- 1School of Management, Shenzhen Polytechnic, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

- 2School of Education, Shenzhen Polytechnic, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

This study explores the impact of customers’ value co-creation behavior on their experiences with and loyalty to P2P accommodations. We propose a theoretical model integrating two lines of tourism research: customer value co-creation and customer experience. To extract the dimensions of customer experience and test the proposed model, 34 in-depth interviews were conducted along with a survey of Chinese Airbnb users. Structural equation modeling and mediation analysis were implemented to assess relationships involving customers’ value co-creation behavior, experience, and loyalty. Results indicate that customer citizenship behavior directly influences loyalty. In particular, relationships involving customers’ participation behavior and citizenship behavior with loyalty are both mediated by customer experience. Relevant implications and future research opportunities are discussed.

Introduction

The customer experience represents a new form of post-service economic value, and many scholars have discussed its role in helping organizations gain a competitive advantage (Pine and Gilmore, 1998; Verhoef et al., 2009). In early studies of the customer experience, researchers generally defined experience from a utilitarian perspective with an emphasis on the functional value of experience (e.g., Abbott, 1955; Hauser and Urban, 1979). At that time, marketers maintained a goods-oriented mindset, positing that value is produced and embedded in goods through manufacturing processes and later destroyed by consumers. As goods and services become more commoditized, products and services that fulfill functional needs are no longer sufficient today; contemporary consumers’ demands go beyond the mere delivery and consumption of products and services as they seek “engaging, robust, compelling and memorable” experiences (Gilmore and Pine, 2002, p. 10).

Countering the goods-centered logic that has been well-established in management theory, Vargo and Lusch (2004) introduced the concept of service-dominant logic (SDL), which challenged the presumptions of mainstream marketing theory. According to SDL, customers are co-creators of value rather than targets of that value. Customers determine value in the consumption process, operating at the intersection of the service provider and customer (Lusch et al., 2007). SDL has risen to prominence as a new marketing perspective over the last decade to become a dominant narrative in collaborative marketing (Warnaby and Medway, 2015). The recent phenomenon of the collaborative economy exemplifies an exploration of SDL’s utility within a broader scope (Brodie et al., 2019). Hybridized production and consumption constitute the most salient feature of the collaborative economy (Cohen and Munoz, 2016).

Studies have shown that participation in collaborative consumption enables consumers to gain and maintain social relations emerging from sharing behavior (Belk, 2010). Interactions with hosts and local community members, coupled with active participation in co-creation activities, help elicit authentic, personalized, and memorable experiences (Mathisen, 2013). Sharing-business practitioners must therefore understand (a) which factors contribute to customers’ service evaluations and (b) how to engage customers in the value co-creation process. Only with this knowledge can service providers allocate resources effectively to achieve optimal return on investment.

Although the experiential nature of sharing accommodations has been widely studied (e.g., Guttentag, 2015; Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017), antecedents of the customer experience remain under-researched. Co-creation, which is widely considered conducive to memorable and unique customer experiences in tourism, is in the pre-theory stage and lacks empirical evidence (Chiadmi, 2014). Moreover, the customer’s role in co-creation has yet to be systematically examined in tourism research (Sugathan and Ranjan, 2019); scholars have called for additional studies examining how value is co-created (Busser and Shulga, 2018; Malshe and Friend, 2018). Value co-creation is viewed as an overarching component of collaborative consumption (Lusch et al., 2007), yet few studies have examined co-creation modalities in a sharing accommodation context. The question of which co-creation behaviors are most effective in creating higher-order customer experiences, and in turn fostering customer loyalty, must be answered.

This study attempts to fill these theoretical gaps by exploring the dynamics of customers’ value co-creation behavior and its impact on behavioral outcomes with a focus on the customer experience and loyalty in the context of sharing accommodation field. Specifically, we propose that customers’ value co-creation behavior determines customers’ perceptions of their experiences and thus influences their behavioral intentions. The research purposes of this study are (1) to examine the components which construct value co-creation behavior in the context of P2P accommodation, (2) to explore the experiential dimensions of customers’ perceptions of P2P accommodations, (3) to evaluate the influences of different value co-creation behaviors on customer experiences and loyalty, (4) to explore the mechanism of how value co-creation behavior exposes influences on customer loyalty, and (5) to provide insights and suggestions for sharing accommodation operators on how to improve guests’ experience and loyalty.

Theoretical background

Customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations

The P2P accommodation market is still in an early stage of development. Despite drastic growth within the past several years in terms of business and customer volume, little research has considered whether this shift has altered customers’ expectations and evaluations of accommodation services (Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017). As a new sharing-business mode, the services provided by P2P accommodations tend to be distinct from those offered at hotels. To better understand the factors differentiating P2P accommodations from long-established accommodation settings including hotels and B&Bs, scholars must explore the experiential dimensions that matter to customers when evaluating P2P accommodations.

Various studies (e.g., Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017; Guttentag et al., 2018; Lutz and Newlands, 2018; Tussyadiah and Pesonen, 2018; Zhu et al., 2019) have outlined dimensions of the customer experience in P2P accommodations, consisting of five major elements: the physical environment, service quality, guest-host relationship, peer guest interactions, and local cultural experience. These facets represent the primary dimensions of P2P accommodation experiences. Accordingly, customers’ evaluations of their P2P accommodation experiences (including their reflections upon relevant products and services) can be holistically captured in terms of cognition and affect.

The customer experience lies at the heart of the tourism industry, highlighted by a SDL that provides a conceptual framework delineating how the consumer has become pivotal to the development and marketing of tourism products through a process of co-creation with the producer (Shaw et al., 2011). Tourism operators have increasingly acknowledged the great extent to which visitors shape their own experiences (Mathisen, 2013). Moreover, an abundance of research has offered evidence of customers’ desire and demand to co-create experiences with service providers (e.g., Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004a; Im and Qu, 2017).

Many studies have explored motivational factors that drive customers to choose P2P accommodations (e.g., Guttentag, 2015; Tussyadiah and Pesonen, 2018), but few have examined the antecedents, consequences, and specific dimensions of the customer experience, particularly from a value co-creation perspective. As an emerging lodging market, P2P accommodations are quite different from the standard hotel market. Some studies have shown that B&B guests are particularly interested in uniqueness and novelty in their living experiences (Mcintosh and Siggs, 2005). Positive customer experiences and high customer satisfaction may not necessarily lead to customer loyalty. The interrelations among customer experience, perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty must therefore be re-examined in the P2P accommodation market.

Furthermore, most research on the sharing economy has been conducted from a Western perspective and in Western regions (Cheng, 2016). More attention should be paid to emerging areas that present unique group dynamics. Airbnb is reportedly facing barriers to growth in China (Nextunicorn, 2019), but scholars have not empirically determined whether cultural resistance is responsible for this phenomenon. Therefore, to further develop the Chinese P2P accommodation market, researchers must evaluate how Chinese customers perceive such services; consumers’ experiences and satisfaction are essential to providing actionable implications for investors, operators, and other stakeholders.

Customer value co-creation

The concept of value co-creation

The concept of value co-creation is closely related to the customer experience. Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004b) asserted that true co-creation occurs when firms provide “experience spaces” where dialogue, transparency, and information access enable customers to engage in experiences that suit their needs and level of involvement. Customers create self-tailored experiences and value by integrating their own resources including expertise, skills, abilities, and capabilities with the provider’s network and customer network resources.

The distribution and exchange of commodities and manufactured products have dominated the marketing domain since its birth at the start of the 20th century (Lusch et al., 2007). Under this goods-dominant logic, which focused on tangible resources, services were considered a type of product or value-adding enhancement to tangible products; value was thought to be created by firms and distributed to consumers (Lusch et al., 2007). Over the past few decades, marketing has evolved toward a new dominant logic as perspectives have begun to focus on intangible resources, relationships, and value co-creation. Vargo and Lusch (2004) introduced the concept of SDL, wherein the customer is a co-creator of value; an enterprise cannot deliver value but only participate in creating and offering value propositions.

Researchers have defined value co-creation from a customer perspective (e.g., Prebensen et al., 2014; Tuan et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2022) and an organization/destination perspective (e.g., Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004b; Li and Petrick, 2008). Essentially, value co-creation represents the process by which customers create value for themselves through interacting with the experience environment by integrating organization-provided resources with their own cultural, emotional, and physiological resources. Co-creation is particularly relevant to the tourism industry. This field has been conceptualized as a type of performance embedded in social praxis (Perkins and Thorns, 2001). Rather than being passive sightseers, tourists now wish to “roll up their sleeves” (Eraqi, 2010, p. 79) and take active roles in their travel activities physically, emotionally, and intellectually. The performance turn in tourism argues that tourists are hungry to do rather than simply see (Eraqi, 2010; Assiouras et al., 2019). For example, from a tourist viewpoint, information seeking and idea generation constitute pre-consumption co-creation of the travel experience.

Customers’ co-creation behaviors in the sharing-economy context

Co-creation activities have become a top priority in tourism research (Shaw et al., 2011), especially in the context of the sharing economy. SDL is thought to explain the growing popularity of sharing-economy businesses (Heo, 2016). This concept emphasizes the importance of customer–service provider interaction (Vargo and Lusch, 2004; Bu et al., 2022). In the sharing economy, social interaction is one of the most important factors motivating tourists to use P2P accommodation rentals (Tussyadiah and Zach, 2017; Tussyadiah and Pesonen, 2018). Tourists enjoy the sharing economy because they can create value by interacting with hosts and the local community; that is, today’s consumers prefer to be active partners in value creation. Heo (2016) identified the need for a more extensive theoretical explanation of SDL and value co-creation relative to the new business phenomenon of sharing.

As SDL implies, customers are the core of value creation and have assumed new roles as collaborators in their service experiences. Some studies have explored dimensions of co-creation behaviors. For instance, Campos et al. (2018) reviewed the literature defining co-creation and the dimensions of co-creation behaviors in tourism and hospitality contexts. Specifically, they summarized two dimensions of on-site co-creation experiences: tourists’ active participation and interactions. Active participation refers to tourists’ engagement in an experience based on their personal resources, capabilities, and strategies during physical and cognitive activities (Morgan et al., 2009; Prebensen and Foss, 2011). Interactions refer to relationships between tourists and people that manifest during an experience (Lugosi and Walls, 2013).

Aside from on-site co-creation behaviors, other scholars have identified several factors in the co-creation experience that can occur before and after travel. For example, Camilleri and Neuhofer, 2017 analyzed Airbnb reviews in Malta and uncovered six themes related to value co-creation: arriving and being welcomed, expressing positive/negative feelings, evaluating the accommodation and location, interacting with and receiving help from hosts, recommending the accommodation to others, and thanking one another.

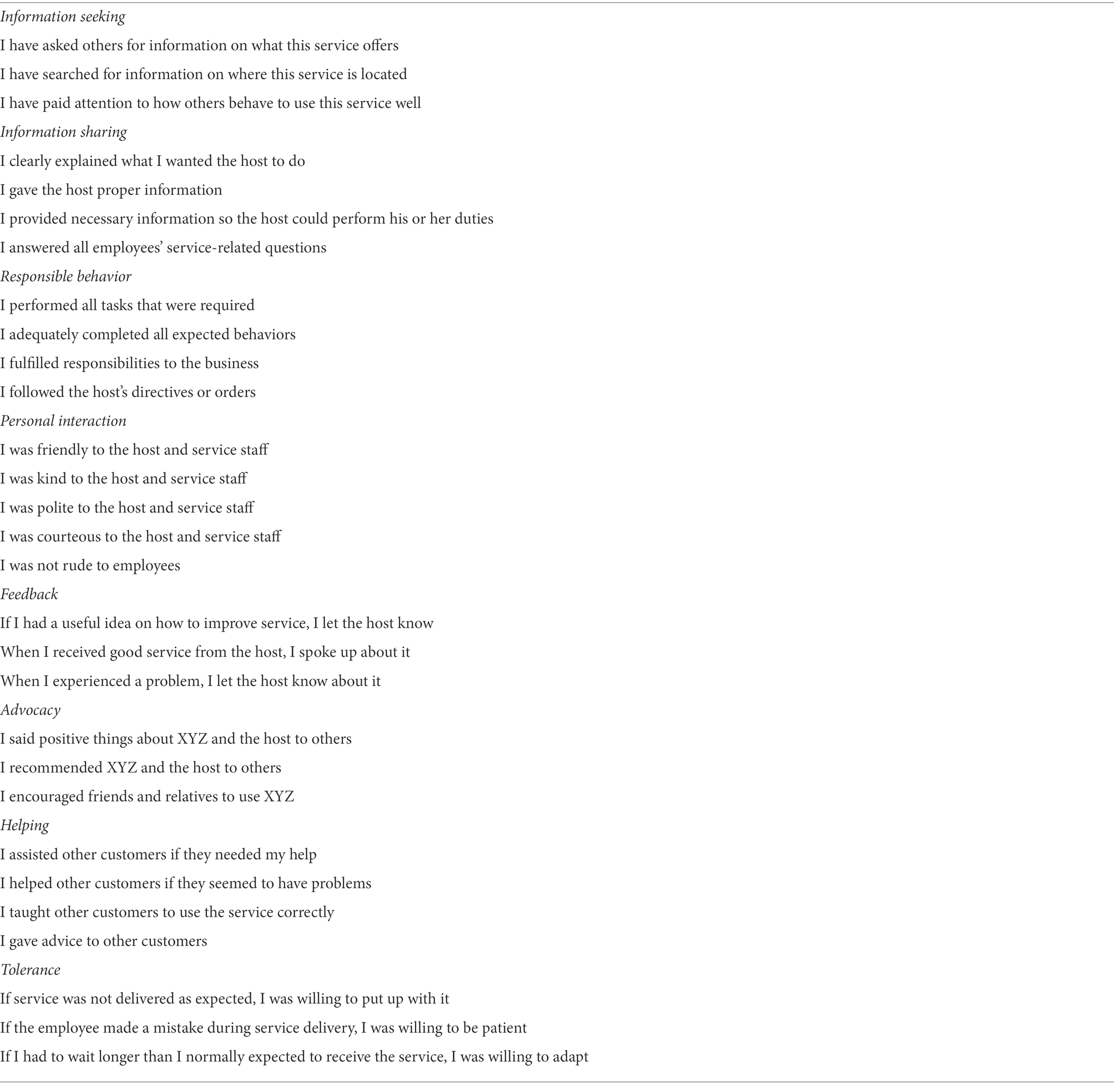

Based on early research, Yi and Gong (2013) outlined two types of customers’ value co-creation behavior, namely customer participation behavior and citizenship behavior. Customer participation behavior refers to (in-role) behavior necessary for successful value co-creation, and customer citizenship behavior is voluntary (extra-role) behavior that provides extraordinary value to the firm but is not necessarily required for value co-creation (Groth, 2005; Yi and Gong, 2013; Mitrega et al., 2022). This study also posits that customer participation behavior comprises four dimensions: information seeking, information sharing, responsible behavior, and personal interaction. In a similar vein, this study views customer citizenship behavior as consisting of feedback, advocacy, helping, and tolerance.

Researchers have largely examined the dimensions of customers’ value co-creation behavior from either a multidimensional perspective (e.g., Bettencourt, 1997; Bharwani and Jauhari, 2013; Bertella, 2014) or a uni-dimensional perspective using single-or multiple-item measures (e.g., Fang et al., 2008; Rihova et al., 2018). In an empirical study, Yi and Gong (2013) systematically explored the dimensionality of customers’ value co-creation behavior by developing a measurement scale. Their scale demonstrated internal consistency, construct validity, and nomological validity, indicating its suitability to measure value co-creation behavior in the service industry. We therefore assessed customers’ value co-creation behavior using this scale, although some measurement items were subject to revision in our study to reflect the hospitality literature and findings from in-depth interviews.

Customer loyalty

Customer loyalty can be defined as a customer’s likelihood of returning to a hotel (Bowen and Shoemaker, 2003). It costs less for firms to serve loyal customers because these consumers are more familiar with a given product and service and thus require less information; additionally, long-term customers tend to buy more, bring in new customers, and be less price-sensitive than newer consumers (Reichheld and Sasser, 1990). Yang and Peterson (2004) noted that loyal customers are more willing to share positive word-of-mouth and spend extra money on specific service operations. As such, it is important to understand the aspects of business performance that transform customers into repeat purchasers (Wilkins et al., 2009).

A large body of literature has considered customer loyalty. Most research maintains a general consensus that repeat purchase behavior, even if derived from customer satisfaction, does not necessarily reflect genuine loyalty (Wilkins et al., 2009). Customers make repeat purchases for various reasons, such as convenience and lack of choice. In addition, customer loyalty is especially difficult to achieve in tourism because novelty seeking has been identified as a primary motivation for travelers engaging in tourism activities (Sugathan and Ranjan, 2019).

The construct of customer loyalty has been considered from two perspectives. Some researchers have defined loyalty in behavioral terms based on the purchase volume for a particular brand (Tranberg and Hansen, 1986), whereas others have framed loyalty as attitudinal (Jacoby and Kyner, 1973). Baloglu (2002) examined attitudinal and behavioral dimensions of customer loyalty, noting that attitudinal loyalty consisted of trust, psychological or emotional attachment, and switching costs while behavioral loyalty involved cooperation (e.g., willingness to help a company and work with it to achieve mutual goals) and word-of-mouth recommendations (e.g., promotion, positive feedback, and referrals).

Conceptual framework and hypotheses development

Co-creation behavior has been found to exhibit significant and positive associations with customers’ perceived value and behavioral intentions in service settings (e.g., Shaw et al., 2011; Wang and Wan, 2012; Alqayed et al., 2022). Additionally, the influences of specific dimensions of value co-creation behavior on customers’ experiences, satisfaction, and loyalty have been widely examined. First, customer participation has been found to exert positive effects on customers’ perceptions of their overall experiences. For example, active participation is positively associated with service quality and memorable experiences (Cermak et al., 1994; Mathis et al., 2016; Campos et al., 2018). Cermak et al. (1994) empirically proved that participation is strongly tied to repurchase and referrals in some service settings. Chen et al. (2015) identified three components of customer participation in hospitality settings, indicating that these three components significantly influenced customer loyalty. Wang and Wan (2012) conducted an empirical study and pointed out that customers’ interactions with employees, products, and other customers positively affected experiential value and brand loyalty.

Second, according to Yi and Gong (2013), customer citizenship behavior includes four aspects: feedback, advocacy, helping, and tolerance. Customers who are engaged in citizenship behavior are believed to be active in providing feedback to service providers and recommending services to their friends and relatives. These consumers also tend to be willing to interact with and help other customers and are patient when adapting to different situations. Customers’ feedback to service providers regarding the physical environment and services, along with their tolerance and patience when encountering service failure, contributes to services that better suit patrons and elicit higher experiential satisfaction. Through advocacy and helping behavior, customers share positive information and advice with other customers while enjoying relational experiences with service providers and other consumers.

Based on prior literature, customers’ participation behavior and citizenship behavior should exert positive effects on the customer experience and loyalty. Hence, Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b) and 2(a) and 2(b) are proposed: Hypothesis 1: Customers’ value co-creation behavior [(a) participation behavior, (b) citizenship behavior] positively influences customer loyalty. Hypothesis 2: Customers’ value co-creation behavior [(a) participation behavior, (b) citizenship behavior] positively influences the customer experience.

Many studies have supported positive and significant relationships among the customer experience and its dimensions relative to customer satisfaction and loyalty (e.g., Zins, 2002; Han and Ryu, 2009; Wilkins et al., 2009; Wu and Liang, 2009). For example, Zins (2002) conducted an empirical study involving face-to-face interviews with leisure travelers and examined the relationships among customers’ consumption emotions, service experience evaluations, and satisfaction. Findings revealed that service experience evaluations positively influenced customer satisfaction.

Ample studies have also focused on partial dimensions of experience and its effects on customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. Han and Ryu (2009) examined relationships among three components of the physical environment (décor and artifacts, spatial layout, and ambient conditions), price perceptions, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. They found that these three physical environmental factors strongly influenced customers’ price perceptions and thus enhanced customer satisfaction and directly/indirectly influenced customer loyalty. Wu and Liang (2009) argued that the interactive relationship between customers and service employees is important in consumer evaluations. Furthermore, service employees’ behavior was identified as a key determinant of perceived service quality and consumer satisfaction. We therefore assume that the dimensions of the customer experience should collectively and individually influence consumers’ extent of satisfaction and loyalty. Studies have shown that in the hospitality industry, the relationship of “customers’ value co-creation behavior → customer experience → customer loyalty” is presumably positively related, leading to the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 3: Customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations positively influence customer loyalty. Hypothesis 4: Customers’ experiences mediate the relationship between customers’ value co-creation behavior [(a) participation behavior, (b) citizenship behavior] and customer loyalty.

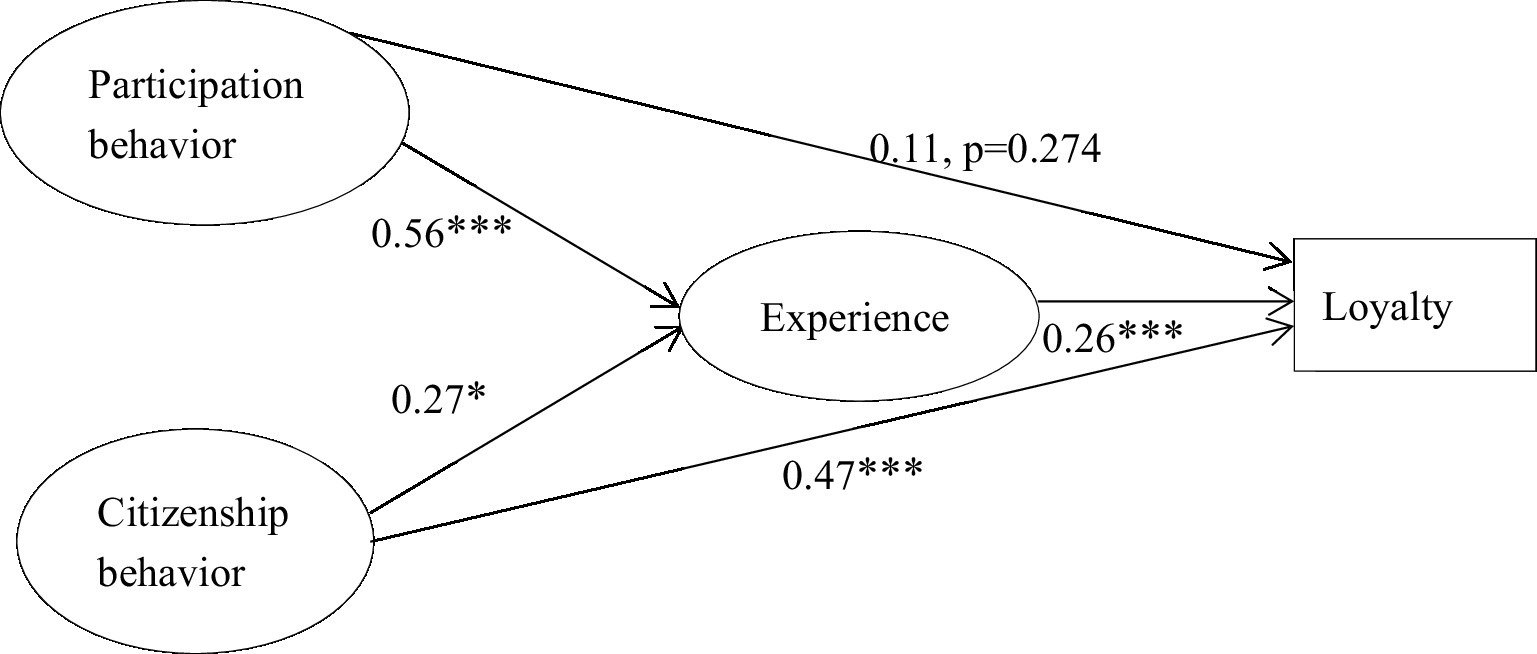

Based on the dimensions of the P2P accommodation experience drawn from the literature, and customers’ perceptions obtained from interviews, a measurement scale pertaining to customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations was developed following Churchill Jr (1979) scale development approach. Apart from examining the dimensionality of the customer experience, we tested interrelationships among the three focal constructs. We adopted valid and reliable measurement scales to assess customer co-creation behavior and loyalty. Figure 1 depicts relevant interrelationships drawn from the literature. Causality among constructs is indicated by arrows, which also show the direction of influence. The model begins with customers’ value co-creation behavior, evaluated using Yi and Gong (2013) measurement scale. The customer experience is predicted by the clues (i.e., major dimensions) of experience specified earlier. Customers’ value co-creation behavior influences the customer experience and resultant customer loyalty. As a consequent construct, customer loyalty is influenced by all other constructs. We developed this model primarily based on theory (i.e., the model components were derived from prior research and were chosen to address our study objectives).

Methodology

Research setting and data collection

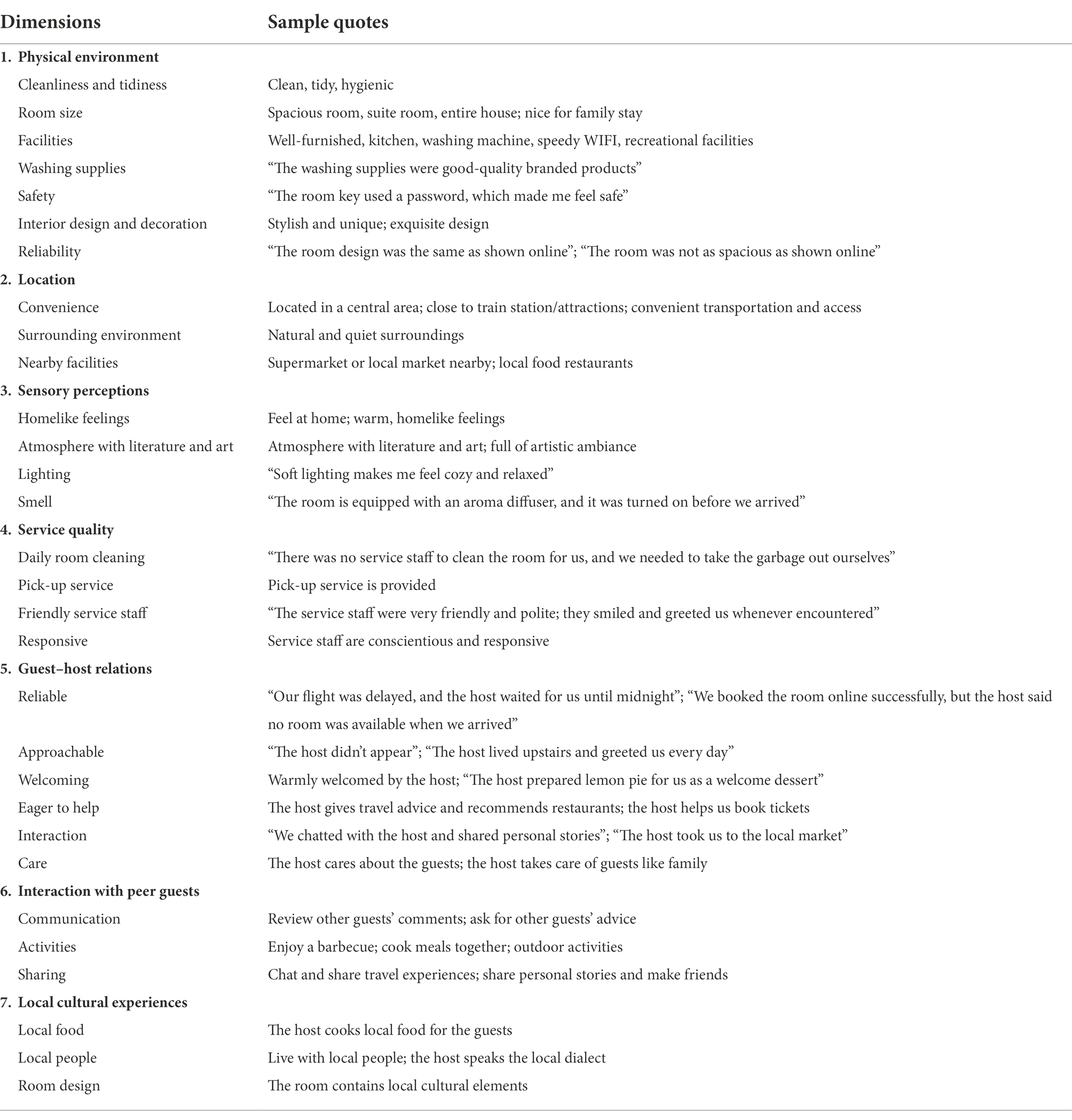

We adopted a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods in this study. Data were collected through three research steps: in-depth interviews, a pilot study, and the main survey. Initially, 34 in-depth interviews were conducted using convenience sampling from March to May 2020; interviews were intended to elicit dimensions and aspects of customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations. A semi-structured interview format was used to explore attributes that can contribute to positive/negative experiences with P2P accommodations. All attributes derived from interviews were integrated with factors summarized from the literature, which served as the foundation for questionnaire development. All interviewees and survey respondents met two criteria: (1) Chinese adult travelers residing in China who (2) had used P2P accommodations within the past 6 months at the time this survey was conducted. The interview result is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Interview results of customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations–dimensions and items (N = 34).

A pilot study was performed next to collect quantitative data and purify the measures. Three hundred questionnaires were distributed to respondents based on convenience sampling, and 254 valid questionnaires were returned. Measurement items corresponding to constructs in the questionnaire were purified based on the results of the pilot study. The main survey was conducted during June and July 2020. Given our large sampling requirements, we collaborated with a reputable survey company1 to distribute the revised questionnaires to 800 P2P users. We adopted a quota sampling method to obtain a representative sample; respondents residing in first-tier cities in China (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen) were selected as the target population. Ultimately, 519 complete questionnaires were returned.

Construct measures

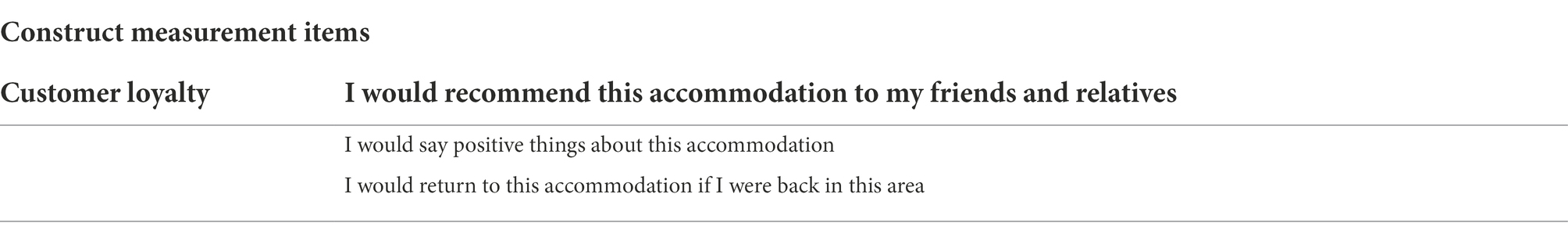

Measurement items related to the customer experience were derived from our interviews and previous studies. The initial measure for this construct included 37 items covering seven dimensions: physical environment, location, sensorial perceptions, service quality, guest–host relations, interaction with peer guests, and local cultural experiences. In addition to exploring the dimensions of customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations, in-depth interviews investigated dimensions of customers’ value co-creation behavior before, while, and after staying in P2P accommodations. Interviews helped verify Yi and Gong (2013) proposed dimensions and measurement items related to such behavior. Measurement items for customers’ value co-creation behavior are presented in Appendix I. Items for the customer loyalty construct were adapted from scales in relevant literature (see Appendix II).

Data analysis

Scale development related to customers’ experiences with P2P accommodations was conducted in line with Churchill Jr (1979) recommendations. First, text data gathered from interviews were analyzed using grounded theory as suggested by Strauss and Corbin (1997). Open coding and axial coding were then performed to identify underlying uniformities in the original category set and to formulate a smaller set of higher-level concepts. Items extracted from interviews were added to the item pool derived from the literature. Member checking and a panel review were conducted to enhance validity. Second, based on data from our pilot study, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to explore the dimensionality of each construct under investigation. The measurement items were further revised according to the EFA running result to suit the study context. Third, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was executed using IBM SPSS AMOS 21 software with data collected from the main survey. We performed CFA to confirm the factors extracted from EFA using data from the pilot study and to verify latent constructs based on the observed variables (Byrne, 2010). The structural parameters in the empirical model were ultimately tested via structural equation modeling (SEM).

Results

Demographic profile

Main survey respondents’ demographic profiles were fairly diverse in terms of gender, age, marital status, occupation, education, and annual income. In terms of gender, 48% of respondents were men and 52% were women. Most were millennials: 73% were between 23 and 37 years old. Slightly more than half (57%) were single. Respondents’ occupations were well balanced, with every occupation option appearing in our sample. The respondents were mostly well educated: 82.6% had received more than a high school diploma. Respondents’ annual income generally fell between 30,000 and 120,000 RMB.

Regarding travel-and accommodation-related information, most respondents reported traveling for tourism purposes, either individually or with friends. Only 12.3% stated having traveled for business purposes. Most respondents (62%) had stayed at an Airbnb property for only one or two nights; 81.7% stayed at an Airbnb property costing less than 500 RMB per night.

Measurement models

After purification through EFA, 5 dimensions were identified as comprising 30 measurement items related to the customer experience: Tangible and sensorial experience (Tang), Host (Host), Cultural experience (Cult), Interactions with peer guests (Inte), and Location (Loca). Our measurement model was tested using first-order CFA, and the results reflected a good model fit (χ2/df = 1623.96/395 = 4.111 < 5; TLI = 0.891; IFI = 0.902; CFI = 0.901; RMSEA = 0.078 < 0.08).

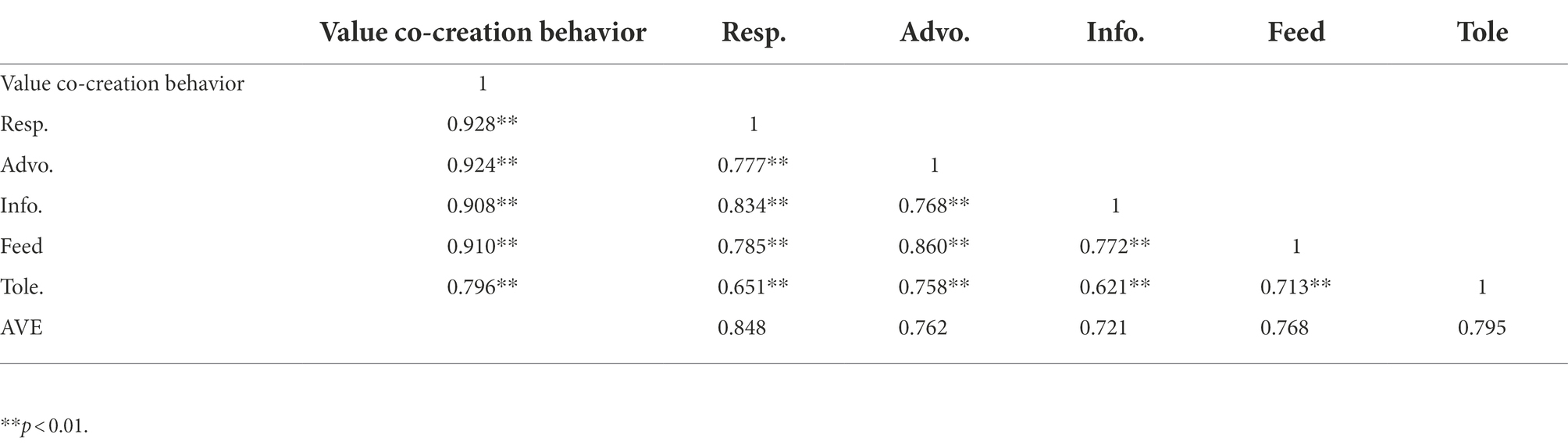

EFA results revealed two dimensions of value co-creation behavior, which consisted of five sub-dimensions: Responsible behavior (Resp), Information sharing (Info), Advocacy (Advo), Feedback (Feed), and Tolerance (Tole). CFA results reflected a good fit between the five-factor model and our data (χ2/df = 1158.38/289 = 4.008 < 5; TLI = 0.920; IFI = 0.929; CFI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.076 < 0.08).

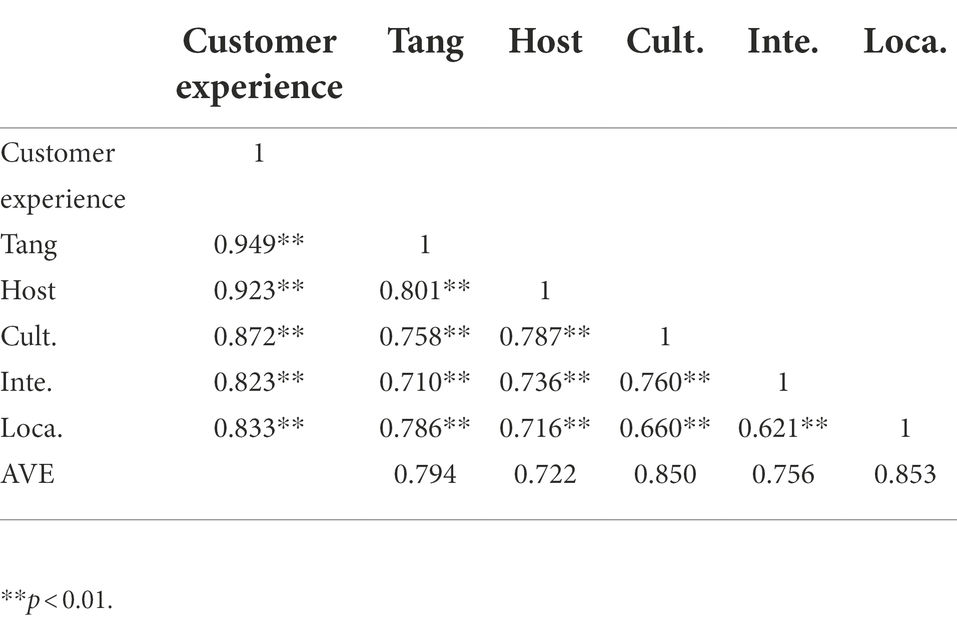

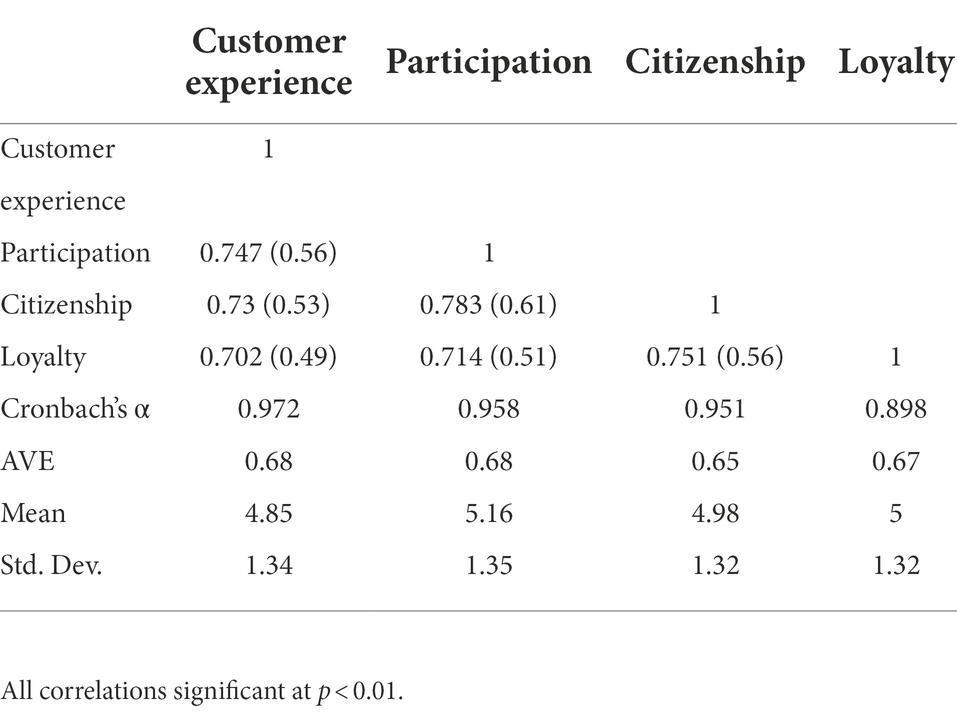

The reliability and validity of the measurement scales for customer experience and value co-creation behavior were examined next. The composite reliability of our multi-item scales was measured using Cronbach’s alpha. In this study, alpha coefficients ranged from 0.792 to 0.972 (customer experience) and from 0.861 to 0.973 (value co-creation behavior), well above the cut-off of 0.7 to suggest scale reliability (Hair et al., 2010). Validity is used to measure the adequacy of a measurement scale in measuring a specific variable (DeVellis, 2003); convergent validity and discriminant validity are most common. The correlation coefficient and average variance extracted (AVE) value for each dimension of customer experience and value co-creation behavior appear in Tables 2, 3, respectively. All dimensions were significantly related, with the correlation coefficient ranging from 0.621 to 0.801 (for customer experience) and from 0.651 to 0.860 (for value co-creation behavior). Therefore, customer experience and value co-creation behavior each demonstrated good convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). The AVE value of each dimension exceeded 0.7, indicating good convergent validity (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). In addition, the AVE value of each construct was greater than the squared correlation coefficient between corresponding constructs, confirming discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

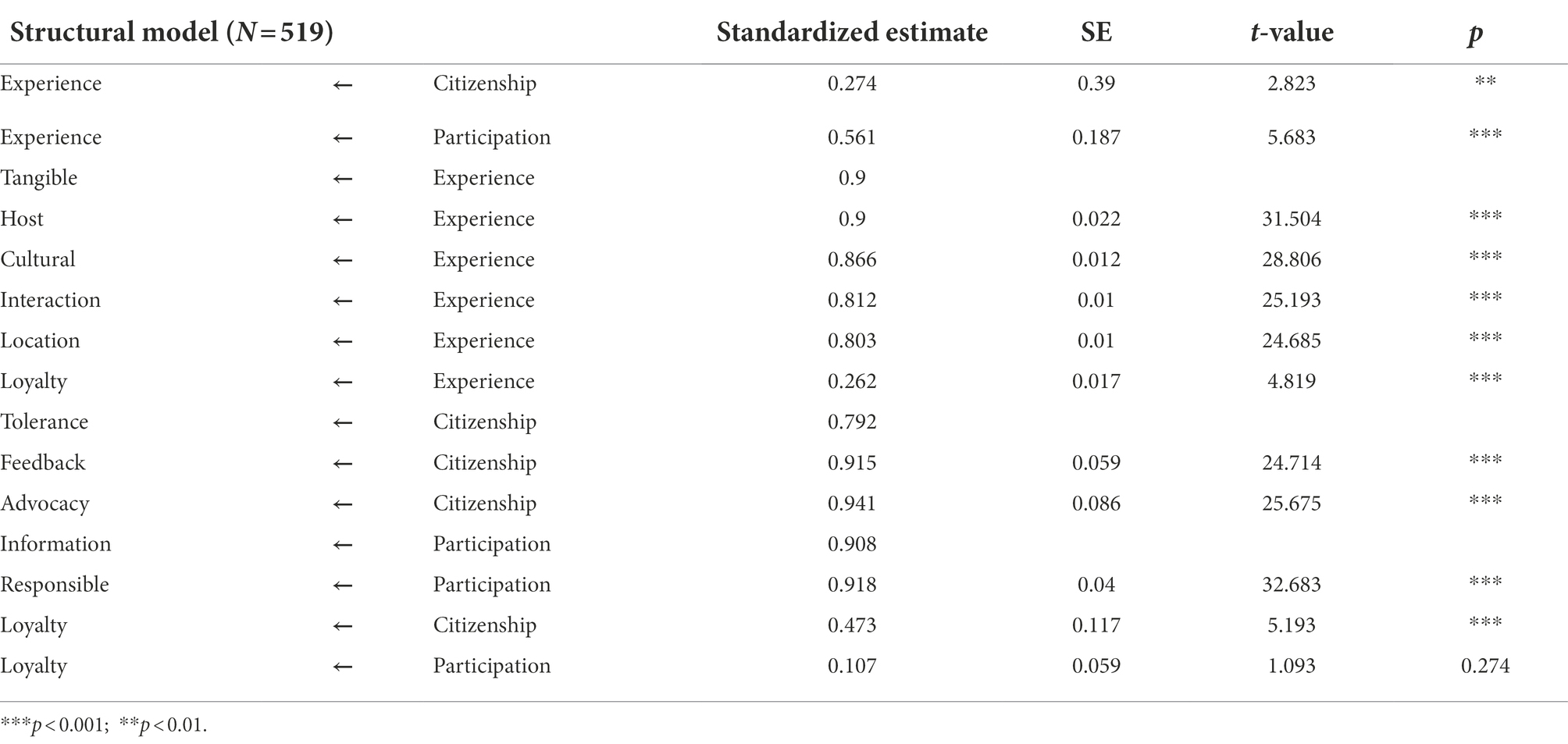

Testing for reliability, validity, and structural model

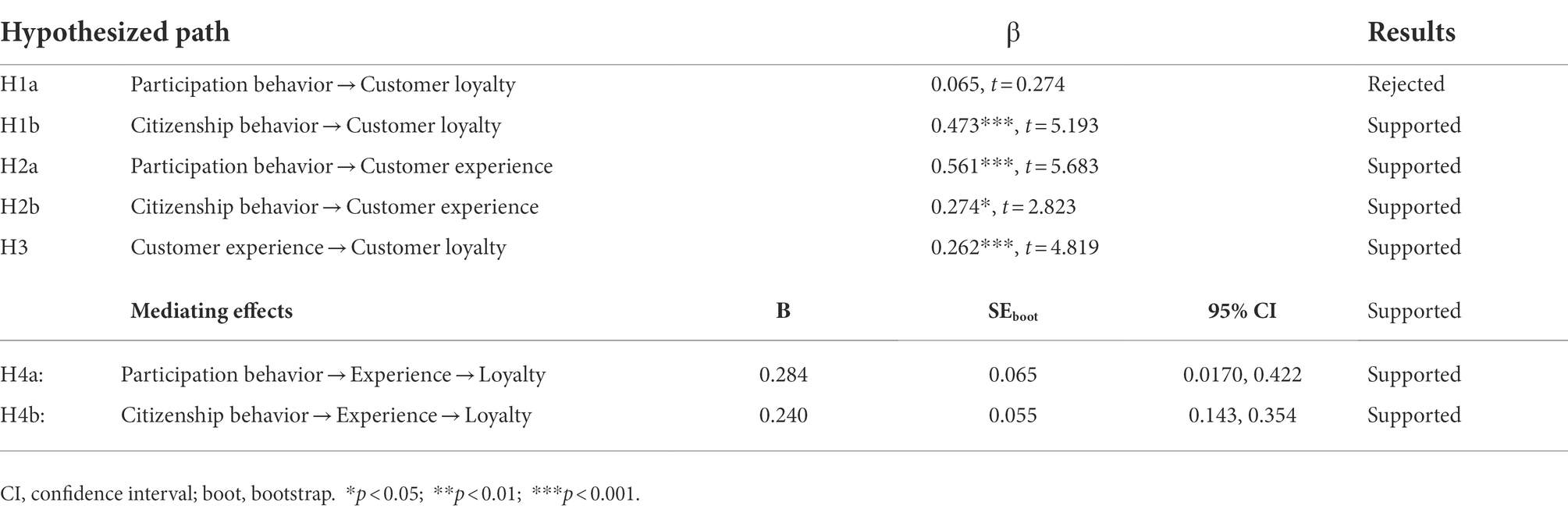

We employed SEM to examine whether our five hypotheses were empirically supported. The structural model was constructed to determine the respective impacts of two dimensions of value co-creation behavior. In this model, customers’ participation behavior and citizenship behavior were taken as independent variables. Customer experience was considered a mediating variable between value co-creation behavior and customer loyalty. Table 4 lists path coefficients in the structural model. Our results reflected a good model fit (χ2/df = 4.193 < 5; TLI = 0.968; GFI = 0.946; CFI = 0.978; RMSEA = 0.079 < 0.08).

Composite reliability of the multi-item scales was measured using Cronbach’s alpha; the alpha value for each construct appears in Table 5. All alpha coefficients were above the threshold of 0.7, indicating acceptable reliability. Convergent validity was substantiated by all AVE values exceeding 0.5 (see Table 4). Additionally, the AVE for each construct was greater than the squared correlation coefficients between corresponding constructs, verifying discriminant validity.

Hypothesis testing

SEM results for this model are shown in Figure 2. Customer participation behavior was found to exert a significant positive influence on the customer experience (β = 0.56, p < 0.001). Customer participation behavior had a positive but non-significant influence on customer loyalty (β = 0.11, p = 0.274). Customer citizenship behavior had a significant positive influence on the customer experience (β = 0.27, p < 0.05) and customer loyalty (β = 0.47, p < 0.001). The customer experience had a positive and significant influence on customer loyalty (β = 0.26, p < 0.001).

In examining the indirect effects of value co-creation behavior (Hypothesis 4) (i.e., customers’ participation behavior and citizenship behavior) on loyalty via customer experience, we used the bootstrapping method with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and 10,000 resamples (Shrout and Bolger, 2002). In this case, indirect effects are significant when the 95% CI does not include zero. This bootstrapping method is considered superior to the Sobel test given its robustness in testing mediation effects (Montoya and Hayes, 2017). To assess indirect effects via bootstrapping, we interpreted the PROCESS macro (Model 4) (Hayes, 2013) for each model. The direct effect of participation behavior on loyalty was not significant, whereas the direct effect of citizenship behavior on loyalty was significant. Having established direct effects [Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b)], indirect effects were then verified; see results in Table 6 The indirect effects of participation behavior on loyalty [β = 0.284, SEboot = 0.065, 95% CI: (0.170, 0.422)], and citizenship behavior on loyalty [β = 0.240, SEboot = 0.055, 95% CI: (0.143, 0.354)] via customer experience were all significant, providing support for Hypotheses 4(a) and 4(b), respectively. These findings indicate that the customer experience has a direct positive effect on loyalty and mediates the relationship between value co-creation behavior and loyalty.

Conclusion

Theoretical implications

This study makes several contributions to the tourism and hospitality management literature. First, our work extends the research stream on customers’ experiences in a P2P accommodation context by exploring the experiential dimensions of customers’ perceptions of P2P accommodations. As noted in previous research, the tangible and sensorial experiences, host, and location of P2P accommodations have been widely considered the most motivating attributes for visits. Our study also revealed two additional experiential dimensions, namely cultural experience and interaction with peer guests, which echo several other studies (e.g., Tussyadiah and Pesonen, 2016; Lutz and Newlands, 2018; Lin et al., 2019). Furthermore, apart from simply proposing experiential dimensions of P2P accommodations, our study takes a further step by developing a measurement scale of the customer experience and proposing the weight of each dimension in determining customers’ experiential evaluations.

Second, this study extends the body of knowledge around customer behavior in a P2P accommodation context by focusing on consumers’ value co-creation behavior and its impact on their experiential evaluations and behavioral intentions. Previous research tended to focus on identifying the factors that drove tourists to use P2P accommodations. As a response to Busser and Shulga’s (2018) call for research, we sought to better understand how value is created and what roles customers play in the value creation process. Our findings offer empirical evidence for the propositions that customers’ participation behavior and citizenship behavior have positive effects on producing memorable experiences. These aspects of consumers’ roles have thus been highlighted as antecedent variables of the customer experience.

Third, our study applied the SDL paradigm and incorporated the concept of value co-creation into P2P accommodation studies. The main contribution of our work lies in modeling the components and dynamics of value co-creation behavior and the customer experience in the context of sharing accommodations and exploring how these two constructs contribute to the ultimate marketing goal of customer loyalty. Our study is the first to consider the full dynamics of value co-creation behavior within a single model. As the P2P accommodation industry is still in its infancy, our findings are significant in opening avenues for future research by proposing a new pathway from value co-creation behavior to customer loyalty.

Practical implications

Our findings offer practical implications for P2P accommodation stakeholders and their competitors. By identifying the different influences of customers’ value co-creation behaviors (customer citizenship behavior and participation behavior), this study could assist peer managers to comprehend the role of peers/guests as value co-creators, and the main source of benefit to P2P properties and platforms.

First, this research provides a roadmap for sharing accommodation operators to design and manage customers’ experiences. The important role of value co-creation has been highlighted in this study as essential in creating satisfying experiences and promoting consumer loyalty. As customers gain power and control, P2P accommodation platforms, and service providers should focus on building an experiential environment conducive to provider–customer dialogue in order to increase co-creation experiential value. Communication and interaction among guests, service providers, and local communities, whether occurring face-to-face or virtually, also play important roles in customers’ value co-creation behavior. On one hand, P2P accommodation platforms should apply new technologies such as augmented reality, interactive maps, and smart communications (Buonincontri et al., 2017) or establish reputable rewards for knowledge sharing (Chen et al., 2017) to facilitate direct interaction and information sharing among guests and hosts. On the other hand, to encourage customers’ active participation, hosts should consider designing and facilitating offline activities to offer guests immersive destination experiences and interactive opportunities, such as cooking courses or traditional craft workshops. Guests can exert indirect or direct impacts on the co-creation of other guests’ experiences (Tung et al., 2017; Assiouras et al., 2019).

Second, customers’ willingness to co-create varies by age, cultural background, and consumption behavior (Buonincontri et al., 2017). As Chathoth et al., 2013 discovered, some tourist groups may be unwilling to participate in co-creation activities because they do not recognize the value of active participation in experience creation. Similarly, in a study by Lyu et al. (2019), Airbnb guests older than age 40 were found to express less interest in socializing with other guests. Some customers may also be reluctant to co-create due to a lack of knowledge and self-efficacy.

Given these findings, service providers should segment their markets based on customers’ willingness and competence and then provide guests with different combinations of active participation, interaction, and sharing possibilities (Buonincontri et al., 2017; Im and Qu, 2017). Meanwhile, service providers should be reminded that the co-creation process must be managed appropriately to avoid “overburdening” customers (Stokburger-Sauer et al., 2016, p.566) or contributing to “value co-destruction” (Plé and Cáceres, 2010, p.431); otherwise, co-creation activities may detract from customers’ overall experience. This pattern may explain the false direct correlation between participation behavior and loyalty identified in this study.

Third, tourist pursue pleasure as well as core meaning in travel, which includes escaping from daily life, personal development, and re-establishing interpersonal relationships (Pine and Gilmore, 1998). Social and cultural experiences are contingent on guests’ subjective purposes. Customers’ value co-creation behavior was found to positively influence the customer experience. To use P2P accommodations to the fullest, guests are encouraged to seek related information online and to communicate with hosts before making reservations. Active participation in an experience and interaction with others contribute significantly to enhanced attention and memorability of a tourist experience (Campos et al., 2018). Guests can actively participate in value co-creation activities through various means, such as by searching for information about a service, sharing feedback with service providers, assisting other customers if they need help, and so on. P2P accommodation platforms and hosts should develop a friendly environment (online and offline) to facilitate guests’ engagement in creating an experience and associated value.

Limitations and directions for further research

Similar to other studies, this research is not free of limitations. Our results should be interpreted cautiously for several reasons. This study is the first to apply customers’ value co-creation behavior as an antecedent of experience and loyalty in the P2P accommodation industry. Because the customer experience is highly subjective and may differ across cultures, the findings from our model may not be generalizable to other settings. Future research should replicate this model in other contexts to cross-validate our results. Data for the proposed model were also cross-sectional and correlational; all predictor and outcome variables were obtained from the same population, and our interpretations are therefore tentative. Future research could address these limitations by using longitudinal analysis to capture and control disparities and causal directions among variables. In addition, measurement items for the construct of value co-creation behavior were derived from prior hospitality and marketing studies; other potential items may be discovered when adopting other methods, such as qualitative research or big data analysis. To expand upon the model proposed in this study, subsequent research should include other variables such as the perceived value of experience (Knutson et al., 2010; Wu, 2013), motivational factors behind staying in P2P accommodations (Guttentag et al., 2018), and customer satisfaction (Huang and Hsu, 2010) to explore the relationship of value co-creation behavior and loyalty. As disclosed in a recent market research report from China Tourism Academy (2017), when selecting Airbnb properties, female tourists emphasize their cultural and emotional experiences while male tourists focus more on practical aspects (e.g., the safety and convenience of the property). As such, future research could deepen our proposed model by incorporating certain sociodemographic variables (e.g., gender) as moderators and testing whether they moderate the relationship between value co-creation behavior and loyalty.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JL was in charge of conceptualization, writing-original draft, and funding acquisition. KC was in charge of investigation. SY was in charge of formal analysis, writing-review and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by Research Startup Foundation for Advanced Talents provided by Shenzhen Polytechnic (Project No. 6021310017S) and the Innovation Team Project of Universities in Guangdong Province, China (grant no. 2021WCXTD026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abbott, L. (1955). Quality and competition: An essay in economic theory. New York: Columbia University Press, doi: 10.7312/abbo92492.

Alqayed, Y., Foroudi, P., Kooli, K., Foroudi, M. M., and Dennis, C. (2022). Enhancing value co-creation behaviour in digital peer-to-peer platforms: an integrated approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 102:103140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103140

Assiouras, I., Skourtis, G., Giannopoulos, A., Buhalis, D., and Koniordos, M. (2019). Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 78:102742. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102742

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

Baloglu, S. (2002). Dimensions of customer loyalty: separating friends from well-wishers. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Admin. Q. 43, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8804(02)80008-8

Bertella, G. (2014). The co-creation of animal-based tourism experience. Tour. Recreat. Res. 39, 115–125. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2014.11081330

Bettencourt, L. A. (1997). Customer voluntary performance: customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retail. 73, 383–406. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90024-5

Bharwani, S., and Jauhari, V. (2013). An exploratory study of competencies required to co-create memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 25, 823–843. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-05-2012-0065

Bowen, J. T., and Shoemaker, S. (2003). Loyalty: a strategic commitment. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 44, 31–46. doi: 10.1177/001088040304400505

Brodie, R. J., Löbler, H., and Fehrer, J. A. (2019). Evolution of service-dominant logic: towards a paradigm and meta-theory of the market and value co-creation? Ind. Mark. Manag. 79, 3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.03.003

Bu, Y., Parkinson, J., and Thaichon, P. (2022). Influencer marketing: homophily, customer value co-creation behaviour and purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 66:102904. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102904

Buonincontri, P., Morvillo, A., Okumus, F., and van Niekerk, M. (2017). Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: empirical findings from Naples. Tour. Manag. 62, 264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.014

Busser, J. A., and Shulga, L. V. (2018). Co-created value: multidimensional scale and nomological network. Tour. Manag. 65, 69–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.014

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming, (2th Edn). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Camilleri, J., and Neuhofer, B. (2017). Value co-creation and co-destruction in the Airbnb sharing economy. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 29, 2322–2340. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2016-0492

Campos, A. C., Mendes, J., Valle, P. O. D., and Scott, N. (2018). Co-creation of tourist experiences: a literature review. Curr. Issue Tour. 21, 369–400. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1081158

Cermak, D. S., File, K. M., and Prince, R. A. (1994). Customer participation in service specification and delivery. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 10, 90–97. doi: 10.19030/jabr.v10i2.5942

Chathoth, P., Altinay, L., Harrington, R. J., Okumus, F., and Chan, E. S. (2013). Co-production versus co-creation: a process based continuum in the hotel service context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 32, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.03.009

Chen, C., Du, R., Li, J., and Fan, W. (2017). The impacts of knowledge sharing-based value co-creation on user continuance in online communities. Inf. Dis. Deliv. 45, 227–239. doi: 10.1108/IDD-11-2016-0043

Chen, S. C., Raab, C., and Tanford, S. (2015). Antecedents of mandatory customer participation in service encounters: an empirical study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 46, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.01.012

Cheng, M. (2016). Sharing economy: a review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 57, 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.003

Chiadmi, N. E. R. (2014). The co-creation of tourism experience: Destination marketing organization and tourist perspective. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

China Tourism Academy (2017). Market trend report of Chinese sharing accommodation 2017-outbound tourism. Retrieved from http://www.ctaweb.org/html/2017-6/2017-6-8-9-44-31860.html

Churchill, G. A. Jr. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 16, 64–73. doi: 10.1177/002224377901600110

Cohen, B., and Munoz, P. (2016). Sharing cities and sustainable consumption and production: towards an integrated framework. J. Clean. Prod. 134, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.133

Cui, X., Xie, Q., Zhu, J., Shareef, M. A., Coraya, M. A. S., and Akram, M. S. (2022). Understanding the omnichannel customer journey: the effect of online and offline channel interactivity on consumer value co-creation behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 65:102869. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102869

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). “Scale development-theory and applications,” in Applied social research methods series, Vol. 26. 2nd Edn. (London: Sage Publications).

Eraqi, M. I. (2010). Co-creation and the new marketing mix as an innovative approach for enhancing tourism industry competitiveness in Egypt. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 8, 76–91. doi: 10.1504/IJSOM.2011.037441

Fang, E., Palmatier, R. W., and Steenkamp, J. B. E. (2008). Effect of service transition strategies on firm value. J. Mark. 72, 1–14. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.72.5.001

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Gilmore, J. H., and Pine, B. J. (2002). Customer experience places: the new offering frontier. Strateg. Leadersh. 30, 4–11. doi: 10.1108/10878570210435306

Groth, M. (2005). Customers as good soldiers: examining citizenship behavior in internet service deliveries. J. Manag. 31, 7–27. doi: 10.1177/0149206304271375

Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issue Tour. 18, 1192–1217. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

Guttentag, D., Smith, S., Potwarka, L., and Havitz, M. (2018). Why tourists choose Airbnb: a motivation-based segmentation study. J. Travel Res. 57, 342–359. doi: 10.1177/0047287517696980

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis, 7th Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International.

Han, H., and Ryu, K. (2009). The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 33, 487–510. doi: 10.1177/1096348009344212

Hauser, J. R., and Urban, G. L. (1979). Assessment of attribute importance and consumer utility functions: Von Neumann-Morgenstern theory applied to consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 5, 251–262. doi: 10.1086/208737

Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford.

Heo, Y. (2016). Sharing economy and prospects in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 58, 166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2016.02.002

Huang, J., and Hsu, C. H. (2010). The impact of customer-to-customer interaction on cruise experience and vacation satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 49, 79–92. doi: 10.1177/0047287509336466

Im, J., and Qu, H. (2017). Drivers and resources of customer co-creation: a scenario-based case in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 64, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.03.007

Jacoby, J., and Kyner, D. B. (1973). Brand loyalty vs. repeat purchasing behavior. J. Mark. Res. 10, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/002224377301000101

Knutson, B. J., Beck, J. A., Kim, S., and Cha, J. (2010). Service quality as a component of the hospitality experience: proposal of a conceptual model and framework for research. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 13, 15–23. doi: 10.1080/15378021003595889

Li, X., and Petrick, J. F. (2008). Tourism marketing in an era of paradigm shift. J. Travel Res. 46, 235–244. doi: 10.1177/0047287507303976

Lin, P. M. C., Peng, K-L., Ren, L., and Line, C-W. (2019). Hospitality co-creation with mobility-impaired people - sciencedirect. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 77, 492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.08.013

Lugosi, P., and Walls, A. R. (2013). Researching destination experiences: themes, perspectives and challenges. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.07.001

Lusch, R. F., Vargo, S. L., and O’brien, M. (2007). Competing through service: insights from service-dominant logic. J. Retail. 83, 5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2006.10.002

Lutz, C., and Newlands, G. (2018). Consumer segmentation within the sharing economy: the case of airbnb. J. Bus. Res. 88, 187–196.

Lyu, J., Li, M., and Law, R. (2019). Experiencing P2P accommodations: anecdotes from Chinese customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 77, 323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.07.012

Malshe, A., and Friend, S. B. (2018). Initiating value co-creation: dealing with non-receptive customers. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 46, 895–920. doi: 10.1007/s11747-018-0577-6

Mathis, E. F., Kim, H. L., Uysal, M., Sirgy, J. M., and Prebensen, N. K. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Ann. Tour. Res. 57, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.023

Mathisen, L. (2013). Staging natural environments: a performance perspective. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 9, 163–183. doi: 10.1108/S1745-3542(2013)0000009012

Mcintosh, A. J., and Siggs, A. (2005). An exploration of the experiential nature of boutique accommodation. J. Travel Res. 44, 74–81. doi: 10.1177/0047287505276593

Mitrega, M., Klezl, V., and Spacil, V. (2022). Systematic review on customer citizenship behavior: clarifying the domain and future research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 140, 25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.029

Montoya, A. K., and Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: a path-analytic framework. Psychol. Methods 22, 6–27. doi: 10.1037/met0000086

Morgan, M., Elbe, J., and de Esteban Curiel, J. (2009). Has the experience economy arrived? The views of destination managers in three visitor-dependent areas. Int. J. Tour. Res. 11, 201–216. doi: 10.1002/jtr.719

Nextunicorn (2019). Airbnb vs Tujia: who is winning the home sharing competition in China. Retrieved from http://nextunicorn.ventures/airbnb-vs-tujia-who-is-winning-the-home-sharing-competition-in-china/

Perkins, H. C., and Thorns, D. C. (2001). Gazing or performing? Reflections on Urry’s tourist gaze in the context of contemporary experience in the antipodes. Int. Sociol. 16, 185–204. doi: 10.1177/0268580901016002004

Pine, B. J., and Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 76, 97–105.

Plé, L., and Cáceres, R. C. (2010). Not always co-creation: introducing interactional co-destruction of value in service-dominant logic. J. Serv. Mark. 24, 430–437. doi: 10.1108/08876041011072546

Prahalad, C. K., and Ramaswamy, V. (2004a). Co-creation experiences: the next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 18, 5–14. doi: 10.1002/dir.20015

Prahalad, C. K., and Ramaswamy, V. (2004b). Co-creating unique value with customers. Strateg. Leadersh. 32, 4–9. doi: 10.1108/10878570410699249

Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., and Uysal, M. (Ed.) (2014). “Co-creation of tourist experience: scope, definition and structure,” in Creating Experience Value in Tourism.

Prebensen, N. K., and Foss, L. (2011). Coping and co-creating in tourist experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 13, 54–67. doi: 10.1002/jtr.799

Reichheld, F. P., and Sasser, W. E. (1990). Zero defections: quality comes to services. Harv. Bus. Rev. 68, 105–111.

Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Gouthro, M. B., and Moital, M. (2018). Customer-to-customer co-creation practices in tourism: lessons from customer-dominant logic. Tour. Manag. 67, 362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.010

Shaw, G., Bailey, A., and Williams, A. (2011). Aspects of service-dominant logic and its implications for tourism management: examples from the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 32, 207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2010.05.020

Shrout, P. E., and Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., Scholl-Grissemann, U., Teichmann, K., and Wetzels, M. (2016). Value cocreation at its peak: the asymmetric relationship between coproduction and loyalty. J. Serv. Manag. 27, 563–590. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-10-2015-0305

Sugathan, P., and Ranjan, K. R. (2019). Co-creating the tourism experience. J. Bus. Res. 100, 207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.032

Tranberg, H., and Hansen, F. (1986). Patterns of brand loyalty: their determinants and their role for leading brands. Eur. J. Mark. 20, 81–109. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000004642

Tuan, L. T., Rajendran, D., Rowley, C., and Khai, D. C. (2019). Customer value co-creation in the business-to-business tourism context: the roles of corporate social responsibility and customer empowering behaviors. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 39, 137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.04.002

Tung, V. W. S., Chen, P. J., and Schuckert, M. (2017). Managing customer citizenship behaviour: the moderating roles of employee responsiveness and organizational reassurance. Tour. Manag. 59, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.07.010

Tussyadiah, I. P., and Pesonen, J. (2016). Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. J. Travel Res. 55, 1022–1040. doi: 10.1177/0047287515608505

Tussyadiah, I. P., and Pesonen, J. (2018). Drivers and barriers of peer-to-peer accommodation stay–an exploratory study with American and Finnish travellers. Curr. Issue Tour. 21, 703–720. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1141180

Tussyadiah, I. P., and Zach, F. (2017). Identifying salient attributes of peer-to-peer accommodation experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 34, 636–652. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1209153

Vargo, S. L., and Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 68, 1–17. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., and Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 85, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2008.11.001

Wang, X. X., and Wan, W. H. (2012). Study on the mechanisms of value co-creation and its impact on brand loyalty [消费领域共创价值的机理及对品牌忠诚的作用研究]. J. Manag. Sci. 25, 52–65.

Warnaby, G., and Medway, D. (2015). “Rethinking the place product from the perspective of the service-dominant logic of marketing,” in Rethinking Place Branding. eds. M. Kavaratzis, G. Warnaby, and G. Ashworth (Springer, Cham), 33–50.

Wilkins, H., Merrilees, B., and Herington, C. (2009). The determinants of loyalty in hotels. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 19, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/19368620903327626

Wu, C. H. J., and Liang, R. D. (2009). Effect of experiential value on customer satisfaction with service encounters in luxury-hotel restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 28, 586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.03.008

Wu, H. C. (2013). An empirical study of the effects of service quality, perceived value, corporate image, and customer satisfaction on behavioral intentions in the Taiwan quick service restaurant industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 14, 364–390. doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2013.802581

Yang, Z., and Peterson, R. T. (2004). Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: the role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 21, 799–822. doi: 10.1002/mar.20030

Yi, Y., and Gong, T. (2013). Customer value co-creation behavior: scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 66, 1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.026

Zhu, Y., Cheng, M., Wang, J., Ma, L., and Jiang, R. (2019). The construction of home feeling by airbnb guests in the sharing economy: a semantics perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 75, 308–321. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.013

Zins, A. H. (2002). Consumption emotions, experience quality and satisfaction: a structural analysis for complainers versus non-complainers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 12, 3–18. doi: 10.1300/J073v12n02_02

Appendix

APPENDIX I Measurement items of customers’ value co-creation behavior used in the survey.

APPENDIX II Measurement items of customer loyalty used in the survey.

Keywords: P2P accommodations, customer experience, value co-creation, participation behavior, citizenship behavior

Citation: Lyu J, Cao K and Yang S (2022) The impact of value co-creation behavior on customers’ experiences with and loyalty to P2P accommodations. Front. Psychol. 13:988318. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.988318

Edited by:

Wen-Qi Ruan, Huaqiao University, ChinaReviewed by:

Andrei Bonamigo, Fluminense Federal University, BrazilRuzzakiah Jenal, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Lyu, Cao and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shan Yang, MTE2OTgzMDE4QHFxLmNvbQ==

Jing Lyu1

Jing Lyu1 Shan Yang

Shan Yang