95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 03 October 2022

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.976330

Self-regulation is important in enhancing students’ academic performance, yet evidence for the systematic and valid instruments to measure self-regulated learning strategies of college students in an English as a foreign language context is far from robust. This study was situated to develop an evaluation tool to examine the status quo of self-regulated learning strategies employed by college English learners and the associations between the use of these strategies and their academic achievement. A large-scale survey was conducted at a university in Macau to provide evidence of the construct validity of responses to the questionnaire on self-regulated learning strategies. Conceptualized in social cognitive theory, the questionnaire comprised environmental, behavioral and personal self-regulated learning strategies with 48 items weaving into 10 dimensions. Strong evidence for reliability and validity was found. Findings also revealed that students who intrinsically valued and used more self-regulated learning strategies achieved higher academic performance. Students in advanced-level English course reported significantly more frequent use of self-regulated learning strategies than students in medium-level and mixed-level English courses. Our results draw attention to the pedagogical orientation for teachers of English as a foreign/second language in helping students become adaptive learners with self-regulative process.

Since its inception, self-regulation has been accorded great importance as a 21st-century skill (Trilling, 2009). Schools and universities seek to empower students to become self-regulated learners in the recognition that, in this ongoing fast-changing era, it is a core skill that enables them to monitor the quality of their work and adopt strategies to cope with new and demanding tasks (Panadero et al., 2018). Zimmerman (1989) contended that efficient self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies may facilitate achievements in all academic areas when learners are engaged in a cluster of internal processes that promote adjustments to their knowledge, motivation, behavior, and context. In recent years, different investigations in the education field have manifested the significance of students’ SRL strategies for academic success (Kitsantas et al., 2009; Diseth, 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Fauzi and Widjajanti, 2018; Sutarni et al., 2021).

Previous studies on SRL strategies have laid a promising theoretical foundation, but the validity evidence for a systematic instrument to measure college students’ SRL strategies in English as a foreign language (EFL) contexts is far from robust (Chen et al., 2020). It is particularly rare in regions where English teachers normally work with large student cohorts in each class where learners use fewer SRL strategies than their counterparts do in other countries (Ho, 2004; Lee et al., 2009; Li et al., 2018). To bridge this gap, the current study attempts to examine the status quo of SRL strategies employed by college EFL learners and the associations between SRL strategies and their academic achievements. The outcomes could be used to map out how various SRL strategies might impact English-language learning achievements in an Asian context and could be used for cross-cultural comparisons.

The concept of SRL strategies sprang up in the 1980s under the influence of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986). Bandura’s theory acts as an alternative to Vygotsky’s socio-culturalism and Piaget’s constructivism, which depicts learning processes as reciprocal interactions between cognition, behavior, environment, and other contextual or personal factors. Studies on SRL discuss this reciprocity with a triadic analysis of three component processes: self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction (Kanfer and Gaelick, 1986; Schunk, 1989; Zimmerman, 1989). Here, SRL connotes a more self-directed learning experience by which a learner attempts to control these triadic factors to attain their learning goals. Zimmerman (2002) developed an SRL model to elucidate how students exert specific learning strategies to acquire knowledge. For Zimmerman, learners who can regulate their learning have a clearer idea of what they are doing and can better transform mental abilities into academic skills through such self-regulatory strategies as monitoring, controlling, adjusting, self-directing, and self-assessing. Grounded in Zimmerman’s construct, Boekaerts and Corno (2005) pointed out that self-regulated learners demonstrate several distinctive characteristics. They can be conceived of as (a) adaptive learners with a range of self-regulative processes through which they set goals, manage resources, self-monitor, and seek feedback; (b) positive learners who sustain learning interest and show confidence in achieving learning objectives; and (c) proactive learners who know how to select the best strategies to suit their abilities, based on their self-motivational belief in their strengths and weakness (Zimmerman, 2002).

For SRL skills to be successfully passed to learners and useful for practice, it is necessary to understand the crucial processes involved in the self-regulation of learning. Zimmerman (2002) proposed that students undergo three main cyclical phases when regulating their learning. In the first phase (forethought), learners clarify and share the goals and standards to attain in a certain task. This phase involves students’ perception of the task’s affordances and constraints and their motivation arising from beliefs about learning such as self-efficacy and outcomes expectancy (Ertmer and Newby, 1996; Zimmerman, 2000, 2006). During the second phase (performance), learners engage with the task and monitor their learning, usually deploying planned strategies to compare their progress against standards set in the forethought phase and discover causes of learning events. In the third phase (self-reflection), learners evaluate their work and generate applicable revisions or adjustments thereto. This includes reflecting on feedback and mentally storing ideas and concepts to use in the task. To conclude, self-regulated learners make deliberate and goal-directed efforts to adjust, adapt, or abandon their learning strategies and identify, retrieve, and seek new information for future learning (Winne, 1995; Zimmerman, 2008).

Students must apply relevant strategies when learning. In the field of language learning, self-regulation is emphasized as a crucial factor that sets the scene for improved language competence (Seker, 2015; Oxford, 2016; Bai, 2018). SRL is important and a pressing need in the EFL context, as learners’ language learning is primarily restricted to classroom settings and lacks sufficient interaction opportunities (Kormos and Csizeìr, 2014). It is worth mentioning, though, that self-regulation skills do not develop spontaneously but must be learned (Winne, 2005). Research studies have identified SRL strategies as teachable skills that students can obtain during learning processes (Oxford, 2011; Andrade and Evans, 2012; Teng and Zhang, 2021). A critical approach is to cater to individual students by integrating explicit instruction on SRL skills into the larger context. Several researchers have highlighted the necessity of teachers’ explicitly training their students in self-regulatory techniques. For example, Tseng et al. (2015) suggested English teachers should teach learning strategies clearly, activate learners’ metacognition, and enhance their self-efficacy. By using systematic instructional approaches in guiding SRL, teachers can help university students improve their capabilities by incorporating goal setting, strategy implementation and monitoring, and problem-solving tactics into the writing process (Lam, 2015). Employing a person-centered data analysis approach, Chen et al. (2020) noted that higher achievers in language learning tend to manipulate various SRL strategies. This implies that language teachers can encourage learners to take advantage of these strategies and enrich underachievers’ awareness of using them. There is a positive and constructive link between SRL strategies and language learners’ academic achievements (Teng et al., 2019).

Calls for promoting learners’ SRL strategies are not accidental, as many prospective, experimental, and even cross-disciplinary studies have paid tremendous attention to their significant associations with academic achievements (Gaskill and Hoy, 2002; Garner, 2010; Zheng, 2016).

In a meta-analysis of SRL by Broadbent and Poon (2015), SRL theories were applied to students’ efforts in a triadic loop dealing with learning performance: monitoring learning performance (self-observation), evaluating learning performance (self-judgment), and responding to performance outcomes (self-reaction). Broadbent and Poon (2015) contended that learning is not viewed as a fixed trait and will be more effective if the participant sets goals to attain academic success. If learners possess improved SRL strategies, they generally have better perceptions of course content and can achieve more favorable outcomes (e.g., Chang, 2005; Moseki and Schulze, 2010).

The most comprehensive set of self-regulatory strategies (i.e., metacognitive self-regulation strategies, cognitive strategies, and environment and resource management) has been widely discussed in the sphere of language learning (DiPerna et al., 2002; Tseng et al., 2006). Published literature has well documented that self-regulated learners manipulate a range of these components as part of their learning process to achieve successful outcomes (e.g., Vianty, 2007; Liu and Feng, 2011; Zhang and Seepho, 2013; Rasooli et al., 2014). Pitenoee et al. (2017) asserted that metacognitive strategies are closely tied to the executive control of cognition, which increases students’ achievement scores. EFL students with good metacognitive strategies can plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning processes, leading to more positive academic outcomes (Yang, 2009). Cognitive strategies include several sub-strategies and are classified into two types of processing strategies—surface cognitive and deep cognitive. Deep cognitive strategies (i.e., elaboration, organization, and critical thinking) improve academic achievement, whereas surface strategies (i.e., repetitive rehearsal and rote memorization) usually have negative associations with academic achievement (Akamatsu et al., 2019). Nevertheless, some researchers note that proficient learners demonstrate the integration of surface and deep cognitive strategies in promoting long-term retention of academic tasks (Wolters, 2004; Bayat and Tarmizi, 2010). Another important dimension of SRL strategies, conceptualized as environment and resource management, comprises regulatory strategies that students apply deliberately to manage other resources besides cognition.

Pintrich et al. (1993) offered more dimensions, including (a) time and study environment management (creating a realistic plan and organizing a congruous setting for learning); (b) effort management (coupling persistence with a concentration on learning tasks); (c) peer learning (learning from a study group or friends); and (d) help-seeking (seeking help from peers or instructors where necessary).

Oxford and colleagues reported a broader range of SRL strategies, with six sub-scales: memory strategies, cognitive strategies, compensation strategies, metacognitive strategies, affective strategies, and social strategies (Oxford and Burry-Stock, 1995; Oxford, 1996). In the field of foreign language learning, Oxford (1996, 2011) blazed a trail for other researchers to follow—she ushered in one of the best-known instrument (i.e., Strategy Inventory for Language Learning) and enhanced Strategic Self-Regulation (S2R) Model. Oxford and her colleagues’ intensive and extensive discussions on the complex nature of applying strategies in language learning have laid profound groundwork for SRL strategies as they draw parallels and cement relatedness among various theories, such as self-regulation, mediated language learning, emotion, and learner autonomy (Oxford, 2015, 2016; Pawlak and Oxford, 2018). Bai and Wang (2020, p. 7) claimed a rather long list with nine types of SRL engagements: “(1) goal setting and planning, (2) record-keeping and monitoring, (3) self-consequences (i.e., students arrange rewards or punishment for themselves), (4) self-evaluation, (5) effort regulation, (6) organization and transformation, (7) rehearsal and memorization, (8) seeking social assistance, and (9) seeking opportunities to practice English.” One interesting finding derived from their study was that seven types of SRL strategies were weighed more often by learners, whereas “seeking opportunities to practice English” and “goal setting and planning” played insignificant roles in directing their choice, effort, cognitive engagement, and academic performance.

Although a plethora of research has discussed the link between SRL strategies and learning achievements, several issues remain. Concerns include theoretically important but empirically uncertain questions regarding the use of SRL strategies among college students in the Macau context, the variables affecting their English language proficiency, and the lack of a valid and reliable instrument to measure their SRL strategies for EFL education. An investigation into these factors would be theoretically intriguing and is urgent for the context of the present study, the Macau Special Administrative Region of China. The fundamental law of Macau education system has placed great emphasis on more quality-concerned English classes and launched the appeal of “nurturing students’ attitude and ability of life-long learning” (Education and Youth Affairs Bureau, 2016). Over the past few years, Education and Youth Affairs Bureau has organized meetings with school English teachers concerning SRL strategies, yet the research of these viable means in assisting students’ language learning is rare. Our study filled this gap by addressing and extending these aspects via empirical investigations in the Macau SAR. Such investigations can provide insights to educators in other places similar to Macau.

Investigating the challenges and factors that may affect foreign language learning is pivotal for informing theory, practice, and policy. In a highly dynamic and constantly changing educational landscape, researchers and teachers more than ever need to dissect the field’s challenges and move forward to best serve the shifting needs of language learners. Informed by research from recent decades, Hlas (2018) outlined a bevy of current grand challenges in the EFL context, including a deep delve into measuring progress and learner outcomes (e.g., the specific frameworks or tools influencing learner outcomes, the characteristics of effective assessments for scaffolding students’ language production) and the reliability and validity of teaching/guiding tools (e.g., how educators assess the content validity of guiding tools). Hlas (2018) appealed for more investigation of these tools’ validity, echoing calls by Norris and Pfeiffer (2003), Troyan (2012, 2016), and Tigchelaar et al. (2017). Another grand challenge in the domain of EFL conveys an expectation of moving learners toward higher proficiency (Gitomer and Zisk, 2015). Deciphering this challenge entails investigating the various components that influence foreign language learning achievement, such as the relationship between students’ SRL strategy use and language proficiency. Gaining insights into how SRL may promote English language learning achievements can immensely help EFL or English as a second language (ESL) learners tackle their difficulties (Bai and Wang, 2020). As SRL strategies used by learners with various English language proficiency and cultural backgrounds can provide theoretical insights, our survey included mixed-level learners for a comparison.

The language learning environment is also a grand challenge on which research must center (Tsavga, 2011; Copland et al., 2014). According to Kormos and Csizeìr (2014), foreign language learners learn in impotent language environments. Wei and Su (2012) revealed that, despite the growing population of EFL learners in China, only a tiny fraction (7%) use the target language in their daily lives. Even in regions where English has an official/de facto function (e.g., Hong Kong and Macau), opportunities to interact with these languages in everyday settings are prodigiously few with large class size (Education and Youth Affairs Bureau, 2001; McKay, 2002; Moody, 2009). By contrast, in the ESL context, learners are immersed in a predominantly English-speaking environment.

The most comprehensive view of these differences is presented in the “circles” model (Kachru, 1985), which classifies the world into three circles. The inner circle refers to places such as the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, or Canada, where English is a native language that ESL learners regularly encounter on the streets, in the media, in public services, and through everyday activities. The outer circle comprises countries whose colonial history means English is widely used and spreading daily, like Malaysia and India. Finally, expanding circle countries are those in which English does not play an official or institutional role and is used in more restricted circumstances as a foreign language. In these countries, attaining higher English proficiency is rarely possible, due to the unconducive language environment; thus, some educators believe SRL is particularly important in these contexts. While research on SRL is increasing, the status quo of SRL strategies used by college students learning English in expanding circle regions like Macau remains an enigma. Little is known about an instrument to measure these EFL learners’ SRL strategies; hence, the current study’s focus.

Along with the language learning environment, the immediate focus on instructional quality is another key challenge for providing continuity of learning, especially during the rapid spread of the coronavirus (O’Keefe et al., 2020). During this challenging time, educators must become aware of specific approaches to improve instruction and foster SRL strategies online and outside the physical classroom, since almost every instructor in 2020 must focus more on classroom-to-remote instruction. Foreign language teaching should adapt to this trend by creating better-blended combinations to improve learning strategies and outcomes. The first step in laying a data-informed basis for language teachers and further cultivating learners’ self-regulation of their individualized needs is having a valid instrument to measure students’ SRL strategies. Given the scant support for examining validity of responses to existing instruments, this paper draws on documentary evidence to discuss the construct validity of a questionnaire measuring college students’ SRL strategies. Validity studies are critical ingredients that can inform, justify, and possibly transform educators’ choices on how to support sustainable learning (Wang and Sun, 2020). In what follows, some research instruments will be elaborated, in correlation with their construct validity for measuring students’ SRL strategies.

To measure students’ perceptions of their general learning behaviors and cognitive activities, as well as their general motivation and capacity for SRL, several research instruments have been generated. Existing tools such as the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ; Pintrich et al., 1993), Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI; Schraw and Dennison, 1994), and Learning Strategies questionnaire (LS; Warr and Downing, 2000) have been adopted in a multitude of studies. The psychometric properties of these instruments, however, are regularly questioned in that their predictive value of future learning outcomes is insufficient (Greene et al., 2013; Veenman, 2005). More to the point, these instruments do not cover the full range of SRL activities and are not specifically designed for the field of foreign language learning. Oxford (1990) Strategy Inventory for Language Learning embraced multifold learning strategies regarding memory, cognitive, compensation, metacognitive, affective and social factors, yet did not derive from the self-regulation theory and failed to indicate iterative SRL phases (Wang and Bai, 2017). In the context of EFL writing, Teng and Zhang (2016) developed a multidimensional questionnaire that measures cognitive, metacognitive, social–behavioral, and motivational regulation aspects in Chinese undergraduate students’ writing. Guided by social cognitive concept and SRL framework, Wang and Bai (2017) research instrument presented high internal consistency (0.92) and test-retest reliability (0.79). The external aspect of construct validity of Wang and Bai scale was also high (Chen et al., 2020). However, their instrument was validated based on the data from secondary school students and may not allow researchers to draw conclusions relative to college students due to the possible disparities in the nature and development of SRL between college students and students of other age groups (Schneider, 2008). There is a need to tailor the measurement of SRL strategies to the specific domain (e.g., higher education) and develop a new and valid instrument to particularly deal with EFL learners in Macau context. Therefore, this study is to validate a new instrument designed to measure Macau college students’ use of SRL strategies, i.e., English Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (ESRLQ) (see the Appendix).

Wang and Bai (2017) validation study suggested that research on language learner self-regulation could comply with Messick’s (1995) test validity model, which encompasses six additional components to support the meaning of measures, with validity being conceptualized as “a single unitary construct” (Wang and Bai, 2017, p. 932). The unified validity theory places construct validity (i.e., the meaning of measures) at its core and highlights six forms of validity evidence—content, substantive, structural, generalizability, external, and consequential—that can be applied to any measurement of educational or psychological constructs (Messick, 1989, 1995).

Per Messick and other researchers (e.g., Zumbo, 2009; Forer and Zumbo, 2011), these complementary forms of validity evidence cannot function in isolation. Therefore, this study examined two aspects of construct validity to contribute to the effective measurement of SRL strategies and advance the understanding of theoretical functions of SRL for promoting learning achievement. Another aim of this study is to insert some subscales that former studies did not consider and support the suitability of using self-regulation in the EFL context.

The following research questions guided this study:

1. What is the evidence regarding the structural aspects of the construct validity of responses to ESRLQ?

2. What is the evidence regarding the external aspects of the construct validity of responses to ESRLQs?

3. What is the status quo of college students’ use of SRL strategies in Macau and how is the use of these strategies related to English language proficiency?

4. Are there differences between college students’ use of SRL strategies and their English language proficiency across various levels in the English course?

Volunteer participants were recruited from Macau University of Science and Technology during the first semester of the 2020/2021 academic year. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and carried out in accordance with the institutional requirements. The researchers obtained informed consent from all students before conducting the survey. Meticulous attention was paid to research consent, benefits, privacy, and confidentiality, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. The sample comprised 598 undergraduate students from 22 classes. Approximately 48% (n = 286) were enrolled in a required Level One English course, 42% (n = 250) in a Level Two course, and 10% (n = 62) in two mixed-level classes for students admitted in or before the 2018/2019 academic year. These students spend 2 h each week in class and approximately two additional hours each week doing homework for the English class. Approximately 43% of the participants were male (n = 255) and 57% were female (n = 343). Participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 26 (M = 18.52, SD = 1.33) and their years of English learning ranged from 0 to 23 years (M = 11.00, SD = 2.75). The participants were from diverse academic faculties, including School of Business, Faculty of Law, Faculty of Chinese Medicine, Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism Management, University International College, and Faculty of Humanities and Arts. The context of leveled and mixed ability groups provided accountable data for further multi-trait comparisons.

The overwhelming majority of Level One/Two participants were in their first year, while the students in the mixed-level classes were juniors or seniors. All students were required to earn required general English education credits in their first academic year, but the university sorted them into different course levels based on their English language test in the Gaokao or the Joint Admission Exam (both are further elaborated in the following section). As the research was carried out in the autumn term, students with the highest proficiency level were enrolled in Level Two and students at the medium level were in Level One. The two mixed-level classes primarily contained students who had failed either Level One or Level Two in a previous academic term. Lecture periods typically comprised a weekly 3-h session for Level One and Level Two and two 2-h sessions for the mixed-level course.

This research progressed through three stages. At the first stage, the conceptual stage was oriented toward questionnaire item generation by exploring the existing literature and consulting with several well-versed practitioners in the field. A pilot study was then conducted in the second stage to determine the framework of ESRLQ. A subsequent interview with 10 first-year students from the 2019/2020 academic year was used to confirm that the items in ESRLQ were appropriate for this population. The third stage involved scrutiny of the psychometric properties of the updated ESRLQ using confirmatory factor analysis.

A feasible and reliable questionnaire from Wang and Bai (2017) was selected. However, since it was not specifically designed for undergraduate students and that some items were out-of-date, the authors developed and produced a new item pool from which the English self-regulated learning questionnaire (ESRLQ) was finalized. Some items were altered to fit the Macau context after receiving expert reviews and student feedback on the pilot study. For example, two items were least endorsed by participants because both concerned “writing”—something students seldom do now. Accordingly, “Write an outline after reading an English article” was modified to “Rethink its main content after reading an English article,” while “Write learning experience articles or diaries about how I feel about my English learning” became “Keep records for my feeling about my English learning.”

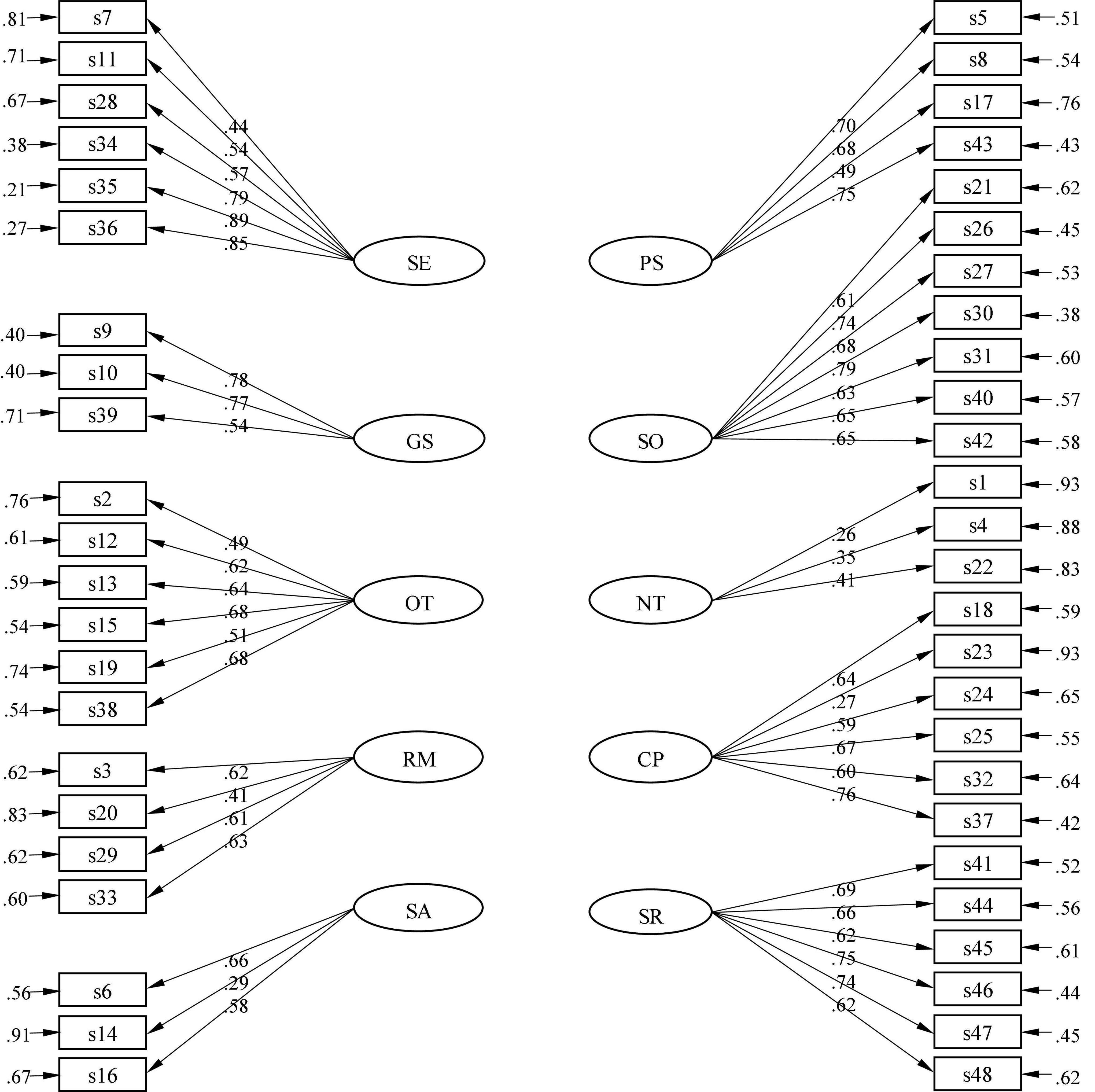

In line with Zimmerman and Risemberg (1997) reconsidered SRL framework, ESRLQ also comprises environmental SRL strategies, behavioral SRL strategies and personal SRL strategies with multiple categories. There are 48 items weaving into 10 dimensions: (a) Self-Evaluation (Items 7, 11, 28, 34, 35, 36); (b) Goal-Setting and Planning (Items 9, 10, 39); (c) Organizing and Transforming (Items 2, 12, 13, 15, 19, 38); (d) Review and Memorization (Items 3, 20, 29, 33); (e) Seeking Social Assistance (Items 6, 14, 16); (f) Persistence (Items 5, 8, 17, 43); (g) Seeking Opportunities (Items 21, 26, 27, 30, 31, 40, 42); (h) Notes Taking (Items 1, 4, 22); (i) Comprehension (Items 18, 23, 24, 25, 32, 37); and (j) Self-Reflection (Items 41, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48). The subscale of self-reflection was first constructed to capture how students interpret and analyze their learning progress, as it may help them self-regulate and solidify what they have learned. A Likert scale of 0–3 was used to measure students’ use of their SRL strategies with 0 standing for “I never use it,” 1 for “seldom use,” 2 for “use it sometimes,” and 3 for “often use.”

The research team received participants’ permission to access their official English final grades at the end of the semester. Participants’ academic achievement was evaluated based on their final reading test score, taken from university records. The grade scale ranges from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 100, with higher scores indicating greater English language proficiency. For each final, members of the panel of expert or experienced tertiary educators are invited to collaborate in designing the test. They hold meetings to scrutinize the course objectives and make sure the test martial must cover all relevant parts of the course it aims to measure, so as to maintain the norms and the content validity of the exam. The average score of the participants on this exam was 62.56 with a standard deviation of 18.97.

Gaokao, a standardized test administered annually in mainland China, is commonly known as the national university entrance exam and also viewed as China’s version of the American SAT and British A-level exams. One of the mandatory Gaokao exams is the English language test. The English language test consists of three sections (i.e., reading comprehension, language use, and practical writing) and the full mark of English language test accounts for 150 in most places while only a few provinces have 120 in total score. Gaokao English results are important because students with a higher score are assumed to be more proficient in the language, which increases the possibility of being enrolled to a top-tier university. Notwithstanding the fact that some top test-takers in Gaokao English exam may be questioned about their practical communication competence with native speakers, universities still accept the score as a basis for direct entry and it also witnesses an uptrend in western institutions to take Gaokao result as a measure of academic competence (Farley and Yang, 2019). The validity of Gaokao is particularly vital seeing that it plays a decisive role in selecting talents in China. With legitimate concerns on this issue, a number of researchers sought to validate Gaokao tests using the conceptual framework coined by long-established experts (e.g., Messick, 1995; Bachman and Palmer, 1996) and constituted proof that Gaokao is a kind of norm-referenced test which bears high degree of correlation efficiency between academic performance and Gaokao results, and therefore, it has high reliability and validity on average (Tu, 2018; Su, 2021; Zhang, 2021). Gaokao English results of the participants in the current study ranged from 20 to 142 with the mean score of 113.44 (SD = 21.90).

The English Language Test in the joint admission exam (JAE) represents a local student’s language proficiency as it is the admission examination jointly organized by four higher education institutions in Macau (i.e., University of Macau, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau Institute for Tourism Studies, and Macau Polytechnic Institute). Only Chinese, Portuguese, English, and Mathematics are on the JAE; other subjects are tested by institutions individually. The JAE English language test (JAE-E), per the announced syllabus, corresponds to the Common European Framework of Reference (Examination Syllabus and Past Examination Papers, 2021).

The 120-min test is composed of Language Use (40 marks), Reading Comprehension (30 marks), and Essay Writing (30 marks); exam questions are set at a variety of levels, including Elementary (CEFR A2), Pre-Intermediate (CEFR B1), Intermediate (CEFR B2), and Upper-Intermediate/Advanced (CEFR C1). The final mark received by the local student in Macau is generally a weighted sum of their subject marks (the full mark is 1,000). Every year, around ten academic members from the four institutions constitute a committee to jointly organize and administer the exam. To understand the construct and content validation of JAE-E, Ho et al. (2021) utilized two instruments (Coh-Metrix and CEFR scales with descriptors) while Kunnan and Yao (2020) drew on teachers’ ratings of task types in JAE-E. Their studies specified that on the whole the JAE-E was valid with regard to its content. Participants were asked to provide their English JAE grade, which ranged from 164 to 807 with a mean of 561.18 (SD = 167.34).

As the range of scores differ between the Gaokao and JAE, all the raw scores were transformed into z-scores and then back-transformed into standardized scores with the same mean (62.56) and standard deviation (18.97) with the final English language Examination. This is reducing the chance of the violation of homogeneity of variance in statistical analysis. The transformed scores keep the rankings of the raw scores.

The structural aspect of the validity of participants’ responses to the survey was checked with Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Instead of using Hu and Bentler’s (1999) two-index strategy in model fit for the goodness of fit indices, a combination of multiple indices was used to judge the model fit: comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the 90% confidence intervals of RMSEA. This is because some research studies have questioned the validity of the two-index strategy suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) in model fit assessment (Marsh et al., 2004; Fan and Sivo, 2005). The suggestions to add paths from observable to latent variables were not followed either to avoid mechanically fitting the model without theoretical justifications (MacCallum et al., 1992). Error covariances between observable variables within each latent construct were not added (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Structure of English self-regulated learning questionnaire. SE, Self-Evaluation; GS, Goal-Setting and Planning; OT, Organizing and Transforming; RM, Review and Memorization; SA, Seeking Social Assistance; PS, Persistence; SO, Seeking Opportunities; NT, Notes Taking; CP, Comprehension; SR, Self-Reflection. All the factors are correlated with each other. The correlations ranged from 0.59 to 0.95 with a mean of 0.76 and standard deviation of 0.10. These correlation coefficients were not presented in figure for the sake of clarity.

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to check the external aspects of the construct validity by correlating the use of SRL strategies measured by ESRLQ with student performance on two English examinations: Gaokao/JAE English test score for comprehensive English language proficiency and the final English exam score measured at the end of the semester for English language reading competence. Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was employed to compare the SRL strategy use as well as the comprehensive English language proficiency and English language reading competence between the three cohorts: Level 1, Level 2, and Mixed Levels. The number of years studying English was used as a covariant. Effect size (partial eta squared) was reported as small (0.01), medium (0.06), or large (0.14) according to Cohen (1988).

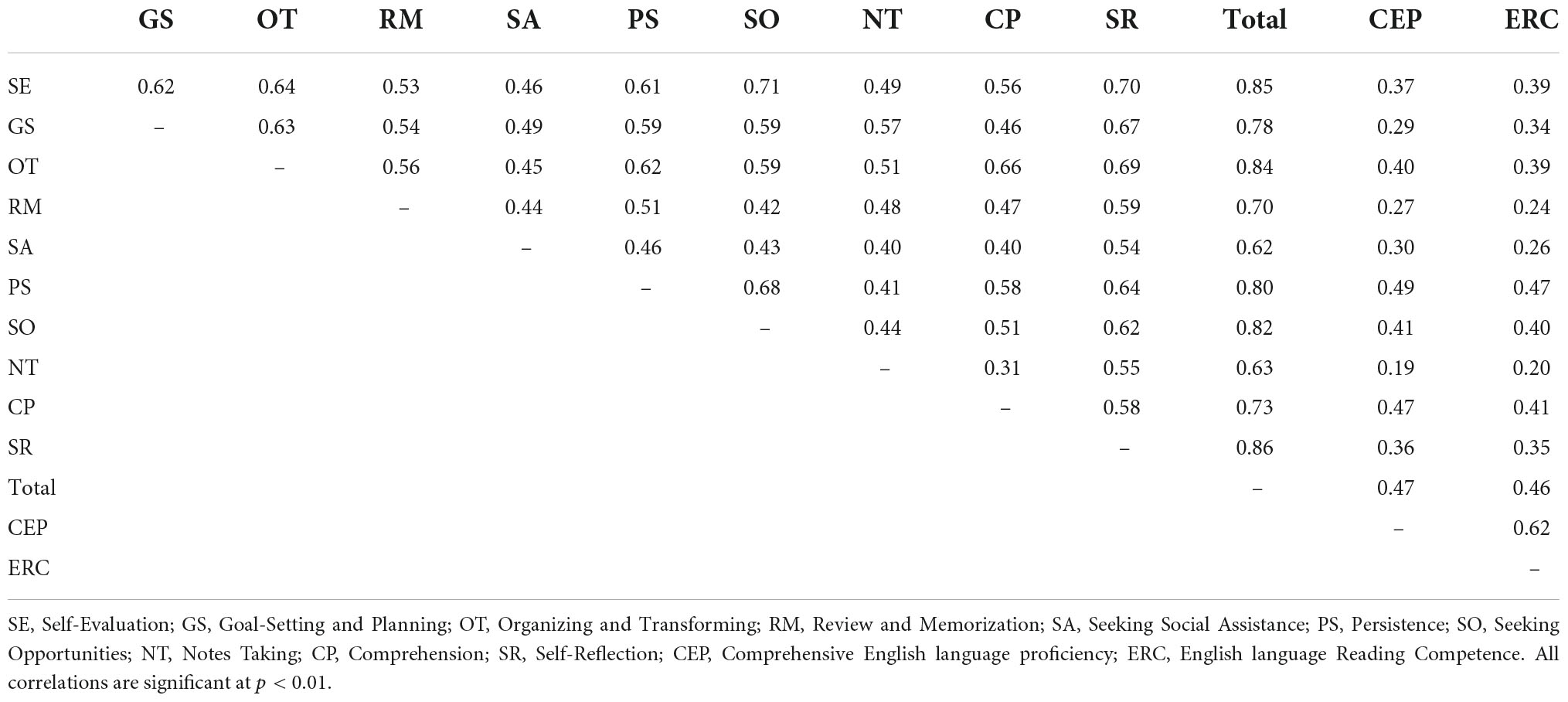

Responses to the survey items were found to be consistent. Internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s value ranged from 0.82 to 0.96 for each subscale. These results support the reliability of responses to ESRLQ. Results from CFA showed that the responses to survey items fall into the expected structure: 10 factors of ESRLQ. The data fit the model well. The goodness-of-fit indices were all satisfactory: CFI > 0.90, SRMR < 0.07, and RMSEA < 0.08 (Table 1). Moreover, the factor loadings of items to each factor of ESRLQ were all statistically significant and were mostly above 0.50 (Figure 1). As a result, findings of this study support the structural aspect of the construct validity of ESRLQ. Statistically significant relationships were also reported between the use of self-regulated learning strategies and student’s comprehensive English language proficiency, r = 0.47, p < 0.001, as well as student’s English language reading competence, r = 0.46, p < 0.001, both with a large effect size (Table 2). Table 2 also reports the correlations between the 10 factors of ESRLQ and their associations with the total SRL use, comprehensive English language proficiency, and English language reading competence, providing evidence for the external aspect of the construct validity of ESRLQ.

Table 2. Correlations between factors of SRL strategy use, comprehensive English proficiency, and English reading competence.

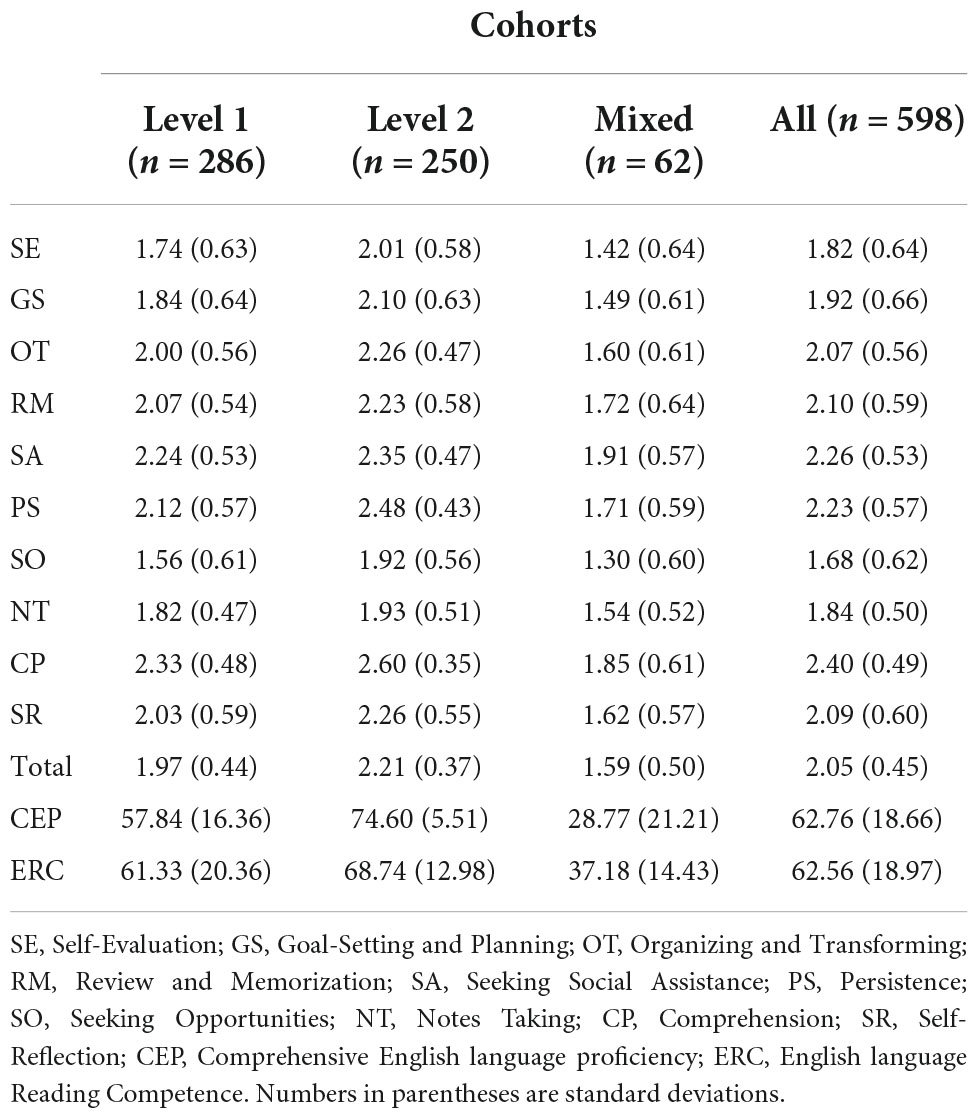

Descriptive statistics of the use of SRL strategies by students in the three cohorts are in Table 3. According to the descriptive statistics, the participants used some SRL strategies as the mean scores for all cohorts ranged between 1 (I seldom use it) and 3 (I often use it). For example, participants reported the use of the following strategies the most: comprehension, seeking social assistance, and persistence. The positive findings are that the use of comprehension and persistence strategies was also strongly associated with the participant’s comprehensive English language proficiency and English language reading competence (r ranged from 0.41 to 0.49). However, participants reported the least use of seeking opportunities to practice the English language although the use of this strategy was strongly associated with the comprehensive English language proficiency (r = 0.40) and English language reading competence (r = 0.41).

Table 3. Means and standard deviations for SRL strategy use, comprehensive English proficiency, and English reading competence.

The linear relationship between the number of years studying English and the English language proficiency score was statistically significant, r = 0.30, p < 0.01. As a result, the assumption to use MANCOVA to compare the SRL strategy use between the students from the three cohorts: Level 1, Level 2, and Mixed Levels was met. Statistically significant differences were found in the linear combination of all three dependent variables, Wilks’ lambda = 0.50, F(6, 1110) = 76.36, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.29 (large effect). Tests of between-subjects effects suggested statistically significant differences in the use of SRL strategies, F(2, 557) = 47.62, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.15 (large effect); comprehensive English language proficiency, F(2, 557) = 258.92, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.48 (large effect); and English language reading competence, F(2, 557) = 64.44, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.19 (large effect). Post hoc multiple comparisons noted that students in Level Two (advanced level) scored more than their peers in Level One (medium level) and that students in Level One scored more than their counterparts in Mixed Level (those who failed in Level One or Level Two) in all three dependent variables, namely, use of SRL strategies, comprehensive English language proficiency, and English language reading competence.

SRL theory has been promoted to examine and foster students’ functioning in academic contexts (Zimmerman, 1990; Schunk and Zimmerman, 2012; Theobald, 2021). The current study integrated the measurement of SRL and the associations between the use of SRL strategies and academic achievements. Three cohorts of participants (advanced-level, medium-level, and mixed-level) were compared for the use of SRL strategies and their performance on English language proficiency and English language reading comprehension tests. This study provided evidence for the structural and external aspect of construct validity of the new instrument.

Future researchers may adopt this instrument to measure Chinese college students’ use of SRL strategies, especially in the region of Macau (and maybe Hong Kong) where student characteristics differ from those in mainland China. Students in Macau and Hong Kong are similar to students in mainland China in that they are all Chinese in ethnicity but different from students in mainland China in that they inherit quite a lot western culture due to the history. Another difference is that English is used much more often in both school settings and social context in Macau and Hong Kong.

Also noteworthy was that in our study, advanced-level students reported significantly more frequent use of self-regulated learning strategies and scored higher than their peers in comprehensive English language proficiency test and English language reading competence test. The positive relationship between the use of SRL strategies and academic achievement reported in this study echoed previous research with learning strategies in the field of teaching/learning English as a foreign/second language (e.g., Bai et al., 2019, Chen et al., 2020).

Empirical evidence emerged in our research also supports the social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and previous research on self-regulation and language learning strategies (i.e., Oxford, 1990, 1996, 2011, 2015; Zimmerman, 2000; Bai and Wang, 2020; Sun et al., 2022). As a result, this study contributes to the theory of self-regulation. Specifically, the structure of the ESRLQ reflected the reciprocity within social cognitive theorizing, involving a triadic process: self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction (Kanfer and Gaelick, 1986; Schunk, 1989; Zimmerman, 1989).

The findings of our study provided evidence for the reliability and validity of student responses to the survey to measure the use of SRL strategies. First, the internal structure of the instrument to measure the use of SRL strategies remained consistent with the previous version from which it was adapted (Wang and Bai, 2017). The external aspects of the construct validity were checked with correlations between the use of SRL strategies and students’ performance on both standardized tests and final exams in the English reading course, with statistically significant relationships to support our expectations. These results are in line with theoretical expectations as well as previous studies in terms of both direction and magnitude (e.g., Broadbent and Poon, 2015; Akamatsu et al., 2019; Sun and Wang, 2020; Bai and Wang, 2020).

Descriptive statistics of the use of SRL strategies suggest that college students in Macau use some SRL strategies but not very often. Strategies under the category of Seeking Opportunities (e.g., read English journals/newspapers/magazines on my initiative and watch English programs on my initiative) were least used. One possible reason is that these strategies are more related to students’ intrinsic motivation rather than teachers’ requirement in English reading courses. While societal norms and cultural values in Macau may have an impact on students’ learning intention and behavior—in absence of a positive sense of wellbeing, students tend to follow teachers’ request and are not often trained to take initiatives for their learning (Cheong, 2022). This implies a need for them to become more self-aware, self-sustaining and self-efficacious. As noted by Broadbent and Poon (2015), learning is more effective if the participant knows how to make and adjust plans to attain academic success. With proper use of SRL strategies, learners are more likely to master the course content and achieve expected learning outcomes (e.g., Chang, 2005; Moseki and Schulze, 2010).

English language instructors may need to adopt SRL strategy development approach to help students gain more SRL strategies. A recent meta-analysis of 22 primary studies has provided a strong and positive link between the use of SRL strategies and language learning outcomes (Sun et al., 2022). In this study, we have advanced the SRL literature by introducing a new instrument to measure college students’ use of SRL strategies. The findings from this study provided more evidence to support the SRL theory in the context of learning EFL.

This study also has practical implications for teachers of ESL/EFL. The findings of this study echoed previous empirical studies and provided evidence to support the strong and positive associations between the use of SRL strategies and English language proficiency. Teachers of English are encouraged to participate in professional development workshops and to learn how to explicitly and systematically incorporate the use of SRL strategies in their classroom instruction so that EFL/ESL learners can benefit more from the English language course. With the help of their teachers, ESL/EFL learners may become adaptive learners with self-regulative process who know how to set goals, manage resources, and monitor their progress, positive learners who may sustain interest and maintain confidence, and proactive learners who know how to select the most appropriate strategies for themselves (Zimmerman, 2002, 2008). This study is significant in that it calls for teachers’ attention to help students develop effective learning strategies while learning ESL/EFL, which will likely improve the efficiency and effectiveness of students’ study at college.

Future researchers are encouraged to have a closer examination of the differences between deep and surface cognitive strategies, which was not examined within the current study. Another limitation of this study lies in the small target population. Although the students in Macau were rarely studied in the past, they are a special Chinese group because they do not have to take Gaokao like other Chinese students do. The JAE test was specially tailored for them. Therefore, test equivalence between Gaokao and JAE is another direction for psychometricians in the future. Finally, readers should be cautious when interpreting the results and generalizing the findings to their own population (e.g., other formerly colonized regions).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Macau University of Science and Technology. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

XD: data collection and manuscript writing. CW: conceptualization, data analysis, and reviewing and editing. JX: reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Support for this research was provided in part by the Research and Development Grant for Chair Professor of the University of Macau (CPG2022-00020-FED). The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the University of Macau, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer ZG declared a shared affiliation with the authors to the handling editor at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akamatsu, D., Nakaya, M., and Koizumi, R. (2019). Effects of metacognitive strategies on the self-regulated learning process: The mediating effects of self-efficacy. Behav. Sci. 9:128. doi: 10.3390/bs9120128

Andrade, M. S., and Evans, N. W. (2012). Principles and practices for response in second language writing: Developing self-regulated learners. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203804605

Bachman, L. F., and Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice: designing and developing useful language tests. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bai, B. (2018). Understanding primary school students’ use of self-regulated writing strategies through think-aloud protocols. System 78, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.07.003

Bai, B., Chao, G., and Wang, C. (2019). The relationship between social support, self-efficacy, and English language learning achievement in Hong Kong. TESOL Q. 53, 208–221. doi: 10.1002/tesq.439

Bai, B., and Wang, J. (2020). The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Lang. Teach. Res. 1–22. doi: 10.1177/1362168820933190 [Epub ahead of print].

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bayat, S., and Tarmizi, R. A. (2010). Assessing cognitive and metacognitive strategies during algebra problem solving among university students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 8, 403–410. doi: 10.1348/000709903322591181

Boekaerts, M., and Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Appl. Psychol. 54, 199–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x

Broadbent, J., and Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 27, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007

Chang, M. (2005). Applying self-regulated learning strategies in a web-based instruction-an investigation of motivation perception. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 18, 217–230. doi: 10.1080/09588220500178939

Chen, X., Wang, C., and Kim, D.-H. (2020). Self-regulated learning strategy profiles among English as a foreign language learners. TESOL Q. 54, 234–251. doi: 10.1002/tesq.540

Cheong, N. (2022). “Enhancing teaching on engineering and science areas, by integrating practice and theory,” in In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on education and training technologies, (New York, NY), 115–119. doi: 10.1145/3535756.3535775

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Copland, F., Garton, S., and Burns, A. (2014). Challenges in teaching english to young learners: Global perspectives and local realities. TESOL Q. 48, 738–762. doi: 10.1002/tesq.148

DiPerna, J. C., Volpe, R., and Elliot, S. N. (2002). A model of academic enablers and elementary reading/language arts achievement. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 31, 298–312. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2002.12086157

Diseth, A. (2011). Self-efficacy, goal orientations and learning strategies as mediators between preceding and subsequent academic achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 21, 191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.003

Education and Youth Affairs Bureau (2001). Research on academic ability of foundation education in Macau. Zhuhai: The University of Macau.

Education and Youth Affairs Bureau (2016). The Requirements of Basic Academic Attainments. Macau Government Headquarters Government of the Macao Special Administrative Region.

Ertmer, P. A., and Newby, T. J. (1996). The expert learner: Strategic, self-regulated, and reflective. Instr. Sci. 24, 1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00156001

Examination Syllabus and Past Examination Papers, (2021). Available online at: https://www.must.edu.mo/en/jae/syllabus

Fan, X., and Sivo, S. A. (2005). Sensitivity of fit indexes to misspecified structural or measurement model components: Rationale of two-index strategy revisited. Struct. Equ. Modeling 12, 343–367. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1203_1

Farley, A., and Yang, H. (2019). Comparison of Chinese Gaokao and Western university undergraduate admission criteria: Australian ATAR as an example. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 39, 470–484. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1684879

Fauzi, A., and Widjajanti, D. B. (2018). Self-regulated learning: The effect on student’s mathematics achievement. J. Phys. 1097, 1–7. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1097/1/012139

Forer, B., and Zumbo, B. D. (2011). “Testing and measurement from a multilevel view: Psychometrics and validation,” in High stakes testing in education— science and practice in K-12 settings (Festschrift to Barbara Plake), eds J. A. Bovaird, K. Geisinger, and C. Buckendahl (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press).

Garner, J. (2010). Conceptualizing the relations between executive functions and self-regulated learning. J. Psychol. 143, 405–426. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.143.4.405-426

Gaskill, P. J., and Hoy, A. W. (2002). “Self-efficacy and self-regulated learning: The dynamic duo in school performance,” in Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education, ed. J. Aronson (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 185–208. doi: 10.1016/B978-012064455-1/50012-9

Gitomer, D. H., and Zisk, R. C. (2015). Knowing what teachers know. Rev. Res. Educ. 39, 1–53. doi: 10.3102/0091732X14557001

Greene, J. A., Dellinger, K. R., Tüysüzoǧlu, B. B., and Costa, L. J. (2013). “A two-tiered approach to analyzing self-regulated learning data to inform the design of hypermedia learning environments,” in International handbook of metacognition and learning technologies, eds R. Azevedo and V. Aleven (Berlin: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5546-3_8

Hlas, A. C. (2018). Grand challenges and great potential in foreign language teaching and learning. Foreign Lang. Ann. 51, 46–54. doi: 10.1111/flan.12317

Ho, E. S. C. (2004). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement of Hong Kong secondary school students. Educ. J. 32, 87–107.

Ho, O. K., Yao, D., and Kunnan, A. J. (2021). An analysis of Macau’s joint admission examination-English. J. Asia TEFL 18, 208–222. doi: 10.18823/asiatefl.2021.18.1.12.208

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Kachru, B. (1985). “Standards, codification, and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle,” in English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures, eds R. Quirk and H. G. Widdowson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 11–30.

Kanfer, E. H., and Gaelick, K. (1986). “Self-management methods,” in Helping people change: A textbook of methods, 3rd Edn, eds E. H. Kanfer and A. P. Goldstein (Pergamon), 283–345.

Kitsantas, A., Steen, S., and Huie, F. (2009). The role of self-regulated strategies and goal orientation in predicting achievement of elementary school children. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2, 65–81.

Kormos, J., and Csizeìr, K. (2014). The interaction of motivation, self-regulatory strategies, and autonomous learning behavior in different learner groups. TESOL Q. 48, 275–299. doi: 10.1002/tesq.129

Kunnan, A. J., and Yao, D. (2020). Teacher ratings of JAE-E test items. Paper circulated at the LASeR group, Department of English. Zhuhai: University of Macau.

Lam, R. (2015). Feedback about self-regulation: Does it remain an “unfinished business” in portfolio assessment of writing? TESOL Q. 49, 402–413. doi: 10.1002/tesq.226

Lee, J. C., Yin, H., and Zhang, Z. (2009). Exploring the influences of the classroom environment and self-regulated learning in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 18, 219–232. doi: 10.3860/taper.v18i2.1324

Li, J., Ye, H., Tang, Y., Zhou, Z., and Hu, X. (2018). What are the effects of self-regulation phases and strategies for Chinese students? A meta-analysis of two decades’ research of the association between self-regulation and academic performance. Front. Psychol. 9:2324. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02434

Liu, Y., and Feng, H. (2011). An empirical study on the relationship between metacognitive strategies and online-learning behavior & test achievements. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2, 183–187. doi: 10.4304/jltr.2.1.183-187

MacCallum, R. C., Roznowski, M., and Necowitz, L. B. (1992). Model modifications in covariance structure analysis: The problem of capitalization on chance. Psychol. Bull. 111, 490–504. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.490

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., and Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Modeling 11, 320–341. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

McKay, S. L. (2002). Teaching english as an international language: Rethinking goals and approaches. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Messick, S. (1989). “Validity,” in Educational measurement, 3rd Edn, ed. R. L. Linn (London: Macmillan), 13–103.

Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am. Psychol. 50, 741–749. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.50.9.741

Moody, A. (2009). “English-medium higher education at the University of Macau,” in Language Issues in Asia’s English-medium Universities, eds C. Davison and N. Bruce (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press).

Moseki, M., and Schulze, S. (2010). Promoting self-regulated learning to improve achievement: A case study in higher education. Afr. Educ. Rev. 7, 356–375. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2010.515422

Norris, J., and Pfeiffer, P. (2003). Exploring the uses and usefulness of ACTFL oral proficiency ratings and standards in college foreign language departments. Foreign Lang. Ann. 36, 572–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2003.tb02147.x

O’Keefe, L., Rafferty, J., Gunder, A., and Vignare, K. (2020). Delivering high-quality instruction online in response to COVID-19: Faculty playbook. online learning consortium conference.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Nashua, NH: Heinle & Heinle.

Oxford, R. L. (1996). Employing a questionnaire to assess the use of language learning strategies. Appl. Lang. Learn. 7, 28–47.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Oxford, R. L. (2015). Expanded perspectives on autonomous learners. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 58–71. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2014.995765

Oxford, R. L. (2016). Teaching and researching language learning strategies: Self-regulation in context. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315719146

Oxford, R. L., and Burry-Stock, J. A. (1995). Assessing the use of language learning strategies world- wide with the ESL/EFL version of the strategy inventory for language learning (SILL). System 23, 1–23. doi: 10.1016/0346-251X(94)00047-A

Panadero, E., Broadbent, J., Boud, D., and Lodge, J. M. (2018). Using formative assessment to in?uence self- and co-regulated learning: The role of evaluative judgement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34, 535–557. doi: 10.1007/s10212-018-0407-8

Pawlak, M., and Oxford, R. L. (2018). Conclusion: The future of research into language learning strategies. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 8, 525–535. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.2.15

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., and Mckeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). Educ. Psychol. Meas. 53, 801–813. doi: 10.1177/0013164493053003024

Pitenoee, M. R., Modaberi, A., and Ardestani, E. M. (2017). The effect of cognitive and metacognitive writing strategies on content of the Iranian intermediate EFL learners’ writing. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 8, 594–600. doi: 10.17507/jltr.0803.19

Rasooli, K. F., Kadivar, P., Sarami, G. R., and Tanha, Z. (2014). The study of relationship between metacognition, achievement goals, study strategies and academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 10, 83–102.

Schneider, W. (2008). The development of metacognitive knowledge in children and adolescents: Major trends and implications for education. Mind Brain Educ. 2, 114–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2008.00041.x

Schraw, G., and Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 19, 460–475. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

Schunk, D. H. (1989). “Social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning,” in Self-Regulated learning and academic achievement. Springer series in cognitive development, eds B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk (Berlin: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3618-4_4

Schunk, D. H., and Zimmerman, B. J. (Eds.) (2012). Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203831076

Seker, M. (2015). The use of self-regulation strategies by foreign language learners and its role in language achievement. Lang. Teach. Res. 20, 600–618. doi: 10.1177/1362168815578550

Su, Y. (2021). A corpus-based diachronic study on the content validity of the cloze test for college entrance examination. Basic Foreign Lang. Educ. 2, 82–91.

Sun, T., Wang, C., and Wang, Y. (2022). The effectiveness of self-regulated strategy development on improving English writing: Evidence from the last decade. Read. Writ. doi: 10.1007/s11145-022-10297-z

Sun, T., and Wang, C. (2020). College students’ writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulated learning strategies in learning English as a foreign language. System 90, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102221

Sutarni, N., Ramdhany, M. A., Hufad, A., and Kurniawan, E. (2021). Self-regulated learning and digital learning environment: Effect on academic achievement during the pandemic. J. Cakrawala Pendidik 40, 374–388. doi: 10.21831/cp.v40i2.40718

Teng, L. S., and Zhang, J. L. (2021). Can self-regulation be transferred to second/foreign language learning and teaching? Current status, controversies, and future directions. Appl. Linguist. 43, 587–595. doi: 10.1093/applin/amab032

Teng, L. S., and Zhang, L. J. (2016). A questionnaire-based validation of multi-dimensional models of self-regulated learning strategies. Modern Lang. J. 100, 674–701. doi: 10.1111/modl.12339

Teng, L. S., Yuan, E., and Sun, P. J. (2019). A mixed-methods approach to investigating motivational regulation strategies and writing proficiency in English as a foreign language contexts. System 88:102182. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.102182

Theobald, M. (2021). Self-regulated learning training programs enhance university students’ academic performance, self-regulated learning strategies, and motivation: A meta-analysis. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 66:101976. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101976

Tigchelaar, M., Bowles, R., Winke, P., and Gass, S. (2017). Assessing the validity of ACTFL Can-Do statements for spoken proficiency: A rasch analysis. Foreign Lang. Ann. 50, 584–600. doi: 10.1111/flan.12286

Troyan, F. (2012). Standards for foreign language learning: Defining the constructs and researching learner outcomes. Foreign Lang. Ann. (S1) 45, S118–S140. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2012.01182.x

Troyan, F. (2016). Learning to mean in Spanish writing: A case study of a genre-based pedagogy for standards-based writing instruction. Foreign Lang. Ann. 49, 317–355. doi: 10.1111/flan.12192

Tsavga, J. (2011). The effect of environment on the academic performance of students in Tarka Local government area of Benue State. Ph.D. thesis. Makurdi: Benue State University.

Tseng, W. T., Chang, Y. J., and Cheng, H. F. (2015). Effects of L2 learning orientations and implementation intentions on self-regulation. Psychol. Rep. 117, 319–339. doi: 10.2466/11.04.PR0.117c15z2

Tseng, W. T., Doñrnyei, Z., and Schmitt, N. (2006). A new approach to assessing strategic learning: The case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Appl. Linguist. 27, 78–102. doi: 10.1093/applin/ami046

Tu, R. (2018). “Primary and secondary mathematics selective examinations,” in The 21st century mathematics education in China, eds Y. Cao and F. K. S. Leung (Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 453–478. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-55781-5_22

Veenman, M. V. J. (2005). “The assessment of metacognitive skills: What can be learned from multi-method designs?,” in Lernstrategien und metakognition: Implicationen für forschung und praxis, eds C. Artelt and B. Moschner (Münster: Waxmann), 77–99.

Vianty, M. (2007). The comparison of students’ use of metacognitive strategies between reading in Bahasa Indonesia and in English. Int. Educ. J. 8, 449–460.

Wang, C., Schwab, G., Fenn, P., and Chang, M. (2013). Self-efficacy and self-regulated learning strategies for English language learners: Comparison between Chinese and German college students. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 3, 173–191.

Wang, C., and Bai, B. (2017). Validating the instruments to measure ESL/EFL learners’ self-efficacy beliefs and self-regulated learning strategies. TESOL Q. 51, 931–947.

Warr, P., and Downing, J. (2000). Learning strategies, learning anxiety and knowledge acquisition. Br. J. Psychol. 91, 311–333. doi: 10.1348/000712600161853

Wang, C., and Sun, T. (2020). Relationship between self-efficacy and language proficiency: A meta-analysis. System 95, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102366

Wei, R., and Su, J. (2012). The statistics of English in China: An analysis of the best available data from government sources. Engl. Today 28, 10–14. doi: 10.1017/S0266078412000235

Winne, P. H. (1995). Inherent details in self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. 30, 173–187. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3004_2

Winne, P. H. (2005). “Researching and promoting self-regulated learning using software technologies,” in Pedagogy–Teaching for learning. Monograph series II: Psychological aspects of education, Vol. 3, eds P. Tomlinson, J. Dockrell, and P. Winne (Leicester: The British Psychological Society), 91–105.

Wolters, C. A. (2004). Advancing achievement goals theory: Using goal structures and goal orientations to predict students’ motivation, cognition, and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 96, 236–250. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.236

Yang, C. (2009). A study of metacognitive strategies employed by English listeners in an EFL setting. Int. Educ. Stud. 2, 134–1139. doi: 10.5539/ies.v2n4p134

Zhang, C. (2021). A corpus-based study on the validity of the reading comprehension test of college entrance exam English. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Beijing: Beijing Foreign Studies University.

Zhang, L., and Seepho, S. (2013). Metacognitive strategy use and academic reading achievement: Insights from a Chinese context. Electron. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 10, 54–69.

Zheng, L. (2016). The effectiveness of self-regulated learning scaffolds on academic performance in computer-based learning environments: A meta-analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 17, 187–202. doi: 10.1007/s12564-016-9426-9

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 329–339. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educ. Psychol. 25, 3–17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.792422

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). “Attaining self-regulation. A social cognitive perspective,” in Handbook of self-regulation, eds M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 13–39. doi: 10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50031-7

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice 41, 64–70. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

Zimmerman, B. J. (2006). “Development and adaptation of expertise: The role of self-regulatory processes and beliefs,” in The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance, eds K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, and R. R. Hoffman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 683–703. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511816796.039

Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 45, 166–183. doi: 10.3102/0002831207312909

Zimmerman, B. J., and Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: A social cognitive perspective. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 22, 73–101. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1997.0919

Zumbo, B. D. (2009). “Validity as contextualized and pragmatic explanation, and its implications for validation practice,” in The concept of validity: Revisions, new directions and applications, ed. R. W. Lissitz (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 65–82.

Appendix: English self-regulated learning questionnaire (ESRLQ).

Part One (Personal information)

Student ID: _______________________ Class code: ___________ Gender: ________ Age: _____

Faculty: ______________ Grade: ________ The number of years you have learned English: _____

Your English test score in the Gaokao (if applicable): ____________

Your English test score in the JAE (if applicable): ____________

Willing to be interviewed: Yes / No

Part Two (SRL strategies)

Please choose answers from the following study methods according to your actual situation. Please notice that this is not a test, so there are no right or wrong answers. Not all the methods listed here are good methods, and everyone has his/her own methods. We intend to know which methods are those you actually use and the frequency of using them. Thanks for your participation!

0 = I never use it. 1 = I seldom use it. 2 = I use it sometimes. 3 = I often use it.

| The Statement of Self-Regulated Learning Strategies | ||||

| 1. Write down the mistakes I often make in the process of studying English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. Make an outline or mind-map before writing English essays. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3. Review English texts I have learned. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4. Take notes in English classes. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. Keep reading when I encounter difficulties in English reading. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6. Consult teachers when I encounter difficulties in the process of studying English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7. Check my English homework before turning them in. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8. Read an English article several times if I don’t understand it at the first time. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9. Make a study plan in the process of studying English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 10. I have definite (clear) goals to study English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 11. Use the answers in English course materials or web pages to check my acquisition of what I have learned. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 12. Rethink its main content after reading an English article. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 13. Summarize the main idea of each paragraph when reading. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 14. Search relevant information online when I have difficulties in studying English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 15. Summarize the theme of an English article when I read it. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 16. Ask classmates/friends when I have questions in my English study. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Practice my pronunciation through listening to an English program several times. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 18. Guess the meaning of new words by considering their contexts. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 19. Classify news words in order to memorize them. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. Write new words many times in order to memorize the spellings. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 21. Use sentence patterns just learned to make new sentences for practice. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 22. Keep records for my feeling about my English learning. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 23. When I come across a new English word in reading, I skip it and move on if it does not hinder my comprehension. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 24. In English reading or conversations, I will predict what is to come according to what I have already known. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 25. When I read an English article, I imagine the scene described in the article in order to memorize what I have read. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 26. Read English journals/newspapers/magazines on my initiative. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 27. Have conversations in English with teachers, classmates or friends (especially foreign friends) to practice my English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 28. I ask myself questions to check whether I understand what I have learned in the English course. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 29. Read new words repeatedly in order to memorize them. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 30. I look for opportunities to talk in English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 31. Watch English programs on my initiative. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 32. Memorize meanings of words by using prefixes and suffixes. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 33. Review my notes of English class before examinations. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 34. I conduct self-assessments on my English communicative ability. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 35. I conduct self-assessments on my English writing ability. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 36. I conduct self-assessments on my English reading ability. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 37. Use my background knowledge to comprehend English articles. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 38. Make sure that the content of each paragraph supports its topic sentence in English writing. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 39. When learning a new English course, I pay close attention to the course syllabus, content and assessment forms. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 40. Seek theme-related materials for my further reading. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 41. Make summaries after reading an English chapter or taking the chapter quiz. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 42. I attempt to think in English when I use it. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 43. Persist in my English study even though I encounter difficulties. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 44. I endeavor to find out how to better my English learning. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 45. I talk to someone else about how I feel about learning English. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 46. I reflect on my learning performance through the evaluation of English assignments or exams. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 47. I use my teacher’s feedback to adjust my English learning in the following phase. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 48. I use my classmates’/friends’ feedback to adjust my English learning in the following phase. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Keywords: self-regulated learning, academic achievement, validity, English as a foreign language, Macau

Citation: Deng X, Wang C and Xu J (2022) Self-regulated learning strategies of Macau English as a foreign language learners: Validity of responses and academic achievements. Front. Psychol. 13:976330. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.976330

Received: 23 June 2022; Accepted: 15 September 2022;

Published: 03 October 2022.

Edited by:

Lin Sophie Teng, Zhejiang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Zhengdong Gan, University of Macau, Macao SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Deng, Wang and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chuang Wang, d2FuZ2NAdW0uZWR1Lm1v

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.