- 1College of Health Studies Milutin Milankovic, Belgrade, Serbia

- 2Department in Cuprija, The Academy of Applied Preschool Teaching and Health Studies Krusevac, Cuprija, Serbia

- 3Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 4Department School of Applied Health Science Studies, Academy of Applied Studies Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia

- 5Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 6Department of Communication Skills, Ethics and Psychology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 8Department of Hygiene and Ecology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 9Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 10Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism in Vrnjacka Banja, University of Kragujevac, Vrnjacka Banja, Serbia

Background: The aims of our study are related to examining the relevance of teachers' attitudes toward the implementation of inclusive education. In addition, its subject is related to the implications on inclusive education policies, limitations of the existing study along with the recommendations for our future research endeavors.

Methods: The research is a cross-sectional study type. The sample included 64 primary school teachers in the lower grades of primary school (grades 1–4), selected by using simple random sampling, in three primary schools on the territory of Belgrade, Serbia in 2021 (26, 17, and 21 primary school teachers). The Questionnaire for Teachers, which was used as a research instrument, was taken from the Master's Thesis Studen Rajke, which was part of the project “Education for the Knowledge Society” at the Institute for Educational Research in Belgrade. Dependent variables measured in the study referred to the attitudes of primary school teachers toward inclusive education. Categorical variables are represented as frequencies and the Chi-square test was used to determine if a distribution of observed frequencies differed from the expected frequencies.

Results: One in three teachers (32.8%) thought that inclusion was useful for children with disabilities (29.7%), of them thought that schools did not have the conditions for inclusive education, whereas one in four teachers (25.0%) believed that inclusion was not good. No statistically significant differences were found in the attitudes of professors, when observed in terms of their gender, age and length of service.

Conclusion: Investing more resources and time in developing and implementing special education policies can promote successful inclusive education.

Introduction

Inclusive education means quality education for all students, respecting their diversity in terms of educational needs (UNESCO, 2009). The inclusion of students with disabilities in typical schools with their peers is part of the global human rights movement, which refers to the possibility that students with disabilities can fully participate in all activities that make up modern society (Rajšli-Tokoš, 2020).

The history of inclusive education dates back since the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality (Salamanka, Spain, 7–10 June 1944), which enabled substantial progress, simultaneously opening room for improvement and introducing a more dynamic approach of schools toward all children, irregardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, language or other state of mind, as well as the educational system oriented toward the students with various educational needs, by means of which the inclusive education platform was eventually established (United Nations Educational, 1994). The necessity of implementing inclusive education was confirmed at the UNESCO World Conference on Special Needs Education (UNESCO, 2003). The principles of inclusive education were presented for the second time at the World Education Forum meeting in Dakar in the year of 2000 (The Dakar Framework for Action, 2000), and finally, they were confirmed in the Millennium Declaration (Bhaskara, 2003). A few years later, at the Second European Ministerial Conference, which took place in Malaga, Spain, the Council of Europe (Council of Europe, 2003) declared that education is the fundamental means enabling children with disabilities to successfully integrate into the community and it established the legal framework needed for including special needs children in regular schools by providing necessary support and thus promoting the ways in which their education could be improved (Council of Europe, 2006).

There is a large number of studies which indicated that inclusive education has its own advantages as regards cognitive, social and affective development of students. They also show that inclusive education, compared to segregated education, offers more opportunities to develop social, emotional, and behavioral skills not only of children who need additional support, but also of children of typical development in terms of their enhancing the level of understanding and acceptance of diversity (Magyar et al., 2020; Molina Roldán et al., 2021; van Kessel et al., 2021). The results of various research studies have shown that students without difficulties have positive attitudes, positive beliefs, and express readiness when it comes to accepting students with disabilities along with having a positive attitude toward joint teaching with them, which is a very important factor for successful inclusion (Radisavljevic-Janic et al., 2018; Alnahdi and Schwab, 2021).

Additionally, it was confirmed that teachers were the key actors in the implementation of inclusive education and that their positive attitudes played a significant role in the successful administration of this educational transformation (De Boer et al., 2011). However, whereas the effects of teachers' attitudes toward the application of inclusion policies have been widely recognized, there is not a significant number of studies examining the factors shaping such attitudes.

Only a few studies revealed the effects of factors (age, gender, length of service (years), training, experience with inclusive education and type of student disability) on the attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002; Alghazo et al., 2003; Forlin et al., 2009; Woodcock, 2013).

In this context, our study's primary goal is to examine attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education, sociodemographic factors affecting such attitudes along with the factors stated by teachers as being alleviating/aggravating factors for the inclusion process in education, which could be perceived as excellent basis for creating specialized programs and measures for the purpose of enhancing the inclusive education.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The research is a cross-sectional study type.

The Study Participants

The sample included 64 primary school teachers in the lower grades of primary school (grades 1–4), employed in three primary schools in the territory of Belgrade, Serbia, who were selected by using simple random sampling (26, 17, and 21 primary school teachers of both gender, with the average age of 43.1 ± 8.4 years). Data collection was realized in the second term of school year 2020/21, by means of a teacher survey. The school principals gave their consent to administering such teacher surveys or questionnaires.

The Procedure for Data Acquisition

Teacher survey questionnaires were administered after delivering detailed written instructions which had been distributed in schools. Teacher survey questionnaires were voluntarily completed, and self-administered with respondents filling in their own answers. Before the start of the research, the respondents were acquainted with the goal and procedure of the research and gave their written consent to participate in the study. For the purpose of ensuring objectiveness of the results and capturing accurate data, during the procedure for data acquisition, researchers were leading teachers during the process of filling in their own answers in accordance with the methodically anticipated protocol. Before underlying the aims of the research and delivering instructions for the purpose of filling in the questionnaires given, the respondents were told that the data obtained in such a manner were going to be used for scientific purposes only, that all the answers were highly classified and that the analysis of data was going to be performed collectively, not individually. After placing an emphasis on the fact that filling in the questionnaires was anonymous, the researchers asked the respondents to be honest, to give answers to the questions independently, without sharing any mutual comments or chatting with other respondents. The respondents were given the manual for filling in the questions included in the questionnaire. The time expected to complete the questionnaire was 20 min ± several minutes.

Instruments/Measures

The Questionnaire for Teachers, which was used as a research instrument, was taken from the Master's Thesis Studen Rajke (Studen, 2008), which was part of the project “Education for the Knowledge Society” at the Institute for Educational Research in Belgrade. The Teachers' Questionnaire examines the level of willingness that the primary school teachers have in order to accept children with disabilities, their experiences in working with children with disabilities, and their suggestions that would lead to more successful outcomes for children with disabilities. The questionnaire also contains a five-point scale consisting of 22 statements related to the importance of certain psychological and pedagogical measures undertaken for the purpose of successful implementation of inclusive education and factors that may be aggravating for the inclusive process. The independent variables examined in the research are sociodemographic characteristics of primary school teachers (such as gender, age, length of service). Dependent variables measured in the study referred to the attitudes of primary school teachers toward inclusive education (their readiness for inclusion, assessment of conditions for inclusion, difficulties, and benefits of inclusive education, providing support to children and parents involved in the inclusive education, the importance of psychological and pedagogical measures undertaken for the purpose of successful implementation of inclusive teaching, assessment of factors that may be aggravating for the inclusive process). The reliability of The Questionnaire for teachers in a sample of adult respondents was 0.86.

Statistical Data Analysis

Statistical data processing was performed using SPSS software package, version 18.0. The results of the research are presented in Tables 1–4. Categorical variables are represented as frequencies and the Chi-square test was used to determine if a distribution of observed frequencies differed from the expected frequencies. A probability of <5% was considered statistically significant.

Table 1. Sociodemografic characteristics of primary school teachers and attitudes toward inclusive education.

Results

As the figures indicate, males accounted for 31.3% of the total number of primary school teachers, whereas females accounted for 68.7%. The average age of respondents was 43.1 ± 8.4 years. The majority of respondents were aged between 40 and 49 years (39.4%), whereas the least number of respondents was in the group with an age of more than 60 years (3.9%).

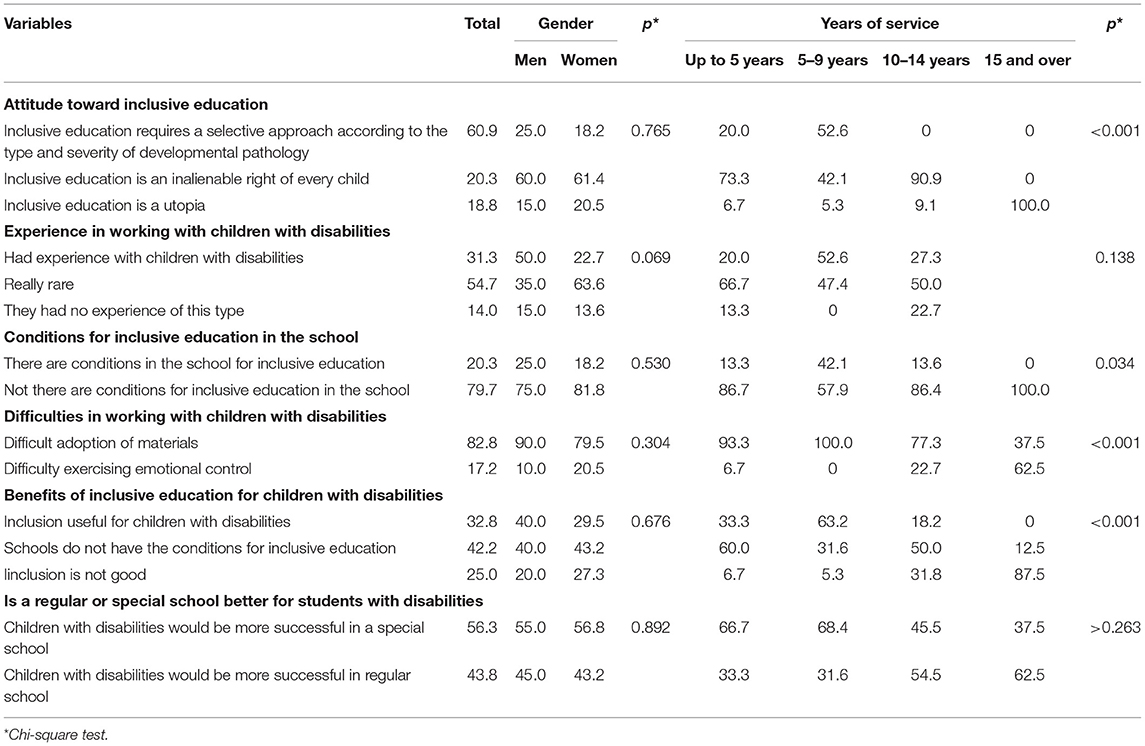

A total of 23.4% of professors had a length of service of up to 5 years, 29.7% had a length of service from 5 to 9 years, a third had a length of service from 10 to 14 years, and 12.5% had a length of service of over 15 years. The largest percentage of them, 60.9%, believe that inclusive education requires a selective approach according to the type and severity of developmental pathology, 20.3% of them believe that it is an inalienable right of every child, whereas 18.8% believe that it is a utopia. Almost a third of professors (31.3%) stated that in their previous pedagogical work, they had experience with children with disabilities, while slightly more than half of them (54.7%) rarely had this particular experience.

Only one in five primary school teachers (20.3%) stated positively that there were conditions in the school for the inclusion of children with disabilities. As the most common problems they had in the educational work with this category of students, the teachers of primary education stated the difficult adoption of the material (82.8%) and the realization of emotional control by 17.2%.

One in three teachers (32.8%) thought that inclusion was useful for children with disabilities (29.7%), of them thought that schools did not have the conditions for inclusive education, while one in four teachers (25.0%) believed that inclusion was not good. Every second professor (56.3%) thought that children with disabilities would be more successful in mastering the material in a special school, while 43.8% of them thought that they would be more successful in a regular school, but if there were schools that corresponded to material and organizational standards of the most developed countries. Observed by gender, the attitudes of teachers did not show a statistically significant difference, while according to work experience there are differences when it comes to attitudes toward inclusive education, to difficulties in working with children with disabilities and to the benefits of inclusive education (Table 1).

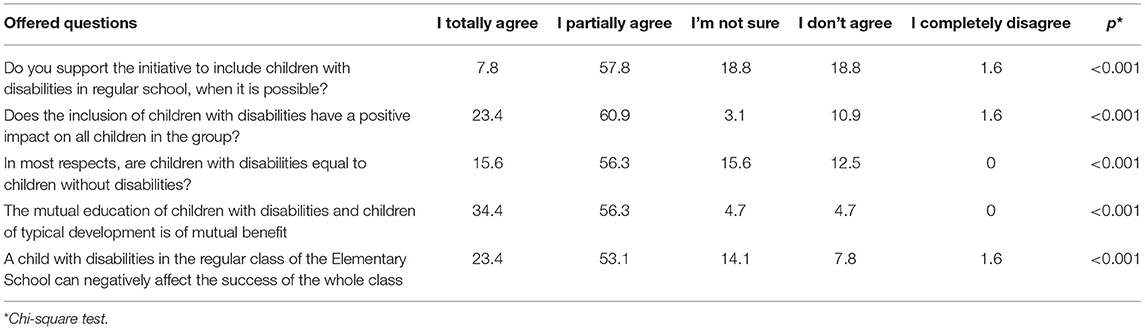

Despite positive attitudes toward inclusive education, teachers' attitudes were only partially positive when it came to attitudes toward children with disabilities (Table 2). Observed attitudes showed a statistically significant difference.

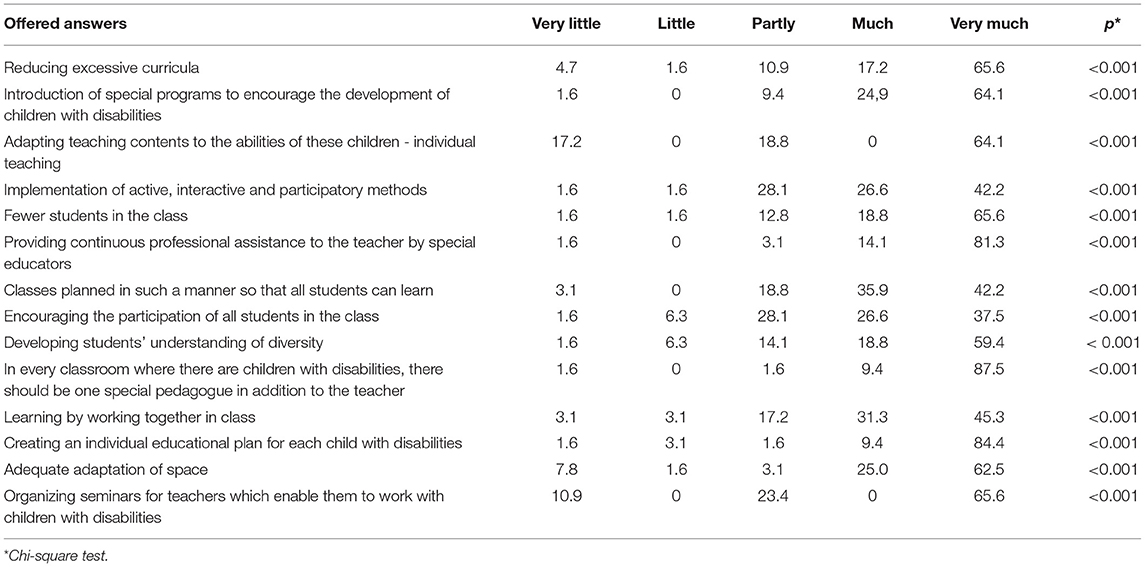

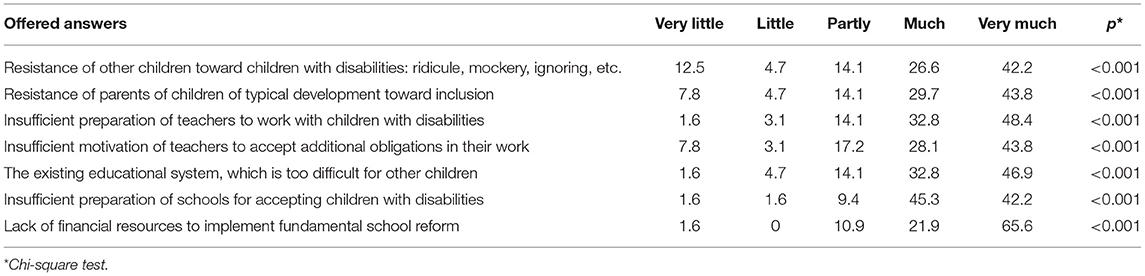

The professors also pointed out which factors would make it easier for a child with developmental disabilities to follow regular classes (Table 3) complete with the factors that most often complicated the inclusion process in practice (Table 4). Observed factors showed a statistically significant difference.

Discussion

The significance of implementing inclusion in the education system complete with the association of early inclusive education with educational outcomes of children with disabilities is evident (Samadi and McConkey, 2018). Numerous countries have made considerable progress in this particular area, by means of legal regulation which regulates the provision of services to children with disabilities (Magyar et al., 2020). However, data obtained so far indicate that in some of the countries children with disabilities still attend special schools and are often excluded from the educational system. In order to enhance the inclusion system, local and national politics have to be precisely conceptualized with clearly defined objectives, whereas the school environment has to provide adequate support for children with disabilities (Werner et al., 2021).

Teachers are recognized as the key actors and their attitude toward inclusion is of high relevance for the successful implementation of inclusive education strategies, but the factors influencing these attitudes have been given insufficient attention in the studies conducted in our territories. Despite the fact that substantial action has already been taken in relation to this particular area, the implementation of inclusive education in practice has encountered numerous difficulties. It is our teachers who place an emphasis on the fact that inclusive education is an inalienable right of every child, they accentuate its usefulness in terms of understanding individual differences among children, but they also point out that regular schools have no conditions or capacities to carry out inclusive education.

Additionally, other research studies demonstrate that teachers justify the concept of inclusive education in terms of children's rights (Kayama, 2010; Okyere et al., 2019), but they also express their concern regarding numerous challenges they are currently juggling in their daily work with children with disabilities. The lack of professional competencies along with the lack of adequate conditions aimed at developing successful inclusive educational practice are the main reasons given by teachers which present a major hindrance to the successful implementation of inclusive education (Savic and Prosic-Santovac, 2017), which is indicated by our research findings.

Interestingly, the results obtained from several studies show that certain gender specific patterns are recognizable when it comes to attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education, with female teachers showing a more positive attitude toward inclusive education, whereas other studies indicated no gender specific differences in forming the aforementioned attitudes (Alghazo et al., 2003; Woodcock, 2013).

Concerning the age relevance, some studies demonstrate that the age of teachers has no significant effect on forming their attitudes toward inclusive education (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002), whereas other studies show that older teachers have more negative attitudes toward inclusion (De Boer et al., 2011). In addition, they indicate that inclusive education training programs have a positive effect on attitudes of younger teachers, which is probably due to the fact that older teachers have rarely attended courses on inclusive teaching or have not been provided with relevant in-service training at all (Forlin et al., 2009). Our research results show that sex have no significant impact on their attitudes toward inclusive education.

Another study outlined that the lack of teachers' self-esteem regarding teaching students with disabilities was associated with their forming negative attitudes toward inclusion (Avramidis et al., 2020), whereas the study which took into consideration the factors such as the type and size of the school building and its classrooms complete with the characteristics of students such as gender or whether the child received support in the academic or non-academic areas of school education—indicated that the aforementioned factors had no significant effects on the attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education (Vaz et al., 2015).

Our study showed that teachers reported that the inclusion process could be more easily facilitated by the classroom adaptations accompanied by a class size reduction. However, we did not take into consideration the characteristics of students with disabilities in terms of their gender and level of school achievement in the inclusive environment, which may be the subject of our future research.

Taking into account the fact that the teachers included in our study reported insufficient curriculum planning for teaching children with disabilities, it is more than evident how necessary it is to introduce special curriculum programs for inclusion education. They emphasize that reforms of excessive coursework and curricula should be delivered, along with the adaptation of teaching contents to the abilities of these children and the application of active, interactive and participatory teaching methods. In addition, they indicated the necessity of continuous provision of professional assistance to the teacher by special educators/experts, such as defectologists and social pedagogues.

A large number of research evidence speak out in favor of the fact that it was the provision of support to teachers that positively influenced their attitudes toward inclusion, indicating that after the completion of inclusion training programs—the level of positive attitudes of teachers toward inclusion was significantly raised. Additionally, they emphasized that various types of social support (such as informational, instrumental or emotional support) may be provided by various actors (colleagues, supervisors, etc.) (Desombre et al., 2021; Hassanein et al., Hassanein et al.).

Nevertheless, the findings of other studies revealed that in the case if children or adults with disabilities were among teachers' family members or their circles of friends, teachers were more open to embracing the concept of inclusion, and that the very knowledge they possessed on the specific disability of their students had a positive impact on their attitudes toward inclusion (Vaz et al., 2015).

Teachers have to actively participate in the process of inclusion implementation and they have to be ready to handle all the new challenges presented at each level of the education system. They primarily need adequate support, cooperation, provision of professional experience and specific preparation of individual class sessions for the purpose of achieving as high-quality level of inclusive education as possible. Multidisciplinary work, professional development, attitudes and perception of teachers along with adequate cooperation with their students' family members and provision of positive support to students—play a significant role in inclusive education (Rojo-Ramos et al., 2021).

The inclusion of special needs children presents one of a kind challenge for the societies worldwide. Therefore, we need to take concrete actions and establish organizations of such a kind in all societies for the purpose of implementing adequate and high-quality inclusive education for this group of children specifically. Educational institutions should transform and adjust their educational programs in order to respond to this new growing challenge, whereas teachers should use their positive attitudes toward inclusive education to assume the leading role (Tétreault et al., 2014).

The advantages of our particular study are related to providing insight into the factors perceived as positively or negatively affecting the formation of positive attitudes toward inclusive education. It can contribute to creating measures, the focus of which will be on the enhancement and development of positive attitudes of teachers toward inclusive education. It is more than clear that there is a number of mutually linked factors and that each of the factors should be given considerable attention and be subjected to a detailed analysis. However, our study encountered certain limitations of its own. Namely, the sample included the teachers from urban areas only, whereas the teachers from neighboring suburban and rural areas were not included in the study. Additionally, the following factors were not included in the study: general attitudes of teachers toward people with disabilities in the society as a whole, and possible culturological differences between them. Furthermore, we did not take into consideration the degree of their concern or stress caused by the actual physical contact with children with disabilities, nor did we consider the financial fees for their work. We did not consider the attitudes of students and their parents toward inclusive education, investigations in this particular area will be a significant component of the future research studies, especially because of the fact that the teachers included in our study had already emphasized that the following factors complicated the process of inclusion in education: resistance of other children toward children with disabilities and resistance of parents of children of typical development toward inclusion. All the aforementioned facts indicated the necessity and recommendations for our future research directions. Due to our current study, numerous questions have been raised which are going to be part of our future research endeavors.

Conclusions

In order to guarantee the smooth inclusion of children with disabilities, various studies of this type are needed to identify the factors that hinder inclusive education in order to formulate strategies that can improve the inclusion of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the education system. Developing policies that support such strategies could improve this implementation. Experts specialized in different fields should gather in order to identify practical solutions to the challenges of creating an inclusive environment for children with special needs. Investing more resources and time in developing and implementing special education policies can promote successful inclusive education. The implementation of inclusive education is a very complex process and if it is considered from different perspectives, we could create a possibility of using the results of all the research conducted so far as well as all the future research results as the basis for initiating national programs and strategies on inclusive education. Our study represents only the starting point of our aspirations to render the inclusive education process in our territories as high-quality and comprehensive as possible.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JR conceptualized the research. JR, TK, SRade, and MM conducted the literature review, a preliminary analysis of the data, and a first draft of the manuscript. SRado and MS revised the data analysis. KP, MD, SC, BR, and OD revised the manuscript and provided feedback and corrections. JN, IS, KJ, and JR revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alghazo, E. M., Dodeen, H., and Algaryouti, I. A. (2003). Attitudes of pre-service teachers towards persons with disabilities: predictions for the success of inclusion. Coll. Stud. J. 37, 515–22.

Alnahdi, G. H., and Schwab, S. (2021). Special education major or attitudes to predict teachers' self-efficacy for teaching in inclusive education. Front. Psychol. 12, 680909. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680909

Avramidis, E., Bayliss, P., and Burden, R. (2020). A survey into mainstream teachers' attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school in one local education authority. Educ. Psychol. 20, 191–211. doi: 10.1080/713663717

Avramidis, E., and Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers' attitudes towards integration/inclusion: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 7, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/08856250210129056

Council of Europe (2003). Council of Europe; Strasbourg: 2003. Malaga Ministerial Declaration on People with Disabilities: Progressing towards Full Participation as Citizens.

Council of Europe (2006). Council of Europe; Strasbourg: 2006. Action Plan to Promote the Rights and Full Participation of People with Disabilities in Society: Improving the Quality of Life of People with Disabilities in Europe. Council of Europe.

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers' attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 15, 331–353. doi: 10.1080/13603110903030089

Desombre, C., Delaval, M., and Jury, M. (2021). Influence of social support on teachers' attitudes toward inclusive education. Front. Psychol. 12, 736535. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.736535

Forlin, C., Loreman, T., Sharma, U., and Earle, C. (2009). Demographic differences in changing pre-service teachers' attitudes, sentiments and concerns about inclusive education. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 13, 195–209. doi: 10.1080/13603110701365356

Hassanein, E. E. A., Alshaboul, Y. M., and Ibrahim, S. (2021). The impact of teacher preparation on preservice teachers' attitudes toward inclusive education in Qatar. Heliyon 7:e07925. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07925

Kayama, M. (2010) Parental experiences of children's disabilities and special education in the United States and Japan: implications for school social work. Soc Work 55, 117–25. 10.1093/sw/55.2.117.

Magyar, A., Krausz, A., Kapás, I. D., and Habók, A. (2020). Exploring Hungarian teachers' perceptions of inclusive education of SEN students. Heliyon 6:e03851. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03851

Molina Roldán, S., Marauri, J., Aubert, A., and Flecha, R. (2021). How inclusive interactive learning environments benefit students without special needs. Front. Psychol. 12, 661427. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661427

Okyere, C., Aldersey, H. M., Lysaght, R., and Sulaiman, S. K. (2019). Implementation of inclusive education for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in African countries: a scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 41, 2578–2595. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1465132

Radisavljevic-Janic, S. V., Bubanja, I. R., Lazarevic, B. J., Lazarević, D. A., and Milanović, I. T. (2018). Attitudes of primary school students towards inclusion in physical education classes. Teach. Educ. 67, 235–248. doi: 10.5937/nasvas1802235R

Rajšli-Tokoš, E. (2020). Education of children with disabilities. Norma 25, 31–42. doi: 10.5937/norma2001031R

Rojo-Ramos, J., Manzano-Redondo, F., Barrios-Fernandez, S., Garcia-Gordillo, M. A., and Adsuar, J. C. (2021). A descriptive study of specialist and non-specialist teachers' preparation towards educational inclusion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18:7428. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147428

Samadi, S. A., and McConkey, R. (2018). Perspectives on inclusive education of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities in Iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15, 2307. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102307

Savic, V. M., and Prosic-Santovac, D. M. (2017). English language teachers' attitudes towards inclusive education. Innovat. Teach. 30, 141–57. doi: 10.5937/inovacije1702141S

Studen, R. (2008). Characteristics of Inclusive Teaching and Readiness of Primary School Teachers and Students to Accept Children With Special Needs. Master's thesis, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade, Belgrade.

Tétreault, S., Freeman, A., Carrière, M., Beaupré, P., Gascon, H., and Marier Deschênes, P. (2014). Understanding the parents of children with special needs: collaboration between health, social and education networks. Child Care Health Dev. 40, 825–32. doi: 10.1111/cch.12105

The Dakar Framework for Action (2000). Education for All: Meeting Our Collective Commitments. Dakar, Senegal. Available online at: http://www.undp.org.lb/programme/governance/institutionbuilding/basiceducation/docs/dakar.pdf

UNESCO (2003). Overcoming Exclusion Through Inclusive Approaches in Education. A Challenge and a Vision. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organisation Ministry of Education Science Spain. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special-Needs Education (Adopted by the World Conference on Special-Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, 7-12 June 1994). Available online at: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/salamanca-statement-and-framework.pdf

van Kessel, R., Hrzic, R., Cassidy, S., Brayne, C., Baron-Cohen, S., Czabanowska, K., et al. (2021). Inclusive education in the European Union: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis of education policy for autism. Soc. Work Public Health 36, 286–299. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2021.1877590

Vaz, S., Wilson, N., Falkmer, M., Sim, A., Scott, M., Cordier, R., and Falkmer, T. (2015). Factors associated with primary school teachers' attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities. PLoS ONE 10, e0137002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137002

Werner, S., Gumpel, T. P., Koller, J., Wiesenthal, V., and Weintraub, N. (2021). Can self-efficacy mediate between knowledge of policy, school support and teacher attitudes towards inclusive education? PLoS ONE 16, e0257657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257657

Keywords: inclusive education, primary school teachers, attitudes, children with disabilities, quality and education

Citation: Radojlovic J, Kilibarda T, Radevic S, Maricic M, Parezanovic Ilic K, Djordjic M, Colovic S, Radmanovic B, Sekulic M, Djordjevic O, Niciforovic J, Simic Vukomanovic I, Janicijevic K and Radovanovic S (2022) Attitudes of Primary School Teachers Toward Inclusive Education. Front. Psychol. 13:891930. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.891930

Received: 08 March 2022; Accepted: 13 April 2022;

Published: 06 May 2022.

Edited by:

Mirna Nel, North-West University, South AfricaReviewed by:

Nemanja Rancic, Military Medical Academy, SerbiaMilena Vasic, Dr. Milan Jovanovic Batut Institute of Public Health of Serbia, Serbia

Copyright © 2022 Radojlovic, Kilibarda, Radevic, Maricic, Parezanovic Ilic, Djordjic, Colovic, Radmanovic, Sekulic, Djordjevic, Niciforovic, Simic Vukomanovic, Janicijevic and Radovanovic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jasmina Radojlovic, cGVkamEyMDAzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Jasmina Radojlovic

Jasmina Radojlovic Tatjana Kilibarda2

Tatjana Kilibarda2 Svetlana Radevic

Svetlana Radevic Milena Maricic

Milena Maricic Milan Djordjic

Milan Djordjic Sofija Colovic

Sofija Colovic Branimir Radmanovic

Branimir Radmanovic Marija Sekulic

Marija Sekulic Katarina Janicijevic

Katarina Janicijevic Snezana Radovanovic

Snezana Radovanovic