort, P. (2012). Shared syntax in language production and language comprehension. Cereb. Cortex 22, 1662–1670. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr249

Shi, D. (2005). “Bei” ziju de guishu [On “bei” passive in Chinese]. Hanyu Xuebao [Chinese Linguistics] 9, 38–48.

Sun, C. F. (1991). Transitivity and the BA construction. Paper presented at the 3rd North American Conference on Chinese linguistics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Tian, J. (2003). The Ba-construction in mandarin Chinese: A syntactic-semantic analysis. [masters thesis]. [Victoria]: University of Victoria.

Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a language: A usage-based theory of language acquisition. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press.

Wexler, K. (2004). Theory of phrasal development: perfection in child grammar. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 48, 159–209.

Wexler, K. (2007). Developing phases, verbal, resultant state and target passives, inverse copulas, clefts: the interaction of brilliant plasticity and genetically guided principles. Paper presented at GLOW-ASIA VI, Hong Kong.

Yang, C. L., Gordon, P. C., Hendrick, R., and Hue, C. W. (2003). Constraining the comprehension of pronominal expressions in Chinese. Cognition 86, 283–315. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00182-8

Yang, X., and Xiao, D. (2008). Xiandai hanyu baziju xide de ge’an yanjiu [a case study of the acquisition of Ba sentences in mandarin]. Dangdai Yuyan Xue [Contemporary Linguistics] 3, 200–210.

Zeng, T., Mao, W., and Duan, N. (2016). Acquisition of event passives and state passives by mandarin-speaking children. Ampersand 3, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amper.2016.01.002

Zhou, G. (1997). Hanyu Jufa JIegou Xide Yanjiu [studies on the Acquisition of Mandarin Syntactic Structures]. Hefei: Anhui University Press.

Zhou, J. (2001). Pragmatic development of mandarin speaking young children: from 14 months to 32 months [dissertation]. [Hongkong]: The University of Hong Kong. Available from HKU Theses Online (HKUTO).

Zhou, G., Kong, L., and Li, X. (1992). Ertong yuyan zhong de beidongju [passive sentences in child language]. Yuyan Wenzi Yingyong [Applied Linguistics] 1, 38–48.

Keywords: ba-construction, bei-construction, word order, language acquisition, Mandarin

Citation: Ji Y, Sheng L and Zheng L (2023) Acquisition of non-canonical word orders in Mandarin Chinese. Front. Psychol. 14:1006148. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1006148

Edited by:

Yang Zhang, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, United StatesReviewed by:

Shaohua Fang, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesJiuzhou Hao, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Norway

Copyright © 2023 Ji, Sheng and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yue Ji, aml5dWVAYml0LmVkdS5jbg==

Yue Ji

Yue Ji Li Sheng

Li Sheng Li Zheng

Li Zheng