95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Psychol. , 16 September 2022

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.912978

This article is part of the Research Topic Not So WEIRD After All? Relationship Science in Diverse Samples and Contexts View all 5 articles

Alexandra Brozowski

Alexandra Brozowski Hayden Connor-Kuntz

Hayden Connor-Kuntz Sanaye Lewis

Sanaye Lewis Sania Sinha

Sania Sinha Jeewon Oh

Jeewon Oh Rebekka Weidmann

Rebekka Weidmann Jonathan R. Weaver

Jonathan R. Weaver William J. Chopik*

William J. Chopik*Many asexual individuals are in long-term satisfying romantic relationships. However, the contributors to relational commitment among asexual individuals have received little attention. How do investment model characteristics and attachment orientations predict relationship commitment among asexual individuals? Our study looked at a sample of 485 self-identified asexual individuals currently in a romantic relationship (Mage = 25.61, SD = 6.24; MRelationshipLength = 4.42 years, SD = 4.74). Individuals reported on Investment Model characteristics (i.e., their relationship satisfaction, investment, alternatives, and commitment) and their attachment orientations. Satisfaction, investment, and fewer alternatives were associated with greater commitment. Attachment orientations only occasionally moderated the results: for people low in anxiety, satisfaction and investment were more strongly related to commitment compared to people high in anxiety. The current study provided an extension of the Investment Model to describe romantic relationships among asexual individuals.

The Investment Model (Rusbult, 1980a) posits that relationship commitment can be predicted from how happy people are in a relationship (i.e., satisfaction), how much they have invested in a relationship [i.e., investment(s)], and if there are few appealing options available to them (i.e., quality of alternatives). The Investment Model has provided a way of thinking about not only romantic relationships but, for example, also friendships (Rusbult, 1980b), organizational settings (Farrell and Rusbult, 1981), medical settings and health behavior (Putnam et al., 1994; Agnew et al., 2017), academics (Geyer et al., 1987), and athletics (Raedeke, 1997).

One untested application of the Investment Model is whether it can characterize the close relationships formed among asexual individuals (i.e., those with little to no sexual attraction).1 Asexual individuals are a sexual minority, and their members are not well studied, especially in the context of forming and maintaining romantic relationships. Understanding if the Investment Model characterizes their relationships (or not) is important for representing what predicts relational commitment, not only in heteronormative relationships, but also in all relationships that include asexual individuals. Although asexuality provides a unique test of the Investment Model and would increase their representation in the literature, it is reasonable to expect that the tenets of the Investment Model could apply to asexual relationships (Edge et al., 2021). There are likely other characteristics from the relationship literature that might help characterize asexual individuals’ relationships too. For example, an individual’s general approach toward close relationships—their attachment orientation—plays an important role in relationship commitment and functioning (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2007; Cassidy and Shaver, 2008). However, surprisingly rare are formal tests of the role attachment has in modulating the constituent pieces of the Investment Model to predict commitment (Etcheverry et al., 2013; Segal and Fraley, 2016). Will these long-established relationship frameworks apply to relationships involving asexual individuals?

The Investment Model conceptualizes relationship commitment as arising primarily from three factors—relationship satisfaction, quality of alternatives, and investment (Rusbult, 1980a; Rusbult et al., 1998; Le and Agnew, 2003; Tran et al., 2019). Relationship satisfaction refers to the subjective evaluation that a relationship’s positive qualities outweigh its negative qualities. When the outcomes are compared to an individual’s expectations (a comparison level), if the outcomes exceed the expectations, then individuals often report satisfaction with their relationship. Alternatives refer to the perceived desirability of alternatives to a current relationship, including the ability to have needs fulfilled from other partners, friends, family, or alone. Finally, investment refers to the resources, time, and effort put into a relationship and the lost outcomes if the relationship were terminated (Collins et al., 2011). The Investment Model is robust and wide-reaching for characterizing different types of relationships and different, often diverse, populations, including sexual/gender minorities (Barrantes et al., 2017), non-monogamous relationships (Rodrigues et al., 2019), and different romantic and non-romantic arrangements (Ledbetter et al., 2007; Flicker et al., 2021), although occasional adjustments to the measures are made (e.g., alternatives may not be measured among those in non-monogamous relationships).

An individual’s romantic attachment orientation is generally conceptualized as their position on two conceptually distinct dimensions: anxiety and avoidance (Fraley and Waller, 1998). Attachment-related anxiety reflects a preoccupation with the availability of close others (Mikulincer et al., 2002). Individuals with higher anxiety scores exhibit excessive reassurance-seeking and hypervigilance to signs of rejection and abandonment (Shaver et al., 2005). Attachment-related avoidance is characterized by chronic attempts to inhibit attachment-system activation in an effort to minimize distress expressions (Edelstein and Shaver, 2004). Individuals with higher avoidance scores generally dislike intimacy and are less likely to provide emotional support to romantic partners (Brennan et al., 1998; Li and Chan, 2012). Individuals reporting low scores on both dimensions are generally considered secure.

In addition to attachment orientations affecting interpersonal behavior (Simpson et al., 1992), an individual’s attachment orientation also affects their sense of themselves, their partners, and their relationship. For example, attachment orientations affect the attributions people make about their relationships where anxious individuals often assume the worst—ambiguous partner behavior turns into thoughtlessness or outright antagonism (Collins and Read, 1990; Collins et al., 2006). Insecure adults remember relationship interactions as more negative than they were, do not seem to benefit as much from responsive partner behaviors, and generally feel a lack of reciprocation from their partners (for anxious people) or feel smothered by their partners (for avoidant people; Edelstein and Shaver, 2004; Simpson et al., 2010; Simpson and Rholes, 2012; Chopik et al., 2014; Girme et al., 2015; Arriaga et al., 2018; Shaver and Mikulincer, 2021). Given this research then, insecure attachment orientations likely color relationships in a negative light, even when partners are responsive and relationships may be going ostensibly well. Thus, being in a happy relationship might not enhance commitment as much for insecure adults who often have doubts about their relationships. Having quality alternatives might be particularly influential for insecure adults who think their relationships are in trouble or prefer to be in another relationship or alone. Perceiving asymmetries in investment might be particularly damaging for people particularly sensitive to relationship problems. Therefore, attachment orientations might moderate Investment Model associations.

Descriptively, anxiety and avoidance are associated with lower relationship satisfaction and investment (Pistole et al., 1995). In a cross-sectional study, Etcheverry et al. (2013) found a significant direct negative association between attachment anxiety and relationship stability (i.e., anxious participants were more likely to break up). Avoidance, however, did not have this same negative association with relationship persistence but did have a negative association with relationship commitment. In both cases, Investment Model characteristics mediated these associations between attachment and relationship outcomes. In a longitudinal study, Segal and Fraley (2016) found that individuals who viewed their partner as responsive to their needs were more satisfied, invested in their relationships, and viewed alternatives to their relationships as less appealing. Highly anxious and avoidant individuals are less likely to view their partner as responsive, and moderation analyses revealed that links between Investment Model characteristics might be stronger for insecurely attached people. Specifically, for people who were particularly anxious or avoidant, investments and quality of alternatives more strongly influenced commitment. However, the opposite is occasionally seen with secure individuals placing more importance on investments and alternatives when evaluating commitment (Carter et al., 2013).2

There is perhaps an unfair assumption that asexual individuals are less likely to pursue romantic relationships altogether due to their lowered interest in sexual relationships. Although asexual individuals may be less likely to pursue romantic relationships (nationally representative studies examining this question are not available), many asexual individuals indeed choose to be in romantic relationships (Robbins et al., 2016). This basic observation that people who identify as asexual enter romantic relationships has spurred qualitative and theoretical work, including how asexual individuals make sense of romantic orientations and feelings (and the absence of sexual feelings) across life (Rothblum and Brehony, 1993; DeLuzio Chasin, 2011), their engagement in non-monogamy for either their or their partners’ benefits (e.g., so their partner can pursue a sexual relationship; Scherrer, 2010), and how asexual individuals disclose their identity in social situations, including while dating (Robbins et al., 2016).

Asexuality provides a specific test of the Investment Model because relationship initiation, maintenance motivations, and desire are often unique experiences for asexual individuals and their relationships. For instance, many asexual individuals might view being non-partnered as an attractive alternative to feeling a sense of obligation to have sex with a non-asexual partner (Robbins et al., 2016). Further, at least some of the ways that people evaluate the quality of alternatives is with respect to their pursuit of sexual opportunities (Drigotas et al., 1999; Fincham and May, 2017), which might not be a consideration among asexual individuals. Therefore, it is possible that quality of alternatives might be a strong influence on commitment (by having more alternatives to a relationship) or a weak influence (because alternative sexual relationships may not be a factor). Likewise, being happy and having made investments in relationships are associated with higher commitment, and this could also be the case for asexual individuals in relationships. However, sexual activity is also considered a part of increasing interdependence that enhances commitment and investment, suggesting that shared sexual history is at least a partial component of relationship interdependence, satisfaction, and investments (Sprecher, 1998; Vanderdrift et al., 2012). Asexual individuals’ evaluation of commitment departs from non-asexual individuals’ evaluations in terms of (a) what are considered quality alternatives and (b) the uncertainty of how large a contributor sex or sexual needs are for satisfaction and investments.

Worth noting, it is likely that, regardless of the relationship configuration or sexual identities of the romantic partners/couple members, being a responsive partner is associated with good relationship outcomes (Reis et al., 2004). Additionally, being insecurely attached (e.g., being hypervigilant to a partner’s availability or being uncomfortable with emotional intimacy) is probably associated with less relationship satisfaction on average. Extending previous work that integrated adult attachment orientations and the Investment Model (Etcheverry et al., 2013; Segal and Fraley, 2016), we tested whether attachment orientations moderated the contribution of Investment Model characteristics (e.g., relationship satisfaction, investment, and quality of alternatives) in predicting commitment in self-identifying asexual individuals. The strength of association between insecure attachment and is Investment Model characteristics has varied across studies and is tested in variable, inconsistent ways (Carter et al., 2013; Segal and Fraley, 2016). Therefore, we were agnostic about the expected pattern of results.

Participants were 485 individuals who self-identified as on the asexual spectrum and indicated “yes” to the question “Are you currently involved in a romantic relationship?” Participation was voluntary and opens to anyone who self-identified as asexual. No other screening criteria were employed; however, scores on the Asexual Identification Scale (Yule et al., 2015) suggested that nearly all participants surpassed a threshold to be considered “asexual.” This sample was part of a larger study of asexuality (Brozowski et al., 2022, Manuscript in preparation)3; the current report only includes asexual individuals currently in a romantic relationship; the other working paper focuses on lifespan experiences of attraction, acephobia, and well-being.

Most participants (67.0%) were recruited via Facebook groups dedicated to discussions about asexuality. The rest were recruited via asexuality-relevant subreddits on Reddit (20.2%), Tumblr (8.7%), the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) web community forums (2.7%), and other sources (1.3%; e.g., referrals from friends). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 50 (Mage = 25.61, SD = 6.24) and were 67.0% women, 14.8% non-binary, 8.8% men, and 9.4% other gender (i.e., third gender, self-described in another way, or preferred not to say); 14.3% of the sample identified as transgender. The race/ethnicity breakdown of the sample was 79.8% White, 4.9% Biracial, 4.9% other, 3.0% Asian, 2.8% Hispanic/Latino, and 4.6% additional race/ethnicities. In the current sample, the majority (51.6%) reported being in an exclusive dating relationship, 21.0% were married, 10.6% were engaged, 6.3% were in an open relationship, 6.0% were dating but not exclusively, and 4.5% had some other type of romantic relationship (MRelationshipLength = 4.42 years, SD = 4.74). Participants did not receive any compensation for participating.

Regarding romantic orientation, 28.2% identified as heteroromantic (i.e., having romantic attraction toward people of a different sex/gender), 28.0% identified as biromantic (i.e., having romantic attraction toward multiple sexes/genders), 6.7% identified as homoromantic (i.e., having romantic attraction toward people of the same sex/gender), and 6.3% identified as aromantic (i.e., not having romantic attraction toward people of any sex/gender). An additional 30.8% identified as “other” and provided their romantic orientation in an open-ended response [e.g., of those who said “other,” many respondents (50%) simply wrote “asexual” but others said demisexual (12.7%; experiencing sexual attraction after romantic attraction has been established; Carrigan, 2011), panromantic (10.6%; romantic attraction to all sexes/genders; Yule et al., 2017), grey (5.6%; wide-ranging term for those who fall in the “grey area” between sexual and asexual; Carrigan, 2011), and others that reported their orientation with less than 3% frequency for each (21.1%)].4 Among the three largest groups (heteroromantic, biromantic, and other), there were no significant differences in anxiety, avoidance, commitment, satisfaction, and investment (all ps > 0.320). Heteroromantic individuals reported lower quality of alternatives than biromantic (p = 0.003) and other individuals (p = 0.014).

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Michigan State University (MSU) Institutional Review Board (IRB# x17-448e) with informed consent being secured from all participants (documentation requirement waived but collected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki). A sensitivity analysis suggested that we could estimate effects as small as f2 = 0.02 at 80% power and at α = 0.05.

The Investment Model Scale was administered to measure features of relationship satisfaction, investment, quality of alternatives, and commitment (Rusbult et al., 1998). The seven-item commitment subscale (our main dependent variable; α = 0.85) includes items such as “I want our relationship to last forever.” The five-item relationship satisfaction subscale (α = 0.92) includes such items as, “My relationship is close to ideal.” The five-item investment subscale (α = 0.79) includes items such as “I have put a great deal into our relationship that I would lose if the relationship were to end.” The five-item quality of alternatives subscale (α = 0.84) includes items such as “My alternatives to our relationship are close to ideal (dating another, spending time with friends or on my own, etc.).” Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each statement on a scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (agree completely).

We assessed adult attachment orientations with the Experiences in Close Relationships-Relationship Structures questionnaire, modified to be about close relationships/others generally (Fraley et al., 2011). The three-item anxiety subscale (α = 0.90) reflects an individual’s fear of abandonment and a hyperactivation of the attachment system. The six-item avoidance subscale (α = 0.86) reflects an individual’s discomfort with emotional and physical intimacy and chronic efforts to deactivate the attachment system. Participants rated the extent to which each statement described on a scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly).

As seen in Table 1, the Investment Model characteristics were all significantly correlated with each other. Highly anxious individuals reported higher levels of commitment, higher levels of investment, and a lower quality of alternatives; but anxiety was not associated with relationship satisfaction. Highly avoidant individuals reported lower levels of relationship satisfaction, quality of alternatives, and commitment.

We ran linear regressions predicting commitment from relationship satisfaction, investment, and quality of alternatives. We also controlled for age, gender (separately dummy coded each group for women [1], non-binary people [1], and those who listed another gender [1], with men serving as the reference group [0]), and transgender identity (dummy coded for transgender people [1], with non-transgender people serving as the reference group [0]). In the next step of the model, we entered attachment anxiety and avoidance and their two-way interactions with relationship satisfaction, investment, and quality of alternatives.5

As seen in the left panel of Table 2, commitment was associated with higher relationship satisfaction and investment and a lower quality of alternatives. The standardized regression coefficients for predicting commitment were highly comparable to what has been reported in previous meta-analyses; indeed, similar magnitudes of associations between investment model variables are often seen in the literature (Le and Agnew, 2003; Tran et al., 2019).

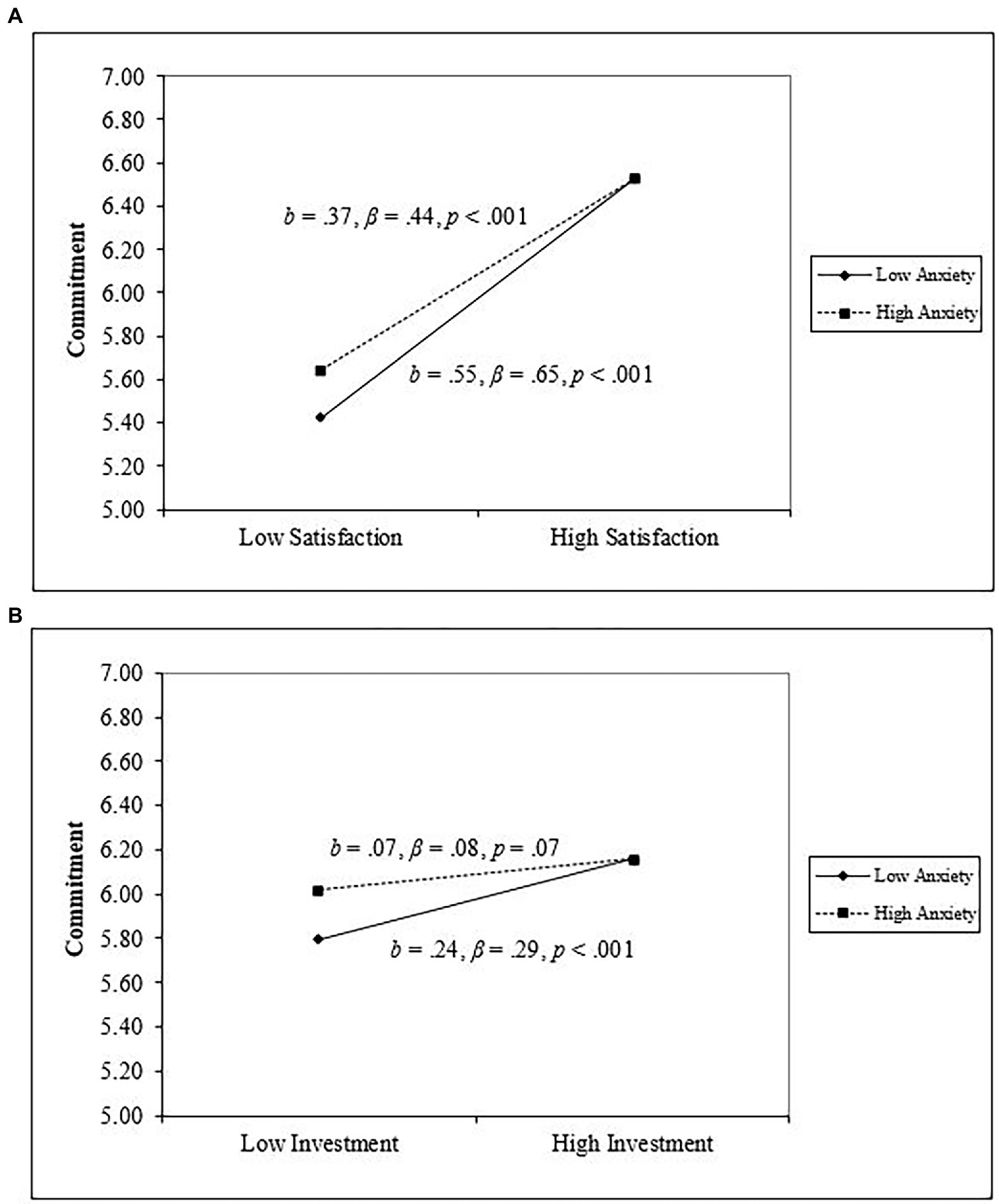

As seen in the right panel of Table 2, anxiety was associated with higher commitment, and avoidance was not a significant predictor of commitment. For the most part, anxiety and avoidance did not moderate the associations between Investment Model characteristics and commitment, with two exceptions: significant anxiety × relationship satisfaction and anxiety × investment interactions predicting commitment. As seen in Figure 1A, among individuals high in attachment anxiety, relationship satisfaction was positively associated with commitment (β = 0.44, p < 0.001). Among individuals low in attachment anxiety, relationship satisfaction was also positively associated with commitment, but to a larger degree (β = 0.65, p < 0.001). A similar pattern can be found in Figure 1B for the anxiety × investment interaction. Among individuals high in attachment anxiety, investment was positively associated with commitment (β = 0.08, p = 0.07). Among individuals low in attachment anxiety, investment was also positively associated with commitment, but to a larger degree (β = 0.29, p < 0.001). Altogether, relationship satisfaction and investment seem to be a stronger predictor of commitment among asexual individuals low in attachment anxiety.

Figure 1. Interactions between attachment anxiety and investment model characteristics [Relationship Satisfaction (A), Investment (B)] predicting commitment.

Relationship satisfaction, quality of alternatives to a relationship, and relationship investment are thought to be antecedents of commitment. In two meta-analyses, relationship satisfaction had the largest associations (β = 0.47–0.51) with commitment, and investment and quality of alternatives had relatively comparable associations with commitment (βs = |0.19|−|0.28|). Our study was consistent with this previous work (Le and Agnew, 2003; Tran et al., 2019). Thus, we generally view the Investment Model as an appropriate theoretical framework to characterize asexual individuals’ relationships.

When examining the role of attachment orientations in the context of diverse relationships (Moors et al., 2015), a few general patterns are often comparable in heteronormative samples. Namely, attachment orientations are often correlated with relationship functioning in some predictable ways. Avoidant individuals reported lower commitment, relationship satisfaction, and investment. Inconsistent with previous findings, anxiety was related to higher relationship satisfaction (instead of a null association) and more commitment (instead of less). Insecure attachment was associated with perceiving alternatives as lower quality instead of higher quality for highly avoidant people (DeWall et al., 2011) or instead of null associations for highly anxious people (Etcheverry et al., 2013). Asexual individuals low in anxiety had stronger associations between Investment Model characteristics and commitment compared to asexual individuals high in anxiety. It could be the case that highly anxious people might not be benefitting from the commitment-enhancing functions of higher levels of relationship satisfaction and investments; perhaps this is because of their rumination on the worst parts of their relationship and inferring the most unflattering motives of their partners (Collins and Read, 1990; Pietromonaco and Barrett, 2000; Simpson et al., 2010; Arriaga et al., 2018). Of course, closer examination of the simple slopes revealed that both individuals high and low in anxiety benefit from being in a satisfying and invested relationship, but people low in anxiety benefit more. Worth noting, there could be several reasons for these differences—although it might be attributable to particulars about living life as an asexual person, variation can also arise from variability in sampling distributions, measurement considerations, a combination of these reasons, or other reasons entirely.

In the current study, we relied primarily on cross-sectional data from individuals and had little information about their relational behavior with their partners. Are they dating other asexual people or non-asexual people? If they are in relationships with non-asexual people, do asexual individuals engage in some forms of physical affection or sexual activity but not others? Examining relationship dynamics among asexual individuals and how they might (not) negotiate sexual activity with non-asexual partners is a promising future direction of its own. Future research may benefit from looking at their partners’ sexual and romantic identities, their perspective on the relationship, and their relationship satisfaction. Given this context, it is possible that views toward sexual intimacy and the relationship would be discordant, particularly if the people in the relationship have different identities. Future research can more formally collect dyadic data to examine the perspectives of both members of the relationship. To improve on the current study’s cross-sectional design future research can utilize experimental (Tan and Agnew, 2016; Baker et al., 2017) and longitudinal (Impett et al., 2001; Brooks et al., 2018) tests of the Investment Model by testing these processes in the context of asexual individuals navigating relationship dynamics.

Finally, recruiting nationally representative data on asexual and non-asexual populations is important for drawing conclusions about the applicability of theoretical models of close relationships among different substrata of the population. In the current study, we focused on variation within a group of individuals on the asexual spectrum. Another approach would have been to recruit a comparable sample of non-asexual individuals and draw more formal comparisons rather than informal comparisons with published meta-analyses (e.g., Edge et al., 2021). Future research can be more deliberate in sampling and recruitment approaches to examine the generalizability of relationship phenomena. More generally, the current study can provide some reflection on whether our relational phenomena and measures are inclusive enough to capture the full diversity of relationship phenomena (e.g., removing the alternatives scale for non-monogamous couples; Rodrigues et al., 2019). In many cases, sex is often “baked into” many relationship measures and is often considered an antecedent of individual and relationship well-being (Muise et al., 2015). Can a relationship theory and phenomena truly characterize diverse relationships if their representative measures need to be revised before being administered to diverse populations? A definitive answer to this question is beyond the scope of the current paper. Future research should more critically examine and develop the conditions under which dominant theories of relationship phenomena can come to characterize diverse populations.

The current study was the first to examine Investment Model characteristics and attachment orientation moderators among partnered asexual individuals. All Investment Model characteristics were significantly correlated with each other and predicted commitment among asexual individuals. Attachment-related differences were variable—a consideration when examining mechanisms linking individual differences to relational outcomes among asexual individuals. Overall, this study furthers our knowledge and understanding of marginalized and underrepresented community members and potentially normalizes asexual individuals’ individual and relational experiences.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Michigan State University Institutional Review Board (MSU IRB# x17-448e). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AB, JW, and WC conceived of the study. WC, JO, and RW analyzed the data and created the tables and figures. AB, HC-K, SL, and SS drafted the initial manuscript. All authors provided critical edits. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.912978/full#supplementary-material

1. ^The asexual spectrum is a heterogeneous community with myriad identity labels that make up the spectrum (Carrigan, 2011). This study allowed for representation of this diverse community through participants self-reporting their identity labels. For the sake of simplicity, "asexual" is generally used as a blanket term for this community throughout this report and is not meant to diminish the entire spectrum or sub-labels within the spectrum.

2. ^In choosing our analytic approach, we elected to run a relatively straightforward test of moderation which was surprisingly rare to find in the literature and departed a bit from the main studies we cited examining attachment and investment model characteristics. Specifically, Etcheverry et al. (2013) ran a cross-sectional mediation that examined attachment orientations as antecedents of investment. Segal and Fraley (2016) ran a multi-level SEM that examined attachment modeled as antecedents of investment. Perhaps most closely related to our study was Carter et al. (2013) who experimentally manipulated investment model characteristics to eventually run multi-group invariance tests based on a dichotomized measure of attachment. Based on the descriptive goals of the current study, we elected to test moderation by using the continuous measure of attachment in the context of linear regressions.

3. ^Brozowski, A., Weidmann, R., Oh, J., Weaver, J. R., and Chopik, W. J. (2022). Demographic and experiential characteristics of asexual individuals and associations with well-being. Manuscript in preparation.

4. ^Participants were not provided with definitions of romantic orientations and self-reported their romantic identities. Therefore, these romantic identity definitions may not fully represent each participant’s romantic identity conceptualization. In fact, within the community is a wide variety of ways to characterize thoughts, feelings, and behavior on the asexuality spectrum. For example, there is not a singular definition for the term panromantic (Belous and Bauman, 2017), and panromantic people may conceptualize and build their identities in a multitude of ways (Lapointe, 2017). Further, we did not conduct a thorough assessment of identities across the asexual spectrum—rather, people volunteered these labels when asked about their romantic orientation. Although the minority of participants wrote a more specific identity (e.g., demisexual), we are not sure about the distribution of asexual identities within our sample. Because of this, we encourage caution in generalizing the results of the current study to the entire asexual community.

5. ^For the most part, our study replicated the findings from Etcheverry et al. (2013) with either comparable or smaller effect sizes (see supplement). However, satisfaction did not mediate the link between anxiety and commitment; also, quality of alternatives mediated attachment-commitment links but in the opposite direction, such that attachment insecurity was associated with perceiving fewer alternatives, which in turn was associated with higher commitment.

Agnew, C. R., Harvey, S. M., VanderDrift, L. E., and Warren, J. (2017). Relational underpinnings of condom use: findings from the project on partner dynamics. Health Psychol. 36, 713–720. doi: 10.1037/hea0000488

Arriaga, X. B., Kumashiro, M., Simpson, J. A., and Overall, N. C. (2018). Revising working models across time: relationship situations that enhance attachment security. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 22, 71–96. doi: 10.1177/1088868317705257

Baker, L. R., McNulty, J. K., and VanderDrift, L. E. (2017). Expectations for future relationship satisfaction: unique sources and critical implications for commitment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 146, 700–721. doi: 10.1037/xge0000299

Barrantes, R. J., Eaton, A. A., Veldhuis, C. B., and Hughes, T. L. (2017). The role of minority stressors in lesbian relationship commitment and persistence over time. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 4, 205–217. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000221

Belous, C. K., and Bauman, M. L. (2017). What’s in a name? Exploring pansexuality online. J. Bisex. 17, 58–72. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2016.1224212

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., and Shaver, P. R. (1998). “Self-report measurement of adult attachment: an integrative overview,” in Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. eds. J. A. Simpson and W. S. Rholes (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 46–76.

Brooks, J. E., Ogolsky, B. G., and Monk, J. K. (2018). Commitment in interracial relationships: dyadic and longitudinal tests of the investment model. J. Fam. Issues 39, 2685–2708. doi: 10.1177/0192513X18758343

Carrigan, M. (2011). There’s more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community. Sexualities 14, 462–478. doi: 10.1177/1363460711406462

Carter, A. M., Fabrigar, L. R., MacDonald, T. K., and Monner, L. J. (2013). Investigating the interface of the investment model and adult attachment theory. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 661–672. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1984

Cassidy, J., and Shaver, P. R. (2008). Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., van Anders, S. M., Wardecker, B. M., Shipman, E. L., and Samples-Steele, C. R. (2014). Too close for comfort? Adult attachment and cuddling in romantic and parent-child relationships. Personal. Individ. Differ. 69, 212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.035

Collins, N. L., Ford, M. B., and Feeney, B. C. (2011). “An attachment-theory perspective on social support in close relationships,” in Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic intervention. eds. L. N. Horowitz and S. Strack (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 46–76.

Collins, N. L., Ford, M. B., Guichard, A. C., and Allard, L. M. (2006). Working models of attachment and attribution processes in intimate relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 201–219. doi: 10.1177/0146167205280907

Collins, N. L., and Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 644–663. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644

DeLuzio Chasin, C. J. (2011). Theoretical issues in the study of asexuality. Arch. Sex. Behav. 40, 713–723. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9757-x

DeWall, C. N., Lambert, N. M., Slotter, E. B., Pond, R. S. Jr., Deckman, T., Finkel, E. J., et al. (2011). So far away from one's partner, yet so close to romantic alternatives: avoidant attachment, interest in alternatives, and infidelity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 1302–1316. doi: 10.1037/a0025497

Drigotas, S. M., Safstrom, C. A., and Gentilia, T. (1999). An investment model prediction of dating infidelity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 509–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.3.509

Edelstein, R. S., and Shaver, P. R. (2004). “Avoidant attachment: exploration of an oxymoron,” in Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy. eds. D. J. Mashek and A. P. Aron (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 397–412.

Edge, J. M., Vonk, J., and Welling, L. L. M. (2021). Asexuality and relationship investment: visible differences in relationship investment for an invisible minority. Psychol. Sexuality, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2021.2013303

Etcheverry, P. E., Le, B., Wu, T.-F., and Wei, M. (2013). Attachment and the investment model: predictors of relationship commitment, maintenance, and persistence. Pers. Relat. 20, 546–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01423.x

Farrell, D., and Rusbult, C. E. (1981). Exchange variables as predictors of job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnover: the impact of rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 28, 78–95. doi: 10.1016/0030-5073(81)90016-7

Fincham, F. D., and May, R. W. (2017). Infidelity in romantic relationships. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 13, 70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.008

Flicker, S. M., Sancier-Barbosa, F., Moors, A. C., and Browne, L. (2021). A closer look at relationship structures: relationship satisfaction and attachment among people who practice hierarchical and non-hierarchical polyamory. Arch. Sex. Behav. 50, 1401–1417. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01875-9

Fraley, R. C., Heffernan, M. E., Vicary, A. M., and Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). The experiences in close relationships—relationship structures questionnaire: a method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychol. Assess. 23, 615–625. doi: 10.1037/a0022898

Fraley, R. C., and Waller, N. G. (1998). “Adult attachment patterns: a test of the typological model,” in Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. eds. J. A. Simpson and W. S. Rholes (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 77–114.

Geyer, P. D., Brannon, Y. S., and Shearon, R. W. (1987). The prediction of students' satisfaction with community college vocational training. Aust. J. Psychol. 121, 591–597. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1987.9712688

Girme, Y. U., Overall, N. C., Simpson, J. A., and Fletcher, G. J. O. (2015). “All or nothing”: attachment avoidance and the curvilinear effects of partner support. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 450–475. doi: 10.1037/a0038866

Impett, E. A., Beals, K. P., and Peplau, L. A. (2001). Testing the investment model of relationship commitment and stability in a longitudinal study of married couples. Curr. Psychol. 20, 312–326. doi: 10.1007/s12144-001-1014-3

Lapointe, A. A. (2017). “It’s not pans, it’s people”: student and teacher perspectives on bisexuality and pansexuality. J. Bisex. 17, 88–107. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2016.1196157

Le, B., and Agnew, C. R. (2003). Commitment and its theorized determinants: a meta-analysis of the investment model. Pers. Relat. 10, 37–57. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00035

Ledbetter, A. M., Griffin, E., and Sparks, G. G. (2007). Forecasting “friends forever”: a longitudinal investigation of sustained closeness between best friends. Pers. Relat. 14, 343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00158.x

Li, T., and Chan, D. K. S. (2012). How anxious and avoidant attachment affect romantic relationship quality differently: a meta-analytic review. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 42, 406–419. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1842

Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., and Shaver, P. R. (2002). Activation of the attachment system in adulthood: threat-related primes increase the accessibility of mental representations of attachment figures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 881–895. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.881

Mikulincer, M., and Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Moors, A. C., Conley, T. D., Edelstein, R. S., and Chopik, W. J. (2015). Attached to monogamy? Avoidance predicts willingness to engage (but not actual engagement) in consensual non-monogamy. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 32, 222–240. doi: 10.1177/0265407514529065

Muise, A., Schimmack, U., and Impett, E. A. (2015). Sexual frequency predicts greater well-being, but more is not always better. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 7, 295–302. doi: 10.1177/1948550615616462

Pietromonaco, P. R., and Barrett, L. F. (2000). The internal working models concept: what do we really know about the self in relation to others? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 4, 155–175. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.155

Pistole, M. C., Clark, E. M., and Tubbs, A. L. (1995). Love relationships: attachment style and the investment model. J. Ment. Health Couns. 17, 199–209.

Putnam, D. E., Finney, J. W., Barkley, P. L., and Bonner, M. J. (1994). Enhancing commitment improves adherence to a medical regimen. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 62, 191–194. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.1.191

Raedeke, T. D. (1997). Is athlete burnout more than just stress? A sport commitment perspective. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 19, 396–417. doi: 10.1123/jsep.19.4.396

Reis, H. T., Clark, M. S., and Holmes, J. G. (2004). “Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing construct in the study of intimacy and closeness,” in Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy. eds. D. J. Mashek and A. P. Aron (New York, NY: Routledge), 201–225.

Robbins, N. K., Low, K. G., and Query, A. N. (2016). A qualitative exploration of the “coming out” process for asexual individuals. Arch. Sex. Behav. 45, 751–760. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0561-x

Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., Pereira, M., De Visser, R., and Cabaceira, I. (2019). Sociosexual attitudes and quality of life in (non) monogamous relationships: the role of attraction and constraining forces among users of the second love web site. Arch. Sex. Behav. 48, 1795–1809. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1272-x

Rothblum, E. D., and Brehony, K. A. (1993). Boston Marriages: Romantic But Asexual Relationships Among Contemporary Lesbians. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Rusbult, C. E. (1980a). Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: a test of the investment model. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 16, 172–186. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4

Rusbult, C. E. (1980b). Satisfaction and commitment in friendships. Represent. Res. Soc. Psychol. 11, 96–105.

Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., and Agnew, C. R. (1998). The investment model scale: measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Pers. Relat. 5, 357–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x

Scherrer, K. S. (2010). “Asexual relationships: what does asexuality have to do with polyamory?” in Understanding Non-Monogamies. eds. M. Barker and D. Langdridge (New York, NY: Routledge), 166–171.

Segal, N., and Fraley, R. C. (2016). Broadening the investment model: an intensive longitudinal study on attachment and perceived partner responsiveness in commitment dynamics. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 33, 581–599. doi: 10.1177/0265407515584493

Shaver, P. R., and Mikulincer, M. (2021). “Defining attachment relationships and attachment security from a personality-social perspective on adult attachment,” in Attachment: The Fundamental Questions. eds. R. A. Thompson, J. A. Simpson, and L. J. Berlin (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 39–45.

Shaver, P. R., Schachner, D. A., and Mikulincer, M. (2005). Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 343–359. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271709

Simpson, J. A., and Rholes, W. S. (2012). “Adult attachment orientations, stress, and romantic relationships,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. eds. P. Devine and A. Plant. Vol. 45 (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 279–328.

Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., and Nelligan, J. S. (1992). Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: the role of attachment styles. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62, 434–446. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.62.3.434

Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., and Winterheld, H. A. (2010). Attachment working models twist memories of relationship events. Psychol. Sci. 21, 252–259. doi: 10.1177/0956797609357175

Sprecher, S. (1998). Social exchange theories and sexuality. J. Sex Res. 35, 32–43. doi: 10.1080/00224499809551915

Tan, K., and Agnew, C. R. (2016). Ease of retrieval effects on relationship commitment: the role of future plans. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 42, 161–171. doi: 10.1177/0146167215617201

Tran, P., Judge, M., and Kashima, Y. (2019). Commitment in relationships: an updated meta-analysis of the investment model. Pers. Relat. 26, 158–180. doi: 10.1111/pere.12268

Vanderdrift, L. E., Lehmiller, J. J., and Kelly, J. R. (2012). Commitment in friends with benefits relationships: implications for relational and safe-sex outcomes. Pers. Relat. 19, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01324.x

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., and Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). A validated measure of no sexual attraction: The Asexuality Identification Scale. Psychol. Assess. 27, 148–160. doi: 10.1037/a0038196

Keywords: asexuality, investment model, attachment orientation, asexual spectrum, romantic relationships

Citation: Brozowski A, Connor-Kuntz H, Lewis S, Sinha S, Oh J, Weidmann R, Weaver JR and Chopik WJ (2022) A test of the investment model among asexual individuals: The moderating role of attachment orientation. Front. Psychol. 13:912978. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.912978

Received: 05 April 2022; Accepted: 22 August 2022;

Published: 16 September 2022.

Edited by:

Kathleen Carswell, Durham University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Christopher R. Agnew, Purdue University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Brozowski, Connor-Kuntz, Lewis, Sinha, Oh, Weidmann, Weaver and Chopik. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William J. Chopik, Y2hvcGlrd2lAbXN1LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.