95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 04 July 2022

Sec. Positive Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879132

This article is part of the Research Topic Spirituality and Positive Psychology View all 9 articles

The study investigates the unexplored link between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing using data from a field survey of 568 rural residents from poor areas in China. This study focuses on exploring the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status, hope, sense of control, and adult subjective wellbeing using a structural equation model. Results indicated that hope and sense of control mediated the links between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing, revealing that hope and sense of control may buffer the negative impacts of childhood poverty experiences on subjective wellbeing. The findings provide new insights into the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing and expand the literature on key factors in adult subjective wellbeing.

An increasingly large body of study in social psychology revealed that childhood poverty is prospectively linked to adult outcomes including attainment-related outcomes (adult earnings and work hours) (Duncan et al., 2010, 2011), health outcomes (physical morbidity and mortality, psychological wellbeing) (Claussen, 2003; Howell and Howell, 2008; Cohen et al., 2010; Evans, 2016; Caria and Falco, 2018). Previous studies emphasized the impacts of childhood poverty on adult outcomes. However, it may be more important and valuable to tackle the issue that how to intervene to reduce the negative impacts of childhood poverty experiences on adult outcomes (e.g., subjective wellbeing). Particularly, how to weaken the negative impacts of lower childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing? One key to answer this question is finding more protective factors that may help ward off the negative impacts of lower childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing. Disappointedly, we still known little about the influence mechanism of childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing.

Hope is a positive psychological factor affecting subjective wellbeing (Diener and Biswas-Diener, 2002; Dittmar et al., 2014). Hope positively predicted subjective wellbeing (Cotton Bronk et al., 2009; Sariçam, 2015; Satici et al., 2020). Indeed, previous studies have highlighted the mediating role of hope (Cotton Bronk et al., 2009; Satici et al., 2020). For example, Chitchai et al. (2020) confirmed that hope for money mediated the relationship between socioeconomic status and happiness. Adult hope was based on the development of children’s brain and cognition (Glewwe et al., 2017), which is influenced by childhood socioeconomic status (Farah et al., 2006; Hair et al., 2015). Does childhood socioeconomic status affect adult subjective wellbeing through the mediating role of hope?

Sense of control is another potential mediating factor related to the relationship between childhood experiences and adult subjective wellbeing. Adult sense of control was closely related to the social class where they grew up (Kraus et al., 2012). Studies have emphasized the mediating role of sense of control in the relationship between discrimination experience and subjective wellbeing (Moradi and Hasan, 2004; Jang et al., 2008). And lower childhood socioeconomic status probably caused higher risks of discrimination experiences (Lang, 2011; Fuller-Rowell et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2018). The perceived experiences of prejudice and discrimination negatively affected their overall sense of control (Ruggiero and Taylor, 1995; Branscombe and Ellemers, 1998).

Therefore, this study focused on the mediating mechanism of childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing, aiming to explore the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status, hope, sense of control, and adult subjective wellbeing. Besides, we expected that hope and sense of control, as positive psychological quality, may help defend against the negative impacts of lower childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing. The results of this study may explain how childhood socioeconomic status affects adult subjective wellbeing from a psychological perspective. And the findings provided new empirical evidences and solutions for finding more mediating variables and reducing the negative impacts of childhood poverty experiences on adult subjective wellbeing.

To tackle this issue, we surveyed the rural residents in Jianshi County. Jianshi County, a key area of poverty intervention, is a typical poverty-stricken county in China. Over the long term, the mountainous area, poor transportation and poor water quality have resulted in a considerable number of poor people. In order to survive, many families become migrant workers for income, resulting in many left-behind children raised by grandparents or mother. According to a survey, there were 875 left-behind children among 1,917 children, and the left-behind rate reached 45.64% (Jv et al., 2015). Rural left-behind children with insufficient parents’ concern are often accompanied by risks of depression, perceived discrimination, parenting style, single-parent families (Wen and Lin, 2011; He et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019). However, many adults in Jianshi County have experiences of childhood poverty and left-behind children.

The paper is structured as follows. Section “Literature Review and Theorization of Hypotheses” briefly reviews previous studies on the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status, hope, sense of control, and subjective wellbeing. Section “Aims and Hypotheses” introduces our hypotheses. The data and methods we used in the analysis are presented in Section “Data and Methodology.” Section “Results” presents the results of data analysis and reveals the relationships among the targeted variables. Section “Discussion and Conclusion” completes the paper with the conclusion and discussion.

Lower childhood socioeconomic status is an important indicator of childhood poverty. Several studies have confirmed that childhood poverty negatively affects adult subjective wellbeing (Oshio et al., 2009). Childhood poverty suggested higher risk of childhood adversity (Frederick and Goddard, 2007; Hughes and Tucker, 2018). Studies have demonstrated that childhood adversity experiences had substantial negative impacts on adult subjective wellbeing (Oshio et al., 2013). Lee et al. (2017) also found that childhood adversities were associated with poor adult mental health outcomes. Mwachofi et al. (2020) confirmed that adults with adverse childhood experiences including parents quarreling and beating each other during childhood are more likely to fall into depression and lower subjective wellbeing. In addition, Evidence suggested that early childhood poverty had detrimental impacts on adult education, career opportunities, earnings and work hours (Cohen et al., 2010; Duncan et al., 2010, 2011; Duncan and Magnuson, 2013). And higher social class (household income) was associated with greater happiness (Piff and Moskowitz, 2018). Income (Ferrer-i-Carbonell, 2005; Clark et al., 2008) and education (Cuñado and de Gracia, 2011; Kristoffersen, 2018; Tan et al., 2020) positively affected adult subjective wellbeing. Both Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2005) and Kristoffersen (2018) used an eleven-point numeric scale between 0 and 10 to measure subjective wellbeing (Cantril, 1965). Therefore, the first hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1c. Childhood socioeconomic status positively affects adult subjective wellbeing.

Hope is a cognitive set and is defined as the agency and pathways to achieve desired goals (Snyder, 1995; Snyder et al., 2005). Hope represents an individual’s positive expectation for the future. Higher hope means that an individual has stronger desires to pursue future goals and a greater belief in their capacity to achieve them (Snyder et al., 1991, 1996). It is also a positive cognitive state or kind of coping strategy where one believes that things are going in the right direction and something is worth working or fighting for Havel (1990) and Donaldson et al. (2014). Normally, higher hope can lead to better outcomes in academics, athletics, physical health, mental health, and emotional adjustment (Snyder, 2002). Shorey et al. (2003) revealed that hope was closely related to adult mental health, and people with higher hope had less depression, less anxiety. Several studies found that hope positively predicted subjective wellbeing, although different scales were used to measure subjective wellbeing (Cotton Bronk et al., 2009; Sariçam, 2015; Satici et al., 2020). Cotton Bronk et al. (2009) used the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) to assess the global cognitive judgments of satisfaction with one’s life. Sariçam (2015) and Satici et al. (2020) assessed subjective wellbeing by using the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999). Specially, Chitchai et al. (2020) confirmed that hope for money positively affected happiness which was assessed with overall appreciation of one’s life as a whole (Veenhoven, 2012). Sometimes, hope can be seen as a kind of psychological protective factor associated with difficult conditions. Even under challenging life conditions, individuals with high hope have the strength to find alternative solutions and succeed (Satici et al., 2020). Therefore, the hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Hope positively affects adult subjective wellbeing.

Subjective wellbeing is an important positive aspect of mental health. A series of studies supported that sense of control is closely linked to mental health (Lachman and Weaver, 1998; Wolinsky et al., 2003; Moradi and Hasan, 2004; Kiecolt et al., 2009; Klama and Egan, 2011). Sense of control was defined as perceptions and beliefs about the ability to change the external environment and the future (Rodin, 1986; Burger, 1989). Lachman and Weaver (1998) found that greater sense of control was associated with higher life satisfaction and lower levels of depression. Empirical research by Moradi and Hasan (2004) confirmed that sense of control positively affected self-esteem and negatively affected psychological distress. According to Kiecolt et al. (2009), sense of control negatively affected psychological distress and any mental disorder, suggesting that sense of control tended to be monotonically related to positive mental health. Similarly, sense of control negatively affected anxiety and depression (Klama and Egan, 2011). Furthermore, losing control is one of the greatest fears of mankind (Astin and Shapiro, 1997). As an important factor affecting the life status of people throughout their lifespan (Rodin, 1986; Mirowsky, 1995), Greene and Britton (2015) found that sense of control positively predicted subjective wellbeing assessed by Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999). Therefore, the hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 3. Sense of control positively affects adult subjective wellbeing.

A few studies have demonstrated that adult hope was closely related to childhood hope (Kraftl, 2008; Bruner, 2017). Childhood hope can help individuals cope with childhood adversity (Munoz et al., 2020) and grow into adults with positive, optimistic character traits and hope for the future. Especially in poor families, it was crucial to build hope for children in early childhood stages (Glewwe et al., 2017). Meanwhile, childhood poverty inhibited the healthy development of children’s brain and cognitive including childhood hope (Pautler and Lewko, 1987; Farah et al., 2006; Hair et al., 2015), causing less hope during adulthood. In addition, Shorey et al. (2003) pointed out that adult hope was influenced by parenting styles directly and indirectly. Parenting styles positively affected adult hope and adults who grew up under the more positive and tolerant parenting styles (such as democracy) had higher hope (Kashdan et al., 2002). However, there existed many differences in parenting styles between poor and non-poor families (Magnuson and Duncan, 2002; Laplaca and Corlyon, 2015). Some studies found that lower childhood socioeconomic status was linked to negative parenting styles (Middlemiss, 2003; Hughes et al., 2005; Kaiser et al., 2017). Childhood family income and parental knowledge reflected by childhood socioeconomic status affected parenting styles (Goodman, 2007; September et al., 2015; Dix and Moed, 2019). Parents with less parenting knowledge adopted negative and extreme parenting styles including domineering and doting (Parks and Smeriglio, 1986; Shumow et al., 1998; Winter et al., 2011). This is not conducive to children’s psychological and cognitive development (Kaiser et al., 2017), leading to children with negative temperaments (Padilla and Ryan, 2019). Besides, Lower childhood socioeconomic status was detrimental to children development (Seccombe, 2000), predisposing them to significant increases in adverse childhood experiences (Slack et al., 2004; Steele et al., 2016). Simultaneously, Allender (2014) confirmed that adverse childhood experiences affect adult hope directly. Thus, the hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1a. Childhood socioeconomic status positively affects adult hope.

Childhood socioeconomic status represents the social class in which an individual grows up. The research by Kraus et al. (2012) argued that individuals who grew up in high social classes had significantly higher sense of control than those grew up in lower social classes, revealing that adult sense of control was significantly affected by childhood socioeconomic status. A few studies suggested that poverty was strongly associated with perceived discrimination (Lang, 2011; Fuller-Rowell et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2018). A series of studies confirmed prejudice and discrimination experiences always accompanied by childhood poverty negatively affected sense of control (Ruggiero and Taylor, 1995; Branscombe and Ellemers, 1998; Moradi and Hasan, 2004; Jang et al., 2008). Conversely, a warm and safe childhood experience helped promote one’s sense of control (Greene and Britton, 2015). Moreover, lower childhood socioeconomic status directly inhibited the healthy development of children’s brain and cognition including sense of control (Farah et al., 2006; Cohen et al., 2010; Hair et al., 2015). According to a survey by Mittal and Griskevicius (2014), poor children feel significantly less sense of control than wealthy children, though their study was conducted with children rather than adults.

Therefore, the hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1b. Childhood socioeconomic status positively affects adult sense of control.

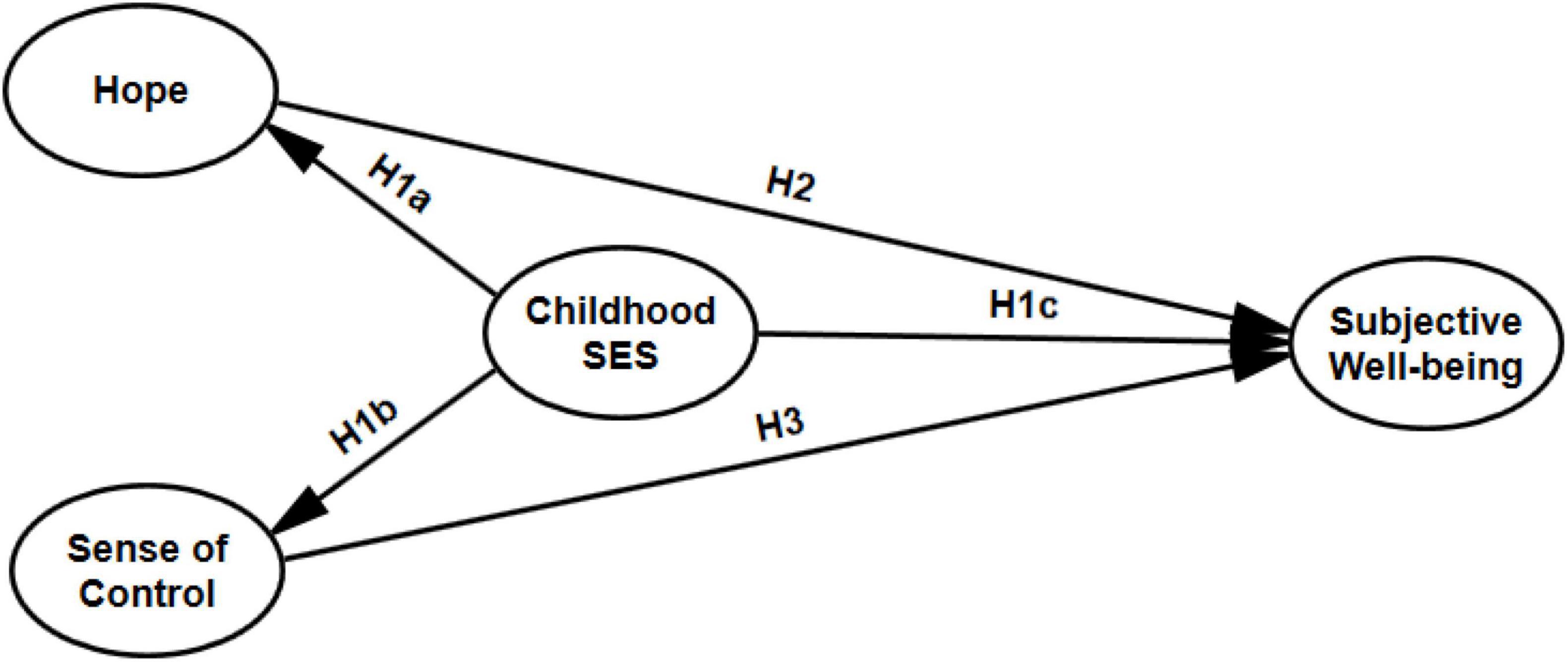

In sum, the hypothesis is as follows: Childhood socioeconomic status is directly and indirectly through hope and sense of control related to adult subjective wellbeing. Based on the proposed hypothesis, we designed the model with mediators, which is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The proposed structural relationships between childhood socioeconomic status, hope, sense of control and subjective wellbeing.

The purpose of this study is to expand on previous research by examining the relationship and influencing mechanisms between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing. This study focuses on the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status, hope, sense of control, and subjective wellbeing. Particularly, we aim to reveal whether (and to what extent) hope and sense of control mediate the link between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing.

568 rural residents (297 male, 271 female) participated in the survey. The mean age of participants was 48 (SD = 11.783), and the range was from 18 to 65. The participants’ education level was distributed as follows: 43.49% of the respondents had a primary education level (n = 247); 34.15% of the respondents had a junior high school education level (n = 194); 17.25% of the respondents had a high school education level (n = 98); and 5.11% of the respondents had a university education level (n = 29).

The research group, “Research on the Mental Health Promotion Strategy of Rural Residents under the Background of Targeted Poverty Alleviation” conducted a two-week questionnaire survey in Jianshi County, Hubei Province in July 2019. Jianshi County is a nationally recognized poverty-stricken county in China, consisting of 10 towns. To reduce the sample selection bias, the scope of this survey involves 8 towns and 19 villages in total, covering most of the area. Five villages in Huaping Town, the largest town in the county, were investigated, while 2 villages in each of all seven towns (Changliang Town, Gaoping Town, Hongyan Town, Guandian Town, Jingyang Town, Sanli Town, Maotian Town) were surveyed. 10–20 poor families and 10–20 non-poor families in each village were randomly selected to participate in the investigation. In addition, only one person (the head of household or his/her spouse) in each family was surveyed by two trained investigators through an interview-style questionnaire, where was conducted in the household’s home or in a common area of the workplace. Respondents who are literate and without functional limitation filled out the questionnaires themselves, and those who are illiterate or with functional limitation are asked to answer the questions through face-to-face interviews. A total of 600 questionnaires were handed out and 580 questionnaires were returned in the study. Questionnaire collection rate was 96.67%. Questionnaires with incorrect answers or incomplete information were removed. 568 valid questionnaires (270 poor samples, and 298 non-poor samples) were obtained among the 580 questionnaires and questionnaire-reclaiming efficiency was 94.67%. Adults with childhood poverty experiences are not certainly poor currently. Similarly, adults without childhood poverty experiences are not certainly out of poorness. Finally, 568 valid samples were conducted in the study.

All variables were measured by means of self-assessment. All the measurement instruments in this study directly used the translated Chinese version of the scales, which have been widely used in local Chinese studies.

Childhood socioeconomic status was assessed using the Chinese version of childhood socioeconomic status scale revised by Chinese scholar Yan et al. (2017), which was originally developed by Griskevicius et al. (2011a). Some studies have shown that Cronbach’s alpha is 0.805 (Yan et al., 2017) and 0.880 (Keye and Liuna, 2021) for the revised Chinese version of four-item scale, indicating high reliability and good measurement results. Childhood socioeconomic status was measured by participant recall during adulthood in this study. The measurement method was confirmed by many studies (Galobardes, 2004; Pollitt et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2010; Griskevicius et al., 2011b, 2013; Belsky et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2017; Keye and Liuna, 2021), which provided strong support for this study. To assess childhood socioeconomic status, participants were made to respond to the following three statements with a nine-point scale from 1, “strongly disagree, “to 9, “strongly agree”:

1) “My family usually had enough money for things when I was growing up.”

2) “I grew up in a relatively wealthy neighborhood.”

3) “I felt relatively wealthy compared to the other kids in my school.”

4) “My parents had higher socioeconomic status during my childhood.”

A higher score means the respondent had a better life during childhood. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale is 0.774. The mean value of childhood socioeconomic status was 2.861 (SD = 1.98), which was somewhat below the mid-score of the scale.

We measured hope using the Chinese version of State Hope Scale, which was originally developed by Snyder et al. (1996). Cronbach’s alpha is 0.830 (Zhihua, 2013) and 0.820 (Mengchao and Xiting, 2013) for the scale among Chinese adults, confirming good results for measuring hope among Chinese adults. The six items for the scale included the following:

1) “If I should find myself in a jam, I could think of many ways to get out of it.”

2) “There are lots of ways around any problem that I am facing now.”

3) “I can think of many ways to reach my current goals.”

4) “At present, I am energetically pursuing my goals.”

5) “Right now I see myself as being pretty successful.”

6) “At this time, I am meeting the goals that I have set for myself.”

An eight-point scale was used to evaluate the overall hope of the respondents. Respondents were made to answer each item according to the following choices: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (mostly disagree), 3 (somewhat disagree), 4 (slightly disagree), 5 (slightly agree), 6 (somewhat agree), 7 (mostly agree), and 8 (strongly agree). A higher score represents stronger hope. Internal consistency for all the items yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.805 for the scale. The mean value of hope was 4.966 (SD = 1.656), which was slightly above the mid-score of the scale.

Sense of control was measured using Chinese version of sense of control scale translated by Jiahe (2007), which was originally developed by McConatha and Huba (1999). Cronbach’s alpha is 0.823 among college students with higher education (Xiaoyu, 2017) while Cronbach’s alpha is 0.6 among respondents with lower education (Jiahe, 2007), showing that the scale was suitable for measuring the sense of control among Chinese rural adults. The scale can assess the overall sense of control more comprehensively. It only includes three items and it is relatively simple and easy to understand for Chinese rural residents with lower education. The three items for the scale are as follows:

1) “I often feel that most situations are out of my control.”

2) “Usually, I feel that I have control over what is going on in my life.”

3) “Life is complicated, a person like me can’t understand what is going on.”

Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score indicates a stronger sense of control. Internal consistency for all the items yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.468 for the scale and the internal consistency seems to be approximately acceptable. The mean value of the sense of control was 3.054 (SD = 0.765), which was slightly above the mid-score of the scale.

Adult subjective wellbeing was assessed using the Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale developed by Cantril (1965), which is a schematic diagram of a ladder with eleven steps. The Cantril-ladder was used in many studies (Ferrer-i-Carbonell, 2005; Kahneman and Deaton, 2010; Glatzer and Gulyas, 2014; Kristoffersen, 2018) and is still used in the Gallup World Poll (Harter and Gurley, 2008). It is a measure of the cognitive aspect of subjective wellbeing which represents an overall assessment of life. The ladder scale can assess subjective wellbeing more comprehensively and it is a non-verbal scale that applied to different cultures and regions well, especially, it is suitable for surveying rural residents with low education. The graphical measurement instrument makes the scale avoid depending on a specific language environment, especially in rural China where there are many dialects. Participants were made to select the current position ranging from 0 (worst possible life) to 10 (best possible life) according to their own criteria. The higher score, the higher subjective wellbeing. The mean value of subjective wellbeing was 5.511 (SD = 2.174), which was slightly above the mid-score of the scale.

Demographic variables such as gender, age, education and average household income were also controlled in the model. Males generally have lower subjective wellbeing than females (Knight et al., 2009). According to Easterlin (1995), high-income groups have a higher level of subjective wellbeing compared to low-income groups.

Statistical analysis of data in the study was carried out through STATA14.0 and AMOS24.0. Firstly, we examined common method biases, the reliability and validity of measurement scales. And descriptive statistics and correlations of variables were confirmed. Secondly, we tested the theoretical model in Figure 1 using structural equation modeling (SEM) and evaluated goodness of fit of model. Thirdly, we conducted the mediation testing of hope and sense of control using the bootstrapping method in the case of the 1000 samples taken via AMOS24.0. In addition, we compared the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing between the direct model (model 1: without mediator) and the mediation model (model 2: with mediator).

Harman’s single-factor test was used to examine the problem of common method biases. The results showed that there are 4 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. And the first factor explained 29.44% of the total variance, which is less than the critical value of 40% (Podsakoff et al., 2003), indicating that there is no obvious common method biases problem in this study.

Before further investigation, we firstly tested the reliability and validity of the scales. We calculated the reliability index (Cronbach’s α, construct reliability, factor loading of each factor) and validity index [average variance extracted (AVE) and ]. Tables 1, 2 show reliability and validity test results, the descriptive statistics, and Pearson’s correlations. Internal consistency seems to be approximately acceptable although the reliability results suggests that future research should pay more attention to the revision of the sense of control scale. In addition, AVE of all variables are greater than 0.3. Moreover, are greater than correlation coefficients between all variables, indicating that the measured instruments has good convergence validity and discriminative validity according to Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Tabachnick et al. (2007).

To be ensure the degree of fitness between the data and the structural equation model, we conducted a goodness-of-fit test on the model through the AMOS24.0 software. Table 3 shows the goodness of fit test results of structural equation model. According to the criteria proposed by Lance et al. (2007) and Kim et al. (2009), the results showed that the model represented a good fit for the data, and thus can be used in the study [χ2/df = 1.383; RMSEA = 0.026; GFI = 0.976; AGFI = 0.951; IFI = 0.985; CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.971; 90 percent confidence interval for RMSEA = (0.015; 0.036)].

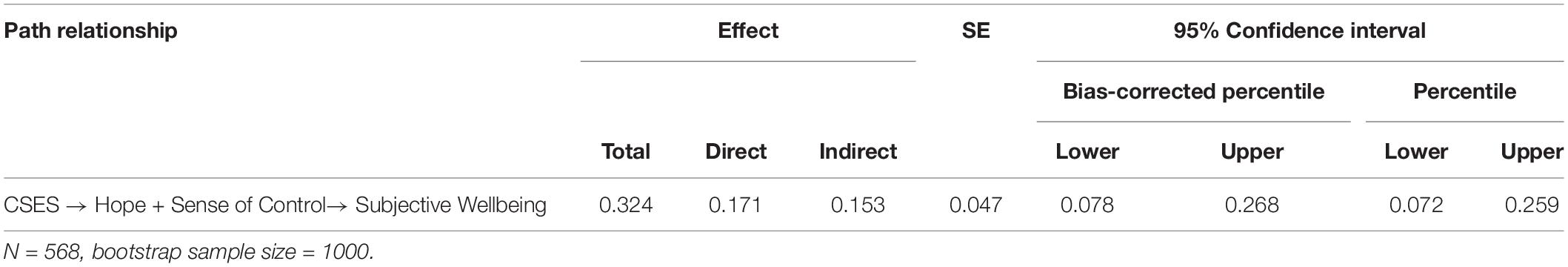

We conducted the mediation testing of hope and sense of control using the bootstrapping method in the case of the 1000 samples taken via AMOS24.0. Table 4 shows the results of the mediation testing using the bias-corrected percentile method and percentile method. It is found that the lower and upper bound values of the indirect effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing is 0.078 and 0.268, respectively by using the bias-corrected percentile method. The confidence interval (0.078, 0.268) does not include 0, suggesting that hope and sense of control play a mediating role in the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status and subjective wellbeing. Furthermore, as shown in Table 4, the indirect effects of mediated pathways between childhood SES and subjective wellbeing are 0.153.

Table 4. Testing results of the mediation effects using the Bias-corrected percentile method and percentile method.

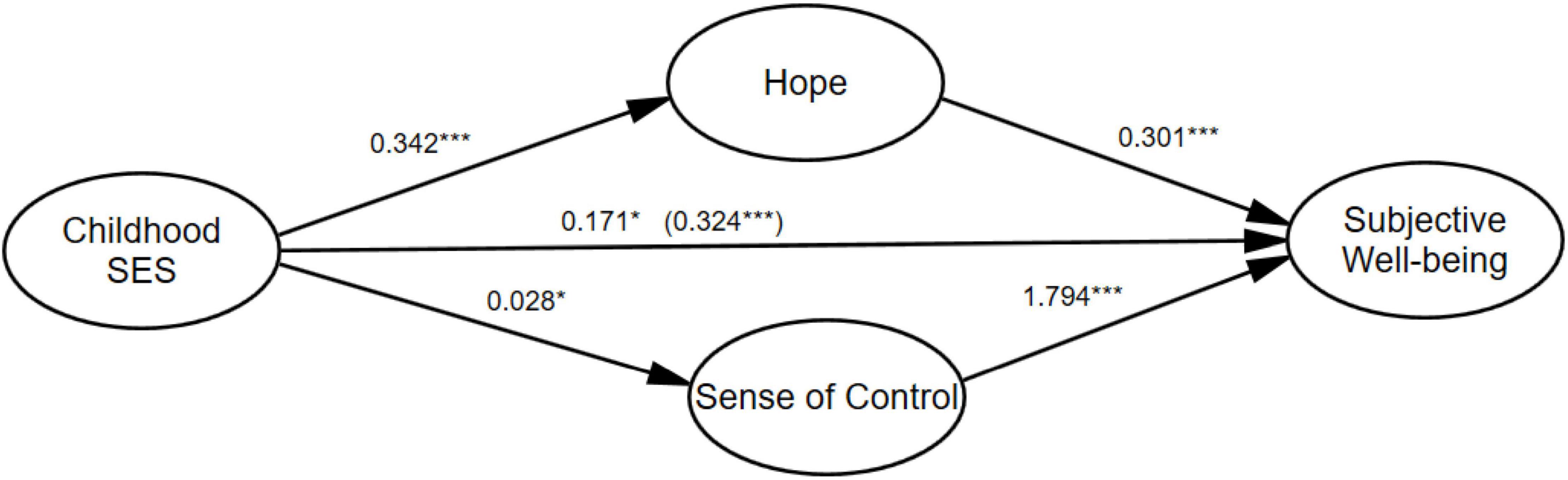

Table 5 illustrates the direct effects results of mediation model. As shown in Table 5, childhood socioeconomic status has significant positive impacts on hope (β = 0.342, p < 0.001) and hypothesis H1a was confirmed. Similarly, childhood socioeconomic status has significant positive impacts on sense of control (β = 0.028, p < 0.05) and hypothesis H1b was confirmed. Childhood socioeconomic status has significant positive impacts on subjective wellbeing (β = 0.171, p < 0.05) and hypothesis H1c was confirmed. Hope has significant positive impacts on subjective wellbeing (β = 0.301, p < 0.001), confirming hypothesis H2. Sense of control has significant positive impacts on subjective wellbeing (β = 1.794, p < 0.001), confirming hypothesis H3.

We compared the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing when there is hope and sense of control and when there is no hope and sense of control. Figure 2 shows the path coefficient results for the direct model (model 1: without mediators) and the mediation model (model 2: with mediators) between childhood socioeconomic status and subjective wellbeing. As shown in the results, the direct effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing in the model without mediators are 0.324 (p < 0.001). However, the direct effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing in the model with mediators are 0.171 (p < 0.05). Interestingly, the direct effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing are significantly smaller when the mediators are taken into the model. The results demonstrated hope and sense of control mediated the links between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing. What is more important, it revealed that hope and sense of control may buffer the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing.

Figure 2. Unstandardized estimated path coefficients of the structural equation model. N = 568. Model 1: Childhood SES → Subjective Wellbeing (without mediator). Model 2: Childhood SES → Hope + Sense of Control → Subjective Wellbeing. The numbers represent the beta coefficients for Model 2. The beta coefficients for Model 1 are in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.01.

Our study findings supported Hypothesis 1a, Hypothesis 1b, Hypothesis 1c, Hypothesis 2, and Hypothesis 3. Mediation analysis results indicated that childhood socioeconomic status was directly and indirectly through hope and sense of control related to adult subjective wellbeing.

One of our findings was that childhood socioeconomic status had direct and positive impacts on adult subjective wellbeing, implying that the negative impacts of poverty on children may extend throughout adulthood. This result was supported by previous studies (Duncan and Magnuson, 2013; McCarty, 2016). Adults who grew up in poor families tend to have lower educational attainment, face higher poverty risks, and assess themselves as being less happy (Oshio et al., 2009). The finding in this study was consistent with Oshio et al. (2009), demonstrating that the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing is more or less direct. Research by Cohen et al. (2010) also confirmed that adults with higher childhood socioeconomic status were more likely to have positive social emotions.

A possible explanation is that lower childhood socioeconomic status was often accompanied by adverse childhood experiences including domestic violence (Gelles, 1992; Brandwein, 2007), discrimination (Branscombe and Ellemers, 1998; Lang, 2011; Fuller-Rowell et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2018), single-parent households (Jonson-Reid et al., 2013), lower parental education and poor parenting (Hughes et al., 2005; Laplaca and Corlyon, 2015; September et al., 2015), poorer educational resources and facilities (Evans and Kantrowitz, 2002), poorer housing quality and smaller house (Gİtmez and Morcöl, 1994; Evans, 2006). These social stressors are bound to cause many negative effects on children’s mental health. Moreover, the negative impacts of low socioeconomic status on children may accumulate over time or lie dormant for years. The long-term negative impacts were revealed during adulthood and persist throughout life (McLeod and Shanahan, 1996; Brooks-Gunn and Duncan, 1997; Foster and Furstenberg, 1999; Ratcliffe and McKernan, 2010; McCarty, 2016). For example, adults with adverse childhood experiences including parents quarreling and beating each other during childhood are more likely to fall into depression (Mwachofi et al., 2020). Besides, to a large extent, adult emotional responses, behaviors, and decisions are determined by childhood socioeconomic status (Griskevicius et al., 2013). Adults who grew up in the context of higher childhood socioeconomic status were more rational and more likely to make right decisions. Consequences of right decisions and behaviors are conducive to subjective wellbeing (Mittal and Griskevicius, 2014).

Another important result in our study indicated that hope and sense of control mediated the links between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing. As shown in the results, the direct effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing in the model without mediators are 0.324. However, the direct effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing in the model with mediators are 0.171. The direct effects of childhood socioeconomic status on subjective wellbeing are significantly smaller when the mediators are taken into the model, revealing that hope and sense of control may buffer the negative impacts of childhood poverty experiences on subjective wellbeing. Our research not only explained how childhood socioeconomic status affected adult subjective wellbeing from a cognitive perspective, but also confirmed the points by Cohen et al. (2010) and Chitchai et al. (2020) that childhood socioeconomic status was mainly linked to adult subjective wellbeing through internal psychological mechanisms. Our results are consistent with Satici et al. (2020), demonstrating that hope is positively related to subjective wellbeing. The main reason may be that adults with higher expectations were good at balancing multiple social roles (work, marriage, family) and having more intimate and harmonious relationships with colleagues, partners, and children, resulting in higher happiness (Kashdan et al., 2002). Our study also confirms that childhood socioeconomic status is positively related to sense of control. As explained by Zhou et al. (2009), adults who grew up in higher social classes had higher sense of security, more self-confidence, stronger problem-solving skills, causing higher sense of control.

The most important contribution of this research is that our study confirms the buffering effects of mediating variables (hope and sense of control) on the negative impacts of lower childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing. The paper highlights the importance of hope and sense of control in the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status and subjective wellbeing. Even if adults grew up in poverty during childhood, we can reduce the cost of childhood poverty on adult subjective wellbeing by intervening in hope and sense of control. In fact, we can also see that a large number of adults suffered from childhood poverty in real life still have higher subjective wellbeing. The study also implies that future research should focus on exploring the various mediating variables between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing, and considering how to intervene these mediator variables to reduce the negative impacts of childhood poverty experiences on adult subjective wellbeing.

Another important contribution of this study is that our study explores the internal mechanism of how childhood socioeconomic status affects adult subjective wellbeing from the perspective of psychology. Most studies considered how to improve people’s wellbeing through outcomes including education and income while ignoring the role of the individual’s intrinsic cognitive function. Our findings suggests that hope and sense of control are key factors to consider when exploring the impacts of childhood poverty on adult subjective wellbeing. This paper provides new insights into the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status on adult subjective wellbeing and expand the literature on key elements of adult subjective wellbeing. In particular, based on micro-survey data from poor rural areas in China, this study provides evidences that childhood socioeconomic status affects adult subjective wellbeing in non-western cultural contexts.

In addition, this study has some practical implications. This study guides us to pay more attention to children with lower socioeconomic status, in particular, to emphasize the impacts of socioeconomic status on their hope and sense of control. As pointed out by McCarty (2016), hope of resilience through policies and programs were offered to reduce child poverty and mitigate its damages (McCarty, 2016). Moreover, Adult hope was closely related to childhood hope (Kraftl, 2008; Bruner, 2017). Especially for families with lower socioeconomic status, it was crucial to build hope for them in early childhood (Glewwe et al., 2017). Therefore, in addition to implementing financial assistance to ensure children and adolescents’ basic living security, it also emphasizes that their hope and sense of control can be fostered through early family intervention, school education, and third-party social support in the process of practical intervention. For example, encourage self-presentation and provide more opportunities for self-expression, learning and communication with the outside world.

Future research should focus on improving three aspects: Firstly, it will be more accurately to reflect the impacts of childhood socioeconomic status via conducting a longitudinal study, as well as the effects of childhood socioeconomic status on individuals’ subjective wellbeing at different time throughout the lifespan. Secondly, further studies are necessary to focus on exploring more mediating variables between childhood socioeconomic status and adult subjective wellbeing, and considering how to intervene these mediators to reduce the negative impacts of childhood poverty experiences on adult subjective wellbeing. Thirdly, future research in this field should focus on the role of family education on the relationship between childhood socioeconomic status and hope and sense of control.

Firstly, this study focuses on the subjective wellbeing of residents in rural, poverty-stricken areas in China, excluding rural residents in non-poor areas. Future research can expand the range of investigation for comparative analysis. Secondly, adults were asked to recall their SES during childhood in our study and these recollections may be biased. This suggests that future studies can improve this study by test the study’s hypothesis using longitudinal data that assess pathways connecting childhood SES, mediators, adult wellbeing across multiple time points in the life span. Thirdly, the Cronbach’s alpha value of sense of control scale in this study is a bit low, suggesting that further research should pay attention to the development and revision of the sense of control scale for rural residents. Lastly, the direction between variables can be other than we assumed and we did not verify that. For example, childhood socioeconomic status can be indirectly related to hope and sense of control via adult subjective wellbeing.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

FL designed the work and the field survey. LW, KM, and FL collected the data. LW analyzed the data and experiment’s results and wrote the manuscript. KD modified grammar and expressions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (17BSH094) and China Scholarship Council.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879132/full#supplementary-material

Allender, D. (2014). The Wounded Heart: Hope for Adult Victims of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Colorado Springs, CO: The Navigators.

Astin, J., and Shapiro, D. H. (1997). Measuring the psychological construct of control: applications to transpersonal psychology. J. Transpers. Psychol. 29, 63–72.

Belsky, J., Schlomer, G. L., and Ellis, B. J. (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Dev. Psychol. 48, 662–673. doi: 10.1037/a0024454

Brandwein, R. A. (2007). “The not-so-tender trap: Family violence and child poverty,” in Child Poverty in America Today, eds B. A. Arrighi and D. J. Maume (Westport, CO: Praeger), 17–211.

Branscombe, N. R., and Ellemers, N. (1998). “Coping with group-based discrimination: individualistic versus group-level strategies,” in Prejudice, eds J. K. Swim and C. Stangor (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 243–266. doi: 10.1016/B978-012679130-3/50046-6

Brooks-Gunn, J., and Duncan, G. J. (1997). Income Effects Across the Life Span: Integration and Interpretation. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 596–610.

Bruner, C. (2017). ACE, place, race, and poverty: building hope for children. Acad. Pediatr. 17, S123–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.009

Burger, J. M. (1989). Negative reactions to increases in perceived personal control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 246–256. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.246

Caria, S. A., and Falco, P. (2018). Does the risk of poverty reduce happiness? Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 67, 1–28. doi: 10.1086/697556

Chitchai, N., Senasu, K., and Sakworawich, A. (2020). The moderating effect of love of money on relationship between socioeconomic status and happiness. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 41, 336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.kjss.2018.08.002

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., and Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: an explanation for the easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J. Econ. Liter. 46, 95–144. doi: 10.1257/jel.46.1.95

Claussen, B. (2003). Impact of childhood and adulthood socioeconomic position on cause specific mortality: the Oslo Mortality Study. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 57, 40–45. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.40

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., Chen, E., and Matthews, K. A. (2010). Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1186, 37–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05334.x

Cotton Bronk, K., Hill, P. L., Lapsley, D. K., Talib, T. L., and Finch, H. (2009). Purpose, hope, and life satisfaction in three age groups. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 500–510. doi: 10.1080/17439760903271439

Cuñado, J., and de Gracia, F. P. (2011). Does education affect happiness? Evidence for spain. Soc. Indic. Res. 108, 185–196. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9874-x

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., and Biswas-Diener, R. (2002). Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc. Indic. Res. 57, 119–169. doi: 10.1023/A:1014411319119

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., and Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: a meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 879–924. doi: 10.1037/a0037409

Dix, T., and Moed, A. (2019). “Parenting and depression,” in Handbook of Parenting vol. 4: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, 3rd Edn, ed. M. H. Bornstein (New York, NY: Routledge), 449–482.

Donaldson, S. I., Dollwet, M., and Rao, M. A. (2014). Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 10, 185–195. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2014.943801

Duncan, G. J., and Magnuson, K. (2013). “The long reach of early childhood poverty,” in Economic Stress, Human Capital, and Families in Asia, eds W. J. Yeung and M. Yap (Dordrecht: Springer), 57–70. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7386-8-4

Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., Kalil, A., and Ziol-Guest, K. (2011). The importance of early childhood poverty. Soc. Indic. Res. 108, 87–98. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9867-9

Duncan, G. J., Ziol-Guest, K. M., and Kalil, A. (2010). Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Dev. 81, 306–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01396.x

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 27, 35–47. doi: 10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-b

Evans, G. W. (2006). Child development and the physical environment. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57, 423–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904

Evans, G. W. (2016). Childhood poverty and adult psychological well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14949–14952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604756114

Evans, G. W., and Kantrowitz, E. (2002). Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu. Rev. Public Health 23, 303–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.112001.112349

Farah, M. J., Shera, D. M., Savage, J. H., Betancourt, L., Giannetta, J. M., Brodsky, N. L., et al. (2006). Childhood poverty: specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain Res. 1110, 166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.072

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J. Public Econ. 89, 997–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.003

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18:382. doi: 10.2307/3150980

Foster, E. M., and Furstenberg, F. F. Jr. (1999). The most disadvantaged children: trends over time. Soc. Serv. Rev. 73, 560–578. doi: 10.1086/514445

Frederick, J., and Goddard, C. (2007). Exploring the relationship between poverty, childhood adversity and child abuse from the perspective of adulthood. Child Abuse Rev. 16, 323–341. doi: 10.1002/car.971

Fuller-Rowell, T. E., Evans, G. W., and Ong, A. D. (2012). Poverty and health: the mediating role of perceived discrimination. Psychol. Sci. 23, 734–739. doi: 10.1177/0956797612439720

Galobardes, B. (2004). Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality in adulthood: systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiol. Rev. 26, 7–21. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh008

Gelles, R. J. (1992). Poverty and violence toward children. Am. Behav. Sci. 35, 258–274. doi: 10.1177/0002764292035003005

Gİtmez, A. S., and Morcöl, G. (1994). Socio-economic status and life satisfaction in Turkey. Soc. Indic. Res. 31, 77–98. doi: 10.1007/bf01086515

Glatzer, W., and Gulyas, J. (2014). “Cantril self-anchoring striving scale,” in Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, ed. A. C. Michalos (Dordrecht: Springer), 509–511. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_259

Glewwe, P., Ross, P. H., and Wydick, B. (2017). Developing hope among impoverished children. J. Hum. Resour. 53, 330–355. doi: 10.3368/jhr.53.2.0816-8112r1

Goodman, S. H. (2007). Depression in mothers. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 3, 107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091401

Greene, D. C., and Britton, P. J. (2015). Predicting adult LGBTQ happiness: impact of childhood affirmation, self-compassion, and personal mastery. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 9, 158–179. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2015.1068143

Griskevicius, V., Ackerman, J. M., Cantú, S. M., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., Simpson, J. A., et al. (2013). When the economy falters, do people spend or save? Responses to resource scarcity depend on childhood environments. Psychol. Sci. 24, 197–205. doi: 10.1177/0956797612451471

Griskevicius, V., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., and Tybur, J. M. (2011a). Environmental contingency in life history strategies: the influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on reproductive timing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100, 241–254. doi: 10.1037/a0021082

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Delton, A. W., and Robertson, T. E. (2011b). The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: a life history theory approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100, 1015–1026. doi: 10.1037/a0022403

Hair, N. L., Hanson, J. L., Wolfe, B. L., and Pollak, S. D. (2015). Association of child poverty, brain development, and academic achievement. JAMA Pediatr. 169:822. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1475

Harter, J. K., and Gurley, V. F. (2008). Measuring well-being in the United States. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 21, 23–26.

Havel, V. (1990). Disturbing the Peace: A Conversation With Karel Hvizdala (Trans. Paul Wilson). New York, NY: Vintage.

He, B., Fan, J., Liu, N., Li, H., Wang, Y., Williams, J., et al. (2012). Depression risk of “left-behind children” in rural China. Psychiatry Res. 200, 306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.001

Howell, R. T., and Howell, C. J. (2008). The relation of economic status to subjective well-being in developing countries: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 134, 536–560. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.536

Hughes, M., and Tucker, W. (2018). Poverty as an adverse childhood experience. N. C. Med. J. 79, 124–126. doi: 10.18043/ncm.79.2.124

Hughes, S. O., Power, T. G., Orlet Fisher, J., Mueller, S., and Nicklas, T. A. (2005). Revisiting a neglected construct: parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 44, 83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.08.007

Jang, Y., Chiriboga, D. A., and Small, B. J. (2008). Perceived discrimination and psychological well-being: the mediating and moderating role of sense of control. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 66, 213–227. doi: 10.2190/ag.66.3.c

Jiahe, W. (2007). Research and Intervention on the Sense of Control and Control Strategies Among Male Prisoners. Shanghai: Shanghai Normal University.

Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B., and Zhou, P. (2013). Neglect subtypes, race, and poverty: individual, family, and service characteristics. Child Maltreat. 18, 30–41. doi: 10.1177/1077559512462452

Jv, L., Xi, T., Bing, X., Yanpei, D., Changcai, Z., Changsheng, L., et al. (2015). Prevalence study on injuries among the left-behind children in rural area of Jianshi county. Chin. J. Child Health Care 23, 123–125. doi: 10.11852/zgetbjzz2015-23-02-04

Kahneman, D., and Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16489–16493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Kaiser, T., Li, J., Pollmann-Schult, M., and Song, A. (2017). Poverty and child behavioral problems: the mediating role of parenting and parental well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:981. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14090981

Kashdan, T. B., Pelham, W. E., Lang, A. R., Hoza, B., Jacob, R. G., Jennings, J. R., et al. (2002). Hope and optimism as human strengths in parents of children with externalizing disorders: stress is in the eye of the beholder. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 21, 441–468. doi: 10.1521/jscp.21.4.441.22597

Keye, Z., and Liuna, G. (2021). The effect of childhood socioeconomic status on People’s life history strategy: the role of foresight for the future and sense of control. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 29, 838–841. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.04.035

Kiecolt, K. J., Hughes, M., and Keith, V. M. (2009). Can a high sense of control and John Henryism be bad for mental health? Sociol. Q. 50, 693–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01152.x

Kim, T. Y., Hon, A. H., and Crant, J. M. (2009). Proactive personality, employee creativity, and newcomer outcomes: a longitudinal study. J. Bus. Psychol. 24, 93–103. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9094-4

Klama, E. K., and Egan, V. (2011). The Big-Five, sense of control, mental health and fear of crime as contributory factors to attitudes towards punishment. Pers. Individ. Differ. 51, 613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.028

Knight, J., Song, L., and Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 20, 635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2008.09.003

Kraftl, P. (2008). Young people, hope, and childhood-hope. Space Cult. 11, 81–92. doi: 10.1177/1206331208315930

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., and Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: how the rich are different from the poor. Psychol. Rev. 119, 546–572. doi: 10.1037/a0028756

Kristoffersen, I. (2018). Great expectations: education and subjective wellbeing. J. Econ. Psychol. 66, 64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2018.04.005

Lachman, M. E., and Weaver, S. L. (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 763–773. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763

Laplaca, V., and Corlyon, J. (2015). Unpacking the relationship between parenting and poverty: theory, evidence and policy. Soc. Policy Soc. 15, 11–28. doi: 10.1017/s1474746415000111

Lee, C. M., Mangurian, C., Tieu, L., Ponath, C., Guzman, D., and Kushel, M. (2017). Childhood adversities associated with poor adult mental health outcomes in older homeless adults: results from the HOPE HOME study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 25, 107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.07.019

Lee, J. K., Biglan, A., and Cody, C. (2018). “The impact of poverty and discrimination on family interactions and problem development,” in Handbook of Parenting and Child Development Across the Lifespan, eds M. Sanders and A. Morawska (Cham: Springer), 699–712. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-94598-9_31

Lyubomirsky, S., and Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. indic. Res. 46, 137–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006824100041

Magnuson, K. A., and Duncan, G. J. (2002). “Parents in poverty,” in Handbook of Parenting: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, ed. M. H. Bornstein (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 95–121.

McCarty, A. T. (2016). Child Poverty in the United States: a tale of devastation and the promise of hope. Sociol. Compass 10, 623–639. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12386

McConatha, J. T., and Huba, H. M. (1999). Primary, secondary, and emotional control across adulthood. Curr. Psychol. 18, 164–170. doi: 10.1007/s12144-999-1025-z

McLeod, J. D., and Shanahan, M. J. (1996). Trajectories of poverty and Children’s mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 37:207. doi: 10.2307/2137292

Mengchao, L., and Xiting, H. (2013). Critical review of psychological studies on hope. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 21, 548–560.

Middlemiss, W. (2003). Poverty, stress, and support: patterns of parenting behaviour among lower income black and lower income white mothers. Infant Child Dev. 12, 293–300. doi: 10.1002/icd.307

Mittal, C., and Griskevicius, V. (2014). Sense of control under uncertainty depends on people’s childhood environment: a life history theory approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 621–637. doi: 10.1037/a0037398

Moradi, B., and Hasan, N. T. (2004). Arab american persons’ reported experiences of discrimination and mental health: the mediating role of personal control. J. Couns. Psychol. 51, 418–428. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.4.418

Munoz, R. T., Hanks, H., and Hellman, C. M. (2020). Hope and resilience as distinct contributors to psychological flourishing among childhood trauma survivors. Traumatology 26, 177–184. doi: 10.1037/trm0000224

Mwachofi, A., Imai, S., and Bell, R. A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in adulthood: evidence from North Carolina. J. Affect. Disord. 267, 251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.021

Oshio, T., Sano, S., and Kobayashi, M. (2009). Child poverty as a determinant of life outcomes: evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Soc. Indic. Res. 99, 81–99. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9567-x

Oshio, T., Umeda, M., and Kawakami, N. (2013). Childhood adversity and adulthood subjective well-being: evidence from Japan. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 843–860. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9358-y

Padilla, C. M., and Ryan, R. M. (2019). The link between child temperament and low-income mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Infant Ment. Health J. 40, 217–233. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21770

Parks, P. L., and Smeriglio, V. L. (1986). Relationships among parenting knowledge, quality of stimulation in the home and infant development. Fam. Relat. 35:411. doi: 10.2307/584369

Pautler, K. J., and Lewko, J. H. (1987). Children’s and adolescents’ views of the work world in times of economic uncertainty. New Direct. Child Adolesc. Dev. 35, 21–31. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219873504

Piff, P. K., and Moskowitz, J. P. (2018). Wealth, poverty, and happiness: social class is differentially associated with positive emotions. Emotion 18, 902–905. doi: 10.1037/emo0000387

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Pollitt, R. A., Rose, K. M., and Kaufman, J. S. (2005). Evaluating the evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 5:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-7

Ratcliffe, C., and McKernan, S. M. (2010). Childhood Poverty Persistence: Facts and Consequences. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 1–1.

Rodin, J. (1986). Aging and health: effects of the sense of control. Science 233, 1271–1276. doi: 10.1126/science.3749877

Ruggiero, K. M., and Taylor, D. M. (1995). Coping with discrimination: how disadvantaged group members perceive the discrimination that confronts them. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 826–838. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.826

Satici, S. A., Kayis, A. R., Satici, B., Griffiths, M. D., and Can, G. (2020). Resilience, hope, and subjective happiness among the turkish population: fear of COVID-19 as a mediator. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00443-5

Seccombe, K. (2000). Families in poverty in the 1990s: trends, causes, consequences, and lessons learned. J. Marriage Fam. 62, 1094–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01094.x

September, S. J., Rich, E. G., and Roman, N. V. (2015). The role of parenting styles and socio-economic status in parents’ knowledge of child development. Early Child Dev. Care 186, 1060–1078. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2015.1076399

Shorey, H. S., Snyder, C. R., Yang, X., and Lewin, M. R. (2003). The role of hope as a mediator in recollected parenting, adult attachment, and mental health. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 22, 685–715. doi: 10.1521/jscp.22.6.685.22938

Shumow, L., Vandell, D. L., and Posner, J. K. (1998). Harsh, firm, and permissive parenting in low-income families. J. Fam. Issues 19, 483–507. doi: 10.1177/019251398019005001

Slack, K. S., Holl, J. L., McDaniel, M., Yoo, J., and Bolger, K. (2004). Understanding the risks of child neglect: an exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreat. 9, 395–408. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269193

Snyder, C. R. (1995). Conceptualizing, measuring, and nurturing hope. J. Couns. Dev. 73, 355–360. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01764.x

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychol. inq. 13, 249–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., et al. (1991). The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 570–585. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., and Sigmon, D. R. (2002). “Hope theory: a member of the positive psychology family,” in Handbook of Positive Psychology, eds C. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 257–276.

Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., and Sigmon, D. R. (2005). “Hope theory: a member of the positive psychology family,” in Handbook of Positive Psychology, eds C.R. Snyder and S.J. Lopez (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 257–278.

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., and Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 321–335. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.321

Steele, H., Bate, J., Steele, M., Dube, S. R., Danskin, K., Knafo, H., et al. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences, poverty, and parenting stress. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 48, 32–38. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000034

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., and Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics, Vol. 5. Boston, MA: Pearson, 481–498.

Tan, H., Luo, J., and Zhang, M. (2020). Higher education, happiness, and Residents’, health. Front. Psychol. 11:1669. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01669

Veenhoven, R. (2012). Cross-national differences in happiness: cultural measurement bias or effect of culture? Int. J. Wellbeing 2, 333–353. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.4

Wang, L., Zheng, Y., Li, G., Li, Y., Fang, Z., Abbey, C., et al. (2019). Academic achievement and mental health of left-behind children in rural China: a causal study on parental migration. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 11, 569–582. doi: 10.1108/CAER-09-2018-0194

Wen, M., and Lin, D. (2011). Child development in rural china: children left behind by their migrant parents and children of non-migrant families. Child Dev. 83, 120–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01698.x

Winter, L., Morawska, A., and Sanders, M. R. (2011). The effect of behavioral family intervention on knowledge of effective parenting strategies. J. Child Fam. Stud. 21, 881–890. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9548-y

Wolinsky, F. D., Wyrwich, K. W., Kroenke, K., Babu, A. N., and Tierney, W. M. (2003). 9-11, personal stress, mental health, and sense of control among older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 58, S146–S150. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s146

Xiaoyu, D. (2017). Research on the Relationship of Family Socioeconomic Status and Career Adaptability of Rural College Students: The Moderating Effect of the Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Perceived Control. Kunming: Yunnan Normal University.

Yan, W., Zhenchao, L., Bowen, H., and Shijin, S. (2017). The intrinsic mechanism of life history trade-offs: the mediating role of control striving. Acta Psychol. Sin. 49, 783–793.

Zhihua, L. (2013). The Developmental Trajectories and Effect Factors of Hope and its Relations With Mental Health on College Students. Changsha: Central South University.

Keywords: childhood socioeconomic status, hope, sense of control, subjective wellbeing, mediation effects

Citation: Wang L, Li F, Meng K and Dunning KH (2022) Childhood Socioeconomic Status and Adult Subjective Wellbeing: The Role of Hope and Sense of Control. Front. Psychol. 13:879132. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879132

Received: 18 February 2022; Accepted: 10 June 2022;

Published: 04 July 2022.

Edited by:

Elise Renard, Université de Nantes, FranceReviewed by:

André Luiz Monezi Andrade, Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas, BrazilCopyright © 2022 Wang, Li, Meng and Dunning. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fenglan Li, TGlmZW5nbGFuMTE2NkBtYWlsLmh6YXUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.