94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 04 July 2022

Sec. Movement Science

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.907336

This article is part of the Research TopicPerformance Optimization in Football: Advances in Theories and PracticesView all 11 articles

This study explored factors that influence actual playing time by comparing the Chinese Super League (CSL) and English Premier League (EPL). Eighteen factors were classified into anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic factors. Fifty CSL matches (season 2019) and 50 EPL matches (season 2019–2020) were analyzed. An independent sample t-test with effect size (Cohen’s d) at a 95% confidence interval was used to evaluate differences in the influencing factors between the CSL and EPL. Two multiple linear regression models regarding the CSL and EPL were conducted to compare the influencing factors’ impact on actual playing time. The results showed that the average actual playing time (p < 0.05, 0.6 < ES = 0.610 < 1.2) and average game density (p < 0.05, 0.2 < ES = 0.513 < 0.6) in the EPL were significantly higher than in the CSL. The average time per game for general fouls (p < 0.05, 1.2 < ES = 1.245 < 2.0) and minor injuries (p < 0.05, 0.2 < ES = 0.272 < 0.6) in the CSL was significantly higher than in the EPL. The average time allocated to off-field interferences in the CSL was significantly higher than in the EPL, while the average time allocated to throw-ins (out-of-bounds) in the CSL was significantly lower than in the EPL (p < 0.05, 0.2 < ES = 0.556 < 0.6). The study showed that actual playing time in CSL games was more affected by anthropogenic factors than in the case of EPL games, while both leagues were equally affected by non-anthropogenic factors. This study provides a reference for coaches to design effective training and formulate game strategies for elite soccer leagues.

In a soccer game, actual playing time is defined as the duration of play after subtracting the time taken up by stoppages, substitutions, goals, injuries, and other incidences (Castellano et al., 2011), which are added on as extra time at the end of the game. The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) calculates the actual playing time to assess the continuity, quality, and watchability of a game (Peng, 2017) as it is an important indicator of the level of a league. The actual playing time of a soccer game can be considerably less than 90 min due to stoppages caused by free kicks, corner kicks, substitutions, goals, player injuries, and other interferences (Cook and Goff, 2006; Lago-Peñas et al., 2012). The level of the players, the match status of the game, the level of play, and the team’s playing style (Boyko et al., 2007; Dong, 2012; Greve et al., 2019) can also have an impact. All these factors can increase the total playing time. The use of a video assistant referee (VAR) in recent years has led to more stoppages, resulting in an increase in total playing time (Han et al., 2020).

An elite soccer games can be stopped approximately 108 times and account for up to 38% of the total game (Siegle and Lames, 2012a). Stoppages during a game have a significant impact on a player’s performance. Previous studies have found that stoppages cause extended extra time and reduce players’ running performance (Linke et al., 2018); moreover, running distance in the second half of a game may decrease because of too many stoppages rather than a decrease in physical capacity (Carling and Dupont, 2011; Rey et al., 2020). Some soccer teams will deliberately create opportunities for stoppages (place kicks, out-of-bound goals, etc.) when they are ahead or stall at dead balls (Siegle and Lames, 2012a,b; Augste and Cordes, 2016) to disrupt the continuity of the other team’s attack, especially in the final stages of a game (Carling and Dupont, 2011).

Stoppages are directly associated with some of the indicators of soccer games and play an important guiding role in the time, frequency, density, and intervals of team training. Chinese soccer is gaining more public attention and social influence, and the Chinese Super League’s (CSL) games have increased in both pace and quality (China Football Federation, 2019). For example, the CSL’s average actual playing time in the 2008 season was 51 min and 25 s (Dong, 2012), and it rose to 54 min in the 2014–2017 seasons (Zhao, 2019). Nevertheless, the CSL’s actual playing time is still shorter than the world’s elite leagues. In 2006, the average actual playing time of the 18th FIFA World Cup was 60 min and 36 s, with an average match density of 62%. The 13th European Football Championship in 2008 had an average actual playing time of 62 min and 23 s. Since the CSL players have a lower load and match intensity than the five major European soccer leagues (Li, 2007), they cannot perform high-quality technical and tactical movements in high-intensity matches to produce a satisfactory performance.

The CSL is growing rapidly and the amount of research on the CSL is increasing (Jiang, 2013; He, 2016; Liu and Hopkins, 2017; Li, 2019), yet few studies have focused on the factors that impact actual playing time. The English Premier league (EPL)—a well-established league—is known as one of the best soccer leagues in the world; the CSL league—a developing league—has modeled itself on the EPL. Thus, this study aims to understand the nature of soccer from the two different contexts and compares the important factors that influence the actual playing time in the CSL and EPL, as the two typical leagues in the East and West. The results of this study may assist coaches in understanding the causes for stoppages in soccer games. Moreover, this study may offer a realistic guide for the coaches of professional clubs to design training programs that improve players’ ability under pressure and help referees to control different situations during a game.

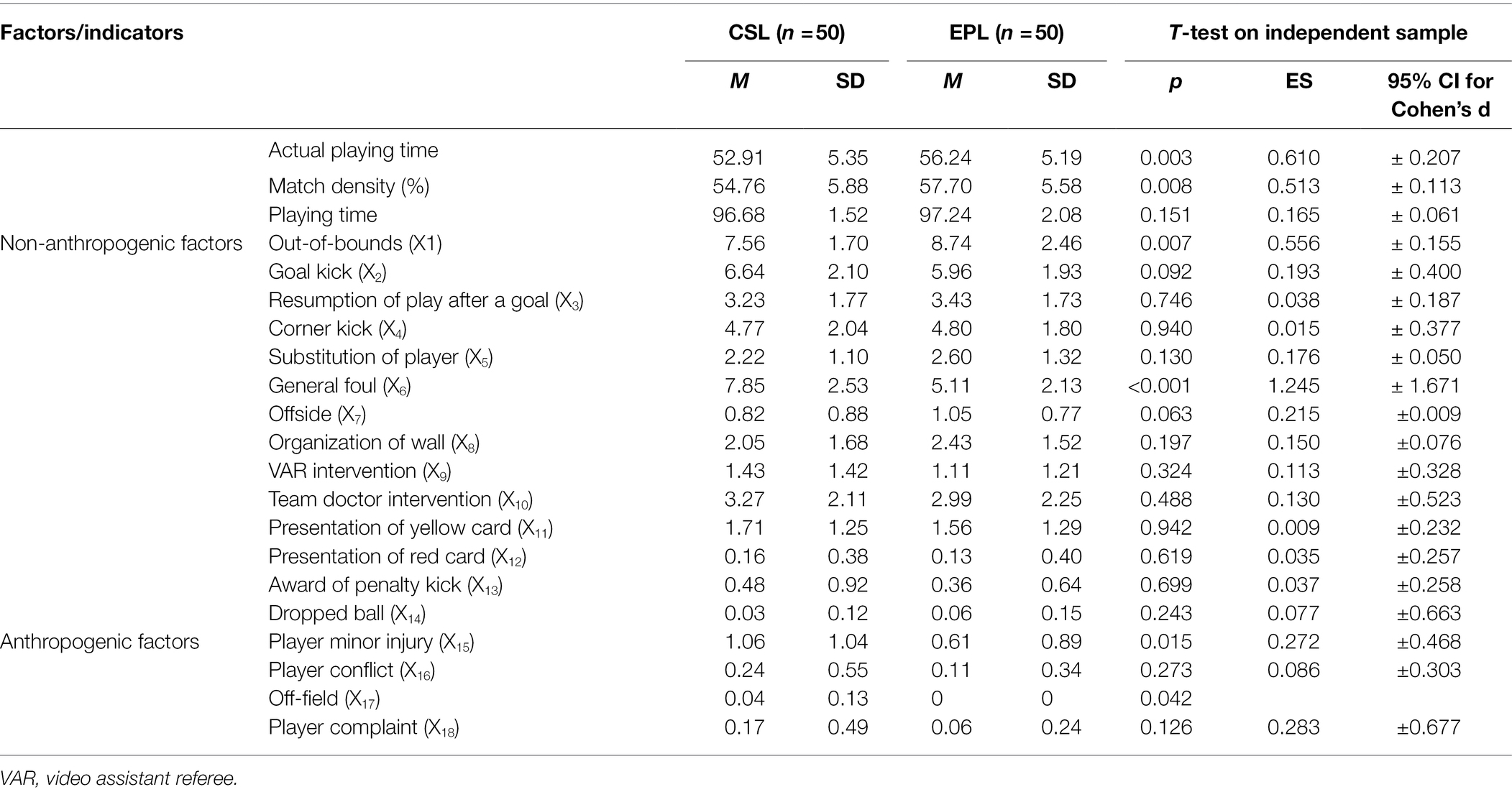

This study randomly selected 50 matches in the CSL during the 2019 season and 50 matches in the EPL during the 2019–2020 season, prior to the 30th round. Matches after the 30th round were excluded because some rules were changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The matches were recorded onto a hard drive and included all 16 teams in the CSL and all 20 teams in the EPL. Three matches from each league were selected for pre-testing, and expert interviews were conducted to refine the statistical concepts and measurements. Following previous studies (Li, 2007; Yang et al., 2018; Gai et al., 2019; Zhao, 2019; Han et al., 2020), 18 stoppage-related variables were determined, which were then categorized as either non-anthropogenic or anthropogenic factors (Table 1). Non-anthropogenic stoppage factors were defined as stoppages that resulted from the “FIFA Laws of the Game” and the nature of soccer games, whereas anthropogenic stoppage factors were defined as stoppages that resulted from the behavior of players and other people at the venue.

Afterwards, an experienced specialist examined the games and collected the data. The specialist recorded the time taken up by stoppages in the effective time of each game and exported the results onto Excel spreadsheets.

To test the reliability of the data, another experienced observer examined ten randomly selected games (10% of the sample: 5 CSL and 5 EPL games; Hernández-Moreno et al., 2011). Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) values ranged from 0.968 to 1.0 (Table 2), which exceeded 0.9 and thus proved excellent reliability (Koo and Li, 2016).

A descriptive analysis of each variable was conducted for the two leagues. Data normality was calculated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and was found to be normally distributed. Subsequently, an independent samples t-test (p < 0.05) was conducted to compare and analyze actual playing time, game density, duration of each game, and then tabulated 18 stoppage variables in the two leagues. The results were recorded as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). The effect size (ES, Cohen’s d) at 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was then used to measure the range of differences. ES was classified as follows: < 0.1 = insignificant difference, ≤ 0.2 = small difference, ≤ 0.6 = moderate difference, ≤ 1.2 = large difference, ≤ 2.0 = very large difference, and ≤ 4.0 = extremely large difference based on previous research (Hopkins et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2019).

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to determine the differences in influencing factors between the CSL and EPL. In this analysis, the time consumed by each stoppage factor was taken as the independent variable, while the actual playing time was the dependent variable.

where represents either the CSL or EPL, b is the constant term, and is the error term. The independent variables (X1–X18) and the dependent variable (Y) of the two leagues were subsequently inserted into the multiple linear regression model. In the results, the significance value, as the standardized coefficient, determined whether the independent variable (i.e., stoppage factors) contributed to the dependent variable (i.e., actual playing time). The beta value determined the degree of influence of the independent variables on the dependent variable. The analyses were done using IBM SPSS 22.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS Inc.). This study was complied according to the ethical principles stated by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 3 shows that the average actual playing time between the CSL and the EPL was statistically different (p = 0.03 < 0.05), and the effect size values showed a moderate difference (0.6 < ES = 0.610 < 1.2). The average match density (%) also showed a statistically significant difference (p = 0.008 < 0.05), the effect size values showed a minor difference (0.2 < ES = 0.513 < 0.6), and the average game time did not show any statistical difference.

Table 3. Comparison of average data of matches of the Chinese Super League (CSL) and English Premier League (EPL; time unit: minutes).

The average time spent on out-of-bounds between the CSL and the EPL was statistically different (p = 0.007 < 0.05), and the effect size showed a minor difference (0.2 < ES = 0.556 < 0.6). The average time spent on general fouls was also statistically different (p = 0.001 < 0.05), and the effect size showed a large difference (1.2 < ES = 1.245 < 2). The average time spent on players’ minor injuries was statistically different (p = 0.015 < 0.05), and the effect size showed a minor difference (0.2 < ES = 0.272 < 0.6). The time spent on field interferences by off-field factors was statistically different (p = 0.042 < 0.05).

As is shown in Tables 4, 5, the models of actual playing time of CSL and EPL are significant. X1–X11 had an important impact on stoppage times for both the CSL and EPL. In the CSL, penalty kicks (X13), player conflict (X16), and player complaints (X18) influenced stoppage time, while in the EPL, minor player injuries were an impact factor. The remaining variables were not significant in the regression models.

This study compared the factors that influenced actual playing time between the CSL and EPL. The results showed that the actual playing time in the CSL was less than in the EPL. The CSL spent more time on general fouls (X6), player minor injuries (X15), and off-field interferences (X17), while the EPL spent more time on out-of-bounds (X1). The factors that affected actual playing time also differed. For the CSL, anthropogenic factors dominated, and the primary factors included penalty kicks (X13), player conflict (X16), and player complaints (X18), while the primary factor for the EPL was minor player injuries (X15).

The CSL match density in the 2019 season reached 54.76%, slightly lower than for the EPL, which is generally consistent with the findings of studies by Augste and Lames (2008) and Siegle and Lames (2012a). Tschan et al. (2001) also found that in the European leagues, 32% of game time is consumed by stoppages; the same study found that in the World Cup, only 61–69% of the game time was dedicated to actual playing time. Similar to previous studies (Sun et al., 2014), in the CSL’s games, general fouls took more time and had a greater impact on actual playing time. Additionally, minor player injuries and off-field interruptions took more time. Out-of-bounds and throw-ins took more time in the EPL games than in CSL games. Another study found that the time consumed by free kicks and player injuries in CSL games in the 2008 season was higher than in the 13th European Football Championship in 2008 (Dong, 2012), which is consistent with the results of the current study. In other words, referees in the CSL stopped the game more frequently for minor fouls, which led to more interruptions to the game and a consequent increase in time consumption. Comparatively, the fluidity of the EPL games was better than in the CSL games, and referees were able to control the pace of the game and make good use of advantage rules. Moreover, a free kick after a foul in the CSL tended to be slightly slower due to various interferences, such as improper positioning or player blocking (Greve et al., 2019). Furthermore, players sometimes pretended to be injured after a foul, which increased the time consumed in a game.

Previous studies found that high-intensity games tend to be accompanied by longer intervals (Hernández-Moreno et al., 2011). Compared to other leagues, the EPL has a faster rhythm (Jamil and Kerruish, 2020); thus, players may take advantage of stoppages to recover from a high-intensity game, which can explain the greater time consumption during throw-ins in EPL games. In addition, Siegle and Lames (2012b) found that throw-ins in the defensive zone took more time. This may be because losing possession in the defensive zone could more easily lead to conceding a goal. Another possible reason may be that players face more intense running in the defensive zone and they want to recover from fatigue by taking opportunities to rest when the ball is out of play, like during throw-ins.

Stoppages in CSL games included off-field interferences, which were not found in the EPL games. Zhao and Zhang (2021) found that spectators also impacted the actual playing time by negatively affecting both players and referees. For example, referees in Major League Soccer (MLS) tend to add an extra 33 s when the home team is down by one goal (Yewell et al., 2014). EPL referees also demonstrate a preference for the home team (Boyko et al., 2007). In the CSL, home teams also enjoy an advantage (Peng et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019) as the home teams are better off than the away team regarding offense indicators. Han et al. (2020) showed that after the introduction of objective VAR technology, home advantages conferred by referees decreased partially, based on the indicators for red and yellow cards and fouls, which were previously largely determined by referees’ vulnerability to the home team spectators. Although the use of new technology such as VAR has reduced home advantage in recent years (Han et al., 2020), the influence of spectators cannot be completely eliminated. Thus, a higher level of professional skills in both players and referees is required to reduce the impact of spectators.

In CSL games, penalty kicks, player conflict, and player complaints impacted actual playing time. Although there was no significant difference in total time compared to the EPL, these factors significantly impacted actual playing time in CSL games. Typically, when a penalty kick is awarded in CSL games, the player complains to the referee, which may result in the referee presenting a yellow card or even sending a player off the field. Players’ behaviors not directly related to the game actions, such as gathering and inter-player conflict, also waste time in a game. Previous studies have suggested that actual playing time in the CSL is likely influenced by referees’ ability to control the game, players’ professional and ethical qualities, the presentation of red and yellow cards, players disregarding referees’ decisions, players’ attitude toward the game, and players’ technical and tactical abilities (Jiang, 2013; Li and Lu, 2013; Sun et al., 2014; He, 2016; Li, 2019; Zhao, 2019). Penalty kicks, player conflict, and player complaints may reflect the players’ attitude to the game, or lack of technical and tactical ability; moreover, it has been suggested that players in the CSL are not afraid of being shown a second yellow card (Jamil and Kerruish, 2020). Such an attitude may lead to players committing fouls in the penalty area or being prone to taking excessive defensive actions that cause player conflict and penalties, or even lead to being sent off the field. Referees may also contribute to this situation. In CSL games, referees are often too hesitant to show a second yellow card (Mao et al., 2016), consequently, referees find it more difficult to act in time to control a situation on the field in the case of player conflict or player complaints, which encourages such behaviors.

The EPL games are typically played at a fast pace (Jamil and Kerruish, 2020), with fierce confrontation and frequent player minor injuries (Rahnama et al., 2002), especially in the first and last 15 min of the game. In the first 15 min, player injuries may result from intense player confrontation due to excitement, while player injuries in the last 15 min may be due to fatigue. Studies have also shown that stoppages are more likely to occur toward the end of a game (Carling and Dupont, 2011) and that many minor injuries are caused by fatigue. In contrast, more frequent stoppages and time consumption in the CSL dilute the intensity of a game; however, whether this reduces player injuries still needs to be examined in a further study.

Although this study provided significant findings, the study has a few limitations due to the small number of samples and the fact that contextual variables were not considered. Future studies should thus include these two aspects to ensure a more comprehensive view of influencing factors in the elite soccer league and soccer games in general.

The study’s main findings demonstrate that the average actual playing time and average density of EPL games were significantly higher than in the CSL games, showing moderate differences and minor differences, respectively. The average time consumed by general fouls, minor player injuries, and off-field interferences in the CSL games was significantly higher than in the EPL games, while the average time consumed by out-of-bounds was significantly lower than in the EPL. Thus, more anthropogenic factors affected the actual playing time in the CSL than in the EPL, while non-anthropogenic factors affected the two leagues almost similarly. These results provide a reference for coaches to design effective training and develop strategies before a game to enhance players’ ability under high intensity conditions. Furthermore, they can also guide referees to make proper plans for the coming game; thus, securing a more favorable outcome.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the (patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin) was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

YZ conceptualized the study, wrote the original draft preparation, and contributed to the methodology and data collection. TL reviewed and edited the manuscript and helped to improve this work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (18CTY011).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.907336/full#supplementary-material

Augste, C., and Cordes, O. (2016). Game stoppages as a tactical means in soccer–a comparison of the FIFA world cups™ 2006 and 2014. Int. J. Perform. 16, 1053–1064. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2016.11868947

Augste, C., and Lames, M. (2008). “Differenzierte betrachtung von taktischem verhalten und belastungsstrukturen auf der basis von spielunterbrechungen im fußball,” in Sportspielkulturen Erfolgreich Gestalten. eds. A. Woll, W. Klöckner, M. Reichmann, and M. Schlag (Hrsg.) (Hamburg: Czwalina), 113–116.

Boyko, R. H., Boyko, A. R., and Boyko, M. G. (2007). Referee bias contributes to home advantage in English premiership football. J. Sports Sci. 25, 1185–1194. doi: 10.1080/02640410601038576

Carling, C., and Dupont, G. (2011). Are declines in physical performance associated with a reduction in skill-related performance during professional soccer match-play? J. Sports Sci. 29, 63–71. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2010.521945

Castellano, J., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., and Álvarez, D. (2011). Contextual variables and time-motion analysis in soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 32, 415–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271771

China Football Federation. (2019). The 2019 Chinese Premier League annual awards ceremony was held in Shanghai (2012). Available at: http://www.thecfa.cn/zyls1/20191207/28400.html. (Accessed December 7, 2012).

Cook, B. G., and Goff, J. E. (2006). Parameter space for successful soccer kicks. Eur. J. Phys. 27, 865–874. doi: 10.1088/0143-0807/27/4/017

Dong, K. (2012). Comparative study on stoppage time of elite soccer games in China and other countries. master’s thesis. Beijing: Beijing Sport University).

Gai, Y., Volossovitch, A., Leicht, A. S., and Gómez, M. Á. (2019). Technical and physical performances of Chinese super league soccer players differ according to their playing status and position. Int. J. Perform. 19, 878–892. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2019.1669356

Greve, H. R., Rudi, N., and Walvekar, A. (2019). Strategic rule breaking: time wasting to win soccer games. PLoS One 14:e0224150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224150

Han, B., Chen, Q., Lago-Peñas, C., Wang, C., and Liu, T. (2020). The influence of the video assistant referee on the Chinese super league. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 15, 662–668. doi: 10.1177/1747954120938984

He, X. (2016). Comparative study on factors impacting effective playing time in elite league matches in China and other countries. master’s thesis. Beijing: Beijing Sport University.

Hernández-Moreno, J., Gómez Rijo, A., Castro, U., González Molina, A., Quiroga-Escudero, M. E., and González Romero, F. (2011). Game rhythm and stoppages in soccer. A case study from Spain. J. Hum. Sport. 6, 594–602. doi: 10.4100/jhse.2011.64.03

Hopkins, W. G., Marshall, S. W., Batterham, A. M., and Hanin, J. (2009). Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 3–12. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278

Jamil, M., and Kerruish, S. (2020). At what age are English premier league players at their most productive? A case study investigating the peak performance years of elite professional footballers. Int. J. Perform. 20, 1120–1133. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2020.1833625

Jiang, H. (2013). Study on characteristics on ineffective playing time in elite league matches in China, Japan and South Korea. Master’s thesis. Beijing: Beijing Sport University.

Koo, T. K., and Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Lago-Peñas, C., Rey, E., and Lago-Ballesteros, J. (2012). The influence of effective playing time on physical demands of elite soccer players. Open Sports Sci. J. 5, 188–192. doi: 10.2174/1875399X01205010188

Li, Y. (2019). Comparative study on factors impacting pure playing time in elite league matches in China and other countries. master’s thesis. Shandong: Shandong Normal University.

Li, H., and Lu, Z. (2013). Comparative analysis on features of stoppage in professional soccer league in China and Japan. Sports Res. Educ. 28, 92–109.

Linke, D., Link, D., Weber, H., and Lames, M. (2018). Decline in match running performance in football is affected by an increase in game interruptions. J. Sports Sci. Med. 17, 662–667.

Liu, T., García-De-Alcaraz, A., Zhang, L., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Exploring home advantage and quality of opposition interactions in the Chinese football super league. Int. J. Perform. 19, 289–301. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2019.1600907

Liu, H. G., and Hopkins, W. (2017). A new sport statistical point of view: data and numerical extrapolation. Sci. Sports. 38, 27–31.

Mao, L., Peng, Z., Liu, H., and Gómez, M. A. (2016). Identifying keys to win in the Chinese professional soccer league. Int. J. Perform. 16, 935–947. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2016.11868940

Peng, C. (2017). Analysis of women’s football match intensity of the 31st Olympic Games. master’s thesis. Wuhan: Wuhan Sports University.

Peng, Z., Liu, H., and Guo, W. (2016). Tentative study on home team advantage in China super league matches. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 35, 106–111.

Rahnama, N., Reilly, T., and Lees, A. (2002). Injury risk associated with playing actions during competitive soccer. Br. J. Sports Med. 36, 354–359. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.5.354

Rey, E., Kalén, A., Lorenzo-Martínez, M., López-Del Campo, R., Nevado-Garrosa, F., and Lago-Peñas, C. (2020). Elite soccer players do not cover less distance in the second half of the matches when game interruptions are considered. J. Strength Cond. Res. Publish. 16, 840–847. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003935

Siegle, M., and Lames, M. (2012a). Game interruptions in elite soccer. J. Sports Sci. 30, 619–624. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.667877

Siegle, M., and Lames, M. (2012b). Influences on frequency and duration of game stoppages during soccer. Int. J. Perform. 12, 101–111. doi: 10.1080/24748668.2012.11868586

Sun, Y., Li, C., and Pei, J. (2014). Features of stoppage in soccer games in China and other countries and the significance on training. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 33, 114–129.

Tschan, H., Baron, R., Smekal, G., and Bachl, N. (2001). Belastungs-und Beanspruchungsprofil im Fußball aus physiologischer Sicht. Öst. J. Sportmedizin. 1, 7–18.

Yang, G., Leicht, A. S., Lago, C., and Gómez, M. Á. (2018). Key team physical and technical performance indicators indicative of team quality in the soccer Chinese super league. Res. Sports Med. 26, 158–167. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2018.1431539

Yewell, K. G., Caudill, S. B., and Mixon, F. G. Jr. (2014). Referee bias and stoppage time in major league soccer: a partially adaptive approach. Econometrics. 2, 1–19. doi: 10.3390/econometrics2010001

Zhao, Z. (2019). Study and analysis on dead ball time for the Chinese Super League. master’s thesis. Guangzhou: Guangzhou Sport University.

Zhao, Y., and Zhang, H. (2021). Effective playing time in the Chinese super league. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 16, 398–406. doi: 10.1177/1747954120965751

Keywords: playing time, Chinese Super League, English Premier League, football (soccer), soccer (football), game stoppage time

Citation: Zhao Y and Liu T (2022) Factors That Influence Actual Playing Time: Evidence From the Chinese Super League and English Premier League. Front. Psychol. 13:907336. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.907336

Received: 29 March 2022; Accepted: 27 May 2022;

Published: 04 July 2022.

Edited by:

Hongyou Liu, South China Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Rabiu Muazu Musa, University of Malaysia Terengganu, MalaysiaCopyright © 2022 Zhao and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tianbiao Liu, bHRiQGJudS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.