- 1School of Health Policy and Management, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- 2School of Nursing, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- 3Institute of Healthy Jiangsu Development, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

Objective: Our study aims to test whether anxiety mediated the association between perceived stress and life satisfaction and whether the mediating effect was moderated by resilience among elderly migrants in China.

Methods: We used self-reported data collected from 654 elderly migrants in Nanjing. Regression analyses using bootstrapping methods were conducted to explore the mediating and moderating effects.

Results: The results showed that anxiety mediated the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction (indirect effect = –0.040, CI [–0.066, –0.017]). Moreover, moderated mediated analysis indicated that resilience moderated the path between anxiety and life satisfaction (moderating effect = 0.034, 95% CI [0.021, 0.048]). In particular, anxiety had a negative impact on life satisfaction only for Chinese elderly migrants with lower resilience.

Conclusion: Our study suggests that perceived stress could reduce life satisfaction among elderly migrants as their anxiety levels increase. Fortunately, elderly migrants’ resilience could undermine this negative effect.

Introduction

The 7th National Census Bulletin issued by the National Bureau of Statistics shows that China’s floating population has reached 376 million in 2021, and predicts that the number of elderly migrants will continue to grow (Li and Dou, 2022). Facing the dual dilemma of aging and mobility, elderly migrants may have poor adaptability (Alizadeh-Khoei et al., 2011). Some studies indicated that immigrants had higher distress than the native population at the initial stage of their immigration process (Chen, 2011). After moving to new living environments, elderly migrants face a variety of problems due to the change in social networks (Dietzel-Papakyriakou and Olbermann, 1996), longstanding household registration (“hukou”) (Hou et al., 2021)policy restrictions, cultural differences, living styles, and language barriers. Due to these objective socio-economic disadvantages, migrant older adults are easy to feel a sense of relative deprivation (Xia and Ma, 2020). As a result, a series of mental health problems have emerged, such as increased perceived stress, and increased anxiety, ultimately leading to a decline in life satisfaction.

Life satisfaction is a component of subjective wellbeing (Diener, 1996) and is a cognitive judgment of an individual’s satisfaction with his or her entire life. It is one of the most important factors affecting the mental health of an individual and determining his/her adaptation to old age (Tambag, 2013). Improving the life satisfaction of migrant older adults contributes to their successful aging and improving quality of life. Previous studies have revealed that personal variables, such as perceived stress (Chen et al., 2017), anxiety (Brailovskaia et al., 2018), and resilience (Azpiazu Izaguirre et al., 2021), could strongly predict individuals’ life satisfaction, but there is no research to confirm their combined impact on life satisfaction. How to make the huge number of elderly migrants have a happy life in their old age is a major matter with long-term and far-reaching significance. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the influence of the psychological factors that regulate or intervene in the life satisfaction of migrant older adults. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between perceived stress, anxiety, and life satisfaction of elderly migrants, and to investigate the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction of elderly migrants, as well as the moderating role of resilience.

Perceived stress and life satisfaction

Perceived stress is a psychological reaction generated after an individual experiences stimuli in the environment and evaluates them cognitively (Cohen et al., 1983). When an individual encounters frustration and pressure, it does not necessarily directly affect the individual itself. Only the perceived press can produce a series of emotional and behavioral reactions. With irreversible changes in physiological functions, the elderly become more sensitive to their surroundings and have a stronger awareness of external pressure events. Even trivial things in life are prone to strong emotional and emotional responses. Chronic diseases, bereavement, and sleep disorders are common sources of stress. Compared with the general elderly, the elderly migrants are more likely to suffer from intergenerational conflict, economic source instability, loss of social circle, and other aspects of pressure. They often have difficulty responding effectively to negative events and are prone to perceive higher levels of external stress. The concept of perceived stress has been extensively researched since its inception (McHugh et al., 2020; Moseley et al., 2021). Nonetheless, there has been little focus on elderly migrants’ perceived stress.

Life satisfaction is a cognitive process in which individuals evaluate their state of pleasure in life by comparing their current circumstances to a range of personal ideal criteria (Lee et al., 2016). Life satisfaction is an essential metric for assessing the physical and mental health, as well as the wellbeing, of older adults (Van Damme-Ostapowicz et al., 2021), which is of great significance for promoting active aging (Gana et al., 2013). According to Selye’s stress theory, a high or prolonged stress level will consume an individual’s resources and psychological energy to cope with stress, and reduce life satisfaction (Randall and Bodenmann, 2009). Existing research revealed that perceived stress was a well-known cause of numerous emotional issues, including depression (Das et al., 2020), loneliness (Peavy et al., 2022), and anxiety (Yu and Liu, 2018). And perceived stress is a significant forecaster of low life satisfaction (Kim, 2019). Existing researches indicate that perceived stress has a significantly predictive impact on life satisfaction (Hamarat et al., 2001; Hwang and Hyeseong, 2020). The greater the perceived stress, the lower life satisfaction. Therefore, perceived stress may be one of the factors affecting life satisfaction among seniors. Thus, in this study, we focused on Chinese elderly migrants’ perceived stress and hypothesized that their perceived stress would be negatively correlated to their life satisfaction.

Anxiety, perceived stress, and life satisfaction

Anxiety in later life is a very common mental illness (Baxter et al., 2013; El-Gabalawy et al., 2013). As the number of seniors increases globally, anxiety will become a prevalent problem in later life (Balsamo et al., 2018). Some studies indicated anxiety disorders, depression, and stress prevail among the elderly (Babazadeh et al., 2016). Previous literature has shown a significant positive correlation between perceived stress and anxiety (Tan et al., 2021). Older adults with higher perceived stress have higher levels of anxiety (Shi et al., 2020). People are prone to anxiety symptoms such as agitation after experiencing a period of stressful states and without a reasonable release of stress. Moreover, anxiety is negatively correlated to life satisfaction (Yu et al., 2020; Mei et al., 2021; Hoseini-Esfidarjani et al., 2022). Anxiety, according to a previous study, is a possible cause that reduces the wellbeing in seniors (Brown Wilson et al., 2019). Long-term anxiety has a significant impact on the health of the seniors, causing not only a series of symptoms such as depression (Kandola and Stubbs, 2020), but also a series of physical conditions, such as decreased sleep function, hypertension, and cognitive decline (Andreescu and Lee, 2020), which can jeopardize physical and psychological health and reduce life satisfaction (Abreu et al., 2018; Weger and Sandi, 2018). Therefore, anxiety may operate as a mediator in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Migration is an extremely stressful phenomenon that produces significant levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Bhugra, 2004; Levecque et al., 2007; Familiar et al., 2011). Previous studies in China have identified a significant increase in the prevalence of anxiety and depression among elderly migrants, which has become an important issue affecting their quality of life (Yu and Liu, 2018; Li and Kong, 2022). Compared with the local elderly, elderly migrants face low levels of social interaction (Lin et al., 2020), and lack of contact with friends. They are separated from society (Kim et al., 2012), then lose their original social capital and face communication barriers (Liu et al., 2013). They lack channels for dealing with perceived stress, leading them to easily dwell on pessimistic ruminations and eventually develop mental disorders, such as depression (Kim et al., 2012) and loneliness (Tang et al., 2020). In addition, the elderly with rural household registration, chronic disease, no pension insurance or pension, and no company with spouse may experience stronger culture shock, poorer physical health, poorer economic status, lack of emotional support from spouse, and are more likely to fall into anxiety. When migrant older adults are in a state of chronic anxiety, they tend to be less interested in life, which ultimately leads to a decrease in life satisfaction. As a result, we further predicted anxiety as a mediator in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction among Chinese elderly migrants.

Resilience, anxiety, and life satisfaction

Not all anxious individuals report decreased life satisfaction. Some beneficial factors may have contributed to the prevention of anxiety turning into depressive symptoms. The American Psychological Association considers resilience as a person’s capacity to recover from stressful conditions and as a good adaptation to traumatic events (Montazeri, 2008). In accord with the resilience framework, resilience can act as a moderating buffer against the harmful effects of adversity as a dynamic process (Kumpfer, 2002). Moreover, resilience is being studied as a source of support for life satisfaction (Plexico et al., 2019). Many researches have found a link between resilience and life satisfaction (Azpiazu Izaguirre et al., 2021; Sørensen et al., 2021). Furthermore, a study discovered that nurses with high resilience were prone to experience decreased anxiety (Labrague and De Los Santos, 2020). However, insufficient resilience may contribute to negative mental health indicators (e.g., anxiety) (Hu et al., 2015; Wollny and Jacobs, 2021). It is difficult for elderly migrants who lack resilience to get back fast from stress, adjust successfully, keep excellent mental health, or diminish adversity and tackle problems, thus falling into the negative emotion of anxiety. Based on the above theoretical framework and findings, we hypothesized that resilience would moderate the association between anxiety and life satisfaction. Moreover, anxiety had a negative impact on life satisfaction only for Chinese elderly migrants with lower resilience.

Hypothetical research model

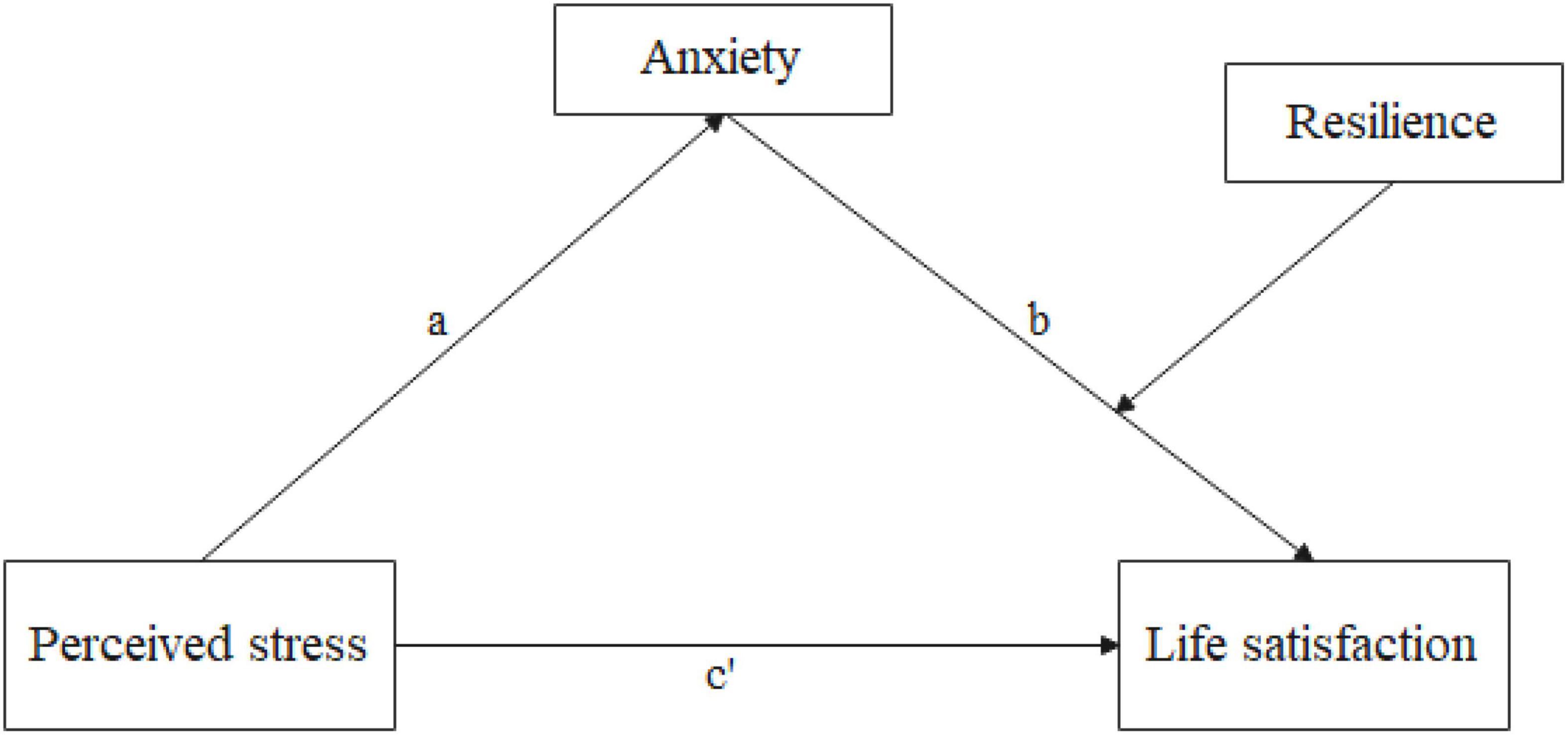

We concentrated on the impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction among Chinese elderly migrants in this study. Furthermore, we investigated the mechanism of this association using anxiety as a mediator and resilience as a moderator. We proposed the following hypotheses (Figure 1):

1. Chinese elderly migrants’ perceived stress would be negatively correlated to their life satisfaction.

2. Chinese elderly migrants’ anxiety would mediate the relationship between perceived stress and their life satisfaction.

3. The indirect impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction through anxiety would be dependent on resilience. In particular, anxiety had a negative impact on life satisfaction only for Chinese elderly migrants with lower resilience.

Measures

Participants and procedures

The data in this study came from the Social Science Foundation Project of People’s Republic of China “A follow-up study on the mechanism of intergenerational relationship on the mental health of elderly migrants.” This project was performed from September 2019 to September 2020 in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China. The project firstly randomly selected 7 districts in Nanjing (Qinhuai, Qixia, Gulou, Xuanwu, Jianye, Yuhuatai, and Jiangning District), then randomly selected 3 communities in each district, and finally recruited elderly migrants who met the inclusion criteria in these 21 communities. All participants were told about the study’s purpose and volunteered to take part. A standardized questionnaire was used to conduct face-to-face interviews with all participants. All interviewers had medical research backgrounds and received a uniform and standardized training before the project. This study used the first phase survey data of the project. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≥ 60 years old; (2) household registration not moved to Nanjing; (3) moved to Nanjing ≤ 10 years. Power analysis for a multiple regression was conducted in G*power to determine a sufficient sample size using an alpha of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) (Faul et al., 2009). Based on the aforementioned assumptions, the desired sample size was 229–250 (with the consideration for 10–20% of uncompleted surveys). Following screening, 654 people were chosen for this research finally. The sample size of this study is adequate.

Instruments

Life satisfaction

The elderly migrants’ life satisfaction was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al., 1985). SWLS contains five items. Each item is rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with a total score ranging from 5 to 35. Higher scores reflect higher life satisfaction. The Chinese version has been widely used to measure the life satisfaction of the elderly, with satisfactory reliability and validity (Tian and Wang, 2021). Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.887. In the CFA, GFI = 0.946. This questionnaire is reliable and valid for the measurement of life satisfaction among the elderly migrants.

Perceived stress

The elderly migrants’ perceived stress over the past month was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983). PSS is made up of 14 items and two sub-dimensions: the feeling of being out of control and nervousness. Items 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13 belong to the uncontrollable dimension and are scored in reverse. Items 1, 2, 3, 8, 11, 12, and 14 belong to the nervous dimension. Each item is rated on a scale of 1 (never) to 4 (always), with a total score ranging from 0 to 56. The Chinese version is translated by Yang and has high reliability and validity (Yang and Huang, 2003). Higher scores imply a greater level of perceived stress. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.809. In the CFA, GFI = 0.717. This questionnaire is reliable and valid for the measurement of perceived stress among the elderly migrants.

Anxiety

The elderly migrants’ anxiety was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A) (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). The 7-item scale measured if participants currently experienced the following symptoms. It includes questions like “I feel nervous or excited” and “The concern thoughts always hovering in my mind” on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all, 4 = most of the time). The total score results in a score between 7 and 28. The higher the score, the higher the sense of anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.787. In the CFA, GFI = 0.890. This questionnaire is reliable and valid for the measurement of anxiety among the elderly migrants.

Resilience

The elderly migrants’ resilience was measured using the 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007) the scale contains 10 items. Each item is rated on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always), with a total score ranging from 0 to 50. Several studies have shown that CD-RISC-10 has high reliability and validity in the Chinese population (Zhang et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2022). Higher scores imply a greater level of resilience. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.924. In the CFA, GFI = 0.935. This questionnaire is reliable and valid for the measurement of resilience among the elderly migrants.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Age (in years), gender (0 = female, 1 = male), marital status (0 = single/divorced/widowed, 1 = married), education background (1 = primary school or lower, 2 = middle or high school, 3 = college or above), yearly income (< 5,000 RMB, 5,000 RMB–10,000 RMB, 10,000 RMB–40,000 RMB, > 40,000 RMB), self-reported physical health (from 1 = very unhealthy to 5 = very healthy), duration of migration (in years), social support, and social participation were all control variables.

Data analysis

In this study, we use SPSS25.0 to measure the sample characteristic, the descriptive statistics, and the Pearson correlation analysis. To assess the importance of the mediated models, we used the bootstrapping procedure in Hayes’ PROCESS macro program. According to Mackinnon et al. (2004), we utilized Model 4 to test the indirect influence of perceived stress on life satisfaction through anxiety. Moreover, we tested the moderated mediation in this study by Hayes’s PROCESS macro Model 14. We predicted resilience to moderate the relationship between anxiety and life satisfaction, with the indirect effect depending on resilience level (Hypothesis 3). The bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) determine whether the effects in Model 4 and Model 14 are significantly based on 5,000 random samples (Hayes and Scharkow, 2013). An effect is regarded as significant if the CIs do not include zero.

Results

Common method biases test

Using Harman’s one-way test for all questions on the four scales, it was found that the first common factor analyzed explained only 32.38% (< 40%) of the variance, indicating that there was no serious common method bias in this study despite the use of the questionnaire.

Descriptive data and Pearson correlations

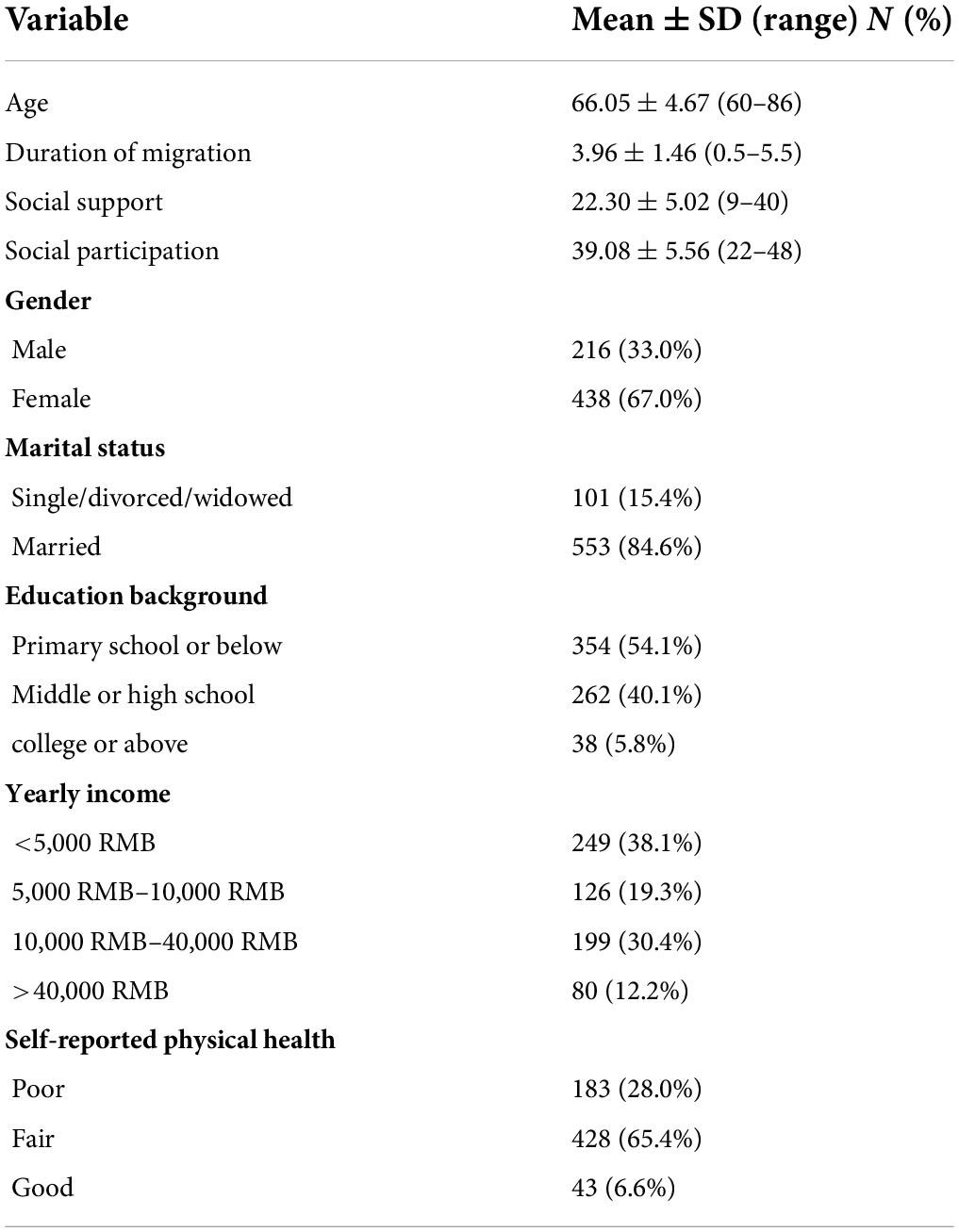

The sociodemographic characteristics were shown in Table 1. 654 elderly migrants had an average age of 66.08 ± 4.67 (range: 60–86) years, with an average of 3.96 ± 1.46 (range: 0.5–5.5) years of migration. The average level of social support is 22.30 ± 5.02 (range: 9–40) and the average level of social participation is 39.08 ± 5.56 (range: 22–48). Most elderly migrants were females (67.0%), married (84.6%), reported primary school or lower (54.1%) and had a fair physical health status (65.4%). The yearly income of most elderly migrants was less than 5,000 RMB (38.1%).

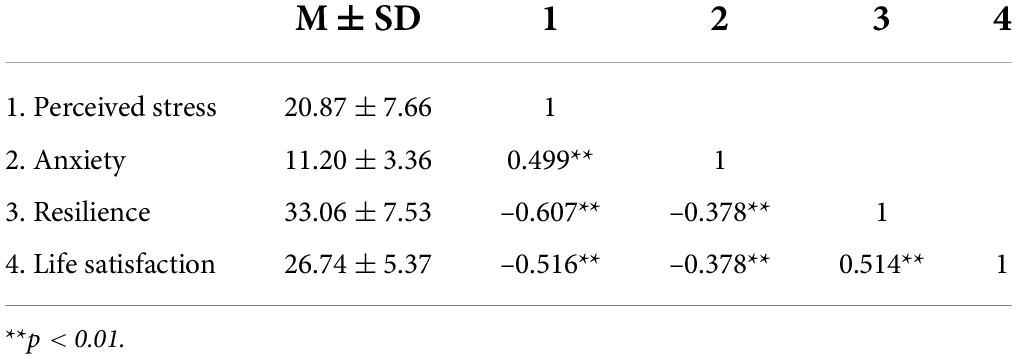

Table 2 presented the Pearson correlations of the study variables. The results indicated that perceived stress (r = –0.516, p < 0.01), anxiety (r = –0.378, p < 0.01), resilience (r = 0.514, p < 0.01) were related to life satisfaction. Perceived stress was positively correlated with anxiety (r = 0.499, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with resilience (r = –0.607, p < 0.01). Anxiety was negative correlated to resilience (r = –0.378, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was verified.

Table 2. Bivariate correlation among perceived stress, anxiety, resilience, and life satisfaction (n = 654).

Mediation analyses

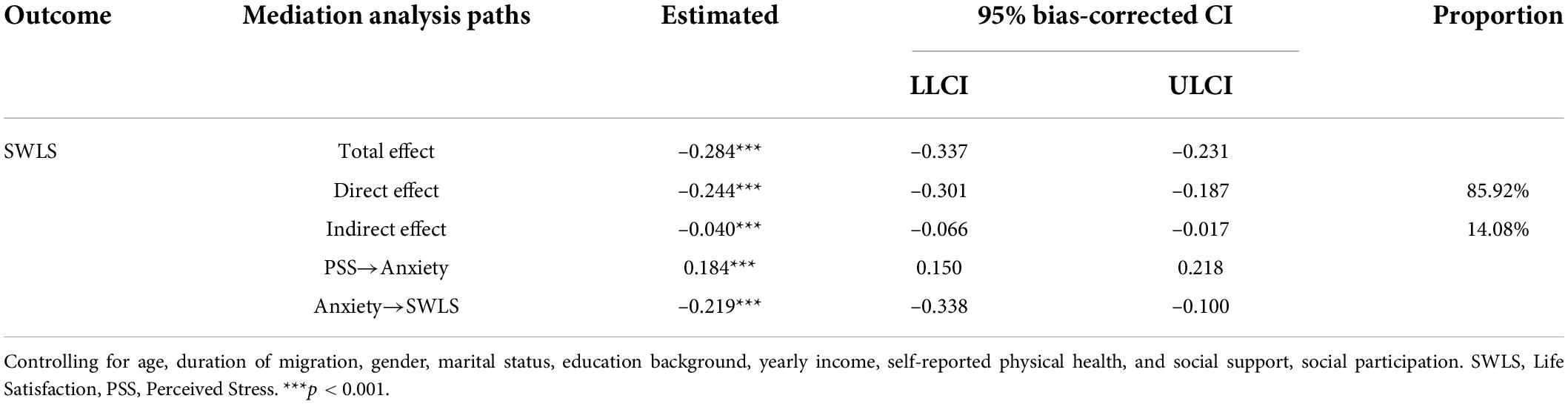

Table 3 showed the indirect impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction via the anxiety. After we controlled for the effects of age, education, etc. the indirect mediated effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction was significant (β = –0.040, CI [–0.066, –0.017]). Perceived stress was a significantly negative predictor on life satisfaction (β = –0.284, CI [–0.337, –0.231]). Perceived stress was a significantly positive predictor of anxiety (β = 0.184, CI [–0.150, –0.218]), while anxiety had a significantly negatively predicted effect on life satisfaction (β = –0.219, CI [–0.338, –0.100]). Moreover, the direct effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction was still significant (β = –0.244, CI [–0.301, –0.187]) when mediating variables were added. Additionally, the upper and lower bounds of the bootstrap 95% CI for the direct effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction and the mediating effect of anxiety did not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect was significant. The mediation effect accounted for 14.08% of the total effect, which confirmed that anxiety played a partial mediating role in the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was verified.

Table 3. Mediation effect of anxiety on the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction (n = 654).

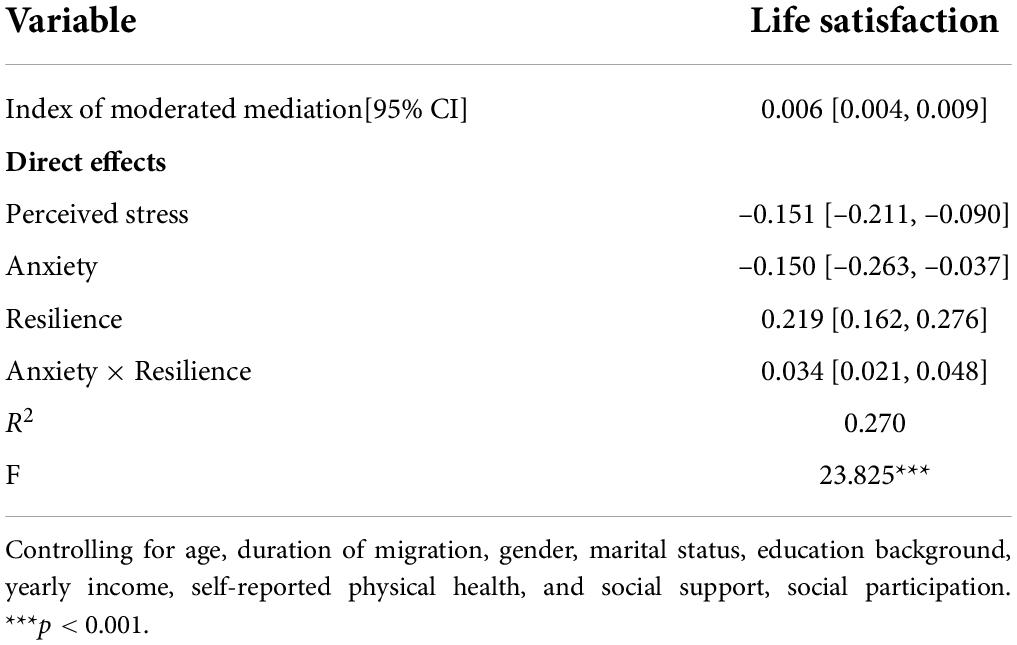

Testing for the moderated mediation

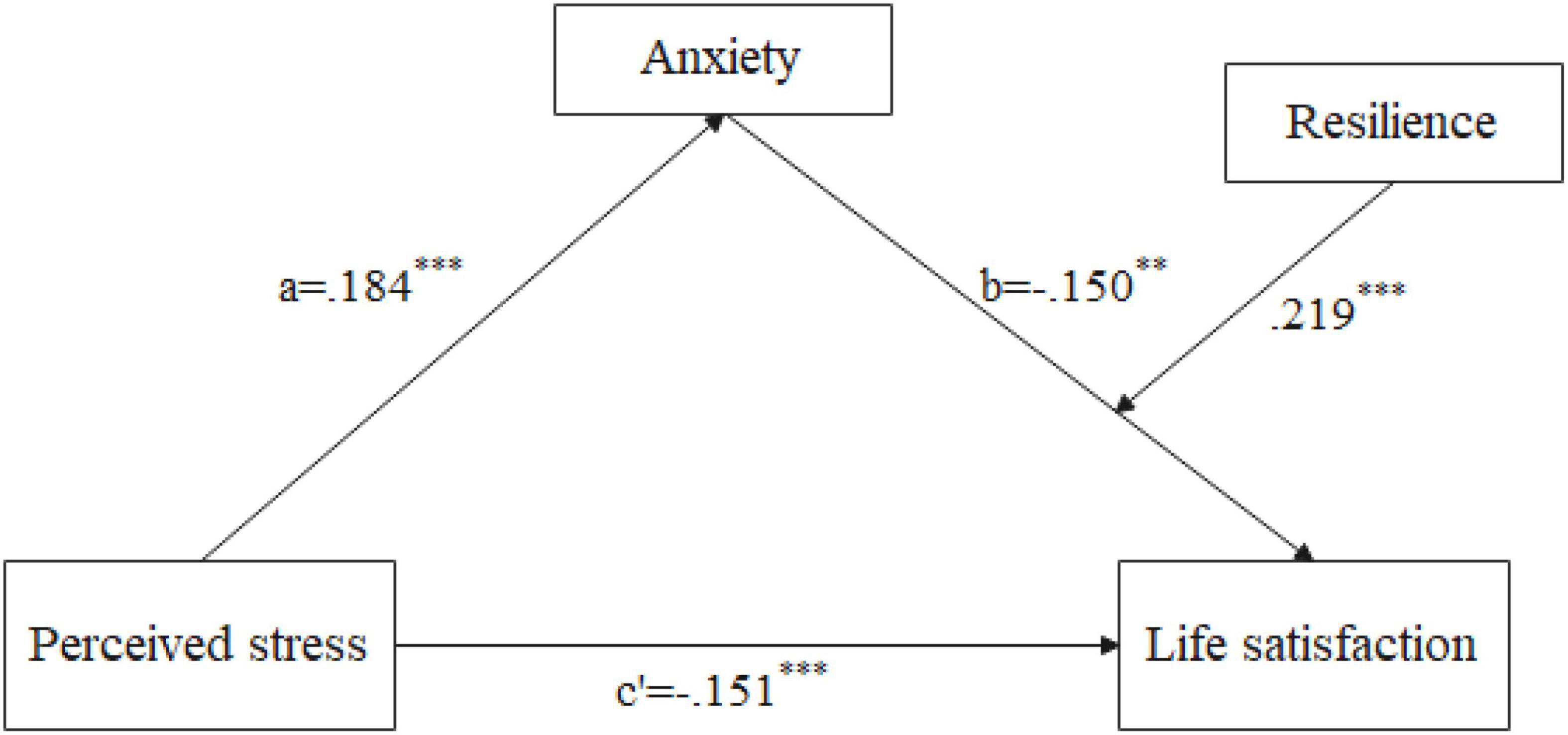

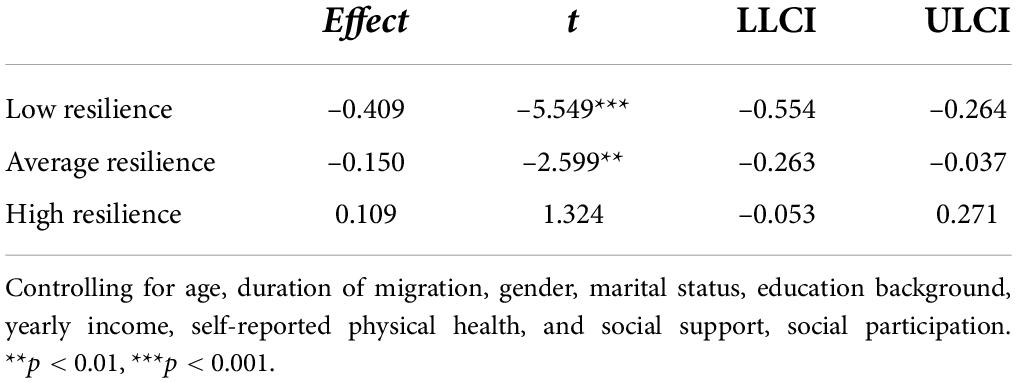

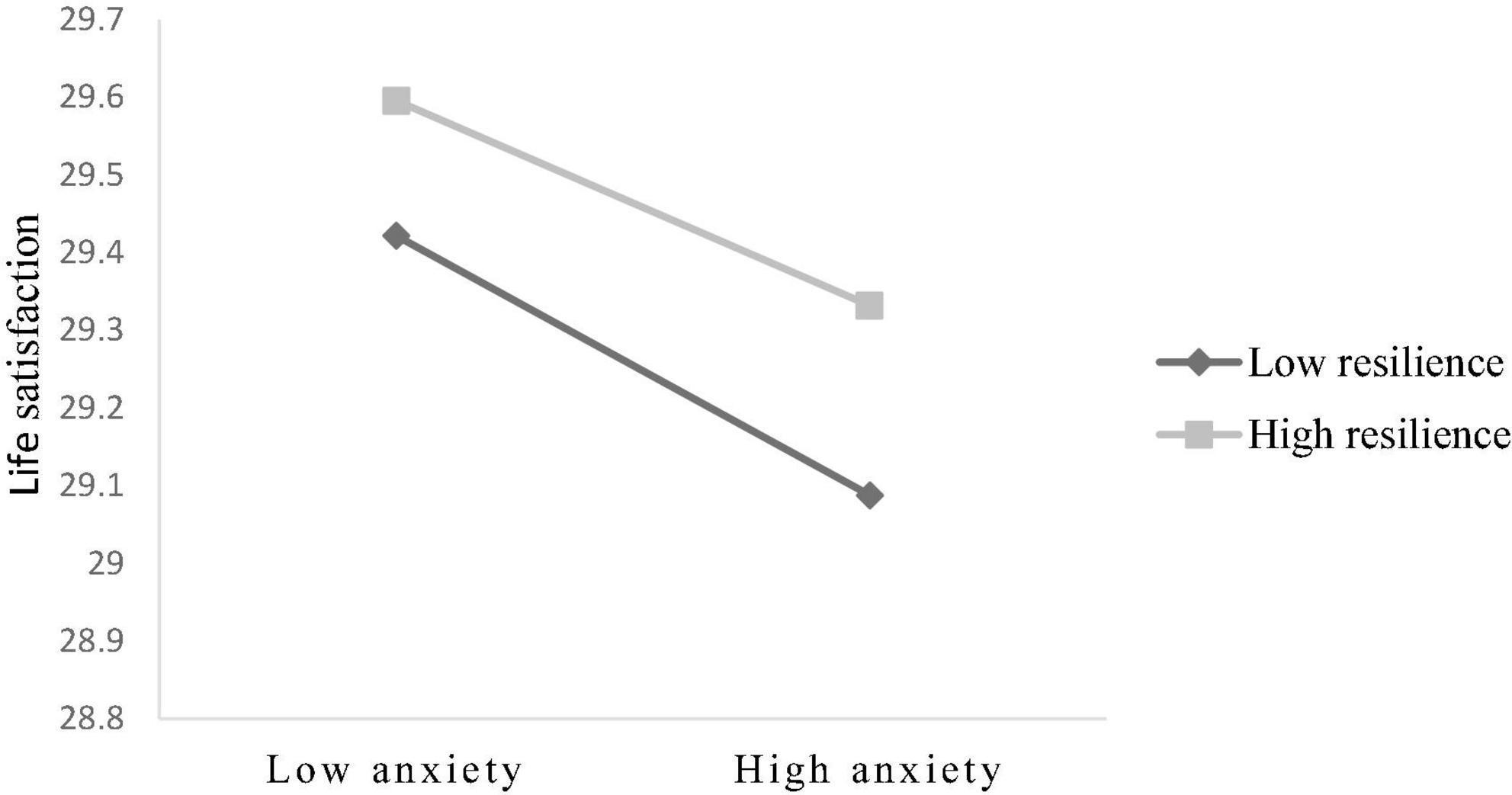

Hypothesis 3 predicted that resilience would moderate the indirect effect in Hypothesis 2. The final moderated mediation model is shown in Figure 2. The indexes of moderated mediation were significant (see Table 4; β = 0.006, 95% CI [0.004, 0.009]), which showed that the indirect effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction via the anxiety varied with the level of resilience. The interaction term anxiety × resilience was significant in the moderated mediation model (see Table 4; β = 0.034, 95% CI [0.021, 0.048]). We graphed the interaction effects in Figure 3 to help explain the interaction outcome. When compared to elderly migrants with high resilience, anxiety had a greater impact on life satisfaction among elderly migrants with poor resilience. Moreover, we showed the indirect impact of the moderator at different values (1 SD below the mean, the mean, and 1 SD above the mean). The indirect effects were significant for elderly migrants with low and average levels of resilience (see Table 5; effectlowlevel = –0.409, t = –5.549, and p < 0.001; effectaveragelevel = –0.150, t = –2.599, and p < 0.01), whereas for elderly migrants with higher resilience, the indirect effect was not significant (see Table 5; effecthighlevel = 0.109, t = 1.324, and p > 0.1). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was verified.

Table 4. The moderated mediation model with anxiety as a mediator and resilience as a moderator (n = 654).

Figure 3. The moderating effect of resilience on the relation between anxiety and life satisfaction.

Discussion

The study’s findings revealed that Chinese elderly migrants’ perceived stress was negative relation to their life satisfaction (Hypothesis 1), and anxiety mediated this connection (Hypothesis 2). Furthermore, anxiety only mediated the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction among Chinese elderly migrants with lower resilience (Hypothesis 3).

Perceived stress and life satisfaction

First, perceived stress was shown to have a substantial influence on the life satisfaction of elderly migrants in China, according to the results of this research, which is consistent with the previous studies showing high perceived stress could lead to poor life satisfaction (Kim, 2019; Xu et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2021; Young and Ah, 2021). In general, elderly migrants in China are more likely to experience stressful events such as concerns about their children’s situation, financial entanglements among family members, and worries about their poor health when they leave their familiar hometowns for reasons such as employment, caring for children or grandchildren, and retirement (Tang et al., 2020). The change of living environment may expose elderly migrants to environmental discomfort, cultural barriers, monotonous spiritual life, low community participation, low identification with urban communities, and the limited access to health service utilization (Song et al., 2017), further increasing perceived stress and causing the accumulation of negative emotions. The pressures of caring for offspring, household chores, and language barriers reduce the leisure time, recreational time, and social participation of elderly migrants. Many elderly migrants are silent and depressed due to the lack of friends and social interaction and even suffer from negative mental outcomes such as loneliness (Olofsson et al., 2021), ultimately causing a decline in life satisfaction.

The mediating role of anxiety

As hypothesized, this study indicated that anxiety mediated the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction, perhaps revealing the underlying mechanism concerning how perceived stress influences life satisfaction indirectly. On the one hand, the primary purpose of mobility for most Chinese migrant older adults is to care for their grandchildren. The caregiver role is burdensome, and perceived stress occurs with increased workload and psychological demands. Caregivers may struggle to balance their caregiving duties with other aspects of their lives but remain silent about the perceived stress, aggravating their mental health and leading to anxiety symptoms (Shi et al., 2020). On the other hand, as they age, elderly migrants experience a further decline in cognitive abilities (Deary et al., 2009) and daily activities, have varying degrees of deteriorating health, and begin to require the care of children, which leads to increased perceived burdensomeness (Jahn et al., 2011). In addition, elderly migrants’ financial resources in their later life are mainly supported by their children (Wu et al., 2005), which to some extent brings a psychological burden to migrant older parents (Shenk, 2001)and endangers sentiments of dependency and lack of autonomy (Silverstein et al., 1996). These dilemmas have led to significantly higher levels of perceived stress among elderly migrants. They lack friends and social interactions (Lin et al., 2020), so that they are unable to dissipate perceived stress and develop psychological problems such as anxiety. Life satisfaction reflects a person’s spiritual and material life level, and anxiety is an important factor affecting the spiritual life level. If a migrant older adult has a high sense of anxiety, his evaluation of his spiritual and material living standards will be relatively low, and his life satisfaction will be further reduced. According to the analysis results, we propose that decreasing elderly migrants’ anxiety was a valid method to improve their life satisfaction. Previous research referred that migrants with poor subjective health status were possible to experience anxiety (Harjana et al., 2021) and reported that physical activity was a favorable element against anxiety among older adults (de Oliveira et al., 2019). And abundant social activities and emotional support from neighbors and friends can help cope with the monotony of daily life and relieve anxiety. Thus, elderly migrants should strengthen physical exercise, improve health self-efficacy, increase communication with family and friends to reduce anxiety levels and ultimately improve their life satisfaction.

The moderating role of resilience

The present study also examined whether resilience moderated the association between anxiety and life satisfaction among elderly migrants in China. Resilience was discovered to be a facilitator of life satisfaction among elderly migrants, which supports the previous findings (Foster et al., 2019). Especially, this study discovered that resilience moderated the connection between anxiety and life satisfaction of elderly migrants. For elderly migrants with a lower level of resilience, anxiety might have a major influence on their life satisfaction, whereas, for those with a higher resilience level, it has no significant impact. Resilience has an important role in promoting the mental development of individuals, through the buffering effect, challenging effect and compensating effect, reducing anxiety symptoms, enhancing the strength of individuals when experiencing difficulties and adverse events, stimulating the potential of individuals (Li and Sun, 2014). Elderly migrants with more resilience have an optimistic view of life, are more psychologically healthy (Schoenmakers et al., 2017), maintain moderate communication and exchange with family members, and receive timely emotional support, respect, and help (Cao and Liang, 2020). The feeling of resilience might reduce older adults’ likelihood of indulging in anxiety. Therefore, this would make anxiety’s effect on life satisfaction non-significant. However, elderly migrants who lack resilience have insufficient psychological and social resources available, lack problem-solving ability and confidence. As a result, when they indulged in anxiety, they lacked the psychological resources to help them recover quickly and cope successfully, ultimately leading to a decrease in life satisfaction. It can be concluded that anxiety is a risk factor for reducing life satisfaction of the elderly migrants with lower resilience when compared to those with greater resilience. In future research and practical work on the life satisfaction of elderly migrants, resilience construction needs to be strengthened. It is necessary to further strengthen family and social support, increase protective resources against stress, and improve the adaptability and sense of belonging of elderly migrants. It is suggested that communities should actively carry out cultural activities, emphasize and pay attention to the cultural aging of the elderly (Du et al., 2018), and help to make more friends, which is conducive to timely emotional support for the elderly migrants, reduce anxiety, enhance the sense of belonging, and achieve higher life satisfaction through positive social relationships.

Limitations and future studies

Some limitations should be improved in a future study. First of all, multiple assessment methods need to be considered to lower the subjective impact of self-report measures. Secondly, a cross-sectional survey was used in our paper, and the results could not determine causal inferences. In the future, additional research about the associations between perceived stress and life satisfaction could be undertaken, such as longitudinal studies. Furthermore, other variables could be dug out to explain the underlying psychological mechanisms between perceived stress and life satisfaction, such as loneliness, depression, social participation, self-efficacy, and so on. In addition, because this study used a questionnaire, older adults who were able to communicate smoothly with the interviewer and had no mobility impairment were enlisted to take part in this study. Future research should consider using other approaches to survey elderly migrants with cognitive impairments and limited mobility in daily activities in order to generalize the results to a larger population of elderly migrants.

Implications

In summary, this was one of a few studies testing the mediating and moderating effects of anxiety and resilience on the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction among elderly migrants in China. Our findings not only suggested that elderly migrants’ life satisfaction could be affected by perceived stress through anxiety. This study also found that resilience could moderate the path way of anxiety to life satisfaction thus alleviating the indirect impact of perceived stress on life satisfaction, and anxiety had a negative impact on life satisfaction only for Chinese elderly migrants with lower resilience.

Conclusion

Given these conclusions, we make the following recommendations. First, helping elderly migrants relieve perceived stress and anxiety is needed. On the one hand, when elderly migrants are caught in high perceived stress and anxiety, family and friends should give them enough emotional support (Liu et al., 2021). Teach them to release stress appropriately and listen carefully to their needs. On the other hand, more incentives or promotions should be arranged for elderly migrants to participate in these local social activities, such as community sports and physical exercise (Gao et al., 2014). As prior study (Tang et al., 2020) discovered that local friends accumulated social capital for migrants, and helped the seniors to rebuild social networks and gain more emotional support. Their circles of local friends needed to be rebuilt (Lin et al., 2020). These are beneficial to improve their physical and mental health and expand social network, and ultimately relieve anxiety. Second, we suggest that making elderly migrants promote resilience is an effective way to improve their life satisfaction. Third, proposing local registered residents treat elderly migrants more equally, and developing self-identity among elderly migrants. A better social, economic, and cultural environment can benefit internal migrants’ health status (Lin et al., 2016).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing Medical University. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation.

Author contributions

YH: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. LZ, SY, and RD: investigation, formal analysis, and writing—review and editing. HW: formal analysis and writing—review and editing. WZ: conceptualization, investigation, and writing—review and editing. JY: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China “A follow-up study on the mechanism of intergenerational relationship on the mental health of elderly migrants” (18BRK026).

Acknowledgments

We thank all investigators and community managers who participated in this work, as well as all elderly migrants who volunteered to participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abreu, L., Oquendo, M. A., Galfavy, H., Burke, A., Grunebaum, M. F., Sher, L., et al. (2018). Are comorbid anxiety disorders a risk factor for suicide attempts in patients with mood disorders? A two-year prospective study. Eur. Psychiatry 47, 19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.09.005

Alizadeh-Khoei, M., Mathews, R. M., and Hossain, S. Z. (2011). The role of acculturation in health status and utilization of health services among the iranian elderly in metropolitan Sydney. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 26, 397–405. doi: 10.1007/s10823-011-9152-z

Andreescu, C., and Lee, S. (2020). Anxiety Disorders in the Elderly. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1191, 561–576. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_28

Azpiazu Izaguirre, L., Fernández, A. R., and Palacios, E. G. (2021). Adolescent Life Satisfaction Explained by Social Support, Emotion Regulation, and Resilience. Front. Psychol. 12:694183. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.694183

Babazadeh, T., Sarkhoshi, R., Bahadori, F., Moradi, F., and Shariat, F. (2016). Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress disorders in elderly people residing in Khoy, Iran (2014-2015). J. Res. Clin. Med. 4, 122–128. doi: 10.15171/jarcm.2016.020

Balsamo, M., Cataldi, F., Carlucci, L., and Fairfield, B. (2018). Assessment of anxiety in older adults: A review of self-report measures. Clin. Interv. Aging 13, 573–593. doi: 10.2147/cia.S114100

Baxter, A. J., Scott, K. M., Vos, T., and Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol. Med. 43, 897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X

Bhugra, D. (2004). Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 109, 243–258. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00246.x

Brailovskaia, J., Schönfeld, P., Zhang, X. C., Bieda, A., Kochetkov, Y., and Margraf, J. (2018). A cross-cultural study in Germany, Russia, and China: Are resilient and social supported students protected against depression, anxiety, and stress? Psychol. Rep. 121, 265–281. doi: 10.1177/0033294117727745

Brown Wilson, C., Arendt, L., Nguyen, M., Scott, T. L., Neville, C. C., and Pachana, N. A. (2019). Nonpharmacological Interventions for Anxiety and Dementia in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 59, e731–e742. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz020

Campbell-Sills, L., and Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma Stress 20, 1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271

Cao, Q., and Liang, Y. (2020). Perceived social support and life satisfaction in drug addicts: Self-esteem and loneliness as mediators. J. Health Psychol. 25, 976–985. doi: 10.1177/1359105317740620

Chen, J. (2011). Internal migration and health: Re-examining the healthy migrant phenomenon in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 72, 1294–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.016

Chen, L., Zhong, M., Cao, X., Jin, X., Wang, Y., Ling, Y., et al. (2017). Stress and self-esteem mediate the relationships between different categories of perfectionism and life satisfaction. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 12, 593–605. doi: 10.1007/s11482-016-9478-3

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., and Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

Das, A., Sil, A., Jaiswal, S., Rajeev, R., Thole, A., Jafferany, M., et al. (2020). A Study to Evaluate Depression and Perceived Stress Among Frontline Indian Doctors Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 22:20m02716. doi: 10.4088/PCC.20m02716

de Oliveira, L., Souza, E. C., Rodrigues, R. A. S., Fett, C. A., and Piva, A. B. (2019). The effects of physical activity on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in elderly people living in the community. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 41, 36–42. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0129

Deary, I. J., Corley, J., Gow, A. J., Harris, S. E., Houlihan, L. M., Marioni, R. E., et al. (2009). Age-associated cognitive decline. Br. Med. Bull. 92, 135–152. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp033

Diener, E. (1996). Traits can be powerful, but are not enough: Lessons from subjective well-being. J. Res. Pers. 30, 389–399. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.1996.0027

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dietzel-Papakyriakou, M., and Olbermann, E. (1996). Social networks of elderly migrants: On the relevance of familial and intra-ethnic support. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 29, 34–41.

Du, B., Cao, G., and Xu, F. (2018). Analysis on health status and medical service utilization among the migrant elderly in China. Chin. J. Health Policy 11, 10–16.

El-Gabalawy, R., Mackenzie, C., Thibodeau, M., Asmundson, G., and Sareen, J. (2013). Health anxiety disorders in older adults: Conceptualizing complex conditions in late life. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 1096–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.010

Familiar, I., Borges, G., Orozco, R., and Medina-Mora, M. E. (2011). Mexican migration experiences to the US and risk for anxiety and depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 130, 83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.025

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., and Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/brm.41.4.1149

Foster, K., Roche, M., Delgado, C., Cuzzillo, C., Giandinoto, J. A., and Furness, T. (2019). Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 28, 71–85. doi: 10.1111/inm.12548

Gana, K., Bailly, N., Saada, Y., Joulain, M., Trouillet, R., Hervé, C., et al. (2013). Relationship between life satisfaction and physical health in older adults: A longitudinal test of cross-lagged and simultaneous effects. Health Psychol. 32:896. doi: 10.1037/a0031656

Gao, X., Chan, C. W., Mak, S. L., Ng, Z., Kwong, W. H., and Kot, C. C. (2014). Oral health of foreign domestic workers: Exploring the social determinants. J. Immigr. Minor Health 16, 926–933. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9789-5

Hamarat, E., Thompson, D., Zabrucky, K. M., Steele, D., Matheny, K. B., and Aysan, F. (2001). Perceived stress and coping resource availability as predictors of life satisfaction in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Exp. Aging Res. 27, 181–196. doi: 10.1080/036107301750074051

Harjana, N. P. A., Januraga, P. P., Indrayathi, P. A., Gesesew, H. A., and Ward, P. R. (2021). Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Repatriated Indonesian Migrant Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 9:630295. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.630295

Hayes, A. F., and Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 24, 1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187

Hoseini-Esfidarjani, S. S., Tanha, K., and Negarandeh, R. (2022). Satisfaction with life, depression, anxiety, and stress among adolescent girls in Tehran: A cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 22:109. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03757-x

Hou, Z., Wang, H., Liang, D., and Zhang, D. (2021). Achieving Equitable Social Health Insurance Benefits in China: How Does Domestic Migration Pose a Challenge? Research Square [Preprint]. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-370136/v1

Hu, J., Huang, Y., Liu, J., Zheng, Z., Xu, X., Zhou, Y., et al. (2022). COVID-19 Related Stress and Mental Health Outcomes 1 Year After the Peak of the Pandemic Outbreak in China: The Mediating Effect of Resilience and Social Support. Front. Psychiatry 13:828379. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.828379

Hu, T., Zhang, D., and Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Pers. Individ. Differ. 76, 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

Hwang, Y.-J., and Hyeseong, J. (2020). A Relation Between Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction in the Elderly-Mediating Effects of Emotional Interaction Between Couples and Self-acceptance [노인의 지각된 스트레스와 삶의 만족도의 관계에서 부부의 정서적 상호작용과 자기수용의 매개효과]. Fam. Fam. Ther. 28, 161–181. doi: 10.21479/kaft.2020.28.2.161

Jahn, D. R., Cukrowicz, K. C., Linton, K., and Prabhu, F. (2011). The mediating effect of perceived burdensomeness on the relation between depressive symptoms and suicide ideation in a community sample of older adults. Aging Ment. Health 15, 214–220. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501064

Kandola, A., and Stubbs, B. (2020). Exercise and Anxiety. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1228, 345–352. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_23

Kim, B. J., Sangalang, C. C., and Kihl, T. (2012). Effects of acculturation and social network support on depression among elderly Korean immigrants. Aging Ment. Health 16, 787–794. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.660622

Kim, K. (2019). The Relationship between Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction of Soldiers: Moderating Effects of Gratitude. Asia Pac. J. Converg. Res. Interchange 5, 1–8. doi: 10.21742/apjcri.2019.12.01

Kumpfer, K. L. (2002). “Factors and processes contributing to resilience,” in Resilience and Development. Longitudinal Research in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Series, eds M. D. Glantz and J. L. Johnson (Boston, MA: Springer), 179–224. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47167-1_9

Labrague, L. J., and De Los Santos, J. A. A. (2020). COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121

Lee, J., Kim, E., and Wachholtz, A. (2016). The effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction : The mediating effect of self-efficacy. Ch’ongsonyonhak Yongu 23, 29–47. doi: 10.21509/KJYS.2016.10.23.10.29

Levecque, K., Lodewyckx, I., and Vranken, J. (2007). Depression and generalised anxiety in the general population in Belgium: A comparison between native and immigrant groups. J. Affect. Disord. 97, 229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.022

Li, H., and Kong, F. (2022). Effect of Morbidities, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life among Migrant Elderly Following Children in Weifang, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:4677. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084677

Li, W., and Sun, J. (2014). The mental health status of retired old people and its relationship with social support and psychological resilience. Chin. Gen. Pract. 17, 1898–1901. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Li, Y., and Dou, D. (2022). The influence of medical insurance on the use of basic public health services for the floating population: The mediating effect of social integration. Int. J. Equity Health 21:15. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01623-6

Lin, Y., Chu, C., Chen, Q., Xiao, J., and Wan, C. (2020). Factors influencing utilization of primary health care by elderly internal migrants in China: The role of social contacts. BMC Public Health 20:1054. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09178-3

Lin, Y., Zhang, Q., Chen, W., Shi, J., Han, S., Song, X., et al. (2016). Association between Social Integration and Health among Internal Migrants in ZhongShan, China. PLoS One 11:e0148397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148397

Liu, S., Hu, C. X., and Mak, S. (2013). Comparison of health status and health care services utilization between migrants and natives of the same ethnic origin—the case of Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 606–622. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10020606

Liu, Y., Li, L., Miao, G., Yang, X., Wu, Y., Xu, Y., et al. (2021). Relationship between Children’s Intergenerational Emotional Support and Subjective Well-Being among Middle-Aged and Elderly People in China: The Mediation Role of the Sense of Social Fairness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:389. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010389

Mackinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., and Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav. Res. 39:99. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

McHugh, R. K., Sugarman, D. E., Meyer, L., Fitzmaurice, G. M., and Greenfield, S. F. (2020). The relationship between perceived stress and depression in substance use disorder treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 207:107819. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107819

Mei, S., Qin, Z., Yang, Y., Gao, T., Ren, H., Hu, Y., et al. (2021). Influence of Life Satisfaction on Quality of Life: Mediating Roles of Depression and Anxiety Among Cardiovascular Disease Patients. Clin. Nurs. Res. 30, 215–224. doi: 10.1177/1054773820947984

Montazeri, A. (2008). Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: A bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 27:32. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-32

Moseley, R. L., Turner-Cobb, J. M., Spahr, C. M., Shields, G. S., and Slavich, G. M. (2021). Lifetime and perceived stress, social support, loneliness, and health in autistic adults. Health Psychol. 40, 556–568. doi: 10.1037/hea0001108

Olofsson, J., Rämgård, M., Sjögren-Forss, K., and Bramhagen, A. C. (2021). Older migrants’ experience of existential loneliness. Nurs. Ethics 28, 1183–1193. doi: 10.1177/0969733021994167

Peavy, G., Mayo, A. M., Avalos, C., Rodriguez, A., Shifflett, B., and Edland, S. D. (2022). Perceived Stress in Older Dementia Caregivers: Mediation by Loneliness and Depression. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 37:15333175211064756. doi: 10.1177/15333175211064756

Plexico, L. W., Erath, S., Shores, H., and Burrus, E. (2019). Self-acceptance, resilience, coping and satisfaction of life in people who stutter. J. Fluency Disord. 59, 52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jfludis.2018.10.004

Randall, A. K., and Bodenmann, G. (2009). The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004

Schoenmakers, D., Lamkaddem, M., and Suurmond, J. (2017). The Role of the Social Network in Access to Psychosocial Services for Migrant Elderly-A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:1215. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14101215

Shenk, D. (2001). Intergenerational family relationships of older women in central Minnesota. Ageing Soc. 21, 591–603.

Shi, J., Huang, A., Jia, Y., and Yang, X. (2020). Perceived stress and social support influence anxiety symptoms of Chinese family caregivers of community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Psychogeriatrics 20, 377–384. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12510

Silverstein, M., Chen, X., and Heller, K. (1996). Too much of a good thing? Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents. J. Marriage Fam. 58, 970–982. doi: 10.2307/353984

Song, X., Zou, G., Chen, W., Han, S., Zou, X., and Ling, L. (2017). Health service utilisation of rural-to-urban migrants in Guangzhou, China: Does employment status matter? Trop. Med. Int. Health 22, 82–91. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12801

Sørensen, T., Hestad, K., and Grov, E. K. (2021). Relationships of Sources of Meaning and Resilience With Meaningfulness and Satisfaction With Life: A Population-Based Study of Norwegians in Late Adulthood. Front. Psychol. 12:685125. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685125

Tambag, H. (2013). Healthy lifestyle behaviors and life satisfaction in elderly. Med. J. Mustafa Kemal Univ. 4:16.

Tan, H. S., Agarthesh, T., Tan, C. W., Sultana, R., Chen, H. Y., Chua, T. E., et al. (2021). Perceived stress during labor and its association with depressive symptomatology, anxiety, and pain catastrophizing. Sci. Rep. 11:17005. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96620-0

Tang, S., Long, C., Wang, R., Liu, Q., Feng, D., and Feng, Z. (2020). Improving the utilization of essential public health services by Chinese elderly migrants: Strategies and policy implication. J. Glob. Health 10:010807. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010807

Tian, H. M., and Wang, P. (2021). The role of perceived social support and depressive symptoms in the relationship between forgiveness and life satisfaction among older people. Aging Ment. Health 25, 1042–1048. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1746738

Van Damme-Ostapowicz, K., Cybulski, M., Galczyk, M., Krajewska-Kulak, E., Sobolewski, M., and Zalewska, A. (2021). Life satisfaction and depressive symptoms of mentally active older adults in Poland: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 21:466. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02405-5

Weger, M., and Sandi, C. (2018). High anxiety trait: A vulnerable phenotype for stress-induced depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 87, 27–37.

Wollny, A. I., and Jacobs, I. (2021). Validity and reliability of the German versions of the CD-RISC-10 and CD-RISC-2. Curr. Psychol. 1–12. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01670-2

Wu, B., Yue, Y., Silverstein, N. M., Axelrod, D. T., Shou, L. L., and Song, P. P. (2005). Are contributory behaviors related to culture? Comparison of the oldest old in the United States and in China. Ageing Int. 30, 296–323.

Xia, Y., and Ma, Z. (2020). Relative deprivation, social exclusion, and quality of life among Chinese internal migrants. Public Health 186, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.038

Xu, X., Chen, L., Yuan, Y., Xu, M., Tian, X., Lu, F., et al. (2021). Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction Among Chinese Clinical Nursing Teachers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Burnout and Emotion Regulation. Front. Psychiatry 12:548339. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.548339

Yang, T. Z., and Huang, H. T. (2003). An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 24, 760–764.

Ye, B., Hu, J., Xiao, G., Zhang, Y., Liu, M., Wang, X., et al. (2021). Access to Epidemic Information and Life Satisfaction under the Period of COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress and the Moderating Role of Friendship Quality. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 17, 1227–1245. doi: 10.1007/s11482-021-09957-z

Young, L. J., and Ah, P. S. (2021). Effect of Perceived Stress on Life Satisfaction in COVID-19 Situations: The Double-Mediating Effect of Gratitude and Depression [코로나19 상황에서 지각된 스트레스가 삶의 만족에 미치는 영향: 감사성향과 우울의 이중매개 효과]. Asia Pac. Converg. Res. Exchange Paper 25, 103–116. doi: 10.36357/johe.2021.25.2.103

Yu, M., Qiu, T., Liu, C., Cui, Q., and Wu, H. (2020). The mediating role of perceived social support between anxiety symptoms and life satisfaction in pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18:223. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01479-w

Yu, X. N., and Liu, C. W. (2018). Study on the anxiety and depression status of elderly people moving with the family and the effect of psychological intervention on them. Imaging Res. Med. Appl. 2, 218–220.

Zhang, D., Wang, R., Zhao, X., Zhang, J., Jia, J., Su, Y., et al. (2021). Role of resilience and social support in the relationship between loneliness and suicidal ideation among Chinese nursing home residents. Aging Ment. Health 25, 1262–1272. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1786798

Keywords: perceived stress, life satisfaction, anxiety, resilience, elderly migrants

Citation: Hou Y, Yan S, Zhang L, Wang H, Deng R, Zhang W and Yao J (2022) Perceived stress and life satisfaction among elderly migrants in China: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 13:978499. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.978499

Received: 26 June 2022; Accepted: 27 July 2022;

Published: 15 August 2022.

Edited by:

Meiling Qi, Shandong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jingjing Zhou, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, ChinaWenpei Zhang, Anhui University of Technology, China

Xin Hong, Nanjing Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China

Copyright © 2022 Hou, Yan, Zhang, Wang, Deng, Zhang and Yao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun Yao, eWFvanVuQG5qbXUuZWR1LmNu

Yanjie Hou

Yanjie Hou Shiyuan Yan1

Shiyuan Yan1 Hao Wang

Hao Wang Jun Yao

Jun Yao