95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 15 June 2022

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.901646

The research examined the relationship between supportive parenting styles (warmth, structure, and autonomy support) and emotional well-being and whether they are mediated by basic psychological need satisfaction. It also explores thwarting parenting styles (rejection, chaos, and coercion) that may be associated with emotional ill-being, mediated by basic psychological needs frustration. This study involved 394 Indonesian adolescents aged 11–15 years old (49.5% boys, 50.5% girls) as the participants. We employed the structural equation model (SEM) analysis to evaluate the hypotheses. The research found that basic psychological needs satisfaction fully mediated the relationship between supportive parenting styles and emotional well-being; basic psychological needs frustration fully mediated the relationship between thwarting parenting styles and emotional ill-being (Chi-Square = 434.39; df = 220; p = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.91; GFI = 0.91; SRMR = 0.05). Interestingly, the findings indicate that the thwarting parenting style positively influences basic psychological needs satisfaction. The research concludes that supportive parenting enhances the well-being of adolescents by satisfying their basic psychological needs. However, thwarting parental behaviors did not forestall the satisfaction of needs. The way Indonesian adolescents perceived the thwarting parenting style was discussed.

Emotional well-being is essential in adolescents experiencing multiple transitions (physiological, psychosocial, academic, and social) and shifts in family dynamics. Those transitions could bring pressures that may induce stress, leading to mental health problems (Johnson and Greenberg, 2013). Kim-Cohen et al. (2003) further suggest that the onsets of mental health problems usually appear in late childhood and adolescence. Therefore, emotional well-being is crucial for adolescents to have flourishing mental health. Adolescents with emotional well-being tend to be physically and mentally healthy. They can avoid abusing the internet and drugs (Saha et al., 2014), gain higher academic achievement, possess good intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, and apply a better coping strategy when facing life problems (Shek and Lin, 2014). Those positive traits may continue in the future, as positive well-being experienced in adolescents tends to remain in adulthood.

One theory that concerns individual well-being is The Self-Determination Theory (SDT), stating that individuals’ three basic psychological needs, namely the need for relatedness, competence, and autonomy, could be satisfied or thwarted. The satisfaction of relatedness needs will make individuals feel connected in a quality relationship with others, the satisfaction of competence needs will make individuals feel productive, and the satisfaction of autonomy needs will encourage individuals to control their choice of behavior (Ryan and Deci, 2017). The satisfaction of all the needs leads to the achievement of emotional well-being. Many studies reported a relationship between positive outcomes and satisfaction, in which psychological needs are associated with vital and energetic feelings (Chen et al., 2015b; Pinquart, 2016), life satisfaction (DeHaan et al., 2016), and more significant positive effect (Sheldon and Bettencourt, 2002).

Contrarily, frustration in relatedness needs might encourage individuals to feel a sense of rejection and alienation. Unfulfillment of the competence needs tends to lead to feelings of inferiority and helplessness, while the frustration of autonomy needs creates a sense of coerciveness to individuals (Ryan and Deci, 2017). Vansteenkiste and Ryan (2013) suggest that frustration of the needs will result in emotional ill-being. Furthermore, the effect of basic need’s frustration on mental health problems includes symptoms of eating disorders (Boone et al., 2014), anxiety and somatization (Cordeiro et al., 2016), and sleep deprivation (Campbell et al., 2017).

Initially, needs satisfaction was identified as a uni-dimensional construct ranging from low to high (Sheldon et al., 1996; Deci et al., 2001; Jang et al., 2009). However, further studies found that although low needs satisfaction is associated with lower well-being, it is not directly associated with ill-being (Ryan et al., 1995; Adie et al., 2008; Quested and Duda, 2010). Therefore, Bartholomew et al. (2011) propose a dual-process model to distinguish need (dis)satisfaction and need frustration. In other words, basic psychological needs satisfaction and frustration are defined as multidimensional. These notions are supported by Vansteenkiste and Ryan (2013), reporting the relationship between psychological need satisfaction and frustration is asymmetrical, whereby low need satisfaction is not a condition for the presence of need frustration. On the contrary, a high need frustration implies a low need satisfaction.

To date, SDT researchers agree that needs satisfaction and needs frustration are different constructs, as they have different antecedents and outcomes (Chen et al., 2015a; Haerens et al., 2015; Jang et al., 2016; Bartholomew et al., 2018). Chen et al. (2015a) further developed a measurement of BPNSFS that views needs satisfaction and needs frustration as different constructs. Research on BPNSFS in various populations and languages corroborates the notion that the needs satisfaction and needs frustration are distinct constructs; thus, their measurement and interpretation should be differentiated. To conclude, as the basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration are viewed as different constructs, to find that individuals have high satisfaction and high frustration at the same time is possible (Cordeiro et al., 2016; Nishimura and Suzuki, 2016; Valle et al., 2018; Rodrigues et al., 2019; Liga et al., 2020).

Whether the basic psychological needs in adolescents are fulfilled or thwarted, strongly associated with parents, the social context has been known to have a significant impact on the development, functioning, and well-being (Costa et al., 2019) as well as the ill-being of adolescents. Several studies have documented the impact of parenting on adolescents’ well-being. Niemiec et al. (2006), for example, reported that support from parents affects adolescents’ well-being, while Wimsatt et al. (2013) suggest that there is a relationship between parental involvement and positive affect. Whereas, studies also found that parenting can affect adolescents’ ill-being. For instance, King et al. (2018) found that poor monitoring/supervision, inconsistent discipline, and corporal punishment are related to depressive symptoms. In addition, a higher risk for suicidal adolescents increases in conjunction with parenting behaviors.

Parents’ influence on their children could be understood from three aspects: parenting goal (the goals parents promote), parenting style (emotional climate within the family), and parenting practice (behaviors that parents do to reach the parenting goals) (Darling and Steinberg, 1993). Parenting style and parenting practice are often used interchangeably. Nevertheless, the two terms should be distinguished as the former focuses on how parents do the parenting, while the latter focuses more on concrete behaviors parents do (Power, 2013). Since the 1940s, more attention has been given to research on parenting styles than parenting practices, which cannot predict individual differences in children’s social/emotional development (Orlansky, 1949).

Parenting style can be investigated by two major approaches: the dimensional approach studying each parenting dimension independently, and the typological approach combining specific dimensions of parenting into parenting styles (Power, 2013). Based on an extensive literature review on parenting dimensions, Skinner et al. (2005) propose six-core parenting dimensions: warmth, structure, autonomy support, rejection, chaos, and coercion. The warmth dimension emphasizes feelings of affection, unconditional love, and emotional support; the structure dimension prioritizes clear explanation and proper limitation, while the autonomy-supportive dimension is indicated by giving opportunities to express feelings and opinions comfortably. On the contrary, rejection is usually indicated by negative and hostile expressions shown by parents, chaos is shown by a lack of consistency in rules and parental behaviors, and coercion is characterized by strict parental control.

As for parenting typologies, Baumrind’s typological approach has been considered one of the prominent theories combining two orthogonal dimensions of parenting: responsiveness and demandingness (Darling and Steinberg, 1993; Martinez et al., 2019; Martinez-Escudero et al., 2020). Demandingness refers to setting up a reasonable demand accompanied by monitoring and disciplinary efforts (Baumrind, 1991; Garcia et al., 2020). Responsiveness is indicated by intentional action to encourage individuality, self-regulation, and self-assertion while considering the child’s personality (Baumrind, 1991; Garcia et al., 2020). The combination of high demandingness and high responsiveness forms an authoritative parenting style, a combination of high demandingness and low responsiveness form an authoritarian parenting style, while a combination of high responsiveness and low demandingness forms a permissive parenting style (Baumrind, 2013).

Skinner et al. (2005) suggests that different dimensions could be aggregated. However, unlike Baumrind combining two dimensions into a particular parenting style, Skinner proposes three dimensions aggregated into supportive parenting (warmth, structure, and autonomy support) and unsupportive parenting (rejection, chaos, and coercion). This categorization firstly was proposed based on the SDT framework, which posits that children have three basic psychological needs: related, competence, and autonomous. The empirical finding further supports this categorization, which showed high intercorrelation among warmth, structure, and autonomy support, and among rejection, chaos, and coercion. Skinner’s and Baumrind’s parenting style categorization might sound similar, especially between authoritative and supportive parenting styles. Nevertheless, this study uses Skinners’ proposition, as it separates autonomy support from structure/demandingness (Skinner et al., 2005). The recent studies under the umbrella of SDT corroborated Skinners’ categorization. Aligns with SDT tenets about basic psychological needs; warmth, structure, and autonomy support are labeled need-supportive parenting, while rejection, chaos, and coercion are labeled need-thwarting parenting (Costa et al., 2019; Soenens et al., 2019).

Regarding the impact of parenting styles on children’s outcomes, several factors should be taken into consideration. Cultural context (Garcia et al., 2020; Gimenez-Serrano et al., 2021; Gimenez-Serrano et al., 2022), and neighborhood (Sandoval-Obando et al., 2022) play an important role in the association between parenting style and children’s outcomes. Numerous research under Baumrind’s parenting style framework found that in the Western population, authoritative parenting is well-known as the best parenting style (Devi and Uma, 2013; Sahithya et al., 2019). However, the best parenting style is not always the same in the different populations and cultures. In the Asian and African contexts, the authoritarian parenting style is considered better to socialize children (White et al., 2009). Therefore, the recommendation to apply a particular parenting style should consider the cultural context (Pinquart and Kauser, 2018).

As for Skinner’s categorization, the reports on the impact of supportive and thwarting parenting styles in a different culture have also been documented. Some studies suggest that the parenting style has a similar impact despite the cultural setting. In Western countries, supportive parenting promotes the child’s positive outcomes by enhancing children’s well-being, whereas thwarting parenting is associated with internalizing or externalizing problems (Joussemet et al., 2008; Soenens et al., 2017). A similar finding was reported in non-Western populations, such as Taiwanese populations. The study found the effect of need-supportive parenting on intrapersonal and interpersonal adaptation was mediated by need satisfaction (Wu et al., 2015). These findings might be expected as the SDT suggests the notion applied universally. Nevertheless, given the complex characteristics of the cultural context and the more research under SDT conducted in various cultures, different findings might be revealed.

The relationship between the parenting dimensions and satisfaction of basic psychological needs has been documented in several studies. Skinner et al. (2005) and Joussemet et al. (2008) found that parental warmth plays a vital role in adolescents’ relatedness, while parental autonomy support fosters adolescents’ autonomy. This finding is corroborated by Flamm and Grolnick (2013), who found that the parental structure shapes experiences of competence. Likewise, the satisfaction of the three needs is substantially influenced by parental structure and autonomy support (Abidin et al., 2019). Furthermore, Kocayoruk (2012), investigating the relationship between parenting behavior, basic needs, and adolescents’ well-being, revealed that parental support indirectly influences adolescents’ subjective well-being, mediated by basic psychological needs. Costa et al. (2015) reported that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs mediated the relationship between perceptions of psychological control and internalizing distress. Costa et al. (2019) further explained that basic psychological needs were mediating parenting style and outcomes in Italian adolescents. The findings indicate that supportive parenting practice (autonomy support, structure, and warmth) increases need fulfillment and adjustment, while thwarting parenting practice (psychological control, chaos, and rejection) has the opposite effect on need fulfilment and adjustment. Furthermore, the relationship between parenting and adolescents’ adjustment are mediated by the basic psychological needs, which are need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

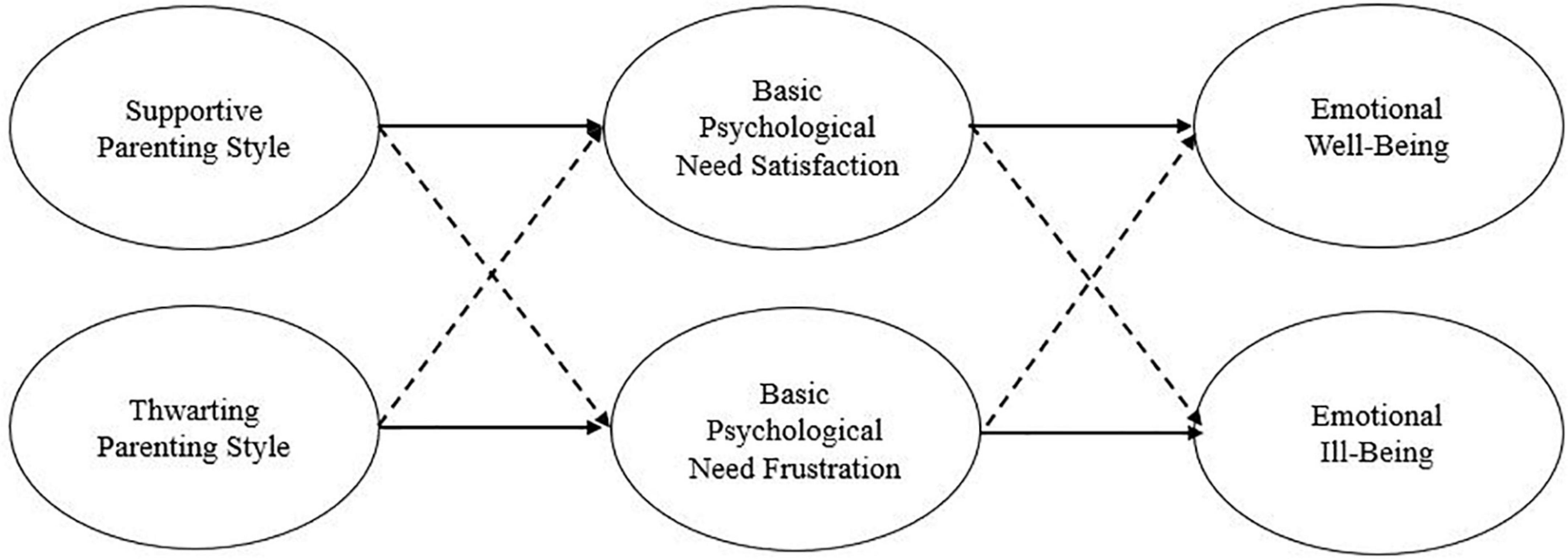

Several researchers reported the relationship between parenting behavior, basic psychological needs satisfaction, well-being, and ill-being. However, studies that examine whether basic psychological needs frustration mediate thwarting parenting styles and emotional ill-being are relatively scarce. According to SDT, basic psychological needs frustration is a different construct from basic psychological needs satisfaction; thus, research focusing on examining basic psychological needs frustration as a mediating variable is crucial. The current study aims to examine the relationship between supportive parenting styles and emotional well-being, and whether the basic psychological need satisfaction mediates the relationship. Moreover, to fill the gaps of the previous research, this research also examines the relationship between thwarting parenting styles and emotional ill-being and whether basic psychological need frustration mediates the relationship (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The conceptual model of relationships between parenting style, basic psychological need, and well-being. The solid line indicates a positive relation. The dashed line indicates a negative relation.

Based on previous research, we expect that a supportive parenting style (warmth, structure, autonomy support) will positively influence basic psychological needs satisfaction, which will result in higher emotional well-being; whereas thwarting parenting style (rejection, chaos, and coercion) will positively influence basic psychological needs frustration which will result in higher emotional ill-being.

The participants of this study were 394 students from three senior high schools, of which 49.5% were males and 50.5% were females. The age of the participants ranged from 11 to 15 years old (M = 12.98, SD = 0.77) and the proportion of the participants, based on their grades at school, were: 64.23% 7th-year students, 31.97% 8th-year students, and 3.81% 9th-year students.

The Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Padjadjaran has given this study their approval (No. 357/UN6.KEP/EC/2018). Prior to signing the consent form, the participants have received information about the aim, data collection procedure, and data protection of the study. The participants, guided by the research assistants, completed the paper-and-pencil questionnaires for 15–30 min in the regular class periods.

The Parents as Social Context Questionnaire (PSCQ)- Adolescent Report in Indonesian version (Abidin et al., 2019) was employed to measure the parenting style. The instrument consists of six parental dimensions, namely warmth (e.g., “My parents think I am special”), rejection (e.g., “Nothing I do is good enough for my parents”), structure (e.g., “When I want to do something, my parents show me how”), chaos (e.g., “My parents punish me for no reason”), autonomy support (e.g., “My parents trust me”), and coercion (e.g., “My parents are always telling me what to do”), with four items for each dimension. Participants answered the questionnaire on 4-point Likert scales (1 = not at all true to 4 = very true). The research reported that the PSCQ had good internal consistency reliability, as the scores for warmth, rejection, structure, chaos, autonomy support, and coercion are 0.83, 0.80, 0.79, 0.74, 0.70, and 0.66, respectively.

The Indonesian version of the Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSF), adapted from Chen et al. (2015a) by Abidin et al. (2021) was employed to measure basic psychological needs. Generally, the scale consists of six subscales measuring satisfaction of autonomy (e.g., “I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake”), relatedness (e.g., “I feel connected with people who care for me and for whom I care),” and competence (e.g., “I feel capable at what I do”) and the frustration of autonomy (e.g., “I feel pressured to do too many things”), relatedness (e.g., “I feel the relationship I have are just superficial”), and competence (e.g., I feel insecure about my abilities”), with four items for each subscale. However, in the Indonesian version, two items from the autonomy frustration (“Most of the things I do feel like I have to” and “My daily activities feel like a chain of obligation”) were excluded from the instruments due to the negative factor loading. Participants rated the instrument on the 5-point Likert scale (1, not true at all; 5, completely true). The internal consistency for the basic psychological needs satisfaction and frustration subscales were acceptable, with α = 0.791 and α = 0.709, respectively.

Subjective feelings of well-being and ill-being were measured by the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al., 2010). SPANE-P (Positive Emotional Experience; e.g., “joyful”) and SPANE-N (Negative Emotional Experience; e.g., “angry”) were measured by six items in the instrument. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very rarely or never, 5 = very often or always). This scale has achieved internal consistency in the Indonesian sample with α = 0.77 for the SPANE-P and α = 0.75 for the SPANE-N.

A preliminary exploration related to the missing value was conducted using Little’s MCAR test. Descriptive statistics, the means and standard deviations for each variable were described. Then, Pearson’s product-moment correlations were selected to examine the relationship between variables and the existence of multicollinearity. Next, serial structural model equation (SEM) examinations were administered to investigate the mediation role of basic psychological needs in the relation between parenting style and emotional well-being. Basically, this research consisted of two outcome variables (emotional well-being and emotional ill-being), two predictor variables (supportive parenting style and thwarting parenting style), and two mediator variables (basic psychological needs satisfaction and basic psychological needs frustration). Thus, the evaluation of mediation variables using SEM examinations followed Holmbeck (1997) causal approach.

First, the analysis was conducted to gain an adequate overall model fit when the predictor variables are regressed on the outcome variables (Model 1). The path coefficients are expected to be significant. Then, the analysis was followed by assessing the overall model fit when predictor variables are regressed on the mediator variables, and simultaneously the outcome variables are regressed on the mediator variables (Model 2). The model fit must be good, and all path coefficients must be significant. In the final step, the addition of the paths on Model 2, between predictor and outcome variables is not constrained to zero and has to be significant. The mediational effect exists when the addition paths between predictors and outcomes in the unconstrained model do not significantly increase the fit compared to the constrained model.

Several models fit indices were used in this study, including chi-square (χ2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), an absolute fit index GFI, and two other common fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMSR). The cut-off point for fit indices followed these criteria: the values of GFI and CFI should be at least 0.90, the RMSEA and SRMSR values should be less than 0.08 (Hair et al., 2014). Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS) 22.0 for Mac was utilized to perform descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis. Meanwhile, the SEM was administered using the Lavaan package on R programming (Rosseel, 2012).

The examination of missing values indicated approximately 21 (5.32%) missing values were found from the participants. The maximum missing value of each participant is 5.60%. A Little’s MCAR test found that the missing values were random, as χ2 = 605.49 (df = 592; p = 0.34); thus, we employed the expectation-maximization method for missing value imputation (Hair et al., 2014). The means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between the observed variables for each construct are shown in Table 1.

As expected, emotional well-being correlates negatively with emotional ill-being. Emotional well-being has a positive correlation with three basic needs satisfaction and three dimensions comprising supportive parenting style, while correlating negatively with three basic psychological needs frustration and three dimensions comprising thwarting parenting style. Such a paradoxical pattern identified in emotional ill-being, as it has a negative correlation with three basic needs satisfaction and three dimensions comprising supportive parenting style, but correlates positively with three basic psychological needs frustration and three dimensions comprising thwarting parenting. Unexpectedly, coercion as one of the dimensions of thwarting parenting style does not significantly correlate with emotional well-being and ill-being, even though it has a significant correlation with other thwarting parenting dimensions (i.e., rejection and chaos).

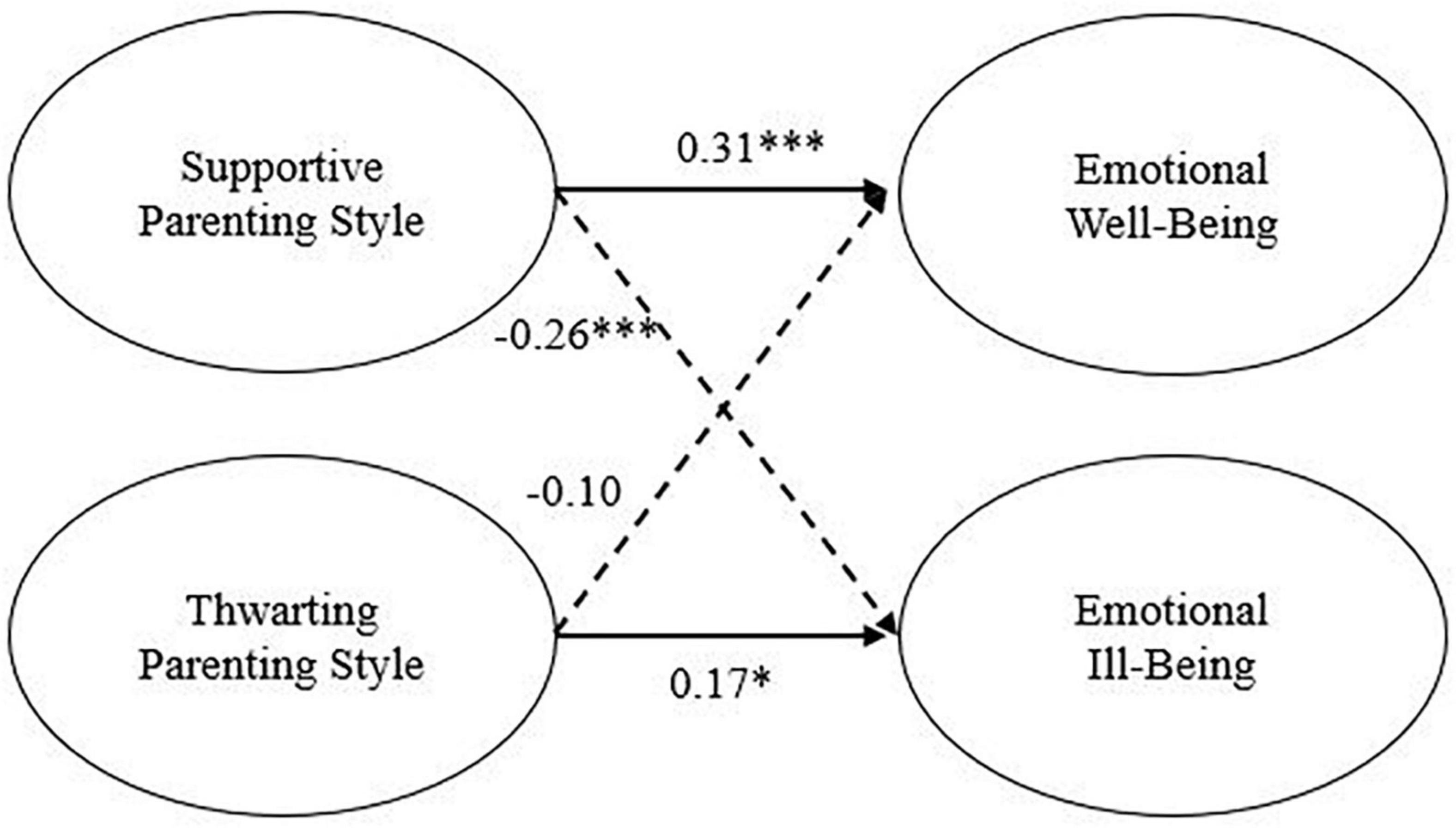

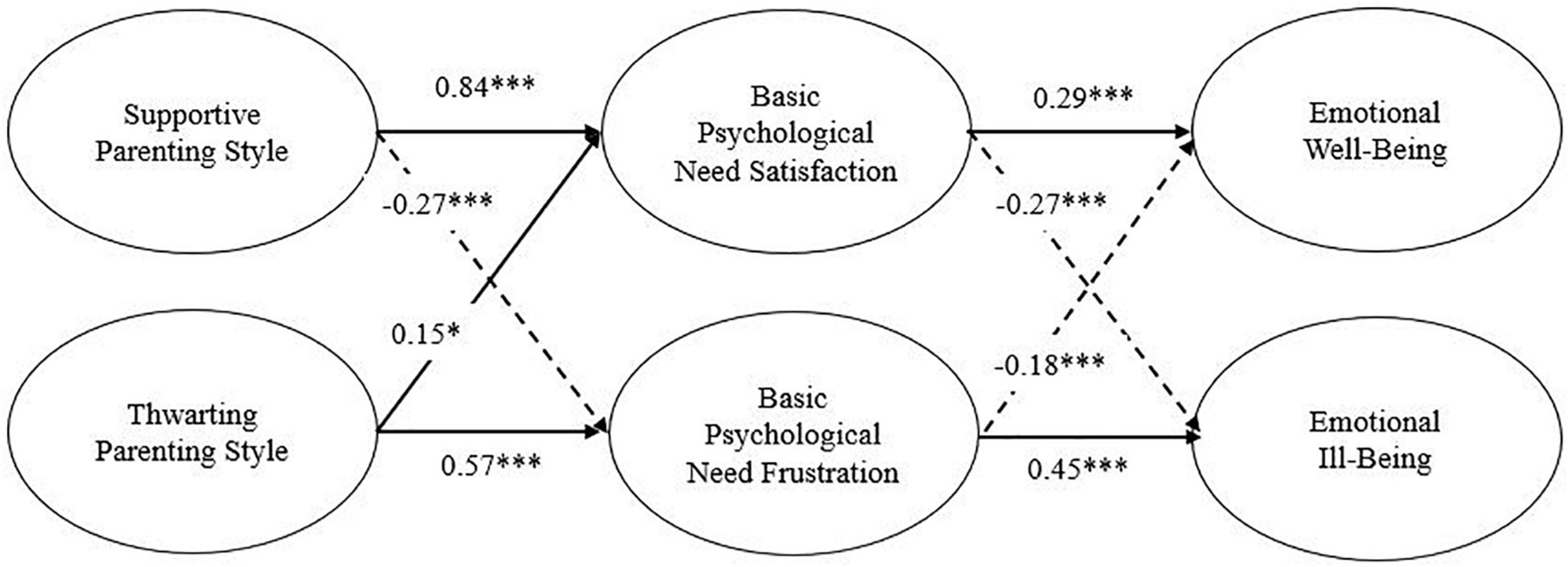

The analyses of mediational effect consisted of three steps of structural equation models. First, Model 1, analyzing the direct effect of the supportive parenting style and thwarting parenting style on emotional well-being and emotional ill-being, showed a good model fit (see Table 2) and significant path coefficients. Specifically, Figure 2 shows that the supportive parenting style had a significant positive direct effect on emotional well-being and a significant negative direct effect on emotional ill-being. Conversely, thwarting parenting style only had a significant positive direct effect on emotional ill-being. Next, the mediation variables (basic psychological needs satisfaction and basic psychological needs frustration) were included in Model 2, in which the goodness of fit for the proposed model was satisfactory according to all fit indices (see Table 2). Figure 3 shows that all estimated parameters were significant and of acceptable magnitude. Supportive parenting style demonstrated a significant and high positive direct relationship with basic psychological need satisfaction (γ = 0.84, p < 0.001) and a positive indirect relationship with emotional well-being (γ = 0.24), mediated by basic psychological need satisfaction. While thwarting parenting style had a positive and direct relation with basic psychological need frustration (γ = 0.57, p < 0.001) and a positive indirect relationship with emotional ill-being (γ = 0.26), mediated by basic psychological need frustration. In addition, the basic psychological need had a direct and positive association with emotional well-being (β = 0.29, p < 0.001). Similarly, a positive relationship was found between basic psychological needs frustration, and emotional ill-being (β = 0.45, p < 0.001). Finally, negative associations were found between supportive parenting style and basic psychological need frustration, basic psychological need satisfaction and emotional ill-being, and between psychological need frustration and emotional well-being. A different result is found on the relationship between thwarting parenting style and basic psychological need satisfaction, which has no significant association. This model accounted for 20% of the variance in emotional well-being and 29% in emotional well-being.

Figure 2. Standardized structural equation of Model 1. Solid lines indicated positive relations, and dashed lines indicated negative relations. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3. Standardized structural equation of Model 2. Solid lines indicated positive relations, and dashed lines indicated negative relations. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

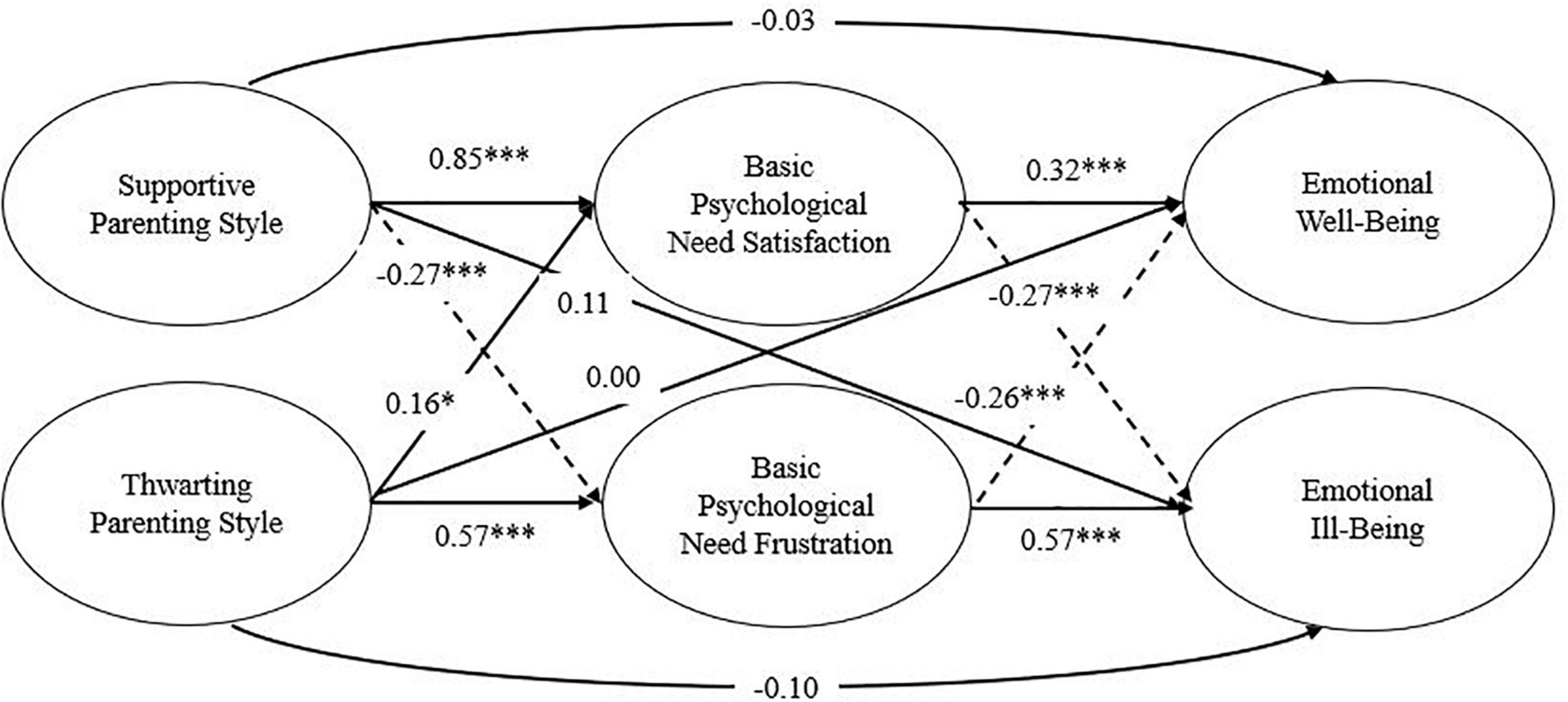

The analysis of Model 3 was almost similar to Model 2, except the model also examined the significance of direct paths between predictor variables and outcome variables. The results showed that the direct effect from predictor variables to outcome variables was not significant (Figure 4) and the overall model fit of Model 3 was not different from Model 2 (Table 2). The results concluded that the basic psychological needs satisfaction and basic psychological needs frustration fully mediated the relationship between parenting style and emotional well-being.

Figure 4. Standardized structural equation of Model 3. Solid lines indicated positive relations, and dashed lines indicated negative relations. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The study examines the relationship between supportive parenting styles and emotional well-being, and whether basic psychological need satisfaction mediates the relationship. It also examines the relationship between thwarting parenting styles and emotional ill-being, and whether basic psychological needs frustration mediates the relationship. Congruent with the hypotheses, the findings showed that supportive parenting style positively influences basic psychological needs satisfaction, which results in higher emotional well-being. In a similar vein, thwarting parenting style positively influences basic psychological needs frustration, resulting in higher emotional ill-being.

The findings are in line with Kocayoruk (2012); Ahmad et al. (2013), and Costa et al. (2019), reporting that supportive parenting predicts the psychological needs fulfillment and positive outcomes, while psychological needs frustration and negative outcomes are reflected from thwarting parental practices. Their research also found that psychological needs mediate the relationship between supportive parenting and positive outcomes, and the relationship between thwarting parenting and negative outcomes. Ryan and Deci (2017) found that thwarting parental behaviors hindered the need for competence and induced inferior feelings that make adolescents prone to subjective distress, negative feelings, and affection.

The key finding of this study supports the SDT claim that basic psychological needs represent nourishment necessary for well-being and that children’s frustration is likely to induce negative behaviors (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000). In SDT, supportive parenting could serve as a unique predictor for need satisfaction, while thwarting parenting would work to predict need frustration (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013; Costa et al., 2015).

Different from most previous studies, this study revealed that thwarting parenting style positively predicted the basic psychological needs satisfaction. The correlational result showed that parental coercion might be a contributing factor to this finding. Even though numerous evidence shows that controlling parenting has effects on children’s negative outcomes, some cross-cultural studies identified less negative or even non-existent effects of controlling parenting in Eastern Asian samples (e.g., Iyengar and Lepper, 1999). These findings might reflect the less pressuring and more favorable meaning of controlling parenting in East Asian culture (Park and Kim, 2004; Grusec, 2012). The case illustrated by Chao (1994) shows that Asian children are likely to view parenting control as a concern or engagement. On the contrary, such a parenting style will hold less positive meaning in an individualistic culture, as it is considered a mere channel of parents’ anger and rejection.

As parenting is heavily driven by culture (Bornstein, 2012), this finding accentuates that the culture of the West and the East differs. The former views coercion as a thwarting parenting style where parents shoulder responsibility for their children’s wrong doing (Senese et al., 2012). Parenting goals in the Western cultures characterize this conceptualization to educate children to become outspoken, self-reliant, capable, and self-determined (Rubin et al., 2008). In Eastern culture, on the other hand, parenting is often associated with high expectations and control from parents (Chao and Aque, 2009). This belief stems from the hierarchical structure that demands younger individuals respect and regards their elders highly. Indonesian parents also instill a similar value which requires children to submit to their parents’ guidance and hold any questions, particularly about religion and cultural issues.

This study strongly represents a comprehensive examination of parenting style, basiychological needs, well-being, and ill-being, using the SDT framework. The findings particularly add to a growing literature on the basic psychological need theory. However, the present findings might have a limitation as it uses correlational data that does not reflect cause and effect. To address this issue, future research should apply experimental or longitudinal methods. Furthermore, this study may reflect the findings in Indonesian adolescents. However, it might not reveal the specific family condition, which might differ among populations, as we didn’t collect the data related to the family background. To gain a deeper understanding of the topic, future research should take these variables into account.

The findings of this study have an important implication for future practice. It confirmed the significance of supportive parenting in the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs satisfaction, which eventually promotes adolescents’ well-being. Various interventions to provide knowledge and skills for parents to practice warmth, structure, and autonomy support are essential. Further research should be undertaken to explore the concept of thwarting parenting, especially coercion.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/698ja.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Padjadjaran. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

FA contributed to conception and design of the study. SF organized the database. WY performed the statistical analysis. FA and WY wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors wrote sections of the manuscript, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to thank Joeri K. Tijdink, MD, Ph.D. for his insight and involvement in the initial discussion of the manuscript.

Abidin, F. A., Joefiani, P., Koesma, R. E., and Siregar, J. R. (2019). Parental structure and autonomy support: keys to satisfy adolescent’s basic psychological needs. Opcio 35, 2899–2921.

Abidin, F. A., Joefiani, P., Koesma, R. E., Yudiana, W., and Siregar, J. R. (2021). The basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration scale: validation in indonesian adolescents. J. Legal Ethical Regul. Issues 24 Special Issue 1, 1–8.

Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., and Ntoumanis, N. (2008). Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal functioning of adult male and female sport participants: a test of basic needs theory. Motiv. Emot. 32, 189–199.

Ahmad, I., Vansteenkiste, M., and Soenens, B. (2013). The relations of Arab Jordanian adolescents’ perceived maternal parenting to teacher-rated adjustment and problems: the intervening role of perceived need satisfaction. Dev. Psychol. 49, 177–183. doi: 10.1037/a0027837

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Mouratidis, A., Katartzi, E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., and Vlachopoulos, S. (2018). Beware of your teaching style: a school-year long investigation of controlling teaching and student motivational experiences. Learn. Instr. 53, 50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.07.006

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., and Thøgersen-ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: the role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37, 1459–1473. doi: 10.1177/0146167211413125

Baumrind, D. (1991). “Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition,” in Advances in Family Research Series. Family Transitions, eds P. A. Cowan and E. M. Herington (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc), 111–163.

Baumrind, D. (2013). Is a pejorative view of power assertion in the socialization process justified? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 17, 420–427. doi: 10.1037/a0033480

Boone, L., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Kaap-Deeder, J. V., and Verstuy, J. (2014). Self-critical perfectionism and binge eating symptoms: a longitudinal test of the intervening role of psychological need frustration. J. Couns. Psychol. 61:363. doi: 10.1037/a0036418

Bornstein, M. H. (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting 12, 212–221. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.683359

Campbell, R., Tobback, E., Delesie, L., Vogelaers, D., Mariman, A., and Vansteenkiste, M. (2017). Basic psychological need experiences, fatigue, and sleep in individuals with unexplained chronic fatigue. Stress Health 33, 645–655. doi: 10.1002/smi.2751

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 65, 1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x

Chao, R. K., and Aque, C. (2009). Interpretations of parental control by Asian immigrant and European American youth. J. Fam. Psychol. 23, 342–354. doi: 10.1037/a0015828

Chen, Y. W., Bundy, A. C., Cordier, R., Chien, Y. L., and Einfeld, S. L. (2015b). Motivation for everyday social participation in cognitively able individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 11, 2699–2709. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S87844

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Kaap-Deeder, J. V., et al. (2015a). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 39, 216–236. doi: 10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Cordeiro, P., Paixão, P., Lens, W., Lacante, M., and Luyckx, K. (2016). The portuguese validation of the basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration scale: concurrent and longitudinal relations to well-being and ill-being. Psychol. Belg. 56, 193–209. doi: 10.5334/pb.252

Costa, S., Sireno, S., Larcan, R., and Cuzzocrea, F. (2019). The six dimensions of parenting and adolescent psychological adjustment: the mediating role of psychological needs. Scand. J. Psychol. 60, 128–137. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12507

Costa, S., Soenens, B., Gugliandolo, M. C., Cuzzocrea, F., and Larcan, R. (2015). He mediating role of experiences of need satisfaction in associations between parental psychological control and internalizing problems: a study among Italian college students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 1106–1116. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9919-2

Darling, N., and Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 113, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inquiry 11, 227–268.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., and Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: a cross-cultural study of self-determination. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 930–942. doi: 10.1177/0146167201278002

DeHaan, C. R., Hirai, T., and Ryan, R. M. (2016). Nussbaum’s capabilities and self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs: relating some fundamentals of human wellness. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 2037–2049.

Devi, L., and Uma, M. (2013). Parenting styles and emotional intelligence of adolescents. J. Res. ANGRAU 41, 68–72.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., won Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Research 97, 143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Flamm, E. S., and Grolnick, W. S. (2013). Adolescent adjustment in the context of life change: the supportive role of parental structure provision. J. Adolesc. 36, 899–912. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.006

Garcia, O. F., Fuentes, M. C., Gracia, E., Serra, E., and Garcia, F. (2020). Parenting warmth and strictness across three generations: parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:7487.

Gimenez-Serrano, S., Alcaide, M., Reyes, M., Zacarés, J. J., and Celdrán, M. (2022). Beyond parenting socialization years: the relationship between parenting dimensions and grandparenting functioning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084528

Gimenez-Serrano, S., Garcia, F., and Garcia, O. F. (2021). Parenting styles and its relations with personal and social adjustment beyond adolescence: is the current evidence enough? Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2021.1952863 [Epub ahead of print].

Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., and Petegem, S. V. (2015). Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 16, 26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.013

Hair, J. F. Jr., William, C. B., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis, 7th Edn. London: Pearson.

Holmbeck, G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study and pediatric psychology literatures. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol. 65, 599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599

Iyengar, S. S., and Lepper, M. R. (1999). Rethinking the value of choice: a cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 349–366. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.3.349

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., and Reeve, J. (2016). Why students become more engaged or more disengaged during the semester: a self-determination theory dual-process model. Learn. Instr. 43, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.002

Jang, H., Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., and Kim, A. (2009). Can self-determination theory explain what underlies the productive, satisfying learning experiences of collectivistically oriebted Korean students? J. Educ. Psychol. 101:644. doi: 10.1037/a0014241

Johnson, L. E., and Greenberg, M. T. (2013). Parenting and early adolescent internalizing: the importance of teasing apart anxiety and depressive symptoms. J. Early Adolesc. 33, 201–226. doi: 10.1177/0272431611435261

Joussemet, M., Landry, R., and Koestner, R. (2008). A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Can. Psychol. 49, 194–200. doi: 10.1037/a0012754

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., and Poulton, R. (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: development follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch. Gen Psychiatry 60:709. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709

King, K. A., Vidourek, R. A., Yockey, R. A., and Merianos, A. L. (2018). Impact of parenting behaviors on adolescent suicide based on age of adolescent. J. Child Fam. Stud. 27, 4083–4090. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1220-3

Kocayoruk, E. (2012). The perception of parents and well-being of adolescents: link with basic psychological need satisfaction. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 46, 3624–3628. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.117

Liga, F., Ingoglia, S., Cuzzocrea, F., Inguglia, C., Costa, S., Lo Coco, A., et al. (2020). The Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale: Construct and predictive validity in the Italian context. J. Pers. Assess. 102, 102–112. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1504053

Martinez, I., Garcia, F., Fuentes, M. C., Veiga, F., Garcia, O. F., Rodrigues, Y., et al. (2019). Researching parental socialization styles across three cultural contexts: scale ESPA29 Bi-Dimensional validity in Spain, Portugal, and Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:197. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16020197

Martinez-Escudero, J. A., Villarejo, O. F., Garcia, S., and Garcia, F. (2020). Parental socialization and its impact across the lifespan. Behav. Sci. 10:101. doi: 10.3390/bs10060101

Niemiec, C. P., Lynch, M. F., Vansteenkiste, M., Bernstein, J., Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2006). The antecedents and consequences of autonomous self-regulation for college: a self-determination theory perspective on socialization. J. Adolesc. 29, 761–775. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.11.009

Nishimura, T., and Suzuki, T. (2016). Basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration in Japan: controlling for the big five personality traits. Jap. Psychol. Res. 58, 320–331. doi: 10.1111/jpr.12131

Park, Y. S., and Kim, U. (2004). “Indigenous psychologies,” in Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology, ed. C. Spielberger (Oxford: Elsevier Academic Press), 263–269.

Pinquart, M. (2016). Associations of parenting styles and dimensions with academic achievement in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 475–493. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9338-y

Pinquart, M., and Kauser, R. (2018). Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? results from a meta-analysis. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 24, 75–100. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000149

Power, T. G. (2013). Parenting dimensions and styles: a brief history and recommendations for future research. Child. Obesity 9 1, s14–s21. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0034

Quested, E., and Duda, J. L. (2010). Exploring the social-environmental determinants of well- and ill-being in dancers: a test of basic needs theory. J. Sport and Exerc. Psychol. 32, 39–60. doi: 10.1123/jsep.32.139

Rodrigues, F., Hair, J. F. Jr., Neiva, H. P., Teixeira, D. S., Cid, L., and Monteiro, D. (2019). The Basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration scale in exercise (BPNSFS-E): validity, reliability, and gender invariance in Portuguese exercisers. Percept. Motor Skills 126, 949–972. doi: 10.1177/0031512519863188

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Statist. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rubin, K., Fredstrom, B., and Bowker, J. (2008). Future directions in. friendship in childhood and early adolescence. Soc. Dev. 17, 1085–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00445.x

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., and Grolnick, W. S. (1995). “Autonomy, relatedness, and the self: their relation to development and psychopathology,” in Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 1, eds D. Cicchetti and D. J. Cohen (New York: Wiley), 618–655. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070125

Saha, R., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., Malone, P. S., and Valois, R. F. (2014). Social coping and life satisfaction in adolescents. Soc. Indic. Res. 115, 241–252. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0217-3

Sahithya, B. R., Manohari, S. M., and Raman, V. (2019). Parenting styles and its impact on children – a cross cultural review with a focus on India. Mental Health Relig. Cult. 22, 357–383. doi: 10.1080/13674676.019.1594178

Sandoval-Obando, E., Alcaide, M., Salazar-Muñoz, M., Peña-Troncoso, S., Hernández-Mosqueira, C., and Gimenez-Serrano, S. (2022). Raising children in risk neighborhoods from Chile: examining the relationship between parenting stress and parental adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010045

Senese, V. P., Bornstein, M. H., Haynes, O. M., Rossi, G., and Venuti, P. (2012). A cross-cultural comparison of mothers’ beliefs about their parenting very young children. Infant Behav. Dev. 35, 479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.02.006

Shek, D. T. L., and Lin, L. (2014). Personal well-being and family quality of life of early adolescents in Hong Kong: do economic disadvantage and time matter? Soc. Indic. Res. 117, 795–809. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0399-3

Sheldon, K. M., and Bettencourt, B. A. (2002). Psychological need-satisfaction and subjective well-being within social groups. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 41, 25–38. doi: 10.1348/014466602165036

Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., and Reis, H. T. (1996). What makes for a good day? Competence and autonomy in the day and in the person. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 22, 1270–1279. doi: 10.1177/01461672962212007

Skinner, E., Johnson, S., and Snyder, T. (2005). Six dimensions of parenting: a motivational model. Parenting 5, 175–235. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0502_3

Soenens, B., Deci, E. L., and Vansteenkiste, M. (2017). “How parents contribute to children’s psychological health: the critical role of psychological need support,” in Development of Self-Determination Through the Life-Course, eds M. Wehmeyer, K. Shogren, T. Little, and S. Lopez (Dordrecht: Springer), 171–187. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-1042-6_13

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., and Beyers, W. (2019). “Parenting adolescents,” in Handbook of Parenting: Children and Parenting, ed. M. H. Bornstein (Oxfordshire: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 111–167. doi: 10.4324/9780429440847-4

Valle, M. D., Matos, L., Díaz, A., Pérez, M. V., and Vergara, J. (2018). Propiedades psicométricas Escala Satisfacción y Frustración Necesidades Psicológicas (ESFNPB) en Universitarios Chilenos. Propósitos Representaciones 6, 327–350.

Vansteenkiste, M., and Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 23, 263–280. doi: 10.1037/a0032359

White, R. M., Roosa, M. W., Weaver, S. R., and Nair, R. L. (2009). Cultural and contextual influences on parenting in Mexican American families. J. Marriage Fam. 71, 61–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00580.x

Wimsatt, A. R., Fite, P. J., Grassetti, S. N., and Rathert, J. L. (2013). Positive communication moderates the relationship between corporal punishment and child depressive symptoms. Child Adolesc. Mental Health 18, 225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00682

Keywords: parenting style, emotional well-being, adolescents, basic psychological need satisfaction, basic psychological need frustration

Citation: Abidin FA, Yudiana W and Fadilah SH (2022) Parenting Style and Emotional Well-Being Among Adolescents: The Role of Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Frustration. Front. Psychol. 13:901646. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.901646

Received: 22 March 2022; Accepted: 25 May 2022;

Published: 15 June 2022.

Edited by:

Luciana Karine de Souza, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, BrazilReviewed by:

Marta Alcaide, University of Valencia, SpainCopyright © 2022 Abidin, Yudiana and Fadilah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fitri Ariyanti Abidin, Zml0cmkuYXJpeWFudGkuYWJpZGluQHVucGFkLmFjLmlk

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.